5549238be7af2c258ba39f305ef0e4db.ppt

- Количество слайдов: 53

Secondary Prevention of ASCVD: Novel Therapies to Improve Outcomes in Patients with Hypercholesterolemia

Secondary Prevention of ASCVD: Novel Therapies to Improve Outcomes in Patients with Hypercholesterolemia

Lynne T. Braun, Ph. D, CNP, FAHA, FAANP, FPCNA, FAAN, FNLA Professor of Nursing and Medicine Nurse Practitioner Department of Adult Health and Gerontological Nursing Rush University College of Nursing Department of Internal Medicine Rush Heart Center for Women Chicago, IL Dr. Braun discloses that she has served as an author and on the advisory board for Up. To. Date/Wolters. Kluwer.

Lynne T. Braun, Ph. D, CNP, FAHA, FAANP, FPCNA, FAAN, FNLA Professor of Nursing and Medicine Nurse Practitioner Department of Adult Health and Gerontological Nursing Rush University College of Nursing Department of Internal Medicine Rush Heart Center for Women Chicago, IL Dr. Braun discloses that she has served as an author and on the advisory board for Up. To. Date/Wolters. Kluwer.

Please complete the pre-activity survey.

Please complete the pre-activity survey.

This program is supported by educational funding provided by Amgen and Sanofi US and Regeneron Pharmaceuticals.

This program is supported by educational funding provided by Amgen and Sanofi US and Regeneron Pharmaceuticals.

Learning Objectives Upon completion of this educational activity, the participant should be able to: • Outline the mechanisms of action for PCSK 9 inhibitors. • Identify potential advantages, disadvantages, and clinical uses for PCSK 9 inhibitors. • Discuss guideline controversies with regard to statin use for the treatment of patients with ASCVD and hypercholesterolemia. • Develop a plan to increase patient adherence to treatment regimens for hypercholesterolemia.

Learning Objectives Upon completion of this educational activity, the participant should be able to: • Outline the mechanisms of action for PCSK 9 inhibitors. • Identify potential advantages, disadvantages, and clinical uses for PCSK 9 inhibitors. • Discuss guideline controversies with regard to statin use for the treatment of patients with ASCVD and hypercholesterolemia. • Develop a plan to increase patient adherence to treatment regimens for hypercholesterolemia.

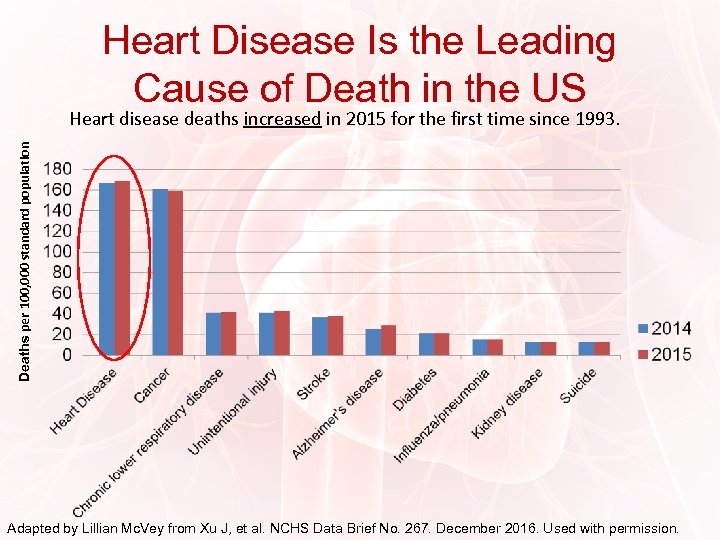

Heart Disease Is the Leading Cause of Death in the US Deaths per 100, 000 standard population Heart disease deaths increased in 2015 for the first time since 1993. Adapted by Lillian Mc. Vey from Xu J, et al. NCHS Data Brief No. 267. December 2016. Used with permission.

Heart Disease Is the Leading Cause of Death in the US Deaths per 100, 000 standard population Heart disease deaths increased in 2015 for the first time since 1993. Adapted by Lillian Mc. Vey from Xu J, et al. NCHS Data Brief No. 267. December 2016. Used with permission.

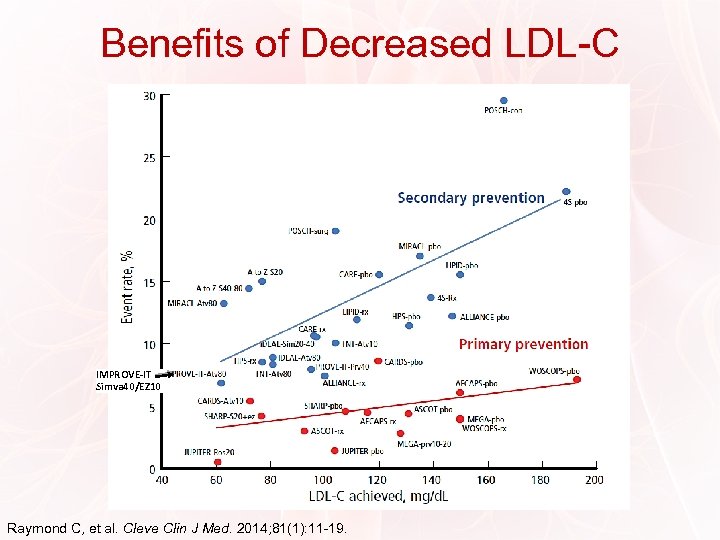

Benefits of Decreased LDL-C LDL: Lower is Better IMPROVE-IT Simva 40/EZ 10 Raymond C, et al. Cleve Clin J Med. 2014; 81(1): 11 -19.

Benefits of Decreased LDL-C LDL: Lower is Better IMPROVE-IT Simva 40/EZ 10 Raymond C, et al. Cleve Clin J Med. 2014; 81(1): 11 -19.

Efficacy and Safety of LDL-Lowering Therapy • Meta-analysis of outcomes from 174, 000 participants in 27 randomized trials • Overall, a 20% to 25% RRR of major vascular events with statin therapy or more intensive statin therapy • This translated to an approximate 1% reduction in CHD deaths for every 2 mg/d. L lowering in LDL-C Cholesterol Treatment Trialists’ (CTT) Collaboration. Lancet. 2015; 385(9976): 1397 -1405.

Efficacy and Safety of LDL-Lowering Therapy • Meta-analysis of outcomes from 174, 000 participants in 27 randomized trials • Overall, a 20% to 25% RRR of major vascular events with statin therapy or more intensive statin therapy • This translated to an approximate 1% reduction in CHD deaths for every 2 mg/d. L lowering in LDL-C Cholesterol Treatment Trialists’ (CTT) Collaboration. Lancet. 2015; 385(9976): 1397 -1405.

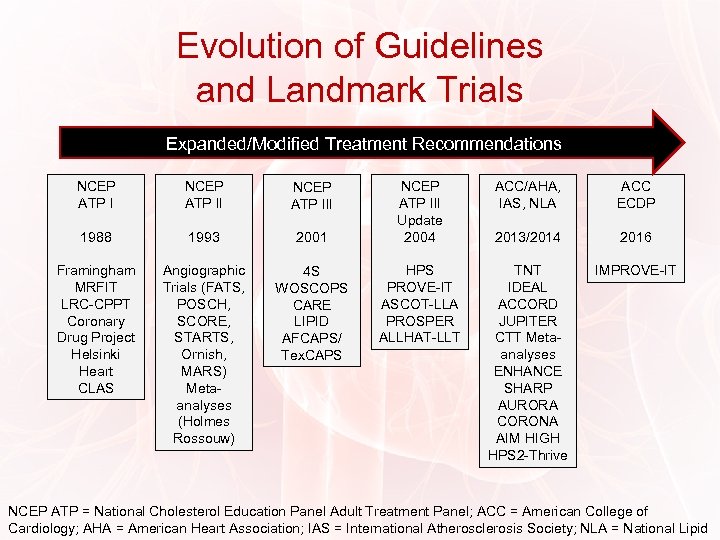

Evolution of Guidelines and Landmark Trials Expanded/Modified Treatment Recommendations NCEP ATP III 1988 1993 2001 Framingham MRFIT LRC-CPPT Coronary Drug Project Helsinki Heart CLAS Angiographic Trials (FATS, POSCH, SCORE, STARTS, Ornish, MARS) Metaanalyses (Holmes Rossouw) 4 S WOSCOPS CARE LIPID AFCAPS/ Tex. CAPS NCEP ATP III Update 2004 HPS PROVE-IT ASCOT-LLA PROSPER ALLHAT-LLT ACC/AHA, IAS, NLA ACC ECDP 2013/2014 2016 TNT IDEAL ACCORD JUPITER CTT Metaanalyses ENHANCE SHARP AURORA CORONA AIM HIGH HPS 2 -Thrive IMPROVE-IT NCEP ATP = National Cholesterol Education Panel Adult Treatment Panel; ACC = American College of Cardiology; AHA = American Heart Association; IAS = International Atherosclerosis Society; NLA = National Lipid

Evolution of Guidelines and Landmark Trials Expanded/Modified Treatment Recommendations NCEP ATP III 1988 1993 2001 Framingham MRFIT LRC-CPPT Coronary Drug Project Helsinki Heart CLAS Angiographic Trials (FATS, POSCH, SCORE, STARTS, Ornish, MARS) Metaanalyses (Holmes Rossouw) 4 S WOSCOPS CARE LIPID AFCAPS/ Tex. CAPS NCEP ATP III Update 2004 HPS PROVE-IT ASCOT-LLA PROSPER ALLHAT-LLT ACC/AHA, IAS, NLA ACC ECDP 2013/2014 2016 TNT IDEAL ACCORD JUPITER CTT Metaanalyses ENHANCE SHARP AURORA CORONA AIM HIGH HPS 2 -Thrive IMPROVE-IT NCEP ATP = National Cholesterol Education Panel Adult Treatment Panel; ACC = American College of Cardiology; AHA = American Heart Association; IAS = International Atherosclerosis Society; NLA = National Lipid

