70ce60a344033f1b8f9636014181737d.ppt

- Количество слайдов: 85

Slide 14. 1 Object-Oriented and Classical Software Engineering Fifth Edition, WCB/Mc. Graw-Hill, 2002 Stephen R. Schach srs@vuse. vanderbilt. edu © The Mc. Graw-Hill Companies, 2002

CHAPTER 14 IMPLEMENTATION PHASE © The Mc. Graw-Hill Companies, 2002 Slide 14. 2

Overview l l l l Choice of programming language Fourth generation languages Good programming practice Coding standards Module reuse Module test case selection Black-box module-testing techniques Glass-box module-testing techniques © The Mc. Graw-Hill Companies, 2002 Slide 14. 3

Overview (contd) l l l l l Slide 14. 4 Code walkthroughs and inspections Comparison of module-testing techniques Cleanroom Potential problems when testing objects Management aspects of module testing When to rewrite rather than debug a module CASE tools for the implementation phase Air Gourmet Case Study: Black-box test cases Challenges of the implementation phase © The Mc. Graw-Hill Companies, 2002

Implementation Phase l l Programming-in-the-many Choice of Programming Language – Language is usually specified in contract l But what if the contract specifies – The product is to be implemented in the “most suitable” programming language l What language should be chosen? © The Mc. Graw-Hill Companies, 2002 Slide 14. 5

Choice of Programming Language (contd) Slide 14. 6 l Example – QQQ Corporation has been writing COBOL programs for over 25 years – Over 200 software staff, all with COBOL expertise – What is “most suitable” programming language? l Obviously COBOL © The Mc. Graw-Hill Companies, 2002

Choice of Programming Language (contd) Slide 14. 7 l What happens when new language (C++, say) is introduced – – – New hires Retrain existing professionals Future products in C++ Maintain existing COBOL products Two classes of programmers » COBOL maintainers (despised) » C++ developers (paid more) – Need expensive software, and hardware to run it – 100 s of person-years of expertise with COBOL wasted © The Mc. Graw-Hill Companies, 2002

Choice of Programming Language (contd) Slide 14. 8 l Only possible conclusion – COBOL is the “most suitable” programming language l And yet, the “most suitable” language for the latest project may be C++ – COBOL is suitable for only DP applications l How to choose a programming language – Cost-benefit analysis – Compute costs, benefits of all relevant languages © The Mc. Graw-Hill Companies, 2002

Choice of Programming Language (contd) Slide 14. 9 l Which is the most appropriate object-oriented language? – C++ is (unfortunately) C-like – Java enforces the object-oriented paradigm – Training in the object-oriented paradigm is essential before adopting any object-oriented language l What about choosing a fourth generation language (4 GL)? © The Mc. Graw-Hill Companies, 2002

Fourth Generation Languages l First generation languages – Machine languages l Second generation languages – Assemblers l Third generation languages – High-level languages (COBOL, FORTRAN, C++) l Fourth generation languages (4 GLs) – One 3 GL statement is equivalent to 5– 10 assembler statements – Each 4 GL statement intended to be equivalent to 30 or even 50 assembler statements © The Mc. Graw-Hill Companies, 2002 Slide 14. 10

Fourth Generation Languages (contd) l It was hoped that 4 GLs would – Speed up application-building – Applications easy, quick to change » Reducing maintenance costs – Simplify debugging – Make languages user friendly » Leading to end-user programming l Achievable if 4 GL is a user friendly, very high-level language © The Mc. Graw-Hill Companies, 2002 Slide 14. 11

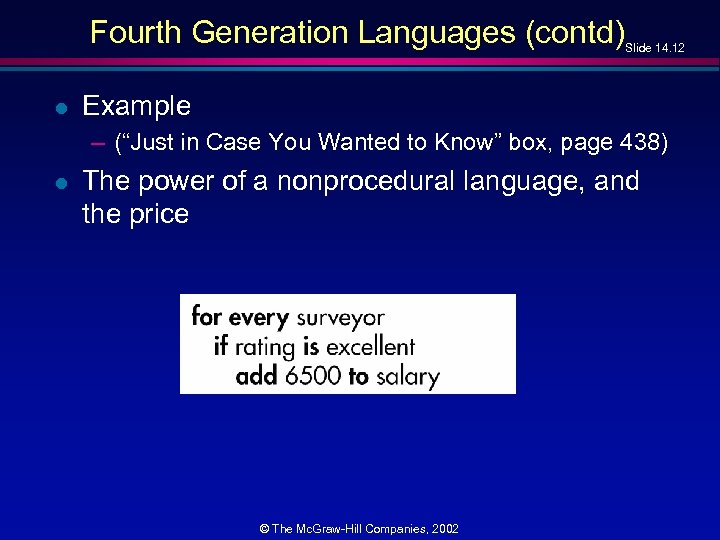

Fourth Generation Languages (contd) l Slide 14. 12 Example – (“Just in Case You Wanted to Know” box, page 438) l The power of a nonprocedural language, and the price © The Mc. Graw-Hill Companies, 2002

Productivity Increases with a 4 GL? l l Slide 14. 13 The picture is not uniformly rosy Problems with – Poor management techniques – Poor design methods l James Martin suggests use of – – l Prototyping Iterative design Computerized data management Computer-aided structuring Is he right? Does he (or anyone else) know? © The Mc. Graw-Hill Companies, 2002

Actual Experiences with 4 GLs l Playtex used ADF, obtained an 80 to 1 productivity increase over COBOL – However, Playtex then used COBOL for later applications l 4 GL productivity increases of 10 to 1 over COBOL have been reported – However, there are plenty of reports of bad experiences © The Mc. Graw-Hill Companies, 2002 Slide 14. 14

Actual Experiences with 4 GLs (contd) l Slide 14. 15 Attitudes of 43 Organizations to 4 GLs – – Use of 4 GL reduced users’ frustrations Quicker response from DP department 4 GLs slow and inefficient, on average Overall, 28 organizations using 4 GL for over 3 years felt that the benefits outweighed the costs © The Mc. Graw-Hill Companies, 2002

Fourth Generation Languages (contd) l Slide 14. 16 Market share – No one 4 GL dominates the software market – There are literally hundreds of 4 GLs – Dozens with sizable user groups l Reason – No one 4 GL has all the necessary features l Conclusion – Care has to be taken in selecting the appropriate 4 GL © The Mc. Graw-Hill Companies, 2002

