4e16ef872c67531ef47992b01d5e0f12.ppt

- Количество слайдов: 15

Resistance Is Futile! Physics 2113 Jonathan Dowling Physics 2113 Lecture 19: FRI 10 OCT Current & Resistance III Georg Simon Ohm (1789 -1854)

Resistance Is Futile! Physics 2113 Jonathan Dowling Physics 2113 Lecture 19: FRI 10 OCT Current & Resistance III Georg Simon Ohm (1789 -1854)

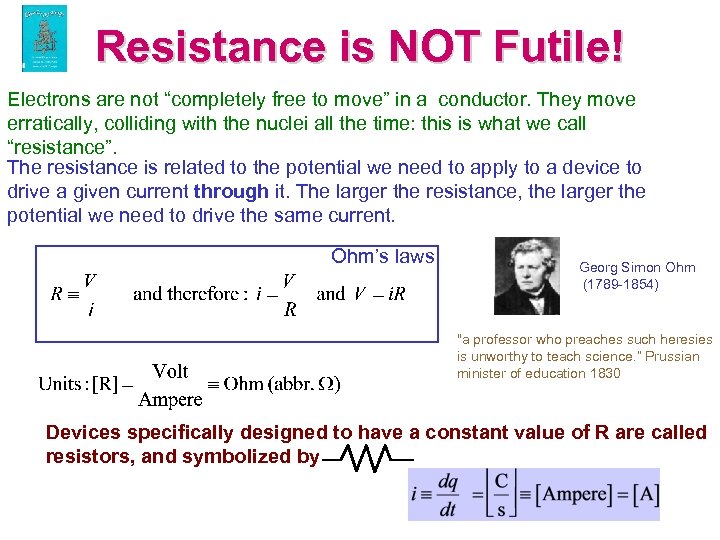

Resistance is NOT Futile! Electrons are not “completely free to move” in a conductor. They move erratically, colliding with the nuclei all the time: this is what we call “resistance”. The resistance is related to the potential we need to apply to a device to drive a given current through it. The larger the resistance, the larger the potential we need to drive the same current. Ohm’s laws Georg Simon Ohm (1789 -1854) "a professor who preaches such heresies is unworthy to teach science. ” Prussian minister of education 1830 Devices specifically designed to have a constant value of R are called resistors, and symbolized by

Resistance is NOT Futile! Electrons are not “completely free to move” in a conductor. They move erratically, colliding with the nuclei all the time: this is what we call “resistance”. The resistance is related to the potential we need to apply to a device to drive a given current through it. The larger the resistance, the larger the potential we need to drive the same current. Ohm’s laws Georg Simon Ohm (1789 -1854) "a professor who preaches such heresies is unworthy to teach science. ” Prussian minister of education 1830 Devices specifically designed to have a constant value of R are called resistors, and symbolized by

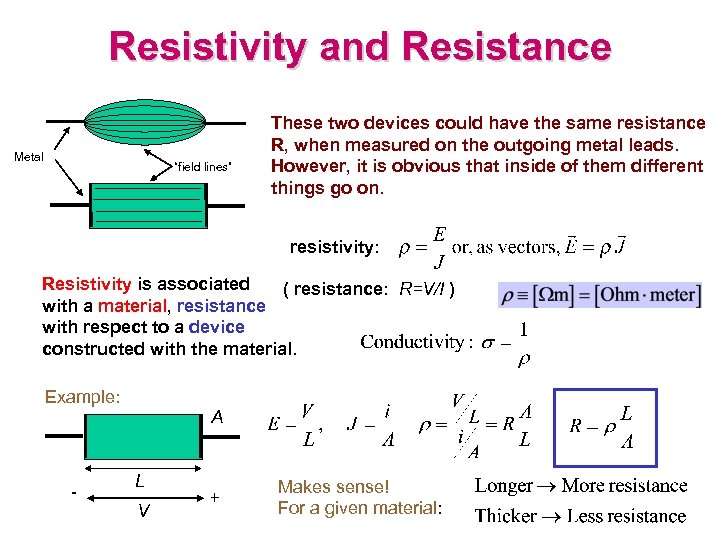

Resistivity and Resistance Metal “field lines” These two devices could have the same resistance R, when measured on the outgoing metal leads. However, it is obvious that inside of them different things go on. resistivity: Resistivity is associated ( resistance: R=V/I ) with a material, resistance with respect to a device constructed with the material. Example: A - L V + Makes sense! For a given material:

