9a9fd7f910de904961dc7199f3425e0a.ppt

- Количество слайдов: 44

Specialty Training Perspective of the ABVS ® Dr. Beth Sabin, Assistant Director Education and Research Division

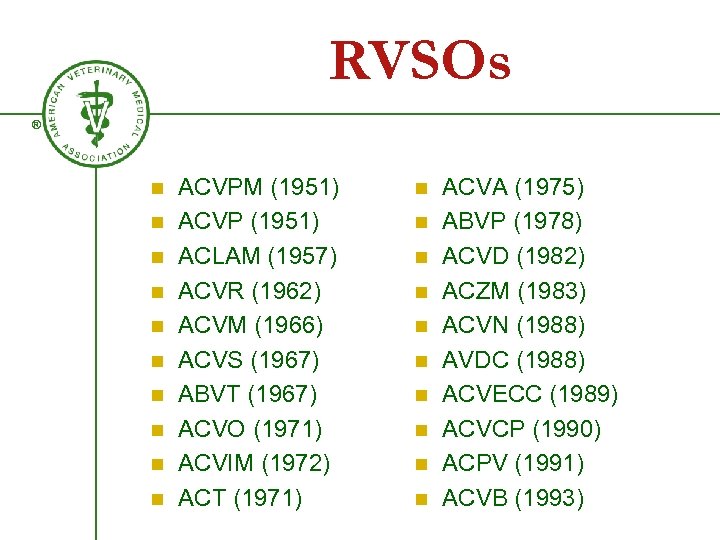

RVSOs ® n n n n n ACVPM (1951) ACVP (1951) ACLAM (1957) ACVR (1962) ACVM (1966) ACVS (1967) ABVT (1967) ACVO (1971) ACVIM (1972) ACT (1971) n n n n n ACVA (1975) ABVP (1978) ACVD (1982) ACZM (1983) ACVN (1988) AVDC (1988) ACVECC (1989) ACVCP (1990) ACPV (1991) ACVB (1993)

International Specialty Organizations ® n n ABVS encourages collaboration between RVSOs and veterinary specialty organizations elsewhere. ABVS would require detailed justification from RVSO before it will accept full reciprocity with an international specialty organization. Reciprocity is possible with specific portions of training programs. RVSO-approved training may be

Standard 9—Faculty ® n Academic positions must offer the security and benefits necessary to maintain stability, continuity, and competence of the faculty. Part-time faculty, residents, and graduate students may supplement the teaching efforts of the full-time permanent faculty if appropriately integrated into the instructional

COOPERATIVE ARRANGEMENTS FOR TRAINING SPECIALISTS Charles G. Mac. Allister Department of Veterinary Clinical Sciences Oklahoma State University Center for Veterinary Health Sciences

Summary AAVMC member institutions are providing 82% of the 2007 VIRMP residency positions. n These are our training positions. n We have the ability to influence who we train and what we train them for. n

“Grow Our Own” Program n Challenges – Identifying the trainee – Identifying a training site with current space for an additional resident – Making the match n Two faculty groups to approve resident – Home faculty approving faculty recruitment n Formal interview – Training school specialty group accepting the resident n Travel for interview

“Grow Our Own” Program n Negatives and Risks? – Costly ($140, 000/resident) – May not remain on faculty after contract period expires? – May not honor contract? – Others may attempt to buy out their contract? – May not become a successful faculty member – Junior/inexperienced faculty n Not yet board certified

Summary n Cooperative training agreements (in some form) have the potential to provide additional specialists for academic positions. n Could we offer select residencies with a requirement to provide 3 -years as a faculty member in an AAVMC member college? ?

