247f2ef74186b43c568c0097039266b0.ppt

- Количество слайдов: 41

Recursive Views and Global Views Zachary G. Ives University of Pennsylvania CIS 550 – Database & Information Systems November 9, 2004 Some slide content courtesy of Susan Davidson, Dan Suciu, & Raghu Ramakrishnan

Where We Are… § We’ve seen how views are useful both within a data model, and as a way of going from one model to another § You read the Shanmugasundaram paper on relational XML conversion § There have been many follow-up pieces of work § There have been attempts to build “native XML” databases instead § Now we’re going to talk about another important way views can be used to fix a limitation of the XML relational mappings § We’ll also talk about how certain classes of views can be manipulated and reasoned about in interesting ways § Then we’ll consider the use of viewsintegratingdata in 2

An Important Set of Questions § Views are incredibly powerful formalisms for describing how data relates: fn: rel … rel § Can I define a view recursively ? § Why might this be useful in the XML construction case? When should the recursion stop? § Suppose we have two views, and v 2 1 v § How do I know whether they represent the same data? § If v 1 is materialized, can we use it to compute? v 2 This is fundamental to query optimization and data integration, as we’ll see later 3

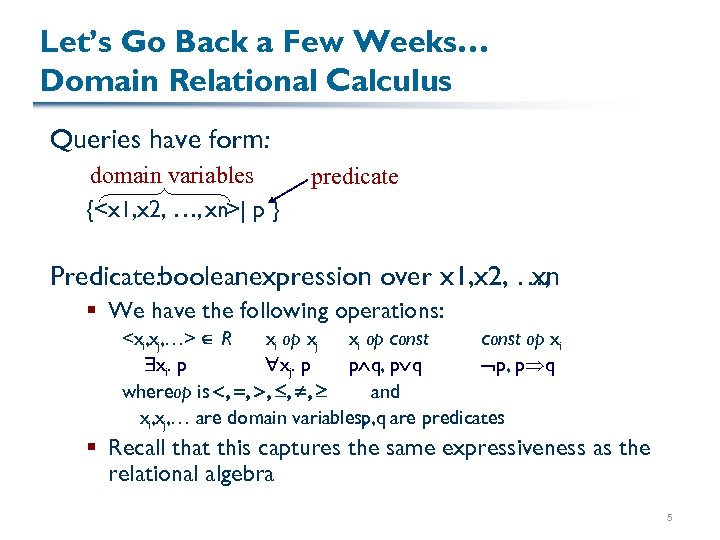

Reasoning about Queries and Views § SQL or. XQueryare a bit too complex to reason about directly § Some aspects of it make reasoning about SQL queries undecidable § We need an elegant way of describing views (let’s assume a relational model for now) § Should bedeclarative § Should beless complexthan SQL § Doesn’t need to support all of SQL – aggregation, for instance, may be more than we need 4

Let’s Go Back a Few Weeks… Domain Relational Calculus Queries have form: domain variables {<x 1, x 2, …, xn>| p } predicate Predicate: booleanexpression over x 1, x 2, …, xn § We have the following operations: <xi, xj, …> R xi op xj xi op const op xi xi. p xj. p p q, p q p, p q whereop is , , , and xi, xj, … are domain variables; are predicates p, q § Recall that this captures the same expressiveness as the relational algebra 5

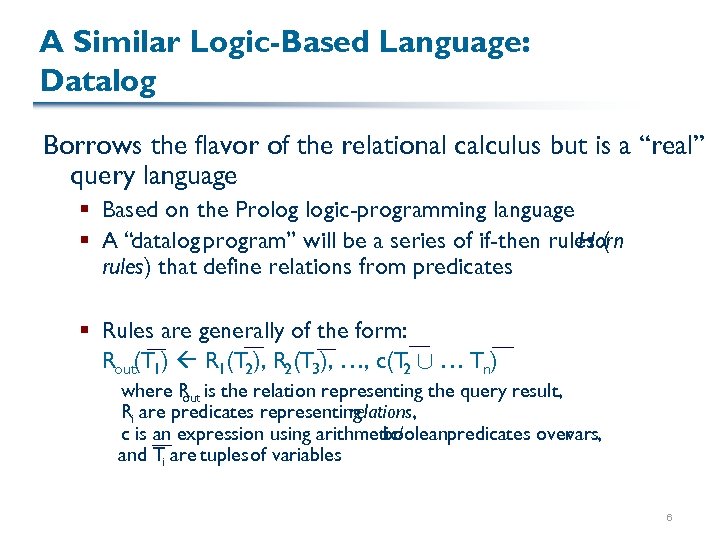

A Similar Logic-Based Language: Datalog Borrows the flavor of the relational calculus but is a “real” query language § Based on the Prolog logic-programming language § A “datalog program” will be a series of if-then rules ( Horn rules) that define relations from predicates § Rules are generally of the form: Rout(T 1) R 1(T 2), R 2(T 3), …, c(T [ … Tn) 2 where R is the relation representing the query result, out Ri are predicates representing relations, c is an expression using arithmetic/ booleanpredicates over vars, and Ti are tuples of variables 6

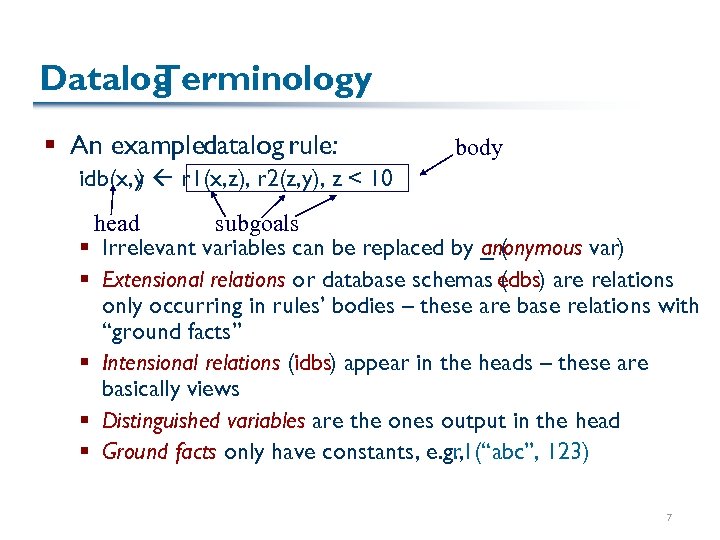

Datalog Terminology § An exampledatalog rule: body idb(x, y r 1(x, z), r 2(z, y), z < 10 ) head subgoals § Irrelevant variables can be replaced by _ ( anonymous var) § Extensional relations or database schemas edbs) are relations ( only occurring in rules’ bodies – these are base relations with “ground facts” § Intensional relations (idbs) appear in the heads – these are basically views § Distinguished variables are the ones output in the head § Ground facts only have constants, e. g. , r 1(“abc”, 123) 7

