9008e848ff5595bc426ce8911806f0d8.ppt

- Количество слайдов: 92

School Suicide Prevention, Intervention and Postvention La. Shante Smith, CSUS graduate student, Crystal Courtright, CSUS graduate student, Stephen E. Brock, Ph. D, NCSP, LEP California State University, Sacramento brock@csus. edu 1

School Suicide Prevention, Intervention and Postvention La. Shante Smith, CSUS graduate student, Crystal Courtright, CSUS graduate student, Stephen E. Brock, Ph. D, NCSP, LEP California State University, Sacramento brock@csus. edu 1

Presentation Outline Introduction ◦ Suicide Statistics Primary Prevention of Suicide Secondary Prevention of Suicide ◦ General Staff Procedures ◦ Risk Assessment and Referral Protocol Suicide Postvention 2

Presentation Outline Introduction ◦ Suicide Statistics Primary Prevention of Suicide Secondary Prevention of Suicide ◦ General Staff Procedures ◦ Risk Assessment and Referral Protocol Suicide Postvention 2

National Youth Suicide Statistics Fifth leading cause of death among 5 -14 year olds in 2009 (N = 266; 0. 7: 100, 000). ◦ Third leading cause in the 10 -14 age group, N = 259). Third leading cause of death among 15 -24 year olds in 2009 (N = 4, 371; 10. 1: 100, 000). Source: Kochanek, K. D. , et al. (2011, March). Deaths: Preliminary data for 2009. National Vital Statistics Report, 59(4), 1 -51. Retrieved from http: //www. cdc. gov/nchs/data/nvsr 59/nvsr 59_04. pdf 3

National Youth Suicide Statistics Fifth leading cause of death among 5 -14 year olds in 2009 (N = 266; 0. 7: 100, 000). ◦ Third leading cause in the 10 -14 age group, N = 259). Third leading cause of death among 15 -24 year olds in 2009 (N = 4, 371; 10. 1: 100, 000). Source: Kochanek, K. D. , et al. (2011, March). Deaths: Preliminary data for 2009. National Vital Statistics Report, 59(4), 1 -51. Retrieved from http: //www. cdc. gov/nchs/data/nvsr 59/nvsr 59_04. pdf 3

National Youth Suicide Statistics 2011 YRBS 1 ◦ 15. 8% of high school students reported having seriously considered suicide. ◦ 12. 8% reported having made a suicide plan. ◦ 7. 8% of high school students reported having attempted suicide. ◦ 2. 4% indicated that the attempt required medical attention. 100 to 200 attempts for each completed youth suicide. ◦ vs. 4 attempts for each completed suicide among the elderly. 2 1 Eaton, D. K. et al. (2012, June). Youth Risk Behavior Surveillance — United States, 2011. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report, 61(SS-4), 1 -162. Retrieved from http: //www. cdc. gov/mmwr/pdf/ss/ss 6104. pdf 2 Mc. Intosh, J. L. (2011, October). USA suicide: 2008 final data. Washington, DC: American Association of Suicideology. Retrieved from http: //www. suicidology. org/c/document_library/get_file? folder. Id=228&name=DLFE-392. pdf 4

National Youth Suicide Statistics 2011 YRBS 1 ◦ 15. 8% of high school students reported having seriously considered suicide. ◦ 12. 8% reported having made a suicide plan. ◦ 7. 8% of high school students reported having attempted suicide. ◦ 2. 4% indicated that the attempt required medical attention. 100 to 200 attempts for each completed youth suicide. ◦ vs. 4 attempts for each completed suicide among the elderly. 2 1 Eaton, D. K. et al. (2012, June). Youth Risk Behavior Surveillance — United States, 2011. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report, 61(SS-4), 1 -162. Retrieved from http: //www. cdc. gov/mmwr/pdf/ss/ss 6104. pdf 2 Mc. Intosh, J. L. (2011, October). USA suicide: 2008 final data. Washington, DC: American Association of Suicideology. Retrieved from http: //www. suicidology. org/c/document_library/get_file? folder. Id=228&name=DLFE-392. pdf 4

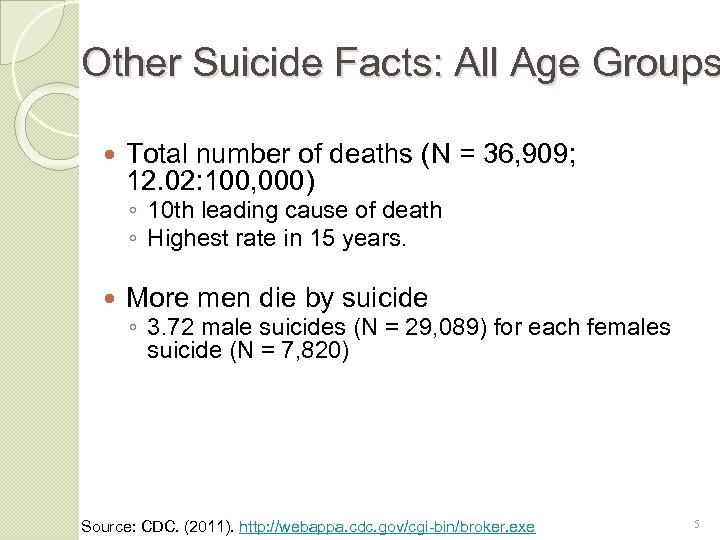

Other Suicide Facts: All Age Groups Total number of deaths (N = 36, 909; 12. 02: 100, 000) ◦ 10 th leading cause of death ◦ Highest rate in 15 years. More men die by suicide ◦ 3. 72 male suicides (N = 29, 089) for each females suicide (N = 7, 820) Source: CDC. (2011). http: //webappa. cdc. gov/cgi-bin/broker. exe 5

Other Suicide Facts: All Age Groups Total number of deaths (N = 36, 909; 12. 02: 100, 000) ◦ 10 th leading cause of death ◦ Highest rate in 15 years. More men die by suicide ◦ 3. 72 male suicides (N = 29, 089) for each females suicide (N = 7, 820) Source: CDC. (2011). http: //webappa. cdc. gov/cgi-bin/broker. exe 5

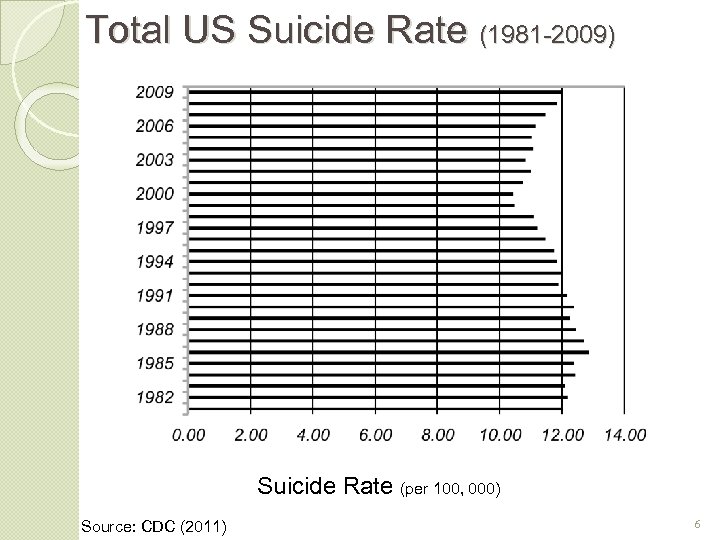

Total US Suicide Rate (1981 -2009) Suicide Rate (per 100, 000) Source: CDC (2011) 6

Total US Suicide Rate (1981 -2009) Suicide Rate (per 100, 000) Source: CDC (2011) 6

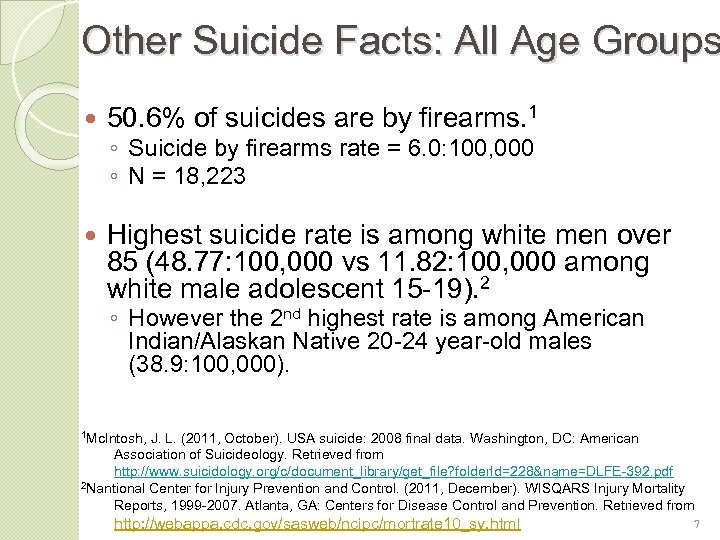

Other Suicide Facts: All Age Groups 50. 6% of suicides are by firearms. 1 Highest suicide rate is among white men over 85 (48. 77: 100, 000 vs 11. 82: 100, 000 among white male adolescent 15 -19). 2 ◦ Suicide by firearms rate = 6. 0: 100, 000 ◦ N = 18, 223 ◦ However the 2 nd highest rate is among American Indian/Alaskan Native 20 -24 year-old males (38. 9: 100, 000). 1 Mc. Intosh, J. L. (2011, October). USA suicide: 2008 final data. Washington, DC: American Association of Suicideology. Retrieved from http: //www. suicidology. org/c/document_library/get_file? folder. Id=228&name=DLFE-392. pdf 2 Nantional Center for Injury Prevention and Control. (2011, December). WISQARS Injury Mortality Reports, 1999 -2007. Atlanta, GA: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Retrieved from http: //webappa. cdc. gov/sasweb/ncipc/mortrate 10_sy. html 7

Other Suicide Facts: All Age Groups 50. 6% of suicides are by firearms. 1 Highest suicide rate is among white men over 85 (48. 77: 100, 000 vs 11. 82: 100, 000 among white male adolescent 15 -19). 2 ◦ Suicide by firearms rate = 6. 0: 100, 000 ◦ N = 18, 223 ◦ However the 2 nd highest rate is among American Indian/Alaskan Native 20 -24 year-old males (38. 9: 100, 000). 1 Mc. Intosh, J. L. (2011, October). USA suicide: 2008 final data. Washington, DC: American Association of Suicideology. Retrieved from http: //www. suicidology. org/c/document_library/get_file? folder. Id=228&name=DLFE-392. pdf 2 Nantional Center for Injury Prevention and Control. (2011, December). WISQARS Injury Mortality Reports, 1999 -2007. Atlanta, GA: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Retrieved from http: //webappa. cdc. gov/sasweb/ncipc/mortrate 10_sy. html 7

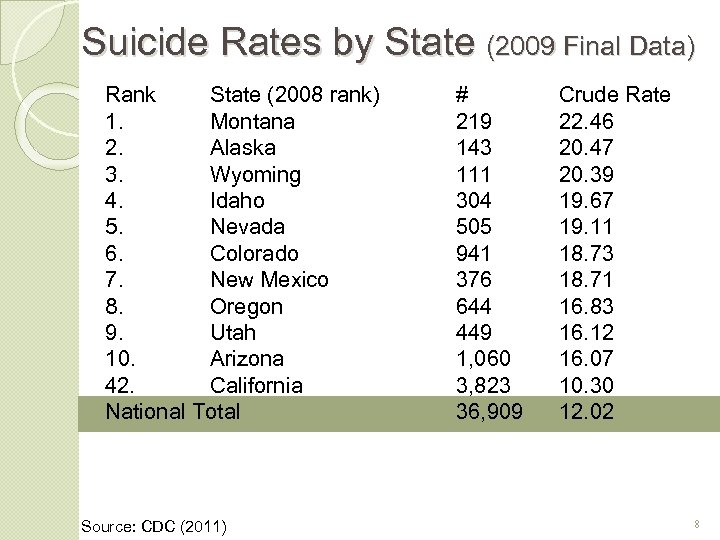

Suicide Rates by State (2009 Final Data) Rank State (2008 rank) 1. Montana 2. Alaska 3. Wyoming 4. Idaho 5. Nevada 6. Colorado 7. New Mexico 8. Oregon 9. Utah 10. Arizona 42. California National Total Source: CDC (2011) # 219 143 111 304 505 941 376 644 449 1, 060 3, 823 36, 909 Crude Rate 22. 46 20. 47 20. 39 19. 67 19. 11 18. 73 18. 71 16. 83 16. 12 16. 07 10. 30 12. 02 8

Suicide Rates by State (2009 Final Data) Rank State (2008 rank) 1. Montana 2. Alaska 3. Wyoming 4. Idaho 5. Nevada 6. Colorado 7. New Mexico 8. Oregon 9. Utah 10. Arizona 42. California National Total Source: CDC (2011) # 219 143 111 304 505 941 376 644 449 1, 060 3, 823 36, 909 Crude Rate 22. 46 20. 47 20. 39 19. 67 19. 11 18. 73 18. 71 16. 83 16. 12 16. 07 10. 30 12. 02 8