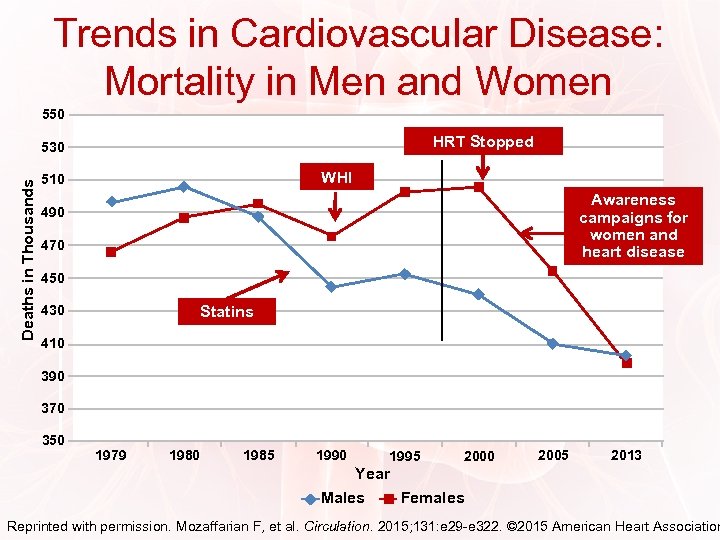

Trends in Cardiovascular Disease: Mortality in Men and Women 550 HRT Stopped Deaths in Thousands 530 WHI 510 Awareness campaigns for women and heart disease 490 470 450 430 Statins 410 390 370 350 1979 1980 1985 1990 1995 2000 2005 2013 Year Males Females Reprinted with permission. Mozaffarian F, et al. Circulation. 2015; 131: e 29 -e 322. © 2015 American Heart Association

Trends in Cardiovascular Disease: Mortality in Men and Women 550 HRT Stopped Deaths in Thousands 530 WHI 510 Awareness campaigns for women and heart disease 490 470 450 430 Statins 410 390 370 350 1979 1980 1985 1990 1995 2000 2005 2013 Year Males Females Reprinted with permission. Mozaffarian F, et al. Circulation. 2015; 131: e 29 -e 322. © 2015 American Heart Association

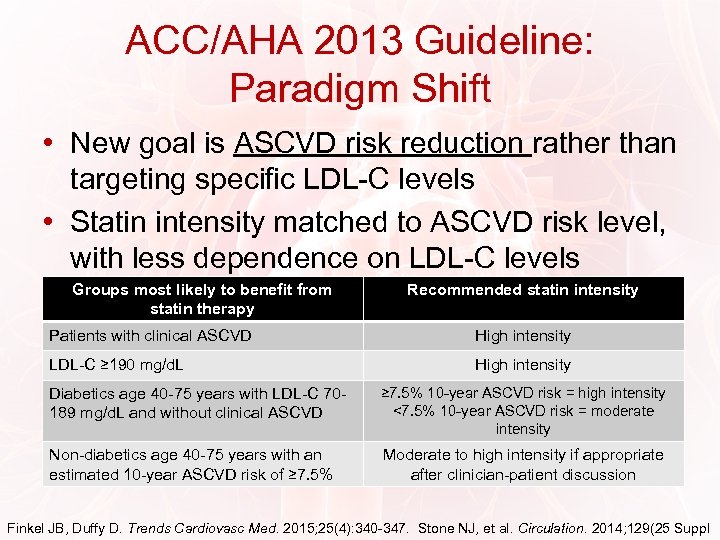

ACC/AHA 2013 Guideline: Paradigm Shift • New goal is ASCVD risk reduction rather than targeting specific LDL-C levels • Statin intensity matched to ASCVD risk level, with less dependence on LDL-C levels Groups most likely to benefit from statin therapy Recommended statin intensity Patients with clinical ASCVD High intensity LDL-C ≥ 190 mg/d. L High intensity Diabetics age 40 -75 years with LDL-C 70189 mg/d. L and without clinical ASCVD ≥ 7. 5% 10 -year ASCVD risk = high intensity <7. 5% 10 -year ASCVD risk = moderate intensity Non-diabetics age 40 -75 years with an estimated 10 -year ASCVD risk of ≥ 7. 5% Moderate to high intensity if appropriate after clinician-patient discussion Finkel JB, Duffy D. Trends Cardiovasc Med. 2015; 25(4): 340 -347. Stone NJ, et al. Circulation. 2014; 129(25 Suppl

ACC/AHA 2013 Guideline: Paradigm Shift • New goal is ASCVD risk reduction rather than targeting specific LDL-C levels • Statin intensity matched to ASCVD risk level, with less dependence on LDL-C levels Groups most likely to benefit from statin therapy Recommended statin intensity Patients with clinical ASCVD High intensity LDL-C ≥ 190 mg/d. L High intensity Diabetics age 40 -75 years with LDL-C 70189 mg/d. L and without clinical ASCVD ≥ 7. 5% 10 -year ASCVD risk = high intensity <7. 5% 10 -year ASCVD risk = moderate intensity Non-diabetics age 40 -75 years with an estimated 10 -year ASCVD risk of ≥ 7. 5% Moderate to high intensity if appropriate after clinician-patient discussion Finkel JB, Duffy D. Trends Cardiovasc Med. 2015; 25(4): 340 -347. Stone NJ, et al. Circulation. 2014; 129(25 Suppl

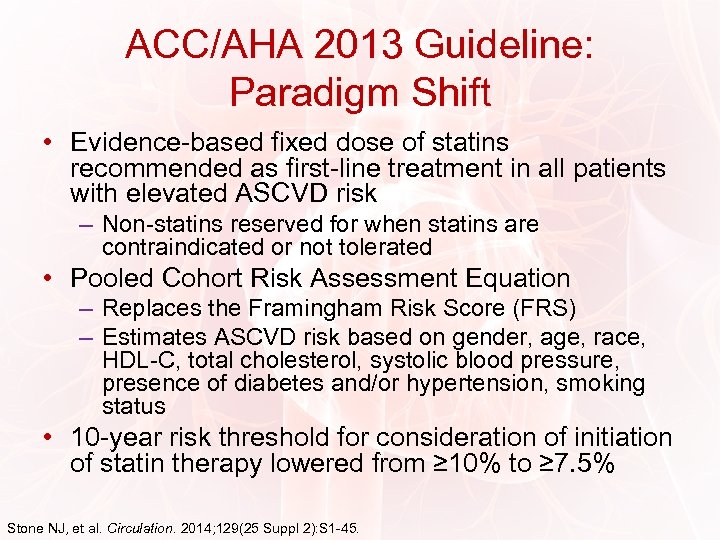

ACC/AHA 2013 Guideline: Paradigm Shift • Evidence-based fixed dose of statins recommended as first-line treatment in all patients with elevated ASCVD risk – Non-statins reserved for when statins are contraindicated or not tolerated • Pooled Cohort Risk Assessment Equation – Replaces the Framingham Risk Score (FRS) – Estimates ASCVD risk based on gender, age, race, HDL-C, total cholesterol, systolic blood pressure, presence of diabetes and/or hypertension, smoking status • 10 -year risk threshold for consideration of initiation of statin therapy lowered from ≥ 10% to ≥ 7. 5% Stone NJ, et al. Circulation. 2014; 129(25 Suppl 2): S 1 -45.

ACC/AHA 2013 Guideline: Paradigm Shift • Evidence-based fixed dose of statins recommended as first-line treatment in all patients with elevated ASCVD risk – Non-statins reserved for when statins are contraindicated or not tolerated • Pooled Cohort Risk Assessment Equation – Replaces the Framingham Risk Score (FRS) – Estimates ASCVD risk based on gender, age, race, HDL-C, total cholesterol, systolic blood pressure, presence of diabetes and/or hypertension, smoking status • 10 -year risk threshold for consideration of initiation of statin therapy lowered from ≥ 10% to ≥ 7. 5% Stone NJ, et al. Circulation. 2014; 129(25 Suppl 2): S 1 -45.

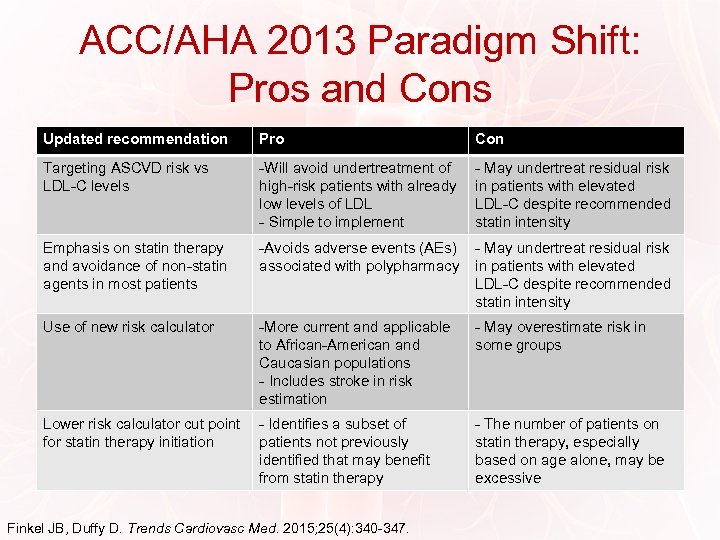

ACC/AHA 2013 Paradigm Shift: Pros and Cons Updated recommendation Pro Con Targeting ASCVD risk vs LDL-C levels -Will avoid undertreatment of high-risk patients with already low levels of LDL - Simple to implement - May undertreat residual risk in patients with elevated LDL-C despite recommended statin intensity Emphasis on statin therapy and avoidance of non-statin agents in most patients -Avoids adverse events (AEs) associated with polypharmacy - May undertreat residual risk in patients with elevated LDL-C despite recommended statin intensity Use of new risk calculator -More current and applicable to African-American and Caucasian populations - Includes stroke in risk estimation - May overestimate risk in some groups Lower risk calculator cut point for statin therapy initiation - Identifies a subset of patients not previously identified that may benefit from statin therapy - The number of patients on statin therapy, especially based on age alone, may be excessive Finkel JB, Duffy D. Trends Cardiovasc Med. 2015; 25(4): 340 -347.

ACC/AHA 2013 Paradigm Shift: Pros and Cons Updated recommendation Pro Con Targeting ASCVD risk vs LDL-C levels -Will avoid undertreatment of high-risk patients with already low levels of LDL - Simple to implement - May undertreat residual risk in patients with elevated LDL-C despite recommended statin intensity Emphasis on statin therapy and avoidance of non-statin agents in most patients -Avoids adverse events (AEs) associated with polypharmacy - May undertreat residual risk in patients with elevated LDL-C despite recommended statin intensity Use of new risk calculator -More current and applicable to African-American and Caucasian populations - Includes stroke in risk estimation - May overestimate risk in some groups Lower risk calculator cut point for statin therapy initiation - Identifies a subset of patients not previously identified that may benefit from statin therapy - The number of patients on statin therapy, especially based on age alone, may be excessive Finkel JB, Duffy D. Trends Cardiovasc Med. 2015; 25(4): 340 -347.

