86a48bfff92da0eaaccb9ca9a0f26e62.ppt

- Количество слайдов: 64

Stability and Control of Microwave Propelled Sails This work is supported by JPL Contract No. : 1215608. MSI-JPL-UCI-UNM 1

INTRODUCTION This Talk is concerned with the stability of carbon fiber sail structures being studied in a series of experiments at the Jet Propulsion Laboratory (JPL), and UCI by a team led by Microwave Sciences, Inc. The passive dynamic stability in the onedimensional (1 -D) case is most easily understood in terms of the fixed points of the trajectories for the governing equations of 2 MSI-JPL-UCI-UNM motion.

INTRODUCTION (cont) The simple 1 -D model introduces the possibility of controlling a microwave-propelled sail using various nonlinear control strategies. This work will be extended in the future to control the full 3 -D case. In addition to providing guidance to ongoing and near term proof-of-principle experiments, this work will lead to novel strategies for enabling a feedback power controller to maintain a sail fixed at a predetermined height. MSI-JPL-UCI-UNM 3

MICROWAVE PROPULSION Microwave-propelled sails belong to a class of spacecraft that promises to revolutionize future space travel. As an example, NASA's Gossamer Spacecraft Initiative focuses on developing spacecraft architectures for very large, ultra-lightweight apertures and structures. A goal of this initiative is to achieve breakthrough enhancements in mission capability and reductions in mission cost, primarily through revolutionary advances in MSI-JPL-UCI-UNM 4 structures, materials, optics, and adaptive and

SAILS, AND SAILS…. . Solar and other types of sails will provide lowcost propulsion, station-keeping in unstable orbits, and precursor interstellar exploration missions. For a general introduction to solar sails and similar structures the reader is referred to Mc. Innes (1999). For an introduction to the notion of beamed microwave power and its application to space propulsion the reader is referred to Benford (1995). This talk is concerned specifically with the MSI-JPL-UCI-UNM stability and control of carbon fiber sails 5

BEAM RIDING The notion of beam-riding, i. e. , the stable flight of a sail propelled by Poynting flux, places considerable demands upon a sail. Even if the beam is steady, a sail can wander off the beam if its shape becomes deformed, or if it does not have enough spin to keep its angular momentum aligned with the beam direction in the face of perturbations. Generally, sails without structural elements cannot be flown if they are convex toward the beam, as the beam pressure would cause 6 them to collapse. MSI-JPL-UCI-UNM

SAIL SHAPES & CONTROL On the other hand, the beam pressure keeps concave shapes in tension, so concave shapes arise naturally while beam riding. They will resist sidewise motions if the beam moves off center, since a net sideways force restores the sail to its position. We concentrate on a conical shape for the sail and study its dynamics in 1 -D. We will illustrate that such conical shapes will oscillate in 1 -D when a constant microwave power beam is used, then present various MSI-JPL-UCI-UNM feedback controllers to show to stabilize 7

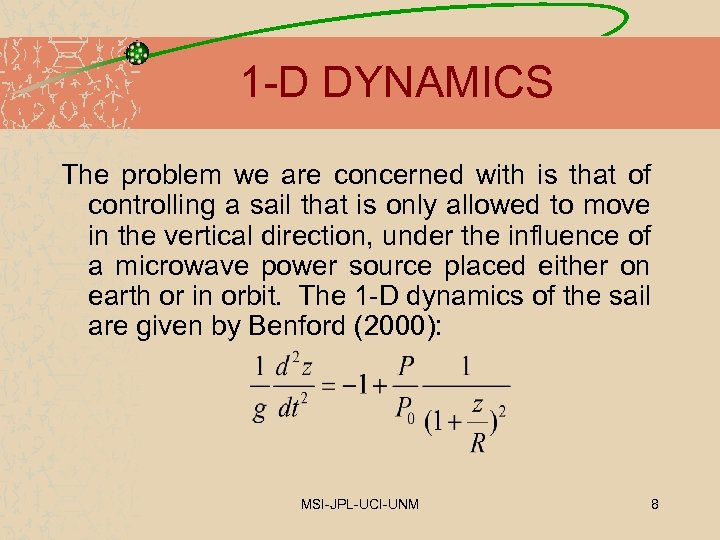

1 -D DYNAMICS The problem we are concerned with is that of controlling a sail that is only allowed to move in the vertical direction, under the influence of a microwave power source placed either on earth or in orbit. The 1 -D dynamics of the sail are given by Benford (2000): MSI-JPL-UCI-UNM 8

1 -D DYNAMICS (cont) Where: g is the acceleration of gravity (in the appropriate units), P 0 is the power necessary to overcome gravity, z is the height or elevation referenced to z=0, R is the beam radius, is half of the total beam opening angle, and is the angle at which the microwave photons strike the sail. MSI-JPL-UCI-UNM 9

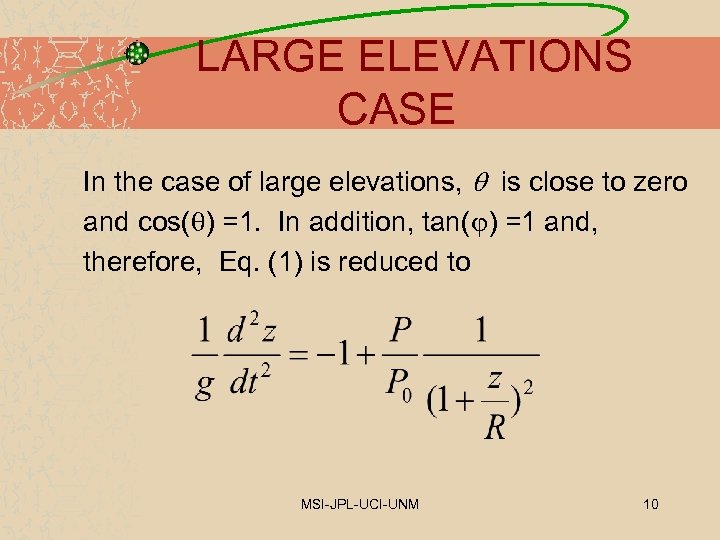

LARGE ELEVATIONS CASE In the case of large elevations, is close to zero and cos( ) =1. In addition, tan( ) =1 and, therefore, Eq. (1) is reduced to MSI-JPL-UCI-UNM 10

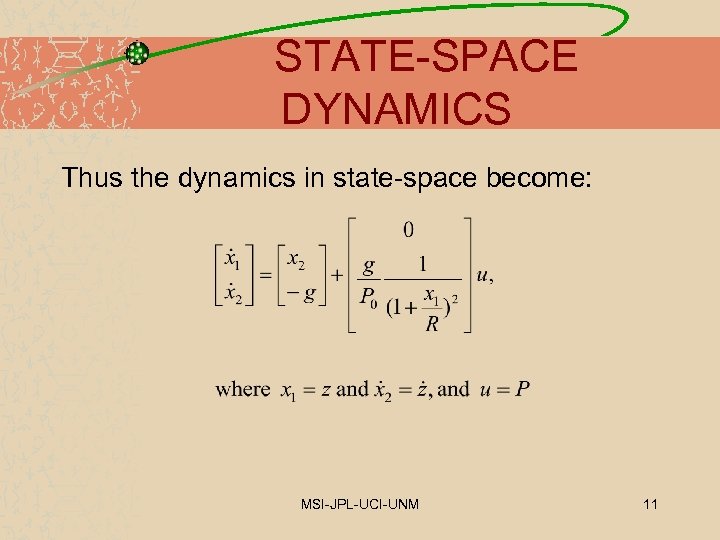

STATE-SPACE DYNAMICS Thus the dynamics in state-space become: MSI-JPL-UCI-UNM 11

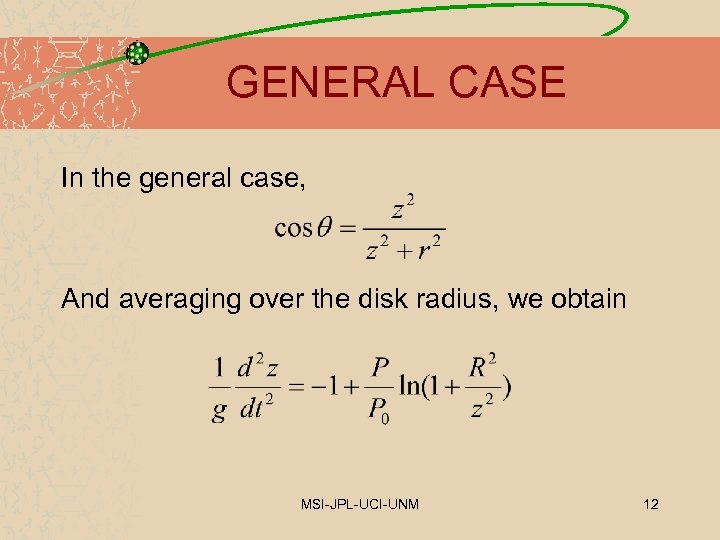

GENERAL CASE In the general case, And averaging over the disk radius, we obtain MSI-JPL-UCI-UNM 12

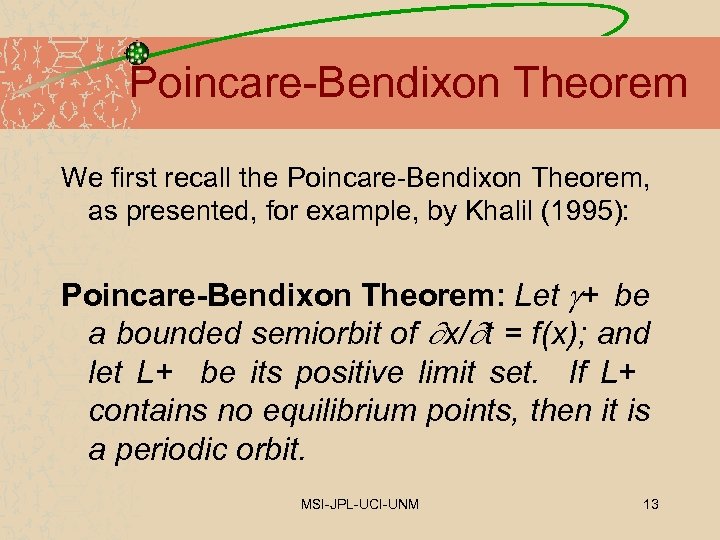

Poincare-Bendixon Theorem We first recall the Poincare-Bendixon Theorem, as presented, for example, by Khalil (1995): Poincare-Bendixon Theorem: Let + be a bounded semiorbit of x/ t = f(x); and let L+ be its positive limit set. If L+ contains no equilibrium points, then it is a periodic orbit. MSI-JPL-UCI-UNM 13

PERIODIC ORBITS We will use this theorem to show that for a constant input power P in the system Eq. (3), there exists a closed bounded set that is positively invariant (i. e. , any solution that starts in M remains in M for all later times), and does not contain any equilibrium points of Eq. (3). Then we deduce that since M is closed, the positive limit set L+ is in M. The Poincare. Bendixon theorem then guarantees the MSI-JPL-UCI-UNM 14 existence of a periodic orbit for Eq. (3).

