Lecture_5_-_25_02.ppt

- Количество слайдов: 22

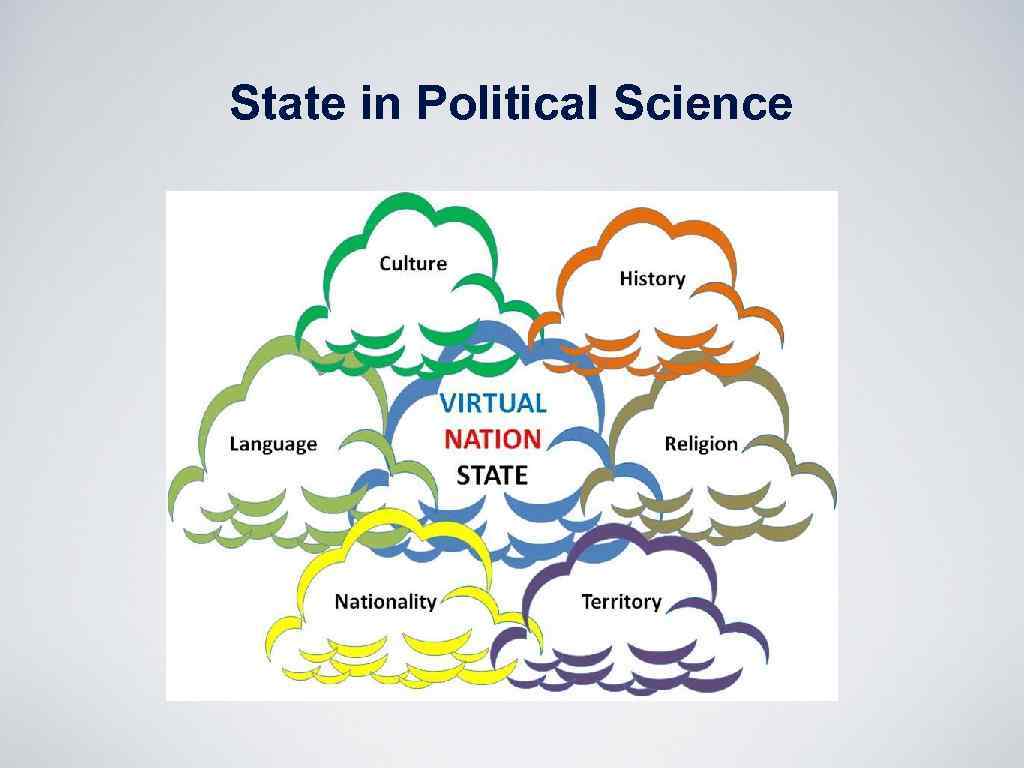

State in Political Science

State in Political Science

Contents 1. Concept of State 2. Theories of State

Contents 1. Concept of State 2. Theories of State

The concept of State in Political Science is that science which studies and analyses the State. It studies static structure of the state and dynamics of relations. It has to do with the State at rest and with the State in action. If Public Law deals with the State as it is, i. e. its normal arrangements, the permanent conditions of its existence. Politics, on the other hand, has to do with the life and conduct of the State, pointing out the end toward which public efforts are directed and teaching the means which lead to these ends, observing the action of laws upon facts and considering how to avoid injurious consequences and how to remedy the defects of existing arrangements.

The concept of State in Political Science is that science which studies and analyses the State. It studies static structure of the state and dynamics of relations. It has to do with the State at rest and with the State in action. If Public Law deals with the State as it is, i. e. its normal arrangements, the permanent conditions of its existence. Politics, on the other hand, has to do with the life and conduct of the State, pointing out the end toward which public efforts are directed and teaching the means which lead to these ends, observing the action of laws upon facts and considering how to avoid injurious consequences and how to remedy the defects of existing arrangements.

Origins of State emerged on the verge of class relations and struggle, where open-end outcomes for such relations typically meant denial of the power of one class by another. To overcome class warfare and physical destruction in civil wars classes created the State. Class war was systemic. Such conditions would require systemic structure to overcome such crises. One of the most crucial point in history of the State war Reformation when State separated from Church and monarchs acquired unrestricted absolute power.

Origins of State emerged on the verge of class relations and struggle, where open-end outcomes for such relations typically meant denial of the power of one class by another. To overcome class warfare and physical destruction in civil wars classes created the State. Class war was systemic. Such conditions would require systemic structure to overcome such crises. One of the most crucial point in history of the State war Reformation when State separated from Church and monarchs acquired unrestricted absolute power.