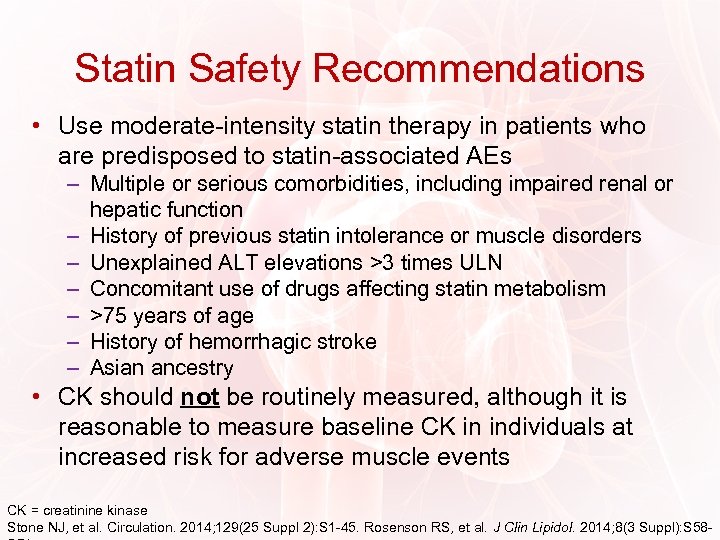

Statin Safety Recommendations • Use moderate-intensity statin therapy in patients who are predisposed to statin-associated AEs – Multiple or serious comorbidities, including impaired renal or hepatic function – History of previous statin intolerance or muscle disorders – Unexplained ALT elevations >3 times ULN – Concomitant use of drugs affecting statin metabolism – >75 years of age – History of hemorrhagic stroke – Asian ancestry • CK should not be routinely measured, although it is reasonable to measure baseline CK in individuals at increased risk for adverse muscle events CK = creatinine kinase Stone NJ, et al. Circulation. 2014; 129(25 Suppl 2): S 1 -45. Rosenson RS, et al. J Clin Lipidol. 2014; 8(3 Suppl): S 58 -

Statin Safety Recommendations • Use moderate-intensity statin therapy in patients who are predisposed to statin-associated AEs – Multiple or serious comorbidities, including impaired renal or hepatic function – History of previous statin intolerance or muscle disorders – Unexplained ALT elevations >3 times ULN – Concomitant use of drugs affecting statin metabolism – >75 years of age – History of hemorrhagic stroke – Asian ancestry • CK should not be routinely measured, although it is reasonable to measure baseline CK in individuals at increased risk for adverse muscle events CK = creatinine kinase Stone NJ, et al. Circulation. 2014; 129(25 Suppl 2): S 1 -45. Rosenson RS, et al. J Clin Lipidol. 2014; 8(3 Suppl): S 58 -

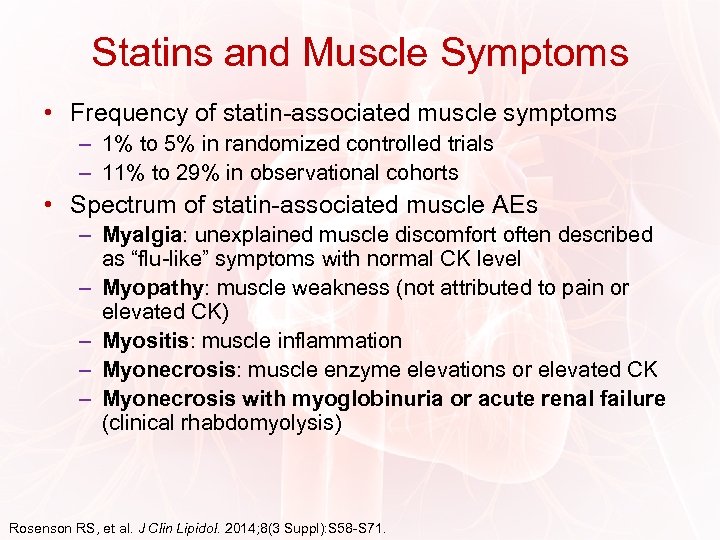

Statins and Muscle Symptoms • Frequency of statin-associated muscle symptoms – 1% to 5% in randomized controlled trials – 11% to 29% in observational cohorts • Spectrum of statin-associated muscle AEs – Myalgia: unexplained muscle discomfort often described as “flu-like” symptoms with normal CK level – Myopathy: muscle weakness (not attributed to pain or elevated CK) – Myositis: muscle inflammation – Myonecrosis: muscle enzyme elevations or elevated CK – Myonecrosis with myoglobinuria or acute renal failure (clinical rhabdomyolysis) Rosenson RS, et al. J Clin Lipidol. 2014; 8(3 Suppl): S 58 -S 71.

Statins and Muscle Symptoms • Frequency of statin-associated muscle symptoms – 1% to 5% in randomized controlled trials – 11% to 29% in observational cohorts • Spectrum of statin-associated muscle AEs – Myalgia: unexplained muscle discomfort often described as “flu-like” symptoms with normal CK level – Myopathy: muscle weakness (not attributed to pain or elevated CK) – Myositis: muscle inflammation – Myonecrosis: muscle enzyme elevations or elevated CK – Myonecrosis with myoglobinuria or acute renal failure (clinical rhabdomyolysis) Rosenson RS, et al. J Clin Lipidol. 2014; 8(3 Suppl): S 58 -S 71.

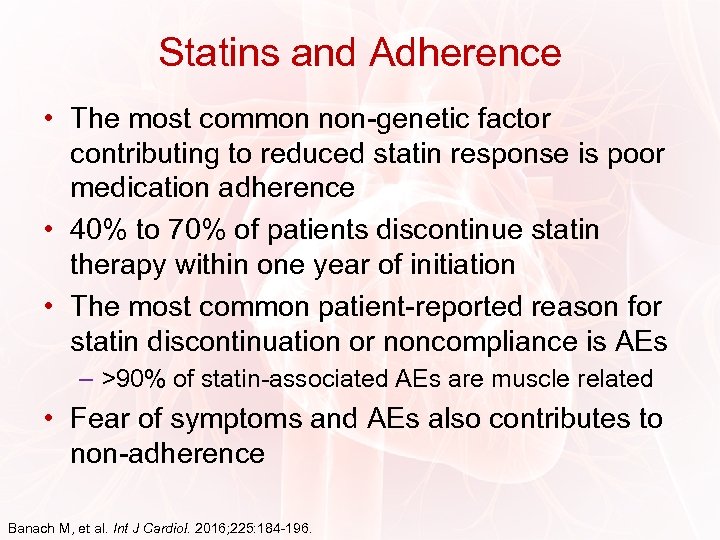

Statins and Adherence • The most common non-genetic factor contributing to reduced statin response is poor medication adherence • 40% to 70% of patients discontinue statin therapy within one year of initiation • The most common patient-reported reason for statin discontinuation or noncompliance is AEs – >90% of statin-associated AEs are muscle related • Fear of symptoms and AEs also contributes to non-adherence Banach M, et al. Int J Cardiol. 2016; 225: 184 -196.

Statins and Adherence • The most common non-genetic factor contributing to reduced statin response is poor medication adherence • 40% to 70% of patients discontinue statin therapy within one year of initiation • The most common patient-reported reason for statin discontinuation or noncompliance is AEs – >90% of statin-associated AEs are muscle related • Fear of symptoms and AEs also contributes to non-adherence Banach M, et al. Int J Cardiol. 2016; 225: 184 -196.

Provider-Related Factors That May Impact Adherence • Failure to provide adequate explanations of benefits/AEs of medications • Ineffective communication with the patient • Perceived lack of efficacy in medication regimen • Prescribing complex drug regimens • Neglecting to consider cost issues • Neglecting to communicate among patient’s various providers • Lack of time, lack of time!

Provider-Related Factors That May Impact Adherence • Failure to provide adequate explanations of benefits/AEs of medications • Ineffective communication with the patient • Perceived lack of efficacy in medication regimen • Prescribing complex drug regimens • Neglecting to consider cost issues • Neglecting to communicate among patient’s various providers • Lack of time, lack of time!

Improving Adherence: NLA Recommendations • Simplify the regimen • Provide clear education using visual aids and simple, low-literacy educational materials • Engage patients in decision making, addressing their specific needs, values, and concerns • Address perceived barriers of taking medications • Identify suboptimal health literacy and use “teach-back” techniques to increase patient understanding of those behaviors needed to be successful • Screen and eliminate drug-drug and drug-disease interactions leading to low adherence or drug discontinuation • Praise and reward successful behaviors Jacobson TA, et al. J Clin Lipidol. 2015; 9(6): S 1 -S 122.

Improving Adherence: NLA Recommendations • Simplify the regimen • Provide clear education using visual aids and simple, low-literacy educational materials • Engage patients in decision making, addressing their specific needs, values, and concerns • Address perceived barriers of taking medications • Identify suboptimal health literacy and use “teach-back” techniques to increase patient understanding of those behaviors needed to be successful • Screen and eliminate drug-drug and drug-disease interactions leading to low adherence or drug discontinuation • Praise and reward successful behaviors Jacobson TA, et al. J Clin Lipidol. 2015; 9(6): S 1 -S 122.

Statin Intolerance • Definition: – A clinical syndrome characterized by the inability to tolerate at least 2 statins – Manifests as either objectionable symptoms (real or perceived) or abnormal lab determinations, which are temporally related to statin treatment • Reversible upon discontinuation • Reproducible by re-challenge • Approximately 1 in 10 patients taking statins will report intolerance • Novel non-statin agents may be appropriate in intolerant individuals Guyton JR, et al. J Clin Lipidol. 2014; 8(3 Suppl): S 72 -S 81. Rosenson RS, et al. J Clin Lipidol. 2014; 8(3 Suppl): S 58 -S 71.

Statin Intolerance • Definition: – A clinical syndrome characterized by the inability to tolerate at least 2 statins – Manifests as either objectionable symptoms (real or perceived) or abnormal lab determinations, which are temporally related to statin treatment • Reversible upon discontinuation • Reproducible by re-challenge • Approximately 1 in 10 patients taking statins will report intolerance • Novel non-statin agents may be appropriate in intolerant individuals Guyton JR, et al. J Clin Lipidol. 2014; 8(3 Suppl): S 72 -S 81. Rosenson RS, et al. J Clin Lipidol. 2014; 8(3 Suppl): S 58 -S 71.

