ff0e5337a874db8ddbcbca0fc0dc750d.ppt

- Количество слайдов: 80

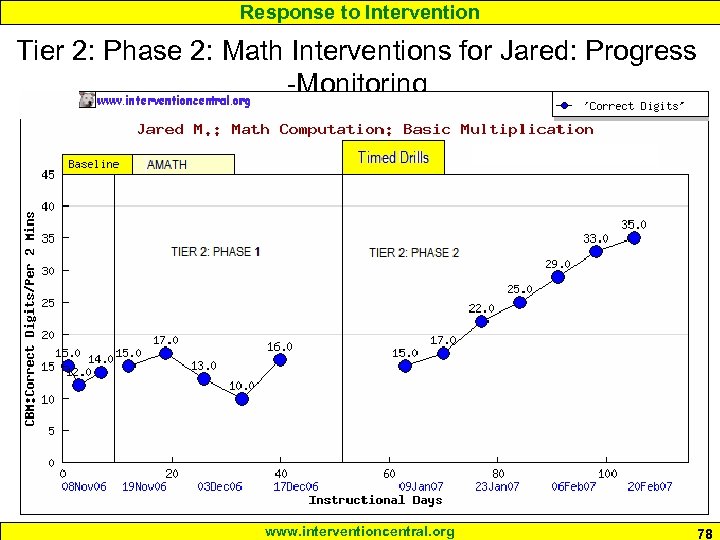

Response to Intervention Foundations of Math Skills & RTI Interventions Jim Wright www. interventioncentral. org

Response to Intervention Foundations of Math Skills & RTI Interventions Jim Wright www. interventioncentral. org

Response to Intervention “Mathematics is made of 50 percent formulas, 50 percent proofs, and 50 percent imagination. ” –Anonymous www. interventioncentral. org 2

Response to Intervention “Mathematics is made of 50 percent formulas, 50 percent proofs, and 50 percent imagination. ” –Anonymous www. interventioncentral. org 2

Response to Intervention Who is At Risk for Poor Math Performance? : A Proactive Stance “…we use the term mathematics difficulties rather than mathematics disabilities. Children who exhibit mathematics difficulties include those performing in the low average range (e. g. , at or below the 35 th percentile) as well as those performing well below average…Using higher percentile cutoffs increases the likelihood thatyoung children who go on to have serious math problems will be picked upin the screening. ” p. 295 Source: Gersten, R. , Jordan, N. C. , & Flojo, J. R. (2005). Early identification and interventions for students with mathematics difficulties. Journal of Learning Disabilities, 38, 293 -304. www. interventioncentral. org 3

Response to Intervention Who is At Risk for Poor Math Performance? : A Proactive Stance “…we use the term mathematics difficulties rather than mathematics disabilities. Children who exhibit mathematics difficulties include those performing in the low average range (e. g. , at or below the 35 th percentile) as well as those performing well below average…Using higher percentile cutoffs increases the likelihood thatyoung children who go on to have serious math problems will be picked upin the screening. ” p. 295 Source: Gersten, R. , Jordan, N. C. , & Flojo, J. R. (2005). Early identification and interventions for students with mathematics difficulties. Journal of Learning Disabilities, 38, 293 -304. www. interventioncentral. org 3

Response to Intervention Profile of Students with Math Difficulties (Kroesbergen & Van Luit, 2003) [Although the group of students with difficulties in learning math is very heterogeneous], in general, these students have memory deficits leading to difficulties in the acquisition and remembering of math knowledge. Moreover, they often show inadequate use of strategies for solving math tasks, caused by problems with the acquisition and the application of both cognitive and metacognitive strategies. Because of these problems, they also show deficits in generalization (2003). Mathematics interventions for children with special Source: Kroesbergen, E. , & Van Luit, J. E. H. and transfer of educational knowledge to Education, 24, unknown learned needs. Remedial and Specialnew and 97 -114. . www. interventioncentral. org 4

Response to Intervention Profile of Students with Math Difficulties (Kroesbergen & Van Luit, 2003) [Although the group of students with difficulties in learning math is very heterogeneous], in general, these students have memory deficits leading to difficulties in the acquisition and remembering of math knowledge. Moreover, they often show inadequate use of strategies for solving math tasks, caused by problems with the acquisition and the application of both cognitive and metacognitive strategies. Because of these problems, they also show deficits in generalization (2003). Mathematics interventions for children with special Source: Kroesbergen, E. , & Van Luit, J. E. H. and transfer of educational knowledge to Education, 24, unknown learned needs. Remedial and Specialnew and 97 -114. . www. interventioncentral. org 4

Response to Intervention The Elements of Mathematical Proficiency: What the Experts Say… www. interventioncentral. org

Response to Intervention The Elements of Mathematical Proficiency: What the Experts Say… www. interventioncentral. org

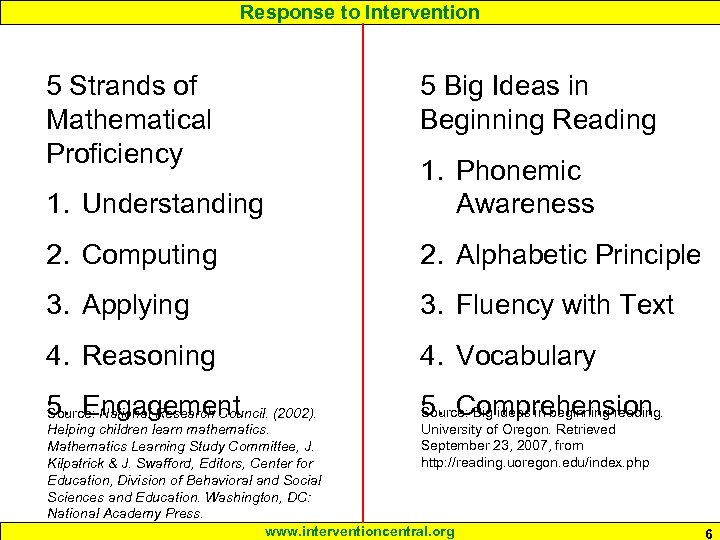

Response to Intervention 5 Strands of Mathematical Proficiency 5 Big Ideas in Beginning Reading 1. Understanding 1. Phonemic Awareness 2. Computing 2. Alphabetic Principle 3. Applying 3. Fluency with Text 4. Reasoning 4. Vocabulary 5. Engagement (2002). Source: National Research Council. 5. Comprehension Source: Big ideas in beginning reading. University of Oregon. Retrieved Helping children learn mathematics. September 23, 2007, from Mathematics Learning Study Committee, J. http: //reading. uoregon. edu/index. php Kilpatrick & J. Swafford, Editors, Center for Education, Division of Behavioral and Social Sciences and Education. Washington, DC: National Academy Press. www. interventioncentral. org 6

Response to Intervention 5 Strands of Mathematical Proficiency 5 Big Ideas in Beginning Reading 1. Understanding 1. Phonemic Awareness 2. Computing 2. Alphabetic Principle 3. Applying 3. Fluency with Text 4. Reasoning 4. Vocabulary 5. Engagement (2002). Source: National Research Council. 5. Comprehension Source: Big ideas in beginning reading. University of Oregon. Retrieved Helping children learn mathematics. September 23, 2007, from Mathematics Learning Study Committee, J. http: //reading. uoregon. edu/index. php Kilpatrick & J. Swafford, Editors, Center for Education, Division of Behavioral and Social Sciences and Education. Washington, DC: National Academy Press. www. interventioncentral. org 6

Response to Intervention Five Strands of Mathematical Proficiency “ 1. Understanding: Comprehending mathematical concepts, operations, and relations--knowing what mathematical symbols, diagrams, and procedures mean. Understanding refers to a student’s grasp of fundamental mathematical ideas. Students with understanding know more than isolated facts and procedures. They know why a mathematical idea is important and the contexts in which it is useful. Furthermore, they are aware of many connections between mathematical ideas. In fact, the degree of students’ understanding is related to the richness Source: National Research Council. (2002). Helping children learn mathematics. Mathematics Learning Study Committee, J. Kilpatrick & J. Swafford, Editors, Center for Education, Division of Behavioral and p. and extent of the Academy Press. connections they have made. ” Social Sciences and Education. Washington, DC: National www. interventioncentral. org 10 7

Response to Intervention Five Strands of Mathematical Proficiency “ 1. Understanding: Comprehending mathematical concepts, operations, and relations--knowing what mathematical symbols, diagrams, and procedures mean. Understanding refers to a student’s grasp of fundamental mathematical ideas. Students with understanding know more than isolated facts and procedures. They know why a mathematical idea is important and the contexts in which it is useful. Furthermore, they are aware of many connections between mathematical ideas. In fact, the degree of students’ understanding is related to the richness Source: National Research Council. (2002). Helping children learn mathematics. Mathematics Learning Study Committee, J. Kilpatrick & J. Swafford, Editors, Center for Education, Division of Behavioral and p. and extent of the Academy Press. connections they have made. ” Social Sciences and Education. Washington, DC: National www. interventioncentral. org 10 7

Response to Intervention Five Strands of Mathematical Proficiency “ 2. Computing: Carrying out mathematical procedures, such as adding, subtracting, multiplying, and dividing numbers flexibly, accurately, efficiently, and appropriately. Computing includes being fluent with procedures for adding, subtracting, multiplying, and dividing mentally or with paper and pencil, and knowing when and how to use these procedures appropriately. Although the word computing implies an arithmetic procedure, … it also refers to being fluent with procedures from other branches of mathematics, such as measurement (measuring lengths), algebra (solving equations), geometry (constructing similar figures), and statistics (graphing data). Being fluent Source: National Research Council. (2002). Helping children learn mathematics. Mathematics Learning Study means J. Swafford, Editors, Center for Education, Division of Behavioral and Committee, J. Kilpatrick &having the skill to perform the procedure Social Sciences and Education. Washington, DC: National Academy Press. flexibly. ” p. 11 efficiently, accurately, and www. interventioncentral. org 8

Response to Intervention Five Strands of Mathematical Proficiency “ 2. Computing: Carrying out mathematical procedures, such as adding, subtracting, multiplying, and dividing numbers flexibly, accurately, efficiently, and appropriately. Computing includes being fluent with procedures for adding, subtracting, multiplying, and dividing mentally or with paper and pencil, and knowing when and how to use these procedures appropriately. Although the word computing implies an arithmetic procedure, … it also refers to being fluent with procedures from other branches of mathematics, such as measurement (measuring lengths), algebra (solving equations), geometry (constructing similar figures), and statistics (graphing data). Being fluent Source: National Research Council. (2002). Helping children learn mathematics. Mathematics Learning Study means J. Swafford, Editors, Center for Education, Division of Behavioral and Committee, J. Kilpatrick &having the skill to perform the procedure Social Sciences and Education. Washington, DC: National Academy Press. flexibly. ” p. 11 efficiently, accurately, and www. interventioncentral. org 8

Response to Intervention Five Strands of Mathematical Proficiency “ 3. Applying: Being able to formulate problems mathematically and to devise strategies for solving them using concepts and procedures appropriately. Applying involves using one’s conceptual and procedural knowledge to solve problems. A concept or procedure is not useful unless students recognize when and where to use it—as well as when and whether it does not apply. … Students …need to be able to pose problems, devise solution strategies, and choose the most useful strategy for solving problems. . ” p. 13 Source: National Research Council. (2002). Helping children learn mathematics. Mathematics Learning Study Committee, J. Kilpatrick & J. Swafford, Editors, Center for Education, Division of Behavioral and Social Sciences and Education. Washington, DC: National Academy Press. www. interventioncentral. org 9

Response to Intervention Five Strands of Mathematical Proficiency “ 3. Applying: Being able to formulate problems mathematically and to devise strategies for solving them using concepts and procedures appropriately. Applying involves using one’s conceptual and procedural knowledge to solve problems. A concept or procedure is not useful unless students recognize when and where to use it—as well as when and whether it does not apply. … Students …need to be able to pose problems, devise solution strategies, and choose the most useful strategy for solving problems. . ” p. 13 Source: National Research Council. (2002). Helping children learn mathematics. Mathematics Learning Study Committee, J. Kilpatrick & J. Swafford, Editors, Center for Education, Division of Behavioral and Social Sciences and Education. Washington, DC: National Academy Press. www. interventioncentral. org 9

Response to Intervention Five Strands of Mathematical Proficiency “ 4. Reasoning: Using logic to explain and justify a solution to a problem or to extend from something known to something less known. Reasoning is the glue that holds mathematics together. By thinking about the logical relationships between concepts and situations, students can navigate through the elements of a problem and see how they fit together. One of the best ways for students to improve their reasoning is to explain or justify their solutions to others. …Reasoning interacts strongly with the other strands of mathematical thought, especially when students are (2002). Helping children learn mathematics. Source: National Research Council. solving problems. ” p. 14 Mathematics Learning Study Committee, J. Kilpatrick & J. Swafford, Editors, Center for Education, Division of Behavioral and Social Sciences and Education. Washington, DC: National Academy Press. www. interventioncentral. org 10

