b73ec4c99866c5b6956eba3a0c6629eb.ppt

- Количество слайдов: 93

Sovereign debt and sovereign default: Theory and Reality Ugo Panizza These are my own views

Bertrand Russell • If a man is offered a fact which goes against his instincts, he will scrutinize it closely, and unless the evidence is overwhelming, he will refuse to believe it. If, on the other hand, he is offered something which affords a reason for acting in accordance to his instincts, he will accept it even on the slightest evidence. The origin of myths is explained in this way. • In all affairs it's a healthy thing now and then to hang a question mark on the things you have long taken for granted • The most savage controversies are those about matters as to which there is no good evidence either way • I would never die for my beliefs because I might be wrong

The standard view • Facts – Countries get into debt problems because of lax fiscal policies – Countries have an incentive to default on their external debt obligations • Policies – Debt crises should always be followed by a fiscal retrenchment – We need to implement policies that reduce a country's incentive to default

Background • U. Panizza, F. Sturzenegger, and J. Zettelmeyer (2009) "The Economics and Law of Sovereign Debt and Sovereign Default" Journal of Economic Literature • B. Eichengreen, R. Hausmann, and U. Panizza (2003) “The Pain of Original Sin” University of Chicago Press • E. Borensztein, and U. Panizza (2009)"The Costs of Sovereign Default" IMF Staff Papers • E. Levy Yeyati and U. Panizza (2010) "The Elusive Cost of Sovereign Default, " Journal of Development Economics • E. Borensztein, E. Levy Yeyati, and U. Panizza (2006) Living with Debt, Harvard University Press and IDB • C. Campos, D. Jaimovich, and U. Panizza (2006) “The Unexplained Part of Public Debt, ” Emerging Markets Review • U. Panizza and A. Presbitero (2012) "Public Debt and Economic Growth: Is There a Causal Effect? , " Mo. Fi. R. Working Papers 65.

Outline • Facts – How debt grows – When do countries borrow and default • Policies – What to do during debt crises – How to deal with defaults

Debt and Politics in Tranquil Times • Politics and deficit (debt) bias – Because of excessive optimism • Not enough savings in good times – Remember the official reason for Greenspan’s support of tax cuts during the Bush administration – Because issuing debt allows to postpone difficult decisions – Because of strategic considerations • Why would Ronald Reagan run a large budget deficit?

Solutions • Budgetary institutions – Smart budgetary rules – Transparency rules – Hierarchical rules • Like motherhood and apple pie, these are great things…

…but they may not be enough • The relationship between deficit and debt is not as tight as you may think • Low debt is not enough

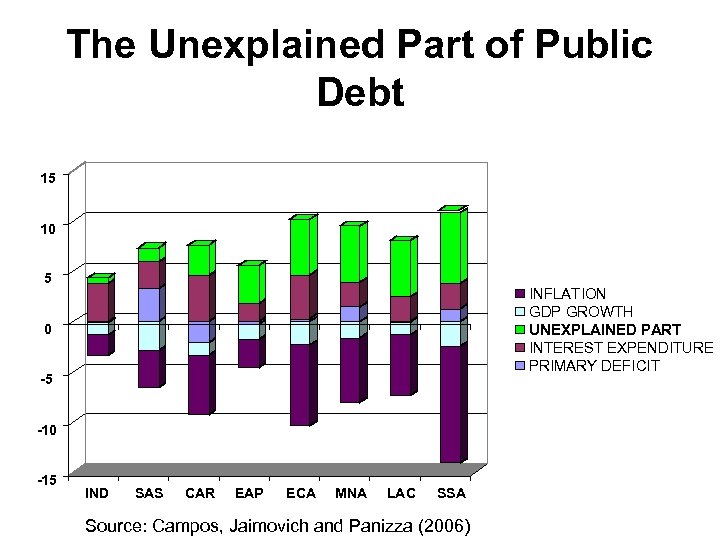

How Debt Grows? • The economics 101 debt accumulation equation states that: – CHANGE IN DEBT = DEFICIT • Practitioners use: – CHANGE IN DEBT = DEFICIT+SF – SF=Stock-flow reconciliation, or the unexplained part of public debt • The stock-flow reconciliation is often considered a residual entity of small importance • Is it?

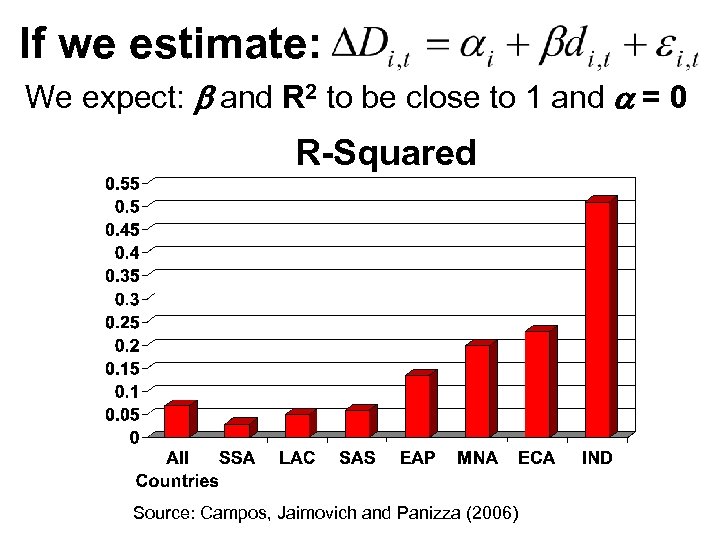

If we estimate: We expect: b and R 2 to be close to 1 and a = 0 R-Squared Source: Campos, Jaimovich and Panizza (2006)

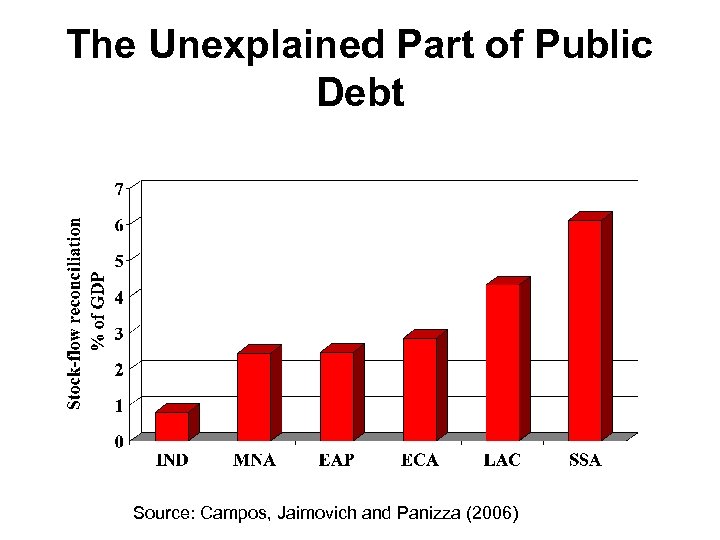

The Unexplained Part of Public Debt Source: Campos, Jaimovich and Panizza (2006)

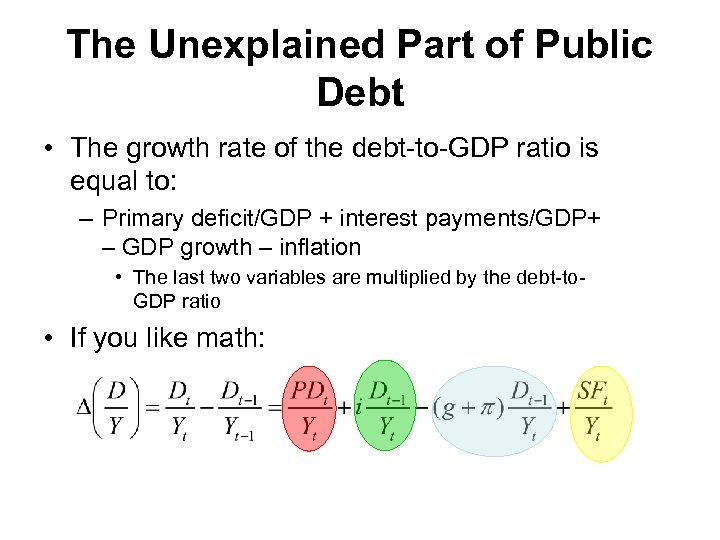

The Unexplained Part of Public Debt • The growth rate of the debt-to-GDP ratio is equal to: – Primary deficit/GDP + interest payments/GDP+ – GDP growth – inflation • The last two variables are multiplied by the debt-to. GDP ratio • If you like math:

