03f2703be7538a5674043f9dc93100e3.ppt

- Количество слайдов: 143

Special Topics in Old , Middle and Modern English Literature or From Beowulf to Faustus Summer term 2015/2016

Special Topics in Old , Middle and Modern English Literature or From Beowulf to Faustus Summer term 2015/2016

Lecture no. 1: Main Periods of English Literature • Old-English Period: 650 – 1150 • Middle-English Period: 1150 – 1500 • Modern-English Period: 1500 – up to now. . . but

Lecture no. 1: Main Periods of English Literature • Old-English Period: 650 – 1150 • Middle-English Period: 1150 – 1500 • Modern-English Period: 1500 – up to now. . . but

What is English literature? • literature written in English • i. e. “English” of “English literature” refers not to a nation but to a language (see Burgess, 1974, p. 9). • the literature produced in the British Isles, because the ‘international’ concept of English Literature “belongs to the present and the future, and our main concern is with the past. ” (ibid. )

What is English literature? • literature written in English • i. e. “English” of “English literature” refers not to a nation but to a language (see Burgess, 1974, p. 9). • the literature produced in the British Isles, because the ‘international’ concept of English Literature “belongs to the present and the future, and our main concern is with the past. ” (ibid. )

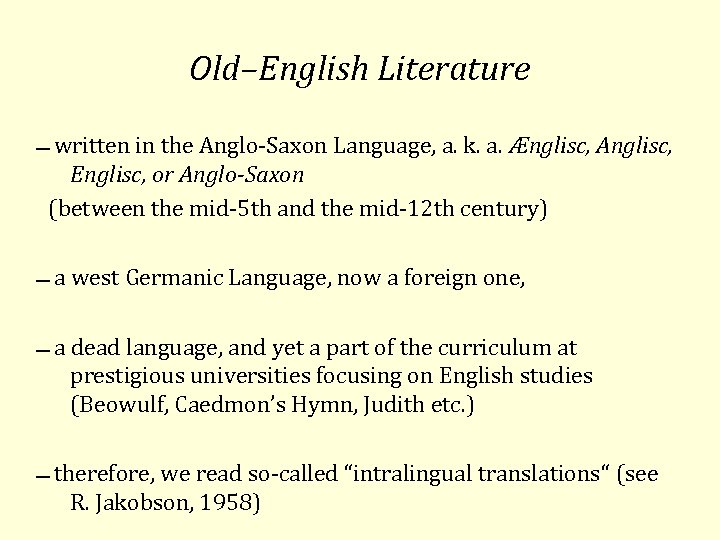

Old–English Literature written in the Anglo Saxon Language, a. k. a. Ænglisc, Anglisc, Englisc, or Anglo-Saxon (between the mid 5 th and the mid 12 th century) a west Germanic Language, now a foreign one, a dead language, and yet a part of the curriculum at prestigious universities focusing on English studies (Beowulf, Caedmon’s Hymn, Judith etc. ) therefore, we read so called “intralingual translations“ (see R. Jakobson, 1958)

Old–English Literature written in the Anglo Saxon Language, a. k. a. Ænglisc, Anglisc, Englisc, or Anglo-Saxon (between the mid 5 th and the mid 12 th century) a west Germanic Language, now a foreign one, a dead language, and yet a part of the curriculum at prestigious universities focusing on English studies (Beowulf, Caedmon’s Hymn, Judith etc. ) therefore, we read so called “intralingual translations“ (see R. Jakobson, 1958)

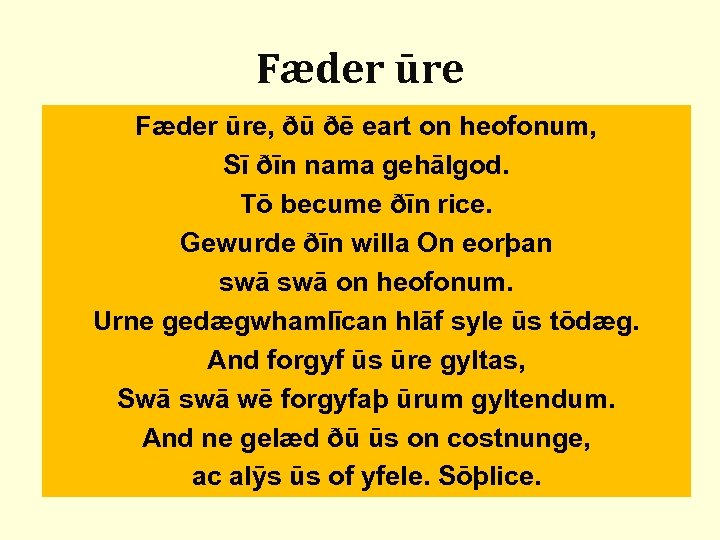

Fæder ūre, ðū ðē eart on heofonum, Sī ðīn nama gehālgod. Tō becume ðīn rice. Gewurde ðīn willa On eorþan swā on heofonum. Urne gedægwhamlīcan hlāf syle ūs tōdæg. And forgyf ūs ūre gyltas, Swā swā wē forgyfaþ ūrum gyltendum. And ne gelæd ðū ūs on costnunge, ac alȳs ūs of yfele. Sōþlice.

Fæder ūre, ðū ðē eart on heofonum, Sī ðīn nama gehālgod. Tō becume ðīn rice. Gewurde ðīn willa On eorþan swā on heofonum. Urne gedægwhamlīcan hlāf syle ūs tōdæg. And forgyf ūs ūre gyltas, Swā swā wē forgyfaþ ūrum gyltendum. And ne gelæd ðū ūs on costnunge, ac alȳs ūs of yfele. Sōþlice.

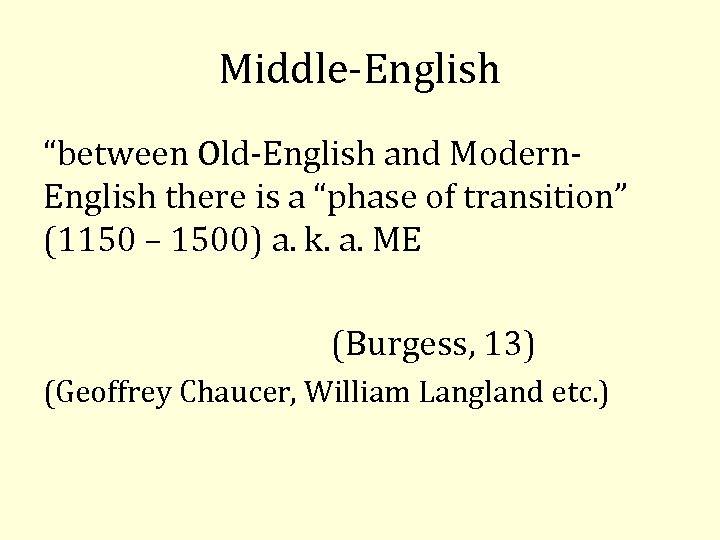

Middle English “between Old English and Modern English there is a “phase of transition” (1150 – 1500) a. k. a. ME (Burgess, 13) (Geoffrey Chaucer, William Langland etc. )

Middle English “between Old English and Modern English there is a “phase of transition” (1150 – 1500) a. k. a. ME (Burgess, 13) (Geoffrey Chaucer, William Langland etc. )

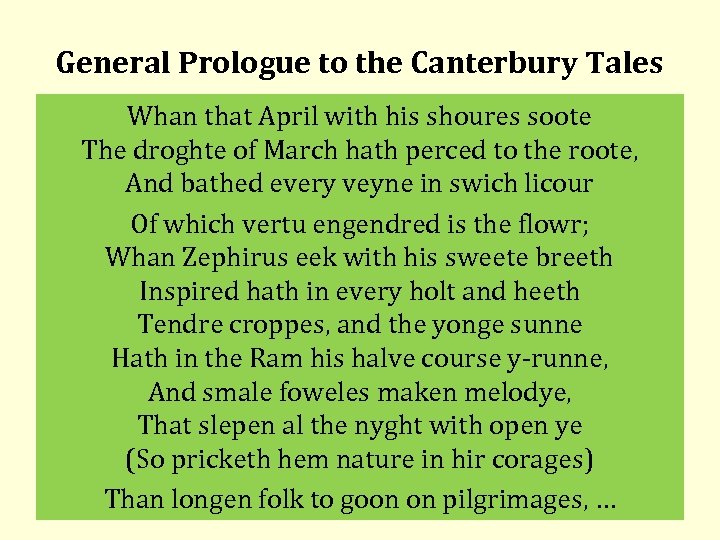

General Prologue to the Canterbury Tales Whan that April with his shoures soote The droghte of March hath perced to the roote, And bathed every veyne in swich licour Of which vertu engendred is the flowr; Whan Zephirus eek with his sweete breeth Inspired hath in every holt and heeth Tendre croppes, and the yonge sunne Hath in the Ram his halve course y runne, And smale foweles maken melodye, That slepen al the nyght with open ye (So pricketh hem nature in hir corages) Than longen folk to goon on pilgrimages, …

General Prologue to the Canterbury Tales Whan that April with his shoures soote The droghte of March hath perced to the roote, And bathed every veyne in swich licour Of which vertu engendred is the flowr; Whan Zephirus eek with his sweete breeth Inspired hath in every holt and heeth Tendre croppes, and the yonge sunne Hath in the Ram his halve course y runne, And smale foweles maken melodye, That slepen al the nyght with open ye (So pricketh hem nature in hir corages) Than longen folk to goon on pilgrimages, …

Phase of transition • the phase when Middle English was spoken (i. e. between the Norman invasion of 1066 and about 1470, when the Chancery Standard, a form of London based English, • a specific period because many, if not all, dialects had their own literatures (and spellings).

Phase of transition • the phase when Middle English was spoken (i. e. between the Norman invasion of 1066 and about 1470, when the Chancery Standard, a form of London based English, • a specific period because many, if not all, dialects had their own literatures (and spellings).

Modern-English Period from 1500 (only relatively modern) From The Tragic History of the Life and Death of Doctor Faustus Settle thy studies, Faustus, and begin To sound the depth of that thou wilt profess: Having commenc'd, be a divine in shew, Yet level at the end of every art, And live and die in Aristotle's works. Sweet Analytics, 'tis thou hast ravish'd me! Bene disserere est finis logices. Is, to dispute well, logic's chiefest end? Affords this art no greater miracle? Then read no more; thou hast attain'd that end: A greater subject fitteth Faustus' wit: …

Modern-English Period from 1500 (only relatively modern) From The Tragic History of the Life and Death of Doctor Faustus Settle thy studies, Faustus, and begin To sound the depth of that thou wilt profess: Having commenc'd, be a divine in shew, Yet level at the end of every art, And live and die in Aristotle's works. Sweet Analytics, 'tis thou hast ravish'd me! Bene disserere est finis logices. Is, to dispute well, logic's chiefest end? Affords this art no greater miracle? Then read no more; thou hast attain'd that end: A greater subject fitteth Faustus' wit: …

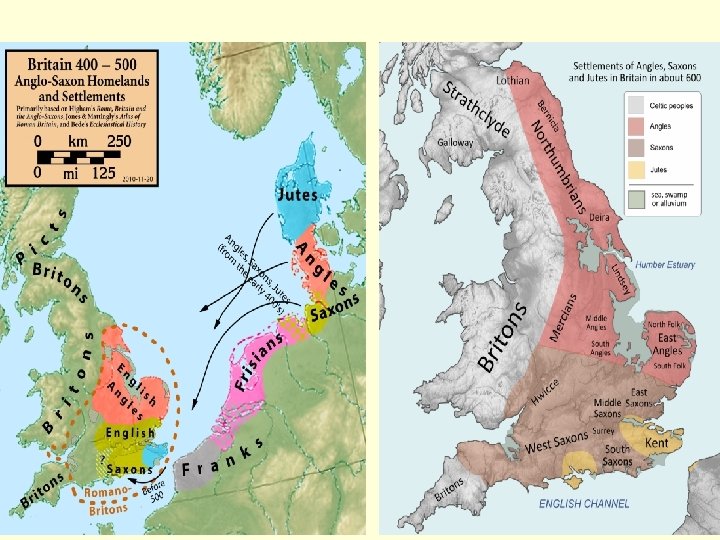

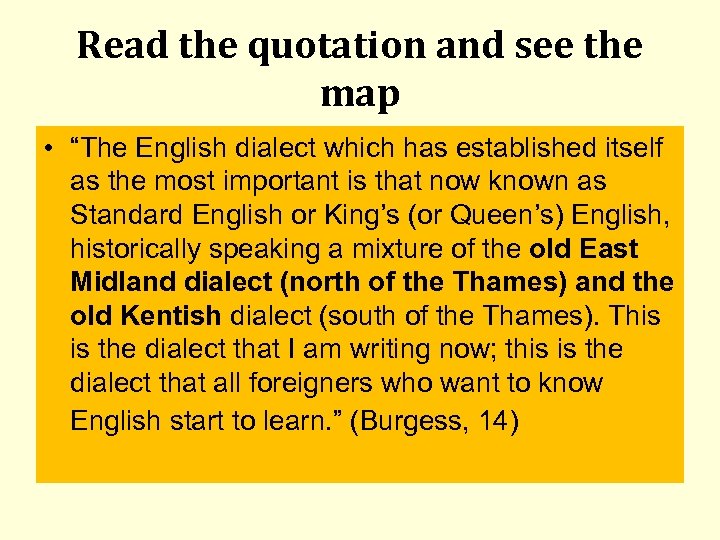

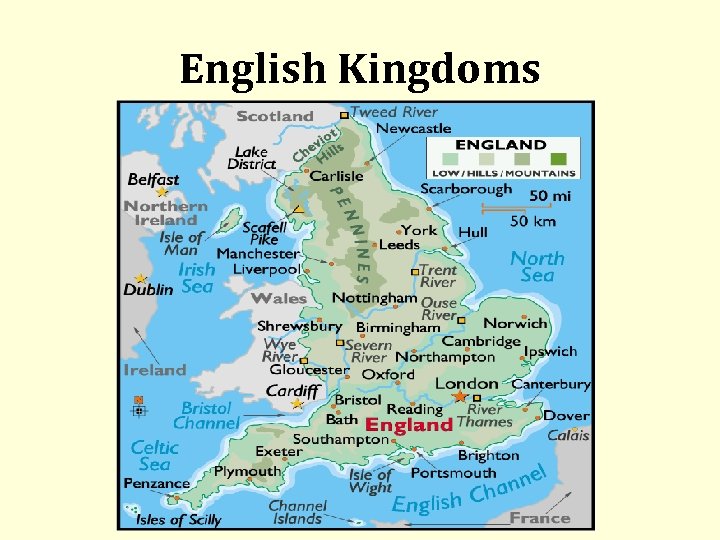

Read the quotation and see the map • “The English dialect which has established itself as the most important is that now known as Standard English or King’s (or Queen’s) English, historically speaking a mixture of the old East Midland dialect (north of the Thames) and the old Kentish dialect (south of the Thames). This is the dialect that I am writing now; this is the dialect that all foreigners who want to know English start to learn. ” (Burgess, 14)

