a309fad771dce41940de35640e93bc97.ppt

- Количество слайдов: 29

Reducing medical error and increasing patient safety Richard Smith Editor, BMJ

Reducing medical error and increasing patient safety Richard Smith Editor, BMJ

What I want to talk about • • • A story How common is error? Why does error happen? How should we think of error? How should we respond?

What I want to talk about • • • A story How common is error? Why does error happen? How should we think of error? How should we respond?

A story

A story

How common is error? • Harvard Medical Practice Study • Reviewed medical charts of 30 121 patients admitted to 51 acute care hospitals in New York state in 1984 • In 3. 7% an adverse event led to prolonged admission or produced disability at the time of discharge • 69% of injuries were caused by errors

How common is error? • Harvard Medical Practice Study • Reviewed medical charts of 30 121 patients admitted to 51 acute care hospitals in New York state in 1984 • In 3. 7% an adverse event led to prolonged admission or produced disability at the time of discharge • 69% of injuries were caused by errors

How common is medical error? • Australian study • Investigators reviewed the medical records of 14 179 admissions to 28 hospitals in New South Wales and South Australia in 1995. • An adverse event occurred in 16. 6% of admissions, resulting in permanent disability in 13. 7% of patients and death in 4. 9% • 51% of adverse events were considered to have been preventable.

How common is medical error? • Australian study • Investigators reviewed the medical records of 14 179 admissions to 28 hospitals in New South Wales and South Australia in 1995. • An adverse event occurred in 16. 6% of admissions, resulting in permanent disability in 13. 7% of patients and death in 4. 9% • 51% of adverse events were considered to have been preventable.

How common is medical error? • The differences between the US and Australian results may reflect different methods or different rates • Other, smaller studies (including one from Britain) show similar orders of errors • There are few studies from outpatients or primary care

How common is medical error? • The differences between the US and Australian results may reflect different methods or different rates • Other, smaller studies (including one from Britain) show similar orders of errors • There are few studies from outpatients or primary care

How common is medical error? • An evaluation of complications associated with medications among patients at 11 primary care sites in Boston. • Of 2258 patients who had drugs prescribed, 18% reported having had a drug related complication, such as gastrointestinal symptoms, sleep disturbance, or fatigue in the previous year.

How common is medical error? • An evaluation of complications associated with medications among patients at 11 primary care sites in Boston. • Of 2258 patients who had drugs prescribed, 18% reported having had a drug related complication, such as gastrointestinal symptoms, sleep disturbance, or fatigue in the previous year.

Results of medical error • In Australia medical error results in as many as 18 000 unnecessary deaths, and more than 50 000 patients become disabled each year. • In the United States medical error results in at least 44 000 (and perhaps as many as 98 000) unnecessary deaths each year and 1 000 excess injuries.

Results of medical error • In Australia medical error results in as many as 18 000 unnecessary deaths, and more than 50 000 patients become disabled each year. • In the United States medical error results in at least 44 000 (and perhaps as many as 98 000) unnecessary deaths each year and 1 000 excess injuries.

Types of error • About half of the adverse events occurring among inpatients resulted from surgery. • Next come – Complications from drug treatment – therapeutic mishaps – diagnostic errors were the most common non-operative events. In the Australian study cognitive errors, such as making an

Types of error • About half of the adverse events occurring among inpatients resulted from surgery. • Next come – Complications from drug treatment – therapeutic mishaps – diagnostic errors were the most common non-operative events. In the Australian study cognitive errors, such as making an

Types of error • Cognitive errors--such as incorrect diagnosis or choosing the wrong medication-- more likely to have been preventable and more likely to result in permanent disability than technical errors.

Types of error • Cognitive errors--such as incorrect diagnosis or choosing the wrong medication-- more likely to have been preventable and more likely to result in permanent disability than technical errors.