Resistivity and Resistance Metal “field lines” These two devices could have the same resistance R, when measured on the outgoing metal leads. However, it is obvious that inside of them different things go on. resistivity: Resistivity is associated ( resistance: R=V/I ) with a material, resistance with respect to a device constructed with the material. Example: A - L V + Makes sense! For a given material:

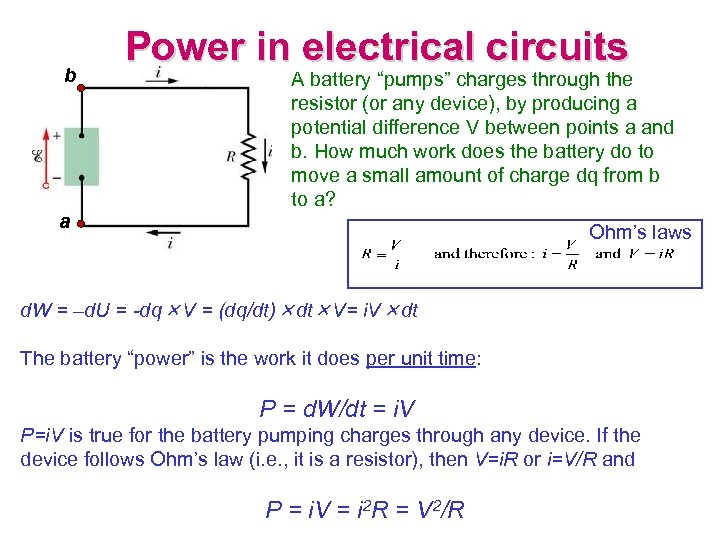

b a Power in electrical circuits A battery “pumps” charges through the resistor (or any device), by producing a potential difference V between points a and b. How much work does the battery do to move a small amount of charge dq from b to a? Ohm’s laws d. W = –d. U = -dq×V = (dq/dt)×dt×V= i. V×dt The battery “power” is the work it does per unit time: P = d. W/dt = i. V P=i. V is true for the battery pumping charges through any device. If the device follows Ohm’s law (i. e. , it is a resistor), then V=i. R or i=V/R and P = i. V = i 2 R = V 2/R

b a Power in electrical circuits A battery “pumps” charges through the resistor (or any device), by producing a potential difference V between points a and b. How much work does the battery do to move a small amount of charge dq from b to a? Ohm’s laws d. W = –d. U = -dq×V = (dq/dt)×dt×V= i. V×dt The battery “power” is the work it does per unit time: P = d. W/dt = i. V P=i. V is true for the battery pumping charges through any device. If the device follows Ohm’s law (i. e. , it is a resistor), then V=i. R or i=V/R and P = i. V = i 2 R = V 2/R

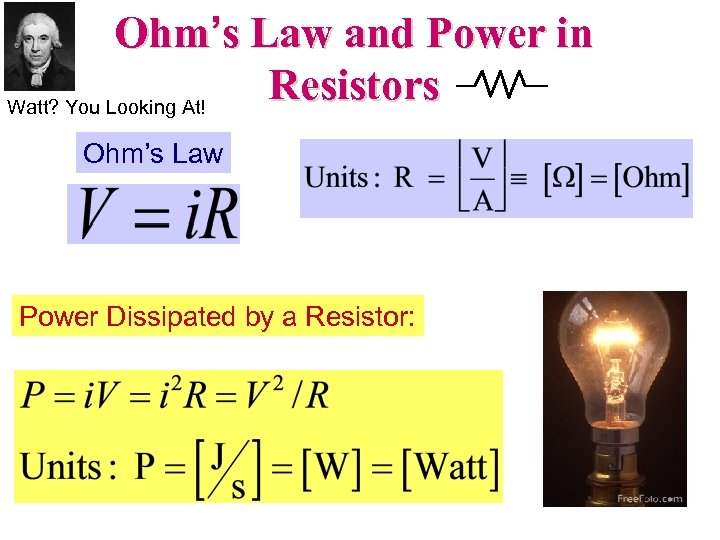

Ohm’s Law and Power in Resistors Watt? You Looking At! Ohm’s Law Power Dissipated by a Resistor:

Ohm’s Law and Power in Resistors Watt? You Looking At! Ohm’s Law Power Dissipated by a Resistor:

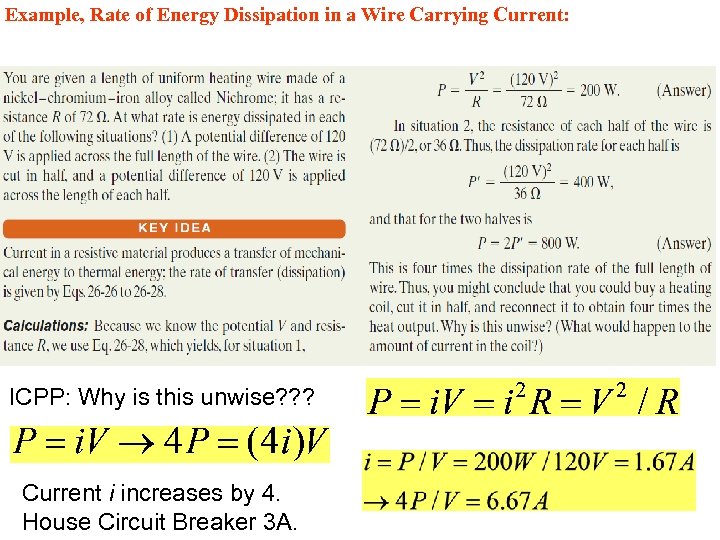

Example, Rate of Energy Dissipation in a Wire Carrying Current: ICPP: Why is this unwise? ? ? Current i increases by 4. House Circuit Breaker 3 A.

Example, Rate of Energy Dissipation in a Wire Carrying Current: ICPP: Why is this unwise? ? ? Current i increases by 4. House Circuit Breaker 3 A.

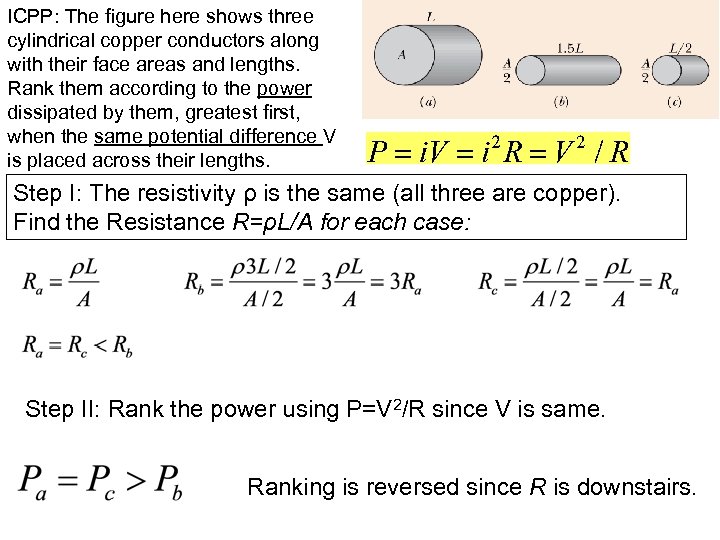

ICPP: The figure here shows three cylindrical copper conductors along with their face areas and lengths. Rank them according to the power dissipated by them, greatest first, when the same potential difference V is placed across their lengths. Step I: The resistivity ρ is the same (all three are copper). Find the Resistance R=ρL/A for each case: Step II: Rank the power using P=V 2/R since V is same. Ranking is reversed since R is downstairs.

ICPP: The figure here shows three cylindrical copper conductors along with their face areas and lengths. Rank them according to the power dissipated by them, greatest first, when the same potential difference V is placed across their lengths. Step I: The resistivity ρ is the same (all three are copper). Find the Resistance R=ρL/A for each case: Step II: Rank the power using P=V 2/R since V is same. Ranking is reversed since R is downstairs.