The Unexplained Part of Public Debt 15 10 5 INFLATION GDP GROWTH UNEXPLAINED PART INTEREST EXPENDITURE PRIMARY DEFICIT 0 -5 -10 -15 IND SAS CAR EAP ECA MNA LAC SSA Source: Campos, Jaimovich and Panizza (2006)

The Unexplained Part of Public Debt • What explains the “Unexplained” part of debt – Skeletons • Fiscal policy matters! • Transparent fiscal accounts are important – Banking Crises – Balance Sheet Effects due to debt composition Much more about this in a while

The Unexplained Part of Public Debt • There also things that we can explain but may not have anything to do with fiscal policy – Output collapses – Sudden jumps in borrowing costs – Natural disasters

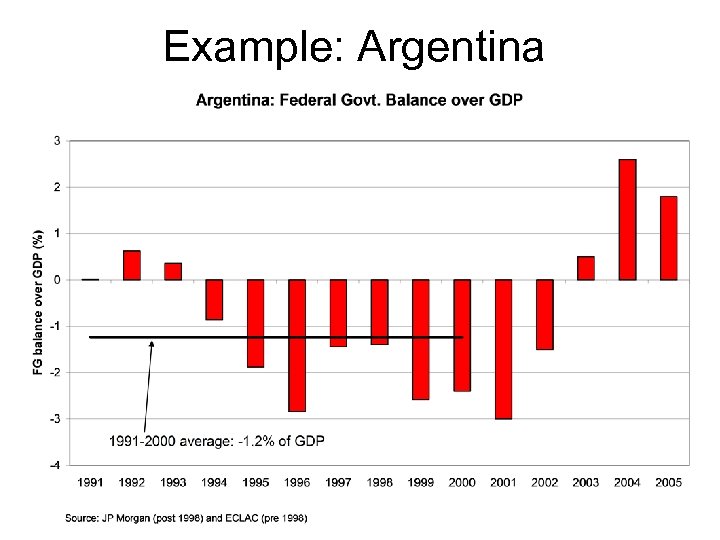

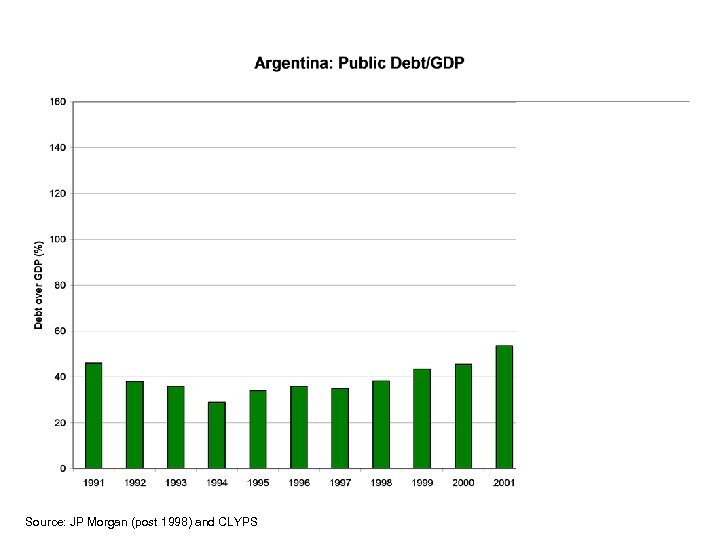

Example: Argentina

Source: JP Morgan (post 1998) and CLYPS

Incidentally

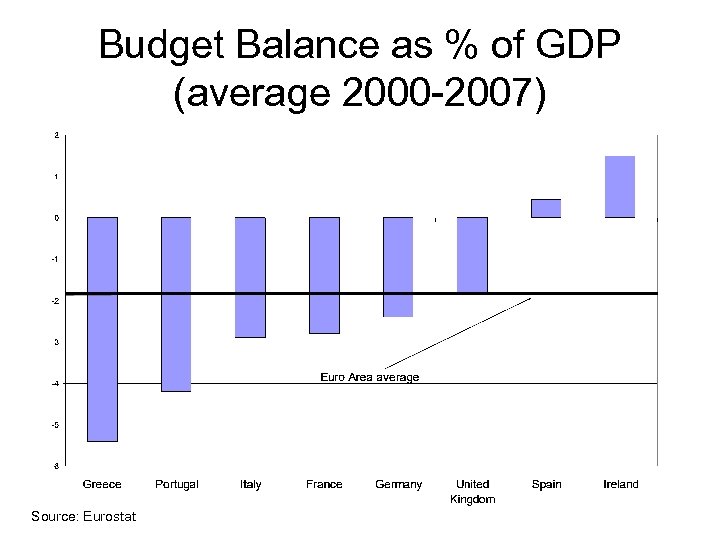

Budget Balance as % of GDP (average 2000 -2007) Source: Eurostat

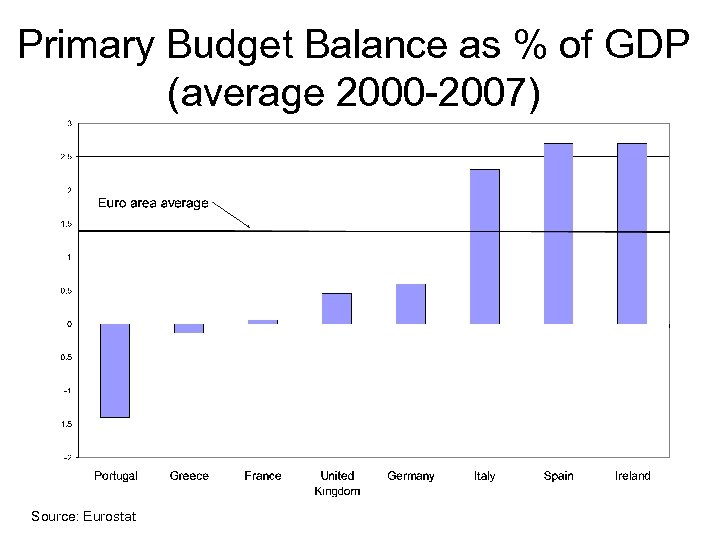

Primary Budget Balance as % of GDP (average 2000 -2007) Source: Eurostat

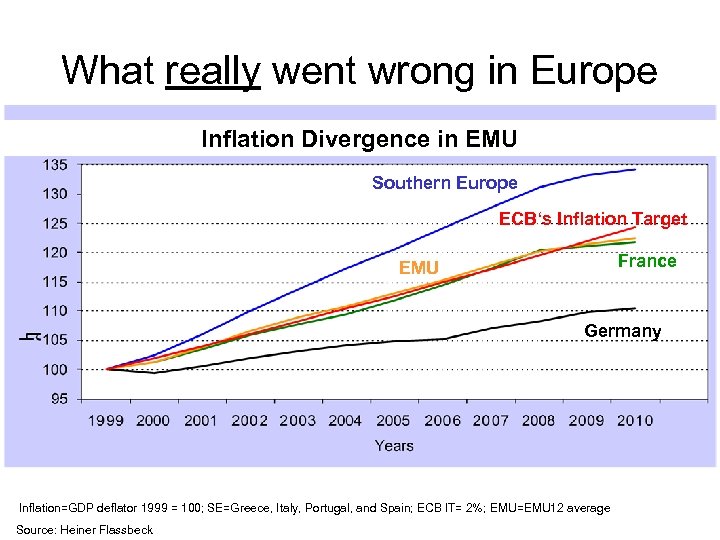

What really went wrong in Europe Inflation Divergence in EMU Southern Europe ECB‘s Inflation Target France EMU Germany Inflation=GDP deflator 1999 = 100; SE=Greece, Italy, Portugal, and Spain; ECB IT= 2%; EMU=EMU 12 average Source: Heiner Flassbeck

So, how debt grows? • IMF? –Its Mostly Fiscal • or • INAF –It’s Not Always Fiscal