Read the quotation and see the map • “The English dialect which has established itself as the most important is that now known as Standard English or King’s (or Queen’s) English, historically speaking a mixture of the old East Midland dialect (north of the Thames) and the old Kentish dialect (south of the Thames). This is the dialect that I am writing now; this is the dialect that all foreigners who want to know English start to learn. ” (Burgess, 14)

English Kingdoms

English Kingdoms

Geoffrey Chaucer’s language • English of London (more or less the same area) and for the English people it is relatively easy to understand since the dialect became Modern English spoken today. Other dialects remain less understandable.

Geoffrey Chaucer’s language • English of London (more or less the same area) and for the English people it is relatively easy to understand since the dialect became Modern English spoken today. Other dialects remain less understandable.

1 st. seminar – the documentary The Adventures of English 1. DVD – 1. episode (at least up to the 23 rd min. ) + instructions where to find the materials to read

1 st. seminar – the documentary The Adventures of English 1. DVD – 1. episode (at least up to the 23 rd min. ) + instructions where to find the materials to read

Lecture no. 2 Historical background , the first Englishmen, the first traces of literature foreigners coming from the Continent. . . invaded the territory called ‘Brittania’ (Romans who called the prehistoric inhabitants ‘Britanni’, in English we call them Britons). Britain – the most westerly and northerly province of the Roman Empire. when Romans left, “dark ages” set in (fascinating scholars and writers alike) 449 AD – Anglo Saxon invasion starts

Lecture no. 2 Historical background , the first Englishmen, the first traces of literature foreigners coming from the Continent. . . invaded the territory called ‘Brittania’ (Romans who called the prehistoric inhabitants ‘Britanni’, in English we call them Britons). Britain – the most westerly and northerly province of the Roman Empire. when Romans left, “dark ages” set in (fascinating scholars and writers alike) 449 AD – Anglo Saxon invasion starts

Britons vs. Anglo-Saxons Britons: descendants still live in Wales, the word “Welsh” comes from Old English (“a foreigner” or ”slave”) A S’s: barbarians, i. e. not Christians. They worshipped their own Germanic gods. Christianity had been well established in Ireland evangelists soon converted the Anglo Saxons.

Britons vs. Anglo-Saxons Britons: descendants still live in Wales, the word “Welsh” comes from Old English (“a foreigner” or ”slave”) A S’s: barbarians, i. e. not Christians. They worshipped their own Germanic gods. Christianity had been well established in Ireland evangelists soon converted the Anglo Saxons.

First traces of literature prose usually concerned theology, biographies, historical documents, letters. . . Their authors predominantly found in the circles of clergy (e. g. Bede, Ælfric the Grammarian, Ceadmon, Cynewulf) oral poetry tradition was very rich, the authors usually unknown – poems were passed, learnt and recited, authors forgotten

First traces of literature prose usually concerned theology, biographies, historical documents, letters. . . Their authors predominantly found in the circles of clergy (e. g. Bede, Ælfric the Grammarian, Ceadmon, Cynewulf) oral poetry tradition was very rich, the authors usually unknown – poems were passed, learnt and recited, authors forgotten

Beowulf – origins • the oldest English epic poem (Burgess), • (likely) brought to England by the Anglo Saxons from the Continent, • original (still extant) manuscript dates back to (cca. ) 1000 A. D. , • According to Abrams’ The Norton Anthology of English Literature, the epic was written down during the first half of the 8 th century (the Oxford professor A. Orchard is of the same opinion) • (btw – a related work Liber Mostrorum by Aldhelm (639 – 709) – written in Latin (King Hygelac of the Gaets mentioned, this time as a monster)

Beowulf – origins • the oldest English epic poem (Burgess), • (likely) brought to England by the Anglo Saxons from the Continent, • original (still extant) manuscript dates back to (cca. ) 1000 A. D. , • According to Abrams’ The Norton Anthology of English Literature, the epic was written down during the first half of the 8 th century (the Oxford professor A. Orchard is of the same opinion) • (btw – a related work Liber Mostrorum by Aldhelm (639 – 709) – written in Latin (King Hygelac of the Gaets mentioned, this time as a monster)

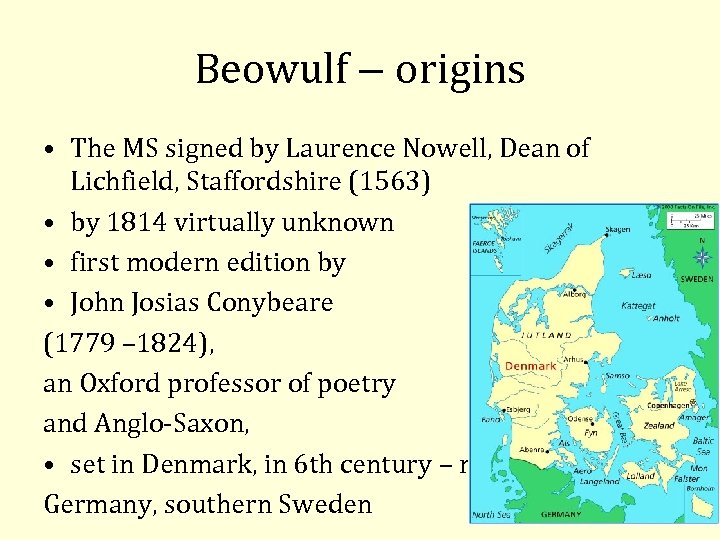

Beowulf – origins • The MS signed by Laurence Nowell, Dean of Lichfield, Staffordshire (1563) • by 1814 virtually unknown • first modern edition by • John Josias Conybeare (1779 – 1824), an Oxford professor of poetry and Anglo Saxon, • set in Denmark, in 6 th century – northern Germany, southern Sweden

Beowulf – origins • The MS signed by Laurence Nowell, Dean of Lichfield, Staffordshire (1563) • by 1814 virtually unknown • first modern edition by • John Josias Conybeare (1779 – 1824), an Oxford professor of poetry and Anglo Saxon, • set in Denmark, in 6 th century – northern Germany, southern Sweden

Beowulf • a warrior epic, a poem of more than three thousand lines (31861) • in a West-Saxon dialect • Some lines lost or damaged, modern scholars had to infer details • Sir Robert Bruce Cotton’s (1571 1631) collection damaged by a fire in 1731 – now exists in many Modern English translations, e. g. Donaldson, Childe, Tolkien (in prose + The Sellic Spell + Lay of Beowulf), Kennedy, Heaney, (in verse) [1] according to: Baštín, Š. , Olexa, J. , Studená, Z. , Dejiny anglickej a americkej literatúry, yet in Heaney’s translation we find 318 2

Beowulf • a warrior epic, a poem of more than three thousand lines (31861) • in a West-Saxon dialect • Some lines lost or damaged, modern scholars had to infer details • Sir Robert Bruce Cotton’s (1571 1631) collection damaged by a fire in 1731 – now exists in many Modern English translations, e. g. Donaldson, Childe, Tolkien (in prose + The Sellic Spell + Lay of Beowulf), Kennedy, Heaney, (in verse) [1] according to: Baštín, Š. , Olexa, J. , Studená, Z. , Dejiny anglickej a americkej literatúry, yet in Heaney’s translation we find 318 2

Beowulf – the plot • The banqueting hall. “mead hall” of King Hrothgar is raided and the king’s warriors are devoured by Grendel – half devil, half man. • Beowulf comes from Sweden to help the king and fights Grendel, and his mother, later a dragon • One fact of history – King of the Geats, Hygelac, perpetuates a raid on the Franks (the raid occurred 520)

Beowulf – the plot • The banqueting hall. “mead hall” of King Hrothgar is raided and the king’s warriors are devoured by Grendel – half devil, half man. • Beowulf comes from Sweden to help the king and fights Grendel, and his mother, later a dragon • One fact of history – King of the Geats, Hygelac, perpetuates a raid on the Franks (the raid occurred 520)

Beowulf – debate – written in a sophisticated style by a Christian poet, yet the poem poses a token of the heathen Anglo Saxon heritage (Burgess) – historical passages, sort of “magical realism” “It is not a Christian poem – despite the Christian flavour given to it by the monastery scribe (e. g. Grendel is of the accursed race of the first murderer, Cain) – but the product of an advanced pagan civilization. ” (Burgess, 18)

Beowulf – debate – written in a sophisticated style by a Christian poet, yet the poem poses a token of the heathen Anglo Saxon heritage (Burgess) – historical passages, sort of “magical realism” “It is not a Christian poem – despite the Christian flavour given to it by the monastery scribe (e. g. Grendel is of the accursed race of the first murderer, Cain) – but the product of an advanced pagan civilization. ” (Burgess, 18)

Beowulf – debate According to prof. A. Orchard: – a real Christian poem referring back to pagan history, – the days of old are gone and doomed – the monsters found in it can be seen as symbols of lethal paganism, – the Danes (Vikings) are doomed one way or the other.

Beowulf – debate According to prof. A. Orchard: – a real Christian poem referring back to pagan history, – the days of old are gone and doomed – the monsters found in it can be seen as symbols of lethal paganism, – the Danes (Vikings) are doomed one way or the other.

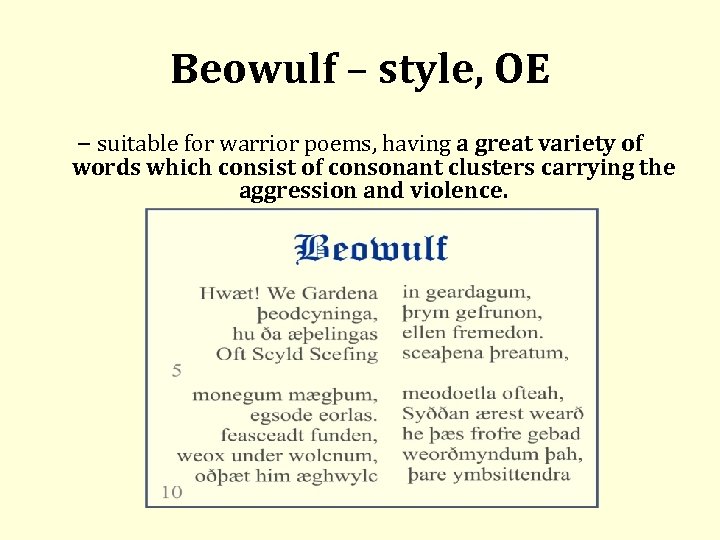

Beowulf – style, OE – suitable for warrior poems, having a great variety of words which consist of consonant clusters carrying the aggression and violence.

Beowulf – style, OE – suitable for warrior poems, having a great variety of words which consist of consonant clusters carrying the aggression and violence.

