a2ceb450f59f709e945eb3bd5ba492ea.ppt

- Количество слайдов: 74

Slide 14 B. 77 Object-Oriented and Classical Software Engineering Sixth Edition, WCB/Mc. Graw-Hill, 2005 Stephen R. Schach srs@vuse. vanderbilt. edu © The Mc. Graw-Hill Companies, 2005

CHAPTER 14 — Unit B IMPLEMENTATION © The Mc. Graw-Hill Companies, 2005 Slide 14 B. 78

Slide 14 B. 79 Continued from Unit 14 A © The Mc. Graw-Hill Companies, 2005

14. 11 Black-Box Unit-testing Techniques Slide 14 B. 80 l Neither exhaustive testing to specifications nor exhaustive testing to code is feasible l The art of testing: 4 Select a small, manageable set of test cases to 4 Maximize the chances of detecting a fault, while 4 Minimizing the chances of wasting a test case l Every test case must detect a previously undetected fault © The Mc. Graw-Hill Companies, 2005

Black-Box Unit-testing Techniques (contd) Slide 14 B. 81 l We need a method that will highlight as many faults as possible 4 First black-box test cases (testing to specifications) 4 Then glass-box methods (testing to code) © The Mc. Graw-Hill Companies, 2005

14. 11. 1 Equivalence Testing and Boundary Value Analysis Slide 14 B. 82 l Example 4 The specifications for a DBMS state that the product must handle any number of records between 1 and 16, 383 (214– 1) 4 If the system can handle 34 records and 14, 870 records, then it probably will work fine for 8, 252 records l If the system works for any one test case in the range (1. . 16, 383), then it will probably work for any other test case in the range 4 Range (1. . 16, 383) constitutes an equivalence class © The Mc. Graw-Hill Companies, 2005

Equivalence Testing Slide 14 B. 83 l Any one member of an equivalence class is as good a test case as any other member of the equivalence class l Range (1. . 16, 383) defines three different equivalence classes: 4 Equivalence Class 1: Fewer than 1 record 4 Equivalence Class 2: Between 1 and 16, 383 records 4 Equivalence Class 3: More than 16, 383 records © The Mc. Graw-Hill Companies, 2005

Boundary Value Analysis l Slide 14 B. 84 Select test cases on or just to one side of the boundary of equivalence classes 4 This greatly increases the probability of detecting a fault © The Mc. Graw-Hill Companies, 2005

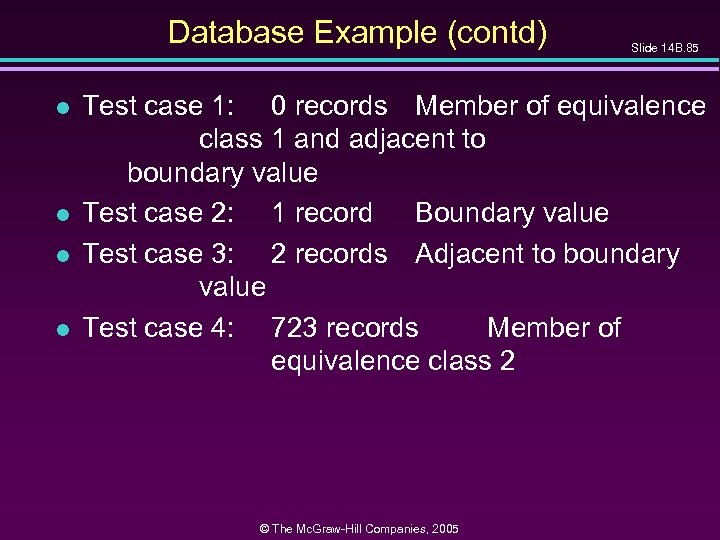

Database Example (contd) l l Slide 14 B. 85 Test case 1: 0 records Member of equivalence class 1 and adjacent to boundary value Test case 2: 1 record Boundary value Test case 3: 2 records Adjacent to boundary value Test case 4: 723 records Member of equivalence class 2 © The Mc. Graw-Hill Companies, 2005

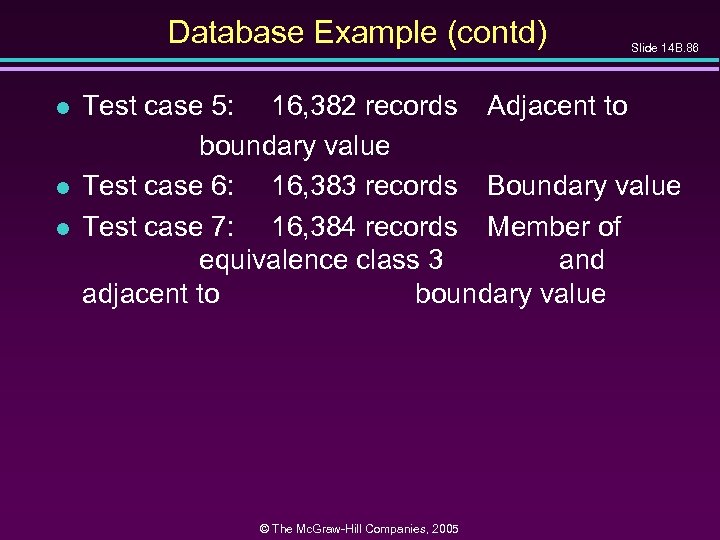

Database Example (contd) l l l Slide 14 B. 86 Test case 5: 16, 382 records Adjacent to boundary value Test case 6: 16, 383 records Boundary value Test case 7: 16, 384 records Member of equivalence class 3 and adjacent to boundary value © The Mc. Graw-Hill Companies, 2005