The Scientific Component to Residency Training Kent Lloyd School of Veterinary Medicine, UC Davis Veterinary Teaching Hospitals and The Future of Clinical Veterinary Medical Education November 9 -11, 2006 ♦ Kansas City, MO

“…the Veterinary Teaching Hospitals are the fertile ground for growing veterinary academic faculty. ” (AAVMC, 2006)

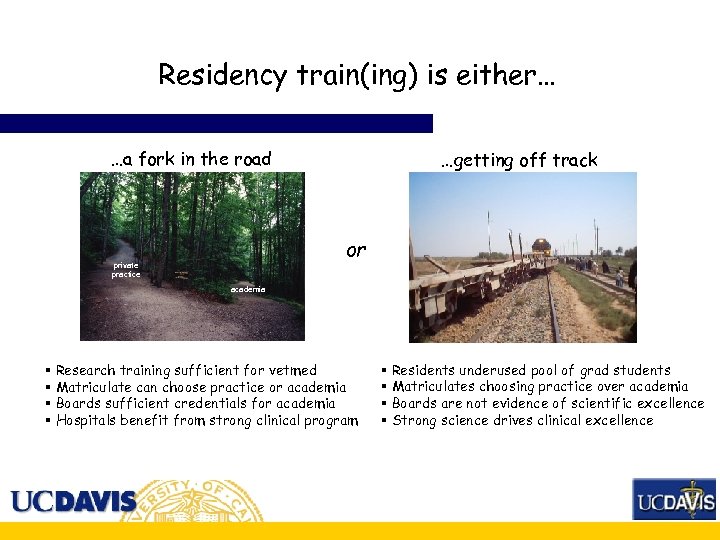

Residency train(ing) is either… …a fork in the road …getting off track or private practice academia § Research training sufficient for vetmed § Matriculate can choose practice or academia § Boards sufficient credentials for academia § Hospitals benefit from strong clinical program § Residents underused pool of grad students § Matriculates choosing practice over academia § Boards are not evidence of scientific excellence § Strong science drives clinical excellence

So, what are some possible solutions? § Reasonable and balanced allocation of clinical responsibilities § Coordinated and structured research time § Mentorship: clinical in the clinic; non-clinical in the laboratory § Select for and foster the academically-inclined clinical resident § Opportunities for alternative career choices

Example 1: Resident Research Program, Center for Companion Animal Health § Competitive awards program § Maximum funding of $4000 per award § Eligible for multiple awards during tenure § Research topics related to health problems of companion animals § 3 “calls” for research applications throughout the year § Review and notification approximately 2 mos after submission § Faculty mentor – resident mentee relationship key

Example 2: Equine Resident Research Funding Program, Center for Equine Health § One-time $4000 research “credit line” § Non-competitive; applications any time § Mentor can come from anywhere on campus § Reviewed by scientific advisors, feedback, advice… 2 mos § If approved, project completion expected within 12 -15 months § If unapproved, application can be revised (2 times) according to critique and resubmitted for reconsideration and funding

Example 3: Master of Preventive Veterinary Medicine (MPVM) degree § Component of specific residency programs: -Food Animal Reproduction and Herd Health -Dairy Production Medicine § One year coursework and capstone experience § Disease and production problems in animal populations § Degree awarded with residency certificate of completion

Example 4: Academic Residency - Board-certification and Ph. D § Equine medicine or surgery § Supported by The Gregson Fellowship § 5 years (3 y clinical, 2 y classes and lab) § Selection criteria include academic proclivities § Highly structured, coordinated, mentored § Reciprocal investment - Board Certification and Ph. D

Example 5: PRIME Program § The Primary Medical Education (PRIME) Program § Clinical research training during human clinical medicine residency § UCSF-VAMC: 2 year program of clinical and research training § Didactic lecture, journal clubs, work-in-progress sessions § Complements evidence based medicine approach to clinical training

