9a43835cffe3dd03f6c9731c82a1a4f0.ppt

- Количество слайдов: 100

Slide 11. 1 Object-Oriented and Classical Software Engineering Fifth Edition, WCB/Mc. Graw-Hill, 2002 Stephen R. Schach srs@vuse. vanderbilt. edu © The Mc. Graw-Hill Companies, 2002

CHAPTER 11 Slide 11. 2 SPECIFICATION PHASE © The Mc. Graw-Hill Companies, 2002

Overview l l l l The specification document Informal specifications Structured systems analysis Other semiformal techniques Entity-relationship modeling Finite state machines Petri nets Other formal techniques © The Mc. Graw-Hill Companies, 2002 Slide 11. 3

Overview (contd) l l l l Comparison of specification techniques Testing during the specification phase CASE tools for the specification phase Metrics for the specification phase Air Gourmet Case Study: structured systems analysis Air Gourmet Case Study: software project management plan Challenges of the specifications phase © The Mc. Graw-Hill Companies, 2002 Slide 11. 4

Specification Phase l Specification document must be – Informal enough for client – Formal enough for developers – Free of omissions, contradictions, ambiguities © The Mc. Graw-Hill Companies, 2002 Slide 11. 5

Specification Document l Constraints – – – Cost Time Parallel running Portability Reliability Rapid response time © The Mc. Graw-Hill Companies, 2002 Slide 11. 6

Specification Document (contd) l Slide 11. 7 Acceptance criteria – Vital to spell out series of tests – Product passes tests, deemed to satisfy specifications – Some are restatements of constraints © The Mc. Graw-Hill Companies, 2002

Solution Strategy l l General approach to building the product Find strategies without worrying about constraints Modify strategies in the light of constraints, if necessary Keep a written record of all discarded strategies, and why they were discarded – To protect the specification team – To prevent unwise new “solutions” during the maintenance phase © The Mc. Graw-Hill Companies, 2002 Slide 11. 8

Informal Specifications l Slide 11. 9 Example “If sales for current month are below target sales, then report is to be printed, unless difference between target sales and actual sales is less than half of difference between target sales and actual sales in previous month, or if difference between target sales and actual sales for the current month is under 5%” © The Mc. Graw-Hill Companies, 2002

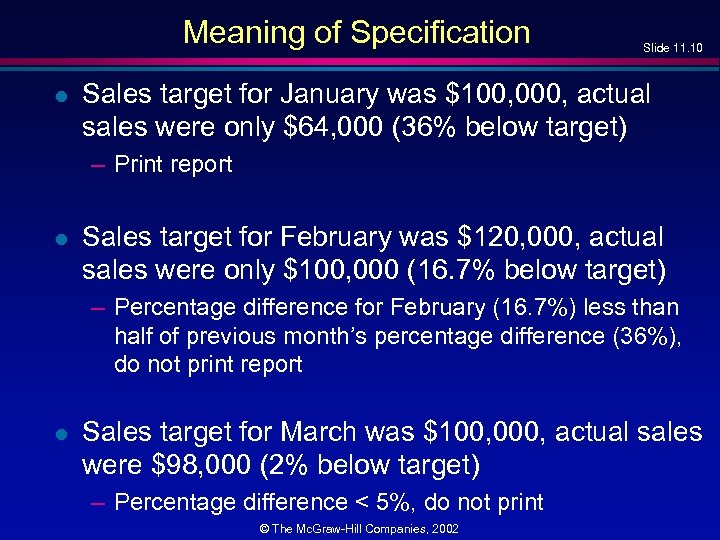

Meaning of Specification l Slide 11. 10 Sales target for January was $100, 000, actual sales were only $64, 000 (36% below target) – Print report l Sales target for February was $120, 000, actual sales were only $100, 000 (16. 7% below target) – Percentage difference for February (16. 7%) less than half of previous month’s percentage difference (36%), do not print report l Sales target for March was $100, 000, actual sales were $98, 000 (2% below target) – Percentage difference < 5%, do not print © The Mc. Graw-Hill Companies, 2002

![But Specifications Do Not Say This l Slide 11. 11 “[D]ifference between target sales But Specifications Do Not Say This l Slide 11. 11 “[D]ifference between target sales](https://present5.com/presentation/9a43835cffe3dd03f6c9731c82a1a4f0/image-11.jpg)

But Specifications Do Not Say This l Slide 11. 11 “[D]ifference between target sales and actual sales” – There is no mention of percentage difference l Difference in January was $36, 000, difference in February was $20, 000 – Not less than half of $36, 000, so report is printed l “[D]ifference … [of] 5%” – Again, no mention of percentage l l Ambiguity—should the last clause read “percentage difference … [of] 5%” or “difference … [of] $5, 000” or something else entirely? Style is poor © The Mc. Graw-Hill Companies, 2002

Informal Specifications (contd) l Slide 11. 12 Claim – This cannot arise with professional specifications writers l Refutation – Text Processing case study © The Mc. Graw-Hill Companies, 2002

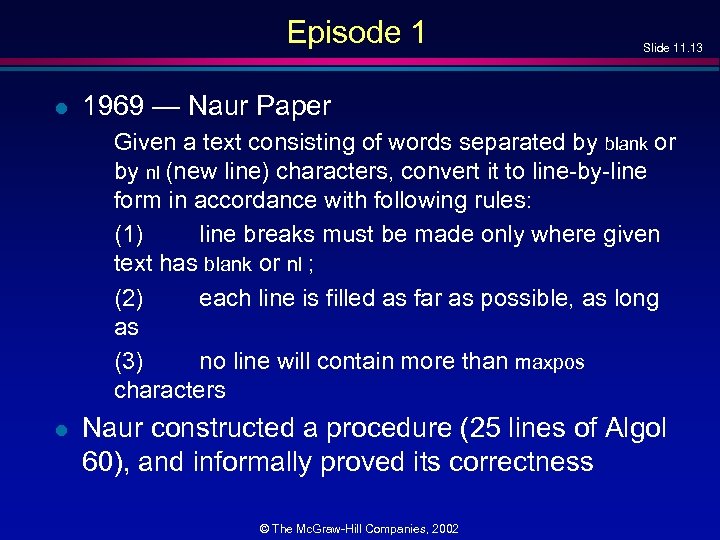

Episode 1 l Slide 11. 13 1969 — Naur Paper Given a text consisting of words separated by blank or by nl (new line) characters, convert it to line-by-line form in accordance with following rules: (1) line breaks must be made only where given text has blank or nl ; (2) each line is filled as far as possible, as long as (3) no line will contain more than maxpos characters l Naur constructed a procedure (25 lines of Algol 60), and informally proved its correctness © The Mc. Graw-Hill Companies, 2002

Episode 2 l Slide 11. 14 1970 — Reviewer in Computing Reviews – First word of first line is preceded by a blank unless the first word is exactly maxpos characters long © The Mc. Graw-Hill Companies, 2002

Episode 3 l Slide 11. 15 1971 — London found 3 more faults – Including: procedure does not terminate unless a word longer than maxpos characters is encountered © The Mc. Graw-Hill Companies, 2002

Episode 4 l Slide 11. 16 1975 — Goodenough and Gerhart found 3 further faults – Including—last word will not be output unless it is followed by blank or nl l Goodenough and Gerhart then produced new set of specifications, about four times longer than Naur’s © The Mc. Graw-Hill Companies, 2002

Case Study (contd) l l 1985 — Meyer detected 12 faults in Goodenough and Gerhart’s specifications – – – l Slide 11. 17 Were constructed with the greatest of care Were constructed to correct Naur’s specifications Went through two versions, carefully refereed Were written by experts in specifications With as much time as they needed For a product about 30 lines long What chance do we have of writing fault-free specifications for a real product? © The Mc. Graw-Hill Companies, 2002

Episode 5 l Slide 11. 18 1989 — Schach found fault in Meyer’s specifications – Item (2) of Naur’s original requirement (“each line is filled as far as possible”) is not satisfied © The Mc. Graw-Hill Companies, 2002

Informal Specifications l Slide 11. 19 Conclusion – Natural language is not a good way to specify product l Fact – Many organizations still use natural language, especially for commercial products l Reasons – – Uninformed management Undertrained computer professionals Management gives in to client pressure Management is unwilling to invest in training © The Mc. Graw-Hill Companies, 2002

Structured Systems Analysis l Slide 11. 20 Three popular graphical specification methods of ’ 70 s – De. Marco – Gane and Sarsen – Yourdon l l All equivalent All equally good Many U. S. corporations use them for commercial products Gane and Sarsen used for object-oriented design © The Mc. Graw-Hill Companies, 2002

Structured Systems Analysis Case Study Slide 11. 21 Sally’s Software Store buys software from various suppliers and sells it to the public. Popular software packages are kept in stock, but the rest must be ordered as required. Institutions and corporations are given credit facilities, as are some members of the public. Sally’s Software Store is doing well, with a monthly turnover of 300 packages at an average retail cost of $250 each. Despite her business success, Sally has been advised to computerize. Should she? l Better question – What sections? l Still better – How? Batch, or online? In-house or out-service? © The Mc. Graw-Hill Companies, 2002

Case Study (contd) l Slide 11. 22 Fundamental issue – What is Sally’s objective in computerizing her business? l Because she sells software? – She needs an in-house system with sound and light effects l Because she uses her business to launder “hot” money? – She needs a product that keeps five different sets of books, and has no audit trail l Assume: Computerization “in order to make more money” – Cost/benefit analysis for each section of business © The Mc. Graw-Hill Companies, 2002

Case Study (contd) l The danger of many standard approaches – First produce the solution, then find out what the problem is! l Gane and Sarsen’s method – Nine-step method – Stepwise refinement is used in many steps © The Mc. Graw-Hill Companies, 2002 Slide 11. 23