Response to Intervention Five Strands of Mathematical Proficiency “ 4. Reasoning: Using logic to explain and justify a solution to a problem or to extend from something known to something less known. Reasoning is the glue that holds mathematics together. By thinking about the logical relationships between concepts and situations, students can navigate through the elements of a problem and see how they fit together. One of the best ways for students to improve their reasoning is to explain or justify their solutions to others. …Reasoning interacts strongly with the other strands of mathematical thought, especially when students are (2002). Helping children learn mathematics. Source: National Research Council. solving problems. ” p. 14 Mathematics Learning Study Committee, J. Kilpatrick & J. Swafford, Editors, Center for Education, Division of Behavioral and Social Sciences and Education. Washington, DC: National Academy Press. www. interventioncentral. org 10

Response to Intervention Five Strands of Mathematical Proficiency “ 5. Engaging: Seeing mathematics as sensible, useful, and doable—if you work at it—and being willing to do the work. Engaging in mathematical activity is the key to success. Our view of mathematical proficiency goes beyond being able to understand, compute, apply, and reason. It includes engagement with mathematics. Students should have a personal commitment to the idea that mathematics makes sens and that—given reasonable effort—they can learn it and use it both in school and outside school. . ” p. 15 -16 Source: National Research Council. (2002). Helping children learn mathematics. Mathematics Learning Study Committee, J. Kilpatrick & J. Swafford, Editors, Center for Education, Division of Behavioral and Social Sciences and Education. Washington, DC: National Academy Press. www. interventioncentral. org 11

Response to Intervention Five Strands of Mathematical Proficiency “ 5. Engaging: Seeing mathematics as sensible, useful, and doable—if you work at it—and being willing to do the work. Engaging in mathematical activity is the key to success. Our view of mathematical proficiency goes beyond being able to understand, compute, apply, and reason. It includes engagement with mathematics. Students should have a personal commitment to the idea that mathematics makes sens and that—given reasonable effort—they can learn it and use it both in school and outside school. . ” p. 15 -16 Source: National Research Council. (2002). Helping children learn mathematics. Mathematics Learning Study Committee, J. Kilpatrick & J. Swafford, Editors, Center for Education, Division of Behavioral and Social Sciences and Education. Washington, DC: National Academy Press. www. interventioncentral. org 11

Response to Intervention Three General Levels of Math Skill Development (Kroesbergen & Van Luit, 2003) As students move from lower to higher grades, they move through levels of acquisition of math skills, to include: • Number sense • Basic math operations (i. e. , addition, subtraction, multiplication, division) • Problem-solving skills: “The solution of both verbal and nonverbal problems through the application of previously acquired information” (Kroesbergen & Van Luit, 2003, p. 98) Source: Kroesbergen, E. , & Van Luit, J. E. H. (2003). Mathematics interventions for children with special educational needs. Remedial and Special Education, 24, 97 -114. . www. interventioncentral. org 12

Response to Intervention Three General Levels of Math Skill Development (Kroesbergen & Van Luit, 2003) As students move from lower to higher grades, they move through levels of acquisition of math skills, to include: • Number sense • Basic math operations (i. e. , addition, subtraction, multiplication, division) • Problem-solving skills: “The solution of both verbal and nonverbal problems through the application of previously acquired information” (Kroesbergen & Van Luit, 2003, p. 98) Source: Kroesbergen, E. , & Van Luit, J. E. H. (2003). Mathematics interventions for children with special educational needs. Remedial and Special Education, 24, 97 -114. . www. interventioncentral. org 12

Response to Intervention What is ‘Number Sense’? (Clarke & Shinn, 2004) “… the ability to understand the meaning of numbers and define different relationships among numbers. Children with number sense can recognize the relative size of numbers, use referents for measuring objects and events, and think and work with numbers in a flexible manner that treats numbers as a sensible system. ” p. 236 Source: Clarke, B. , & Shinn, M. (2004). A preliminary investigation into the identification and development of early mathematics curriculum-based measurement. School Psychology Review, 33, 234 – 248. www. interventioncentral. org 13

Response to Intervention What is ‘Number Sense’? (Clarke & Shinn, 2004) “… the ability to understand the meaning of numbers and define different relationships among numbers. Children with number sense can recognize the relative size of numbers, use referents for measuring objects and events, and think and work with numbers in a flexible manner that treats numbers as a sensible system. ” p. 236 Source: Clarke, B. , & Shinn, M. (2004). A preliminary investigation into the identification and development of early mathematics curriculum-based measurement. School Psychology Review, 33, 234 – 248. www. interventioncentral. org 13

Response to Intervention What Are Stages of ‘Number Sense’? (Berch, 2005, p. 336) 1. Innate Number Sense. Children appear to possess ‘hard-wired’ ability (neurological ‘foundation structures’) to acquire number sense. Children’s innate capabilities appear also to be to ‘represent general amounts’, not specific quantities. This innate number sense seems to be characterized by skills at estimation (‘approximate numerical judgments’) and a counting system that can be described loosely as ‘ 1, 2, 3, 4, … a lot’. 2. Acquired Number Sense. Young students learn through indirect and direct instruction to count specific objects beyond four and to internalize a number line as a mental representation of those Source: Berch, D. B. (2005). Making sense of number sense: Implications for children with mathematical precise number values. disabilities. Journal of Learning Disabilities, 38, 333 -339. . . www. interventioncentral. org 14

Response to Intervention What Are Stages of ‘Number Sense’? (Berch, 2005, p. 336) 1. Innate Number Sense. Children appear to possess ‘hard-wired’ ability (neurological ‘foundation structures’) to acquire number sense. Children’s innate capabilities appear also to be to ‘represent general amounts’, not specific quantities. This innate number sense seems to be characterized by skills at estimation (‘approximate numerical judgments’) and a counting system that can be described loosely as ‘ 1, 2, 3, 4, … a lot’. 2. Acquired Number Sense. Young students learn through indirect and direct instruction to count specific objects beyond four and to internalize a number line as a mental representation of those Source: Berch, D. B. (2005). Making sense of number sense: Implications for children with mathematical precise number values. disabilities. Journal of Learning Disabilities, 38, 333 -339. . . www. interventioncentral. org 14

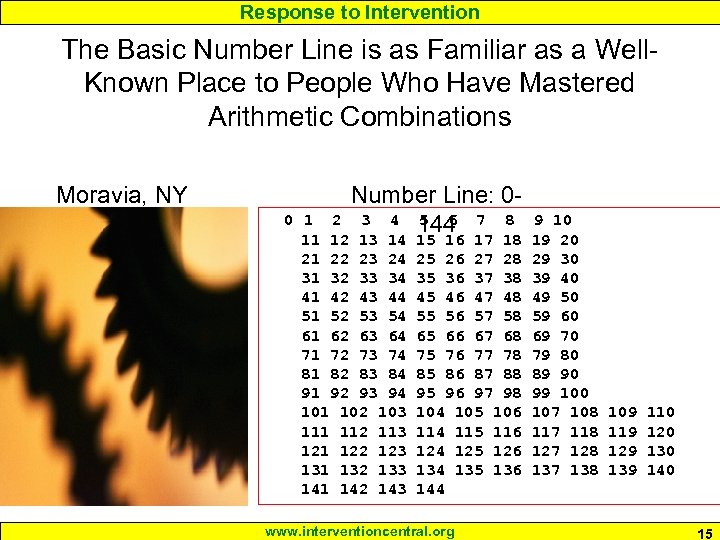

Response to Intervention The Basic Number Line is as Familiar as a Well. Known Place to People Who Have Mastered Arithmetic Combinations Moravia, NY Number Line: 03 4 144 7 8 5 6 0 1 2 11 12 13 14 21 22 23 24 31 32 33 34 41 42 43 44 51 52 53 54 61 62 63 64 71 72 73 74 81 82 83 84 91 92 93 94 101 102 103 111 112 113 121 122 123 131 132 133 141 142 143 15 16 17 18 25 26 27 28 35 36 37 38 45 46 47 48 55 56 57 58 65 66 67 68 75 76 77 78 85 86 87 88 95 96 97 98 104 105 106 114 115 116 124 125 126 134 135 136 144 www. interventioncentral. org 9 10 19 20 29 30 39 40 49 50 59 60 69 70 79 80 89 90 99 100 107 108 117 118 127 128 137 138 109 119 129 139 110 120 130 140 15

Response to Intervention The Basic Number Line is as Familiar as a Well. Known Place to People Who Have Mastered Arithmetic Combinations Moravia, NY Number Line: 03 4 144 7 8 5 6 0 1 2 11 12 13 14 21 22 23 24 31 32 33 34 41 42 43 44 51 52 53 54 61 62 63 64 71 72 73 74 81 82 83 84 91 92 93 94 101 102 103 111 112 113 121 122 123 131 132 133 141 142 143 15 16 17 18 25 26 27 28 35 36 37 38 45 46 47 48 55 56 57 58 65 66 67 68 75 76 77 78 85 86 87 88 95 96 97 98 104 105 106 114 115 116 124 125 126 134 135 136 144 www. interventioncentral. org 9 10 19 20 29 30 39 40 49 50 59 60 69 70 79 80 89 90 99 100 107 108 117 118 127 128 137 138 109 119 129 139 110 120 130 140 15

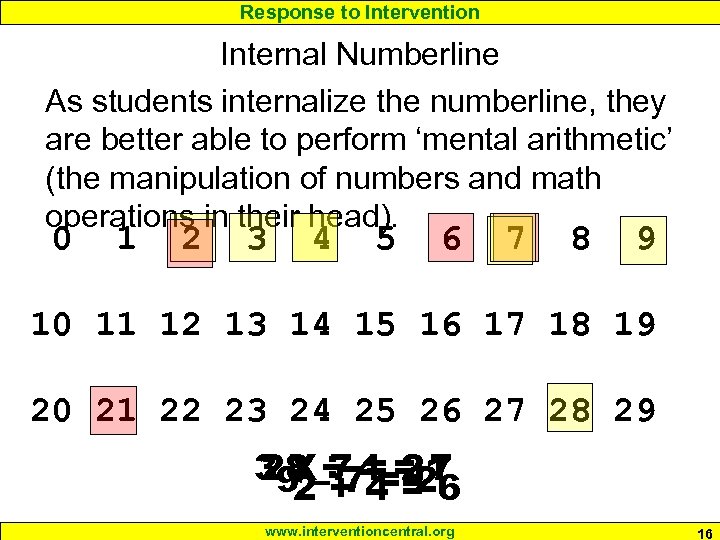

Response to Intervention Internal Numberline As students internalize the numberline, they are better able to perform ‘mental arithmetic’ (the manipulation of numbers and math operations in their head). 0 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 39 – 7 4=21 28 ÷ 7= =2 X 7 2+4=6 www. interventioncentral. org 16

Response to Intervention Internal Numberline As students internalize the numberline, they are better able to perform ‘mental arithmetic’ (the manipulation of numbers and math operations in their head). 0 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 39 – 7 4=21 28 ÷ 7= =2 X 7 2+4=6 www. interventioncentral. org 16

Response to Intervention Mental Arithmetic: A Demonstration 332 x 420 = ? Directions: As you watch this video of a person using mental arithmetic to solve a computation problem, note the strategies and ‘shortcuts’ that he employs to make the task more manageable. www. interventioncentral. org 17

Response to Intervention Mental Arithmetic: A Demonstration 332 x 420 = ? Directions: As you watch this video of a person using mental arithmetic to solve a computation problem, note the strategies and ‘shortcuts’ that he employs to make the task more manageable. www. interventioncentral. org 17

