facf01b669ac2907265d8af3d408d6d0.ppt

- Количество слайдов: 57

Slides for Chapter 6 Note to Instructors This Keynote document contains the slides for “When Words Collide”, Chapter 6 of Explorations in Computing: An Introduction to Computer Science. The book invites students to explore ideas in computer science through interactive tutorials where they type expressions in Ruby and immediately see the results, either in a terminal window or a 2 D graphics window. Instructors are strongly encouraged to have a Ruby session running concurrently with Keynote in order to give live demonstrations of the Ruby code shown on the slides. License The slides in this Keynote document are based on copyrighted material from Explorations in Computing: An Introduction to Computer Science, by John S. Conery. These slides are provided free of charge to instructors who are using the textbook for their courses. Instructors may alter the slides for use in their own courses, including but not limited to: adding new slides, altering the wording or images found on these slides, or deleting slides. Instructors may distribute printed copies of the slides, either in hard copy or as electronic copies in PDF form, provided the copyright notice below is reproduced on the first slide. © 2012 John S. Conery

Slides for Chapter 6 Note to Instructors This Keynote document contains the slides for “When Words Collide”, Chapter 6 of Explorations in Computing: An Introduction to Computer Science. The book invites students to explore ideas in computer science through interactive tutorials where they type expressions in Ruby and immediately see the results, either in a terminal window or a 2 D graphics window. Instructors are strongly encouraged to have a Ruby session running concurrently with Keynote in order to give live demonstrations of the Ruby code shown on the slides. License The slides in this Keynote document are based on copyrighted material from Explorations in Computing: An Introduction to Computer Science, by John S. Conery. These slides are provided free of charge to instructors who are using the textbook for their courses. Instructors may alter the slides for use in their own courses, including but not limited to: adding new slides, altering the wording or images found on these slides, or deleting slides. Instructors may distribute printed copies of the slides, either in hard copy or as electronic copies in PDF form, provided the copyright notice below is reproduced on the first slide. © 2012 John S. Conery

When Words Collide Organizing data for more efficient problem solving ✦ Word Lists ✦ Hash Tables ✦ The mod Function Again ✦ Collisions ✦ Hash Table Experiments Explorations in Computing © 2012 John S. Conery

When Words Collide Organizing data for more efficient problem solving ✦ Word Lists ✦ Hash Tables ✦ The mod Function Again ✦ Collisions ✦ Hash Table Experiments Explorations in Computing © 2012 John S. Conery

Spell Check ✦ When the “spell check” option is turned on an application will indicate misspelled words as soon as you type them ✦ The system uses a wordlist ❖ ❖ ✦ like a dictionary but it doesn’t have any definitions simply a list of correctly spelled words Each time you end a word the application searches the wordlist ? ?

Spell Check ✦ When the “spell check” option is turned on an application will indicate misspelled words as soon as you type them ✦ The system uses a wordlist ❖ ❖ ✦ like a dictionary but it doesn’t have any definitions simply a list of correctly spelled words Each time you end a word the application searches the wordlist ? ?

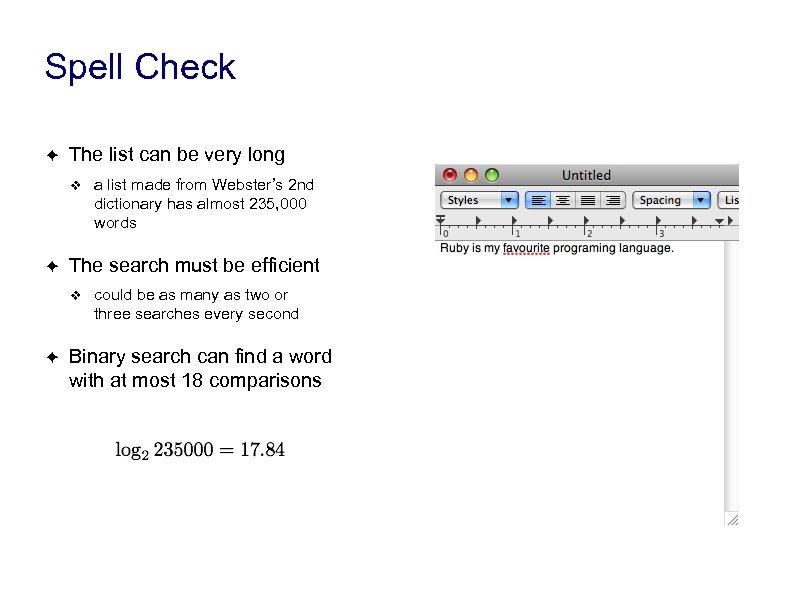

Spell Check ✦ The list can be very long ❖ ✦ The search must be efficient ❖ ✦ a list made from Webster’s 2 nd dictionary has almost 235, 000 words could be as many as two or three searches every second Binary search can find a word with at most 18 comparisons

Spell Check ✦ The list can be very long ❖ ✦ The search must be efficient ❖ ✦ a list made from Webster’s 2 nd dictionary has almost 235, 000 words could be as many as two or three searches every second Binary search can find a word with at most 18 comparisons

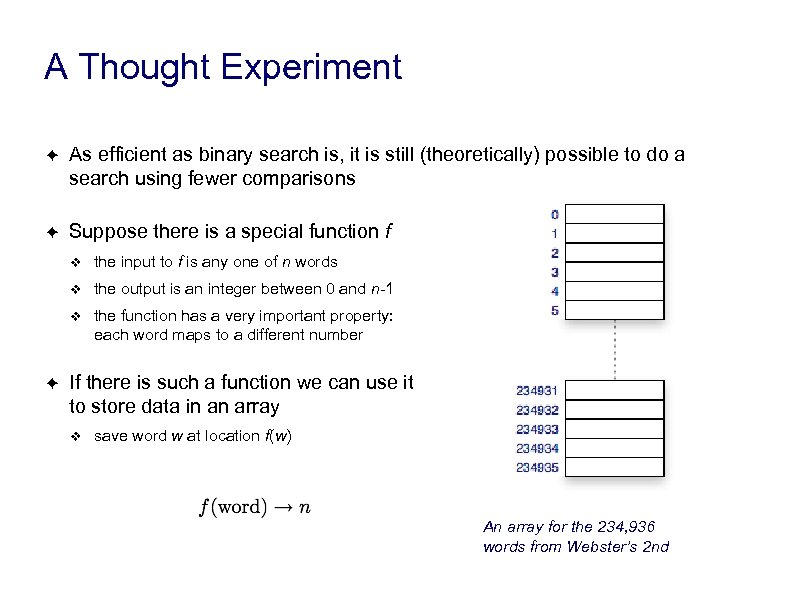

A Thought Experiment ✦ As efficient as binary search is, it is still (theoretically) possible to do a search using fewer comparisons ✦ Suppose there is a special function f ❖ ❖ the output is an integer between 0 and n-1 ❖ ✦ the input to f is any one of n words the function has a very important property: each word maps to a different number If there is such a function we can use it to store data in an array ❖ save word w at location f(w) An array for the 234, 936 words from Webster’s 2 nd

A Thought Experiment ✦ As efficient as binary search is, it is still (theoretically) possible to do a search using fewer comparisons ✦ Suppose there is a special function f ❖ ❖ the output is an integer between 0 and n-1 ❖ ✦ the input to f is any one of n words the function has a very important property: each word maps to a different number If there is such a function we can use it to store data in an array ❖ save word w at location f(w) An array for the 234, 936 words from Webster’s 2 nd

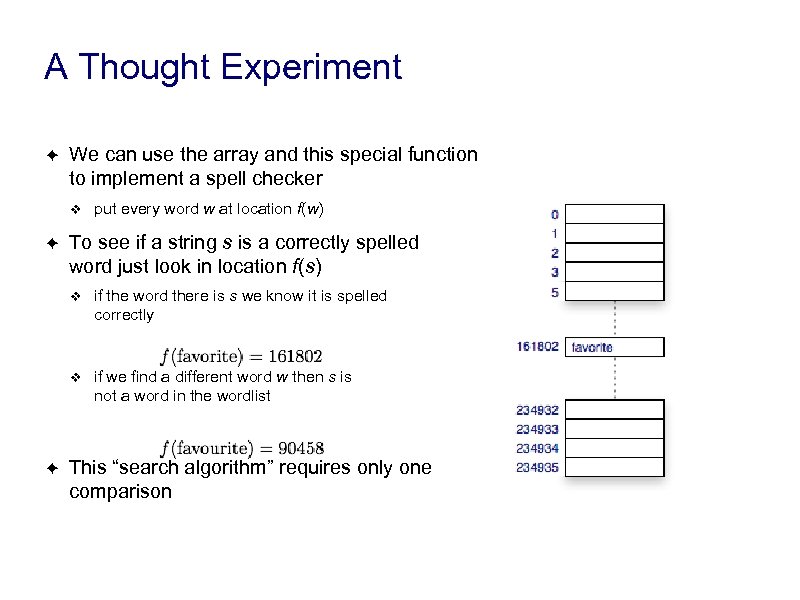

A Thought Experiment ✦ We can use the array and this special function to implement a spell checker ❖ ✦ put every word w at location f(w) To see if a string s is a correctly spelled word just look in location f(s) ❖ ❖ ✦ if the word there is s we know it is spelled correctly if we find a different word w then s is not a word in the wordlist This “search algorithm” requires only one comparison

A Thought Experiment ✦ We can use the array and this special function to implement a spell checker ❖ ✦ put every word w at location f(w) To see if a string s is a correctly spelled word just look in location f(s) ❖ ❖ ✦ if the word there is s we know it is spelled correctly if we find a different word w then s is not a word in the wordlist This “search algorithm” requires only one comparison

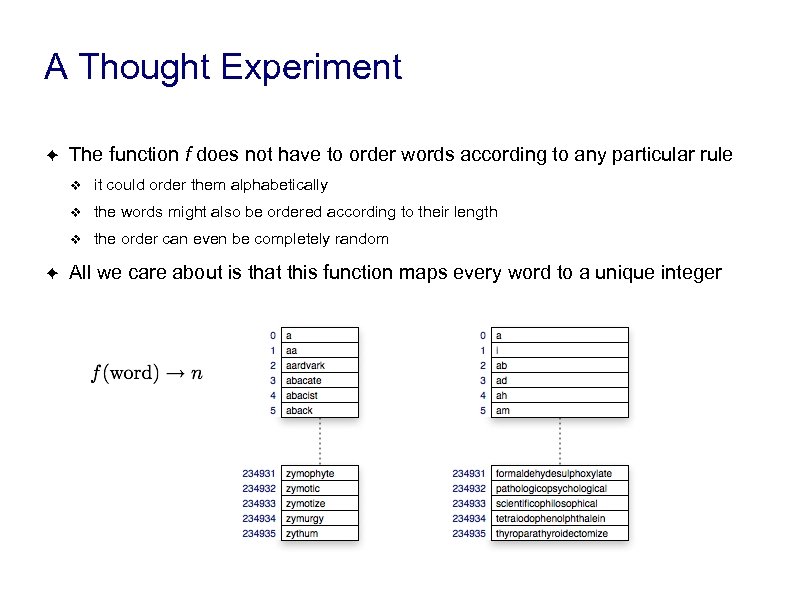

A Thought Experiment ✦ The function f does not have to order words according to any particular rule ❖ ❖ the words might also be ordered according to their length ❖ ✦ it could order them alphabetically the order can even be completely random All we care about is that this function maps every word to a unique integer

A Thought Experiment ✦ The function f does not have to order words according to any particular rule ❖ ❖ the words might also be ordered according to their length ❖ ✦ it could order them alphabetically the order can even be completely random All we care about is that this function maps every word to a unique integer

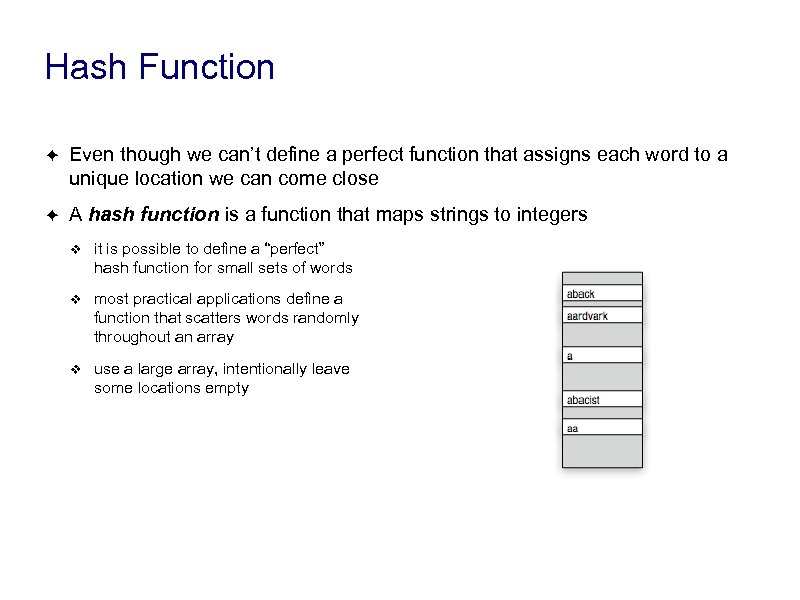

Hash Function ✦ Even though we can’t define a perfect function that assigns each word to a unique location we can come close ✦ A hash function is a function that maps strings to integers ❖ it is possible to define a “perfect” hash function for small sets of words ❖ most practical applications define a function that scatters words randomly throughout an array ❖ use a large array, intentionally leave some locations empty

Hash Function ✦ Even though we can’t define a perfect function that assigns each word to a unique location we can come close ✦ A hash function is a function that maps strings to integers ❖ it is possible to define a “perfect” hash function for small sets of words ❖ most practical applications define a function that scatters words randomly throughout an array ❖ use a large array, intentionally leave some locations empty

