1ad240b34e9ddf69d89fa5f0f9d39665.ppt

- Количество слайдов: 28

Scintillation Devices As a charged particle traverses a medium it excites the atoms (or molecules) in the medium. In certain materials called scintillators a small fraction of the energy released when the atoms or molecules de-excite goes into light. ENERGY IN ® LIGHT OUT The use of materials that scintillate is one of the most common experimental techniques in physics. Used by Rutherford in his scattering experiments Scintillation light can be used to: Signal the presence of a charged particle Measure the time it takes for a charged particle to travel a known distance (“time of flight technique”) Measure energy since the amount of light is proportional to energy deposition There are lots of different types of materials that scintillate: non-organic crystals (Na. I, Cs. I, BGO) organic crystals (Anthracene) Organic plastics (see table on next page) Organic liquids (toluene, xylene) Our atmosphere (nitrogen) 880. P 20 Winter 2006 Richard Kass 1

Scintillation Devices As a charged particle traverses a medium it excites the atoms (or molecules) in the medium. In certain materials called scintillators a small fraction of the energy released when the atoms or molecules de-excite goes into light. ENERGY IN ® LIGHT OUT The use of materials that scintillate is one of the most common experimental techniques in physics. Used by Rutherford in his scattering experiments Scintillation light can be used to: Signal the presence of a charged particle Measure the time it takes for a charged particle to travel a known distance (“time of flight technique”) Measure energy since the amount of light is proportional to energy deposition There are lots of different types of materials that scintillate: non-organic crystals (Na. I, Cs. I, BGO) organic crystals (Anthracene) Organic plastics (see table on next page) Organic liquids (toluene, xylene) Our atmosphere (nitrogen) 880. P 20 Winter 2006 Richard Kass 1

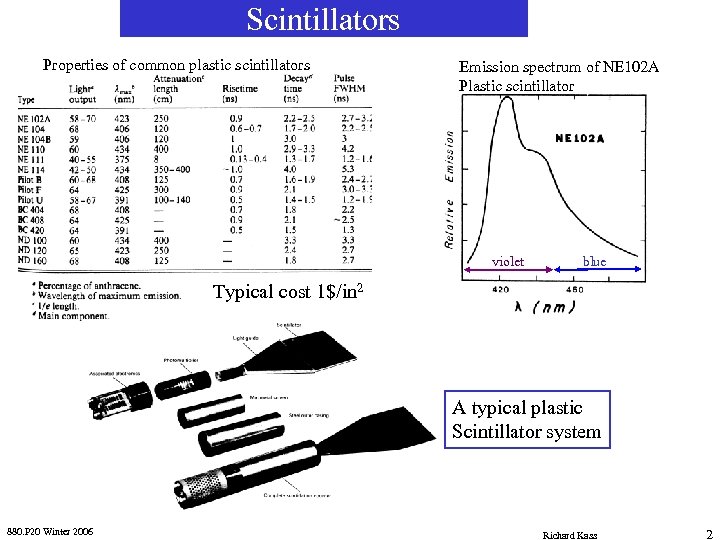

Scintillators Properties of common plastic scintillators Emission spectrum of NE 102 A Plastic scintillator violet blue Typical cost 1$/in 2 A typical plastic Scintillator system 880. P 20 Winter 2006 Richard Kass 2

Scintillators Properties of common plastic scintillators Emission spectrum of NE 102 A Plastic scintillator violet blue Typical cost 1$/in 2 A typical plastic Scintillator system 880. P 20 Winter 2006 Richard Kass 2

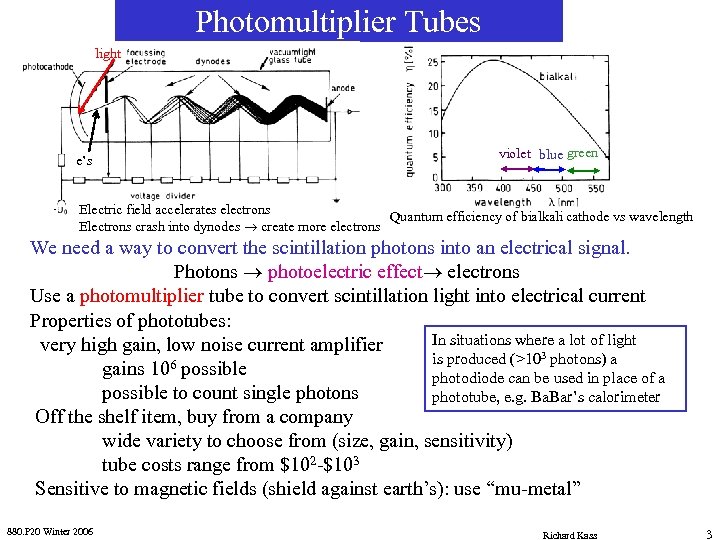

Photomultiplier Tubes light e’s violet blue green Electric field accelerates electrons Quantum efficiency of bialkali cathode vs wavelength Electrons crash into dynodes ® create more electrons We need a way to convert the scintillation photons into an electrical signal. Photons ® photoelectric effect® electrons Use a photomultiplier tube to convert scintillation light into electrical current Properties of phototubes: In situations where a lot of light very high gain, low noise current amplifier is produced (>103 photons) a 6 possible gains 10 photodiode can be used in place of a possible to count single photons phototube, e. g. Bar’s calorimeter Off the shelf item, buy from a company wide variety to choose from (size, gain, sensitivity) tube costs range from $102 -$103 Sensitive to magnetic fields (shield against earth’s): use “mu-metal” 880. P 20 Winter 2006 Richard Kass 3

Photomultiplier Tubes light e’s violet blue green Electric field accelerates electrons Quantum efficiency of bialkali cathode vs wavelength Electrons crash into dynodes ® create more electrons We need a way to convert the scintillation photons into an electrical signal. Photons ® photoelectric effect® electrons Use a photomultiplier tube to convert scintillation light into electrical current Properties of phototubes: In situations where a lot of light very high gain, low noise current amplifier is produced (>103 photons) a 6 possible gains 10 photodiode can be used in place of a possible to count single photons phototube, e. g. Bar’s calorimeter Off the shelf item, buy from a company wide variety to choose from (size, gain, sensitivity) tube costs range from $102 -$103 Sensitive to magnetic fields (shield against earth’s): use “mu-metal” 880. P 20 Winter 2006 Richard Kass 3

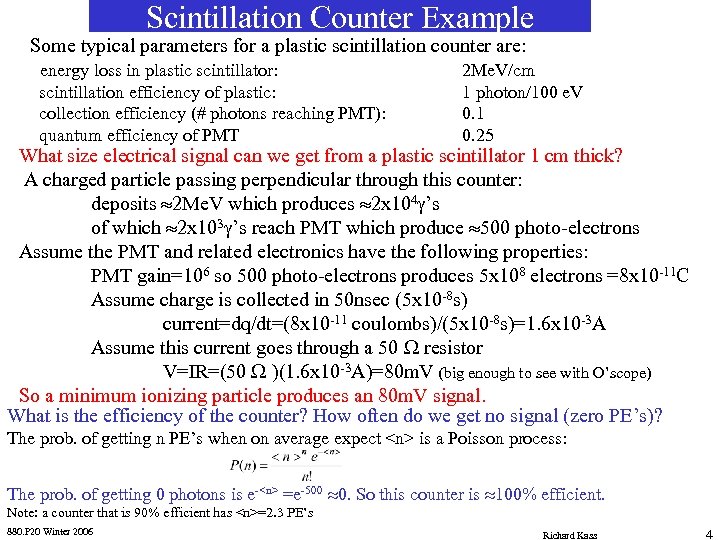

Scintillation Counter Example Some typical parameters for a plastic scintillation counter are: energy loss in plastic scintillator: scintillation efficiency of plastic: collection efficiency (# photons reaching PMT): quantum efficiency of PMT 2 Me. V/cm 1 photon/100 e. V 0. 1 0. 25 What size electrical signal can we get from a plastic scintillator 1 cm thick? A charged particle passing perpendicular through this counter: deposits » 2 Me. V which produces » 2 x 104 g’s of which » 2 x 103 g’s reach PMT which produce » 500 photo-electrons Assume the PMT and related electronics have the following properties: PMT gain=106 so 500 photo-electrons produces 5 x 108 electrons =8 x 10 -11 C Assume charge is collected in 50 nsec (5 x 10 -8 s) current=dq/dt=(8 x 10 -11 coulombs)/(5 x 10 -8 s)=1. 6 x 10 -3 A Assume this current goes through a 50 W resistor V=IR=(50 W )(1. 6 x 10 -3 A)=80 m. V (big enough to see with O’scope) So a minimum ionizing particle produces an 80 m. V signal. What is the efficiency of the counter? How often do we get no signal (zero PE’s)? The prob. of getting n PE’s when on average expect