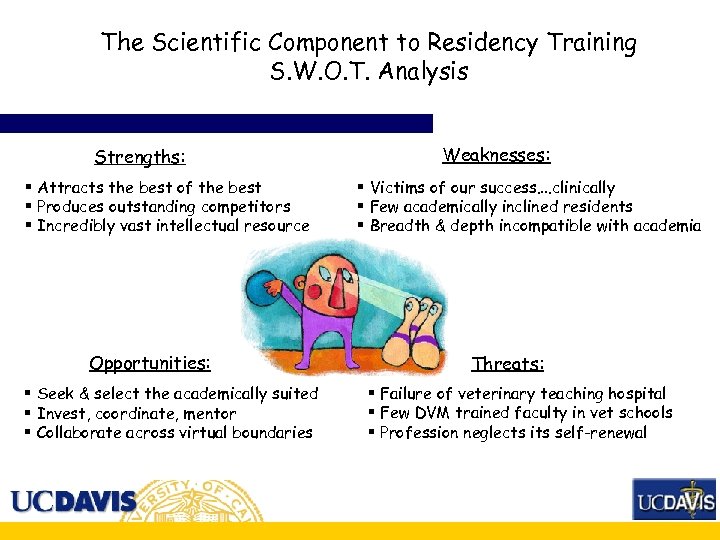

The Scientific Component to Residency Training S. W. O. T. Analysis Strengths: § Attracts the best of the best § Produces outstanding competitors § Incredibly vast intellectual resource Opportunities: § Seek & select the academically suited § Invest, coordinate, mentor § Collaborate across virtual boundaries Weaknesses: § Victims of our success…. clinically § Few academically inclined residents § Breadth & depth incompatible with academia Threats: § Failure of veterinary teaching hospital § Few DVM trained faculty in vet schools § Profession neglects its self-renewal

Private Specialty Practices and Veterinary Teaching Hospitals Partners in the 21 st Century Reuben Merideth, DVM, DACVO

21

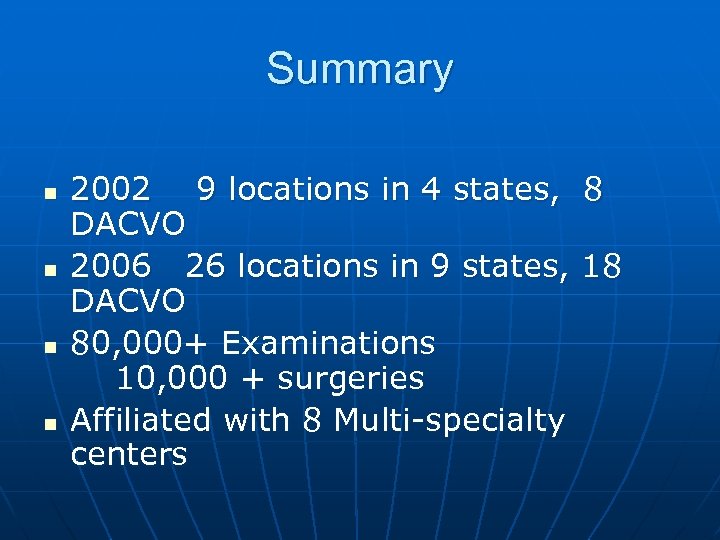

Summary n n 2002 9 locations in 4 states, 8 DACVO 2006 26 locations in 9 states, 18 DACVO 80, 000+ Examinations 10, 000 + surgeries Affiliated with 8 Multi-specialty centers

The World is Flat & ECFA n n n Diagnostic Images interpreted in Seattle Real time histopathology reviews from Canada Avian lecture from Germany Grand Rounds from 8 USA locations Centralized database

