lecture 3 lexicology.ppt

- Количество слайдов: 93

Сonnection of meaning and concept • Meaning is very closely connected with the underlying concept, but they are different: • - concept is a category of human cognition • - concepts are almost the same for the whole of humanity whereas the meanings are different in different languages • Words expressing identical concepts may have different meanings

Сonnection of meaning and concept • Meaning is very closely connected with the underlying concept, but they are different: • - concept is a category of human cognition • - concepts are almost the same for the whole of humanity whereas the meanings are different in different languages • Words expressing identical concepts may have different meanings

Сonnection of meaning and concept compare two English words house and home and a Russian word дом A home doesn’t have to be a house, it can be any place in the world. A home is a place you love, where you feel you belong and where you feel happy to be there.

Сonnection of meaning and concept compare two English words house and home and a Russian word дом A home doesn’t have to be a house, it can be any place in the world. A home is a place you love, where you feel you belong and where you feel happy to be there.

• A house is a building which accomodates you. It is just a building and you do not neccesarilly care about it. • It takes a lot of living in a house to turn it into a home.

• A house is a building which accomodates you. It is just a building and you do not neccesarilly care about it. • It takes a lot of living in a house to turn it into a home.

• Synonyms one concept but different meaning • Big and large • die, kick the bucket, to join the majority, to pass away, to check out (To settle one's bill and leave a hotel or other place of lodging) – выписаться • малышка, голопуз, отпрыск, сосун, малолетний, клоп, малолеток, малолетка, ребенок

• Synonyms one concept but different meaning • Big and large • die, kick the bucket, to join the majority, to pass away, to check out (To settle one's bill and leave a hotel or other place of lodging) – выписаться • малышка, голопуз, отпрыск, сосун, малолетний, клоп, малолеток, малолетка, ребенок

• Content of concept six can be presented differently • One+ five • Three plus three • Ten minus four • meaning of six is not identical with the meaning of these word groups. But the concept of six.

• Content of concept six can be presented differently • One+ five • Three plus three • Ten minus four • meaning of six is not identical with the meaning of these word groups. But the concept of six.

• meaning is linguistic the denoted object is extralinguistic. • One and the same object can be denoted by more than one word, e. g. apple

• meaning is linguistic the denoted object is extralinguistic. • One and the same object can be denoted by more than one word, e. g. apple

• Some equate meaning to the concept (they substitute meaning for concept) • Others identify meaning with the referent • Their point of view – unless we have a knowledge of the referent we cannot give a definition of a word • If salt is sodium chloride ( what is love, hate? )

• Some equate meaning to the concept (they substitute meaning for concept) • Others identify meaning with the referent • Their point of view – unless we have a knowledge of the referent we cannot give a definition of a word • If salt is sodium chloride ( what is love, hate? )

• We have just shown that meaning is closely connected by not identical with its soundform concept of referent. At the same time iven those who accept this view disagree as to the nature of meaning. • Some regard meaning as the interrelation of the three points of the triangle, but not as an objectively existing part of the linguistic sign

• We have just shown that meaning is closely connected by not identical with its soundform concept of referent. At the same time iven those who accept this view disagree as to the nature of meaning. • Some regard meaning as the interrelation of the three points of the triangle, but not as an objectively existing part of the linguistic sign

• In Russian linguistics there is a famous opinion given by Alexander Smirnitsky A certain reflection in our minds of objects, phenomena or relations that makes part of the linguistic sign – its so-called inner-facet, and the sound –form is its outer facet. Meaning is to be found in all linguistic units

• In Russian linguistics there is a famous opinion given by Alexander Smirnitsky A certain reflection in our minds of objects, phenomena or relations that makes part of the linguistic sign – its so-called inner-facet, and the sound –form is its outer facet. Meaning is to be found in all linguistic units

• Meaning and referent is not the same • 1 meaning is linguistic the denoted object or the referent is beyond the scope of language. • 2. We can denote one and the same object by more than one word of a different meaning. For instance, in a speech situation an apple can be denoted by different words • apple, fruit, something, this • the same referent in all of them

• Meaning and referent is not the same • 1 meaning is linguistic the denoted object or the referent is beyond the scope of language. • 2. We can denote one and the same object by more than one word of a different meaning. For instance, in a speech situation an apple can be denoted by different words • apple, fruit, something, this • the same referent in all of them

• Meaning is not the same with the actual properties of the referent, • e. g. the meaning of the word water cannot be regarded as identical with its chemical formula H 2 O water means essentially the same to all English speakers including those who have no idea of its chemical composition.

• Meaning is not the same with the actual properties of the referent, • e. g. the meaning of the word water cannot be regarded as identical with its chemical formula H 2 O water means essentially the same to all English speakers including those who have no idea of its chemical composition.

• There are words that have distinct meaning but do not refer to any existing thing, e. g. angel or phoenix. • Such words have meaning which is understood by the speaker-hearer but the objects they denote do not exist.

• There are words that have distinct meaning but do not refer to any existing thing, e. g. angel or phoenix. • Such words have meaning which is understood by the speaker-hearer but the objects they denote do not exist.

Meaning in RA • Some equate meaning to the concept (they substitute meaning for concept) • Others identify meaning with the referent • Their point of view – unless we have a knowledge of the referent we cannot give a definition of a wordunless we have a scientifically accurate knowledge of the referent we cannot give a scientifically accurate definition of the meaning of a word. • If salt is sodium chloride ( what is love, hate? )

Meaning in RA • Some equate meaning to the concept (they substitute meaning for concept) • Others identify meaning with the referent • Their point of view – unless we have a knowledge of the referent we cannot give a definition of a wordunless we have a scientifically accurate knowledge of the referent we cannot give a scientifically accurate definition of the meaning of a word. • If salt is sodium chloride ( what is love, hate? )

• We have just shown that meaning is closely connected by not identical with its soundform concept of referent. At the same time even those who accept this view disagree as to the nature of meaning. • Some regard meaning as the interrelation of the three points of the triangle, but not as an objectively existing part of the linguistic sign