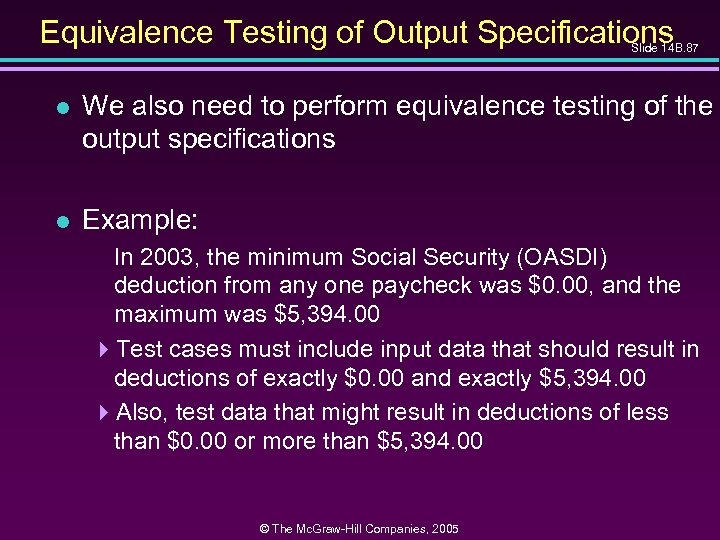

Equivalence Testing of Output Specifications Slide 14 B. 87 l We also need to perform equivalence testing of the output specifications l Example: In 2003, the minimum Social Security (OASDI) deduction from any one paycheck was $0. 00, and the maximum was $5, 394. 00 4 Test cases must include input data that should result in deductions of exactly $0. 00 and exactly $5, 394. 00 4 Also, test data that might result in deductions of less than $0. 00 or more than $5, 394. 00 © The Mc. Graw-Hill Companies, 2005

Overall Strategy l Slide 14 B. 88 Equivalence classes together with boundary value analysis to test both input specifications and output specifications 4 This approach generates a small set of test data with the potential of uncovering a large number of faults © The Mc. Graw-Hill Companies, 2005

14. 11. 2 Functional Testing l Slide 14 B. 89 An alternative form of black-box testing for classical software 4 We base the test data on the functionality of the code artifacts l Each item of functionality or function is identified l Test data are devised to test each (lower-level) function separately l Then, higher-level functions composed of these lower-level functions are tested © The Mc. Graw-Hill Companies, 2005

Functional Testing (contd) l Slide 14 B. 90 In practice, however 4 Higher-level functions are not always neatly constructed out of lower-level functions using the constructs of structured programming 4 Instead, the lower-level functions are often intertwined l Also, functionality boundaries do not always coincide with code artifact boundaries 4 The distinction between unit testing and integration testing becomes blurred 4 This problem also can arise in the object-oriented paradigm when messages are passed between objects © The Mc. Graw-Hill Companies, 2005

Functional Testing (contd) l Slide 14 B. 91 The resulting random interrelationships between code artifacts can have negative consequences for management 4 Milestones and deadlines can become ill-defined 4 The status of the project then becomes hard to determine © The Mc. Graw-Hill Companies, 2005

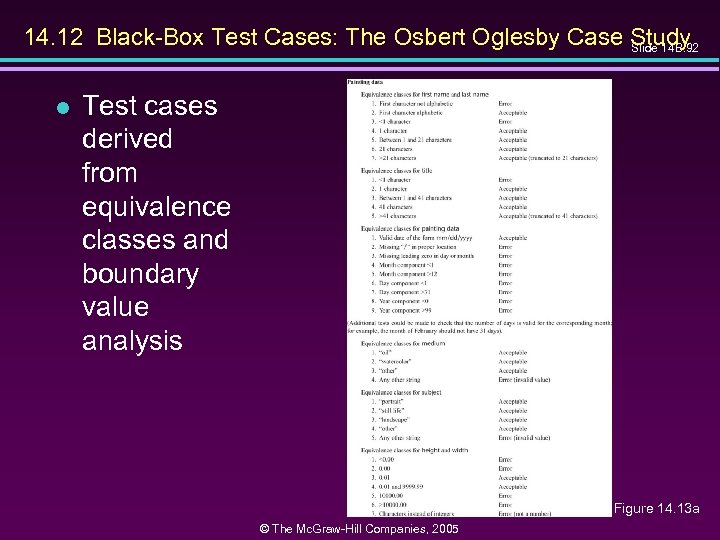

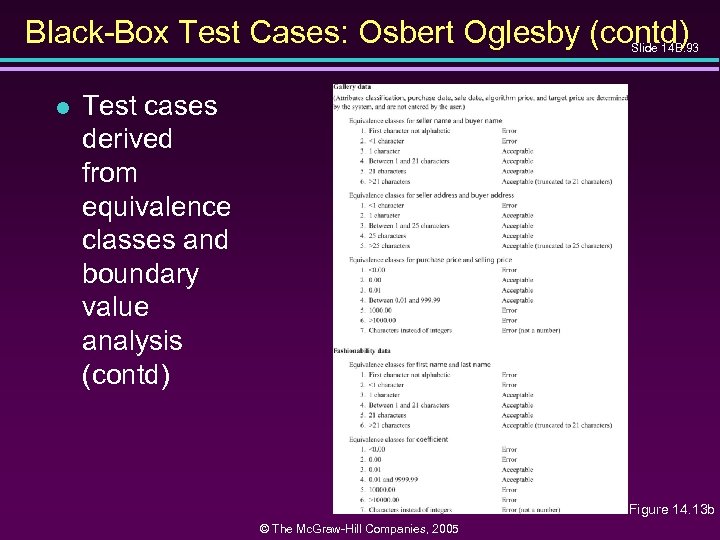

14. 12 Black-Box Test Cases: The Osbert Oglesby Case Study Slide 14 B. 92 l Test cases derived from equivalence classes and boundary value analysis Figure 14. 13 a © The Mc. Graw-Hill Companies, 2005