Key Factors When Using a 4 GL l l l Slide 14. 17 Large sums for training Management techniques for 4 GL, not for COBOL Design methods must be appropriate, especially computer-aided design Interactive prototyping 4 GLs and complex products © The Mc. Graw-Hill Companies, 2002

Key Factors When Using a 4 GL (contd) Slide 14. 18 l Dangers of a 4 GL – Deceptive simplicity – End-user programming © The Mc. Graw-Hill Companies, 2002

Good Programming Practice l Slide 14. 19 Use of “consistent” and “meaningful” variable names – “Meaningful” to future maintenance programmer – “Consistent” to aid maintenance pyrogrammer © The Mc. Graw-Hill Companies, 2002

Good Programming Practice Example Slide 14. 20 l Module contains variables freq. Average, frequency. Maximum, min. Fr, frqncy. Totl l Maintenance programmer has to know if freq, frequency, frqncy all refer to the same thing – If so, use identical word, preferably frequency, perhaps freq or frqncy, not fr – If not, use different word (e. g. , rate) for different quantity l Can use frequency. Average, frequency. Myaximum, frequency. Minimum, frequency. Total l Can also use average. Frequency, maximum. Frequency, minimum. Frequency, total. Frequency l All four names must come from the same set © The Mc. Graw-Hill Companies, 2002

Good Programming Practice (contd) l Slide 14. 21 Issue of self-documenting code – Exceedingly rare l Key issue: Can module be understood easily and unambiguously by – SQA team – Maintenance programmers – All others who have to read the code © The Mc. Graw-Hill Companies, 2002

Good Programming Practice (contd) l Slide 14. 22 Example – – Variable x. Coordinate. Of. Position. Of. Robot. Arm Abbreviated to x. Coord Entire module deals with the movement of the robot arm But does the maintenance programmer know this? © The Mc. Graw-Hill Companies, 2002

Prologue Comments l Mandatory at top of every single module – Minimum information » » » » Module name Brief description of what the module does Programmer’s name Date module was coded Date module was approved, and by whom Module parameters Variable names, in alphabetical order, and uses Files accessed by this module Files updated by this module Module i/o Error handling capabilities Name of file of test data (for regression testing) List of modifications made, when, approved by whom Known faults, if any © The Mc. Graw-Hill Companies, 2002 Slide 14. 23

Other Comments l Slide 14. 24 Suggestion – Comments are essential whenever code is written in a non-obvious way, or makes use of some subtle aspect of the language l Nonsense! – Recode in a clearer way – We must never promote/excuse poor programming – However, comments can assist maintenance programmers l Code layout for increased readability – Use indentation – Better, use a pretty-printer – Use blank lines © The Mc. Graw-Hill Companies, 2002

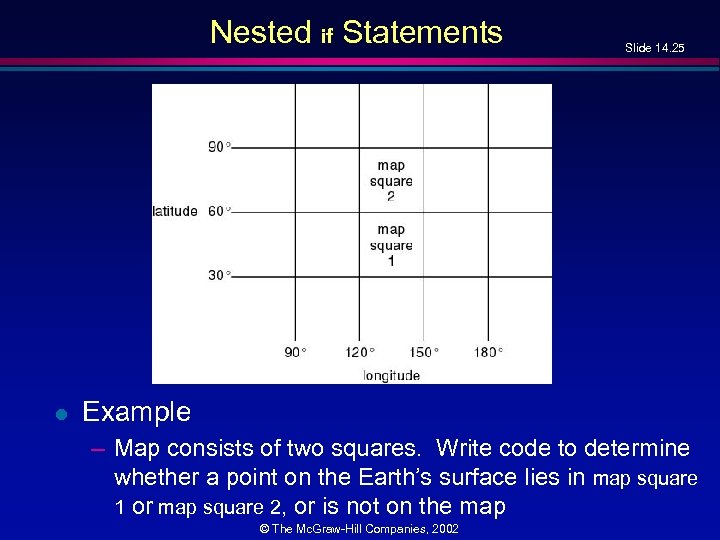

Nested if Statements l Slide 14. 25 Example – Map consists of two squares. Write code to determine whether a point on the Earth’s surface lies in map square 1 or map square 2, or is not on the map © The Mc. Graw-Hill Companies, 2002

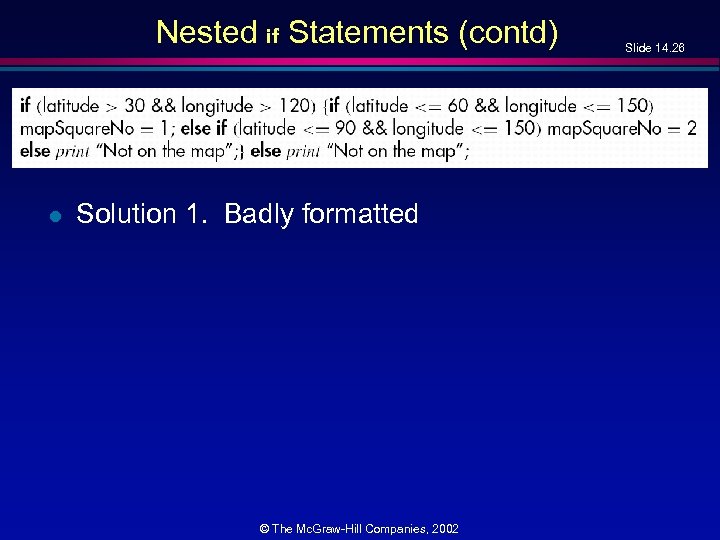

Nested if Statements (contd) l Solution 1. Badly formatted © The Mc. Graw-Hill Companies, 2002 Slide 14. 26

