Seismic Attribute Mapping of Structure and Stratigraphy Unit

Seismic Attribute Mapping of Structure and Stratigraphy Unit 2: Spectral Decomposition

Course Outline Introduction Basic concepts Multiattribute display Spectral decomposition Geometric attributes Dip and azimuth Coherence Curvature and reflector shape Lateral changes in amplitude and pattern recognition Attributes and the seismic interpreter Structural deformation Clastic environments Carbonate environments Shallow stratigraphy and drilling hazards Reservoir heterogeneity Attributes and the seismic processor Influence of acquisition and processing Structure-oriented filtering and image enhancement Prestack geometric attributes

2. Spectral Decomposition After this section you will be able to: Identify the geological features highlighted by spectral decomposition and wavelet transforms, Interpret spectral anomalies in the context of thin bed tuning, Analyze singularities of seismic data for structural and stratigraphic details, and Evaluate the use of spectral information as a direct hydrocarbon indicator.

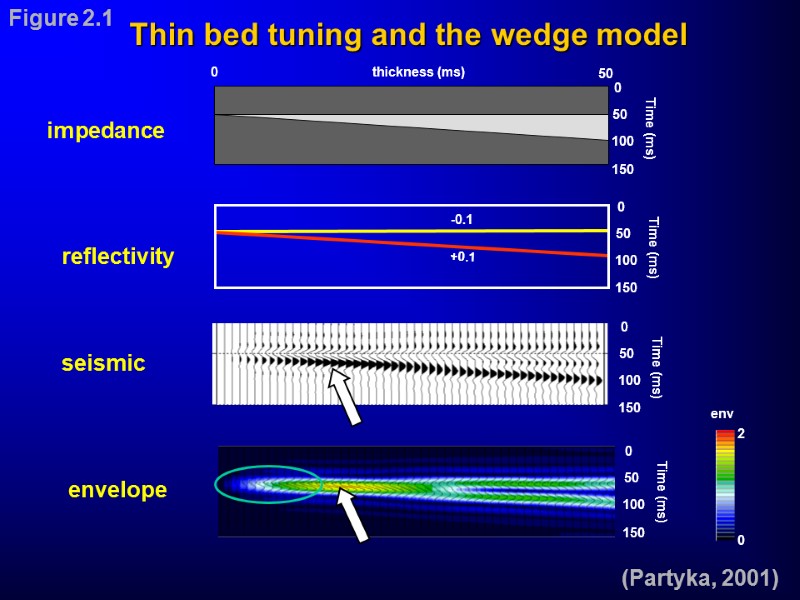

(Partyka, 2001) Figure 2.1 Thin bed tuning and the wedge model

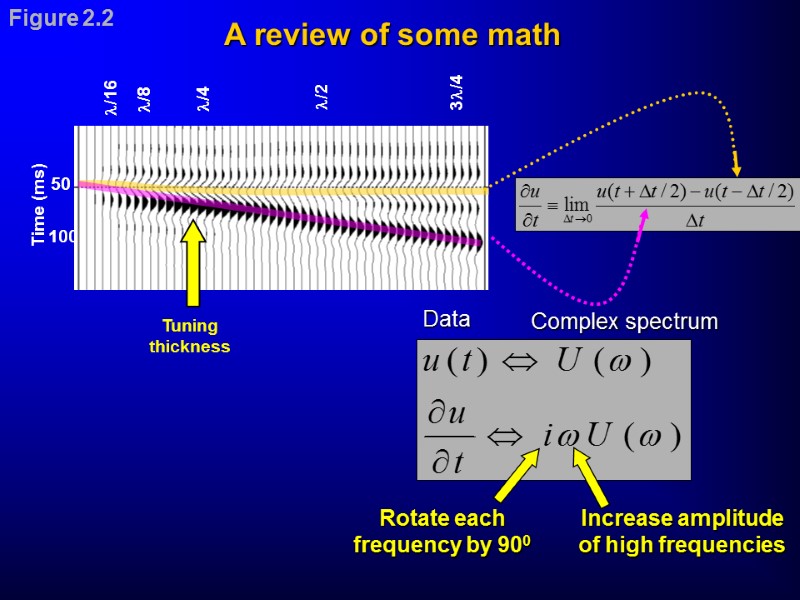

A review of some math Figure 2.2 /4 /8 /16 /2 3/4 50 100 Time (ms) Tuning thickness

Alternative Basis Functions

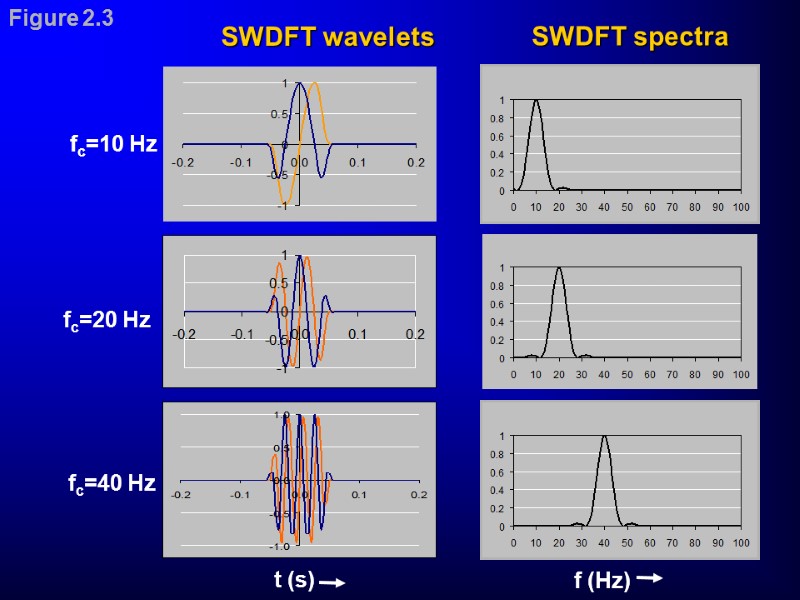

fc=10 Hz fc=20 Hz fc=40 Hz SWDFT wavelets SWDFT spectra Figure 2.3

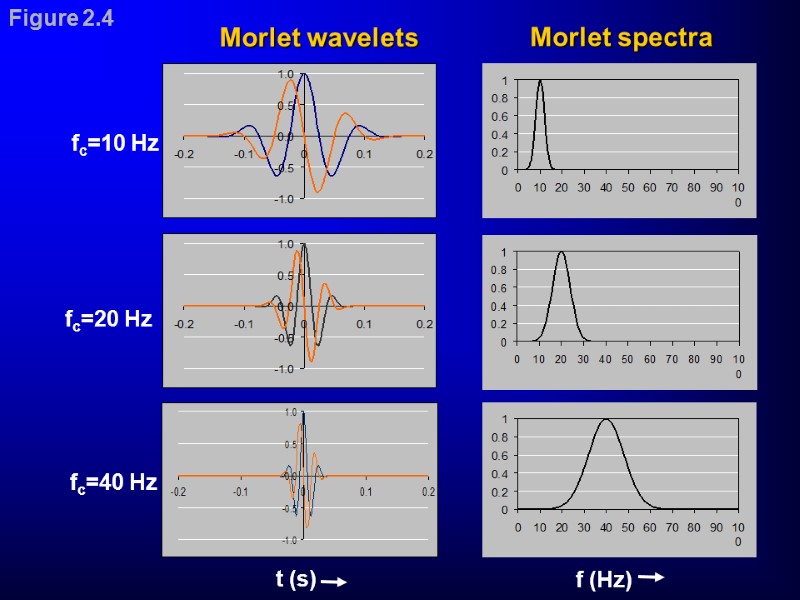

Morlet wavelets Morlet spectra fc=10 Hz fc=20 Hz fc=40 Hz Figure 2.4

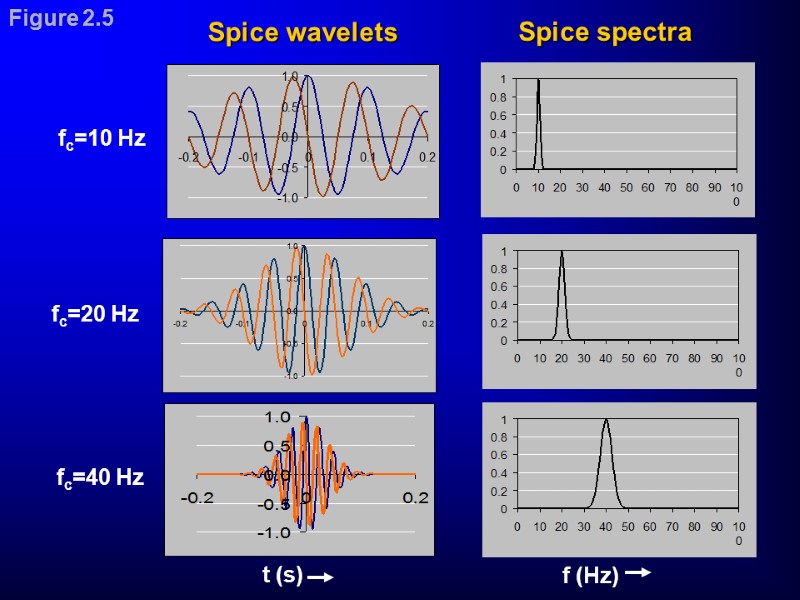

Spice wavelets fc=10 Hz fc=20 Hz fc=40 Hz Spice spectra Figure 2.5

Spectral Decomposition using the Short Window Discrete Fourier Transform (SWDFT)

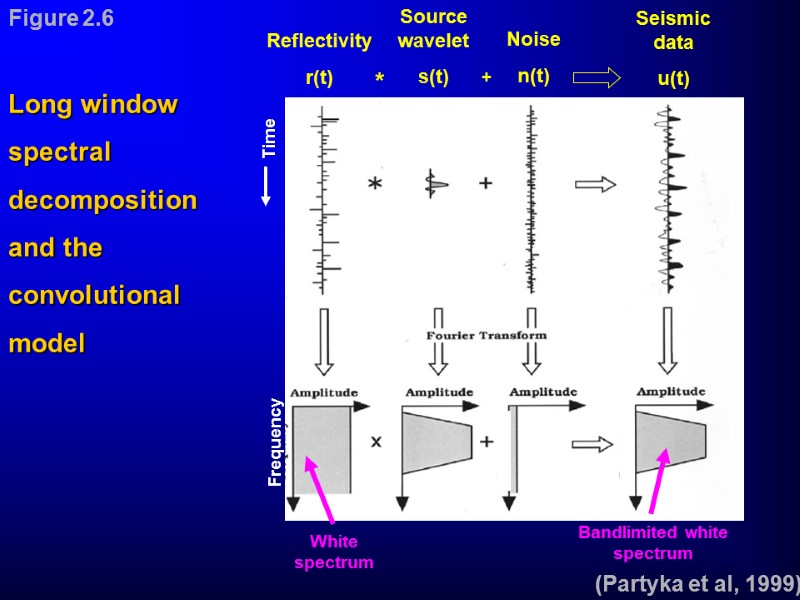

Time Frequency Reflectivity r(t) Source wavelet s(t) Noise n(t) Seismic data u(t) * + Bandlimited white spectrum (Partyka et al, 1999) Long window spectral decomposition and the convolutional model White spectrum Figure 2.6

![Figure 2.7 Spectral balancing a(f) Multiply by 1./[a(f) +amax] Figure 2.7 Spectral balancing a(f) Multiply by 1./[a(f) +amax]](https://present5.com/presentacii-2/20171208\6704-marfurt_k._2_-_spec_decomp.ppt\6704-marfurt_k_2_-_spec_decomp_12.jpg)

Figure 2.7 Spectral balancing a(f) Multiply by 1./[a(f) +amax]

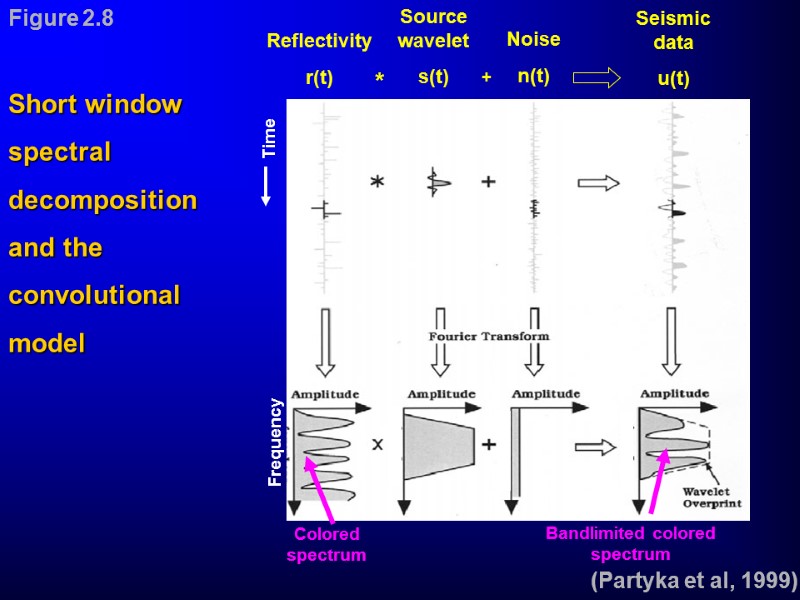

Colored spectrum Time Frequency Reflectivity r(t) Source wavelet s(t) Noise n(t) Seismic data u(t) * + Bandlimited colored spectrum (Partyka et al, 1999) Short window spectral decomposition and the convolutional model Figure 2.8