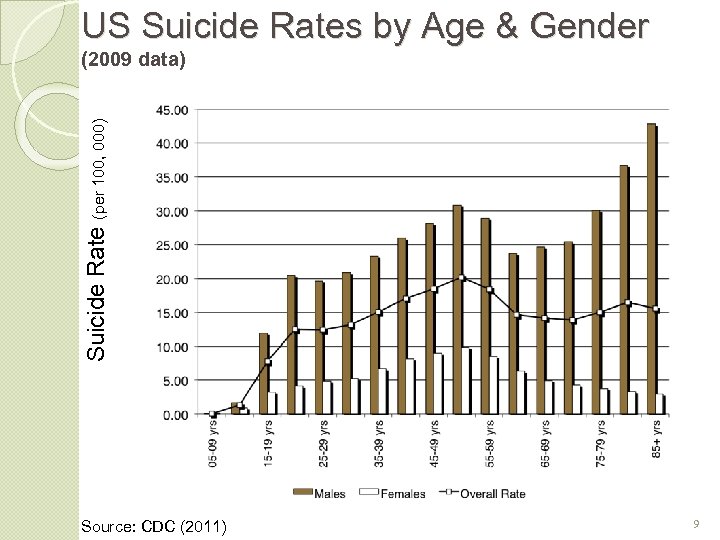

US Suicide Rates by Age & Gender Suicide Rate (per 100, 000) (2009 data) Source: CDC (2011) 9

US Suicide Rates by Age & Gender Suicide Rate (per 100, 000) (2009 data) Source: CDC (2011) 9

Youth Risk Behavior Survey - 2011 • During the 12 months before the survey, what percentage of students engaged in a variety of risky behaviors 10

Youth Risk Behavior Survey - 2011 • During the 12 months before the survey, what percentage of students engaged in a variety of risky behaviors 10

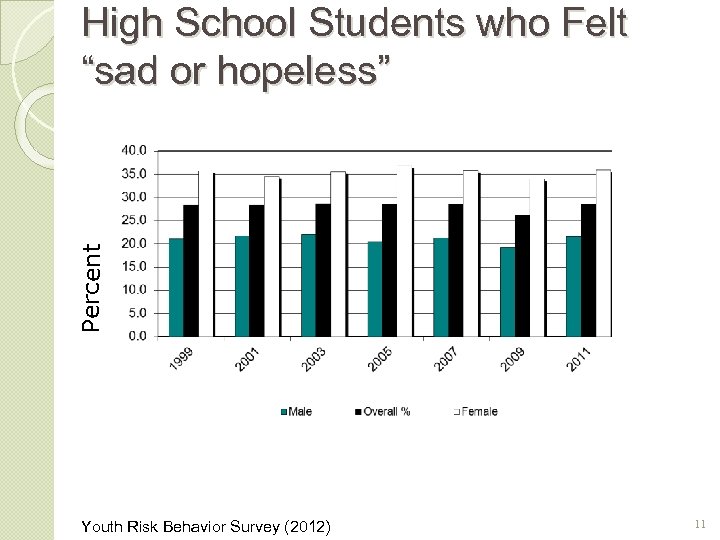

Percent High School Students who Felt “sad or hopeless” Youth Risk Behavior Survey (2012) 11

Percent High School Students who Felt “sad or hopeless” Youth Risk Behavior Survey (2012) 11

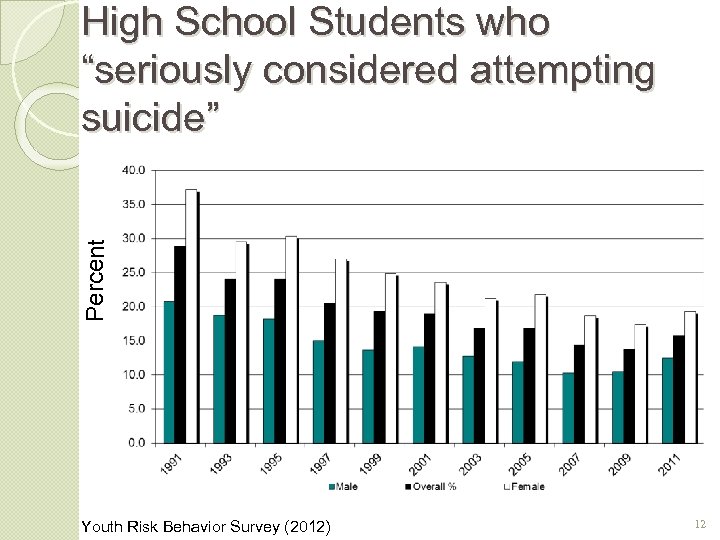

Percent High School Students who “seriously considered attempting suicide” Youth Risk Behavior Survey (2012) 12

Percent High School Students who “seriously considered attempting suicide” Youth Risk Behavior Survey (2012) 12

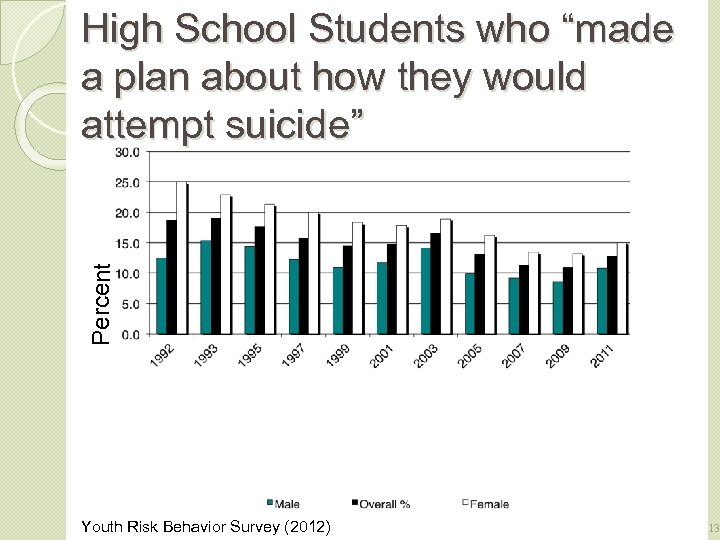

Percent High School Students who “made a plan about how they would attempt suicide” Youth Risk Behavior Survey (2012) 13 13

Percent High School Students who “made a plan about how they would attempt suicide” Youth Risk Behavior Survey (2012) 13 13

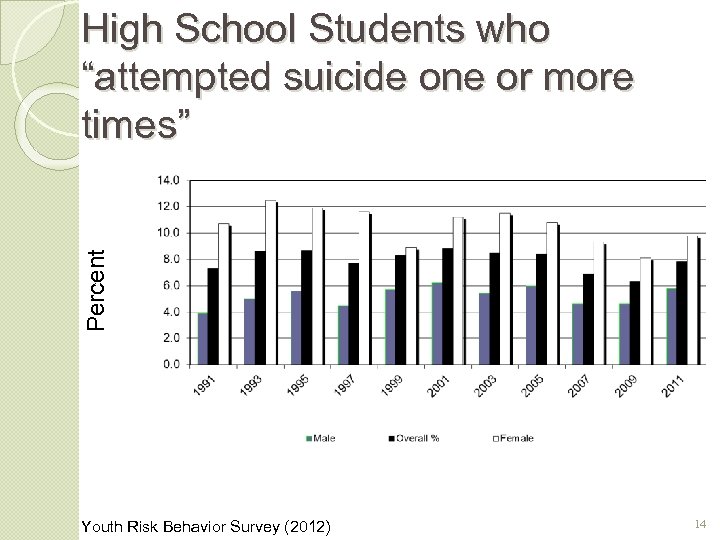

Percent High School Students who “attempted suicide one or more times” Youth Risk Behavior Survey (2012) 14

Percent High School Students who “attempted suicide one or more times” Youth Risk Behavior Survey (2012) 14

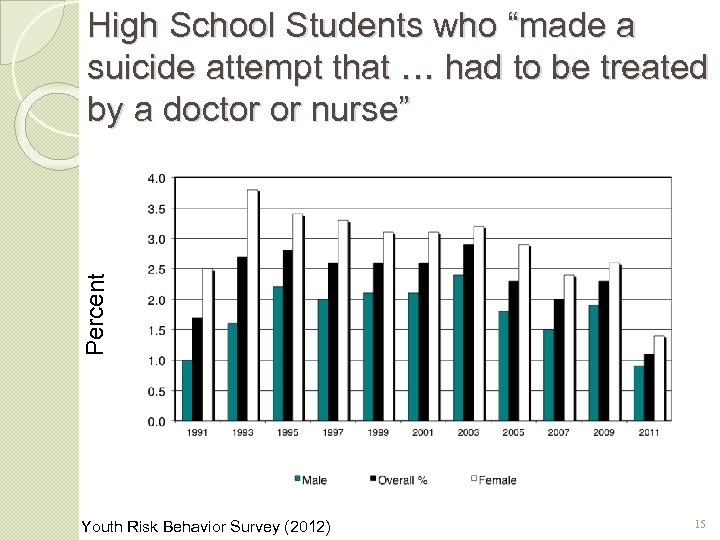

Percent High School Students who “made a suicide attempt that … had to be treated by a doctor or nurse” Youth Risk Behavior Survey (2012) 15

Percent High School Students who “made a suicide attempt that … had to be treated by a doctor or nurse” Youth Risk Behavior Survey (2012) 15

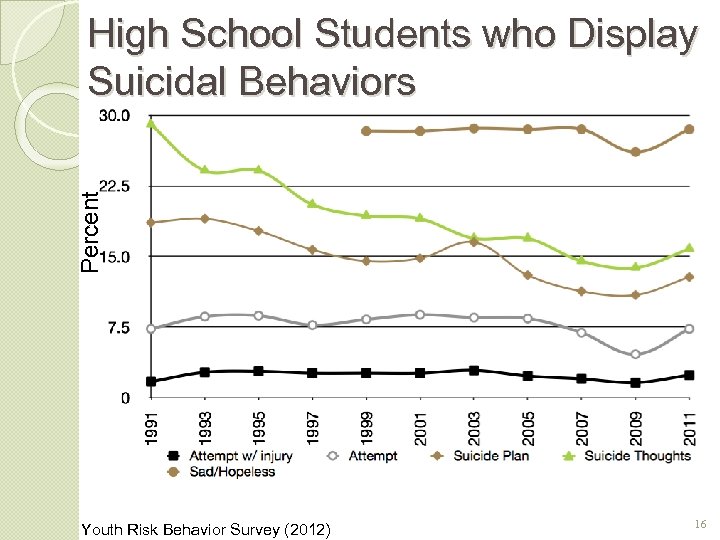

Percent High School Students who Display Suicidal Behaviors Youth Risk Behavior Survey (2012) 16

Percent High School Students who Display Suicidal Behaviors Youth Risk Behavior Survey (2012) 16

Presentation Outline Introduction ◦ Suicide Statistics Primary Prevention of Suicide ◦ Preventing Suicidal Ideation and Behavior Secondary Prevention of Suicide ◦ General Staff Procedures ◦ Risk Assessment and Referral Protocol Suicide Postvention 17

Presentation Outline Introduction ◦ Suicide Statistics Primary Prevention of Suicide ◦ Preventing Suicidal Ideation and Behavior Secondary Prevention of Suicide ◦ General Staff Procedures ◦ Risk Assessment and Referral Protocol Suicide Postvention 17

What is the School Psychologist’s role in preventing suicide in schools? • School provides ideal opportunities for quality suicide prevention messages. • We are leaders in the school in developing a comprehensive crisis management system KING, K. A. , STRUNK, C. M. , & SORTER, M. T. (2011). Preliminary Effectiveness of Surviving the Teens® Suicide Prevention and Depression Awareness Program on Adolescents' Suicidality and Self-Efficacy in Performing Help-Seeking Behaviors. Journal Of School Health, 81(9) 18

What is the School Psychologist’s role in preventing suicide in schools? • School provides ideal opportunities for quality suicide prevention messages. • We are leaders in the school in developing a comprehensive crisis management system KING, K. A. , STRUNK, C. M. , & SORTER, M. T. (2011). Preliminary Effectiveness of Surviving the Teens® Suicide Prevention and Depression Awareness Program on Adolescents' Suicidality and Self-Efficacy in Performing Help-Seeking Behaviors. Journal Of School Health, 81(9) 18

Primary Prevention: Policy It is the policy of the Governing Board that all staff members learn how to recognize students at risk, to identify warning signs of suicide, to take preventive precautions, and to report suicide threats to the appropriate parental and professional authorities. Administration shall ensure that all staff members have been issued a copy of the District's suicide prevention policy and procedures. All staff members are responsible for knowing and acting upon them. 19

Primary Prevention: Policy It is the policy of the Governing Board that all staff members learn how to recognize students at risk, to identify warning signs of suicide, to take preventive precautions, and to report suicide threats to the appropriate parental and professional authorities. Administration shall ensure that all staff members have been issued a copy of the District's suicide prevention policy and procedures. All staff members are responsible for knowing and acting upon them. 19