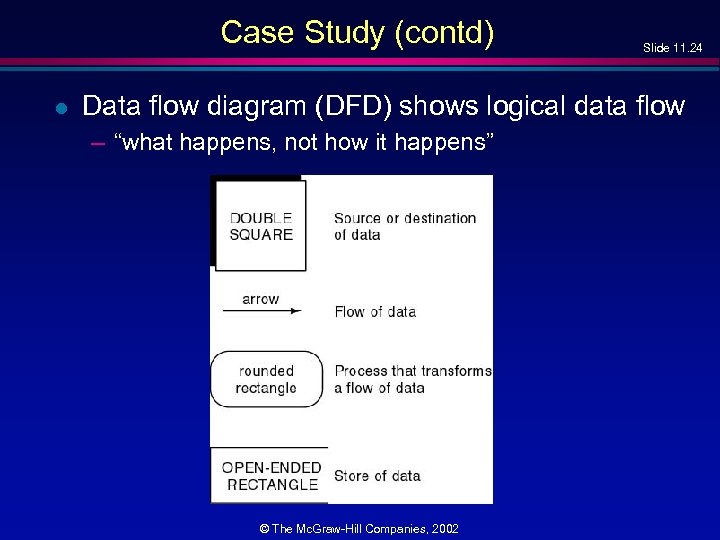

Case Study (contd) l Slide 11. 24 Data flow diagram (DFD) shows logical data flow – “what happens, not how it happens” © The Mc. Graw-Hill Companies, 2002

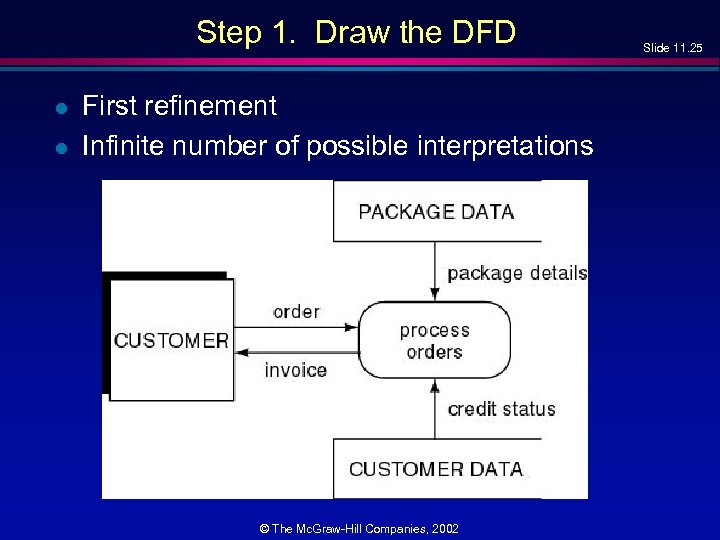

Step 1. Draw the DFD l l First refinement Infinite number of possible interpretations © The Mc. Graw-Hill Companies, 2002 Slide 11. 25

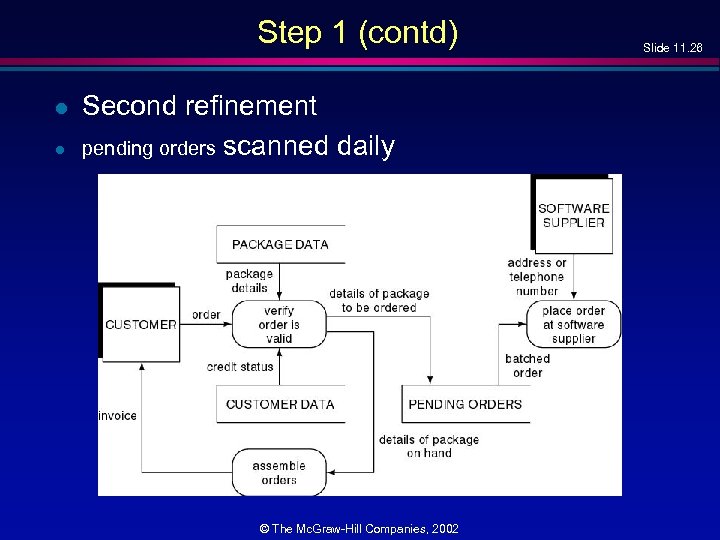

Step 1 (contd) l l Second refinement pending orders scanned daily © The Mc. Graw-Hill Companies, 2002 Slide 11. 26

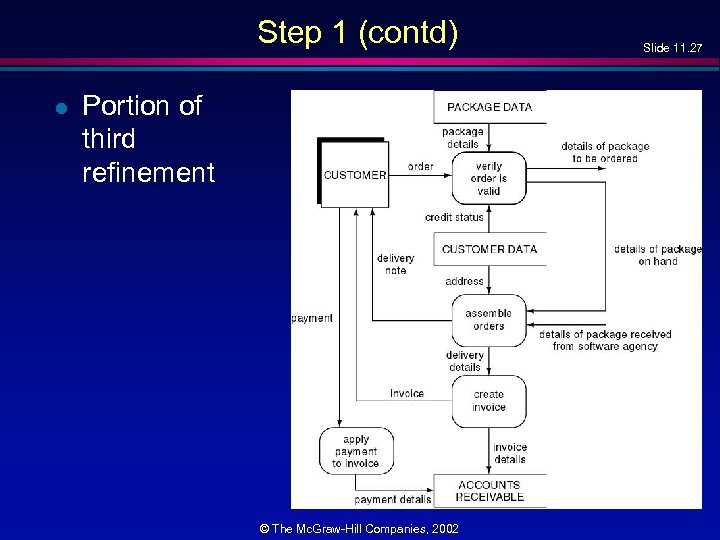

Step 1 (contd) l Portion of third refinement © The Mc. Graw-Hill Companies, 2002 Slide 11. 27

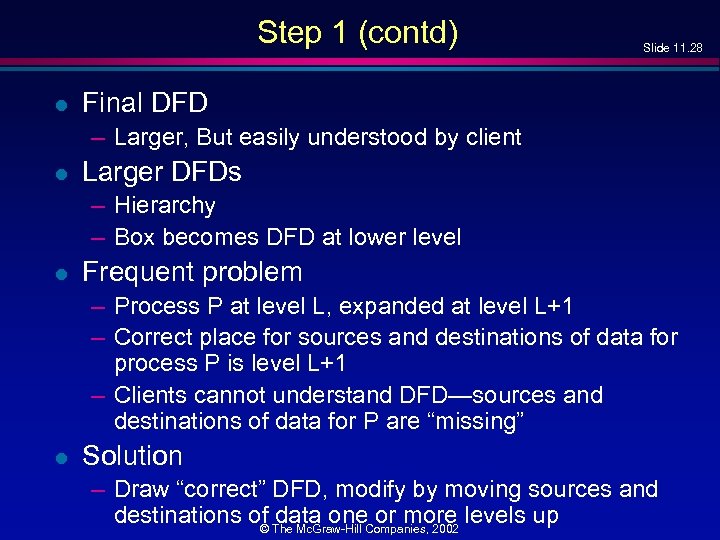

Step 1 (contd) l Slide 11. 28 Final DFD – Larger, But easily understood by client l Larger DFDs – Hierarchy – Box becomes DFD at lower level l Frequent problem – Process P at level L, expanded at level L+1 – Correct place for sources and destinations of data for process P is level L+1 – Clients cannot understand DFD—sources and destinations of data for P are “missing” l Solution – Draw “correct” DFD, modify by moving sources and destinations of data one or more levels up © The Mc. Graw-Hill Companies, 2002

Step 2. Decide What Parts to Computerize Slide 11. 29 l l Depends on how much client is prepared to spend Large volumes, tight controls – Batch l Small volumes, in-house microcomputer – Online l Cost/benefit analysis © The Mc. Graw-Hill Companies, 2002

Step 3. Refine Data Flows l l Data items for each data flow Refine each flow stepwise Refine further Need a data dictionary © The Mc. Graw-Hill Companies, 2002 Slide 11. 30

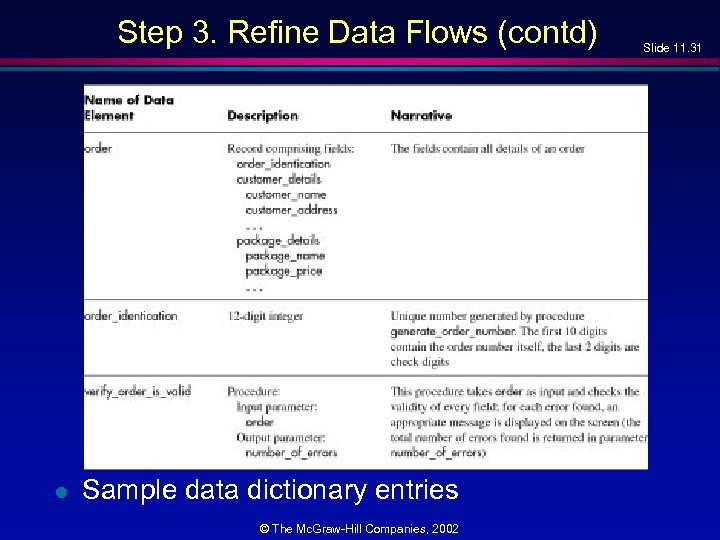

Step 3. Refine Data Flows (contd) l Sample data dictionary entries © The Mc. Graw-Hill Companies, 2002 Slide 11. 31

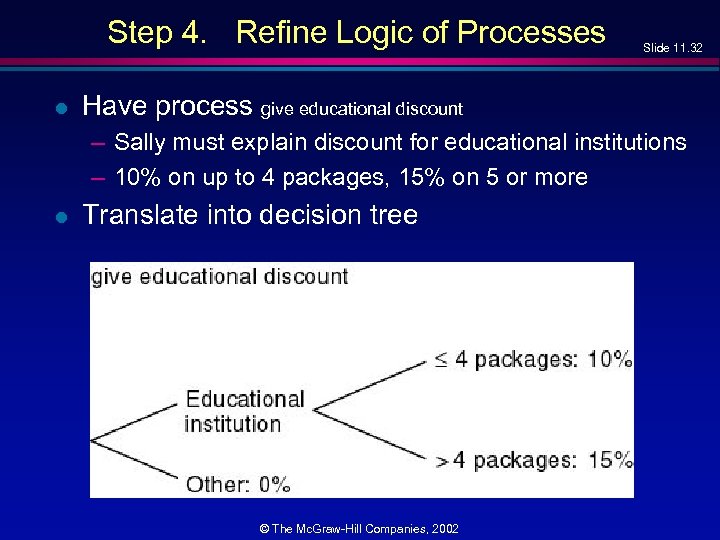

Step 4. Refine Logic of Processes l Slide 11. 32 Have process give educational discount – Sally must explain discount for educational institutions – 10% on up to 4 packages, 15% on 5 or more l Translate into decision tree © The Mc. Graw-Hill Companies, 2002