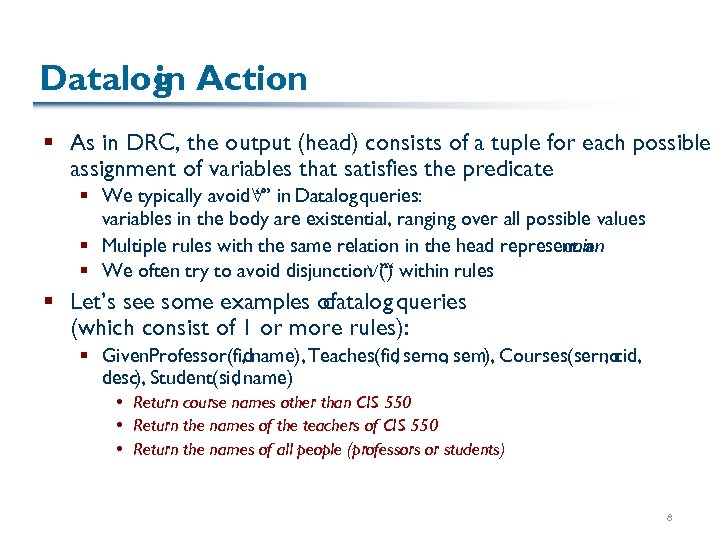

Datalog Action in § As in DRC, the output (head) consists of a tuple for each possible assignment of variables that satisfies the predicate § We typically avoid 8” in Datalog queries: “ variables in the body are existential, ranging over all possible values § Multiple rules with the same relation in the head represent a union § We often try to avoid disjunction (“ within rules Ç”) § Let’s see some examples of datalog queries (which consist of 1 or more rules): § Given. Professor(fidname), Teaches(fid serno sem), Courses(serno , , cid, desc), Student(sid name) , Return course names other than CIS 550 Return the names of the teachers of CIS 550 Return the names of all people (professors or students) 8

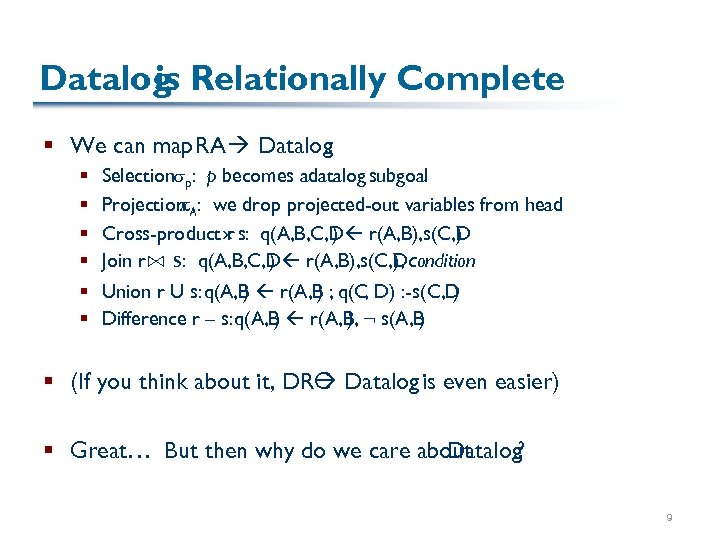

Datalog Relationally Complete is § We can map RA Datalog: § § Selection p: p becomes adatalog subgoal Projection A: we drop projected-out variables from head Cross-product s: q(A, B, C, D r(A, B), s(C, D r ) ) Join r⋈ s: q(A, B, C, D r(A, B), s(C, D condition ) ), § Union r U s: q(A, B r(A, B ; q(C D) : - s(C, D ) ) , ) § Difference r – s: q(A, B r(A, B : s(A, B ) ), ) § (If you think about it, DRC Datalog is even easier) § Great… But then why do we care about Datalog? 9

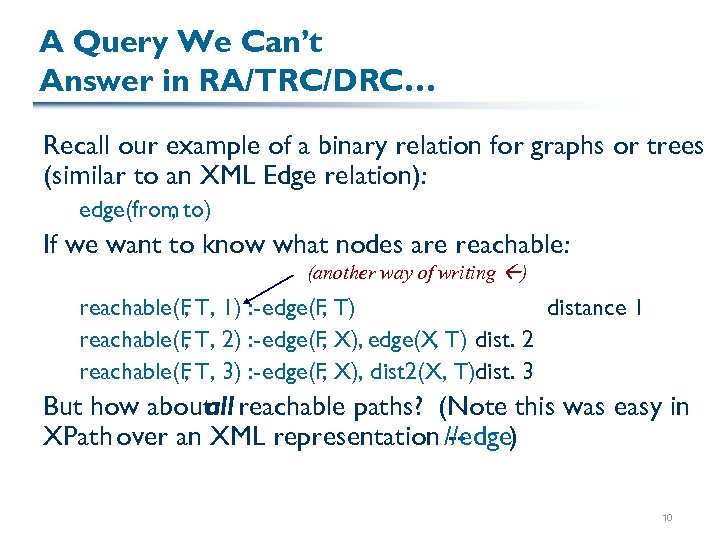

A Query We Can’t Answer in RA/TRC/DRC… Recall our example of a binary relation for graphs or trees (similar to an XML Edge relation): edge(from to) , If we want to know what nodes are reachable: (another way of writing ) reachable(F T, 1) : - edge(F T) , , distance 1 reachable(F T, 2) : - edge(F X), edge(X, T) dist. 2 , , reachable(F T, 3) : - edge(F X), dist 2(X, T)dist. 3 , , But how about reachable paths? (Note this was easy in all XPath over an XML representation //edge) -10

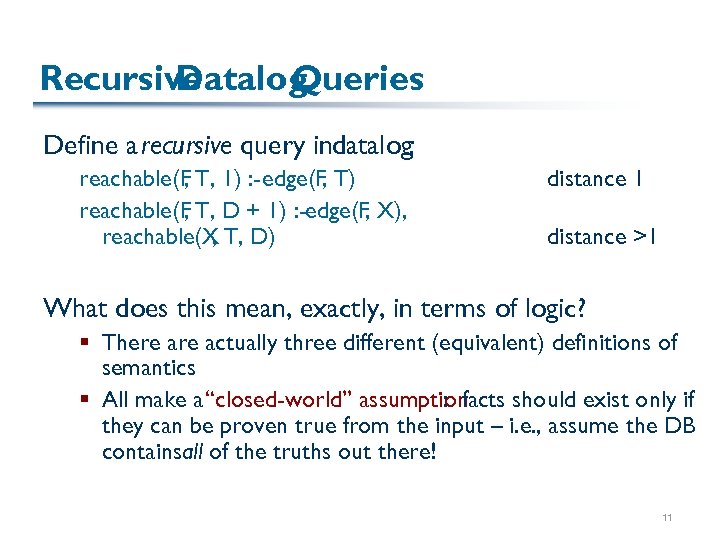

Recursive Datalog Queries Define a recursive query indatalog: reachable(F T, 1) : - edge(F T) , , reachable(F T, D + 1) : -edge(F X), , , reachable(X T, D) , distance 1 distance >1 What does this mean, exactly, in terms of logic? § There actually three different (equivalent) definitions of semantics § All make a “closed-world” assumption : facts should exist only if they can be proven true from the input – i. e. , assume the DB containsall of the truths out there! 11

