b5c43bb41fde7d7a2745763fe2613ef9.ppt

- Количество слайдов: 78

Slides for Chapter 9: Transactions and Concurrency Control From Coulouris, Dollimore and Kindberg Distributed Systems: Concepts and Design Edition 4, © Addison-Wesley 2005

Slides for Chapter 9: Transactions and Concurrency Control From Coulouris, Dollimore and Kindberg Distributed Systems: Concepts and Design Edition 4, © Addison-Wesley 2005

Transactions and Concurrency Control z A Transaction defines a sequence of server operations that is guaranteed to be atomic in the presence of multiple clients and server crash. z All concurrency control protocols are based on serial equivalence and are derived from rules of conflicting operations. y Locks used to order transactions that access the same object according to request order. y Optimistic concurrency control allows transactions to proceed until they are ready to commit, whereupon a check is made to see any conflicting operation on objects. y Timestamp ordering uses timestamps to order transactions that access the same object according to their starting time. Instructor’s Guide for Coulouris, Dollimore and Kindberg Distributed Systems: Concepts and Design Edn. 4 © Addison-Wesley Publishers 2005

Transactions and Concurrency Control z A Transaction defines a sequence of server operations that is guaranteed to be atomic in the presence of multiple clients and server crash. z All concurrency control protocols are based on serial equivalence and are derived from rules of conflicting operations. y Locks used to order transactions that access the same object according to request order. y Optimistic concurrency control allows transactions to proceed until they are ready to commit, whereupon a check is made to see any conflicting operation on objects. y Timestamp ordering uses timestamps to order transactions that access the same object according to their starting time. Instructor’s Guide for Coulouris, Dollimore and Kindberg Distributed Systems: Concepts and Design Edn. 4 © Addison-Wesley Publishers 2005

Banking Example z Each account is represented by a remote object whose interface Account provides operations for making deposits and withdrawals and for enquiring about and setting the balance. z Each branch of the bank is represented by a remote object whose interface Branch provides operations for creating a new account, for looking up an account by name and for enquiring about the total funds at that branch. z Main issue: unless a server is carefully designed, its operations performed on behalf of different clients may sometimes interfere with one another. Such interference may result in incorrect values in the object. Instructor’s Guide for Coulouris, Dollimore and Kindberg Distributed Systems: Concepts and Design Edn. 4 © Addison-Wesley Publishers 2005

Banking Example z Each account is represented by a remote object whose interface Account provides operations for making deposits and withdrawals and for enquiring about and setting the balance. z Each branch of the bank is represented by a remote object whose interface Branch provides operations for creating a new account, for looking up an account by name and for enquiring about the total funds at that branch. z Main issue: unless a server is carefully designed, its operations performed on behalf of different clients may sometimes interfere with one another. Such interference may result in incorrect values in the object. Instructor’s Guide for Coulouris, Dollimore and Kindberg Distributed Systems: Concepts and Design Edn. 4 © Addison-Wesley Publishers 2005

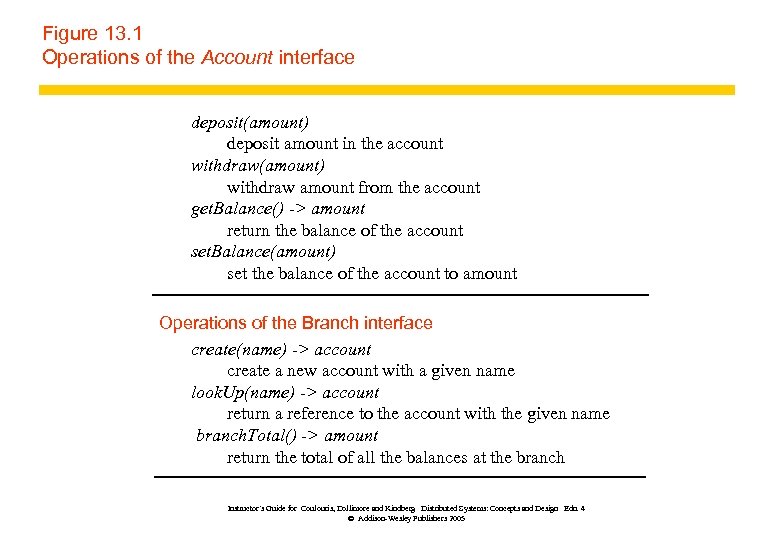

Figure 13. 1 Operations of the Account interface deposit(amount) deposit amount in the account withdraw(amount) withdraw amount from the account get. Balance() -> amount return the balance of the account set. Balance(amount) set the balance of the account to amount Operations of the Branch interface create(name) -> account create a new account with a given name look. Up(name) -> account return a reference to the account with the given name branch. Total() -> amount return the total of all the balances at the branch Instructor’s Guide for Coulouris, Dollimore and Kindberg Distributed Systems: Concepts and Design Edn. 4 © Addison-Wesley Publishers 2005

Figure 13. 1 Operations of the Account interface deposit(amount) deposit amount in the account withdraw(amount) withdraw amount from the account get. Balance() -> amount return the balance of the account set. Balance(amount) set the balance of the account to amount Operations of the Branch interface create(name) -> account create a new account with a given name look. Up(name) -> account return a reference to the account with the given name branch. Total() -> amount return the total of all the balances at the branch Instructor’s Guide for Coulouris, Dollimore and Kindberg Distributed Systems: Concepts and Design Edn. 4 © Addison-Wesley Publishers 2005

Simple Synchronization without Transactions z The use of multiple threads is beneficial to the performance. Multiple threads may access the same objects. z For example, deposit and withdraw methods: the actions of two concurrent executions of the methods could be interleaved arbitrarily and have strange effects on the instance variables of the account object. z Synchronized keyword can be applied to method in Java, so only one thread at a time can access an object. z If one thread invokes a synchronized method on an object, then that object is locked, another thread that invokes one of the synchronized method will be blocked. Instructor’s Guide for Coulouris, Dollimore and Kindberg Distributed Systems: Concepts and Design Edn. 4 © Addison-Wesley Publishers 2005

Simple Synchronization without Transactions z The use of multiple threads is beneficial to the performance. Multiple threads may access the same objects. z For example, deposit and withdraw methods: the actions of two concurrent executions of the methods could be interleaved arbitrarily and have strange effects on the instance variables of the account object. z Synchronized keyword can be applied to method in Java, so only one thread at a time can access an object. z If one thread invokes a synchronized method on an object, then that object is locked, another thread that invokes one of the synchronized method will be blocked. Instructor’s Guide for Coulouris, Dollimore and Kindberg Distributed Systems: Concepts and Design Edn. 4 © Addison-Wesley Publishers 2005

Enhancing Client Cooperation by Signaling z We have seen how clients may use a server as a means of sharing some resources. E. g. some clients update the server’s objects and other clients access them. z However, in some applications, threads need to communicate and coordinate their actions. z Producer and Consumer problem. y. Wait and Notify actions. Instructor’s Guide for Coulouris, Dollimore and Kindberg Distributed Systems: Concepts and Design Edn. 4 © Addison-Wesley Publishers 2005

Enhancing Client Cooperation by Signaling z We have seen how clients may use a server as a means of sharing some resources. E. g. some clients update the server’s objects and other clients access them. z However, in some applications, threads need to communicate and coordinate their actions. z Producer and Consumer problem. y. Wait and Notify actions. Instructor’s Guide for Coulouris, Dollimore and Kindberg Distributed Systems: Concepts and Design Edn. 4 © Addison-Wesley Publishers 2005

Transactions z Transaction originally from database management systems. z Clients require a sequence of separate requests to a server to be atomic in the sense that: y. They are free from interference by operations being performed on behalf of other concurrent clients; and y. Either all of the operations must be completed successfully or they must have no effect at all in the presence of server crashes. Instructor’s Guide for Coulouris, Dollimore and Kindberg Distributed Systems: Concepts and Design Edn. 4 © Addison-Wesley Publishers 2005

Transactions z Transaction originally from database management systems. z Clients require a sequence of separate requests to a server to be atomic in the sense that: y. They are free from interference by operations being performed on behalf of other concurrent clients; and y. Either all of the operations must be completed successfully or they must have no effect at all in the presence of server crashes. Instructor’s Guide for Coulouris, Dollimore and Kindberg Distributed Systems: Concepts and Design Edn. 4 © Addison-Wesley Publishers 2005

Atomicity z All or nothing: a transaction either completes successfully, and effects of all of its operations are recorded in the object, or it has no effect at all. y. Failure atomicity: effects are atomic even when server crashes y. Durability: after a transaction has completed successfully, all its effects are saved in permanent storage for recover later. z Isolation: each transaction must be performed without interference from other transactions. The intermediate effects of a transaction must not be visible to other transactions. Instructor’s Guide for Coulouris, Dollimore and Kindberg Distributed Systems: Concepts and Design Edn. 4 © Addison-Wesley Publishers 2005

Atomicity z All or nothing: a transaction either completes successfully, and effects of all of its operations are recorded in the object, or it has no effect at all. y. Failure atomicity: effects are atomic even when server crashes y. Durability: after a transaction has completed successfully, all its effects are saved in permanent storage for recover later. z Isolation: each transaction must be performed without interference from other transactions. The intermediate effects of a transaction must not be visible to other transactions. Instructor’s Guide for Coulouris, Dollimore and Kindberg Distributed Systems: Concepts and Design Edn. 4 © Addison-Wesley Publishers 2005

Figure 13. 2 A client’s banking transaction T: a. withdraw(100); b. deposit(100); Instructor’s Guide for Coulouris, Dollimore and Kindberg Distributed Systems: Concepts and Design Edn. 4 © Addison-Wesley Publishers 2005

Figure 13. 2 A client’s banking transaction T: a. withdraw(100); b. deposit(100); Instructor’s Guide for Coulouris, Dollimore and Kindberg Distributed Systems: Concepts and Design Edn. 4 © Addison-Wesley Publishers 2005

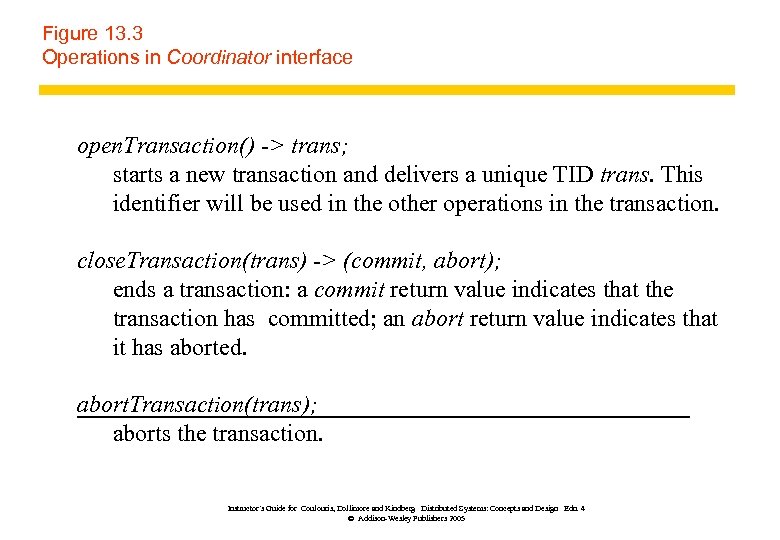

Figure 13. 3 Operations in Coordinator interface open. Transaction() -> trans; starts a new transaction and delivers a unique TID trans. This identifier will be used in the other operations in the transaction. close. Transaction(trans) -> (commit, abort); ends a transaction: a commit return value indicates that the transaction has committed; an abort return value indicates that it has aborted. abort. Transaction(trans); aborts the transaction. Instructor’s Guide for Coulouris, Dollimore and Kindberg Distributed Systems: Concepts and Design Edn. 4 © Addison-Wesley Publishers 2005

Figure 13. 3 Operations in Coordinator interface open. Transaction() -> trans; starts a new transaction and delivers a unique TID trans. This identifier will be used in the other operations in the transaction. close. Transaction(trans) -> (commit, abort); ends a transaction: a commit return value indicates that the transaction has committed; an abort return value indicates that it has aborted. abort. Transaction(trans); aborts the transaction. Instructor’s Guide for Coulouris, Dollimore and Kindberg Distributed Systems: Concepts and Design Edn. 4 © Addison-Wesley Publishers 2005

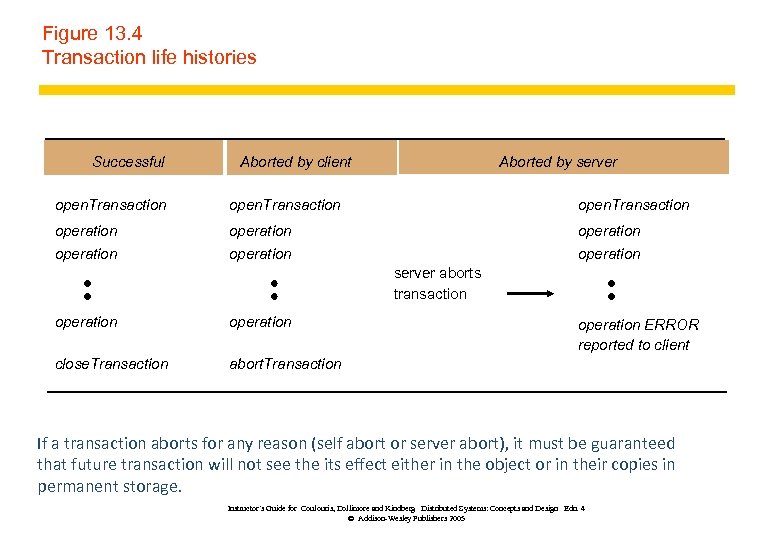

Figure 13. 4 Transaction life histories Successful Aborted by client Aborted by server open. Transaction operation operation server aborts transaction operation close. Transaction abort. Transaction operation ERROR reported to client If a transaction aborts for any reason (self abort or server abort), it must be guaranteed that future transaction will not see the its effect either in the object or in their copies in permanent storage. Instructor’s Guide for Coulouris, Dollimore and Kindberg Distributed Systems: Concepts and Design Edn. 4 © Addison-Wesley Publishers 2005

Figure 13. 4 Transaction life histories Successful Aborted by client Aborted by server open. Transaction operation operation server aborts transaction operation close. Transaction abort. Transaction operation ERROR reported to client If a transaction aborts for any reason (self abort or server abort), it must be guaranteed that future transaction will not see the its effect either in the object or in their copies in permanent storage. Instructor’s Guide for Coulouris, Dollimore and Kindberg Distributed Systems: Concepts and Design Edn. 4 © Addison-Wesley Publishers 2005

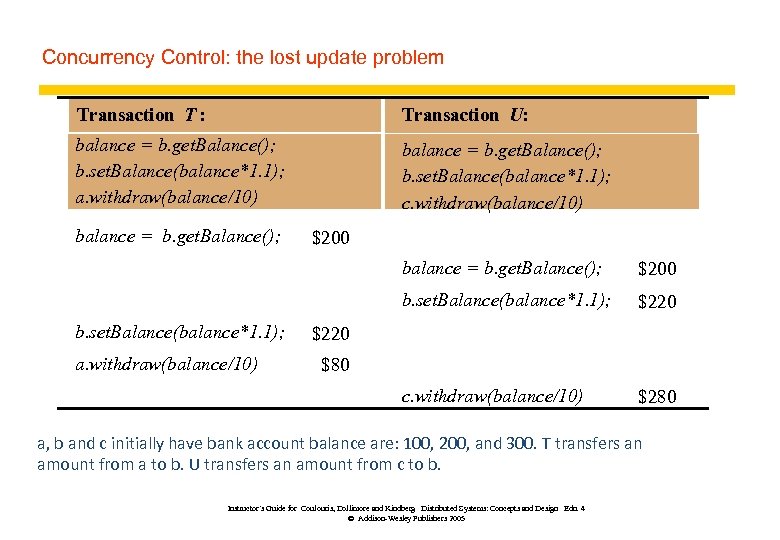

Concurrency Control: the lost update problem Transaction T : Transaction U: balance = b. get. Balance(); b. set. Balance(balance*1. 1); a. withdraw(balance/10) balance = b. get. Balance(); b. set. Balance(balance*1. 1); c. withdraw(balance/10) balance = b. get. Balance(); $200 balance = b. get. Balance(); b. set. Balance(balance*1. 1); a. withdraw(balance/10) $220 c. withdraw(balance/10) b. set. Balance(balance*1. 1); $200 $280 $220 $80 a, b and c initially have bank account balance are: 100, 200, and 300. T transfers an amount from a to b. U transfers an amount from c to b. Instructor’s Guide for Coulouris, Dollimore and Kindberg Distributed Systems: Concepts and Design Edn. 4 © Addison-Wesley Publishers 2005

Concurrency Control: the lost update problem Transaction T : Transaction U: balance = b. get. Balance(); b. set. Balance(balance*1. 1); a. withdraw(balance/10) balance = b. get. Balance(); b. set. Balance(balance*1. 1); c. withdraw(balance/10) balance = b. get. Balance(); $200 balance = b. get. Balance(); b. set. Balance(balance*1. 1); a. withdraw(balance/10) $220 c. withdraw(balance/10) b. set. Balance(balance*1. 1); $200 $280 $220 $80 a, b and c initially have bank account balance are: 100, 200, and 300. T transfers an amount from a to b. U transfers an amount from c to b. Instructor’s Guide for Coulouris, Dollimore and Kindberg Distributed Systems: Concepts and Design Edn. 4 © Addison-Wesley Publishers 2005