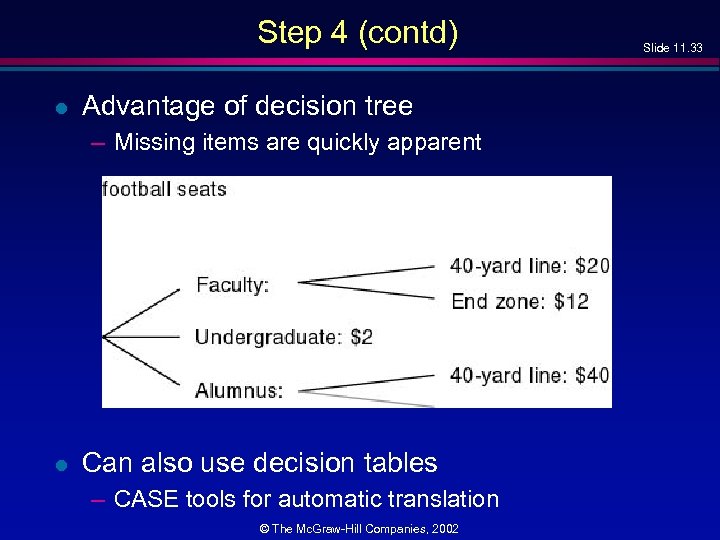

Step 4 (contd) l Advantage of decision tree – Missing items are quickly apparent l Can also use decision tables – CASE tools for automatic translation © The Mc. Graw-Hill Companies, 2002 Slide 11. 33

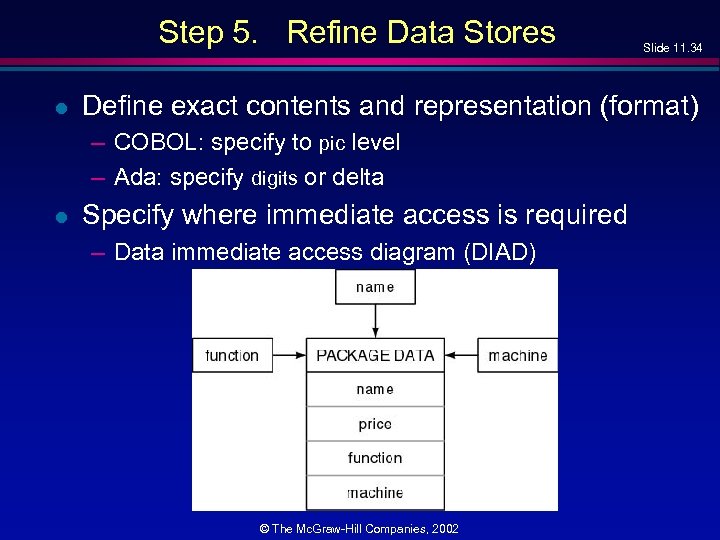

Step 5. Refine Data Stores l Define exact contents and representation (format) – COBOL: specify to pic level – Ada: specify digits or delta l Slide 11. 34 Specify where immediate access is required – Data immediate access diagram (DIAD) © The Mc. Graw-Hill Companies, 2002

Step 6. Define Physical Resources l For each file, specify – – – File name Organization (sequential, indexed, etc. ) Storage medium Blocking factor Records (to field level) © The Mc. Graw-Hill Companies, 2002 Slide 11. 35

Step 7. Determine Input/Output Specs l Slide 11. 36 Specify input forms, input screens, printed output © The Mc. Graw-Hill Companies, 2002

Step 8. Perform Sizing l Numerical data for Step 9 to determine hardware requirements – Volume of input (daily or hourly) – Size, frequency, deadline of each printed report – Size, number of records passing between CPU and mass storage – Size of each file © The Mc. Graw-Hill Companies, 2002 Slide 11. 37

Step 9. Hardware Requirements l l l DASD requirements Mass storage for back-up Input needs Output devices Is existing hardware adequate? If not, recommend buy/lease © The Mc. Graw-Hill Companies, 2002 Slide 11. 38

However l l l Slide 11. 39 Response times cannot be determined Number of I/O channels can only be guessed CPU size and timing can only be guessed Nevertheless, no other method provides these data for arbitrary products The method of Gane and Sarsen/De Marco/Yourdon has resulted in major improvements in the software industry © The Mc. Graw-Hill Companies, 2002

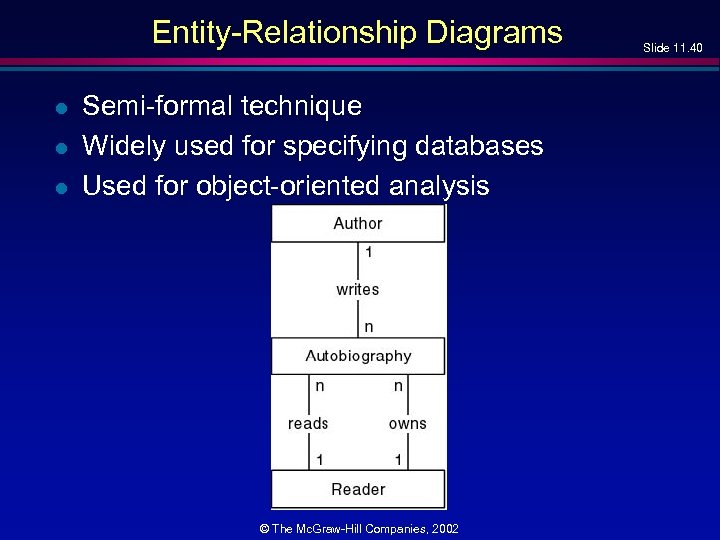

Entity-Relationship Diagrams l l l Semi-formal technique Widely used for specifying databases Used for object-oriented analysis © The Mc. Graw-Hill Companies, 2002 Slide 11. 40

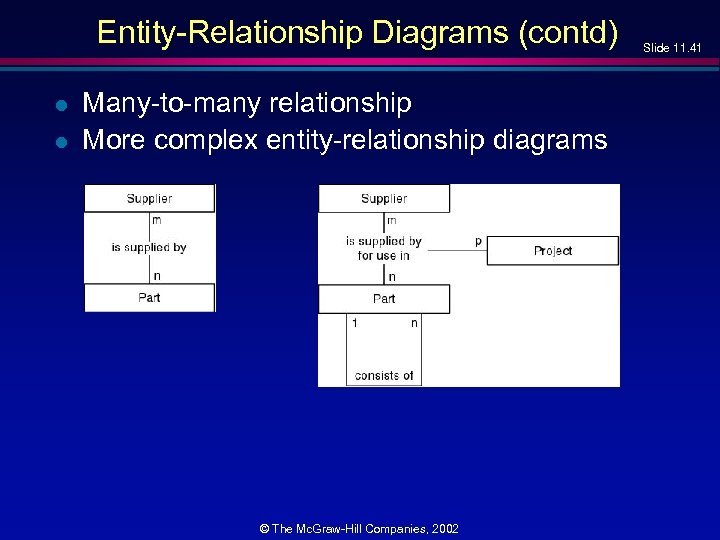

Entity-Relationship Diagrams (contd) l l Many-to-many relationship More complex entity-relationship diagrams © The Mc. Graw-Hill Companies, 2002 Slide 11. 41

Formality versus Informality l Informal method – English (or other natural language) l Semiformal methods – – l Gane & Sarsen/De. Marco/Yourdon Entity-Relationship Diagrams Jackson/Orr/Warnier, SADT, PSL/PSA, SREM, etc. Formal methods – – Finite State Machines Petri Nets Z ANNA, VDM, CSP, etc. © The Mc. Graw-Hill Companies, 2002 Slide 11. 42

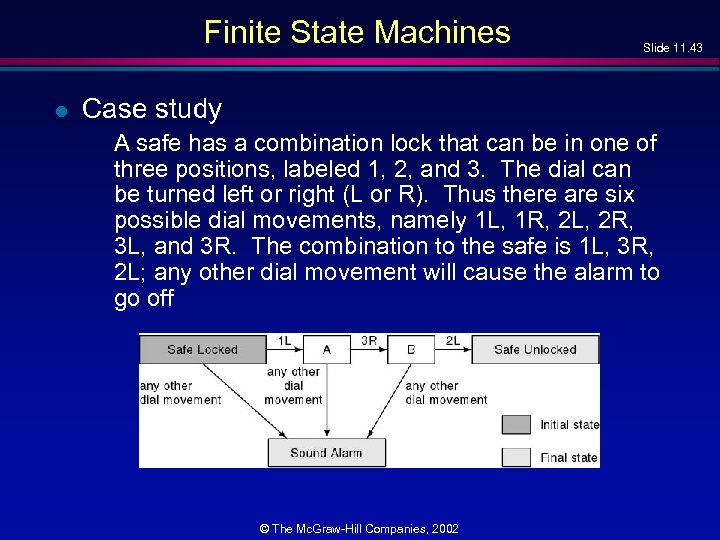

Finite State Machines l Slide 11. 43 Case study A safe has a combination lock that can be in one of three positions, labeled 1, 2, and 3. The dial can be turned left or right (L or R). Thus there are six possible dial movements, namely 1 L, 1 R, 2 L, 2 R, 3 L, and 3 R. The combination to the safe is 1 L, 3 R, 2 L; any other dial movement will cause the alarm to go off © The Mc. Graw-Hill Companies, 2002