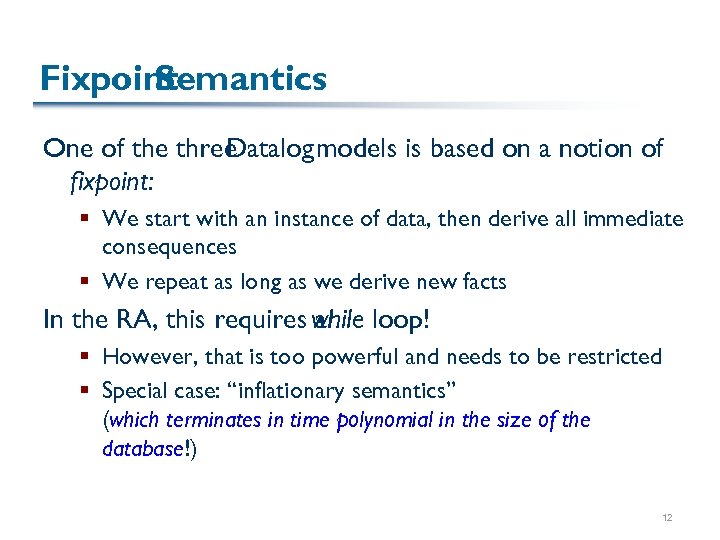

Fixpoint Semantics One of the three Datalog models is based on a notion of fixpoint: § We start with an instance of data, then derive all immediate consequences § We repeat as long as we derive new facts In the RA, this requires while loop! a § However, that is too powerful and needs to be restricted § Special case: “inflationary semantics” (which terminates in time polynomial in the size of the database!) 12

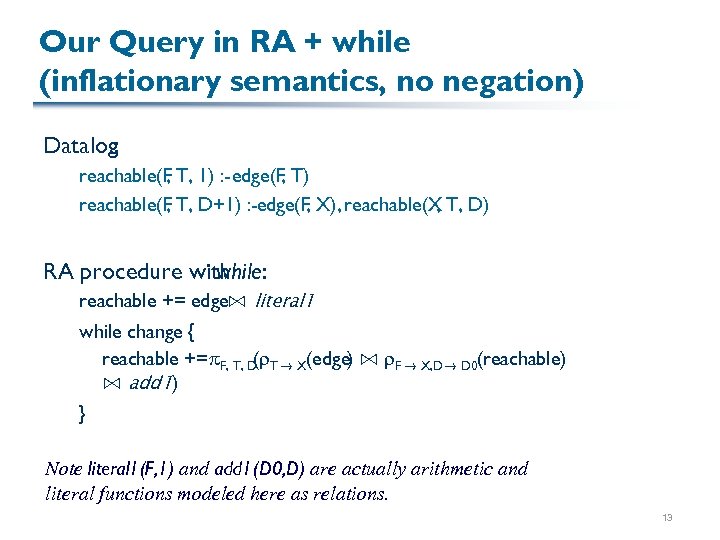

Our Query in RA + while (inflationary semantics, no negation) Datalog: reachable(F T, 1) : - edge(F T) , , reachable(F T, D+1) : -edge(F X), reachable(X T, D) , , , RA procedure with while: reachable += edge⋈ literal 1 while change { reachable += F, T, D( T ! X(edge) ⋈ F ! X, D ! D 0(reachable) ⋈ add 1) } Note literal 1(F, 1) and add 1(D 0, D) are actually arithmetic and literal functions modeled here as relations. 13

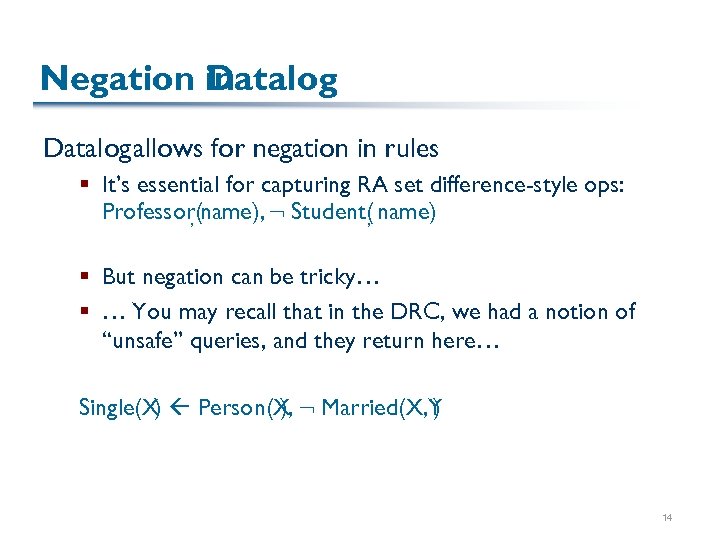

Negation in Datalog allows for negation in rules § It’s essential for capturing RA set difference-style ops: Professor(name), : Student( name) , , § But negation can be tricky… § … You may recall that in the DRC, we had a notion of “unsafe” queries, and they return here… Single(X Person(X : Married(X, Y ) ), ) 14

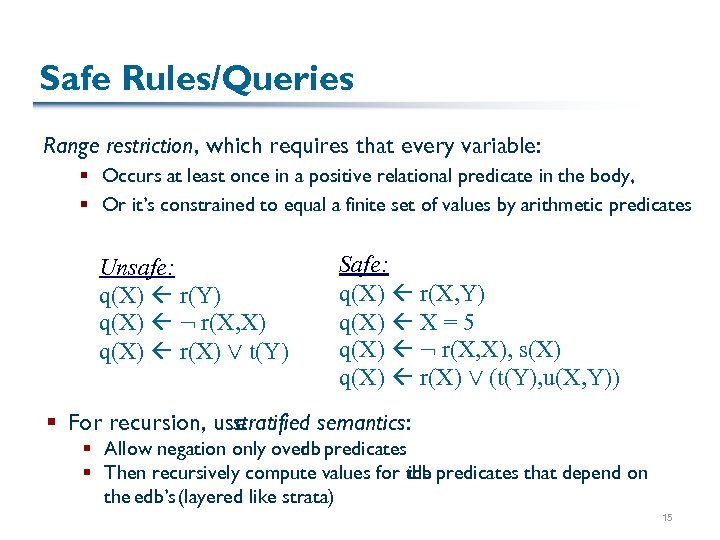

Safe Rules/Queries Range restriction, which requires that every variable: § Occurs at least once in a positive relational predicate in the body, § Or it’s constrained to equal a finite set of values by arithmetic predicates Unsafe: q(X) r(Y) q(X) : r(X, X) q(X) r(X) Ç t(Y) Safe: q(X) r(X, Y) q(X) X = 5 q(X) : r(X, X), s(X) q(X) r(X) Ç (t(Y), u(X, Y)) § For recursion, use stratified semantics: § Allow negation only over predicates edb § Then recursively compute values for the predicates that depend on idb the edb’s (layered like strata) 15