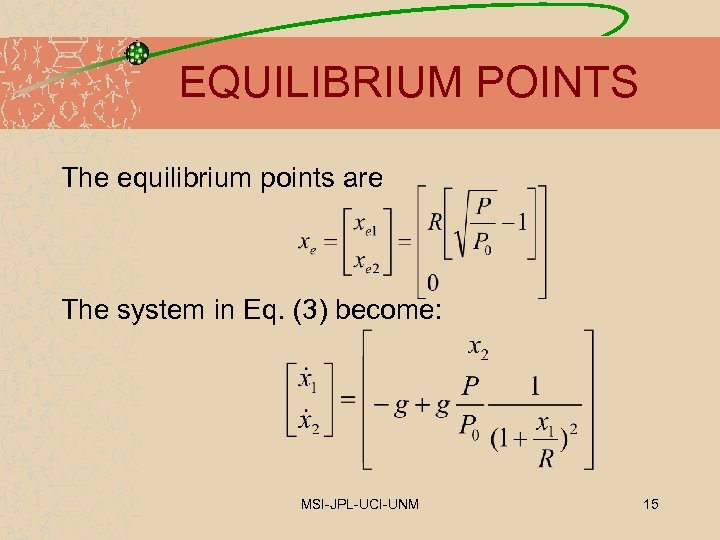

EQUILIBRIUM POINTS The equilibrium points are The system in Eq. (3) become: MSI-JPL-UCI-UNM 15

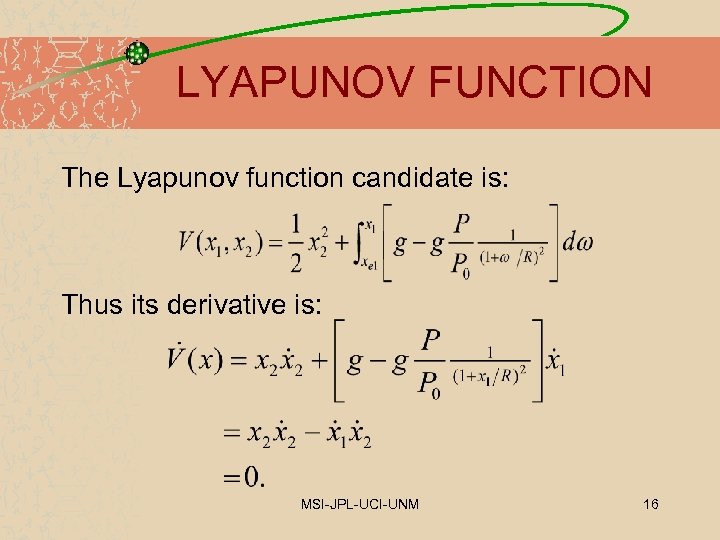

LYAPUNOV FUNCTION The Lyapunov function candidate is: Thus its derivative is: MSI-JPL-UCI-UNM 16

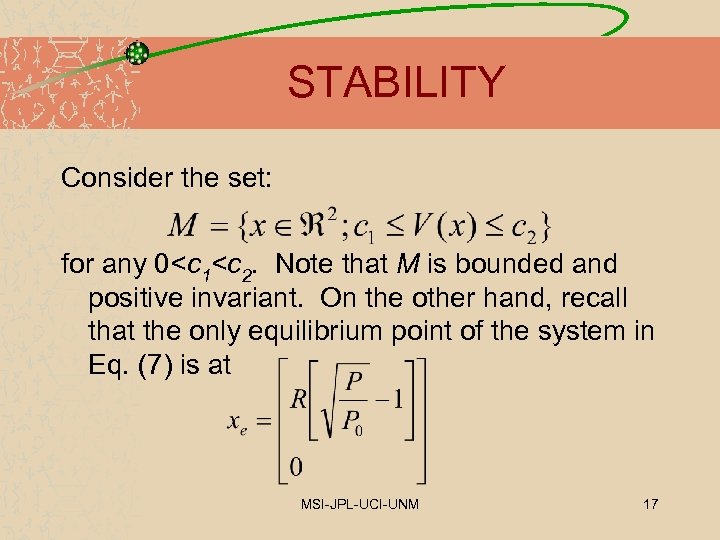

STABILITY Consider the set: for any 0<c 1<c 2. Note that M is bounded and positive invariant. On the other hand, recall that the only equilibrium point of the system in Eq. (7) is at MSI-JPL-UCI-UNM 17

STABILITY (cont) The equilibrium point is outside the set M since V(xe) = V(xe 1, 0) = 0. Thus, calling on the Poincare-Bendixon theorem, we conclude that M contains a periodic orbit which is stable. MSI-JPL-UCI-UNM 18

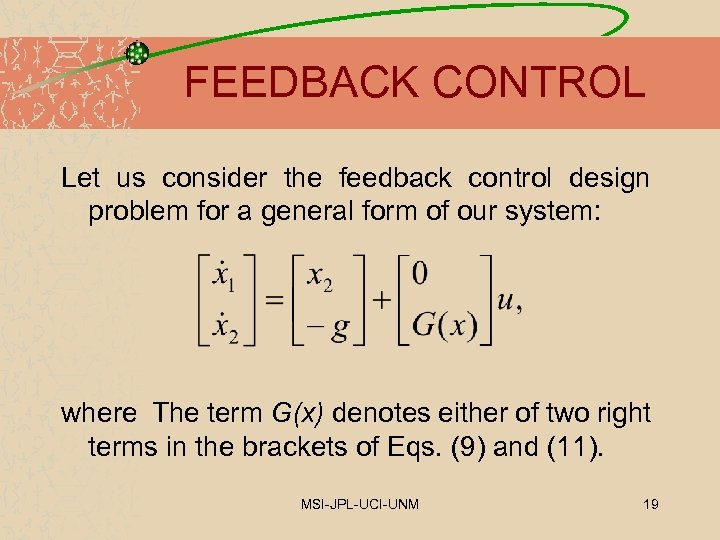

FEEDBACK CONTROL Let us consider the feedback control design problem for a general form of our system: where The term G(x) denotes either of two right terms in the brackets of Eqs. (9) and (11). MSI-JPL-UCI-UNM 19

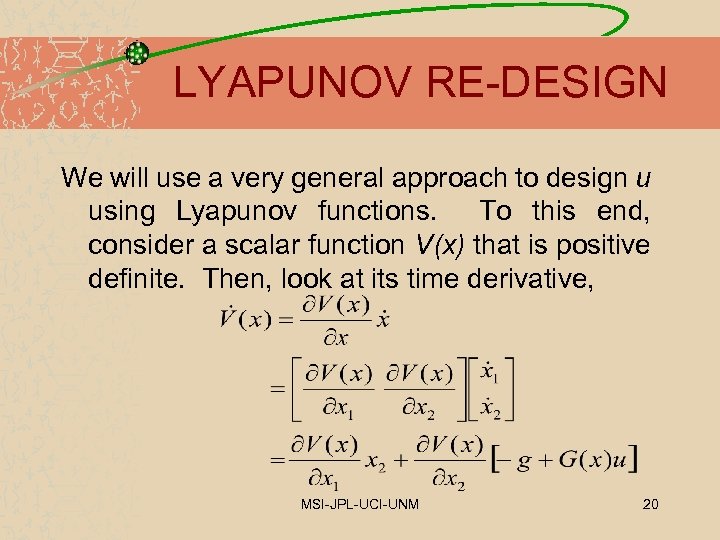

LYAPUNOV RE-DESIGN We will use a very general approach to design u using Lyapunov functions. To this end, consider a scalar function V(x) that is positive definite. Then, look at its time derivative, MSI-JPL-UCI-UNM 20

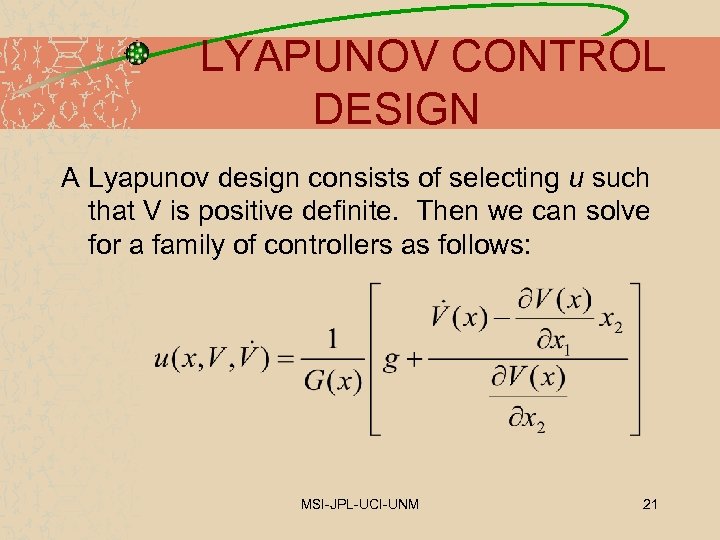

LYAPUNOV CONTROL DESIGN A Lyapunov design consists of selecting u such that V is positive definite. Then we can solve for a family of controllers as follows: MSI-JPL-UCI-UNM 21

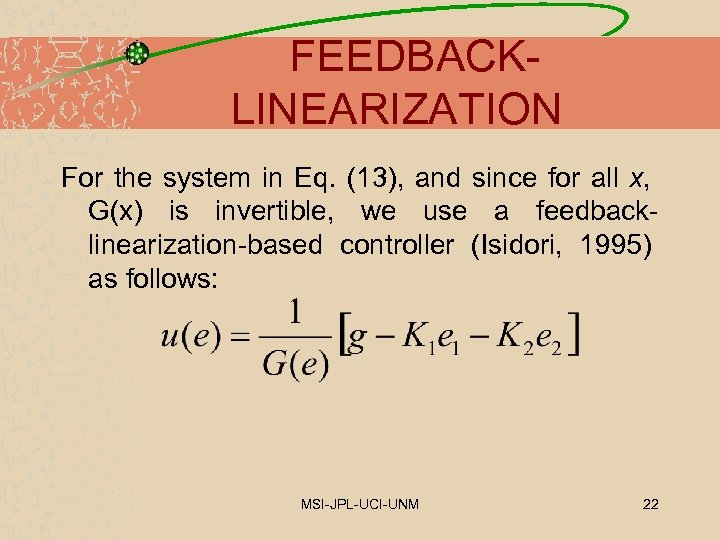

FEEDBACKLINEARIZATION For the system in Eq. (13), and since for all x, G(x) is invertible, we use a feedbacklinearization-based controller (Isidori, 1995) as follows: MSI-JPL-UCI-UNM 22