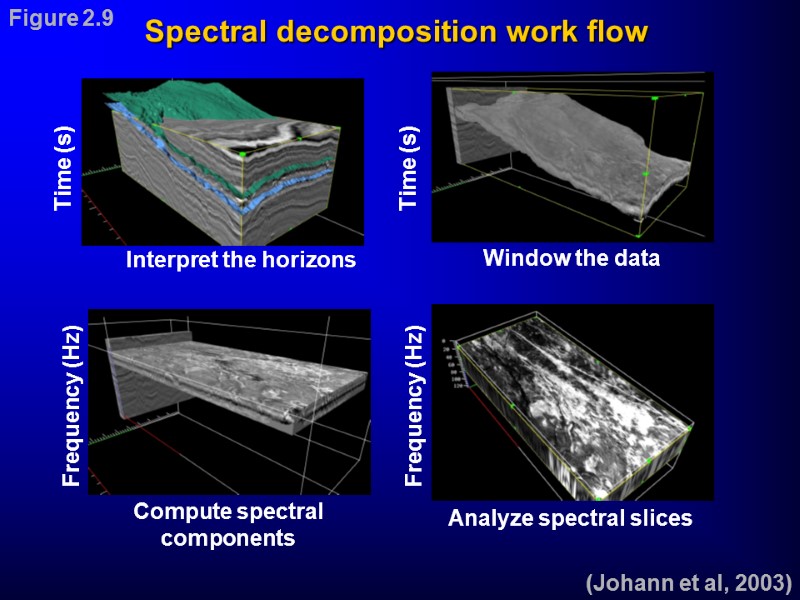

(Johann et al, 2003) Spectral decomposition work flow Figure 2.9 Time (s) Frequency (Hz) Time (s) Frequency (Hz) Compute spectral components Analyze spectral slices Window the data Interpret the horizons

Sensitivity of the Spectral Components to Formation Thickness

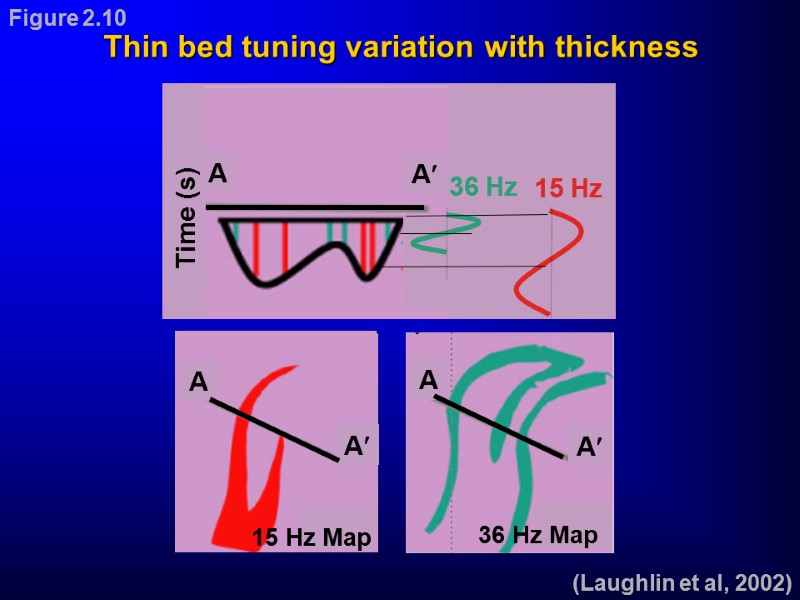

(Laughlin et al, 2002) Thin bed tuning variation with thickness Figure 2.10

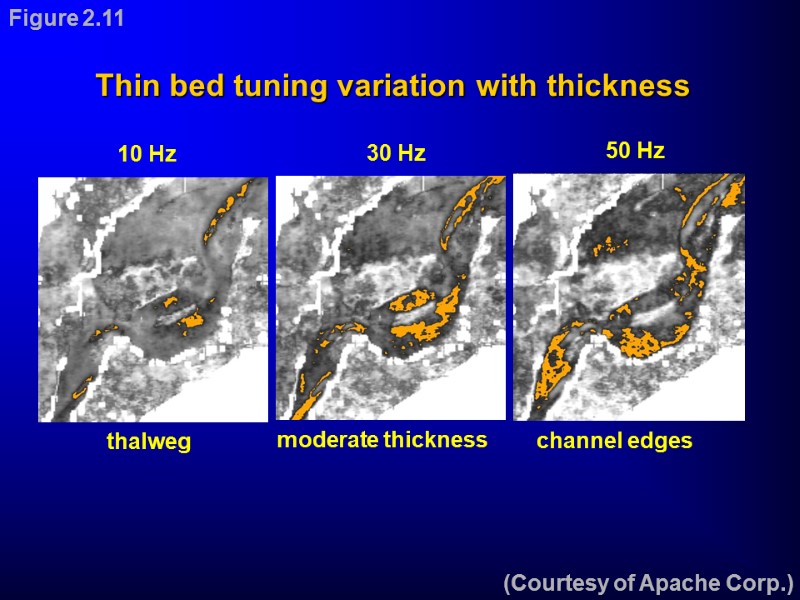

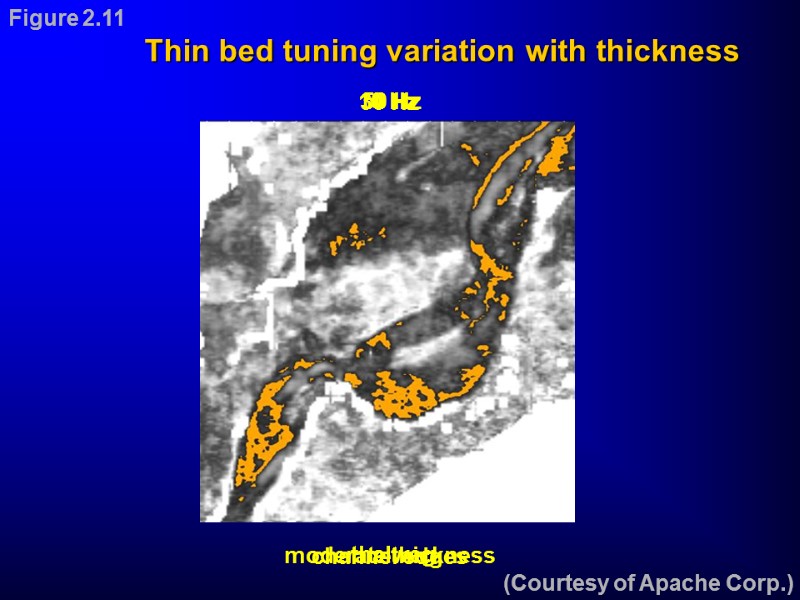

(Courtesy of Apache Corp.) Thin bed tuning variation with thickness Figure 2.11

(Courtesy of Apache Corp.) Thin bed tuning variation with thickness Figure 2.11

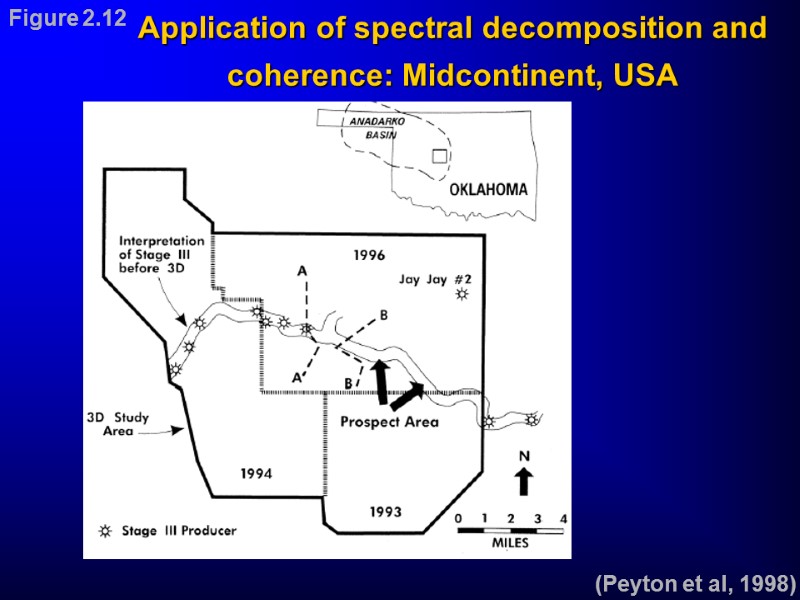

(Peyton et al, 1998) Application of spectral decomposition and coherence: Midcontinent, USA Figure 2.12

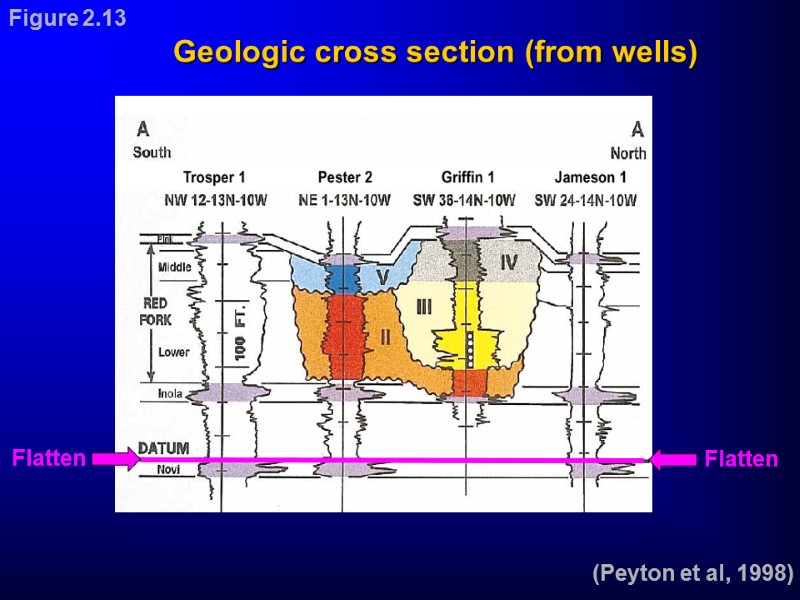

(Peyton et al, 1998) Figure 2.13 Geologic cross section (from wells) Flatten Flatten

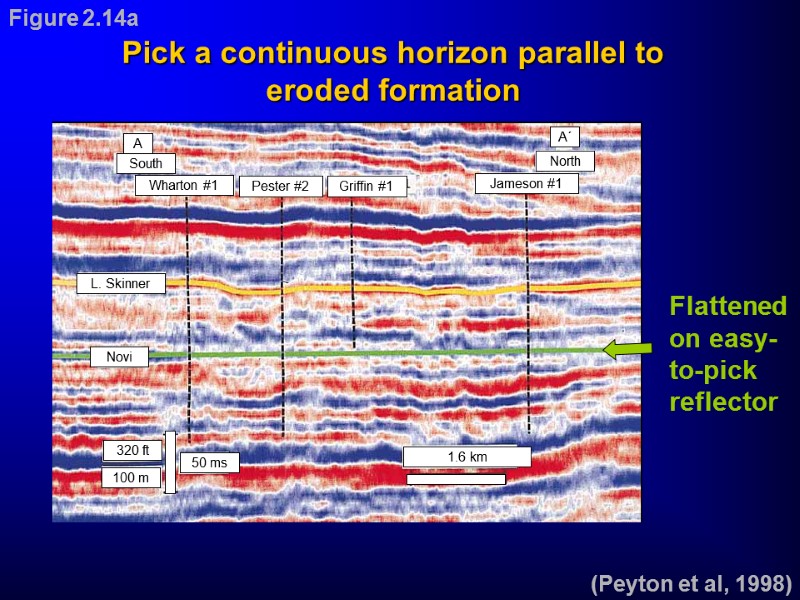

Figure 2.14a

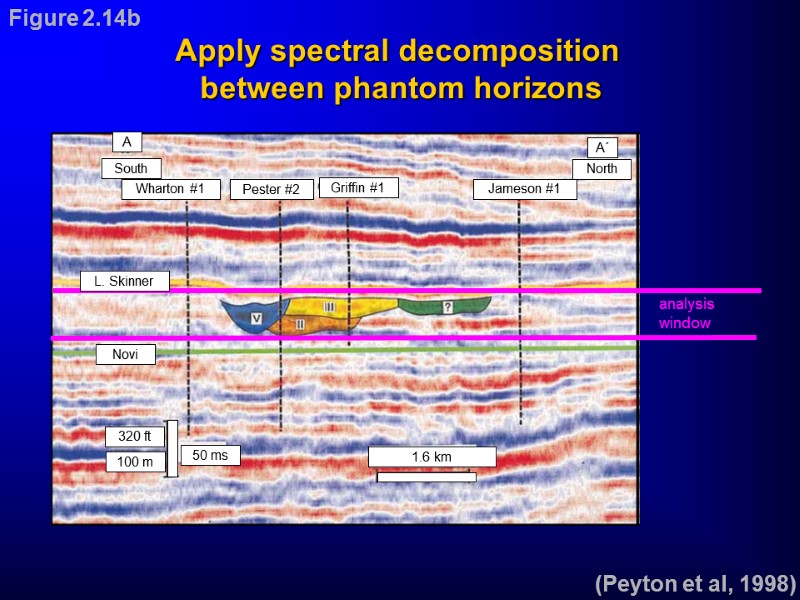

(Peyton et al, 1998) Apply spectral decomposition between phantom horizons Figure 2.14b