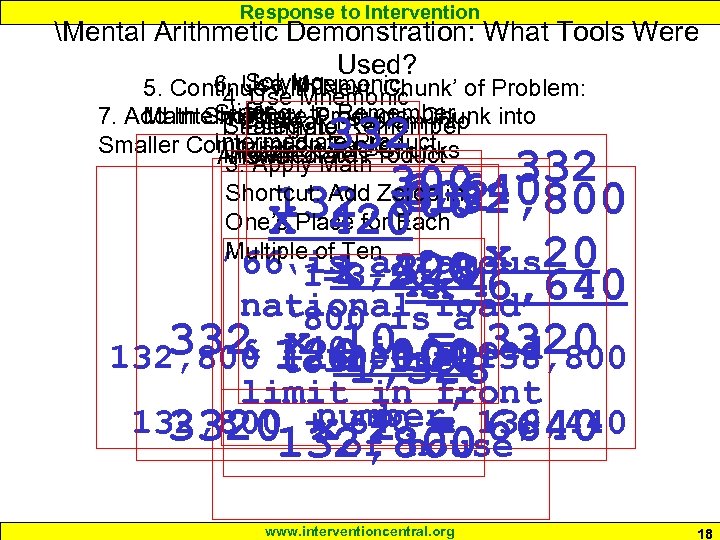

Response to Intervention Mental Arithmetic Demonstration: What Tools Were Used? Solving 6. Use Mnemonic 5. Continue with Next ‘Chunk’ of Problem: 4. Use Mnemonic for… Strategy Remember 7. Add Intermediate to Problem. Chunk into Math Shortcut Products: into 2. Break Remember Strategy to 1. Estimate Intermediate Product Smaller Computation Tasks Manageable Intermediate Product Answer Math Chunks 3. Apply Shortcut: Add Zeros in One’s Place for Each Multiple of Ten 332 300 6, 640 332 132, 800 X 420 ’ 66‘ 1=3 -2’ & x 20 is a 400 famous x xx 46, 640 1, 328 national road’ ‘ 800 is a 332 toll-free 3320 x x is = 10 speed & + 6000 = ’ 40 100 132, 800 120, 000 138, 800 1, 328 limit in front number’ 6640 132, 800 + 640 = 139, 440 3320132, 800 ’ xof house 2 = www. interventioncentral. org 18

Response to Intervention Mental Arithmetic Demonstration: What Tools Were Used? Solving 6. Use Mnemonic 5. Continue with Next ‘Chunk’ of Problem: 4. Use Mnemonic for… Strategy Remember 7. Add Intermediate to Problem. Chunk into Math Shortcut Products: into 2. Break Remember Strategy to 1. Estimate Intermediate Product Smaller Computation Tasks Manageable Intermediate Product Answer Math Chunks 3. Apply Shortcut: Add Zeros in One’s Place for Each Multiple of Ten 332 300 6, 640 332 132, 800 X 420 ’ 66‘ 1=3 -2’ & x 20 is a 400 famous x xx 46, 640 1, 328 national road’ ‘ 800 is a 332 toll-free 3320 x x is = 10 speed & + 6000 = ’ 40 100 132, 800 120, 000 138, 800 1, 328 limit in front number’ 6640 132, 800 + 640 = 139, 440 3320132, 800 ’ xof house 2 = www. interventioncentral. org 18

Response to Intervention Math Computation: Building Fluency Jim Wright www. interventioncentral. org

Response to Intervention Math Computation: Building Fluency Jim Wright www. interventioncentral. org

Response to Intervention "Arithmetic is being able to count up to twenty without taking off your shoes. " –Anonymous www. interventioncentral. org 20

Response to Intervention "Arithmetic is being able to count up to twenty without taking off your shoes. " –Anonymous www. interventioncentral. org 20

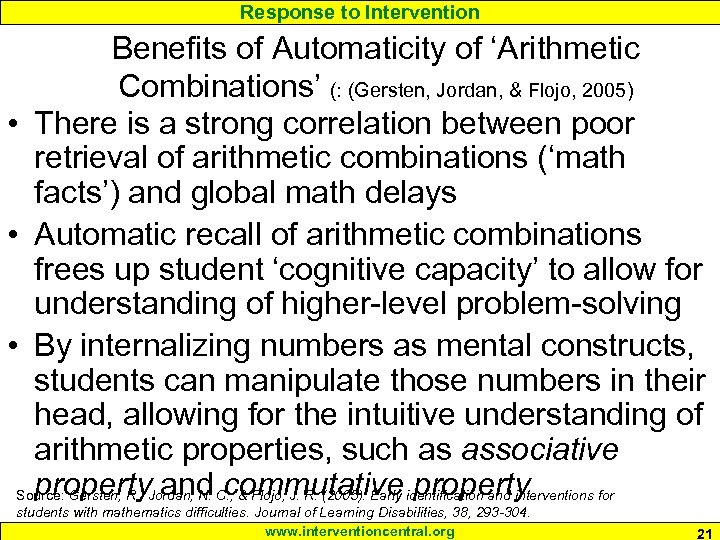

Response to Intervention Benefits of Automaticity of ‘Arithmetic Combinations’ (: (Gersten, Jordan, & Flojo, 2005) • There is a strong correlation between poor retrieval of arithmetic combinations (‘math facts’) and global math delays • Automatic recall of arithmetic combinations frees up student ‘cognitive capacity’ to allow for understanding of higher-level problem-solving • By internalizing numbers as mental constructs, students can manipulate those numbers in their head, allowing for the intuitive understanding of arithmetic properties, such as associative property and commutative property Source: Gersten, R. , Jordan, N. C. , & Flojo, J. R. (2005). Early identification and interventions for students with mathematics difficulties. Journal of Learning Disabilities, 38, 293 -304. www. interventioncentral. org 21

Response to Intervention Benefits of Automaticity of ‘Arithmetic Combinations’ (: (Gersten, Jordan, & Flojo, 2005) • There is a strong correlation between poor retrieval of arithmetic combinations (‘math facts’) and global math delays • Automatic recall of arithmetic combinations frees up student ‘cognitive capacity’ to allow for understanding of higher-level problem-solving • By internalizing numbers as mental constructs, students can manipulate those numbers in their head, allowing for the intuitive understanding of arithmetic properties, such as associative property and commutative property Source: Gersten, R. , Jordan, N. C. , & Flojo, J. R. (2005). Early identification and interventions for students with mathematics difficulties. Journal of Learning Disabilities, 38, 293 -304. www. interventioncentral. org 21

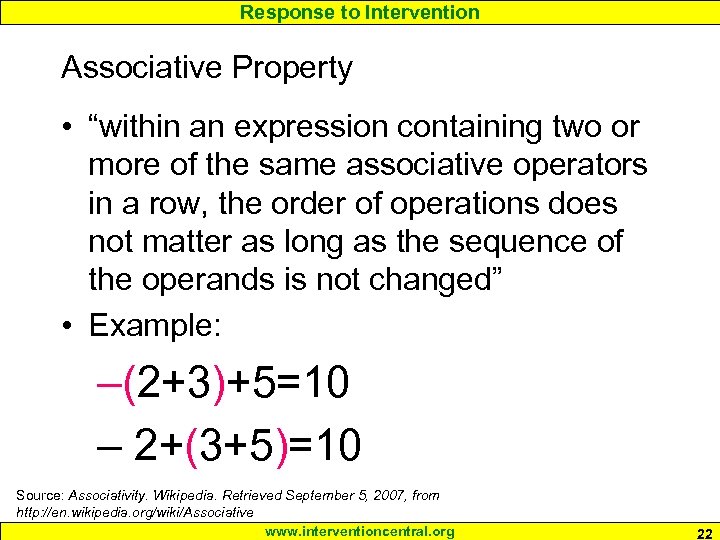

Response to Intervention Associative Property • “within an expression containing two or more of the same associative operators in a row, the order of operations does not matter as long as the sequence of the operands is not changed” • Example: –(2+3)+5=10 – 2+(3+5)=10 Source: Associativity. Wikipedia. Retrieved September 5, 2007, from http: //en. wikipedia. org/wiki/Associative www. interventioncentral. org 22

Response to Intervention Associative Property • “within an expression containing two or more of the same associative operators in a row, the order of operations does not matter as long as the sequence of the operands is not changed” • Example: –(2+3)+5=10 – 2+(3+5)=10 Source: Associativity. Wikipedia. Retrieved September 5, 2007, from http: //en. wikipedia. org/wiki/Associative www. interventioncentral. org 22

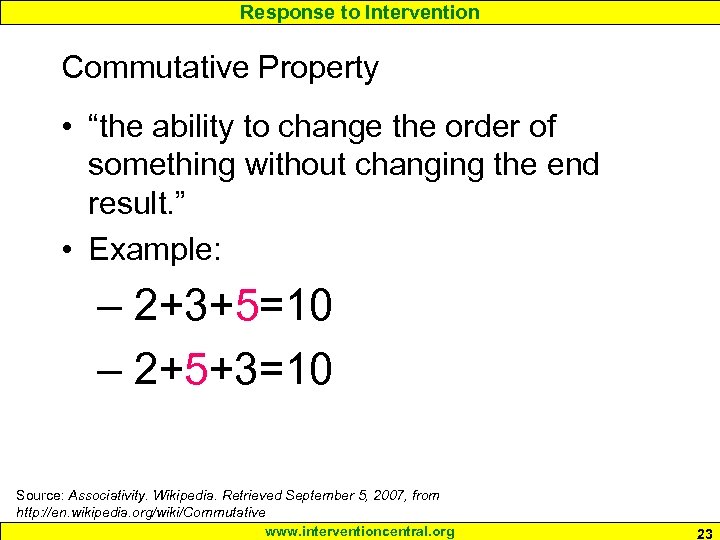

Response to Intervention Commutative Property • “the ability to change the order of something without changing the end result. ” • Example: – 2+3+5=10 – 2+5+3=10 Source: Associativity. Wikipedia. Retrieved September 5, 2007, from http: //en. wikipedia. org/wiki/Commutative www. interventioncentral. org 23

Response to Intervention Commutative Property • “the ability to change the order of something without changing the end result. ” • Example: – 2+3+5=10 – 2+5+3=10 Source: Associativity. Wikipedia. Retrieved September 5, 2007, from http: //en. wikipedia. org/wiki/Commutative www. interventioncentral. org 23

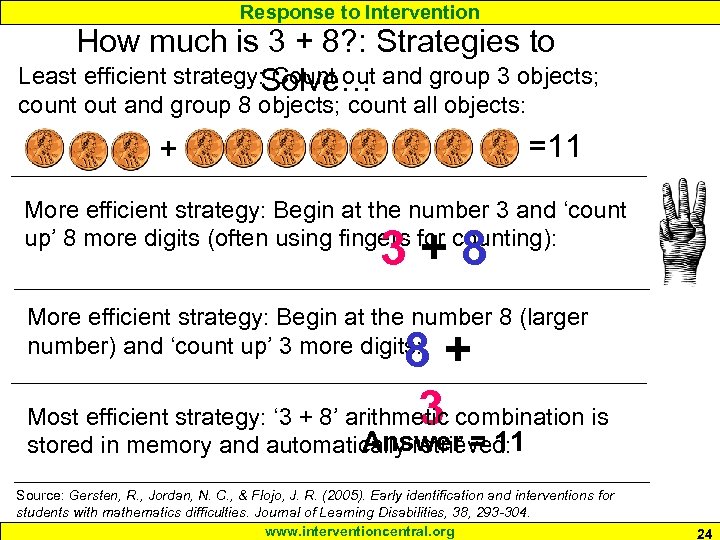

Response to Intervention How much is 3 + 8? : Strategies to Least efficient strategy: Count out and group 3 objects; Solve… count out and group 8 objects; count all objects: =11 + More efficient strategy: Begin at the number 3 and ‘count up’ 8 more digits (often using fingers for counting): 3+8 More efficient strategy: Begin at the number 8 (larger number) and ‘count up’ 3 more digits: 8+ 3 Most efficient strategy: ‘ 3 + 8’ arithmetic combination is Answer = 11 stored in memory and automatically retrieved: Source: Gersten, R. , Jordan, N. C. , & Flojo, J. R. (2005). Early identification and interventions for students with mathematics difficulties. Journal of Learning Disabilities, 38, 293 -304. www. interventioncentral. org 24

Response to Intervention How much is 3 + 8? : Strategies to Least efficient strategy: Count out and group 3 objects; Solve… count out and group 8 objects; count all objects: =11 + More efficient strategy: Begin at the number 3 and ‘count up’ 8 more digits (often using fingers for counting): 3+8 More efficient strategy: Begin at the number 8 (larger number) and ‘count up’ 3 more digits: 8+ 3 Most efficient strategy: ‘ 3 + 8’ arithmetic combination is Answer = 11 stored in memory and automatically retrieved: Source: Gersten, R. , Jordan, N. C. , & Flojo, J. R. (2005). Early identification and interventions for students with mathematics difficulties. Journal of Learning Disabilities, 38, 293 -304. www. interventioncentral. org 24

Response to Intervention Math Skills: Importance of Fluency in Basic Math Operations “[A key step in math education is] to learn the four basic mathematical operations (i. e. , addition, subtraction, multiplication, and division). Knowledge of these operations and a capacity to perform mental arithmetic play an important role in the development of children’s later math skills. Most children with math learning difficulties are unable to master the four basic operations before leaving elementary school and, thus, need special attention to acquire the skills. A … category of Source: Kroesbergen, E. , & Van Luit, J. E. H. (2003). Mathematics interventions for children with special interventions is therefore aimed at the educational needs. Remedial and Special Education, 24, 97 -114. acquisition and automatization of basic math www. interventioncentral. org 25