Medieval monarchic state - a prerequisite state for the Modern state - Rule by kings, lords, bishops, priests and town oligarchies was a competition for rights of jurisdiction over the lower orders, and a member of those lower orders often did not know who his real ruler was. - Lords had rights in the labour of serfs and also rights of jurisdiction through manorial courts. - The Church decided whom they might marry and how and to whom they could leave their property. - The Church had rights of taxation and so did the lord if the labour services of serfs were commuted to a money payment. - Different courts could try them for different offences, lay and ecclesiastical,

Medieval monarchic state - a prerequisite state for the Modern state - Rule by kings, lords, bishops, priests and town oligarchies was a competition for rights of jurisdiction over the lower orders, and a member of those lower orders often did not know who his real ruler was. - Lords had rights in the labour of serfs and also rights of jurisdiction through manorial courts. - The Church decided whom they might marry and how and to whom they could leave their property. - The Church had rights of taxation and so did the lord if the labour services of serfs were commuted to a money payment. - Different courts could try them for different offences, lay and ecclesiastical,

- There was no centralised state. - In feudal societies rights of jurisdiction (legal authority) were jealously defended. - The Church kept secular authority out of its own lands if it could; towns governed by their own charters resisted kings, and kings did not hesitate to bring force upon their vassals. - The king was just a greater lord among great lords who owed him fealty, certain military services, and the duty to give advice if asked. - The only time the realm was a single unit was in time of war. The king might call upon everybody’s services in times of national emergency like foreign invasion. But even this duty was limited to a period of days, and armies often had to be paid to stay together when the period of agreed conscription was over.

- There was no centralised state. - In feudal societies rights of jurisdiction (legal authority) were jealously defended. - The Church kept secular authority out of its own lands if it could; towns governed by their own charters resisted kings, and kings did not hesitate to bring force upon their vassals. - The king was just a greater lord among great lords who owed him fealty, certain military services, and the duty to give advice if asked. - The only time the realm was a single unit was in time of war. The king might call upon everybody’s services in times of national emergency like foreign invasion. But even this duty was limited to a period of days, and armies often had to be paid to stay together when the period of agreed conscription was over.

Contradictions and irreconcilable nature of conflicts would require centralisation It was considered rational on common basis to concentrate all power in a sovereign ruler, when his authority and laws would guarantee peace. - The Wars of the Roses in England for thirty years just to make way for Tudor monarchs in 1485 to get the English throne. It was largely powerhungry aristocratic opportunism - The French wars of religion in XVI century mingled aristocratic ambition and religious enthusiasm. - The English civil war of 1642 -1651 between Parliamentarians (‘Roundheads’) and Royalists (‘Cavaliers’), after 46 years of which power was eventually restricted by Parliament. - Thirty Years War in Germany, also is a part of the long transition from medieval localism to the centralized modern state.

Contradictions and irreconcilable nature of conflicts would require centralisation It was considered rational on common basis to concentrate all power in a sovereign ruler, when his authority and laws would guarantee peace. - The Wars of the Roses in England for thirty years just to make way for Tudor monarchs in 1485 to get the English throne. It was largely powerhungry aristocratic opportunism - The French wars of religion in XVI century mingled aristocratic ambition and religious enthusiasm. - The English civil war of 1642 -1651 between Parliamentarians (‘Roundheads’) and Royalists (‘Cavaliers’), after 46 years of which power was eventually restricted by Parliament. - Thirty Years War in Germany, also is a part of the long transition from medieval localism to the centralized modern state.

Characteristics of the state First, the state is all-comprehensive. Its organisation embraces all persons, natural or legal, and all associations of persons. There are no stateless persons within the territory of the state. Second, the state is exclusive. Political science and public law do not recognise the existence of an imperium in imperio. Third, the state is permanent. It does not lie within the power of men to create it today and destroy it tomorrow, as caprice may move them. Anarchy is a permanent impossibility. Fourth and last, the state is sovereign. This is its most essential principle. An organisation may be conceived which would include every member of a given population, or every inhabitant of a given territory, and which might continue with great permanence, and yet it might not be the state. If, however, it possesses the sovereignty over the population, then it is the state.