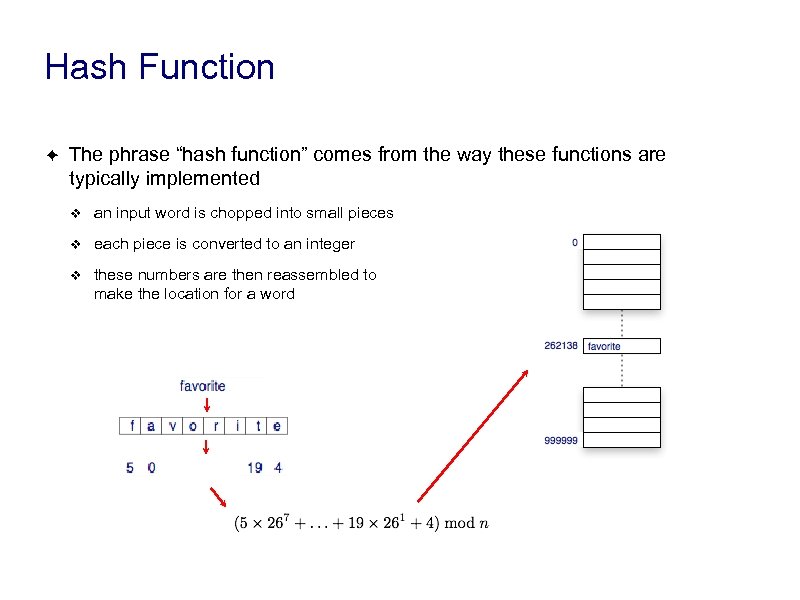

Hash Function ✦ The phrase “hash function” comes from the way these functions are typically implemented ❖ an input word is chopped into small pieces ❖ each piece is converted to an integer ❖ these numbers are then reassembled to make the location for a word

Hash Function ✦ The phrase “hash function” comes from the way these functions are typically implemented ❖ an input word is chopped into small pieces ❖ each piece is converted to an integer ❖ these numbers are then reassembled to make the location for a word

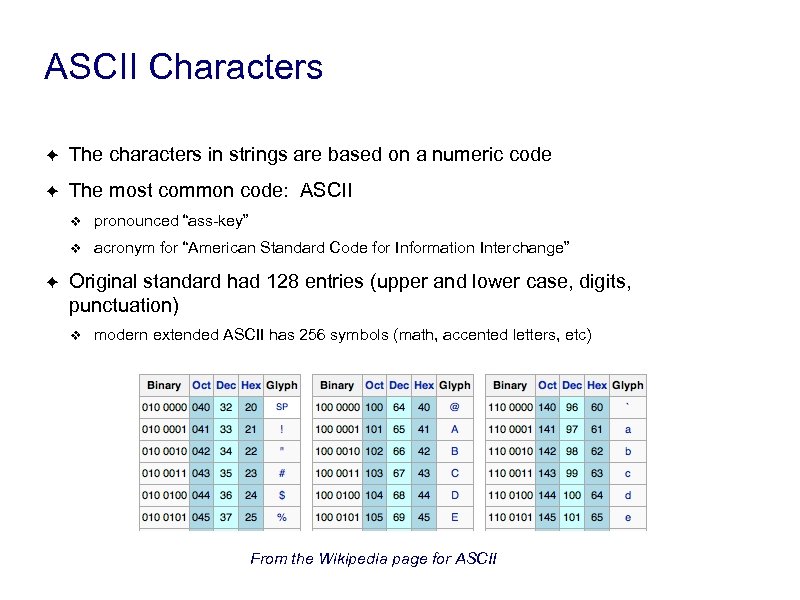

ASCII Characters ✦ The characters in strings are based on a numeric code ✦ The most common code: ASCII ❖ ❖ ✦ pronounced “ass-key” acronym for “American Standard Code for Information Interchange” Original standard had 128 entries (upper and lower case, digits, punctuation) ❖ modern extended ASCII has 256 symbols (math, accented letters, etc) From the Wikipedia page for ASCII

ASCII Characters ✦ The characters in strings are based on a numeric code ✦ The most common code: ASCII ❖ ❖ ✦ pronounced “ass-key” acronym for “American Standard Code for Information Interchange” Original standard had 128 entries (upper and lower case, digits, punctuation) ❖ modern extended ASCII has 256 symbols (math, accented letters, etc) From the Wikipedia page for ASCII

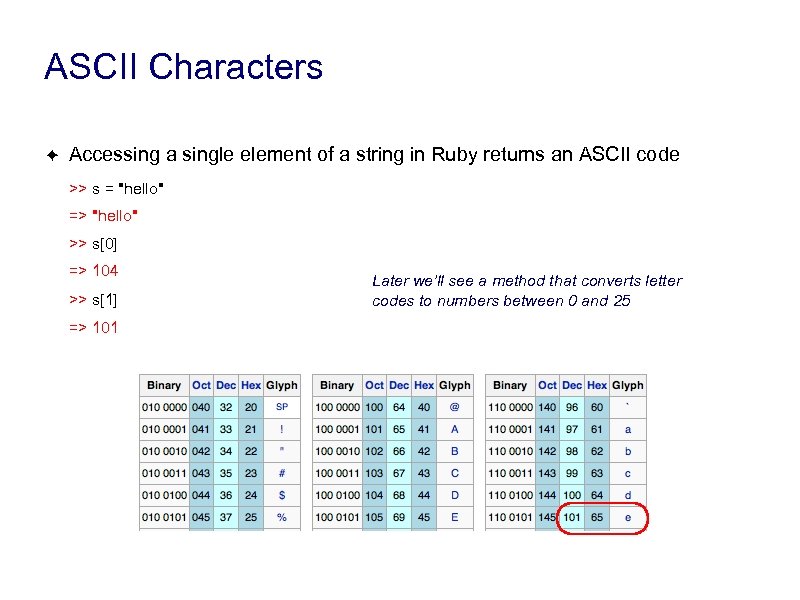

ASCII Characters ✦ Accessing a single element of a string in Ruby returns an ASCII code >> s = "hello" => "hello" >> s[0] => 104 >> s[1] => 101 Later we’ll see a method that converts letter codes to numbers between 0 and 25

ASCII Characters ✦ Accessing a single element of a string in Ruby returns an ASCII code >> s = "hello" => "hello" >> s[0] => 104 >> s[1] => 101 Later we’ll see a method that converts letter codes to numbers between 0 and 25

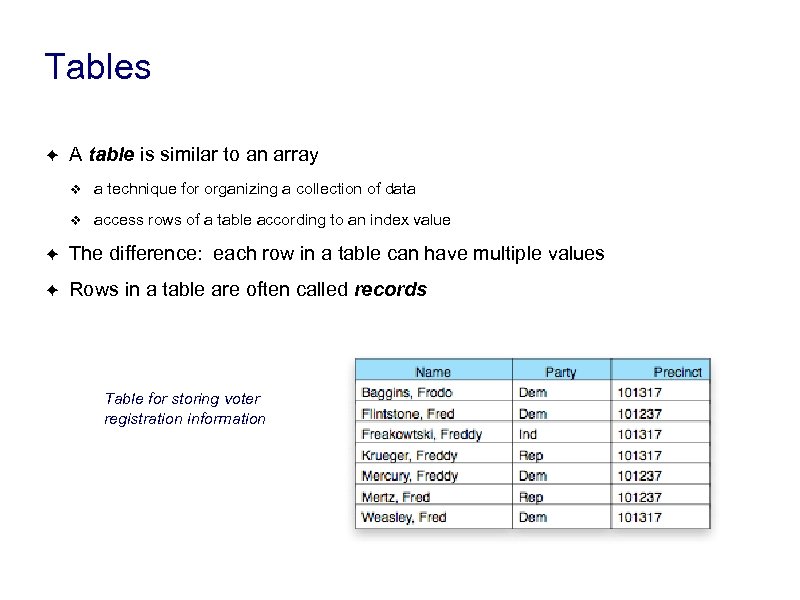

Tables ✦ A table is similar to an array ❖ a technique for organizing a collection of data ❖ access rows of a table according to an index value ✦ The difference: each row in a table can have multiple values ✦ Rows in a table are often called records Table for storing voter registration information

Tables ✦ A table is similar to an array ❖ a technique for organizing a collection of data ❖ access rows of a table according to an index value ✦ The difference: each row in a table can have multiple values ✦ Rows in a table are often called records Table for storing voter registration information

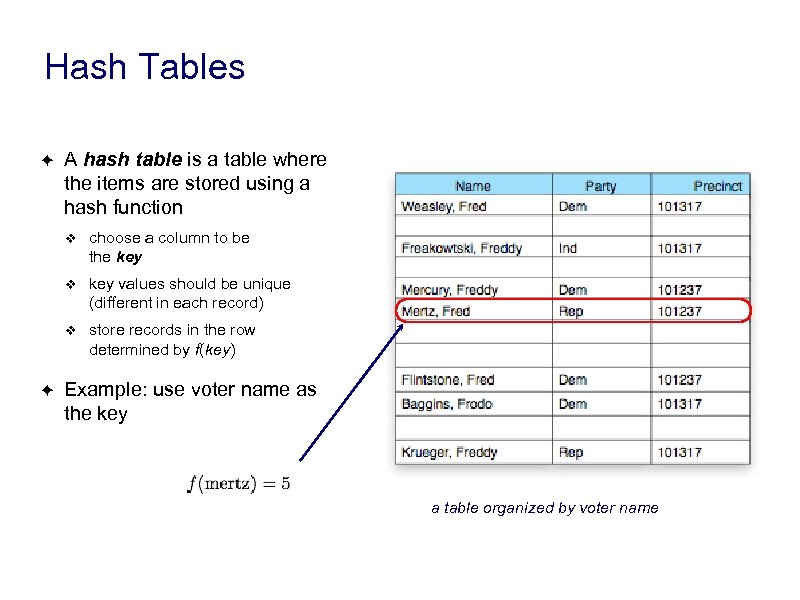

Hash Tables ✦ A hash table is a table where the items are stored using a hash function ❖ ❖ key values should be unique (different in each record) ❖ ✦ choose a column to be the key store records in the row determined by f(key) Example: use voter name as the key a table organized by voter name

Hash Tables ✦ A hash table is a table where the items are stored using a hash function ❖ ❖ key values should be unique (different in each record) ❖ ✦ choose a column to be the key store records in the row determined by f(key) Example: use voter name as the key a table organized by voter name

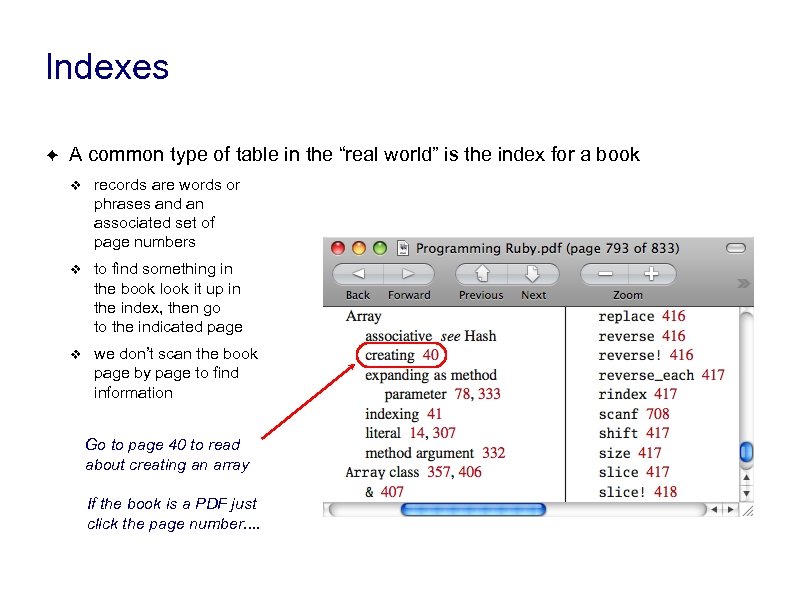

Indexes ✦ A common type of table in the “real world” is the index for a book ❖ records are words or phrases and an associated set of page numbers ❖ to find something in the book look it up in the index, then go to the indicated page ❖ we don’t scan the book page by page to find information Go to page 40 to read about creating an array If the book is a PDF just click the page number. .

Indexes ✦ A common type of table in the “real world” is the index for a book ❖ records are words or phrases and an associated set of page numbers ❖ to find something in the book look it up in the index, then go to the indicated page ❖ we don’t scan the book page by page to find information Go to page 40 to read about creating an array If the book is a PDF just click the page number. .

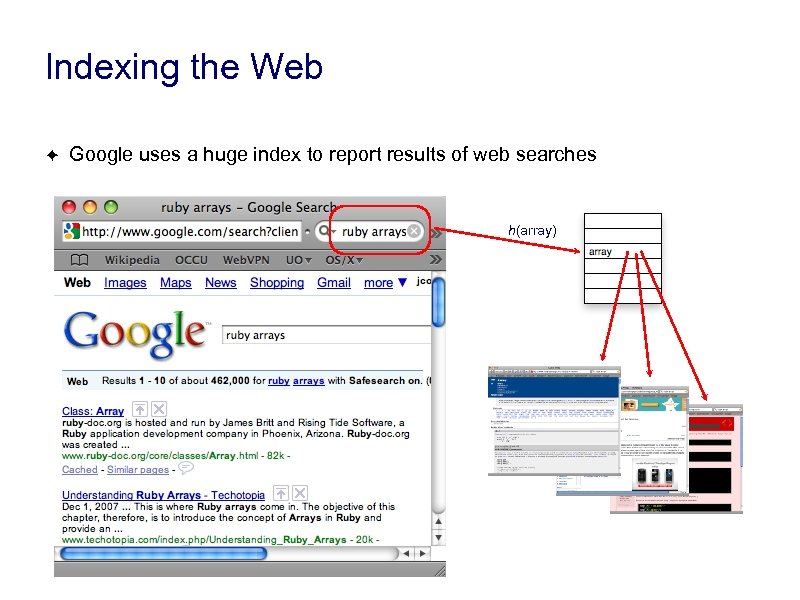

Indexing the Web ✦ Google uses a huge index to report results of web searches h(array)

Indexing the Web ✦ Google uses a huge index to report results of web searches h(array)

Project Outline ✦ The project for this chapter will be on hash functions ❖ ❖ ✦ techniques for mapping strings to integers properties of different types of functions To simplify things we won’t consider tables and how to manage the extra information ❖ ✦ we’ll just look at how to organize an “index” and how to resolve collisions We’ll run some experiments on large wordlists

Project Outline ✦ The project for this chapter will be on hash functions ❖ ❖ ✦ techniques for mapping strings to integers properties of different types of functions To simplify things we won’t consider tables and how to manage the extra information ❖ ✦ we’ll just look at how to organize an “index” and how to resolve collisions We’ll run some experiments on large wordlists