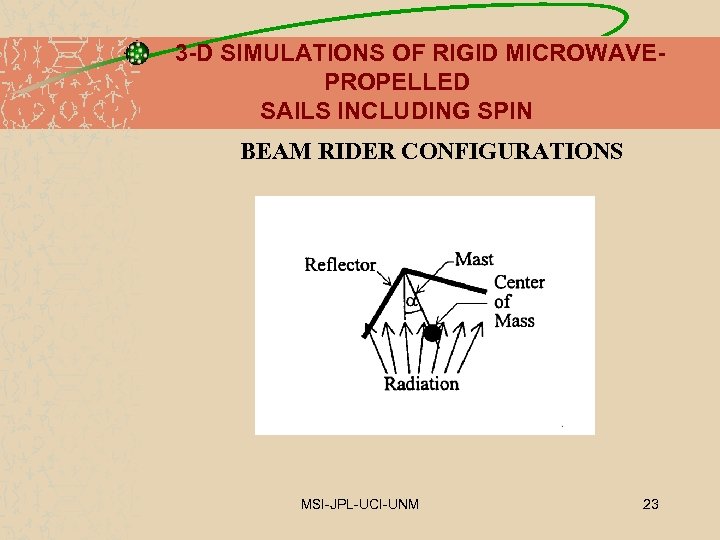

3 -D SIMULATIONS OF RIGID MICROWAVEPROPELLED SAILS INCLUDING SPIN BEAM RIDER CONFIGURATIONS MSI-JPL-UCI-UNM 23

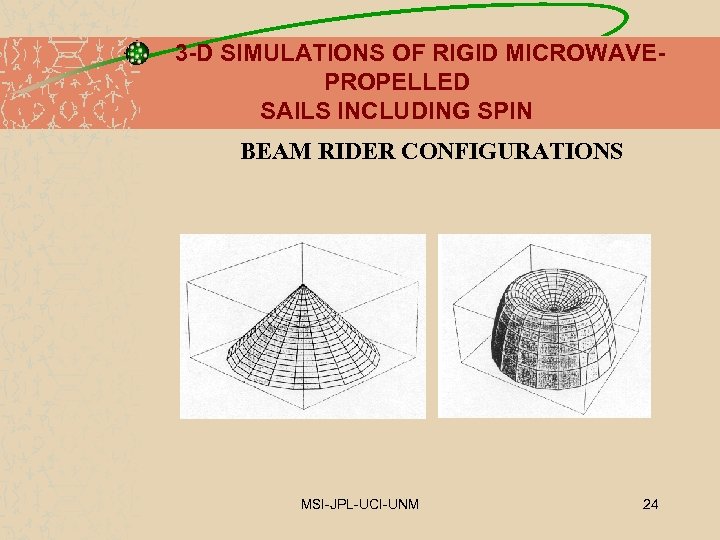

3 -D SIMULATIONS OF RIGID MICROWAVEPROPELLED SAILS INCLUDING SPIN BEAM RIDER CONFIGURATIONS MSI-JPL-UCI-UNM 24

3 -D SIMULATIONS OF RIGID MICROWAVEPROPELLED SAILS INCLUDING SPIN MODEL ASSUMPTIONS a) The vehicle possesses a large reflecting crosssection facing the incident microwave radiation. The vehicle mass distribution is such that the center-of-mass is located between the reflector and the radiation source. b) The reflector is a rigid body. c) The mast neither absorbs nor reflects any of the incident radiation. MSI-JPL-UCI-UNM 25

3 -D SIMULATIONS OF RIGID MICROWAVEPROPELLED SAILS INCLUDING SPIN MODEL ASSUMPTIONS (Cont’d) d) There are no internal reflections. (This is quantified in the simulation code by limiting the beam rider’s conical half angle to less than 30. ) e) The reflector cross section orthogonal to the incident radiation is elliptical in general. f) The reflector shape resembles an elliptical cone (per assumption e)). This simplifies the number of parameters needed to describe the configuration. MSI-JPL-UCI-UNM 26

3 -D SIMULATIONS OF RIGID MICROWAVEPROPELLED SAILS INCLUDING SPIN MODEL ASSUMPTIONS (Cont’d) g) The beam rider is operating in a uniform gravitational environment (1 -g). h) Aerodynamic influences are not considered. i) The incident Poynting flux varies as inverse square to the distance away from the source. j) The microwave source is an ideal point source. k) Perfect reflections take place at the beam rider (reflector) surface. MSI-JPL-UCI-UNM 27

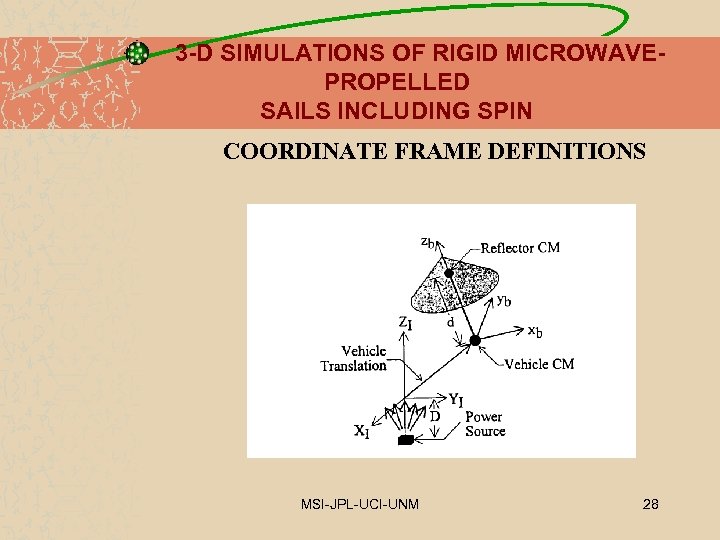

3 -D SIMULATIONS OF RIGID MICROWAVEPROPELLED SAILS INCLUDING SPIN COORDINATE FRAME DEFINITIONS MSI-JPL-UCI-UNM 28

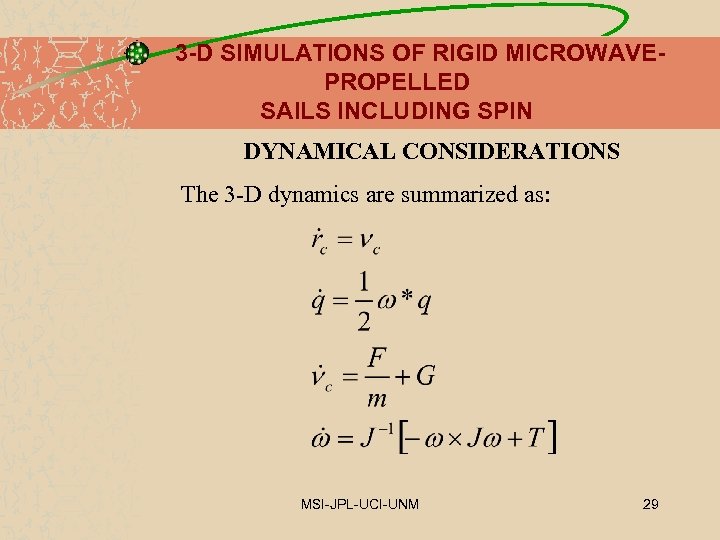

3 -D SIMULATIONS OF RIGID MICROWAVEPROPELLED SAILS INCLUDING SPIN DYNAMICAL CONSIDERATIONS The 3 -D dynamics are summarized as: MSI-JPL-UCI-UNM 29

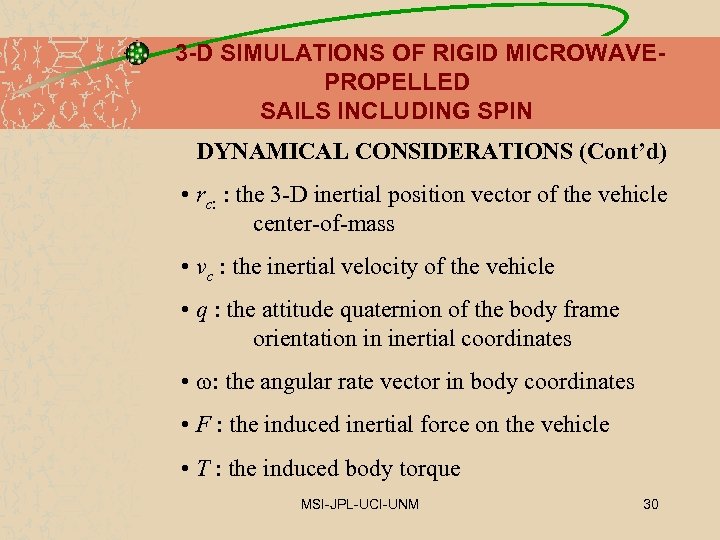

3 -D SIMULATIONS OF RIGID MICROWAVEPROPELLED SAILS INCLUDING SPIN DYNAMICAL CONSIDERATIONS (Cont’d) • rc: : the 3 -D inertial position vector of the vehicle center-of-mass • vc : the inertial velocity of the vehicle • q : the attitude quaternion of the body frame orientation in inertial coordinates • : the angular rate vector in body coordinates • F : the induced inertial force on the vehicle • T : the induced body torque MSI-JPL-UCI-UNM 30

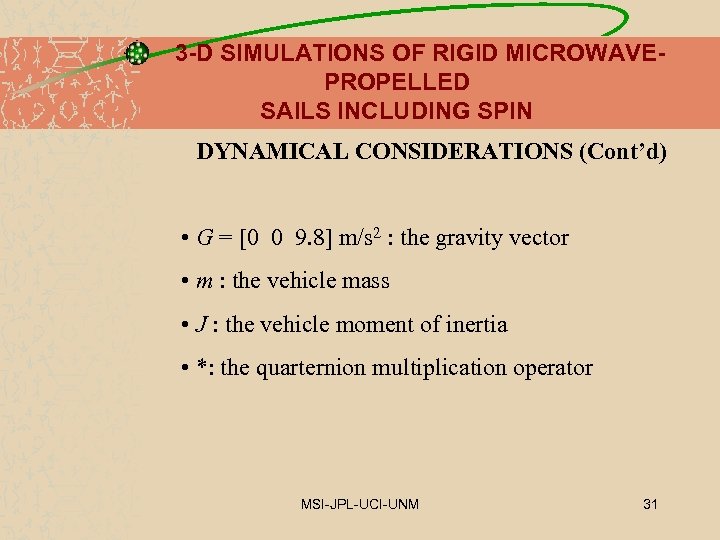

3 -D SIMULATIONS OF RIGID MICROWAVEPROPELLED SAILS INCLUDING SPIN DYNAMICAL CONSIDERATIONS (Cont’d) • G = [0 0 9. 8] m/s 2 : the gravity vector • m : the vehicle mass • J : the vehicle moment of inertia • *: the quarternion multiplication operator MSI-JPL-UCI-UNM 31

3 -D SIMULATIONS OF RIGID MICROWAVEPROPELLED SAILS INCLUDING SPIN DYNAMICAL CONSIDERATIONS (Cont’d) …and MSI-JPL-UCI-UNM 32

