Lecture 8_Semantic Change.pptx

- Количество слайдов: 22

SEMANTIC CHANGES LECTURE 8

SEMANTIC CHANGES LECTURE 8

In diachronical and historical linguistics, semantic change is a change in the meaning of a word. The causes of language change in general (not only on the lexical level) are frequently of economic nature: speakers connect a speech act with a certain goal, a certain target, a certain intention. In general, constant linguistic change is not planned, but simply occurs, as a by-product.

In diachronical and historical linguistics, semantic change is a change in the meaning of a word. The causes of language change in general (not only on the lexical level) are frequently of economic nature: speakers connect a speech act with a certain goal, a certain target, a certain intention. In general, constant linguistic change is not planned, but simply occurs, as a by-product.

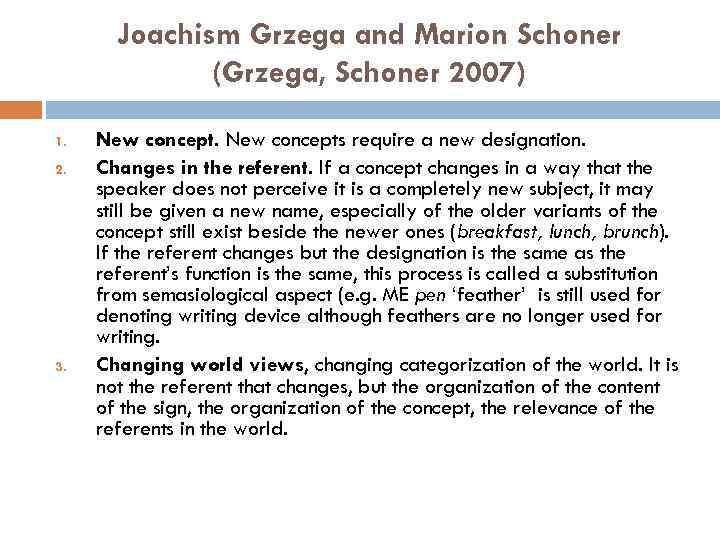

Joachism Grzega and Marion Schoner (Grzega, Schoner 2007) 1. 2. 3. New concepts require a new designation. Changes in the referent. If a concept changes in a way that the speaker does not perceive it is a completely new subject, it may still be given a new name, especially of the older variants of the concept still exist beside the newer ones (breakfast, lunch, brunch). If the referent changes but the designation is the same as the referent’s function is the same, this process is called a substitution from semasiological aspect (e. g. ME pen ‘feather’ is still used for denoting writing device although feathers are no longer used for writing. Changing world views, changing categorization of the world. It is not the referent that changes, but the organization of the content of the sign, the organization of the concept, the relevance of the referents in the world.

Joachism Grzega and Marion Schoner (Grzega, Schoner 2007) 1. 2. 3. New concepts require a new designation. Changes in the referent. If a concept changes in a way that the speaker does not perceive it is a completely new subject, it may still be given a new name, especially of the older variants of the concept still exist beside the newer ones (breakfast, lunch, brunch). If the referent changes but the designation is the same as the referent’s function is the same, this process is called a substitution from semasiological aspect (e. g. ME pen ‘feather’ is still used for denoting writing device although feathers are no longer used for writing. Changing world views, changing categorization of the world. It is not the referent that changes, but the organization of the content of the sign, the organization of the concept, the relevance of the referents in the world.