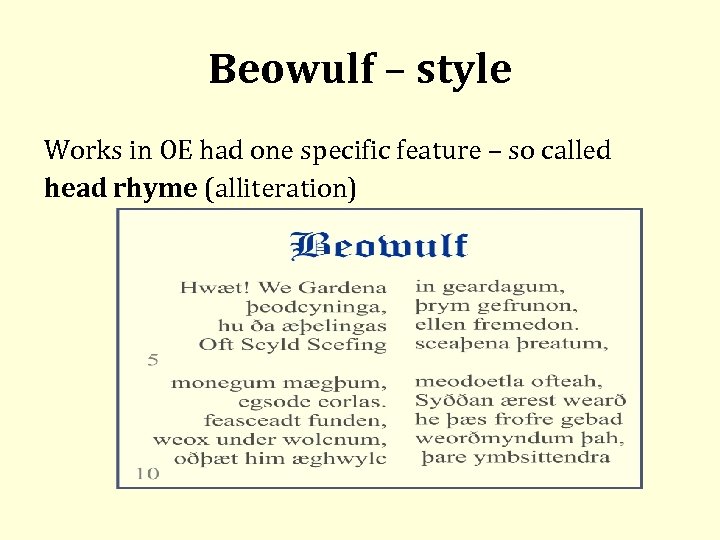

Beowulf – style Works in OE had one specific feature – so called head rhyme (alliteration)

Beowulf – style Works in OE had one specific feature – so called head rhyme (alliteration)

And the result? Compounds, aka kennings • it was difficult to find words beginning with the same letters, so there was a tendency to link existing words and creating compounded neologisms For example – rod fasten – “to fix to a tree”, – later substituted by “crucify” which came into existence in English later – bone house (body), joy wood (harp), battle play (fight or war), shadow walker (? – a hapax legomenon)

And the result? Compounds, aka kennings • it was difficult to find words beginning with the same letters, so there was a tendency to link existing words and creating compounded neologisms For example – rod fasten – “to fix to a tree”, – later substituted by “crucify” which came into existence in English later – bone house (body), joy wood (harp), battle play (fight or war), shadow walker (? – a hapax legomenon)

Watch and listen to: In Our Time – Beowulf hosted by Melvyn Bragg http: //www. bbc. co. uk/programmes/b 0542 xt 7 In search of Beowulf (a documentary), presented by Michael Wood https: //www. youtube. com/watch? v=1 C 0 s. FXU 0 SLo

Watch and listen to: In Our Time – Beowulf hosted by Melvyn Bragg http: //www. bbc. co. uk/programmes/b 0542 xt 7 In search of Beowulf (a documentary), presented by Michael Wood https: //www. youtube. com/watch? v=1 C 0 s. FXU 0 SLo

Lecture no. 3 Earliest Old-English Texts Many of them preserved in the 10 th century West Saxon manuscripts (aka codices): 1. Cotton Manuscript (also known as the Beowulf Manuscript or the Nowell manuscript, incl. Beowulf, Judith, The Battle of Maldon etc. ) – from a great collection of medieval manuscripts made by Sir Robert Bruce Cotton (1571 – 1631) – now stored in the British Museum

Lecture no. 3 Earliest Old-English Texts Many of them preserved in the 10 th century West Saxon manuscripts (aka codices): 1. Cotton Manuscript (also known as the Beowulf Manuscript or the Nowell manuscript, incl. Beowulf, Judith, The Battle of Maldon etc. ) – from a great collection of medieval manuscripts made by Sir Robert Bruce Cotton (1571 – 1631) – now stored in the British Museum

Earliest Old-English Texts 2. The Exeter Book (ca. 960 – 970) – donated to the Exeter Cathedral by bishop Leofric in 1072, a note (Leofric’s? ) reads: “A large English book about many things written in verse. ” (Treharne, p. 35) incl. poems like Christ, Juliana, Guthlac, Phoenix, elegies like The Wanderer, The Seafarer, The Wife’s Lamen, over 30 poetic texts and 90 riddles. The texts have no titles, the current titles have been provided by editors.

Earliest Old-English Texts 2. The Exeter Book (ca. 960 – 970) – donated to the Exeter Cathedral by bishop Leofric in 1072, a note (Leofric’s? ) reads: “A large English book about many things written in verse. ” (Treharne, p. 35) incl. poems like Christ, Juliana, Guthlac, Phoenix, elegies like The Wanderer, The Seafarer, The Wife’s Lamen, over 30 poetic texts and 90 riddles. The texts have no titles, the current titles have been provided by editors.

Earliest Old-English Texts 3. Junius Manuscript – named after the Dutch collector Franciscus Junius (1591 – 1677), a pioneer of Germanic philology, in 1655 he published the contents, – Junius thought the poems were written down by Caedmon, now debated, hence the popular name the Caedmon manuscript. incl. religious poems – paraphrases of some Biblical texts like Genesis, Exodus and Daniel etc. Exodus: one of the most difficult A S texts, too many hapax legomena.

Earliest Old-English Texts 3. Junius Manuscript – named after the Dutch collector Franciscus Junius (1591 – 1677), a pioneer of Germanic philology, in 1655 he published the contents, – Junius thought the poems were written down by Caedmon, now debated, hence the popular name the Caedmon manuscript. incl. religious poems – paraphrases of some Biblical texts like Genesis, Exodus and Daniel etc. Exodus: one of the most difficult A S texts, too many hapax legomena.

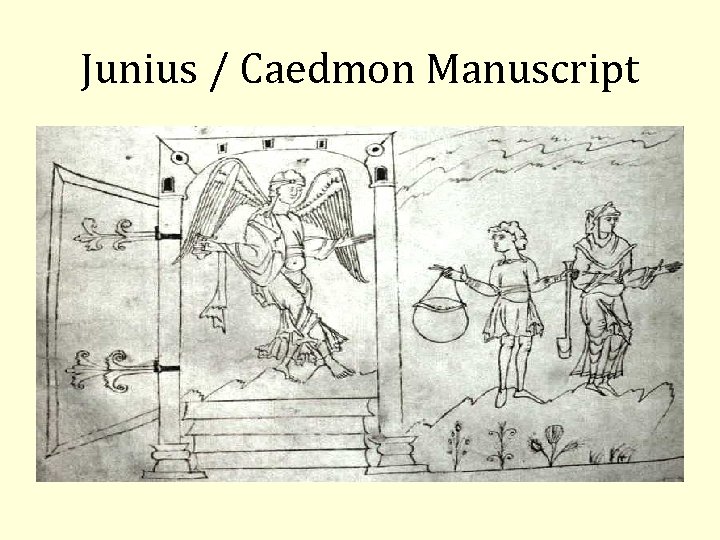

Junius / Caedmon Manuscript

Junius / Caedmon Manuscript

Earliest Old-English Texts 4. The Vercelli Book – housed in the Vercelli Library, north western Italy (housed there since the 12 th century) – in the 19 th century discovered by a German Friedrich Blume while he was looking for legal manuscripts, – consists of 23 prose texts and six poems, incl. Elene, The Fates of the Apostles, Andreas, The Dream of the Rood

Earliest Old-English Texts 4. The Vercelli Book – housed in the Vercelli Library, north western Italy (housed there since the 12 th century) – in the 19 th century discovered by a German Friedrich Blume while he was looking for legal manuscripts, – consists of 23 prose texts and six poems, incl. Elene, The Fates of the Apostles, Andreas, The Dream of the Rood

The Dream of the Rood

The Dream of the Rood

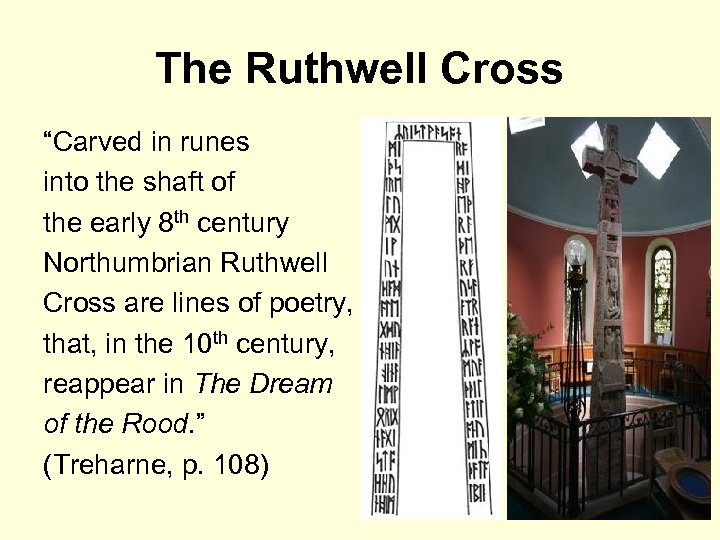

The Ruthwell Cross “Carved in runes into the shaft of the early 8 th century Northumbrian Ruthwell Cross are lines of poetry, that, in the 10 th century, reappear in The Dream of the Rood. ” (Treharne, p. 108)

The Ruthwell Cross “Carved in runes into the shaft of the early 8 th century Northumbrian Ruthwell Cross are lines of poetry, that, in the 10 th century, reappear in The Dream of the Rood. ” (Treharne, p. 108)

Caedmon († in ca 680) (/ˈkædmən/ or /ˈkædmɒn/) the earliest English poet whose name is known An Anglo Saxon who cared for cattle and was attached to the double monastery of Streonæshalch (older name for Whitby Abbey) on the Yorkshire coast during the abbacy (657 – 680) of St. Hilda

Caedmon († in ca 680) (/ˈkædmən/ or /ˈkædmɒn/) the earliest English poet whose name is known An Anglo Saxon who cared for cattle and was attached to the double monastery of Streonæshalch (older name for Whitby Abbey) on the Yorkshire coast during the abbacy (657 – 680) of St. Hilda

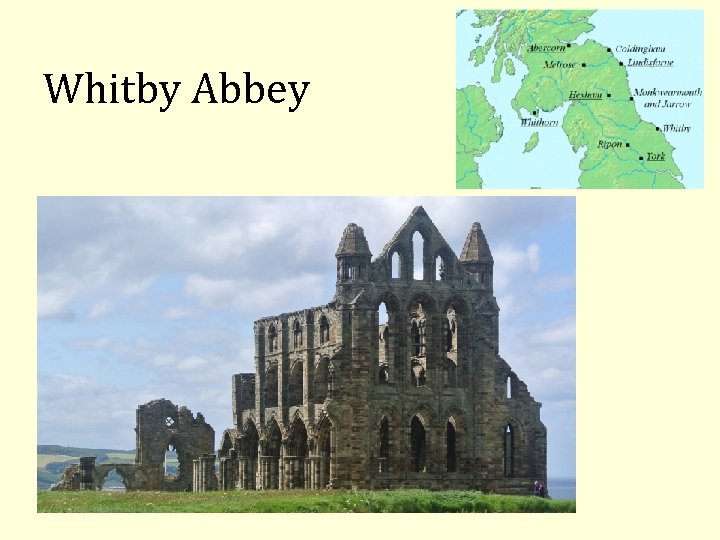

Whitby Abbey

Whitby Abbey

Caedmon – was originally ignorant of "the art of song" but learned to compose one night in a dream, according to the 8 th century monk Bede the Venerable – later became a zealous monk and an accomplished and inspirational religious poet

Caedmon – was originally ignorant of "the art of song" but learned to compose one night in a dream, according to the 8 th century monk Bede the Venerable – later became a zealous monk and an accomplished and inspirational religious poet

Caedmon’s Hymn – the first known Christian poem written in England – “One night, at a feast, when songs were called for, he stole out quietly, ashamed that he could contribute nothing to the amateur entertainment. He lay down in the cow shed and slept. In his sleep he heard a voice asking him to sing…’I cannot sing, ’ he said, ‘and that’s why I left the feast and came here. ’ ‘Nevertheless, ’ said the mysterious voice, ‘you shall sing to me. ’ ‘What shall I sing? ’ asked Caedmon. ‘Sing me the Song of Creation, ’ was the answer. ” (Burgess, 19 20)

Caedmon’s Hymn – the first known Christian poem written in England – “One night, at a feast, when songs were called for, he stole out quietly, ashamed that he could contribute nothing to the amateur entertainment. He lay down in the cow shed and slept. In his sleep he heard a voice asking him to sing…’I cannot sing, ’ he said, ‘and that’s why I left the feast and came here. ’ ‘Nevertheless, ’ said the mysterious voice, ‘you shall sing to me. ’ ‘What shall I sing? ’ asked Caedmon. ‘Sing me the Song of Creation, ’ was the answer. ” (Burgess, 19 20)

Caedmon’s Hymn Now we must praise heaven-kingdom’s Guardian, the Measurer’s might and his mind-plans, the work of the Glory Father, when he of wonders of every one, eternal Lord, the beginning established. He first created for men’s sons heaven as a roof, holy Creator; then middle-earth mankind’s Guardian, eternal Lord, afterwards made – for men earth, Master almighty.

Caedmon’s Hymn Now we must praise heaven-kingdom’s Guardian, the Measurer’s might and his mind-plans, the work of the Glory Father, when he of wonders of every one, eternal Lord, the beginning established. He first created for men’s sons heaven as a roof, holy Creator; then middle-earth mankind’s Guardian, eternal Lord, afterwards made – for men earth, Master almighty.