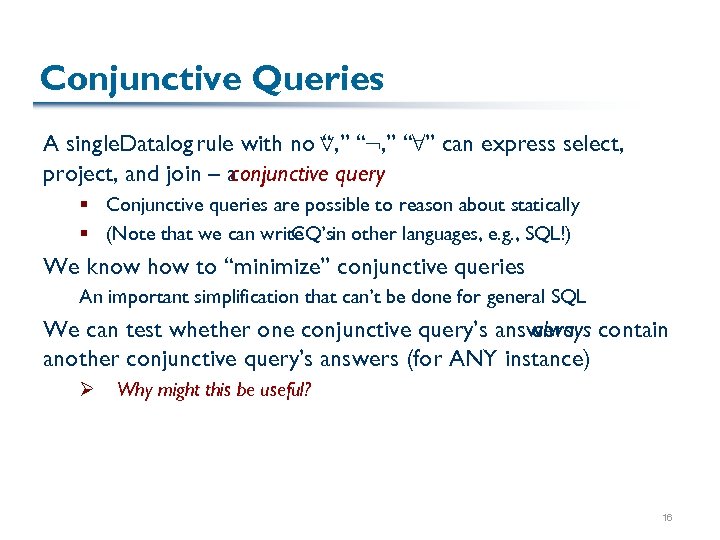

Conjunctive Queries A single. Datalog rule with no Ç, ” “: , ” “ 8” can express select, “ project, and join – a conjunctive query § Conjunctive queries are possible to reason about statically § (Note that we can write in other languages, e. g. , SQL!) CQ’s We know how to “minimize” conjunctive queries An important simplification that can’t be done for general SQL We can test whether one conjunctive query’s answers contain always another conjunctive query’s answers (for ANY instance) Ø Why might this be useful? 16

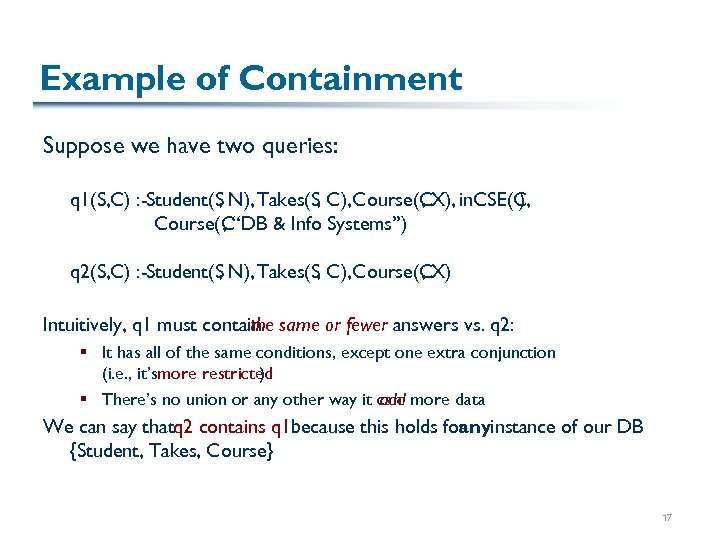

Example of Containment Suppose we have two queries: q 1(S, C) : -Student(S N), Takes(S, C), Course(CX), in. CSE(C , , ), Course(C“DB & Info Systems”) , q 2(S, C) : -Student(S N), Takes(S, C), Course(CX) , , Intuitively, q 1 must contain same or fewer answers vs. q 2: the § It has all of the same conditions, except one extra conjunction (i. e. , it’smore restricted ) § There’s no union or any other way it can more data add We can say thatq 2 contains q 1 because this holds for instance of our DB any {Student, Takes, Course} 17

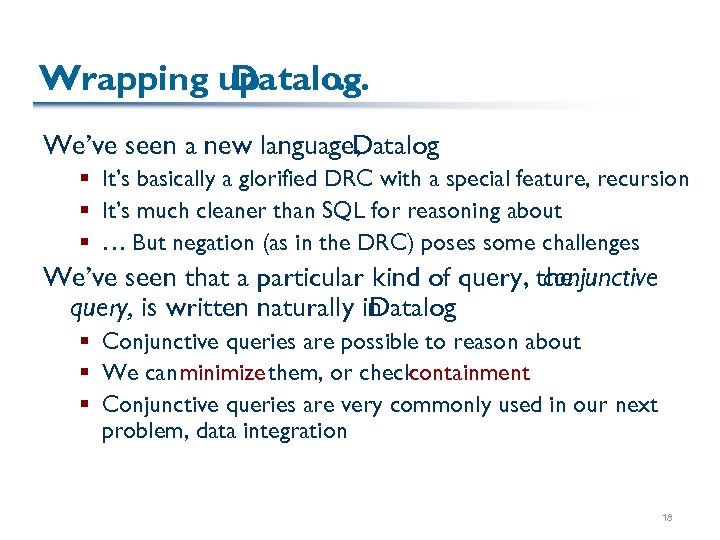

Wrapping up Datalog … We’ve seen a new language, Datalog § It’s basically a glorified DRC with a special feature, recursion § It’s much cleaner than SQL for reasoning about § … But negation (as in the DRC) poses some challenges We’ve seen that a particular kind of query, the conjunctive query, is written naturally in Datalog § Conjunctive queries are possible to reason about § We can minimize them, or check containment § Conjunctive queries are very commonly used in our next problem, data integration 18

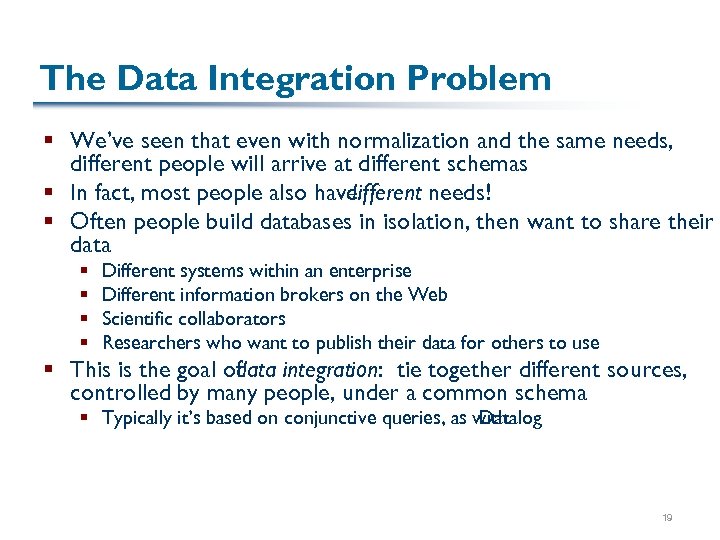

The Data Integration Problem § We’ve seen that even with normalization and the same needs, different people will arrive at different schemas § In fact, most people also have different needs! § Often people build databases in isolation, then want to share their data § § Different systems within an enterprise Different information brokers on the Web Scientific collaborators Researchers who want to publish their data for others to use § This is the goal of data integration: tie together different sources, controlled by many people, under a common schema § Typically it’s based on conjunctive queries, as with Datalog 19