Scintillation Counter Example Some typical parameters for a plastic scintillation counter are: energy loss in plastic scintillator: scintillation efficiency of plastic: collection efficiency (# photons reaching PMT): quantum efficiency of PMT 2 Me. V/cm 1 photon/100 e. V 0. 1 0. 25 What size electrical signal can we get from a plastic scintillator 1 cm thick? A charged particle passing perpendicular through this counter: deposits » 2 Me. V which produces » 2 x 104 g’s of which » 2 x 103 g’s reach PMT which produce » 500 photo-electrons Assume the PMT and related electronics have the following properties: PMT gain=106 so 500 photo-electrons produces 5 x 108 electrons =8 x 10 -11 C Assume charge is collected in 50 nsec (5 x 10 -8 s) current=dq/dt=(8 x 10 -11 coulombs)/(5 x 10 -8 s)=1. 6 x 10 -3 A Assume this current goes through a 50 W resistor V=IR=(50 W )(1. 6 x 10 -3 A)=80 m. V (big enough to see with O’scope) So a minimum ionizing particle produces an 80 m. V signal. What is the efficiency of the counter? How often do we get no signal (zero PE’s)? The prob. of getting n PE’s when on average expect

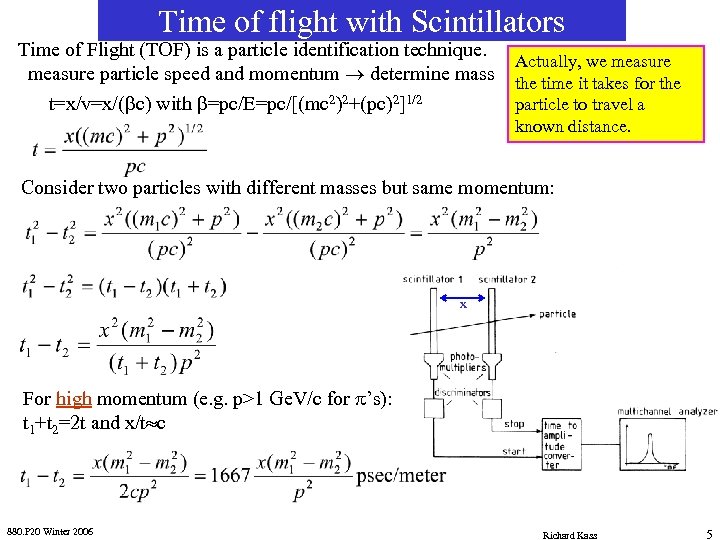

Time of flight with Scintillators Time of Flight (TOF) is a particle identification technique. measure particle speed and momentum ® determine mass t=x/v=x/(bc) with b=pc/E=pc/[(mc 2)2+(pc)2]1/2 Actually, we measure the time it takes for the particle to travel a known distance. Consider two particles with different masses but same momentum: x For high momentum (e. g. p>1 Ge. V/c for p’s): t 1+t 2=2 t and x/t» c 880. P 20 Winter 2006 Richard Kass 5

Time of flight with Scintillators Time of Flight (TOF) is a particle identification technique. measure particle speed and momentum ® determine mass t=x/v=x/(bc) with b=pc/E=pc/[(mc 2)2+(pc)2]1/2 Actually, we measure the time it takes for the particle to travel a known distance. Consider two particles with different masses but same momentum: x For high momentum (e. g. p>1 Ge. V/c for p’s): t 1+t 2=2 t and x/t» c 880. P 20 Winter 2006 Richard Kass 5

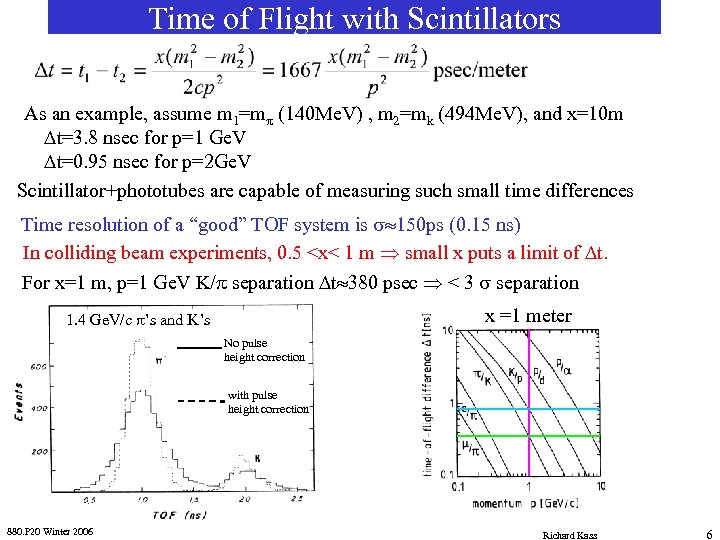

Time of Flight with Scintillators As an example, assume m 1=mp (140 Me. V) , m 2=mk (494 Me. V), and x=10 m Dt=3. 8 nsec for p=1 Ge. V Dt=0. 95 nsec for p=2 Ge. V Scintillator+phototubes are capable of measuring such small time differences Time resolution of a “good” TOF system is s» 150 ps (0. 15 ns) In colliding beam experiments, 0. 5

Time of Flight with Scintillators As an example, assume m 1=mp (140 Me. V) , m 2=mk (494 Me. V), and x=10 m Dt=3. 8 nsec for p=1 Ge. V Dt=0. 95 nsec for p=2 Ge. V Scintillator+phototubes are capable of measuring such small time differences Time resolution of a “good” TOF system is s» 150 ps (0. 15 ns) In colliding beam experiments, 0. 5

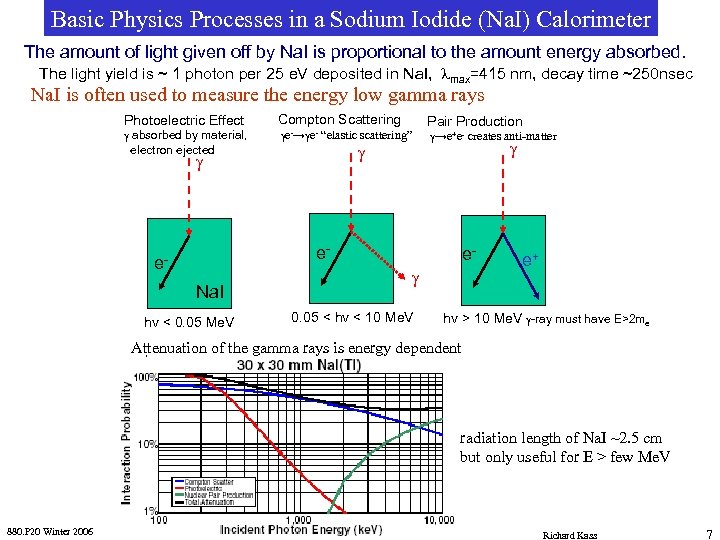

Basic Physics Processes in a Sodium Iodide (Na. I) Calorimeter The amount of light given off by Na. I is proportional to the amount energy absorbed. The light yield is ~ 1 photon per 25 e. V deposited in Na. I, lmax=415 nm, decay time ~250 nsec Na. I is often used to measure the energy low gamma rays Photoelectric Effect g absorbed by material, electron ejected Compton Scattering Pair Production ge-→ge- “elastic scattering” g→e+e- creates anti-matter g g g e- e. Na. I hv < 0. 05 Me. V eg 0. 05 < hv < 10 Me. V e+ hv > 10 Me. V g-ray must have E>2 me Attenuation of the gamma rays is energy dependent radiation length of Na. I ~2. 5 cm but only useful for E > few Me. V 880. P 20 Winter 2006 Richard Kass 7

