2015, Aug 14 - Working memory.pptx

- Количество слайдов: 46

• Short-term memory is a storage for holding small amounts of information for active usage within very short time • Short-term memory usually includes 7 ± 2 items it can operate with • All the data within short memory, that was not focused on, is wiped within 20 -30 seconds

• Short-term memory is a storage for holding small amounts of information for active usage within very short time • Short-term memory usually includes 7 ± 2 items it can operate with • All the data within short memory, that was not focused on, is wiped within 20 -30 seconds

• The Magical Number Seven, Plus or Minus Two: Some Limits on Our Capacity for Processing Information • George Armitage Miller, an American psychologist, wrote an article with such name in 1956, simply called Miller’s article, which first addressed the problem of the short-term memory, and still is one of the most cited articles from psychology. • Miller worked out that generally the short-term memory of the healthy young adult can hold up to 7 ± 2 items

• The Magical Number Seven, Plus or Minus Two: Some Limits on Our Capacity for Processing Information • George Armitage Miller, an American psychologist, wrote an article with such name in 1956, simply called Miller’s article, which first addressed the problem of the short-term memory, and still is one of the most cited articles from psychology. • Miller worked out that generally the short-term memory of the healthy young adult can hold up to 7 ± 2 items

• More to it, the amount of information that can be stored as an item inside the memory, varies – and it is called a chunk. One chunk can be an abstract letter, a digit, a word or even in some cases a sentence. • For example, for a native speaker a long idiom can be a chunk; and for a learner, even one word might have several phonetic chunks he needs to try and remember it whole

• More to it, the amount of information that can be stored as an item inside the memory, varies – and it is called a chunk. One chunk can be an abstract letter, a digit, a word or even in some cases a sentence. • For example, for a native speaker a long idiom can be a chunk; and for a learner, even one word might have several phonetic chunks he needs to try and remember it whole

• Short-term memory is different from working memory. • Working memory is ability to use short-term memory to keep focused attention on the matter. • It is also connected with ability to plan, set goals and initiate actions.

• Short-term memory is different from working memory. • Working memory is ability to use short-term memory to keep focused attention on the matter. • It is also connected with ability to plan, set goals and initiate actions.

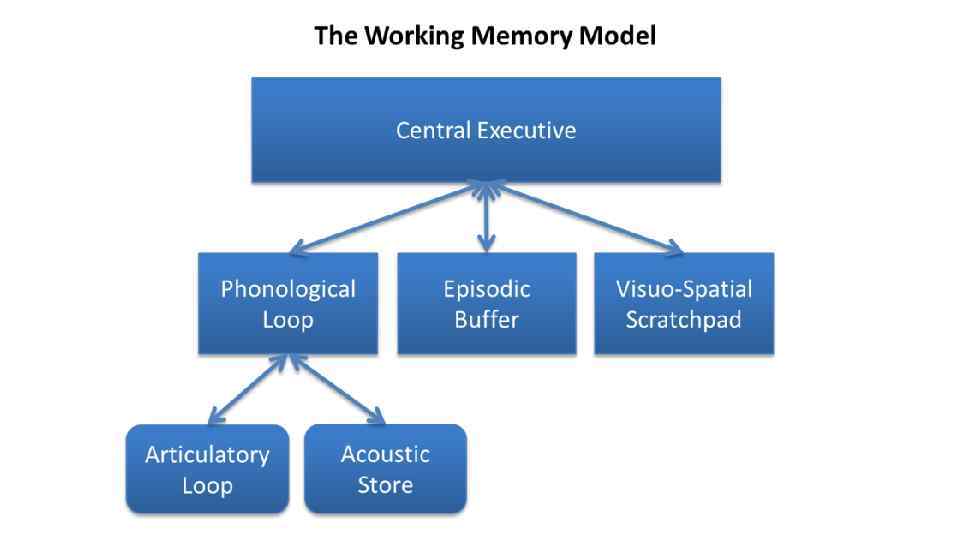

• Phonological loop helps you if you repeat something over and it is kept in your short-term memory • Visuo-spatial (dimensional) sketchpad stores visual and spatial information – a person can recreate images, landscape and orient in space • Episodic buffer deals with integrating different kinds of information together – giving opportunity to keep in mind more complicated chunks such as melodies or idioms.