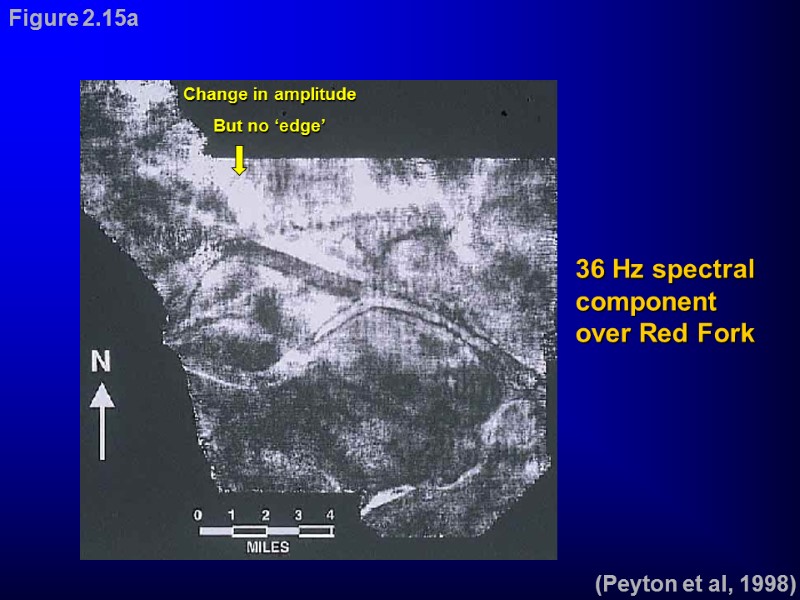

(Peyton et al, 1998) 36 Hz spectral component over Red Fork Figure 2.15a

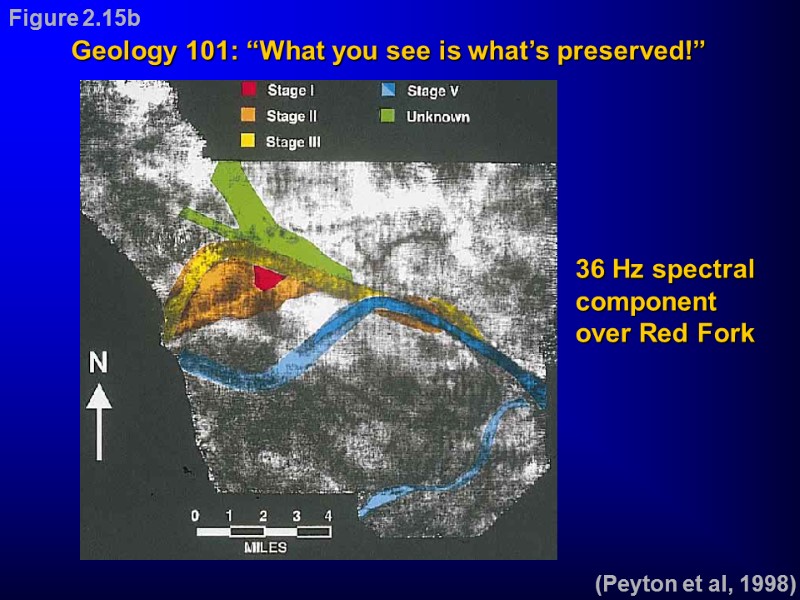

(Peyton et al, 1998) Geology 101: “What you see is what’s preserved!” Figure 2.15b 36 Hz spectral component over Red Fork

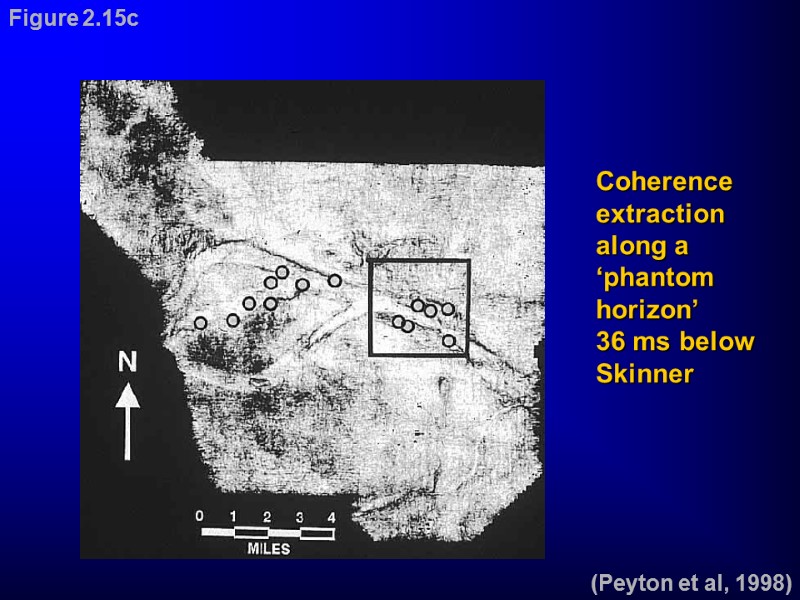

(Peyton et al, 1998) Coherence extraction along a ‘phantom horizon’ 36 ms below Skinner Figure 2.15c

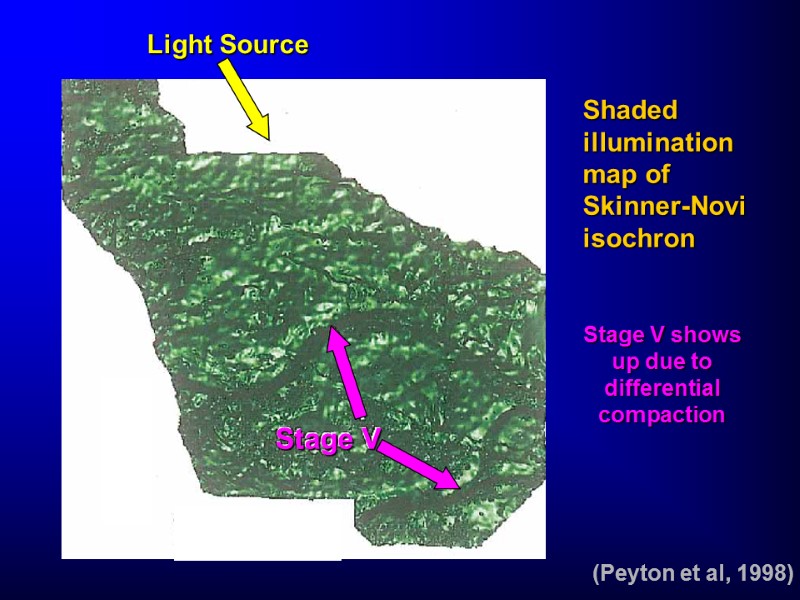

(Peyton et al, 1998) Light Source Shaded illumination map of Skinner-Novi isochron Stage V Stage V shows up due to differential compaction

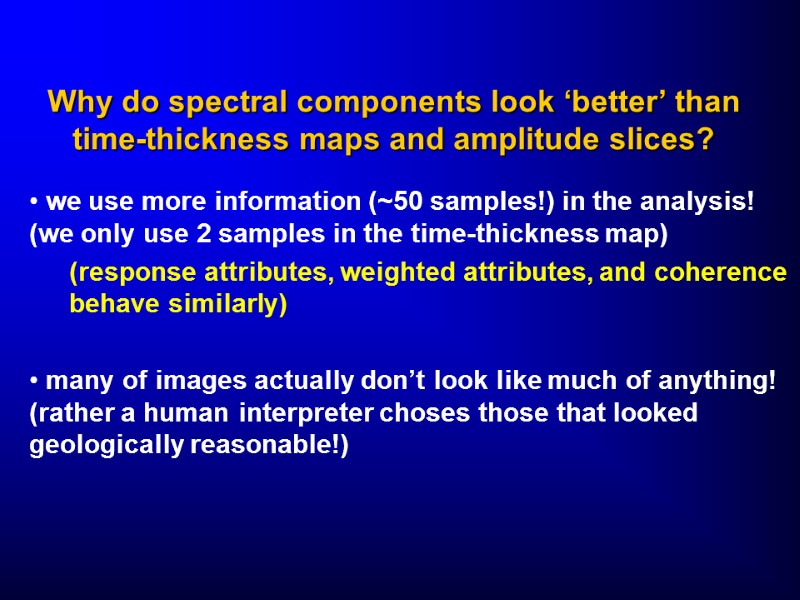

Why do spectral components look ‘better’ than time-thickness maps and amplitude slices? we use more information (~50 samples!) in the analysis! (we only use 2 samples in the time-thickness map) (response attributes, weighted attributes, and coherence behave similarly) many of images actually don’t look like much of anything! (rather a human interpreter choses those that looked geologically reasonable!)

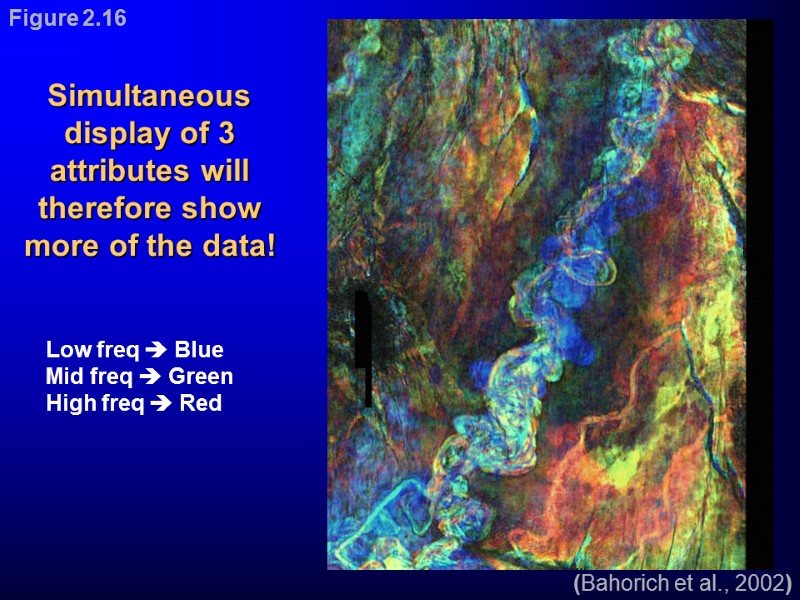

Simultaneous display of 3 attributes will therefore show more of the data! Figure 2.16 (Bahorich et al., 2002) Low freq Blue Mid freq Green High freq Red

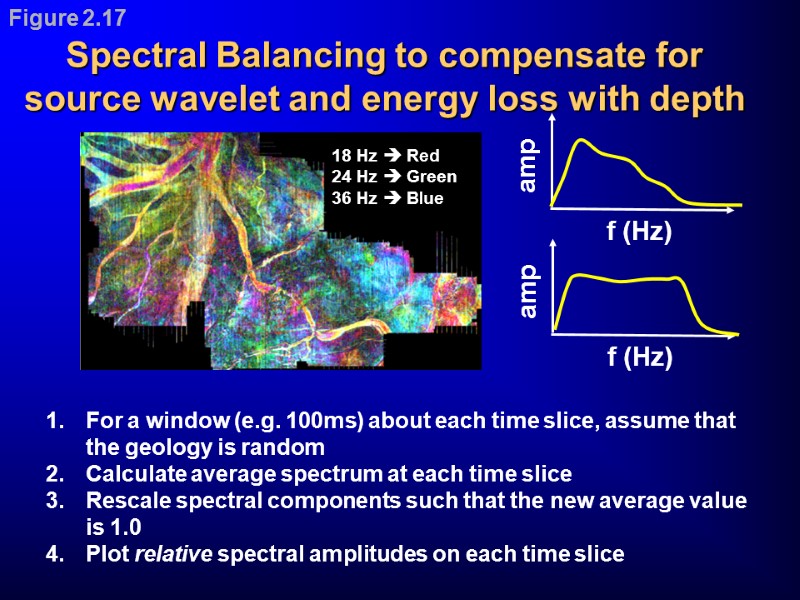

Spectral Balancing to compensate for source wavelet and energy loss with depth For a window (e.g. 100ms) about each time slice, assume that the geology is random Calculate average spectrum at each time slice Rescale spectral components such that the new average value is 1.0 Plot relative spectral amplitudes on each time slice 18 Hz Red 24 Hz Green 36 Hz Blue Figure 2.17

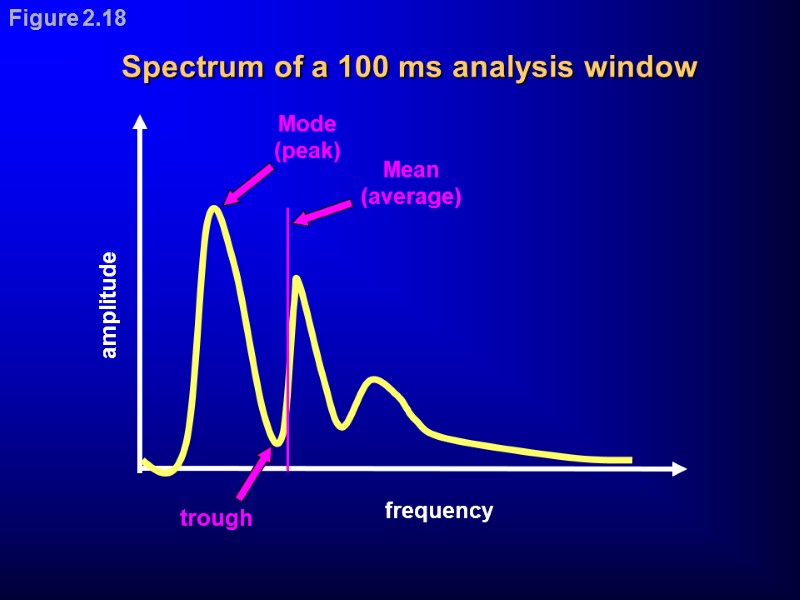

Mode (peak) frequency amplitude Mean (average) Spectrum of a 100 ms analysis window trough Figure 2.18