Basic Physics Processes in a Sodium Iodide (Na. I) Calorimeter The amount of light given off by Na. I is proportional to the amount energy absorbed. The light yield is ~ 1 photon per 25 e. V deposited in Na. I, lmax=415 nm, decay time ~250 nsec Na. I is often used to measure the energy low gamma rays Photoelectric Effect g absorbed by material, electron ejected Compton Scattering Pair Production ge-→ge- “elastic scattering” g→e+e- creates anti-matter g g g e- e. Na. I hv < 0. 05 Me. V eg 0. 05 < hv < 10 Me. V e+ hv > 10 Me. V g-ray must have E>2 me Attenuation of the gamma rays is energy dependent radiation length of Na. I ~2. 5 cm but only useful for E > few Me. V 880. P 20 Winter 2006 Richard Kass 7

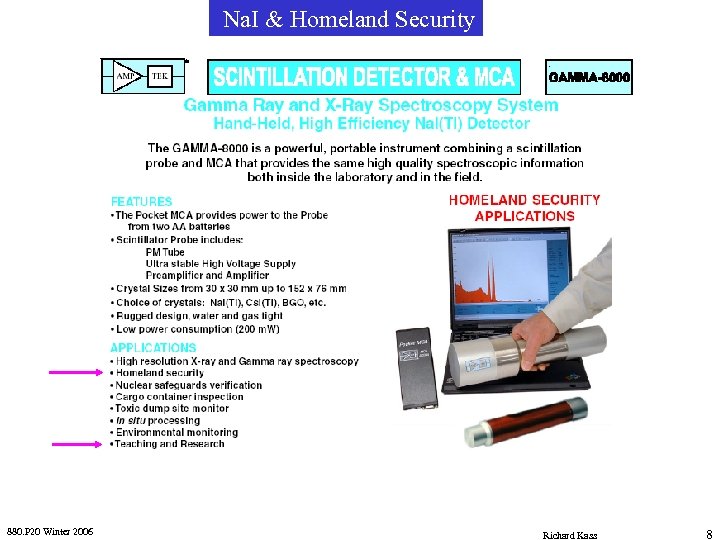

Na. I & Homeland Security 880. P 20 Winter 2006 Richard Kass 8

Na. I & Homeland Security 880. P 20 Winter 2006 Richard Kass 8

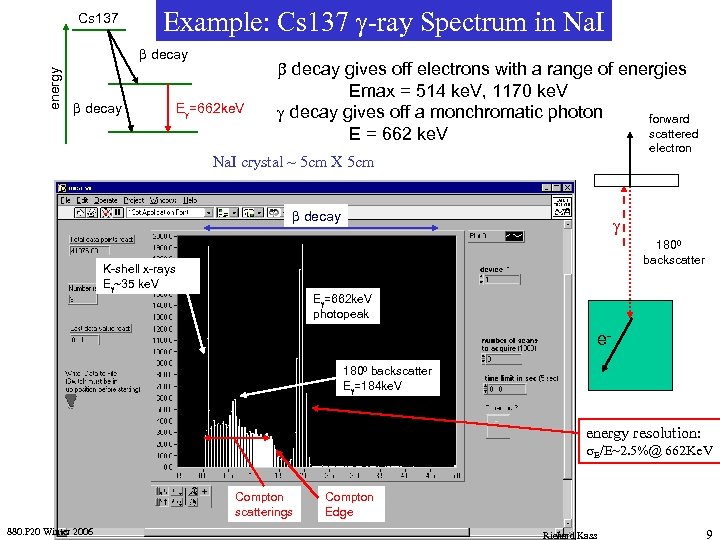

Cs 137 Example: Cs 137 g-ray Spectrum in Na. I energy b decay Eg=662 ke. V b decay gives off electrons with a range of energies Emax = 514 ke. V, 1170 ke. V g decay gives off a monchromatic photon forward scattered E = 662 ke. V electron Na. I crystal ~ 5 cm X 5 cm b decay g 1800 backscatter K-shell x-rays Eg~35 ke. V Eg=662 ke. V photopeak e 1800 backscatter Eg=184 ke. V energy resolution: s. E/E~2. 5%@ 662 Ke. V Compton scatterings 880. P 20 Winter 2006 Compton Edge Richard Kass 9

Cs 137 Example: Cs 137 g-ray Spectrum in Na. I energy b decay Eg=662 ke. V b decay gives off electrons with a range of energies Emax = 514 ke. V, 1170 ke. V g decay gives off a monchromatic photon forward scattered E = 662 ke. V electron Na. I crystal ~ 5 cm X 5 cm b decay g 1800 backscatter K-shell x-rays Eg~35 ke. V Eg=662 ke. V photopeak e 1800 backscatter Eg=184 ke. V energy resolution: s. E/E~2. 5%@ 662 Ke. V Compton scatterings 880. P 20 Winter 2006 Compton Edge Richard Kass 9

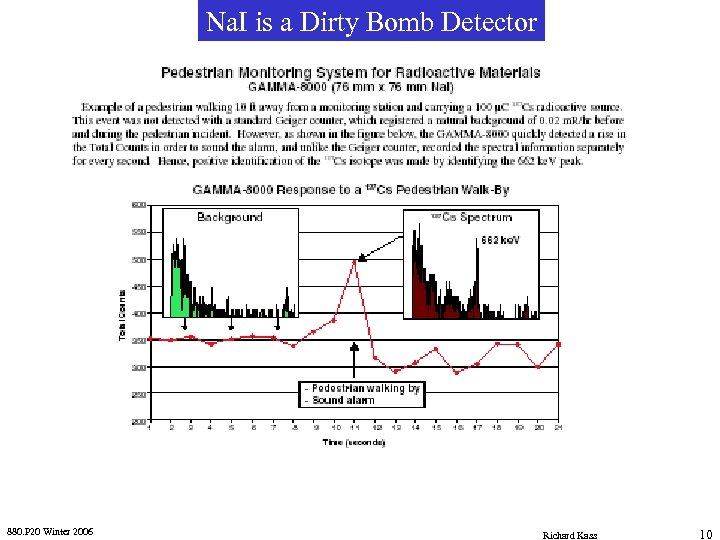

Na. I is a Dirty Bomb Detector 880. P 20 Winter 2006 Richard Kass 10

Na. I is a Dirty Bomb Detector 880. P 20 Winter 2006 Richard Kass 10

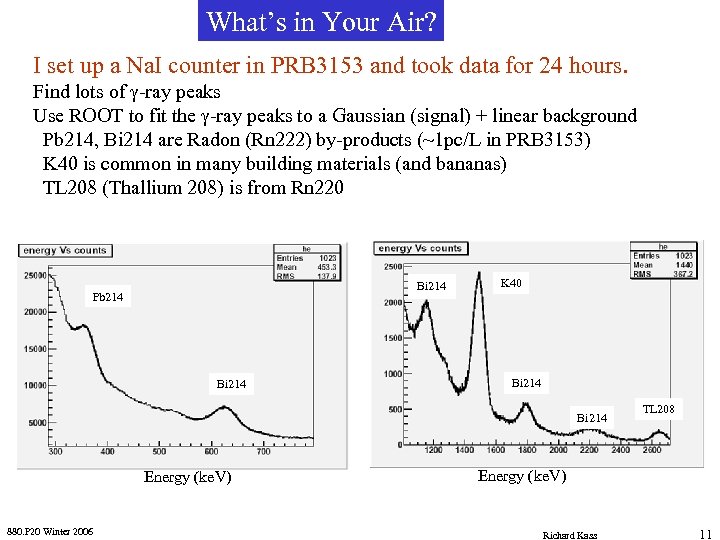

What’s in Your Air? I set up a Na. I counter in PRB 3153 and took data for 24 hours. Find lots of g-ray peaks Use ROOT to fit the g-ray peaks to a Gaussian (signal) + linear background Pb 214, Bi 214 are Radon (Rn 222) by-products (~1 pc/L in PRB 3153) K 40 is common in many building materials (and bananas) TL 208 (Thallium 208) is from Rn 220 Bi 214 Pb 214 Bi 214 K 40 Bi 214 Energy (ke. V) 880. P 20 Winter 2006 TL 208 Energy (ke. V) Richard Kass 11