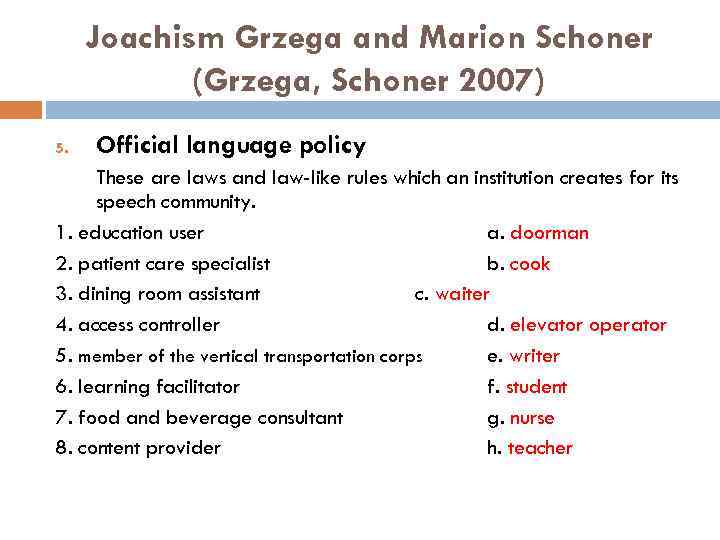

Joachism Grzega and Marion Schoner (Grzega, Schoner 2007) 5. Official language policy These are laws and law-like rules which an institution creates for its speech community. 1. education user a. doorman 2. patient care specialist b. cook 3. dining room assistant c. waiter 4. access controller d. elevator operator 5. member of the vertical transportation corps e. writer 6. learning facilitator f. student 7. food and beverage consultant g. nurse 8. content provider h. teacher

Joachism Grzega and Marion Schoner (Grzega, Schoner 2007) 5. Official language policy These are laws and law-like rules which an institution creates for its speech community. 1. education user a. doorman 2. patient care specialist b. cook 3. dining room assistant c. waiter 4. access controller d. elevator operator 5. member of the vertical transportation corps e. writer 6. learning facilitator f. student 7. food and beverage consultant g. nurse 8. content provider h. teacher

5. 6. Inofficial language policy. It does not evolve from any official institution but from members of the language community. Taboo and political correctness - the prohibition to designate things with their real name. Political correctness is a modern form of a taboo.

5. 6. Inofficial language policy. It does not evolve from any official institution but from members of the language community. Taboo and political correctness - the prohibition to designate things with their real name. Political correctness is a modern form of a taboo.

Joachism Grzega and Marion Schoner (Grzega, Schoner 2007) 8. 9. 10. Disguising language, “misnomers”. Misnomers are the words that individuals have decided to coin in order to deceive the hearer by disguising unpleasant concepts (e. g. friendly fire instead of “bombardment by own troops”). Flattery and insult. Flattery (e. g. gentleman gentle man) consciously keeps to the rule of a speech community, insult (e. g. whitey) consciously violates the rules). Prestige, fashion. English borrowed a lot of new words during the Middle English period because the upper-class were made up of French people: garment, rose, prince, hour, question.

Joachism Grzega and Marion Schoner (Grzega, Schoner 2007) 8. 9. 10. Disguising language, “misnomers”. Misnomers are the words that individuals have decided to coin in order to deceive the hearer by disguising unpleasant concepts (e. g. friendly fire instead of “bombardment by own troops”). Flattery and insult. Flattery (e. g. gentleman gentle man) consciously keeps to the rule of a speech community, insult (e. g. whitey) consciously violates the rules). Prestige, fashion. English borrowed a lot of new words during the Middle English period because the upper-class were made up of French people: garment, rose, prince, hour, question.

Joachism Grzega and Marion Schoner (Grzega, Schoner 2007) 11. Social or demographic reasons. The contact between the social groups may easily and subconsciously trigger off lexical change – the more intensive the social contact is, the more intensive is the linguistic change. Anthropological salience of a concept (natural salience). It is the nature of humans that some concepts automatically raise emotions and thus attract a large number of synonyms. Conceptual fields that are typically affected by this are found in the realm of the basics of life, feelings and values, attributes, hopes and expectations (for example in Germanic languages most designations for the basic concepts bad and good go to the same roots).

Joachism Grzega and Marion Schoner (Grzega, Schoner 2007) 11. Social or demographic reasons. The contact between the social groups may easily and subconsciously trigger off lexical change – the more intensive the social contact is, the more intensive is the linguistic change. Anthropological salience of a concept (natural salience). It is the nature of humans that some concepts automatically raise emotions and thus attract a large number of synonyms. Conceptual fields that are typically affected by this are found in the realm of the basics of life, feelings and values, attributes, hopes and expectations (for example in Germanic languages most designations for the basic concepts bad and good go to the same roots).

Joachism Grzega and Marion Schoner (Grzega, Schoner 2007) 13. Culture induced salience of a concept (cultural salience). The salience of some concepts can change with the change of the culture (from light blue and dark blue to a neat distinction between cobalt blue, royal blue, indigo etc. ). Such neat detailed differentiations often originate in expert slang and then penetrate the language of the general speech community.