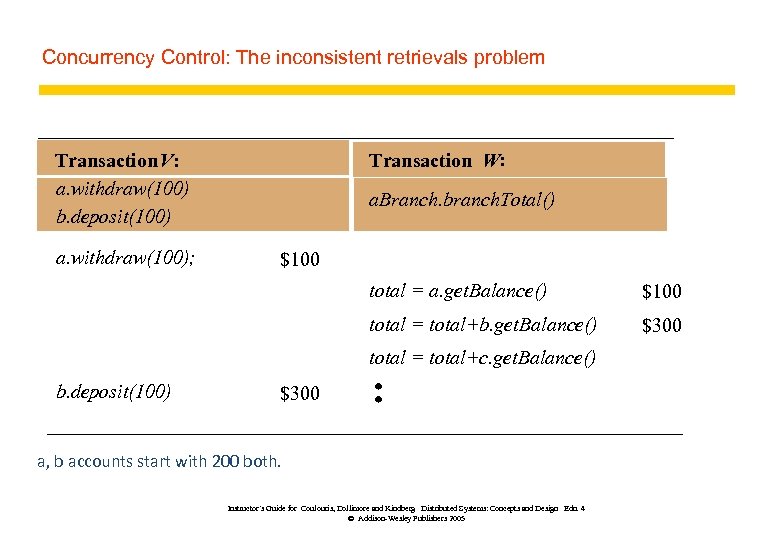

Concurrency Control: The inconsistent retrievals problem Transaction V: a. withdraw(100) b. deposit(100) a. withdraw(100); Transaction W: a. Branch. branch. Total() $100 total = a. get. Balance() $100 total = total+b. get. Balance() $300 total = total+c. get. Balance() b. deposit(100) $300 a, b accounts start with 200 both. Instructor’s Guide for Coulouris, Dollimore and Kindberg Distributed Systems: Concepts and Design Edn. 4 © Addison-Wesley Publishers 2005

Concurrency Control: The inconsistent retrievals problem Transaction V: a. withdraw(100) b. deposit(100) a. withdraw(100); Transaction W: a. Branch. branch. Total() $100 total = a. get. Balance() $100 total = total+b. get. Balance() $300 total = total+c. get. Balance() b. deposit(100) $300 a, b accounts start with 200 both. Instructor’s Guide for Coulouris, Dollimore and Kindberg Distributed Systems: Concepts and Design Edn. 4 © Addison-Wesley Publishers 2005

Serial equivalence z If these transactions are done at a time in some order, then the final result will be correct. z If we do not want to sacrifice the concurrency, an interleaving of the operations of transactions may lead to the same effect as if the transactions had been performed one at a time in some order. z We say it is a serially equivalent interleaving. z The use of serial equivalence is a criterion for correct concurrent execution to prevent lost updates and inconsistent retrievals. Instructor’s Guide for Coulouris, Dollimore and Kindberg Distributed Systems: Concepts and Design Edn. 4 © Addison-Wesley Publishers 2005

Serial equivalence z If these transactions are done at a time in some order, then the final result will be correct. z If we do not want to sacrifice the concurrency, an interleaving of the operations of transactions may lead to the same effect as if the transactions had been performed one at a time in some order. z We say it is a serially equivalent interleaving. z The use of serial equivalence is a criterion for correct concurrent execution to prevent lost updates and inconsistent retrievals. Instructor’s Guide for Coulouris, Dollimore and Kindberg Distributed Systems: Concepts and Design Edn. 4 © Addison-Wesley Publishers 2005

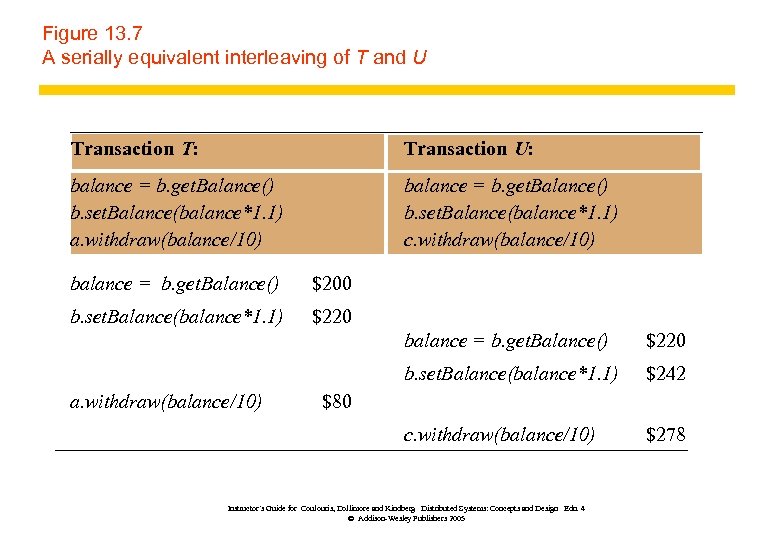

Figure 13. 7 A serially equivalent interleaving of T and U Transaction T: Transaction U: balance = b. get. Balance() b. set. Balance(balance*1. 1) a. withdraw(balance/10) balance = b. get. Balance() b. set. Balance(balance*1. 1) c. withdraw(balance/10) balance = b. get. Balance() $200 b. set. Balance(balance*1. 1) $220 balance = b. get. Balance() b. set. Balance(balance*1. 1) $242 c. withdraw(balance/10) a. withdraw(balance/10) $220 $278 $80 Instructor’s Guide for Coulouris, Dollimore and Kindberg Distributed Systems: Concepts and Design Edn. 4 © Addison-Wesley Publishers 2005

Figure 13. 7 A serially equivalent interleaving of T and U Transaction T: Transaction U: balance = b. get. Balance() b. set. Balance(balance*1. 1) a. withdraw(balance/10) balance = b. get. Balance() b. set. Balance(balance*1. 1) c. withdraw(balance/10) balance = b. get. Balance() $200 b. set. Balance(balance*1. 1) $220 balance = b. get. Balance() b. set. Balance(balance*1. 1) $242 c. withdraw(balance/10) a. withdraw(balance/10) $220 $278 $80 Instructor’s Guide for Coulouris, Dollimore and Kindberg Distributed Systems: Concepts and Design Edn. 4 © Addison-Wesley Publishers 2005

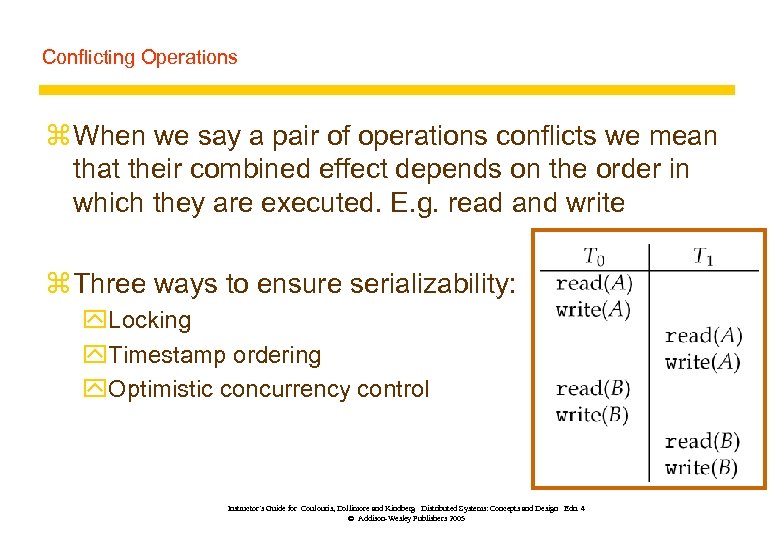

Conflicting Operations z When we say a pair of operations conflicts we mean that their combined effect depends on the order in which they are executed. E. g. read and write z Three ways to ensure serializability: y. Locking y. Timestamp ordering y. Optimistic concurrency control Instructor’s Guide for Coulouris, Dollimore and Kindberg Distributed Systems: Concepts and Design Edn. 4 © Addison-Wesley Publishers 2005

Conflicting Operations z When we say a pair of operations conflicts we mean that their combined effect depends on the order in which they are executed. E. g. read and write z Three ways to ensure serializability: y. Locking y. Timestamp ordering y. Optimistic concurrency control Instructor’s Guide for Coulouris, Dollimore and Kindberg Distributed Systems: Concepts and Design Edn. 4 © Addison-Wesley Publishers 2005

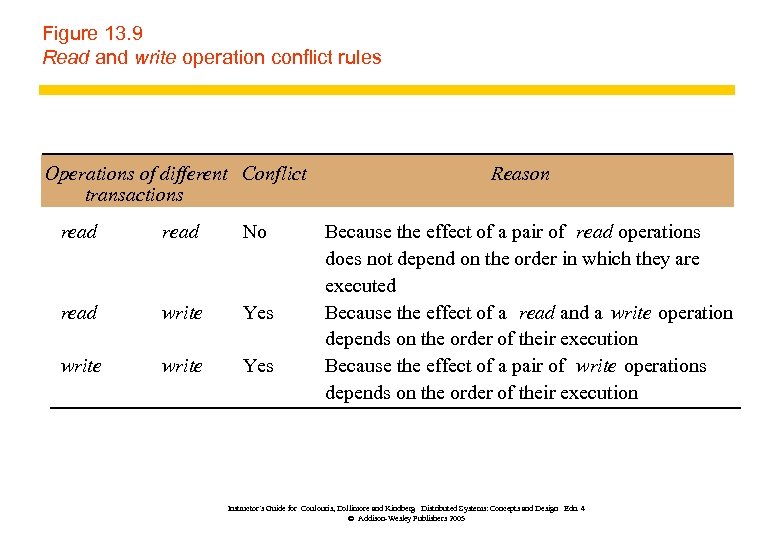

Figure 13. 9 Read and write operation conflict rules Operations of different Conflict transactions read No read write Yes Reason Because the effect of a pair of read operations does not depend on the order in which they are executed Because the effect of a read and a write operation depends on the order of their execution Because the effect of a pair of write operations depends on the order of their execution Instructor’s Guide for Coulouris, Dollimore and Kindberg Distributed Systems: Concepts and Design Edn. 4 © Addison-Wesley Publishers 2005

Figure 13. 9 Read and write operation conflict rules Operations of different Conflict transactions read No read write Yes Reason Because the effect of a pair of read operations does not depend on the order in which they are executed Because the effect of a read and a write operation depends on the order of their execution Because the effect of a pair of write operations depends on the order of their execution Instructor’s Guide for Coulouris, Dollimore and Kindberg Distributed Systems: Concepts and Design Edn. 4 © Addison-Wesley Publishers 2005

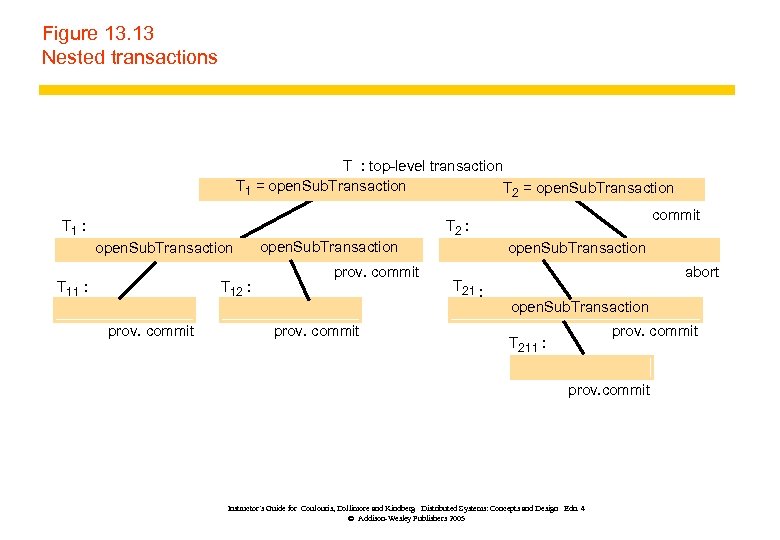

Figure 13. 13 Nested transactions T : top-level transaction T 1 = open. Sub. Transaction T 2 = open. Sub. Transaction T 1 : commit T 2 : open. Sub. Transaction T 11 : T 12 : prov. commit open. Sub. Transaction T 21 : abort open. Sub. Transaction prov. commit T 211 : prov. commit Instructor’s Guide for Coulouris, Dollimore and Kindberg Distributed Systems: Concepts and Design Edn. 4 © Addison-Wesley Publishers 2005

Figure 13. 13 Nested transactions T : top-level transaction T 1 = open. Sub. Transaction T 2 = open. Sub. Transaction T 1 : commit T 2 : open. Sub. Transaction T 11 : T 12 : prov. commit open. Sub. Transaction T 21 : abort open. Sub. Transaction prov. commit T 211 : prov. commit Instructor’s Guide for Coulouris, Dollimore and Kindberg Distributed Systems: Concepts and Design Edn. 4 © Addison-Wesley Publishers 2005

Locks z A simple example of a serializing mechanism is the use of exclusive locks. z Server can lock any object that is about to be used by a client. z If another client wants to access the same object, it has to wait until the object is unlocked in the end. Instructor’s Guide for Coulouris, Dollimore and Kindberg Distributed Systems: Concepts and Design Edn. 4 © Addison-Wesley Publishers 2005

Locks z A simple example of a serializing mechanism is the use of exclusive locks. z Server can lock any object that is about to be used by a client. z If another client wants to access the same object, it has to wait until the object is unlocked in the end. Instructor’s Guide for Coulouris, Dollimore and Kindberg Distributed Systems: Concepts and Design Edn. 4 © Addison-Wesley Publishers 2005

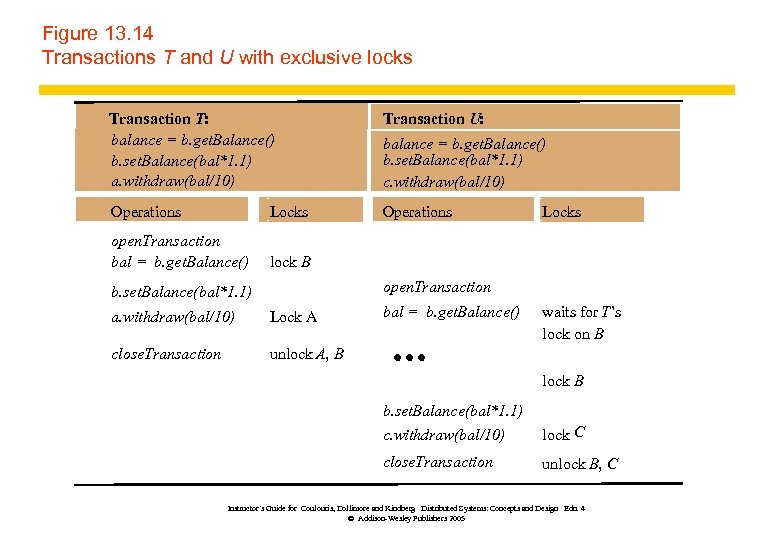

Figure 13. 14 Transactions T and U with exclusive locks Transaction T: balance = b. get. Balance() b. set. Balance(bal*1. 1) a. withdraw(bal/10) Transaction U: Operations Locks Operations open. Transaction bal = b. get. Balance() lock B balance = b. get. Balance() b. set. Balance(bal*1. 1) c. withdraw(bal/10) Locks open. Transaction b. set. Balance(bal*1. 1) a. withdraw(bal/10) Lock A close. Transaction bal = b. get. Balance() waits for T’s lock on B unlock A, B lock B b. set. Balance(bal*1. 1) c. withdraw(bal/10) lock C close. Transaction unlock B, C Instructor’s Guide for Coulouris, Dollimore and Kindberg Distributed Systems: Concepts and Design Edn. 4 © Addison-Wesley Publishers 2005

Figure 13. 14 Transactions T and U with exclusive locks Transaction T: balance = b. get. Balance() b. set. Balance(bal*1. 1) a. withdraw(bal/10) Transaction U: Operations Locks Operations open. Transaction bal = b. get. Balance() lock B balance = b. get. Balance() b. set. Balance(bal*1. 1) c. withdraw(bal/10) Locks open. Transaction b. set. Balance(bal*1. 1) a. withdraw(bal/10) Lock A close. Transaction bal = b. get. Balance() waits for T’s lock on B unlock A, B lock B b. set. Balance(bal*1. 1) c. withdraw(bal/10) lock C close. Transaction unlock B, C Instructor’s Guide for Coulouris, Dollimore and Kindberg Distributed Systems: Concepts and Design Edn. 4 © Addison-Wesley Publishers 2005

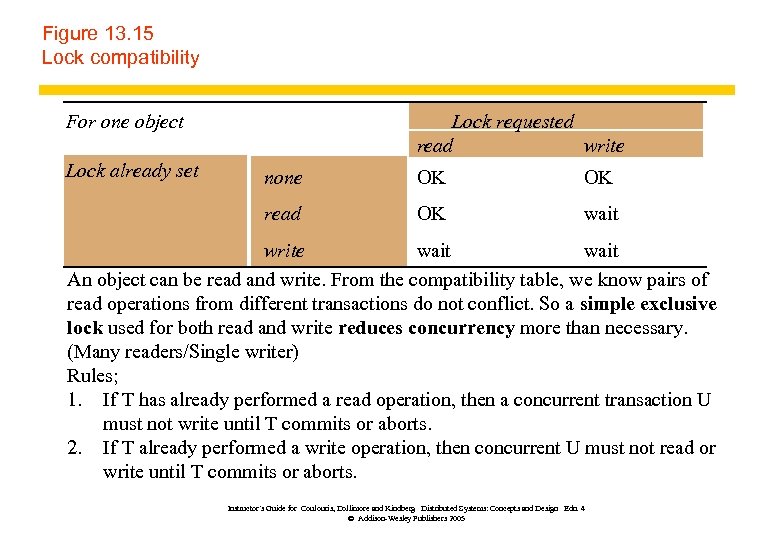

Figure 13. 15 Lock compatibility For one object Lock already set Lock requested read write none OK OK read OK wait write wait An object can be read and write. From the compatibility table, we know pairs of read operations from different transactions do not conflict. So a simple exclusive lock used for both read and write reduces concurrency more than necessary. (Many readers/Single writer) Rules; 1. If T has already performed a read operation, then a concurrent transaction U must not write until T commits or aborts. 2. If T already performed a write operation, then concurrent U must not read or write until T commits or aborts. Instructor’s Guide for Coulouris, Dollimore and Kindberg Distributed Systems: Concepts and Design Edn. 4 © Addison-Wesley Publishers 2005

Figure 13. 15 Lock compatibility For one object Lock already set Lock requested read write none OK OK read OK wait write wait An object can be read and write. From the compatibility table, we know pairs of read operations from different transactions do not conflict. So a simple exclusive lock used for both read and write reduces concurrency more than necessary. (Many readers/Single writer) Rules; 1. If T has already performed a read operation, then a concurrent transaction U must not write until T commits or aborts. 2. If T already performed a write operation, then concurrent U must not read or write until T commits or aborts. Instructor’s Guide for Coulouris, Dollimore and Kindberg Distributed Systems: Concepts and Design Edn. 4 © Addison-Wesley Publishers 2005