Caedmon – Judith once attributed to Caedmon, but scholars today agree that it was composed by Aelfric the Grammarian (955 – c. 1010), the poem is found on the Cotton manuscript (aka Beowulf manuscript) – according to Bede, Caedmon anticipated his own death

Caedmon – Judith once attributed to Caedmon, but scholars today agree that it was composed by Aelfric the Grammarian (955 – c. 1010), the poem is found on the Cotton manuscript (aka Beowulf manuscript) – according to Bede, Caedmon anticipated his own death

Cynewulf (late 8 th and early 9 th century) – 4 poems attributed to him – 2 from the Exeter Book (Christ II, Juliana) – 2 from the Vercelli Book (Elene, The Fates of the Apostles) The Dream of the Rood was attributed to him, opinions differ

Cynewulf (late 8 th and early 9 th century) – 4 poems attributed to him – 2 from the Exeter Book (Christ II, Juliana) – 2 from the Vercelli Book (Elene, The Fates of the Apostles) The Dream of the Rood was attributed to him, opinions differ

Watch: – an extract from a documentary In search of Beowulf, presented by Michael Wood (from 4. 40 Anglo Saxon Hall, the Regia Anglorum society, the Beowulf manuscript from the 9 th minute to 15. 20, and The Ruthwell Cross from 40. 32) https: //www. youtube. com/watch? v=1 C 0 s. FXU 0 SLo

Watch: – an extract from a documentary In search of Beowulf, presented by Michael Wood (from 4. 40 Anglo Saxon Hall, the Regia Anglorum society, the Beowulf manuscript from the 9 th minute to 15. 20, and The Ruthwell Cross from 40. 32) https: //www. youtube. com/watch? v=1 C 0 s. FXU 0 SLo

Lecture no. 4 Christianity in Britain / Bede (673 – 735) 5 th Century (since 410 Romans under threat) A Ss mercenaries are the first new invaders (originally hired by the Celtic king Vortigern, brothers Hengest and Horsa are believed to have been the chief warriors leading A Ss) Names to remember: St. Patrick (? 5 th Century) a Romano British Christian missionary turbulent youth, enslaved by the Irish c. 432 came to Ireland again and converted the Irish

Lecture no. 4 Christianity in Britain / Bede (673 – 735) 5 th Century (since 410 Romans under threat) A Ss mercenaries are the first new invaders (originally hired by the Celtic king Vortigern, brothers Hengest and Horsa are believed to have been the chief warriors leading A Ss) Names to remember: St. Patrick (? 5 th Century) a Romano British Christian missionary turbulent youth, enslaved by the Irish c. 432 came to Ireland again and converted the Irish

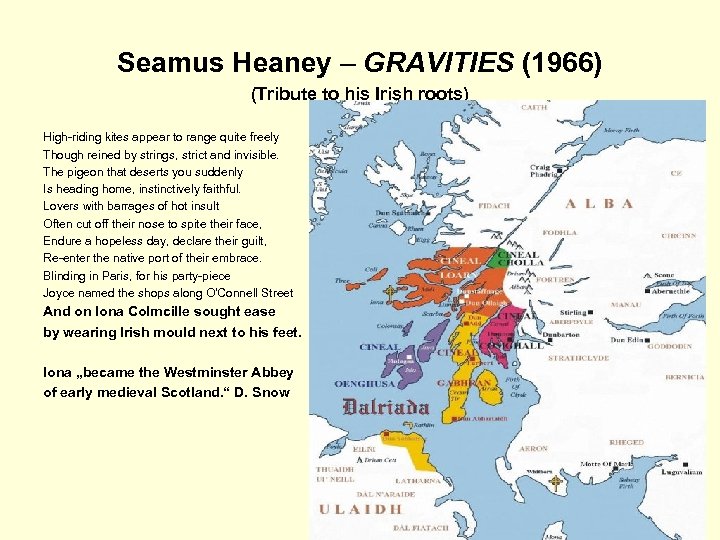

St. Columba (521 – 597) mid. 6 th century from an aristocratic family as scholar, priest, diplomat led a mission to the Picts with his 11 companions to Dalriada on a given island of Iona he established a monastery, by wisdom and miracles converted heathens,

St. Columba (521 – 597) mid. 6 th century from an aristocratic family as scholar, priest, diplomat led a mission to the Picts with his 11 companions to Dalriada on a given island of Iona he established a monastery, by wisdom and miracles converted heathens,

Seamus Heaney – GRAVITIES (1966) (Tribute to his Irish roots) High-riding kites appear to range quite freely Though reined by strings, strict and invisible. The pigeon that deserts you suddenly Is heading home, instinctively faithful. Lovers with barrages of hot insult Often cut off their nose to spite their face, Endure a hopeless day, declare their guilt, Re-enter the native port of their embrace. Blinding in Paris, for his party-piece Joyce named the shops along O'Connell Street And on Iona Colmcille sought ease by wearing Irish mould next to his feet. Iona „became the Westminster Abbey of early medieval Scotland. “ D. Snow

Seamus Heaney – GRAVITIES (1966) (Tribute to his Irish roots) High-riding kites appear to range quite freely Though reined by strings, strict and invisible. The pigeon that deserts you suddenly Is heading home, instinctively faithful. Lovers with barrages of hot insult Often cut off their nose to spite their face, Endure a hopeless day, declare their guilt, Re-enter the native port of their embrace. Blinding in Paris, for his party-piece Joyce named the shops along O'Connell Street And on Iona Colmcille sought ease by wearing Irish mould next to his feet. Iona „became the Westminster Abbey of early medieval Scotland. “ D. Snow

St. Augustine (of Canterbury) (first third of the 6 th century – 604) – belonged to the 2 nd Christian faction, the Roman Church (centralized as opposed to the Celtic Church) – sent to Britain by the Pope Gregory the Great (540 – 604, Pope since 590) Gregory on England: “The uttermost edge of the known world” – Augustine arrived in Kent in 597

St. Augustine (of Canterbury) (first third of the 6 th century – 604) – belonged to the 2 nd Christian faction, the Roman Church (centralized as opposed to the Celtic Church) – sent to Britain by the Pope Gregory the Great (540 – 604, Pope since 590) Gregory on England: “The uttermost edge of the known world” – Augustine arrived in Kent in 597

Augustine’s mission – Ethelbert, the King of Kent, (560 – 616) is the first Anglo Saxon king who converted to Christianity – Already married to Bertha, a Christian, daughter of the king of the Franks Charibert – even after first successes some kingdoms reverted to paganism

Augustine’s mission – Ethelbert, the King of Kent, (560 – 616) is the first Anglo Saxon king who converted to Christianity – Already married to Bertha, a Christian, daughter of the king of the Franks Charibert – even after first successes some kingdoms reverted to paganism

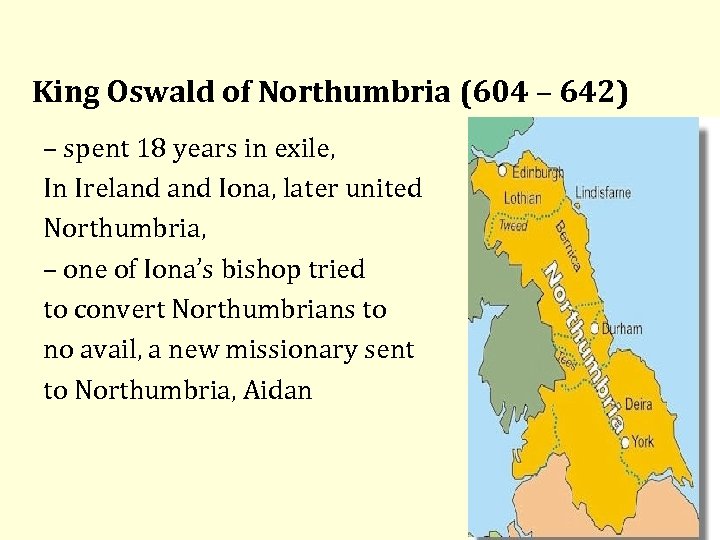

King Oswald of Northumbria (604 – 642) – spent 18 years in exile, In Ireland Iona, later united Northumbria, – one of Iona’s bishop tried to convert Northumbrians to no avail, a new missionary sent to Northumbria, Aidan

King Oswald of Northumbria (604 – 642) – spent 18 years in exile, In Ireland Iona, later united Northumbria, – one of Iona’s bishop tried to convert Northumbrians to no avail, a new missionary sent to Northumbria, Aidan

St. Aidan of Lindisfarne (590 – 651) – a young bishop, the last of the great Irish missionaries – in 635 established a church in Lindisfarne (near Bamburgh, Oswald’s castle) – Oswald translated Aidan’s Sermons to English nobility – Lindisfarne Gospels, produced c. in 700, by the monk Eadfrith (from Cotton’s collection to BM)

St. Aidan of Lindisfarne (590 – 651) – a young bishop, the last of the great Irish missionaries – in 635 established a church in Lindisfarne (near Bamburgh, Oswald’s castle) – Oswald translated Aidan’s Sermons to English nobility – Lindisfarne Gospels, produced c. in 700, by the monk Eadfrith (from Cotton’s collection to BM)

Synod of Whitby (664) Bishop Wilfrid of York (633 – 709), First Anglo Saxon churchman to visit Rome, there he met the Pope, on the side of the Roman Church, introduced written law in England, His opponent was Colmán of Lindisfarne (c. 605 – 675) After the synod Colmán left Lindisfarne, took the relics of Aidan with him to Iona, resigned – the king Oswiu (c. 612 – 670) abided by the Roman way of calculation of the date of Easter (agreed on during the Council of Nicea in 325)

Synod of Whitby (664) Bishop Wilfrid of York (633 – 709), First Anglo Saxon churchman to visit Rome, there he met the Pope, on the side of the Roman Church, introduced written law in England, His opponent was Colmán of Lindisfarne (c. 605 – 675) After the synod Colmán left Lindisfarne, took the relics of Aidan with him to Iona, resigned – the king Oswiu (c. 612 – 670) abided by the Roman way of calculation of the date of Easter (agreed on during the Council of Nicea in 325)

Beda Venerabilis (673 – 735) Ecclesiastical History of the English People (Historia Ecclesiastica Gentis Anglorum) It was written in Latin and completed in 731, “perhaps at the very time the poet of Beowulf was working on his epic. ” 1 [1] Abrams, M. H. , ed. The Norton Anthology of English Literature, v. 1, page 5

Beda Venerabilis (673 – 735) Ecclesiastical History of the English People (Historia Ecclesiastica Gentis Anglorum) It was written in Latin and completed in 731, “perhaps at the very time the poet of Beowulf was working on his epic. ” 1 [1] Abrams, M. H. , ed. The Norton Anthology of English Literature, v. 1, page 5

Bede, the Venerable (673 – 735) – recognised scholar, translator – later recognised as a saint – first English historian (his Historia is the first account of the Anglo Saxon England) – his Historia dedicated to Ceolwulf, king of Northumbria – he also wrote interpretations of the Bible, called commentaries, considered himself a Biblical commentator

Bede, the Venerable (673 – 735) – recognised scholar, translator – later recognised as a saint – first English historian (his Historia is the first account of the Anglo Saxon England) – his Historia dedicated to Ceolwulf, king of Northumbria – he also wrote interpretations of the Bible, called commentaries, considered himself a Biblical commentator

Bede, the Venerable (673 – 735) – (probably) born in Monkton (near Jarrow, the land owned by the Wearmouth monastery) – from the age of 7 a pupil of Benedict Biscop who established the double monastery of Wearmouth in 674, later Jarrow too (hence the term double monastery) – taught also by Abbot Ceolfrith (treated him as a son) – Biscop travelled the known world and collected books to establish the monastery, Bede mentions that Biscop collected some 300 books (the University of Cambridge library in the 15 th century had “only” 330 books)

Bede, the Venerable (673 – 735) – (probably) born in Monkton (near Jarrow, the land owned by the Wearmouth monastery) – from the age of 7 a pupil of Benedict Biscop who established the double monastery of Wearmouth in 674, later Jarrow too (hence the term double monastery) – taught also by Abbot Ceolfrith (treated him as a son) – Biscop travelled the known world and collected books to establish the monastery, Bede mentions that Biscop collected some 300 books (the University of Cambridge library in the 15 th century had “only” 330 books)

Bede, the Venerable (673 – 735) – probably of noble origin, but never progressed to a high office – at 19 a deacon, ordained by John, Bishop of Hexham – at 30 became a priest, and never advanced beyond – remained focused mostly on scholarship (also on physical labour to test one’s humility) – also a teacher – produced 30 books – believed to have dictated the translation of the Gospel of St. John on his deathbed

Bede, the Venerable (673 – 735) – probably of noble origin, but never progressed to a high office – at 19 a deacon, ordained by John, Bishop of Hexham – at 30 became a priest, and never advanced beyond – remained focused mostly on scholarship (also on physical labour to test one’s humility) – also a teacher – produced 30 books – believed to have dictated the translation of the Gospel of St. John on his deathbed

Ecclesiastical History of the English People • BOOK 1: The Roman background, the Anglo Saxon invasion, later Augustine from Rome • BOOK 2: Mission to Kent completed, a new one goes up to Northumbria, Kent, Penda and his army kill the king of Northumbria, Edwin • BOOK 3: Golden age, the church under Aidan and Oswald, Aidan bishop of Lindisfarne • BOOK 4: Synod of Whitby, the last pagan kingdom, Sussex, is evangelized by Wilfrid • BOOK 5: darker tone, more critical, missionary work in Frisia is pioneered by Willibrord

Ecclesiastical History of the English People • BOOK 1: The Roman background, the Anglo Saxon invasion, later Augustine from Rome • BOOK 2: Mission to Kent completed, a new one goes up to Northumbria, Kent, Penda and his army kill the king of Northumbria, Edwin • BOOK 3: Golden age, the church under Aidan and Oswald, Aidan bishop of Lindisfarne • BOOK 4: Synod of Whitby, the last pagan kingdom, Sussex, is evangelized by Wilfrid • BOOK 5: darker tone, more critical, missionary work in Frisia is pioneered by Willibrord

Watch and listen to: How the Celts saved Britain (2009) https: //www. youtube. com/watch? v=u. IBkv 7 p. U 9 Eo presented by Dan Snow (Augustine and Roman Christianity, 32. minute in the 2 nd episode) In Our Time The Venerable Bede http: //www. bbc. co. uk/programmes/p 004 y 26 h hosted by Melvyn Bragg In Our Time – The Lindisfarne Gospels http: //www. bbc. co. uk/programmes/p 00548 tq hosted by Melvyn Bragg

Watch and listen to: How the Celts saved Britain (2009) https: //www. youtube. com/watch? v=u. IBkv 7 p. U 9 Eo presented by Dan Snow (Augustine and Roman Christianity, 32. minute in the 2 nd episode) In Our Time The Venerable Bede http: //www. bbc. co. uk/programmes/p 004 y 26 h hosted by Melvyn Bragg In Our Time – The Lindisfarne Gospels http: //www. bbc. co. uk/programmes/p 00548 tq hosted by Melvyn Bragg

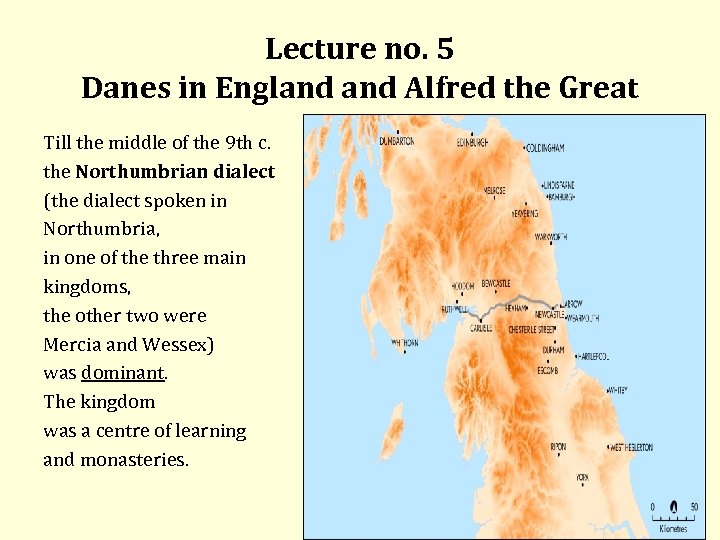

Lecture no. 5 Danes in England Alfred the Great Till the middle of the 9 th c. the Northumbrian dialect (the dialect spoken in Northumbria, in one of the three main kingdoms, the other two were Mercia and Wessex) was dominant. The kingdom was a centre of learning and monasteries.