What’s in Your Air? I set up a Na. I counter in PRB 3153 and took data for 24 hours. Find lots of g-ray peaks Use ROOT to fit the g-ray peaks to a Gaussian (signal) + linear background Pb 214, Bi 214 are Radon (Rn 222) by-products (~1 pc/L in PRB 3153) K 40 is common in many building materials (and bananas) TL 208 (Thallium 208) is from Rn 220 Bi 214 Pb 214 Bi 214 K 40 Bi 214 Energy (ke. V) 880. P 20 Winter 2006 TL 208 Energy (ke. V) Richard Kass 11

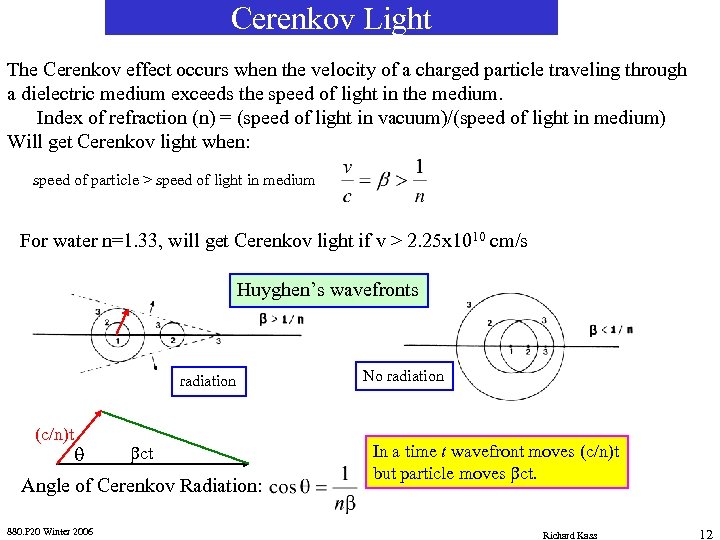

Cerenkov Light The Cerenkov effect occurs when the velocity of a charged particle traveling through a dielectric medium exceeds the speed of light in the medium. Index of refraction (n) = (speed of light in vacuum)/(speed of light in medium) Will get Cerenkov light when: speed of particle > speed of light in medium For water n=1. 33, will get Cerenkov light if v > 2. 25 x 1010 cm/s Huyghen’s wavefronts radiation (c/n)t q bct Angle of Cerenkov Radiation: 880. P 20 Winter 2006 No radiation In a time t wavefront moves (c/n)t but particle moves bct. Richard Kass 12

Cerenkov Light The Cerenkov effect occurs when the velocity of a charged particle traveling through a dielectric medium exceeds the speed of light in the medium. Index of refraction (n) = (speed of light in vacuum)/(speed of light in medium) Will get Cerenkov light when: speed of particle > speed of light in medium For water n=1. 33, will get Cerenkov light if v > 2. 25 x 1010 cm/s Huyghen’s wavefronts radiation (c/n)t q bct Angle of Cerenkov Radiation: 880. P 20 Winter 2006 No radiation In a time t wavefront moves (c/n)t but particle moves bct. Richard Kass 12

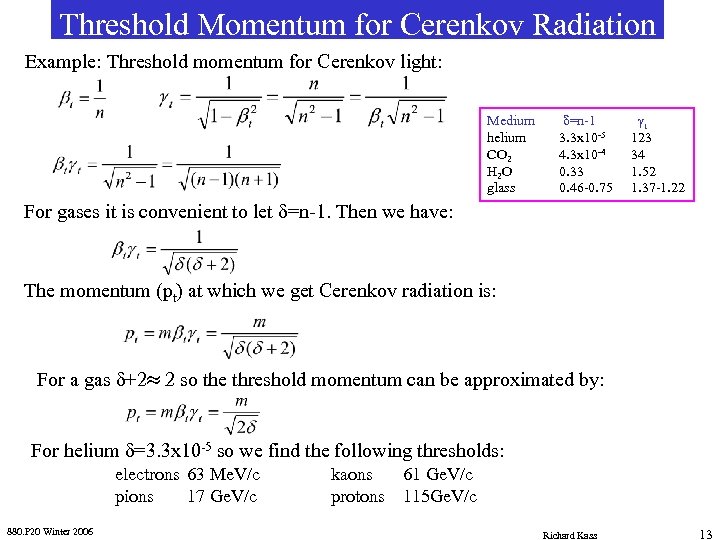

Threshold Momentum for Cerenkov Radiation Example: Threshold momentum for Cerenkov light: Medium helium CO 2 H 2 O glass d=n-1 3. 3 x 10 -5 4. 3 x 10 -4 0. 33 0. 46 -0. 75 gt 123 34 1. 52 1. 37 -1. 22 For gases it is convenient to let d=n-1. Then we have: The momentum (pt) at which we get Cerenkov radiation is: For a gas d+2» 2 so the threshold momentum can be approximated by: For helium d=3. 3 x 10 -5 so we find the following thresholds: electrons 63 Me. V/c pions 17 Ge. V/c 880. P 20 Winter 2006 kaons protons 61 Ge. V/c 115 Ge. V/c Richard Kass 13

Threshold Momentum for Cerenkov Radiation Example: Threshold momentum for Cerenkov light: Medium helium CO 2 H 2 O glass d=n-1 3. 3 x 10 -5 4. 3 x 10 -4 0. 33 0. 46 -0. 75 gt 123 34 1. 52 1. 37 -1. 22 For gases it is convenient to let d=n-1. Then we have: The momentum (pt) at which we get Cerenkov radiation is: For a gas d+2» 2 so the threshold momentum can be approximated by: For helium d=3. 3 x 10 -5 so we find the following thresholds: electrons 63 Me. V/c pions 17 Ge. V/c 880. P 20 Winter 2006 kaons protons 61 Ge. V/c 115 Ge. V/c Richard Kass 13

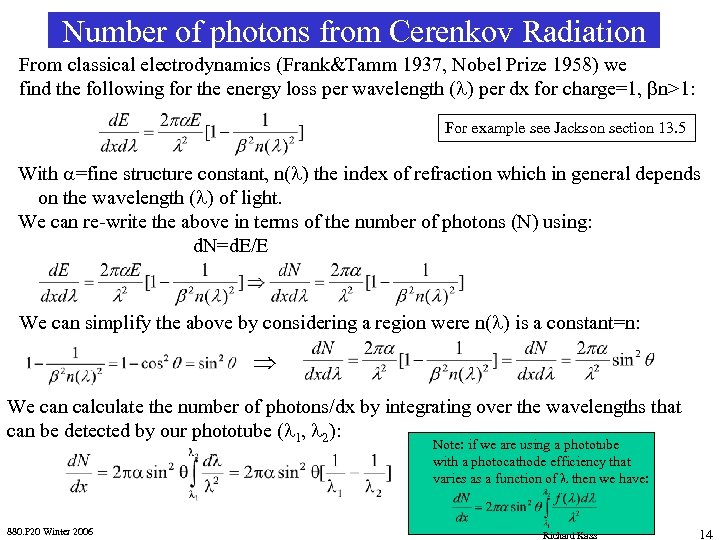

Number of photons from Cerenkov Radiation From classical electrodynamics (Frank&Tamm 1937, Nobel Prize 1958) we find the following for the energy loss per wavelength (l) per dx for charge=1, bn>1: For example see Jackson section 13. 5 With a=fine structure constant, n(l) the index of refraction which in general depends on the wavelength (l) of light. We can re-write the above in terms of the number of photons (N) using: d. N=d. E/E We can simplify the above by considering a region were n(l) is a constant=n: Þ We can calculate the number of photons/dx by integrating over the wavelengths that can be detected by our phototube (l 1, l 2): Note: if we are using a phototube with a photocathode efficiency that varies as a function of l then we have: 880. P 20 Winter 2006 Richard Kass 14