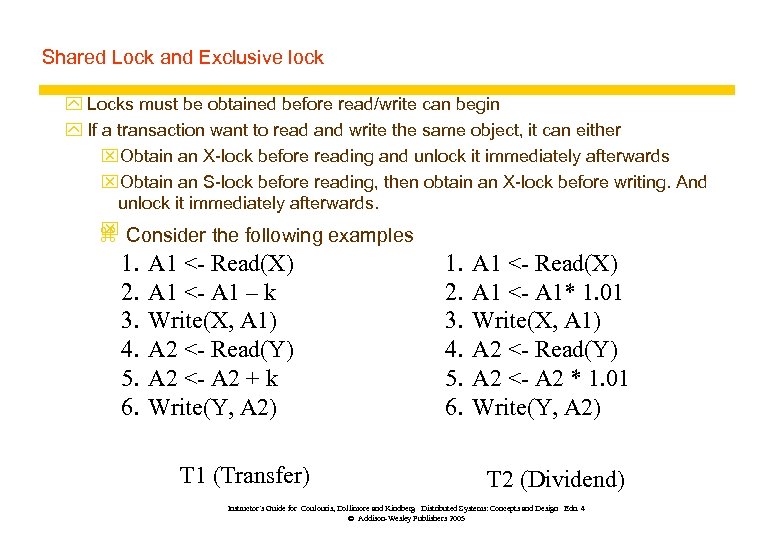

Shared Lock and Exclusive lock y Locks must be obtained before read/write can begin y If a transaction want to read and write the same object, it can either x. Obtain an X-lock before reading and unlock it immediately afterwards x. Obtain an S-lock before reading, then obtain an X-lock before writing. And unlock it immediately afterwards. x z Consider the following examples 1. 2. 3. 4. 5. 6. A 1 <- Read(X) A 1 <- A 1 – k Write(X, A 1) A 2 <- Read(Y) A 2 <- A 2 + k Write(Y, A 2) T 1 (Transfer) 1. 2. 3. 4. 5. 6. A 1 <- Read(X) A 1 <- A 1* 1. 01 Write(X, A 1) A 2 <- Read(Y) A 2 <- A 2 * 1. 01 Write(Y, A 2) T 2 (Dividend) Instructor’s Guide for Coulouris, Dollimore and Kindberg Distributed Systems: Concepts and Design Edn. 4 © Addison-Wesley Publishers 2005

Shared Lock and Exclusive lock y Locks must be obtained before read/write can begin y If a transaction want to read and write the same object, it can either x. Obtain an X-lock before reading and unlock it immediately afterwards x. Obtain an S-lock before reading, then obtain an X-lock before writing. And unlock it immediately afterwards. x z Consider the following examples 1. 2. 3. 4. 5. 6. A 1 <- Read(X) A 1 <- A 1 – k Write(X, A 1) A 2 <- Read(Y) A 2 <- A 2 + k Write(Y, A 2) T 1 (Transfer) 1. 2. 3. 4. 5. 6. A 1 <- Read(X) A 1 <- A 1* 1. 01 Write(X, A 1) A 2 <- Read(Y) A 2 <- A 2 * 1. 01 Write(Y, A 2) T 2 (Dividend) Instructor’s Guide for Coulouris, Dollimore and Kindberg Distributed Systems: Concepts and Design Edn. 4 © Addison-Wesley Publishers 2005

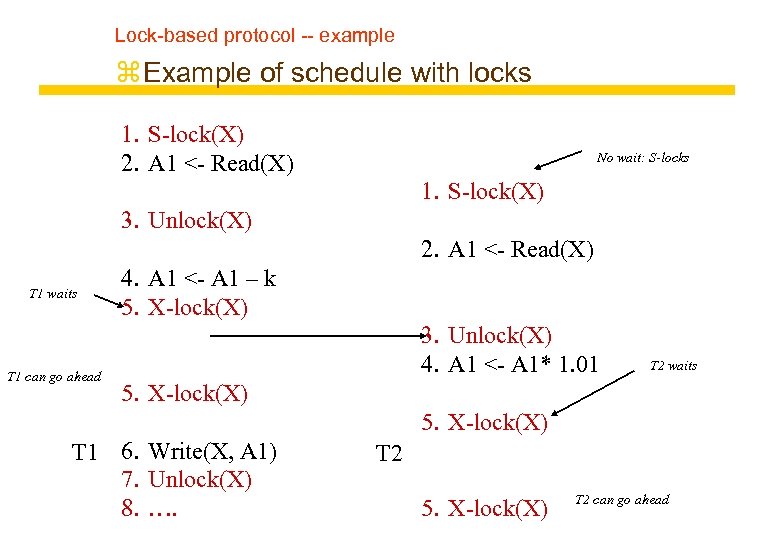

Lock-based protocol -- example z Example of schedule with locks 1. S-lock(X) 2. A 1 <- Read(X) No wait: S-locks 1. S-lock(X) 3. Unlock(X) 2. A 1 <- Read(X) T 1 waits T 1 can go ahead 4. A 1 <- A 1 – k 5. X-lock(X) 3. Unlock(X) 4. A 1 <- A 1* 1. 01 T 2 waits 5. X-lock(X) T 1 6. Write(X, A 1) 7. Unlock(X) 8. …. T 2 5. X-lock(X) T 2 can go ahead

Lock-based protocol -- example z Example of schedule with locks 1. S-lock(X) 2. A 1 <- Read(X) No wait: S-locks 1. S-lock(X) 3. Unlock(X) 2. A 1 <- Read(X) T 1 waits T 1 can go ahead 4. A 1 <- A 1 – k 5. X-lock(X) 3. Unlock(X) 4. A 1 <- A 1* 1. 01 T 2 waits 5. X-lock(X) T 1 6. Write(X, A 1) 7. Unlock(X) 8. …. T 2 5. X-lock(X) T 2 can go ahead

Lock based protocols -- questions z Does having locks this way guarantee conflict serializability? z Is there any other requirements in the order/manner of accquiring/releasing locks? z Does it matter when to acquire locks? z Does it matter when to release locks?

Lock based protocols -- questions z Does having locks this way guarantee conflict serializability? z Is there any other requirements in the order/manner of accquiring/releasing locks? z Does it matter when to acquire locks? z Does it matter when to release locks?

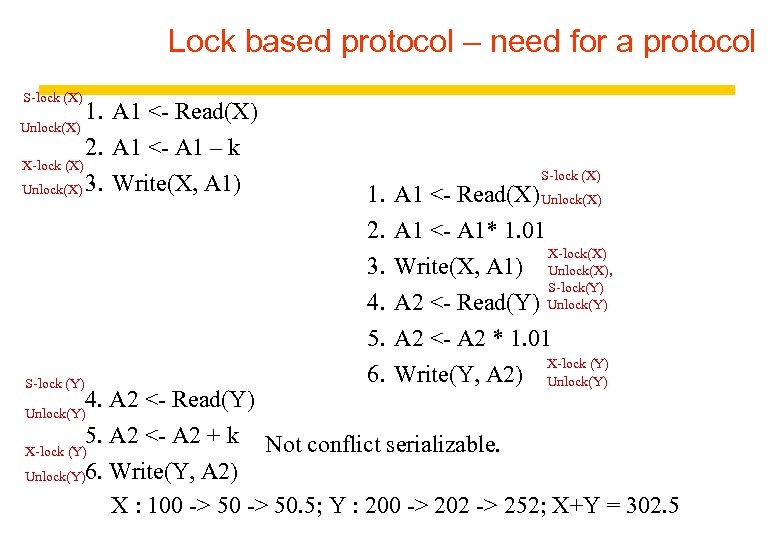

Lock based protocol – need for a protocol S-lock (X) 1. A 1 <- Read(X) Unlock(X) 2. A 1 <- A 1 – k X-lock (X) Unlock(X) 3. Write(X, A 1) S-lock (Y) 1. 2. 3. 4. 5. 6. S-lock (X) A 1 <- Read(X) Unlock(X) A 1 <- A 1* 1. 01 X-lock(X) Write(X, A 1) Unlock(X), S-lock(Y) Unlock(Y) A 2 <- Read(Y) A 2 <- A 2 * 1. 01 X-lock (Y) Write(Y, A 2) Unlock(Y) 4. A 2 <- Read(Y) 5. A 2 <- A 2 + k Not conflict serializable. X-lock (Y) Unlock(Y)6. Write(Y, A 2) X : 100 -> 50. 5; Y : 200 -> 202 -> 252; X+Y = 302. 5 Unlock(Y)

Lock based protocol – need for a protocol S-lock (X) 1. A 1 <- Read(X) Unlock(X) 2. A 1 <- A 1 – k X-lock (X) Unlock(X) 3. Write(X, A 1) S-lock (Y) 1. 2. 3. 4. 5. 6. S-lock (X) A 1 <- Read(X) Unlock(X) A 1 <- A 1* 1. 01 X-lock(X) Write(X, A 1) Unlock(X), S-lock(Y) Unlock(Y) A 2 <- Read(Y) A 2 <- A 2 * 1. 01 X-lock (Y) Write(Y, A 2) Unlock(Y) 4. A 2 <- Read(Y) 5. A 2 <- A 2 + k Not conflict serializable. X-lock (Y) Unlock(Y)6. Write(Y, A 2) X : 100 -> 50. 5; Y : 200 -> 202 -> 252; X+Y = 302. 5 Unlock(Y)

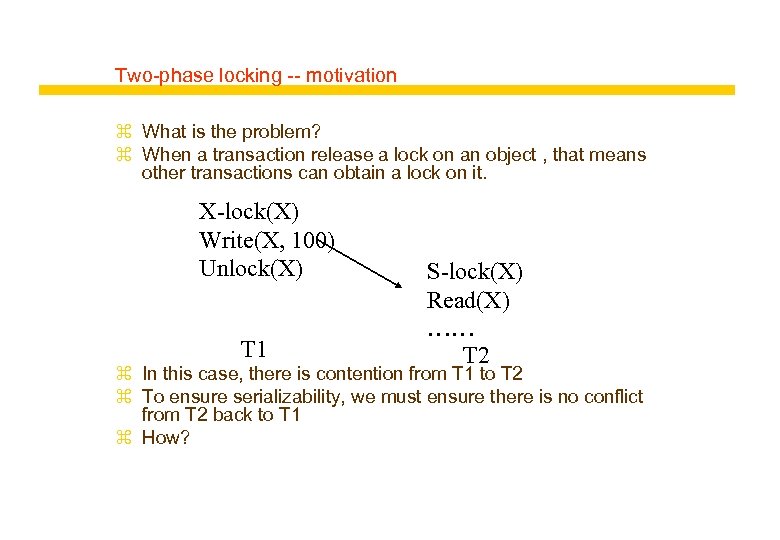

Two-phase locking -- motivation z What is the problem? z When a transaction release a lock on an object , that means other transactions can obtain a lock on it. X-lock(X) Write(X, 100) Unlock(X) T 1 S-lock(X) Read(X) …… T 2 z In this case, there is contention from T 1 to T 2 z To ensure serializability, we must ensure there is no conflict from T 2 back to T 1 z How?

Two-phase locking -- motivation z What is the problem? z When a transaction release a lock on an object , that means other transactions can obtain a lock on it. X-lock(X) Write(X, 100) Unlock(X) T 1 S-lock(X) Read(X) …… T 2 z In this case, there is contention from T 1 to T 2 z To ensure serializability, we must ensure there is no conflict from T 2 back to T 1 z How?

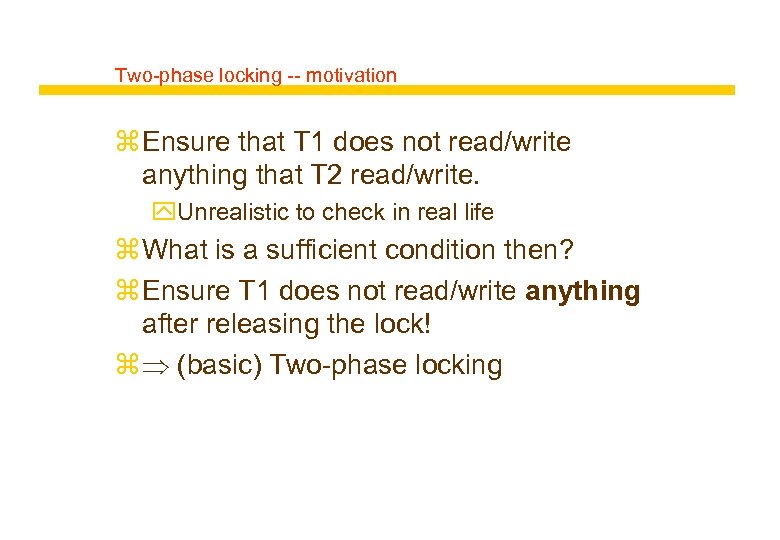

Two-phase locking -- motivation z Ensure that T 1 does not read/write anything that T 2 read/write. y. Unrealistic to check in real life z What is a sufficient condition then? z Ensure T 1 does not read/write anything after releasing the lock! z (basic) Two-phase locking

Two-phase locking -- motivation z Ensure that T 1 does not read/write anything that T 2 read/write. y. Unrealistic to check in real life z What is a sufficient condition then? z Ensure T 1 does not read/write anything after releasing the lock! z (basic) Two-phase locking

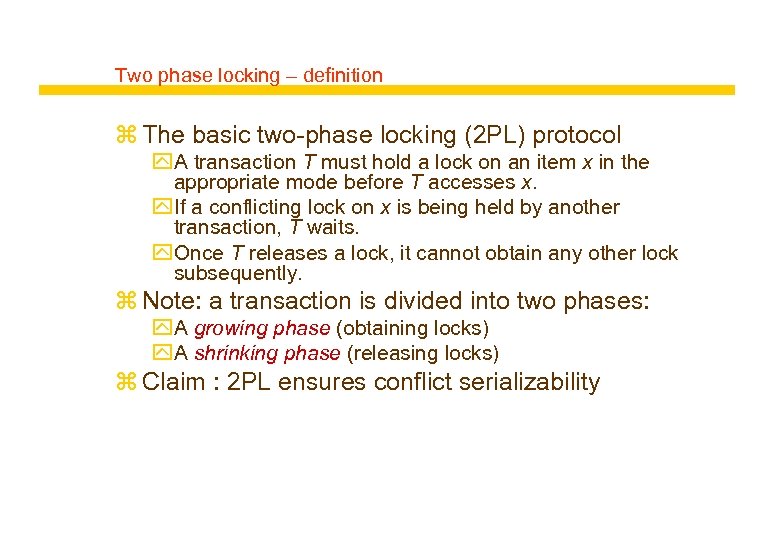

Two phase locking – definition z The basic two-phase locking (2 PL) protocol y. A transaction T must hold a lock on an item x in the appropriate mode before T accesses x. y. If a conflicting lock on x is being held by another transaction, T waits. y. Once T releases a lock, it cannot obtain any other lock subsequently. z Note: a transaction is divided into two phases: y. A growing phase (obtaining locks) y. A shrinking phase (releasing locks) z Claim : 2 PL ensures conflict serializability

Two phase locking – definition z The basic two-phase locking (2 PL) protocol y. A transaction T must hold a lock on an item x in the appropriate mode before T accesses x. y. If a conflicting lock on x is being held by another transaction, T waits. y. Once T releases a lock, it cannot obtain any other lock subsequently. z Note: a transaction is divided into two phases: y. A growing phase (obtaining locks) y. A shrinking phase (releasing locks) z Claim : 2 PL ensures conflict serializability

Two phase locking – Serializability z Lock-point: the point where the transaction obtains all the locks z With 2 PL, a schedule is conflict equivalent to a a serial schedule ordered by the lockpoint of the transactions

Two phase locking – Serializability z Lock-point: the point where the transaction obtains all the locks z With 2 PL, a schedule is conflict equivalent to a a serial schedule ordered by the lockpoint of the transactions

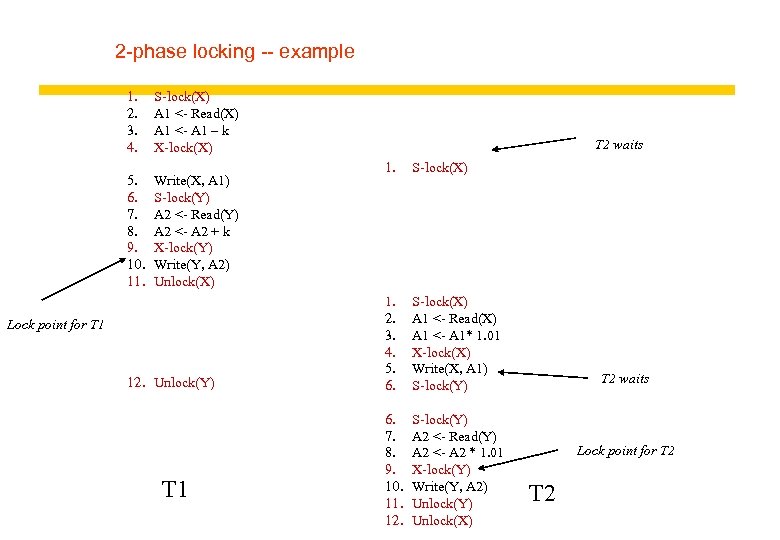

2 -phase locking -- example 1. 2. 3. 4. 5. 6. 7. 8. 9. 10. 11. S-lock(X) A 1 <- Read(X) A 1 <- A 1 – k X-lock(X) Write(X, A 1) S-lock(Y) A 2 <- Read(Y) A 2 <- A 2 + k X-lock(Y) Write(Y, A 2) Unlock(X) Lock point for T 1 12. Unlock(Y) T 1 T 2 waits 1. S-lock(X) 1. 2. 3. 4. 5. 6. S-lock(X) A 1 <- Read(X) A 1 <- A 1* 1. 01 X-lock(X) Write(X, A 1) S-lock(Y) 6. 7. 8. 9. 10. 11. 12. S-lock(Y) A 2 <- Read(Y) A 2 <- A 2 * 1. 01 X-lock(Y) Write(Y, A 2) Unlock(Y) Unlock(X) T 2 waits Lock point for T 2