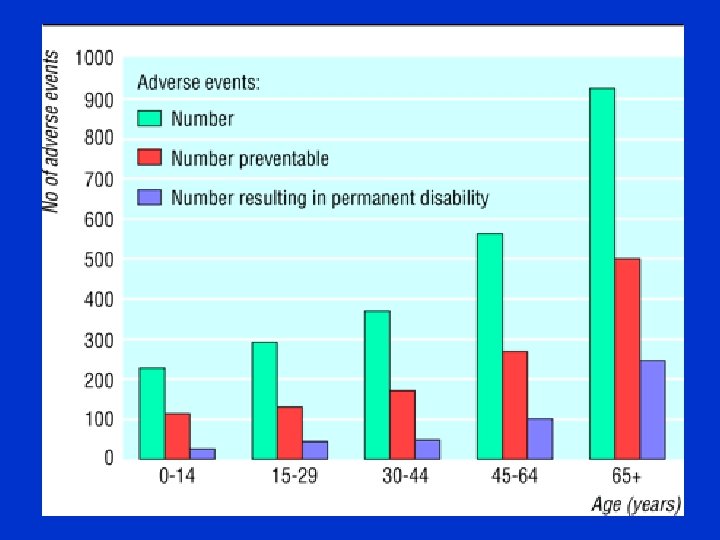

Which patients are most at risk? • Those undergoing cardiothoracic surgery, vascular surgery, or neurosurgery • Those with complex conditions • Those in the emergency room • Those looked after by inexperienced doctors • Older patients

Which patients are most at risk? • Those undergoing cardiothoracic surgery, vascular surgery, or neurosurgery • Those with complex conditions • Those in the emergency room • Those looked after by inexperienced doctors • Older patients

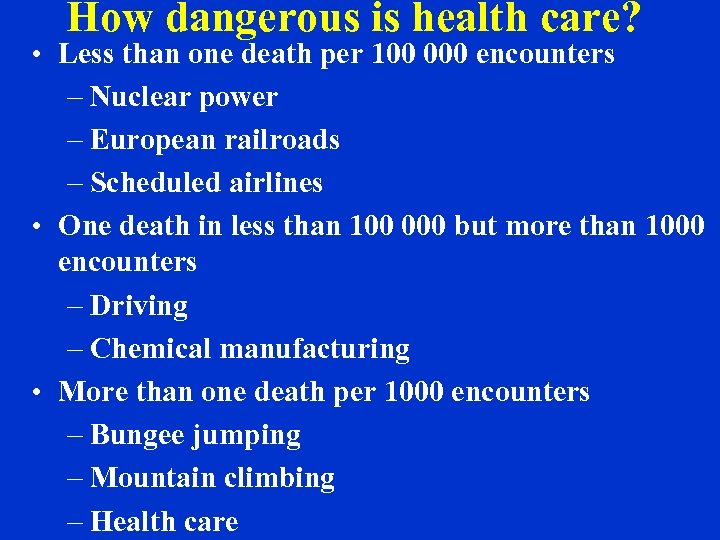

How dangerous is health care? • Less than one death per 100 000 encounters – Nuclear power – European railroads – Scheduled airlines • One death in less than 100 000 but more than 1000 encounters – Driving – Chemical manufacturing • More than one death per 1000 encounters – Bungee jumping – Mountain climbing – Health care

How dangerous is health care? • Less than one death per 100 000 encounters – Nuclear power – European railroads – Scheduled airlines • One death in less than 100 000 but more than 1000 encounters – Driving – Chemical manufacturing • More than one death per 1000 encounters – Bungee jumping – Mountain climbing – Health care