Response to Intervention Math Skills: Importance of Fluency in Basic Math Operations “[A key step in math education is] to learn the four basic mathematical operations (i. e. , addition, subtraction, multiplication, and division). Knowledge of these operations and a capacity to perform mental arithmetic play an important role in the development of children’s later math skills. Most children with math learning difficulties are unable to master the four basic operations before leaving elementary school and, thus, need special attention to acquire the skills. A … category of Source: Kroesbergen, E. , & Van Luit, J. E. H. (2003). Mathematics interventions for children with special interventions is therefore aimed at the educational needs. Remedial and Special Education, 24, 97 -114. acquisition and automatization of basic math www. interventioncentral. org 25

Response to Intervention Big Ideas: Learn Unit (Heward, 1996) The three essential elements of effective student learning include: 1. Academic Opportunity to Respond. The student is presented with a meaningful opportunity to respond to an academic task. A question posed by the teacher, a math word problem, and a spelling item on an educational computer ‘Word Gobbler’ game could all be considered academic opportunities to respond. 2. Active Student Response. The student answers the item, solves the problem presented, or completes the academic task. Answering the teacher’s question, computing the answer to a math word problem (and showing all work), and typing in the correct spelling of an item when playing an educational computer game are all examples of active student responding. 3. Performance Feedback. The student receives timely feedback about whether his or her response is correct—often with praise and encouragement. A teacher exclaiming ‘Right! Good job!’ when a student gives an response in class, a student using an answer key Source: Heward, W. L. (1996). Three to a math word problem, and a computer to check her answer low-tech strategies for increasing the frequency of active student response during group instruction. In R. Gardner, D. M. S ainato, J. O. Cooper, T. E. Heron, W. L. Heward, J. message Grossi (Eds. ), Behavior analysis in education: Focus points for superior W. Eshleman, & T. A. that says ‘Congratulations! You get 2 on measurablycorrectly spelling this Pacific Grove, www. interventioncentral. org all examples instruction (pp. 283 -320). word!” are CA: Brooks/Cole. of performance feedback. 26

Response to Intervention Big Ideas: Learn Unit (Heward, 1996) The three essential elements of effective student learning include: 1. Academic Opportunity to Respond. The student is presented with a meaningful opportunity to respond to an academic task. A question posed by the teacher, a math word problem, and a spelling item on an educational computer ‘Word Gobbler’ game could all be considered academic opportunities to respond. 2. Active Student Response. The student answers the item, solves the problem presented, or completes the academic task. Answering the teacher’s question, computing the answer to a math word problem (and showing all work), and typing in the correct spelling of an item when playing an educational computer game are all examples of active student responding. 3. Performance Feedback. The student receives timely feedback about whether his or her response is correct—often with praise and encouragement. A teacher exclaiming ‘Right! Good job!’ when a student gives an response in class, a student using an answer key Source: Heward, W. L. (1996). Three to a math word problem, and a computer to check her answer low-tech strategies for increasing the frequency of active student response during group instruction. In R. Gardner, D. M. S ainato, J. O. Cooper, T. E. Heron, W. L. Heward, J. message Grossi (Eds. ), Behavior analysis in education: Focus points for superior W. Eshleman, & T. A. that says ‘Congratulations! You get 2 on measurablycorrectly spelling this Pacific Grove, www. interventioncentral. org all examples instruction (pp. 283 -320). word!” are CA: Brooks/Cole. of performance feedback. 26

Response to Intervention Math Intervention: Tier I or II: Elementary & Secondary: Self-Administered Arithmetic Combination Drills With Performance Self-Monitoring & Incentives 1. The student is given a math computation worksheet of a specific problem type, along with an answer key [Academic Opportunity to Respond]. 2. The student consults his or her performance chart and notes previous performance. The student is encouraged to try to ‘beat’ his or her most recent score. 3. The student is given a pre-selected amount of time (e. g. , 5 minutes) to complete as many problems as possible. The student sets a timer and works on the computation sheet until the timer rings. [Active Student Responding] 4. The student checks his or her work, giving credit for each correct digit (digit of correct value appearing in the correct place-position in the answer). [Performance Feedback] 5. The student records the day’s score of TOTAL number of correct digits on his or her personal performance chart. Application of ‘Learn Unit’ framework from : Heward, W. L. (1996). Three low-tech strategies for increasing the 6. The student receives praise or a reward if Gardner, D. M. S ainato, J. the most frequency of active student response during group instruction. In R. he or she exceeds O. Cooper, T. E. Heron, recently posted number. T. A. correct digits. W. L. Heward, J. W. Eshleman, & of Grossi (Eds. ), Behavior analysis in education: Focus on measurably superior instruction (pp. 283 -320). Pacific Grove, CA: Brooks/Cole. www. interventioncentral. org 27

Response to Intervention Math Intervention: Tier I or II: Elementary & Secondary: Self-Administered Arithmetic Combination Drills With Performance Self-Monitoring & Incentives 1. The student is given a math computation worksheet of a specific problem type, along with an answer key [Academic Opportunity to Respond]. 2. The student consults his or her performance chart and notes previous performance. The student is encouraged to try to ‘beat’ his or her most recent score. 3. The student is given a pre-selected amount of time (e. g. , 5 minutes) to complete as many problems as possible. The student sets a timer and works on the computation sheet until the timer rings. [Active Student Responding] 4. The student checks his or her work, giving credit for each correct digit (digit of correct value appearing in the correct place-position in the answer). [Performance Feedback] 5. The student records the day’s score of TOTAL number of correct digits on his or her personal performance chart. Application of ‘Learn Unit’ framework from : Heward, W. L. (1996). Three low-tech strategies for increasing the 6. The student receives praise or a reward if Gardner, D. M. S ainato, J. the most frequency of active student response during group instruction. In R. he or she exceeds O. Cooper, T. E. Heron, recently posted number. T. A. correct digits. W. L. Heward, J. W. Eshleman, & of Grossi (Eds. ), Behavior analysis in education: Focus on measurably superior instruction (pp. 283 -320). Pacific Grove, CA: Brooks/Cole. www. interventioncentral. org 27

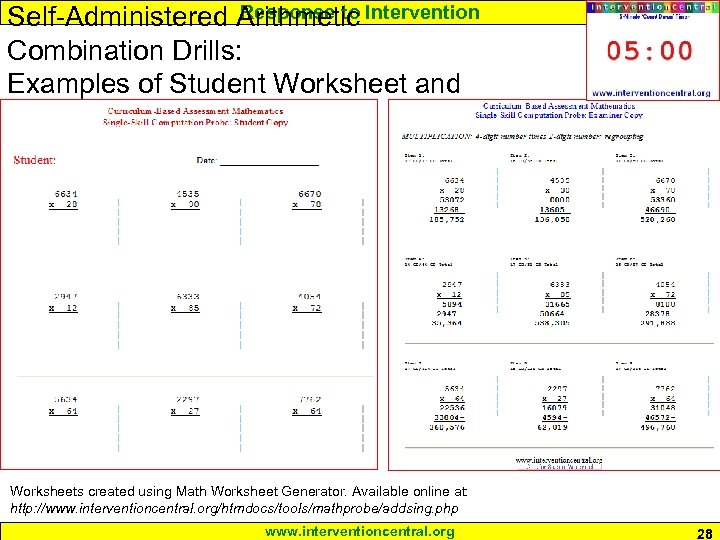

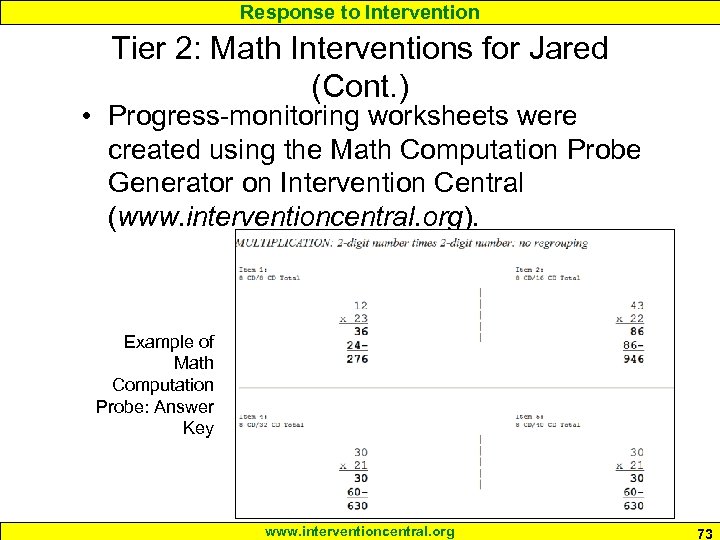

Response to Self-Administered Arithmetic Intervention Combination Drills: Examples of Student Worksheet and Answer Key Worksheets created using Math Worksheet Generator. Available online at: http: //www. interventioncentral. org/htmdocs/tools/mathprobe/addsing. php www. interventioncentral. org 28

Response to Self-Administered Arithmetic Intervention Combination Drills: Examples of Student Worksheet and Answer Key Worksheets created using Math Worksheet Generator. Available online at: http: //www. interventioncentral. org/htmdocs/tools/mathprobe/addsing. php www. interventioncentral. org 28

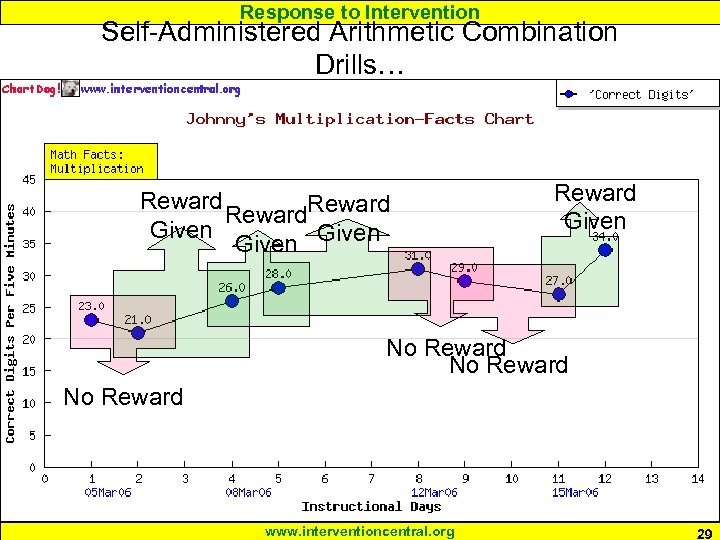

Response to Intervention Self-Administered Arithmetic Combination Drills… Reward Given Reward Given No Reward www. interventioncentral. org 29

Response to Intervention Self-Administered Arithmetic Combination Drills… Reward Given Reward Given No Reward www. interventioncentral. org 29

Response to Intervention How to… Use PPT Group Timers in the Classroom www. interventioncentral. org 30

Response to Intervention How to… Use PPT Group Timers in the Classroom www. interventioncentral. org 30

Response to Intervention Math Shortcuts: Cognitive Energy- and Time. Savers “Recently, some researchers…have argued that children can derive answers quickly and with minimal cognitive effort by employing calculation principles or “shortcuts, ” such as using a known number combination toderive an answer (2 + 2 = 4, so 2 + 3 =5), relations among operations (6 + 4 =10, so 10 − 4 = 6), n+ 1, commutativity, and so forth. This approach to instruction is consonant with recommendations by the National Research Council (2001). Instruction along these linesmay be much more productive than rote drill without & Flojo, J. R. to Early identification and interventions for Source: Gersten, R. , Jordan, N. C. , linkage(2005). counting strategy use. ” p. 301 students with mathematics difficulties. Journal of Learning Disabilities, 38, 293 -304. www. interventioncentral. org 31

Response to Intervention Math Shortcuts: Cognitive Energy- and Time. Savers “Recently, some researchers…have argued that children can derive answers quickly and with minimal cognitive effort by employing calculation principles or “shortcuts, ” such as using a known number combination toderive an answer (2 + 2 = 4, so 2 + 3 =5), relations among operations (6 + 4 =10, so 10 − 4 = 6), n+ 1, commutativity, and so forth. This approach to instruction is consonant with recommendations by the National Research Council (2001). Instruction along these linesmay be much more productive than rote drill without & Flojo, J. R. to Early identification and interventions for Source: Gersten, R. , Jordan, N. C. , linkage(2005). counting strategy use. ” p. 301 students with mathematics difficulties. Journal of Learning Disabilities, 38, 293 -304. www. interventioncentral. org 31