Characteristics of the state First, the state is all-comprehensive. Its organisation embraces all persons, natural or legal, and all associations of persons. There are no stateless persons within the territory of the state. Second, the state is exclusive. Political science and public law do not recognise the existence of an imperium in imperio. Third, the state is permanent. It does not lie within the power of men to create it today and destroy it tomorrow, as caprice may move them. Anarchy is a permanent impossibility. Fourth and last, the state is sovereign. This is its most essential principle. An organisation may be conceived which would include every member of a given population, or every inhabitant of a given territory, and which might continue with great permanence, and yet it might not be the state. If, however, it possesses the sovereignty over the population, then it is the state.

Theories of the State Classical and medieval Theory Most European medieval and Renaissance political thinkers took a religious approach to the study of government and politics. Which was strictly normative, seeking to discover the “ought” or “should” and rarely descriptive about the “is, ” the real-world situation. - Informed by religious, legal, and philosophical values, - Sought to discover which system of government would bring humankind closest to the city of God, to the God’s will.

Theories of the State Classical and medieval Theory Most European medieval and Renaissance political thinkers took a religious approach to the study of government and politics. Which was strictly normative, seeking to discover the “ought” or “should” and rarely descriptive about the “is, ” the real-world situation. - Informed by religious, legal, and philosophical values, - Sought to discover which system of government would bring humankind closest to the city of God, to the God’s will.

Niccolò Machiavelli in the early sixteenth century introduced what some believe to be the central issue of modern political science: the focus on power. His great work The Prince was about the getting and using of political power. Many philosophers rate Machiavelli as the first modern philosopher because his motivations and explanations were distant from religion. Machiavelli was not as wicked as some people say. He was a realist who argued that to accomplish anything good—such as the unification of Italy and expulsion of the foreigners who ruined it—the Prince had to be rational and tough in the exercise of power.

Niccolò Machiavelli in the early sixteenth century introduced what some believe to be the central issue of modern political science: the focus on power. His great work The Prince was about the getting and using of political power. Many philosophers rate Machiavelli as the first modern philosopher because his motivations and explanations were distant from religion. Machiavelli was not as wicked as some people say. He was a realist who argued that to accomplish anything good—such as the unification of Italy and expulsion of the foreigners who ruined it—the Prince had to be rational and tough in the exercise of power.

Theory of Social Contract “Contractualists”—Hobbes, Locke, and Rousseau — analysed why political systems should exist at all - ‘raison d’etre’ of the State. They differed in many points but agreed that humans, at least in principle, had joined in what Rousseau called a ‘social contract’.

Theory of Social Contract “Contractualists”—Hobbes, Locke, and Rousseau — analysed why political systems should exist at all - ‘raison d’etre’ of the State. They differed in many points but agreed that humans, at least in principle, had joined in what Rousseau called a ‘social contract’.

Hobbes imagined that life in “the state of nature, ” before civil society was founded, must have been terrible. Every man would have been the enemy of every other man, a “war of each against all. ” Humans would live in savage squalor with “no arts; no letters; no society; and which is worst of all, continual fear, and danger of violent death; and the life of man, solitary, poor, nasty, brutish, and short. ” People rationally join together to form civil society. Society thus arises naturally out of fear.

Hobbes imagined that life in “the state of nature, ” before civil society was founded, must have been terrible. Every man would have been the enemy of every other man, a “war of each against all. ” Humans would live in savage squalor with “no arts; no letters; no society; and which is worst of all, continual fear, and danger of violent death; and the life of man, solitary, poor, nasty, brutish, and short. ” People rationally join together to form civil society. Society thus arises naturally out of fear.

John Locke In contrast to Hobbes he argued that the original state of nature was not so bad. People lived in equality and tolerance with one another. But they could not secure their property. There was no money, title deeds, or courts of law, so ownership was uncertain. To remedy this, they formed civil society bound with contract (social contract) and thus secured “life, liberty, and property. ” Reason for Civil Society: To Locke is the property rights to Hobbes is the fear of violent death.

John Locke In contrast to Hobbes he argued that the original state of nature was not so bad. People lived in equality and tolerance with one another. But they could not secure their property. There was no money, title deeds, or courts of law, so ownership was uncertain. To remedy this, they formed civil society bound with contract (social contract) and thus secured “life, liberty, and property. ” Reason for Civil Society: To Locke is the property rights to Hobbes is the fear of violent death.

But according to Jean-Jacques Rousseau society can be drastically improved, leading to human freedom and dignity. A just society would be a voluntary community with the general will — to which “particular wills” of individuals and interest groups are subordinate. Societies make people, not the other way around. If people are bad, it is because society made them that way (a view held by many today). A good society, on the other hand, can “force men to be free” if they misbehave. Many see the roots of totalitarianism in Rousseau: the imagined perfect society; the general will, which the dictator claims to know; and the breaking of those who do not cooperate.