Number of photons from Cerenkov Radiation From classical electrodynamics (Frank&Tamm 1937, Nobel Prize 1958) we find the following for the energy loss per wavelength (l) per dx for charge=1, bn>1: For example see Jackson section 13. 5 With a=fine structure constant, n(l) the index of refraction which in general depends on the wavelength (l) of light. We can re-write the above in terms of the number of photons (N) using: d. N=d. E/E We can simplify the above by considering a region were n(l) is a constant=n: Þ We can calculate the number of photons/dx by integrating over the wavelengths that can be detected by our phototube (l 1, l 2): Note: if we are using a phototube with a photocathode efficiency that varies as a function of l then we have: 880. P 20 Winter 2006 Richard Kass 14

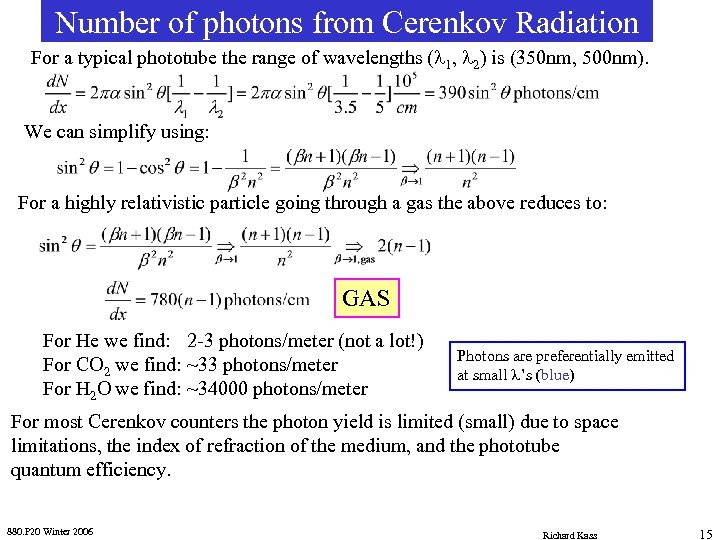

Number of photons from Cerenkov Radiation For a typical phototube the range of wavelengths (l 1, l 2) is (350 nm, 500 nm). We can simplify using: For a highly relativistic particle going through a gas the above reduces to: GAS For He we find: 2 -3 photons/meter (not a lot!) For CO 2 we find: ~33 photons/meter For H 2 O we find: ~34000 photons/meter Photons are preferentially emitted at small l’s (blue) For most Cerenkov counters the photon yield is limited (small) due to space limitations, the index of refraction of the medium, and the phototube quantum efficiency. 880. P 20 Winter 2006 Richard Kass 15

Number of photons from Cerenkov Radiation For a typical phototube the range of wavelengths (l 1, l 2) is (350 nm, 500 nm). We can simplify using: For a highly relativistic particle going through a gas the above reduces to: GAS For He we find: 2 -3 photons/meter (not a lot!) For CO 2 we find: ~33 photons/meter For H 2 O we find: ~34000 photons/meter Photons are preferentially emitted at small l’s (blue) For most Cerenkov counters the photon yield is limited (small) due to space limitations, the index of refraction of the medium, and the phototube quantum efficiency. 880. P 20 Winter 2006 Richard Kass 15

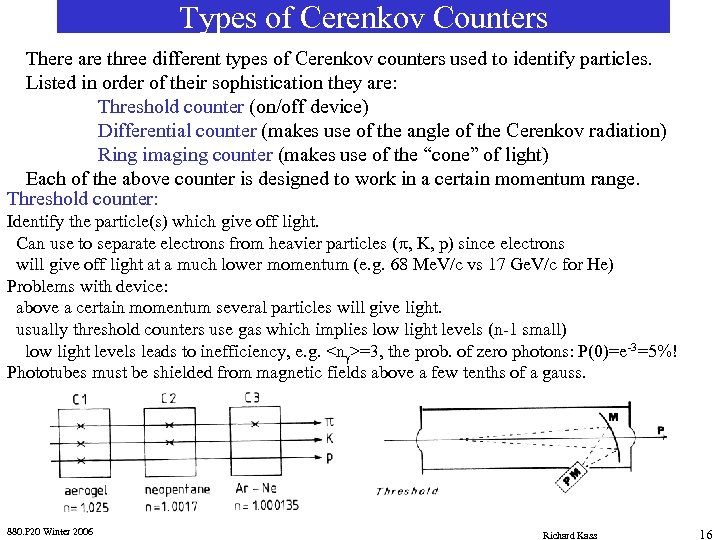

Types of Cerenkov Counters There are three different types of Cerenkov counters used to identify particles. Listed in order of their sophistication they are: Threshold counter (on/off device) Differential counter (makes use of the angle of the Cerenkov radiation) Ring imaging counter (makes use of the “cone” of light) Each of the above counter is designed to work in a certain momentum range. Threshold counter: Identify the particle(s) which give off light. Can use to separate electrons from heavier particles (p, K, p) since electrons will give off light at a much lower momentum (e. g. 68 Me. V/c vs 17 Ge. V/c for He) Problems with device: above a certain momentum several particles will give light. usually threshold counters use gas which implies low light levels (n-1 small) low light levels leads to inefficiency, e. g.

Types of Cerenkov Counters There are three different types of Cerenkov counters used to identify particles. Listed in order of their sophistication they are: Threshold counter (on/off device) Differential counter (makes use of the angle of the Cerenkov radiation) Ring imaging counter (makes use of the “cone” of light) Each of the above counter is designed to work in a certain momentum range. Threshold counter: Identify the particle(s) which give off light. Can use to separate electrons from heavier particles (p, K, p) since electrons will give off light at a much lower momentum (e. g. 68 Me. V/c vs 17 Ge. V/c for He) Problems with device: above a certain momentum several particles will give light. usually threshold counters use gas which implies low light levels (n-1 small) low light levels leads to inefficiency, e. g.

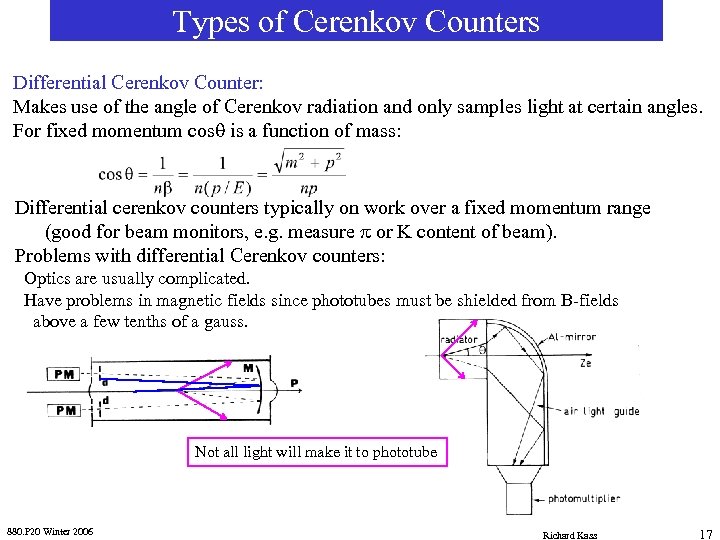

Types of Cerenkov Counters Differential Cerenkov Counter: Makes use of the angle of Cerenkov radiation and only samples light at certain angles. For fixed momentum cosq is a function of mass: Differential cerenkov counters typically on work over a fixed momentum range (good for beam monitors, e. g. measure p or K content of beam). Problems with differential Cerenkov counters: Optics are usually complicated. Have problems in magnetic fields since phototubes must be shielded from B-fields above a few tenths of a gauss. Not all light will make it to phototube 880. P 20 Winter 2006 Richard Kass 17