• Phonological loop helps you if you repeat something over and it is kept in your short-term memory • Visuo-spatial (dimensional) sketchpad stores visual and spatial information – a person can recreate images, landscape and orient in space • Episodic buffer deals with integrating different kinds of information together – giving opportunity to keep in mind more complicated chunks such as melodies or idioms.

8768635

8768635

6392289

6392289

4532679

4532679

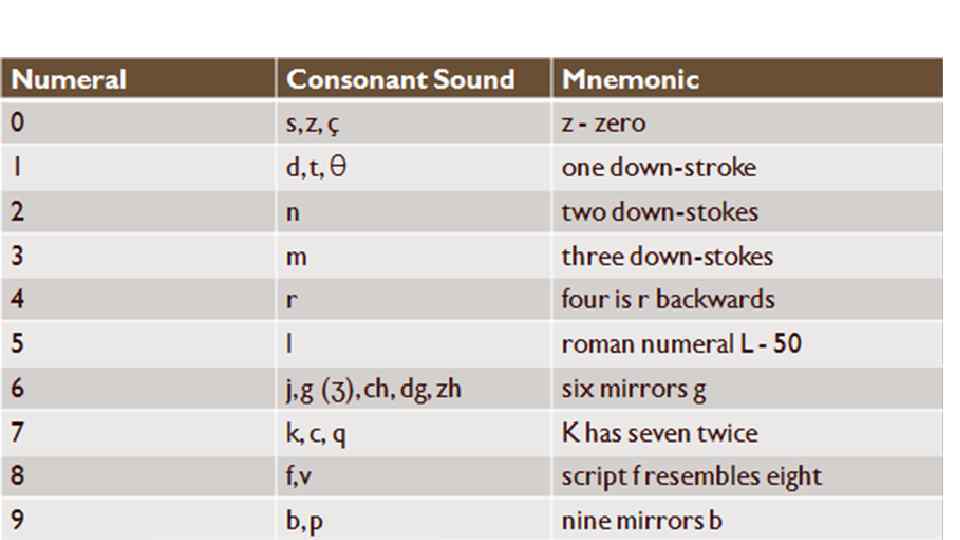

6910740

6910740

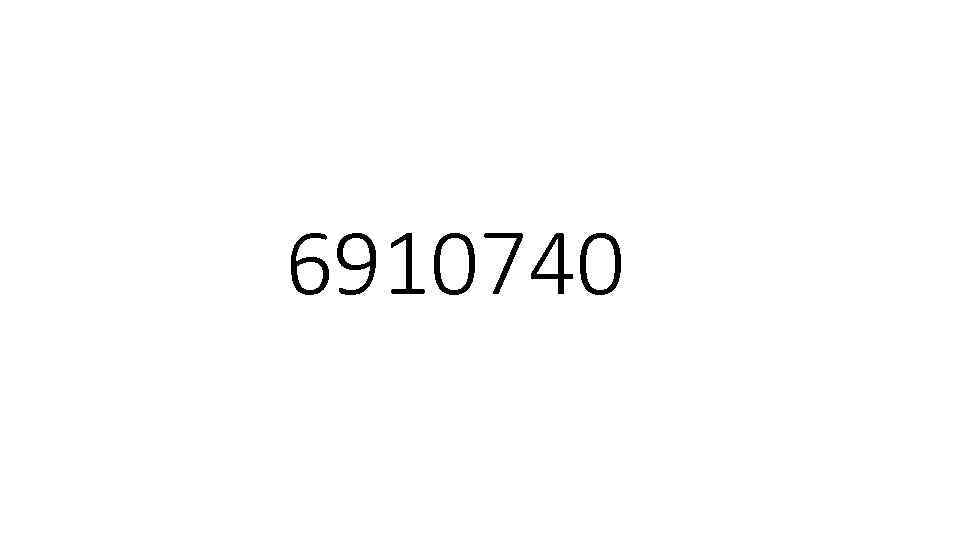

5542858

5542858

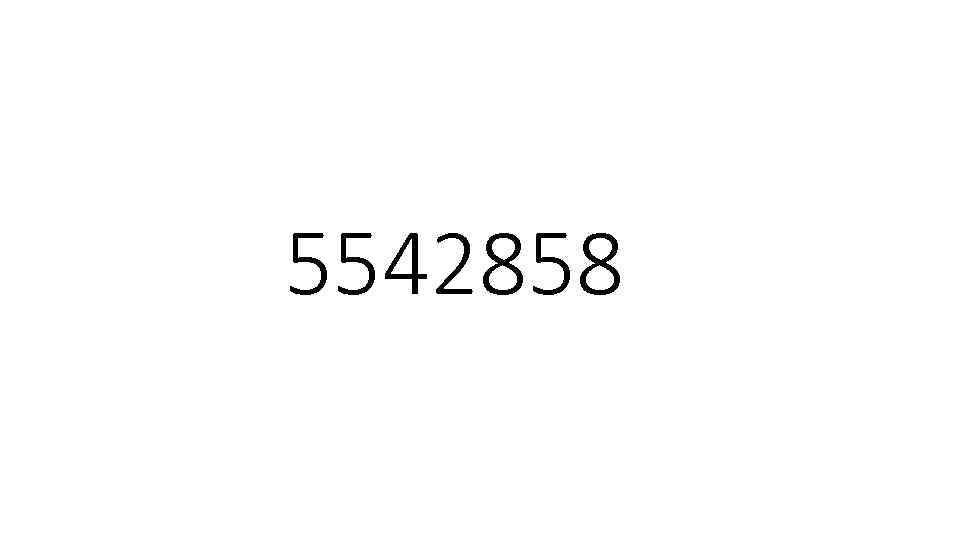

5046684

5046684

6442737

6442737

8944409

8944409

8521931

8521931

4069543

4069543

whirlgig

whirlgig

Kite, puzzle

Kite, puzzle

sofa armchair bed chair table nightstand stool mirror

sofa armchair bed chair table nightstand stool mirror

glasses ball binoculars bike magnifying glass jewelry box leash bulb

glasses ball binoculars bike magnifying glass jewelry box leash bulb

rubik’s cube globe camera pliers wheelbarrow alarm clock balloon dice

rubik’s cube globe camera pliers wheelbarrow alarm clock balloon dice

umbrella Tool knife case present box comp mouse axe drill book

umbrella Tool knife case present box comp mouse axe drill book

Scissors water colors rubber guitar Paper knife Marker Pen thread ball

Scissors water colors rubber guitar Paper knife Marker Pen thread ball

• August the 21 st

• August the 21 st

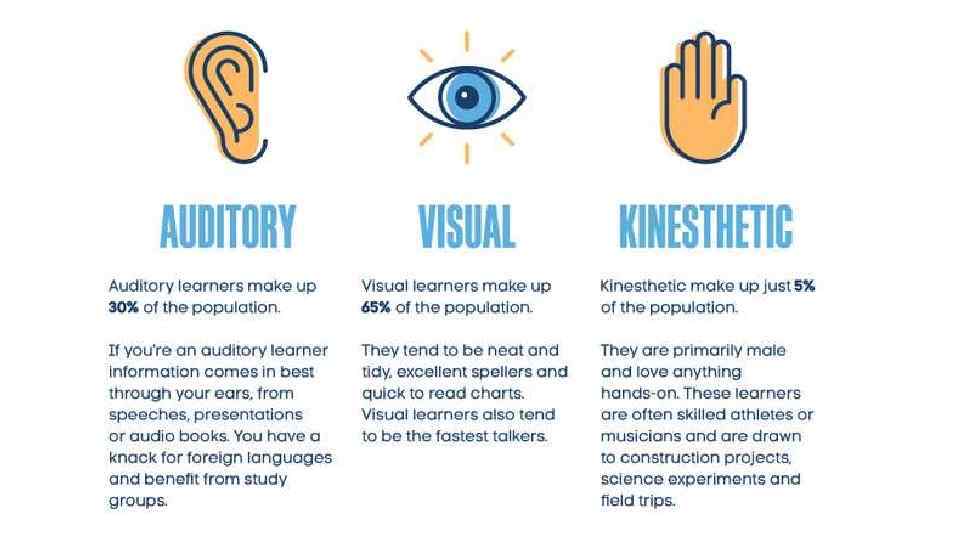