But according to Jean-Jacques Rousseau society can be drastically improved, leading to human freedom and dignity. A just society would be a voluntary community with the general will — to which “particular wills” of individuals and interest groups are subordinate. Societies make people, not the other way around. If people are bad, it is because society made them that way (a view held by many today). A good society, on the other hand, can “force men to be free” if they misbehave. Many see the roots of totalitarianism in Rousseau: the imagined perfect society; the general will, which the dictator claims to know; and the breaking of those who do not cooperate.

Marxist theory of State Engels wrote, that it is characteristic to the state to have “relative scarcity of material basis” - condition in which the productivity of labor enables a group of people to produce a surplus, that is, an amount of goods—food, clothes, tools—that is more than enough to enable them to survive, yet not enough to allow everyone to live in true abundance. When productivity reaches such a point, society divides into classes: (a) majority working in exploitative conditions (b) a tiny minority who exploit the majority—that is, appropriate surplus and live in luxury without performing productive labor. The division of society into classes in turn gives rise to the state.

Marxist theory of State Engels wrote, that it is characteristic to the state to have “relative scarcity of material basis” - condition in which the productivity of labor enables a group of people to produce a surplus, that is, an amount of goods—food, clothes, tools—that is more than enough to enable them to survive, yet not enough to allow everyone to live in true abundance. When productivity reaches such a point, society divides into classes: (a) majority working in exploitative conditions (b) a tiny minority who exploit the majority—that is, appropriate surplus and live in luxury without performing productive labor. The division of society into classes in turn gives rise to the state.

The state is a product of society at a certain stage of development and is consequential to: Admission by a society of the fact of insoluble contradiction with itself, and of irreconcilable antagonisms ------- Necessity of political power above society to preserve latter from destruction due to contradictions and antagonisms ------- it then leads to creation of ‘order’ - of a political power put by society above itself which is increasingly alienated from society and becomes a state. In general, the state is controlled by the economically dominant class, enabling it to maintain its control over the exploited classes. The state of antiquity - state of slave owners exploiting slaves. The feudal state - state of nobility exploiting peasant serfs and bondsmen. The modern representative state - capital exploiting wage labour. And in most states in history, the rights of citizens are apportioned according to their wealth.

The state is a product of society at a certain stage of development and is consequential to: Admission by a society of the fact of insoluble contradiction with itself, and of irreconcilable antagonisms ------- Necessity of political power above society to preserve latter from destruction due to contradictions and antagonisms ------- it then leads to creation of ‘order’ - of a political power put by society above itself which is increasingly alienated from society and becomes a state. In general, the state is controlled by the economically dominant class, enabling it to maintain its control over the exploited classes. The state of antiquity - state of slave owners exploiting slaves. The feudal state - state of nobility exploiting peasant serfs and bondsmen. The modern representative state - capital exploiting wage labour. And in most states in history, the rights of citizens are apportioned according to their wealth.

According to Marxists, society is divided into material base (or basis) and a superstructure The base: instruments of production (machines, tools, raw materials), the social classes, and the relations between these classes. The superstructure: political and cultural institutions - the state, churches, schools, etc. , and corresponding ideational realms: politics, religion, science, art, etc. The state is the major element of this superstructure. The nature of the material base - "mode of production, " determines the nature of the superstructure. By extension, the development of the base determines the evolution of the state.

According to Marxists, society is divided into material base (or basis) and a superstructure The base: instruments of production (machines, tools, raw materials), the social classes, and the relations between these classes. The superstructure: political and cultural institutions - the state, churches, schools, etc. , and corresponding ideational realms: politics, religion, science, art, etc. The state is the major element of this superstructure. The nature of the material base - "mode of production, " determines the nature of the superstructure. By extension, the development of the base determines the evolution of the state.

The mode of production in material life determines the general character of the social, political, and spiritual processes of life. The highest form of the state is the democratic republic, in which the capitalist class exercises its power indirectly. The chief strategic task of the working class in the proletarian revolution is to seize state power, to raise itself to the position of ruling class. The working class smashes the capitalist state and builds its own, the dictatorship of the proletariat, in its place, which eradicates the private property of capitalist class and will nationalise every enterprise. When these tasks are fulfilled, the state will wither away.