Black-Box Test Cases: Osbert Oglesby (contd) Slide 14 B. 93 l Test cases derived from equivalence classes and boundary value analysis (contd) Figure 14. 13 b © The Mc. Graw-Hill Companies, 2005

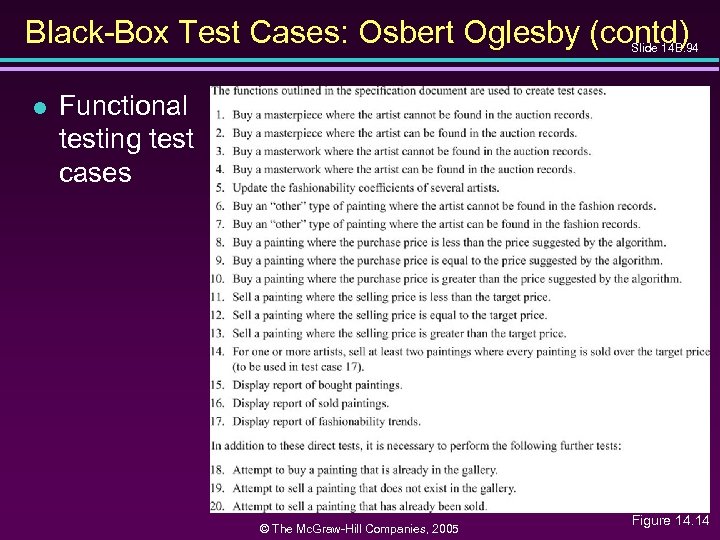

Black-Box Test Cases: Osbert Oglesby (contd) Slide 14 B. 94 l Functional testing test cases © The Mc. Graw-Hill Companies, 2005 Figure 14. 14

14. 13 Glass-Box Unit-Testing Techniques Slide 14 B. 95 l We will examine 4 Statement coverage 4 Branch coverage 4 Path coverage 4 Linear code sequences 4 All-definition-use path coverage © The Mc. Graw-Hill Companies, 2005

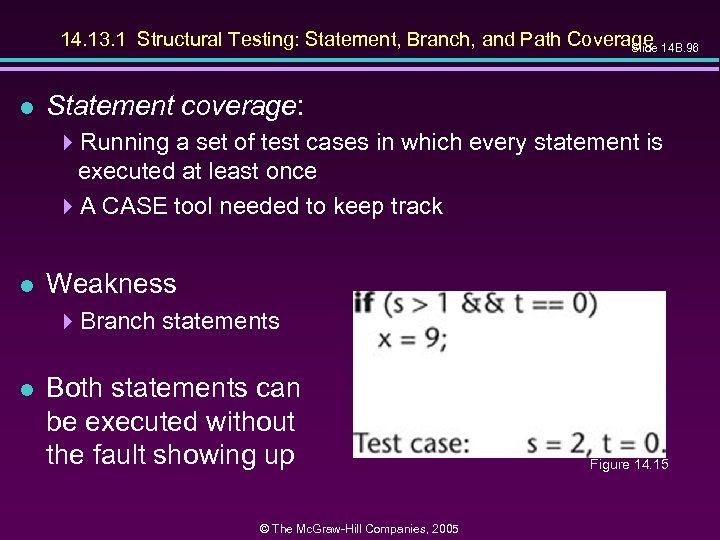

14. 13. 1 Structural Testing: Statement, Branch, and Path Coverage 14 B. 96 Slide l Statement coverage: 4 Running a set of test cases in which every statement is executed at least once 4 A CASE tool needed to keep track l Weakness 4 Branch statements l Both statements can be executed without the fault showing up © The Mc. Graw-Hill Companies, 2005 Figure 14. 15

Structural Testing: Branch Coverage l Slide 14 B. 97 Running a set of test cases in which every branch is executed at least once (as well as all statements) 4 This solves the problem on the previous slide 4 Again, a CASE tool is needed © The Mc. Graw-Hill Companies, 2005

Structural Testing: Path Coverage Slide 14 B. 98 l Running a set of test cases in which every path is executed at least once (as well as all statements) l Problem: 4 The number of paths may be very large l We want a weaker condition than all paths but that shows up more faults than branch coverage © The Mc. Graw-Hill Companies, 2005

Linear Code Sequences Slide 14 B. 99 l Identify the set of points L from which control flow may jump, plus entry and exit points l Restrict test cases to paths that begin and end with elements of L l This uncovers many faults without testing every path © The Mc. Graw-Hill Companies, 2005

All-Definition-Use-Path Coverage l Slide 14 B. 100 Each occurrence of variable, zz say, is labeled either as 4 The definition of a variable zz = 1 or read (zz) 4 or the use of variable y = zz + 3 or if (zz < 9) error. B () l Identify all paths from the definition of a variable to the use of that definition 4 This can be done by an automatic tool l A test case is set up for each such path © The Mc. Graw-Hill Companies, 2005

All-Definition-Use-Path Coverage (contd) Slide 14 B. 101 l Disadvantage: 4 Upper bound on number of paths is 2 d, where d is the number of branches l In practice: 4 The actual number of paths is proportional to d l This is therefore a practical test case selection technique © The Mc. Graw-Hill Companies, 2005