Cooperation Between Specialty Practices & VTHs

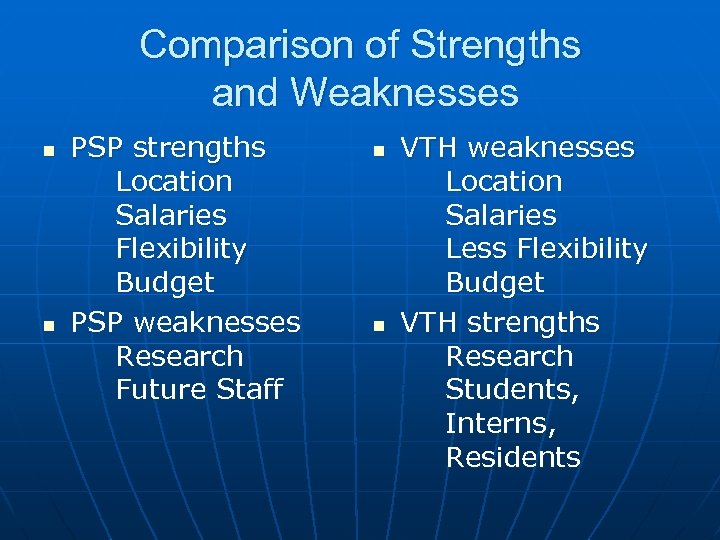

Comparison of Strengths and Weaknesses n n PSP strengths Location Salaries Flexibility Budget PSP weaknesses Research Future Staff n n VTH weaknesses Location Salaries Less Flexibility Budget VTH strengths Research Students, Interns, Residents

ECFA Cooperation with VTHs n n n n Teaching Veterinary Students Intern Rotations Resident Training Lecturing Histopathology Registries Cooperative Research Donations to VTHs

Meeting the Demand for Future Faculty Richard W. Valachovic, DMD, MPH Executive Director American Dental Education Association of American Veterinary Medical Colleges Symposium November 11, 2006 Kansas City, MO

Demographics of 2004 -05 U. S. Dental School Faculty Workforce* n n n 4, 736 full-time; 5, 097 part-time; and 1, 791 volunteer faculty members (status of 91 not reported) 74% male; 26% female 78% white/Caucasian; 11% Asian/Pacific Islander; 5% Hispanic/Latino; 4% black/African American; 2% other Mean and median age: 52 years Faculty 30 years or younger: 3% of total 31 -40 years: 18% 41 -50 years: 23% 51 -60 years: 31% Over 60 years: 25% *Source of all data is annual ADEA survey of the dental education workforce.

Faculty Separations Reasons varied by rank: n Most faculty who retired were full professors (37% of total) or associate professors (30%). n Those entering private practice were primarily at lower academic rank: assistant professors (52% of total) and instructors (33%).

The Problem Average Age of Dental School Faculty Assistant Professor: 47 Associate Professor: 55 Professor: 60 30% of current faculty are likely to retire over the next decade, creating over 3, 400 vacant positions. Key Factors « « Current vacancies unfilled “Graying” of current faculty Younger faculty departing for private practice Extremely small number of current students indicate interest in entering academia (around 1%)

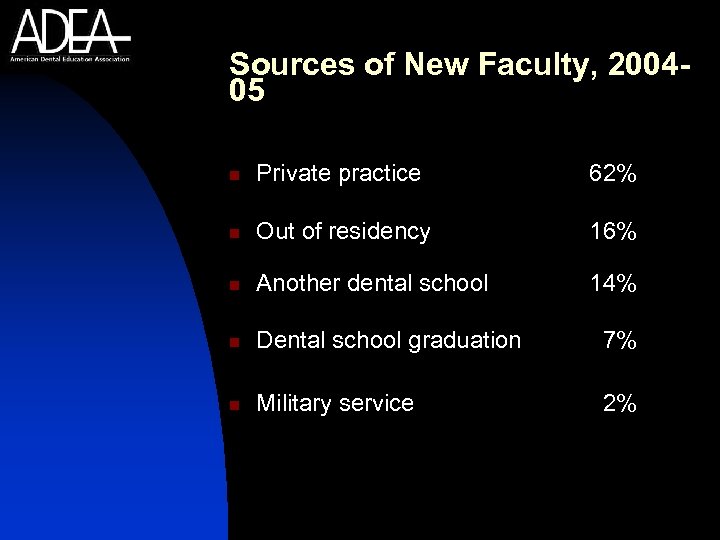

Sources of New Faculty, 200405 n Private practice 62% n Out of residency 16% n Another dental school 14% n Dental school graduation 7% n Military service 2%

ADEA’s Strategic Directions #1 is “recruitment, development, retention, and renewal of dental and allied dental faculty”