Lecture no. 5 Danes in England Alfred the Great Till the middle of the 9 th c. the Northumbrian dialect (the dialect spoken in Northumbria, in one of the three main kingdoms, the other two were Mercia and Wessex) was dominant. The kingdom was a centre of learning and monasteries.

Danes in England The Danes invaded England changed the Northumbrian cultural heritage beyond recognition. In 793 they sacked Lindisfarne, in 794 Wearmouth Jarrow (Bede’s home), took treasures, destroyed buildings, killed priests.

Danes in England The Danes invaded England changed the Northumbrian cultural heritage beyond recognition. In 793 they sacked Lindisfarne, in 794 Wearmouth Jarrow (Bede’s home), took treasures, destroyed buildings, killed priests.

Alfred the Great’s (849 – 899) dynasty – father Aethelwulf, in 853, took him to Rome (to meet Leo IV. ) – father Aethelwulf in 857 took him there for the second time and married a Carolingian princess (only a 12 year old back then, the great grandaughter of Charlemagne) – son Edward the Elder ruled in Wessex after him – daughter Aethelflaed became the lady of the Mercians, in 918 defeated Vikings (died at 40, the same year, her daughter Aelfwyn also respected but her uncle Edward got rid oh her) – grandson Aethelstan (Edward’s son) as the first one ruled the whole of England (927 – 939)

Alfred the Great’s (849 – 899) dynasty – father Aethelwulf, in 853, took him to Rome (to meet Leo IV. ) – father Aethelwulf in 857 took him there for the second time and married a Carolingian princess (only a 12 year old back then, the great grandaughter of Charlemagne) – son Edward the Elder ruled in Wessex after him – daughter Aethelflaed became the lady of the Mercians, in 918 defeated Vikings (died at 40, the same year, her daughter Aelfwyn also respected but her uncle Edward got rid oh her) – grandson Aethelstan (Edward’s son) as the first one ruled the whole of England (927 – 939)

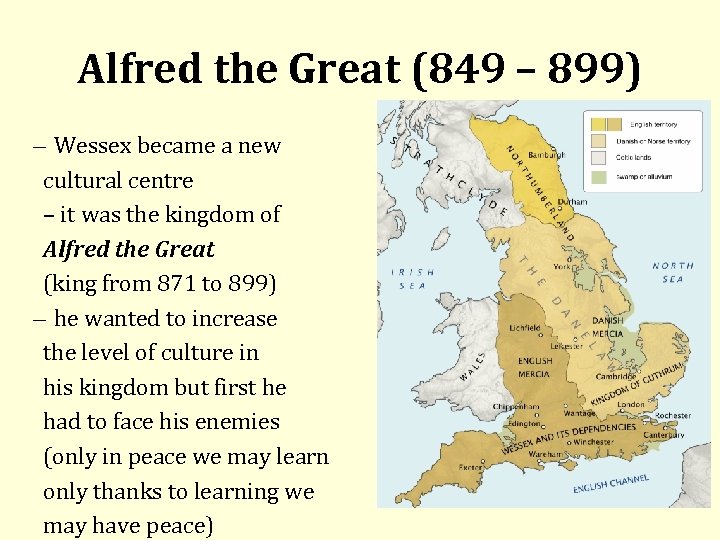

Alfred the Great (849 – 899) Wessex became a new cultural centre – it was the kingdom of Alfred the Great (king from 871 to 899) he wanted to increase the level of culture in his kingdom but first he had to face his enemies (only in peace we may learn only thanks to learning we may have peace)

Alfred the Great (849 – 899) Wessex became a new cultural centre – it was the kingdom of Alfred the Great (king from 871 to 899) he wanted to increase the level of culture in his kingdom but first he had to face his enemies (only in peace we may learn only thanks to learning we may have peace)

Alfred the Great (849 – 899), during his reign: the Danelaw was formed OE was authorized as a language for written texts a programme of education in the vernacular was initiated he summoned scholars to translate the most influential books known in Christendom,

Alfred the Great (849 – 899), during his reign: the Danelaw was formed OE was authorized as a language for written texts a programme of education in the vernacular was initiated he summoned scholars to translate the most influential books known in Christendom,

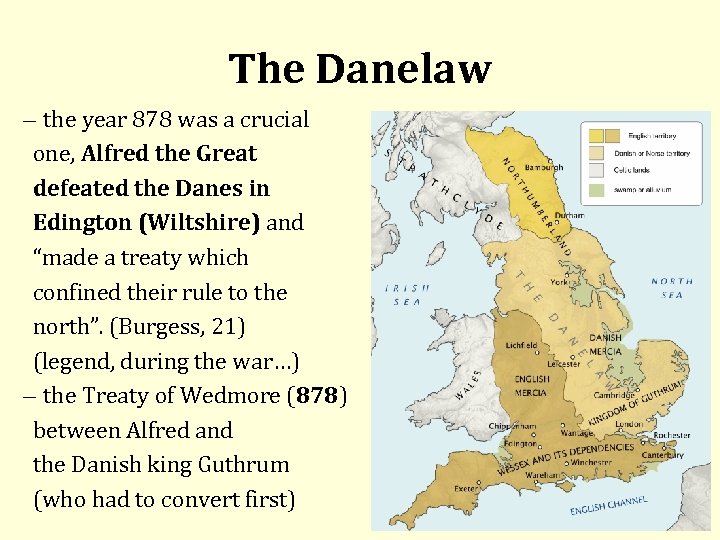

The Danelaw the year 878 was a crucial one, Alfred the Great defeated the Danes in Edington (Wiltshire) and “made a treaty which confined their rule to the north”. (Burgess, 21) (legend, during the war…) the Treaty of Wedmore (878) between Alfred and the Danish king Guthrum (who had to convert first)

The Danelaw the year 878 was a crucial one, Alfred the Great defeated the Danes in Edington (Wiltshire) and “made a treaty which confined their rule to the north”. (Burgess, 21) (legend, during the war…) the Treaty of Wedmore (878) between Alfred and the Danish king Guthrum (who had to convert first)

Alfred the Great (849 – 899) and his library St. Augustine – Soliloquies Gregory The Great (the Pope) – Cura Pastoralis (c. 590, originally brought to England by Augustine of Canterbury back in 597) and Dialogues Bede – Ecclesiastical History (731) probably translated by his fellows – Orosius – Historiae adversus paganos (c. 417) – Boethius – Consolation of Philosophy (523) + Anglo Saxon Chronicle was started! – the Welsh bishop Asser was his mentor and biographer (the biography, The Life of King Alfred, 893, burnt in 1731, fortunately Tudors had copied it for future generations)

Alfred the Great (849 – 899) and his library St. Augustine – Soliloquies Gregory The Great (the Pope) – Cura Pastoralis (c. 590, originally brought to England by Augustine of Canterbury back in 597) and Dialogues Bede – Ecclesiastical History (731) probably translated by his fellows – Orosius – Historiae adversus paganos (c. 417) – Boethius – Consolation of Philosophy (523) + Anglo Saxon Chronicle was started! – the Welsh bishop Asser was his mentor and biographer (the biography, The Life of King Alfred, 893, burnt in 1731, fortunately Tudors had copied it for future generations)

Alfred the Great, the dialect He preserved what remained from the Northumbrian culture and improved the state of education in Wessex. The West Saxon or Wessex English finally became the main English dialect – i. e. the southern dialect

Alfred the Great, the dialect He preserved what remained from the Northumbrian culture and improved the state of education in Wessex. The West Saxon or Wessex English finally became the main English dialect – i. e. the southern dialect

Anglo-Saxon Chronicle Another famous source of historical information is the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle (started in 891), written, of course, in Old English including all important events which happened between the middle of the ninth century and the year 1154. The Chronicle is one of the most solid pieces of Old English prose although, at the same time, we can observe the continual transition from Old English towards Middle English.

Anglo-Saxon Chronicle Another famous source of historical information is the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle (started in 891), written, of course, in Old English including all important events which happened between the middle of the ninth century and the year 1154. The Chronicle is one of the most solid pieces of Old English prose although, at the same time, we can observe the continual transition from Old English towards Middle English.

The Anglo-Saxon Chronicle on Edward “And many people who had been under the rule of the Danes in East Anglia and in Essex submitted to him; and all the army in East Anglia swore agreement with him, that they [agree to] all that he would, and keep peace with all whom the king wished to keep peace, both at sea and on land. ” (see Strong, p. 36)

The Anglo-Saxon Chronicle on Edward “And many people who had been under the rule of the Danes in East Anglia and in Essex submitted to him; and all the army in East Anglia swore agreement with him, that they [agree to] all that he would, and keep peace with all whom the king wished to keep peace, both at sea and on land. ” (see Strong, p. 36)

th century Benedictine 10 reform movement King Edgar, great-grandson of Alfred the Great (reigned 959 975) supported the revival of learning and organized production of manuscripts (son of Edmund, grandson of Edward) the 4 major codices produced in the West. Saxon dialect (see the slides 28 to 32)

th century Benedictine 10 reform movement King Edgar, great-grandson of Alfred the Great (reigned 959 975) supported the revival of learning and organized production of manuscripts (son of Edmund, grandson of Edward) the 4 major codices produced in the West. Saxon dialect (see the slides 28 to 32)

The Battle of Maldon From the Cotton Manuscript (but a copy had been made before) originally in verse, in NA in its prose translation gives a historical account, a Viking raid in 991, in Essex Birhtnoth, the earl of Essex, lost the battle (during the reign of Ethelred “the Unready”, ruled from 978 to 1016) Birhtnoth refuses to pay tribute (tribute money). “…point and edge shall reconcile us, grim battle play, before we give tribute. … Now the way is laid open for you. Come straightaway to us, as men to battle. God alone knows which of us may be master of the field. ” p. 95

The Battle of Maldon From the Cotton Manuscript (but a copy had been made before) originally in verse, in NA in its prose translation gives a historical account, a Viking raid in 991, in Essex Birhtnoth, the earl of Essex, lost the battle (during the reign of Ethelred “the Unready”, ruled from 978 to 1016) Birhtnoth refuses to pay tribute (tribute money). “…point and edge shall reconcile us, grim battle play, before we give tribute. … Now the way is laid open for you. Come straightaway to us, as men to battle. God alone knows which of us may be master of the field. ” p. 95

The Adventures of English (1 st episode, from the 23 rd on) https: //www. youtube. com/watch? v=iho. YL-d. UK 1 g

The Adventures of English (1 st episode, from the 23 rd on) https: //www. youtube. com/watch? v=iho. YL-d. UK 1 g

Watch: In Search of Alfred the Great https: //www. youtube. com/watch? v=7 Ab. Hq 1 Mu. I 4 o presented by Michael Wood

Watch: In Search of Alfred the Great https: //www. youtube. com/watch? v=7 Ab. Hq 1 Mu. I 4 o presented by Michael Wood

Lecture no 6. Aelfric // Normans in Britain Aelfric the Grammarian, Abbot of Eynsham (c. 955 – 1010) a product of the Benedictine reform, educated by Aethelwold at Winchester along with his contemporary Wulfstan, bishop of Worchester and archbishop of York, provided a substanial body of prose wrote Catholic Homilies, Lives of Saints and Grammar, plus the very first Latin English dictionary

Lecture no 6. Aelfric // Normans in Britain Aelfric the Grammarian, Abbot of Eynsham (c. 955 – 1010) a product of the Benedictine reform, educated by Aethelwold at Winchester along with his contemporary Wulfstan, bishop of Worchester and archbishop of York, provided a substanial body of prose wrote Catholic Homilies, Lives of Saints and Grammar, plus the very first Latin English dictionary

Aelfric’s Catholic Homilies 40 of them, only 30 have survived written in between 980 s and 995, at Cerne Abbes in Dorset where we was sent in ca. 987 the author wanted to spread the word among lay people: “He desires to create a body of vernacular didactic prose marks him out as a remarkable author in this period, and he clearly allies his educational aims with those of King Alfred in his programme of translating essential Latin works into the native tongue. ” (Treharne, p. 116)

Aelfric’s Catholic Homilies 40 of them, only 30 have survived written in between 980 s and 995, at Cerne Abbes in Dorset where we was sent in ca. 987 the author wanted to spread the word among lay people: “He desires to create a body of vernacular didactic prose marks him out as a remarkable author in this period, and he clearly allies his educational aims with those of King Alfred in his programme of translating essential Latin works into the native tongue. ” (Treharne, p. 116)

Aelfric’s Preface to Catholic Homilies a work of prophetic proportions, originaly in Latin but translated into OE by the author: “Then it came into my mind, I believe through the grace of God, that I should translate this book from the language of Latin into English, not through the confidence of great learning, but because I saw and heard much heresy in many English books. […] For this reason I presumed, trusting in God, to undertake this composition, and also because men have need of good teachings above all at this time, which is the ending of this world. ” (see Treharne, p. 117)

Aelfric’s Preface to Catholic Homilies a work of prophetic proportions, originaly in Latin but translated into OE by the author: “Then it came into my mind, I believe through the grace of God, that I should translate this book from the language of Latin into English, not through the confidence of great learning, but because I saw and heard much heresy in many English books. […] For this reason I presumed, trusting in God, to undertake this composition, and also because men have need of good teachings above all at this time, which is the ending of this world. ” (see Treharne, p. 117)

Translation vs. adaptation translation is a functionally corresponding reproduction of the invariant information found in the source text using expressions of the target language to create a new text (see Vilikovský, 1984) “Adaptations go beyond translations; they alter literary works by bringing them into a different medium. ” (Di. Yanni, p. 545) The principles of textual completeness, meaning identity and also formal identity are not followed (see Ferenčík, 1982) these texts (aka paraphrases) were very popular (Caedmon, for example, composed poetry on biblical subjects from Genesis to Last Judgment, they have not survived, though).