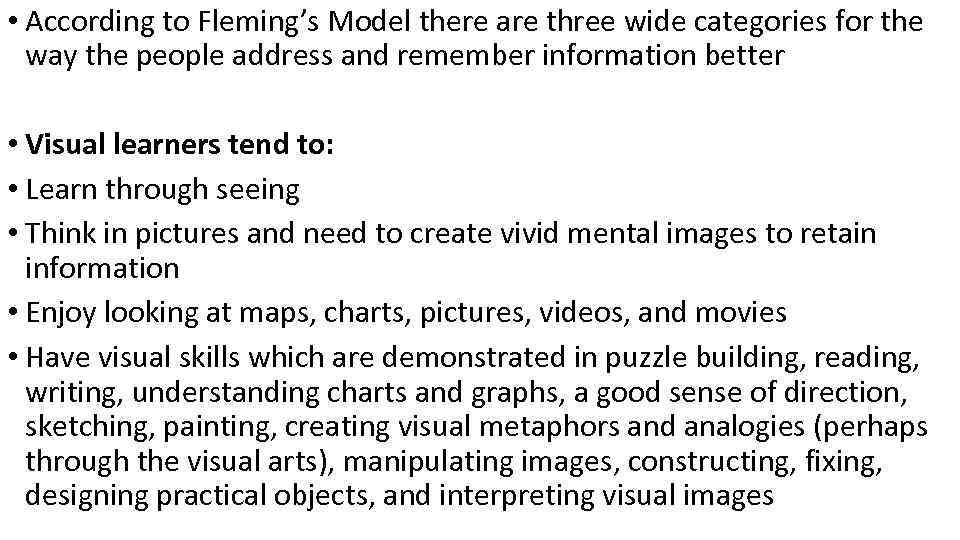

• According to Fleming’s Model there are three wide categories for the way the people address and remember information better • Visual learners tend to: • Learn through seeing • Think in pictures and need to create vivid mental images to retain information • Enjoy looking at maps, charts, pictures, videos, and movies • Have visual skills which are demonstrated in puzzle building, reading, writing, understanding charts and graphs, a good sense of direction, sketching, painting, creating visual metaphors and analogies (perhaps through the visual arts), manipulating images, constructing, fixing, designing practical objects, and interpreting visual images

• According to Fleming’s Model there are three wide categories for the way the people address and remember information better • Visual learners tend to: • Learn through seeing • Think in pictures and need to create vivid mental images to retain information • Enjoy looking at maps, charts, pictures, videos, and movies • Have visual skills which are demonstrated in puzzle building, reading, writing, understanding charts and graphs, a good sense of direction, sketching, painting, creating visual metaphors and analogies (perhaps through the visual arts), manipulating images, constructing, fixing, designing practical objects, and interpreting visual images

• Auditory learners tend to: • Learn through listening • Have highly developed auditory skills and are generally good at speaking and presenting • Think in words rather than pictures • Learn best through verbal lectures, discussions, talking things through and listening to what others have to say • Have auditory skills demonstrated in listening, speaking, writing, storytelling, explaining, teaching, using humour, understanding the syntax and meaning of words, remembering information, arguing their point of view, and analysing language usage

• Auditory learners tend to: • Learn through listening • Have highly developed auditory skills and are generally good at speaking and presenting • Think in words rather than pictures • Learn best through verbal lectures, discussions, talking things through and listening to what others have to say • Have auditory skills demonstrated in listening, speaking, writing, storytelling, explaining, teaching, using humour, understanding the syntax and meaning of words, remembering information, arguing their point of view, and analysing language usage

• Kinaesthetic learners tend to: • Learn through moving, doing and touching • Express themselves through movement • Have good sense of balance and eye-hand coordination • Remember and process information through interacting with the space around them • Find it hard to sit still for long periods and may become distracted by their need for activity and exploration • Have skills demonstrated in physical coordination, athletic ability, hands on experimentation, using body language, crafts, acting, miming, using their hands to create or build, dancing, and expressing emotions through the body.