Primary Prevention: Gatekeeper Training natural community caregivers Advantages ◦ Reduced risk of imitation ◦ Expands community support systems Research is limited but promising ◦ Durable changes in attitudes, knowledge, intervention skills 20

Primary Prevention: Gatekeeper Training natural community caregivers Advantages ◦ Reduced risk of imitation ◦ Expands community support systems Research is limited but promising ◦ Durable changes in attitudes, knowledge, intervention skills 20

Primary Prevention: Gatekeeper Training A Specific Training Program: Applied Suicide Intervention Skills Training ◦ Author: Ramsay, Tanney, Tierney, & Lang ◦ Publisher: Living. Works Education, Inc ◦ 1 -403 -209 -0242 ◦ http: //www. livingworks. net/ Since 1985, ASIST has been delivered to over one million caregivers in more than 10 countries. Today 5, 000 registered trainers deliver ASIST around the world. ASIST is a recognized exemplary program (CDC, 1992). The program has been evaluated by more than 15 independent evaluations. Training for Trainers is a five-day course that prepares local resource persons to be trainers of the ASIST workshop. Around the world, there is a network of 1000 active, registered trainers. 21

Primary Prevention: Gatekeeper Training A Specific Training Program: Applied Suicide Intervention Skills Training ◦ Author: Ramsay, Tanney, Tierney, & Lang ◦ Publisher: Living. Works Education, Inc ◦ 1 -403 -209 -0242 ◦ http: //www. livingworks. net/ Since 1985, ASIST has been delivered to over one million caregivers in more than 10 countries. Today 5, 000 registered trainers deliver ASIST around the world. ASIST is a recognized exemplary program (CDC, 1992). The program has been evaluated by more than 15 independent evaluations. Training for Trainers is a five-day course that prepares local resource persons to be trainers of the ASIST workshop. Around the world, there is a network of 1000 active, registered trainers. 21

Primary Prevention: Curriculum SOS: Depression Screening and Suicide Prevention ◦ “The main teaching tool of the SOS program is a video that teaches students how to identify symptoms of depression and suicidality in themselves or their friends and encourages helpseeking. The program's primary objectives are to educate teens that depression is a treatable illness and to equip them to respond to a potential suicide in a friend or family member using the SOS technique. SOS is an action-oriented approach instructing students how to ACT (Acknowledge, Care and Tell) in the face of this mental health emergency. ” ◦ Evidenced based! 22

Primary Prevention: Curriculum SOS: Depression Screening and Suicide Prevention ◦ “The main teaching tool of the SOS program is a video that teaches students how to identify symptoms of depression and suicidality in themselves or their friends and encourages helpseeking. The program's primary objectives are to educate teens that depression is a treatable illness and to equip them to respond to a potential suicide in a friend or family member using the SOS technique. SOS is an action-oriented approach instructing students how to ACT (Acknowledge, Care and Tell) in the face of this mental health emergency. ” ◦ Evidenced based! 22

Primary Prevention: Screening School-wide Screening ◦ Very few false negatives ◦ Many false positives Requires second-stage evaluation Limitations ◦ Risk waxes and wanes ◦ Principals’ view of acceptability ◦ Requires effective referral procedures Possible Tools ◦ Suicidal Ideation Questionnaire (William Reynolds, Psychological Assessment Resources) ◦ Columbia Teen Screen (Columbia University) ◦ Beck Depression Inventory ◦ SOS Depression Screening and Suicide Prevention 23

Primary Prevention: Screening School-wide Screening ◦ Very few false negatives ◦ Many false positives Requires second-stage evaluation Limitations ◦ Risk waxes and wanes ◦ Principals’ view of acceptability ◦ Requires effective referral procedures Possible Tools ◦ Suicidal Ideation Questionnaire (William Reynolds, Psychological Assessment Resources) ◦ Columbia Teen Screen (Columbia University) ◦ Beck Depression Inventory ◦ SOS Depression Screening and Suicide Prevention 23

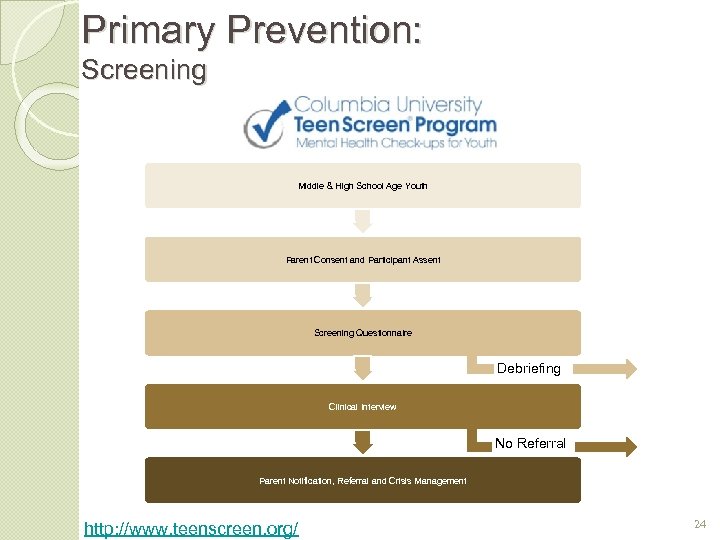

Primary Prevention: Screening Middle & High School Age Youth Parent Consent and Participant Assent Screening Questionnaire Debriefing Clinical Interview No Referral Parent Notification, Referral and Crisis Management http: //www. teenscreen. org/ 24

Primary Prevention: Screening Middle & High School Age Youth Parent Consent and Participant Assent Screening Questionnaire Debriefing Clinical Interview No Referral Parent Notification, Referral and Crisis Management http: //www. teenscreen. org/ 24

Primary Prevention: Suicide Prevention & Crisis Hotlines Rationale ◦ Suicidal ideation is associated with crisis ◦ Suicidal ideation is associated with ambivalence ◦ Special training is requires to respond to “cries for help” Likely benefit those who use them Limitations ◦ ◦ Limited research regarding effectiveness Few youth use hotlines Youth are less likely to be aware of hotlines Highest risk youth are least likely to use 25

Primary Prevention: Suicide Prevention & Crisis Hotlines Rationale ◦ Suicidal ideation is associated with crisis ◦ Suicidal ideation is associated with ambivalence ◦ Special training is requires to respond to “cries for help” Likely benefit those who use them Limitations ◦ ◦ Limited research regarding effectiveness Few youth use hotlines Youth are less likely to be aware of hotlines Highest risk youth are least likely to use 25

Primary Prevention: Suicide Prevention & Crisis Hotlines 26

Primary Prevention: Suicide Prevention & Crisis Hotlines 26

Primary Prevention: Risk Factor Reduction Restriction of Lethal Means Media Education Postvention Skills Training 27

Primary Prevention: Risk Factor Reduction Restriction of Lethal Means Media Education Postvention Skills Training 27

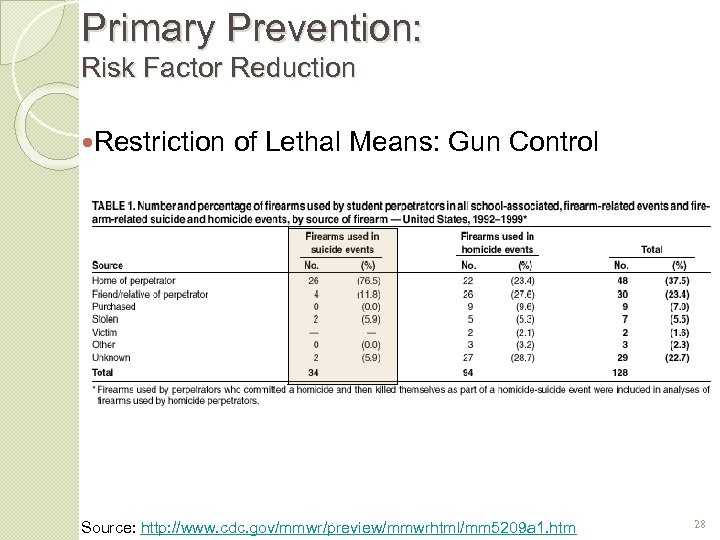

Primary Prevention: Risk Factor Reduction Restriction of Lethal Means: Gun Control Source: http: //www. cdc. gov/mmwr/preview/mmwrhtml/mm 5209 a 1. htm 28

Primary Prevention: Risk Factor Reduction Restriction of Lethal Means: Gun Control Source: http: //www. cdc. gov/mmwr/preview/mmwrhtml/mm 5209 a 1. htm 28

Protective factors in preventing suicide Family support and cohesion, including good communication. Peer support and close social networks. School and community connectedness. Cultural or religious beliefs that discourage suicide and promote healthy living. • Adaptive coping and problem-solving skills, including conflict -resolution. • General life satisfaction, good self-esteem, sense of purpose. • Easy access to effective medical and mental health resources. • • Source: http: //www. nasponline. org/resources/crisis_safety/suicideprevention. aspx 29

Protective factors in preventing suicide Family support and cohesion, including good communication. Peer support and close social networks. School and community connectedness. Cultural or religious beliefs that discourage suicide and promote healthy living. • Adaptive coping and problem-solving skills, including conflict -resolution. • General life satisfaction, good self-esteem, sense of purpose. • Easy access to effective medical and mental health resources. • • Source: http: //www. nasponline. org/resources/crisis_safety/suicideprevention. aspx 29

Presentation Outline Introduction ◦ Suicide Statistics Primary Prevention of Suicide Secondary Prevention of Suicide ◦ Suicide Intervention General Staff Procedures Risk Assessment and Referral Protocol Suicide Postvention 30

Presentation Outline Introduction ◦ Suicide Statistics Primary Prevention of Suicide Secondary Prevention of Suicide ◦ Suicide Intervention General Staff Procedures Risk Assessment and Referral Protocol Suicide Postvention 30

Duty to Warn When a student is a danger to self or others there is a duty to warn. ◦ Tarasoff v. Regents of the University of California 31

Duty to Warn When a student is a danger to self or others there is a duty to warn. ◦ Tarasoff v. Regents of the University of California 31

General Staff Procedures Responding to a Threat of Suicide. ◦ A student who has threatened suicide must be carefully observed at all times until a qualified staff member can conduct a risk assessment. ◦ The following procedures are to be followed whenever a student directly or indirectly threatens to commit suicide. 32

General Staff Procedures Responding to a Threat of Suicide. ◦ A student who has threatened suicide must be carefully observed at all times until a qualified staff member can conduct a risk assessment. ◦ The following procedures are to be followed whenever a student directly or indirectly threatens to commit suicide. 32

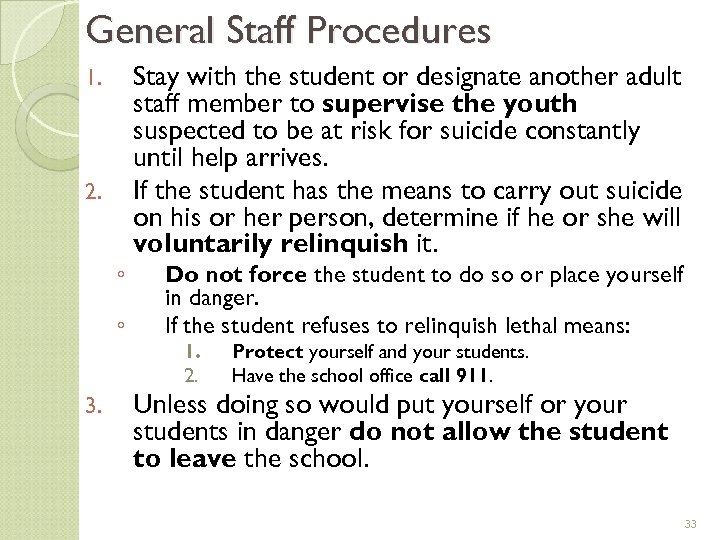

General Staff Procedures 1. 2. ◦ ◦ Stay with the student or designate another adult staff member to supervise the youth suspected to be at risk for suicide constantly until help arrives. If the student has the means to carry out suicide on his or her person, determine if he or she will voluntarily relinquish it. Do not force the student to do so or place yourself in danger. If the student refuses to relinquish lethal means: 1. 2. 3. Protect yourself and your students. Have the school office call 911. Unless doing so would put yourself or your students in danger do not allow the student to leave the school. 33

General Staff Procedures 1. 2. ◦ ◦ Stay with the student or designate another adult staff member to supervise the youth suspected to be at risk for suicide constantly until help arrives. If the student has the means to carry out suicide on his or her person, determine if he or she will voluntarily relinquish it. Do not force the student to do so or place yourself in danger. If the student refuses to relinquish lethal means: 1. 2. 3. Protect yourself and your students. Have the school office call 911. Unless doing so would put yourself or your students in danger do not allow the student to leave the school. 33