Indexes in Ruby ✦ We can use a Ruby Array object to represent an index ✦ In our other projects, we used Arrays as lists ❖ initialized with a collection of objects ❖ Array grows and shrinks as objects are added or removed >> a = Test. Array. new(5, : colors) => ["moccasin", "chocolate", "forest green", "yellow", "navy"] >> a. length => 5 ✦ The difference in this project: the Array object will have a fixed size, and some of the rows will be empty

Indexes in Ruby ✦ We can use a Ruby Array object to represent an index ✦ In our other projects, we used Arrays as lists ❖ initialized with a collection of objects ❖ Array grows and shrinks as objects are added or removed >> a = Test. Array. new(5, : colors) => ["moccasin", "chocolate", "forest green", "yellow", "navy"] >> a. length => 5 ✦ The difference in this project: the Array object will have a fixed size, and some of the rows will be empty

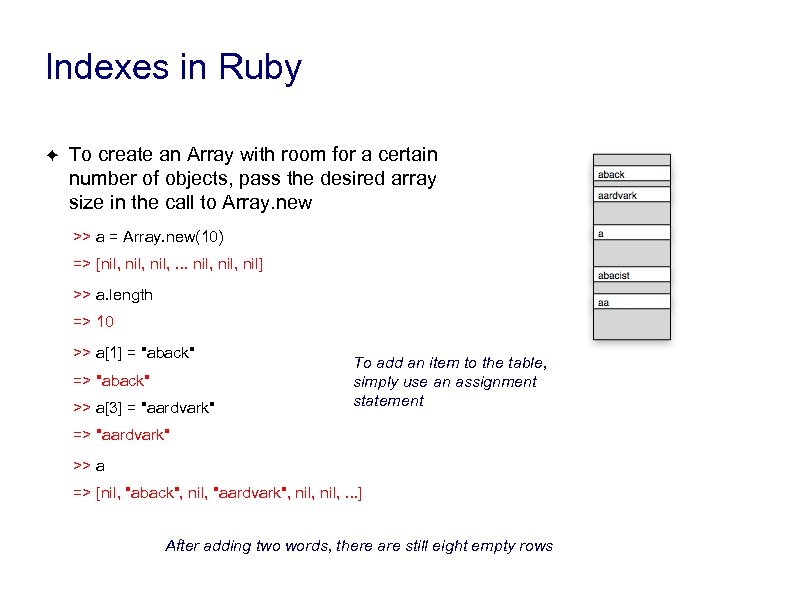

Indexes in Ruby ✦ To create an Array with room for a certain number of objects, pass the desired array size in the call to Array. new >> a = Array. new(10) => [nil, . . . nil, nil] >> a. length => 10 >> a[1] = "aback" => "aback" >> a[3] = "aardvark" To add an item to the table, simply use an assignment statement => "aardvark" >> a => [nil, "aback", nil, "aardvark", nil, . . . ] After adding two words, there are still eight empty rows

Indexes in Ruby ✦ To create an Array with room for a certain number of objects, pass the desired array size in the call to Array. new >> a = Array. new(10) => [nil, . . . nil, nil] >> a. length => 10 >> a[1] = "aback" => "aback" >> a[3] = "aardvark" To add an item to the table, simply use an assignment statement => "aardvark" >> a => [nil, "aback", nil, "aardvark", nil, . . . ] After adding two words, there are still eight empty rows

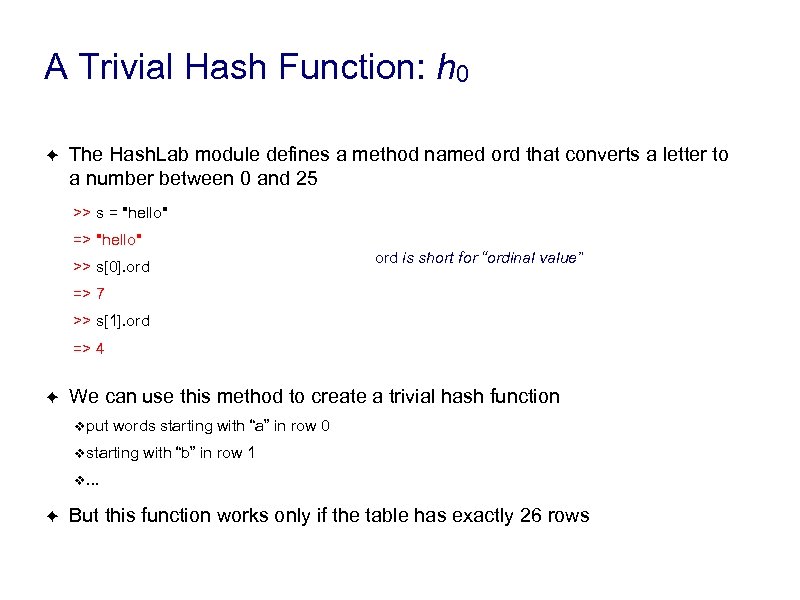

A Trivial Hash Function: h 0 ✦ The Hash. Lab module defines a method named ord that converts a letter to a number between 0 and 25 >> s = "hello" => "hello" >> s[0]. ord is short for “ordinal value” => 7 >> s[1]. ord => 4 ✦ We can use this method to create a trivial hash function ❖put words starting with “a” in row 0 ❖starting with “b” in row 1 ❖. . . ✦ But this function works only if the table has exactly 26 rows

A Trivial Hash Function: h 0 ✦ The Hash. Lab module defines a method named ord that converts a letter to a number between 0 and 25 >> s = "hello" => "hello" >> s[0]. ord is short for “ordinal value” => 7 >> s[1]. ord => 4 ✦ We can use this method to create a trivial hash function ❖put words starting with “a” in row 0 ❖starting with “b” in row 1 ❖. . . ✦ But this function works only if the table has exactly 26 rows

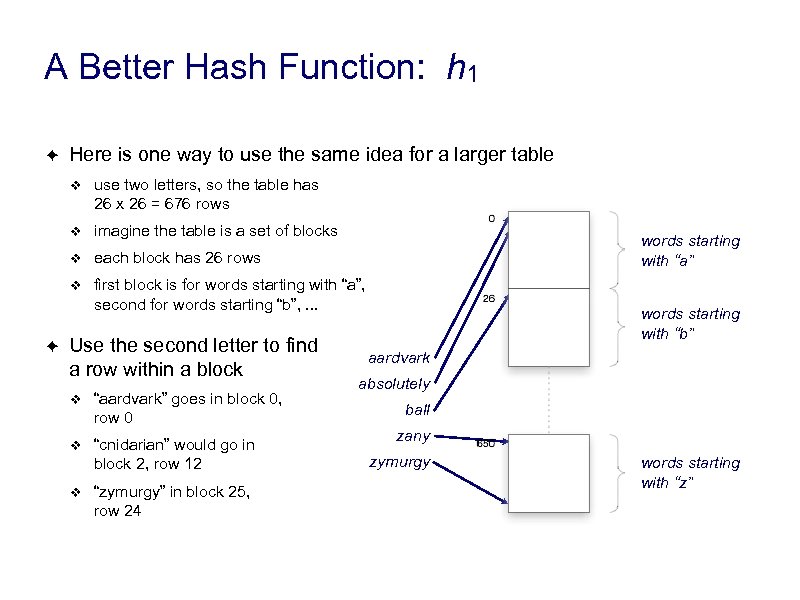

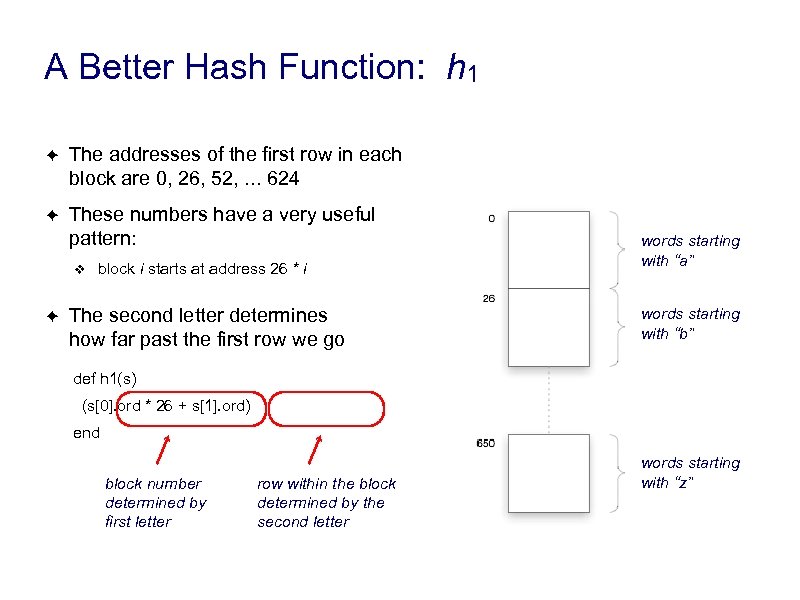

A Better Hash Function: h 1 ✦ Here is one way to use the same idea for a larger table ❖ ❖ imagine the table is a set of blocks ❖ each block has 26 rows ❖ ✦ use two letters, so the table has 26 x 26 = 676 rows first block is for words starting with “a”, second for words starting “b”, . . . Use the second letter to find a row within a block ❖ “aardvark” goes in block 0, row 0 ❖ “cnidarian” would go in block 2, row 12 ❖ “zymurgy” in block 25, row 24 words starting with “a” words starting with “b” aardvark absolutely ball zany zymurgy words starting with “z”

A Better Hash Function: h 1 ✦ Here is one way to use the same idea for a larger table ❖ ❖ imagine the table is a set of blocks ❖ each block has 26 rows ❖ ✦ use two letters, so the table has 26 x 26 = 676 rows first block is for words starting with “a”, second for words starting “b”, . . . Use the second letter to find a row within a block ❖ “aardvark” goes in block 0, row 0 ❖ “cnidarian” would go in block 2, row 12 ❖ “zymurgy” in block 25, row 24 words starting with “a” words starting with “b” aardvark absolutely ball zany zymurgy words starting with “z”

A Better Hash Function: h 1 ✦ The addresses of the first row in each block are 0, 26, 52, . . . 624 ✦ These numbers have a very useful pattern: ❖ ✦ block i starts at address 26 * i The second letter determines how far past the first row we go words starting with “a” words starting with “b” def h 1(s) (s[0]. ord * 26 + s[1]. ord) end block number determined by first letter row within the block determined by the second letter words starting with “z”

A Better Hash Function: h 1 ✦ The addresses of the first row in each block are 0, 26, 52, . . . 624 ✦ These numbers have a very useful pattern: ❖ ✦ block i starts at address 26 * i The second letter determines how far past the first row we go words starting with “a” words starting with “b” def h 1(s) (s[0]. ord * 26 + s[1]. ord) end block number determined by first letter row within the block determined by the second letter words starting with “z”

![Hash Function h 1 def h 1(s) (s[0]. ord * 26 + s[1]. ord)end Hash Function h 1 def h 1(s) (s[0]. ord * 26 + s[1]. ord)end](https://present5.com/presentation/facf01b669ac2907265d8af3d408d6d0/image-22.jpg) Hash Function h 1 def h 1(s) (s[0]. ord * 26 + s[1]. ord)end ✦ Example in IRB: >> h 1("aardvark") => 0 >> h 1("abcissa") words starting with “a” => 1 >> h 1("cnidarian") words starting with “b” => 65 >> h 1("zany") => 650 >> h 1("zymurgy") => 674 words starting with “z”

Hash Function h 1 def h 1(s) (s[0]. ord * 26 + s[1]. ord)end ✦ Example in IRB: >> h 1("aardvark") => 0 >> h 1("abcissa") words starting with “a” => 1 >> h 1("cnidarian") words starting with “b” => 65 >> h 1("zany") => 650 >> h 1("zymurgy") => 674 words starting with “z”

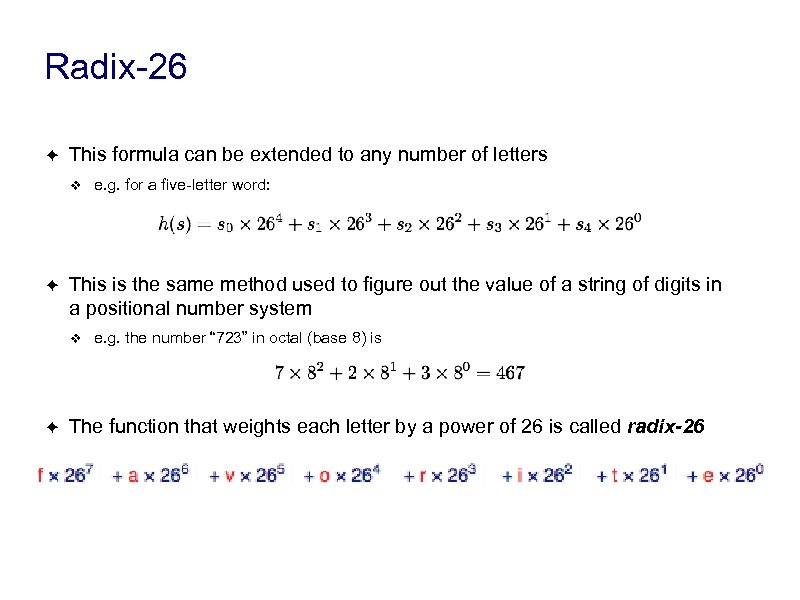

Radix-26 ✦ This formula can be extended to any number of letters ❖ ✦ This is the same method used to figure out the value of a string of digits in a positional number system ❖ ✦ e. g. for a five-letter word: e. g. the number “ 723” in octal (base 8) is The function that weights each letter by a power of 26 is called radix-26

Radix-26 ✦ This formula can be extended to any number of letters ❖ ✦ This is the same method used to figure out the value of a string of digits in a positional number system ❖ ✦ e. g. for a five-letter word: e. g. the number “ 723” in octal (base 8) is The function that weights each letter by a power of 26 is called radix-26