2 -phase locking -- example 1. 2. 3. 4. 5. 6. 7. 8. 9. 10. 11. S-lock(X) A 1 <- Read(X) A 1 <- A 1 – k X-lock(X) Write(X, A 1) S-lock(Y) A 2 <- Read(Y) A 2 <- A 2 + k X-lock(Y) Write(Y, A 2) Unlock(X) Lock point for T 1 12. Unlock(Y) T 1 T 2 waits 1. S-lock(X) 1. 2. 3. 4. 5. 6. S-lock(X) A 1 <- Read(X) A 1 <- A 1* 1. 01 X-lock(X) Write(X, A 1) S-lock(Y) 6. 7. 8. 9. 10. 11. 12. S-lock(Y) A 2 <- Read(Y) A 2 <- A 2 * 1. 01 X-lock(Y) Write(Y, A 2) Unlock(Y) Unlock(X) T 2 waits Lock point for T 2

Recoverability from aborts z Servers must record the effect of all committed transactions and none of the effects of the aborted transactions. z A transaction may abort by preventing it affecting other concurrent transactions if it does so. z Two problems associated with aborting transactions that may occur in the presence of serially equivalent execution of transactions: y. Dirty reads y. Premature writes Instructor’s Guide for Coulouris, Dollimore and Kindberg Distributed Systems: Concepts and Design Edn. 4 © Addison-Wesley Publishers 2005

Recoverability from aborts z Servers must record the effect of all committed transactions and none of the effects of the aborted transactions. z A transaction may abort by preventing it affecting other concurrent transactions if it does so. z Two problems associated with aborting transactions that may occur in the presence of serially equivalent execution of transactions: y. Dirty reads y. Premature writes Instructor’s Guide for Coulouris, Dollimore and Kindberg Distributed Systems: Concepts and Design Edn. 4 © Addison-Wesley Publishers 2005

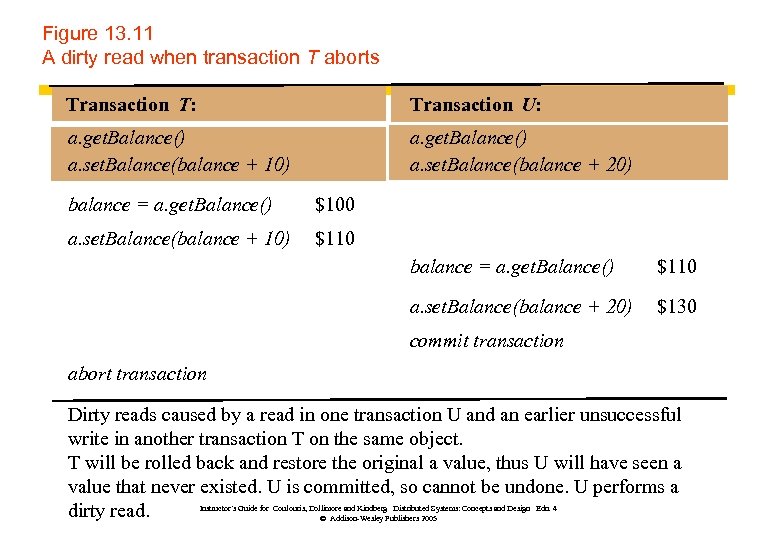

Figure 13. 11 A dirty read when transaction T aborts Transaction T: Transaction U: a. get. Balance() a. set. Balance(balance + 10) a. get. Balance() a. set. Balance(balance + 20) balance = a. get. Balance() $100 a. set. Balance(balance + 10) $110 balance = a. get. Balance() $110 a. set. Balance(balance + 20) $130 commit transaction abort transaction Dirty reads caused by a read in one transaction U and an earlier unsuccessful write in another transaction T on the same object. T will be rolled back and restore the original a value, thus U will have seen a value that never existed. U is committed, so cannot be undone. U performs a dirty read. Instructor’s Guide for Coulouris, Dollimore and Kindberg Distributed Systems: Concepts and Design Edn. 4 © Addison-Wesley Publishers 2005

Figure 13. 11 A dirty read when transaction T aborts Transaction T: Transaction U: a. get. Balance() a. set. Balance(balance + 10) a. get. Balance() a. set. Balance(balance + 20) balance = a. get. Balance() $100 a. set. Balance(balance + 10) $110 balance = a. get. Balance() $110 a. set. Balance(balance + 20) $130 commit transaction abort transaction Dirty reads caused by a read in one transaction U and an earlier unsuccessful write in another transaction T on the same object. T will be rolled back and restore the original a value, thus U will have seen a value that never existed. U is committed, so cannot be undone. U performs a dirty read. Instructor’s Guide for Coulouris, Dollimore and Kindberg Distributed Systems: Concepts and Design Edn. 4 © Addison-Wesley Publishers 2005

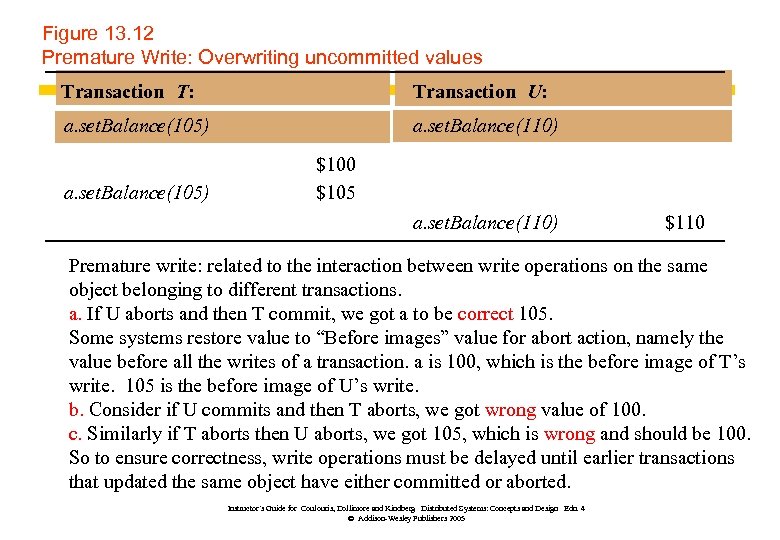

Figure 13. 12 Premature Write: Overwriting uncommitted values Transaction T: Transaction U: a. set. Balance(105) a. set. Balance(110) a. set. Balance(105) $100 $105 a. set. Balance(110) $110 Premature write: related to the interaction between write operations on the same object belonging to different transactions. a. If U aborts and then T commit, we got a to be correct 105. Some systems restore value to “Before images” value for abort action, namely the value before all the writes of a transaction. a is 100, which is the before image of T’s write. 105 is the before image of U’s write. b. Consider if U commits and then T aborts, we got wrong value of 100. c. Similarly if T aborts then U aborts, we got 105, which is wrong and should be 100. So to ensure correctness, write operations must be delayed until earlier transactions that updated the same object have either committed or aborted. Instructor’s Guide for Coulouris, Dollimore and Kindberg Distributed Systems: Concepts and Design Edn. 4 © Addison-Wesley Publishers 2005

Figure 13. 12 Premature Write: Overwriting uncommitted values Transaction T: Transaction U: a. set. Balance(105) a. set. Balance(110) a. set. Balance(105) $100 $105 a. set. Balance(110) $110 Premature write: related to the interaction between write operations on the same object belonging to different transactions. a. If U aborts and then T commit, we got a to be correct 105. Some systems restore value to “Before images” value for abort action, namely the value before all the writes of a transaction. a is 100, which is the before image of T’s write. 105 is the before image of U’s write. b. Consider if U commits and then T aborts, we got wrong value of 100. c. Similarly if T aborts then U aborts, we got 105, which is wrong and should be 100. So to ensure correctness, write operations must be delayed until earlier transactions that updated the same object have either committed or aborted. Instructor’s Guide for Coulouris, Dollimore and Kindberg Distributed Systems: Concepts and Design Edn. 4 © Addison-Wesley Publishers 2005

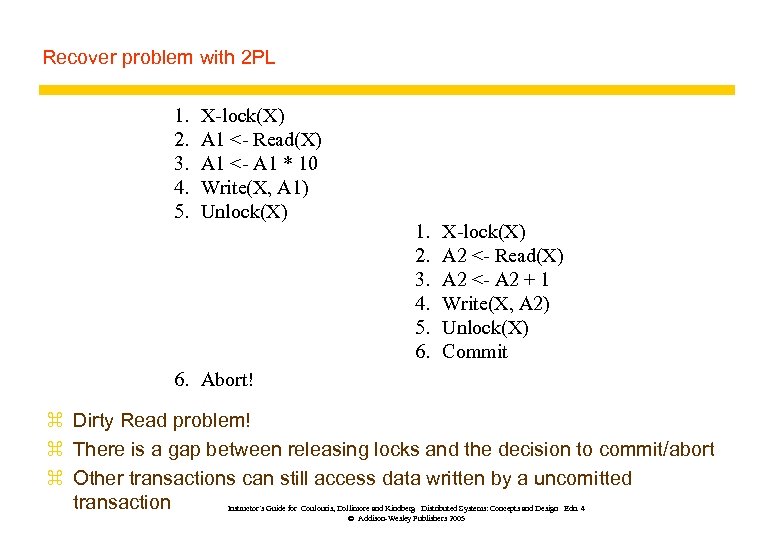

Recover problem with 2 PL 1. 2. 3. 4. 5. X-lock(X) A 1 <- Read(X) A 1 <- A 1 * 10 Write(X, A 1) Unlock(X) 1. 2. 3. 4. 5. 6. X-lock(X) A 2 <- Read(X) A 2 <- A 2 + 1 Write(X, A 2) Unlock(X) Commit 6. Abort! z Dirty Read problem! z There is a gap between releasing locks and the decision to commit/abort z Other transactions can still access data written by a uncomitted transaction Instructor’s Guide for Coulouris, Dollimore and Kindberg Distributed Systems: Concepts and Design Edn. 4 © Addison-Wesley Publishers 2005

Recover problem with 2 PL 1. 2. 3. 4. 5. X-lock(X) A 1 <- Read(X) A 1 <- A 1 * 10 Write(X, A 1) Unlock(X) 1. 2. 3. 4. 5. 6. X-lock(X) A 2 <- Read(X) A 2 <- A 2 + 1 Write(X, A 2) Unlock(X) Commit 6. Abort! z Dirty Read problem! z There is a gap between releasing locks and the decision to commit/abort z Other transactions can still access data written by a uncomitted transaction Instructor’s Guide for Coulouris, Dollimore and Kindberg Distributed Systems: Concepts and Design Edn. 4 © Addison-Wesley Publishers 2005

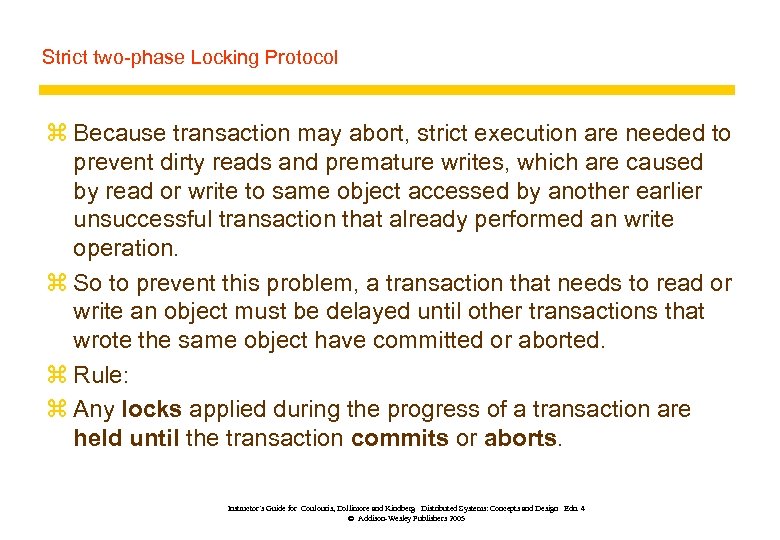

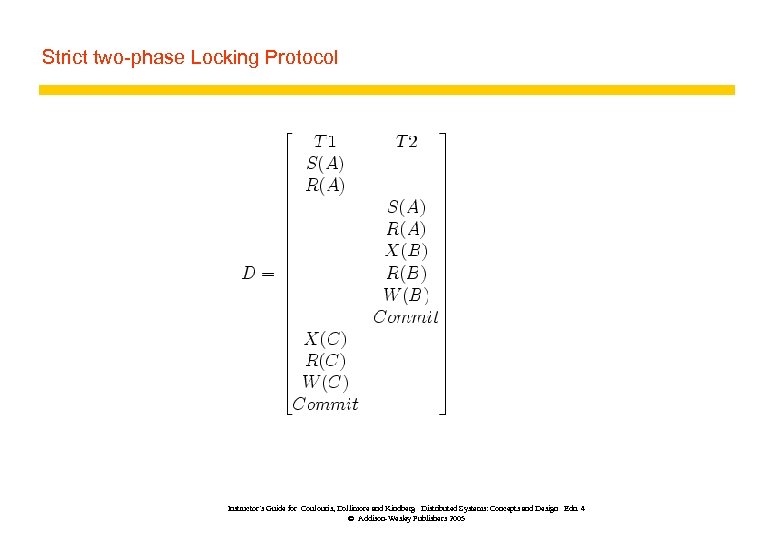

Strict two-phase Locking Protocol z Because transaction may abort, strict execution are needed to prevent dirty reads and premature writes, which are caused by read or write to same object accessed by another earlier unsuccessful transaction that already performed an write operation. z So to prevent this problem, a transaction that needs to read or write an object must be delayed until other transactions that wrote the same object have committed or aborted. z Rule: z Any locks applied during the progress of a transaction are held until the transaction commits or aborts. Instructor’s Guide for Coulouris, Dollimore and Kindberg Distributed Systems: Concepts and Design Edn. 4 © Addison-Wesley Publishers 2005

Strict two-phase Locking Protocol z Because transaction may abort, strict execution are needed to prevent dirty reads and premature writes, which are caused by read or write to same object accessed by another earlier unsuccessful transaction that already performed an write operation. z So to prevent this problem, a transaction that needs to read or write an object must be delayed until other transactions that wrote the same object have committed or aborted. z Rule: z Any locks applied during the progress of a transaction are held until the transaction commits or aborts. Instructor’s Guide for Coulouris, Dollimore and Kindberg Distributed Systems: Concepts and Design Edn. 4 © Addison-Wesley Publishers 2005

Strict two-phase Locking Protocol Instructor’s Guide for Coulouris, Dollimore and Kindberg Distributed Systems: Concepts and Design Edn. 4 © Addison-Wesley Publishers 2005

Strict two-phase Locking Protocol Instructor’s Guide for Coulouris, Dollimore and Kindberg Distributed Systems: Concepts and Design Edn. 4 © Addison-Wesley Publishers 2005

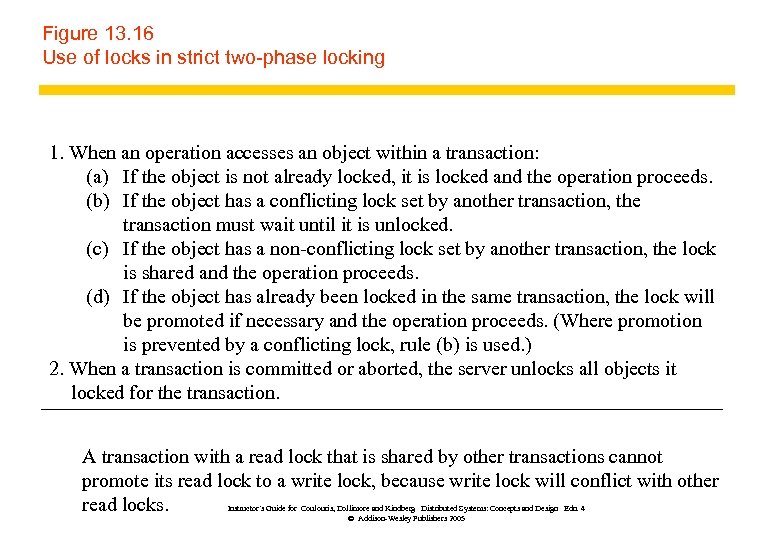

Figure 13. 16 Use of locks in strict two-phase locking 1. When an operation accesses an object within a transaction: (a) If the object is not already locked, it is locked and the operation proceeds. (b) If the object has a conflicting lock set by another transaction, the transaction must wait until it is unlocked. (c) If the object has a non-conflicting lock set by another transaction, the lock is shared and the operation proceeds. (d) If the object has already been locked in the same transaction, the lock will be promoted if necessary and the operation proceeds. (Where promotion is prevented by a conflicting lock, rule (b) is used. ) 2. When a transaction is committed or aborted, the server unlocks all objects it locked for the transaction. A transaction with a read lock that is shared by other transactions cannot promote its read lock to a write lock, because write lock will conflict with other read locks. Instructor’s Guide for Coulouris, Dollimore and Kindberg Distributed Systems: Concepts and Design Edn. 4 © Addison-Wesley Publishers 2005

Figure 13. 16 Use of locks in strict two-phase locking 1. When an operation accesses an object within a transaction: (a) If the object is not already locked, it is locked and the operation proceeds. (b) If the object has a conflicting lock set by another transaction, the transaction must wait until it is unlocked. (c) If the object has a non-conflicting lock set by another transaction, the lock is shared and the operation proceeds. (d) If the object has already been locked in the same transaction, the lock will be promoted if necessary and the operation proceeds. (Where promotion is prevented by a conflicting lock, rule (b) is used. ) 2. When a transaction is committed or aborted, the server unlocks all objects it locked for the transaction. A transaction with a read lock that is shared by other transactions cannot promote its read lock to a write lock, because write lock will conflict with other read locks. Instructor’s Guide for Coulouris, Dollimore and Kindberg Distributed Systems: Concepts and Design Edn. 4 © Addison-Wesley Publishers 2005