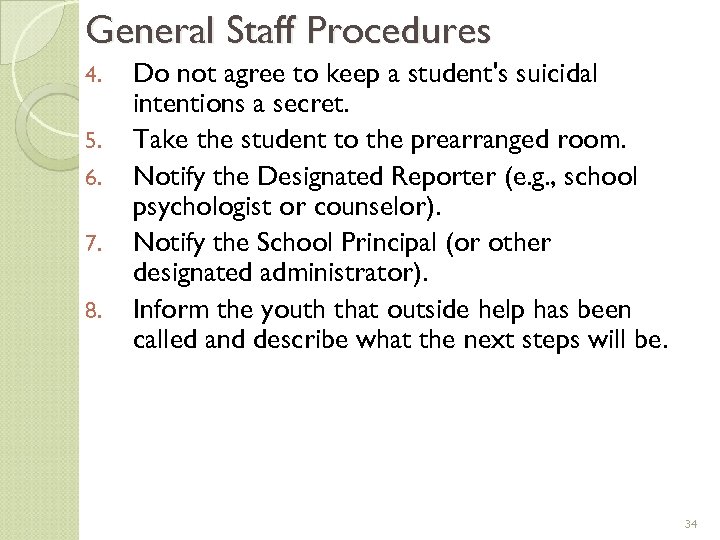

General Staff Procedures 4. 5. 6. 7. 8. Do not agree to keep a student's suicidal intentions a secret. Take the student to the prearranged room. Notify the Designated Reporter (e. g. , school psychologist or counselor). Notify the School Principal (or other designated administrator). Inform the youth that outside help has been called and describe what the next steps will be. 34

General Staff Procedures 4. 5. 6. 7. 8. Do not agree to keep a student's suicidal intentions a secret. Take the student to the prearranged room. Notify the Designated Reporter (e. g. , school psychologist or counselor). Notify the School Principal (or other designated administrator). Inform the youth that outside help has been called and describe what the next steps will be. 34

General Staff Procedures Requires that school staff members have… ◦ Knowledge of the risk factors the increase the odds of suicide. Variables that should direct our attention. ◦ Been trained to identify direct and indirect threats (or warning signs) that indicate the presence of suicide. Variables that should direct our action. 35

General Staff Procedures Requires that school staff members have… ◦ Knowledge of the risk factors the increase the odds of suicide. Variables that should direct our attention. ◦ Been trained to identify direct and indirect threats (or warning signs) that indicate the presence of suicide. Variables that should direct our action. 35

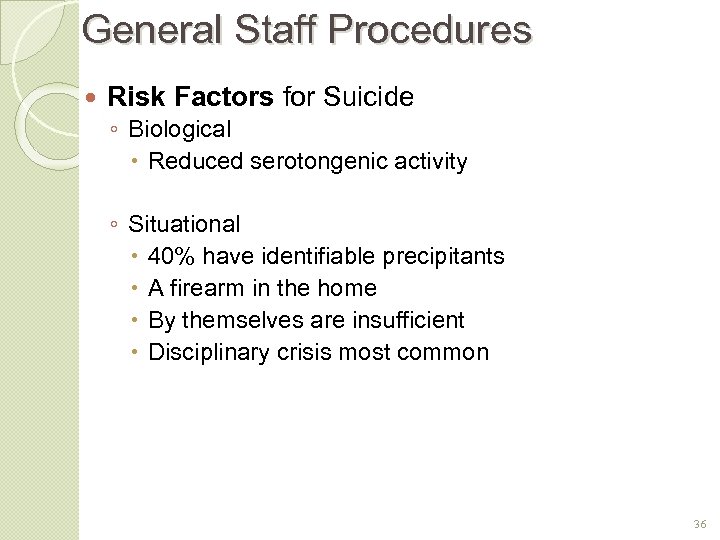

General Staff Procedures Risk Factors for Suicide ◦ Biological Reduced serotongenic activity ◦ Situational 40% have identifiable precipitants A firearm in the home By themselves are insufficient Disciplinary crisis most common 36

General Staff Procedures Risk Factors for Suicide ◦ Biological Reduced serotongenic activity ◦ Situational 40% have identifiable precipitants A firearm in the home By themselves are insufficient Disciplinary crisis most common 36

General Staff Procedures Risk Factors for Suicide ◦ Psychopathology Associated with 90% of suicides Prior suicidal behavior the best predictor Substance abuse increases vulnerability and can also act as a trigger ◦ Familial History Stressor Functioning 37

General Staff Procedures Risk Factors for Suicide ◦ Psychopathology Associated with 90% of suicides Prior suicidal behavior the best predictor Substance abuse increases vulnerability and can also act as a trigger ◦ Familial History Stressor Functioning 37

General Staff Procedures Risk Factors for Suicide Adolescence and late life Bisexual or homosexual gender identity Criminal behavior Cultural sanctions for suicide Delusions Disposition of personal property Divorced, separated, or single marital status Early loss or separation from parents Family history of suicide Hallucinations Homicide Hopelessness Hypochondriasis 38

General Staff Procedures Risk Factors for Suicide Adolescence and late life Bisexual or homosexual gender identity Criminal behavior Cultural sanctions for suicide Delusions Disposition of personal property Divorced, separated, or single marital status Early loss or separation from parents Family history of suicide Hallucinations Homicide Hopelessness Hypochondriasis 38

General Staff Procedures Warning Signs for Suicide ◦ Verbal Most individuals give verbal clues that they have suicidal thoughts. Clues include direct ("I have a plan to kill myself”) and indirect suicide threats (“I wish I could fall asleep and never wake up”). ◦ Behavioral 39

General Staff Procedures Warning Signs for Suicide ◦ Verbal Most individuals give verbal clues that they have suicidal thoughts. Clues include direct ("I have a plan to kill myself”) and indirect suicide threats (“I wish I could fall asleep and never wake up”). ◦ Behavioral 39

General Staff Procedures Verbal Warnings Signs of Suicide 1. “Everybody would be better off if I just weren’t around. ” 2. “I’m not going to bug you much longer. ” 3. “I hate my life. I hate everyone and everything. ” 4. “I’m the cause of all of my family’s/friend’s troubles. ” 5. “I wish I would just go to sleep and never wake up. ” 6. “I’ve tried everything but nothing seems to help. ” 7. “Nobody can help me. ” 8. “I want to kill myself but I don’t have the guts. ” 9. “I’m no good to anyone. ” 10. “If my (father, mother, teacher) doesn’t leave me alone I’m going to kill myself. ” 11. “Don’t buy me anything. I won’t be needing any (clothes, books). ” 40

General Staff Procedures Verbal Warnings Signs of Suicide 1. “Everybody would be better off if I just weren’t around. ” 2. “I’m not going to bug you much longer. ” 3. “I hate my life. I hate everyone and everything. ” 4. “I’m the cause of all of my family’s/friend’s troubles. ” 5. “I wish I would just go to sleep and never wake up. ” 6. “I’ve tried everything but nothing seems to help. ” 7. “Nobody can help me. ” 8. “I want to kill myself but I don’t have the guts. ” 9. “I’m no good to anyone. ” 10. “If my (father, mother, teacher) doesn’t leave me alone I’m going to kill myself. ” 11. “Don’t buy me anything. I won’t be needing any (clothes, books). ” 40

General Staff Procedures Behavioral Warning Signs of Suicide 1. Writing of suicidal notes 2. Making final arrangements 3. Giving away prized possessions 4. Talking about death 5. Reading, writing, and/or art about death 6. Hopelessness or helplessness 7. Social Withdrawal and isolation 8. Lost involvement in interests & activities 9. Increased risk-taking 10. Heavy use of alcohol or drugs 41

General Staff Procedures Behavioral Warning Signs of Suicide 1. Writing of suicidal notes 2. Making final arrangements 3. Giving away prized possessions 4. Talking about death 5. Reading, writing, and/or art about death 6. Hopelessness or helplessness 7. Social Withdrawal and isolation 8. Lost involvement in interests & activities 9. Increased risk-taking 10. Heavy use of alcohol or drugs 41

General Staff Procedures Behavioral Warning Signs of Suicide (cont. ) 11. Abrupt changes in appearance 12. Sudden weight or appetite change 13. Sudden changes in personality or attitude 14. Inability to concentrate/think rationally 15. Sudden unexpected happiness 16. Sleeplessness or sleepiness 17. Increased irritability or crying easily 18. Low self esteem 42

General Staff Procedures Behavioral Warning Signs of Suicide (cont. ) 11. Abrupt changes in appearance 12. Sudden weight or appetite change 13. Sudden changes in personality or attitude 14. Inability to concentrate/think rationally 15. Sudden unexpected happiness 16. Sleeplessness or sleepiness 17. Increased irritability or crying easily 18. Low self esteem 42

General Staff Procedures Behavioral Warning Signs of Suicide (cont. ) 19. Dwindling academic performance 20. Abrupt changes in attendance 21. Failure to complete assignments 22. Lack of interest and withdrawal 23. Changed relationships 24. Despairing attitude 43

General Staff Procedures Behavioral Warning Signs of Suicide (cont. ) 19. Dwindling academic performance 20. Abrupt changes in attendance 21. Failure to complete assignments 22. Lack of interest and withdrawal 23. Changed relationships 24. Despairing attitude 43

Presentation Outline Introduction ◦ Suicide Statistics Primary Prevention of Suicide Secondary Prevention of Suicide ◦ Preventing Suicidal Behavior General Staff Procedures Risk Assessment and Referral Protocol Suicide Postvention 44

Presentation Outline Introduction ◦ Suicide Statistics Primary Prevention of Suicide Secondary Prevention of Suicide ◦ Preventing Suicidal Behavior General Staff Procedures Risk Assessment and Referral Protocol Suicide Postvention 44

Risk Assessment and Referral Protocol Whenever a student judged to have some risk of engaging in self-directed violence or suicide, a school-based mental health professional should conduct a risk assessment and make the appropriate referrals. Identify Assess Consult Refer 45

Risk Assessment and Referral Protocol Whenever a student judged to have some risk of engaging in self-directed violence or suicide, a school-based mental health professional should conduct a risk assessment and make the appropriate referrals. Identify Assess Consult Refer 45

Risk Assessment and Referral Protocol 1. Identify suicidal thoughts. 2. Conduct a risk assessment and make appropriate referrals. a) Consult with fellow school staff members regarding the risk assessment and referral options. b) Consult with County Mental Health regarding the risk assessment and referral options. c) As indicated, consult with local law enforcement about referral options. 46

Risk Assessment and Referral Protocol 1. Identify suicidal thoughts. 2. Conduct a risk assessment and make appropriate referrals. a) Consult with fellow school staff members regarding the risk assessment and referral options. b) Consult with County Mental Health regarding the risk assessment and referral options. c) As indicated, consult with local law enforcement about referral options. 46

Risk Assessment and Referral Protocol 3. Use risk assessment information and consultation guidance to develop an action plan. Action plan options are as follows: A. Extreme Risk If the student has the means of his or her threatened suicide at hand, and refuses to relinquish such then follow the Extreme Risk Procedures. B. Crisis Intervention Referral If the student's risk of suicide is judged to be moderate to high, but means of violence are not at hand, then follow the Crisis Intervention Referral Procedures. C. Mental Health Referral 3. If the student's risk of suicide is judged to be low and means of violence are not at hand, then follow the Mental Health Referral Procedures. 47

Risk Assessment and Referral Protocol 3. Use risk assessment information and consultation guidance to develop an action plan. Action plan options are as follows: A. Extreme Risk If the student has the means of his or her threatened suicide at hand, and refuses to relinquish such then follow the Extreme Risk Procedures. B. Crisis Intervention Referral If the student's risk of suicide is judged to be moderate to high, but means of violence are not at hand, then follow the Crisis Intervention Referral Procedures. C. Mental Health Referral 3. If the student's risk of suicide is judged to be low and means of violence are not at hand, then follow the Mental Health Referral Procedures. 47

Risk Assessment and Referral Protocol A. Extreme Risk i. Have school administration call the police. ii. If it is judged safe to do so, attempt to calm the student by talking and reassuring him or her until the police arrive. iii. If it is judged safe to do so, continue to request that the student relinquish the means his or her threatened suicide and try to prevent the student from harming self or others. iv. Call the parents and inform them of the actions taken. 48

Risk Assessment and Referral Protocol A. Extreme Risk i. Have school administration call the police. ii. If it is judged safe to do so, attempt to calm the student by talking and reassuring him or her until the police arrive. iii. If it is judged safe to do so, continue to request that the student relinquish the means his or her threatened suicide and try to prevent the student from harming self or others. iv. Call the parents and inform them of the actions taken. 48

Risk Assessment and Referral Protocol B. Crisis Intervention Referral i. Determine if the student's distress is the result of parent or caretaker abuse, neglect, or exploitation. ii. Meet with the student's parents or caregivers. iii. Determine what to do if the parents or caregivers are unable or unwilling to assist with the crisis. iv. Make appropriate referrals. 49

Risk Assessment and Referral Protocol B. Crisis Intervention Referral i. Determine if the student's distress is the result of parent or caretaker abuse, neglect, or exploitation. ii. Meet with the student's parents or caregivers. iii. Determine what to do if the parents or caregivers are unable or unwilling to assist with the crisis. iv. Make appropriate referrals. 49

Risk Assessment and Referral Protocol C. Mental Health Referral i. Determine if the student's distress is the result of parent or caretaker abuse, neglect, or exploitation. ii. Meet with the student's parents or caregivers. iii. Make appropriate referrals. 4. Protect the privacy of the student and family. 5. Follow-up with the referral resources (e. g. , hospital or clinic). 50