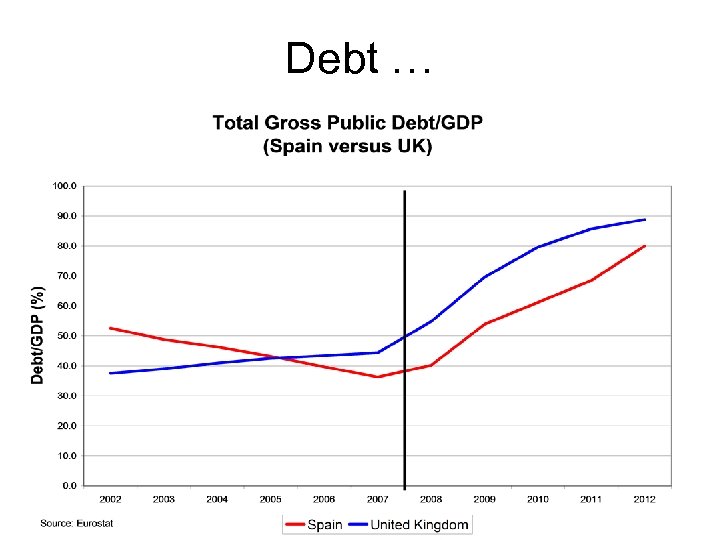

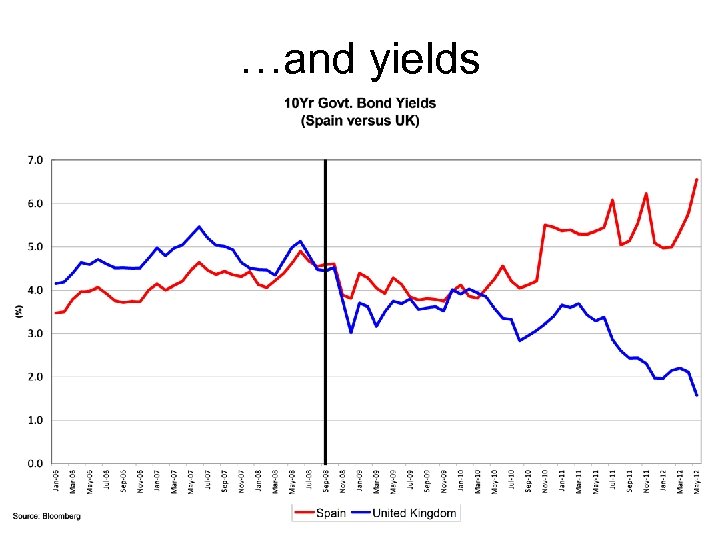

… but they may not be enough • The relationship between deficit and debt is not as tight as you may think • Low debt is not enough – Example: UK versus Spain – (with thanks to Paul De Grauwe)

Low debt can’t buy you love

Debt …

…and yields

The importance of debt structure • Debt denominated in foreign currency or short-maturity debt is associated with: – Lower Credit Ratings – Sudden Stops – Higher volatility – Limited ability of conducting monetary policy – Contractionary devaluations • An appropriate debt structure can reduce risk

How to make debt safer • New and safer instruments – Local currency – Contingent debt instruments • GDP index bonds • Commodity linked bonds • Catastrophe bonds • Dedollarize official lending

Why do we need official intervention? • Market failures – Critical mass – Standards – Instruments cannot be patented • Political economy – Shortsighted politicians may underinsure

Outline • Facts – How debt grows – When do countries borrow and default • Policies – What to do during debt crises – How to deal with defaults

Why is sovereign debt special? • Creditor rights are not as well defined for sovereign debt as is the case for private debts. • If a private firm becomes insolvent, creditors have a claim on the company’s assets. • In the case of a sovereign debt, in contrast, the legal recourse available to creditors has limited applicability and uncertain effectiveness. – Sovereign immunity – Little to attach • So, why do countries repay and why do lenders lend?

Theory

The Economic Theory of Sovereign Debt • The literature started with (and it's still tied to) an influential theoretical paper by Eaton and Gersovitz (Review of Economic Studies, 1981) • The story of the paper was: – Countries borrow in bad times (low economic growth) and repay in good times (high economic growth) – Since there are no repayments in bad times, there cannot be defaults either – As a consequence, defaults can only happen in good times – Defaults are thus strategic (countries can pay but they decide not to pay) – The only reason that prevents countries from defaulting is that defaults are costly

The Economic Theory of Sovereign Debt • So, what are the costs of default? – The traditional economic literature has emphasized – Reputational costs • Countries that default will no longer be able to access the international capital market – Trade costs • Default will lead to sanctions which, in turn, will have a negative effect on trade

From theory to the data In theory, there is no difference between theory and practice. In practice, there is

Do countries borrow in bad times?

What he really said: What do the data say? "Why did I rob banks? Because I enjoyed it. I loved it. I was more alive when I was inside a bank, robbing it, than at any other time in my life. I enjoyed everything about it so much that one or two weeks later I'd be out looking for the next job. But to me the money was the chips, that's all. " • Government external borrowing is procyclical and not countercyclical (probably because countries borrow when they can) • This confirms the idea that the seeds of debt crises are planted during good times

Do countries default in good times?

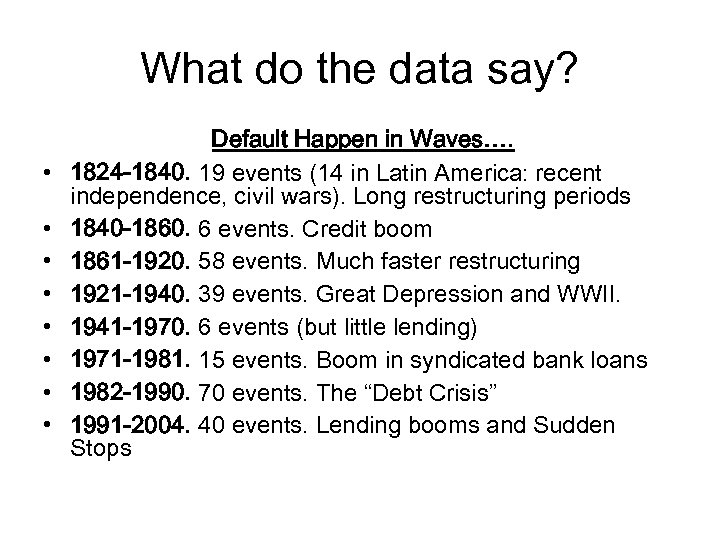

What do the data say? • • Default Happen in Waves…. 1824 -1840. 19 events (14 in Latin America: recent independence, civil wars). Long restructuring periods 1840 -1860. 6 events. Credit boom 1861 -1920. 58 events. Much faster restructuring 1921 -1940. 39 events. Great Depression and WWII. 1941 -1970. 6 events (but little lending) 1971 -1981. 15 events. Boom in syndicated bank loans 1982 -1990. 70 events. The “Debt Crisis” 1991 -2004. 40 events. Lending booms and Sudden Stops

Do defaulter pay a high cost?

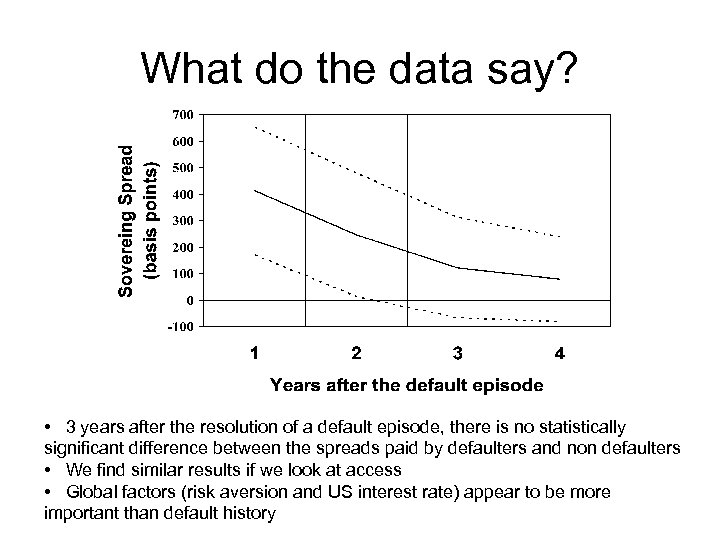

What do the data say? • 3 years after the resolution of a default episode, there is no statistically significant difference between the spreads paid by defaulters and non defaulters • We find similar results if we look at access • Global factors (risk aversion and US interest rate) appear to be more important than default history