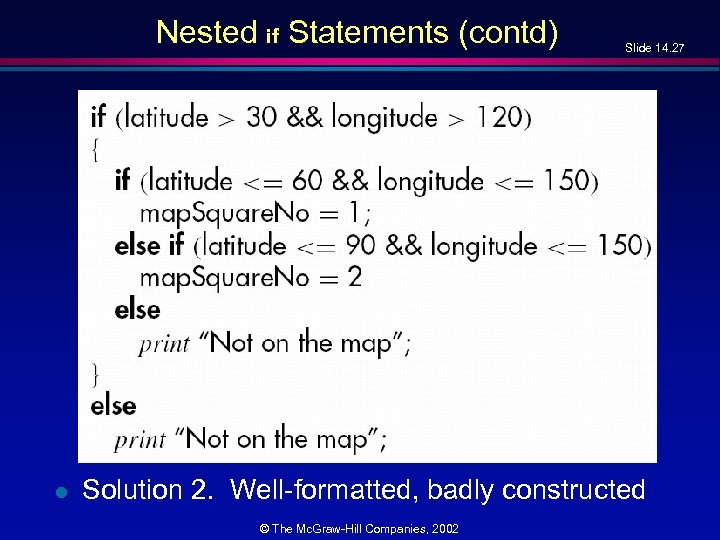

Nested if Statements (contd) l Slide 14. 27 Solution 2. Well-formatted, badly constructed © The Mc. Graw-Hill Companies, 2002

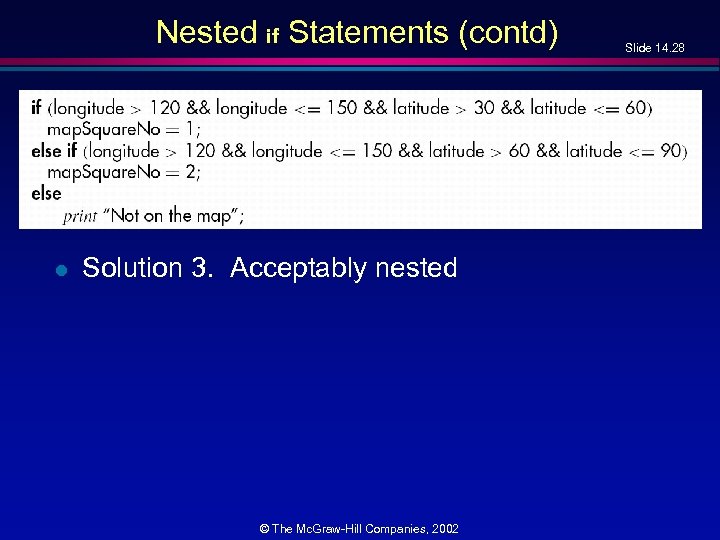

Nested if Statements (contd) l Solution 3. Acceptably nested © The Mc. Graw-Hill Companies, 2002 Slide 14. 28

Nested if Statements (contd) l l Slide 14. 29 Combination of if-if and if-else-if statements is usually difficult to read Simplify: The if-if combination if <condition 1> if <condition 2> is frequently equivalent to the single condition if <condition 1> && <condition 2> l Rule of thumb – if statements nested to a depth of greater than three should be avoided as poor programming practice © The Mc. Graw-Hill Companies, 2002

Programming Standards l l Slide 14. 30 Can be both a blessing and a curse Modules of coincidental cohesion arise from rules like – “Every module will consist of between 35 and 50 executable statements” l Better – “Programmers should consult their managers before constructing a module with fewer than 35 or more than 50 executable statements” © The Mc. Graw-Hill Companies, 2002

Remarks on Programming Standards l l l Slide 14. 31 No standard can ever be universally applicable Standards imposed from above will be ignored Standard must be checkable by machine © The Mc. Graw-Hill Companies, 2002

Remarks on Programming Standards (contd) Slide 14. 32 l Examples of good programming standards – “Nesting of if statements should not exceed a depth of 3, except with prior approval from the team leader” – “Modules should consist of between 35 and 50 statements, except with prior approval from the team leader” – “Use of gotos should be avoided. However, with prior approval from the team leader, a forward goto may be used for error handling” © The Mc. Graw-Hill Companies, 2002

Remarks on Programming Standards (contd) Slide 14. 33 l Aim of standards is to make maintenance easier – If it makes development difficult, then must be modified – Overly restrictive standards are counterproductive – Quality of software suffers © The Mc. Graw-Hill Companies, 2002

Software Quality Control l Slide 14. 34 After preliminary testing by the programmer, the module is handed over to the SQA group © The Mc. Graw-Hill Companies, 2002

Module Reuse l The most common form of reuse © The Mc. Graw-Hill Companies, 2002 Slide 14. 35

Module Test Case Selection l l Slide 14. 36 Worst way—random testing Need systematic way to construct test cases © The Mc. Graw-Hill Companies, 2002

Module Test Case Selection (contd) l l Slide 14. 37 Two extremes to testing 1. Test to specifications (also called black-box, data-driven, functional, or input/output driven testing) – Ignore code. Use specifications to select test cases l 2. Test to code (also called glass-box, logicdriven, structured, or path-oriented testing) – Ignore specifications. Use code to select test cases © The Mc. Graw-Hill Companies, 2002

Feasibility of Testing to Specifications l Slide 14. 38 Example – Specifications for data processing product include 5 types of commission and 7 types of discount – 35 test cases l Cannot say that commission and discount are computed in two entirely separate modules—the structure is irrelevant © The Mc. Graw-Hill Companies, 2002

Feasibility of Testing to Specifications l Slide 14. 39 Suppose specs include 20 factors, each taking on 4 values – 420 or 1. 1 ´ 1012 test cases – If each takes 30 seconds to run, running all test cases takes > 1 million years l Combinatorial explosion makes testing to specifications impossible © The Mc. Graw-Hill Companies, 2002

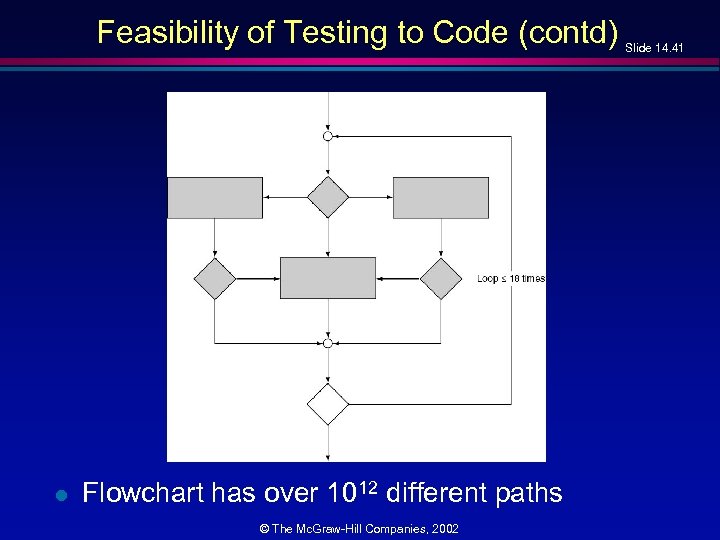

Feasibility of Testing to Code l Slide 14. 40 Each path through module must be executed at least once – Combinatorial explosion © The Mc. Graw-Hill Companies, 2002