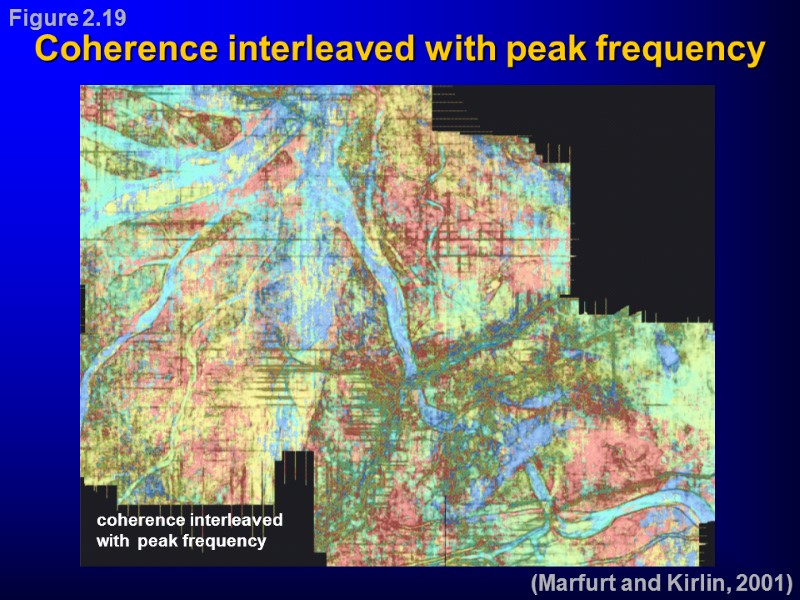

Coherence interleaved with peak frequency (Marfurt and Kirlin, 2001) Figure 2.19

Spectral Decomposition using Wavelet Transforms

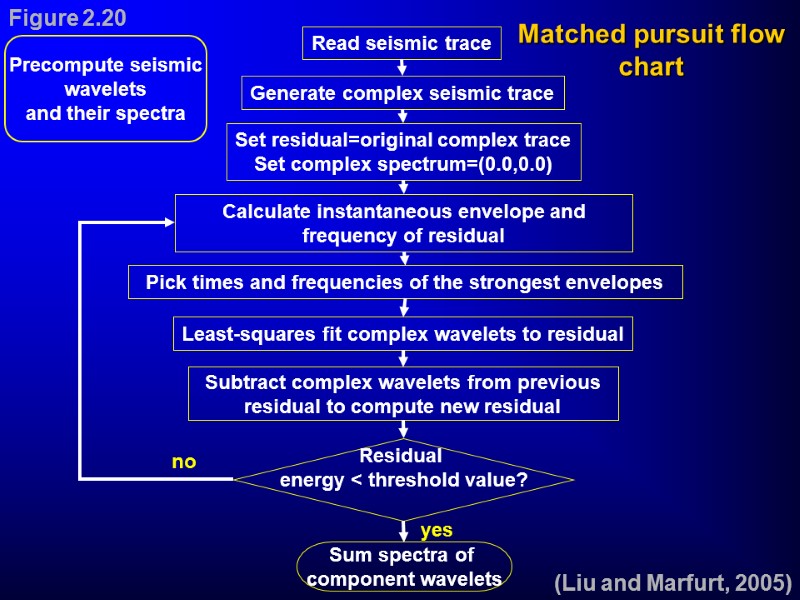

Matched pursuit flow chart (Liu and Marfurt, 2005) Precompute seismic wavelets and their spectra Figure 2.20

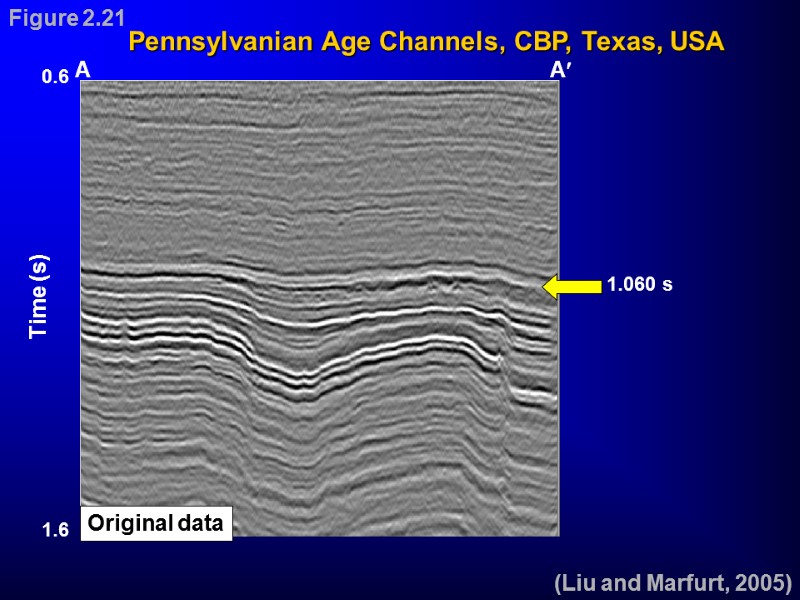

1.060 s Pennsylvanian Age Channels, CBP, Texas, USA A A (Liu and Marfurt, 2005) Figure 2.21

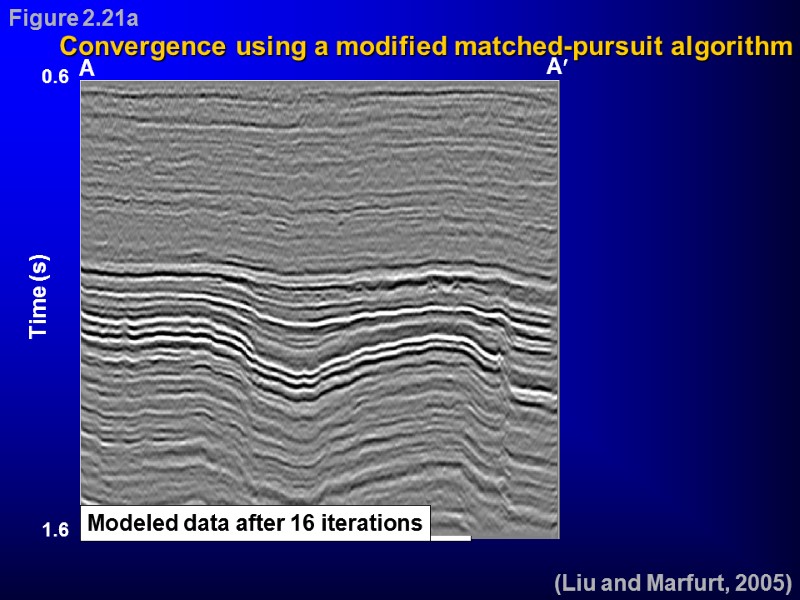

Convergence using a modified matched-pursuit algorithm A A (Liu and Marfurt, 2005) Figure 2.21a

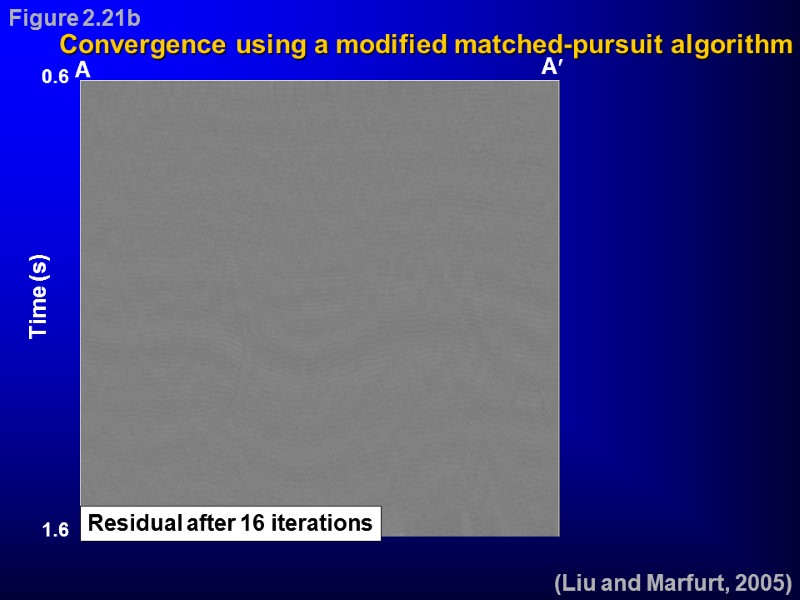

Convergence using a modified matched-pursuit algorithm A A (Liu and Marfurt, 2005) Figure 2.21b

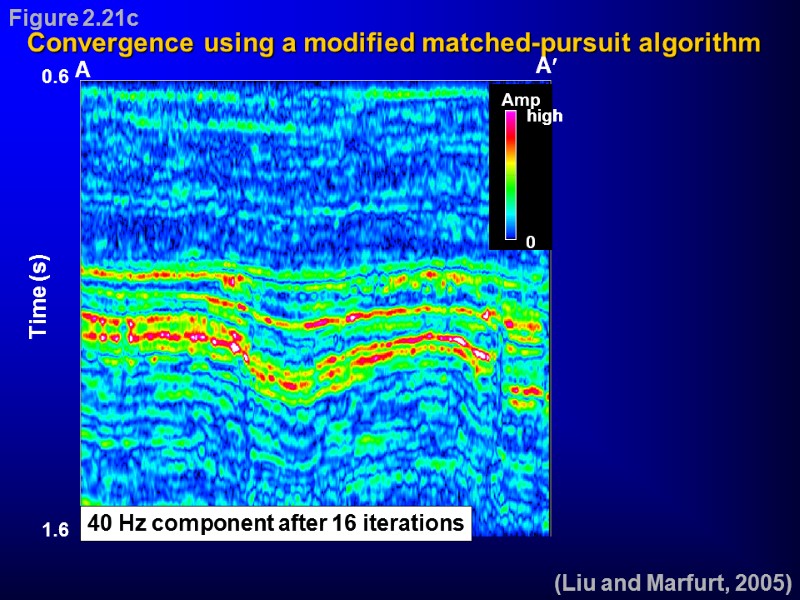

Convergence using a modified matched-pursuit algorithm A A (Liu and Marfurt, 2005) Figure 2.21c

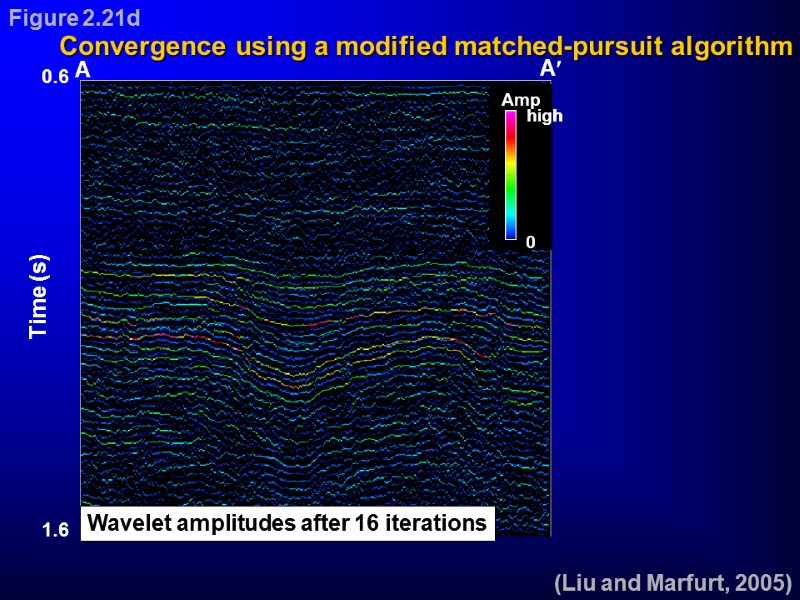

Convergence using a modified matched-pursuit algorithm A A (Liu and Marfurt, 2005) Figure 2.21d

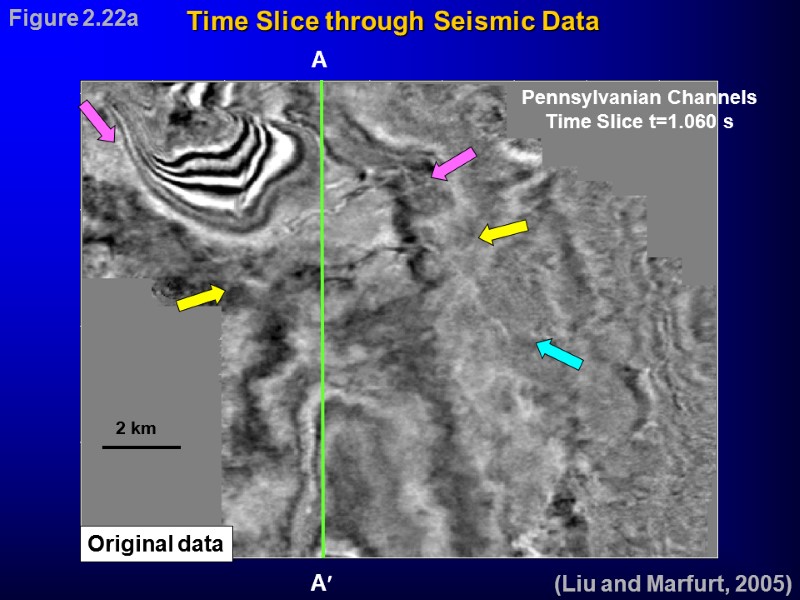

(Liu and Marfurt, 2005) Figure 2.22a Pennsylvanian Channels Time Slice t=1.060 s A A Time Slice through Seismic Data