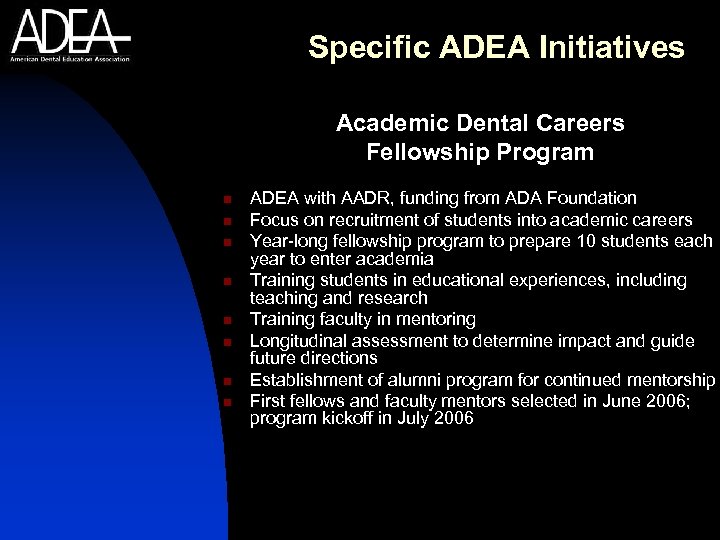

Specific ADEA Initiatives Academic Dental Careers Fellowship Program n n n n ADEA with AADR, funding from ADA Foundation Focus on recruitment of students into academic careers Year-long fellowship program to prepare 10 students each year to enter academia Training students in educational experiences, including teaching and research Training faculty in mentoring Longitudinal assessment to determine impact and guide future directions Establishment of alumni program for continued mentorship First fellows and faculty mentors selected in June 2006; program kickoff in July 2006