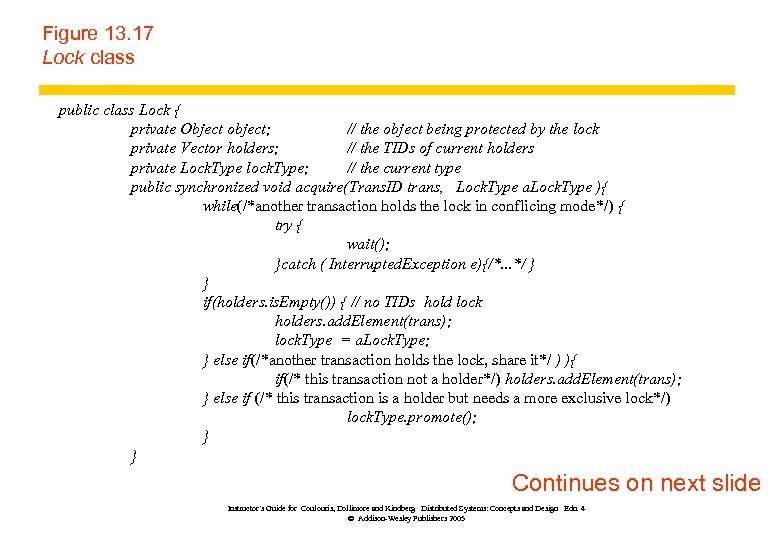

Figure 13. 17 Lock class public class Lock { private Object object; // the object being protected by the lock private Vector holders; // the TIDs of current holders private Lock. Type lock. Type; // the current type public synchronized void acquire(Trans. ID trans, Lock. Type a. Lock. Type ){ while(/*another transaction holds the lock in conflicing mode*/) { try { wait(); }catch ( Interrupted. Exception e){/*. . . */ } } if(holders. is. Empty()) { // no TIDs hold lock holders. add. Element(trans); lock. Type = a. Lock. Type; } else if(/*another transaction holds the lock, share it*/ ) ){ if(/* this transaction not a holder*/) holders. add. Element(trans); } else if (/* this transaction is a holder but needs a more exclusive lock*/) lock. Type. promote(); } } Continues on next slide Instructor’s Guide for Coulouris, Dollimore and Kindberg Distributed Systems: Concepts and Design Edn. 4 © Addison-Wesley Publishers 2005

Figure 13. 17 Lock class public class Lock { private Object object; // the object being protected by the lock private Vector holders; // the TIDs of current holders private Lock. Type lock. Type; // the current type public synchronized void acquire(Trans. ID trans, Lock. Type a. Lock. Type ){ while(/*another transaction holds the lock in conflicing mode*/) { try { wait(); }catch ( Interrupted. Exception e){/*. . . */ } } if(holders. is. Empty()) { // no TIDs hold lock holders. add. Element(trans); lock. Type = a. Lock. Type; } else if(/*another transaction holds the lock, share it*/ ) ){ if(/* this transaction not a holder*/) holders. add. Element(trans); } else if (/* this transaction is a holder but needs a more exclusive lock*/) lock. Type. promote(); } } Continues on next slide Instructor’s Guide for Coulouris, Dollimore and Kindberg Distributed Systems: Concepts and Design Edn. 4 © Addison-Wesley Publishers 2005

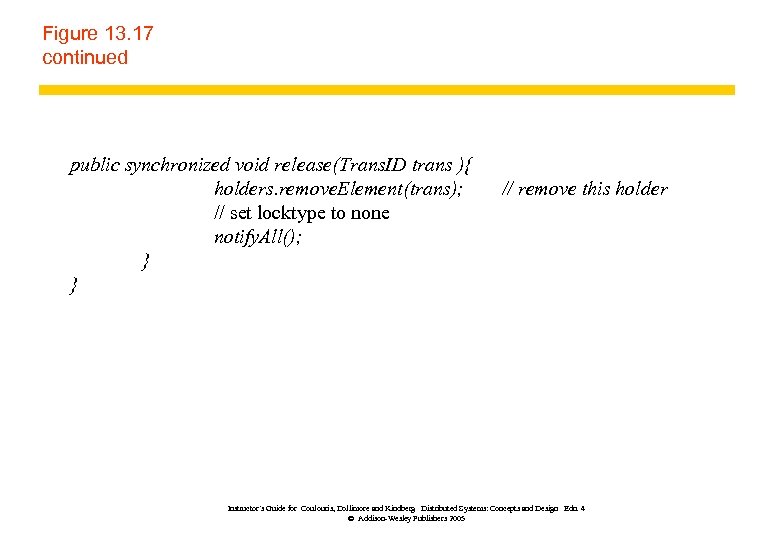

Figure 13. 17 continued public synchronized void release(Trans. ID trans ){ holders. remove. Element(trans); // set locktype to none notify. All(); } } // remove this holder Instructor’s Guide for Coulouris, Dollimore and Kindberg Distributed Systems: Concepts and Design Edn. 4 © Addison-Wesley Publishers 2005

Figure 13. 17 continued public synchronized void release(Trans. ID trans ){ holders. remove. Element(trans); // set locktype to none notify. All(); } } // remove this holder Instructor’s Guide for Coulouris, Dollimore and Kindberg Distributed Systems: Concepts and Design Edn. 4 © Addison-Wesley Publishers 2005

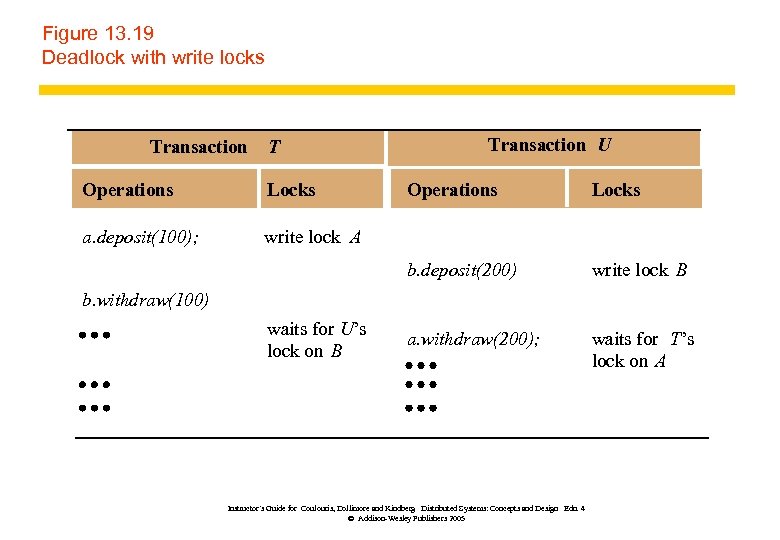

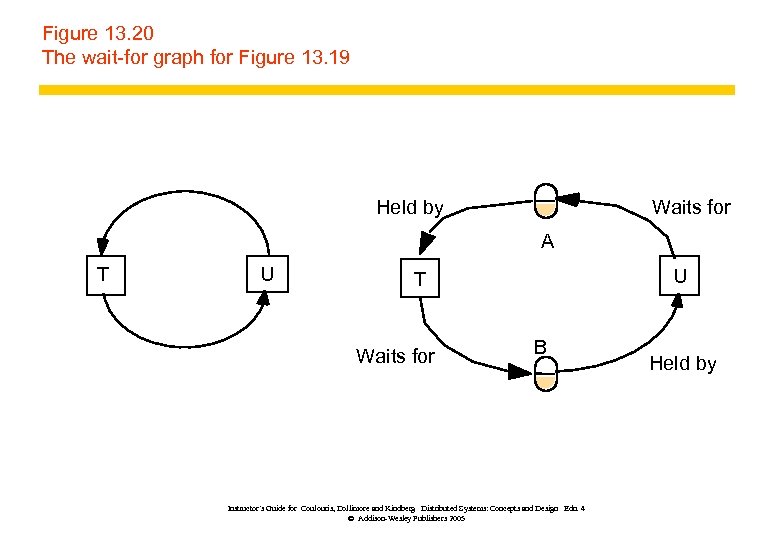

Figure 13. 19 Deadlock with write locks Transaction T Operations Locks a. deposit(100); Transaction U Operations Locks write lock A b. deposit(200) write lock B a. withdraw(200); waits for T’s lock on A b. withdraw(100) waits for U’s lock on B Instructor’s Guide for Coulouris, Dollimore and Kindberg Distributed Systems: Concepts and Design Edn. 4 © Addison-Wesley Publishers 2005

Figure 13. 19 Deadlock with write locks Transaction T Operations Locks a. deposit(100); Transaction U Operations Locks write lock A b. deposit(200) write lock B a. withdraw(200); waits for T’s lock on A b. withdraw(100) waits for U’s lock on B Instructor’s Guide for Coulouris, Dollimore and Kindberg Distributed Systems: Concepts and Design Edn. 4 © Addison-Wesley Publishers 2005

Figure 13. 20 The wait-for graph for Figure 13. 19 Held by Waits for A T U U T Waits for B Instructor’s Guide for Coulouris, Dollimore and Kindberg Distributed Systems: Concepts and Design Edn. 4 © Addison-Wesley Publishers 2005 Held by

Figure 13. 20 The wait-for graph for Figure 13. 19 Held by Waits for A T U U T Waits for B Instructor’s Guide for Coulouris, Dollimore and Kindberg Distributed Systems: Concepts and Design Edn. 4 © Addison-Wesley Publishers 2005 Held by

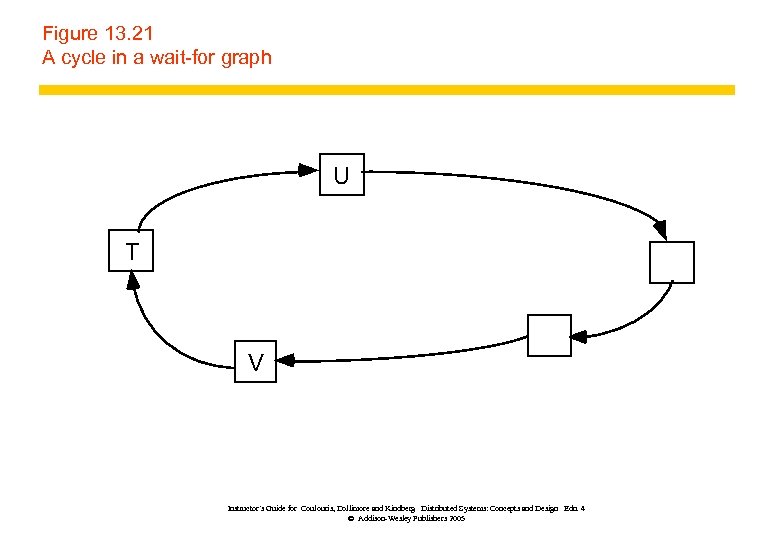

Figure 13. 21 A cycle in a wait-for graph U T V Instructor’s Guide for Coulouris, Dollimore and Kindberg Distributed Systems: Concepts and Design Edn. 4 © Addison-Wesley Publishers 2005

Figure 13. 21 A cycle in a wait-for graph U T V Instructor’s Guide for Coulouris, Dollimore and Kindberg Distributed Systems: Concepts and Design Edn. 4 © Addison-Wesley Publishers 2005

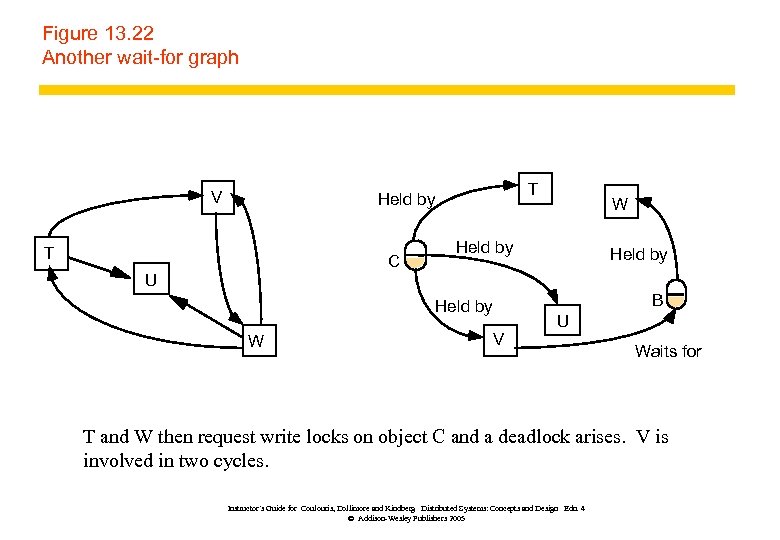

Figure 13. 22 Another wait-for graph V T Held by T C W Held by U B Held by W V U Waits for T and W then request write locks on object C and a deadlock arises. V is involved in two cycles. Instructor’s Guide for Coulouris, Dollimore and Kindberg Distributed Systems: Concepts and Design Edn. 4 © Addison-Wesley Publishers 2005

Figure 13. 22 Another wait-for graph V T Held by T C W Held by U B Held by W V U Waits for T and W then request write locks on object C and a deadlock arises. V is involved in two cycles. Instructor’s Guide for Coulouris, Dollimore and Kindberg Distributed Systems: Concepts and Design Edn. 4 © Addison-Wesley Publishers 2005

Deadlock Prevention z Deadlock prevention: y. Simple way is to lock all of the objects used by a transaction when it starts. It should be done as an atomic action to prevent deadlock. a. inefficient, say lock an object you only need for short period of time. b. Hard to predict what objects a transaction will require. y. Judge if system can remain in a Safe state by satisfying a certain resource request. Banker’s algorithm. y. Order the objects in certain order. Acquiring the locks need to follow this certain order. Instructor’s Guide for Coulouris, Dollimore and Kindberg Distributed Systems: Concepts and Design Edn. 4 © Addison-Wesley Publishers 2005

Deadlock Prevention z Deadlock prevention: y. Simple way is to lock all of the objects used by a transaction when it starts. It should be done as an atomic action to prevent deadlock. a. inefficient, say lock an object you only need for short period of time. b. Hard to predict what objects a transaction will require. y. Judge if system can remain in a Safe state by satisfying a certain resource request. Banker’s algorithm. y. Order the objects in certain order. Acquiring the locks need to follow this certain order. Instructor’s Guide for Coulouris, Dollimore and Kindberg Distributed Systems: Concepts and Design Edn. 4 © Addison-Wesley Publishers 2005

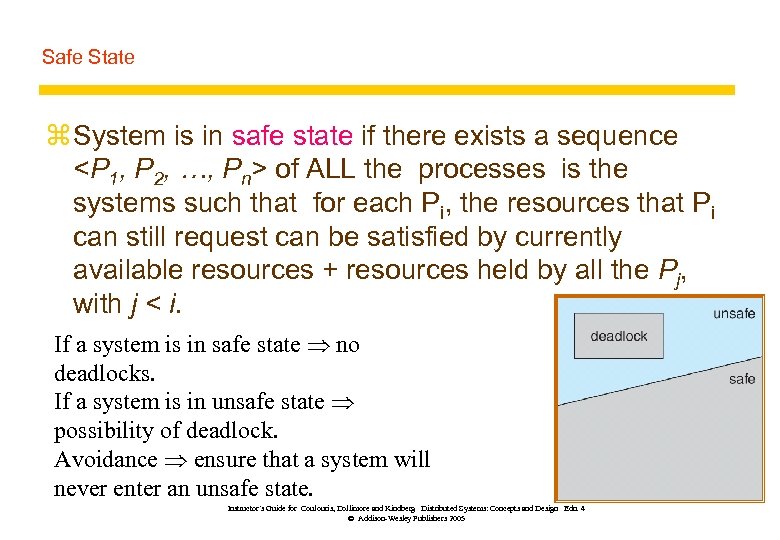

Safe State z System is in safe state if there exists a sequence

Safe State z System is in safe state if there exists a sequence

of ALL the processes is the systems such that for each Pi, the resources that Pi can still request can be satisfied by currently available resources + resources held by all the Pj, with j < i. If a system is in safe state no deadlocks. If a system is in unsafe state possibility of deadlock. Avoidance ensure that a system will never enter an unsafe state. Instructor’s Guide for Coulouris, Dollimore and Kindberg Distributed Systems: Concepts and Design Edn. 4 © Addison-Wesley Publishers 2005

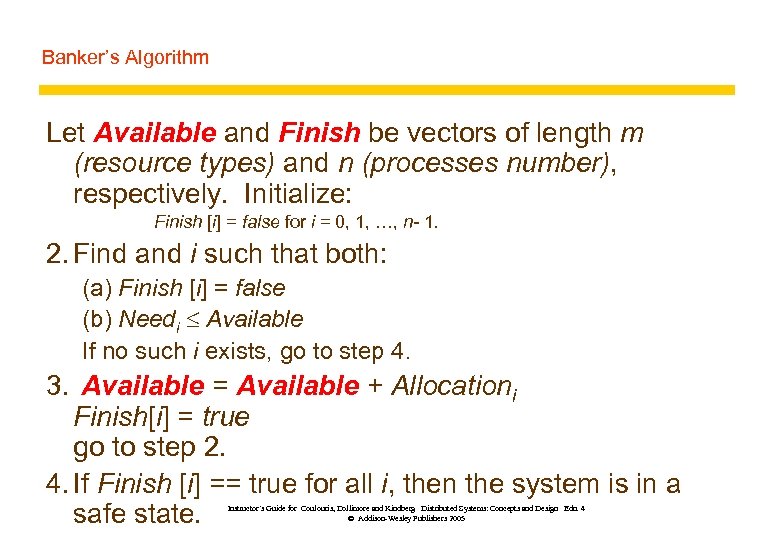

Banker’s Algorithm Let Available and Finish be vectors of length m (resource types) and n (processes number), respectively. Initialize: Finish [i] = false for i = 0, 1, …, n- 1. 2. Find and i such that both: (a) Finish [i] = false (b) Needi Available If no such i exists, go to step 4. 3. Available = Available + Allocationi Finish[i] = true go to step 2. 4. If Finish [i] == true for all i, then the system is in a safe state. Instructor’s Guide for Coulouris, Dollimore and Kindberg Distributed Systems: Concepts and Design Edn. 4 © Addison-Wesley Publishers 2005