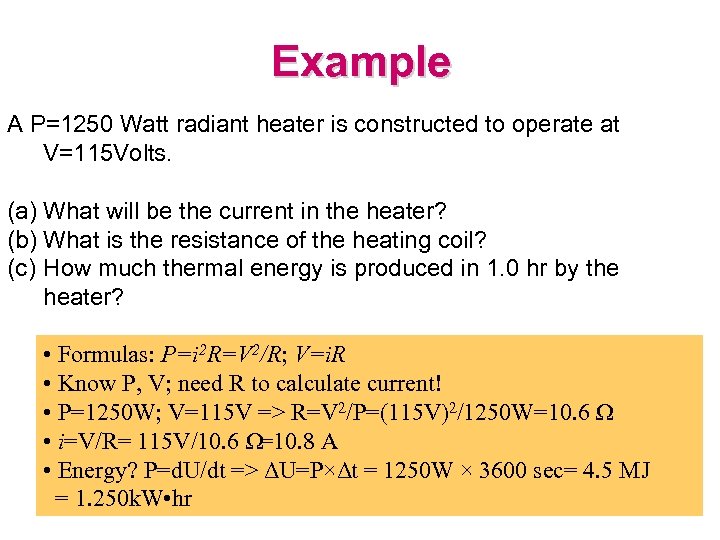

Example A P=1250 Watt radiant heater is constructed to operate at V=115 Volts. (a) What will be the current in the heater? (b) What is the resistance of the heating coil? (c) How much thermal energy is produced in 1. 0 hr by the heater? • Formulas: P=i 2 R=V 2/R; V=i. R • Know P, V; need R to calculate current! • P=1250 W; V=115 V => R=V 2/P=(115 V)2/1250 W=10. 6 Ω • i=V/R= 115 V/10. 6 Ω=10. 8 A • Energy? P=d. U/dt => ΔU=P×Δt = 1250 W × 3600 sec= 4. 5 MJ = 1. 250 k. W • hr

Example A P=1250 Watt radiant heater is constructed to operate at V=115 Volts. (a) What will be the current in the heater? (b) What is the resistance of the heating coil? (c) How much thermal energy is produced in 1. 0 hr by the heater? • Formulas: P=i 2 R=V 2/R; V=i. R • Know P, V; need R to calculate current! • P=1250 W; V=115 V => R=V 2/P=(115 V)2/1250 W=10. 6 Ω • i=V/R= 115 V/10. 6 Ω=10. 8 A • Energy? P=d. U/dt => ΔU=P×Δt = 1250 W × 3600 sec= 4. 5 MJ = 1. 250 k. W • hr

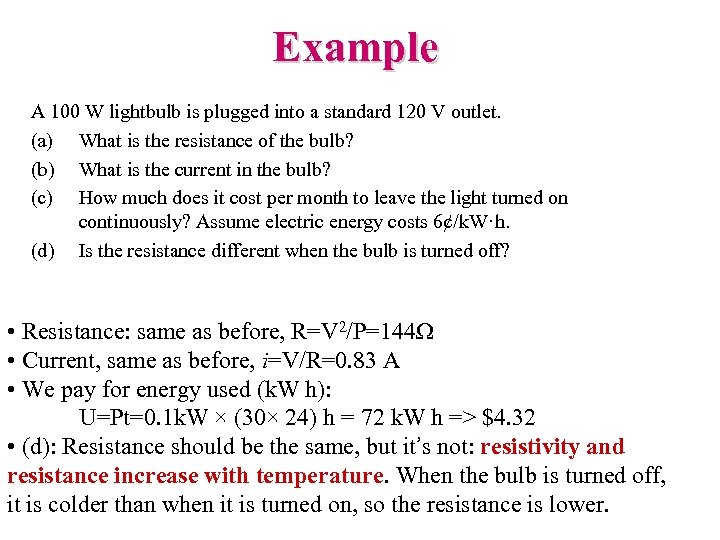

Example A 100 W lightbulb is plugged into a standard 120 V outlet. (a) What is the resistance of the bulb? (b) What is the current in the bulb? (c) How much does it cost per month to leave the light turned on continuously? Assume electric energy costs 6¢/k. W·h. (d) Is the resistance different when the bulb is turned off? • Resistance: same as before, R=V 2/P=144Ω • Current, same as before, i=V/R=0. 83 A • We pay for energy used (k. W h): U=Pt=0. 1 k. W × (30× 24) h = 72 k. W h => $4. 32 • (d): Resistance should be the same, but it’s not: resistivity and resistance increase with temperature. When the bulb is turned off, it is colder than when it is turned on, so the resistance is lower.

Example A 100 W lightbulb is plugged into a standard 120 V outlet. (a) What is the resistance of the bulb? (b) What is the current in the bulb? (c) How much does it cost per month to leave the light turned on continuously? Assume electric energy costs 6¢/k. W·h. (d) Is the resistance different when the bulb is turned off? • Resistance: same as before, R=V 2/P=144Ω • Current, same as before, i=V/R=0. 83 A • We pay for energy used (k. W h): U=Pt=0. 1 k. W × (30× 24) h = 72 k. W h => $4. 32 • (d): Resistance should be the same, but it’s not: resistivity and resistance increase with temperature. When the bulb is turned off, it is colder than when it is turned on, so the resistance is lower.