Risk Assessment and Referral Protocol C. Mental Health Referral i. Determine if the student's distress is the result of parent or caretaker abuse, neglect, or exploitation. ii. Meet with the student's parents or caregivers. iii. Make appropriate referrals. 4. Protect the privacy of the student and family. 5. Follow-up with the referral resources (e. g. , hospital or clinic). 50

Suicide Risk Assessment Asking the “S” Question ◦ The presence of suicide warning signs, especially when combined with suicide risk factors generates the need to conduct a suicide risk assessment. ◦ Risk assessment begins with asking if the student is having thoughts of suicide. 51

Suicide Risk Assessment Asking the “S” Question ◦ The presence of suicide warning signs, especially when combined with suicide risk factors generates the need to conduct a suicide risk assessment. ◦ Risk assessment begins with asking if the student is having thoughts of suicide. 51

Its Your Turn…. Imagine you are working with a student that may be suicidal. How you would ask the question. 52

Its Your Turn…. Imagine you are working with a student that may be suicidal. How you would ask the question. 52

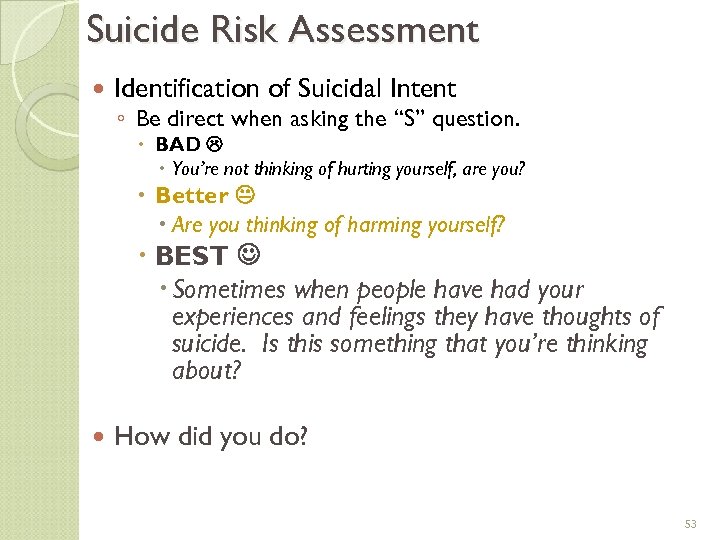

Suicide Risk Assessment Identification of Suicidal Intent ◦ Be direct when asking the “S” question. BAD You’re not thinking of hurting yourself, are you? Better Are you thinking of harming yourself? BEST Sometimes when people have had your experiences and feelings they have thoughts of suicide. Is this something that you’re thinking about? How did you do? 53

Suicide Risk Assessment Identification of Suicidal Intent ◦ Be direct when asking the “S” question. BAD You’re not thinking of hurting yourself, are you? Better Are you thinking of harming yourself? BEST Sometimes when people have had your experiences and feelings they have thoughts of suicide. Is this something that you’re thinking about? How did you do? 53

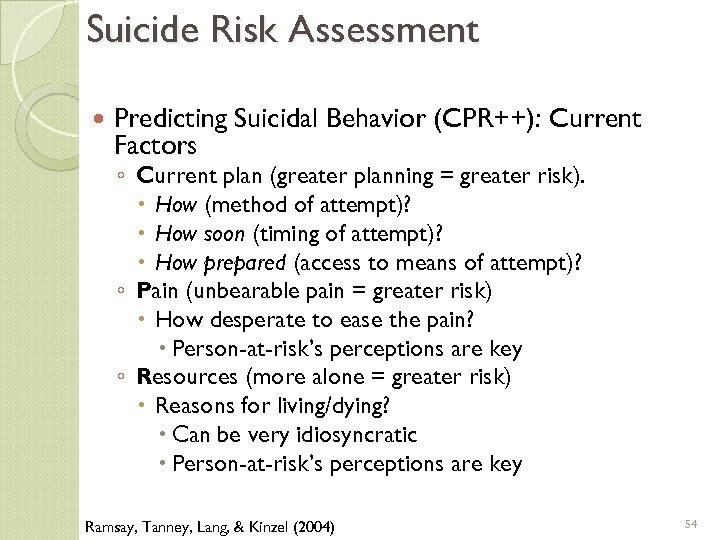

Suicide Risk Assessment Predicting Suicidal Behavior (CPR++): Current Factors ◦ Current plan (greater planning = greater risk). How (method of attempt)? How soon (timing of attempt)? How prepared (access to means of attempt)? ◦ Pain (unbearable pain = greater risk) How desperate to ease the pain? Person-at-risk’s perceptions are key ◦ Resources (more alone = greater risk) Reasons for living/dying? Can be very idiosyncratic Person-at-risk’s perceptions are key Ramsay, Tanney, Lang, & Kinzel (2004) 54

Suicide Risk Assessment Predicting Suicidal Behavior (CPR++): Current Factors ◦ Current plan (greater planning = greater risk). How (method of attempt)? How soon (timing of attempt)? How prepared (access to means of attempt)? ◦ Pain (unbearable pain = greater risk) How desperate to ease the pain? Person-at-risk’s perceptions are key ◦ Resources (more alone = greater risk) Reasons for living/dying? Can be very idiosyncratic Person-at-risk’s perceptions are key Ramsay, Tanney, Lang, & Kinzel (2004) 54

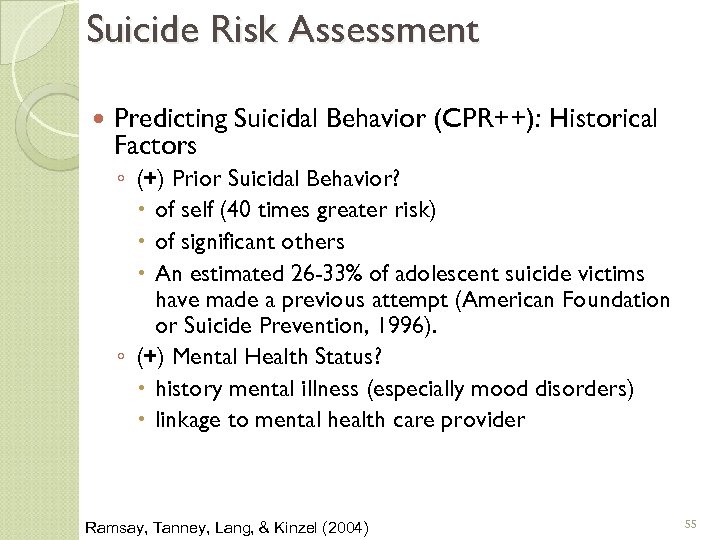

Suicide Risk Assessment Predicting Suicidal Behavior (CPR++): Historical Factors ◦ (+) Prior Suicidal Behavior? of self (40 times greater risk) of significant others An estimated 26 -33% of adolescent suicide victims have made a previous attempt (American Foundation or Suicide Prevention, 1996). ◦ (+) Mental Health Status? history mental illness (especially mood disorders) linkage to mental health care provider Ramsay, Tanney, Lang, & Kinzel (2004) 55

Suicide Risk Assessment Predicting Suicidal Behavior (CPR++): Historical Factors ◦ (+) Prior Suicidal Behavior? of self (40 times greater risk) of significant others An estimated 26 -33% of adolescent suicide victims have made a previous attempt (American Foundation or Suicide Prevention, 1996). ◦ (+) Mental Health Status? history mental illness (especially mood disorders) linkage to mental health care provider Ramsay, Tanney, Lang, & Kinzel (2004) 55

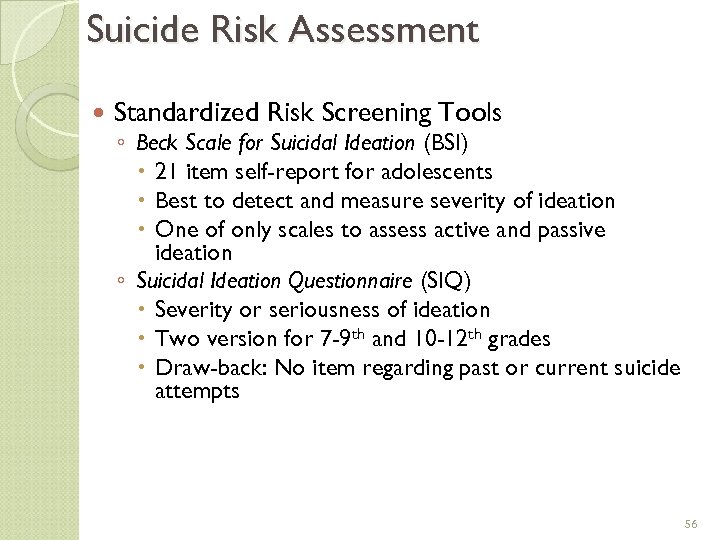

Suicide Risk Assessment Standardized Risk Screening Tools ◦ Beck Scale for Suicidal Ideation (BSI) 21 item self-report for adolescents Best to detect and measure severity of ideation One of only scales to assess active and passive ideation ◦ Suicidal Ideation Questionnaire (SIQ) Severity or seriousness of ideation Two version for 7 -9 th and 10 -12 th grades Draw-back: No item regarding past or current suicide attempts 56

Suicide Risk Assessment Standardized Risk Screening Tools ◦ Beck Scale for Suicidal Ideation (BSI) 21 item self-report for adolescents Best to detect and measure severity of ideation One of only scales to assess active and passive ideation ◦ Suicidal Ideation Questionnaire (SIQ) Severity or seriousness of ideation Two version for 7 -9 th and 10 -12 th grades Draw-back: No item regarding past or current suicide attempts 56

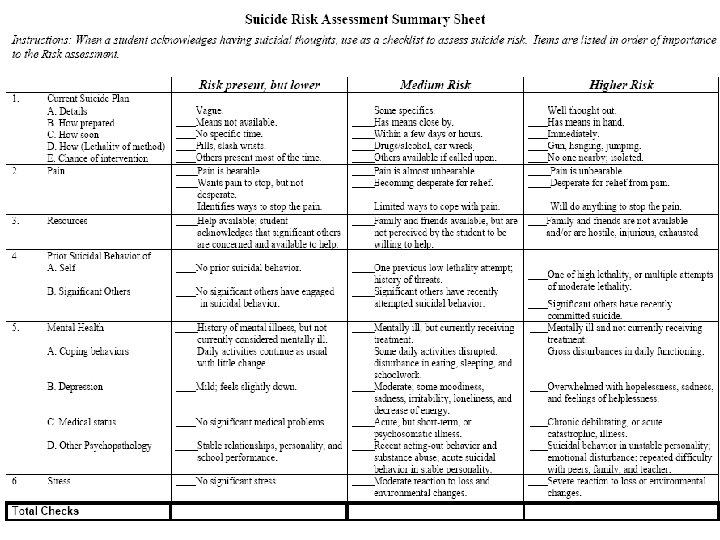

Suicide Risk Assessment Summary 57

Suicide Risk Assessment Summary 57

Responding to At-Risk Youth Teach appropriate behavior and social problem-solving skills in the classroom or in a small group setting. 2. Additional problems or risk factors are addressed through determining student and family needs. ◦ Referrals made to appropriate support systems. 3. Protective factors for student are analyzed and provisions made to continue or to add to these factors, which provide support for the at-risk student. ◦ For example, provide an adult mentor who meets periodically with the student. 1. 58

Responding to At-Risk Youth Teach appropriate behavior and social problem-solving skills in the classroom or in a small group setting. 2. Additional problems or risk factors are addressed through determining student and family needs. ◦ Referrals made to appropriate support systems. 3. Protective factors for student are analyzed and provisions made to continue or to add to these factors, which provide support for the at-risk student. ◦ For example, provide an adult mentor who meets periodically with the student. 1. 58

Responding to High Risk Youth 4. Determine if there any imminent warning signs. ◦ If there are, then refer student for an immediate suicide and/or homicide risk assessment. 5. 6. If imminent warning signs are not present, then give the student a high priority for a Student Success Team Meeting. ◦ Assign a Student Success Team member (e. g. , principal, school psychologist, or teacher) to provide informal consultation until a formal meeting may be scheduled. At the SST meeting, develop recommendations for responding to high-risk youth and consider the need for a referral for Special Education services. Consider a referral to school site mental health and community-based mental health services. 59

Responding to High Risk Youth 4. Determine if there any imminent warning signs. ◦ If there are, then refer student for an immediate suicide and/or homicide risk assessment. 5. 6. If imminent warning signs are not present, then give the student a high priority for a Student Success Team Meeting. ◦ Assign a Student Success Team member (e. g. , principal, school psychologist, or teacher) to provide informal consultation until a formal meeting may be scheduled. At the SST meeting, develop recommendations for responding to high-risk youth and consider the need for a referral for Special Education services. Consider a referral to school site mental health and community-based mental health services. 59