Feasibility of Testing to Code (contd) l Flowchart has over 1012 different paths © The Mc. Graw-Hill Companies, 2002 Slide 14. 41

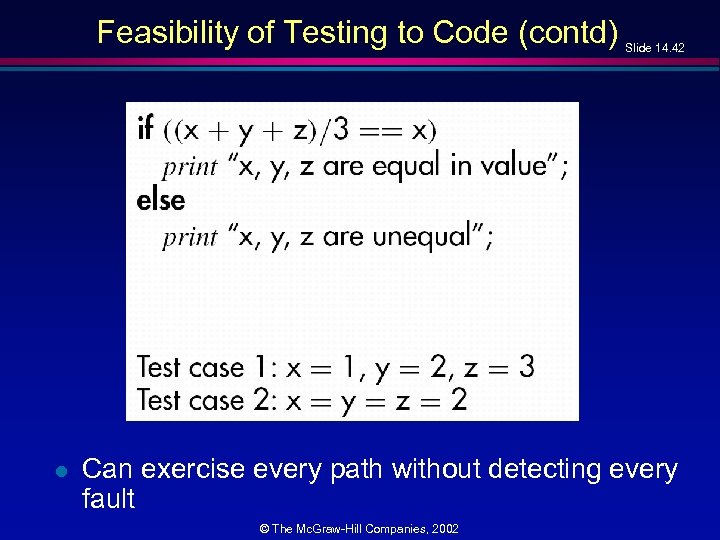

Feasibility of Testing to Code (contd) l Slide 14. 42 Can exercise every path without detecting every fault © The Mc. Graw-Hill Companies, 2002

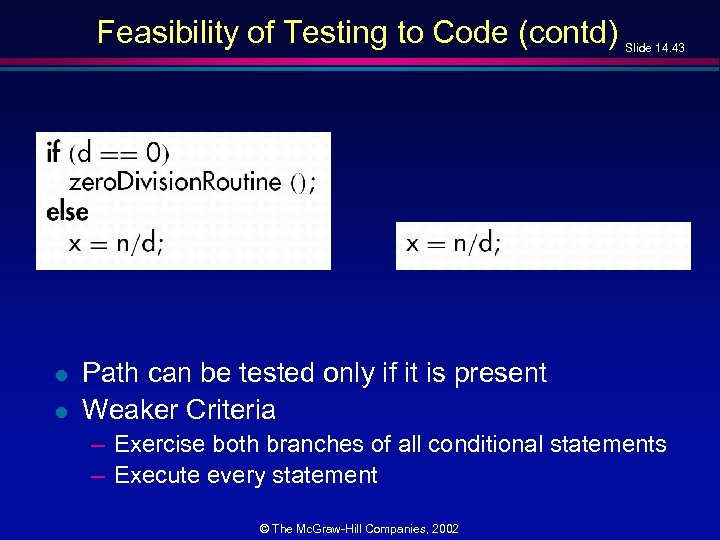

Feasibility of Testing to Code (contd) l l Slide 14. 43 Path can be tested only if it is present Weaker Criteria – Exercise both branches of all conditional statements – Execute every statement © The Mc. Graw-Hill Companies, 2002

Feasibility of Testing to Code (contd) l l l Slide 14. 44 Can exercise every path without detecting every fault Path can be tested only if it is present Weaker Criteria – Exercise both branches of all conditional statements – Execute every statement © The Mc. Graw-Hill Companies, 2002

Coping with the Combinatorial Explosion Slide 14. 45 l l l Neither testing to specifications nor testing to code is feasible The art of testing: Select a small, manageable set of test cases to – Maximize chances of detecting fault, while – Minimizing chances of wasting test case l Every test case must detect a previously undetected fault © The Mc. Graw-Hill Companies, 2002

Coping with the Combinatorial Explosion Slide 14. 46 l We need a method that will highlight as many faults as possible – First black-box test cases (testing to specifications) – Then glass-box methods (testing to code) © The Mc. Graw-Hill Companies, 2002

Black-Box Module Testing Methods l l Slide 14. 47 Equivalence Testing Example – Specifications for DBMS state that product must handle any number of records between 1 and 16, 383 (214– 1) – If system can handle 34 records and 14, 870 records, then probably will work fine for 8, 252 records l If system works for any one test case in range (1. . 16, 383), then it will probably work for any other test case in range – Range (1. . 16, 383) constitutes an equivalence class l Any one member is as good a test case as any other member of the class © The Mc. Graw-Hill Companies, 2002

Equivalence Testing (contd) l Slide 14. 48 Range (1. . 16, 383) defines three different equivalence classes: – Equivalence Class 1: Fewer than 1 record – Equivalence Class 2: Between 1 and 16, 383 records – Equivalence Class 3: More than 16, 383 records © The Mc. Graw-Hill Companies, 2002

Boundary Value Analysis l Slide 14. 49 Select test cases on or just to one side of the boundary of equivalence classes – This greatly increases the probability of detecting fault © The Mc. Graw-Hill Companies, 2002

Database Example l l Slide 14. 50 Test case 1: 0 records Member of equivalence class 1 (and adjacent to boundary value) Test case 2: 1 record Boundary value Test case 3: 2 records Adjacent to boundary value Test case 4: 723 records Member of equivalence class 2 © The Mc. Graw-Hill Companies, 2002

Boundary Value Analysis of Output Specs Slide 14. 51 l Example: In 2001, the minimum Social Security (OASDI) deduction from any one paycheck was $0. 00, and the maximum was $4, 984. 80 – Test cases must include input data which should result in deductions of exactly $0. 00 and exactly $4, 984. 80 – Also, test data that might result in deductions of less than $0. 00 or more than $4, 984. 80 © The Mc. Graw-Hill Companies, 2002