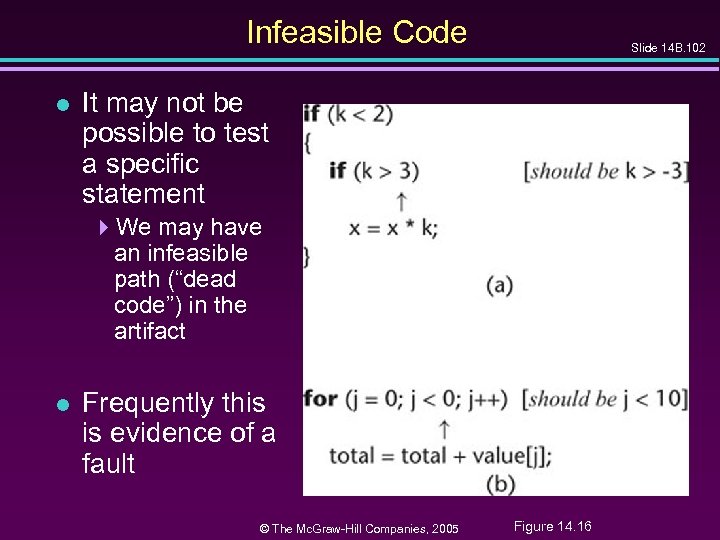

Infeasible Code l Slide 14 B. 102 It may not be possible to test a specific statement 4 We may have an infeasible path (“dead code”) in the artifact l Frequently this is evidence of a fault © The Mc. Graw-Hill Companies, 2005 Figure 14. 16

14. 13. 2 Complexity Metrics Slide 14 B. 103 l A quality assurance approach to glass-box testing l Artifact m 1 is more “complex” than artifact m 2 4 Intuitively, m 1 is more likely to have faults than artifact m 2 l If the complexity is unreasonably high, redesign and then reimplement that code artifact 4 This is cheaper and faster than trying to debug a faultprone code artifact © The Mc. Graw-Hill Companies, 2005

Lines of Code l Slide 14 B. 104 The simplest measure of complexity 4 Underlying assumption: There is a constant probability p that a line of code contains a fault l Example 4 The tester believes each line of code has a 2 percent chance of containing a fault. 4 If the artifact under test is 100 lines long, then it is expected to contain 2 faults l The number of faults is indeed related to the size of the product as a whole © The Mc. Graw-Hill Companies, 2005

Other Measures of Complexity l Slide 14 B. 105 Cyclomatic complexity M (Mc. Cabe) 4 Essentially the number of decisions (branches) in the artifact 4 Easy to compute 4 A surprisingly good measure of faults (but see next slide) l In one experiment, artifacts with M > 10 were shown to have statistically more errors © The Mc. Graw-Hill Companies, 2005

Problem with Complexity Metrics l Slide 14 B. 106 Complexity metrics, as especially cyclomatic complexity, have been strongly challenged on 4 Theoretical grounds 4 Experimental grounds, and 4 Their high correlation with LOC l Essentially we are measuring lines of code, not complexity © The Mc. Graw-Hill Companies, 2005

Code Walkthroughs and Inspections l Slide 14 B. 107 Code reviews lead to rapid and thorough fault detection 4 Up to 95 percent reduction in maintenance costs © The Mc. Graw-Hill Companies, 2005

14. 15 Comparison of Unit-Testing Techniques Slide 14 B. 108 l Experiments comparing 4 Black-box testing 4 Glass-box testing 4 Reviews l [Myers, 1978] 59 highly experienced programmers 4 All three methods were equally effective in finding faults 4 Code inspections were less cost-effective l [Hwang, 1981] 4 All three methods were equally effective © The Mc. Graw-Hill Companies, 2005

![Comparison of Unit-Testing Techniques (contd) Slide 14 B. 109 l [Basili and Selby, 1987] Comparison of Unit-Testing Techniques (contd) Slide 14 B. 109 l [Basili and Selby, 1987]](https://present5.com/presentation/a2ceb450f59f709e945eb3bd5ba492ea/image-33.jpg)

Comparison of Unit-Testing Techniques (contd) Slide 14 B. 109 l [Basili and Selby, 1987] 42 advanced students in two groups, 32 professional programmers l Advanced students, group 1 4 No significant difference between the three methods l Advanced students, group 2 4 Code reading and black-box testing were equally good 4 Both outperformed glass-box testing l Professional programmers 4 Code reading detected more faults 4 Code reading had a faster fault detection rate © The Mc. Graw-Hill Companies, 2005

Comparison of Unit-Testing Techniques (contd) Slide 14 B. 110 l Conclusion 4 Code inspection is at least as successful at detecting faults as glass-box and black-box testing © The Mc. Graw-Hill Companies, 2005

Cleanroom Slide 14 B. 111 l A different approach to software development l Incorporates 4 An incremental process model 4 Formal techniques 4 Reviews © The Mc. Graw-Hill Companies, 2005

Cleanroom (contd) Slide 14 B. 112 l Prototype automated documentation system for the U. S. Naval Underwater Systems Center l 1820 lines of Fox. BASE 418 faults were detected by “functional verification” 4 Informal proofs were used 419 faults were detected in walkthroughs before compilation 4 There were NO compilation errors 4 There were NO execution-time failures © The Mc. Graw-Hill Companies, 2005

Cleanroom (contd) l Testing fault rate counting procedures differ: l Slide 14 B. 113 Usual paradigms: 4 Count faults after informal testing is complete (once SQA starts) l Cleanroom 4 Count faults after inspections are complete (once compilation starts) © The Mc. Graw-Hill Companies, 2005