Joachism Grzega and Marion Schoner (Grzega, Schoner 2007) 13. Culture induced salience of a concept (cultural salience). The salience of some concepts can change with the change of the culture (from light blue and dark blue to a neat distinction between cobalt blue, royal blue, indigo etc. ). Such neat detailed differentiations often originate in expert slang and then penetrate the language of the general speech community.

Joachism Grzega and Marion Schoner (Grzega, Schoner 2007) 14. Dominance of the prototype. The phenomenon that some members of the same conceptual field have a higher prominence than others may lead to the development of the gradual subconscious shift to terms denoting the prototype or the class that the prototype belongs to. One possible result of the process is generalization, or widening of meaning, of the original designation of the prototype (e. g. kleenex, originally the trademark for the specific tissue, is now used to refer to any kind of tissue). Another possible result is the specialization, or narrowing of the meaning (e. g. the word corn has been a restriction in use, from a general term to denote cereal to the term that denotes a kind of cereal that is prominent in a given region). A third possible result is that the designation of the prototype serves as the basis for the designation of concepts of the same hierarchical level (the prototypical fruit in Europe is the apple; other fruits and vegetables which were imported during the last centuries were named according to that term, as to be found in various European languages: pine-apple (English), Apfelsine (German – ‘orange’), Erdapfel (German – ‘potato’), sinnaasappel (Dutch – ‘orange’), pomme de terre (French – ‘potato’), pomodoro (Italian – ‘tomato’).

Joachism Grzega and Marion Schoner (Grzega, Schoner 2007) 14. Dominance of the prototype. The phenomenon that some members of the same conceptual field have a higher prominence than others may lead to the development of the gradual subconscious shift to terms denoting the prototype or the class that the prototype belongs to. One possible result of the process is generalization, or widening of meaning, of the original designation of the prototype (e. g. kleenex, originally the trademark for the specific tissue, is now used to refer to any kind of tissue). Another possible result is the specialization, or narrowing of the meaning (e. g. the word corn has been a restriction in use, from a general term to denote cereal to the term that denotes a kind of cereal that is prominent in a given region). A third possible result is that the designation of the prototype serves as the basis for the designation of concepts of the same hierarchical level (the prototypical fruit in Europe is the apple; other fruits and vegetables which were imported during the last centuries were named according to that term, as to be found in various European languages: pine-apple (English), Apfelsine (German – ‘orange’), Erdapfel (German – ‘potato’), sinnaasappel (Dutch – ‘orange’), pomme de terre (French – ‘potato’), pomodoro (Italian – ‘tomato’).

Joachism Grzega and Marion Schoner (Grzega, Schoner 2007) 16. 17. Wish for plasticity, which means the wish for clear, also figurative phrases. Onomatopoetic (sound-imitating) words, hyperbole and tautological compounds (the compounds where one element at least from a historical point of view semantically also included in the other element: peacock pea and (hound) dog, Martian instead of alien. Aesthetic-formal reasons: homonymic conflicts and polysemic conflicts. Polysemy is the extension of use of an already existing lexeme and thus a quite usual and economic way to find new designations. However, if one of the meanings fall into the domain of taboos, the entire word-form, including its other senses, might be banned; and here we could speak of polysemic conflict (e. g. in American English the word ass for ‘horse-like grey animal’ was substituted for donkey because the former sounds too much like arse ‘bottom, bum’).

Joachism Grzega and Marion Schoner (Grzega, Schoner 2007) 16. 17. Wish for plasticity, which means the wish for clear, also figurative phrases. Onomatopoetic (sound-imitating) words, hyperbole and tautological compounds (the compounds where one element at least from a historical point of view semantically also included in the other element: peacock pea and (hound) dog, Martian instead of alien. Aesthetic-formal reasons: homonymic conflicts and polysemic conflicts. Polysemy is the extension of use of an already existing lexeme and thus a quite usual and economic way to find new designations. However, if one of the meanings fall into the domain of taboos, the entire word-form, including its other senses, might be banned; and here we could speak of polysemic conflict (e. g. in American English the word ass for ‘horse-like grey animal’ was substituted for donkey because the former sounds too much like arse ‘bottom, bum’).