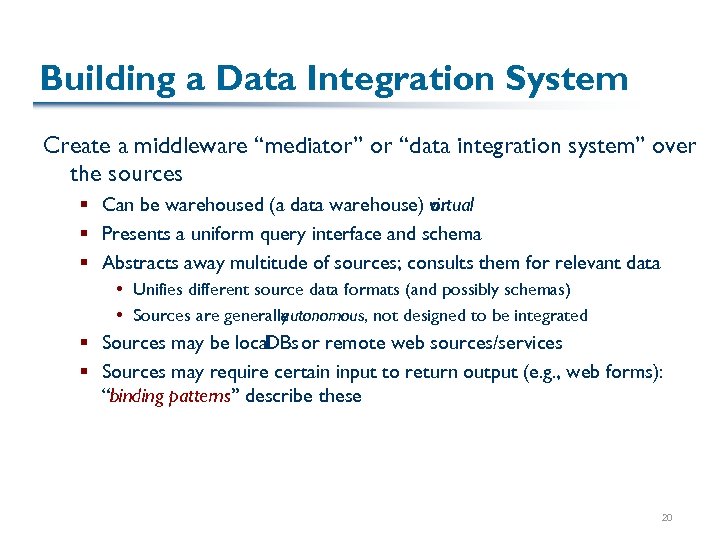

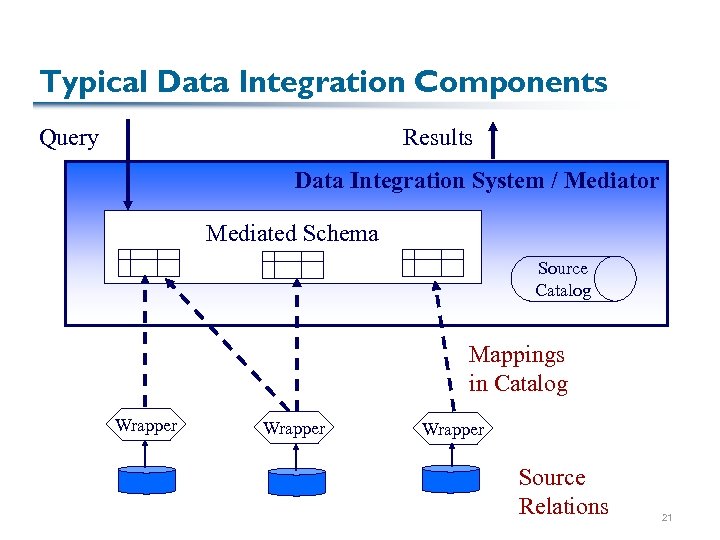

Building a Data Integration System Create a middleware “mediator” or “data integration system” over the sources § Can be warehoused (a data warehouse) virtual or § Presents a uniform query interface and schema § Abstracts away multitude of sources; consults them for relevant data Unifies different source data formats (and possibly schemas) Sources are generally autonomous, not designed to be integrated § Sources may be local or remote web sources/services DBs § Sources may require certain input to return output (e. g. , web forms): “binding patterns” describe these 20

Typical Data Integration Components Query Results Data Integration System / Mediator Mediated Schema Source Catalog Mappings in Catalog Wrapper Source Relations 21

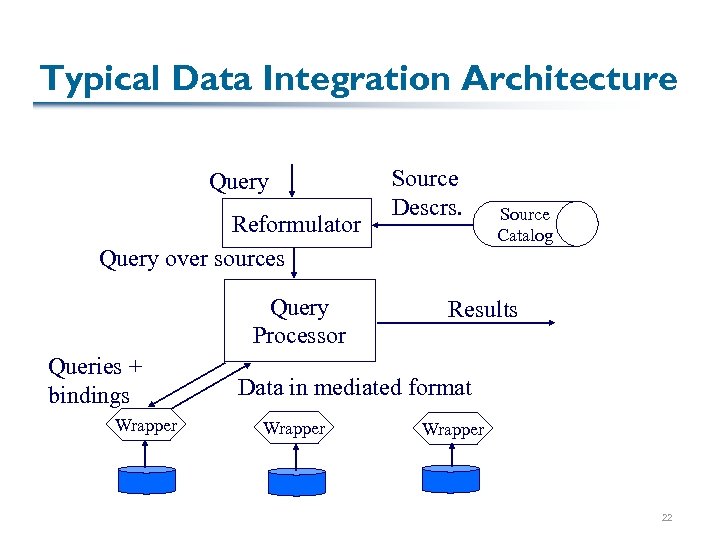

Typical Data Integration Architecture Query Reformulator Query over sources Query Processor Queries + bindings Wrapper Source Descrs. Source Catalog Results Data in mediated format Wrapper 22

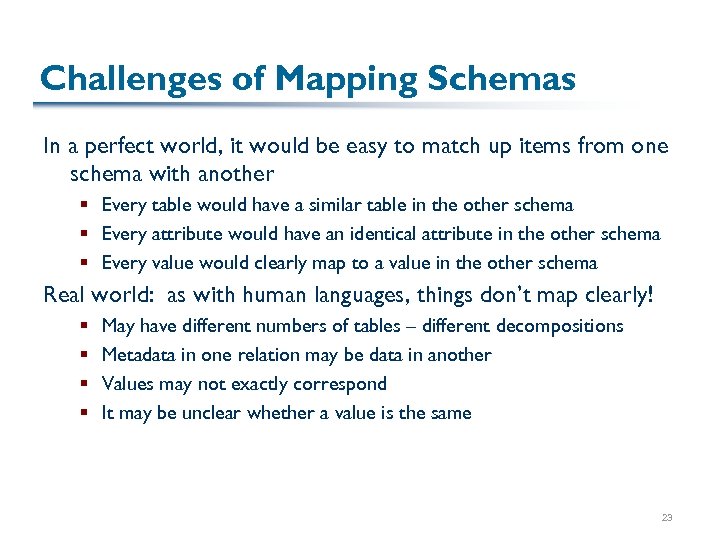

Challenges of Mapping Schemas In a perfect world, it would be easy to match up items from one schema with another § Every table would have a similar table in the other schema § Every attribute would have an identical attribute in the other schema § Every value would clearly map to a value in the other schema Real world: as with human languages, things don’t map clearly! § § May have different numbers of tables – different decompositions Metadata in one relation may be data in another Values may not exactly correspond It may be unclear whether a value is the same 23

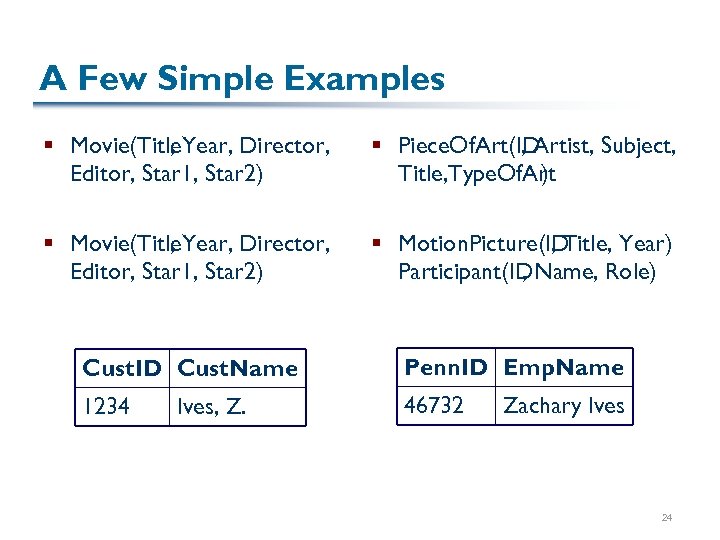

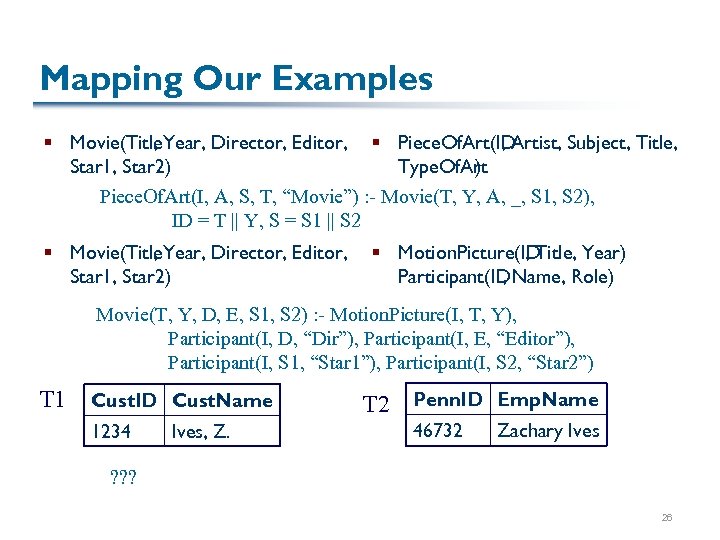

A Few Simple Examples § Movie(Title. Year, Director, , Editor, Star 1, Star 2) § Piece. Of. Art(ID , Artist, Subject, Title, Type. Of. Art ) § Movie(Title. Year, Director, , Editor, Star 1, Star 2) § Motion. Picture(ID , Title, Year) Participant(ID Name, Role) , Cust. ID Cust. Name Penn. ID Emp. Name 1234 46732 Ives, Z. Zachary Ives 24