Managing Muscle Symptoms • Switch to an alternate statin – 92% of patients are able to tolerate a second statin after discontinuing their initial statin due to AEs – 72. 5% of patients who are intolerant to 2 statins due to myalgia can successfully tolerate a third statin • Use an alternate dosing strategy – Lower dose of the same statin – Less-than-daily dosing • Once-weekly dosing of a long-acting statin • Switch to non-statin lipid-lowering therapy in truly intolerant patients Rosenson RS, et al. J Clin Lipidol. 2014; 8(3 Suppl): S 58 -S 71.

Managing Muscle Symptoms • Switch to an alternate statin – 92% of patients are able to tolerate a second statin after discontinuing their initial statin due to AEs – 72. 5% of patients who are intolerant to 2 statins due to myalgia can successfully tolerate a third statin • Use an alternate dosing strategy – Lower dose of the same statin – Less-than-daily dosing • Once-weekly dosing of a long-acting statin • Switch to non-statin lipid-lowering therapy in truly intolerant patients Rosenson RS, et al. J Clin Lipidol. 2014; 8(3 Suppl): S 58 -S 71.

Statin Intolerance Recommendations For providers: • Statin intolerance is a real and valid phenomenon • Statin use may increase hepatic transaminase levels, the risk for diabetes mellitus, and cognitive difficulties • Decisions on statin intolerance should be made in conjunction with the patient – Providers should help patients distinguish statin intolerance from “drug allergy” – Statin treatment should be maintained whenever possible in patients with statin intolerance Guyton JR, et al. J Clin Lipidol. 2014; 8(3 Suppl): S 72 -S 81.

Statin Intolerance Recommendations For providers: • Statin intolerance is a real and valid phenomenon • Statin use may increase hepatic transaminase levels, the risk for diabetes mellitus, and cognitive difficulties • Decisions on statin intolerance should be made in conjunction with the patient – Providers should help patients distinguish statin intolerance from “drug allergy” – Statin treatment should be maintained whenever possible in patients with statin intolerance Guyton JR, et al. J Clin Lipidol. 2014; 8(3 Suppl): S 72 -S 81.

Statin Intolerance Recommendations For patients: • Statin therapy is one of the most effective ways to lower the risk of atherosclerosis • The prevention of death and disability from improved atherosclerosis is far greater than the risk of taking a statin • There is little evidence that statins damage the liver or block essential functions of the liver • Before stopping a statin due to side effects, counsel with a health care professional is advised • Most people who experience intolerance to a statin will be able to tolerate a second statin • Lifestyle changes are still an important aspect of reducing heart attack and stroke risk Guyton JR, et al. J Clin Lipidol. 2014; 8(3 Suppl): S 72 -S 81.

Statin Intolerance Recommendations For patients: • Statin therapy is one of the most effective ways to lower the risk of atherosclerosis • The prevention of death and disability from improved atherosclerosis is far greater than the risk of taking a statin • There is little evidence that statins damage the liver or block essential functions of the liver • Before stopping a statin due to side effects, counsel with a health care professional is advised • Most people who experience intolerance to a statin will be able to tolerate a second statin • Lifestyle changes are still an important aspect of reducing heart attack and stroke risk Guyton JR, et al. J Clin Lipidol. 2014; 8(3 Suppl): S 72 -S 81.

“Penicillin” for Cholesterol Infection Cholesterol lowering • The first statin, mevastatin (compactin), was isolated from penicillium citrinum in the 1970 s. • “The millions of people whose lives will be extended through statin therapy owe it all to Akira Endo. . . ” from: “A tribute to Akira Endo, discoverer of a ‘Penicillin’ for cholesterol. ” Atherosclerosis Supplements. 5(3): 13 -16 · October 2004.

“Penicillin” for Cholesterol Infection Cholesterol lowering • The first statin, mevastatin (compactin), was isolated from penicillium citrinum in the 1970 s. • “The millions of people whose lives will be extended through statin therapy owe it all to Akira Endo. . . ” from: “A tribute to Akira Endo, discoverer of a ‘Penicillin’ for cholesterol. ” Atherosclerosis Supplements. 5(3): 13 -16 · October 2004.

Intolerance and Adherence: Clinical Tips • Work with patients to establish pharmacologic and nonpharmacologic goals • Patient-provider communication – Discuss importance of statin treatment • Continuing treatment with statins prevents acute CV events • Review how statins work to prevent CV events – Review potential for AEs • Potential for AE is present with any new medication • Contact the provider if any changes in health or condition are observed – Stress the importance of adherence • Non-adherence is a major cause of inadequate LDL-C lowering and related negative health outcomes Banach M, et al. Int J Cardiol. 2016; 225: 184 -196.

Intolerance and Adherence: Clinical Tips • Work with patients to establish pharmacologic and nonpharmacologic goals • Patient-provider communication – Discuss importance of statin treatment • Continuing treatment with statins prevents acute CV events • Review how statins work to prevent CV events – Review potential for AEs • Potential for AE is present with any new medication • Contact the provider if any changes in health or condition are observed – Stress the importance of adherence • Non-adherence is a major cause of inadequate LDL-C lowering and related negative health outcomes Banach M, et al. Int J Cardiol. 2016; 225: 184 -196.

Monitoring and Optimizing Statins • Monitoring statin therapy – Regularly assess adherence to medication, lifestyle, and therapeutic response – Perform fasting lipid panel within 4 -12 weeks after initiation or dose adjustment • Every 3 -12 months thereafter • Optimizing statin therapy – Maximum tolerated intensity of statin should be used in individuals for whom a high- or moderateintensity statin is recommended, but not tolerated Stone NJ, et al. Circulation. 2014; 129(25 Suppl 2): S 1 -45.

Monitoring and Optimizing Statins • Monitoring statin therapy – Regularly assess adherence to medication, lifestyle, and therapeutic response – Perform fasting lipid panel within 4 -12 weeks after initiation or dose adjustment • Every 3 -12 months thereafter • Optimizing statin therapy – Maximum tolerated intensity of statin should be used in individuals for whom a high- or moderateintensity statin is recommended, but not tolerated Stone NJ, et al. Circulation. 2014; 129(25 Suppl 2): S 1 -45.

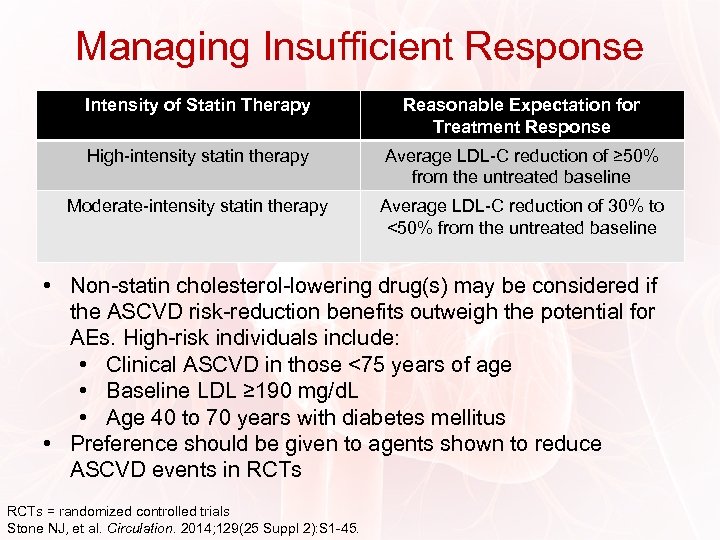

Managing Insufficient Response Intensity of Statin Therapy Reasonable Expectation for Treatment Response High-intensity statin therapy Average LDL-C reduction of ≥ 50% from the untreated baseline Moderate-intensity statin therapy Average LDL-C reduction of 30% to <50% from the untreated baseline • Non-statin cholesterol-lowering drug(s) may be considered if the ASCVD risk-reduction benefits outweigh the potential for AEs. High-risk individuals include: • Clinical ASCVD in those <75 years of age • Baseline LDL ≥ 190 mg/d. L • Age 40 to 70 years with diabetes mellitus • Preference should be given to agents shown to reduce ASCVD events in RCTs = randomized controlled trials Stone NJ, et al. Circulation. 2014; 129(25 Suppl 2): S 1 -45.

Managing Insufficient Response Intensity of Statin Therapy Reasonable Expectation for Treatment Response High-intensity statin therapy Average LDL-C reduction of ≥ 50% from the untreated baseline Moderate-intensity statin therapy Average LDL-C reduction of 30% to <50% from the untreated baseline • Non-statin cholesterol-lowering drug(s) may be considered if the ASCVD risk-reduction benefits outweigh the potential for AEs. High-risk individuals include: • Clinical ASCVD in those <75 years of age • Baseline LDL ≥ 190 mg/d. L • Age 40 to 70 years with diabetes mellitus • Preference should be given to agents shown to reduce ASCVD events in RCTs = randomized controlled trials Stone NJ, et al. Circulation. 2014; 129(25 Suppl 2): S 1 -45.

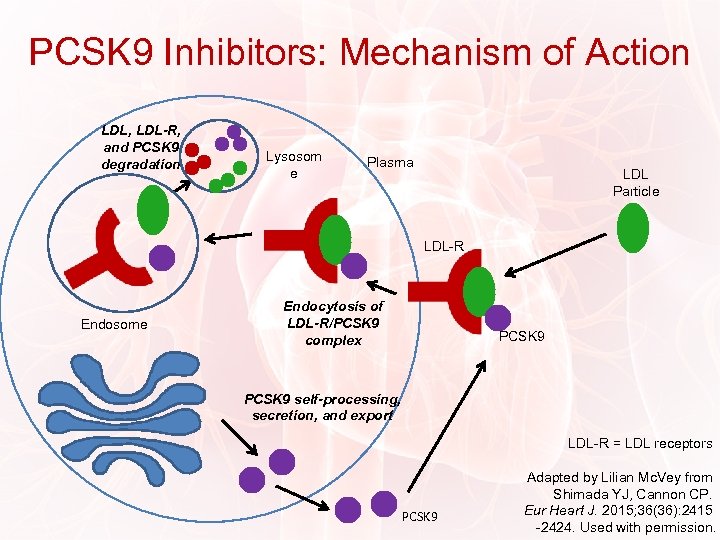

PCSK 9 • A secreted enzymatic protein of the subtilisin family of serine proteases • Primarily synthesized in the liver; also found in the intestines and kidneys • Interferes with removal of LDL particles from circulation • Binds with the LDL-R/LDL complex – Complex is degraded by the lysosome → degradation of the LDL-R – LDL-R can’t recycle to the cell membrane – LDL clearance is decreased • Gain of function mutations are associated with FH and premature CVD FH = familial hypercholesterolemia; CVD = cardiovascular disease. Joseph L, Robinson JG. Prog Cardiovasc Dis. 2015; 58(1): 19 -31.