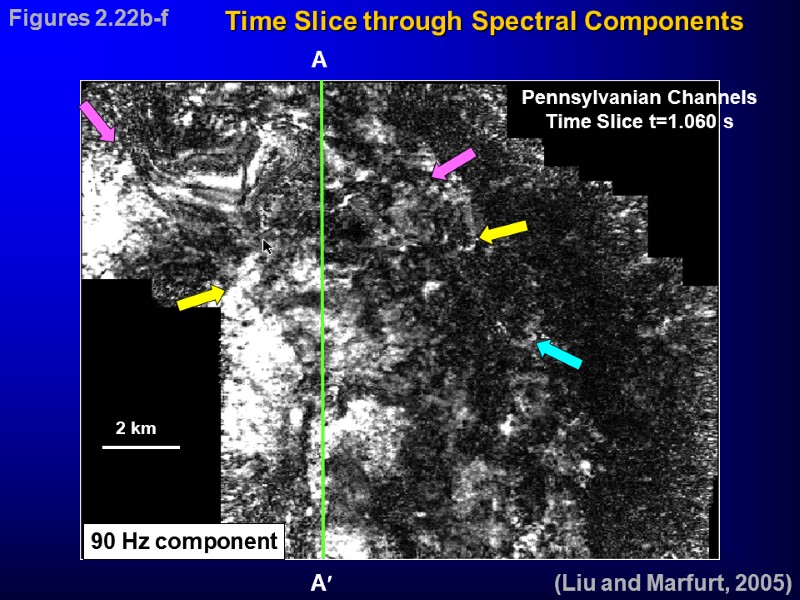

(Liu and Marfurt, 2005) Figures 2.22b-f Time Slice through Spectral Components

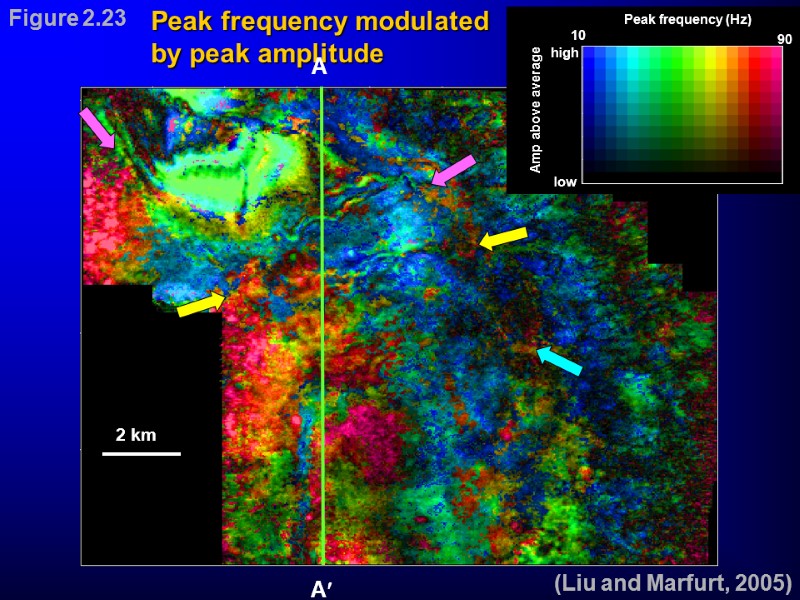

Peak frequency modulated by peak amplitude (Liu and Marfurt, 2005) Figure 2.23 A A

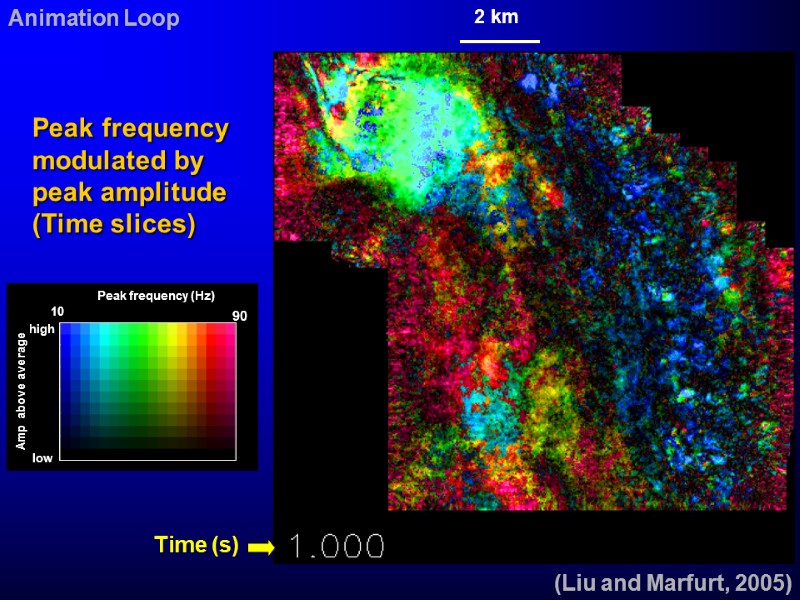

Time (s) (Liu and Marfurt, 2005) Animation Loop Peak frequency modulated by peak amplitude (Time slices)