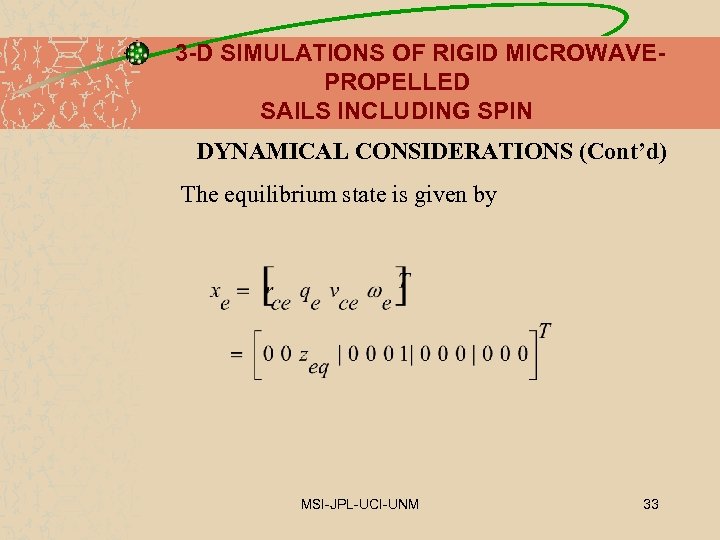

3 -D SIMULATIONS OF RIGID MICROWAVEPROPELLED SAILS INCLUDING SPIN DYNAMICAL CONSIDERATIONS (Cont’d) The equilibrium state is given by MSI-JPL-UCI-UNM 33

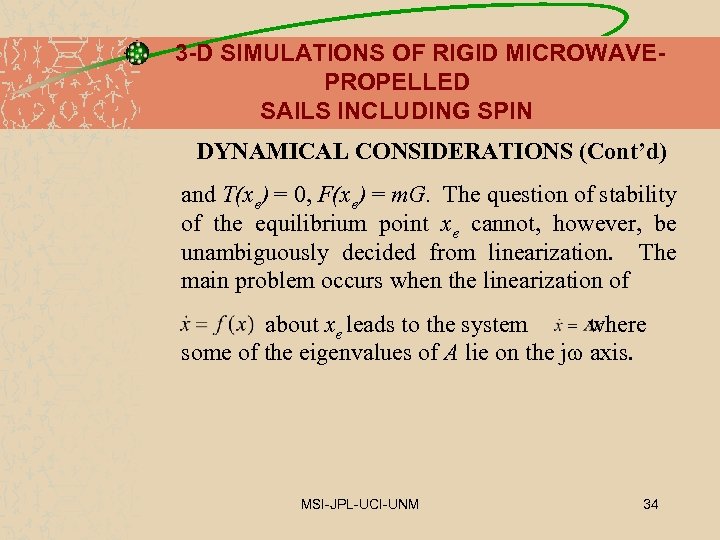

3 -D SIMULATIONS OF RIGID MICROWAVEPROPELLED SAILS INCLUDING SPIN DYNAMICAL CONSIDERATIONS (Cont’d) and T(xe) = 0, F(xe) = m. G. The question of stability of the equilibrium point xe cannot, however, be unambiguously decided from linearization. The main problem occurs when the linearization of about xe leads to the system where some of the eigenvalues of A lie on the j axis. MSI-JPL-UCI-UNM 34

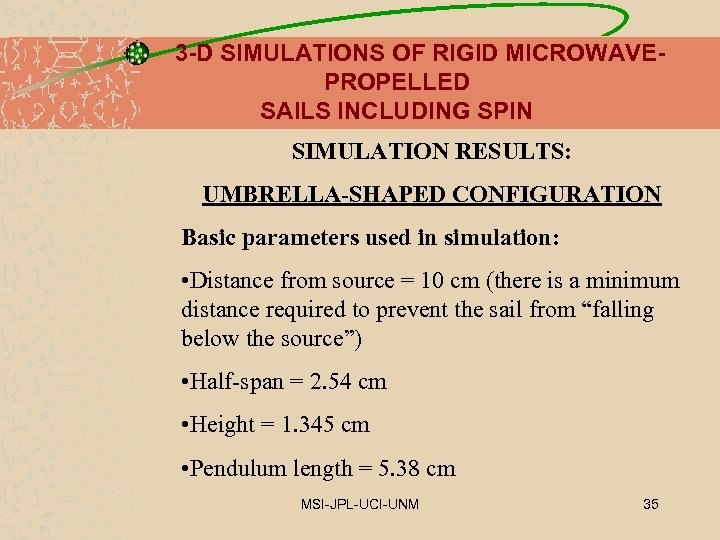

3 -D SIMULATIONS OF RIGID MICROWAVEPROPELLED SAILS INCLUDING SPIN SIMULATION RESULTS: UMBRELLA-SHAPED CONFIGURATION Basic parameters used in simulation: • Distance from source = 10 cm (there is a minimum distance required to prevent the sail from “falling below the source”) • Half-span = 2. 54 cm • Height = 1. 345 cm • Pendulum length = 5. 38 cm MSI-JPL-UCI-UNM 35

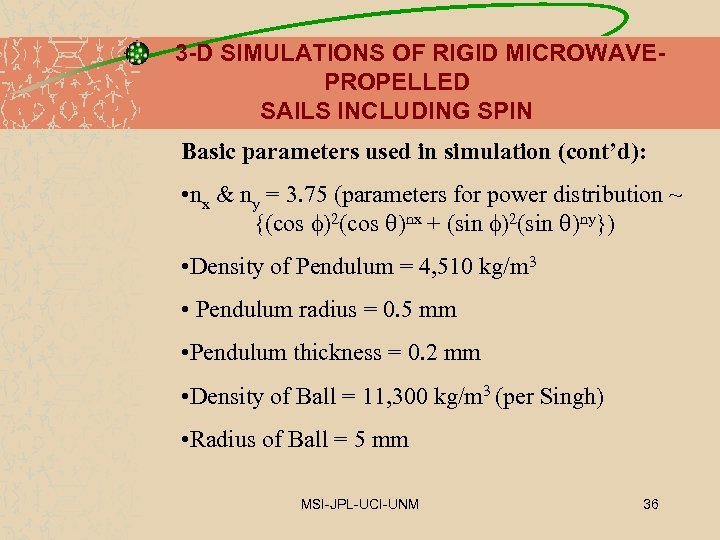

3 -D SIMULATIONS OF RIGID MICROWAVEPROPELLED SAILS INCLUDING SPIN Basic parameters used in simulation (cont’d): • nx & ny = 3. 75 (parameters for power distribution ~ {(cos )2(cos )nx + (sin )2(sin )ny}) • Density of Pendulum = 4, 510 kg/m 3 • Pendulum radius = 0. 5 mm • Pendulum thickness = 0. 2 mm • Density of Ball = 11, 300 kg/m 3 (per Singh) • Radius of Ball = 5 mm MSI-JPL-UCI-UNM 36

3 -D SIMULATIONS OF RIGID MICROWAVEPROPELLED SAILS INCLUDING SPIN Basic parameters used in simulation (cont’d): • Sail mass = 0. 197 g • Mass of the entire system = 6. 114 g • Surface area = 22. 9 cm 2 • Average power needed for levitation 680 MW • Spin rates studied: 0°/s, 1000°/s, and 2000°/s MATLAB®-Generated Movie Using Simulation Data Displaying Stable and Unstable Examples for Umbrella-Shaped Sail MSI-JPL-UCI-UNM 37

3 -D SIMULATIONS OF RIGID MICROWAVEPROPELLED SAILS INCLUDING SPIN Analysis of Umbrella Configuration Stability: • A gradient in the power distribution is required for stability (a certain fall-off is needed in order for the restoring force to overcome the radial destabilizing force) • Minimum pendulum length required (5. 3 cm for our parameters – determines center-of-mass) • Only certain sail heights are stable, determined by angular range of 25°-29° • Spin does not help – because pendulum and payload dominate the dynamics MSI-JPL-UCI-UNM 38

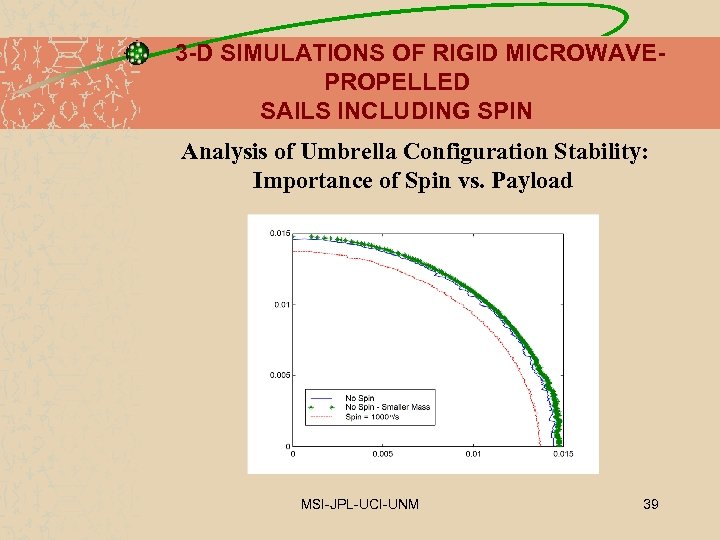

3 -D SIMULATIONS OF RIGID MICROWAVEPROPELLED SAILS INCLUDING SPIN Analysis of Umbrella Configuration Stability: Importance of Spin vs. Payload MSI-JPL-UCI-UNM 39

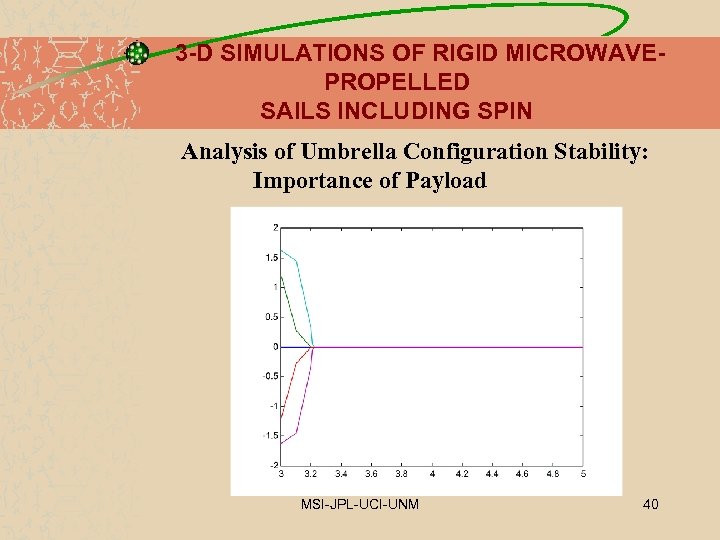

3 -D SIMULATIONS OF RIGID MICROWAVEPROPELLED SAILS INCLUDING SPIN Analysis of Umbrella Configuration Stability: Importance of Payload MSI-JPL-UCI-UNM 40