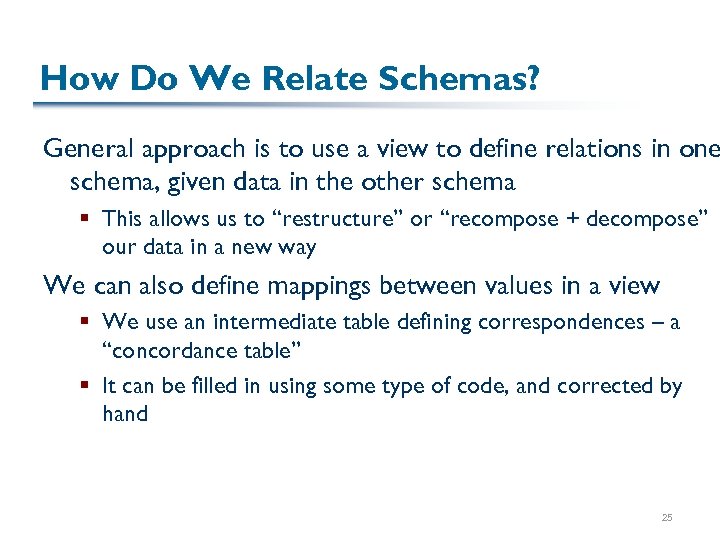

How Do We Relate Schemas? General approach is to use a view to define relations in one schema, given data in the other schema § This allows us to “restructure” or “recompose + decompose” our data in a new way We can also define mappings between values in a view § We use an intermediate table defining correspondences – a “concordance table” § It can be filled in using some type of code, and corrected by hand 25

Mapping Our Examples § Movie(Title. Year, Director, Editor, § Piece. Of. Art(ID , , Artist, Subject, Title, Star 1, Star 2) Type. Of. Art ) Piece. Of. Art(I, A, S, T, “Movie”) : - Movie(T, Y, A, _, S 1, S 2), ID = T || Y, S = S 1 || S 2 § Movie(Title. Year, Director, Editor, , Star 1, Star 2) § Motion. Picture(ID , Title, Year) Participant(ID Name, Role) , Movie(T, Y, D, E, S 1, S 2) : - Motion. Picture(I, T, Y), Participant(I, D, “Dir”), Participant(I, E, “Editor”), Participant(I, S 1, “Star 1”), Participant(I, S 2, “Star 2”) T 1 Cust. ID Cust. Name 1234 Ives, Z. T 2 Penn. ID Emp. Name 46732 Zachary Ives ? ? ? 26

![Two Important Approaches § TSIMMIS [Garcia-Molina+97]– Stanford § Focus: semistructured data (OEM), OQL-based language Two Important Approaches § TSIMMIS [Garcia-Molina+97]– Stanford § Focus: semistructured data (OEM), OQL-based language](https://present5.com/presentation/247f2ef74186b43c568c0097039266b0/image-27.jpg)

Two Important Approaches § TSIMMIS [Garcia-Molina+97]– Stanford § Focus: semistructured data (OEM), OQL-based language ( ) Lorel § Creates a mediated schema as a view over the sources § Spawned a UCSD project called MIX, which led to a company now owned by BEA Systems § Other important systems of this vein: Kleisli/K 2 @ Penn § Information Manifold [Levy+96] – AT&T Research § Focus: local-as-view mappings, relational model § Sources defined as views over mediated schema Requires a special § Spawned Tukwila at Washington, and eventually a company as well § Led to peer-to-peer integration approaches (Piazza, etc. ) 27

The Focus of these Systems § Focus: Web-based queryablesources § CGI forms, online databases, maybe a few RDBMSs § Each needs to be mapped into the system – not as easy as web search – but the benefits are significant vs. query engines § A few parenthetical notes: § Part of a slew of works on wrappers, source profiling, etc. § The creation of mappings can be partly automated – systems such as LSD, Cupid, Clio, … do this § Today most people look at integrating large enterprises (that’s where the $$$ is!) – Nimble, BEA, IBM 28

TSIMMIS § “The Stanford-IBM Manager of Multiple Information Sources” … or, a Yiddish stew § An instance of a “global-as-view” mediation system § One of the first systems to support semi-structured data, which predated XML by several years 29

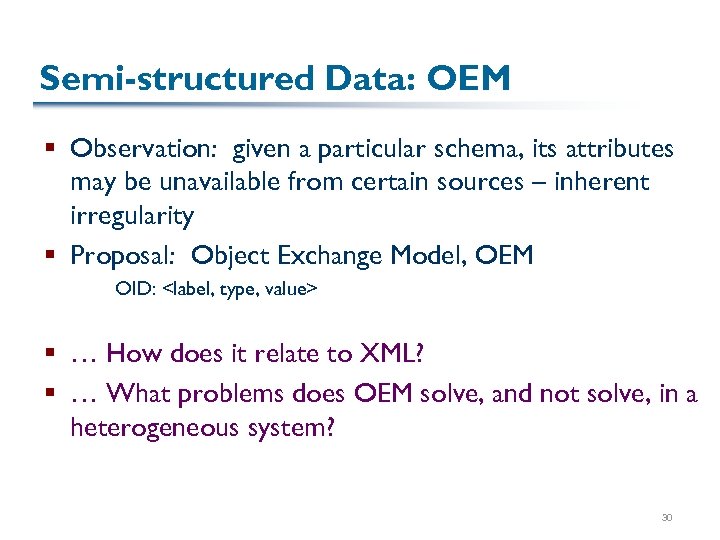

Semi-structured Data: OEM § Observation: given a particular schema, its attributes may be unavailable from certain sources – inherent irregularity § Proposal: Object Exchange Model, OEM OID: <label, type, value> § … How does it relate to XML? § … What problems does OEM solve, and not solve, in a heterogeneous system? 30