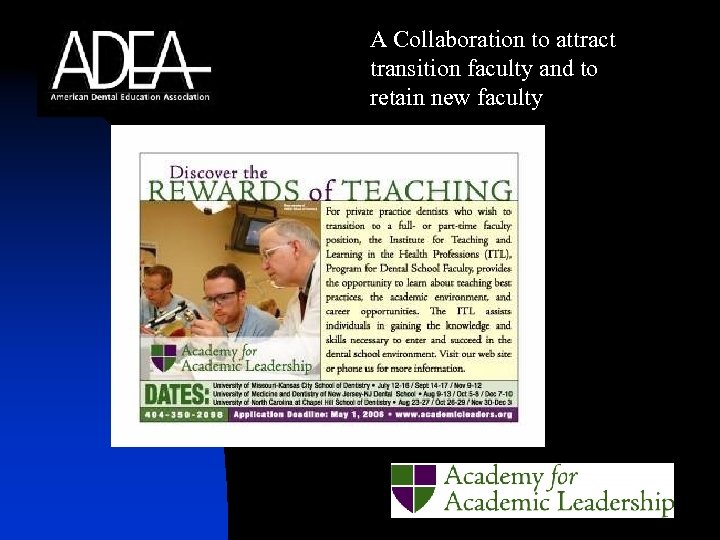

A Collaboration to attract transition faculty and to retain new faculty

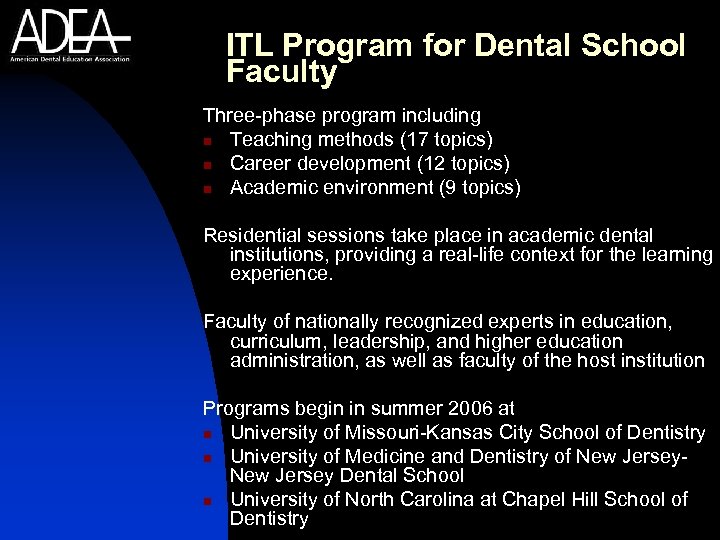

ITL Program for Dental School Faculty Three-phase program including n Teaching methods (17 topics) n Career development (12 topics) n Academic environment (9 topics) Residential sessions take place in academic dental institutions, providing a real-life context for the learning experience. Faculty of nationally recognized experts in education, curriculum, leadership, and higher education administration, as well as faculty of the host institution Programs begin in summer 2006 at n University of Missouri-Kansas City School of Dentistry n University of Medicine and Dentistry of New Jersey Dental School n University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill School of Dentistry

Making the Academy More Attractive to New Teacher-Scholars The Future of Clinical Veterinary Medical Education Association of American Veterinary Colleges November 11, 2006 Cathy A. Trower, Ph. D.

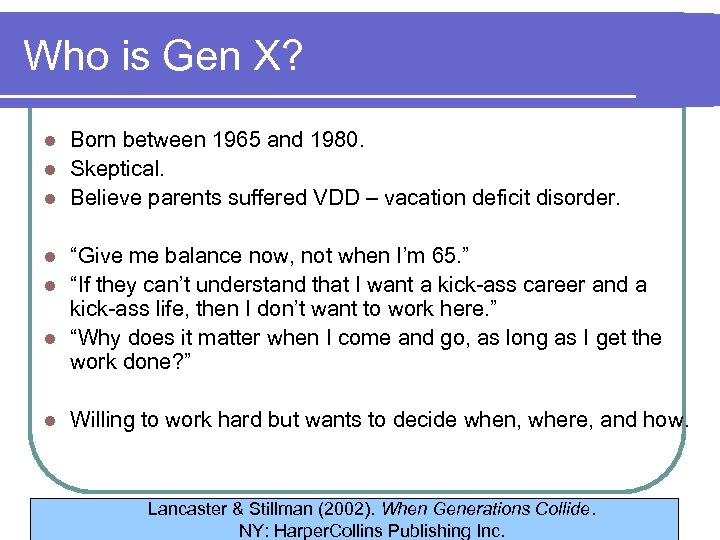

Who is Gen X? Born between 1965 and 1980. l Skeptical. l Believe parents suffered VDD – vacation deficit disorder. l “Give me balance now, not when I’m 65. ” l “If they can’t understand that I want a kick-ass career and a kick-ass life, then I don’t want to work here. ” l “Why does it matter when I come and go, as long as I get the work done? ” l l Willing to work hard but wants to decide when, where, and how. Lancaster & Stillman (2002). When Generations Collide. NY: Harper. Collins Publishing Inc.