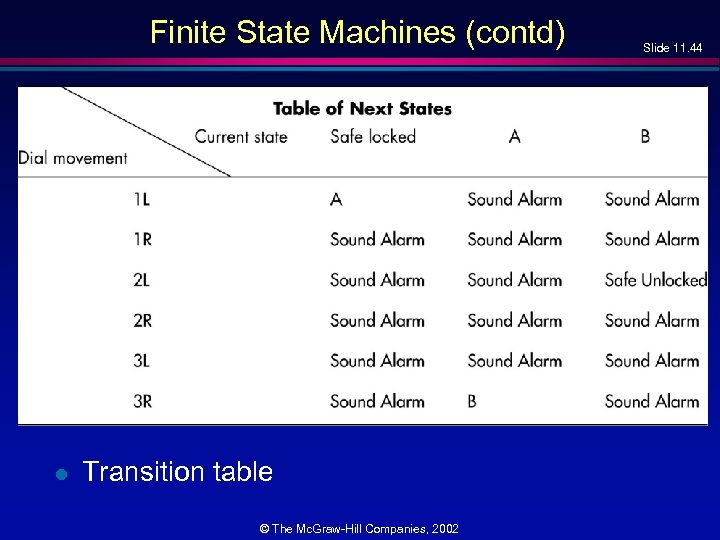

Finite State Machines (contd) l Transition table © The Mc. Graw-Hill Companies, 2002 Slide 11. 44

Extended Finite State Machines l l Extend FSM with global predicates Transition rules have form state and event and predicate Þ new state © The Mc. Graw-Hill Companies, 2002 Slide 11. 45

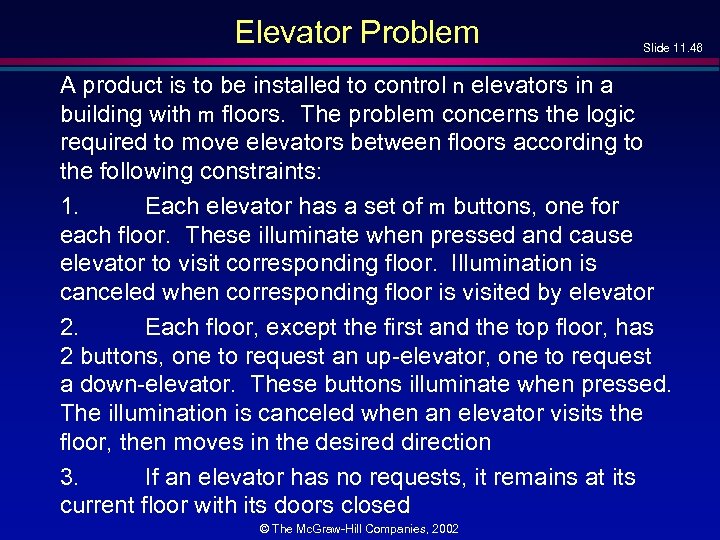

Elevator Problem Slide 11. 46 A product is to be installed to control n elevators in a building with m floors. The problem concerns the logic required to move elevators between floors according to the following constraints: 1. Each elevator has a set of m buttons, one for each floor. These illuminate when pressed and cause elevator to visit corresponding floor. Illumination is canceled when corresponding floor is visited by elevator 2. Each floor, except the first and the top floor, has 2 buttons, one to request an up-elevator, one to request a down-elevator. These buttons illuminate when pressed. The illumination is canceled when an elevator visits the floor, then moves in the desired direction 3. If an elevator has no requests, it remains at its current floor with its doors closed © The Mc. Graw-Hill Companies, 2002

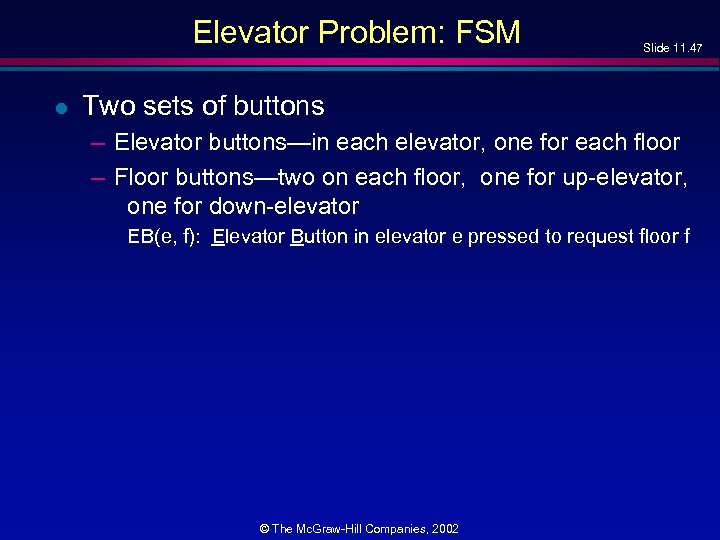

Elevator Problem: FSM l Slide 11. 47 Two sets of buttons – Elevator buttons—in each elevator, one for each floor – Floor buttons—two on each floor, one for up-elevator, one for down-elevator EB(e, f): Elevator Button in elevator e pressed to request floor f © The Mc. Graw-Hill Companies, 2002

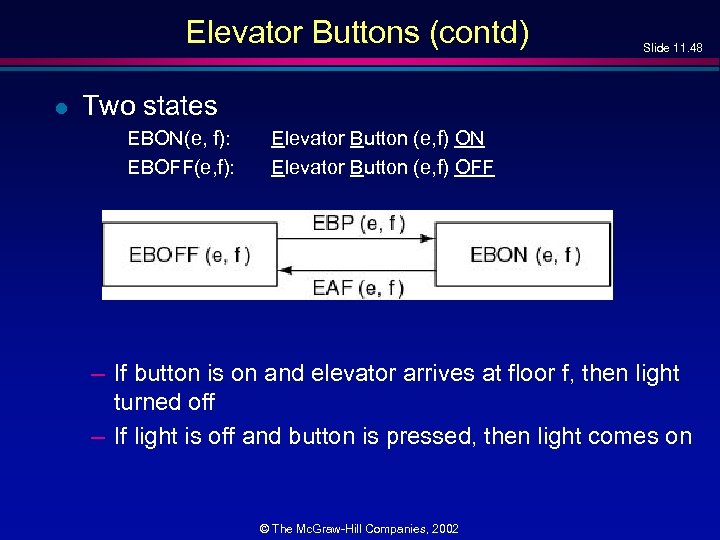

Elevator Buttons (contd) l Slide 11. 48 Two states EBON(e, f): EBOFF(e, f): Elevator Button (e, f) ON Elevator Button (e, f) OFF – If button is on and elevator arrives at floor f, then light turned off – If light is off and button is pressed, then light comes on © The Mc. Graw-Hill Companies, 2002

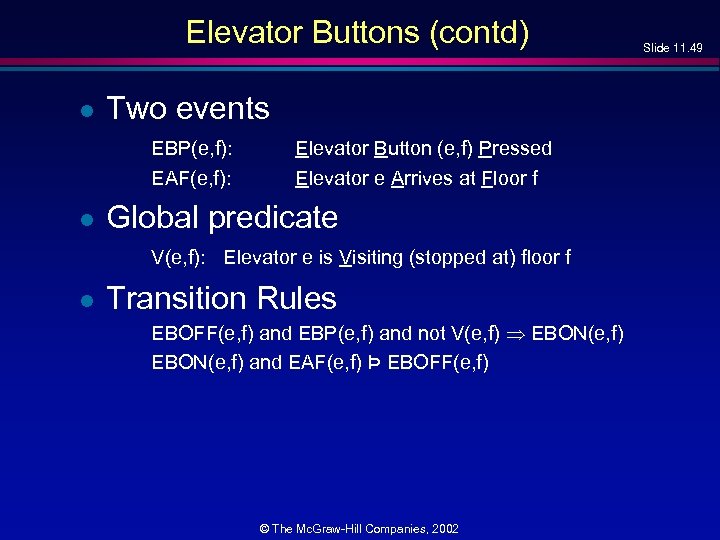

Elevator Buttons (contd) l Two events EBP(e, f): EAF(e, f): l Elevator Button (e, f) Pressed Elevator e Arrives at Floor f Global predicate V(e, f): Elevator e is Visiting (stopped at) floor f l Transition Rules EBOFF(e, f) and EBP(e, f) and not V(e, f) Þ EBON(e, f) and EAF(e, f) Þ EBOFF(e, f) © The Mc. Graw-Hill Companies, 2002 Slide 11. 49

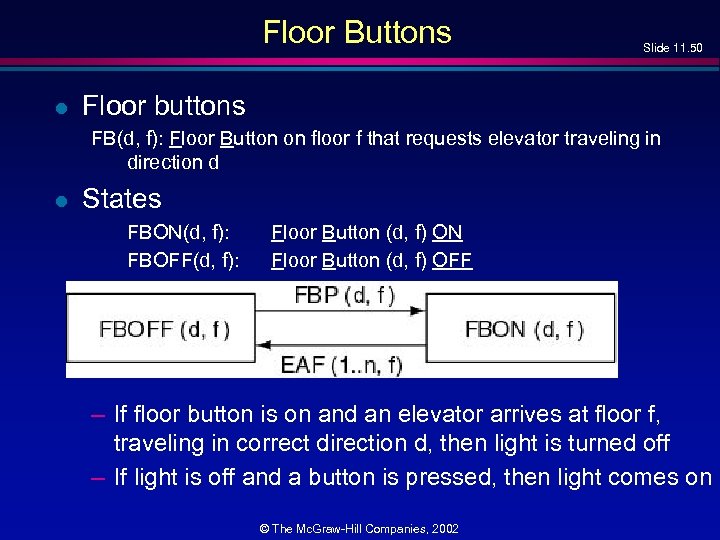

Floor Buttons l Slide 11. 50 Floor buttons FB(d, f): Floor Button on floor f that requests elevator traveling in direction d l States FBON(d, f): FBOFF(d, f): Floor Button (d, f) ON Floor Button (d, f) OFF – If floor button is on and an elevator arrives at floor f, traveling in correct direction d, then light is turned off – If light is off and a button is pressed, then light comes on © The Mc. Graw-Hill Companies, 2002