PCSK 9 • A secreted enzymatic protein of the subtilisin family of serine proteases • Primarily synthesized in the liver; also found in the intestines and kidneys • Interferes with removal of LDL particles from circulation • Binds with the LDL-R/LDL complex – Complex is degraded by the lysosome → degradation of the LDL-R – LDL-R can’t recycle to the cell membrane – LDL clearance is decreased • Gain of function mutations are associated with FH and premature CVD FH = familial hypercholesterolemia; CVD = cardiovascular disease. Joseph L, Robinson JG. Prog Cardiovasc Dis. 2015; 58(1): 19 -31.

PCSK 9 (cont’d) • Individuals with loss-of-function PCSK 9 gene mutations… – Have LDL-C levels that are 28% lower than those without the mutation – Have an 88% relative decrease in risk for atherosclerotic CV events • Gain-of-function PCSK 9 gene mutations lead to increased levels of LDL-C Cohen JC, et al. N Engl J Med. 2006; 354(12): 1264 -1272.

PCSK 9 (cont’d) • Individuals with loss-of-function PCSK 9 gene mutations… – Have LDL-C levels that are 28% lower than those without the mutation – Have an 88% relative decrease in risk for atherosclerotic CV events • Gain-of-function PCSK 9 gene mutations lead to increased levels of LDL-C Cohen JC, et al. N Engl J Med. 2006; 354(12): 1264 -1272.

PCSK 9 Inhibitors: Mechanism of Action LDL, LDL-R, and PCSK 9 degradation Lysosom e Plasma LDL Particle LDL-R Endosome Endocytosis of LDL-R/PCSK 9 complex PCSK 9 self-processing, secretion, and export LDL-R = LDL receptors PCSK 9 Adapted by Lilian Mc. Vey from Shimada YJ, Cannon CP. Eur Heart J. 2015; 36(36): 2415 -2424. Used with permission.

PCSK 9 Inhibitors: Mechanism of Action LDL, LDL-R, and PCSK 9 degradation Lysosom e Plasma LDL Particle LDL-R Endosome Endocytosis of LDL-R/PCSK 9 complex PCSK 9 self-processing, secretion, and export LDL-R = LDL receptors PCSK 9 Adapted by Lilian Mc. Vey from Shimada YJ, Cannon CP. Eur Heart J. 2015; 36(36): 2415 -2424. Used with permission.

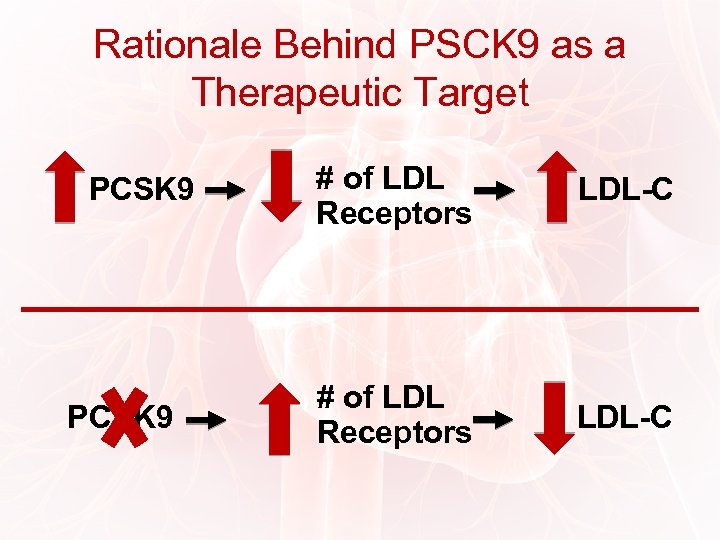

Rationale Behind PSCK 9 as a Therapeutic Target PCSK 9 # of LDL Receptors LDL-C

Rationale Behind PSCK 9 as a Therapeutic Target PCSK 9 # of LDL Receptors LDL-C

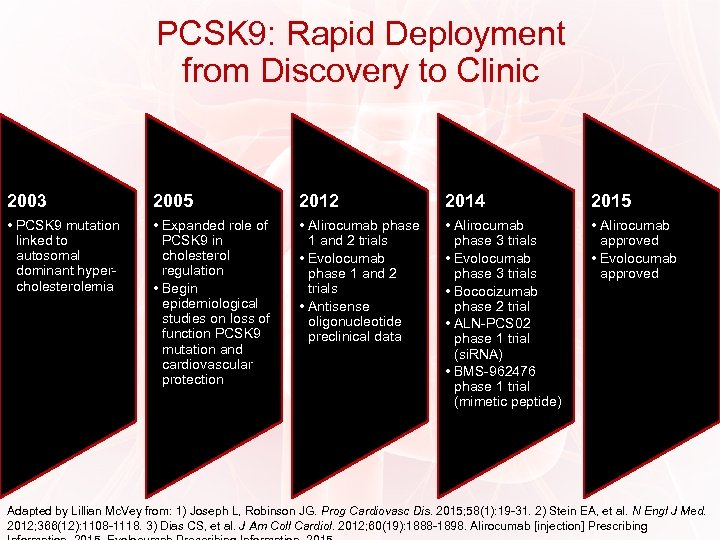

PCSK 9: Rapid Deployment from Discovery to Clinic 2003 2005 2012 2014 2015 • PCSK 9 mutation linked to autosomal dominant hypercholesterolemia • Expanded role of PCSK 9 in cholesterol regulation • Begin epidemiological studies on loss of function PCSK 9 mutation and cardiovascular protection • Alirocumab phase 1 and 2 trials • Evolocumab phase 1 and 2 trials • Antisense oligonucleotide preclinical data • Alirocumab phase 3 trials • Evolocumab phase 3 trials • Bococizumab phase 2 trial • ALN-PCS 02 phase 1 trial (si. RNA) • BMS-962476 phase 1 trial (mimetic peptide) • Alirocumab approved • Evolocumab approved Adapted by Lillian Mc. Vey from: 1) Joseph L, Robinson JG. Prog Cardiovasc Dis. 2015; 58(1): 19 -31. 2) Stein EA, et al. N Engl J Med. 2012; 366(12): 1108 -1118. 3) Dias CS, et al. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2012; 60(19): 1888 -1898. Alirocumab [injection] Prescribing

PCSK 9: Rapid Deployment from Discovery to Clinic 2003 2005 2012 2014 2015 • PCSK 9 mutation linked to autosomal dominant hypercholesterolemia • Expanded role of PCSK 9 in cholesterol regulation • Begin epidemiological studies on loss of function PCSK 9 mutation and cardiovascular protection • Alirocumab phase 1 and 2 trials • Evolocumab phase 1 and 2 trials • Antisense oligonucleotide preclinical data • Alirocumab phase 3 trials • Evolocumab phase 3 trials • Bococizumab phase 2 trial • ALN-PCS 02 phase 1 trial (si. RNA) • BMS-962476 phase 1 trial (mimetic peptide) • Alirocumab approved • Evolocumab approved Adapted by Lillian Mc. Vey from: 1) Joseph L, Robinson JG. Prog Cardiovasc Dis. 2015; 58(1): 19 -31. 2) Stein EA, et al. N Engl J Med. 2012; 366(12): 1108 -1118. 3) Dias CS, et al. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2012; 60(19): 1888 -1898. Alirocumab [injection] Prescribing

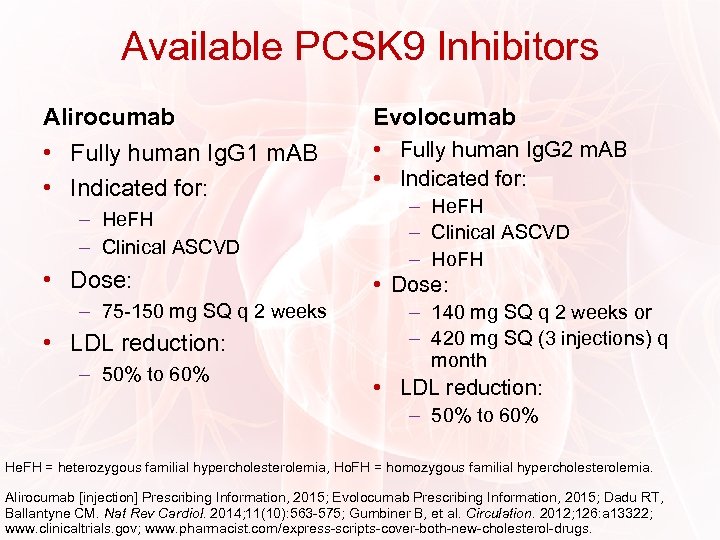

Available PCSK 9 Inhibitors Alirocumab Evolocumab • Fully human Ig. G 1 m. AB • Indicated for: • Fully human Ig. G 2 m. AB • Indicated for: – He. FH – Clinical ASCVD • Dose: – 75 -150 mg SQ q 2 weeks • LDL reduction: – 50% to 60% – He. FH – Clinical ASCVD – Ho. FH • Dose: – 140 mg SQ q 2 weeks or – 420 mg SQ (3 injections) q month • LDL reduction: – 50% to 60% He. FH = heterozygous familial hypercholesterolemia, Ho. FH = homozygous familial hypercholesterolemia. Alirocumab [injection] Prescribing Information, 2015; Evolocumab Prescribing Information, 2015; Dadu RT, Ballantyne CM. Nat Rev Cardiol. 2014; 11(10): 563 -575; Gumbiner B, et al. Circulation. 2012; 126: a 13322; www. clinicaltrials. gov; www. pharmacist. com/express-scripts-cover-both-new-cholesterol-drugs.

Available PCSK 9 Inhibitors Alirocumab Evolocumab • Fully human Ig. G 1 m. AB • Indicated for: • Fully human Ig. G 2 m. AB • Indicated for: – He. FH – Clinical ASCVD • Dose: – 75 -150 mg SQ q 2 weeks • LDL reduction: – 50% to 60% – He. FH – Clinical ASCVD – Ho. FH • Dose: – 140 mg SQ q 2 weeks or – 420 mg SQ (3 injections) q month • LDL reduction: – 50% to 60% He. FH = heterozygous familial hypercholesterolemia, Ho. FH = homozygous familial hypercholesterolemia. Alirocumab [injection] Prescribing Information, 2015; Evolocumab Prescribing Information, 2015; Dadu RT, Ballantyne CM. Nat Rev Cardiol. 2014; 11(10): 563 -575; Gumbiner B, et al. Circulation. 2012; 126: a 13322; www. clinicaltrials. gov; www. pharmacist. com/express-scripts-cover-both-new-cholesterol-drugs.