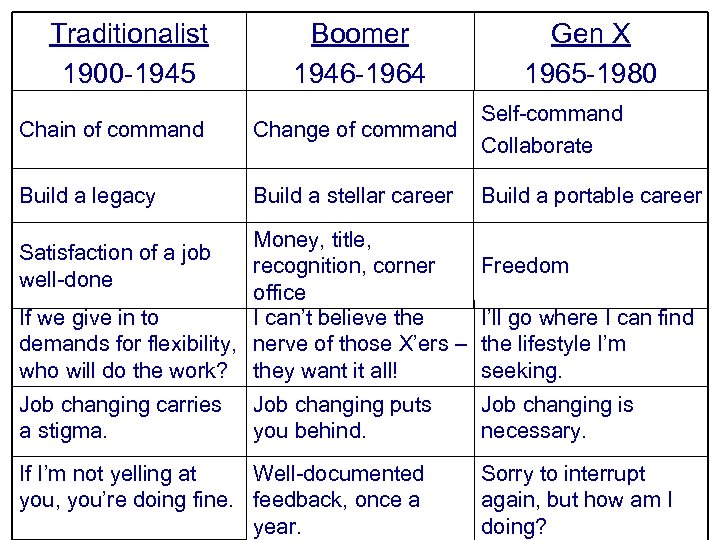

Traditionalist 1900 -1945 Boomer 1946 -1964 Gen X 1965 -1980 Chain of command Change of command Self-command Collaborate Build a legacy Build a stellar career Build a portable career Money, title, Satisfaction of a job recognition, corner well-done office If we give in to I can’t believe the demands for flexibility, nerve of those X’ers – who will do the work? they want it all! Job changing carries a stigma. Job changing puts you behind. If I’m not yelling at Well-documented you, you’re doing fine. feedback, once a year. Freedom I’ll go where I can find the lifestyle I’m seeking. Job changing is necessary. Sorry to interrupt again, but how am I doing?

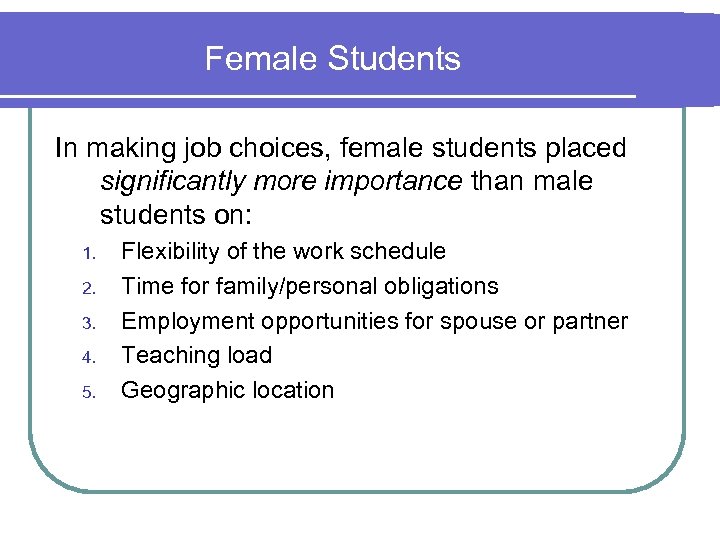

Female Students In making job choices, female students placed significantly more importance than male students on: 1. 2. 3. 4. 5. Flexibility of the work schedule Time for family/personal obligations Employment opportunities for spouse or partner Teaching load Geographic location

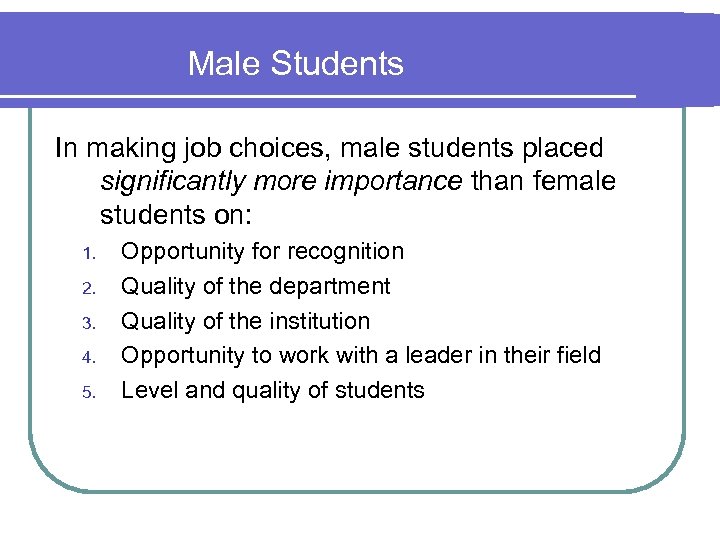

Male Students In making job choices, male students placed significantly more importance than female students on: 1. 2. 3. 4. 5. Opportunity for recognition Quality of the department Quality of the institution Opportunity to work with a leader in their field Level and quality of students