• We have just shown that meaning is closely connected by not identical with its soundform concept of referent. At the same time even those who accept this view disagree as to the nature of meaning. • Some regard meaning as the interrelation of the three points of the triangle, but not as an objectively existing part of the linguistic sign

• In Russian linguistics there is a famous opinion given by Alexander Smirnitsky A certain reflection in our minds of objects, phenomena or relations that makes part of the linguistic sign – its so-called inner-facet, and the sound –form is its outer facet. Meaning is to be found in all linguistic units

• In Russian linguistics there is a famous opinion given by Alexander Smirnitsky A certain reflection in our minds of objects, phenomena or relations that makes part of the linguistic sign – its so-called inner-facet, and the sound –form is its outer facet. Meaning is to be found in all linguistic units

Types of meaning • • • 1. Grammatical meaning 1. 1. Denotational meaning 1. 2. Connotational meaning 1. 3. Emotive charge vs emotive implcation 2. Lexical meaning

Types of meaning • • • 1. Grammatical meaning 1. 1. Denotational meaning 1. 2. Connotational meaning 1. 3. Emotive charge vs emotive implcation 2. Lexical meaning

Types of meaning • Grammatical meaning the component of meaning recurrent in identical sets of individual forms of different words, the tense meaning in the word-forms of verbs (asked, thought, walked, etc. ) or the case meaning in the word-forms of various nouns (girl’s, boy’s, night’s, etc. ).

Types of meaning • Grammatical meaning the component of meaning recurrent in identical sets of individual forms of different words, the tense meaning in the word-forms of verbs (asked, thought, walked, etc. ) or the case meaning in the word-forms of various nouns (girl’s, boy’s, night’s, etc. ).

Types of meaning • lexical meaning is the meaning proper to the given linguistic unit in all its forms and distributions; • grammatical meaning is the meaning proper to sets of word-forms common to all words of a certain class.

Types of meaning • lexical meaning is the meaning proper to the given linguistic unit in all its forms and distributions; • grammatical meaning is the meaning proper to sets of word-forms common to all words of a certain class.

Denotational meaning • denotational meaning, i. e. that component of the lexical meaning which makes communication possible. • a physicist knows more about the atom than a singer does, but they use the words atom

Denotational meaning • denotational meaning, i. e. that component of the lexical meaning which makes communication possible. • a physicist knows more about the atom than a singer does, but they use the words atom

connotational component • The second component of the lexical meaning is the connotational component, i. e. the emotive charge and the stylistic value of the word. The emotive charge is one of the objective semantic features proper to words as linguistic units and forms part of the connotational component of meaning.

connotational component • The second component of the lexical meaning is the connotational component, i. e. the emotive charge and the stylistic value of the word. The emotive charge is one of the objective semantic features proper to words as linguistic units and forms part of the connotational component of meaning.

Emotive implication • It should not be confused with emotive implications that the words may acquire in speech. • The emotive implication of the word is to a great extent subjective as it greatly depends of the personal experience of the speaker, the mental imagery the word evokes in him.

Emotive implication • It should not be confused with emotive implications that the words may acquire in speech. • The emotive implication of the word is to a great extent subjective as it greatly depends of the personal experience of the speaker, the mental imagery the word evokes in him.

Stylistic reference • Words differ not only in their emotive charge but also in their stylistic reference. • From the stylistic point of view words can be roughly subdivided into three layers: • literary • Neutral • colloquial

Stylistic reference • Words differ not only in their emotive charge but also in their stylistic reference. • From the stylistic point of view words can be roughly subdivided into three layers: • literary • Neutral • colloquial

Stylistic classification • literаrу layer • words of general use • they possess no specific stylistic they are known as neutral words. • Against the background of neutral words two major subgroups • standard colloquial words and literary or bookish words.

Stylistic classification • literаrу layer • words of general use • they possess no specific stylistic they are known as neutral words. • Against the background of neutral words two major subgroups • standard colloquial words and literary or bookish words.

parent — father — dad’. the word father is stylistically neutral; dad stands out as colloquial parent is bookish. The stylistic reference of standard colloquial words is clearly seen if we compare them with their neutral synonyms: • chum — friend, rot — nonsense. • • •

parent — father — dad’. the word father is stylistically neutral; dad stands out as colloquial parent is bookish. The stylistic reference of standard colloquial words is clearly seen if we compare them with their neutral synonyms: • chum — friend, rot — nonsense. • • •

• The same is true with literary or bookish words: • to presume (cf. to suppose); • to anticipate (cf. to expect). • Literary (=bookish) words are not stylistically homogeneous. • Thus besides general-literary (bookish) words, e. g. harmony, calamity, alacrity, etc. , • we may single out various specific subgroups, namely:

• The same is true with literary or bookish words: • to presume (cf. to suppose); • to anticipate (cf. to expect). • Literary (=bookish) words are not stylistically homogeneous. • Thus besides general-literary (bookish) words, e. g. harmony, calamity, alacrity, etc. , • we may single out various specific subgroups, namely:

• 1) terms or scientific words: renaissance, genocide, computerize, computer programming. 2) poetic words and archaisms: whilome — ‘formerly’ aught — ‘anything’, ere — ‘before’, albeit — ‘although’, fare — ‘walk’, etc. , tarry — ‘remain’, nay — ‘no’

• 1) terms or scientific words: renaissance, genocide, computerize, computer programming. 2) poetic words and archaisms: whilome — ‘formerly’ aught — ‘anything’, ere — ‘before’, albeit — ‘although’, fare — ‘walk’, etc. , tarry — ‘remain’, nay — ‘no’

• • • Beforetime = formerly Belike = most likely; probably Betimes = in short time; speedily Betwixt = between Certes = in truth; certainly Verily = truly; certainly; confidently

• • • Beforetime = formerly Belike = most likely; probably Betimes = in short time; speedily Betwixt = between Certes = in truth; certainly Verily = truly; certainly; confidently

• 3) barbarisms and foreign words. are words of foreign origin which have not entirely been assimilated into the English language: bon mot — ‘a clever or witty saying’; • chic (=stylish); • en passant (= in passing) • apropos = by the way; incidentally • faux pas = a socially awkward or tactless act

• 3) barbarisms and foreign words. are words of foreign origin which have not entirely been assimilated into the English language: bon mot — ‘a clever or witty saying’; • chic (=stylish); • en passant (= in passing) • apropos = by the way; incidentally • faux pas = a socially awkward or tactless act

• The colloquial words may be subdivided into: • 1. Common colloquial words. • 2. Slang words often regarded as a violation of the norms of Standard English • governor for ‘father’ • missus for ‘wife’ • gag for ‘a joke’ • dotty for ‘insane’.