Responding to High Risk Youth 9. Consider the need to revise student’s behavior contract and/or to conduct a more in-depth functional assessment. 10. Obtain parental permission to exchange information with the appropriate community agencies to determine if student is eligible for additional services. ◦ 11. If available, call a meeting with other agency personnel to focus on provisions for wrap-around intervention and support for the student and family. Develop an action plan for immediate interventions that includes provisions for increased supervision. 60

Responding to High Risk Youth 9. Consider the need to revise student’s behavior contract and/or to conduct a more in-depth functional assessment. 10. Obtain parental permission to exchange information with the appropriate community agencies to determine if student is eligible for additional services. ◦ 11. If available, call a meeting with other agency personnel to focus on provisions for wrap-around intervention and support for the student and family. Develop an action plan for immediate interventions that includes provisions for increased supervision. 60

Presentation Outline Introduction ◦ Suicide Statistics Primary Prevention of Suicide Secondary Prevention of Suicide ◦ General Staff Procedures ◦ Risk Assessment and Referral Protocol Suicide Postvention 61

Presentation Outline Introduction ◦ Suicide Statistics Primary Prevention of Suicide Secondary Prevention of Suicide ◦ General Staff Procedures ◦ Risk Assessment and Referral Protocol Suicide Postvention 61

School Suicide Postvention “… the largest public health problem is neither the prevention of suicide nor the management of suicide attempts, but the alleviation of the effects of stress on the survivors whose lives are forever altered. ” E. S. Shneidman Forward to Survivors of Suicide Edited by A. C. Cain Published by Thomas, 1972 62

School Suicide Postvention “… the largest public health problem is neither the prevention of suicide nor the management of suicide attempts, but the alleviation of the effects of stress on the survivors whose lives are forever altered. ” E. S. Shneidman Forward to Survivors of Suicide Edited by A. C. Cain Published by Thomas, 1972 62

School Suicide Postvention Key Terms and Statistics ◦ Suicide postvention … is the provision of crisis intervention, support and assistance for those affected by a completed suicide. Affected individuals includes both “survivors” and other persons who were “exposed” to the death. Andriessen & Krysinska (2012) 63

School Suicide Postvention Key Terms and Statistics ◦ Suicide postvention … is the provision of crisis intervention, support and assistance for those affected by a completed suicide. Affected individuals includes both “survivors” and other persons who were “exposed” to the death. Andriessen & Krysinska (2012) 63

School Suicide Postvention Key Terms and Statistics ◦ Survivors of suicide “the family members and friends who experience the suicide of a loved one” (Mc. Intosh, 1993, p. 146). “a person who has lost a significant other (or a loved one) by suicide, and whose life is changed because of the loss” (Andriessen, 2009, p. 43). “… someone who experiences a high level of self-perceived psychological, physical, and/or social distress for a considerable length of time after exposure to the suicide of another person” (Jordan & Mc. Intosh, 2011, p. 7). 64

School Suicide Postvention Key Terms and Statistics ◦ Survivors of suicide “the family members and friends who experience the suicide of a loved one” (Mc. Intosh, 1993, p. 146). “a person who has lost a significant other (or a loved one) by suicide, and whose life is changed because of the loss” (Andriessen, 2009, p. 43). “… someone who experiences a high level of self-perceived psychological, physical, and/or social distress for a considerable length of time after exposure to the suicide of another person” (Jordan & Mc. Intosh, 2011, p. 7). 64

School Suicide Postvention Key Terms and Statistics ◦ How many survivors of suicide are there? Estimates vary greatly Shneidman (1969) = 6 per suicide Wrobleski (2002) = 10 per suicide Berman (2011) = 80 -45 per suicide X N of Survivors per suicide 36, 909 Completed Suicides (U. S. 2009) = Suicide Survivors 65

School Suicide Postvention Key Terms and Statistics ◦ How many survivors of suicide are there? Estimates vary greatly Shneidman (1969) = 6 per suicide Wrobleski (2002) = 10 per suicide Berman (2011) = 80 -45 per suicide X N of Survivors per suicide 36, 909 Completed Suicides (U. S. 2009) = Suicide Survivors 65

School Suicide Postvention Key Terms and Statistics ◦ There is a distinction between “suicide survivorship” and “exposure to suicide. ” Survivor applies to bereaved persons who had a personal/close relationship with the deceased. Exposure applies to persons who did not know the deceased personally, but who know about the death through reports of others or media reports or who has personally witnessed the death of a stranger. Andriessen & Krysinska (2012) 66

School Suicide Postvention Key Terms and Statistics ◦ There is a distinction between “suicide survivorship” and “exposure to suicide. ” Survivor applies to bereaved persons who had a personal/close relationship with the deceased. Exposure applies to persons who did not know the deceased personally, but who know about the death through reports of others or media reports or who has personally witnessed the death of a stranger. Andriessen & Krysinska (2012) 66

School Suicide Postvention Key Terms and Statistics ◦ Both survivors and educators need support. Survivors need… support groups. support from outside of the family. to be educated about the complicated dynamics of grieving. to be contacted in person (instead of by letter or phone). Grad et al. (2004) 67

School Suicide Postvention Key Terms and Statistics ◦ Both survivors and educators need support. Survivors need… support groups. support from outside of the family. to be educated about the complicated dynamics of grieving. to be contacted in person (instead of by letter or phone). Grad et al. (2004) 67

Special Issues in Postvention Factors that make the postvention response a special and unique form of crisis intervention. 1. 2. 3. 4. 5. Suicide contagion A special form of bereavement Social stigma Developmental differences Cultural differences American Foundation for Suicide Prevention (2001); Cain (1972); De Groot et al. (2006); Jordan & Mc. Intosh (2011); Jordan (2001); Mishara (1999); O’Carroll & Potter (1994); Ramsay et al. (1999); Roberts et al. (1998); Sonneck et al. (1994) 68

Special Issues in Postvention Factors that make the postvention response a special and unique form of crisis intervention. 1. 2. 3. 4. 5. Suicide contagion A special form of bereavement Social stigma Developmental differences Cultural differences American Foundation for Suicide Prevention (2001); Cain (1972); De Groot et al. (2006); Jordan & Mc. Intosh (2011); Jordan (2001); Mishara (1999); O’Carroll & Potter (1994); Ramsay et al. (1999); Roberts et al. (1998); Sonneck et al. (1994) 68

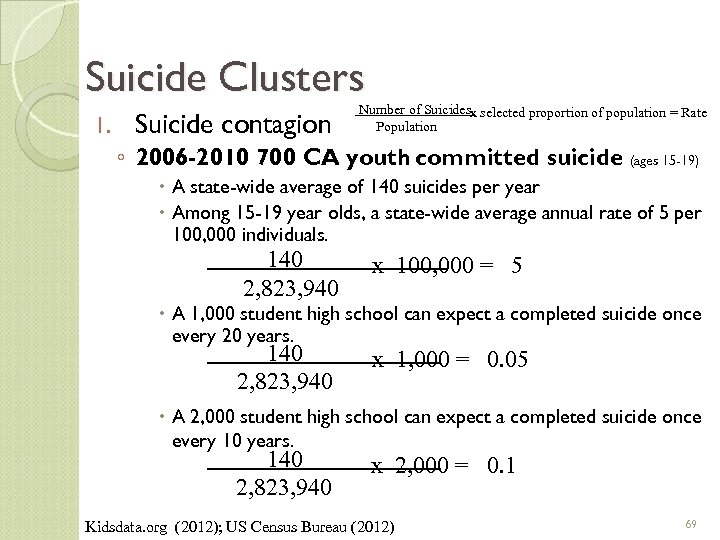

Suicide Clusters 1. Suicide contagion Number of Suicidesx selected proportion of population = Rate Population ◦ 2006 -2010 700 CA youth committed suicide (ages 15 -19) A state-wide average of 140 suicides per year Among 15 -19 year olds, a state-wide average annual rate of 5 per 100, 000 individuals. 140 2, 823, 940 x 100, 000 = 5 A 1, 000 student high school can expect a completed suicide once every 20 years. 140 2, 823, 940 x 1, 000 = 0. 05 A 2, 000 student high school can expect a completed suicide once every 10 years. 140 2, 823, 940 x 2, 000 = 0. 1 Kidsdata. org (2012); US Census Bureau (2012) 69

Suicide Clusters 1. Suicide contagion Number of Suicidesx selected proportion of population = Rate Population ◦ 2006 -2010 700 CA youth committed suicide (ages 15 -19) A state-wide average of 140 suicides per year Among 15 -19 year olds, a state-wide average annual rate of 5 per 100, 000 individuals. 140 2, 823, 940 x 100, 000 = 5 A 1, 000 student high school can expect a completed suicide once every 20 years. 140 2, 823, 940 x 1, 000 = 0. 05 A 2, 000 student high school can expect a completed suicide once every 10 years. 140 2, 823, 940 x 2, 000 = 0. 1 Kidsdata. org (2012); US Census Bureau (2012) 69

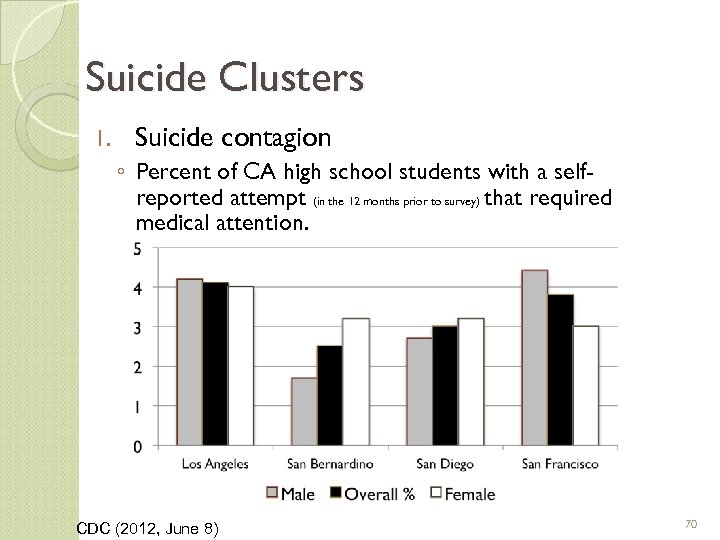

Suicide Clusters 1. Suicide contagion ◦ Percent of CA high school students with a selfreported attempt (in the 12 months prior to survey) that required medical attention. CDC (2012, June 8) 70

Suicide Clusters 1. Suicide contagion ◦ Percent of CA high school students with a selfreported attempt (in the 12 months prior to survey) that required medical attention. CDC (2012, June 8) 70

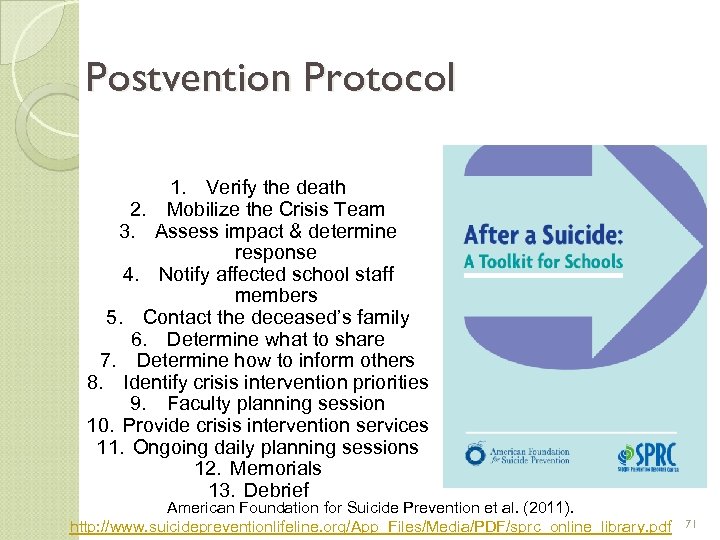

Postvention Protocol 1. Verify the death 2. Mobilize the Crisis Team 3. Assess impact & determine response 4. Notify affected school staff members 5. Contact the deceased’s family 6. Determine what to share 7. Determine how to inform others 8. Identify crisis intervention priorities 9. Faculty planning session 10. Provide crisis intervention services 11. Ongoing daily planning sessions 12. Memorials 13. Debrief American Foundation for Suicide Prevention et al. (2011). http: //www. suicidepreventionlifeline. org/App_Files/Media/PDF/sprc_online_library. pdf 71

Postvention Protocol 1. Verify the death 2. Mobilize the Crisis Team 3. Assess impact & determine response 4. Notify affected school staff members 5. Contact the deceased’s family 6. Determine what to share 7. Determine how to inform others 8. Identify crisis intervention priorities 9. Faculty planning session 10. Provide crisis intervention services 11. Ongoing daily planning sessions 12. Memorials 13. Debrief American Foundation for Suicide Prevention et al. (2011). http: //www. suicidepreventionlifeline. org/App_Files/Media/PDF/sprc_online_library. pdf 71

Postvention Protocol 1. Verify that a death has occurred ◦ Confirm the cause of death Confirmed suicide Unconfirmed cause of death Brock (2002) 72

Postvention Protocol 1. Verify that a death has occurred ◦ Confirm the cause of death Confirmed suicide Unconfirmed cause of death Brock (2002) 72