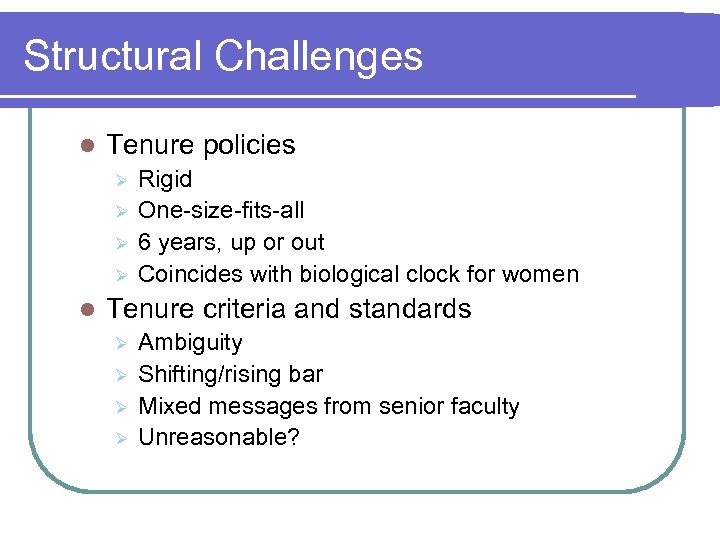

Structural Challenges l Tenure policies Ø Ø l Rigid One-size-fits-all 6 years, up or out Coincides with biological clock for women Tenure criteria and standards Ø Ø Ambiguity Shifting/rising bar Mixed messages from senior faculty Unreasonable?

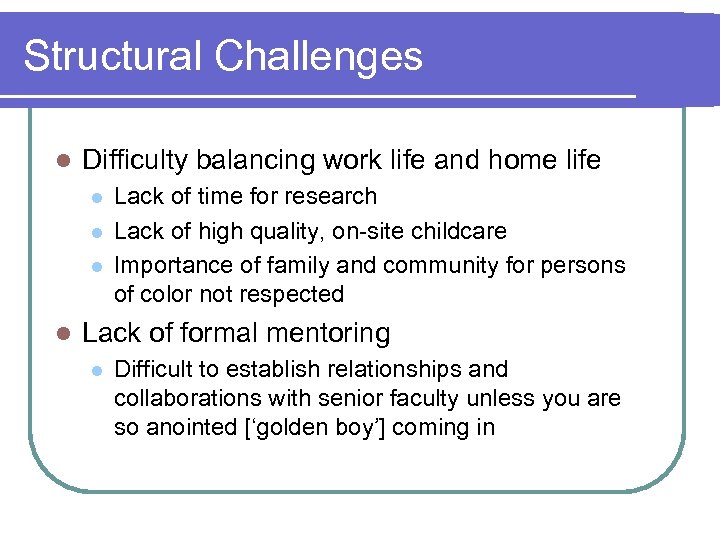

Structural Challenges l Difficulty balancing work life and home life l l Lack of time for research Lack of high quality, on-site childcare Importance of family and community for persons of color not respected Lack of formal mentoring l Difficult to establish relationships and collaborations with senior faculty unless you are so anointed [‘golden boy’] coming in

Deans, Chairs, and Senior Faculty Play a Pivotal Role in Culture Pay attention to… a. b. Current polices and practices Academic culture Revise policies & practices a. b. c. d. e. f. g. h. “Life-friendly” Clarity Transparency Flexibility Equity Mentoring Collaboration Leave/research time/’protection’ from service

If Harvard Can, You Can “It is time for the university…to realize that facilitating faculty efforts to achieve work-life balance does not just require providing better access to childcare, leave, and tenure-clock policies…. It requires a willingness to reconsider the way that we do business on a day-to-day basis, and to recognize that practices that evolved when… faculty were available on a round-the-clock basis…are having a counterproductive impact today. ” – Lisa Martin, Senior Advisor to the A&S Dean on Diversity Issues R. Wilson, The Chronicle of Higher Education, 11/3/06, p. A 10

9a9fd7f910de904961dc7199f3425e0a.ppt