Types of Cerenkov Counters Differential Cerenkov Counter: Makes use of the angle of Cerenkov radiation and only samples light at certain angles. For fixed momentum cosq is a function of mass: Differential cerenkov counters typically on work over a fixed momentum range (good for beam monitors, e. g. measure p or K content of beam). Problems with differential Cerenkov counters: Optics are usually complicated. Have problems in magnetic fields since phototubes must be shielded from B-fields above a few tenths of a gauss. Not all light will make it to phototube 880. P 20 Winter 2006 Richard Kass 17

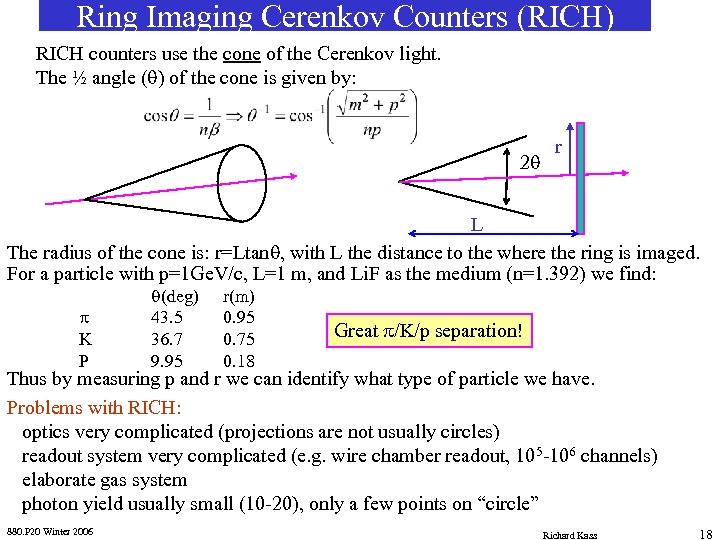

Ring Imaging Cerenkov Counters (RICH) RICH counters use the cone of the Cerenkov light. The ½ angle (q) of the cone is given by: 2 q r L The radius of the cone is: r=Ltanq, with L the distance to the where the ring is imaged. For a particle with p=1 Ge. V/c, L=1 m, and Li. F as the medium (n=1. 392) we find: p K P q(deg) 43. 5 36. 7 9. 95 r(m) 0. 95 0. 75 0. 18 Great p/K/p separation! Thus by measuring p and r we can identify what type of particle we have. Problems with RICH: optics very complicated (projections are not usually circles) readout system very complicated (e. g. wire chamber readout, 105 -106 channels) elaborate gas system photon yield usually small (10 -20), only a few points on “circle” 880. P 20 Winter 2006 Richard Kass 18

Ring Imaging Cerenkov Counters (RICH) RICH counters use the cone of the Cerenkov light. The ½ angle (q) of the cone is given by: 2 q r L The radius of the cone is: r=Ltanq, with L the distance to the where the ring is imaged. For a particle with p=1 Ge. V/c, L=1 m, and Li. F as the medium (n=1. 392) we find: p K P q(deg) 43. 5 36. 7 9. 95 r(m) 0. 95 0. 75 0. 18 Great p/K/p separation! Thus by measuring p and r we can identify what type of particle we have. Problems with RICH: optics very complicated (projections are not usually circles) readout system very complicated (e. g. wire chamber readout, 105 -106 channels) elaborate gas system photon yield usually small (10 -20), only a few points on “circle” 880. P 20 Winter 2006 Richard Kass 18

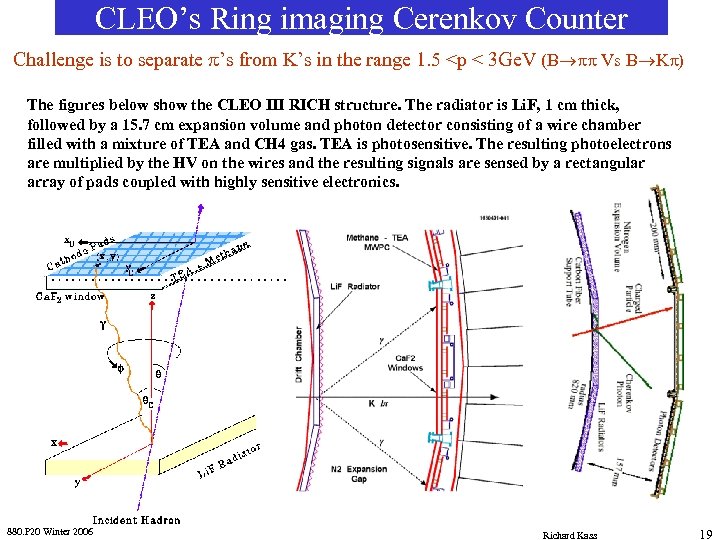

CLEO’s Ring imaging Cerenkov Counter Challenge is to separate p’s from K’s in the range 1. 5

CLEO’s Ring imaging Cerenkov Counter Challenge is to separate p’s from K’s in the range 1. 5

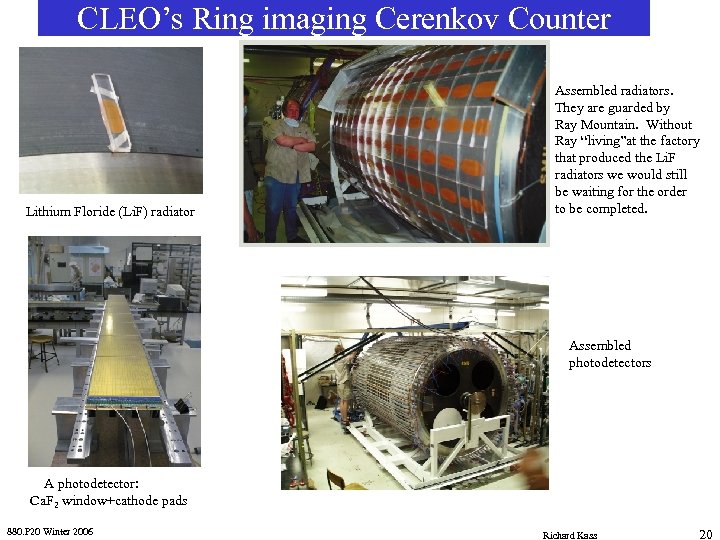

CLEO’s Ring imaging Cerenkov Counter Lithium Floride (Li. F) radiator Assembled radiators. They are guarded by Ray Mountain. Without Ray “living”at the factory that produced the Li. F radiators we would still be waiting for the order to be completed. Assembled photodetectors A photodetector: Ca. F 2 window+cathode pads 880. P 20 Winter 2006 Richard Kass 20

CLEO’s Ring imaging Cerenkov Counter Lithium Floride (Li. F) radiator Assembled radiators. They are guarded by Ray Mountain. Without Ray “living”at the factory that produced the Li. F radiators we would still be waiting for the order to be completed. Assembled photodetectors A photodetector: Ca. F 2 window+cathode pads 880. P 20 Winter 2006 Richard Kass 20

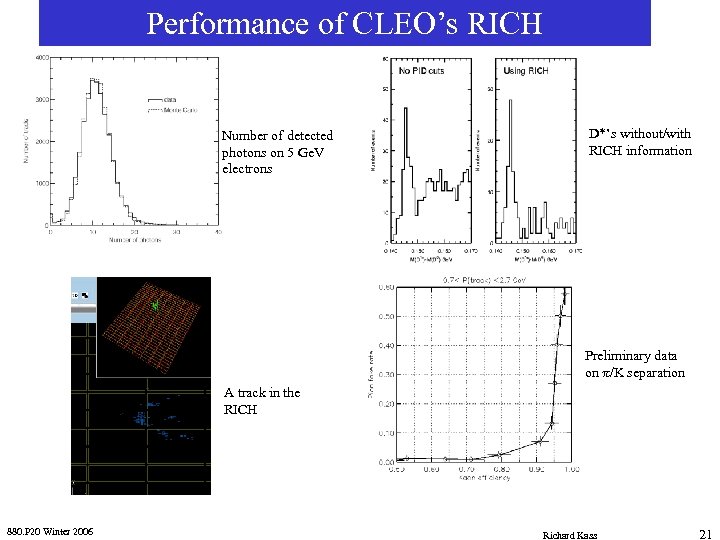

Performance of CLEO’s RICH Number of detected photons on 5 Ge. V electrons D*’s without/with RICH information Preliminary data on p/K separation A track in the RICH 880. P 20 Winter 2006 Richard Kass 21