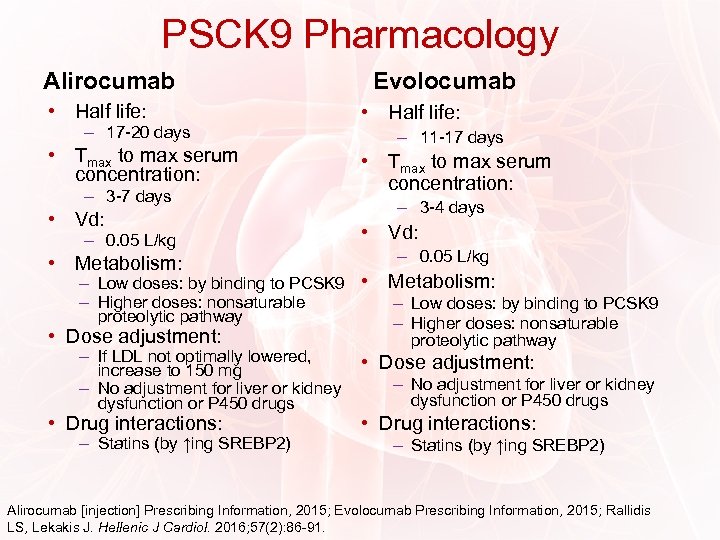

PSCK 9 Pharmacology Alirocumab • Half life: – 17 -20 days • Tmax to max serum concentration: – 3 -7 days • Vd: – 0. 05 L/kg • Metabolism: Evolocumab • Half life: – 11 -17 days • Tmax to max serum concentration: – 3 -4 days • Vd: – 0. 05 L/kg – Low doses: by binding to PCSK 9 • – Higher doses: nonsaturable proteolytic pathway • Dose adjustment: – If LDL not optimally lowered, increase to 150 mg – No adjustment for liver or kidney dysfunction or P 450 drugs • Drug interactions: – Statins (by ↑ing SREBP 2) Metabolism: – Low doses: by binding to PCSK 9 – Higher doses: nonsaturable proteolytic pathway • Dose adjustment: – No adjustment for liver or kidney dysfunction or P 450 drugs • Drug interactions: – Statins (by ↑ing SREBP 2) Alirocumab [injection] Prescribing Information, 2015; Evolocumab Prescribing Information, 2015; Rallidis LS, Lekakis J. Hellenic J Cardiol. 2016; 57(2): 86 -91.

PSCK 9 Pharmacology Alirocumab • Half life: – 17 -20 days • Tmax to max serum concentration: – 3 -7 days • Vd: – 0. 05 L/kg • Metabolism: Evolocumab • Half life: – 11 -17 days • Tmax to max serum concentration: – 3 -4 days • Vd: – 0. 05 L/kg – Low doses: by binding to PCSK 9 • – Higher doses: nonsaturable proteolytic pathway • Dose adjustment: – If LDL not optimally lowered, increase to 150 mg – No adjustment for liver or kidney dysfunction or P 450 drugs • Drug interactions: – Statins (by ↑ing SREBP 2) Metabolism: – Low doses: by binding to PCSK 9 – Higher doses: nonsaturable proteolytic pathway • Dose adjustment: – No adjustment for liver or kidney dysfunction or P 450 drugs • Drug interactions: – Statins (by ↑ing SREBP 2) Alirocumab [injection] Prescribing Information, 2015; Evolocumab Prescribing Information, 2015; Rallidis LS, Lekakis J. Hellenic J Cardiol. 2016; 57(2): 86 -91.

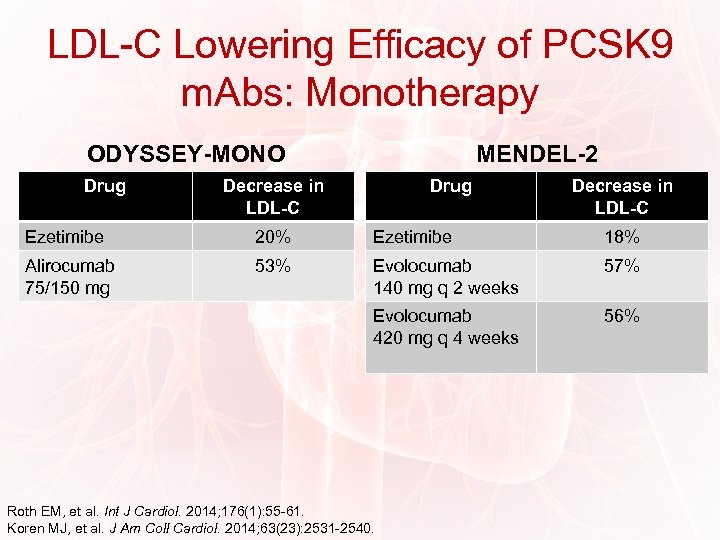

LDL-C Lowering Efficacy of PCSK 9 m. Abs: Monotherapy ODYSSEY-MONO Drug MENDEL-2 Decrease in LDL-C Drug Decrease in LDL-C Ezetimibe 20% Ezetimibe 18% Alirocumab 75/150 mg 53% Evolocumab 140 mg q 2 weeks 57% Evolocumab 420 mg q 4 weeks 56% Roth EM, et al. Int J Cardiol. 2014; 176(1): 55 -61. Koren MJ, et al. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2014; 63(23): 2531 -2540.

LDL-C Lowering Efficacy of PCSK 9 m. Abs: Monotherapy ODYSSEY-MONO Drug MENDEL-2 Decrease in LDL-C Drug Decrease in LDL-C Ezetimibe 20% Ezetimibe 18% Alirocumab 75/150 mg 53% Evolocumab 140 mg q 2 weeks 57% Evolocumab 420 mg q 4 weeks 56% Roth EM, et al. Int J Cardiol. 2014; 176(1): 55 -61. Koren MJ, et al. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2014; 63(23): 2531 -2540.

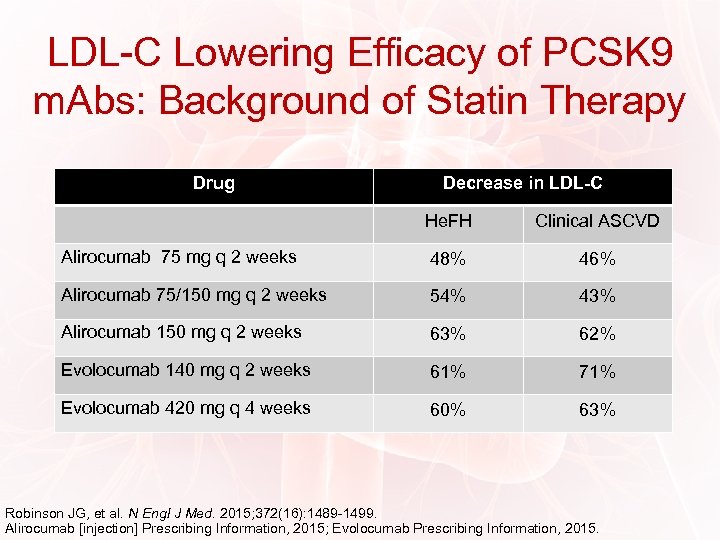

LDL-C Lowering Efficacy of PCSK 9 m. Abs: Background of Statin Therapy Drug Decrease in LDL-C He. FH Clinical ASCVD Alirocumab 75 mg q 2 weeks 48% 46% Alirocumab 75/150 mg q 2 weeks 54% 43% Alirocumab 150 mg q 2 weeks 63% 62% Evolocumab 140 mg q 2 weeks 61% 71% Evolocumab 420 mg q 4 weeks 60% 63% Robinson JG, et al. N Engl J Med. 2015; 372(16): 1489 -1499. Alirocumab [injection] Prescribing Information, 2015; Evolocumab Prescribing Information, 2015.

LDL-C Lowering Efficacy of PCSK 9 m. Abs: Background of Statin Therapy Drug Decrease in LDL-C He. FH Clinical ASCVD Alirocumab 75 mg q 2 weeks 48% 46% Alirocumab 75/150 mg q 2 weeks 54% 43% Alirocumab 150 mg q 2 weeks 63% 62% Evolocumab 140 mg q 2 weeks 61% 71% Evolocumab 420 mg q 4 weeks 60% 63% Robinson JG, et al. N Engl J Med. 2015; 372(16): 1489 -1499. Alirocumab [injection] Prescribing Information, 2015; Evolocumab Prescribing Information, 2015.

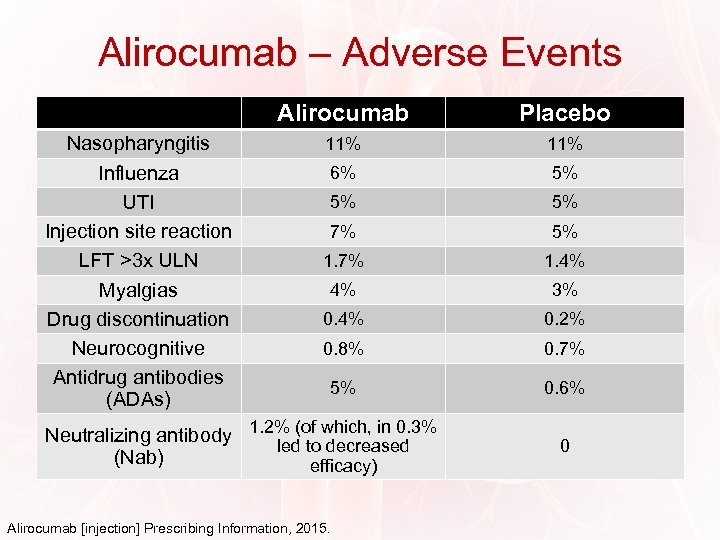

Alirocumab – Adverse Events Alirocumab Nasopharyngitis Influenza UTI Injection site reaction LFT >3 x ULN Myalgias Drug discontinuation Neurocognitive Antidrug antibodies (ADAs) Placebo 11% 6% 5% 5% 5% 7% 5% 1. 7% 1. 4% 4% 3% 0. 4% 0. 2% 0. 8% 0. 7% 5% 0. 6% Neutralizing antibody 1. 2% (of which, in 0. 3% led to decreased (Nab) efficacy) Alirocumab [injection] Prescribing Information, 2015. 0