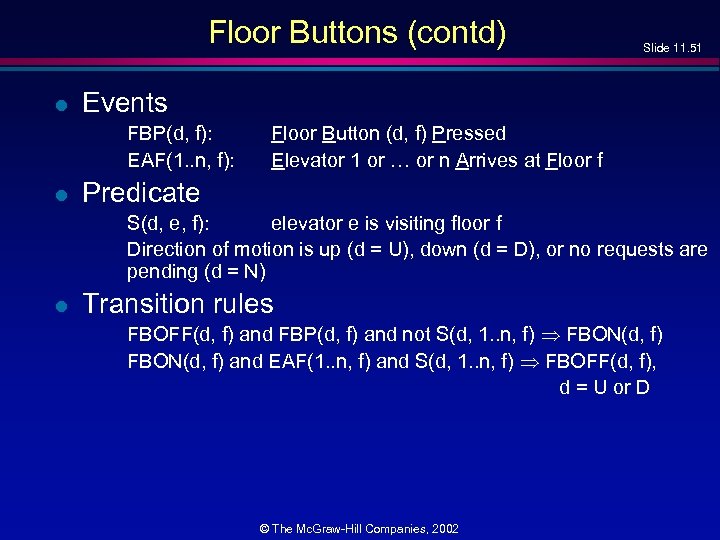

Floor Buttons (contd) l Events FBP(d, f): EAF(1. . n, f): l Slide 11. 51 Floor Button (d, f) Pressed Elevator 1 or … or n Arrives at Floor f Predicate S(d, e, f): elevator e is visiting floor f Direction of motion is up (d = U), down (d = D), or no requests are pending (d = N) l Transition rules FBOFF(d, f) and FBP(d, f) and not S(d, 1. . n, f) Þ FBON(d, f) and EAF(1. . n, f) and S(d, 1. . n, f) Þ FBOFF(d, f), d = U or D © The Mc. Graw-Hill Companies, 2002

Elevator Problem: FSM (contd) l State of elevator consists of component substates, including: – – – Elevator slowing Elevator stopping Door open with timer running Door closing after a timeout © The Mc. Graw-Hill Companies, 2002 Slide 11. 52

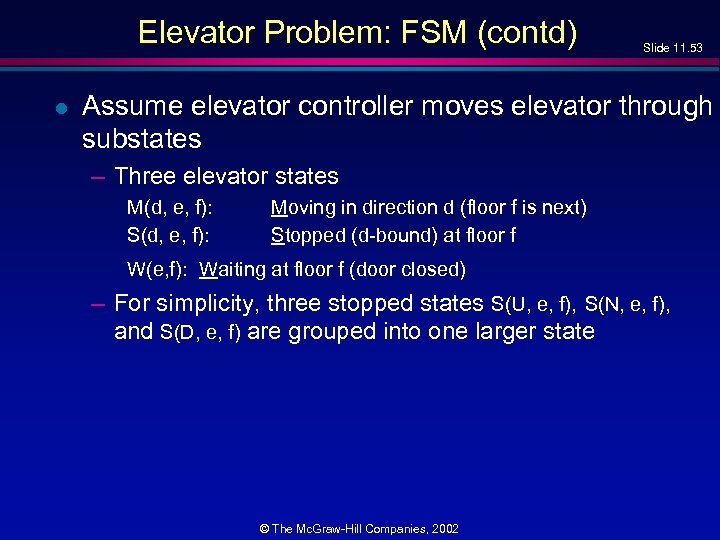

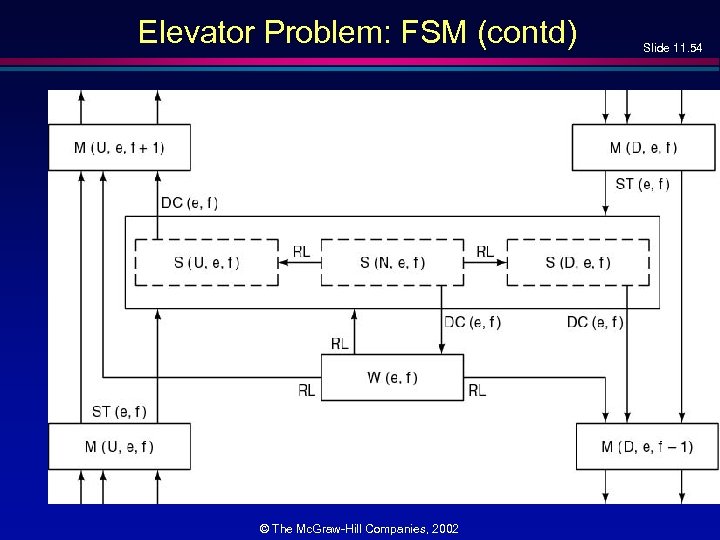

Elevator Problem: FSM (contd) l Slide 11. 53 Assume elevator controller moves elevator through substates – Three elevator states M(d, e, f): S(d, e, f): Moving in direction d (floor f is next) Stopped (d-bound) at floor f W(e, f): Waiting at floor f (door closed) – For simplicity, three stopped states S(U, e, f), S(N, e, f), and S(D, e, f) are grouped into one larger state © The Mc. Graw-Hill Companies, 2002

Elevator Problem: FSM (contd) © The Mc. Graw-Hill Companies, 2002 Slide 11. 54

Elevator Problem: FSM (contd) l Slide 11. 55 Events DC(e, f): Door Closed for elevator e, floor f ST(e, f): Sensor Triggered as elevator e nears floor f RL: l Request Logged (button pressed) Transition Rules If elevator e is in state S(d, e, f) (stopped, d-bound, at floor f), and doors close, then elevator e will move up, down, or go into wait state DC(e, f) and S(U, e, f) Þ M(U, e, f+1) DC(e, f) and S(D, e, f) Þ M(D, e, f-1) DC(e, f) and S(N, e, f) Þ W(e, f) © The Mc. Graw-Hill Companies, 2002

Power of FSM to Specify Complex Systems Slide 11. 56 l l No need for complex preconditions and postconditions Specifications take the simple form current state and event and predicate Þ next state © The Mc. Graw-Hill Companies, 2002

Power of FSM to Specify Complex Systems Slide 11. 57 l Using an FSM, a specification is – – – – l Easy to write down Easy to validate Easy to convert into design Easy to generate code automatically More precise than graphical methods Almost as easy to understand Easy to maintain However – Timing considerations are not handled © The Mc. Graw-Hill Companies, 2002

Who Is Using FSMs? l Commercial products – Menu driven – Various states/screens – Automatic code generation a major plus l System software – Operating system – Word processors – Spreadsheets l Real-time systems – Statecharts are a real-time extension of FSMs » CASE tool: Rhapsody © The Mc. Graw-Hill Companies, 2002 Slide 11. 58

Petri Nets l A major difficulty with specifying real-time systems is timing – Synchronization problems – Race conditions – Deadlock l Often a consequence of poor specifications © The Mc. Graw-Hill Companies, 2002 Slide 11. 59

Petri Nets (contd) l Petri nets – Powerful technique for specifying systems with potential timing problems l A Petri net consists of four parts: – – Set of places P Set of transitions T Input function I Output function O © The Mc. Graw-Hill Companies, 2002 Slide 11. 60

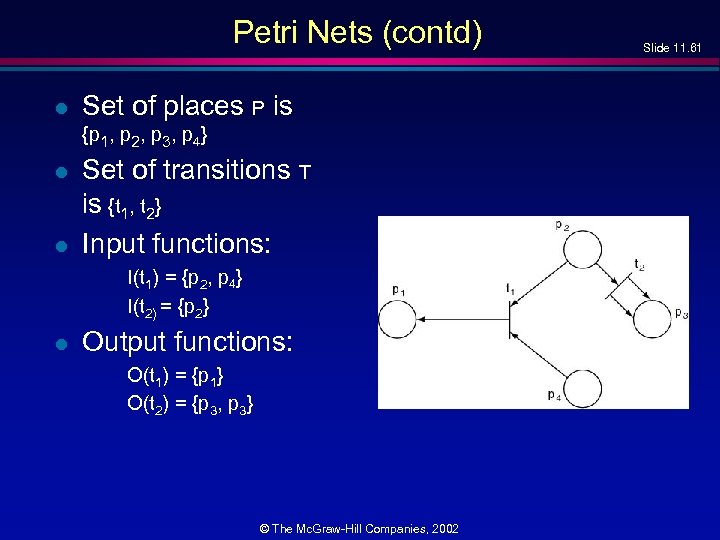

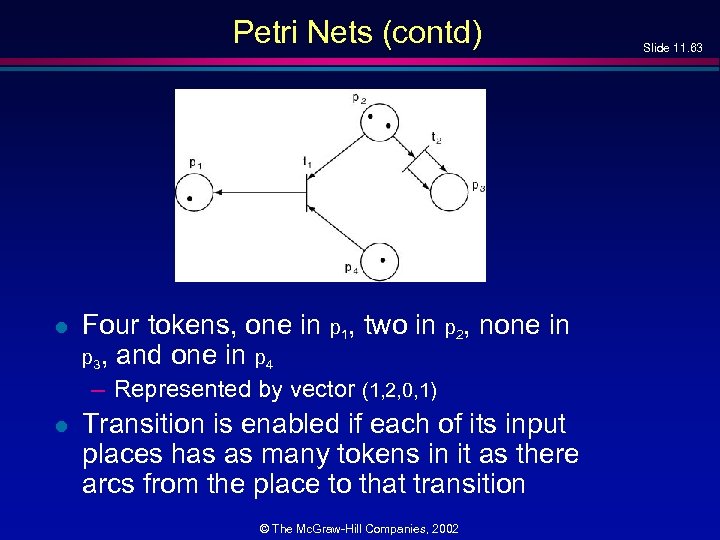

Petri Nets (contd) l Set of places P is {p 1, p 2, p 3, p 4} l l Set of transitions T is {t 1, t 2} Input functions: I(t 1) = {p 2, p 4} I(t 2) = {p 2} l Output functions: O(t 1) = {p 1} O(t 2) = {p 3, p 3} © The Mc. Graw-Hill Companies, 2002 Slide 11. 61