Performance of CLEO’s RICH Number of detected photons on 5 Ge. V electrons D*’s without/with RICH information Preliminary data on p/K separation A track in the RICH 880. P 20 Winter 2006 Richard Kass 21

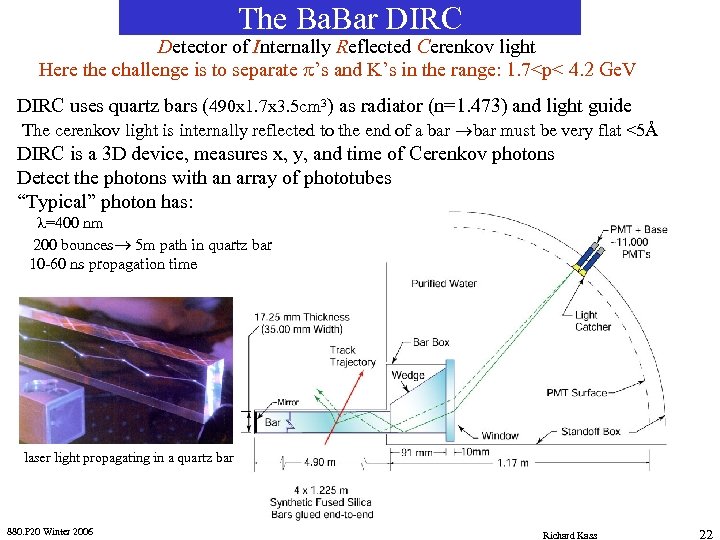

The Ba. Bar DIRC Detector of Internally Reflected Cerenkov light Here the challenge is to separate p’s and K’s in the range: 1. 7

The Ba. Bar DIRC Detector of Internally Reflected Cerenkov light Here the challenge is to separate p’s and K’s in the range: 1. 7

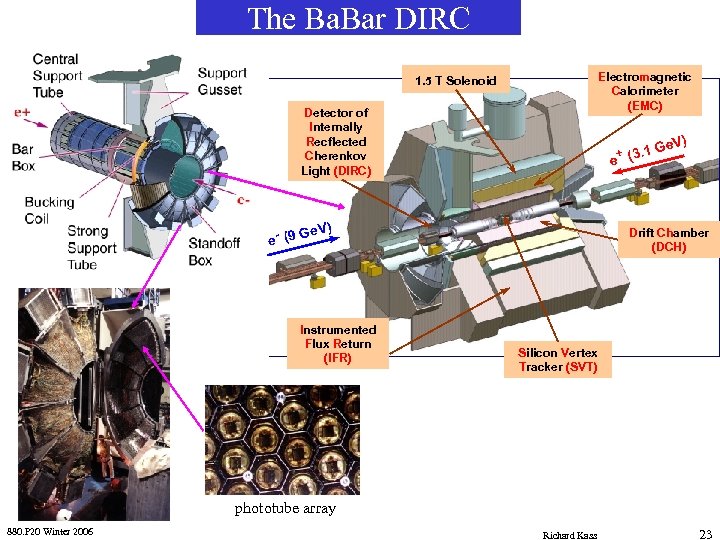

The Ba. Bar DIRC Electromagnetic Calorimeter (EMC) 1. 5 T Solenoid Detector of Internally Recflected Cherenkov Light (DIRC) e. V + (3. 1 G e V) Ge e (9 Instrumented Flux Return (IFR) ) Drift Chamber (DCH) Silicon Vertex Tracker (SVT) phototube array 880. P 20 Winter 2006 Richard Kass 23

The Ba. Bar DIRC Electromagnetic Calorimeter (EMC) 1. 5 T Solenoid Detector of Internally Recflected Cherenkov Light (DIRC) e. V + (3. 1 G e V) Ge e (9 Instrumented Flux Return (IFR) ) Drift Chamber (DCH) Silicon Vertex Tracker (SVT) phototube array 880. P 20 Winter 2006 Richard Kass 23

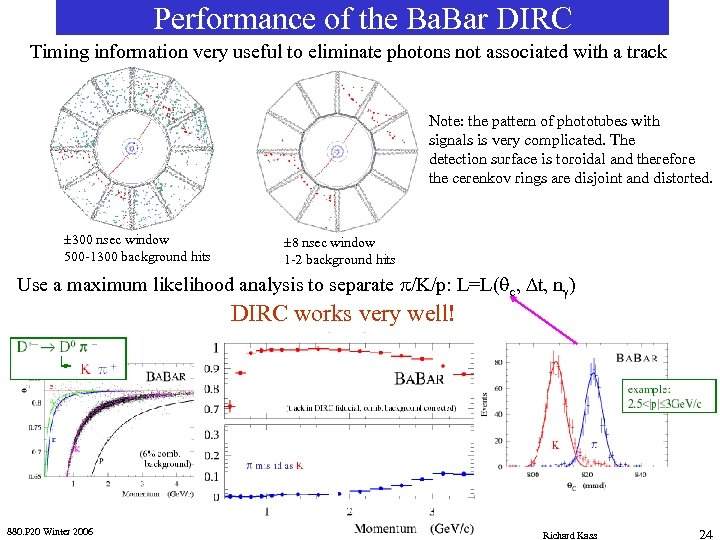

Performance of the Ba. Bar DIRC Timing information very useful to eliminate photons not associated with a track Note: the pattern of phototubes with signals is very complicated. The detection surface is toroidal and therefore the cerenkov rings are disjoint and distorted. ± 300 nsec window 500 -1300 background hits ± 8 nsec window 1 -2 background hits Use a maximum likelihood analysis to separate p/K/p: L=L(qc, Dt, ng) DIRC works very well! 880. P 20 Winter 2006 Richard Kass 24

Performance of the Ba. Bar DIRC Timing information very useful to eliminate photons not associated with a track Note: the pattern of phototubes with signals is very complicated. The detection surface is toroidal and therefore the cerenkov rings are disjoint and distorted. ± 300 nsec window 500 -1300 background hits ± 8 nsec window 1 -2 background hits Use a maximum likelihood analysis to separate p/K/p: L=L(qc, Dt, ng) DIRC works very well! 880. P 20 Winter 2006 Richard Kass 24

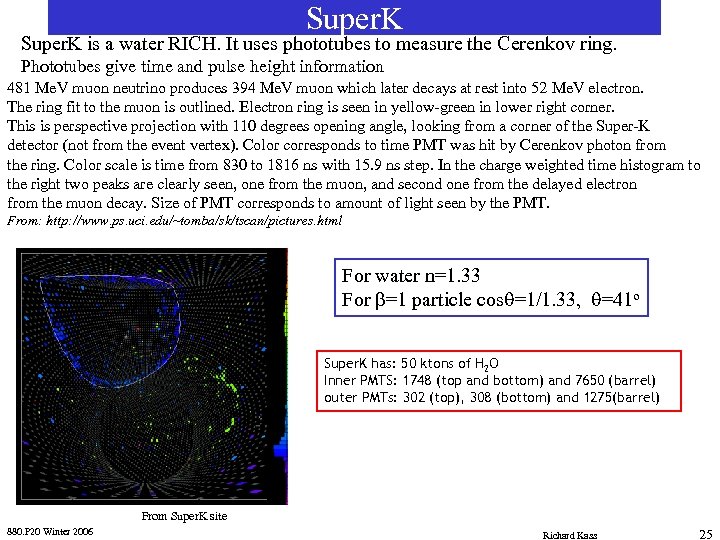

Super. K is a water RICH. It uses phototubes to measure the Cerenkov ring. Phototubes give time and pulse height information 481 Me. V muon neutrino produces 394 Me. V muon which later decays at rest into 52 Me. V electron. The ring fit to the muon is outlined. Electron ring is seen in yellow-green in lower right corner. This is perspective projection with 110 degrees opening angle, looking from a corner of the Super-K detector (not from the event vertex). Color corresponds to time PMT was hit by Cerenkov photon from the ring. Color scale is time from 830 to 1816 ns with 15. 9 ns step. In the charge weighted time histogram to the right two peaks are clearly seen, one from the muon, and second one from the delayed electron from the muon decay. Size of PMT corresponds to amount of light seen by the PMT. From: http: //www. ps. uci. edu/~tomba/sk/tscan/pictures. html For water n=1. 33 For b=1 particle cosq=1/1. 33, q=41 o Super. K has: 50 ktons of H 2 O Inner PMTS: 1748 (top and bottom) and 7650 (barrel) outer PMTs: 302 (top), 308 (bottom) and 1275(barrel) From Super. K site 880. P 20 Winter 2006 Richard Kass 25