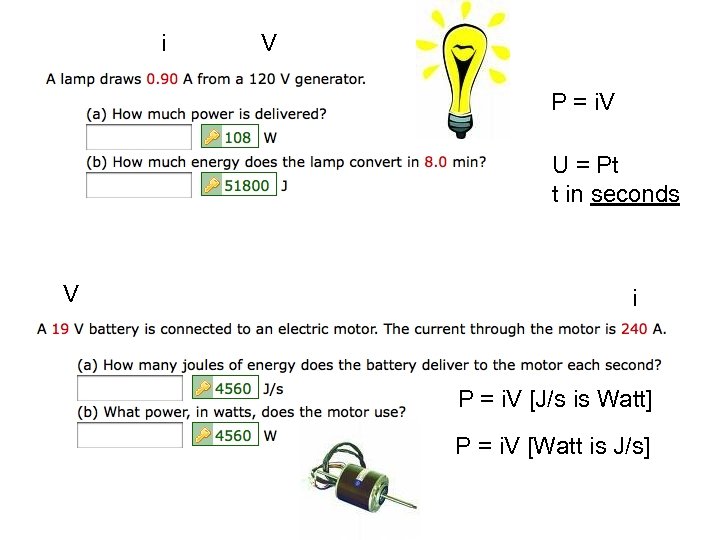

i V P = i. V U = Pt t in seconds V i P = i. V [J/s is Watt] P = i. V [Watt is J/s]

i V P = i. V U = Pt t in seconds V i P = i. V [J/s is Watt] P = i. V [Watt is J/s]

I’m switching to white light LEDs! Nobel Prize 2014! My House Has Two Front Porch Lights. Each Light Has a 100 W Incandescent Bulb. The Lights Come on at Dusk and Go Off at Dawn. How Much Does these lights Cost Me Per Year? Two 100 W Bulbs @ 12 Hours Each = One 100 W @ 24 Hours. P = 100 W = 0. 1 k. W T = 365 Days x 24 Hours/Day = 8670 Hours Demco Rate: D = 0. 1797$/(k. W×Hour) (From My Bill!) Cost = Px. Tx. D = (0. 1 k. W)x(8670 Hours)x(0. 1797$/k. W×Hour) = $157. 42

I’m switching to white light LEDs! Nobel Prize 2014! My House Has Two Front Porch Lights. Each Light Has a 100 W Incandescent Bulb. The Lights Come on at Dusk and Go Off at Dawn. How Much Does these lights Cost Me Per Year? Two 100 W Bulbs @ 12 Hours Each = One 100 W @ 24 Hours. P = 100 W = 0. 1 k. W T = 365 Days x 24 Hours/Day = 8670 Hours Demco Rate: D = 0. 1797$/(k. W×Hour) (From My Bill!) Cost = Px. Tx. D = (0. 1 k. W)x(8670 Hours)x(0. 1797$/k. W×Hour) = $157. 42