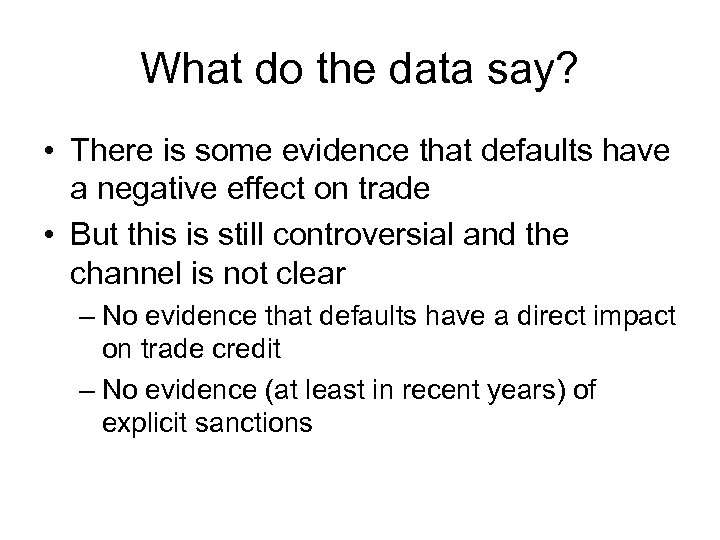

What do the data say? • There is some evidence that defaults have a negative effect on trade • But this is still controversial and the channel is not clear – No evidence that defaults have a direct impact on trade credit – No evidence (at least in recent years) of explicit sanctions

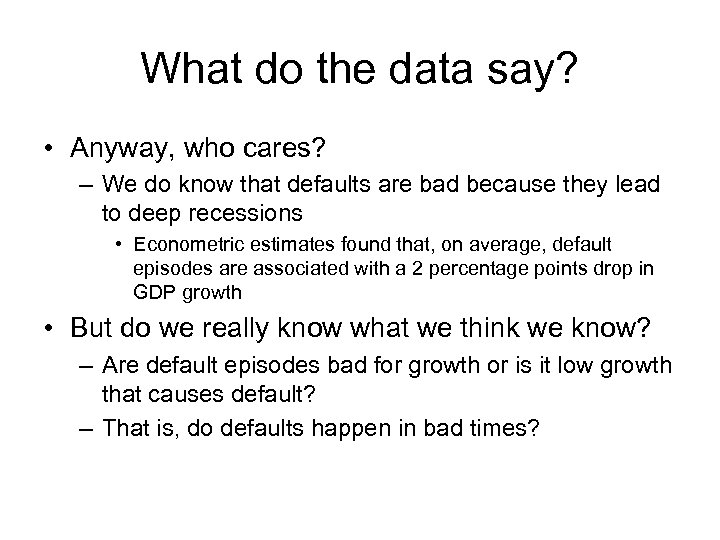

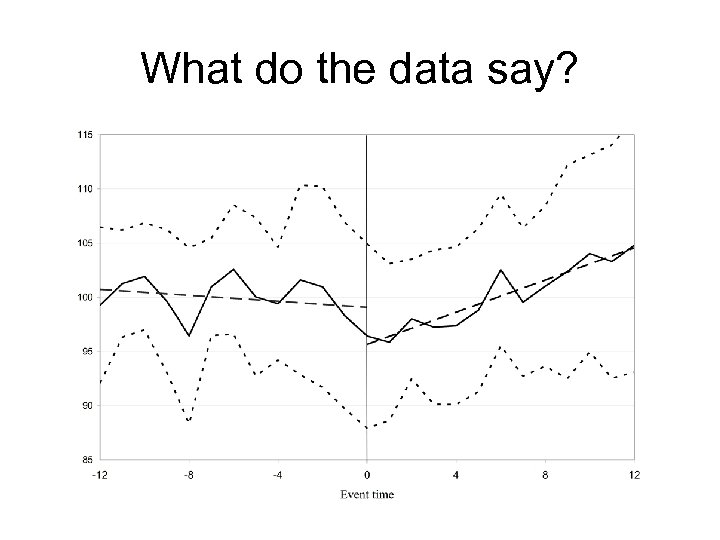

What do the data say? • Anyway, who cares? – We do know that defaults are bad because they lead to deep recessions • Econometric estimates found that, on average, default episodes are associated with a 2 percentage points drop in GDP growth • But do we really know what we think we know? – Are default episodes bad for growth or is it low growth that causes default? – That is, do defaults happen in bad times?

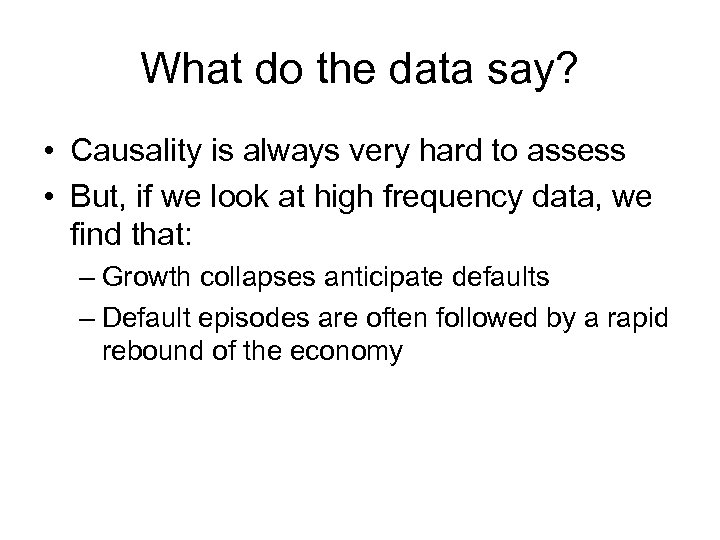

What do the data say? • Causality is always very hard to assess • But, if we look at high frequency data, we find that: – Growth collapses anticipate defaults – Default episodes are often followed by a rapid rebound of the economy

What do the data say?

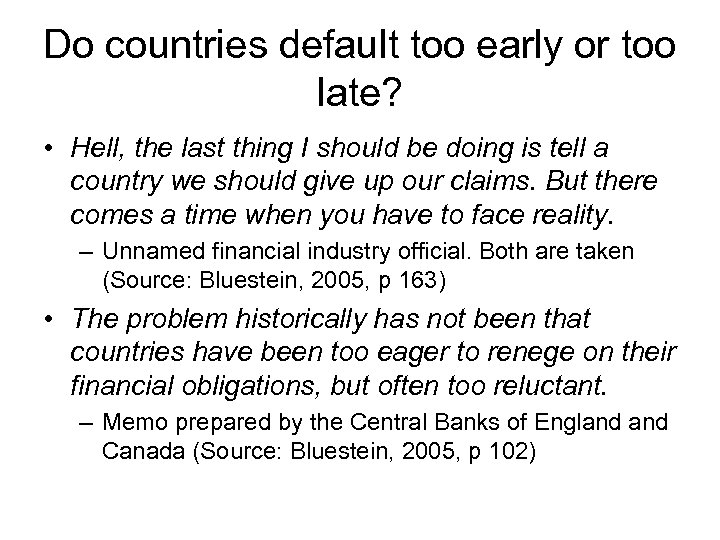

Do countries default too early or too late? • Hell, the last thing I should be doing is tell a country we should give up our claims. But there comes a time when you have to face reality. – Unnamed financial industry official. Both are taken (Source: Bluestein, 2005, p 163) • The problem historically has not been that countries have been too eager to renege on their financial obligations, but often too reluctant. – Memo prepared by the Central Banks of England Canada (Source: Bluestein, 2005, p 102)