Report on 17 Cleanroom Products l Slide 14 B. 114 Operating system 4350, 000 LOC 4 Developed in only 18 months 4 By a team of 70 4 The testing fault rate was only 1. 0 faults per KLOC l Various products totaling 1 million LOC 4 Weighted average testing fault rate: 2. 3 faults per KLOC l “[R]emarkable quality achievement” © The Mc. Graw-Hill Companies, 2005

Potential Problems When Testing Objects Slide 14 B. 115 l We must inspect classes and objects l We can run test cases on objects (but not on classes) © The Mc. Graw-Hill Companies, 2005

Potential Problems When Testing Obj. (contd) Slide 14 B. 116 l A typical classical module: 4 About 50 executable statements 4 Give the input arguments, check the output arguments l A typical object: 4 About 30 methods, some with only 2 or 3 statements 4 A method often does not return a value to the caller — it changes state instead 4 It may not be possible to check the state because of information hiding 4 Example: Method determine. Balance — we need to know account. Balance before, after © The Mc. Graw-Hill Companies, 2005

Potential Problems When Testing Obj. (contd) Slide 14 B. 117 l We need additional methods to return values of all state variables 4 They must be part of the test plan 4 Conditional compilation may have to be used l An inherited method may still have to be tested (see next four slides) © The Mc. Graw-Hill Companies, 2005

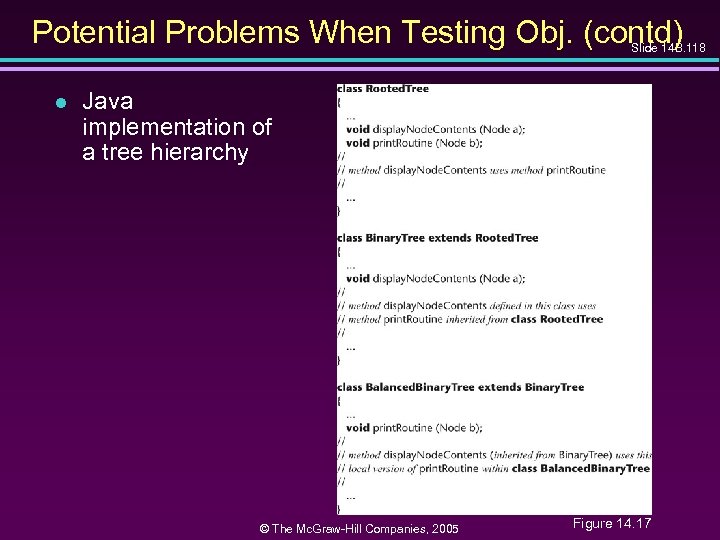

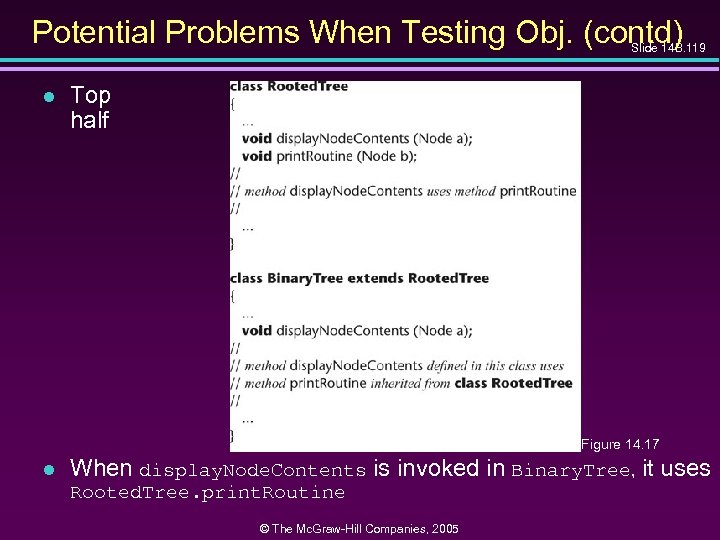

Potential Problems When Testing Obj. (contd) Slide 14 B. 118 l Java implementation of a tree hierarchy © The Mc. Graw-Hill Companies, 2005 Figure 14. 17

Potential Problems When Testing Obj. (contd) Slide 14 B. 119 l Top half Figure 14. 17 l When display. Node. Contents is invoked in Binary. Tree, it uses Rooted. Tree. print. Routine © The Mc. Graw-Hill Companies, 2005

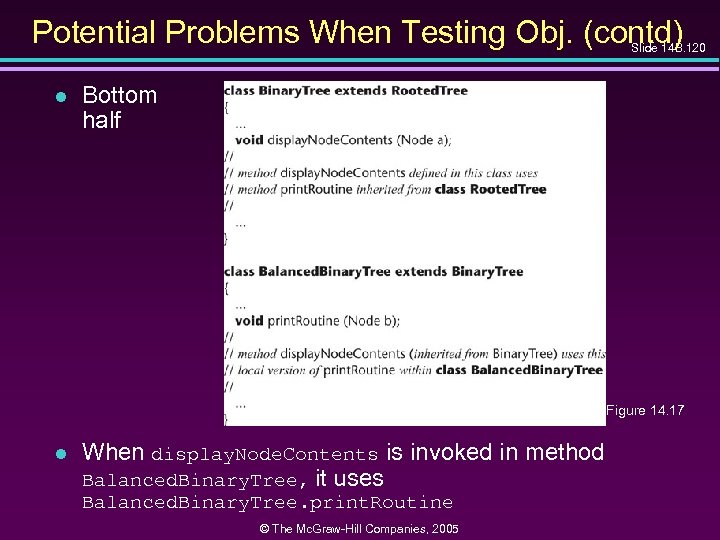

Potential Problems When Testing Obj. (contd) Slide 14 B. 120 l Bottom half Figure 14. 17 l When display. Node. Contents is invoked in method Balanced. Binary. Tree, it uses Balanced. Binary. Tree. print. Routine © The Mc. Graw-Hill Companies, 2005