Joachism Grzega and Marion Schoner (Grzega, Schoner 2007) 18. 19. Communicative formal reasons: homonymic conflict. Homonymic conflicts evolve because of rapid speaking, and dropping the sounds at the end of the vowel, change in the phonetic system, cohabitation or concurrence of speakers of different dialects or languages, cultural reasons which cause originally unproblematic homonymy or polysemy to become conflictuous, change of meaning. If such conflicts occur, the language community basically uses such ways to dispose of the inconvenience: as 1) loss one or both words (e. g. queen ‘queen’ vs. quean ‘prostitute’ in Early Modern English – the latter has been replaced by several loanwords, indigenous words and new, word formations); 2) restriction of one of the words only to certain contexts (e. g. to weigh ‘to measure the weight’ vs. to weigh ‘to lift’, the latter only today in to weigh anchor). Word play which includes humor, irony and puns (e. g. perfect lady ‘prostitute’; to take French leave ‘to leave secretly, without paying’; to cool ‘look’ (back slang)).

Joachism Grzega and Marion Schoner (Grzega, Schoner 2007) 18. 19. Communicative formal reasons: homonymic conflict. Homonymic conflicts evolve because of rapid speaking, and dropping the sounds at the end of the vowel, change in the phonetic system, cohabitation or concurrence of speakers of different dialects or languages, cultural reasons which cause originally unproblematic homonymy or polysemy to become conflictuous, change of meaning. If such conflicts occur, the language community basically uses such ways to dispose of the inconvenience: as 1) loss one or both words (e. g. queen ‘queen’ vs. quean ‘prostitute’ in Early Modern English – the latter has been replaced by several loanwords, indigenous words and new, word formations); 2) restriction of one of the words only to certain contexts (e. g. to weigh ‘to measure the weight’ vs. to weigh ‘to lift’, the latter only today in to weigh anchor). Word play which includes humor, irony and puns (e. g. perfect lady ‘prostitute’; to take French leave ‘to leave secretly, without paying’; to cool ‘look’ (back slang)).

Joachism Grzega and Marion Schoner (Grzega, Schoner 2007) 20. 21. 22. Excessive length of words. An excessive length of a word can be the reason for lexical change if the word occurs frequently in the language (e. g. fax instead of telefax); this means that there is no general tendency to avoid long words. Morphological misinterpretation. This is an unconscious process of interpreting a meaningful senseful form into polysyllabic (and seemingly polymorphemic) words. We refer to the result of such process as folk-etymology (e. g. French contredanse was reinterpreted as country dance in English). Logical formal reasons are responsible for adaptation of morphological irregularities (e. g. apart from monomorphic cheap people also coined the derivative inexpensive, especially popular in American English).

Joachism Grzega and Marion Schoner (Grzega, Schoner 2007) 20. 21. 22. Excessive length of words. An excessive length of a word can be the reason for lexical change if the word occurs frequently in the language (e. g. fax instead of telefax); this means that there is no general tendency to avoid long words. Morphological misinterpretation. This is an unconscious process of interpreting a meaningful senseful form into polysyllabic (and seemingly polymorphemic) words. We refer to the result of such process as folk-etymology (e. g. French contredanse was reinterpreted as country dance in English). Logical formal reasons are responsible for adaptation of morphological irregularities (e. g. apart from monomorphic cheap people also coined the derivative inexpensive, especially popular in American English).

Joachism Grzega and Marion Schoner (Grzega, Schoner 2007) 23. 24. Lack of motivation means that the word is less and less used because it is not motivated enough, i. e. there is no clear, visible motive and a more motivated synonym takes over and the use of the original words is restricted or becomes obsolete. Onomasiological analogy means that a certain phenomenon is modeled, or patterned, on another phenomenon. Concept A is no longer be expressed by x, but by x+1. In analogy to this, the related concept B is no longer be expressed by y, but by y+1 (e. g. shortly after Middle English spring was used to express ‘the season before the summer’, fall began to be used to denote ‘the season after the summer’ on the analogy of this. On a number of CDs we find the form outro instead of close—an obvious coinage on the analogy of intro (itself clipped from introduction).