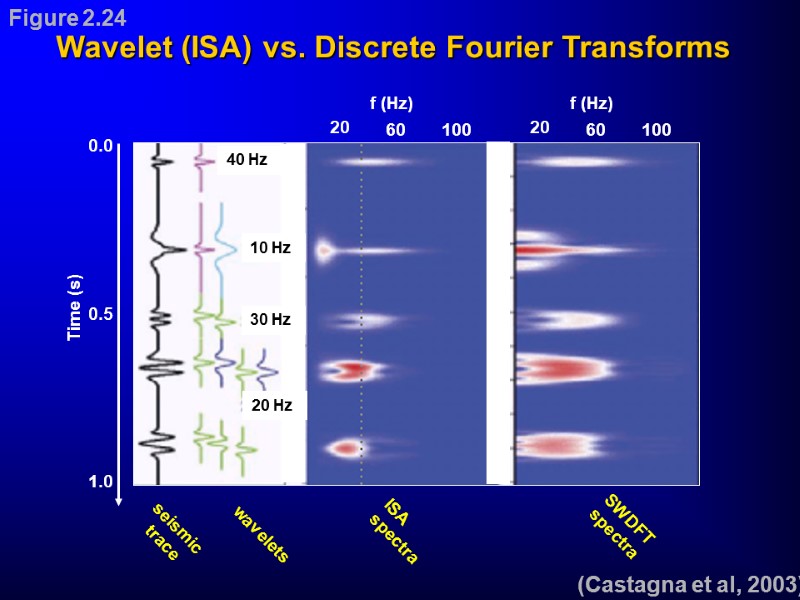

Wavelet (ISA) vs. Discrete Fourier Transforms (Castagna et al, 2003) Figure 2.24

Sensitivity of Spectral Components to Hydrocarbons

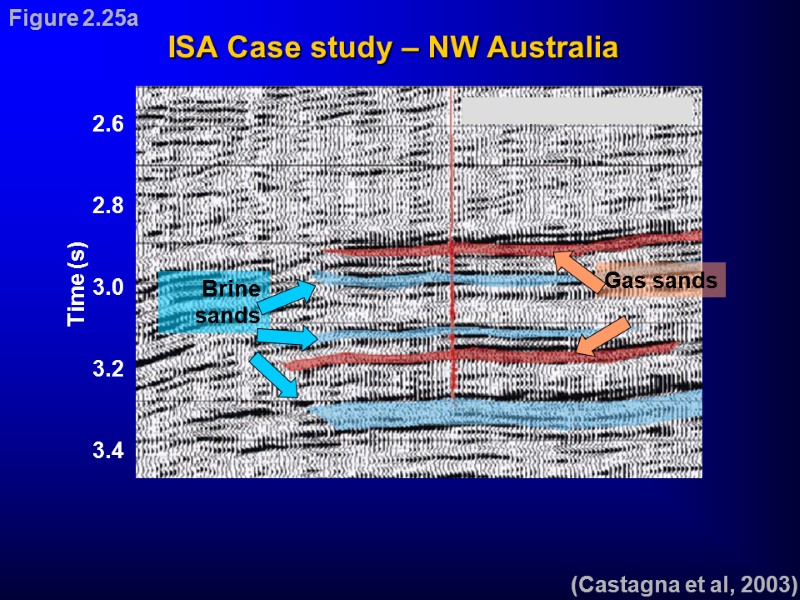

ISA Case study – NW Australia (Castagna et al, 2003) Figure 2.25a

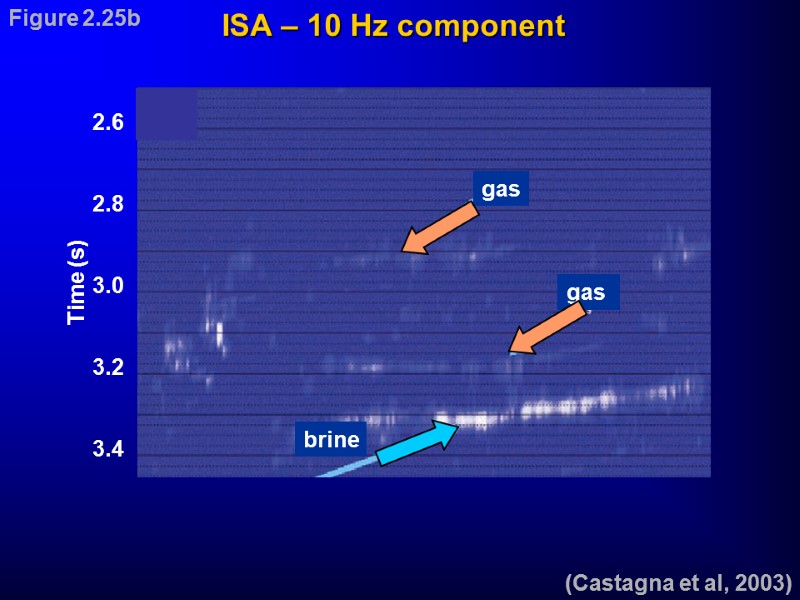

ISA – 10 Hz component (Castagna et al, 2003) Figure 2.25b

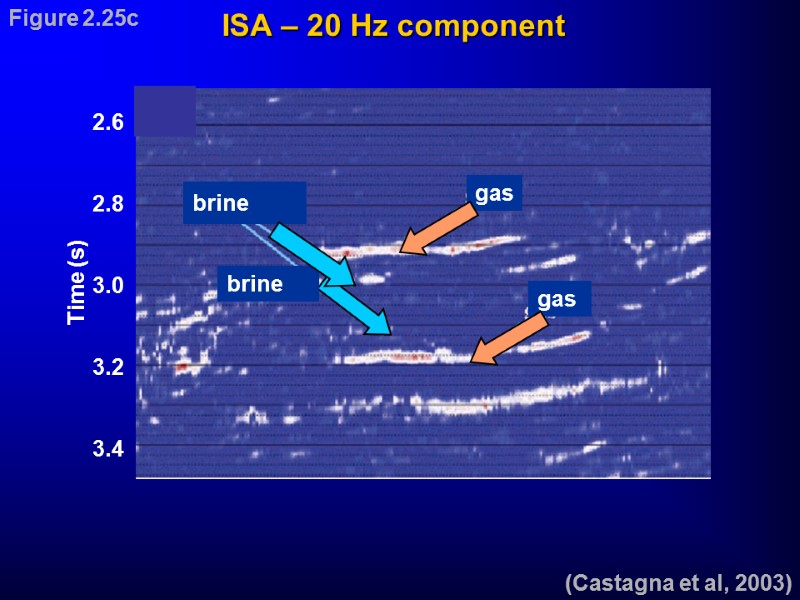

ISA – 20 Hz component (Castagna et al, 2003) Figure 2.25c

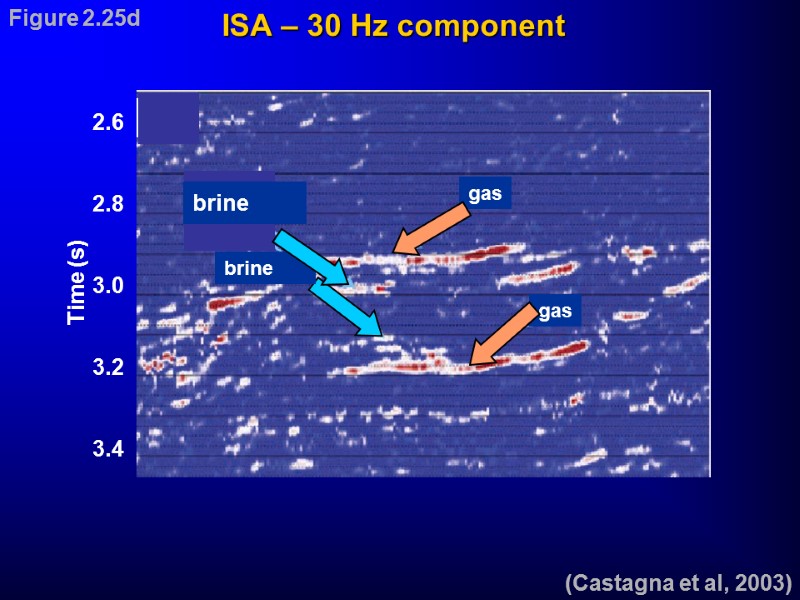

ISA – 30 Hz component (Castagna et al, 2003) Figure 2.25d brine

Sensitivity of the Low Frequency Part of the Spectrum to Hydrocarbons

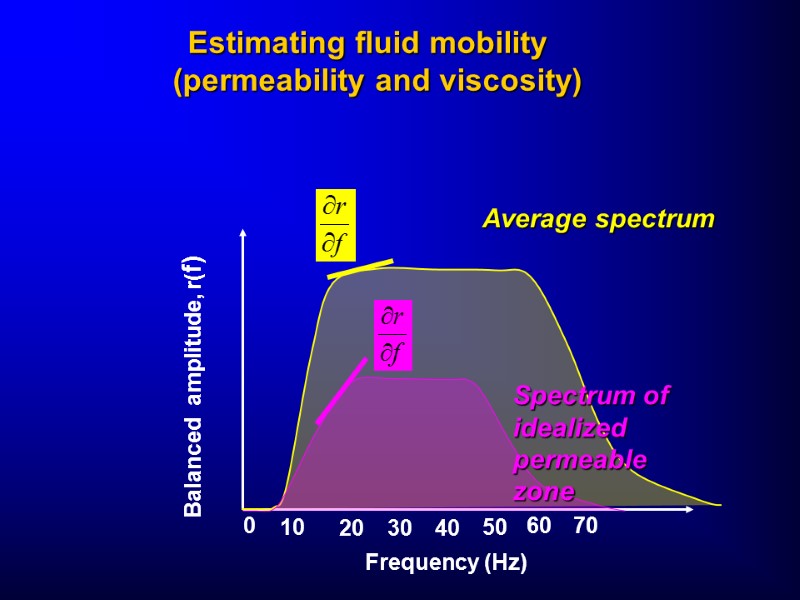

Frequency (Hz) Balanced amplitude, r(f) Estimating fluid mobility (permeability and viscosity) 0 10 30 20 40 60 50 70 Average spectrum

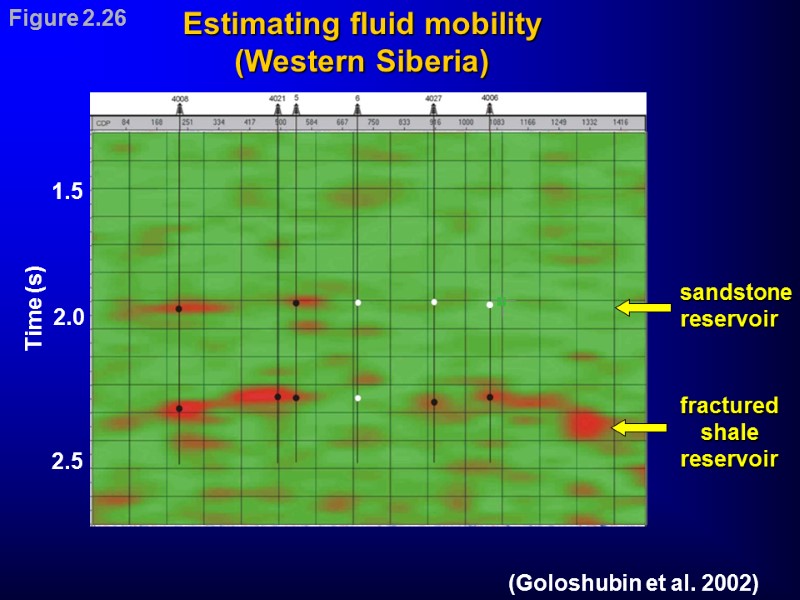

Estimating fluid mobility (Western Siberia) (Goloshubin et al. 2002) Figure 2.26 1.5 2.5 Time (s) 2.0 sandstone reservoir fractured shale reservoir

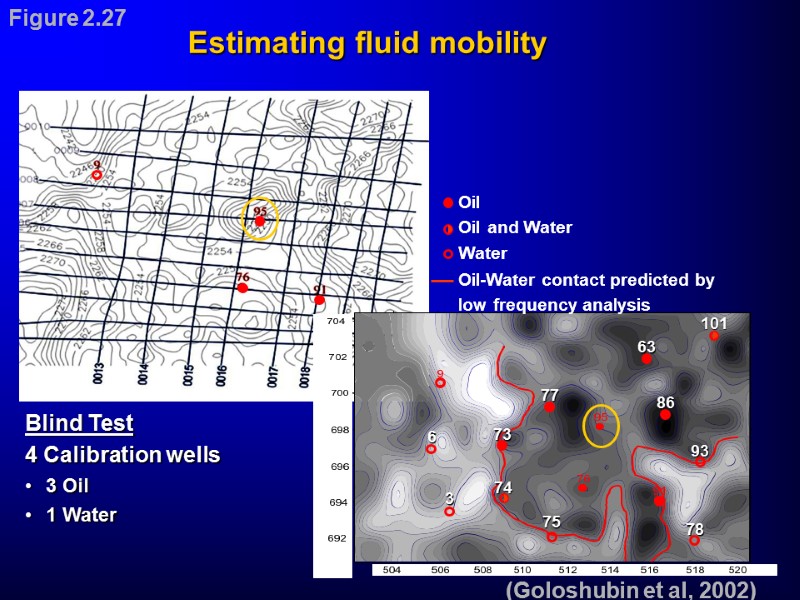

Oil Oil and Water Water Blind Test 4 Calibration wells 3 Oil 1 Water (Goloshubin et al, 2002) Figure 2.27 Estimating fluid mobility

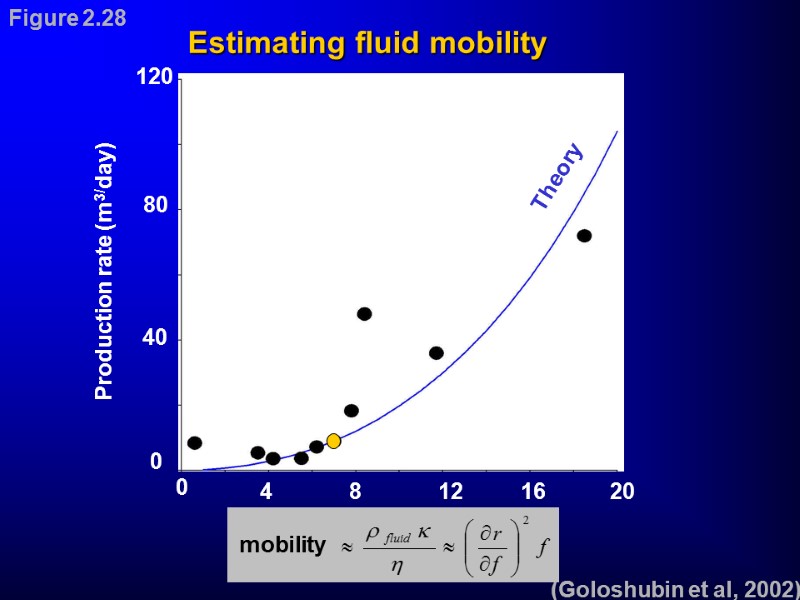

(Goloshubin et al, 2002) Figure 2.28 Estimating fluid mobility

Exploiting Waveform Singularities (the SPICE Algorithm)

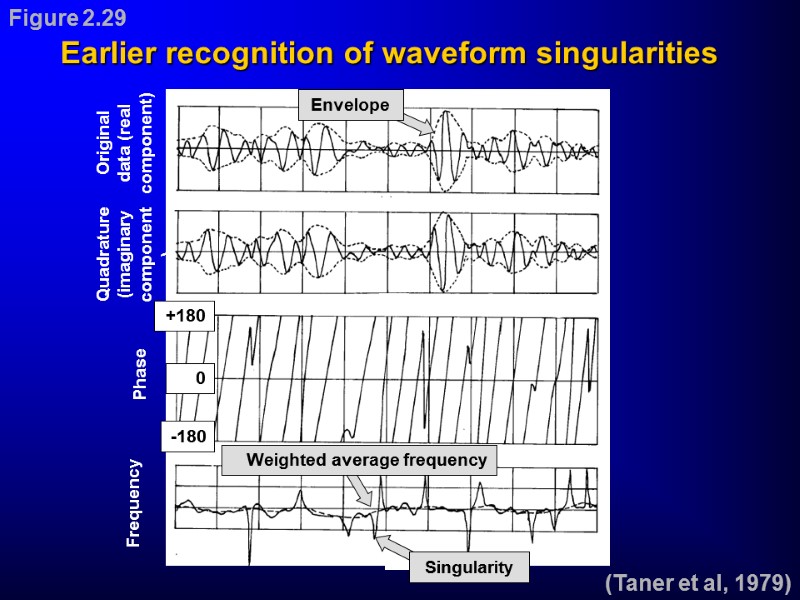

(Taner et al, 1979) Figure 2.29 Earlier recognition of waveform singularities

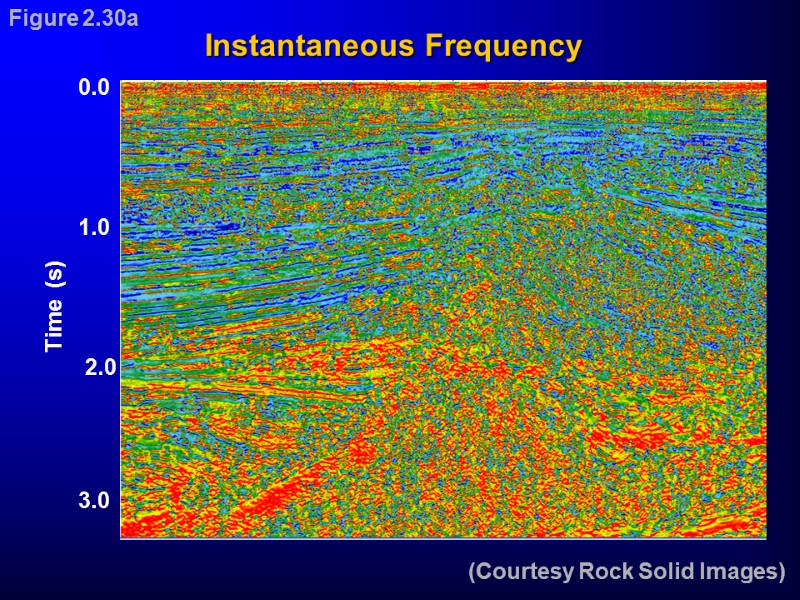

Instantaneous Frequency (Courtesy Rock Solid Images) Figure 2.30a

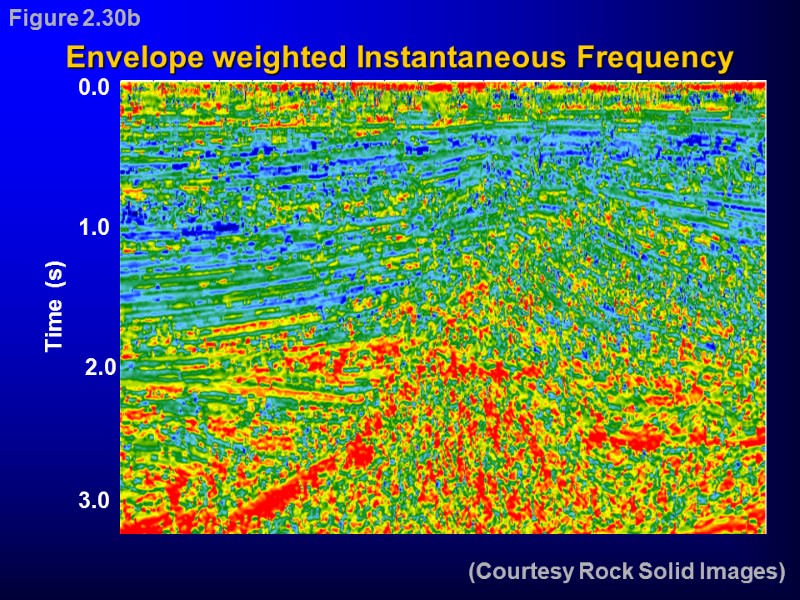

Envelope weighted Instantaneous Frequency (Courtesy Rock Solid Images) Figure 2.30b