Potential Problems When Testing Obj. (contd) Slide 14 B. 121 l Bad news 4 Binary. Tree. display. Node. Contents must be retested from scratch when reused in method Balanced. Binary. Tree 4 It invokes a different version of print. Routine l Worse news 4 For theoretical reasons, we need to test using totally different test cases © The Mc. Graw-Hill Companies, 2005

Potential Problems When Testing Obj. (contd) Slide 14 B. 122 l Making state variables visible 4 Minor issue l Retesting before reuse 4 Arises only when methods interact 4 We can determine when this retesting is needed l These are not reasons to abandon the objectoriented paradigm © The Mc. Graw-Hill Companies, 2005

14. 18 Management Aspects of Unit Testing Slide 14 B. 123 l We need to know when to stop testing l A number of different techniques can be used 4 Cost–benefit analysis 4 Risk analysis 4 Statistical techniques © The Mc. Graw-Hill Companies, 2005

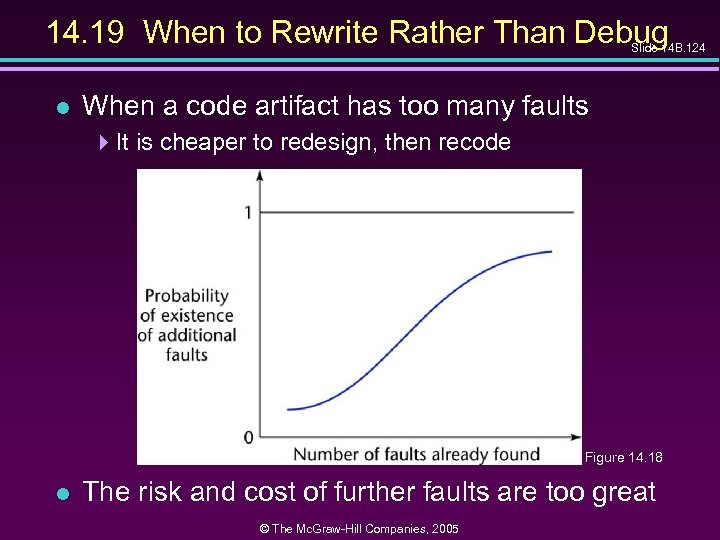

14. 19 When to Rewrite Rather Than Debug Slide 14 B. 124 l When a code artifact has too many faults 4 It is cheaper to redesign, then recode Figure 14. 18 l The risk and cost of further faults are too great © The Mc. Graw-Hill Companies, 2005

![Fault Distribution in Modules Is Not Uniform Slide 14 B. 125 l [Myers, 1979] Fault Distribution in Modules Is Not Uniform Slide 14 B. 125 l [Myers, 1979]](https://present5.com/presentation/a2ceb450f59f709e945eb3bd5ba492ea/image-49.jpg)

Fault Distribution in Modules Is Not Uniform Slide 14 B. 125 l [Myers, 1979] 447% of the faults in OS/370 were in only 4% of the modules l [Endres, 1975] 4512 faults in 202 modules of DOS/VS (Release 28) 4112 of the modules had only one fault 4 There were modules with 14, 15, 19 and 28 faults, respectively 4 The latter three were the largest modules in the product, with over 3000 lines of DOS macro assembler language 4 The module with 14 faults was relatively small, and very unstable 4 A prime candidate for discarding, redesigning, recoding © The Mc. Graw-Hill Companies, 2005

When to Rewrite Rather Than Debug (contd) Slide 14 B. 126 l For every artifact, management must predetermine the maximum allowed number of faults during testing l If this number is reached 4 Discard 4 Redesign 4 Recode l The maximum number of faults allowed after delivery is ZERO © The Mc. Graw-Hill Companies, 2005

14. 20 Integration Testing Slide 14 B. 127 l The testing of each new code artifact when it is added to what has already been tested l Special issues can arise when testing graphical user interfaces — see next slide © The Mc. Graw-Hill Companies, 2005

Integration Testing of Graphical User Interfaces Slide 14 B. 128 l GUI test cases include 4 Mouse clicks, and 4 Key presses l These types of test cases cannot be stored in the usual way 4 We need special CASE tools l Examples: 4 QAPartner 4 XRunner © The Mc. Graw-Hill Companies, 2005

14. 21 Product Testing l Slide 14 B. 129 Product testing for COTS software 4 Alpha, beta testing l Product testing for custom software 4 The SQA group must ensure that the product passes the acceptance test 4 Failing an acceptance test has bad consequences for the development organization © The Mc. Graw-Hill Companies, 2005

Product Testing for Custom Software l The SQA team must try to approximate the acceptance test 4 Black box test cases for the product as a whole 4 Robustness of product as a whole » Stress testing (under peak load) » Volume testing (e. g. , can it handle large input files? ) 4 All constraints must be checked 4 All documentation must be » Checked for correctness » Checked for conformity with standards » Verified against the current version of the product © The Mc. Graw-Hill Companies, 2005 Slide 14 B. 130

Product Testing for Custom Software (contd) Slide 14 B. 131 l The product (code plus documentation) is now handed over to the client organization for acceptance testing © The Mc. Graw-Hill Companies, 2005

14. 22 Acceptance Testing Slide 14 B. 132 l The client determines whether the product satisfies its specifications l Acceptance testing is performed by 4 The client organization, or 4 The SQA team in the presence of client representatives, or 4 An independent SQA team hired by the client © The Mc. Graw-Hill Companies, 2005