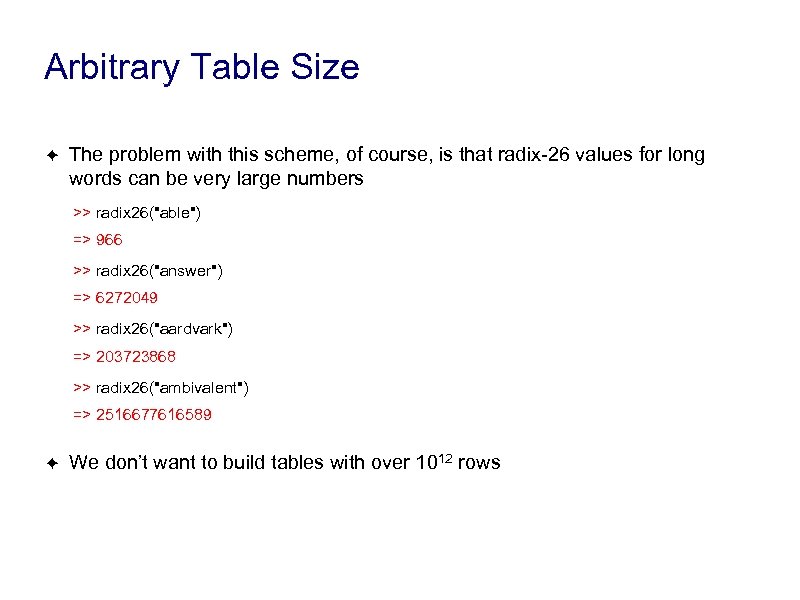

Arbitrary Table Size ✦ The problem with this scheme, of course, is that radix-26 values for long words can be very large numbers >> radix 26("able") => 966 >> radix 26("answer") => 6272049 >> radix 26("aardvark") => 203723868 >> radix 26("ambivalent") => 2516677616589 ✦ We don’t want to build tables with over 1012 rows

Arbitrary Table Size ✦ The problem with this scheme, of course, is that radix-26 values for long words can be very large numbers >> radix 26("able") => 966 >> radix 26("answer") => 6272049 >> radix 26("aardvark") => 203723868 >> radix 26("ambivalent") => 2516677616589 ✦ We don’t want to build tables with over 1012 rows

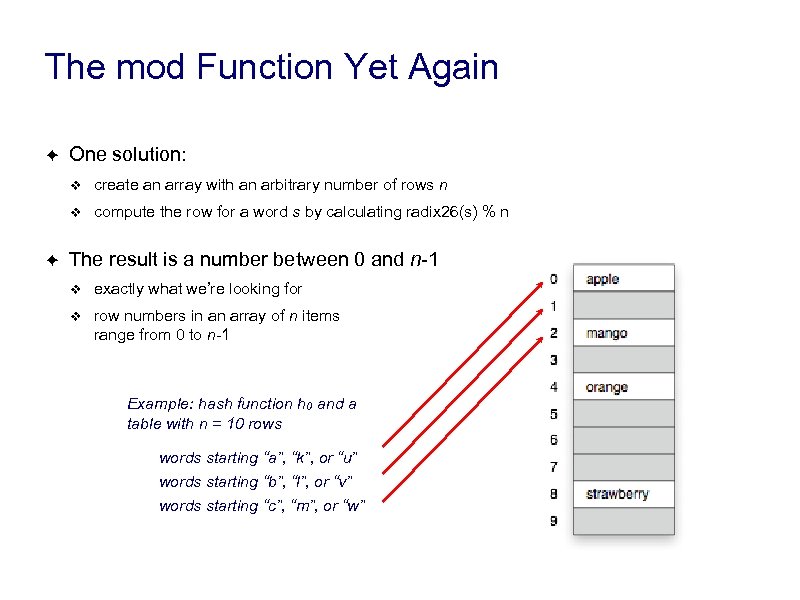

The mod Function Yet Again ✦ One solution: ❖ ❖ ✦ create an array with an arbitrary number of rows n compute the row for a word s by calculating radix 26(s) % n The result is a number between 0 and n-1 ❖ exactly what we’re looking for ❖ row numbers in an array of n items range from 0 to n-1 Example: hash function h 0 and a table with n = 10 rows words starting “a”, “k”, or “u” words starting “b”, “l”, or “v” words starting “c”, “m”, or “w”

The mod Function Yet Again ✦ One solution: ❖ ❖ ✦ create an array with an arbitrary number of rows n compute the row for a word s by calculating radix 26(s) % n The result is a number between 0 and n-1 ❖ exactly what we’re looking for ❖ row numbers in an array of n items range from 0 to n-1 Example: hash function h 0 and a table with n = 10 rows words starting “a”, “k”, or “u” words starting “b”, “l”, or “v” words starting “c”, “m”, or “w”

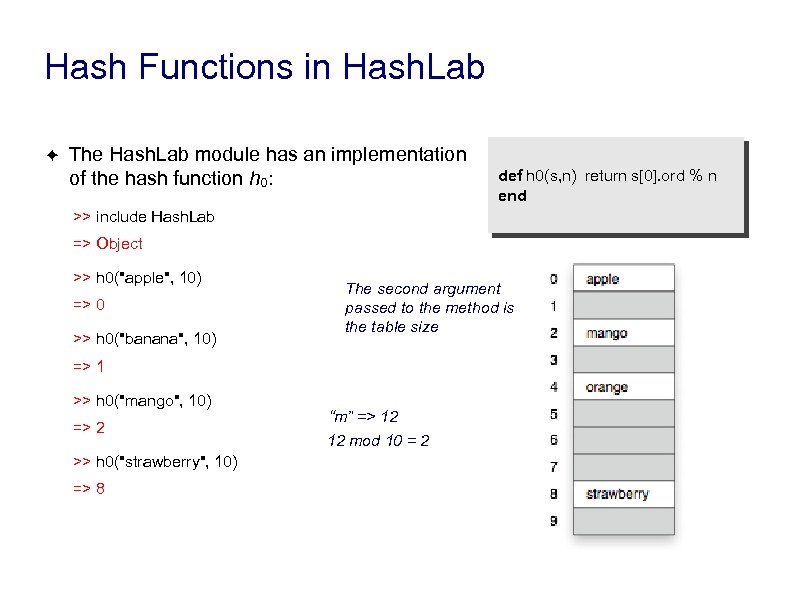

Hash Functions in Hash. Lab ✦ The Hash. Lab module has an implementation of the hash function h 0: def h 0(s, n) return s[0]. ord % n end >> include Hash. Lab => Object >> h 0("apple", 10) => 0 >> h 0("banana", 10) The second argument passed to the method is the table size => 1 >> h 0("mango", 10) => 2 >> h 0("strawberry", 10) => 8 “m” => 12 12 mod 10 = 2

Hash Functions in Hash. Lab ✦ The Hash. Lab module has an implementation of the hash function h 0: def h 0(s, n) return s[0]. ord % n end >> include Hash. Lab => Object >> h 0("apple", 10) => 0 >> h 0("banana", 10) The second argument passed to the method is the table size => 1 >> h 0("mango", 10) => 2 >> h 0("strawberry", 10) => 8 “m” => 12 12 mod 10 = 2

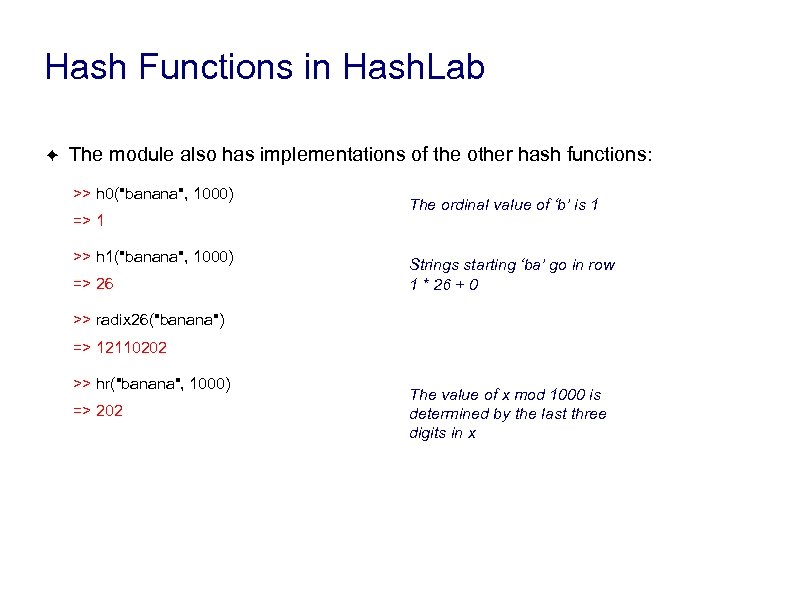

Hash Functions in Hash. Lab ✦ The module also has implementations of the other hash functions: >> h 0("banana", 1000) => 1 >> h 1("banana", 1000) => 26 The ordinal value of ‘b’ is 1 Strings starting ‘ba’ go in row 1 * 26 + 0 >> radix 26("banana") => 12110202 >> hr("banana", 1000) => 202 The value of x mod 1000 is determined by the last three digits in x

Hash Functions in Hash. Lab ✦ The module also has implementations of the other hash functions: >> h 0("banana", 1000) => 1 >> h 1("banana", 1000) => 26 The ordinal value of ‘b’ is 1 Strings starting ‘ba’ go in row 1 * 26 + 0 >> radix 26("banana") => 12110202 >> hr("banana", 1000) => 202 The value of x mod 1000 is determined by the last three digits in x

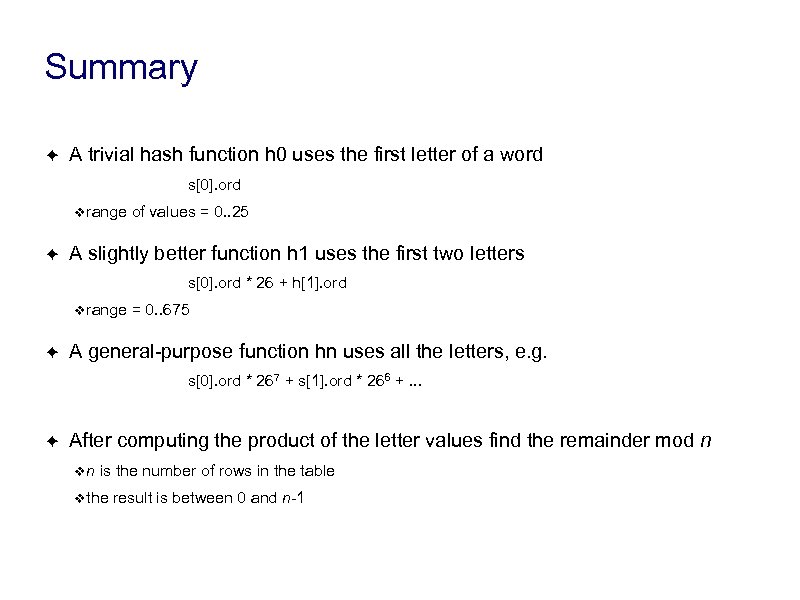

Summary ✦ A trivial hash function h 0 uses the first letter of a word s[0]. ord ❖range ✦ of values = 0. . 25 A slightly better function h 1 uses the first two letters s[0]. ord * 26 + h[1]. ord ❖range ✦ = 0. . 675 A general-purpose function hn uses all the letters, e. g. s[0]. ord * 267 + s[1]. ord * 266 +. . . ✦ After computing the product of the letter values find the remainder mod n ❖n is the number of rows in the table ❖the result is between 0 and n-1

Summary ✦ A trivial hash function h 0 uses the first letter of a word s[0]. ord ❖range ✦ of values = 0. . 25 A slightly better function h 1 uses the first two letters s[0]. ord * 26 + h[1]. ord ❖range ✦ = 0. . 675 A general-purpose function hn uses all the letters, e. g. s[0]. ord * 267 + s[1]. ord * 266 +. . . ✦ After computing the product of the letter values find the remainder mod n ❖n is the number of rows in the table ❖the result is between 0 and n-1

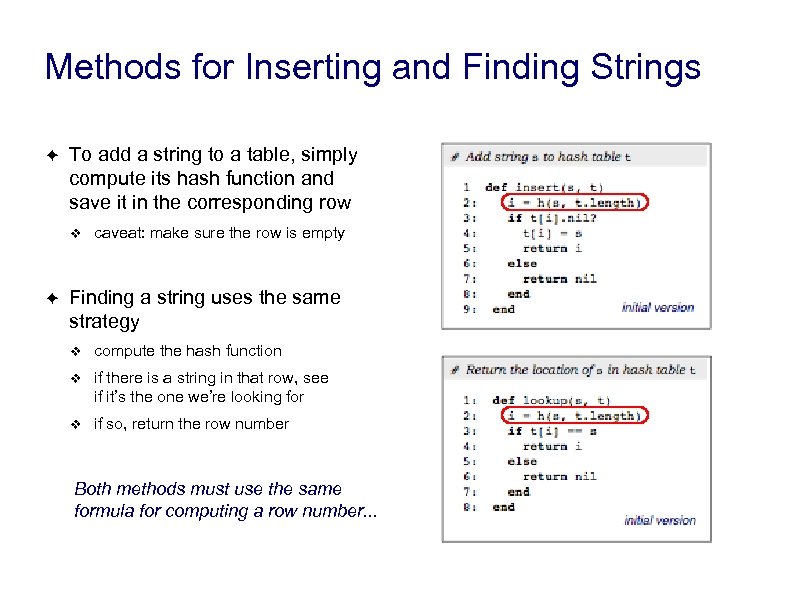

Methods for Inserting and Finding Strings ✦ To add a string to a table, simply compute its hash function and save it in the corresponding row ❖ ✦ caveat: make sure the row is empty Finding a string uses the same strategy ❖ compute the hash function ❖ if there is a string in that row, see if it’s the one we’re looking for ❖ if so, return the row number Both methods must use the same formula for computing a row number. . .

Methods for Inserting and Finding Strings ✦ To add a string to a table, simply compute its hash function and save it in the corresponding row ❖ ✦ caveat: make sure the row is empty Finding a string uses the same strategy ❖ compute the hash function ❖ if there is a string in that row, see if it’s the one we’re looking for ❖ if so, return the row number Both methods must use the same formula for computing a row number. . .