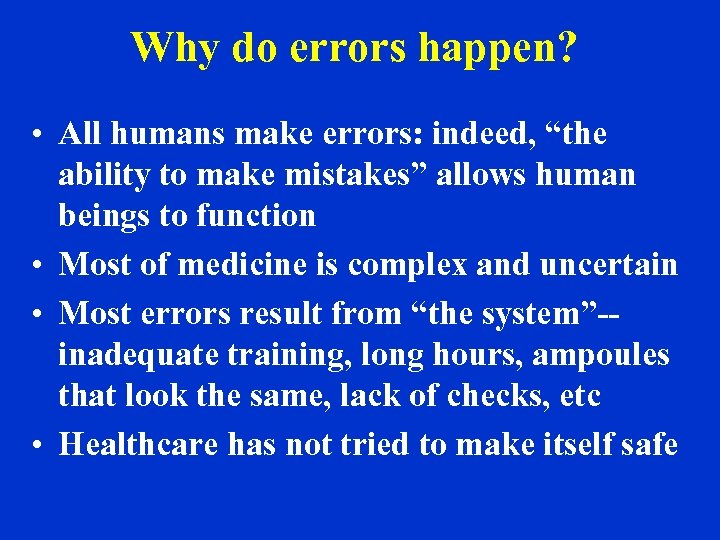

Why do errors happen? • All humans make errors: indeed, “the ability to make mistakes” allows human beings to function • Most of medicine is complex and uncertain • Most errors result from “the system”-inadequate training, long hours, ampoules that look the same, lack of checks, etc • Healthcare has not tried to make itself safe

Why do errors happen? • All humans make errors: indeed, “the ability to make mistakes” allows human beings to function • Most of medicine is complex and uncertain • Most errors result from “the system”-inadequate training, long hours, ampoules that look the same, lack of checks, etc • Healthcare has not tried to make itself safe

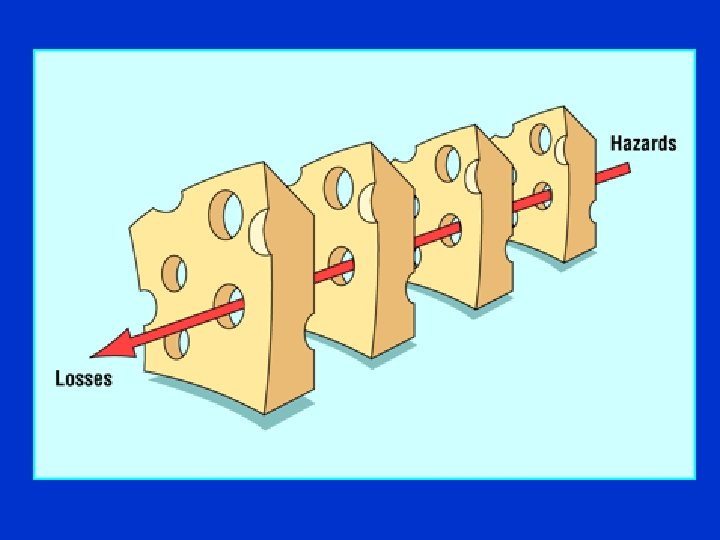

How to think of error? • An individual failing – Only the minority of cases amount from negligence or misconduct; so it’s the “wrong” diagnosis – It will not solve the problem--it will probably in fact make it worse because it fails to address the problem – Doctors will hide errors – May destroy many doctors inadvertently (the second victim)

How to think of error? • An individual failing – Only the minority of cases amount from negligence or misconduct; so it’s the “wrong” diagnosis – It will not solve the problem--it will probably in fact make it worse because it fails to address the problem – Doctors will hide errors – May destroy many doctors inadvertently (the second victim)

How to think of error? • A systems failure – This is the starting point for redesigning the system and reducing error

How to think of error? • A systems failure – This is the starting point for redesigning the system and reducing error

How to respond? Tactics • Reduce complexity • Optimise information processing – checklists, reminders, protocols • Automate wisely • Use constraints – for instance, with needle connections • Mitigate the unwanted side effects of change – with training, for example.

How to respond? Tactics • Reduce complexity • Optimise information processing – checklists, reminders, protocols • Automate wisely • Use constraints – for instance, with needle connections • Mitigate the unwanted side effects of change – with training, for example.