Acceptance Testing (contd) l Slide 14 B. 133 The four major components of acceptance testing are 4 Correctness 4 Robustness 4 Performance 4 Documentation l These are precisely what was tested by the developer during product testing © The Mc. Graw-Hill Companies, 2005

Acceptance Testing (contd) l Slide 14 B. 134 The key difference between product testing and acceptance testing is 4 Acceptance testing is performed on actual data 4 Product testing is preformed on test data, which can never be real, by definition © The Mc. Graw-Hill Companies, 2005

14. 23 The Test Workflow: The Osbert Oglesby Case Study Slide 14 B. 135 l The C++ and Java implementations were tested against 4 The black-box test cases of Figures 14. 13 and 14. 14, and 4 The glass-box test cases of Problems 14. 30 through 14. 34 © The Mc. Graw-Hill Companies, 2005

14. 24 CASE Tools for Implementation Slide 14 B. 136 l CASE tools for implementation of code artifacts were described in Chapter 5 l CASE tools for integration include 4 Version-control tools, configuration-control tools, and build tools 4 Examples: » rcs, sccs, PCVS, Source. Safe © The Mc. Graw-Hill Companies, 2005

14. 24 CASE Tools for Implementation l Configuration-control tools 4 Commercial » PCVS, Source. Safe 4 Open source » CVS © The Mc. Graw-Hill Companies, 2005 Slide 14 B. 137

14. 24. 1 CASE Tools for the Complete Software Process 14 B. 138 Slide l A large organization needs an environment l A medium-sized organization can probably manage with a workbench l A small organization can usually manage with just tools © The Mc. Graw-Hill Companies, 2005

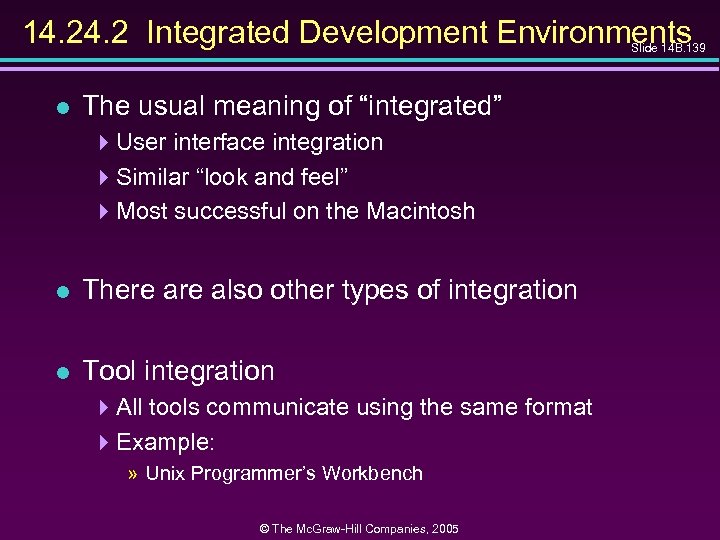

14. 2 Integrated Development Environments Slide 14 B. 139 l The usual meaning of “integrated” 4 User interface integration 4 Similar “look and feel” 4 Most successful on the Macintosh l There also other types of integration l Tool integration 4 All tools communicate using the same format 4 Example: » Unix Programmer’s Workbench © The Mc. Graw-Hill Companies, 2005

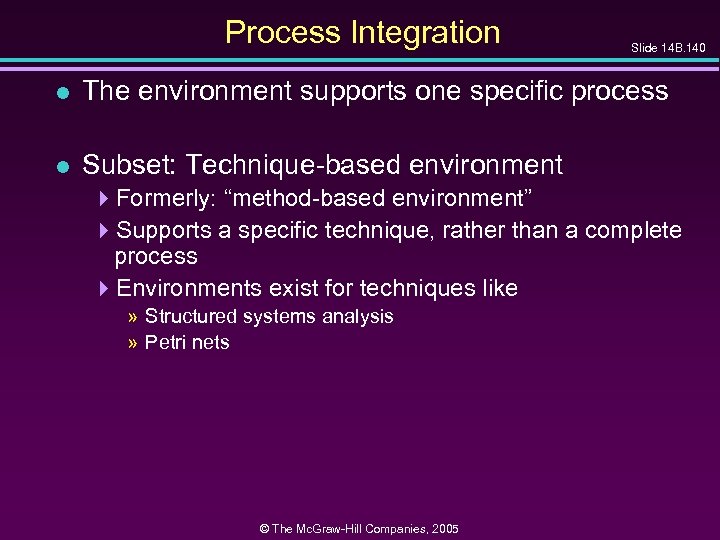

Process Integration Slide 14 B. 140 l The environment supports one specific process l Subset: Technique-based environment 4 Formerly: “method-based environment” 4 Supports a specific technique, rather than a complete process 4 Environments exist for techniques like » Structured systems analysis » Petri nets © The Mc. Graw-Hill Companies, 2005