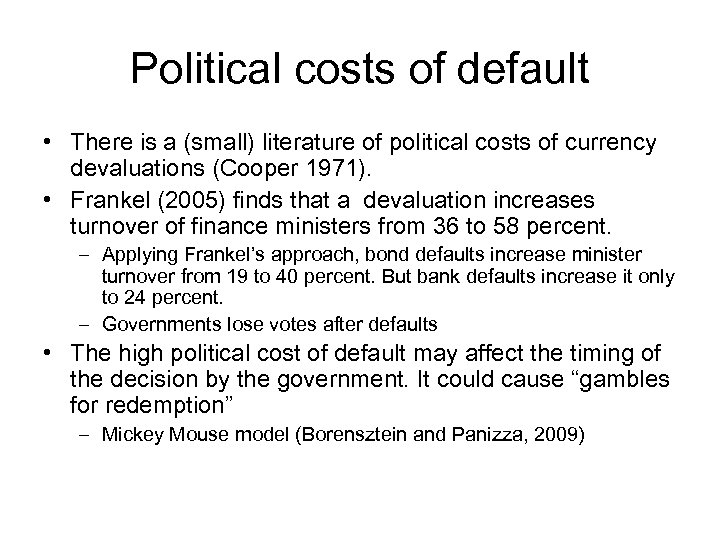

Political costs of default • There is a (small) literature of political costs of currency devaluations (Cooper 1971). • Frankel (2005) finds that a devaluation increases turnover of finance ministers from 36 to 58 percent. – Applying Frankel’s approach, bond defaults increase minister turnover from 19 to 40 percent. But bank defaults increase it only to 24 percent. – Governments lose votes after defaults • The high political cost of default may affect the timing of the decision by the government. It could cause “gambles for redemption” – Mickey Mouse model (Borensztein and Panizza, 2009)

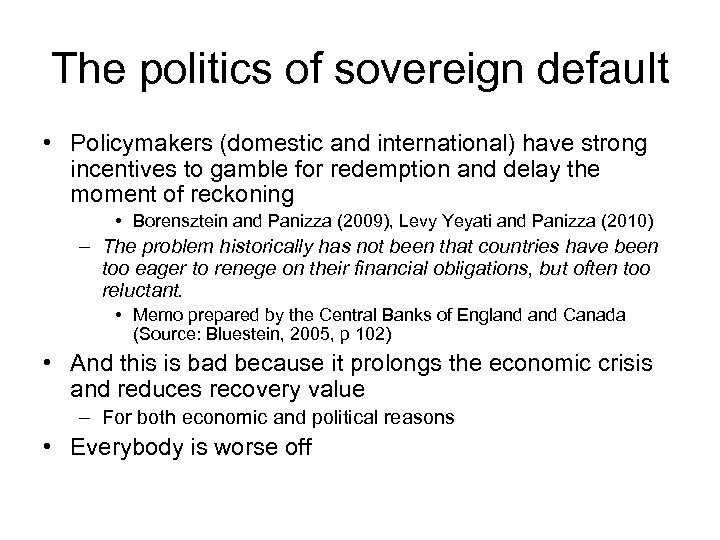

The politics of sovereign default • Policymakers (domestic and international) have strong incentives to gamble for redemption and delay the moment of reckoning • Borensztein and Panizza (2009), Levy Yeyati and Panizza (2010) – The problem historically has not been that countries have been too eager to renege on their financial obligations, but often too reluctant. • Memo prepared by the Central Banks of England Canada (Source: Bluestein, 2005, p 102) • And this is bad because it prolongs the economic crisis and reduces recovery value – For both economic and political reasons • Everybody is worse off

Summing up: Theory versus Reality • Theory – Countries get into trouble because of lax fiscal policy – Countries borrow in bad times – If ever, countries default in good times (strategic defaults) • So, if anything, they default too much – Defaults are very bad for the economy, with long lasting negative consequences • Reality – Many debt explosions have nothing to do with fiscal policy – Countries borrow in good times – Countries default in bad times (justified defaults) • And sometimes too late – Defaults do not seem to have long lasting negative consequences

Outline • Facts – How debt grows – When do countries borrow and default • Policies – What to do during debt crises – How to deal with defaults

The politics of crisis packages • Packages often come with: – Requests for fiscal consolidation – Not “too much” money – Interest rates which are above the opportunity cost of funds • Does this approach make sense from an economic point of view? • I will argue that it does not

Fiscal consolidation • Rationale (1) – They need to put their house in order • But… – Was the crisis caused by fiscal misbehavior? • We saw that in many cases, fiscal policy was not the problem

Fiscal consolidation • Standard answer: – Yes, but now the debt is high and things have changed! – Think about the math: Dd=-ps+(i-g)d • Assume LT growth 2% and LT interest rate 3%. Then, if debt increases by 50% of GDP, ps needs to increase by 0. 5% of GDP – Also, multiple equilibria (high i and low i) • Should "bailouts" have punitive interest rates? – More on this in a minute

Fiscal consolidation • Moreover – Even when the source of the problem was fiscal misbehavior, sustainable fiscal policy is a long-term concept – Short-term restrictive policies may be counterproductive because • They may worsen the crisis • They may be reversed as soon as the situation improves and the country no longer needs international assistance – Success requires addressing the political distortions that led to the unsustainable long-term policy stance

The dark side of the fiscal adjustment The adjustment variable is often public investment

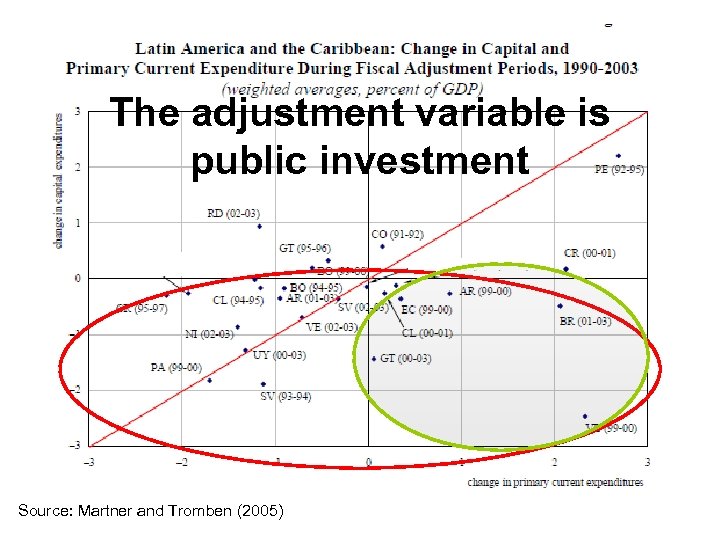

The adjustment variable is public investment Source: Martner and Tromben (2005)

…and this is very bad for growth, and for the fiscal adjustment When growth-promoting spending is cut so much that the present value of future government revenues falls by more than the immediate improvement in the cash deficit, fiscal adjustment becomes like walking up the down escalator. (Easterly, Irwin, Serven, 2008)

Fiscal consolidation • Rationale (2) – High public debt is bad for growth • But… – No evidence on the causal effect of public debt on growth

Excursus on debt and Growth in LIC, MIC, and HIC What the Heck!

Which debt? • Total external debt – Public and private • External public debt • Total public debt – External and domestic • What is external debt? – Panizza (2008)

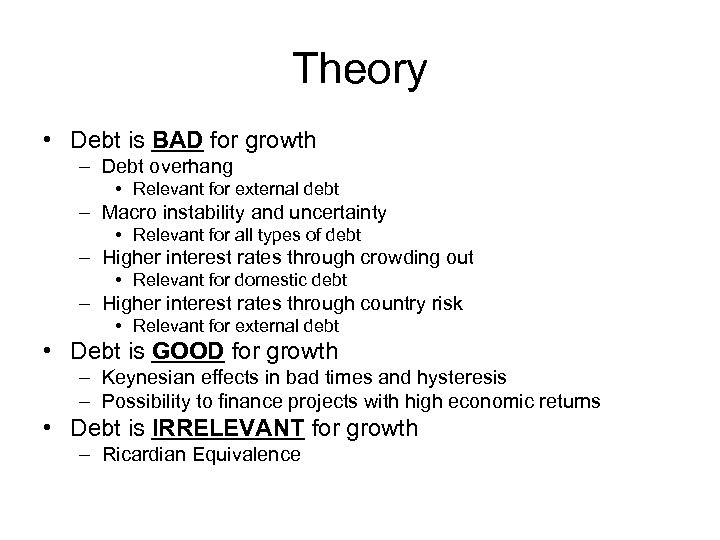

Theory • Debt is BAD for growth – Debt overhang • Relevant for external debt – Macro instability and uncertainty • Relevant for all types of debt – Higher interest rates through crowding out • Relevant for domestic debt – Higher interest rates through country risk • Relevant for external debt • Debt is GOOD for growth – Keynesian effects in bad times and hysteresis – Possibility to finance projects with high economic returns • Debt is IRRELEVANT for growth – Ricardian Equivalence