• The colloquial words may be subdivided into: • 1. Common colloquial words. • 2. Slang words often regarded as a violation of the norms of Standard English • governor for ‘father’ • missus for ‘wife’ • gag for ‘a joke’ • dotty for ‘insane’.

• 3. Professionalisms, i. e. words used in narrow groups bound by the same occupation, such as, e. g. , lab for ‘laboratory’, math for mathematics • a buster for ‘a bomb’ • 4. Jargonisms, i. e. words marked by their use within a particular social group and bearing a secret and cryptic character, e. g. a sucker — ‘a person who is easily deceived’, a squiffer — ‘a concertina’.

• 3. Professionalisms, i. e. words used in narrow groups bound by the same occupation, such as, e. g. , lab for ‘laboratory’, math for mathematics • a buster for ‘a bomb’ • 4. Jargonisms, i. e. words marked by their use within a particular social group and bearing a secret and cryptic character, e. g. a sucker — ‘a person who is easily deceived’, a squiffer — ‘a concertina’.

• 5. Vulgarisms, i. e. coarse words that are not generally used in public, e. g. • bloody, hell, damn, shut up. • 6. Dialectical words • Scottish ettle – intend, plan, design • aim to =plan to do airish = cold bitty bit - a small amount

• 5. Vulgarisms, i. e. coarse words that are not generally used in public, e. g. • bloody, hell, damn, shut up. • 6. Dialectical words • Scottish ettle – intend, plan, design • aim to =plan to do airish = cold bitty bit - a small amount

7. Colloquial coinages newspaperdom allrightnik Brunch neologism : : noun a newly coined word or expression • nonce word : : noun (of a word or expression) coined for or used on one occasion • • •

7. Colloquial coinages newspaperdom allrightnik Brunch neologism : : noun a newly coined word or expression • nonce word : : noun (of a word or expression) coined for or used on one occasion • • •

Nonce-word vs neologism • Both words refer to words or expressions that are newly coined. • But the nonce word “is one coined ‘for the nonce’—that is, made up for one occasion and unlikely to be used again. ”

Nonce-word vs neologism • Both words refer to words or expressions that are newly coined. • But the nonce word “is one coined ‘for the nonce’—that is, made up for one occasion and unlikely to be used again. ”

MEANING IN MORPHEMES • lexical meaning in morphemes: • denotational and connotational components. • The connotational component of meaning may be found not only in root-morphemes but in affixational morphemes as well.

MEANING IN MORPHEMES • lexical meaning in morphemes: • denotational and connotational components. • The connotational component of meaning may be found not only in root-morphemes but in affixational morphemes as well.

Meaning in morphemes • Endearing and diminutive suffixes, e. g. -ette (kitchenette), -ie(y) (dearie, girlie), -ling (duckling) they clearly bear a heavy emotive charge. The morphemes, e. g. -ly, -like, -ish, have the denotational meaning of similarity in the words womanly, womanlike, womanish;

Meaning in morphemes • Endearing and diminutive suffixes, e. g. -ette (kitchenette), -ie(y) (dearie, girlie), -ling (duckling) they clearly bear a heavy emotive charge. The morphemes, e. g. -ly, -like, -ish, have the denotational meaning of similarity in the words womanly, womanlike, womanish;

• The connotational component differs and ranges from the positive evaluation in -ly (womanly) to the derogatory in -ish (womanish). • Stylistic reference may also be found in morphemes of different types • The stylistic value of such derivational morphemes as, e. g. -ine (chlorine), -oid (rhomboid), -escence (effervescence) is clearly perceived to be bookish or scientific.

• The connotational component differs and ranges from the positive evaluation in -ly (womanly) to the derogatory in -ish (womanish). • Stylistic reference may also be found in morphemes of different types • The stylistic value of such derivational morphemes as, e. g. -ine (chlorine), -oid (rhomboid), -escence (effervescence) is clearly perceived to be bookish or scientific.

Differential meaning • Thus, denotational and connotational meaning are proper both to words and morphemes • Morphemes may possess specific meanings of their own: differential and distributional meanings.

Differential meaning • Thus, denotational and connotational meaning are proper both to words and morphemes • Morphemes may possess specific meanings of their own: differential and distributional meanings.

Differential meaning • the semantic component that serves to distinguish one word from all others containing identical morphemes. • In words consisting of two or more morphemes, one of the constituent morphemes always has differential meaning

Differential meaning • the semantic component that serves to distinguish one word from all others containing identical morphemes. • In words consisting of two or more morphemes, one of the constituent morphemes always has differential meaning

Differential meaning • -shelf in bookshelf serves to distinguish the word bookshelf from other words containing the morpheme book-, e. g. from bookcase, book-counter and so on. • Cf: note- in the compound word notebook, possesses the differential meaning which distinguishes notebook from exercisebook, copybook, textbook

Differential meaning • -shelf in bookshelf serves to distinguish the word bookshelf from other words containing the morpheme book-, e. g. from bookcase, book-counter and so on. • Cf: note- in the compound word notebook, possesses the differential meaning which distinguishes notebook from exercisebook, copybook, textbook

Distributional meaning • Distributional meaning is the meaning of the order and arrangement of morphemes making up the word. • D. m-g is found in all words containing more than one morpheme. The word singer consists of sing- and –er • Both of them have denotational meaning

Distributional meaning • Distributional meaning is the meaning of the order and arrangement of morphemes making up the word. • D. m-g is found in all words containing more than one morpheme. The word singer consists of sing- and –er • Both of them have denotational meaning

Distributional meaning • The element of meaning that enables us to understand the word is the pattern of arrangement of the component morphemes. • Compare boy- ish- ness and *ish- ness- boy or * boy- ness-ish. Different pattern turns it into a meaningless string of sounds.