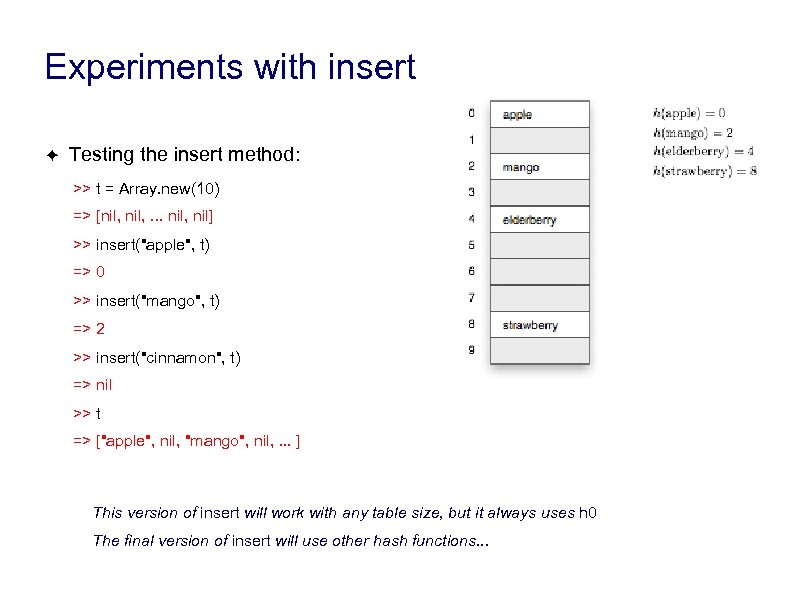

Experiments with insert ✦ Testing the insert method: >> t = Array. new(10) => [nil, . . . nil, nil] >> insert("apple", t) => 0 >> insert("mango", t) => 2 >> insert("cinnamon", t) => nil >> t => ["apple", nil, "mango", nil, . . . ] This version of insert will work with any table size, but it always uses h 0 The final version of insert will use other hash functions. . .

Experiments with insert ✦ Testing the insert method: >> t = Array. new(10) => [nil, . . . nil, nil] >> insert("apple", t) => 0 >> insert("mango", t) => 2 >> insert("cinnamon", t) => nil >> t => ["apple", nil, "mango", nil, . . . ] This version of insert will work with any table size, but it always uses h 0 The final version of insert will use other hash functions. . .

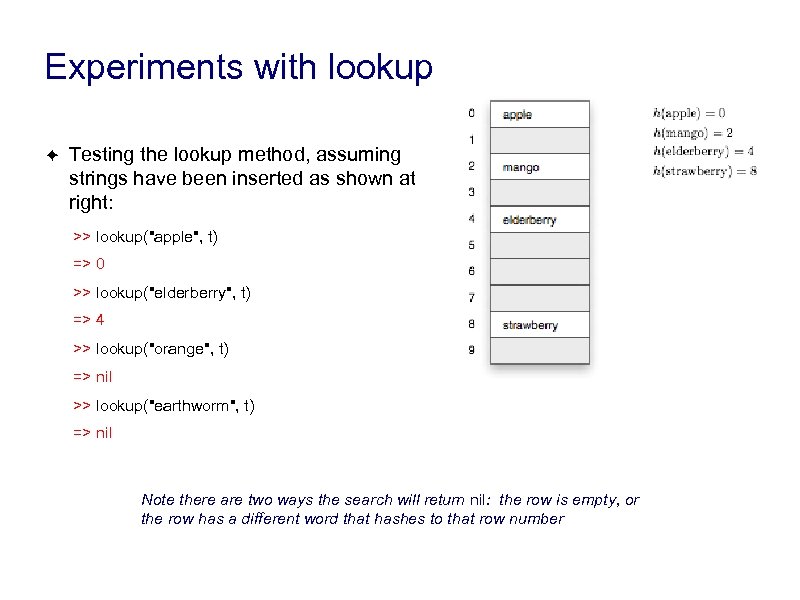

Experiments with lookup ✦ Testing the lookup method, assuming strings have been inserted as shown at right: >> lookup("apple", t) => 0 >> lookup("elderberry", t) => 4 >> lookup("orange", t) => nil >> lookup("earthworm", t) => nil Note there are two ways the search will return nil: the row is empty, or the row has a different word that hashes to that row number

Experiments with lookup ✦ Testing the lookup method, assuming strings have been inserted as shown at right: >> lookup("apple", t) => 0 >> lookup("elderberry", t) => 4 >> lookup("orange", t) => nil >> lookup("earthworm", t) => nil Note there are two ways the search will return nil: the row is empty, or the row has a different word that hashes to that row number

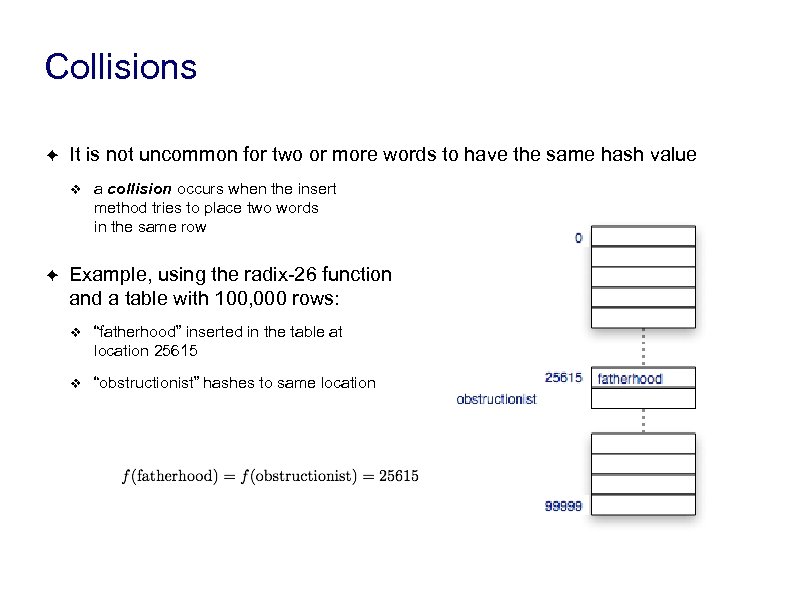

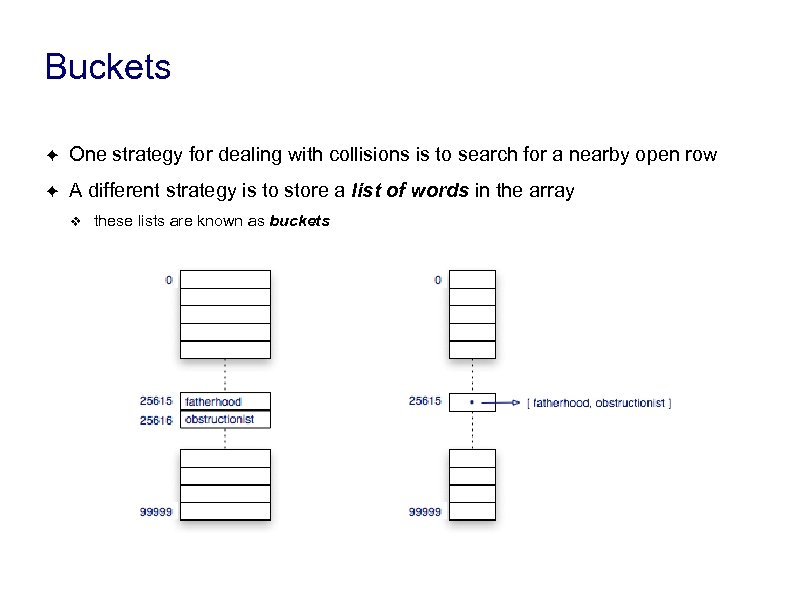

Collisions ✦ It is not uncommon for two or more words to have the same hash value ❖ ✦ a collision occurs when the insert method tries to place two words in the same row Example, using the radix-26 function and a table with 100, 000 rows: ❖ “fatherhood” inserted in the table at location 25615 ❖ “obstructionist” hashes to same location

Collisions ✦ It is not uncommon for two or more words to have the same hash value ❖ ✦ a collision occurs when the insert method tries to place two words in the same row Example, using the radix-26 function and a table with 100, 000 rows: ❖ “fatherhood” inserted in the table at location 25615 ❖ “obstructionist” hashes to same location

Bad Pun When Words Collide 1951 Sci Fi Thriller

Bad Pun When Words Collide 1951 Sci Fi Thriller

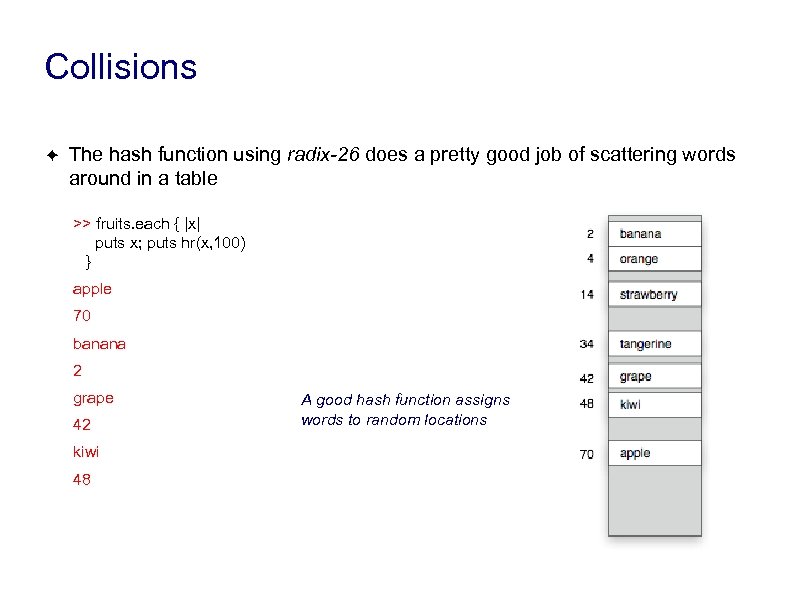

Collisions ✦ The hash function using radix-26 does a pretty good job of scattering words around in a table >> fruits. each { |x| puts x; puts hr(x, 100) } apple 70 banana 2 grape 42 kiwi 48 A good hash function assigns words to random locations

Collisions ✦ The hash function using radix-26 does a pretty good job of scattering words around in a table >> fruits. each { |x| puts x; puts hr(x, 100) } apple 70 banana 2 grape 42 kiwi 48 A good hash function assigns words to random locations

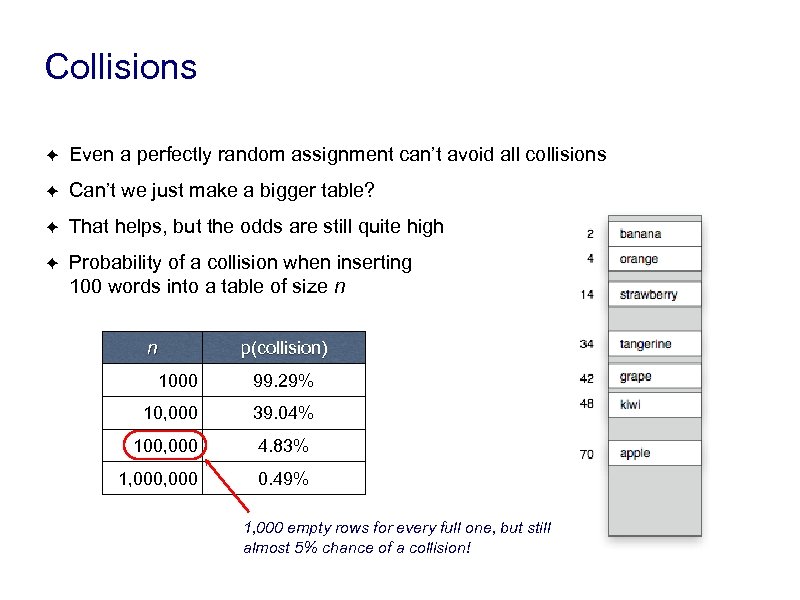

Collisions ✦ Even a perfectly random assignment can’t avoid all collisions ✦ Can’t we just make a bigger table? ✦ That helps, but the odds are still quite high ✦ Probability of a collision when inserting 100 words into a table of size n n p(collision) 1000 99. 29% 10, 000 39. 04% 100, 000 4. 83% 1, 000 0. 49% 1, 000 empty rows for every full one, but still almost 5% chance of a collision!

Collisions ✦ Even a perfectly random assignment can’t avoid all collisions ✦ Can’t we just make a bigger table? ✦ That helps, but the odds are still quite high ✦ Probability of a collision when inserting 100 words into a table of size n n p(collision) 1000 99. 29% 10, 000 39. 04% 100, 000 4. 83% 1, 000 0. 49% 1, 000 empty rows for every full one, but still almost 5% chance of a collision!