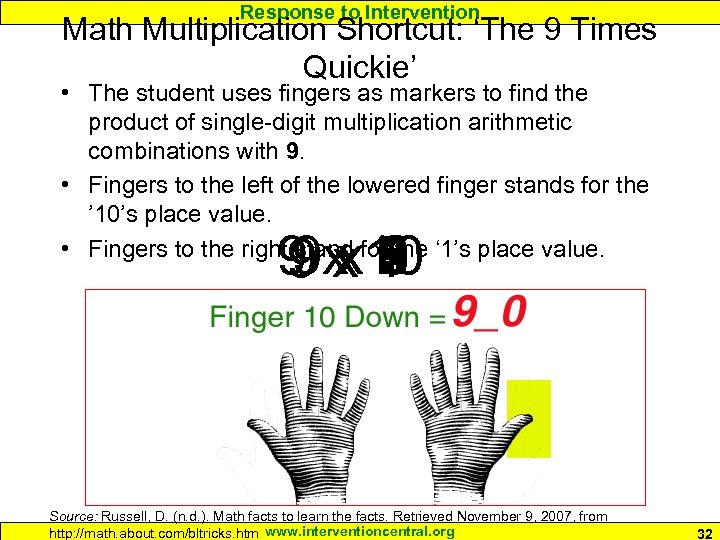

Response to Intervention Math Multiplication Shortcut: ‘The 9 Times Quickie’ • The student uses fingers as markers to find the product of single-digit multiplication arithmetic combinations with 9. • Fingers to the left of the lowered finger stands for the ’ 10’s place value. • Fingers to the right stand for the ‘ 1’s place value. 9 x 10 9 x 1 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 Source: Russell, D. (n. d. ). Math facts to learn the facts. Retrieved November 9, 2007, from http: //math. about. com/bltricks. htm www. interventioncentral. org 32

Response to Intervention Math Multiplication Shortcut: ‘The 9 Times Quickie’ • The student uses fingers as markers to find the product of single-digit multiplication arithmetic combinations with 9. • Fingers to the left of the lowered finger stands for the ’ 10’s place value. • Fingers to the right stand for the ‘ 1’s place value. 9 x 10 9 x 1 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 Source: Russell, D. (n. d. ). Math facts to learn the facts. Retrieved November 9, 2007, from http: //math. about. com/bltricks. htm www. interventioncentral. org 32

Response to Intervention Students Who ‘Understand’ Mathematical Concepts Can Discover Their Own ‘Shortcuts’ “Students who learn with understanding have less to learn because they see common patterns in superfically different sicuations. If they understand the general principle that the order in which two numbers are multiplied doesn’t matter— 3 x 5 is the same as 5 x 3, for example—they have about half as many ‘number facts’ to learn. ” p. 10 Source: National Research Council. (2002). Helping children learn mathematics. Mathematics Learning Study Committee, J. Kilpatrick & J. Swafford, Editors, Center for Education, Division of Behavioral and Social Sciences and Education. Washington, DC: National Academy Press. www. interventioncentral. org 33

Response to Intervention Students Who ‘Understand’ Mathematical Concepts Can Discover Their Own ‘Shortcuts’ “Students who learn with understanding have less to learn because they see common patterns in superfically different sicuations. If they understand the general principle that the order in which two numbers are multiplied doesn’t matter— 3 x 5 is the same as 5 x 3, for example—they have about half as many ‘number facts’ to learn. ” p. 10 Source: National Research Council. (2002). Helping children learn mathematics. Mathematics Learning Study Committee, J. Kilpatrick & J. Swafford, Editors, Center for Education, Division of Behavioral and Social Sciences and Education. Washington, DC: National Academy Press. www. interventioncentral. org 33

Response to Intervention Application of Math Shortcuts to Intervention Plans • Students who struggle with may find computational ‘shortcuts’ to be motivating. • Teaching and modeling of shortcuts provides students with strategies to make computation less ‘cognitively demanding’. www. interventioncentral. org 34

Response to Intervention Application of Math Shortcuts to Intervention Plans • Students who struggle with may find computational ‘shortcuts’ to be motivating. • Teaching and modeling of shortcuts provides students with strategies to make computation less ‘cognitively demanding’. www. interventioncentral. org 34

Response to Intervention Math Computation: Motivate With ‘Errorless Learning’ Worksheets In this version of an ‘errorless learning’ approach, the student is directed to complete math facts as quickly as possible. If the student comes to a number problem that he or she cannot solve, the student is encouraged to locate the problem and its correct answer in the key at the top of the page and write it in. Such speed drills build computational fluency while promoting students’ ability to visualize and to use a mental number line. TIP: Consider turning this activity into a ‘speed drill’. The student is given a kitchen timer and instructed to set the timer for a predetermined span of time (e. g. , 2 minutes) for each drill. The student completes as many problems as possible before the timer rings. The student then Source: Caron, T. A. (2007). Learning multiplication the easy way. The Clearing House, 80, 278 -282 graphs the number of problems correctly computed each www. interventioncentral. org 35

Response to Intervention Math Computation: Motivate With ‘Errorless Learning’ Worksheets In this version of an ‘errorless learning’ approach, the student is directed to complete math facts as quickly as possible. If the student comes to a number problem that he or she cannot solve, the student is encouraged to locate the problem and its correct answer in the key at the top of the page and write it in. Such speed drills build computational fluency while promoting students’ ability to visualize and to use a mental number line. TIP: Consider turning this activity into a ‘speed drill’. The student is given a kitchen timer and instructed to set the timer for a predetermined span of time (e. g. , 2 minutes) for each drill. The student completes as many problems as possible before the timer rings. The student then Source: Caron, T. A. (2007). Learning multiplication the easy way. The Clearing House, 80, 278 -282 graphs the number of problems correctly computed each www. interventioncentral. org 35

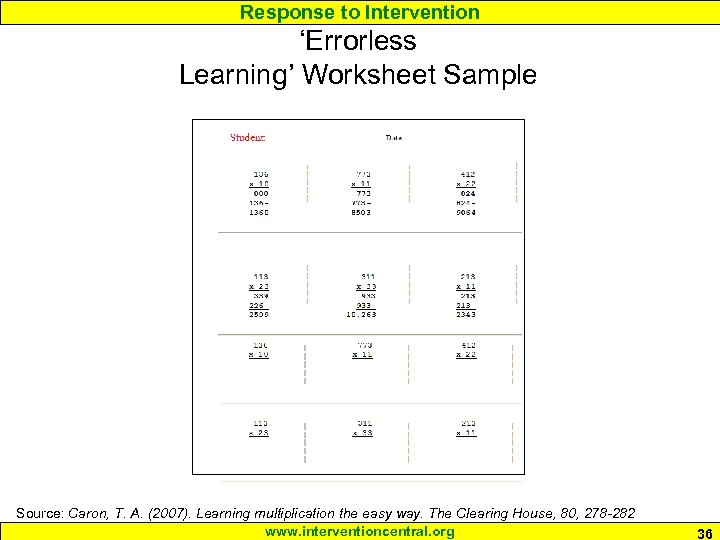

Response to Intervention ‘Errorless Learning’ Worksheet Sample Source: Caron, T. A. (2007). Learning multiplication the easy way. The Clearing House, 80, 278 -282 www. interventioncentral. org 36

Response to Intervention ‘Errorless Learning’ Worksheet Sample Source: Caron, T. A. (2007). Learning multiplication the easy way. The Clearing House, 80, 278 -282 www. interventioncentral. org 36

Response to Intervention Math Computation: Two Ideas to Jump-Start Active Academic Responding Here are two ideas to accomplish increased academic responding on math tasks. • Break longer assignments into shorter assignments with performance feedback given after each shorter ‘chunk’ (e. g. , break a 20 -minute math computation worksheet task into 3 seven-minute assignments). Breaking longer assignments into briefer segments also allows the teacher to praise struggling students more frequently for work completion and effort, providing an additional ‘natural’ reinforcer. • Allow students to respond to easier practice items orally rather than in written form to speed up the rate of correct responses. Source: Skinner, C. H. , Pappas, D. N. , & Davis, K. A. (2005). Enhancing academic engagement: Providing opportunities for responding and influencing students to choose to respond. Psychology in the Schools, 42, 389 -403. www. interventioncentral. org 37

Response to Intervention Math Computation: Two Ideas to Jump-Start Active Academic Responding Here are two ideas to accomplish increased academic responding on math tasks. • Break longer assignments into shorter assignments with performance feedback given after each shorter ‘chunk’ (e. g. , break a 20 -minute math computation worksheet task into 3 seven-minute assignments). Breaking longer assignments into briefer segments also allows the teacher to praise struggling students more frequently for work completion and effort, providing an additional ‘natural’ reinforcer. • Allow students to respond to easier practice items orally rather than in written form to speed up the rate of correct responses. Source: Skinner, C. H. , Pappas, D. N. , & Davis, K. A. (2005). Enhancing academic engagement: Providing opportunities for responding and influencing students to choose to respond. Psychology in the Schools, 42, 389 -403. www. interventioncentral. org 37

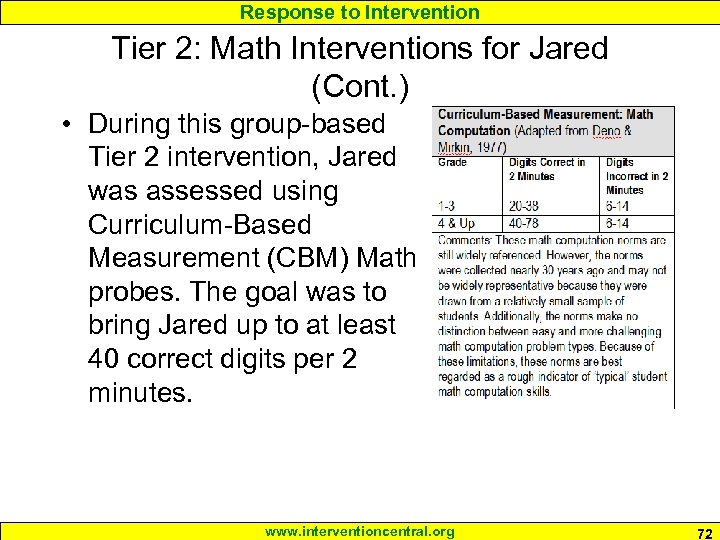

Response to Intervention Math Computation: Problem Interspersal Technique • The teacher first identifies the range of ‘challenging’ problem-types (number problems appropriately matched to the student’s current instructional level) that are to appear on the worksheet. • Then the teacher creates a series of ‘easy’ problems that the students can complete very quickly (e. g. , adding or subtracting two 1 -digit numbers). The teacher next prepares a series of student math computation worksheets with ‘easy’ computation problems interspersed at a fixed rate among the ‘challenging’ problems. • If the student is expected to complete the worksheet independently, ‘challenging’ and ‘easy’ problems should be interspersed at a 1: 1 ratio (that is, every ‘challenging’ problem in the worksheet is preceded and/or followed by an ‘easy’ problem). • If the student is to have the problems read aloud and then Skinner, to & Oliver, the problems mentally and additive Source: Hawkins, J. , asked. C. H. , solve R. (2005). The effects of task demands and write interspersaldown fifth-grade students’ mathematics accuracy. School Psychology Review, on 543 ratios on only the answer, the items should appear 34, the 555. . www. interventioncentral. org 38

Response to Intervention Math Computation: Problem Interspersal Technique • The teacher first identifies the range of ‘challenging’ problem-types (number problems appropriately matched to the student’s current instructional level) that are to appear on the worksheet. • Then the teacher creates a series of ‘easy’ problems that the students can complete very quickly (e. g. , adding or subtracting two 1 -digit numbers). The teacher next prepares a series of student math computation worksheets with ‘easy’ computation problems interspersed at a fixed rate among the ‘challenging’ problems. • If the student is expected to complete the worksheet independently, ‘challenging’ and ‘easy’ problems should be interspersed at a 1: 1 ratio (that is, every ‘challenging’ problem in the worksheet is preceded and/or followed by an ‘easy’ problem). • If the student is to have the problems read aloud and then Skinner, to & Oliver, the problems mentally and additive Source: Hawkins, J. , asked. C. H. , solve R. (2005). The effects of task demands and write interspersaldown fifth-grade students’ mathematics accuracy. School Psychology Review, on 543 ratios on only the answer, the items should appear 34, the 555. . www. interventioncentral. org 38

Response to Intervention How to… Create an Interspersal-Problems Worksheet www. interventioncentral. org 39

Response to Intervention How to… Create an Interspersal-Problems Worksheet www. interventioncentral. org 39