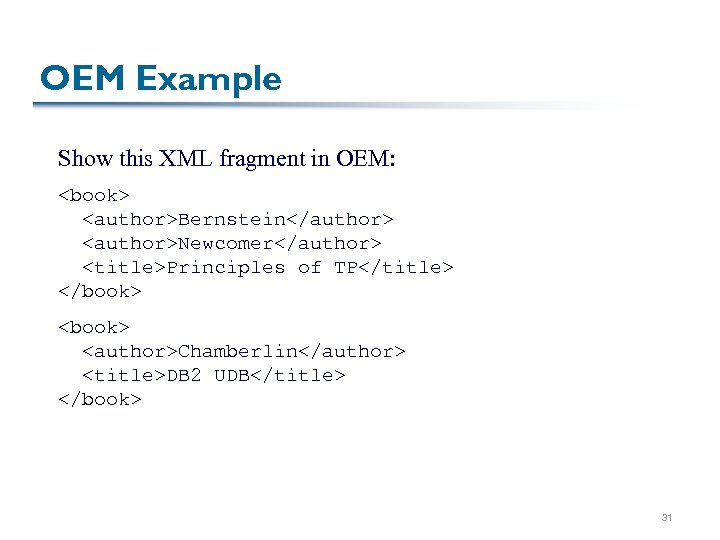

OEM Example Show this XML fragment in OEM: <book> <author>Bernstein</author> <author>Newcomer</author> <title>Principles of TP</title> </book> <author>Chamberlin</author> <title>DB 2 UDB</title> </book> 31

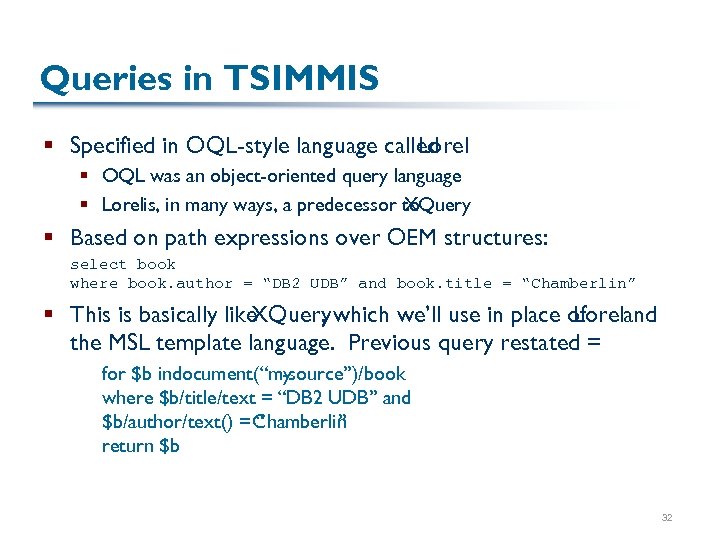

Queries in TSIMMIS § Specified in OQL-style language called Lorel § OQL was an object-oriented query language § Lorelis, in many ways, a predecessor to XQuery § Based on path expressions over OEM structures: select book where book. author = “DB 2 UDB” and book. title = “Chamberlin” § This is basically like XQuery which we’ll use in place of , Loreland the MSL template language. Previous query restated = for $b indocument(“mysource”)/book where $b/title/text = “DB 2 UDB” and $b/author/text() = Chamberlin “ ” return $b 32

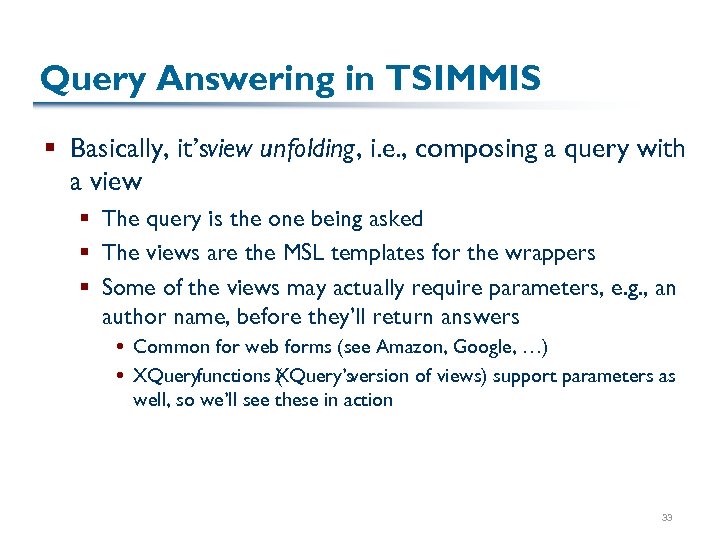

Query Answering in TSIMMIS § Basically, it’sview unfolding, i. e. , composing a query with a view § The query is the one being asked § The views are the MSL templates for the wrappers § Some of the views may actually require parameters, e. g. , an author name, before they’ll return answers Common for web forms (see Amazon, Google, …) XQueryfunctions XQuery’sversion of views) support parameters as ( well, so we’ll see these in action 33

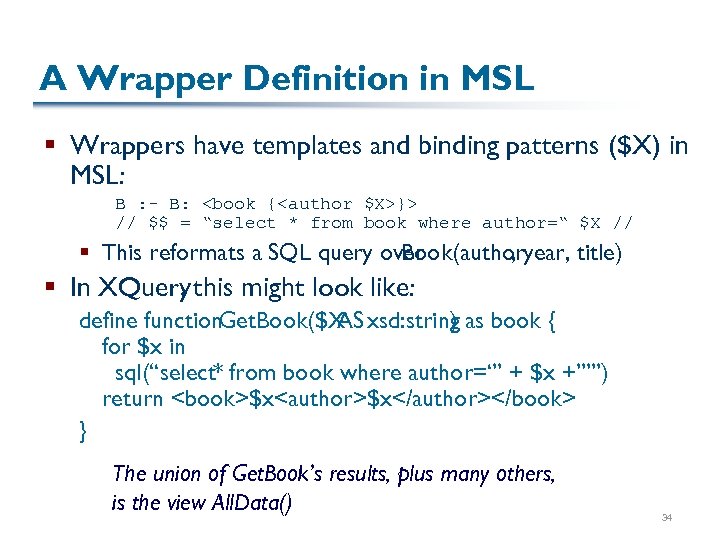

A Wrapper Definition in MSL § Wrappers have templates and binding patterns ($X) in MSL: B : - B: <book {<author $X>}> // $$ = “select * from book where author=“ $X // § This reformats a SQL query over Book(authoryear, title) , § In XQuery this might look like: , define function. Get. Book($X xsd: string as book { AS ) for $x in sql(“select* from book where author=‘” + $x +”’”) return <book>$x<author>$x</author></book> } The union of Get. Book’s results, plus many others, is the view All. Data() 34

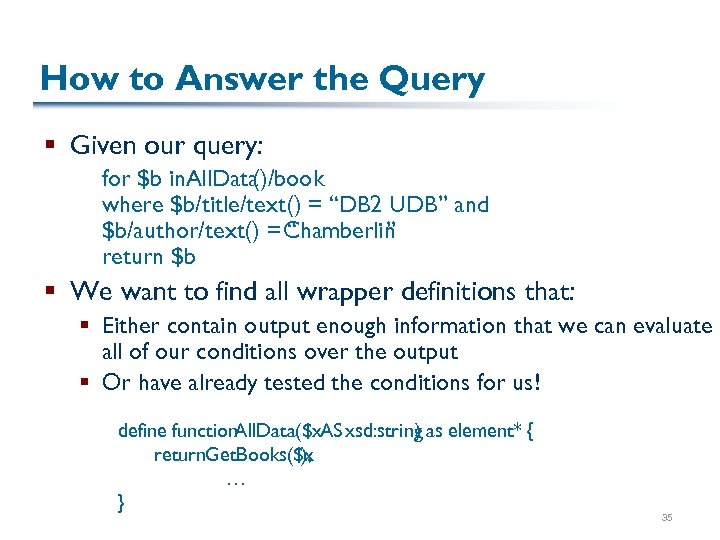

How to Answer the Query § Given our query: for $b in. All. Data ()/book where $b/title/text() = “DB 2 UDB” and $b/author/text() = Chamberlin “ ” return $b § We want to find all wrapper definitions that: § Either contain output enough information that we can evaluate all of our conditions over the output § Or have already tested the conditions for us! define function. All. Data($x. AS xsd: string as element* { ) return. Get. Books($x ), … } 35