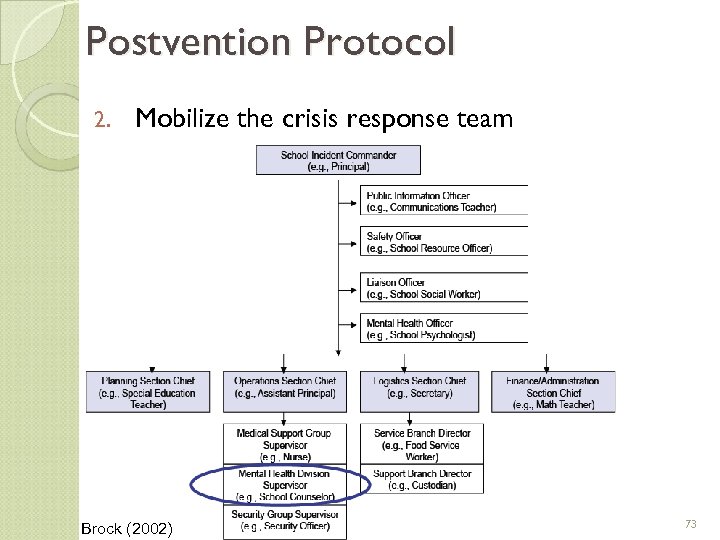

Postvention Protocol 2. Mobilize the crisis response team Brock (2002) 73

Postvention Protocol 2. Mobilize the crisis response team Brock (2002) 73

Postvention Protocol 3. Assess the suicide’s impact on the school and estimate the level of response required. ◦ The importance of accurate estimates. Make sure a postvention is truly needed before initiating this intervention. ◦ Temporal proximity to other traumatic events (especially suicides). ◦ Timing of the suicide. ◦ Physical and/or emotional proximity to the suicide. Brock (2002) 74

Postvention Protocol 3. Assess the suicide’s impact on the school and estimate the level of response required. ◦ The importance of accurate estimates. Make sure a postvention is truly needed before initiating this intervention. ◦ Temporal proximity to other traumatic events (especially suicides). ◦ Timing of the suicide. ◦ Physical and/or emotional proximity to the suicide. Brock (2002) 74

Postvention Protocol 4. Notify other involved school staff members. ◦ Deceased student’s teachers (current an former) ◦ Any other staff members who had a relationship with the deceased ◦ Teachers and staff who work with suicide survivors. Brock (2002) 75

Postvention Protocol 4. Notify other involved school staff members. ◦ Deceased student’s teachers (current an former) ◦ Any other staff members who had a relationship with the deceased ◦ Teachers and staff who work with suicide survivors. Brock (2002) 75

Postvention Protocol 5. Contact the family of the suicide victim. ◦ Purposes include. . . Express sympathy and offer support. Identify the victim’s friends/siblings who may need assistance. Discuss the school’s response to the death. Identify details about the death could be shared with outsiders. Brock (2002); American Foundation for Suicide Prevention et al. (2011) 76

Postvention Protocol 5. Contact the family of the suicide victim. ◦ Purposes include. . . Express sympathy and offer support. Identify the victim’s friends/siblings who may need assistance. Discuss the school’s response to the death. Identify details about the death could be shared with outsiders. Brock (2002); American Foundation for Suicide Prevention et al. (2011) 76

Postvention Protocol 6. Determine what information to share about the death ◦ Several different communications may be necessary When the death has been ruled a suicide When the cause of death is unconfirmed When the family has requested that the cause of death not be disclosed Templates provided in After a Suicide: A Toolkit for Schools” Brock (2002); American Foundation for Suicide Prevention et al. (2011) 77

Postvention Protocol 6. Determine what information to share about the death ◦ Several different communications may be necessary When the death has been ruled a suicide When the cause of death is unconfirmed When the family has requested that the cause of death not be disclosed Templates provided in After a Suicide: A Toolkit for Schools” Brock (2002); American Foundation for Suicide Prevention et al. (2011) 77

Postvention Protocol 6. Determine what information to share about the death ◦ Avoid detailed descriptions of the suicide including specific method and location. ◦ Avoid over simplifying the causes of suicide and presenting them as inexplicable or unavoidable. ◦ Avoid using the words “committed suicide” or “failed suicide. ” ◦ Always include a referral phone number and information about local crisis intervention services ◦ Emphasize recent treatment advances for depression and other mental illness. Brock (2002); American Foundation for Suicide Prevention et al. (2011) 78

Postvention Protocol 6. Determine what information to share about the death ◦ Avoid detailed descriptions of the suicide including specific method and location. ◦ Avoid over simplifying the causes of suicide and presenting them as inexplicable or unavoidable. ◦ Avoid using the words “committed suicide” or “failed suicide. ” ◦ Always include a referral phone number and information about local crisis intervention services ◦ Emphasize recent treatment advances for depression and other mental illness. Brock (2002); American Foundation for Suicide Prevention et al. (2011) 78

Postvention Protocol 7. Determine how to share information about the death. ◦ Reporting the death to students. . . Avoid tributes by friends, school wide assemblies, sharing information over PA systems that may romanticize the death Positive attention given to someone who has died (or attempted to die) by suicide can lead vulnerable individuals who desire such attention to take their own lives. Provide information in small groups (e. g. , classrooms). Brock, 2002 79

Postvention Protocol 7. Determine how to share information about the death. ◦ Reporting the death to students. . . Avoid tributes by friends, school wide assemblies, sharing information over PA systems that may romanticize the death Positive attention given to someone who has died (or attempted to die) by suicide can lead vulnerable individuals who desire such attention to take their own lives. Provide information in small groups (e. g. , classrooms). Brock, 2002 79

Postvention Protocol 7. Determine how to share information about the death. ◦ Reporting the death to the media. . . It is essential that the media not romanticize the death. The media should be encouraged to acknowledge the pathological aspects of suicide. Photos of the suicide victim should not be used. “Suicide" should not be placed in the caption. Include information about the community resources. Sample media statement provided in “After a Suicide: A Toolkit for Schools” Brock, 2002; American Foundation for Suicide Prevention et al. (2011) 80

Postvention Protocol 7. Determine how to share information about the death. ◦ Reporting the death to the media. . . It is essential that the media not romanticize the death. The media should be encouraged to acknowledge the pathological aspects of suicide. Photos of the suicide victim should not be used. “Suicide" should not be placed in the caption. Include information about the community resources. Sample media statement provided in “After a Suicide: A Toolkit for Schools” Brock, 2002; American Foundation for Suicide Prevention et al. (2011) 80

Postvention Protocol 7. Determine how to share information about the death. ◦ Reporting the death to the media: Guidelines from the World Health Organization 1. Suicide is never the result of a single incident 2. Avoid providing details of the method or the location a suicide victim uses that can be copied 3. Provide the appropriate vital statistics (i. e. , as indicated provide information about the mental health challenges typically associated with suicide). 4. Provide information about resources that can help to address suicidal ideation. Brock (2002); World Health Organization (2000) 81

Postvention Protocol 7. Determine how to share information about the death. ◦ Reporting the death to the media: Guidelines from the World Health Organization 1. Suicide is never the result of a single incident 2. Avoid providing details of the method or the location a suicide victim uses that can be copied 3. Provide the appropriate vital statistics (i. e. , as indicated provide information about the mental health challenges typically associated with suicide). 4. Provide information about resources that can help to address suicidal ideation. Brock (2002); World Health Organization (2000) 81

Postvention Protocol 8. Identify students significantly affected by the suicide and initiate referral procedures. ◦ Risk Factors for Imitative Behavior Facilitated the suicide. Failed to recognize the suicidal intent. Believe they may have caused the suicide. Had a relationship with the suicide victim. Identify with the suicide victim. Have a history of prior suicidal behavior. Have a history of psychopathology. Shows symptoms of helplessness and/or hopelessness. Have suffered significant life stressors or losses. Lack internal and external resources Brock (2002); Brock & Sandoval (1996) 82

Postvention Protocol 8. Identify students significantly affected by the suicide and initiate referral procedures. ◦ Risk Factors for Imitative Behavior Facilitated the suicide. Failed to recognize the suicidal intent. Believe they may have caused the suicide. Had a relationship with the suicide victim. Identify with the suicide victim. Have a history of prior suicidal behavior. Have a history of psychopathology. Shows symptoms of helplessness and/or hopelessness. Have suffered significant life stressors or losses. Lack internal and external resources Brock (2002); Brock & Sandoval (1996) 82

Postvention Protocol 9. Conduct a faculty planning session. ◦ Share information about the death. ◦ Allow staff to express their reactions and grief. . ◦ Provide a scripted death notification statement for students. ◦ Prepare for student reactions and questions ◦ Explain plans for the day. 9. Remind all staff of the role they play in identifying changes in behavior and discuss plan for handling students who are having difficulty. 10. Brief staff about identifying and referring at-risk students as well as the need to keep records of those efforts. 11. Apprise staff of any outside crisis responders or others who will be assisting. 12. Remind staff of student dismissal protocol for funeral. 13. Identify which Crisis Response Team member has been designated as the media spokesperson and instruct staff to refer all media inquiries to him or her. Brock (2002); American Foundation for Suicide Prevention et al. (2011) 83

Postvention Protocol 9. Conduct a faculty planning session. ◦ Share information about the death. ◦ Allow staff to express their reactions and grief. . ◦ Provide a scripted death notification statement for students. ◦ Prepare for student reactions and questions ◦ Explain plans for the day. 9. Remind all staff of the role they play in identifying changes in behavior and discuss plan for handling students who are having difficulty. 10. Brief staff about identifying and referring at-risk students as well as the need to keep records of those efforts. 11. Apprise staff of any outside crisis responders or others who will be assisting. 12. Remind staff of student dismissal protocol for funeral. 13. Identify which Crisis Response Team member has been designated as the media spokesperson and instruct staff to refer all media inquiries to him or her. Brock (2002); American Foundation for Suicide Prevention et al. (2011) 83

Postvention Protocol 10. a) b) c) Initiate crisis intervention services d) e) f) g) Initial intervention options… Individual psychological first aid. Group psychological first aid. Classroom activities and/or presentations. Parent meetings. Staff meetings. Walk through the suicide victim’s class schedule. Meet separately with individuals who were proximal to the suicide. Identify severely traumatized and make appropriate referrals. Facilitate dis-identification with the suicide victim… Do not romanticize or glorify the victim's behavior or circumstances. Point out how students are different from the victim. Parental contact. Psychotherapy Referrals. Brock (2002) 84

Postvention Protocol 10. a) b) c) Initiate crisis intervention services d) e) f) g) Initial intervention options… Individual psychological first aid. Group psychological first aid. Classroom activities and/or presentations. Parent meetings. Staff meetings. Walk through the suicide victim’s class schedule. Meet separately with individuals who were proximal to the suicide. Identify severely traumatized and make appropriate referrals. Facilitate dis-identification with the suicide victim… Do not romanticize or glorify the victim's behavior or circumstances. Point out how students are different from the victim. Parental contact. Psychotherapy Referrals. Brock (2002) 84

Postvention Protocol 11. Consider memorials ◦ “A delicate balance must be struck that creates opportunities for students to grieve but that does not increase suicide risk for other school students by glorifying, romanticizing or sensationalizing suicide. ” Center for Suicide Prevention (2004) 85

Postvention Protocol 11. Consider memorials ◦ “A delicate balance must be struck that creates opportunities for students to grieve but that does not increase suicide risk for other school students by glorifying, romanticizing or sensationalizing suicide. ” Center for Suicide Prevention (2004) 85

Postvention Protocol 11. Consider memorials Do NOT. . . ◦ send all students from school to funerals, or stop classes for a funeral. ◦ have memorial or funeral services at school. ◦ establish permanent memorials such as plaques or dedicating yearbooks to the memory of suicide victims. ◦ dedicate songs or sporting events to the suicide victims. ◦ fly the flag at half staff. ◦ have assemblies focusing on the suicide victim, or have a moment of silence in all-school assemblies. Brock & Sandoval (2006) 86

Postvention Protocol 11. Consider memorials Do NOT. . . ◦ send all students from school to funerals, or stop classes for a funeral. ◦ have memorial or funeral services at school. ◦ establish permanent memorials such as plaques or dedicating yearbooks to the memory of suicide victims. ◦ dedicate songs or sporting events to the suicide victims. ◦ fly the flag at half staff. ◦ have assemblies focusing on the suicide victim, or have a moment of silence in all-school assemblies. Brock & Sandoval (2006) 86

Postvention Protocol 11. Consider memorials DO. . . ◦ something to prevent other suicides (e. g. , encourage crisis hotline volunteerism). ◦ develop living memorials, such as student assistance programs, that will help others cope with feelings and problems. ◦ allow students, with parental permission, to attend the funeral. ◦ Donate/Collect funds to help suicide prevention programs and/or to help families with funeral expenses ◦ encourage affected students, with parental permission, to attend the funeral. ◦ mention to families and ministers the need to distance the person who committed suicide from survivors and to avoid glorifying the suicidal act. Brock & Sandoval (2006) 87