Response to Intervention Additional Math Interventions Jim Wright www. interventioncentral. org

Response to Intervention Additional Math Interventions Jim Wright www. interventioncentral. org

Response to Intervention Math Instruction: Unlock the Thoughts of Reluctant Students Through Class Journaling Students can effectively clarify their knowledge of math concepts and problem-solving strategies through regular use of class ‘math journals’. • At the start of the year, the teacher introduces the journaling weekly assignment in which students respond to teacher questions. • At first, the teacher presents ‘safe’ questions that tap into the students’ opinions and attitudes about mathematics (e. g. , ‘How important do you think it is nowadays for cashiers in fast-food restaurants to be able to calculate in their head the amount of change to give a customer? ”). As students become comfortable with the journaling activity, the teacher starts to pose questions about the students’ own mathematical thinking relating to specific assignments. Students are encouraged to use numerals, mathematical symbols, and diagrams in their journal entries to enhance their explanations. • The teacher provides brief written comments on individual student entries, as well as periodic oral feedback and encouragement to the entire class. • Teachers will find that journal entries are a concrete method for monitoring student understanding of more abstract math concepts. Source: Baxter, J. A. , Woodward, J. , & Olson, D. (2005). Writing in mathematics: An alternative form of To promote the quality of journal entries, the teacher & Practice, communication for academically low-achieving students. Learning Disabilities Researchmight also assign them an effort grade that will be calculated into quarterly math 41 20(2), 119– 135. www. interventioncentral. org

Response to Intervention Math Instruction: Unlock the Thoughts of Reluctant Students Through Class Journaling Students can effectively clarify their knowledge of math concepts and problem-solving strategies through regular use of class ‘math journals’. • At the start of the year, the teacher introduces the journaling weekly assignment in which students respond to teacher questions. • At first, the teacher presents ‘safe’ questions that tap into the students’ opinions and attitudes about mathematics (e. g. , ‘How important do you think it is nowadays for cashiers in fast-food restaurants to be able to calculate in their head the amount of change to give a customer? ”). As students become comfortable with the journaling activity, the teacher starts to pose questions about the students’ own mathematical thinking relating to specific assignments. Students are encouraged to use numerals, mathematical symbols, and diagrams in their journal entries to enhance their explanations. • The teacher provides brief written comments on individual student entries, as well as periodic oral feedback and encouragement to the entire class. • Teachers will find that journal entries are a concrete method for monitoring student understanding of more abstract math concepts. Source: Baxter, J. A. , Woodward, J. , & Olson, D. (2005). Writing in mathematics: An alternative form of To promote the quality of journal entries, the teacher & Practice, communication for academically low-achieving students. Learning Disabilities Researchmight also assign them an effort grade that will be calculated into quarterly math 41 20(2), 119– 135. www. interventioncentral. org

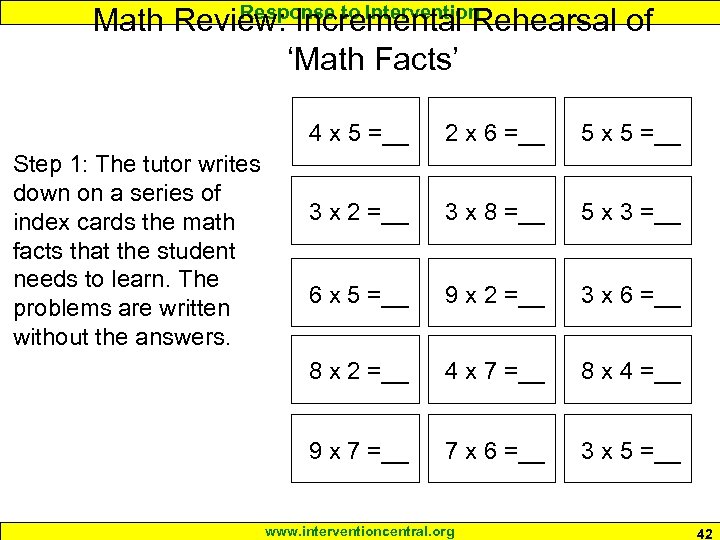

Response to Intervention Math Review: Incremental Rehearsal of ‘Math Facts’ 4 x 5 =__ Step 1: The tutor writes down on a series of index cards the math facts that the student needs to learn. The problems are written without the answers. 2 x 6 =__ 5 x 5 =__ 3 x 2 =__ 3 x 8 =__ 5 x 3 =__ 6 x 5 =__ 9 x 2 =__ 3 x 6 =__ 8 x 2 =__ 4 x 7 =__ 8 x 4 =__ 9 x 7 =__ 7 x 6 =__ 3 x 5 =__ www. interventioncentral. org 42

Response to Intervention Math Review: Incremental Rehearsal of ‘Math Facts’ 4 x 5 =__ Step 1: The tutor writes down on a series of index cards the math facts that the student needs to learn. The problems are written without the answers. 2 x 6 =__ 5 x 5 =__ 3 x 2 =__ 3 x 8 =__ 5 x 3 =__ 6 x 5 =__ 9 x 2 =__ 3 x 6 =__ 8 x 2 =__ 4 x 7 =__ 8 x 4 =__ 9 x 7 =__ 7 x 6 =__ 3 x 5 =__ www. interventioncentral. org 42

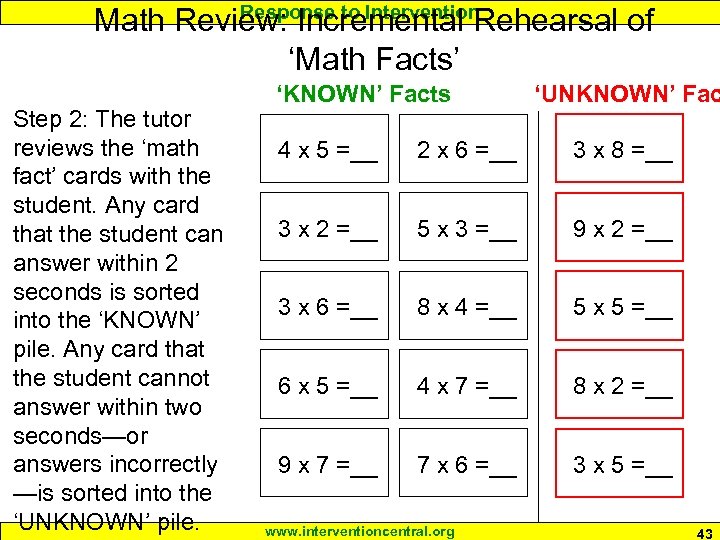

Response to Intervention Math Review: Incremental Rehearsal of ‘Math Facts’ Step 2: The tutor reviews the ‘math fact’ cards with the student. Any card that the student can answer within 2 seconds is sorted into the ‘KNOWN’ pile. Any card that the student cannot answer within two seconds—or answers incorrectly —is sorted into the ‘UNKNOWN’ pile. ‘KNOWN’ Facts ‘UNKNOWN’ Fac 4 x 5 =__ 2 x 6 =__ 3 x 8 =__ 3 x 2 =__ 5 x 3 =__ 9 x 2 =__ 3 x 6 =__ 8 x 4 =__ 5 x 5 =__ 6 x 5 =__ 4 x 7 =__ 8 x 2 =__ 9 x 7 =__ 7 x 6 =__ 3 x 5 =__ www. interventioncentral. org 43

Response to Intervention Math Review: Incremental Rehearsal of ‘Math Facts’ Step 2: The tutor reviews the ‘math fact’ cards with the student. Any card that the student can answer within 2 seconds is sorted into the ‘KNOWN’ pile. Any card that the student cannot answer within two seconds—or answers incorrectly —is sorted into the ‘UNKNOWN’ pile. ‘KNOWN’ Facts ‘UNKNOWN’ Fac 4 x 5 =__ 2 x 6 =__ 3 x 8 =__ 3 x 2 =__ 5 x 3 =__ 9 x 2 =__ 3 x 6 =__ 8 x 4 =__ 5 x 5 =__ 6 x 5 =__ 4 x 7 =__ 8 x 2 =__ 9 x 7 =__ 7 x 6 =__ 3 x 5 =__ www. interventioncentral. org 43

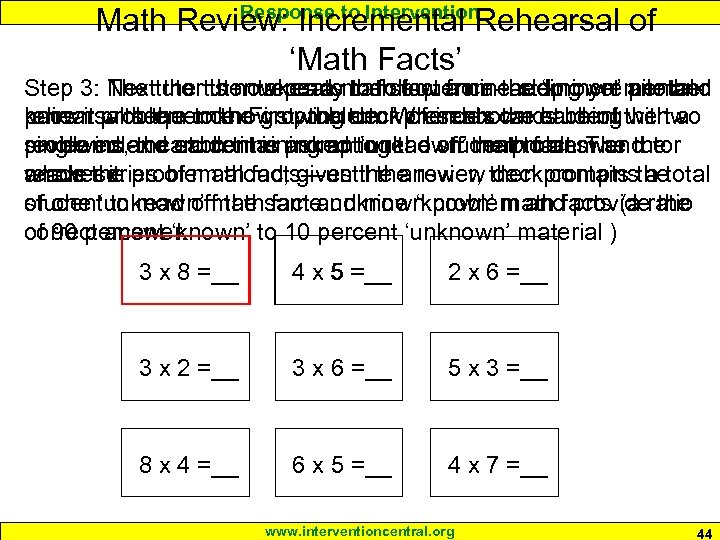

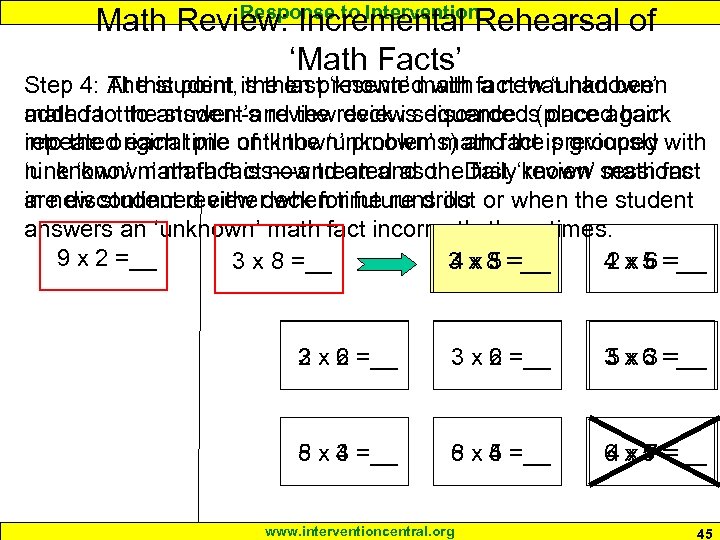

Response to Intervention Math Review: Incremental Rehearsal of ‘Math Facts’ Step 3: Nexttutor takes a math fact a nine-step incremental. The the is now ready the sequence--adding yet another then repeats to follow from the ‘known’ pile and pairs it problem unknown problem. When shown each of the two known with the to the growing deck of index the student rehearsal sequence: First, the tutor presents cards being with a problems, and each time prompting the off the problem and reviewed the student is asked ‘unknown’ math fact. The the single index card containing an to read student to answer tutor answer it. problem aloud, gives the answer, then prompts thetotal whole series of math facts—until the review deck contains a reads the of one ‘unknown’ math fact and nine ‘known’ math provide the student to read off the same unknown problem andfacts (a ratio of 90 percent ‘known’ to 10 percent ‘unknown’ material ) correct answer. 3 x 8 =__ 4 x 5 =__ 2 x 6 =__ 3 x 2 =__ 3 x 6 =__ 5 x 3 =__ 8 x 4 =__ 6 x 5 =__ 4 x 7 =__ www. interventioncentral. org 44

Response to Intervention Math Review: Incremental Rehearsal of ‘Math Facts’ Step 3: Nexttutor takes a math fact a nine-step incremental. The the is now ready the sequence--adding yet another then repeats to follow from the ‘known’ pile and pairs it problem unknown problem. When shown each of the two known with the to the growing deck of index the student rehearsal sequence: First, the tutor presents cards being with a problems, and each time prompting the off the problem and reviewed the student is asked ‘unknown’ math fact. The the single index card containing an to read student to answer tutor answer it. problem aloud, gives the answer, then prompts thetotal whole series of math facts—until the review deck contains a reads the of one ‘unknown’ math fact and nine ‘known’ math provide the student to read off the same unknown problem andfacts (a ratio of 90 percent ‘known’ to 10 percent ‘unknown’ material ) correct answer. 3 x 8 =__ 4 x 5 =__ 2 x 6 =__ 3 x 2 =__ 3 x 6 =__ 5 x 3 =__ 8 x 4 =__ 6 x 5 =__ 4 x 7 =__ www. interventioncentral. org 44