3 -D SIMULATIONS OF RIGID MICROWAVEPROPELLED SAILS INCLUDING SPIN SIMULATION RESULTS: UPSIDE DOWN CONFIGURATION Basic parameters used in simulation: Same as previous case, except no pendulum or payload. Why consider this case? May have some mission advantages with payload placement in center of sail. MATLAB®-Generated Movie Using Simulation Data Displaying Unstable Examples for Upside Down Sail MSI-JPL-UCI-UNM 41

3 -D SIMULATIONS OF RIGID MICROWAVEPROPELLED SAILS INCLUDING SPIN Analysis of Upside Down Configuration Stability: • In order for there to be a restoring force, the sail needs to be tilted in such a manner that the force on the outer edge will be more radial then that on the inner edge MSI-JPL-UCI-UNM 42

3 -D SIMULATIONS OF RIGID MICROWAVEPROPELLED SAILS INCLUDING SPIN Analysis of Upside Down Configuration Stability (Cont’d): • In order for there to be a restoring force, the sail needs to be tilted in such a manner that the force on the outer edge will be more radial then that on the inner edge Advantages of upside down sail: • Plane wave favorable to stability • Pendulum not required MSI-JPL-UCI-UNM 43

3 -D SIMULATIONS OF RIGID MICROWAVEPROPELLED SAILS INCLUDING SPIN Analysis of Upside Down Configuration Stability (Cont’d): Disadvantages of upside down sail: • No stable region identified – stability would require that the sail follow an exact attitude pattern above the source • Spin exacerbates sail tendency to spin away MSI-JPL-UCI-UNM 44

CONCLUSIONS v Stability of 1 -D sails is studied analytically using Lyapunov theory v Constant power causes oscillations v Various possible feedback designs to guarantee stability v 3 -D case much more complicated but Lyapunov approach possible for 3 -D. MSI-JPL-UCI-UNM 45

3 -D SIMULATIONS OF RIGID MICROWAVEPROPELLED SAILS INCLUDING SPIN CONCLUSIONS AND PLANS FOR FUTURE WORK • Stable regions for umbrella-shaped sail identified – dimensions of sail comparable to those planned in experiments • Stability achieved by location of center-of-mass • Need to identify stability regions with shorter pendulum and lighter payload • Provide guidance to U. C. Irvine experiments MSI-JPL-UCI-UNM 46

3 -D SIMULATIONS OF RIGID MICROWAVEPROPELLED SAILS INCLUDING SPIN CONCLUSIONS AND PLANS FOR FUTURE WORK • Use concepts from Iterative Learning Control Theory to select simulation regions and run fewer cases • Allow for simulation studies to be executed within MATLAB® environment to speed turnaround MSI-JPL-UCI-UNM 47

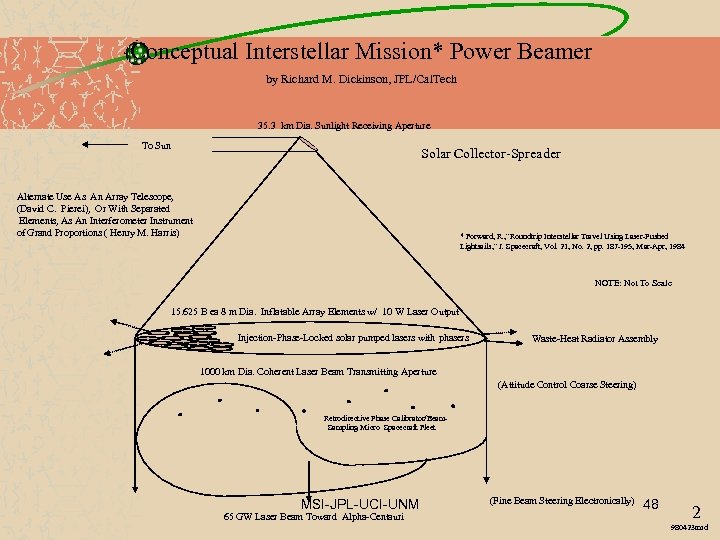

Conceptual Interstellar Mission* Power Beamer by Richard M. Dickinson, JPL/Cal. Tech 35. 3 km Dia. Sunlight Receiving Aperture To Sun Solar Collector-Spreader Alternate Use As An Array Telescope, (David C. Pierei), Or With Separated Elements, As An Interferometer Instrument of Grand Proportions ( Henry M. Harris) * Forward, R. , ”Roundtrip Interstellar Travel Using Laser-Pushed Lightsails, ” J. Spacecraft, Vol. 21, No. 2, pp. 187 -195, Mar-Apr, 1984 NOTE: Not To Scale 15. 625 B ea 8 m Dia. Inflatable Array Elements w/ 10 W Laser Output Injection-Phase-Locked solar pumped lasers with phasers Waste-Heat Radiator Assembly 1000 km Dia. Coherent Laser Beam Transmitting Aperture (Attitude Control Coarse Steering) Retrodirective Phase Calibrator/Beam Sampling Micro Spacecraft Fleet MSI-JPL-UCI-UNM 65 GW Laser Beam Toward Alpha-Centauri (Fine Beam Steering Electronically) 48 2 980423 rmd

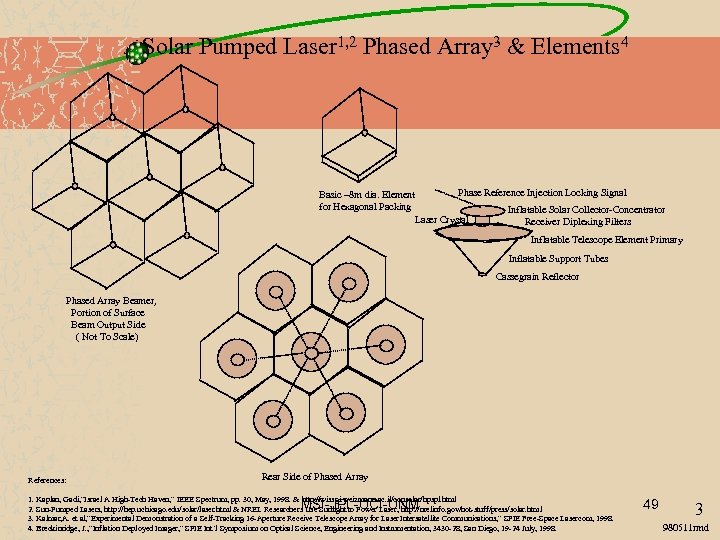

Solar Pumped Laser 1, 2 Phased Array 3 & Elements 4 Phase Reference Injection Locking Signal Basic ~8 m dia. Element for Hexagonal Packing Inflatable Solar Collector-Concentrator Laser Crystal Receiver Diplexing Filters Inflatable Telescope Element Primary Inflatable Support Tubes Cassegrain Reflector Phased Array Beamer, Portion of Surface Beam Output Side ( Not To Scale) References: Rear Side of Phased Array 1. Kaplan, Gadi, ”Israel A High-Tech Haven, ” IEEE Spectrum, pp. 30, May, 1998. & http: //wissgi. weizmann. ac. il/consolar/hpspl. html 2. Sun-Pumped Lasers, http: //hep. uchicago. edu/solar/laser. html & NREL Researchers Use Sunlight to Power Laser, http: //nrelinfo. gov/hot-stuff/press/solar. html 3. Kalmar, A. et al, ”Experimental Demonstration of a Self-Tracking 16 -Aperture Receive Telescope Array for Laser Intersatellite Communications, ” SPIE Free-Space Lasercom, 1998. 4. Breckinridge, J. , ”Inflation Deployed Imager, ” SPIE Int’l Symposium on Optical Science, Engineering and Instrumentation, 3430 -28, San Diego, 19 -24 July, 1998. MSI-JPL-UCI-UNM 49 3 980511 rmd

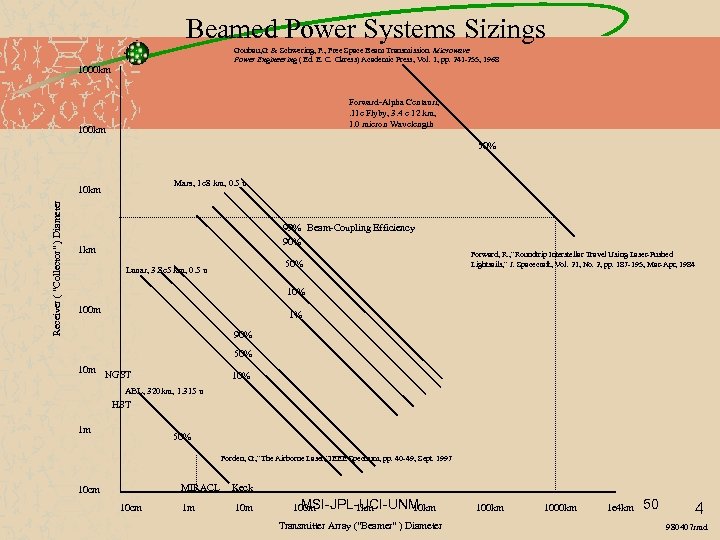

Beamed Power Systems Sizings Goubau, G. & Schwering, F. , Free Space Beam Transmission. Microwave Power Engineering ( Ed. E. C. Okress) Academic Press, Vol. 1, pp. 241 -255, 1968 1000 km Forward-Alpha Centauri, . 11 c Flyby, 3. 4 e 12 km, 1. 0 micron Wavelength 100 km 50% Mars, 1 e 8 km, 0. 5 u Receiver ( “Collector” ) Diameter 10 km 99% Beam-Coupling Efficiency 90% 1 km 50% Lunar, 3. 8 e 5 km, 0. 5 u Forward, R. , ”Roundtrip Interstellar Travel Using Laser-Pushed Lightsails, ” J. Spacecraft, Vol. 21, No. 2, pp. 187 -195, Mar-Apr, 1984 10% 100 m 1% 90% 50% 10 m NGST 10% ABL, 320 km, 1. 315 u HST 1 m 50% Forden, G. , ”The Airborne Laser, ”IEEE Spectrum, pp. 40 -49, Sept. 1997 10 cm MIRACL Keck MSI-JPL-UCI-UNM 10 cm 10 m 100 m 1 km 100 km 1000 km 1 e 4 km Transmitter Array (“Beamer” ) Diameter 50 4 980407 rmd