Overall Strategy l Slide 14. 52 Equivalence classes together with boundary value analysis to test both input specifications and output specifications – Small set of test data with potential of uncovering large number of faults © The Mc. Graw-Hill Companies, 2002

Glass-Box Module Testing Methods l Structural testing – – Statement coverage Branch coverage Linear code sequences All-definition-use path coverage © The Mc. Graw-Hill Companies, 2002 Slide 14. 53

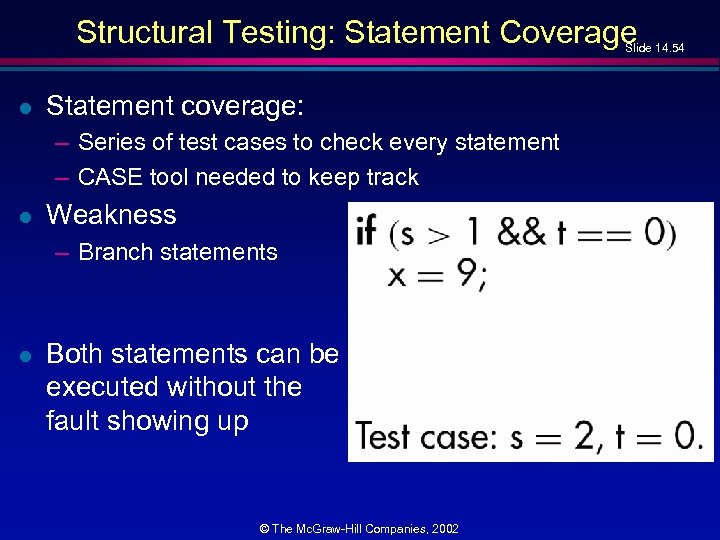

Structural Testing: Statement Coverage Slide 14. 54 l Statement coverage: – Series of test cases to check every statement – CASE tool needed to keep track l Weakness – Branch statements l Both statements can be executed without the fault showing up © The Mc. Graw-Hill Companies, 2002

Structural Testing: Branch Coverage l Series of tests to check all branches (solves above problem) – Again, a CASE tool is needed l Slide 14. 55 Structural testing: path coverage © The Mc. Graw-Hill Companies, 2002

Linear Code Sequences l Slide 14. 56 In a product with a loop, the number of paths is very large, and can be infinite – We want a weaker condition than all paths but that shows up more faults than branch coverage l Linear code sequences – Identify the set of points L from which control flow may jump, plus entry and exit points – Restrict test cases to paths that begin and end with elements of L – This uncovers many faults without testing every path © The Mc. Graw-Hill Companies, 2002

All-definition-use-path Coverage l Slide 14. 57 Each occurrence of variable, zz say, is labeled either as – The definition of a variable zz = 1 or read (zz) – or the use of variable y = zz + 3 or if (zz < 9) error. B () l Identify all paths from the definition of a variable to the use of that definition – This can be done by an automatic tool l A test case is set up for each such path © The Mc. Graw-Hill Companies, 2002

All-definition-use-path Coverage (contd) Slide 14. 58 l Disadvantage: – Upper bound on number of paths is 2 d, where d is the number of branches l In practice – The actual number of paths is proportional to d in real cases l This is therefore a practical test case selection technique © The Mc. Graw-Hill Companies, 2002

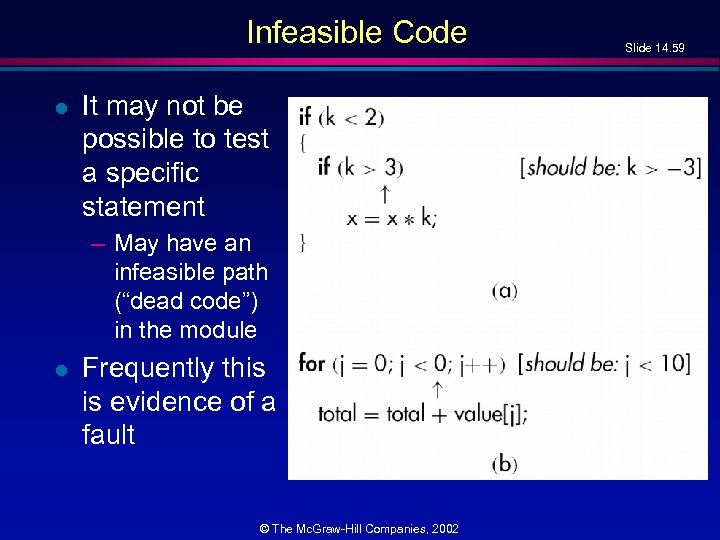

Infeasible Code l It may not be possible to test a specific statement – May have an infeasible path (“dead code”) in the module l Frequently this is evidence of a fault © The Mc. Graw-Hill Companies, 2002 Slide 14. 59

Measures of Complexity l Slide 14. 60 Quality assurance approach to glass-box testing – Module m 1 is more “complex” than module m 2 l Metric of software complexity – Highlights modules mostly likely to have faults l If complexity is unreasonably high, then redesign, reimplement – Cheaper and faster © The Mc. Graw-Hill Companies, 2002

Lines of Code l l Simplest measure of complexity Underlying assumption: – Constant probability p that a line of code contains a fault l Example – Tester believes line of code has 2% chance of containing a fault. – If module under test is 100 lines long, then it is expected to contain 2 faults l Number of faults is indeed related to the size of the product as a whole © The Mc. Graw-Hill Companies, 2002 Slide 14. 61

Other Measures of Complexity l Slide 14. 62 Cyclomatic complexity M (Mc. Cabe) – Essentially the number of decisions (branches) in the module – Easy to compute – A surprisingly good measure of faults (but see later) l Modules with M > 10 have statistically more errors (Walsh) © The Mc. Graw-Hill Companies, 2002

![Software Science Metrics l [Halstead] Used for fault prediction – Basic elements are the Software Science Metrics l [Halstead] Used for fault prediction – Basic elements are the](https://present5.com/presentation/70ce60a344033f1b8f9636014181737d/image-63.jpg)