Alirocumab – Adverse Events Alirocumab Nasopharyngitis Influenza UTI Injection site reaction LFT >3 x ULN Myalgias Drug discontinuation Neurocognitive Antidrug antibodies (ADAs) Placebo 11% 6% 5% 5% 5% 7% 5% 1. 7% 1. 4% 4% 3% 0. 4% 0. 2% 0. 8% 0. 7% 5% 0. 6% Neutralizing antibody 1. 2% (of which, in 0. 3% led to decreased (Nab) efficacy) Alirocumab [injection] Prescribing Information, 2015. 0

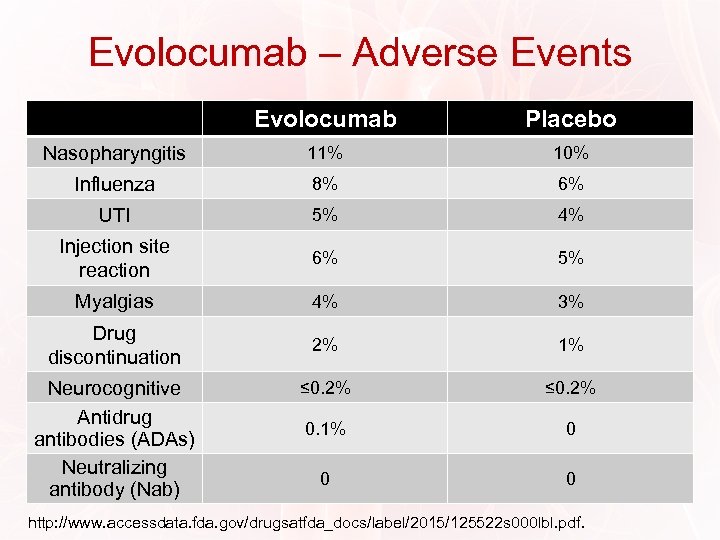

Evolocumab – Adverse Events Evolocumab Placebo Nasopharyngitis 11% 10% Influenza 8% 6% UTI 5% 4% Injection site reaction 6% 5% Myalgias 4% 3% Drug discontinuation 2% 1% ≤ 0. 2% 0. 1% 0 0 0 Neurocognitive Antidrug antibodies (ADAs) Neutralizing antibody (Nab) http: //www. accessdata. fda. gov/drugsatfda_docs/label/2015/125522 s 000 lbl. pdf.

Evolocumab – Adverse Events Evolocumab Placebo Nasopharyngitis 11% 10% Influenza 8% 6% UTI 5% 4% Injection site reaction 6% 5% Myalgias 4% 3% Drug discontinuation 2% 1% ≤ 0. 2% 0. 1% 0 0 0 Neurocognitive Antidrug antibodies (ADAs) Neutralizing antibody (Nab) http: //www. accessdata. fda. gov/drugsatfda_docs/label/2015/125522 s 000 lbl. pdf.

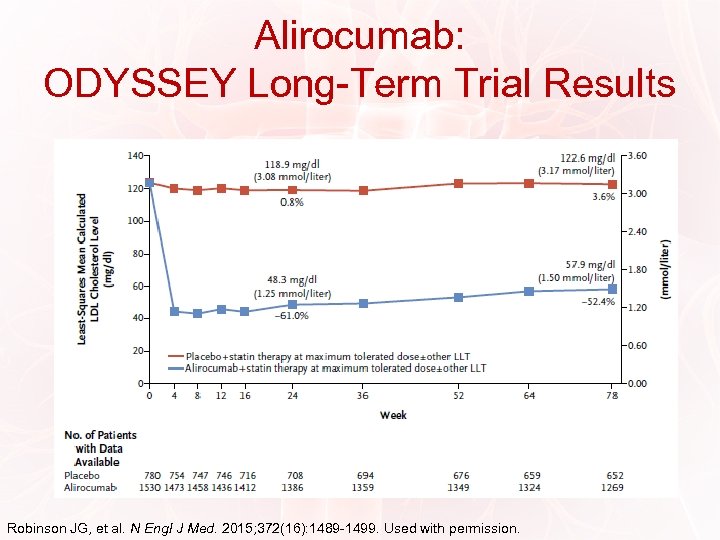

Alirocumab: ODYSSEY Long-Term Trial Results Robinson JG, et al. N Engl J Med. 2015; 372(16): 1489 -1499. Used with permission.

Alirocumab: ODYSSEY Long-Term Trial Results Robinson JG, et al. N Engl J Med. 2015; 372(16): 1489 -1499. Used with permission.

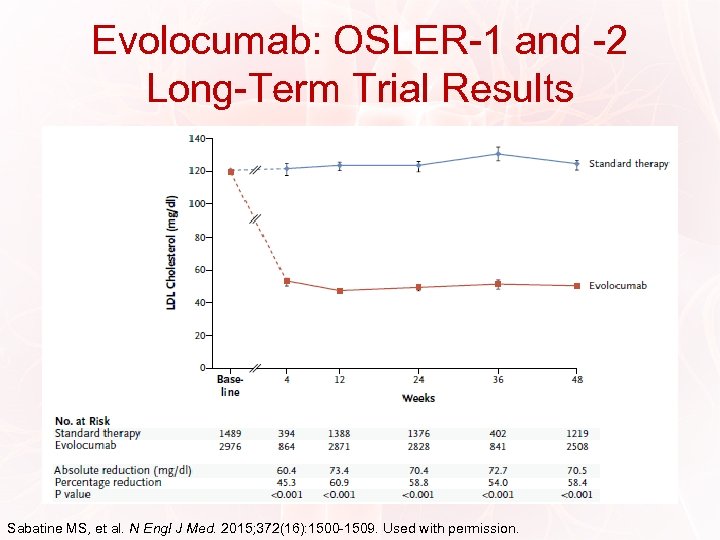

Evolocumab: OSLER-1 and -2 Long-Term Trial Results Sabatine MS, et al. N Engl J Med. 2015; 372(16): 1500 -1509. Used with permission.

Evolocumab: OSLER-1 and -2 Long-Term Trial Results Sabatine MS, et al. N Engl J Med. 2015; 372(16): 1500 -1509. Used with permission.

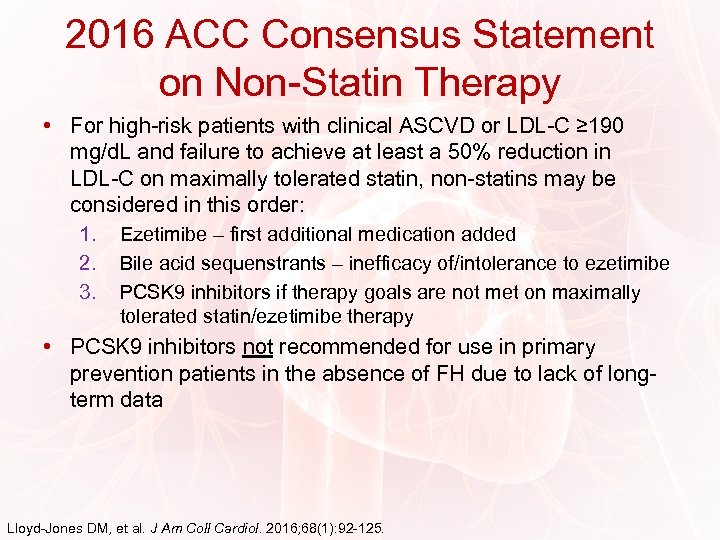

2016 ACC Consensus Statement on Non-Statin Therapy • For high-risk patients with clinical ASCVD or LDL-C ≥ 190 mg/d. L and failure to achieve at least a 50% reduction in LDL-C on maximally tolerated statin, non-statins may be considered in this order: 1. 2. 3. Ezetimibe – first additional medication added Bile acid sequenstrants – inefficacy of/intolerance to ezetimibe PCSK 9 inhibitors if therapy goals are not met on maximally tolerated statin/ezetimibe therapy • PCSK 9 inhibitors not recommended for use in primary prevention patients in the absence of FH due to lack of longterm data Lloyd-Jones DM, et al. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2016; 68(1): 92 -125.

2016 ACC Consensus Statement on Non-Statin Therapy • For high-risk patients with clinical ASCVD or LDL-C ≥ 190 mg/d. L and failure to achieve at least a 50% reduction in LDL-C on maximally tolerated statin, non-statins may be considered in this order: 1. 2. 3. Ezetimibe – first additional medication added Bile acid sequenstrants – inefficacy of/intolerance to ezetimibe PCSK 9 inhibitors if therapy goals are not met on maximally tolerated statin/ezetimibe therapy • PCSK 9 inhibitors not recommended for use in primary prevention patients in the absence of FH due to lack of longterm data Lloyd-Jones DM, et al. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2016; 68(1): 92 -125.

Clinical Tips for Therapeutic Management of PCSK 9 Inhibitors • First patient-administered injection should be performed in office after education – Offer to have second injection performed in office as well if the patient has ongoing reservations • Common mistakes during injection: – – – Expediting the warming phase Improper storage Failing to discard the pen Rubbing the site after injection is complete Pulling the pen away prior to the full injection (15 -20 seconds) Not pushing the pen down firmly such that yellow tip is still visible Alirocumab [injection] Prescribing Information, 2015; Evolocumab Prescribing Information, 2015.

Clinical Tips for Therapeutic Management of PCSK 9 Inhibitors • First patient-administered injection should be performed in office after education – Offer to have second injection performed in office as well if the patient has ongoing reservations • Common mistakes during injection: – – – Expediting the warming phase Improper storage Failing to discard the pen Rubbing the site after injection is complete Pulling the pen away prior to the full injection (15 -20 seconds) Not pushing the pen down firmly such that yellow tip is still visible Alirocumab [injection] Prescribing Information, 2015; Evolocumab Prescribing Information, 2015.

LDL Apheresis • Indicated when patients have failed diet and maximum drug therapy from at least 2 separate classes of hypolipidemic drugs for ≥ 6 months …Plus – He. FH with LDL-C ≥ 500 mg/d. L – He. FH with LDL-C ≥ 300 mg/d. L – Functional He. FH with LDL-C ≥ 200 mg/d. L in patients with CAD • May be considered upon failure of PCSK 9 inhibitors CAD = coronary artery disease Jacobson TA, et al. J Clin Lipidol. 2014; 8(5): 473 -488.