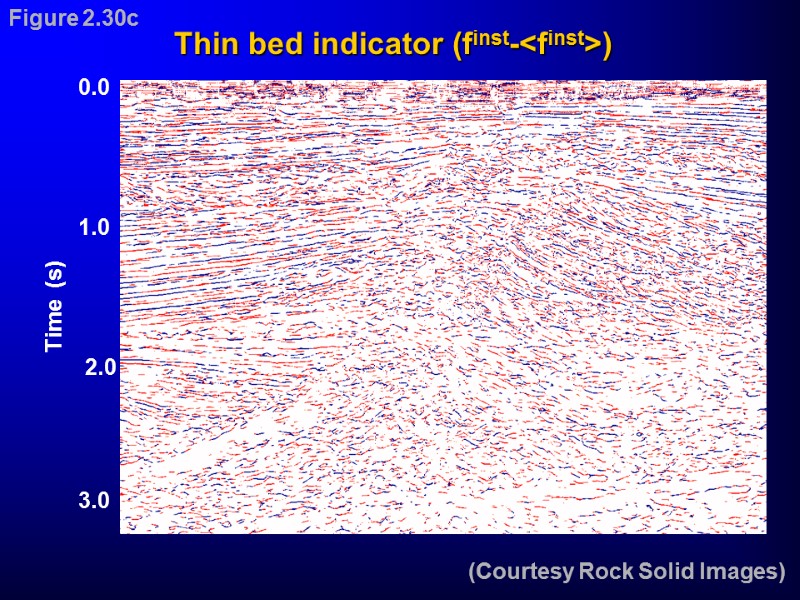

Thin bed indicator (finst-

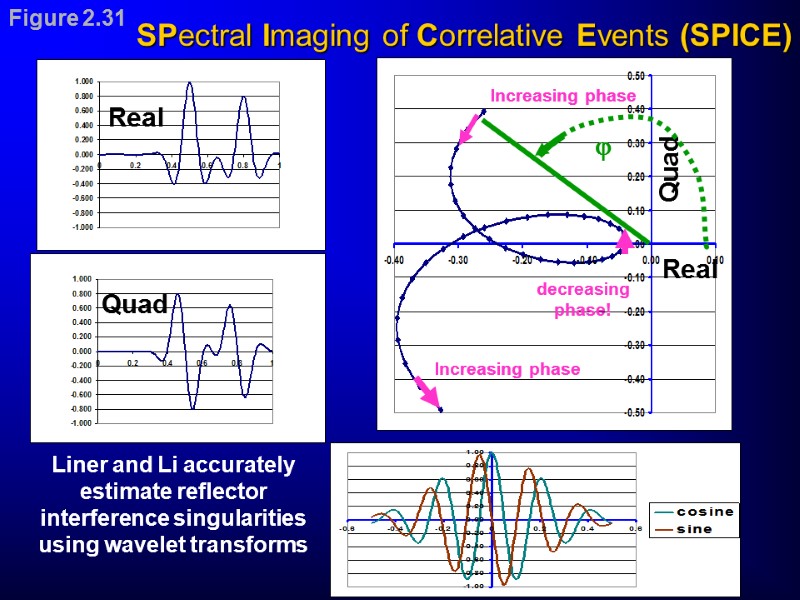

SPectral Imaging of Correlative Events (SPICE) Quad Liner and Li accurately estimate reflector interference singularities using wavelet transforms Real Figure 2.31

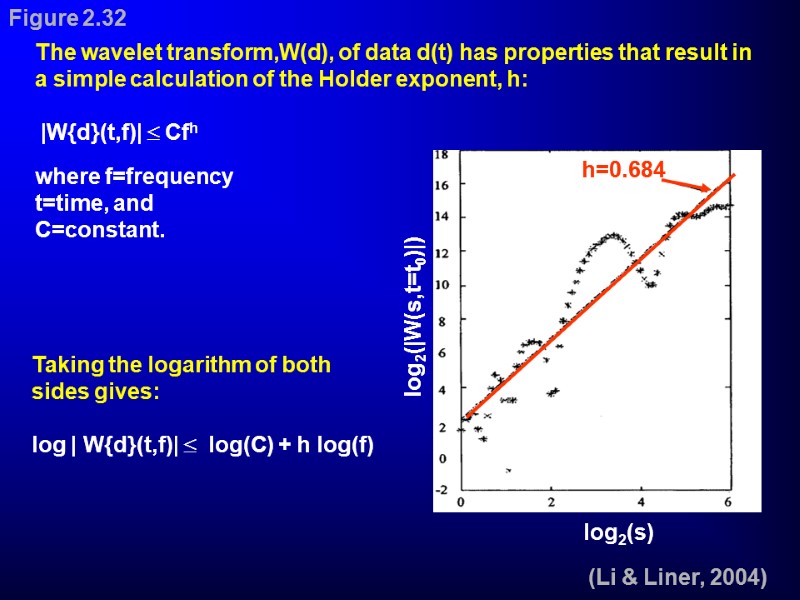

The wavelet transform,W(d), of data d(t) has properties that result in a simple calculation of the Holder exponent, h: |W{d}(t,f)| Cfh where f=frequency t=time, and C=constant. Taking the logarithm of both sides gives: log | W{d}(t,f)| log(C) + h log(f) (Li & Liner, 2004) Figure 2.32

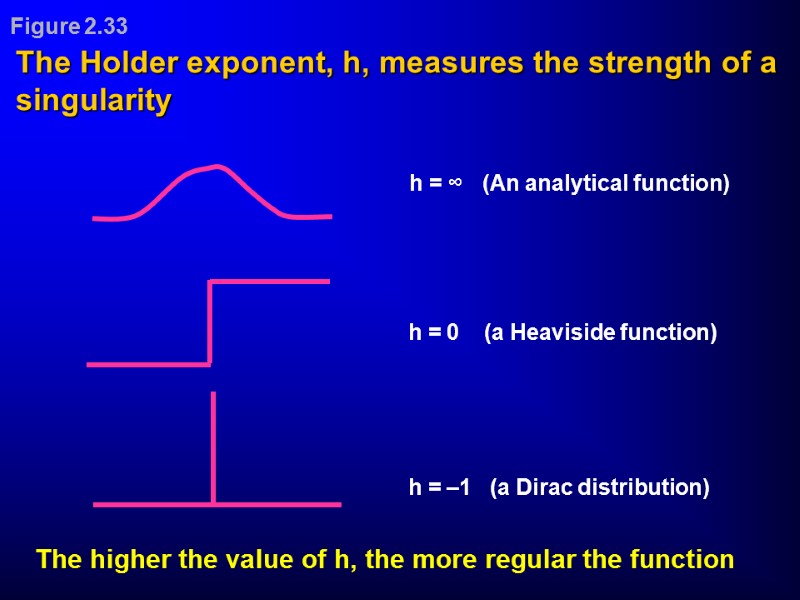

h = 0 (a Heaviside function) h = –1 (a Dirac distribution) The higher the value of h, the more regular the function h = ∞ (An analytical function) The Holder exponent, h, measures the strength of a singularity Figure 2.33

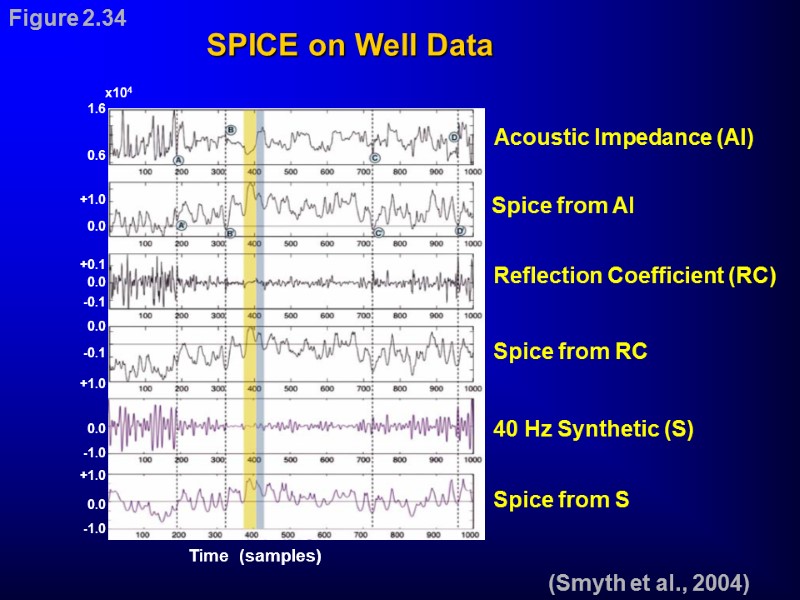

Acoustic Impedance (AI) Spice from AI Reflection Coefficient (RC) Spice from RC 40 Hz Synthetic (S) Spice from S Time (samples) -1.0 0.0 0.0 +1.0 0.6 1.6 x104 0.0 +0.1 -0.1 +1.0 -1.0 0.0 +1.0 0.0 -0.1 SPICE on Well Data (Smyth et al., 2004) Figure 2.34

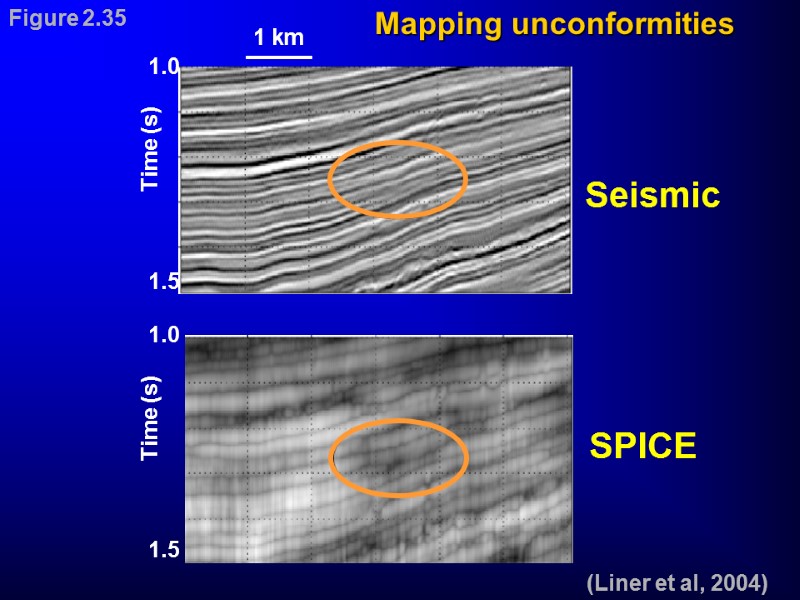

(Liner et al, 2004) Figure 2.35 SPICE Seismic Mapping unconformities

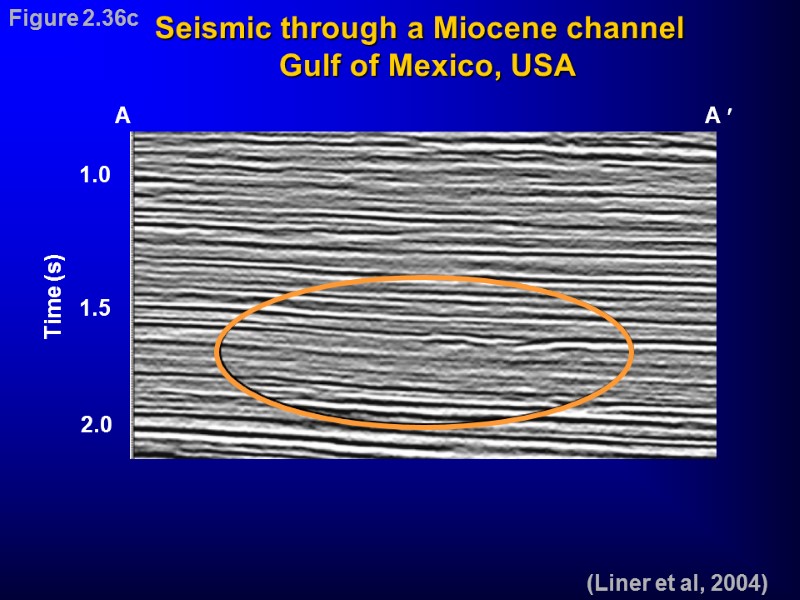

(Liner et al, 2004) Seismic through a Miocene channel Gulf of Mexico, USA Figure 2.36c

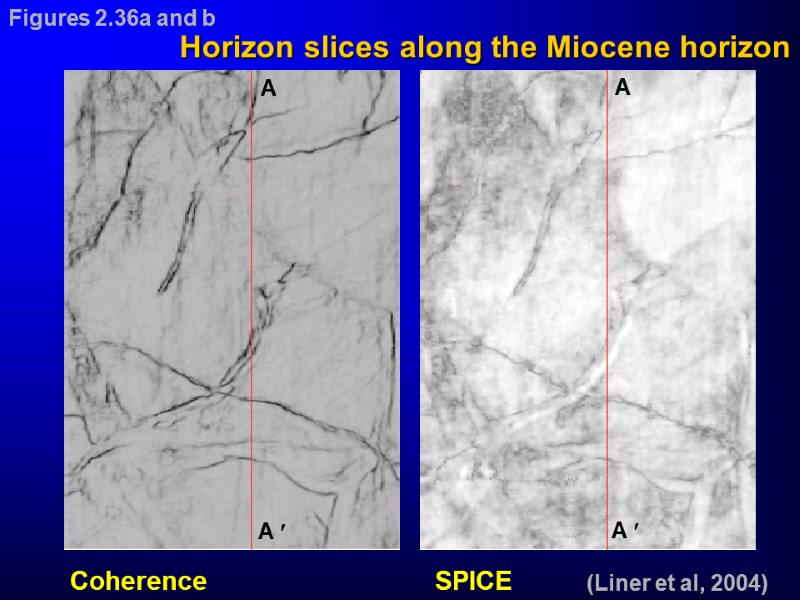

(Liner et al, 2004) Coherence SPICE Horizon slices along the Miocene horizon Figures 2.36a and b A A A A