Translation vs. adaptation translation is a functionally corresponding reproduction of the invariant information found in the source text using expressions of the target language to create a new text (see Vilikovský, 1984) “Adaptations go beyond translations; they alter literary works by bringing them into a different medium. ” (Di. Yanni, p. 545) The principles of textual completeness, meaning identity and also formal identity are not followed (see Ferenčík, 1982) these texts (aka paraphrases) were very popular (Caedmon, for example, composed poetry on biblical subjects from Genesis to Last Judgment, they have not survived, though).

Judith Aelfric’s Judith is virtually Book of Judith placed into “a recognizably Germanic cultural setting” (Greenblatt, S. et al. , p. 100) St. Jerome’s Book of Judith translation was rather free in its own right (Jerome translated the book sense for sense, not word for word) Book of Judith considered apocryphal 1 (not part of Protestant Bibles), it is not a historical novel rather a pseudohistorical narrative with a religious message 1 V slovenskej protestantskej „terminológii sa názvom apokryfy označujú spisy, ktoré sa v katolíckom kánone nazývajú deuterokanonické knihy Starého zákona, kým nekanonické spisy, ktoré katolíci označujú názvom apokryfy, protestanti nazývajú pseudoepigrafy. V snahe vyhnúť tomuto rečovému chaosu sa v nemeckom ekumenickom preklade Biblie pre deuterokanonické knihy Starého zákona zaviedol názov «neskoršie spisy Starého zákona» (Heriban, 218 219).

Judith Aelfric’s Judith is virtually Book of Judith placed into “a recognizably Germanic cultural setting” (Greenblatt, S. et al. , p. 100) St. Jerome’s Book of Judith translation was rather free in its own right (Jerome translated the book sense for sense, not word for word) Book of Judith considered apocryphal 1 (not part of Protestant Bibles), it is not a historical novel rather a pseudohistorical narrative with a religious message 1 V slovenskej protestantskej „terminológii sa názvom apokryfy označujú spisy, ktoré sa v katolíckom kánone nazývajú deuterokanonické knihy Starého zákona, kým nekanonické spisy, ktoré katolíci označujú názvom apokryfy, protestanti nazývajú pseudoepigrafy. V snahe vyhnúť tomuto rečovému chaosu sa v nemeckom ekumenickom preklade Biblie pre deuterokanonické knihy Starého zákona zaviedol názov «neskoršie spisy Starého zákona» (Heriban, 218 219).

Judith Aelfric’s adaptation has, among others, a strong patriotic message (a parallel between Judith’s people and Anglo Saxons being threatened by an enemy, Vikings recent past, premonitions of something more tragic to come) as a part of the Cotton manuscript follows Beowulf (in 1731 a great part of it burned, lost parts supplied from the Edward Thwaites’s version he had produced in 1698, still ca. 100 lines are missing)

Judith Aelfric’s adaptation has, among others, a strong patriotic message (a parallel between Judith’s people and Anglo Saxons being threatened by an enemy, Vikings recent past, premonitions of something more tragic to come) as a part of the Cotton manuscript follows Beowulf (in 1731 a great part of it burned, lost parts supplied from the Edward Thwaites’s version he had produced in 1698, still ca. 100 lines are missing)

the Biblical (Apocryphal) Judith as compared to Aelfric’s Judith Differences (to name but a few) 1. An Old Testament text – a Christianized narrative, even Christian diction (Trinity, anachronism) 2. 16 chapters – 350 lines (in medias res story) 3. An omniscient narrator – 1 st person, unreliable, lines 8 and 246 4. Standard Biblical diction – A S expressions, e. g. mail coated warriors, spear play, dispenser of treasures 5. God – variations, epithets denoting God typical of A S poetry, e. g. lines 59, 61: “The Judge of glory, the majestic Guardian, the Lord, Ruler of hosts…”, (more discussed at the seminar)

the Biblical (Apocryphal) Judith as compared to Aelfric’s Judith Differences (to name but a few) 1. An Old Testament text – a Christianized narrative, even Christian diction (Trinity, anachronism) 2. 16 chapters – 350 lines (in medias res story) 3. An omniscient narrator – 1 st person, unreliable, lines 8 and 246 4. Standard Biblical diction – A S expressions, e. g. mail coated warriors, spear play, dispenser of treasures 5. God – variations, epithets denoting God typical of A S poetry, e. g. lines 59, 61: “The Judge of glory, the majestic Guardian, the Lord, Ruler of hosts…”, (more discussed at the seminar)

Normans, defining moment A profound change came in 1066 with the Normans who also changed the local way of life as well as the Language beyond recognition. William the Conqueror defeated Harold Godwineson (Harold II. )

Normans, defining moment A profound change came in 1066 with the Normans who also changed the local way of life as well as the Language beyond recognition. William the Conqueror defeated Harold Godwineson (Harold II. )

Harold vs. William contacts with Normandy rather close even during the reign of Edward the Confessor (1042 – 1066), Edward was brought up in Normandy by his mother Emma who was a Norman herself Edward’s burial service took place the same day (at the same place, January 1066, Westminster Abbey) as Harold’s coronation “Harold had allegedly pledged his support some years earlier to William in his claim on the throne, and thus William attacked to regain his crown. ” (Treharne, p. XVIII)

Harold vs. William contacts with Normandy rather close even during the reign of Edward the Confessor (1042 – 1066), Edward was brought up in Normandy by his mother Emma who was a Norman herself Edward’s burial service took place the same day (at the same place, January 1066, Westminster Abbey) as Harold’s coronation “Harold had allegedly pledged his support some years earlier to William in his claim on the throne, and thus William attacked to regain his crown. ” (Treharne, p. XVIII)

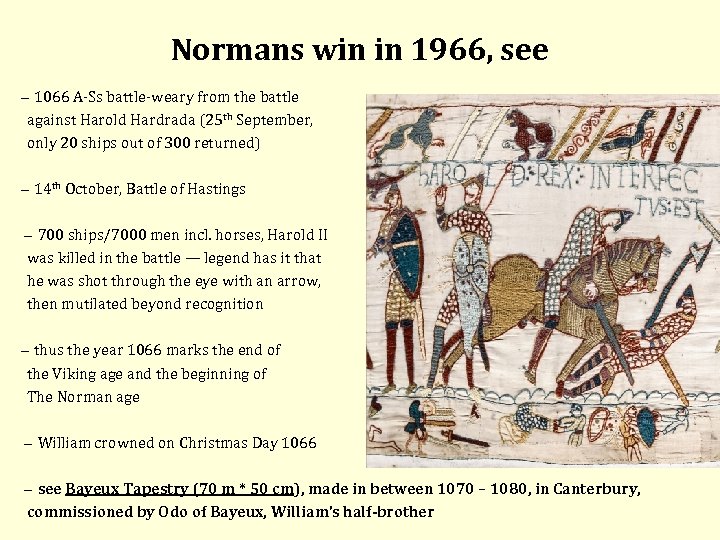

Normans win in 1966, see 1066 A Ss battle weary from the battle against Harold Hardrada (25 th September, only 20 ships out of 300 returned) 14 th October, Battle of Hastings 700 ships/7000 men incl. horses, Harold II was killed in the battle — legend has it that he was shot through the eye with an arrow, then mutilated beyond recognition thus the year 1066 marks the end of the Viking age and the beginning of The Norman age William crowned on Christmas Day 1066 see Bayeux Tapestry (70 m * 50 cm), made in between 1070 – 1080, in Canterbury, commissioned by Odo of Bayeux, William’s half-brother

Normans win in 1966, see 1066 A Ss battle weary from the battle against Harold Hardrada (25 th September, only 20 ships out of 300 returned) 14 th October, Battle of Hastings 700 ships/7000 men incl. horses, Harold II was killed in the battle — legend has it that he was shot through the eye with an arrow, then mutilated beyond recognition thus the year 1066 marks the end of the Viking age and the beginning of The Norman age William crowned on Christmas Day 1066 see Bayeux Tapestry (70 m * 50 cm), made in between 1070 – 1080, in Canterbury, commissioned by Odo of Bayeux, William’s half-brother

Normans in England Normans were of the same blood as the Danes but they had already absorbed the Roman culture they spoke a Latin offshoot which is known as Norman French (the word “Norman” is derived from “North-man”) 1069 – castle building project, to secure his control of the north

Normans in England Normans were of the same blood as the Danes but they had already absorbed the Roman culture they spoke a Latin offshoot which is known as Norman French (the word “Norman” is derived from “North-man”) 1069 – castle building project, to secure his control of the north

The Anglo-Saxon Chronicle on the new rule William’s two regents: “Bishop Odo and Earl William [fitz. Osbern of Hereford] were left behind here, and they built castles far and wide throughout the land, oppressing the unhappy people, and things went ever from bad to worse. ” (Strong, p. 49) The nobility was replaced, as well as clergy – Anglo Saxon priests replaced by Norman ones, who had to remain celibate.

The Anglo-Saxon Chronicle on the new rule William’s two regents: “Bishop Odo and Earl William [fitz. Osbern of Hereford] were left behind here, and they built castles far and wide throughout the land, oppressing the unhappy people, and things went ever from bad to worse. ” (Strong, p. 49) The nobility was replaced, as well as clergy – Anglo Saxon priests replaced by Norman ones, who had to remain celibate.

The Anglo-Saxon Chronicle on suppression of revolts (York, 1069 70) “William in the fullness of his wrath ordered the corn and cattle, with the implements of husbandry and every sort of provisions, to be collected in heaps and set on fire until the whole was consumed and thus destroyed at once all that could serve for support of life in the whole country lying beyond the Humber. ” (Strong, p. 49)

The Anglo-Saxon Chronicle on suppression of revolts (York, 1069 70) “William in the fullness of his wrath ordered the corn and cattle, with the implements of husbandry and every sort of provisions, to be collected in heaps and set on fire until the whole was consumed and thus destroyed at once all that could serve for support of life in the whole country lying beyond the Humber. ” (Strong, p. 49)

New language “Heavy footed Old English was to become – through its mingling with a lighter, brighter tongue from sunnier lands – the richest and most various literary medium in the whole of history. ” (Burgess, 22)

New language “Heavy footed Old English was to become – through its mingling with a lighter, brighter tongue from sunnier lands – the richest and most various literary medium in the whole of history. ” (Burgess, 22)

Domesday // Domesday Book – an inventory book, a catalogue of the king’s property in England the language spoken in England is known as Anglo-Norman local monks, fluent in Old English, used Latin 11 th century manuscript vanished, over a hundred of them, in the 12 th only 30 of them

Domesday // Domesday Book – an inventory book, a catalogue of the king’s property in England the language spoken in England is known as Anglo-Norman local monks, fluent in Old English, used Latin 11 th century manuscript vanished, over a hundred of them, in the 12 th only 30 of them

A new language? The phase of transition The Old English language and literature lost their importance and were remembered only in the books which were preserved in monasteries. The Norman writers were developing their own language – not Old English, not Norman French, since they lived in England virtually lost their contacts with their mother country

A new language? The phase of transition The Old English language and literature lost their importance and were remembered only in the books which were preserved in monasteries. The Norman writers were developing their own language – not Old English, not Norman French, since they lived in England virtually lost their contacts with their mother country

Watch and listen to: The Adventures of English 1. DVD – 1. episode – Normans (approx. 10 minutes from the end) http: //www. bbc. co. uk/programmes/b 009 q 7 zm Melvyn Bragg’s In our time – The Norman Yoke http: //www. bbc. co. uk/programmes/b 040 llvb Melvyn Bragg’s In our time – The Domesday Book

Watch and listen to: The Adventures of English 1. DVD – 1. episode – Normans (approx. 10 minutes from the end) http: //www. bbc. co. uk/programmes/b 009 q 7 zm Melvyn Bragg’s In our time – The Norman Yoke http: //www. bbc. co. uk/programmes/b 040 llvb Melvyn Bragg’s In our time – The Domesday Book