Joachism Grzega and Marion Schoner (Grzega, Schoner 2007) 23. 24. Lack of motivation means that the word is less and less used because it is not motivated enough, i. e. there is no clear, visible motive and a more motivated synonym takes over and the use of the original words is restricted or becomes obsolete. Onomasiological analogy means that a certain phenomenon is modeled, or patterned, on another phenomenon. Concept A is no longer be expressed by x, but by x+1. In analogy to this, the related concept B is no longer be expressed by y, but by y+1 (e. g. shortly after Middle English spring was used to express ‘the season before the summer’, fall began to be used to denote ‘the season after the summer’ on the analogy of this. On a number of CDs we find the form outro instead of close—an obvious coinage on the analogy of intro (itself clipped from introduction).

Joachism Grzega and Marion Schoner (Grzega, Schoner 2007) 25. Secondary effects do not refer to a lexical change, but the change of the linguistic situation of a certain lexeme; such a change is caused by a related lexeme (e. g. the expressions to starve and to die were initially used as synonyms in the English language; through its close phonetic relation to the adjective dead, to die was preferred over to starve; when to die entered English from Old Norse, it was used more and more often and, as a secondary effect, to starve was used restrictedly for ‘to die of hunger’).

Joachism Grzega and Marion Schoner (Grzega, Schoner 2007) 25. Secondary effects do not refer to a lexical change, but the change of the linguistic situation of a certain lexeme; such a change is caused by a related lexeme (e. g. the expressions to starve and to die were initially used as synonyms in the English language; through its close phonetic relation to the adjective dead, to die was preferred over to starve; when to die entered English from Old Norse, it was used more and more often and, as a secondary effect, to starve was used restrictedly for ‘to die of hunger’).

Leonard Bloomfield, 1933. 1. 2. 3. 4. Narrowing: change from superordinate level to subordinate level (e. g. skyline used to refer to any horizon, but now it has narrowed to a horizon decorated by skyscrapers). Widening: change from subordinate level to superordinate level. There are many examples of specific brand names being used for the general product, such as with Kleenex). Metaphor: change based on similarity of thing (e. g. broadcast originally meant "to cast seeds out"; with the advent of radio and television, the word was extended to indicate the transmission of audio and video signals, outside of agricultural circles, very few people use broadcast in the earlier sense). Metonymy: change based on nearness in space or time (e. g. jaw ‘cheek’ ‘jaw’).

Leonard Bloomfield, 1933. 1. 2. 3. 4. Narrowing: change from superordinate level to subordinate level (e. g. skyline used to refer to any horizon, but now it has narrowed to a horizon decorated by skyscrapers). Widening: change from subordinate level to superordinate level. There are many examples of specific brand names being used for the general product, such as with Kleenex). Metaphor: change based on similarity of thing (e. g. broadcast originally meant "to cast seeds out"; with the advent of radio and television, the word was extended to indicate the transmission of audio and video signals, outside of agricultural circles, very few people use broadcast in the earlier sense). Metonymy: change based on nearness in space or time (e. g. jaw ‘cheek’ ‘jaw’).

Leonard Bloomfield, 1933. 5. 6. 7. 8. 9. Synecdoche: change based on whole-part relation; the convention of using capital cities to represent countries or their governments is an example of this. Hyperbole: change from stronger to weaker meaning (e. g. astound ‘strike with thunder’ ’surprise strongly’). Litotes: change from weaker to stronger meaning (e. g. kill ‘torment’ ’kill’. Degeneration: the acquisition by the word of some derogative emotional charge (e. g. knave ‘boy’ ’servant’. Elevation: the improvement of the connotational component (e. g. knight ‘boy’ ‘knight’).

Leonard Bloomfield, 1933. 5. 6. 7. 8. 9. Synecdoche: change based on whole-part relation; the convention of using capital cities to represent countries or their governments is an example of this. Hyperbole: change from stronger to weaker meaning (e. g. astound ‘strike with thunder’ ’surprise strongly’). Litotes: change from weaker to stronger meaning (e. g. kill ‘torment’ ’kill’. Degeneration: the acquisition by the word of some derogative emotional charge (e. g. knave ‘boy’ ’servant’. Elevation: the improvement of the connotational component (e. g. knight ‘boy’ ‘knight’).