Banker’s Algorithm Let Available and Finish be vectors of length m (resource types) and n (processes number), respectively. Initialize: Finish [i] = false for i = 0, 1, …, n- 1. 2. Find and i such that both: (a) Finish [i] = false (b) Needi Available If no such i exists, go to step 4. 3. Available = Available + Allocationi Finish[i] = true go to step 2. 4. If Finish [i] == true for all i, then the system is in a safe state. Instructor’s Guide for Coulouris, Dollimore and Kindberg Distributed Systems: Concepts and Design Edn. 4 © Addison-Wesley Publishers 2005

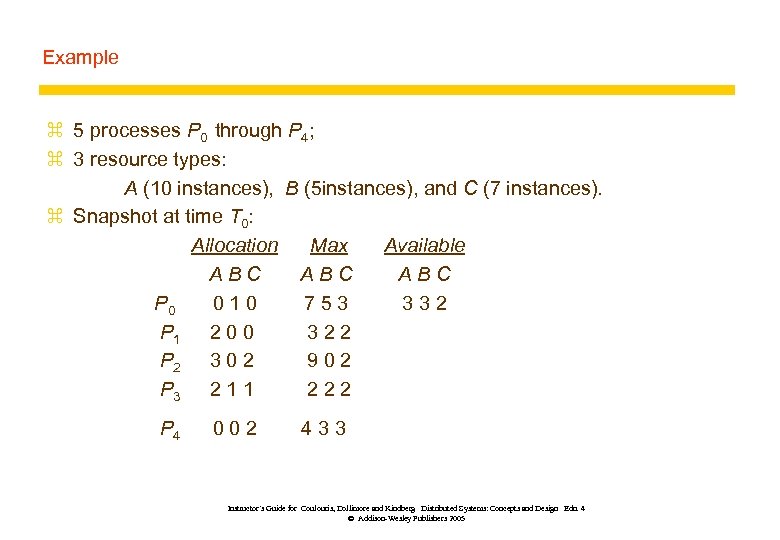

Example z 5 processes P 0 through P 4; z 3 resource types: A (10 instances), B (5 instances), and C (7 instances). z Snapshot at time T 0: Allocation Max Available ABC ABC P 0 010 753 332 P 1 2 0 0 322 P 2 3 0 2 902 P 3 2 1 1 222 P 4 002 433 Instructor’s Guide for Coulouris, Dollimore and Kindberg Distributed Systems: Concepts and Design Edn. 4 © Addison-Wesley Publishers 2005

Example z 5 processes P 0 through P 4; z 3 resource types: A (10 instances), B (5 instances), and C (7 instances). z Snapshot at time T 0: Allocation Max Available ABC ABC P 0 010 753 332 P 1 2 0 0 322 P 2 3 0 2 902 P 3 2 1 1 222 P 4 002 433 Instructor’s Guide for Coulouris, Dollimore and Kindberg Distributed Systems: Concepts and Design Edn. 4 © Addison-Wesley Publishers 2005

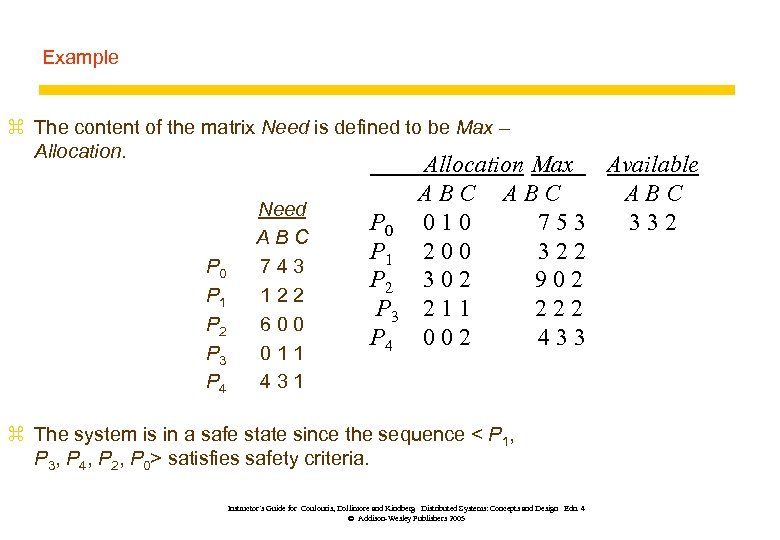

Example z The content of the matrix Need is defined to be Max – Allocation. P 0 P 1 P 2 P 3 P 4 Need ABC 743 122 600 011 431 P 0 P 1 P 2 P 3 P 4 Allocation Max Available ABC ABC 010 753 332 200 322 302 902 211 222 002 433 z The system is in a safe state since the sequence < P 1, P 3, P 4, P 2, P 0> satisfies safety criteria. Instructor’s Guide for Coulouris, Dollimore and Kindberg Distributed Systems: Concepts and Design Edn. 4 © Addison-Wesley Publishers 2005

Example z The content of the matrix Need is defined to be Max – Allocation. P 0 P 1 P 2 P 3 P 4 Need ABC 743 122 600 011 431 P 0 P 1 P 2 P 3 P 4 Allocation Max Available ABC ABC 010 753 332 200 322 302 902 211 222 002 433 z The system is in a safe state since the sequence < P 1, P 3, P 4, P 2, P 0> satisfies safety criteria. Instructor’s Guide for Coulouris, Dollimore and Kindberg Distributed Systems: Concepts and Design Edn. 4 © Addison-Wesley Publishers 2005

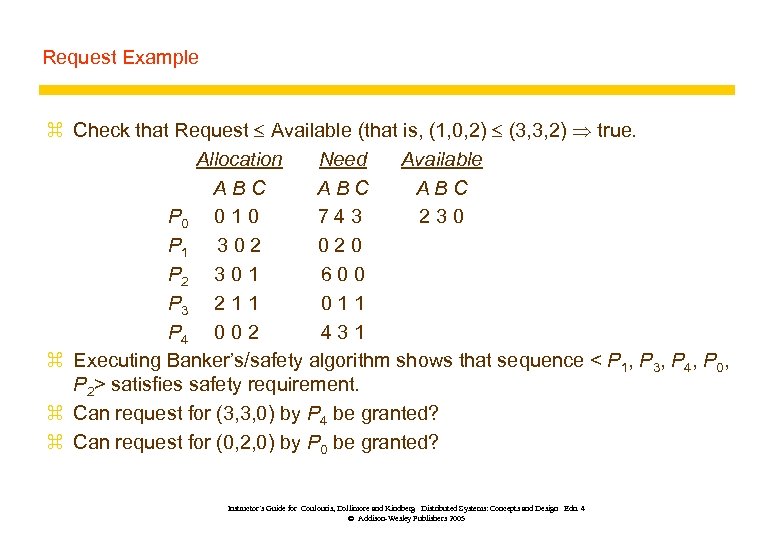

Request Example z Check that Request Available (that is, (1, 0, 2) (3, 3, 2) true. Allocation Need Available ABC ABC P 0 0 1 0 743 230 P 1 3 0 2 020 P 2 3 0 1 600 P 3 2 1 1 011 P 4 0 0 2 431 z Executing Banker’s/safety algorithm shows that sequence < P 1, P 3, P 4, P 0, P 2> satisfies safety requirement. z Can request for (3, 3, 0) by P 4 be granted? z Can request for (0, 2, 0) by P 0 be granted? Instructor’s Guide for Coulouris, Dollimore and Kindberg Distributed Systems: Concepts and Design Edn. 4 © Addison-Wesley Publishers 2005

Request Example z Check that Request Available (that is, (1, 0, 2) (3, 3, 2) true. Allocation Need Available ABC ABC P 0 0 1 0 743 230 P 1 3 0 2 020 P 2 3 0 1 600 P 3 2 1 1 011 P 4 0 0 2 431 z Executing Banker’s/safety algorithm shows that sequence < P 1, P 3, P 4, P 0, P 2> satisfies safety requirement. z Can request for (3, 3, 0) by P 4 be granted? z Can request for (0, 2, 0) by P 0 be granted? Instructor’s Guide for Coulouris, Dollimore and Kindberg Distributed Systems: Concepts and Design Edn. 4 © Addison-Wesley Publishers 2005

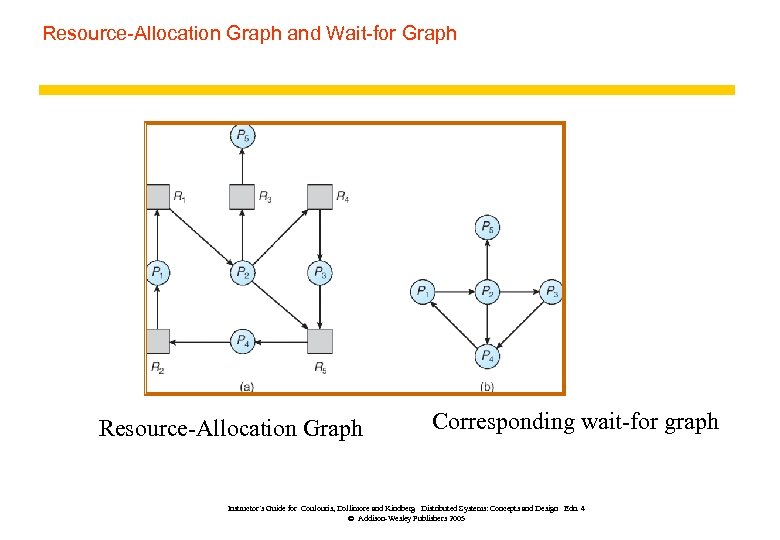

Resource-Allocation Graph and Wait-for Graph Resource-Allocation Graph Corresponding wait-for graph Instructor’s Guide for Coulouris, Dollimore and Kindberg Distributed Systems: Concepts and Design Edn. 4 © Addison-Wesley Publishers 2005

Resource-Allocation Graph and Wait-for Graph Resource-Allocation Graph Corresponding wait-for graph Instructor’s Guide for Coulouris, Dollimore and Kindberg Distributed Systems: Concepts and Design Edn. 4 © Addison-Wesley Publishers 2005

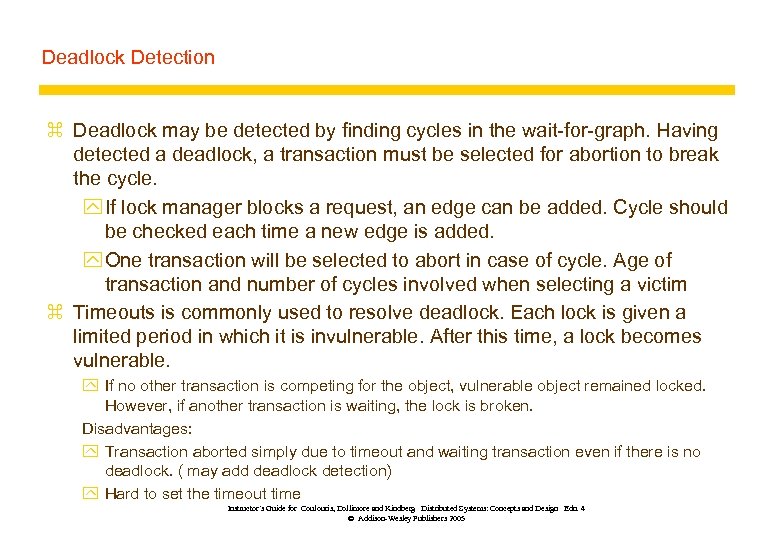

Deadlock Detection z Deadlock may be detected by finding cycles in the wait-for-graph. Having detected a deadlock, a transaction must be selected for abortion to break the cycle. y If lock manager blocks a request, an edge can be added. Cycle should be checked each time a new edge is added. y One transaction will be selected to abort in case of cycle. Age of transaction and number of cycles involved when selecting a victim z Timeouts is commonly used to resolve deadlock. Each lock is given a limited period in which it is invulnerable. After this time, a lock becomes vulnerable. y If no other transaction is competing for the object, vulnerable object remained locked. However, if another transaction is waiting, the lock is broken. Disadvantages: y Transaction aborted simply due to timeout and waiting transaction even if there is no deadlock. ( may add deadlock detection) y Hard to set the timeout time Instructor’s Guide for Coulouris, Dollimore and Kindberg Distributed Systems: Concepts and Design Edn. 4 © Addison-Wesley Publishers 2005

Deadlock Detection z Deadlock may be detected by finding cycles in the wait-for-graph. Having detected a deadlock, a transaction must be selected for abortion to break the cycle. y If lock manager blocks a request, an edge can be added. Cycle should be checked each time a new edge is added. y One transaction will be selected to abort in case of cycle. Age of transaction and number of cycles involved when selecting a victim z Timeouts is commonly used to resolve deadlock. Each lock is given a limited period in which it is invulnerable. After this time, a lock becomes vulnerable. y If no other transaction is competing for the object, vulnerable object remained locked. However, if another transaction is waiting, the lock is broken. Disadvantages: y Transaction aborted simply due to timeout and waiting transaction even if there is no deadlock. ( may add deadlock detection) y Hard to set the timeout time Instructor’s Guide for Coulouris, Dollimore and Kindberg Distributed Systems: Concepts and Design Edn. 4 © Addison-Wesley Publishers 2005

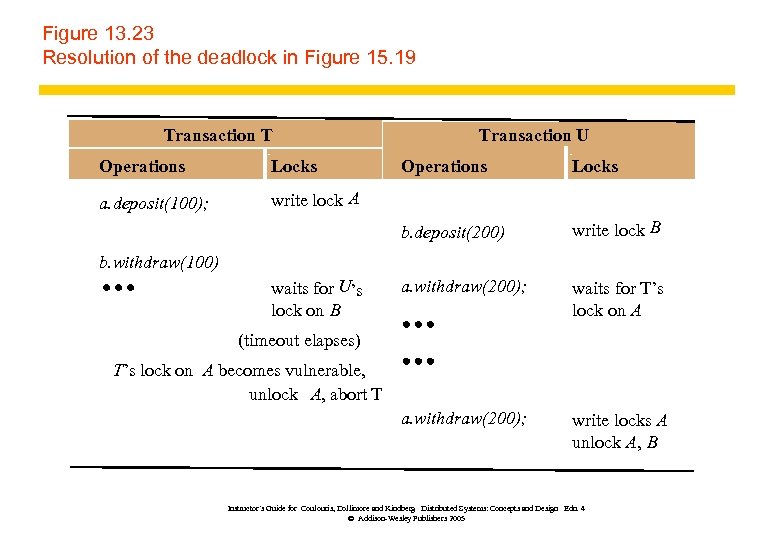

Figure 13. 23 Resolution of the deadlock in Figure 15. 19 Transaction T Operations Locks a. deposit(100); Transaction U Operations Locks write lock A b. deposit(200) write lock B a. withdraw(200); waits for T’s lock on A a. withdraw(200); write locks A unlock A, B b. withdraw(100) waits for U’s lock on B (timeout elapses) T’s lock on A becomes vulnerable, unlock A, abort T Instructor’s Guide for Coulouris, Dollimore and Kindberg Distributed Systems: Concepts and Design Edn. 4 © Addison-Wesley Publishers 2005

Figure 13. 23 Resolution of the deadlock in Figure 15. 19 Transaction T Operations Locks a. deposit(100); Transaction U Operations Locks write lock A b. deposit(200) write lock B a. withdraw(200); waits for T’s lock on A a. withdraw(200); write locks A unlock A, B b. withdraw(100) waits for U’s lock on B (timeout elapses) T’s lock on A becomes vulnerable, unlock A, abort T Instructor’s Guide for Coulouris, Dollimore and Kindberg Distributed Systems: Concepts and Design Edn. 4 © Addison-Wesley Publishers 2005

![Optimistic Concurrency Control z Kung and Robinson [1981] identified a number of inherent disadvantages Optimistic Concurrency Control z Kung and Robinson [1981] identified a number of inherent disadvantages](https://present5.com/presentation/b5c43bb41fde7d7a2745763fe2613ef9/image-53.jpg) Optimistic Concurrency Control z Kung and Robinson [1981] identified a number of inherent disadvantages of locking and proposed an alternative optimistic approach to the serialization of transaction that avoids these drawbacks. Disadvantages of lock-based: y. Lock maintenance represents an overhead that is not present in systems that do not support concurrent access to shared data. Locking sometimes are only needed for some cases with low probabilities. y. The use of lock can result in deadlock. Deadlock prevention reduces concurrency severely. The use of timeout and deadlock detection is not ideal for interactive programs. y. To avoid cascading aborts, locks cannot be released until the end of the transaction. This may reduce the potential for concurrency. Instructor’s Guide for Coulouris, Dollimore and Kindberg Distributed Systems: Concepts and Design Edn. 4 © Addison-Wesley Publishers 2005

Optimistic Concurrency Control z Kung and Robinson [1981] identified a number of inherent disadvantages of locking and proposed an alternative optimistic approach to the serialization of transaction that avoids these drawbacks. Disadvantages of lock-based: y. Lock maintenance represents an overhead that is not present in systems that do not support concurrent access to shared data. Locking sometimes are only needed for some cases with low probabilities. y. The use of lock can result in deadlock. Deadlock prevention reduces concurrency severely. The use of timeout and deadlock detection is not ideal for interactive programs. y. To avoid cascading aborts, locks cannot be released until the end of the transaction. This may reduce the potential for concurrency. Instructor’s Guide for Coulouris, Dollimore and Kindberg Distributed Systems: Concepts and Design Edn. 4 © Addison-Wesley Publishers 2005

Optimistic Concurrency Control z It is based on observation that, in most applications, the likelihood of two clients’ transactions accessing the same object is low. Transactions are allowed to proceed as though there were no possibility of conflict with other transactions until the client completes its task and issues a close. Transaction request. z When conflict arises, some transaction is generally aborted and will need to be restarted by the client. Instructor’s Guide for Coulouris, Dollimore and Kindberg Distributed Systems: Concepts and Design Edn. 4 © Addison-Wesley Publishers 2005

Optimistic Concurrency Control z It is based on observation that, in most applications, the likelihood of two clients’ transactions accessing the same object is low. Transactions are allowed to proceed as though there were no possibility of conflict with other transactions until the client completes its task and issues a close. Transaction request. z When conflict arises, some transaction is generally aborted and will need to be restarted by the client. Instructor’s Guide for Coulouris, Dollimore and Kindberg Distributed Systems: Concepts and Design Edn. 4 © Addison-Wesley Publishers 2005