Distributional meaning • The element of meaning that enables us to understand the word is the pattern of arrangement of the component morphemes. • Compare boy- ish- ness and *ish- ness- boy or * boy- ness-ish. Different pattern turns it into a meaningless string of sounds.

• Thank you for attention

• Thank you for attention

Change of meaning • Word-meaning is liable (=подвержено, склонно к ) to change in the course of the historical development of language. • It can be illustrated by the diachronic semantic analysis of many commonly used English words.

Change of meaning • Word-meaning is liable (=подвержено, склонно к ) to change in the course of the historical development of language. • It can be illustrated by the diachronic semantic analysis of many commonly used English words.

Change of meaning • The word fond in OE. used to mean ‘foolish’, ‘foolishly credulous’ (fond); • glad (OE, glaed) had the meaning of ‘bright’, ’shining’. • 1. Causes of semantic change: • a) extra-linguistic causes • b) linguistic causes.

Change of meaning • The word fond in OE. used to mean ‘foolish’, ‘foolishly credulous’ (fond); • glad (OE, glaed) had the meaning of ‘bright’, ’shining’. • 1. Causes of semantic change: • a) extra-linguistic causes • b) linguistic causes.

Extra-linguistic causes • Various changes in the life of the speech community; • Changes in economic and social structure; • Changes in ideas, scientific concepts, way of life; • Other spheres of human activities as reflected in word meanings. • These are called extralinguistic causes

Extra-linguistic causes • Various changes in the life of the speech community; • Changes in economic and social structure; • Changes in ideas, scientific concepts, way of life; • Other spheres of human activities as reflected in word meanings. • These are called extralinguistic causes

• mill (a Latin borrowing of the first century В. С. ) had a meaning "a building in which corn is ground into flour“ • When the first textile factories appeared in England, the old word mill was applied to these early industrial enterprises (=предприятия). • In this way the word mill added a new meaning "textile factory".

• mill (a Latin borrowing of the first century В. С. ) had a meaning "a building in which corn is ground into flour“ • When the first textile factories appeared in England, the old word mill was applied to these early industrial enterprises (=предприятия). • In this way the word mill added a new meaning "textile factory".

• Carriage had (and still has) the meaning "a vehicle drawn by horses” • with the first appearance of railways in England, it received a new meaning "a railway car“ • The words stalls, box, pit, circle had existed for a long time before the first theatres appeared in England.

• Carriage had (and still has) the meaning "a vehicle drawn by horses” • with the first appearance of railways in England, it received a new meaning "a railway car“ • The words stalls, box, pit, circle had existed for a long time before the first theatres appeared in England.

• OE eorde ‘the ground under people’s feet’, ‘the soil’ and ‘the world of man’ as opposed to heaven that was supposed to be inhabited first by Gods and later on, with the spread of Christianity, by God, his angels, saints and the souls of the dead.

• OE eorde ‘the ground under people’s feet’, ‘the soil’ and ‘the world of man’ as opposed to heaven that was supposed to be inhabited first by Gods and later on, with the spread of Christianity, by God, his angels, saints and the souls of the dead.

• With the progress of science earth came to mean ‘the third planet from the sun’ • With the development of electrical engineering earth means ‘a connection of a wire conductor with the earth’

• With the progress of science earth came to mean ‘the third planet from the sun’ • With the development of electrical engineering earth means ‘a connection of a wire conductor with the earth’

Linguistic causes • The general word for animal in English was deer (any animal) • Beast was borrowed from French into Middle English as a general word ; • after the word beast was introduced the meaning of deer became narrowed to its present meaning ‘a hoofed animal of which the males have antlers’.

Linguistic causes • The general word for animal in English was deer (any animal) • Beast was borrowed from French into Middle English as a general word ; • after the word beast was introduced the meaning of deer became narrowed to its present meaning ‘a hoofed animal of which the males have antlers’.

• Somewhat later the Latin word animal was also borrowed; • then the word beast was restricted, and its meaning served to separate the four-footed kind from all the other members of the animal kingdom. • Thus, beast displaced deer and was in its turn itself displaced by the generic animal.

• Somewhat later the Latin word animal was also borrowed; • then the word beast was restricted, and its meaning served to separate the four-footed kind from all the other members of the animal kingdom. • Thus, beast displaced deer and was in its turn itself displaced by the generic animal.

• Compare knave in the meaning of ‘swindler, scoundrel’ плут, мошенник • In Old English it looked like knafa its meaning was ‘a boy’ • Then the two words a boy and a knave collided • Now the wordit has acquired a pronounced (=a very clear) negative evaluative connotation

• Compare knave in the meaning of ‘swindler, scoundrel’ плут, мошенник • In Old English it looked like knafa its meaning was ‘a boy’ • Then the two words a boy and a knave collided • Now the wordit has acquired a pronounced (=a very clear) negative evaluative connotation

• Ellipsis • to starve, e. g. , in Old English (OE. steorfan) had the meaning ‘to die’ and was habitually used in collocation with the word hunger (ME. sterven of hunger) • In the course of time one of these was omitted and its meaning was transferred to its partner. This is ellipsis • Already in the 16 th century the verb itself acquired the meaning ‘to die of hunger’

• Ellipsis • to starve, e. g. , in Old English (OE. steorfan) had the meaning ‘to die’ and was habitually used in collocation with the word hunger (ME. sterven of hunger) • In the course of time one of these was omitted and its meaning was transferred to its partner. This is ellipsis • Already in the 16 th century the verb itself acquired the meaning ‘to die of hunger’

• To conlcude: • Linguistic causes are factors acting within the language system • Interaction and interdependence of vocabulary units in language and speech • Ellipsis • Collision of synonyms

• To conlcude: • Linguistic causes are factors acting within the language system • Interaction and interdependence of vocabulary units in language and speech • Ellipsis • Collision of synonyms

Nature of semantic change • A necessary condition of any semantic change, no matter what its cause, is some connection, some association between the old meaning and the new one. • There are two kinds of association involved as a rule in various semantic changes namely: a) similarity of meanings, and b) contiguity of meanings.