Software Science Metrics l [Halstead] Used for fault prediction – Basic elements are the number of operators and operands in the module l l Widely challenged Example © The Mc. Graw-Hill Companies, 2002 Slide 14. 63

Problem with These Metrics l Slide 14. 64 Both Software Science, cyclomatic complexity: – Strong theoretical challenges – Strong experimental challenges – High correlation with LOC l l Thus we are measuring LOC, not complexity Apparent contradiction – LOC is a poor metric for predicting productivity l No contradiction — LOC is used here to predict fault rates, not productivity © The Mc. Graw-Hill Companies, 2002

Code Walkthroughs and Inspections l Rapid and thorough fault detection – Up to 95% reduction in maintenance costs [Crossman, 1982] © The Mc. Graw-Hill Companies, 2002 Slide 14. 65

Comparison: Module Testing Techniques Slide 14. 66 l Experiments comparing – Black-box testing – Glass-box testing – Reviews l (Myers, 1978) 59 highly experienced programmers – All three methods equally effective in finding faults – Code inspections less cost-effective l (Hwang, 1981) – All three methods equally effective © The Mc. Graw-Hill Companies, 2002

Comparison: Module Testing Techniques (contd) Slide 14. 67 l l Tests of 32 professional programmers, 42 advanced students in two groups (Basili and Selby, 1987) Professional programmers – Code reading detected more faults – Code reading had a faster fault detection rate l Advanced students, group 1 – No significant difference between the three methods l Advanced students, group 2 – Code reading and black-box testing were equally good – Both outperformed glass-box testing © The Mc. Graw-Hill Companies, 2002

Comparison: Module Testing Techniques (contd) Slide 14. 68 l Conclusion – Code inspection is at least as successful at detecting faults as glass-box and black-box testing © The Mc. Graw-Hill Companies, 2002

Cleanroom l l Different approach to software development Incorporates – Incremental process model – Formal techniques – Reviews © The Mc. Graw-Hill Companies, 2002 Slide 14. 69

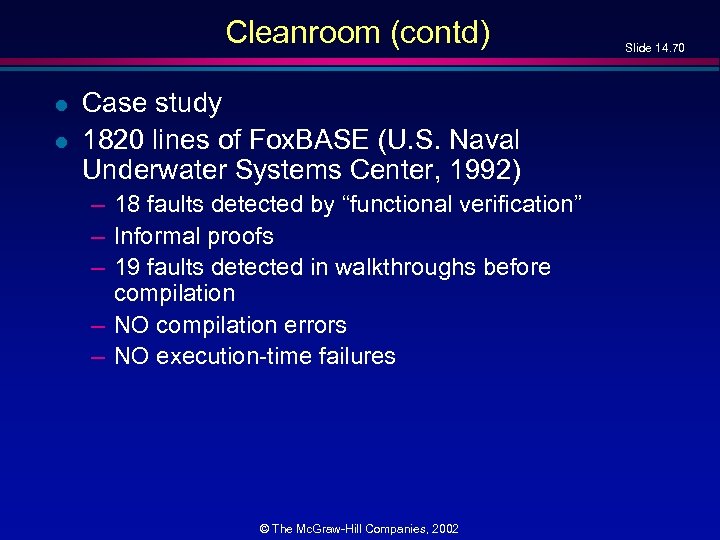

Cleanroom (contd) l l Case study 1820 lines of Fox. BASE (U. S. Naval Underwater Systems Center, 1992) – 18 faults detected by “functional verification” – Informal proofs – 19 faults detected in walkthroughs before compilation – NO compilation errors – NO execution-time failures © The Mc. Graw-Hill Companies, 2002 Slide 14. 70

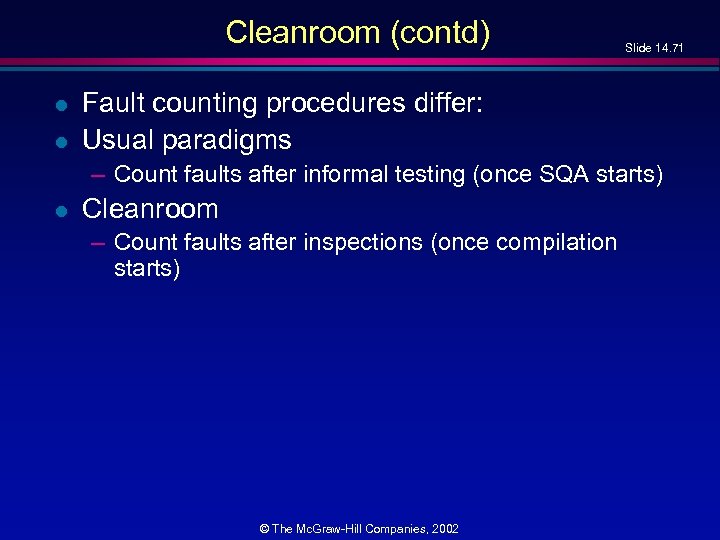

Cleanroom (contd) l l Slide 14. 71 Fault counting procedures differ: Usual paradigms – Count faults after informal testing (once SQA starts) l Cleanroom – Count faults after inspections (once compilation starts) © The Mc. Graw-Hill Companies, 2002

![Cleanroom (contd) l Report on 17 Cleanroom products [Linger, 1994] – – – 350, Cleanroom (contd) l Report on 17 Cleanroom products [Linger, 1994] – – – 350,](https://present5.com/presentation/70ce60a344033f1b8f9636014181737d/image-72.jpg)

Cleanroom (contd) l Report on 17 Cleanroom products [Linger, 1994] – – – 350, 000 line product, team of 70, 18 months 1. 0 faults per KLOC Total of 1 million lines of code Weighted average: 2. 3 faults per KLOC “[R]emarkable quality achievement” © The Mc. Graw-Hill Companies, 2002 Slide 14. 72