• Kinaesthetic learners tend to: • Learn through moving, doing and touching • Express themselves through movement • Have good sense of balance and eye-hand coordination • Remember and process information through interacting with the space around them • Find it hard to sit still for long periods and may become distracted by their need for activity and exploration • Have skills demonstrated in physical coordination, athletic ability, hands on experimentation, using body language, crafts, acting, miming, using their hands to create or build, dancing, and expressing emotions through the body.

• WM capacity: How big is your child’s "mental workspace"? • Can you add together 23 and 69 in your head? When you ask for directions to the post office, can get there without writing the instructions down? Such tasks engage working memory, the memory we use to keep information immediately “in mind” so we can complete a task. • • It’s like a mental workspace or notepad—the “place” where we manipulate information, perform mental calculations, or form new thoughts. Just as different computers have different amounts of RAM, WM capacity varies from person to person. You can see this if you try giving the same verbal instructions to different kids. • • “Please give me the red pencil, then pick up the blue eraser and put it in the green box. ” • Some kids find this relatively easy. Others try to carry out the instructions, but lose track of the details along the way. This leads to trouble in the classroom

• WM capacity: How big is your child’s "mental workspace"? • Can you add together 23 and 69 in your head? When you ask for directions to the post office, can get there without writing the instructions down? Such tasks engage working memory, the memory we use to keep information immediately “in mind” so we can complete a task. • • It’s like a mental workspace or notepad—the “place” where we manipulate information, perform mental calculations, or form new thoughts. Just as different computers have different amounts of RAM, WM capacity varies from person to person. You can see this if you try giving the same verbal instructions to different kids. • • “Please give me the red pencil, then pick up the blue eraser and put it in the green box. ” • Some kids find this relatively easy. Others try to carry out the instructions, but lose track of the details along the way. This leads to trouble in the classroom

• Kids with low WM capacity may look like they aren’t paying attention. They often commit “place-keeping” errors, repeating or skipping words, letters, numbers, or whole steps of an assigned task. They may frequently abandon tasks altogether, not because they are lazy or uncooperative, but because they have lost track of what they are doing. • • The problem shows up in many different domains. Math immediately comes to mind, because we all have experience trying to do calculations “in our heads. ” But low WM capacity affects language, too. • • For instance, a child with low WM capacity may find it hard to write sentences. By the time he finishes spelling the first few words, he’s forgotten what he intended to say next. Similarly, he has trouble with reading comprehension. While he’s working hard to decode written words, he loses track of the overall “gist” of the text. • • WM seems to be a basic component of intelligence. It affects how kids learn. It also influences how kids perform on tests, including achievement tests and IQ tests. But we can’t equate WM with overall intelligence. For instance, working memory is not the same thing as IQ. Some kids perform well on IQ tests and yet have relatively mediocre WM skills.

• Kids with low WM capacity may look like they aren’t paying attention. They often commit “place-keeping” errors, repeating or skipping words, letters, numbers, or whole steps of an assigned task. They may frequently abandon tasks altogether, not because they are lazy or uncooperative, but because they have lost track of what they are doing. • • The problem shows up in many different domains. Math immediately comes to mind, because we all have experience trying to do calculations “in our heads. ” But low WM capacity affects language, too. • • For instance, a child with low WM capacity may find it hard to write sentences. By the time he finishes spelling the first few words, he’s forgotten what he intended to say next. Similarly, he has trouble with reading comprehension. While he’s working hard to decode written words, he loses track of the overall “gist” of the text. • • WM seems to be a basic component of intelligence. It affects how kids learn. It also influences how kids perform on tests, including achievement tests and IQ tests. But we can’t equate WM with overall intelligence. For instance, working memory is not the same thing as IQ. Some kids perform well on IQ tests and yet have relatively mediocre WM skills.

• How is this possible? Tests like the Wechsler Intelligence Scale for Children (WISC) have distinct subtests. Some specifically target WM, others don’t. And it’s likely that there are different kinds of working memory, too. Some kids may have especially poor auditory WM, so that they really struggle with spoken verbal instructions. Others may have very poor visual-spatial WM, making it difficult for them to keep up in math. • WM in the classroom: More important than IQ? • In a recent longitudinal study, Tracy and Ross Alloway measured the IQs and working memory skills of 5 -year-olds. Then, 6 years later, researchers tested the kids again, assessing not only IQ and WM, but also each child’s academic achievement in reading, spelling, and math. • • The results were sobering. Early WM skills were a better predictor of later academic achievement then were early IQ scores. And, unlike IQ, working memory did not correlate with the parents’ socioeconomic status or educational level.