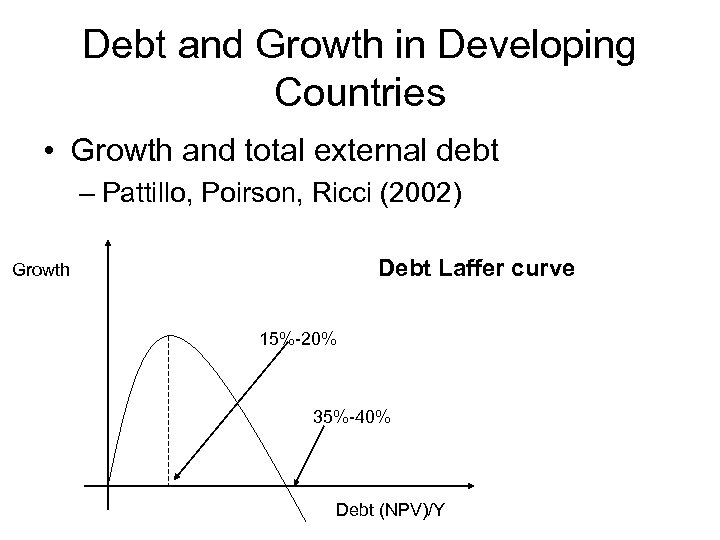

Debt and Growth in Developing Countries • Growth and total external debt – Pattillo, Poirson, Ricci (2002) Debt Laffer curve Growth 15%-20% 35%-40% Debt (NPV)/Y

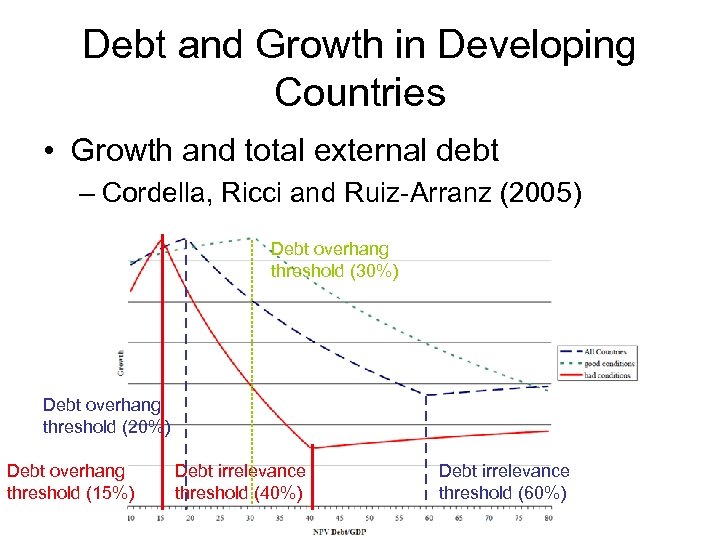

Debt and Growth in Developing Countries • Growth and total external debt – Cordella, Ricci and Ruiz-Arranz (2005) Debt overhang threshold (30%) Debt overhang threshold (20%) Debt overhang threshold (15%) Debt irrelevance threshold (40%) Debt irrelevance threshold (60%)

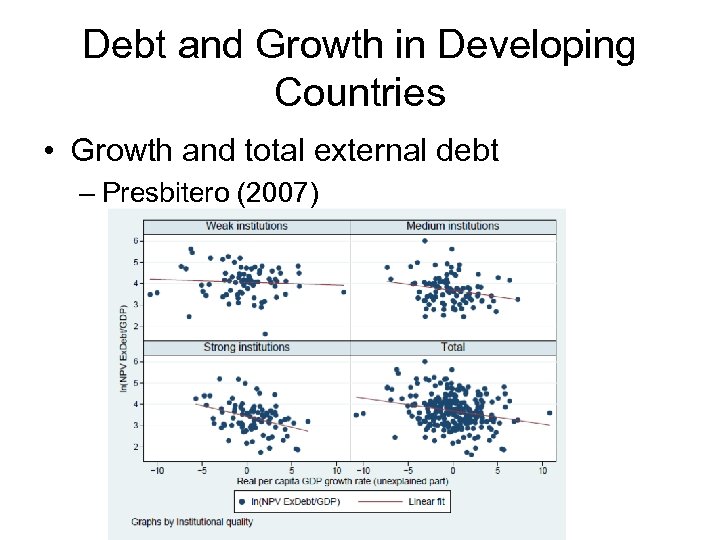

Debt and Growth in Developing Countries • Growth and total external debt – Presbitero (2007)

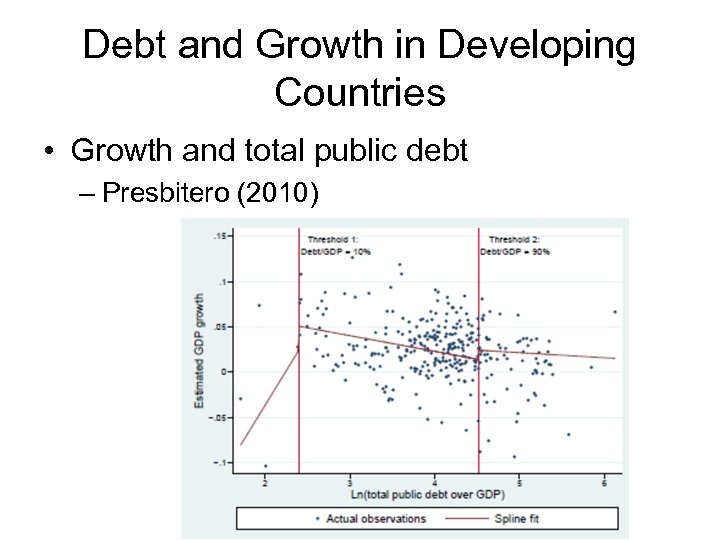

Debt and Growth in Developing Countries • Growth and total public debt – Presbitero (2010)

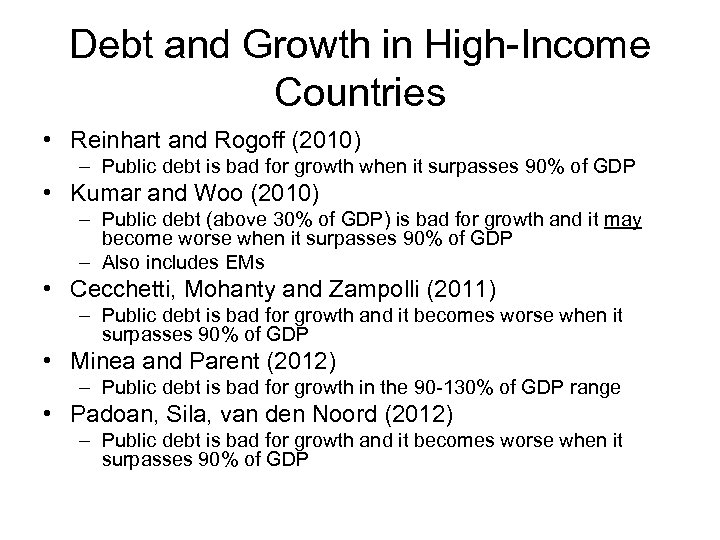

Debt and Growth in High-Income Countries • Reinhart and Rogoff (2010) – Public debt is bad for growth when it surpasses 90% of GDP • Kumar and Woo (2010) – Public debt (above 30% of GDP) is bad for growth and it may become worse when it surpasses 90% of GDP – Also includes EMs • Cecchetti, Mohanty and Zampolli (2011) – Public debt is bad for growth and it becomes worse when it surpasses 90% of GDP • Minea and Parent (2012) – Public debt is bad for growth in the 90 -130% of GDP range • Padoan, Sila, van den Noord (2012) – Public debt is bad for growth and it becomes worse when it surpasses 90% of GDP

Growth Implosions, Debt Explosions, and My Aunt Marylin: Do Growth Slowdonws Cause Public Debt Crises? William Easterly (2001)