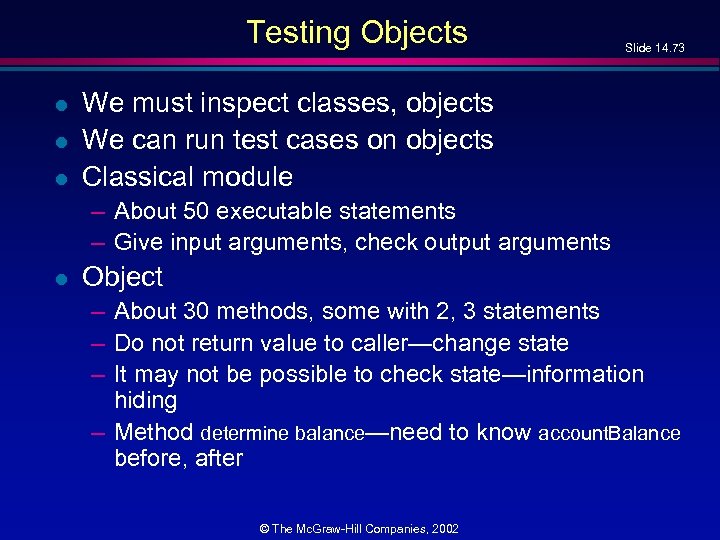

Testing Objects l l l Slide 14. 73 We must inspect classes, objects We can run test cases on objects Classical module – About 50 executable statements – Give input arguments, check output arguments l Object – About 30 methods, some with 2, 3 statements – Do not return value to caller—change state – It may not be possible to check state—information hiding – Method determine balance—need to know account. Balance before, after © The Mc. Graw-Hill Companies, 2002

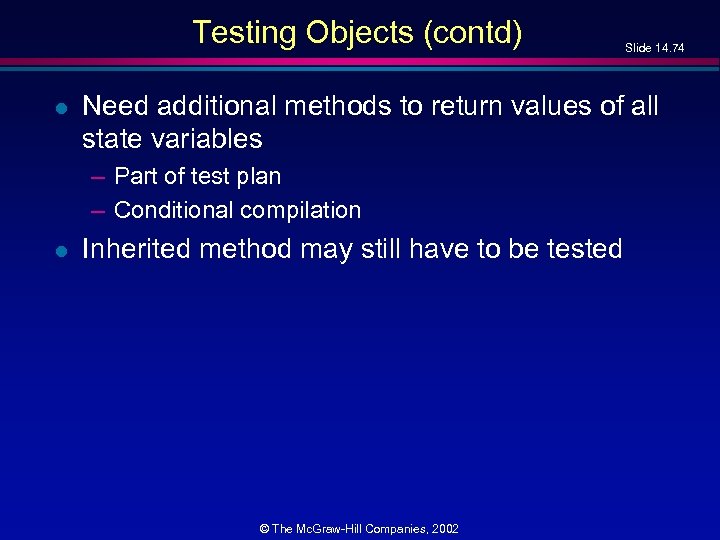

Testing Objects (contd) l Need additional methods to return values of all state variables – Part of test plan – Conditional compilation l Slide 14. 74 Inherited method may still have to be tested © The Mc. Graw-Hill Companies, 2002

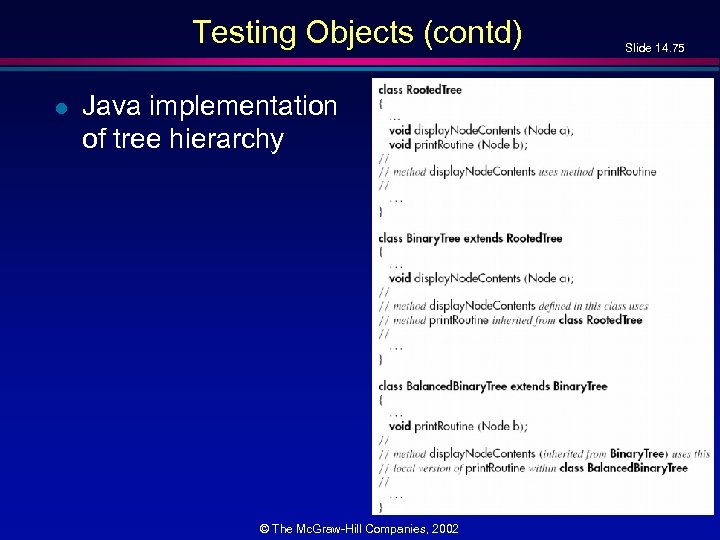

Testing Objects (contd) l Java implementation of tree hierarchy © The Mc. Graw-Hill Companies, 2002 Slide 14. 75

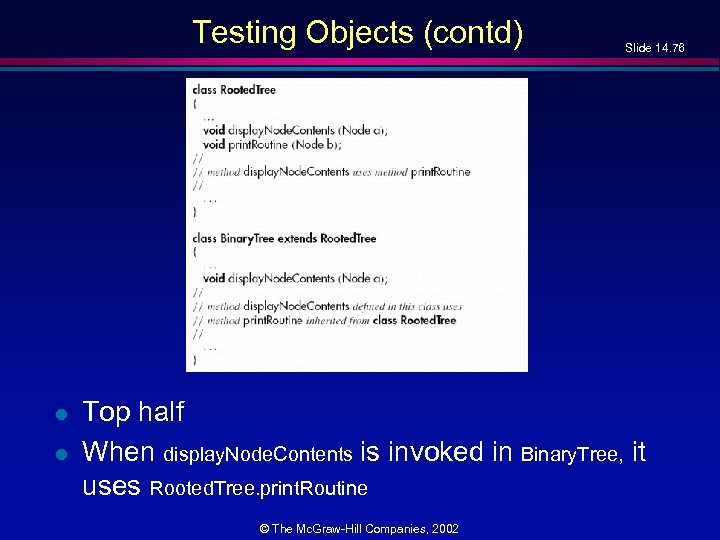

Testing Objects (contd) l l Slide 14. 76 Top half When display. Node. Contents is invoked in Binary. Tree, it uses Rooted. Tree. print. Routine © The Mc. Graw-Hill Companies, 2002