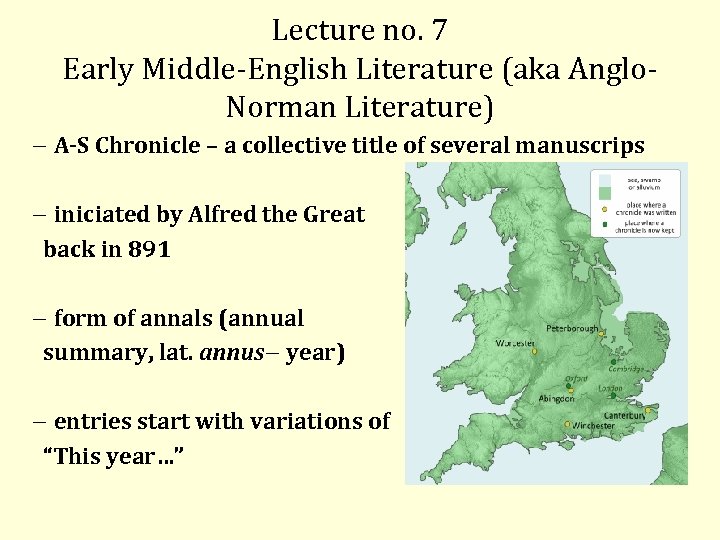

Lecture no. 7 Early Middle English Literature (aka Anglo Norman Literature) A-S Chronicle – a collective title of several manuscrips iniciated by Alfred the Great back in 891 form of annals (annual summary, lat. annus year) entries start with variations of “This year…”

Lecture no. 7 Early Middle English Literature (aka Anglo Norman Literature) A-S Chronicle – a collective title of several manuscrips iniciated by Alfred the Great back in 891 form of annals (annual summary, lat. annus year) entries start with variations of “This year…”

The Peterborough Chronicle is the latest version, aka as Manuscript E of A-S CH, now found in the Bodleian Library at the University of Oxford documents Norman rule from an English point of view, continued until the year 1154 “one of the most important pieces od transitional English writing…” (Treharne, p. 254) “… the inflectional system of Old English is beginning to break down, word order is usually S-V-O, and there are numerous French loanwords. ” (Ibid. )

The Peterborough Chronicle is the latest version, aka as Manuscript E of A-S CH, now found in the Bodleian Library at the University of Oxford documents Norman rule from an English point of view, continued until the year 1154 “one of the most important pieces od transitional English writing…” (Treharne, p. 254) “… the inflectional system of Old English is beginning to break down, word order is usually S-V-O, and there are numerous French loanwords. ” (Ibid. )

Constant development – four languages coexisted in Anglo Norman England – the English language was in a constant development acquiring many French words and losing some typical linguistic features found in the Old English language – the head rhyme lost its importance and the end rhyme became more common (the last notable work featuring the Anglo Saxon head rhyme is the 14 th century poem Piers Plowman by W. Langland)

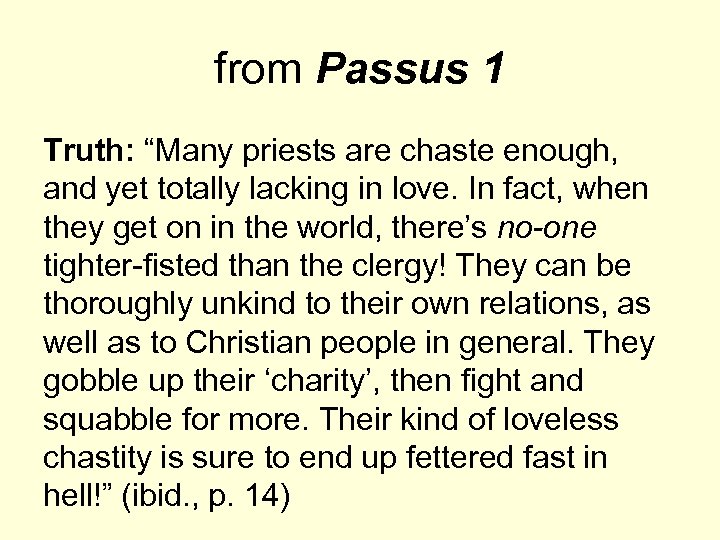

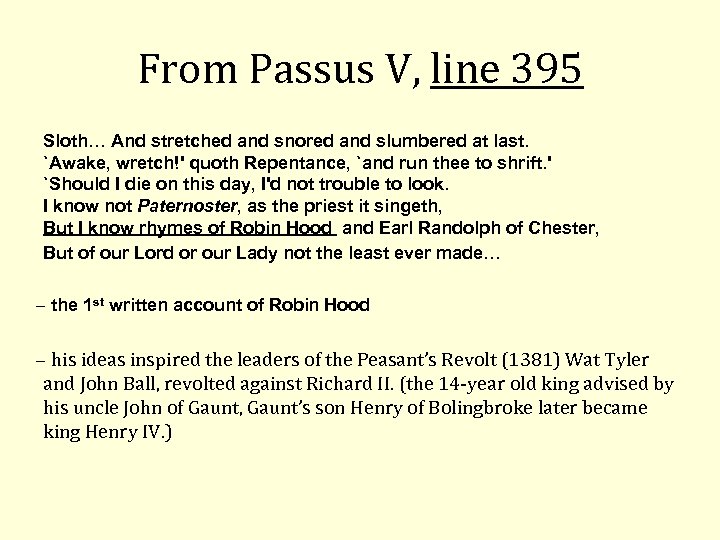

Constant development – four languages coexisted in Anglo Norman England – the English language was in a constant development acquiring many French words and losing some typical linguistic features found in the Old English language – the head rhyme lost its importance and the end rhyme became more common (the last notable work featuring the Anglo Saxon head rhyme is the 14 th century poem Piers Plowman by W. Langland)

Genres besides poetry and prose a new genre becomes favourite – drama the first play in Anglo Norman dialect of French produced in England is The Play of Adam (stage directions in Latin) the Anglo Norman aristocracy fond of Celtic legends and tales known for centuries (e. g. King Arthur)

Genres besides poetry and prose a new genre becomes favourite – drama the first play in Anglo Norman dialect of French produced in England is The Play of Adam (stage directions in Latin) the Anglo Norman aristocracy fond of Celtic legends and tales known for centuries (e. g. King Arthur)

Romance innovators writing romances were Thomas of England, Marie de France and Chrétien de Troyes the word “roman” initially applied in French to a work written in the French vernacular, i. e. Roman de Troie would mean a long poem about the Trojan War in French romances included love stories, later the term “romance” used to denote a story about love and adventure romances of chivalry very popular Marie de France wrote short romances called “lays”

Romance innovators writing romances were Thomas of England, Marie de France and Chrétien de Troyes the word “roman” initially applied in French to a work written in the French vernacular, i. e. Roman de Troie would mean a long poem about the Trojan War in French romances included love stories, later the term “romance” used to denote a story about love and adventure romances of chivalry very popular Marie de France wrote short romances called “lays”

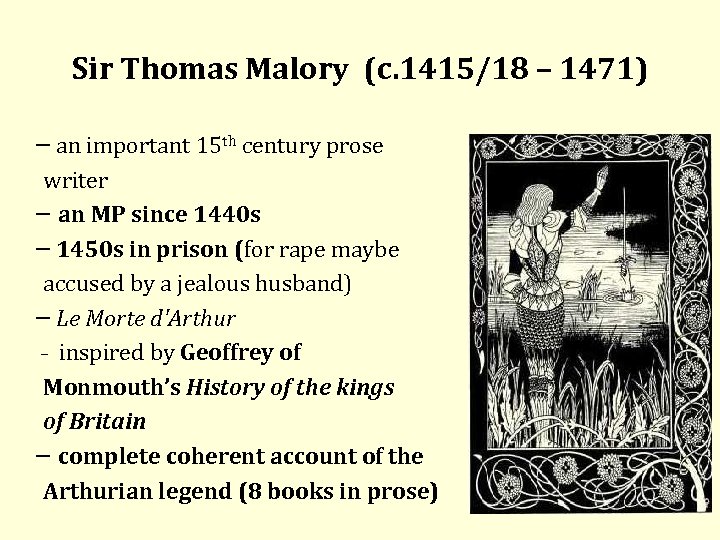

Geoffrey of Monmouth (1100 1155) a British (Welsh) monk Geoffrey of Monmouth wrote (in Latin) a “historical” book titled The History of the Kings of Britain (1136 -38), purely fictional and based on old mythology and legends of King Arthur the book allegedly based on a Welsh historical source (in the British language) which was never found though (given to him by his friend Walter) the book harks back to the Roman times, King Arthur allegedly defeated Romans the Latin original later translated into French rhyme by an Anglo. Norman poet known as Wace (1155), Wace’s version later turned to a poem that combines English alliterative verse with sporadic rhyme by Layamon (an English priest, in 1190)

Geoffrey of Monmouth (1100 1155) a British (Welsh) monk Geoffrey of Monmouth wrote (in Latin) a “historical” book titled The History of the Kings of Britain (1136 -38), purely fictional and based on old mythology and legends of King Arthur the book allegedly based on a Welsh historical source (in the British language) which was never found though (given to him by his friend Walter) the book harks back to the Roman times, King Arthur allegedly defeated Romans the Latin original later translated into French rhyme by an Anglo. Norman poet known as Wace (1155), Wace’s version later turned to a poem that combines English alliterative verse with sporadic rhyme by Layamon (an English priest, in 1190)

King Arthur The legend of the King Arthur began to fascinate the English people and even the Normans. It is a paradox because Arthur, if he ever existed, was an Old Briton coming from the nation which was driven away to Wales by the Anglo Saxon, yet the Anglo Saxon themselves were spreading his legend.

King Arthur The legend of the King Arthur began to fascinate the English people and even the Normans. It is a paradox because Arthur, if he ever existed, was an Old Briton coming from the nation which was driven away to Wales by the Anglo Saxon, yet the Anglo Saxon themselves were spreading his legend.

The History of the Kings of Britain inspired by Virgil’s (70 – 19 BCE) Aeneid, draws upon it Aeneas’s grand-grandson Brutus established a new Troy (on the British Isles) before, on the island of Leogetia, he prays to Diana The history discredited as late as in the 17 th century

The History of the Kings of Britain inspired by Virgil’s (70 – 19 BCE) Aeneid, draws upon it Aeneas’s grand-grandson Brutus established a new Troy (on the British Isles) before, on the island of Leogetia, he prays to Diana The history discredited as late as in the 17 th century

Brutus: Mighty goddess of woodlands, terror of the wild boar, Thou who art free to traverse the ethereal heavens And the mansions of hell, disclose my rights on this earth And say what lands it is your wish for us to inhabit, What dwelling-place where I shall worship you all my life, Where I shall dedicate temples to you with virgin choirs.

Brutus: Mighty goddess of woodlands, terror of the wild boar, Thou who art free to traverse the ethereal heavens And the mansions of hell, disclose my rights on this earth And say what lands it is your wish for us to inhabit, What dwelling-place where I shall worship you all my life, Where I shall dedicate temples to you with virgin choirs.

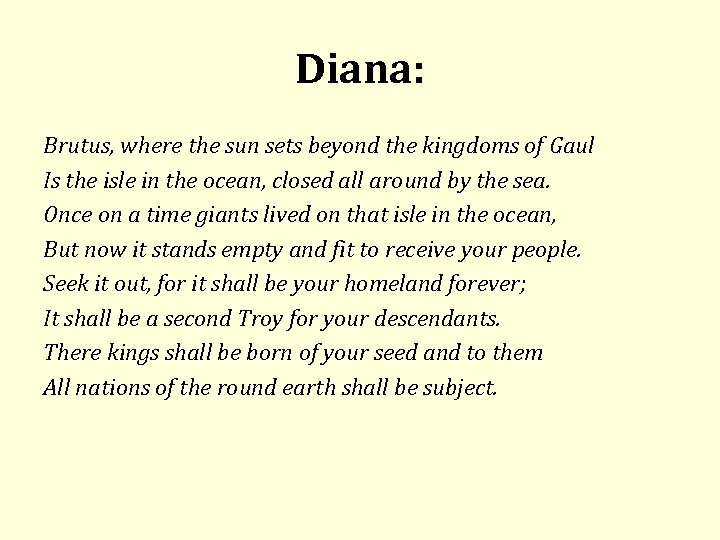

Diana: Brutus, where the sun sets beyond the kingdoms of Gaul Is the isle in the ocean, closed all around by the sea. Once on a time giants lived on that isle in the ocean, But now it stands empty and fit to receive your people. Seek it out, for it shall be your homeland forever; It shall be a second Troy for your descendants. There kings shall be born of your seed and to them All nations of the round earth shall be subject.

Diana: Brutus, where the sun sets beyond the kingdoms of Gaul Is the isle in the ocean, closed all around by the sea. Once on a time giants lived on that isle in the ocean, But now it stands empty and fit to receive your people. Seek it out, for it shall be your homeland forever; It shall be a second Troy for your descendants. There kings shall be born of your seed and to them All nations of the round earth shall be subject.