Building a safe healthcare system (from James Reason) • • Principles Policies Procedures Practices

Building a safe healthcare system (from James Reason) • • Principles Policies Procedures Practices

Building a safe healthcare system (from James Reason) • Principles – Safety is everybody’s business – Top management accepts setbacks and anticipates errors – safety issues are considered regularly at the highest level – Past events are reviewed and changes implemented

Building a safe healthcare system (from James Reason) • Principles – Safety is everybody’s business – Top management accepts setbacks and anticipates errors – safety issues are considered regularly at the highest level – Past events are reviewed and changes implemented

Building a safe healthcare system (from James Reason) • Principles – After a mishap management concentrates on fixing the system not blaming the individual – Understand that effective risk management depends on the collection, analysis, and dissemination of data – Top management is proactive in improving safety--seeks out error traps, eliminates error producing factors, brainstorms new scenarios of failure

Building a safe healthcare system (from James Reason) • Principles – After a mishap management concentrates on fixing the system not blaming the individual – Understand that effective risk management depends on the collection, analysis, and dissemination of data – Top management is proactive in improving safety--seeks out error traps, eliminates error producing factors, brainstorms new scenarios of failure

Building a safe healthcare system (from James Reason) • Policies – Safety related information has direct access to the top – Risk management is not an oubliette – Meetings on safety are attended by staff from many levels and departments – Messengers are rewarded not shot – Top managers create a reporting culture and a just culture

Building a safe healthcare system (from James Reason) • Policies – Safety related information has direct access to the top – Risk management is not an oubliette – Meetings on safety are attended by staff from many levels and departments – Messengers are rewarded not shot – Top managers create a reporting culture and a just culture

Building a safe healthcare system (from James Reason) • Policies – Reporting includes qualified indemnity, confidentiality, separation of data collection from disciplinary procedures – Disciplinary systems agree the difference between acceptable and unacceptable behaviour and involve peers

Building a safe healthcare system (from James Reason) • Policies – Reporting includes qualified indemnity, confidentiality, separation of data collection from disciplinary procedures – Disciplinary systems agree the difference between acceptable and unacceptable behaviour and involve peers

Building a safe healthcare system (from James Reason) • Procedures – Training in the recognition and recovery of errors – Feedback on recurrent error patterns – An awareness that procedures cannot cover all circumstances; on the spot training – Protocols written with those doing the job – Procedures must be intelligible, workable, available

Building a safe healthcare system (from James Reason) • Procedures – Training in the recognition and recovery of errors – Feedback on recurrent error patterns – An awareness that procedures cannot cover all circumstances; on the spot training – Protocols written with those doing the job – Procedures must be intelligible, workable, available

Building a safe healthcare system (from James Reason) • Procedures – Clinical supervisors train their charges in the mental as well as the technical skills necessary for safe and effective performance

Building a safe healthcare system (from James Reason) • Procedures – Clinical supervisors train their charges in the mental as well as the technical skills necessary for safe and effective performance

Building a safe healthcare system (from James Reason) • Practices – Rapid, useful, and intelligible feedback on lessons learnt and actions needed – Bottom up information listened to and acted on – And when mishaps occur • Acknowledge responsibility • Apologise • Convince patients and victims that lessons learned will reduce chance of recurrence

Building a safe healthcare system (from James Reason) • Practices – Rapid, useful, and intelligible feedback on lessons learnt and actions needed – Bottom up information listened to and acted on – And when mishaps occur • Acknowledge responsibility • Apologise • Convince patients and victims that lessons learned will reduce chance of recurrence

James Reason’s bottom line • Fallibility is part of the human condition • We can’t change the human condition • We can change the conditions under which people work

James Reason’s bottom line • Fallibility is part of the human condition • We can’t change the human condition • We can change the conditions under which people work

Conclusions • Human beings will always make errors • Errors are common in medicine, killing tens of thousands • We begin to know something about the epidemiology of error, but we need to know much more • Naming, blaming and shaming have no remedial value

Conclusions • Human beings will always make errors • Errors are common in medicine, killing tens of thousands • We begin to know something about the epidemiology of error, but we need to know much more • Naming, blaming and shaming have no remedial value

Conclusions • We need to design health care systems that put safety first (First, do no harm) • We know a lot about how to do that • It’s a long, never ending job

Conclusions • We need to design health care systems that put safety first (First, do no harm) • We know a lot about how to do that • It’s a long, never ending job