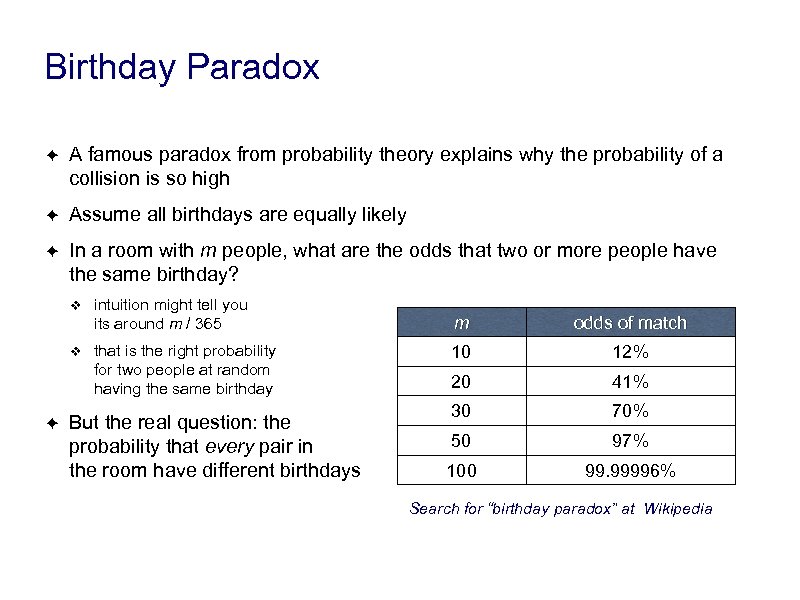

Birthday Paradox ✦ A famous paradox from probability theory explains why the probability of a collision is so high ✦ Assume all birthdays are equally likely ✦ In a room with m people, what are the odds that two or more people have the same birthday? ❖ ❖ ✦ intuition might tell you its around m / 365 that is the right probability for two people at random having the same birthday But the real question: the probability that every pair in the room have different birthdays m odds of match 10 12% 20 41% 30 70% 50 97% 100 99. 99996% Search for “birthday paradox” at Wikipedia

Birthday Paradox ✦ A famous paradox from probability theory explains why the probability of a collision is so high ✦ Assume all birthdays are equally likely ✦ In a room with m people, what are the odds that two or more people have the same birthday? ❖ ❖ ✦ intuition might tell you its around m / 365 that is the right probability for two people at random having the same birthday But the real question: the probability that every pair in the room have different birthdays m odds of match 10 12% 20 41% 30 70% 50 97% 100 99. 99996% Search for “birthday paradox” at Wikipedia

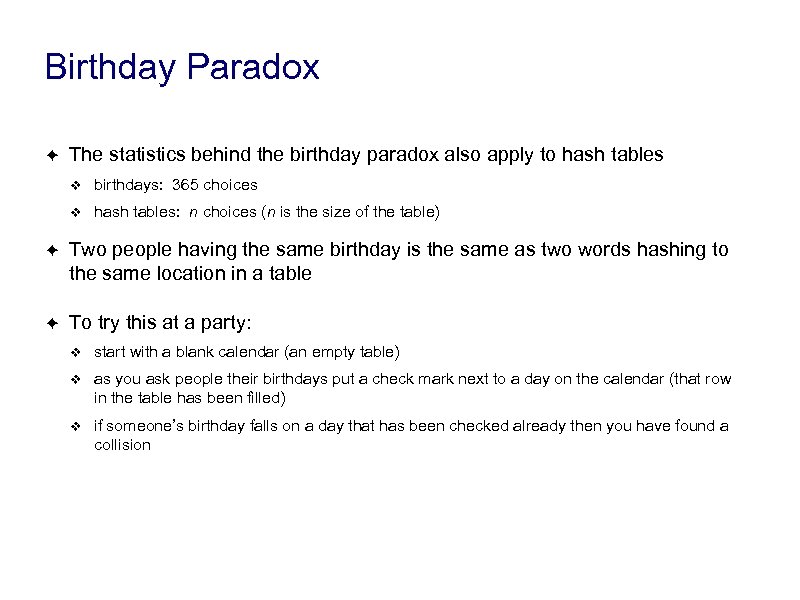

Birthday Paradox ✦ The statistics behind the birthday paradox also apply to hash tables ❖ birthdays: 365 choices ❖ hash tables: n choices (n is the size of the table) ✦ Two people having the same birthday is the same as two words hashing to the same location in a table ✦ To try this at a party: ❖ start with a blank calendar (an empty table) ❖ as you ask people their birthdays put a check mark next to a day on the calendar (that row in the table has been filled) ❖ if someone’s birthday falls on a day that has been checked already then you have found a collision

Birthday Paradox ✦ The statistics behind the birthday paradox also apply to hash tables ❖ birthdays: 365 choices ❖ hash tables: n choices (n is the size of the table) ✦ Two people having the same birthday is the same as two words hashing to the same location in a table ✦ To try this at a party: ❖ start with a blank calendar (an empty table) ❖ as you ask people their birthdays put a check mark next to a day on the calendar (that row in the table has been filled) ❖ if someone’s birthday falls on a day that has been checked already then you have found a collision

Buckets ✦ One strategy for dealing with collisions is to search for a nearby open row ✦ A different strategy is to store a list of words in the array ❖ these lists are known as buckets

Buckets ✦ One strategy for dealing with collisions is to search for a nearby open row ✦ A different strategy is to store a list of words in the array ❖ these lists are known as buckets

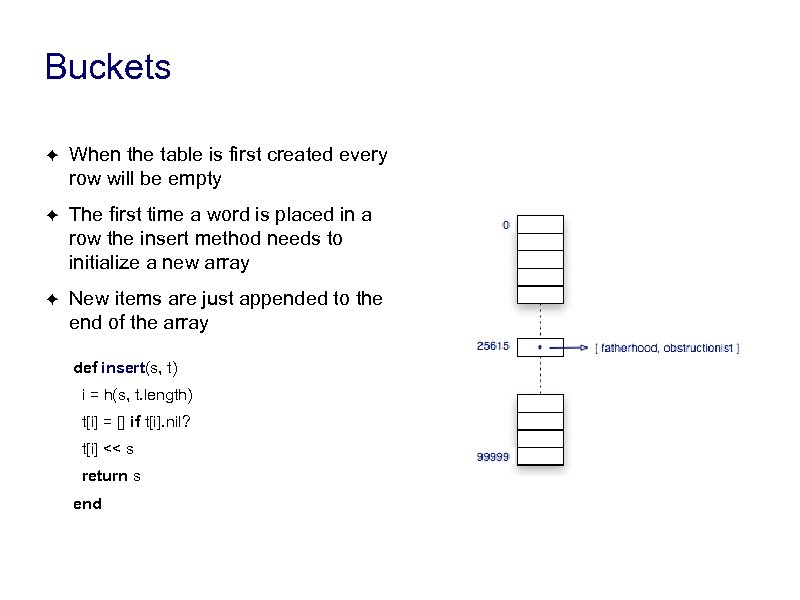

Buckets ✦ When the table is first created every row will be empty ✦ The first time a word is placed in a row the insert method needs to initialize a new array ✦ New items are just appended to the end of the array def insert(s, t) i = h(s, t. length) t[i] = [] if t[i]. nil? t[i] << s return s end

Buckets ✦ When the table is first created every row will be empty ✦ The first time a word is placed in a row the insert method needs to initialize a new array ✦ New items are just appended to the end of the array def insert(s, t) i = h(s, t. length) t[i] = [] if t[i]. nil? t[i] << s return s end

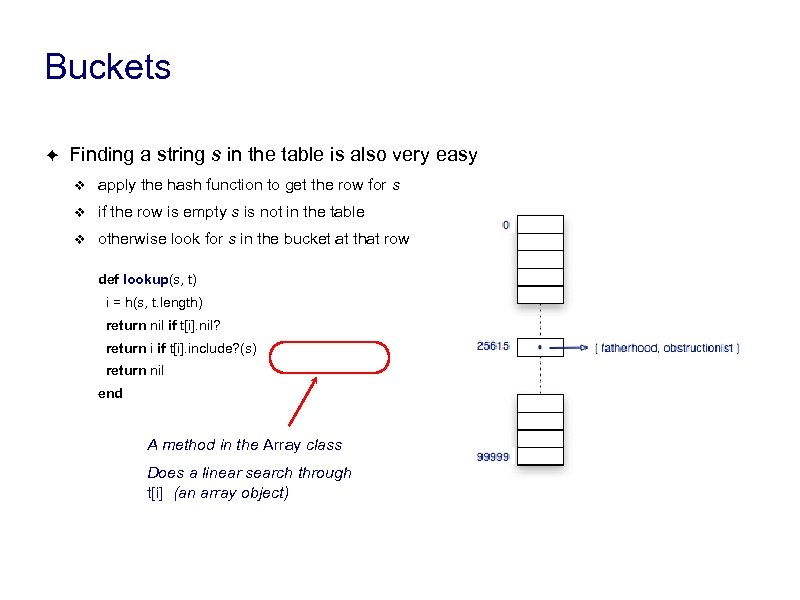

Buckets ✦ Finding a string s in the table is also very easy ❖ apply the hash function to get the row for s ❖ if the row is empty s is not in the table ❖ otherwise look for s in the bucket at that row def lookup(s, t) i = h(s, t. length) return nil if t[i]. nil? return i if t[i]. include? (s) return nil end A method in the Array class Does a linear search through t[i] (an array object)

Buckets ✦ Finding a string s in the table is also very easy ❖ apply the hash function to get the row for s ❖ if the row is empty s is not in the table ❖ otherwise look for s in the bucket at that row def lookup(s, t) i = h(s, t. length) return nil if t[i]. nil? return i if t[i]. include? (s) return nil end A method in the Array class Does a linear search through t[i] (an array object)

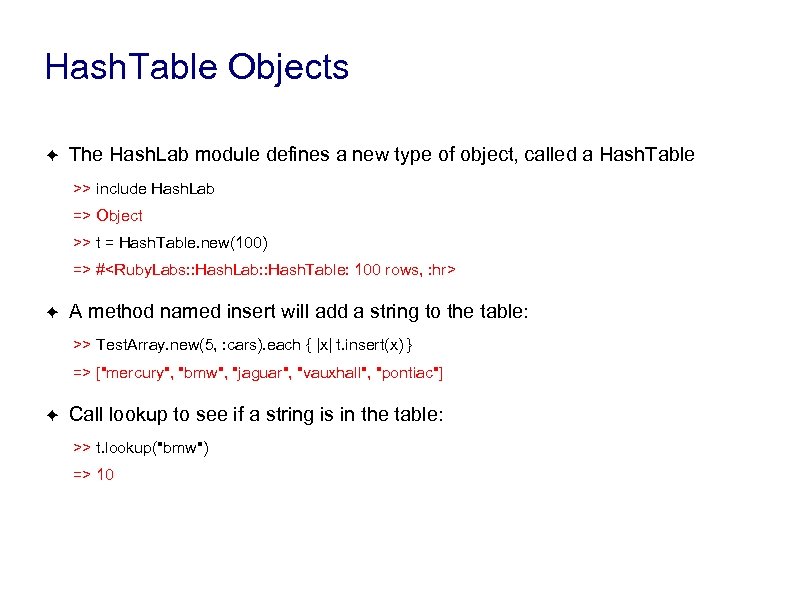

Hash. Table Objects ✦ The Hash. Lab module defines a new type of object, called a Hash. Table >> include Hash. Lab => Object >> t = Hash. Table. new(100) => #

Hash. Table Objects ✦ The Hash. Lab module defines a new type of object, called a Hash. Table >> include Hash. Lab => Object >> t = Hash. Table. new(100) => #

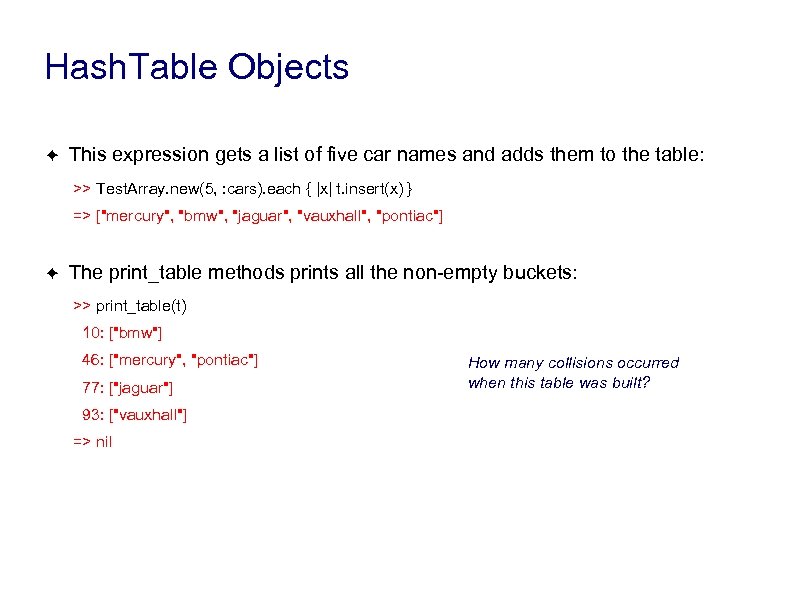

Hash. Table Objects ✦ This expression gets a list of five car names and adds them to the table: >> Test. Array. new(5, : cars). each { |x| t. insert(x) } => ["mercury", "bmw", "jaguar", "vauxhall", "pontiac"] ✦ The print_table methods prints all the non-empty buckets: >> print_table(t) 10: ["bmw"] 46: ["mercury", "pontiac"] 77: ["jaguar"] 93: ["vauxhall"] => nil How many collisions occurred when this table was built?

Hash. Table Objects ✦ This expression gets a list of five car names and adds them to the table: >> Test. Array. new(5, : cars). each { |x| t. insert(x) } => ["mercury", "bmw", "jaguar", "vauxhall", "pontiac"] ✦ The print_table methods prints all the non-empty buckets: >> print_table(t) 10: ["bmw"] 46: ["mercury", "pontiac"] 77: ["jaguar"] 93: ["vauxhall"] => nil How many collisions occurred when this table was built?