The mode of production in material life determines the general character of the social, political, and spiritual processes of life. The highest form of the state is the democratic republic, in which the capitalist class exercises its power indirectly. The chief strategic task of the working class in the proletarian revolution is to seize state power, to raise itself to the position of ruling class. The working class smashes the capitalist state and builds its own, the dictatorship of the proletariat, in its place, which eradicates the private property of capitalist class and will nationalise every enterprise. When these tasks are fulfilled, the state will wither away.

Strength of the State Not all states really achieve the civil society ad not all even function as states; some hardly function at all. Just because a country has a flag and sits in the UN does not prove that it is a serious state. Analysts see at least three categories of States, based on the strength: Effective states control and tax their entire territory. Laws are mostly obeyed. Government looks after the general welfare and security. Corruption is fairly minor. Effective states tend to be better off and to collect considerable taxes (25 to 50 percent of GDP). Effective states include Japan, the United States, and Western Europe. Some put the best of these states into a “highly effective” category.

Strength of the State Not all states really achieve the civil society ad not all even function as states; some hardly function at all. Just because a country has a flag and sits in the UN does not prove that it is a serious state. Analysts see at least three categories of States, based on the strength: Effective states control and tax their entire territory. Laws are mostly obeyed. Government looks after the general welfare and security. Corruption is fairly minor. Effective states tend to be better off and to collect considerable taxes (25 to 50 percent of GDP). Effective states include Japan, the United States, and Western Europe. Some put the best of these states into a “highly effective” category.

Weak states are characterised by the penetration of crime into politics. You cannot tell where politics leaves off and crime begins. The government does not have the strength to fight lawlessness, drug trafficking, corruption, poverty, and breakaway movements. Justice is bought. Democracy is preached more than practiced and elections often rigged. Little is collected in taxation. Revenues from natural resources, such as Mexico’s and Nigeria’s oil, disappear into private pockets. Much of Asia, Africa, and Latin America are weak states. Failed states have essentially no national government, although some pretend they do. Warlords, militias, and opium growers do as they wish. There is no law besides the gun. Territorial breakup threatens. Education and health standards decline (as in the increase of HIV/AIDS). (Afghanistan, Somalia)

Weak states are characterised by the penetration of crime into politics. You cannot tell where politics leaves off and crime begins. The government does not have the strength to fight lawlessness, drug trafficking, corruption, poverty, and breakaway movements. Justice is bought. Democracy is preached more than practiced and elections often rigged. Little is collected in taxation. Revenues from natural resources, such as Mexico’s and Nigeria’s oil, disappear into private pockets. Much of Asia, Africa, and Latin America are weak states. Failed states have essentially no national government, although some pretend they do. Warlords, militias, and opium growers do as they wish. There is no law besides the gun. Territorial breakup threatens. Education and health standards decline (as in the increase of HIV/AIDS). (Afghanistan, Somalia)

Questions? 1. What is State? What are main historical factors for the emergence of modern state? 2. Major theories of state 3. Machiavelli - why he is called a realist? 4. Social contract - definition and origins 5. Types of state systems J. S. Mc. Clelland

Questions? 1. What is State? What are main historical factors for the emergence of modern state? 2. Major theories of state 3. Machiavelli - why he is called a realist? 4. Social contract - definition and origins 5. Types of state systems J. S. Mc. Clelland

References and reading for seminar 6 1. Garfield Gettel (1911) Readings in Political Science. 2. Kelly (2011) Introduction to modern political thought. 3. Mc. Clelland, J. S. (2008) A History of Western Political Thought. 4. Minogue (2000) Politics - A very short introduction. 5. Niccolo Machiavelli (1513) The Prince/ Il Principe. The Harvard Classics. 1909 -14. 6. Roskin et al. (2012) Political Science - An Introduction (12 th Edition) 7. Tabor, R. - The Marxist Theory of the State, Spunk. org, http: //www. spunk. org/texts/pubs/lr/sp 001715/marxron. html

References and reading for seminar 6 1. Garfield Gettel (1911) Readings in Political Science. 2. Kelly (2011) Introduction to modern political thought. 3. Mc. Clelland, J. S. (2008) A History of Western Political Thought. 4. Minogue (2000) Politics - A very short introduction. 5. Niccolo Machiavelli (1513) The Prince/ Il Principe. The Harvard Classics. 1909 -14. 6. Roskin et al. (2012) Political Science - An Introduction (12 th Edition) 7. Tabor, R. - The Marxist Theory of the State, Spunk. org, http: //www. spunk. org/texts/pubs/lr/sp 001715/marxron. html