Petri Nets (contd) l l l l Slide 11. 62 More formally, a Petri net is a 4 -tuple C = (P, T, I, O) P = {p 1, p 2, …, pn} is a finite set of places, n ≥ 0 T = {t 1, t 2, …, tm} is a finite set of transitions, m ≥ 0, with P and T disjoint I : T ® P∞ is input function, mapping from transitions to bags of places O : T ® P∞ is output function, mapping from transitions to bags of places (A bag is a generalization of sets which allows for multiple instances of element in bag, as in example above) Marking of a Petri net is an assignment of tokens to that Petri net © The Mc. Graw-Hill Companies, 2002

Petri Nets (contd) l Four tokens, one in p 1, two in p 2, none in p 3, and one in p 4 – Represented by vector (1, 2, 0, 1) l Transition is enabled if each of its input places has as many tokens in it as there arcs from the place to that transition © The Mc. Graw-Hill Companies, 2002 Slide 11. 63

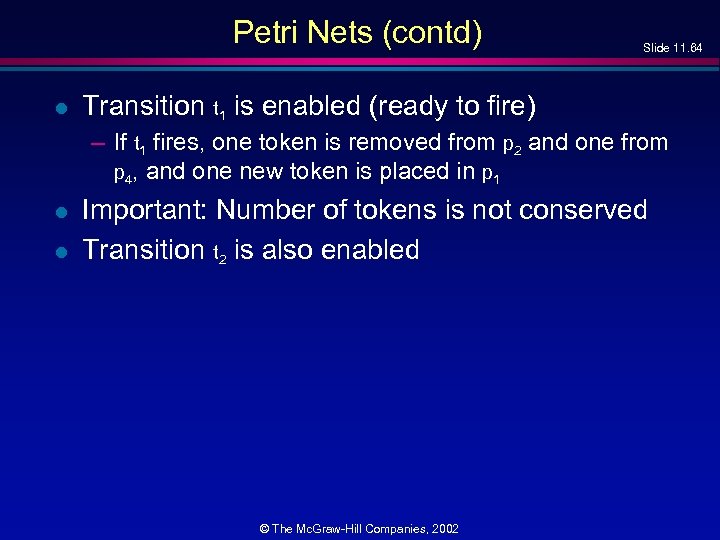

Petri Nets (contd) l Slide 11. 64 Transition t 1 is enabled (ready to fire) – If t 1 fires, one token is removed from p 2 and one from p 4, and one new token is placed in p 1 l l Important: Number of tokens is not conserved Transition t 2 is also enabled © The Mc. Graw-Hill Companies, 2002

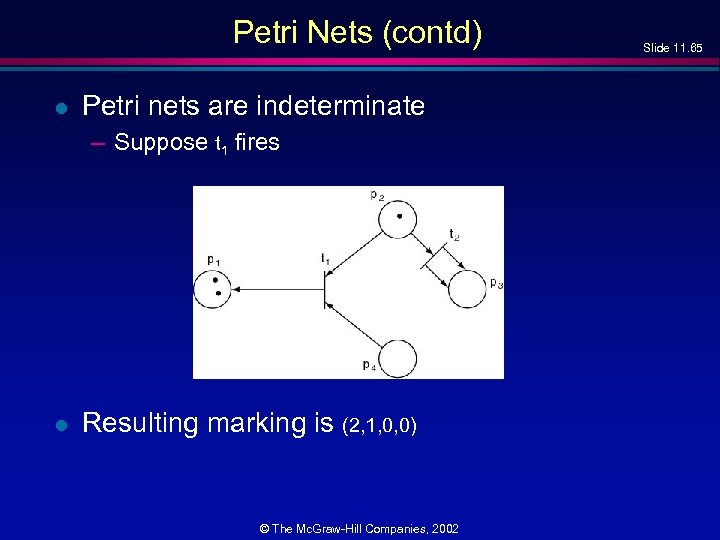

Petri Nets (contd) l Petri nets are indeterminate – Suppose t 1 fires l Resulting marking is (2, 1, 0, 0) © The Mc. Graw-Hill Companies, 2002 Slide 11. 65

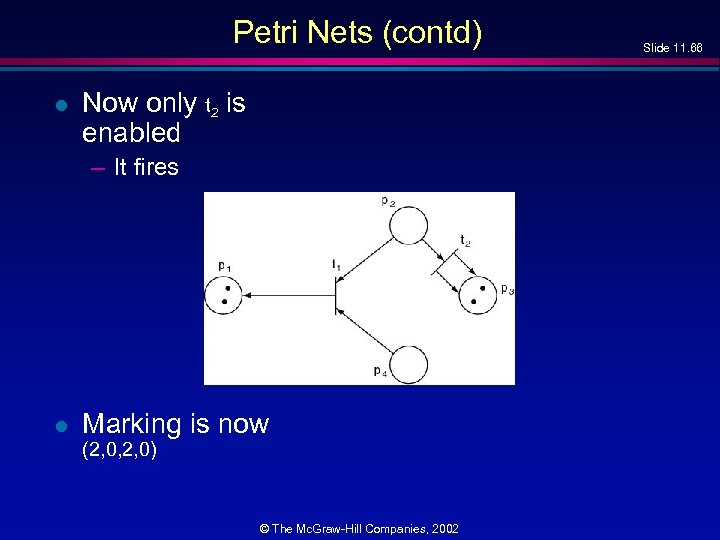

Petri Nets (contd) l Now only t 2 is enabled – It fires l Marking is now (2, 0, 2, 0) © The Mc. Graw-Hill Companies, 2002 Slide 11. 66

Petri Nets (contd) l More formally, a marking M of a Petri net C = (P, T, I, O) is a function from the set of places P to the non-negative integers N M : P ® N l Slide 11. 67 A marked Petri net is then 5 -tuple (P, T, I, O, M ) © The Mc. Graw-Hill Companies, 2002

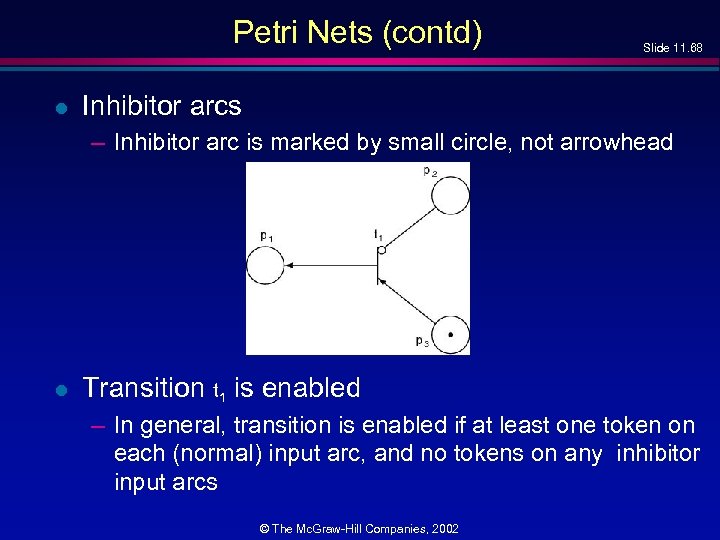

Petri Nets (contd) l Slide 11. 68 Inhibitor arcs – Inhibitor arc is marked by small circle, not arrowhead l Transition t 1 is enabled – In general, transition is enabled if at least one token on each (normal) input arc, and no tokens on any inhibitor input arcs © The Mc. Graw-Hill Companies, 2002

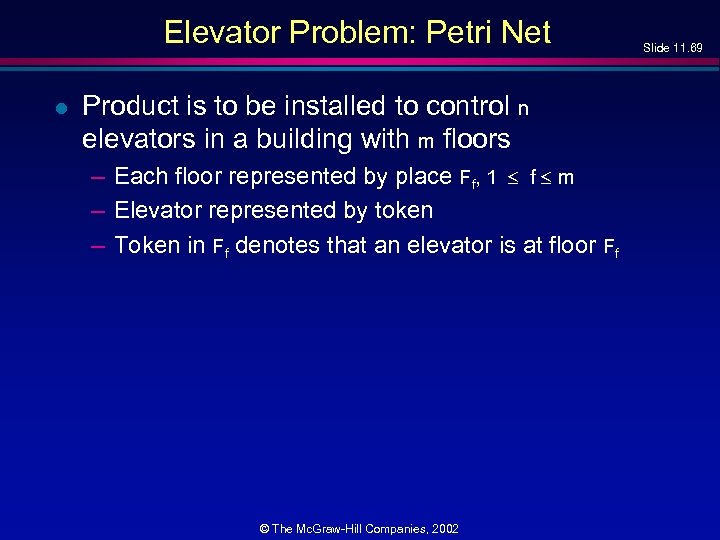

Elevator Problem: Petri Net l Product is to be installed to control n elevators in a building with m floors – Each floor represented by place Ff, 1 f m – Elevator represented by token – Token in Ff denotes that an elevator is at floor Ff © The Mc. Graw-Hill Companies, 2002 Slide 11. 69

Elevator Problem: Petri Net (contd) l First constraint 1. Each elevator has a set of m buttons, one for each floor. These illuminate when pressed and cause the elevator to visit the corresponding floor. The illumination is canceled when the corresponding floor is visited by an elevator l l Elevator button for floor f is represented by place EBf, 1 f m Token in EBf denotes that the elevator button for floor f is illuminated © The Mc. Graw-Hill Companies, 2002 Slide 11. 70