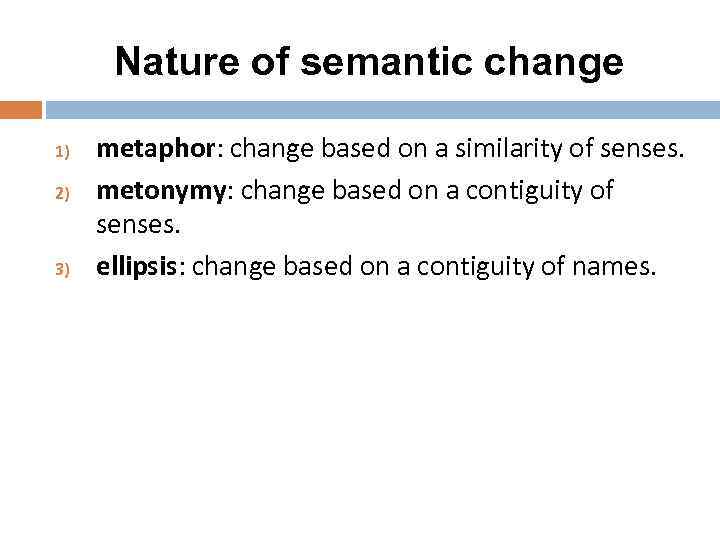

Nature of semantic change 1) 2) 3) metaphor: change based on a similarity of senses. metonymy: change based on a contiguity of senses. ellipsis: change based on a contiguity of names.

Nature of semantic change 1) 2) 3) metaphor: change based on a similarity of senses. metonymy: change based on a contiguity of senses. ellipsis: change based on a contiguity of names.

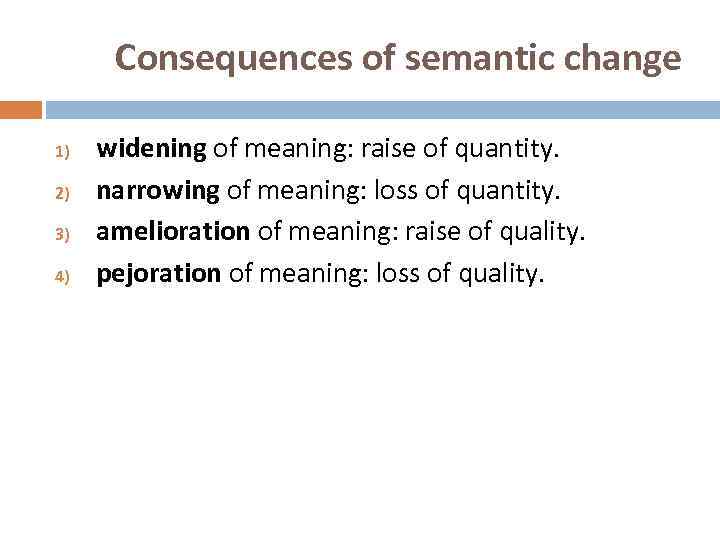

Consequences of semantic change 1) 2) 3) 4) widening of meaning: raise of quantity. narrowing of meaning: loss of quantity. amelioration of meaning: raise of quality. pejoration of meaning: loss of quality.

Consequences of semantic change 1) 2) 3) 4) widening of meaning: raise of quantity. narrowing of meaning: loss of quantity. amelioration of meaning: raise of quality. pejoration of meaning: loss of quality.

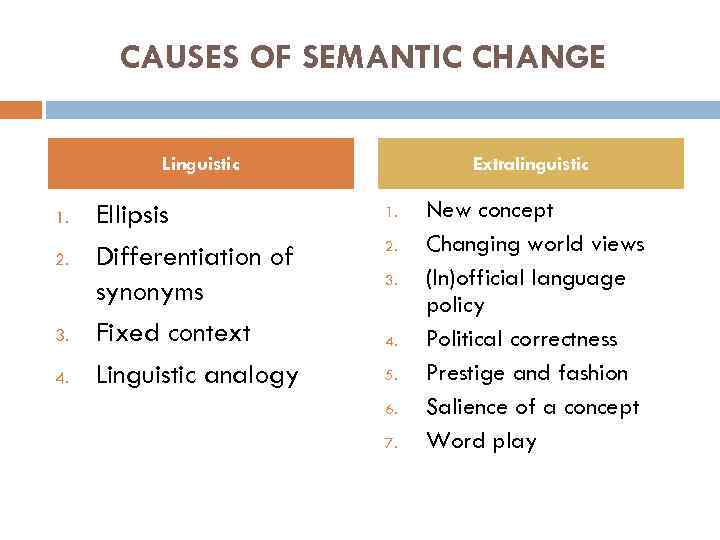

CAUSES OF SEMANTIC CHANGE Linguistic 1. 2. 3. 4. Ellipsis Differentiation of synonyms Fixed context Linguistic analogy Extralinguistic 1. 2. 3. 4. 5. 6. 7. New concept Changing world views (In)official language policy Political correctness Prestige and fashion Salience of a concept Word play