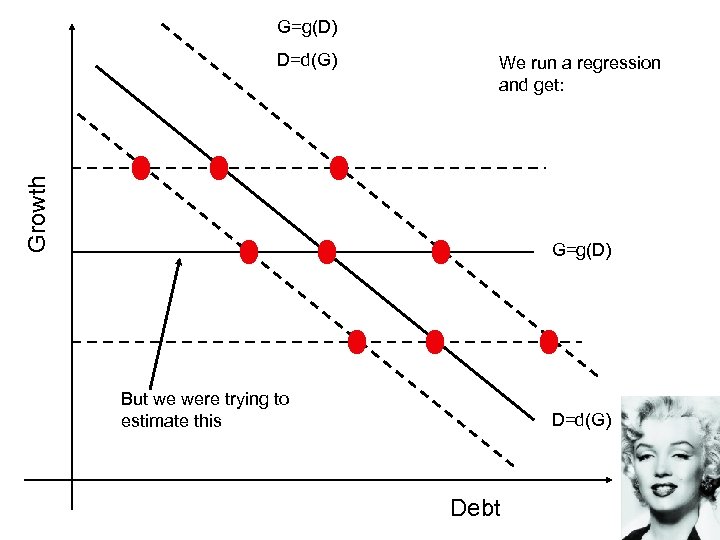

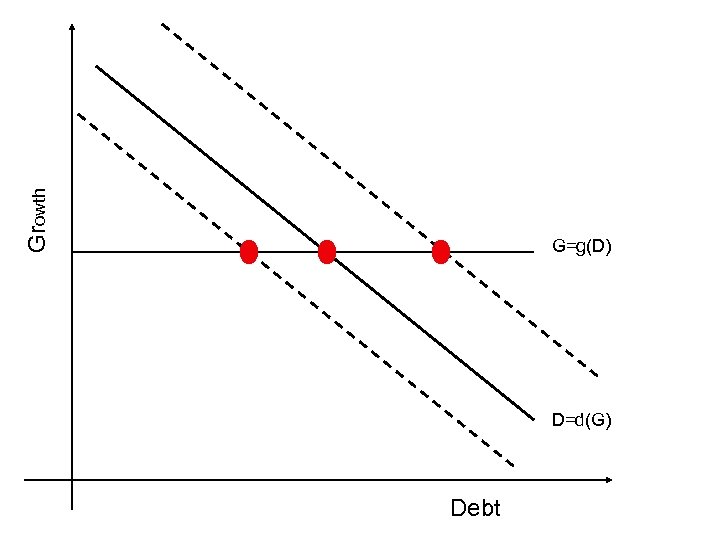

Causality • Why are there so many sick people in hospitals? • Debt has an effect on growth: G=g(D) • Growth has an effect on debt: D=d(G)

G=g(D) We run a regression and get: Growth D=d(G) G=g(D) But we were trying to estimate this D=d(G) Debt

Growth G=g(D) D=d(G) Debt

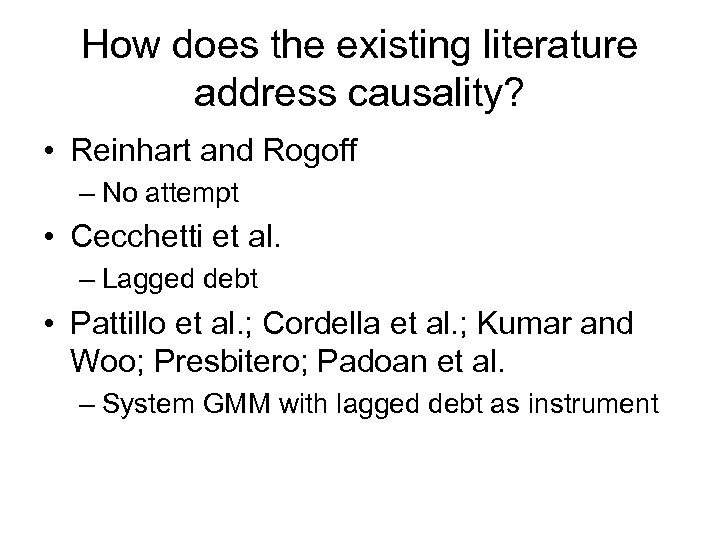

How does the existing literature address causality? • Reinhart and Rogoff – No attempt • Cecchetti et al. – Lagged debt • Pattillo et al. ; Cordella et al. ; Kumar and Woo; Presbitero; Padoan et al. – System GMM with lagged debt as instrument

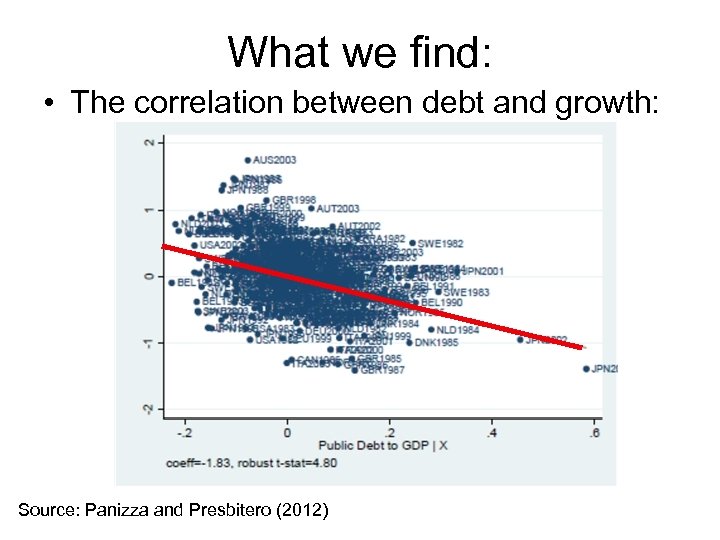

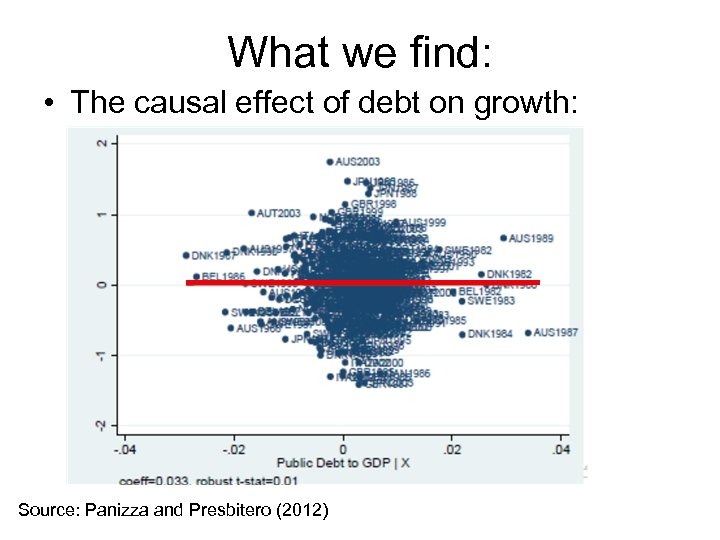

What we find: • The correlation between debt and growth: Source: Panizza and Presbitero (2012)

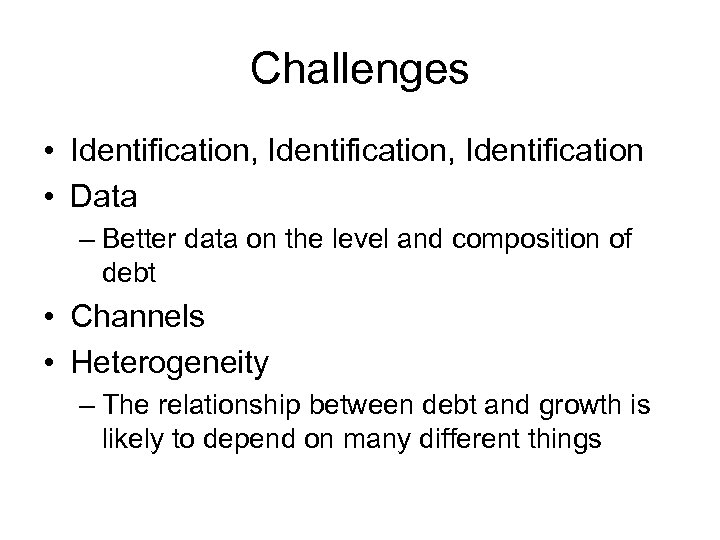

What we find: • The causal effect of debt on growth: Source: Panizza and Presbitero (2012)

Challenges • Identification, Identification • Data – Better data on the level and composition of debt • Channels • Heterogeneity – The relationship between debt and growth is likely to depend on many different things