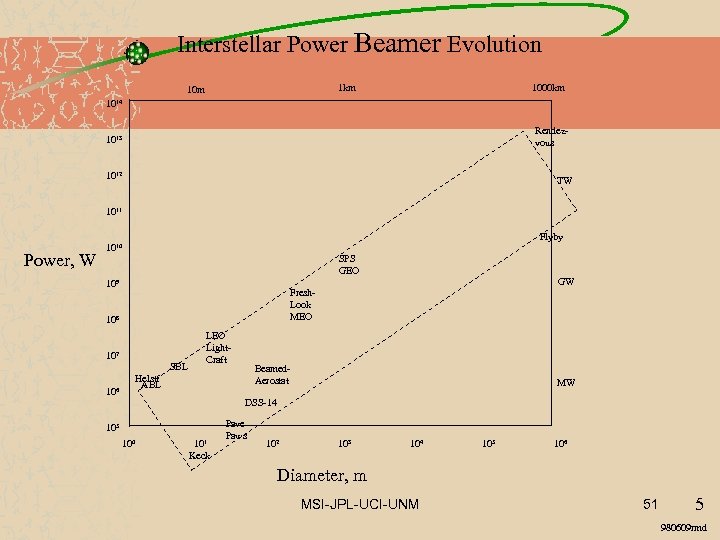

Interstellar Power Beamer Evolution 1 km 1000 km 1014 Rendezvous 1013 1012 TW 1011 Flyby Power, W 1010 SPS GEO 109 108 107 106 GW Fresh. Look MEO SBL LEO Light. Craft Beamed. Aerostat Helstf ABL MW DSS-14 105 100 101 Keck Pave Paws 102 103 104 105 106 Diameter, m MSI-JPL-UCI-UNM 51 5 980609 rmd

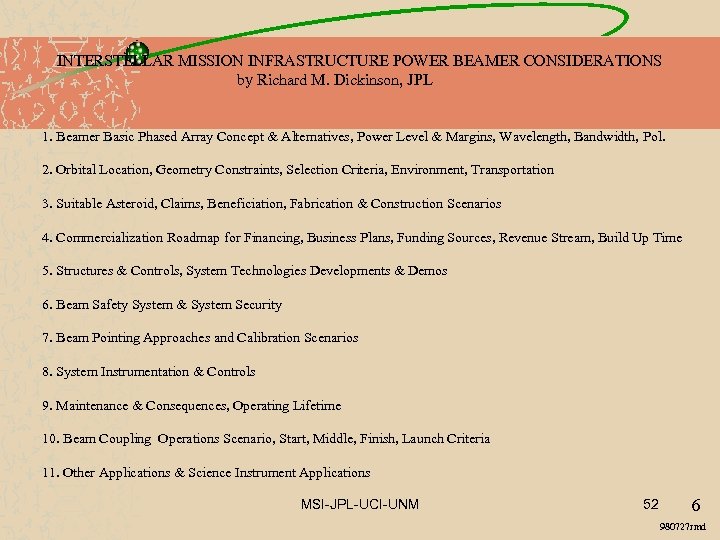

INTERSTELLAR MISSION INFRASTRUCTURE POWER BEAMER CONSIDERATIONS by Richard M. Dickinson, JPL 1. Beamer Basic Phased Array Concept & Alternatives, Power Level & Margins, Wavelength, Bandwidth, Pol. 2. Orbital Location, Geometry Constraints, Selection Criteria, Environment, Transportation 3. Suitable Asteroid, Claims, Beneficiation, Fabrication & Construction Scenarios 4. Commercialization Roadmap for Financing, Business Plans, Funding Sources, Revenue Stream, Build Up Time 5. Structures & Controls, System Technologies Developments & Demos 6. Beam Safety System & System Security 7. Beam Pointing Approaches and Calibration Scenarios 8. System Instrumentation & Controls 9. Maintenance & Consequences, Operating Lifetime 10. Beam Coupling Operations Scenario, Start, Middle, Finish, Launch Criteria 11. Other Applications & Science Instrument Applications MSI-JPL-UCI-UNM 52 6 980727 rmd

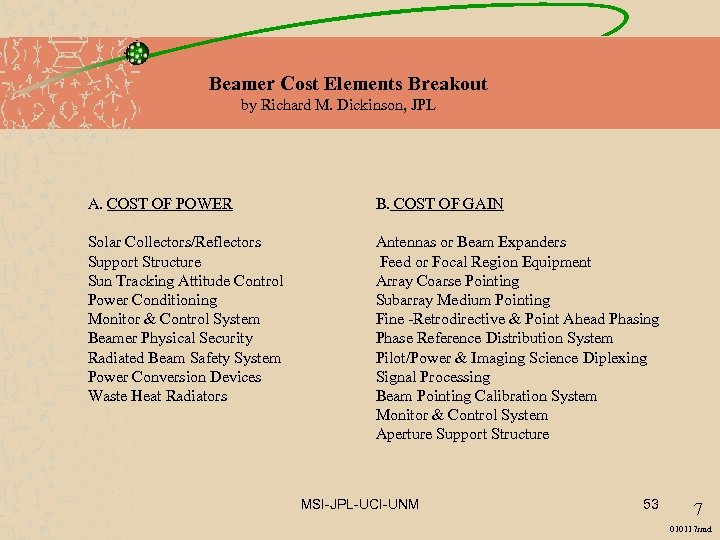

Beamer Cost Elements Breakout by Richard M. Dickinson, JPL A. COST OF POWER B. COST OF GAIN Solar Collectors/Reflectors Support Structure Sun Tracking Attitude Control Power Conditioning Monitor & Control System Beamer Physical Security Radiated Beam Safety System Power Conversion Devices Waste Heat Radiators Antennas or Beam Expanders Feed or Focal Region Equipment Array Coarse Pointing Subarray Medium Pointing Fine -Retrodirective & Point Ahead Phasing Phase Reference Distribution System Pilot/Power & Imaging Science Diplexing Signal Processing Beam Pointing Calibration System Monitor & Control System Aperture Support Structure MSI-JPL-UCI-UNM 53 7 010117 rmd

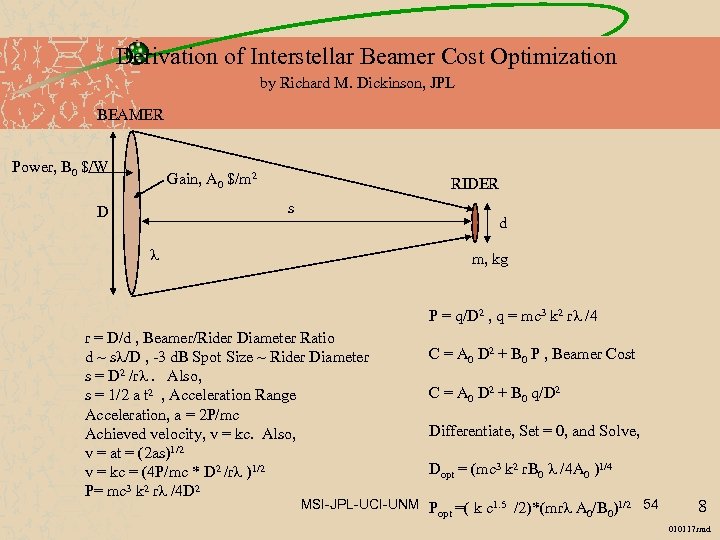

Derivation of Interstellar Beamer Cost Optimization by Richard M. Dickinson, JPL BEAMER Power, B 0 $/W Gain, A 0 $/m 2 RIDER s D d l m, kg P = q/D 2 , q = mc 3 k 2 rl /4 r = D/d , Beamer/Rider Diameter Ratio d ~ sl/D , -3 d. B Spot Size ~ Rider Diameter s = D 2 /rl. Also, s = 1/2 a t 2 , Acceleration Range Acceleration, a = 2 P/mc Achieved velocity, v = kc. Also, v = at = (2 as)1/2 v = kc = (4 P/mc * D 2 /rl )1/2 P= mc 3 k 2 rl /4 D 2 C = A 0 D 2 + B 0 P , Beamer Cost C = A 0 D 2 + B 0 q/D 2 Differentiate, Set = 0, and Solve, Dopt = (mc 3 k 2 r. B 0 l /4 A 0 )1/4 MSI-JPL-UCI-UNM P =( k c 1. 5 /2)*(mrl A /B )1/2 54 opt 0 0 8 010117 rmd

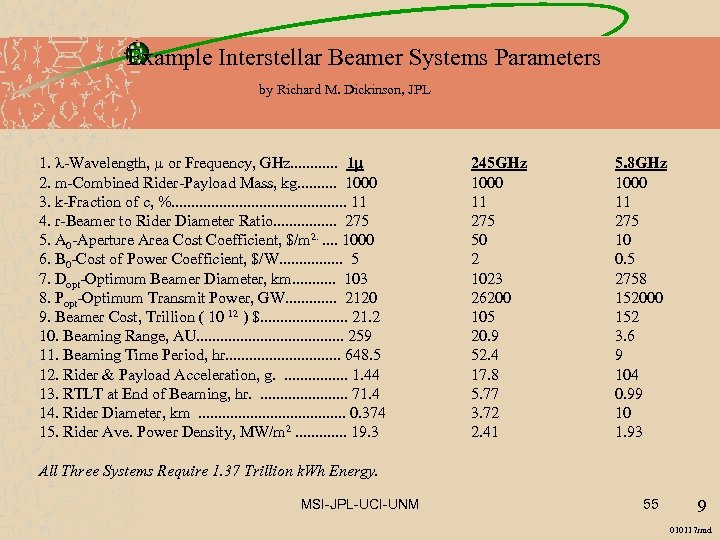

Example Interstellar Beamer Systems Parameters by Richard M. Dickinson, JPL 1. l-Wavelength, m or Frequency, GHz. . . 1 m 2. m-Combined Rider-Payload Mass, kg. . 1000 3. k-Fraction of c, %. . . 11 4. r-Beamer to Rider Diameter Ratio. . . . 275 5. A 0 -Aperture Area Cost Coefficient, $/m 2. . . 1000 6. B 0 -Cost of Power Coefficient, $/W. . . . 5 7. Dopt-Optimum Beamer Diameter, km. . . 103 8. Popt-Optimum Transmit Power, GW. . . 2120 9. Beamer Cost, Trillion ( 10 12 ) $. . . . . 21. 2 10. Beaming Range, AU. . . . . 259 11. Beaming Time Period, hr. . . . 648. 5 12. Rider & Payload Acceleration, g. . . . 1. 44 13. RTLT at End of Beaming, hr. . . 71. 4 14. Rider Diameter, km . . 0. 374 15. Rider Ave. Power Density, MW/m 2. . . 19. 3 245 GHz 1000 11 275 50 2 1023 26200 105 20. 9 52. 4 17. 8 5. 77 3. 72 2. 41 5. 8 GHz 1000 11 275 10 0. 5 2758 152000 152 3. 6 9 104 0. 99 10 1. 93 All Three Systems Require 1. 37 Trillion k. Wh Energy. MSI-JPL-UCI-UNM 55 9 010117 rmd