Response to Intervention Math Review: Incremental Rehearsal of ‘Math Facts’ At this point, the last ‘known’ math a new ‘unknown’ Step 4: The student is then presented with fact that had been added to to student’s review deck is discarded (placed back math fact theanswer--and the review sequence is once again into the original pile of ‘known’ problems) and the previously repeated each time until the ‘unknown’ math fact is grouped with ‘unknown’ math fact is now treated as the first review math fact nine ‘known’ math facts—and on. Daily‘known’ sessions in new student review deck for future drills. are discontinued either when time runs out or when the student answers an ‘unknown’ math fact incorrectly three times. 9 x 2 =__ 3 x 8 =__ 4 x 5 =__ 2 x 6 =__ 3 2 3 x 2 =__ 6 3 x 6 =__ 5 x 3 =__ 8 4 8 x 4 =__ 6 5 6 x 5 =__ 4 x 7 =__ www. interventioncentral. org 45

Response to Intervention Math Review: Incremental Rehearsal of ‘Math Facts’ At this point, the last ‘known’ math a new ‘unknown’ Step 4: The student is then presented with fact that had been added to to student’s review deck is discarded (placed back math fact theanswer--and the review sequence is once again into the original pile of ‘known’ problems) and the previously repeated each time until the ‘unknown’ math fact is grouped with ‘unknown’ math fact is now treated as the first review math fact nine ‘known’ math facts—and on. Daily‘known’ sessions in new student review deck for future drills. are discontinued either when time runs out or when the student answers an ‘unknown’ math fact incorrectly three times. 9 x 2 =__ 3 x 8 =__ 4 x 5 =__ 2 x 6 =__ 3 2 3 x 2 =__ 6 3 x 6 =__ 5 x 3 =__ 8 4 8 x 4 =__ 6 5 6 x 5 =__ 4 x 7 =__ www. interventioncentral. org 45

Response to Intervention Applied Math: Helping Students to Make Sense of ‘Story Problems’ Jim Wright www. interventioncentral. org

Response to Intervention Applied Math: Helping Students to Make Sense of ‘Story Problems’ Jim Wright www. interventioncentral. org

Response to Intervention ‘Advanced Math’ Quotes from Yogi Berra— • “Ninety percent of the game is half mental. " • “Pair up in threes. " • “You give 100 percent in the first half of the game, and if that isn't enough in the second half you give what's left. ” www. interventioncentral. org 47

Response to Intervention ‘Advanced Math’ Quotes from Yogi Berra— • “Ninety percent of the game is half mental. " • “Pair up in threes. " • “You give 100 percent in the first half of the game, and if that isn't enough in the second half you give what's left. ” www. interventioncentral. org 47

Response to Intervention Applied Math Problems: Rationale • Applied math problems (also known as ‘story’ or ‘word’ problems) are traditional tools for having students apply math concepts and operations to ‘real-world’ settings. www. interventioncentral. org 48

Response to Intervention Applied Math Problems: Rationale • Applied math problems (also known as ‘story’ or ‘word’ problems) are traditional tools for having students apply math concepts and operations to ‘real-world’ settings. www. interventioncentral. org 48

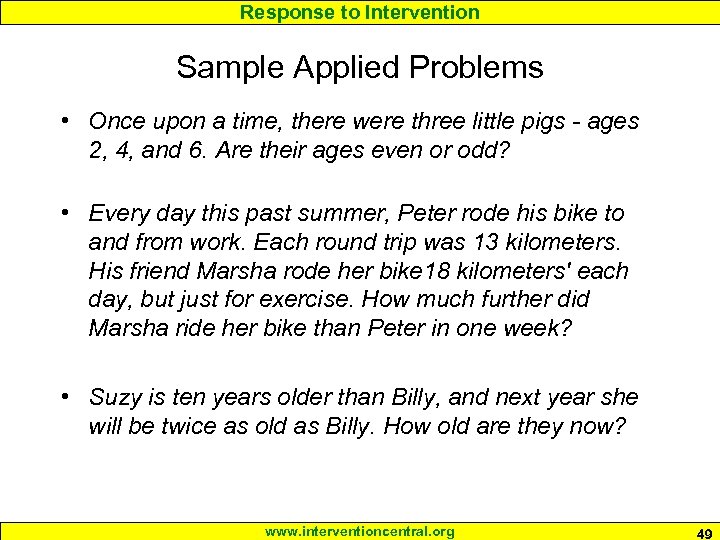

Response to Intervention Sample Applied Problems • Once upon a time, there were three little pigs - ages 2, 4, and 6. Are their ages even or odd? • Every day this past summer, Peter rode his bike to and from work. Each round trip was 13 kilometers. His friend Marsha rode her bike 18 kilometers' each day, but just for exercise. How much further did Marsha ride her bike than Peter in one week? • Suzy is ten years older than Billy, and next year she will be twice as old as Billy. How old are they now? www. interventioncentral. org 49

Response to Intervention Sample Applied Problems • Once upon a time, there were three little pigs - ages 2, 4, and 6. Are their ages even or odd? • Every day this past summer, Peter rode his bike to and from work. Each round trip was 13 kilometers. His friend Marsha rode her bike 18 kilometers' each day, but just for exercise. How much further did Marsha ride her bike than Peter in one week? • Suzy is ten years older than Billy, and next year she will be twice as old as Billy. How old are they now? www. interventioncentral. org 49

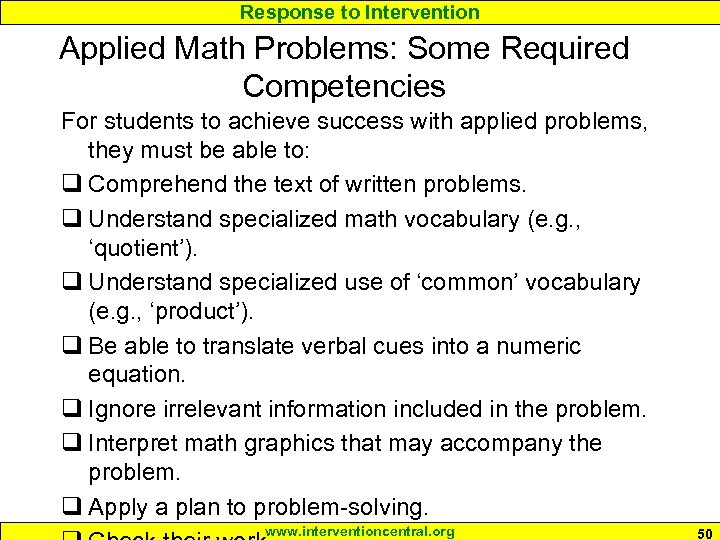

Response to Intervention Applied Math Problems: Some Required Competencies For students to achieve success with applied problems, they must be able to: q Comprehend the text of written problems. q Understand specialized math vocabulary (e. g. , ‘quotient’). q Understand specialized use of ‘common’ vocabulary (e. g. , ‘product’). q Be able to translate verbal cues into a numeric equation. q Ignore irrelevant information included in the problem. q Interpret math graphics that may accompany the problem. q Apply a plan to problem-solving. www. interventioncentral. org 50

Response to Intervention Applied Math Problems: Some Required Competencies For students to achieve success with applied problems, they must be able to: q Comprehend the text of written problems. q Understand specialized math vocabulary (e. g. , ‘quotient’). q Understand specialized use of ‘common’ vocabulary (e. g. , ‘product’). q Be able to translate verbal cues into a numeric equation. q Ignore irrelevant information included in the problem. q Interpret math graphics that may accompany the problem. q Apply a plan to problem-solving. www. interventioncentral. org 50

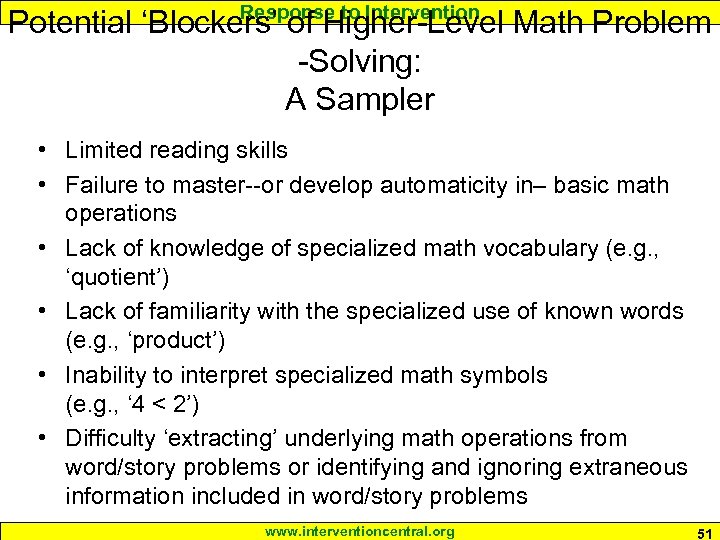

Response to Intervention Potential ‘Blockers’ of Higher-Level Math Problem -Solving: A Sampler • Limited reading skills • Failure to master--or develop automaticity in– basic math operations • Lack of knowledge of specialized math vocabulary (e. g. , ‘quotient’) • Lack of familiarity with the specialized use of known words (e. g. , ‘product’) • Inability to interpret specialized math symbols (e. g. , ‘ 4 < 2’) • Difficulty ‘extracting’ underlying math operations from word/story problems or identifying and ignoring extraneous information included in word/story problems www. interventioncentral. org 51

Response to Intervention Potential ‘Blockers’ of Higher-Level Math Problem -Solving: A Sampler • Limited reading skills • Failure to master--or develop automaticity in– basic math operations • Lack of knowledge of specialized math vocabulary (e. g. , ‘quotient’) • Lack of familiarity with the specialized use of known words (e. g. , ‘product’) • Inability to interpret specialized math symbols (e. g. , ‘ 4 < 2’) • Difficulty ‘extracting’ underlying math operations from word/story problems or identifying and ignoring extraneous information included in word/story problems www. interventioncentral. org 51

Response to Intervention Comprehending Math Vocabulary: The Barrier of Abstraction “…when it comes to abstract mathematical concepts, words describe activities or relationships that often lack a visual counterpart. Yet studies show that children grasp the idea of quantity, as well as other relational concepts, from a very early age…. As children develop their capacity for understanding, language, and its vocabulary, becomes a vital cognitive link between a child’s natural sense of number and order and conceptual learning. ” Source: Chard, D. (n. d. . Vocabulary strategies for the mathematics classroom. Retrieved November 23, -Chard, D. (n. d. ) 2007, from http: //www. eduplace. com/state/pdf/author/chard_hmm 05. pdf. www. interventioncentral. org 52

Response to Intervention Comprehending Math Vocabulary: The Barrier of Abstraction “…when it comes to abstract mathematical concepts, words describe activities or relationships that often lack a visual counterpart. Yet studies show that children grasp the idea of quantity, as well as other relational concepts, from a very early age…. As children develop their capacity for understanding, language, and its vocabulary, becomes a vital cognitive link between a child’s natural sense of number and order and conceptual learning. ” Source: Chard, D. (n. d. . Vocabulary strategies for the mathematics classroom. Retrieved November 23, -Chard, D. (n. d. ) 2007, from http: //www. eduplace. com/state/pdf/author/chard_hmm 05. pdf. www. interventioncentral. org 52

Response to Intervention Math Vocabulary: Classroom (Tier I) Recommendations • Preteach math vocabulary. Math vocabulary provides students with the language tools to grasp abstract mathematical concepts and to explain their own reasoning. Therefore, do not wait to teach that vocabulary only at ‘point of use’. Instead, preview relevant math vocabulary as a regular a part of the ‘background’ information that students receive in preparation to learn new math concepts or operations. • Model the relevant vocabulary when new concepts are taught. Strengthen students’ grasp of new vocabulary by reviewing a number of math problems with the class, each time consistently and explicitly modeling the use of appropriate vocabulary to describe the concepts being taught. Then have students engage in cooperative learning or individual practice activities in which they too must successfully use the new vocabulary—while the teacher provides targeted support to students as needed. • Source: Chard, D. (n. d. . students learn standard, widely accepted Ensure that Vocabulary strategies for the mathematics classroom. Retrieved November 23, 2007, from http: //www. eduplace. com/state/pdf/author/chard_hmm 05. pdf. labels for common www. interventioncentral. org math terms and operations and that 53