Nature of semantic change • A necessary condition of any semantic change, no matter what its cause, is some connection, some association between the old meaning and the new one. • There are two kinds of association involved as a rule in various semantic changes namely: a) similarity of meanings, and b) contiguity of meanings.

Similarity of meaning Eye part (organ ) of a body Eye hole in the end of a needle The association is based on resemblance Cf. drop (s) a small particle of water or other liquid • "ear-rings shaped as drops of water" (e. g. diamond drops) and "candy of the same shape" (e. g. mint drops). • •

Similarity of meaning Eye part (organ ) of a body Eye hole in the end of a needle The association is based on resemblance Cf. drop (s) a small particle of water or other liquid • "ear-rings shaped as drops of water" (e. g. diamond drops) and "candy of the same shape" (e. g. mint drops). • •

Metaphor • The word hand, acquired in the 16 th century the meaning of ‘a pointer of a clock or a watch’ • It is based on the similarity of one of the functions performed by the hand (to point at something) and the function of the clockpointer.

Metaphor • The word hand, acquired in the 16 th century the meaning of ‘a pointer of a clock or a watch’ • It is based on the similarity of one of the functions performed by the hand (to point at something) and the function of the clockpointer.

Metaphor • Metaphor may be described as a semantic process of associating two referents, one of which in some way resembles the other.

Metaphor • Metaphor may be described as a semantic process of associating two referents, one of which in some way resembles the other.

metaphor • Some examples • Cold and warm

metaphor • Some examples • Cold and warm

Contiguity of meaning • Contiguity of meanings or metonymy may be described as the semantic process of associating two referents one of which makes part of the other or is closely connected with it. • tongue — ‘the organ of speech’ in the meaning of ‘language’ (as in mother tongue; cf. also L. lingua, Russ. язык).

Contiguity of meaning • Contiguity of meanings or metonymy may be described as the semantic process of associating two referents one of which makes part of the other or is closely connected with it. • tongue — ‘the organ of speech’ in the meaning of ‘language’ (as in mother tongue; cf. also L. lingua, Russ. язык).

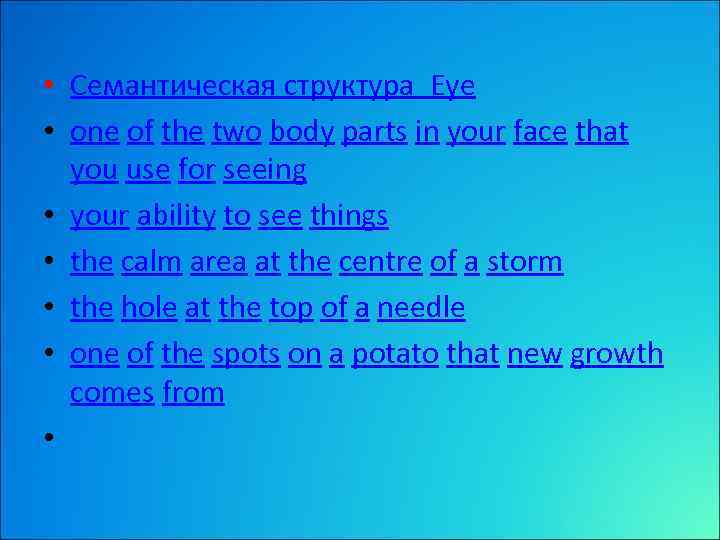

• Семантическая структура Eye • one of the two body parts in your face that you use for seeing • your ability to see things • the calm area at the centre of a storm • the hole at the top of a needle • one of the spots on a potato that new growth comes from •

• Семантическая структура Eye • one of the two body parts in your face that you use for seeing • your ability to see things • the calm area at the centre of a storm • the hole at the top of a needle • one of the spots on a potato that new growth comes from •

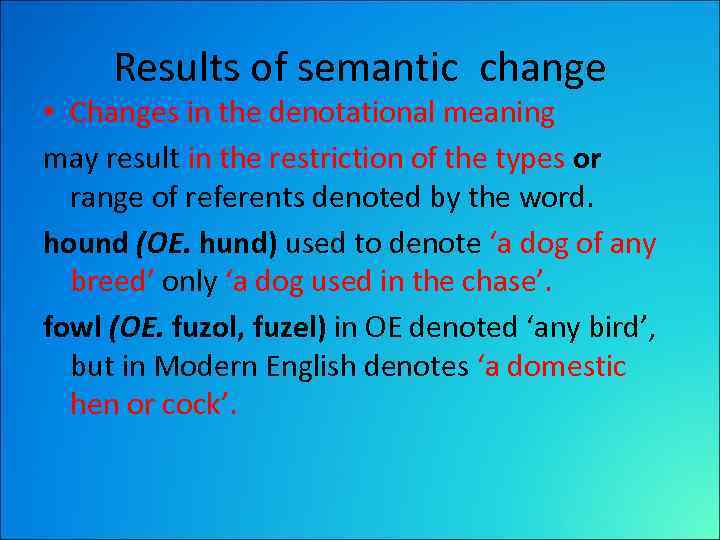

Results of semantic change • Changes in the denotational meaning may result in the restriction of the types or range of referents denoted by the word. hound (OE. hund) used to denote ‘a dog of any breed’ only ‘a dog used in the chase’. fowl (OE. fuzol, fuzel) in OE denoted ‘any bird’, but in Modern English denotes ‘a domestic hen or cock’.