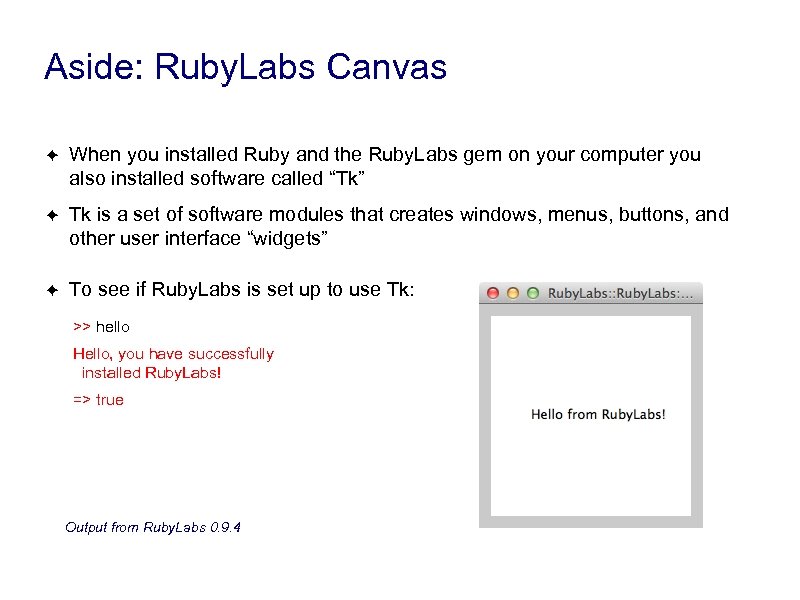

Aside: Ruby. Labs Canvas ✦ When you installed Ruby and the Ruby. Labs gem on your computer you also installed software called “Tk” ✦ Tk is a set of software modules that creates windows, menus, buttons, and other user interface “widgets” ✦ To see if Ruby. Labs is set up to use Tk: >> hello Hello, you have successfully installed Ruby. Labs! => true Output from Ruby. Labs 0. 9. 4

Aside: Ruby. Labs Canvas ✦ When you installed Ruby and the Ruby. Labs gem on your computer you also installed software called “Tk” ✦ Tk is a set of software modules that creates windows, menus, buttons, and other user interface “widgets” ✦ To see if Ruby. Labs is set up to use Tk: >> hello Hello, you have successfully installed Ruby. Labs! => true Output from Ruby. Labs 0. 9. 4

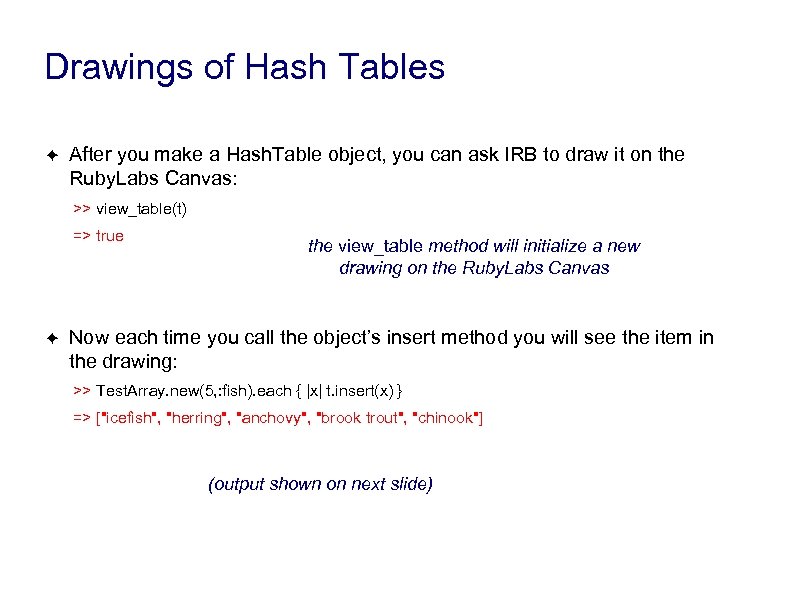

Drawings of Hash Tables ✦ After you make a Hash. Table object, you can ask IRB to draw it on the Ruby. Labs Canvas: >> view_table(t) => true ✦ the view_table method will initialize a new drawing on the Ruby. Labs Canvas Now each time you call the object’s insert method you will see the item in the drawing: >> Test. Array. new(5, : fish). each { |x| t. insert(x) } => ["icefish", "herring", "anchovy", "brook trout", "chinook"] (output shown on next slide)

Drawings of Hash Tables ✦ After you make a Hash. Table object, you can ask IRB to draw it on the Ruby. Labs Canvas: >> view_table(t) => true ✦ the view_table method will initialize a new drawing on the Ruby. Labs Canvas Now each time you call the object’s insert method you will see the item in the drawing: >> Test. Array. new(5, : fish). each { |x| t. insert(x) } => ["icefish", "herring", "anchovy", "brook trout", "chinook"] (output shown on next slide)

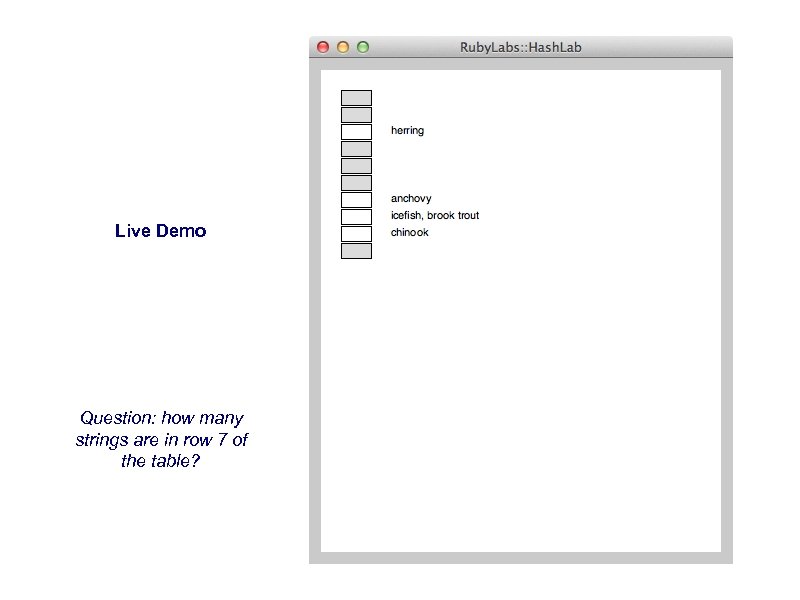

Live Demo Question: how many strings are in row 7 of the table?

Live Demo Question: how many strings are in row 7 of the table?

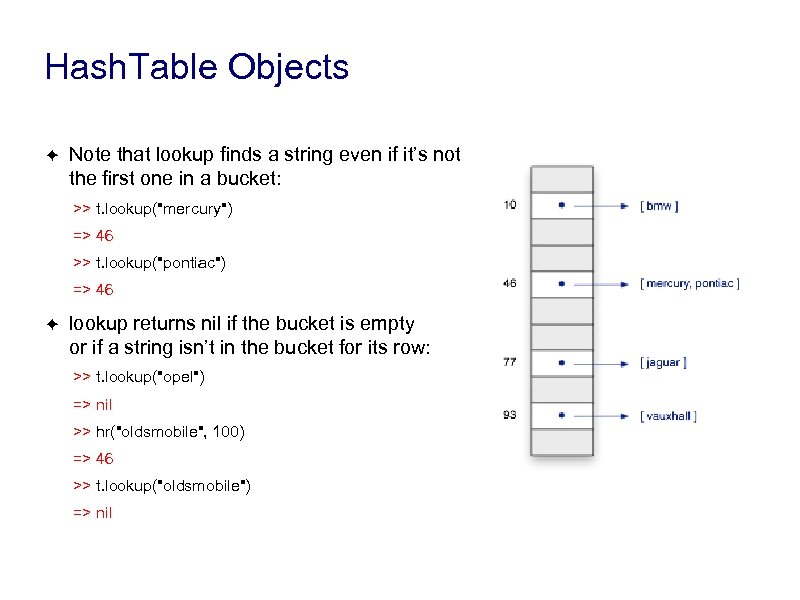

Hash. Table Objects ✦ Note that lookup finds a string even if it’s not the first one in a bucket: >> t. lookup("mercury") => 46 >> t. lookup("pontiac") => 46 ✦ lookup returns nil if the bucket is empty or if a string isn’t in the bucket for its row: >> t. lookup("opel") => nil >> hr("oldsmobile", 100) => 46 >> t. lookup("oldsmobile") => nil

Hash. Table Objects ✦ Note that lookup finds a string even if it’s not the first one in a bucket: >> t. lookup("mercury") => 46 >> t. lookup("pontiac") => 46 ✦ lookup returns nil if the bucket is empty or if a string isn’t in the bucket for its row: >> t. lookup("opel") => nil >> hr("oldsmobile", 100) => 46 >> t. lookup("oldsmobile") => nil

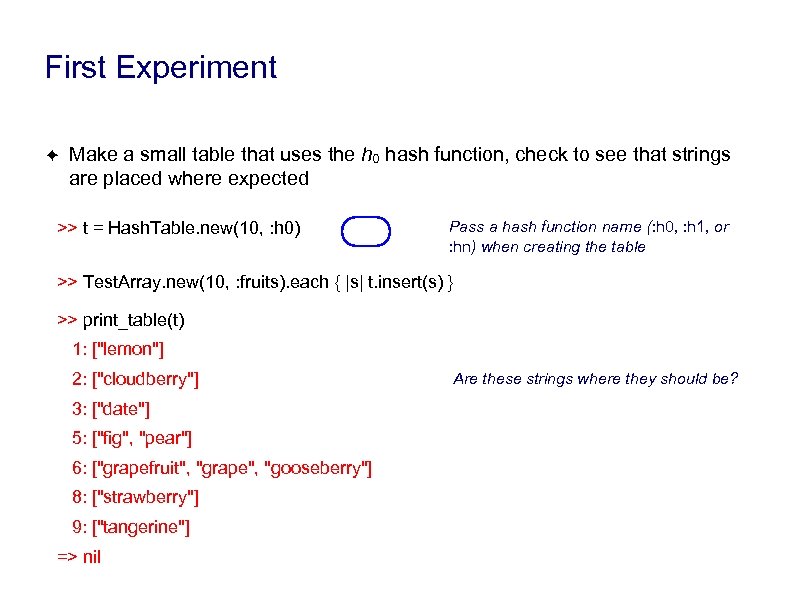

First Experiment ✦ Make a small table that uses the h 0 hash function, check to see that strings are placed where expected >> t = Hash. Table. new(10, : h 0) Pass a hash function name (: h 0, : h 1, or : hn) when creating the table >> Test. Array. new(10, : fruits). each { |s| t. insert(s) } >> print_table(t) 1: ["lemon"] 2: ["cloudberry"] 3: ["date"] 5: ["fig", "pear"] 6: ["grapefruit", "grape", "gooseberry"] 8: ["strawberry"] 9: ["tangerine"] => nil Are these strings where they should be?

First Experiment ✦ Make a small table that uses the h 0 hash function, check to see that strings are placed where expected >> t = Hash. Table. new(10, : h 0) Pass a hash function name (: h 0, : h 1, or : hn) when creating the table >> Test. Array. new(10, : fruits). each { |s| t. insert(s) } >> print_table(t) 1: ["lemon"] 2: ["cloudberry"] 3: ["date"] 5: ["fig", "pear"] 6: ["grapefruit", "grape", "gooseberry"] 8: ["strawberry"] 9: ["tangerine"] => nil Are these strings where they should be?

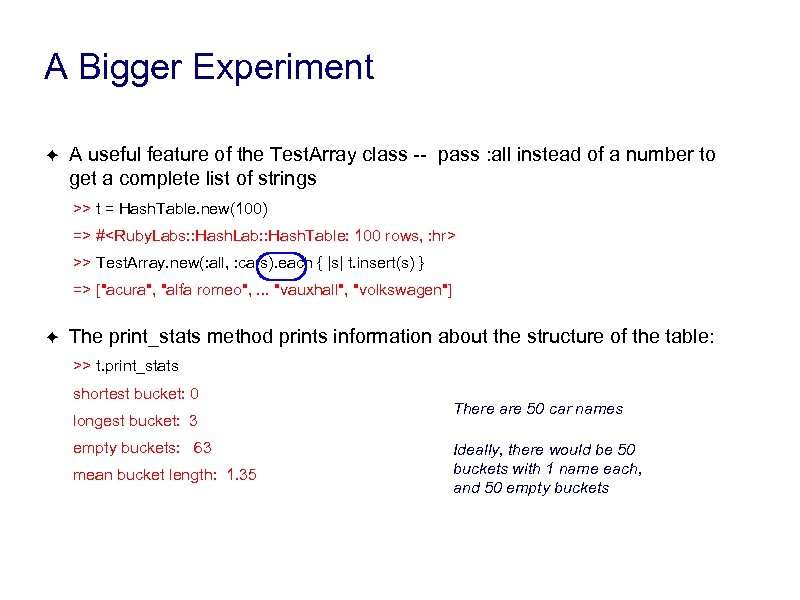

A Bigger Experiment ✦ A useful feature of the Test. Array class -- pass : all instead of a number to get a complete list of strings >> t = Hash. Table. new(100) => #

A Bigger Experiment ✦ A useful feature of the Test. Array class -- pass : all instead of a number to get a complete list of strings >> t = Hash. Table. new(100) => #

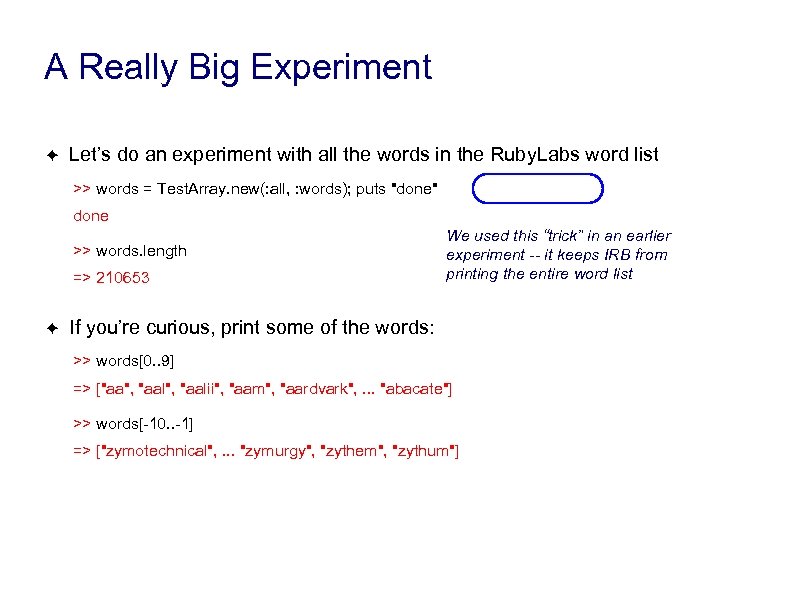

A Really Big Experiment ✦ Let’s do an experiment with all the words in the Ruby. Labs word list >> words = Test. Array. new(: all, : words); puts "done" done >> words. length => 210653 ✦ We used this “trick” in an earlier experiment -- it keeps IRB from printing the entire word list If you’re curious, print some of the words: >> words[0. . 9] => ["aa", "aalii", "aam", "aardvark", . . . "abacate"] >> words[-10. . -1] => ["zymotechnical", . . . "zymurgy", "zythem", "zythum"]

A Really Big Experiment ✦ Let’s do an experiment with all the words in the Ruby. Labs word list >> words = Test. Array. new(: all, : words); puts "done" done >> words. length => 210653 ✦ We used this “trick” in an earlier experiment -- it keeps IRB from printing the entire word list If you’re curious, print some of the words: >> words[0. . 9] => ["aa", "aalii", "aam", "aardvark", . . . "abacate"] >> words[-10. . -1] => ["zymotechnical", . . . "zymurgy", "zythem", "zythum"]