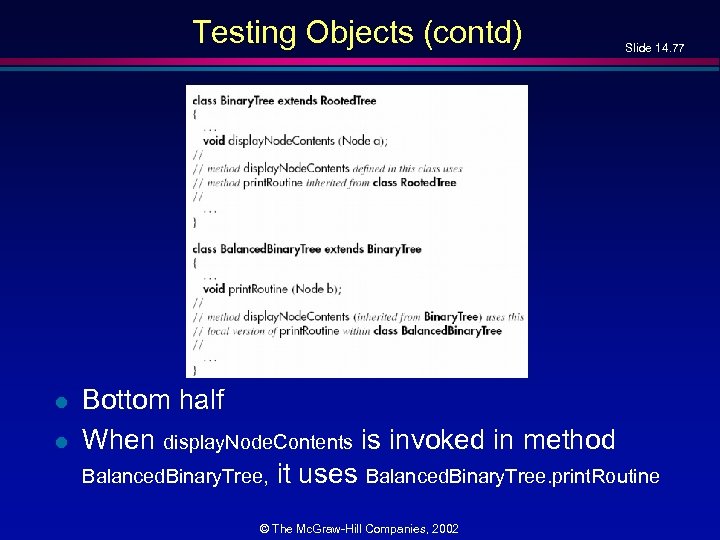

Testing Objects (contd) l l Slide 14. 77 Bottom half When display. Node. Contents is invoked in method Balanced. Binary. Tree, it uses Balanced. Binary. Tree. print. Routine © The Mc. Graw-Hill Companies, 2002

Testing Objects (contd) l Slide 14. 78 Bad news – Binary. Tree. display. Node. Contents must be retested from scratch when reused in method Balanced. Binary. Tree – Invokes totally new print. Routine l Worse news – For theoretical reasons, we need to test using totally different test cases © The Mc. Graw-Hill Companies, 2002

Testing Objects (contd) l l Slide 14. 79 Two testing problems: Making state variables visible – Minor issue l Retesting before reuse – Arises only when methods interact – We can determine when this retesting is needed [Harrold, Mc. Gregor, and Fitzpatrick, 1992] l Not reasons to abandon the paradigm © The Mc. Graw-Hill Companies, 2002

Module Testing: Management Implications Slide 14. 80 l We need to know when to stop testing – Cost–benefit analysis – Risk analysis – Statistical techniques © The Mc. Graw-Hill Companies, 2002

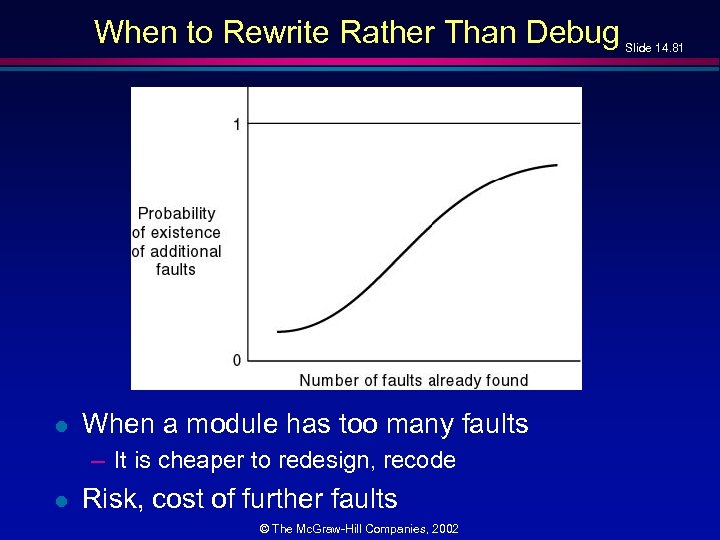

When to Rewrite Rather Than Debug l When a module has too many faults – It is cheaper to redesign, recode l Risk, cost of further faults © The Mc. Graw-Hill Companies, 2002 Slide 14. 81

![Fault Distribution In Modules Is Not Uniform Slide 14. 82 l [Myers, 1979] – Fault Distribution In Modules Is Not Uniform Slide 14. 82 l [Myers, 1979] –](https://present5.com/presentation/70ce60a344033f1b8f9636014181737d/image-82.jpg)

Fault Distribution In Modules Is Not Uniform Slide 14. 82 l [Myers, 1979] – 47% of the faults in OS/370 were in only 4% of the modules l [Endres, 1975] – 512 faults in 202 modules of DOS/VS (Release 28) – 112 of the modules had only one fault – There were modules with 14, 15, 19 and 28 faults, respectively – The latter three were the largest modules in the product, with over 3000 lines of DOS macro assembler language – The module with 14 faults was relatively small, and very unstable – A prime candidate for discarding, recoding © The Mc. Graw-Hill Companies, 2002

Fault Distribution In Modules Not Uniform (contd) Slide 14. 83 l l For every module, management must predetermine maximum allowed number of faults during testing If this number is reached – Discard – Redesign – Recode l Maximum number of faults allowed after delivery is ZERO © The Mc. Graw-Hill Companies, 2002

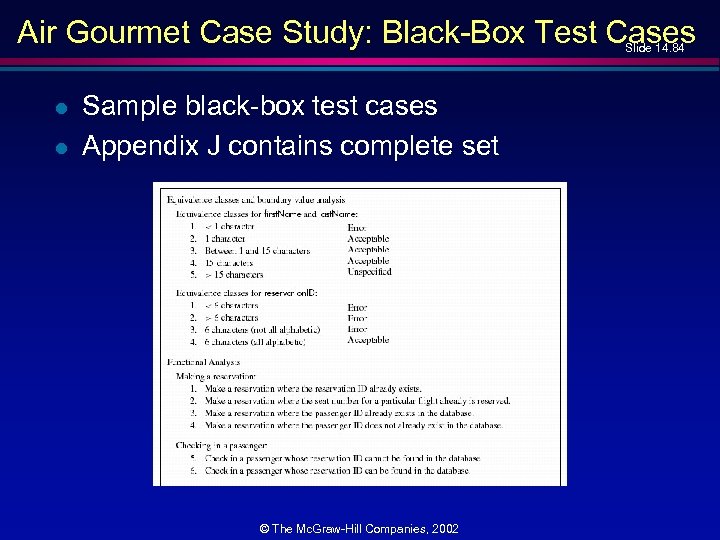

Air Gourmet Case Study: Black-Box Test Cases Slide 14. 84 l l Sample black-box test cases Appendix J contains complete set © The Mc. Graw-Hill Companies, 2002

Challenges of the Implementation Phase Slide 14. 85 l l l Module reuse needs to be built into the product from the very beginning Reuse must be a client requirement Software project management plan must incorporate reuse © The Mc. Graw-Hill Companies, 2002

70ce60a344033f1b8f9636014181737d.ppt