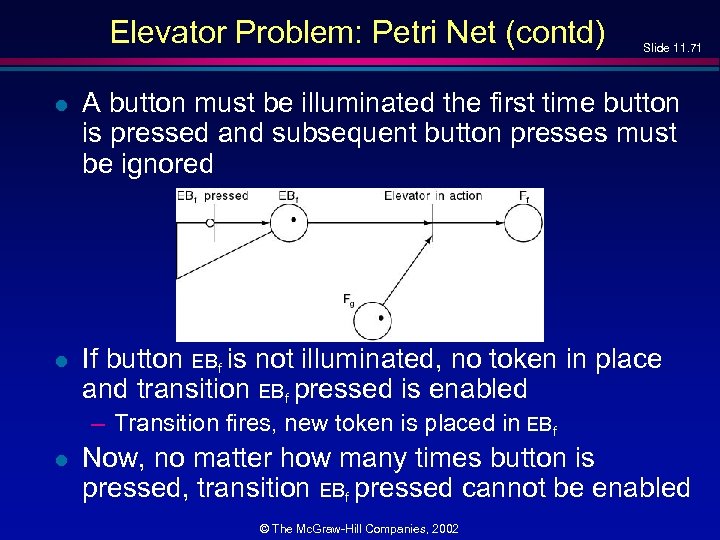

Elevator Problem: Petri Net (contd) Slide 11. 71 l A button must be illuminated the first time button is pressed and subsequent button presses must be ignored l If button EBf is not illuminated, no token in place and transition EBf pressed is enabled – Transition fires, new token is placed in EBf l Now, no matter how many times button is pressed, transition EBf pressed cannot be enabled © The Mc. Graw-Hill Companies, 2002

Elevator Problem: Petri Net (contd) l Slide 11. 72 When elevator reaches floor g, token is in place Fg, transition Elevator in action is enabled, and then fires – – Tokens in EBf and Fg removed This turns off light in button EBf New token appears in Ff This brings elevator from floor g to floor f © The Mc. Graw-Hill Companies, 2002

Elevator Problem: Petri Net (contd) l Motion from floor g to floor f cannot take place instantaneously – Timed Petri nets © The Mc. Graw-Hill Companies, 2002 Slide 11. 73

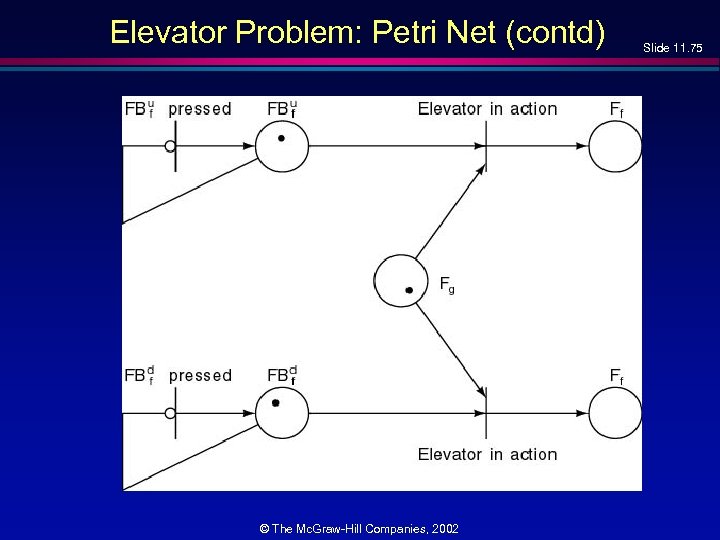

Elevator Problem: Petri Net (contd) l Slide 11. 74 Second constraint 2. Each floor, except the first and the top floor, has 2 buttons, one to request an up-elevator, one to request a down-elevator. These buttons illuminate when pressed. The illumination is canceled when the elevator visits the floor, and then moves in desired direction l Floor buttons represented by places FBuf and FBdf © The Mc. Graw-Hill Companies, 2002

Elevator Problem: Petri Net (contd) © The Mc. Graw-Hill Companies, 2002 Slide 11. 75

Elevator Problem: Petri Net (contd) l Slide 11. 76 The situation when an elevator reaches floor f from floor g with one or both buttons illuminated – If both buttons are illuminated, only one is turned off – (A more complex model is needed to ensure that the correct light is turned off) © The Mc. Graw-Hill Companies, 2002

Elevator Problem: Petri Net (contd) l Slide 11. 77 Third constraint C 3. If an elevator has no requests, it remains at its current floor with its doors closed l If no requests, no Elevator in action transition is enabled © The Mc. Graw-Hill Companies, 2002

Petri Nets (contd) l l Petri nets can also be used for design Petri nets possess the expressive power necessary for specifying timing aspects of real-time systems © The Mc. Graw-Hill Companies, 2002 Slide 11. 78

Z (“zed”) l l l Formal specification language High squiggle factor Z specification consists of four sections: – – 1. 2. 3. 4. Given sets, data types, and constants State definition Initial state Operations © The Mc. Graw-Hill Companies, 2002 Slide 11. 79

Elevator Problem: Z l 1. Given Sets l Sets that need not be defined in detail – Names appear in brackets – Here we need the set of all buttons – Specification begins [Button] © The Mc. Graw-Hill Companies, 2002 Slide 11. 80

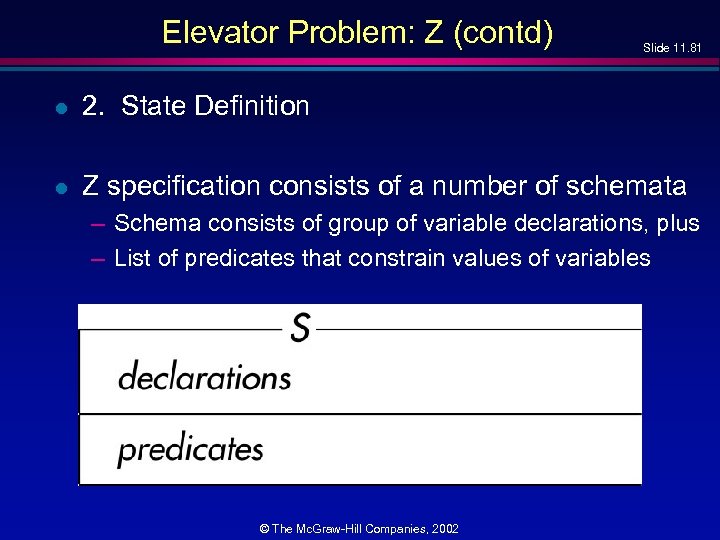

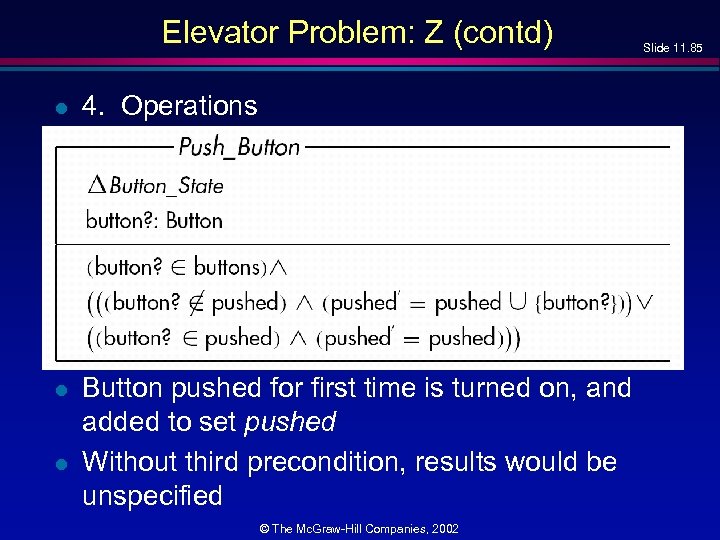

Elevator Problem: Z (contd) Slide 11. 81 l 2. State Definition l Z specification consists of a number of schemata – Schema consists of group of variable declarations, plus – List of predicates that constrain values of variables © The Mc. Graw-Hill Companies, 2002

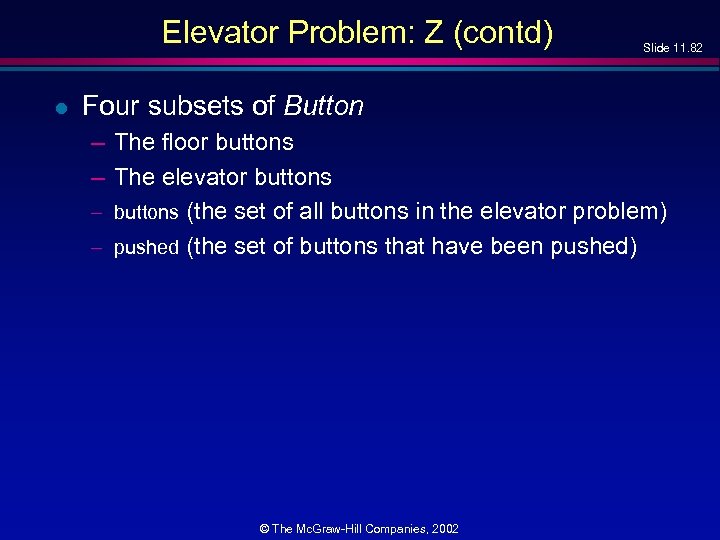

Elevator Problem: Z (contd) l Slide 11. 82 Four subsets of Button – The floor buttons – The elevator buttons – buttons (the set of all buttons in the elevator problem) – pushed (the set of buttons that have been pushed) © The Mc. Graw-Hill Companies, 2002

Elevator Problem: Z (contd) l Schema Button_State © The Mc. Graw-Hill Companies, 2002 Slide 11. 83