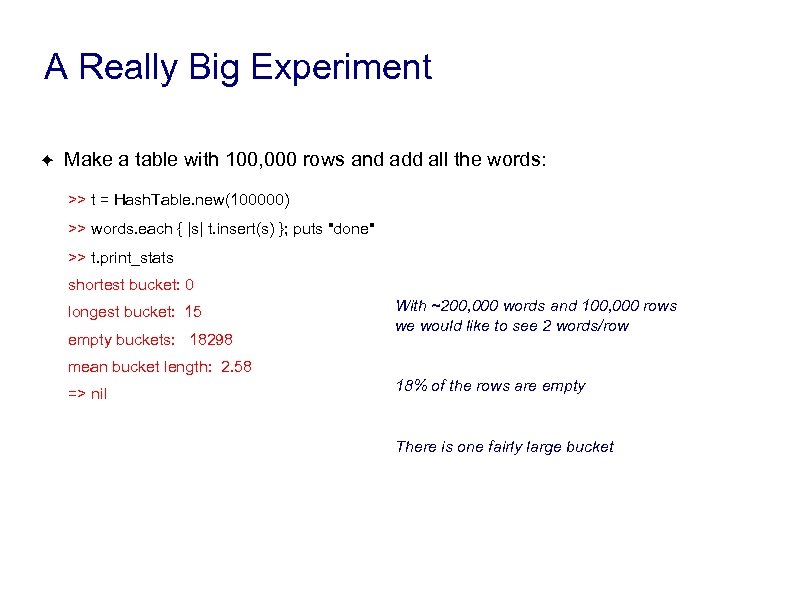

A Really Big Experiment ✦ Make a table with 100, 000 rows and add all the words: >> t = Hash. Table. new(100000) >> words. each { |s| t. insert(s) }; puts "done" >> t. print_stats shortest bucket: 0 longest bucket: 15 empty buckets: 18298 With ~200, 000 words and 100, 000 rows we would like to see 2 words/row mean bucket length: 2. 58 => nil 18% of the rows are empty There is one fairly large bucket

A Really Big Experiment ✦ Make a table with 100, 000 rows and add all the words: >> t = Hash. Table. new(100000) >> words. each { |s| t. insert(s) }; puts "done" >> t. print_stats shortest bucket: 0 longest bucket: 15 empty buckets: 18298 With ~200, 000 words and 100, 000 rows we would like to see 2 words/row mean bucket length: 2. 58 => nil 18% of the rows are empty There is one fairly large bucket

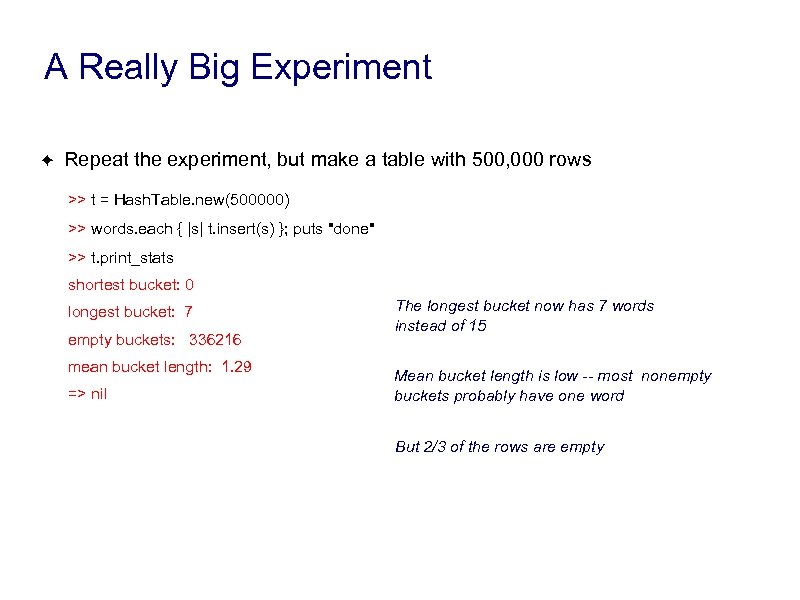

A Really Big Experiment ✦ Repeat the experiment, but make a table with 500, 000 rows >> t = Hash. Table. new(500000) >> words. each { |s| t. insert(s) }; puts "done" >> t. print_stats shortest bucket: 0 longest bucket: 7 empty buckets: 336216 mean bucket length: 1. 29 => nil The longest bucket now has 7 words instead of 15 Mean bucket length is low -- most nonempty buckets probably have one word But 2/3 of the rows are empty

A Really Big Experiment ✦ Repeat the experiment, but make a table with 500, 000 rows >> t = Hash. Table. new(500000) >> words. each { |s| t. insert(s) }; puts "done" >> t. print_stats shortest bucket: 0 longest bucket: 7 empty buckets: 336216 mean bucket length: 1. 29 => nil The longest bucket now has 7 words instead of 15 Mean bucket length is low -- most nonempty buckets probably have one word But 2/3 of the rows are empty

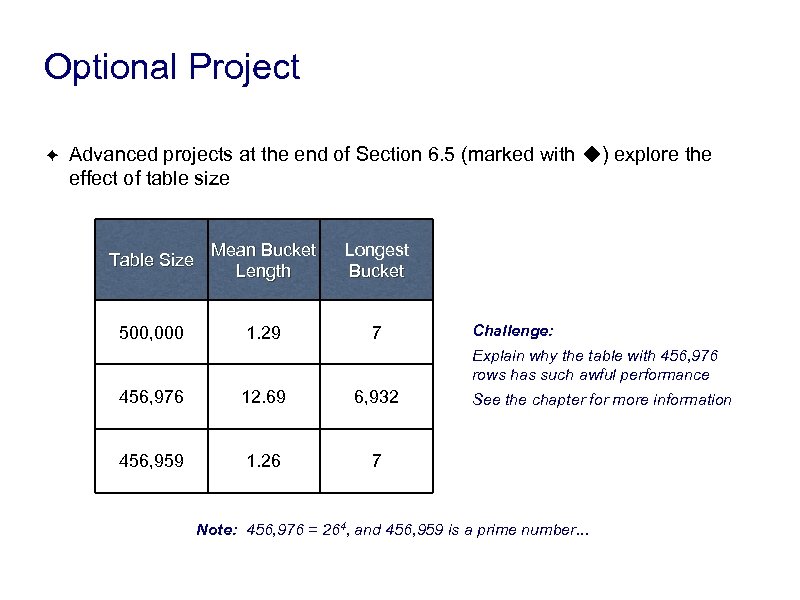

Optional Project ✦ Advanced projects at the end of Section 6. 5 (marked with ◆) explore the effect of table size Table Size Mean Bucket Length Longest Bucket 500, 000 1. 29 7 Challenge: Explain why the table with 456, 976 rows has such awful performance 456, 976 12. 69 6, 932 456, 959 1. 26 7 See the chapter for more information Note: 456, 976 = 264, and 456, 959 is a prime number. . .

Optional Project ✦ Advanced projects at the end of Section 6. 5 (marked with ◆) explore the effect of table size Table Size Mean Bucket Length Longest Bucket 500, 000 1. 29 7 Challenge: Explain why the table with 456, 976 rows has such awful performance 456, 976 12. 69 6, 932 456, 959 1. 26 7 See the chapter for more information Note: 456, 976 = 264, and 456, 959 is a prime number. . .

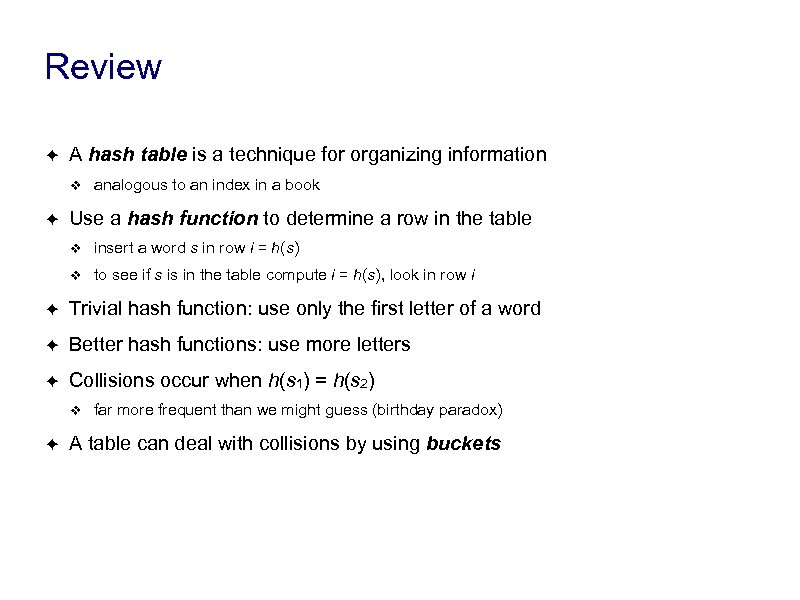

Review ✦ A hash table is a technique for organizing information ❖ ✦ analogous to an index in a book Use a hash function to determine a row in the table ❖ insert a word s in row i = h(s) ❖ to see if s is in the table compute i = h(s), look in row i ✦ Trivial hash function: use only the first letter of a word ✦ Better hash functions: use more letters ✦ Collisions occur when h(s 1) = h(s 2) ❖ ✦ far more frequent than we might guess (birthday paradox) A table can deal with collisions by using buckets

Review ✦ A hash table is a technique for organizing information ❖ ✦ analogous to an index in a book Use a hash function to determine a row in the table ❖ insert a word s in row i = h(s) ❖ to see if s is in the table compute i = h(s), look in row i ✦ Trivial hash function: use only the first letter of a word ✦ Better hash functions: use more letters ✦ Collisions occur when h(s 1) = h(s 2) ❖ ✦ far more frequent than we might guess (birthday paradox) A table can deal with collisions by using buckets

Google ✦ As an example of how these ideas are used in practice let’s look at how Google does its searches ✦ Google uses a “web crawler” to go out on the internet and fetch pages ❖ ✦ their goal is to get a copy of every page on the internet Issues: ❖ don’t get dynamic pages (e. g. from on-line games) ❖ respect privacy: some sites don’t want to be searched ‣ ‣ ✦ example: course web site with solutions to problem sets book publishers ask faculty members to protect the pages containing solutions Once the pages are collected organize them so searches are fast ❖ main index or “forward index” links a page ID to its location in the system ❖ a “reverse index” is an index for every word found on a page ❖ connects words to pages that contain them

Google ✦ As an example of how these ideas are used in practice let’s look at how Google does its searches ✦ Google uses a “web crawler” to go out on the internet and fetch pages ❖ ✦ their goal is to get a copy of every page on the internet Issues: ❖ don’t get dynamic pages (e. g. from on-line games) ❖ respect privacy: some sites don’t want to be searched ‣ ‣ ✦ example: course web site with solutions to problem sets book publishers ask faculty members to protect the pages containing solutions Once the pages are collected organize them so searches are fast ❖ main index or “forward index” links a page ID to its location in the system ❖ a “reverse index” is an index for every word found on a page ❖ connects words to pages that contain them

Google ✦ When processing a page to build the reverse index, consider the context ❖ ❖ ✦ words that occur in headlines (e. g. page titles) and section headers are given a higher weight than words appearing in the page body extract words appearing in links What made Google different: rank pages by “importance” ❖ ✦ an important page is one that others refer to Example -- search for “ducks” (ca. 2008): ❖ goducks. com (UO Athletic Department) ❖ wikipedia. org/wiki/Duck (Wikipedia page for “duck”) ❖ www. ducks. org (Ducks Unlimited, a conservation organization) ❖ ducks. nhl. com (Anaheim Mighty Ducks, a pro hockey team)

Google ✦ When processing a page to build the reverse index, consider the context ❖ ❖ ✦ words that occur in headlines (e. g. page titles) and section headers are given a higher weight than words appearing in the page body extract words appearing in links What made Google different: rank pages by “importance” ❖ ✦ an important page is one that others refer to Example -- search for “ducks” (ca. 2008): ❖ goducks. com (UO Athletic Department) ❖ wikipedia. org/wiki/Duck (Wikipedia page for “duck”) ❖ www. ducks. org (Ducks Unlimited, a conservation organization) ❖ ducks. nhl. com (Anaheim Mighty Ducks, a pro hockey team)

Google ✦ From a 1998 paper: “After each document is parsed. . . every word is converted into a word. ID by using an in-memory hash table” The Anatomy of a Large-Scale Hypertextual Web Search Engine, Sergey Brin and Lawrence Page, Computer Networks 30(1 -7): 107 -117 (1998) (search “google. pdf” to get a copy from a Stanford publication library) ✦ Some statistics from that era: ❖ the search engine used a “lexicon” of 14, 000 words ❖ extracted from 24, 000 pages ❖ pages took up 147 GB ❖ word index required 37 GB ❖ word list (lexicon) was 293 MB

Google ✦ From a 1998 paper: “After each document is parsed. . . every word is converted into a word. ID by using an in-memory hash table” The Anatomy of a Large-Scale Hypertextual Web Search Engine, Sergey Brin and Lawrence Page, Computer Networks 30(1 -7): 107 -117 (1998) (search “google. pdf” to get a copy from a Stanford publication library) ✦ Some statistics from that era: ❖ the search engine used a “lexicon” of 14, 000 words ❖ extracted from 24, 000 pages ❖ pages took up 147 GB ❖ word index required 37 GB ❖ word list (lexicon) was 293 MB

Google ✦ Is a lexicon of 14, 000 entries big enough? ❖ ✦ how many words does the average person use? know? Depending on how you define “word” the English language has between 100, 000 and 250, 000 words ❖ is “hot dog” a word? ❖ how does punctuation work? is “pseudocode” the same as “pseudo-code”? ❖ do you include place names? people? species names? ( “Yersinia pestis” ? )

Google ✦ Is a lexicon of 14, 000 entries big enough? ❖ ✦ how many words does the average person use? know? Depending on how you define “word” the English language has between 100, 000 and 250, 000 words ❖ is “hot dog” a word? ❖ how does punctuation work? is “pseudocode” the same as “pseudo-code”? ❖ do you include place names? people? species names? ( “Yersinia pestis” ? )