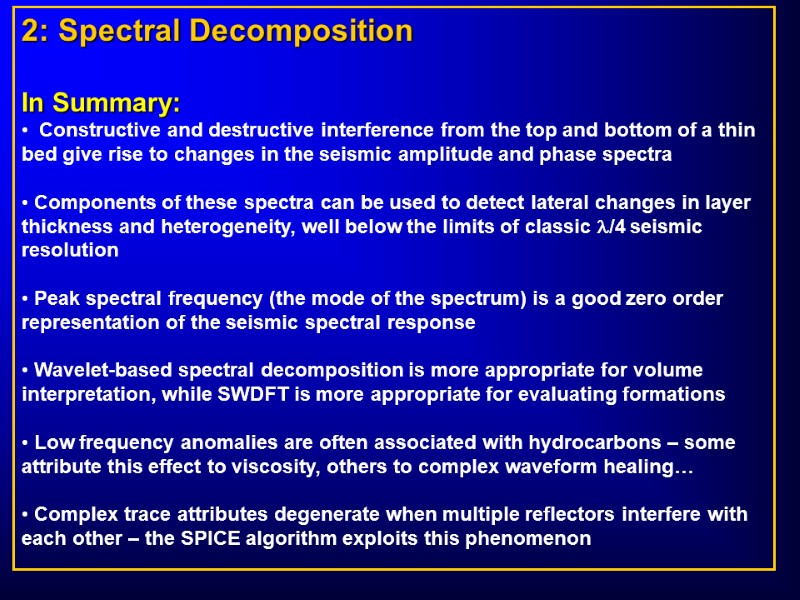

2: Spectral Decomposition In Summary: Constructive and destructive interference from the top and bottom of a thin bed give rise to changes in the seismic amplitude and phase spectra Components of these spectra can be used to detect lateral changes in layer thickness and heterogeneity, well below the limits of classic /4 seismic resolution Peak spectral frequency (the mode of the spectrum) is a good zero order representation of the seismic spectral response Wavelet-based spectral decomposition is more appropriate for volume interpretation, while SWDFT is more appropriate for evaluating formations Low frequency anomalies are often associated with hydrocarbons – some attribute this effect to viscosity, others to complex waveform healing… Complex trace attributes degenerate when multiple reflectors interfere with each other – the SPICE algorithm exploits this phenomenon

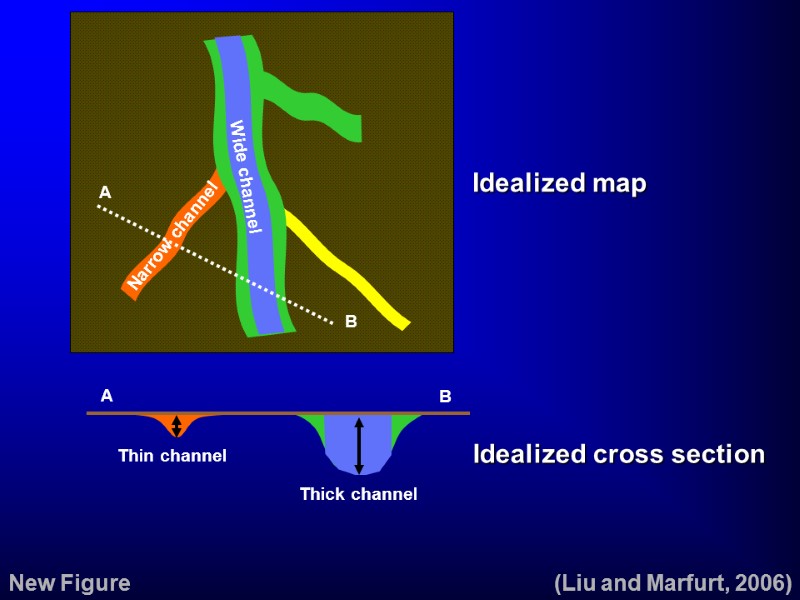

Narrow channel A B Wide channel Idealized map Idealized cross section (Liu and Marfurt, 2006) New Figure

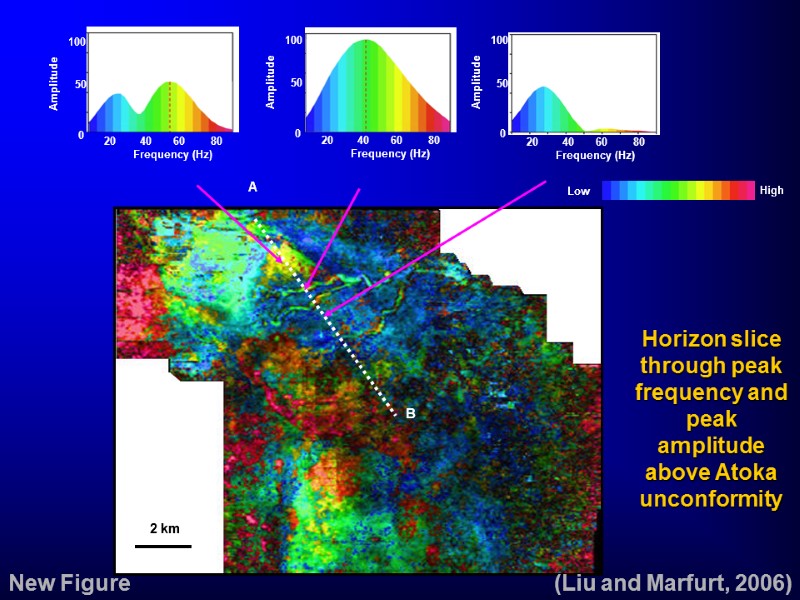

Horizon slice through peak frequency and peak amplitude above Atoka unconformity (Liu and Marfurt, 2006) New Figure

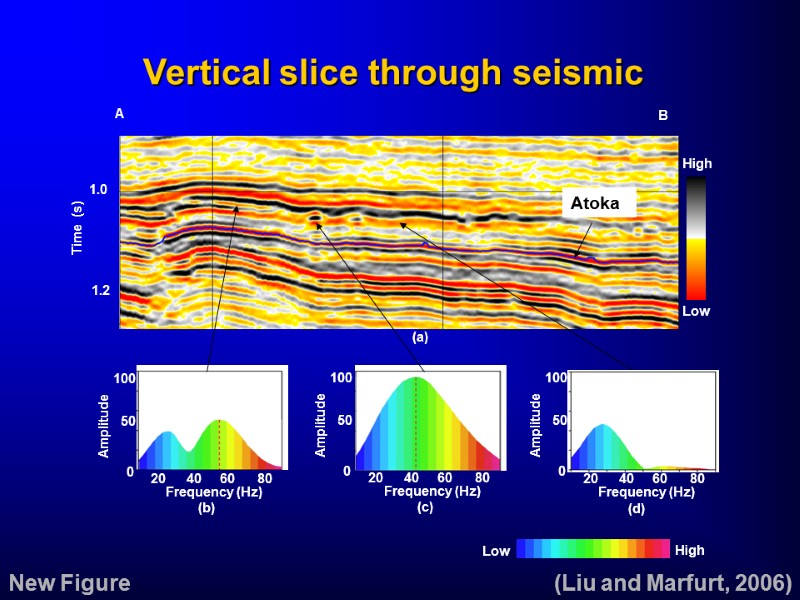

Vertical slice through seismic (Liu and Marfurt, 2006) New Figure

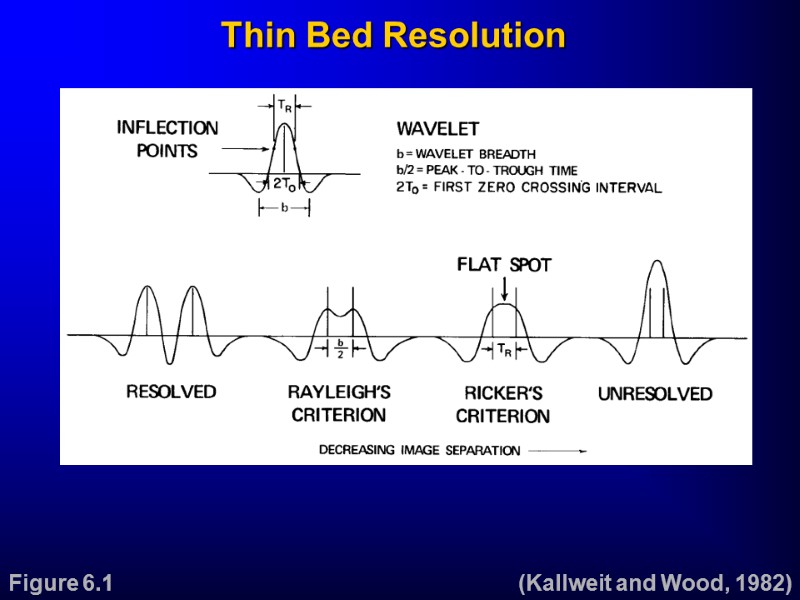

Thin Bed Resolution (Kallweit and Wood, 1982) Figure 6.1

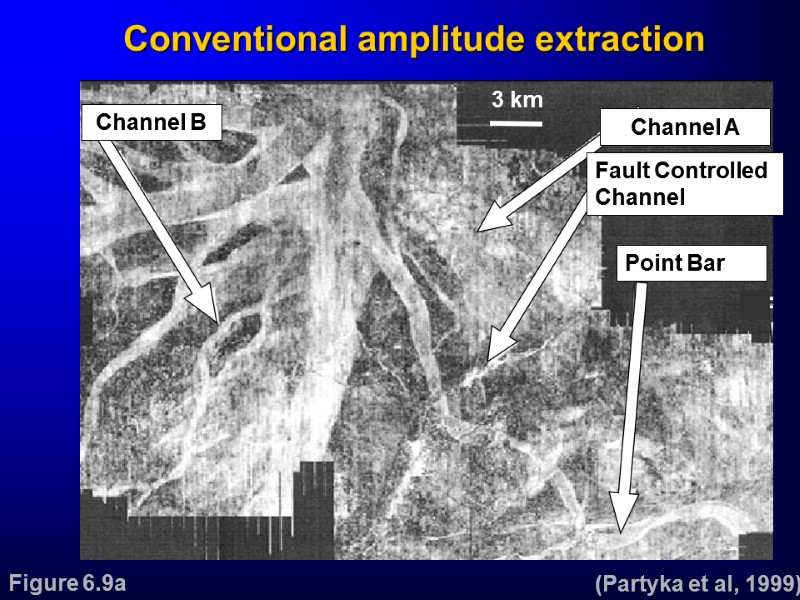

(Partyka et al, 1999) Conventional amplitude extraction Figure 6.9a

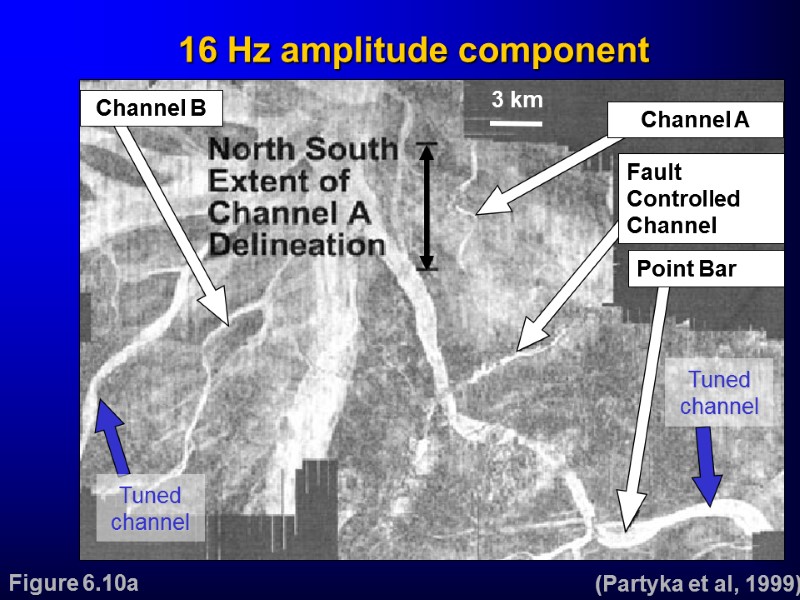

(Partyka et al, 1999) 16 Hz amplitude component Figure 6.10a

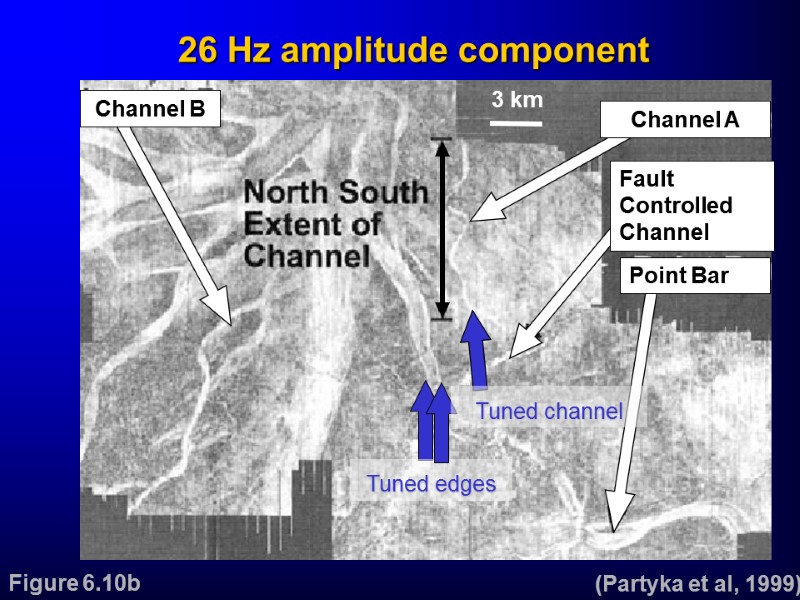

Channel A Fault Controlled Channel Point Bar Channel B (Partyka et al, 1999) 26 Hz amplitude component Tuned edges Tuned channel Figure 6.10b

6704-marfurt_k._2_-_spec_decomp.ppt

- Количество слайдов: 73