Optimistic Concurrency Control z Each transaction has the following phases: y. Working phase: Each transaction has a tentative version of each of the objects that it updates. This is a copy of the most recently committed version of the object. The tentative version allows the transaction to abort with no effect on the object, either during the working phase or if it fails validation due to other conflicting transaction. Several different tentative values of the same object may coexist. In addition, two records are kept of the objects accessed within a transaction, a read set and a write set containing all objects either read or written by this transaction. Read are performed on committed version ( no dirty read can occur) and write record the new values of the object as tentative values which are invisible to other transactions. Instructor’s Guide for Coulouris, Dollimore and Kindberg Distributed Systems: Concepts and Design Edn. 4 © Addison-Wesley Publishers 2005

Optimistic Concurrency Control z Each transaction has the following phases: y. Working phase: Each transaction has a tentative version of each of the objects that it updates. This is a copy of the most recently committed version of the object. The tentative version allows the transaction to abort with no effect on the object, either during the working phase or if it fails validation due to other conflicting transaction. Several different tentative values of the same object may coexist. In addition, two records are kept of the objects accessed within a transaction, a read set and a write set containing all objects either read or written by this transaction. Read are performed on committed version ( no dirty read can occur) and write record the new values of the object as tentative values which are invisible to other transactions. Instructor’s Guide for Coulouris, Dollimore and Kindberg Distributed Systems: Concepts and Design Edn. 4 © Addison-Wesley Publishers 2005

Optimistic Concurrency Control y. Validation phase: When close. Transaction request is received, the transaction is validated to establish whether or not its operations on objects conflict with operations of other transaction on the same objects. If successful, then the transaction can commit. If fails, then either the current transaction or those with which it conflicts will need to be aborted. y. Update phase: If a transaction is validated, all of the changes recorded in its tentative versions are made permanent. Read-only transaction can commit immediately after passing validation. Write transactions are ready to commit once the tentative versions have been recorded in permanent storage. Instructor’s Guide for Coulouris, Dollimore and Kindberg Distributed Systems: Concepts and Design Edn. 4 © Addison-Wesley Publishers 2005

Optimistic Concurrency Control y. Validation phase: When close. Transaction request is received, the transaction is validated to establish whether or not its operations on objects conflict with operations of other transaction on the same objects. If successful, then the transaction can commit. If fails, then either the current transaction or those with which it conflicts will need to be aborted. y. Update phase: If a transaction is validated, all of the changes recorded in its tentative versions are made permanent. Read-only transaction can commit immediately after passing validation. Write transactions are ready to commit once the tentative versions have been recorded in permanent storage. Instructor’s Guide for Coulouris, Dollimore and Kindberg Distributed Systems: Concepts and Design Edn. 4 © Addison-Wesley Publishers 2005

Validation of Transactions z Validation uses the read-write conflict rules to ensure that the scheduling of a particular transaction is serially equivalent with respect to all other overlapping transactions - that is, any transactions that had not yet committed at the time this transaction started. Each transaction is assigned a number when it enters the validation phase (when the client issues a close. Transaction). Such number defines its position in time. A transaction always finishes its working phase after all transactions with lower numbers. That is, a transaction with the number Ti always precedes a transaction with number Tj if i < j. Instructor’s Guide for Coulouris, Dollimore and Kindberg Distributed Systems: Concepts and Design Edn. 4 © Addison-Wesley Publishers 2005

Validation of Transactions z Validation uses the read-write conflict rules to ensure that the scheduling of a particular transaction is serially equivalent with respect to all other overlapping transactions - that is, any transactions that had not yet committed at the time this transaction started. Each transaction is assigned a number when it enters the validation phase (when the client issues a close. Transaction). Such number defines its position in time. A transaction always finishes its working phase after all transactions with lower numbers. That is, a transaction with the number Ti always precedes a transaction with number Tj if i < j. Instructor’s Guide for Coulouris, Dollimore and Kindberg Distributed Systems: Concepts and Design Edn. 4 © Addison-Wesley Publishers 2005

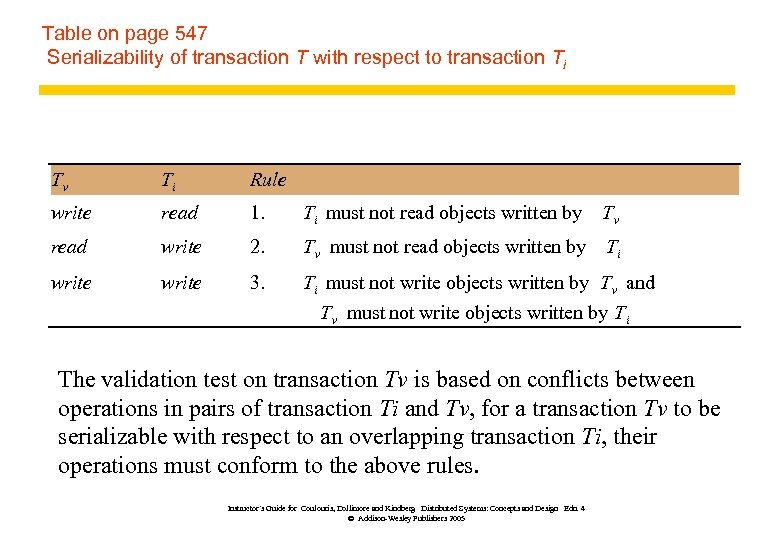

Table on page 547 Serializability of transaction T with respect to transaction Ti Tv Ti Rule write read 1. Ti must not read objects written by Tv read write 2. Tv must not read objects written by Ti write 3. Ti must not write objects written by Tv and Tv must not write objects written by Ti The validation test on transaction Tv is based on conflicts between operations in pairs of transaction Ti and Tv, for a transaction Tv to be serializable with respect to an overlapping transaction Ti, their operations must conform to the above rules. Instructor’s Guide for Coulouris, Dollimore and Kindberg Distributed Systems: Concepts and Design Edn. 4 © Addison-Wesley Publishers 2005

Table on page 547 Serializability of transaction T with respect to transaction Ti Tv Ti Rule write read 1. Ti must not read objects written by Tv read write 2. Tv must not read objects written by Ti write 3. Ti must not write objects written by Tv and Tv must not write objects written by Ti The validation test on transaction Tv is based on conflicts between operations in pairs of transaction Ti and Tv, for a transaction Tv to be serializable with respect to an overlapping transaction Ti, their operations must conform to the above rules. Instructor’s Guide for Coulouris, Dollimore and Kindberg Distributed Systems: Concepts and Design Edn. 4 © Addison-Wesley Publishers 2005

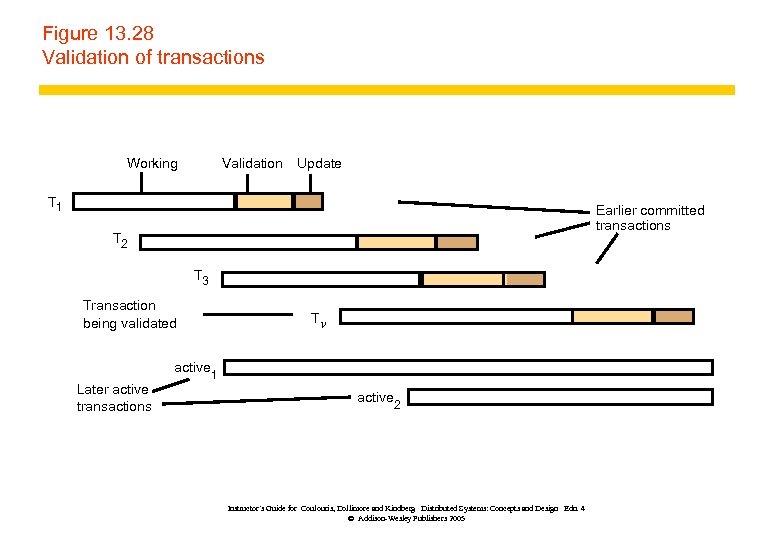

Figure 13. 28 Validation of transactions Working Validation Update T 1 Earlier committed transactions T 2 T 3 Transaction being validated active Later active transactions Tv 1 active 2 Instructor’s Guide for Coulouris, Dollimore and Kindberg Distributed Systems: Concepts and Design Edn. 4 © Addison-Wesley Publishers 2005

Figure 13. 28 Validation of transactions Working Validation Update T 1 Earlier committed transactions T 2 T 3 Transaction being validated active Later active transactions Tv 1 active 2 Instructor’s Guide for Coulouris, Dollimore and Kindberg Distributed Systems: Concepts and Design Edn. 4 © Addison-Wesley Publishers 2005

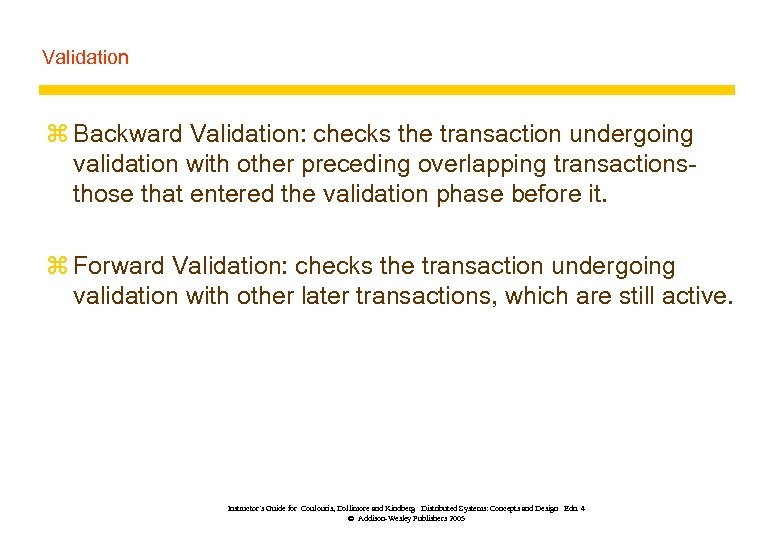

Validation z Backward Validation: checks the transaction undergoing validation with other preceding overlapping transactionsthose that entered the validation phase before it. z Forward Validation: checks the transaction undergoing validation with other later transactions, which are still active. Instructor’s Guide for Coulouris, Dollimore and Kindberg Distributed Systems: Concepts and Design Edn. 4 © Addison-Wesley Publishers 2005

Validation z Backward Validation: checks the transaction undergoing validation with other preceding overlapping transactionsthose that entered the validation phase before it. z Forward Validation: checks the transaction undergoing validation with other later transactions, which are still active. Instructor’s Guide for Coulouris, Dollimore and Kindberg Distributed Systems: Concepts and Design Edn. 4 © Addison-Wesley Publishers 2005

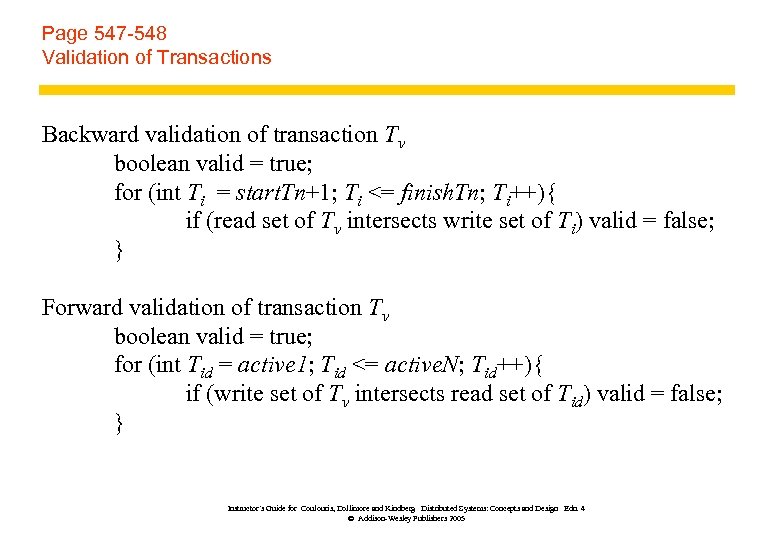

Page 547 -548 Validation of Transactions Backward validation of transaction Tv boolean valid = true; for (int Ti = start. Tn+1; Ti <= finish. Tn; Ti++){ if (read set of Tv intersects write set of Ti) valid = false; } Forward validation of transaction Tv boolean valid = true; for (int Tid = active 1; Tid <= active. N; Tid++){ if (write set of Tv intersects read set of Tid) valid = false; } Instructor’s Guide for Coulouris, Dollimore and Kindberg Distributed Systems: Concepts and Design Edn. 4 © Addison-Wesley Publishers 2005

Page 547 -548 Validation of Transactions Backward validation of transaction Tv boolean valid = true; for (int Ti = start. Tn+1; Ti <= finish. Tn; Ti++){ if (read set of Tv intersects write set of Ti) valid = false; } Forward validation of transaction Tv boolean valid = true; for (int Tid = active 1; Tid <= active. N; Tid++){ if (write set of Tv intersects read set of Tid) valid = false; } Instructor’s Guide for Coulouris, Dollimore and Kindberg Distributed Systems: Concepts and Design Edn. 4 © Addison-Wesley Publishers 2005

Timestamp based concurrency control z Each transaction is assigned a unique timestamp value when it starts, which defines its position in the time sequence of transactions. z The basic timestamp ordering rule is based on operation conflicts and is very simple: y. A transaction’s request to write an object is valid only if that object was last read and written by earlier transactions. A transaction’s request to read an object is valid only if that object was last written by an earlier transaction. y. This rule assume that there is only one version of each object and restrict access to one transaction at a time. Instructor’s Guide for Coulouris, Dollimore and Kindberg Distributed Systems: Concepts and Design Edn. 4 © Addison-Wesley Publishers 2005

Timestamp based concurrency control z Each transaction is assigned a unique timestamp value when it starts, which defines its position in the time sequence of transactions. z The basic timestamp ordering rule is based on operation conflicts and is very simple: y. A transaction’s request to write an object is valid only if that object was last read and written by earlier transactions. A transaction’s request to read an object is valid only if that object was last written by an earlier transaction. y. This rule assume that there is only one version of each object and restrict access to one transaction at a time. Instructor’s Guide for Coulouris, Dollimore and Kindberg Distributed Systems: Concepts and Design Edn. 4 © Addison-Wesley Publishers 2005

Timestamp ordering z Timestamps may be assigned from the server’s clock or a counter that is incremented whenever a timestamp value is issued. z Each object has a write timestamp and a set of tentative versions, each of which has a write timestamp associated with it; and a set of read timestamps. z The write timestamps of the committed object is earlier than that of any of its tentative versions, and the set of read timestamps can be represented by its maximum member. Instructor’s Guide for Coulouris, Dollimore and Kindberg Distributed Systems: Concepts and Design Edn. 4 © Addison-Wesley Publishers 2005

Timestamp ordering z Timestamps may be assigned from the server’s clock or a counter that is incremented whenever a timestamp value is issued. z Each object has a write timestamp and a set of tentative versions, each of which has a write timestamp associated with it; and a set of read timestamps. z The write timestamps of the committed object is earlier than that of any of its tentative versions, and the set of read timestamps can be represented by its maximum member. Instructor’s Guide for Coulouris, Dollimore and Kindberg Distributed Systems: Concepts and Design Edn. 4 © Addison-Wesley Publishers 2005

Timestamp ordering z Whenever a transaction’s write operation on an object is accepted, the server creates a new tentative version of the object with write timestamp set to the transaction timestamp. Whenever a read operation is accepted, the timestamp of the transaction is added to its set of read timestamps. z When a transaction is committed, the values of the tentative version become the values of the object, and the timestamps of the tentative version become the write timestamp of the corresponding object. Instructor’s Guide for Coulouris, Dollimore and Kindberg Distributed Systems: Concepts and Design Edn. 4 © Addison-Wesley Publishers 2005

Timestamp ordering z Whenever a transaction’s write operation on an object is accepted, the server creates a new tentative version of the object with write timestamp set to the transaction timestamp. Whenever a read operation is accepted, the timestamp of the transaction is added to its set of read timestamps. z When a transaction is committed, the values of the tentative version become the values of the object, and the timestamps of the tentative version become the write timestamp of the corresponding object. Instructor’s Guide for Coulouris, Dollimore and Kindberg Distributed Systems: Concepts and Design Edn. 4 © Addison-Wesley Publishers 2005

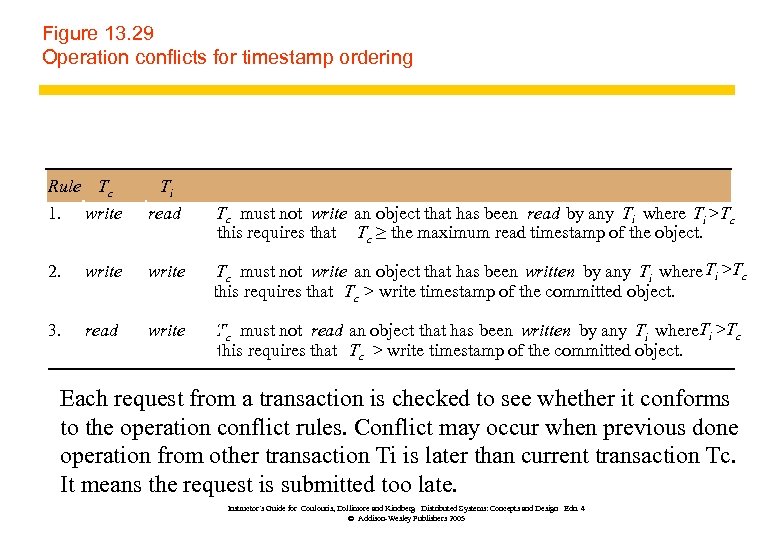

Figure 13. 29 Operation conflicts for timestamp ordering Rule Tc 1. write Ti read 2. write Tc must not write an object that has been written by any Ti where Ti >Tc this requires that Tc > write timestamp of the committed object. 3. read write Tc must not read an object that has been written by any Ti where. Ti >Tc this requires that Tc > write timestamp of the committed object. Tc must not write an object that has been read by any Ti where Ti >Tc this requires that Tc ≥ the maximum read timestamp of the object. Each request from a transaction is checked to see whether it conforms to the operation conflict rules. Conflict may occur when previous done operation from other transaction Ti is later than current transaction Tc. It means the request is submitted too late. Instructor’s Guide for Coulouris, Dollimore and Kindberg Distributed Systems: Concepts and Design Edn. 4 © Addison-Wesley Publishers 2005