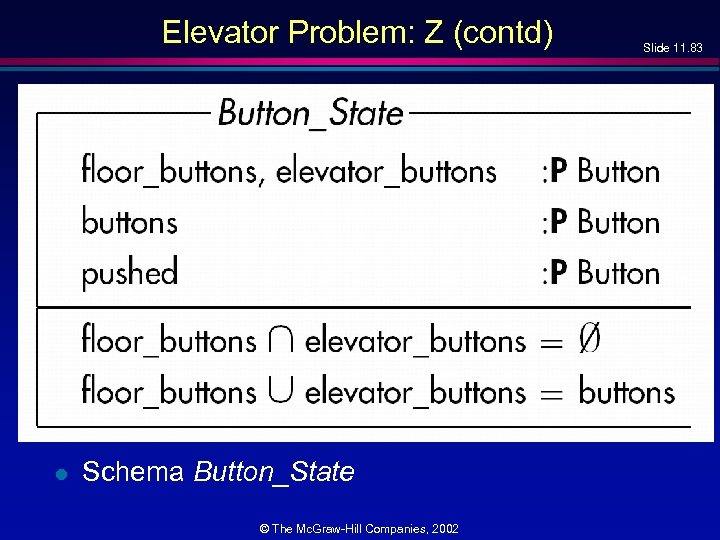

Elevator Problem: Z (contd) l 3. Initial State l Slide 11. 84 State when the system is first turned on Button_Init [Button_State' | pushed' = ] – (In the above equation, the should be a = with a ^ on top. Unfortunately, this is hard to type in Power. Point!) © The Mc. Graw-Hill Companies, 2002

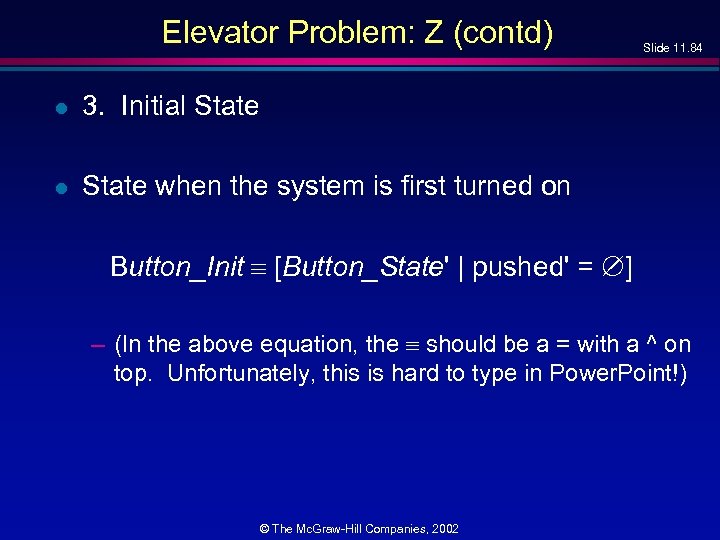

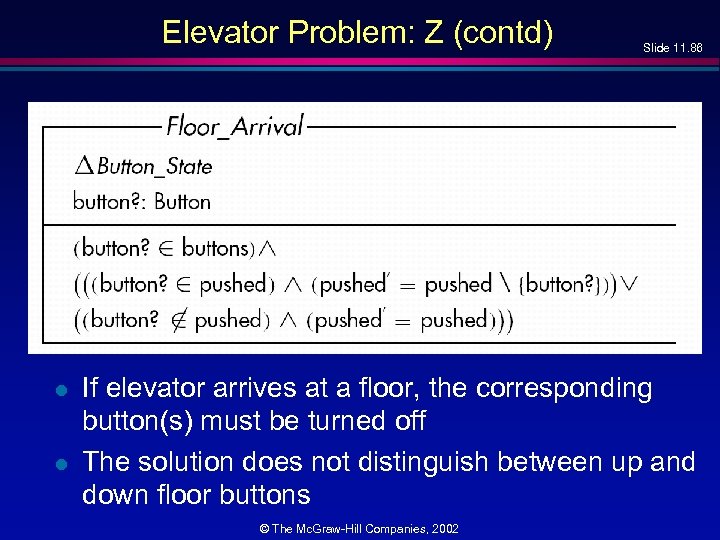

Elevator Problem: Z (contd) l 4. Operations l Button pushed for first time is turned on, and added to set pushed Without third precondition, results would be unspecified l © The Mc. Graw-Hill Companies, 2002 Slide 11. 85

Elevator Problem: Z (contd) l l Slide 11. 86 If elevator arrives at a floor, the corresponding button(s) must be turned off The solution does not distinguish between up and down floor buttons © The Mc. Graw-Hill Companies, 2002

Analysis of Z l Slide 11. 87 Most widely used formal specification language – – CICS (part) Oscilloscope CASE tool Large-scale projects (esp. Europe) © The Mc. Graw-Hill Companies, 2002

Analysis of Z (contd) l Difficulties – Symbols – Mathematics l Reasons for great success – – – Easy to find faults in Z specification Specifier must be extremely precise Can prove correctness Only high-school math needed to read Z Decreases development time “Translation” clearer than informal specification © The Mc. Graw-Hill Companies, 2002 Slide 11. 88

Other Formal Methods l Anna – Ada l Gist, Refine – Knowledge-based l VDM – Denotational semantics l CSP – Sequence of events – Executable specifications – High squiggle factor © The Mc. Graw-Hill Companies, 2002 Slide 11. 89

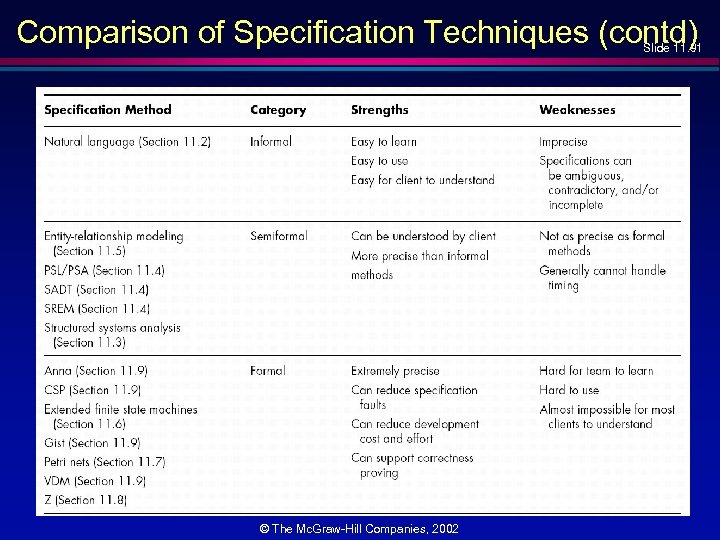

Comparison of Specification Techniques l l We must always choose the appropriate specification method Formal methods – Powerful – Difficult to learn and use l Informal methods – Little power – Easy to learn and use l Trade-off – Ease of use versus power © The Mc. Graw-Hill Companies, 2002 Slide 11. 90

Comparison of Specification Techniques (contd) Slide 11. 91 © The Mc. Graw-Hill Companies, 2002

Newer Methods l l Many are untested in practice Risks – Training costs – Adjustment from classroom to actual project – CASE tools may not work properly l However, possible gains may be huge © The Mc. Graw-Hill Companies, 2002 Slide 11. 92

Which Specification Method to Use? l Depends on the – – l Project Development team Management team Myriad other factors It is unwise to ignore the latest developments © The Mc. Graw-Hill Companies, 2002 Slide 11. 93

![Testing during the Specification Phase l Specification inspection – Checklist l Doolan [1992] – Testing during the Specification Phase l Specification inspection – Checklist l Doolan [1992] –](https://present5.com/presentation/9a43835cffe3dd03f6c9731c82a1a4f0/image-94.jpg)

Testing during the Specification Phase l Specification inspection – Checklist l Doolan [1992] – 2 million lines of FORTRAN – 1 hour of inspecting saved 30 hours of execution-based testing © The Mc. Graw-Hill Companies, 2002 Slide 11. 94

CASE Tools for the Specification Phase l l Slide 11. 95 Graphical tool Data dictionary – Integrate them l Specification method without CASE tools fails – SREM © The Mc. Graw-Hill Companies, 2002

CASE Tools for the Specification Phase l Typical tools – Analyst/Designer – Software through Pictures – System Architect © The Mc. Graw-Hill Companies, 2002 Slide 11. 96

Metrics for the Specification Phase l l Five fundamental metrics Quality – Fault statistics – Number, type of each fault – Rate of detection l Metrics for “predicting” size of target product – Total number of items in data dictionary – Number of items of each type – Processes vs. modules © The Mc. Graw-Hill Companies, 2002 Slide 11. 97

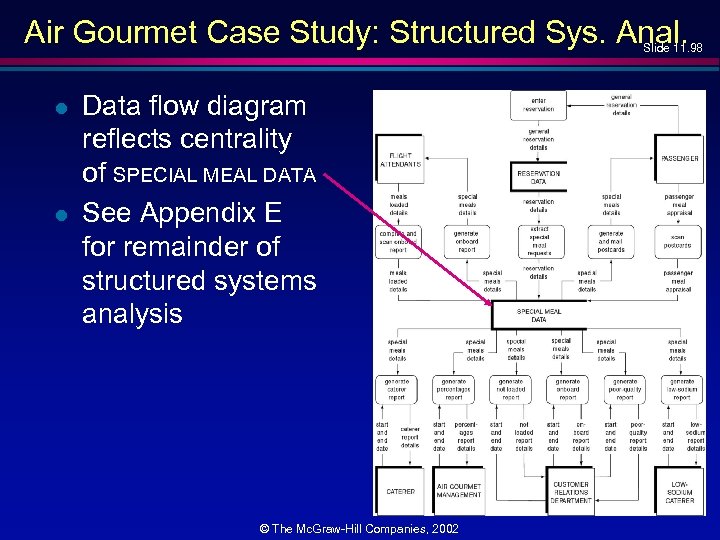

Air Gourmet Case Study: Structured Sys. Anal. Slide 11. 98 l l Data flow diagram reflects centrality of SPECIAL MEAL DATA See Appendix E for remainder of structured systems analysis © The Mc. Graw-Hill Companies, 2002

Air Gourmet Case Study: SPMP l Slide 11. 99 The Software Project Management Plan is given in Appendix F © The Mc. Graw-Hill Companies, 2002

Challenges of the Specification Phase l Slide 11. 100 A specification document must be – Informal enough for the client; and – Formal enough for the development team l l The specification phase (“what”) should not cross the boundary into the design phase (“how”) Do not try to assign modules to process boxes of DFDs until the design phase © The Mc. Graw-Hill Companies, 2002

9a43835cffe3dd03f6c9731c82a1a4f0.ppt