• How is this possible? Tests like the Wechsler Intelligence Scale for Children (WISC) have distinct subtests. Some specifically target WM, others don’t. And it’s likely that there are different kinds of working memory, too. Some kids may have especially poor auditory WM, so that they really struggle with spoken verbal instructions. Others may have very poor visual-spatial WM, making it difficult for them to keep up in math. • WM in the classroom: More important than IQ? • In a recent longitudinal study, Tracy and Ross Alloway measured the IQs and working memory skills of 5 -year-olds. Then, 6 years later, researchers tested the kids again, assessing not only IQ and WM, but also each child’s academic achievement in reading, spelling, and math. • • The results were sobering. Early WM skills were a better predictor of later academic achievement then were early IQ scores. And, unlike IQ, working memory did not correlate with the parents’ socioeconomic status or educational level.

• Training Working Memory Can Be Fun • Biological reward comes from the release of the neurotransmitter, dopamine. Dopamine release is promoted by performing working memory tasks, which suggests that working memory tasks are actually rewarding. • • In the study of human subjects by Fiona Mc. Nab and colleagues in Stockholm, human males (age 20 -28) were trained for 35 minutes per day for five weeks on working memory tasks with a difficulty level close to their individual capacity limit. After such training, all subjects showed increased working memory capacity. • • Functional MRI scans also showed that the memory training increased amount of dopamine receptors, the ones that increase feelings of euphoria and reward.

• Training Working Memory Can Be Fun • Biological reward comes from the release of the neurotransmitter, dopamine. Dopamine release is promoted by performing working memory tasks, which suggests that working memory tasks are actually rewarding. • • In the study of human subjects by Fiona Mc. Nab and colleagues in Stockholm, human males (age 20 -28) were trained for 35 minutes per day for five weeks on working memory tasks with a difficulty level close to their individual capacity limit. After such training, all subjects showed increased working memory capacity. • • Functional MRI scans also showed that the memory training increased amount of dopamine receptors, the ones that increase feelings of euphoria and reward.

• Some games that are fun to play may also help working memory. The most obvious example is chess. To play chess well, you have to learn to expand working memory capacity to hold a plan for several offensive moves while at the same time holding a memory of how the opponent could respond to each of the moves. • • Not surprisingly there are studies showing that IQ scores can go up after several months of chess playing. Some schools, especially in minority schools have seen marked improvements in school work by students who joined school chess clubs. • • Students who make good grades feel good about their success. Likewise, people who are "life-long learners" have discovered learning lots of new things makes them feel good

• Some games that are fun to play may also help working memory. The most obvious example is chess. To play chess well, you have to learn to expand working memory capacity to hold a plan for several offensive moves while at the same time holding a memory of how the opponent could respond to each of the moves. • • Not surprisingly there are studies showing that IQ scores can go up after several months of chess playing. Some schools, especially in minority schools have seen marked improvements in school work by students who joined school chess clubs. • • Students who make good grades feel good about their success. Likewise, people who are "life-long learners" have discovered learning lots of new things makes them feel good

• What do you usually forget? • What do you need your memory most for? • Do you easily memorize information? • Do you have good memory for names/faces/numbers? • Does music or scents bring memories easier for you? • Do certain photographs bring back memories? • Has visiting childhood places ever been a bright experience for your memory? • Have you ever walked into a room and forgotten why you went there? • Do you train your memory? • How many English words a week do you remember? • What things is it important to remember? Why?

• What do you usually forget? • What do you need your memory most for? • Do you easily memorize information? • Do you have good memory for names/faces/numbers? • Does music or scents bring memories easier for you? • Do certain photographs bring back memories? • Has visiting childhood places ever been a bright experience for your memory? • Have you ever walked into a room and forgotten why you went there? • Do you train your memory? • How many English words a week do you remember? • What things is it important to remember? Why?