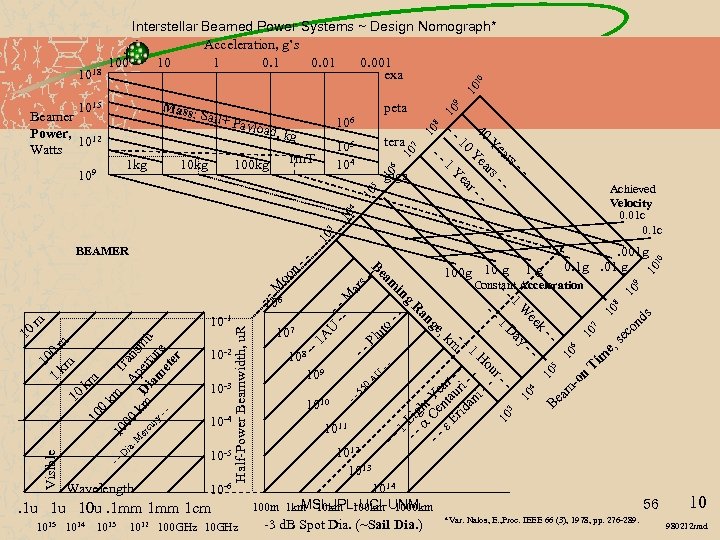

0 10 1 0 8 10 9 1 0 Achieved Velocity 0. 01 c 0. 1 c 10 3 1 04 1 ea 05 s - . 001 g 0. 1 g. 01 g 10 1 0 9 0 8 1 1 10 7 10 6 05 se e , im T n -o m a 1 10 3 A U - - 1 - - Lig a ht - - Ce Ye e nt ar Er au - id ri - an i - - 50 5 - - ds n co Be 1012 1013 1014 MSI-JPL-UCI-UNM 100 m 1 km 100 km 1000 km. 1 u 10 u. 1 mm 1 cm -3 d. B Spot Dia. (~Sail Dia. ) 1015 1014 1013 1012 100 GHz 10 -6 04 - o ut Pl A -- 1 1011 1 -ar s U - -- - M M - Wavelength Half-Power Beamwidth, u. R ia D - - Visible 10 00 0 km T Ap rans. M k D e m er m i rt it cu am ur ry - et e er 10 0 m 10 10 -5 1010 - k ee - W ay 1 D - 1 r - ou 10 -4 108 109 H 1 - km 1 10 -3 e, m k 0 g an 1 R km 10 -2 107 g 1 Constant Acceleration in 10 -1 m 0 am 106 1 g 100 g 10 g Be oo n - - BEAMER 0 Y 1 giga Ye ar - rs ea - r Y 10 7 4 0 tera 105 104 1 m. T 100 kg - - 1 ad, kg - - 10 kg peta 106 - - 1 kg 109 Paylo Sail+ Mass: 1015 Beamer Power, 12 10 Watts 10 6 1018 Interstellar Beamed Power Systems ~ Design Nomograph* Acceleration, g’s 100 1 0. 1 0. 01 0. 001 exa 56 *Var. Nalos, E. , Proc. IEEE 66 (3), 1978, pp. 276 -289. 10 980212 rmd

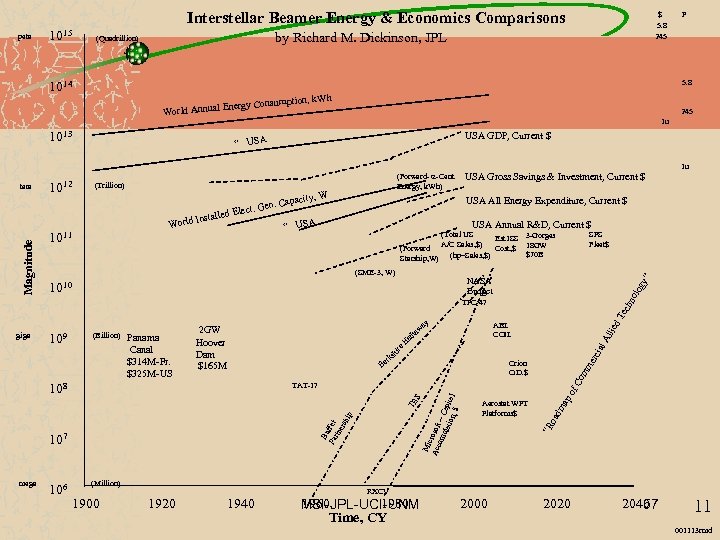

peta 1015 Interstellar Beamer Energy & Economics Comparisons by Richard M. Dickinson, JPL (Quadrillion) $ 5. 8 245 P 5. 8 1014 ption, k. Wh nergy Consum World Annual E 1013 245 1 u USA GDP, Current $ “ USA 1 u (Trillion) Magnitude nstal World I 1011 ty, W USA All Energy Expenditure, Current $ “ USA Annual R&D, Current $ (Total US Est ISS 3 -Gorges A/C Sales, $) Cost, $ 18 GW (Forward $70 B (hp=Sales, $) Starship, W) (SME-3, W) SPS Fleet$ NASA Budget 1010 y” Capaci . ct. Gen led Ele log 1012 USA Gross Savings & Investment, Current $ no tera (Forward- a-Cent. Energy, k. Wh) 108 Al lie d T Orion O. D. $ B (Million) 1900 1920 1940 RXCV of ap dm Aerostat WPT Platforms$ oa Bu Pa ffet rtn ers hip TB 106 erc i r i sh k er TAT-1? 107 mega ABL COIL al ha at H e mm Panama Canal $314 M-Fr. $325 M-US ay w 2 GW Hoover Dam $165 M Co (Billion) “R 109 S Mi cro s Ac cum oft ~ ula Cap tion ital , $ giga ech TPC-4? 1960 1980 MSI-JPL-UCI-UNM 2000 2020 2040 57 Time, CY 11 001113 rmd

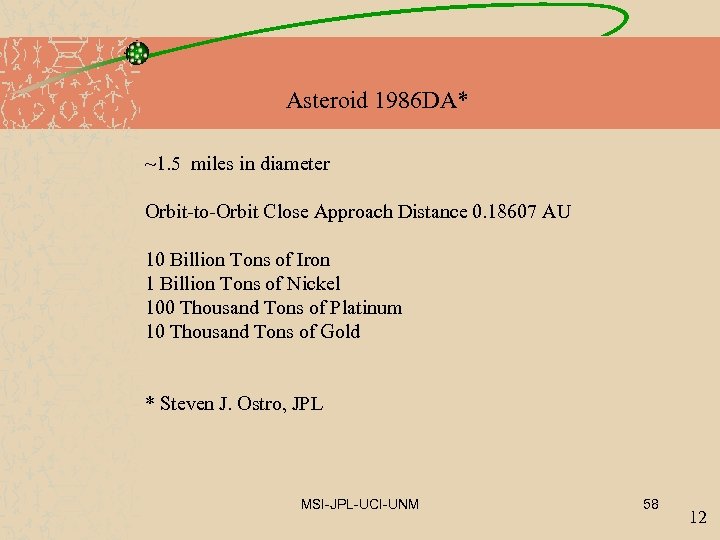

Asteroid 1986 DA* ~1. 5 miles in diameter Orbit-to-Orbit Close Approach Distance 0. 18607 AU 10 Billion Tons of Iron 1 Billion Tons of Nickel 100 Thousand Tons of Platinum 10 Thousand Tons of Gold * Steven J. Ostro, JPL MSI-JPL-UCI-UNM 58 12

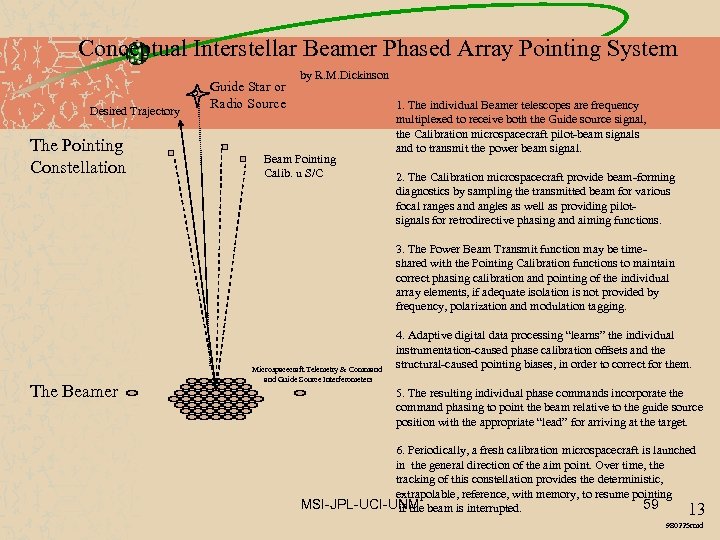

Conceptual Interstellar Beamer Phased Array Pointing System Desired Trajectory The Pointing Constellation Guide Star or Radio Source by R. M. Dickinson Beam Pointing Calib. u S/C 1. The individual Beamer telescopes are frequency multiplexed to receive both the Guide source signal, the Calibration microspacecraft pilot-beam signals and to transmit the power beam signal. 2. The Calibration microspacecraft provide beam-forming diagnostics by sampling the transmitted beam for various focal ranges and angles as well as providing pilotsignals for retrodirective phasing and aiming functions. 3. The Power Beam Transmit function may be timeshared with the Pointing Calibration functions to maintain correct phasing calibration and pointing of the individual array elements, if adequate isolation is not provided by frequency, polarization and modulation tagging. The Beamer Microspacecraft Telemetry & Command Guide Source Interferometers 4. Adaptive digital data processing “learns” the individual instrumentation-caused phase calibration offsets and the structural-caused pointing biases, in order to correct for them. 5. The resulting individual phase commands incorporate the command phasing to point the beam relative to the guide source position with the appropriate “lead” for arriving at the target. 6. Periodically, a fresh calibration microspacecraft is launched in the general direction of the aim point. Over time, the tracking of this constellation provides the deterministic, extrapolable, reference, with memory, to resume pointing MSI-JPL-UCI-UNM 59 if the beam is interrupted. 13 980225 rmd