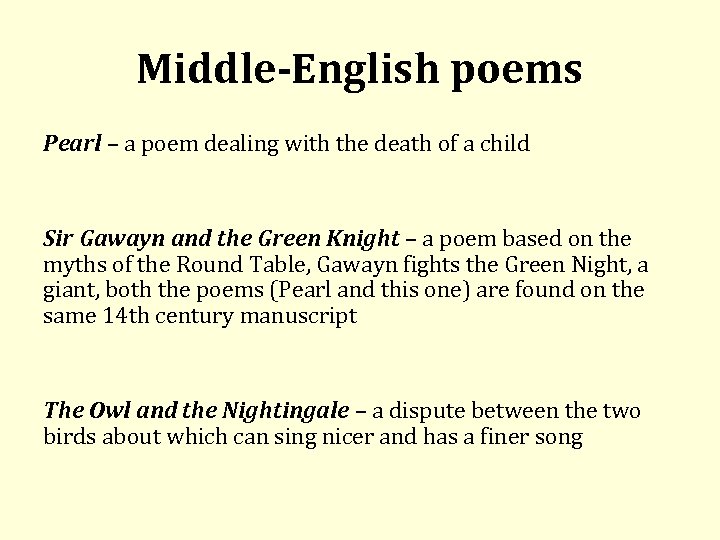

Middle-English poems Pearl – a poem dealing with the death of a child Sir Gawayn and the Green Knight – a poem based on the myths of the Round Table, Gawayn fights the Green Night, a giant, both the poems (Pearl and this one) are found on the same 14 th century manuscript The Owl and the Nightingale – a dispute between the two birds about which can sing nicer and has a finer song

Middle-English poems Pearl – a poem dealing with the death of a child Sir Gawayn and the Green Knight – a poem based on the myths of the Round Table, Gawayn fights the Green Night, a giant, both the poems (Pearl and this one) are found on the same 14 th century manuscript The Owl and the Nightingale – a dispute between the two birds about which can sing nicer and has a finer song

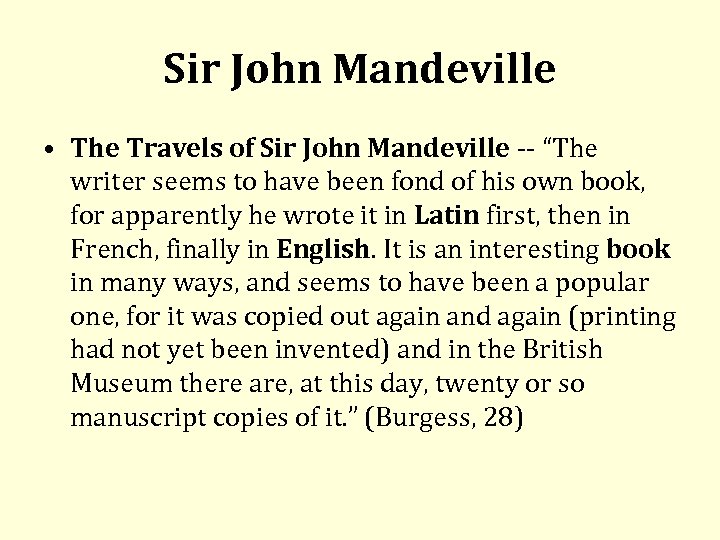

Sir John Mandeville • The Travels of Sir John Mandeville “The writer seems to have been fond of his own book, for apparently he wrote it in Latin first, then in French, finally in English. It is an interesting book in many ways, and seems to have been a popular one, for it was copied out again and again (printing had not yet been invented) and in the British Museum there are, at this day, twenty or so manuscript copies of it. ” (Burgess, 28)

Sir John Mandeville • The Travels of Sir John Mandeville “The writer seems to have been fond of his own book, for apparently he wrote it in Latin first, then in French, finally in English. It is an interesting book in many ways, and seems to have been a popular one, for it was copied out again and again (printing had not yet been invented) and in the British Museum there are, at this day, twenty or so manuscript copies of it. ” (Burgess, 28)

Watch and listen to: • • Adventure of English DVD 1 – 2. episode, Normans, from the Beginning, In our Time – The Norman Yoke http: //www. bbc. co. uk/programmes/b 009 q 7 zm

Watch and listen to: • • Adventure of English DVD 1 – 2. episode, Normans, from the Beginning, In our Time – The Norman Yoke http: //www. bbc. co. uk/programmes/b 009 q 7 zm

Lecture no. 8 The English Bible Pope Damasus I. commissioned St. Jerome in 382 to revise the Vetus Latina ("Old Latin") in 384 it was completed from 390 to 405 he translated anew from Hebrew – Vulgate (Old Testament, New Testament translated later, gospels by Jerome, though) this Latin version remained in use, only fragments sometimes translated, more often adapted or paraphrased the church interpreted the texts to laypeople itself

Lecture no. 8 The English Bible Pope Damasus I. commissioned St. Jerome in 382 to revise the Vetus Latina ("Old Latin") in 384 it was completed from 390 to 405 he translated anew from Hebrew – Vulgate (Old Testament, New Testament translated later, gospels by Jerome, though) this Latin version remained in use, only fragments sometimes translated, more often adapted or paraphrased the church interpreted the texts to laypeople itself

John Wycliffe (c. 1330 – 1384) an Oxford scholar the Wycliffite Bible – the first translation of the complete Bible into English in between 1380 and 1384 (by him and his assistants at Oxford, they used Vulgate from 405 AD as a prototext) believed that one should be granted access to the crucial text in a language that one could understand (vernacular, i. e. not Latin, but the language of the people) him and his followers denounced as Lollards (whisperers)

John Wycliffe (c. 1330 – 1384) an Oxford scholar the Wycliffite Bible – the first translation of the complete Bible into English in between 1380 and 1384 (by him and his assistants at Oxford, they used Vulgate from 405 AD as a prototext) believed that one should be granted access to the crucial text in a language that one could understand (vernacular, i. e. not Latin, but the language of the people) him and his followers denounced as Lollards (whisperers)

John Purvey (c. 1354 – c. 1414) after Wicliffe’s death Purvey revised the first edition the second Wycliffite Bible contains a general Prologue (composed between 1395 – 1396) the 15 th chapter of the Prologue describes the four stages of the translation process

John Purvey (c. 1354 – c. 1414) after Wicliffe’s death Purvey revised the first edition the second Wycliffite Bible contains a general Prologue (composed between 1395 – 1396) the 15 th chapter of the Prologue describes the four stages of the translation process

John Purvey (c. 1354 – c. 1414) the four stages 1. a collaborative effort of collecting old Bibles and glosses and establishing an authentic Latin source 2. a comparison of the versions 3. counselling “with old grammarians and old divines” about hard words and complex meanings 4. translating as clearly as possible the “sentence” (i. e. meaning), with the translation corrected by a group of collaborators 150 copies were produced, Knyghton the Chronicler said “the Gospel pearl is cast abroad, and trodden under feet of swine” “Give not that which is holy unto the dogs, neither cast ye your pearls before swine, lest they trample them under their feet, and turn again and rend you. ”(Mth, 7, 6)

John Purvey (c. 1354 – c. 1414) the four stages 1. a collaborative effort of collecting old Bibles and glosses and establishing an authentic Latin source 2. a comparison of the versions 3. counselling “with old grammarians and old divines” about hard words and complex meanings 4. translating as clearly as possible the “sentence” (i. e. meaning), with the translation corrected by a group of collaborators 150 copies were produced, Knyghton the Chronicler said “the Gospel pearl is cast abroad, and trodden under feet of swine” “Give not that which is holy unto the dogs, neither cast ye your pearls before swine, lest they trample them under their feet, and turn again and rend you. ”(Mth, 7, 6)

William Tyndale (1494 – 1536) an Oxford alumnus (ordained in 1519), lectured at Cambridge his translation plans thwarted by the Church he criticized the Church for, on the one hand, forbidding the laypeople to read the Bible in their language, but, paradoxically, accepting the use of vernacular for “histories and fables of love and wantonness and of ribaldry as filthy as heart can think, to corrupt the minds of youth…”

William Tyndale (1494 – 1536) an Oxford alumnus (ordained in 1519), lectured at Cambridge his translation plans thwarted by the Church he criticized the Church for, on the one hand, forbidding the laypeople to read the Bible in their language, but, paradoxically, accepting the use of vernacular for “histories and fables of love and wantonness and of ribaldry as filthy as heart can think, to corrupt the minds of youth…”

William Tyndale (ca. 1494 – 1536) in 1524 fled England (went to Germany, met Luther) and with the financial assistants of wealthy London merchants he translated the New Testament into English (he never returned to his homecountry) in 1525 translated New Testament from Greek and parts of Old Testament from the Hebrew, printed on the Continent, in Antwerp, smuggled to Britain (the printing press invented ca. 1440) in 1526 his Bible (pocket sized, easy to smuggle) was burnt publically (the only remaining copy is exhibited at the British Library), his Bible written in the language of ordinary people, not scholars (introduced words like “Passover”, “scapegoat”, “Jehovah”) in 1536 strangled and burnt at the stake in Flanders by agents of Charles V.

William Tyndale (ca. 1494 – 1536) in 1524 fled England (went to Germany, met Luther) and with the financial assistants of wealthy London merchants he translated the New Testament into English (he never returned to his homecountry) in 1525 translated New Testament from Greek and parts of Old Testament from the Hebrew, printed on the Continent, in Antwerp, smuggled to Britain (the printing press invented ca. 1440) in 1526 his Bible (pocket sized, easy to smuggle) was burnt publically (the only remaining copy is exhibited at the British Library), his Bible written in the language of ordinary people, not scholars (introduced words like “Passover”, “scapegoat”, “Jehovah”) in 1536 strangled and burnt at the stake in Flanders by agents of Charles V.

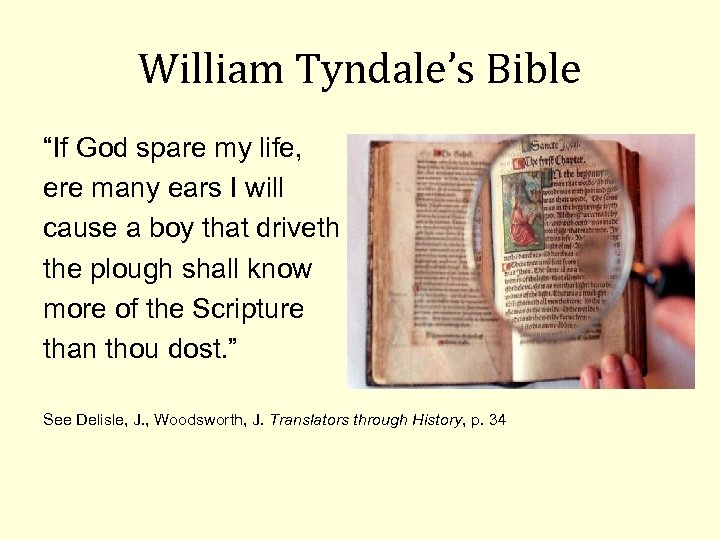

William Tyndale’s Bible “If God spare my life, ere many ears I will cause a boy that driveth the plough shall know more of the Scripture than thou dost. ” See Delisle, J. , Woodsworth, J. Translators through History, p. 34

William Tyndale’s Bible “If God spare my life, ere many ears I will cause a boy that driveth the plough shall know more of the Scripture than thou dost. ” See Delisle, J. , Woodsworth, J. Translators through History, p. 34

Miles Coverdale (1488 1569) 1535 he completed Tyndale’s version it was the base of the Great Bible (1539) also banned (also by Henry VIII. ) but the tide could not be stopped

Miles Coverdale (1488 1569) 1535 he completed Tyndale’s version it was the base of the Great Bible (1539) also banned (also by Henry VIII. ) but the tide could not be stopped

Other notable versions of the English Bible The Geneva Bible, most scholarly Protestant English Bible, diffused in England after Elizabeth came to the throne – with polemical marginal notes, Elizabeth I. (1533 – 1603), ordered a revision, the revised version is called the Bishop’s Bible, read in the churches, a huge format Catholics felt threatened so they prompted their own version to counter the Protestant readings a glosses, their version is known as Douay Rheims Bible, the New Testament in 1582, by 1610 the full text with commentaries published (including the apocrypha, e. g. The Book of Judith)

Other notable versions of the English Bible The Geneva Bible, most scholarly Protestant English Bible, diffused in England after Elizabeth came to the throne – with polemical marginal notes, Elizabeth I. (1533 – 1603), ordered a revision, the revised version is called the Bishop’s Bible, read in the churches, a huge format Catholics felt threatened so they prompted their own version to counter the Protestant readings a glosses, their version is known as Douay Rheims Bible, the New Testament in 1582, by 1610 the full text with commentaries published (including the apocrypha, e. g. The Book of Judith)

Authorized King James Version - 1611

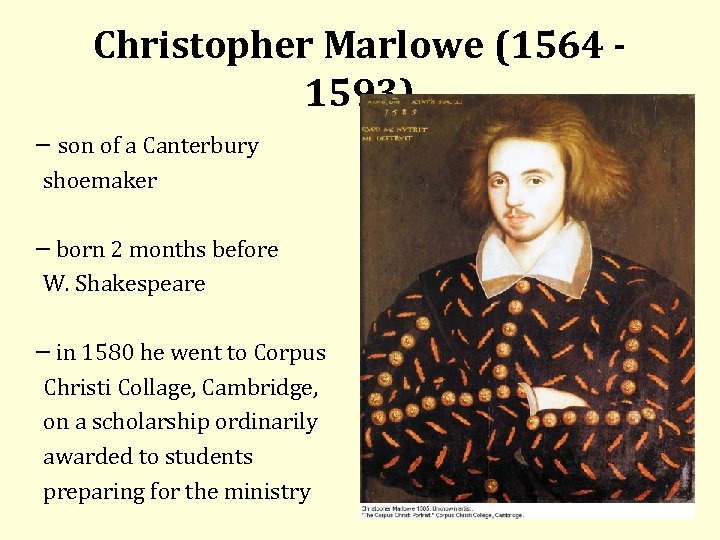

Authorized King James Version - 1611