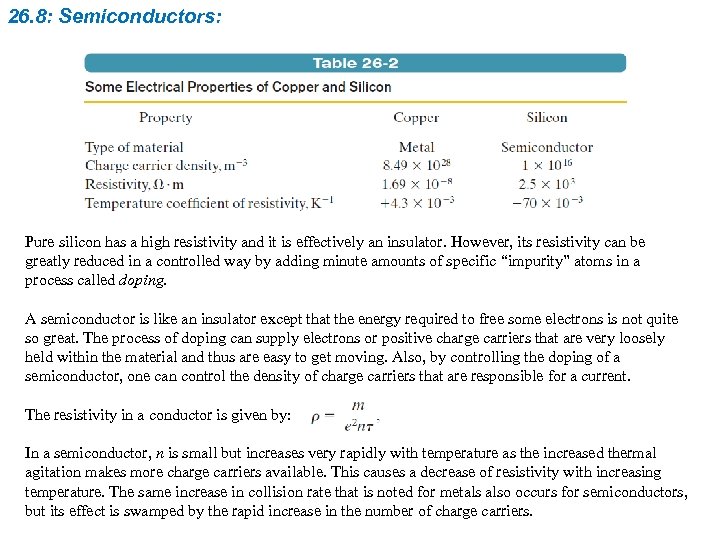

26. 8: Semiconductors: Pure silicon has a high resistivity and it is effectively an insulator. However, its resistivity can be greatly reduced in a controlled way by adding minute amounts of specific “impurity” atoms in a process called doping. A semiconductor is like an insulator except that the energy required to free some electrons is not quite so great. The process of doping can supply electrons or positive charge carriers that are very loosely held within the material and thus are easy to get moving. Also, by controlling the doping of a semiconductor, one can control the density of charge carriers that are responsible for a current. The resistivity in a conductor is given by: In a semiconductor, n is small but increases very rapidly with temperature as the increased thermal agitation makes more charge carriers available. This causes a decrease of resistivity with increasing temperature. The same increase in collision rate that is noted for metals also occurs for semiconductors, but its effect is swamped by the rapid increase in the number of charge carriers.

26. 8: Semiconductors: Pure silicon has a high resistivity and it is effectively an insulator. However, its resistivity can be greatly reduced in a controlled way by adding minute amounts of specific “impurity” atoms in a process called doping. A semiconductor is like an insulator except that the energy required to free some electrons is not quite so great. The process of doping can supply electrons or positive charge carriers that are very loosely held within the material and thus are easy to get moving. Also, by controlling the doping of a semiconductor, one can control the density of charge carriers that are responsible for a current. The resistivity in a conductor is given by: In a semiconductor, n is small but increases very rapidly with temperature as the increased thermal agitation makes more charge carriers available. This causes a decrease of resistivity with increasing temperature. The same increase in collision rate that is noted for metals also occurs for semiconductors, but its effect is swamped by the rapid increase in the number of charge carriers.

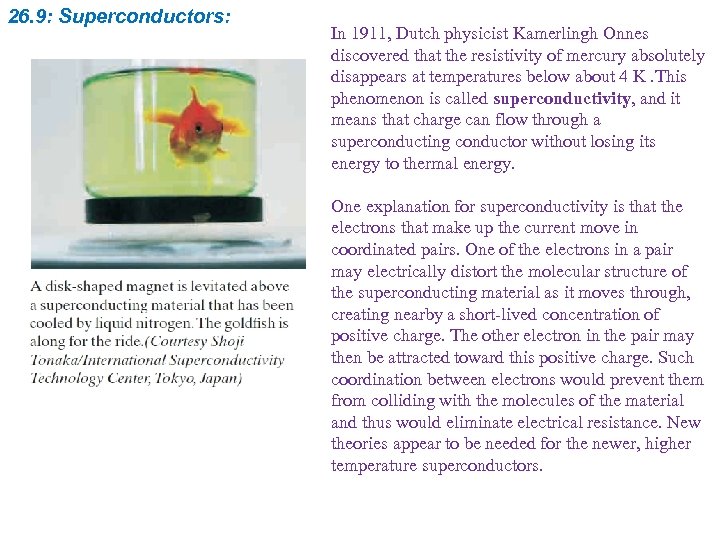

26. 9: Superconductors: In 1911, Dutch physicist Kamerlingh Onnes discovered that the resistivity of mercury absolutely disappears at temperatures below about 4 K. This phenomenon is called superconductivity, and it means that charge can flow through a superconducting conductor without losing its energy to thermal energy. One explanation for superconductivity is that the electrons that make up the current move in coordinated pairs. One of the electrons in a pair may electrically distort the molecular structure of the superconducting material as it moves through, creating nearby a short-lived concentration of positive charge. The other electron in the pair may then be attracted toward this positive charge. Such coordination between electrons would prevent them from colliding with the molecules of the material and thus would eliminate electrical resistance. New theories appear to be needed for the newer, higher temperature superconductors.

26. 9: Superconductors: In 1911, Dutch physicist Kamerlingh Onnes discovered that the resistivity of mercury absolutely disappears at temperatures below about 4 K. This phenomenon is called superconductivity, and it means that charge can flow through a superconducting conductor without losing its energy to thermal energy. One explanation for superconductivity is that the electrons that make up the current move in coordinated pairs. One of the electrons in a pair may electrically distort the molecular structure of the superconducting material as it moves through, creating nearby a short-lived concentration of positive charge. The other electron in the pair may then be attracted toward this positive charge. Such coordination between electrons would prevent them from colliding with the molecules of the material and thus would eliminate electrical resistance. New theories appear to be needed for the newer, higher temperature superconductors.