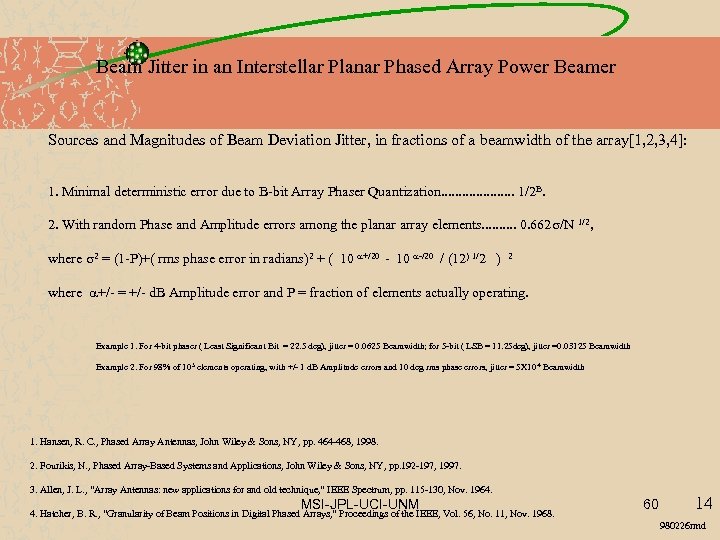

Beam Jitter in an Interstellar Planar Phased Array Power Beamer Sources and Magnitudes of Beam Deviation Jitter, in fractions of a beamwidth of the array[1, 2, 3, 4]: 1. Minimal deterministic error due to B-bit Array Phaser Quantization. . . . . 1/2 B. 2. With random Phase and Amplitude errors among the planar array elements. . 0. 662 s/N 1/2, where s 2 = (1 -P)+( rms phase error in radians)2 + ( 10 a+/20 - 10 a-/20 / (12) 1/2 ) 2 where a+/- = +/- d. B Amplitude error and P = fraction of elements actually operating. Example 1. For 4 -bit phaser ( Least Significant Bit = 22. 5 deg), jitter = 0. 0625 Beamwidth; for 5 -bit ( LSB = 11. 25 deg), jitter =0. 03125 Beamwidth Example 2. For 98% of 105 elements operating, with +/- 1 d. B Amplitude errors and 10 deg rms phase errors, jitter = 5 X 10 -4 Beamwidth 1. Hansen, R. C. , Phased Array Antennas, John Wiley & Sons, NY, pp. 464 -468, 1998. 2. Fourikis, N. , Phased Array-Based Systems and Applications, John Wiley & Sons, NY, pp. 192 -197, 1997. 3. Allen, J. L. , “Array Antennas: new applications for and old technique, ” IEEE Spectrum, pp. 115 -130, Nov. 1964. MSI-JPL-UCI-UNM 4. Hatcher, B. R. , “Granularity of Beam Positions in Digital Phased Arrays, ” Proceedings of the IEEE, Vol. 56, No. 11, Nov. 1968. 60 14 980226 rmd

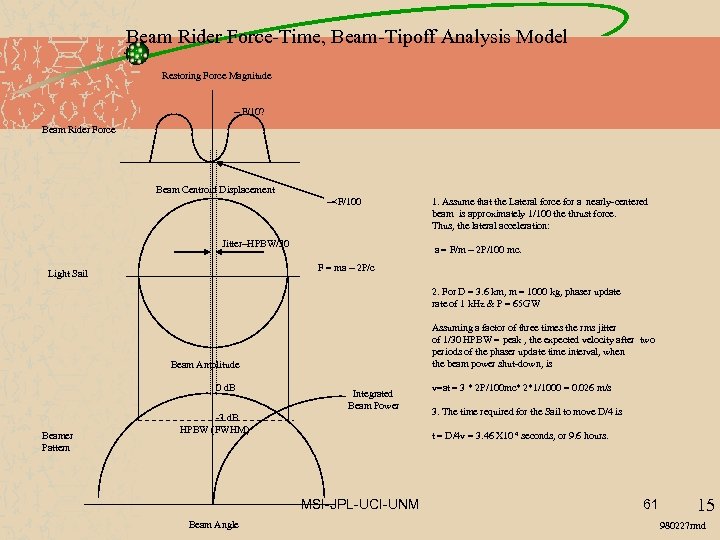

Beam Rider Force-Time, Beam-Tipoff Analysis Model Restoring Force Magnitude ~ F/10? Beam Rider Force Beam Centroid Displacement ~<F/100 Jitter~HPBW/30 1. Assume that the Lateral force for a nearly-centered beam is approximately 1/100 the thrust force. Thus, the lateral acceleration: a = F/m ~ 2 P/100 mc. F = ma ~ 2 P/c Light Sail 2. For D = 3. 6 km, m = 1000 kg, phaser update rate of 1 k. Hz & P = 65 GW Assuming a factor of three times the rms jitter of 1/30 HPBW = peak , the expected velocity after two periods of the phaser update time interval, when the beam power shut-down, is Beam Amplitude 0 d. B Beamer Pattern Integrated Beam Power -3 d. B HPBW (FWHM) 3. The time required for the Sail to move D/4 is t = D/4 v = 3. 46 X 10 4 seconds, or 9. 6 hours. MSI-JPL-UCI-UNM Beam Angle v=at = 3 * 2 P/100 mc* 2*1/1000 = 0. 026 m/s 61 15 980227 rmd

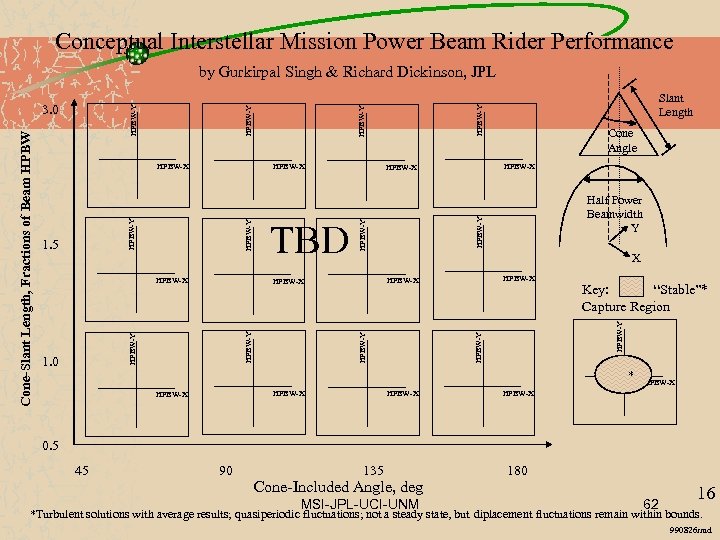

Conceptual Interstellar Mission Power Beam Rider Performance by Gurkirpal Singh & Richard Dickinson, JPL HPBW-X HPBW-Y Half Power Beamwidth Y X HPBW-Y Key: “Stable”* Capture Region HPBW-Y HPBW-X HPBW-Y 1. 0 Cone Angle HPBW-Y HPBW-X TBD Slant Length HPBW-X HPBW-Y 1. 5 HPBW-Y HPBW-X HPBW-Y Cone-Slant Length, Fractions of Beam HPBW 3. 0 * HPBW-X HPBW-X 0. 5 45 90 135 180 Cone-Included Angle, deg MSI-JPL-UCI-UNM 62 16 *Turbulent solutions with average results; quasiperiodic fluctuations; not a steady state, but diplacement fluctuations remain within bounds. 990826 rmd

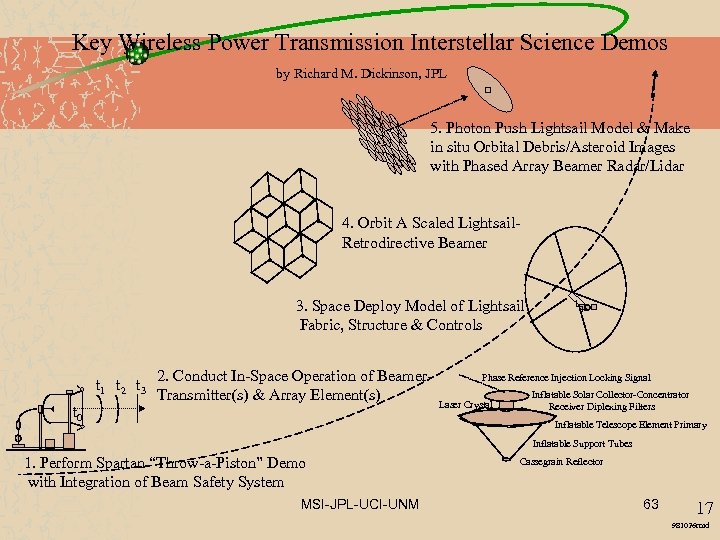

Key Wireless Power Transmission Interstellar Science Demos by Richard M. Dickinson, JPL 5. Photon Push Lightsail Model & Make in situ Orbital Debris/Asteroid Images with Phased Array Beamer Radar/Lidar 4. Orbit A Scaled Lightsail. Retrodirective Beamer 3. Space Deploy Model of Lightsail Fabric, Structure & Controls t 1 t 2 t 3 t 0 2. Conduct In-Space Operation of Beamer. Transmitter(s) & Array Element(s) Phase Reference Injection Locking Signal Laser Crystal Inflatable Solar Collector-Concentrator Receiver Diplexing Filters Inflatable Telescope Element Primary Inflatable Support Tubes 1. Perform Spartan “Throw-a-Piston” Demo with Integration of Beam Safety System MSI-JPL-UCI-UNM Cassegrain Reflector 63 17 981026 rmd

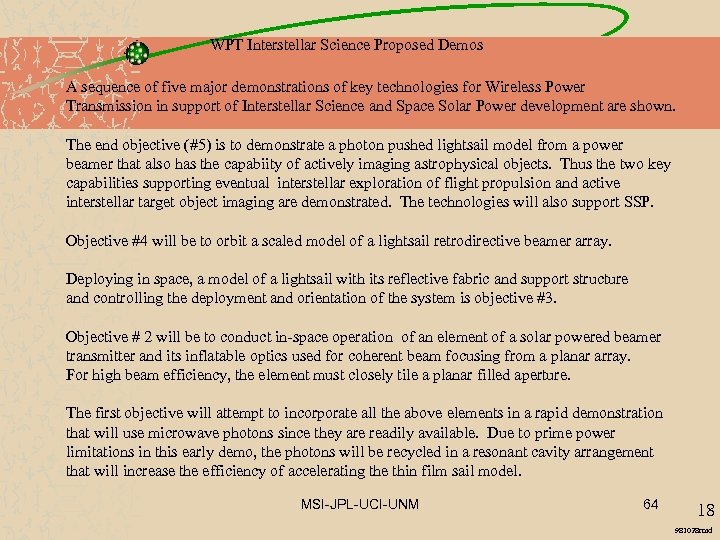

WPT Interstellar Science Proposed Demos A sequence of five major demonstrations of key technologies for Wireless Power Transmission in support of Interstellar Science and Space Solar Power development are shown. The end objective (#5) is to demonstrate a photon pushed lightsail model from a power beamer that also has the capabiity of actively imaging astrophysical objects. Thus the two key capabilities supporting eventual interstellar exploration of flight propulsion and active interstellar target object imaging are demonstrated. The technologies will also support SSP. Objective #4 will be to orbit a scaled model of a lightsail retrodirective beamer array. Deploying in space, a model of a lightsail with its reflective fabric and support structure and controlling the deployment and orientation of the system is objective #3. Objective # 2 will be to conduct in-space operation of an element of a solar powered beamer transmitter and its inflatable optics used for coherent beam focusing from a planar array. For high beam efficiency, the element must closely tile a planar filled aperture. The first objective will attempt to incorporate all the above elements in a rapid demonstration that will use microwave photons since they are readily available. Due to prime power limitations in this early demo, the photons will be recycled in a resonant cavity arrangement that will increase the efficiency of accelerating the thin film sail model. MSI-JPL-UCI-UNM 64 18 981028 rmd

86a48bfff92da0eaaccb9ca9a0f26e62.ppt