CAUSES OF SEMANTIC CHANGE Linguistic 1. 2. 3. 4. Ellipsis Differentiation of synonyms Fixed context Linguistic analogy Extralinguistic 1. 2. 3. 4. 5. 6. 7. New concept Changing world views (In)official language policy Political correctness Prestige and fashion Salience of a concept Word play

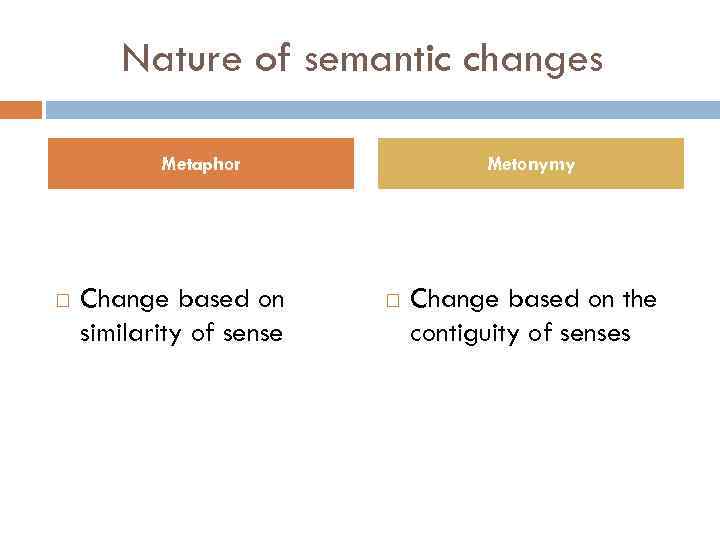

Nature of semantic changes Metaphor Change based on similarity of sense Metonymy Change based on the contiguity of senses

Nature of semantic changes Metaphor Change based on similarity of sense Metonymy Change based on the contiguity of senses

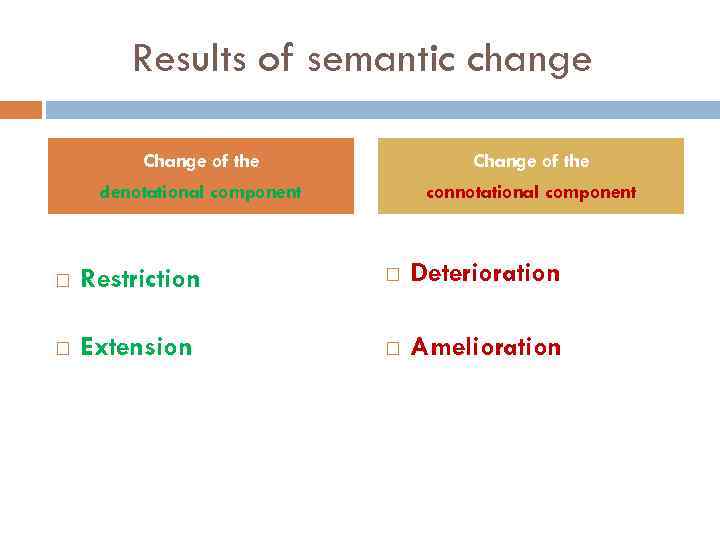

Results of semantic change Change of the denotational component connotational component Restriction Deterioration Extension Amelioration

Results of semantic change Change of the denotational component connotational component Restriction Deterioration Extension Amelioration

Causes, nature and results of semantic changes should be viewed as three essentially different but inseparable aspects of one and the same linguistic phenomenon as a change of meaning may be investigated from the point of view of its cause, nature and its consequences.

Causes, nature and results of semantic changes should be viewed as three essentially different but inseparable aspects of one and the same linguistic phenomenon as a change of meaning may be investigated from the point of view of its cause, nature and its consequences.