Response to Intervention Math Vocabulary: Classroom (Tier I) Recommendations • Preteach math vocabulary. Math vocabulary provides students with the language tools to grasp abstract mathematical concepts and to explain their own reasoning. Therefore, do not wait to teach that vocabulary only at ‘point of use’. Instead, preview relevant math vocabulary as a regular a part of the ‘background’ information that students receive in preparation to learn new math concepts or operations. • Model the relevant vocabulary when new concepts are taught. Strengthen students’ grasp of new vocabulary by reviewing a number of math problems with the class, each time consistently and explicitly modeling the use of appropriate vocabulary to describe the concepts being taught. Then have students engage in cooperative learning or individual practice activities in which they too must successfully use the new vocabulary—while the teacher provides targeted support to students as needed. • Source: Chard, D. (n. d. . students learn standard, widely accepted Ensure that Vocabulary strategies for the mathematics classroom. Retrieved November 23, 2007, from http: //www. eduplace. com/state/pdf/author/chard_hmm 05. pdf. labels for common www. interventioncentral. org math terms and operations and that 53

Response to Intervention Math Intervention: Tier I: High School: Peer Guided Pause • Students are trained to work in pairs. • At one or more appropriate review points in a math lecture, the instructor directs students to pair up to work together for 4 minutes. • During each Peer Guided Pause, students are given a worksheet that contains one or more correctly completed word or number problems illustrating the math concept(s) covered in the lecture. The sheet also contains several additional, similar problems that pairs of students work cooperatively to complete, along with an answer key. • Student pairs are reminded to (a) monitor their understanding of the lesson concepts; (b) review the correctly math model problem; (c) work cooperatively on the J. , & Brady, M. P. (1994). The effects of independent and peer guided practice during Source: Hawkins, additional problems, and (d) check their answers. The instructional pauses on the academic performance of students with mild handicaps. Education & teacher can direct student pairs to write their names on the Treatment of Children, 17 (1), 1 -28. www. interventioncentral. org 54

Response to Intervention Math Intervention: Tier I: High School: Peer Guided Pause • Students are trained to work in pairs. • At one or more appropriate review points in a math lecture, the instructor directs students to pair up to work together for 4 minutes. • During each Peer Guided Pause, students are given a worksheet that contains one or more correctly completed word or number problems illustrating the math concept(s) covered in the lecture. The sheet also contains several additional, similar problems that pairs of students work cooperatively to complete, along with an answer key. • Student pairs are reminded to (a) monitor their understanding of the lesson concepts; (b) review the correctly math model problem; (c) work cooperatively on the J. , & Brady, M. P. (1994). The effects of independent and peer guided practice during Source: Hawkins, additional problems, and (d) check their answers. The instructional pauses on the academic performance of students with mild handicaps. Education & teacher can direct student pairs to write their names on the Treatment of Children, 17 (1), 1 -28. www. interventioncentral. org 54

Response to Intervention Applied Problems: Encourage Students to ‘Draw’ the Problem Making a drawing of an applied, or ‘word’, problem is one easy heuristic tool that students can use to help them to find the solution and clarify misunderstandings. • The teacher hands out a worksheet containing at least six word problems. The teacher explains to students that making a picture of a word problem sometimes makes that problem clearer and easier to solve. • The teacher and students then independently create drawings of each of the problems on the worksheet. Next, the students show their drawings for each problem, explaining each drawing and how it relates to the word problem. The teacher also participates, explaining his or her drawings to the class or group. • Then students are directed independently to make drawings as an intermediate problem-solving step when they are faced with challenging word problems. NOTE: Source: Hawkins, J. , Skinner, C. H. , & Oliver, R. (2005). The effects of task demands when used in This strategy appears to be more effective and additive interspersallater, rather students’earlier, elementary Psychology Review, 34, 543 ratios on fifth-grade than mathematics accuracy. School grades. 555. . www. interventioncentral. org 55

Response to Intervention Applied Problems: Encourage Students to ‘Draw’ the Problem Making a drawing of an applied, or ‘word’, problem is one easy heuristic tool that students can use to help them to find the solution and clarify misunderstandings. • The teacher hands out a worksheet containing at least six word problems. The teacher explains to students that making a picture of a word problem sometimes makes that problem clearer and easier to solve. • The teacher and students then independently create drawings of each of the problems on the worksheet. Next, the students show their drawings for each problem, explaining each drawing and how it relates to the word problem. The teacher also participates, explaining his or her drawings to the class or group. • Then students are directed independently to make drawings as an intermediate problem-solving step when they are faced with challenging word problems. NOTE: Source: Hawkins, J. , Skinner, C. H. , & Oliver, R. (2005). The effects of task demands when used in This strategy appears to be more effective and additive interspersallater, rather students’earlier, elementary Psychology Review, 34, 543 ratios on fifth-grade than mathematics accuracy. School grades. 555. . www. interventioncentral. org 55

Response to Intervention Interpreting Math Graphics www. interventioncentral. org

Response to Intervention Interpreting Math Graphics www. interventioncentral. org

Response to Intervention Housing Bubble Graphic: New York Times 23 September 2007 Housing Price Index = 171 in 2005 Housing Price Index = 100 in 1987 www. interventioncentral. org 57

Response to Intervention Housing Bubble Graphic: New York Times 23 September 2007 Housing Price Index = 171 in 2005 Housing Price Index = 100 in 1987 www. interventioncentral. org 57

Response to Intervention Classroom Challenges in Interpreting Math Graphics When encountering math graphics, students may : • expect the answer to be easily accessible when in fact the graphic may expect the reader to interpret and draw conclusions • be inattentive to details of the graphic • treat irrelevant data as ‘relevant’ • not pay close attention to questions before turning to graphics to find the answer • fail to use their prior knowledge both the extend the information on the graphic and to act as a possible ‘check’ on the information that it Source: Mesmer, H. A. E. , & Hutchins, E. J. (2002). Using QARs with charts and graphs. The Reading Teacher, 56, 21– 27. www. interventioncentral. org presents. 58

Response to Intervention Classroom Challenges in Interpreting Math Graphics When encountering math graphics, students may : • expect the answer to be easily accessible when in fact the graphic may expect the reader to interpret and draw conclusions • be inattentive to details of the graphic • treat irrelevant data as ‘relevant’ • not pay close attention to questions before turning to graphics to find the answer • fail to use their prior knowledge both the extend the information on the graphic and to act as a possible ‘check’ on the information that it Source: Mesmer, H. A. E. , & Hutchins, E. J. (2002). Using QARs with charts and graphs. The Reading Teacher, 56, 21– 27. www. interventioncentral. org presents. 58

Response to Intervention Using Question-Answer Relationships (QARs) to Interpret Information from Math Graphics Students can be more savvy interpreters of graphics in applied math problems by applying the Question-Answer Relationship (QAR) strategy. Four Kinds of QAR Questions: • RIGHT THERE questions are fact-based and can be found in a single sentence, often accompanied by 'clue' words that also appear in the question. • THINK AND SEARCH questions can be answered by information in the text but require the scanning of text and making connections between different pieces of factual information. • AUTHOR AND YOU questions require that students take information or opinions that appear in the text and combine them with the reader's own experiences or opinions to formulate an answer. • ON MY OWN questions are based on the students' own experiences and do not require knowledge of the text to answer. Source: Mesmer, H. A. E. , & Hutchins, E. J. (2002). Using QARs with charts and graphs. The Reading Teacher, 56, 21– 27. www. interventioncentral. org 59

Response to Intervention Using Question-Answer Relationships (QARs) to Interpret Information from Math Graphics Students can be more savvy interpreters of graphics in applied math problems by applying the Question-Answer Relationship (QAR) strategy. Four Kinds of QAR Questions: • RIGHT THERE questions are fact-based and can be found in a single sentence, often accompanied by 'clue' words that also appear in the question. • THINK AND SEARCH questions can be answered by information in the text but require the scanning of text and making connections between different pieces of factual information. • AUTHOR AND YOU questions require that students take information or opinions that appear in the text and combine them with the reader's own experiences or opinions to formulate an answer. • ON MY OWN questions are based on the students' own experiences and do not require knowledge of the text to answer. Source: Mesmer, H. A. E. , & Hutchins, E. J. (2002). Using QARs with charts and graphs. The Reading Teacher, 56, 21– 27. www. interventioncentral. org 59

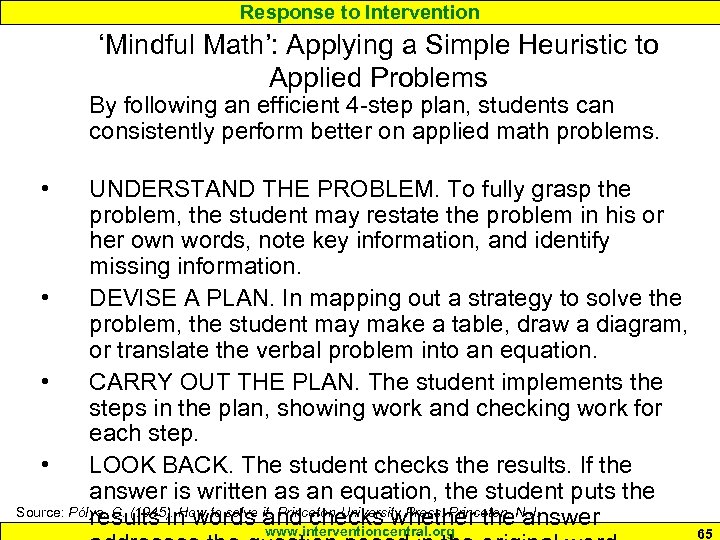

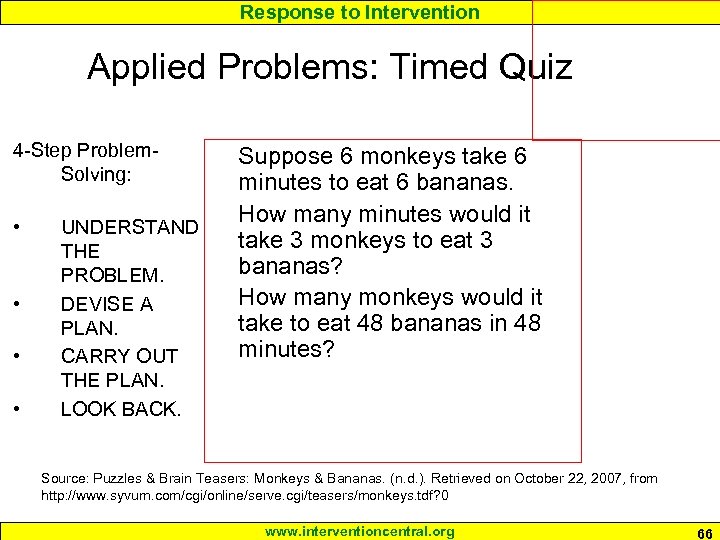

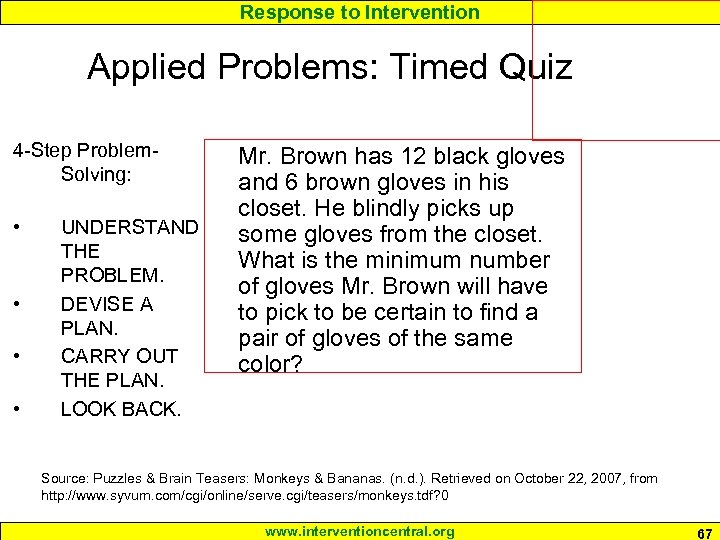

Response to Intervention Applied Problems: Individualized Self-Correction Checklists Students can improve their accuracy on particular types of word and number problems by using an ‘individualized self-instruction checklist’ that reminds them to pay attention to their own specific error patterns. • The teacher meets with the student. Together they analyze common error patterns that the student tends to commit on a particular problem type (e. g. , ‘On addition problems that require carrying, I don’t always remember to carry the number from the previously added column. ’). • For each type of error identified, the student and teacher together describe the appropriate step to take to prevent the error from occurring (e. g. , ‘When adding each column, make sure to carry numbers when needed. ’). • These self-check items are compiled into a single checklist. Students are then encouraged to use their individualized selfinstruction checklist whenever they Press: independently on their Source: Pólya, G. (1945). How to solve it. Princeton University work Princeton, N. J. www. interventioncentral. org number or word problems. 60