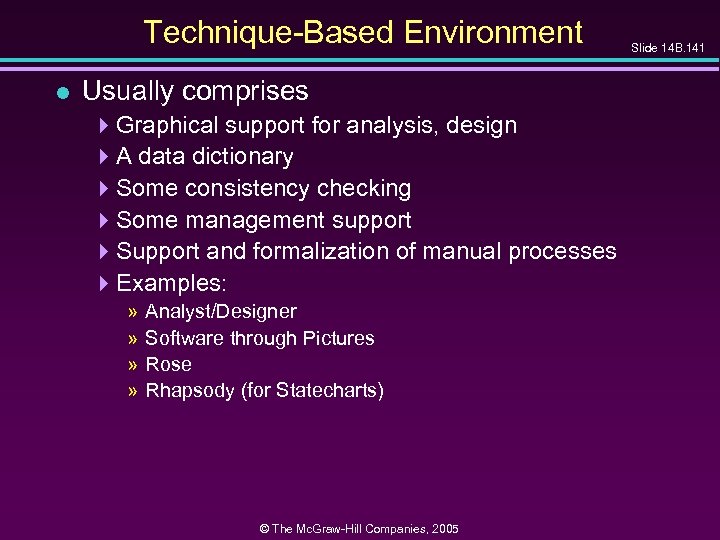

Technique-Based Environment l Usually comprises 4 Graphical support for analysis, design 4 A data dictionary 4 Some consistency checking 4 Some management support 4 Support and formalization of manual processes 4 Examples: » » Analyst/Designer Software through Pictures Rose Rhapsody (for Statecharts) © The Mc. Graw-Hill Companies, 2005 Slide 14 B. 141

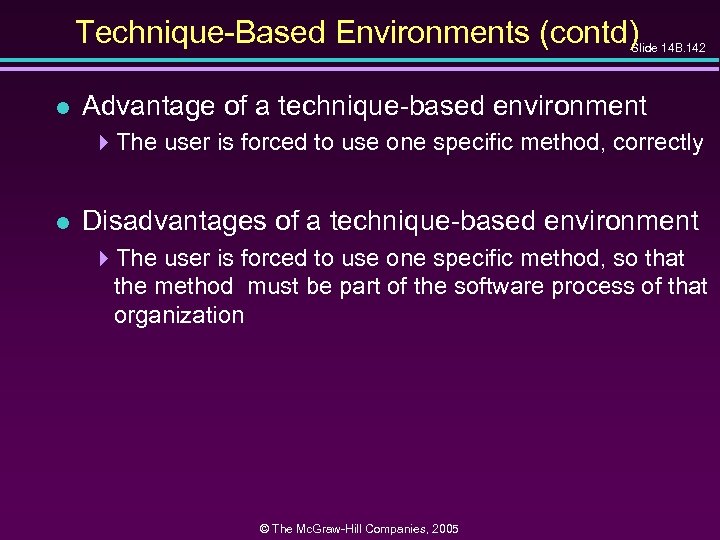

Technique-Based Environments (contd) Slide 14 B. 142 l Advantage of a technique-based environment 4 The user is forced to use one specific method, correctly l Disadvantages of a technique-based environment 4 The user is forced to use one specific method, so that the method must be part of the software process of that organization © The Mc. Graw-Hill Companies, 2005

14. 24. 3 Environments for Business Application Slide 14 B. 143 l The emphasis is on ease of use, including 4 A user-friendly GUI generator, 4 Standard screens for input and output, and 4 A code generator » Detailed design is the lowest level of abstraction » The detailed design is the input to the code generator l Use of this “programming language” should lead to a rise in productivity l Example: 4 Oracle Development Suite © The Mc. Graw-Hill Companies, 2005

14. 24. 4 Public Tool Infrastructure l Slide 14 B. 144 PCTE—Portable common tool environment 4 Not an environment 4 An infrastructure for supporting CASE tools (similar to the way an operating system provides services for user products) 4 Adopted by ECMA (European Computer Manufacturers Association) l Example implementations: 4 IBM, Emeraude © The Mc. Graw-Hill Companies, 2005

14. 24. 5 Potential Problems with Environments Slide 14 B. 145 l No one environment is ideal for all organizations 4 Each has its strengths and its weaknesses l Warning 1 4 Choosing the wrong environment can be worse than no environment 4 Enforcing a wrong technique is counterproductive l Warning 2 4 Shun CASE environments below CMM level 3 4 We cannot automate a nonexistent process 4 However, a CASE tool or a CASE workbench is fine © The Mc. Graw-Hill Companies, 2005

14. 25 Metrics for the Implementation Workflow Slide 14 B. 146 l The five basic metrics, plus 4 Complexity metrics l Fault statistics are important 4 Number of test cases 4 Percentage of test cases that resulted in failure 4 Total number of faults, by types l The fault data are incorporated into checklists for code inspections © The Mc. Graw-Hill Companies, 2005

14. 25 Metrics for the Implementation Workflow Slide 14 B. 147 l The five basic metrics, plus 4 Complexity metrics l Fault statistics are important 4 Number of test cases 4 Percentage of test cases that resulted in failure 4 Total number of faults, by types l The fault data are incorporated into checklists for code inspections © The Mc. Graw-Hill Companies, 2005

14. 26 Challenges of the Implementation Workflow Slide 14 B. 148 l Management issues are paramount here 4 Appropriate CASE tools 4 Test case planning 4 Communicating changes to all personnel 4 Deciding when to stop testing © The Mc. Graw-Hill Companies, 2005

Challenges of the Implementation Workflow (contd) Slide 14 B. 149 l Code reuse needs to be built into the product from the very beginning 4 Reuse must be a client requirement 4 The software project management plan must incorporate reuse l Implementation is technically straightforward 4 The challenges are managerial in nature © The Mc. Graw-Hill Companies, 2005

Challenges of the Implementation Phase (contd) Slide 14 B. 150 l Make-or-break issues include: 4 Use of appropriate CASE tools 4 Test planning as soon as the client has signed off the specifications 4 Ensuring that changes are communicated to all relevant personnel 4 Deciding when to stop testing © The Mc. Graw-Hill Companies, 2005

a2ceb450f59f709e945eb3bd5ba492ea.ppt