Postvention Protocol 11. Consider memorials DO. . . ◦ something to prevent other suicides (e. g. , encourage crisis hotline volunteerism). ◦ develop living memorials, such as student assistance programs, that will help others cope with feelings and problems. ◦ allow students, with parental permission, to attend the funeral. ◦ Donate/Collect funds to help suicide prevention programs and/or to help families with funeral expenses ◦ encourage affected students, with parental permission, to attend the funeral. ◦ mention to families and ministers the need to distance the person who committed suicide from survivors and to avoid glorifying the suicidal act. Brock & Sandoval (2006) 87

Postvention Protocol 12. Debrief the postvention response. ◦ Goals for debriefing will include… Review and evaluation of all crisis intervention activities. Making of plans for follow-up actions. Providing an opportunity to help intervenors cope. Brock (2002) 88

Postvention Protocol 12. Debrief the postvention response. ◦ Goals for debriefing will include… Review and evaluation of all crisis intervention activities. Making of plans for follow-up actions. Providing an opportunity to help intervenors cope. Brock (2002) 88

Concluding Observation “… the person who commits suicide puts his psychological skeleton in the survivor’s emotional closet; he sentences the survivor to deal with many negative feelings and more, to become obsessed with thoughts regarding the survivor’s own actual or possible role in having precipitated the suicidal act or having failed to stop it. It can be a heavy load” (p. x). Shneidman (1972) 89

Concluding Observation “… the person who commits suicide puts his psychological skeleton in the survivor’s emotional closet; he sentences the survivor to deal with many negative feelings and more, to become obsessed with thoughts regarding the survivor’s own actual or possible role in having precipitated the suicidal act or having failed to stop it. It can be a heavy load” (p. x). Shneidman (1972) 89

Selected References American Foundation for Suicide Prevention and Suicide Prevention Resource Center. (2011). After a suicide: A toolkit for schools. Newton, MA: Education Development Center. Retrieved from http: //www. suicidepreventionlifeline. org/App_Files/Media/PDF/sprc_online_library. pdf American Foundation for Suicide Prevention, American Association of Suicideology, & Annenberg Public Policy Center. (2001). Reporting on suicide: Recommendations for the media. Retrieved from http: //www. suicidology. org/c/document_library/get_file? folder. Id=231&name=DLFE-71. pdf Andriessen, K. (2009). Can postvention be prevention? Crisis, 30, 43 -47. Andriessen, K. , & Krysinska, K. (2012). Essential questions on suicide bereavement and postvention. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 9, 24 -32. doi: 10. 3390/ijerph 9010024 Berman, A. L. Estimating the population of survivors of suicide: Seeking an evidence base. Suicide & Life Threatening Behavior, 41, 110 -116. Brock, S. E. (2002). School suicide postvention. In S. E. Brock, P. J. Lazarus, & S. R. Jimerson (Eds. ), Best practices in school crisis prevention and intervention (pp. 553 -575). Bethesda, MD: National Association of School Psychologists. Brock, S. E. (2003, May). Suicide postvention. Paper presented at the DODEA Safe Schools Seminar. Retrieved from http: //www. dodea. edu/dodsafeschools/members/seminar/Suicide. Prevention/generalreading. html #2 Brock, S. E. , Sandoval, J. , & Hart, S. R. (2006). Suicidal ideation and behaviors. In G Bear & K Minke (Eds. ), Children’s needs III: Understanding and addressing the developmental needs of children (pp. 187 -197). Bethesda, MD: National Association of School Psychologists 90

Selected References American Foundation for Suicide Prevention and Suicide Prevention Resource Center. (2011). After a suicide: A toolkit for schools. Newton, MA: Education Development Center. Retrieved from http: //www. suicidepreventionlifeline. org/App_Files/Media/PDF/sprc_online_library. pdf American Foundation for Suicide Prevention, American Association of Suicideology, & Annenberg Public Policy Center. (2001). Reporting on suicide: Recommendations for the media. Retrieved from http: //www. suicidology. org/c/document_library/get_file? folder. Id=231&name=DLFE-71. pdf Andriessen, K. (2009). Can postvention be prevention? Crisis, 30, 43 -47. Andriessen, K. , & Krysinska, K. (2012). Essential questions on suicide bereavement and postvention. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 9, 24 -32. doi: 10. 3390/ijerph 9010024 Berman, A. L. Estimating the population of survivors of suicide: Seeking an evidence base. Suicide & Life Threatening Behavior, 41, 110 -116. Brock, S. E. (2002). School suicide postvention. In S. E. Brock, P. J. Lazarus, & S. R. Jimerson (Eds. ), Best practices in school crisis prevention and intervention (pp. 553 -575). Bethesda, MD: National Association of School Psychologists. Brock, S. E. (2003, May). Suicide postvention. Paper presented at the DODEA Safe Schools Seminar. Retrieved from http: //www. dodea. edu/dodsafeschools/members/seminar/Suicide. Prevention/generalreading. html #2 Brock, S. E. , Sandoval, J. , & Hart, S. R. (2006). Suicidal ideation and behaviors. In G Bear & K Minke (Eds. ), Children’s needs III: Understanding and addressing the developmental needs of children (pp. 187 -197). Bethesda, MD: National Association of School Psychologists 90

Selected References Cain, A. C. (Ed. ). (1972). Survivors of Suicide. Springfield, IL, Thomas: Springfield, IL. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2012, March 9). Web-based injury statistics query and reporting system (WISQARS). Leading causes of death reports. Atlanta, GA: National Center for Injury Prevention and Control. Retrieved from http: //www. cdc. gov/injury/wisqars/index. html Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2012, June 8). Youth risk behavior surveillance – United States, 2011, MMWR, 61(4), 1 -162. Retrieved from http: //www. cdc. gov/mmwr/pdf/ss/ss 6104. pdf Center for Suicide Prevention. (2004, May). School memorials after suicide: Helpful or harmful? Retrieved from www. suicideinfo. ca Davis, J. M. , & Brock, S. E. (2002). Suicide. In J. Sandoval (Ed. ), Handbook of crisis counseling, intervention and prevention in the schools (2 nd ed. , pp. 273 -299). Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates. de Groot, M. H. , de Keijeser, D. , & Neeleman, J. (2006). Grief shortly after suicide and nautral death: A comparative study among spouses and first-degree relatives. Suicide and Life-Threatening Behavior, 36, 418 -431. Grad, O. T. , Clark, S. , Dyregrov, K. , & Andriessen, K. (2004). What helps and what hinders the process of surviving the suicide of somebody close? Crisis, 25, 134 -139. Jordan, J. R. (2001). Is suicide bereavement different: A reassessment of the literature. Suicide & Life. Threatening Behavior, 31 91 -102. Jordan, J. R. & Mc. Intosh, J. L. (2011). Suicide bereavement: Why study survivors of suicide loss? In J. R. Jordan, J. L. Mc. Intosh (Eds. ), Grief after Suicide (pp. 3 -17). New York, NY: Routledge. 91

Selected References Cain, A. C. (Ed. ). (1972). Survivors of Suicide. Springfield, IL, Thomas: Springfield, IL. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2012, March 9). Web-based injury statistics query and reporting system (WISQARS). Leading causes of death reports. Atlanta, GA: National Center for Injury Prevention and Control. Retrieved from http: //www. cdc. gov/injury/wisqars/index. html Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2012, June 8). Youth risk behavior surveillance – United States, 2011, MMWR, 61(4), 1 -162. Retrieved from http: //www. cdc. gov/mmwr/pdf/ss/ss 6104. pdf Center for Suicide Prevention. (2004, May). School memorials after suicide: Helpful or harmful? Retrieved from www. suicideinfo. ca Davis, J. M. , & Brock, S. E. (2002). Suicide. In J. Sandoval (Ed. ), Handbook of crisis counseling, intervention and prevention in the schools (2 nd ed. , pp. 273 -299). Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates. de Groot, M. H. , de Keijeser, D. , & Neeleman, J. (2006). Grief shortly after suicide and nautral death: A comparative study among spouses and first-degree relatives. Suicide and Life-Threatening Behavior, 36, 418 -431. Grad, O. T. , Clark, S. , Dyregrov, K. , & Andriessen, K. (2004). What helps and what hinders the process of surviving the suicide of somebody close? Crisis, 25, 134 -139. Jordan, J. R. (2001). Is suicide bereavement different: A reassessment of the literature. Suicide & Life. Threatening Behavior, 31 91 -102. Jordan, J. R. & Mc. Intosh, J. L. (2011). Suicide bereavement: Why study survivors of suicide loss? In J. R. Jordan, J. L. Mc. Intosh (Eds. ), Grief after Suicide (pp. 3 -17). New York, NY: Routledge. 91

Selected References Jordan, J. R. (2001). Is suicide bereavement different: A reassessment of the literature. Suicide & Life. Threatening Behavior, 31 91 -102. Jordan, J. R. & Mc. Intosh, J. L. (2011). Suicide bereavement: Why study survivors of suicide loss? In J. R. Jordan, J. L. Mc. Intosh (Eds. ), Grief after Suicide (pp. 3 -17). New York, NY: Routledge. Mc. Intosh, J. (1993). Control group studies of suicide survivors: A review and critique. Suicide Life & Threatening Behavior, 23, 146 -161. Mishara, B. L. (1999). Concepts of death and suicide in children ages 6 -12 and their implications for suicide prevention. Suicide & Life-Threatening Behavior, 29, 105 -118. O’Carroll, P. W. , & Potter, L. B. (1994, April 22). Suicide contagion and the reporting of suicide: Recommendations form a national workshop. MMWR, 43(RR-6), 11 -19. Retrieved from http: //www. cdc. gov/mmwr/preview/mmwrhtml/00031539. htm Ramsay, R. F. , Tanney, B. L. , Tierney, R. J. , & Lang, W. A. (1996). Suicide intervention workshop (6 th ed. ). Calgary, AB: Living. Works Education. Roberts, R. L. , Lepkowski, W. J. , & Davidson, K. K. (1998). Dealing with the aftermath of a student suicide: A T. E. A. M. approach. NASSP Bulletin, 82, 53 -59. Scocco, P. , Frasson, A. , Costacurta, A. , & Pavan, L. (2006). SPRPoxi: A research-intervention project for suicide survivors. Crisis, 27, 39 -41. Shneidman, E. (1969). Prologue: Fifty-eight years. In E. S. Scneidman (Ed. ) On the nature of suicide (pp. 1 -30). San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass. Shneidman, E. (1972). Forward. In A. C. Cain (Ed. ), Survivors of Suicide. Springfield, IL: Thomas. Sonneck, G. , Etzersdorfer. , & Nagel-Kuess, S. (1994). Imitative suicide on the Viennese subway. Social Science & Medicine, 38(3), 453 -457. doi: 10. 1016/0277 -9536(94)90447 -2 Wrobleski, A. (2002). Suicide survivors: A guide for those left behind. Minneapolis, MN: SAVE. 92

Selected References Jordan, J. R. (2001). Is suicide bereavement different: A reassessment of the literature. Suicide & Life. Threatening Behavior, 31 91 -102. Jordan, J. R. & Mc. Intosh, J. L. (2011). Suicide bereavement: Why study survivors of suicide loss? In J. R. Jordan, J. L. Mc. Intosh (Eds. ), Grief after Suicide (pp. 3 -17). New York, NY: Routledge. Mc. Intosh, J. (1993). Control group studies of suicide survivors: A review and critique. Suicide Life & Threatening Behavior, 23, 146 -161. Mishara, B. L. (1999). Concepts of death and suicide in children ages 6 -12 and their implications for suicide prevention. Suicide & Life-Threatening Behavior, 29, 105 -118. O’Carroll, P. W. , & Potter, L. B. (1994, April 22). Suicide contagion and the reporting of suicide: Recommendations form a national workshop. MMWR, 43(RR-6), 11 -19. Retrieved from http: //www. cdc. gov/mmwr/preview/mmwrhtml/00031539. htm Ramsay, R. F. , Tanney, B. L. , Tierney, R. J. , & Lang, W. A. (1996). Suicide intervention workshop (6 th ed. ). Calgary, AB: Living. Works Education. Roberts, R. L. , Lepkowski, W. J. , & Davidson, K. K. (1998). Dealing with the aftermath of a student suicide: A T. E. A. M. approach. NASSP Bulletin, 82, 53 -59. Scocco, P. , Frasson, A. , Costacurta, A. , & Pavan, L. (2006). SPRPoxi: A research-intervention project for suicide survivors. Crisis, 27, 39 -41. Shneidman, E. (1969). Prologue: Fifty-eight years. In E. S. Scneidman (Ed. ) On the nature of suicide (pp. 1 -30). San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass. Shneidman, E. (1972). Forward. In A. C. Cain (Ed. ), Survivors of Suicide. Springfield, IL: Thomas. Sonneck, G. , Etzersdorfer. , & Nagel-Kuess, S. (1994). Imitative suicide on the Viennese subway. Social Science & Medicine, 38(3), 453 -457. doi: 10. 1016/0277 -9536(94)90447 -2 Wrobleski, A. (2002). Suicide survivors: A guide for those left behind. Minneapolis, MN: SAVE. 92