Results of semantic change • Changes in the denotational meaning may result in the restriction of the types or range of referents denoted by the word. hound (OE. hund) used to denote ‘a dog of any breed’ only ‘a dog used in the chase’. fowl (OE. fuzol, fuzel) in OE denoted ‘any bird’, but in Modern English denotes ‘a domestic hen or cock’.

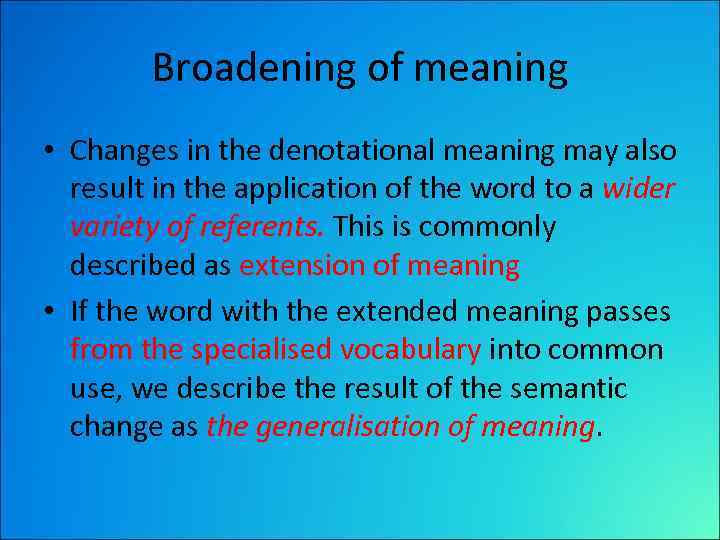

Broadening of meaning • Changes in the denotational meaning may also result in the application of the word to a wider variety of referents. This is commonly described as extension of meaning • If the word with the extended meaning passes from the specialised vocabulary into common use, we describe the result of the semantic change as the generalisation of meaning.

Broadening of meaning • Changes in the denotational meaning may also result in the application of the word to a wider variety of referents. This is commonly described as extension of meaning • If the word with the extended meaning passes from the specialised vocabulary into common use, we describe the result of the semantic change as the generalisation of meaning.

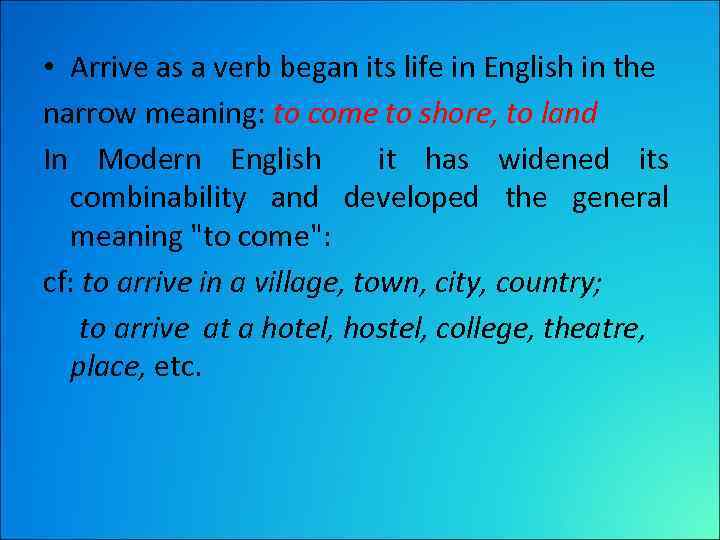

• Arrive as a verb began its life in English in the narrow meaning: to come to shore, to land In Modern English it has widened its combinability and developed the general meaning "to come": cf: to arrive in a village, town, city, country; to arrive at a hotel, hostel, college, theatre, place, etc.

• Arrive as a verb began its life in English in the narrow meaning: to come to shore, to land In Modern English it has widened its combinability and developed the general meaning "to come": cf: to arrive in a village, town, city, country; to arrive at a hotel, hostel, college, theatre, place, etc.

• As can be seen from the examples it is mainly the denotational component of the lexical meaning that is affected while the Connotational component remains unaltered. • There are other cases when the changes in the connotational meaning come to the fore. These changes, as a rule accompanied by a change in the denotational’ component, may be subdivided into two main groups:

• As can be seen from the examples it is mainly the denotational component of the lexical meaning that is affected while the Connotational component remains unaltered. • There are other cases when the changes in the connotational meaning come to the fore. These changes, as a rule accompanied by a change in the denotational’ component, may be subdivided into two main groups:

• a) pejorative development or the acquisition by the word of some derogatory emotive charge; • Knave boy > swindler, scoundrel • Villain farm servant, serf > base, vile person • Gossip god parent > the one who talks scandal; tells slanderous stories about other people

• a) pejorative development or the acquisition by the word of some derogatory emotive charge; • Knave boy > swindler, scoundrel • Villain farm servant, serf > base, vile person • Gossip god parent > the one who talks scandal; tells slanderous stories about other people

• b) ameliorative development or the improvement of the connotational component of meaning. • Fond initially meant foolish now means loving, affectionate Cf: Nice foolish > fine, good Tory brigand, highwayman > member of the Tories Knight manservant > noble, courageous man

• b) ameliorative development or the improvement of the connotational component of meaning. • Fond initially meant foolish now means loving, affectionate Cf: Nice foolish > fine, good Tory brigand, highwayman > member of the Tories Knight manservant > noble, courageous man

• Thank you for attention

• Thank you for attention

Polysemy • • So we have discussed the concept of meaning different types of word-meanings the changes they undergo in the course of the historical development of the English language.

Polysemy • • So we have discussed the concept of meaning different types of word-meanings the changes they undergo in the course of the historical development of the English language.

Polysemy • When analysing the word-meaning we observe that words as a rule are not units of a single meaning. • Monosemantic words, i. e. words having only one meaning are comparatively few in number • these are mainly scientific terms • hydrogen, molecule and the like.

Polysemy • When analysing the word-meaning we observe that words as a rule are not units of a single meaning. • Monosemantic words, i. e. words having only one meaning are comparatively few in number • these are mainly scientific terms • hydrogen, molecule and the like.