Figure 13. 29 Operation conflicts for timestamp ordering Rule Tc 1. write Ti read 2. write Tc must not write an object that has been written by any Ti where Ti >Tc this requires that Tc > write timestamp of the committed object. 3. read write Tc must not read an object that has been written by any Ti where. Ti >Tc this requires that Tc > write timestamp of the committed object. Tc must not write an object that has been read by any Ti where Ti >Tc this requires that Tc ≥ the maximum read timestamp of the object. Each request from a transaction is checked to see whether it conforms to the operation conflict rules. Conflict may occur when previous done operation from other transaction Ti is later than current transaction Tc. It means the request is submitted too late. Instructor’s Guide for Coulouris, Dollimore and Kindberg Distributed Systems: Concepts and Design Edn. 4 © Addison-Wesley Publishers 2005

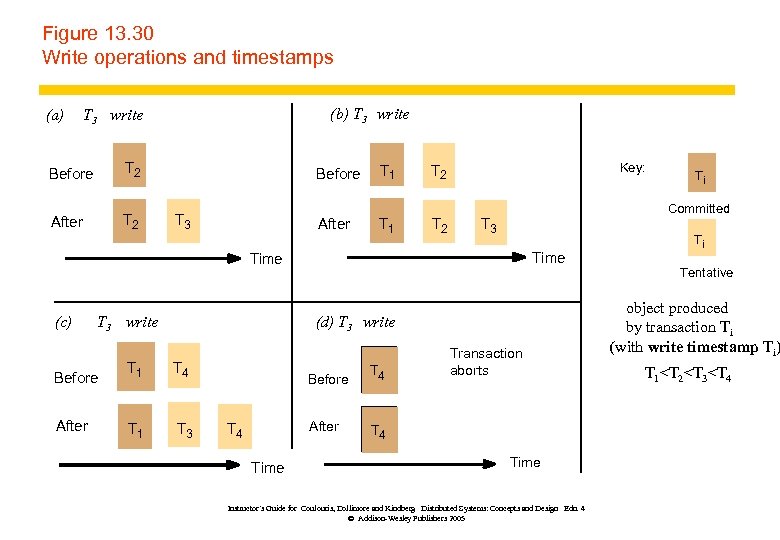

Figure 13. 30 Write operations and timestamps (a) (b) T 3 write Before T 2 After T 2 Before T 3 After T 1 Key: T 2 Committed T 3 Time (c) T 3 write (d) T 3 write Before T 1 T 4 After T 1 T 3 Before After T 4 Time T 4 Ti Transaction aborts T 4 Time Instructor’s Guide for Coulouris, Dollimore and Kindberg Distributed Systems: Concepts and Design Edn. 4 © Addison-Wesley Publishers 2005 Ti Tentative object produced by transaction Ti (with write timestamp Ti) T 1

Figure 13. 30 Write operations and timestamps (a) (b) T 3 write Before T 2 After T 2 Before T 3 After T 1 Key: T 2 Committed T 3 Time (c) T 3 write (d) T 3 write Before T 1 T 4 After T 1 T 3 Before After T 4 Time T 4 Ti Transaction aborts T 4 Time Instructor’s Guide for Coulouris, Dollimore and Kindberg Distributed Systems: Concepts and Design Edn. 4 © Addison-Wesley Publishers 2005 Ti Tentative object produced by transaction Ti (with write timestamp Ti) T 1

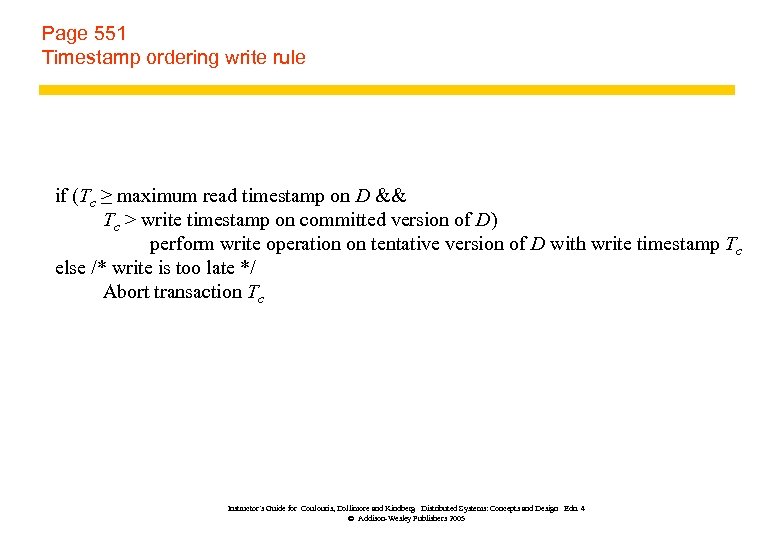

Page 551 Timestamp ordering write rule if (Tc ≥ maximum read timestamp on D && Tc > write timestamp on committed version of D) perform write operation on tentative version of D with write timestamp Tc else /* write is too late */ Abort transaction Tc Instructor’s Guide for Coulouris, Dollimore and Kindberg Distributed Systems: Concepts and Design Edn. 4 © Addison-Wesley Publishers 2005

Page 551 Timestamp ordering write rule if (Tc ≥ maximum read timestamp on D && Tc > write timestamp on committed version of D) perform write operation on tentative version of D with write timestamp Tc else /* write is too late */ Abort transaction Tc Instructor’s Guide for Coulouris, Dollimore and Kindberg Distributed Systems: Concepts and Design Edn. 4 © Addison-Wesley Publishers 2005

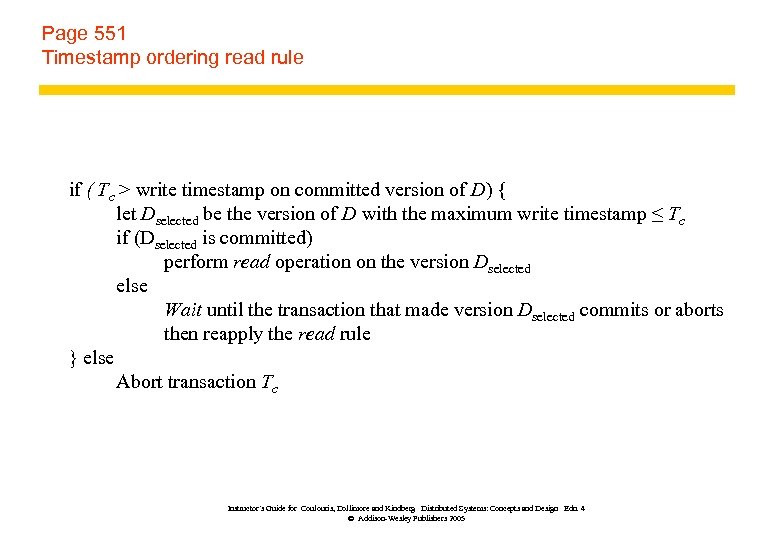

Page 551 Timestamp ordering read rule if ( Tc > write timestamp on committed version of D) { let Dselected be the version of D with the maximum write timestamp ≤ Tc if (Dselected is committed) perform read operation on the version Dselected else Wait until the transaction that made version Dselected commits or aborts then reapply the read rule } else Abort transaction Tc Instructor’s Guide for Coulouris, Dollimore and Kindberg Distributed Systems: Concepts and Design Edn. 4 © Addison-Wesley Publishers 2005

Page 551 Timestamp ordering read rule if ( Tc > write timestamp on committed version of D) { let Dselected be the version of D with the maximum write timestamp ≤ Tc if (Dselected is committed) perform read operation on the version Dselected else Wait until the transaction that made version Dselected commits or aborts then reapply the read rule } else Abort transaction Tc Instructor’s Guide for Coulouris, Dollimore and Kindberg Distributed Systems: Concepts and Design Edn. 4 © Addison-Wesley Publishers 2005

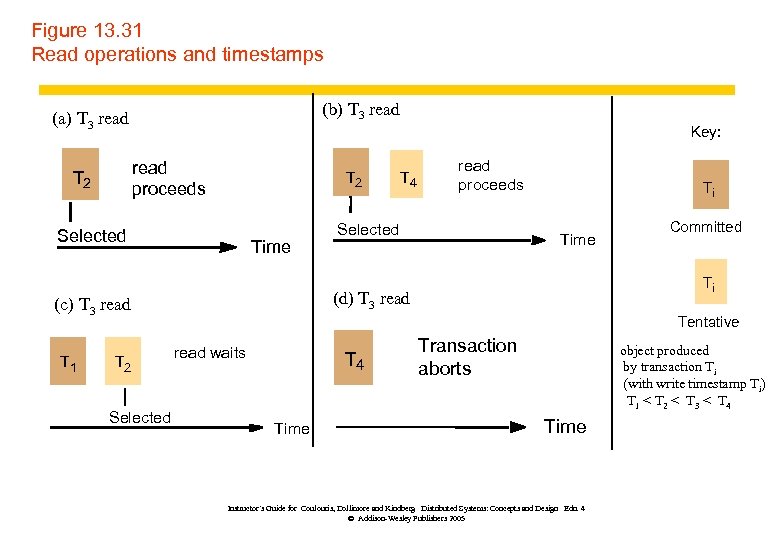

Figure 13. 31 Read operations and timestamps (b) T 3 read (a) T 3 read Key: read proceeds T 2 Selected Time T 2 Selected read proceeds Selected Ti Time Committed Ti (d) T 3 read (c) T 3 read T 1 T 4 Tentative read waits T 4 Time Transaction aborts object produced by transaction Ti (with write timestamp Ti) T 1 < T 2 < T 3 < T 4 Time Instructor’s Guide for Coulouris, Dollimore and Kindberg Distributed Systems: Concepts and Design Edn. 4 © Addison-Wesley Publishers 2005

Figure 13. 31 Read operations and timestamps (b) T 3 read (a) T 3 read Key: read proceeds T 2 Selected Time T 2 Selected read proceeds Selected Ti Time Committed Ti (d) T 3 read (c) T 3 read T 1 T 4 Tentative read waits T 4 Time Transaction aborts object produced by transaction Ti (with write timestamp Ti) T 1 < T 2 < T 3 < T 4 Time Instructor’s Guide for Coulouris, Dollimore and Kindberg Distributed Systems: Concepts and Design Edn. 4 © Addison-Wesley Publishers 2005

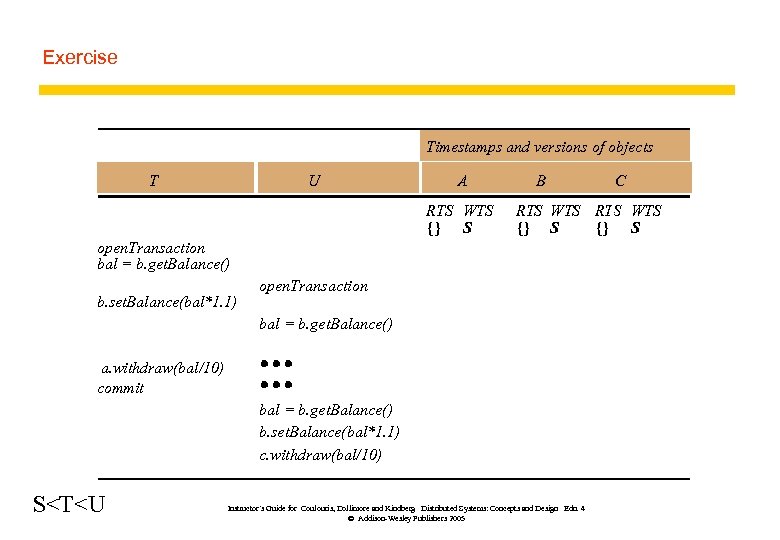

Exercise Timestamps and versions of objects T U A RTS WTS {} S B RTS WTS {} S open. Transaction bal = b. get. Balance() b. set. Balance(bal*1. 1) open. Transaction bal = b. get. Balance() a. withdraw(bal/10) commit bal = b. get. Balance() b. set. Balance(bal*1. 1) c. withdraw(bal/10) S

Exercise Timestamps and versions of objects T U A RTS WTS {} S B RTS WTS {} S open. Transaction bal = b. get. Balance() b. set. Balance(bal*1. 1) open. Transaction bal = b. get. Balance() a. withdraw(bal/10) commit bal = b. get. Balance() b. set. Balance(bal*1. 1) c. withdraw(bal/10) S

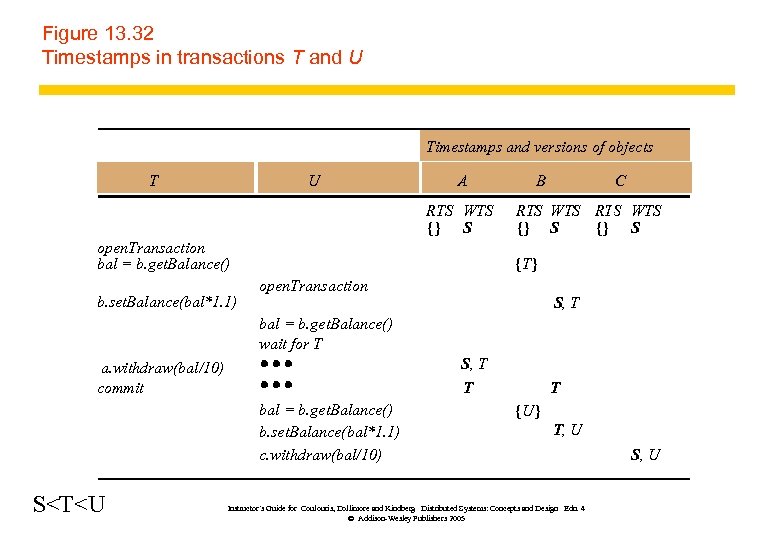

Figure 13. 32 Timestamps in transactions T and U Timestamps and versions of objects T U A RTS WTS {} S open. Transaction bal = b. get. Balance() b. set. Balance(bal*1. 1) B C RTS WTS {} S {T} open. Transaction S, T bal = b. get. Balance() wait for T S, T a. withdraw(bal/10) commit T bal = b. get. Balance() b. set. Balance(bal*1. 1) c. withdraw(bal/10) S

Figure 13. 32 Timestamps in transactions T and U Timestamps and versions of objects T U A RTS WTS {} S open. Transaction bal = b. get. Balance() b. set. Balance(bal*1. 1) B C RTS WTS {} S {T} open. Transaction S, T bal = b. get. Balance() wait for T S, T a. withdraw(bal/10) commit T bal = b. get. Balance() b. set. Balance(bal*1. 1) c. withdraw(bal/10) S

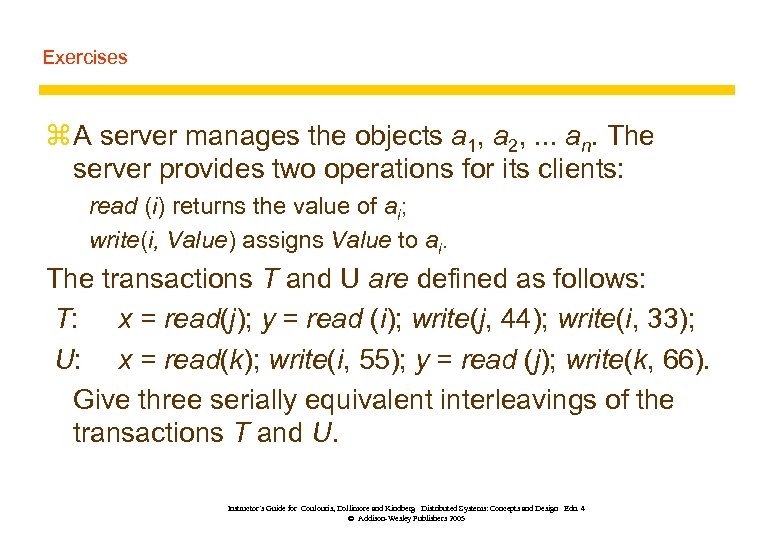

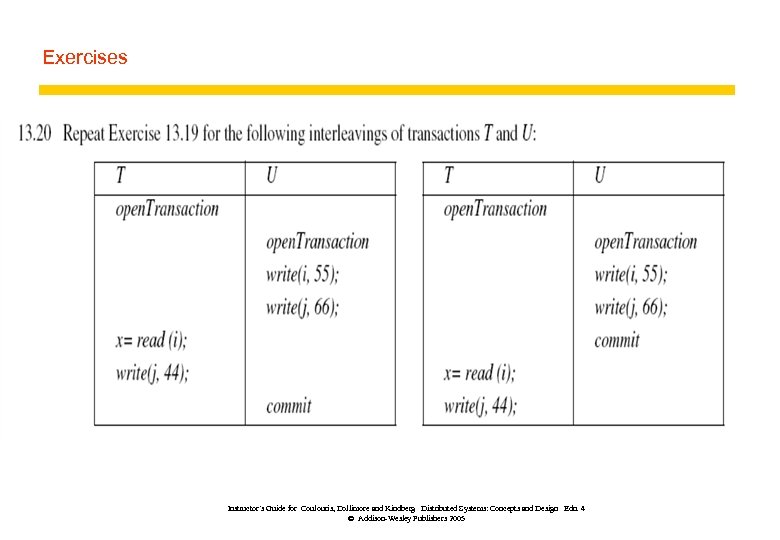

Exercises z A server manages the objects a 1, a 2, . . . an. The server provides two operations for its clients: read (i) returns the value of ai; write(i, Value) assigns Value to ai. The transactions T and U are defined as follows: T: x = read(j); y = read (i); write(j, 44); write(i, 33); U: x = read(k); write(i, 55); y = read (j); write(k, 66). Give three serially equivalent interleavings of the transactions T and U. Instructor’s Guide for Coulouris, Dollimore and Kindberg Distributed Systems: Concepts and Design Edn. 4 © Addison-Wesley Publishers 2005