LDL Apheresis • Indicated when patients have failed diet and maximum drug therapy from at least 2 separate classes of hypolipidemic drugs for ≥ 6 months …Plus – He. FH with LDL-C ≥ 500 mg/d. L – He. FH with LDL-C ≥ 300 mg/d. L – Functional He. FH with LDL-C ≥ 200 mg/d. L in patients with CAD • May be considered upon failure of PCSK 9 inhibitors CAD = coronary artery disease Jacobson TA, et al. J Clin Lipidol. 2014; 8(5): 473 -488.

Investigational Agent: Anacetrapib • Cholesteryl ester transfer protein (CEPT) inhibitor 1 • Phase 3 DEFINE trial (2 -year extension of 76 week base study): 1 – Anacetrapib reduced LDL-C by 39. 9% and increased HDL-C by 153. 3% vs placebo – Study is still ongoing 2 • Phase 3 REVEAL trial ongoing 2 – Goal is to determine whether lipid modification with anacetrapib 100 mg daily reduces the risk of major coronary events in patients with circulatory problems receiving statin therapy for LDL-C levels 1. Gotto AM Jr, et al. J Cardiovasc Pharmacol Ther. 2014; 19(6): 543 -549. 2. REVEAL trial. Clinical. Trials. gov Identifier: NCT 01252953. https: //clinicaltrials. gov/ct 2/show/NCT 01252953.

Investigational Agent: Anacetrapib • Cholesteryl ester transfer protein (CEPT) inhibitor 1 • Phase 3 DEFINE trial (2 -year extension of 76 week base study): 1 – Anacetrapib reduced LDL-C by 39. 9% and increased HDL-C by 153. 3% vs placebo – Study is still ongoing 2 • Phase 3 REVEAL trial ongoing 2 – Goal is to determine whether lipid modification with anacetrapib 100 mg daily reduces the risk of major coronary events in patients with circulatory problems receiving statin therapy for LDL-C levels 1. Gotto AM Jr, et al. J Cardiovasc Pharmacol Ther. 2014; 19(6): 543 -549. 2. REVEAL trial. Clinical. Trials. gov Identifier: NCT 01252953. https: //clinicaltrials. gov/ct 2/show/NCT 01252953.

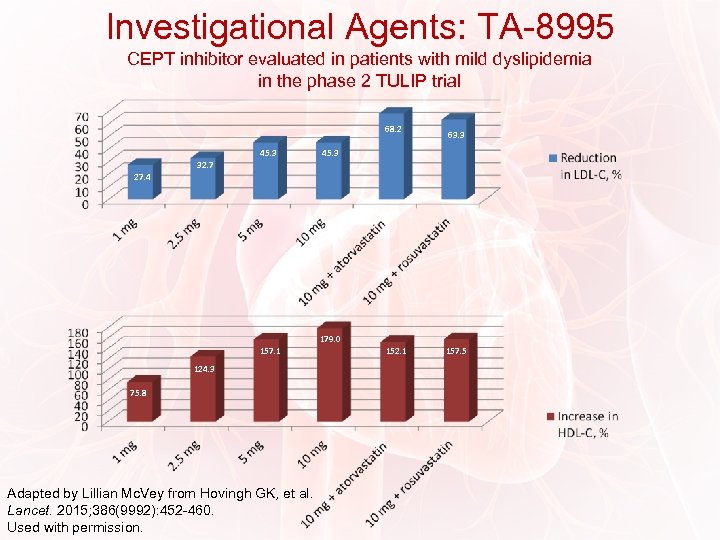

Investigational Agents: TA-8995 CEPT inhibitor evaluated in patients with mild dyslipidemia in the phase 2 TULIP trial 68. 2 45. 3 63. 3 45. 3 32. 7 27. 4 179. 0 157. 1 124. 3 75. 8 Adapted by Lillian Mc. Vey from Hovingh GK, et al. Lancet. 2015; 386(9992): 452 -460. Used with permission. 152. 1 157. 5

Investigational Agents: TA-8995 CEPT inhibitor evaluated in patients with mild dyslipidemia in the phase 2 TULIP trial 68. 2 45. 3 63. 3 45. 3 32. 7 27. 4 179. 0 157. 1 124. 3 75. 8 Adapted by Lillian Mc. Vey from Hovingh GK, et al. Lancet. 2015; 386(9992): 452 -460. Used with permission. 152. 1 157. 5

Investigational Agents: ETC-1002 • Dual adenosine triphosphate citrate lyase inhibitor/adenosine monophosphateactivated protein kinase activator • Oral, once-daily small molecule in phase 2 development • May have a modest beneficial effect on LDL-C as well as other cardiometabolic risk factors Banach M, et al. Int J Cardiol. 2016; 225: 184 -196. Nikolic D, et al. Atherosclerosis. 2014; 237(2): 705 -710.

Investigational Agents: ETC-1002 • Dual adenosine triphosphate citrate lyase inhibitor/adenosine monophosphateactivated protein kinase activator • Oral, once-daily small molecule in phase 2 development • May have a modest beneficial effect on LDL-C as well as other cardiometabolic risk factors Banach M, et al. Int J Cardiol. 2016; 225: 184 -196. Nikolic D, et al. Atherosclerosis. 2014; 237(2): 705 -710.

Case 1 • • 54 -year-old female with CAD History includes hyperlipidemia, obesity, former smoker Family history of premature CAD (mother MI at age 55) Medications: − Nebivolol 5 mg daily − Furosemide 20 mg daily − NTG 0. 4 mg SL − Rosuvastatin 2. 5 mg twice a week • Statin intolerance: pravastatin (mental cloudiness), atorvastatin (muscle aches), pitavastatin (muscle aches), rosuvastatin (muscle/joint pain) • Lipid panel: − Total cholesterol 187 mg/d. L − Triglycerides 87 mg/d. L − HDL-C 49 mg/d. L − LDL-C 121 mg/d. L

Case 1 • • 54 -year-old female with CAD History includes hyperlipidemia, obesity, former smoker Family history of premature CAD (mother MI at age 55) Medications: − Nebivolol 5 mg daily − Furosemide 20 mg daily − NTG 0. 4 mg SL − Rosuvastatin 2. 5 mg twice a week • Statin intolerance: pravastatin (mental cloudiness), atorvastatin (muscle aches), pitavastatin (muscle aches), rosuvastatin (muscle/joint pain) • Lipid panel: − Total cholesterol 187 mg/d. L − Triglycerides 87 mg/d. L − HDL-C 49 mg/d. L − LDL-C 121 mg/d. L

Case 1 (cont’d) • Evolocumab 140 mg subcutaneously every 2 weeks • 6 -week lipid panel: − − Total cholesterol 140 mg/d. L Triglycerides 85 mg/d. L HDL-C 53 mg/d. L LDL-C 70 mg/d. L • Mild nasopharyngitis; fatigue for 2 days after injection

Case 1 (cont’d) • Evolocumab 140 mg subcutaneously every 2 weeks • 6 -week lipid panel: − − Total cholesterol 140 mg/d. L Triglycerides 85 mg/d. L HDL-C 53 mg/d. L LDL-C 70 mg/d. L • Mild nasopharyngitis; fatigue for 2 days after injection

Case 2 • 30 -year-old female with hypercholesterolemia and family history of premature CAD • On simvastatin 20 mg: – Total cholesterol 334 mg/d. L – Triglycerides 124 mg/d. L – HDL-C 43 mg/d. L – LDL-C 266 mg/d. L • Uses effective birth control and doesn’t plan on becoming pregnant in the near future

Case 2 • 30 -year-old female with hypercholesterolemia and family history of premature CAD • On simvastatin 20 mg: – Total cholesterol 334 mg/d. L – Triglycerides 124 mg/d. L – HDL-C 43 mg/d. L – LDL-C 266 mg/d. L • Uses effective birth control and doesn’t plan on becoming pregnant in the near future

Case 2 (cont’d) • Statin changed to atorvastatin 80 mg daily • Counseled on heart-healthy diet and regular exercise • 8 -week lipid panel – LDL-C decreased to 172 mg/d. L (from 266 mg/d. L) • Plan to intensify healthy lifestyle changes and consider additional therapies • Subsequent LDL-C 142 mg/d. L • Is this LDL low enough?

Case 2 (cont’d) • Statin changed to atorvastatin 80 mg daily • Counseled on heart-healthy diet and regular exercise • 8 -week lipid panel – LDL-C decreased to 172 mg/d. L (from 266 mg/d. L) • Plan to intensify healthy lifestyle changes and consider additional therapies • Subsequent LDL-C 142 mg/d. L • Is this LDL low enough?

Conclusion • Abnormal LDL-C levels are a major predictor of CV outcomes in patients with ASCVD • Recent guidelines have been the impetus for a paradigm shift in ASCVD management – Focus on ASCVD risk reduction rather than specific LDL-C targets – Emphasis on statin therapy • Optimal benefit from statins diminished by: – AEs, particularly muscle symptoms – Adherence – Intolerance

Conclusion • Abnormal LDL-C levels are a major predictor of CV outcomes in patients with ASCVD • Recent guidelines have been the impetus for a paradigm shift in ASCVD management – Focus on ASCVD risk reduction rather than specific LDL-C targets – Emphasis on statin therapy • Optimal benefit from statins diminished by: – AEs, particularly muscle symptoms – Adherence – Intolerance

Conclusion (cont’d) • New PCSK 9 inhibitors provide an alternative method of reducing LDL-C and associated ASCVD risk – Effectively reduces LDL-C as monotherapy and in combination with statins – Well tolerated with a low rate of side effects and AEs – Some long-term data available (78 weeks for alirocumab) • Several promising agents currently in development – CEPT inhibitors – Dual adenosine triphosphate citrate lyase inhibitor/adenosine monophosphate-activated protein kinase activator • Advances in LDL-C pharmacotherapy will likely translate into further reductions in LDL-C and associated gains in cardiovascular outcomes

Conclusion (cont’d) • New PCSK 9 inhibitors provide an alternative method of reducing LDL-C and associated ASCVD risk – Effectively reduces LDL-C as monotherapy and in combination with statins – Well tolerated with a low rate of side effects and AEs – Some long-term data available (78 weeks for alirocumab) • Several promising agents currently in development – CEPT inhibitors – Dual adenosine triphosphate citrate lyase inhibitor/adenosine monophosphate-activated protein kinase activator • Advances in LDL-C pharmacotherapy will likely translate into further reductions in LDL-C and associated gains in cardiovascular outcomes

Please complete the post-activity survey and the activity evaluation.

Please complete the post-activity survey and the activity evaluation.

Q&A

Q&A