Polysemy • The bulk of English words are polysemantic, i. e. they possess more than one meaning. • The actual number of meanings of the commonly used words ranges from five to about a hundred. • In fact, the commoner the word the more meanings it has.

Polysemy • The bulk of English words are polysemantic, i. e. they possess more than one meaning. • The actual number of meanings of the commonly used words ranges from five to about a hundred. • In fact, the commoner the word the more meanings it has.

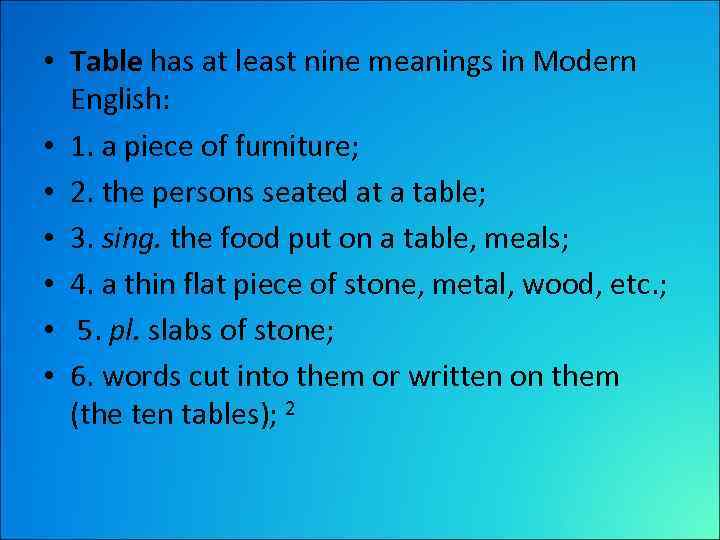

• Table has at least nine meanings in Modern English: • 1. a piece of furniture; • 2. the persons seated at a table; • 3. sing. the food put on a table, meals; • 4. a thin flat piece of stone, metal, wood, etc. ; • 5. pl. slabs of stone; • 6. words cut into them or written on them (the ten tables); 2

• Table has at least nine meanings in Modern English: • 1. a piece of furniture; • 2. the persons seated at a table; • 3. sing. the food put on a table, meals; • 4. a thin flat piece of stone, metal, wood, etc. ; • 5. pl. slabs of stone; • 6. words cut into them or written on them (the ten tables); 2

• 7. an orderly arrangement of facts, figures, etc. ; • 8. part of a machine-tool on which the work is put to be operated on; • 9. a level area, a plateau. • Each of the individual meanings can be described in terms of the types of meanings discussed above.

• 7. an orderly arrangement of facts, figures, etc. ; • 8. part of a machine-tool on which the work is put to be operated on; • 9. a level area, a plateau. • Each of the individual meanings can be described in terms of the types of meanings discussed above.

• We may, e. g. , analyse the eighth meaning of the word table into: • the part-of-speech meaning — that of the noun (which presupposes the grammatical meanings of number and case) • the lexical meaning made up of two components • The denotational component which can be interpreted as the dictionary definition (part of a machine-tool on which the work is put) •

• We may, e. g. , analyse the eighth meaning of the word table into: • the part-of-speech meaning — that of the noun (which presupposes the grammatical meanings of number and case) • the lexical meaning made up of two components • The denotational component which can be interpreted as the dictionary definition (part of a machine-tool on which the work is put) •

• the connotational component which can be identified • as a specific stylistic reference of this particular meaning of the word table (technical terminology). Cf. the Russian планшайба, стол станка.

• the connotational component which can be identified • as a specific stylistic reference of this particular meaning of the word table (technical terminology). Cf. the Russian планшайба, стол станка.

• In polysemantic words we are faced not with the problem of analysis of individual meanings, • but primarily with the problem of the interrelation and interdependence of the various meanings in the semantic structure of one and the same word.

• In polysemantic words we are faced not with the problem of analysis of individual meanings, • but primarily with the problem of the interrelation and interdependence of the various meanings in the semantic structure of one and the same word.

• Diachronic approach to polysemy • Polysemy is understood as the growth and development of the semantic structure of the word. • a word may retain its previous meaning or meanings and at the same time acquire one or several new ones. • Hence the main problem of polysemy in DA can be formulated as:

• Diachronic approach to polysemy • Polysemy is understood as the growth and development of the semantic structure of the word. • a word may retain its previous meaning or meanings and at the same time acquire one or several new ones. • Hence the main problem of polysemy in DA can be formulated as:

• did the word always possess all its meanings or did some of them appear earlier than the others? are the new meanings dependent on the meanings already existing? and if so what is the nature of this dependence? can we observe any changes in the arrangement of the meanings? and so on.

• did the word always possess all its meanings or did some of them appear earlier than the others? are the new meanings dependent on the meanings already existing? and if so what is the nature of this dependence? can we observe any changes in the arrangement of the meanings? and so on.

• did the word always possess all its meanings • did some of them appear earlier than the others? • are the new meanings dependent on the meanings already existing? • what is the nature of this dependence? • can we observe any changes in the arrangement of the meanings?

• did the word always possess all its meanings • did some of them appear earlier than the others? • are the new meanings dependent on the meanings already existing? • what is the nature of this dependence? • can we observe any changes in the arrangement of the meanings?

• diachronic semantic analysis of the polysemantic word table • the primary meaning is ‘a flat slab of stone or wood’, • It is proper to the word in the Old English period (OE. tabule from L. tabula); • all other meanings are secondary as they are derived from the primary meaning of the word and appeared later than the primary meaning

• diachronic semantic analysis of the polysemantic word table • the primary meaning is ‘a flat slab of stone or wood’, • It is proper to the word in the Old English period (OE. tabule from L. tabula); • all other meanings are secondary as they are derived from the primary meaning of the word and appeared later than the primary meaning

• Synchronic approach to polysemy • Synchronically we understand polysemy as the coexistence of various meanings of the same word at a certain historical period of the development of the English language. • In this case the problem of the interrelation and interdependence of individual meanings making up the semantic structure of the word must be investigated along different lines.