Super. K is a water RICH. It uses phototubes to measure the Cerenkov ring. Phototubes give time and pulse height information 481 Me. V muon neutrino produces 394 Me. V muon which later decays at rest into 52 Me. V electron. The ring fit to the muon is outlined. Electron ring is seen in yellow-green in lower right corner. This is perspective projection with 110 degrees opening angle, looking from a corner of the Super-K detector (not from the event vertex). Color corresponds to time PMT was hit by Cerenkov photon from the ring. Color scale is time from 830 to 1816 ns with 15. 9 ns step. In the charge weighted time histogram to the right two peaks are clearly seen, one from the muon, and second one from the delayed electron from the muon decay. Size of PMT corresponds to amount of light seen by the PMT. From: http: //www. ps. uci. edu/~tomba/sk/tscan/pictures. html For water n=1. 33 For b=1 particle cosq=1/1. 33, q=41 o Super. K has: 50 ktons of H 2 O Inner PMTS: 1748 (top and bottom) and 7650 (barrel) outer PMTs: 302 (top), 308 (bottom) and 1275(barrel) From Super. K site 880. P 20 Winter 2006 Richard Kass 25

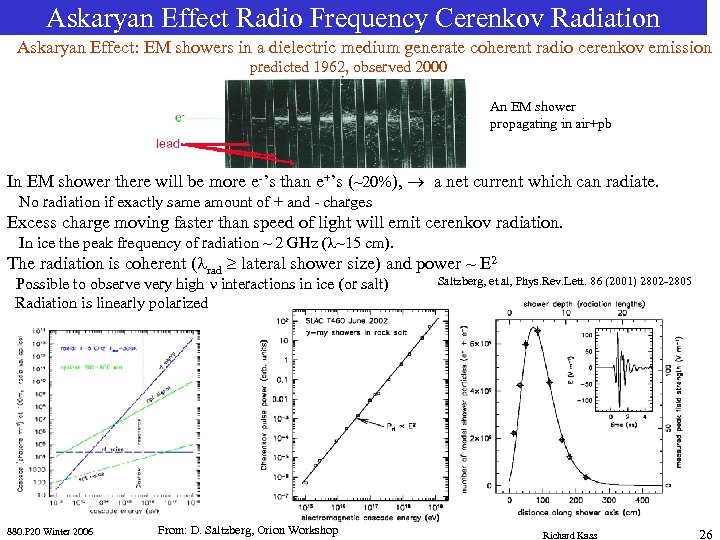

Askaryan Effect Radio Frequency Cerenkov Radiation Askaryan Effect: EM showers in a dielectric medium generate coherent radio cerenkov emission predicted 1962, observed 2000 An EM shower propagating in air+pb In EM shower there will be more e-’s than e+’s (~20%), ® a net current which can radiate. No radiation if exactly same amount of + and - charges Excess charge moving faster than speed of light will emit cerenkov radiation. In ice the peak frequency of radiation ~ 2 GHz (l~15 cm). The radiation is coherent (lrad ³ lateral shower size) and power ~ E 2 Possible to observe very high n interactions in ice (or salt) Radiation is linearly polarized 880. P 20 Winter 2006 From: D. Saltzberg, Orion Workshop Saltzberg, et al, Phys. Rev. Lett. 86 (2001) 2802 -2805 Richard Kass 26

Askaryan Effect Radio Frequency Cerenkov Radiation Askaryan Effect: EM showers in a dielectric medium generate coherent radio cerenkov emission predicted 1962, observed 2000 An EM shower propagating in air+pb In EM shower there will be more e-’s than e+’s (~20%), ® a net current which can radiate. No radiation if exactly same amount of + and - charges Excess charge moving faster than speed of light will emit cerenkov radiation. In ice the peak frequency of radiation ~ 2 GHz (l~15 cm). The radiation is coherent (lrad ³ lateral shower size) and power ~ E 2 Possible to observe very high n interactions in ice (or salt) Radiation is linearly polarized 880. P 20 Winter 2006 From: D. Saltzberg, Orion Workshop Saltzberg, et al, Phys. Rev. Lett. 86 (2001) 2802 -2805 Richard Kass 26

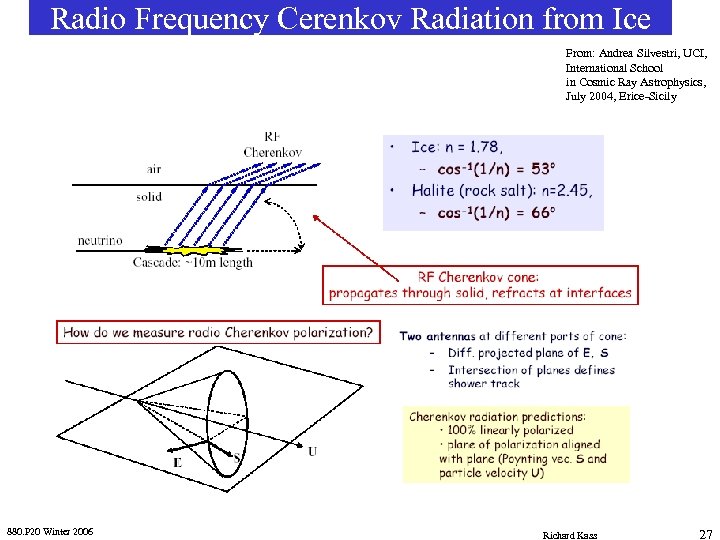

Radio Frequency Cerenkov Radiation from Ice From: Andrea Silvestri, UCI, International School in Cosmic Ray Astrophysics, July 2004, Erice-Sicily 880. P 20 Winter 2006 Richard Kass 27

Radio Frequency Cerenkov Radiation from Ice From: Andrea Silvestri, UCI, International School in Cosmic Ray Astrophysics, July 2004, Erice-Sicily 880. P 20 Winter 2006 Richard Kass 27

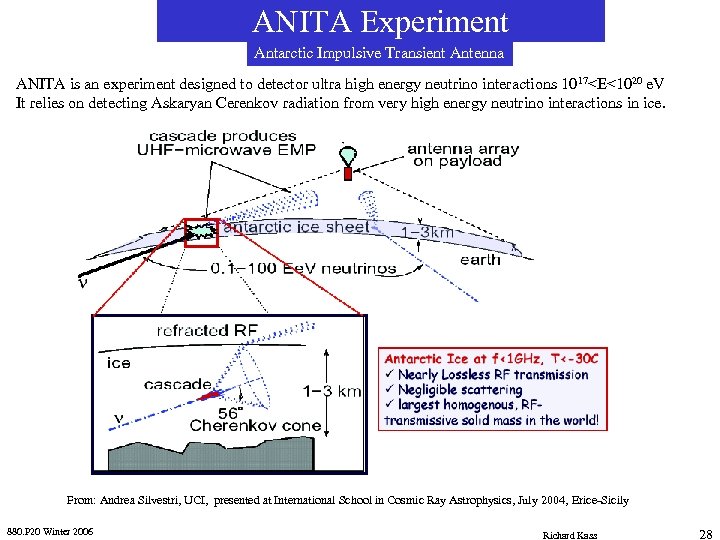

ANITA Experiment Antarctic Impulsive Transient Antenna ANITA is an experiment designed to detector ultra high energy neutrino interactions 1017

ANITA Experiment Antarctic Impulsive Transient Antenna ANITA is an experiment designed to detector ultra high energy neutrino interactions 1017