Some conclusions • Donald Rumsfeld – There are knowns • Things we know that we know – There are known unknowns • Things that we now know we don't know – There also unknowns • Things we do not know, we don't know • Mark Twain – It ain't what you don't know that gets you into trouble. It's what you know for sure that just ain't so

Some conclusions • Known knowns – There is a negative correlation between debts and growth – Debt has a causal negative effect on growth – This negative effect becomes especially important when the debtto-GDP ratio reaches a certain threshold • 90% in advanced economies • 15 -40% in developing countries • Known unknowns – Is there a negative effect of debt and growth? – The threshold • Unknown unknowns • Bertrand Russell – The whole problem with the world is that fools and fanatics are always so certain of themselves, but wiser people are so full of doubts

end of excursus on debt and growth

Interest rates above opportunity cost and not “too much” money • Rationale (1) – Need to protect our own taxpayers • But… – The smaller the size of the package and the higher the interest rate, the less likely the success of the package • (higher risk for the taxpayer)

Interest rates above opportunity cost and not “too much” money • Rationale (2) – Avoid moral hazard • But… – Do you really believe that politicians are so farsighted? – Bagehot was right for banking crises, but he may be wrong for sovereign debt crises – Moral hazard is often overstated (Meltzer versus Krugman)

Why do we observe actions that go against economic logic? • Wrong economic model – Some countries and economists still live in the shadow of the Treasury view • Politics – In this case, not politics in the crisis country, but politics in the “strong” countries – Electors want a pound of flesh

What can the international community do? • Don’t ask for fiscal contractions if fiscal profligacy was not the problem • If a fiscal contractions is needed, don’t frontload it (Blanchard and Cottarelli, 2010) • Think about fiscal targets that protect investment (Blanchard and Giavazzi, 2004, Buiter, 198? ) • Also think about the quality of public investment (Pritchett, 2000, Dabla-Norris et al. , 2011, )

Outline • Facts – How debt grows – When do countries borrow and default • Policies – What to do during debt crises – How to deal with defaults

From earlier this morning • Theory – Countries borrow in bad times – If ever, countries default in good times (strategic defaults) • So, if anything, they default too much – Defaults are very bad for the economy, with long lasting negative consequences • Reality – Countries borrow in good times – Countries default in bad times (justified defaults) • And sometimes too late – Defaults do not seem to have long lasting negative consequences

Pfuel. . had a science--the theory of oblique movements. . and all he came across in the history of more recent warfare seemed to him absurd. . so many blunders were committed … that these wars could not be called wars, they did not accord with the • Let me start by saying that I am material for science. theory, and therefore could not serve as not (I repeat To default or not to default? NOT) suggesting that countries should default more often In 1806 Pfuel had been … responsible, for the plan. . . that ended in Jena. . . but he did not see the is there this the fallibility of his • But I want to ask, why least proof of disconnect theorybetween theory and war. . Pfuel was one of those in the disasters of that reality? theoreticians who so love their theory that they lose sight of the • The theory might be wrong theory's object--its practical application. His love of theory made • Or, they may practical, and with the world him hate everything be a problemhe would not listen to it. He was even pleasedis that this for due to a mix offrom deviations • My hunch by failures, is failures resulting political in practice from thea von Phull international financial failure and theory only. Pfuel) (6 November 1757 accuracy of his Karl Ludwig lousy (or proved to him the – 25 April 1826) the service of theory. architecture was a German general in Empire. Phull the Kingdom of Prussia and the Russian War and served as Chief of the General Staff of King Frederick Peace, Book 9, chapter X of Jena-Auerstedt. William III of Prussia in the Battle

Is the world wrong? • In a well working system, countries should be able to borrow when they need funds (i. e. , in bad times) – But during bad times, the international capital markets are not willing to provide credit at a reasonable interest rate – Therefore, countries borrow in good times because this is when they have access to credit • Same reason why Willie Sutton robbed banks – Unfortunately, sometimes they borrow too much in good times and this behavior sows the seeds of future crises • We need to fix the political economy of debt – The real reason why Willie Sutton robbed banks

Strategic or justified? • Most of the defaults we observe are justified (or unavoidable, at least ex-post) episodes • Strategic defaults are very rare – So, we cannot use econometric methods to assess the cost of these very rare events – What we are actually assessing is the cost of non-strategic defaults • But why are they rare? • Probably because they are costly • But what is the cost?

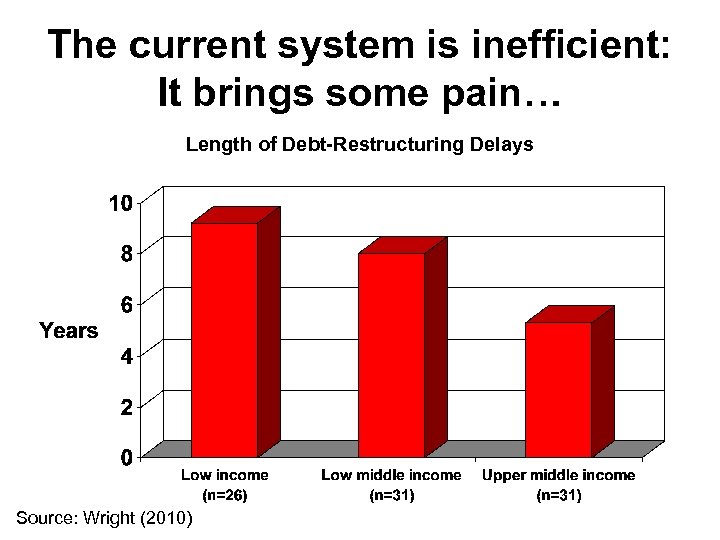

The current system is inefficient: It brings some pain… Length of Debt-Restructuring Delays Source: Wright (2010)

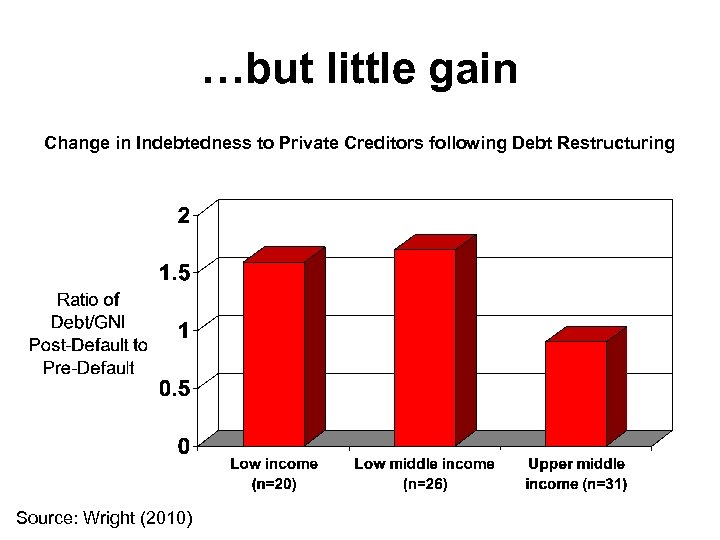

…but little gain Change in Indebtedness to Private Creditors following Debt Restructuring Source: Wright (2010)

Is this inefficient system efficient? • Some pain and no gain might be inefficient expost, but could be efficient ex-ante • High costs of defaults are necessary to create willingness to pay, establish credibility, and lower borrowing cost – Dooley (2000), Shleifer (2003) • This is why countries suboptimally delay default • This is why some borrowing countries are opposed to the creation of a mechanism that may eliminate these inefficiencies

From second best to first best • This is clearly a second best solution – Countries suffer – They destroy value and decrease recovery rates

From second best to first best • An alternative story – The international community and financial markets implicitly forgive countries that default out of necessity but would impose a harsh punishment on countries that default strategically (Grossman and van Huyk, AER 1988) – If this is the case, policymakers need to signal that the default is indeed unavoidable and not strategic – A way of doing this is to go through considerable pain in order to delay the default as long as possible • Also second best, but in this case there is a solution

From second best to first best • Solution: – The first best could be achieved with the creation of a body with the ability to assess whether a default was indeed unavoidable • A bankruptcy court for sovereigns • By increasing potential recovery rates, it could be efficient both ex-ante and ex-post • Everybody (lenders and borrowers) is better off

Sovereign debt and sovereign default: Theory and Reality Ugo Panizza These are my own views

b73ec4c99866c5b6956eba3a0c6629eb.ppt