• Synchronic approach to polysemy • Synchronically we understand polysemy as the coexistence of various meanings of the same word at a certain historical period of the development of the English language. • In this case the problem of the interrelation and interdependence of individual meanings making up the semantic structure of the word must be investigated along different lines.

• table within SA we are concerned with the following problems: • are all the nine meanings equally representative of the semantic structure of this word? • Is the order in which the meanings are enumerated (or recorded) in dictionaries purely arbitrary • does it reflect the comparative value of individual meanings, the place they occupy in the semantic structure of the word table?

• table within SA we are concerned with the following problems: • are all the nine meanings equally representative of the semantic structure of this word? • Is the order in which the meanings are enumerated (or recorded) in dictionaries purely arbitrary • does it reflect the comparative value of individual meanings, the place they occupy in the semantic structure of the word table?

• does it reflect the place they occupy in the semantic structure of the word table? • Intuitively we feel that the meaning that first occurs to us whenever we hear or see the word table, is ‘an article of furniture’. This emerges as the basic or the central meaning of the word and all other meanings are minor in comparison. 1

• does it reflect the place they occupy in the semantic structure of the word table? • Intuitively we feel that the meaning that first occurs to us whenever we hear or see the word table, is ‘an article of furniture’. This emerges as the basic or the central meaning of the word and all other meanings are minor in comparison. 1

• the basic meaning occurs in various and widely different contexts, • minor meanings are observed only in certain contexts, • ‘to keep the table amused’, • ‘table of contents’ and so on. • The whole table heard what he said. • She sets a good table (the food placed on a table to be eaten)

• the basic meaning occurs in various and widely different contexts, • minor meanings are observed only in certain contexts, • ‘to keep the table amused’, • ‘table of contents’ and so on. • The whole table heard what he said. • She sets a good table (the food placed on a table to be eaten)

• it is hard to grade them in order of their comparative value. • Some may, for example, consider the second and the third meanings (‘the persons seated at the table’ and ‘the food put on the table’) as equally “important”, • some may argue that the meaning ‘food put on the table’ should be given priority.

• it is hard to grade them in order of their comparative value. • Some may, for example, consider the second and the third meanings (‘the persons seated at the table’ and ‘the food put on the table’) as equally “important”, • some may argue that the meaning ‘food put on the table’ should be given priority.

• the verb to get, • ‘to obtain’ (get a letter, knowledge, some sleep) • ‘to arrive’ (get to London, to get into bed) • which of the two meanings shall we regard as the basic meaning of this word?

• the verb to get, • ‘to obtain’ (get a letter, knowledge, some sleep) • ‘to arrive’ (get to London, to get into bed) • which of the two meanings shall we regard as the basic meaning of this word?

• Synchronically we do not have a reliable criteria • the frequency of the occurrence of meanings in speech. • ‘a piece of furniture’ possesses the highest frequency value and makes up 52% of all the uses of this word, • ‘an orderly arrangement of facts’ (table of contents) accounts for 35%, all other meanings between them make up just 13% of the uses of this word

• Synchronically we do not have a reliable criteria • the frequency of the occurrence of meanings in speech. • ‘a piece of furniture’ possesses the highest frequency value and makes up 52% of all the uses of this word, • ‘an orderly arrangement of facts’ (table of contents) accounts for 35%, all other meanings between them make up just 13% of the uses of this word

• There are several terms used to denote approximately the same concepts: • basic (majоr) meaning as opposed to minor meanings • central as opposed to marginal meanings. the terms are used interchangeably.

• There are several terms used to denote approximately the same concepts: • basic (majоr) meaning as opposed to minor meanings • central as opposed to marginal meanings. the terms are used interchangeably.

• Of great importance is the stylistic stratification of meanings of a polysemantic word as individual meanings may differ in their stylistic reference. • Stylistic (or regional) status of monosemantic words is easily perceived. • daddy can be referred to the colloquial stylistic layer, • parent to the bookish.

• Of great importance is the stylistic stratification of meanings of a polysemantic word as individual meanings may differ in their stylistic reference. • Stylistic (or regional) status of monosemantic words is easily perceived. • daddy can be referred to the colloquial stylistic layer, • parent to the bookish.

• The word movie is recognisably American and barnie is Scottish. • Polysemantic words as a rule cannot be given any such restrictive labels. • To do it we must state the meaning in which they are used. • There is nothing colloquial or slangy or American about the words • yellow denoting colour, • jerk in the meaning ‘a sudden movement or stopping of movement’

• The word movie is recognisably American and barnie is Scottish. • Polysemantic words as a rule cannot be given any such restrictive labels. • To do it we must state the meaning in which they are used. • There is nothing colloquial or slangy or American about the words • yellow denoting colour, • jerk in the meaning ‘a sudden movement or stopping of movement’

• But when yellow is used in the meaning of ’sensational’ • when jerk is used in the meaning of ‘an odd person’ it is both slang and American.

• But when yellow is used in the meaning of ’sensational’ • when jerk is used in the meaning of ‘an odd person’ it is both slang and American.

Historical Changeability of Semantic Structure Revolution first appeared in ME. 1350 — 1450 denoted ‘the revolving motion of celestial bodies’ • ‘the return or recurrence of a point or a period of time’. • Later acquired other meanings and among them that of ‘a complete overthrow of the established government or regime’ • •

Historical Changeability of Semantic Structure Revolution first appeared in ME. 1350 — 1450 denoted ‘the revolving motion of celestial bodies’ • ‘the return or recurrence of a point or a period of time’. • Later acquired other meanings and among them that of ‘a complete overthrow of the established government or regime’ • •

• and also ‘a complete change, a great reversal of conditions. • The meaning ‘revolving motion’ in ME. was both primary (diachronically) and central’ (synchronically).

• and also ‘a complete change, a great reversal of conditions. • The meaning ‘revolving motion’ in ME. was both primary (diachronically) and central’ (synchronically).