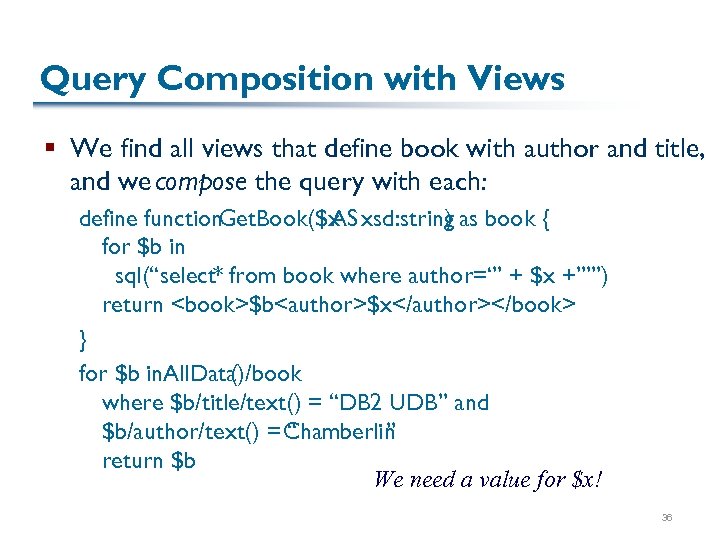

Query Composition with Views § We find all views that define book with author and title, and we compose the query with each: define function. Get. Book($x xsd: string as book { AS ) for $b in sql(“select* from book where author=‘” + $x +”’”) return <book>$b<author>$x</author></book> } for $b in. All. Data ()/book where $b/title/text() = “DB 2 UDB” and $b/author/text() = Chamberlin “ ” return $b We need a value for $x! 36

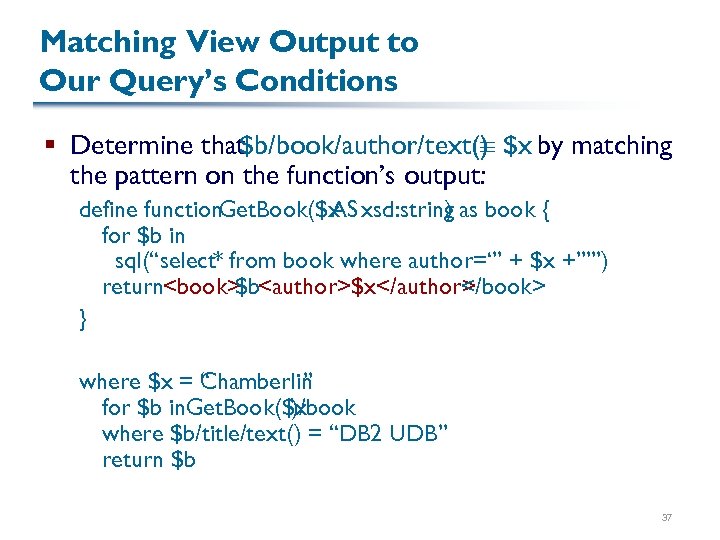

Matching View Output to Our Query’s Conditions § Determine that $b/book/author/text() $x by matching the pattern on the function’s output: define function. Get. Book($x xsd: string as book { AS ) for $b in sql(“select* from book where author=‘” + $x +”’”) return<book> $b<author>$x</author>/book> < } where $x = Chamberlin “ ” for $b in. Get. Book($x )/book where $b/title/text() = “DB 2 UDB” return $b 37

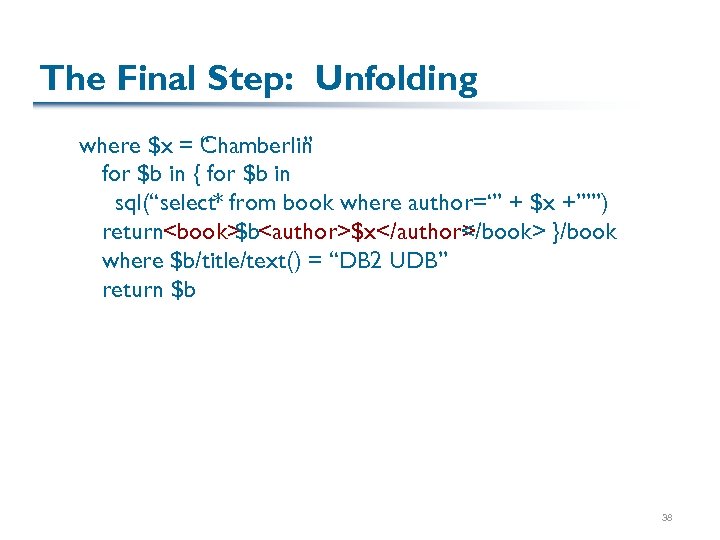

The Final Step: Unfolding where $x = Chamberlin “ ” for $b in { for $b in sql(“select* from book where author=‘” + $x +”’”) return<book> $b<author>$x</author>/book> }/book < where $b/title/text() = “DB 2 UDB” return $b 38

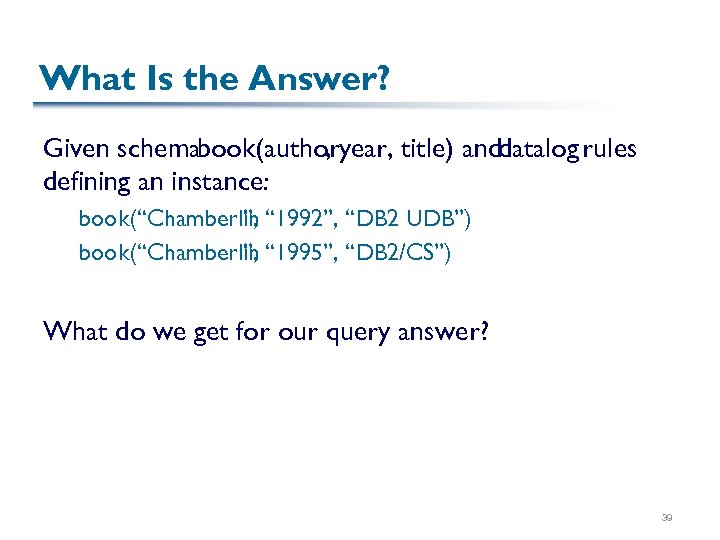

What Is the Answer? Given schemabook(authoryear, title) anddatalog rules , defining an instance: book(“Chamberlin “ 1992”, “DB 2 UDB”) ”, book(“Chamberlin “ 1995”, “DB 2/CS”) ”, What do we get for our query answer? 39

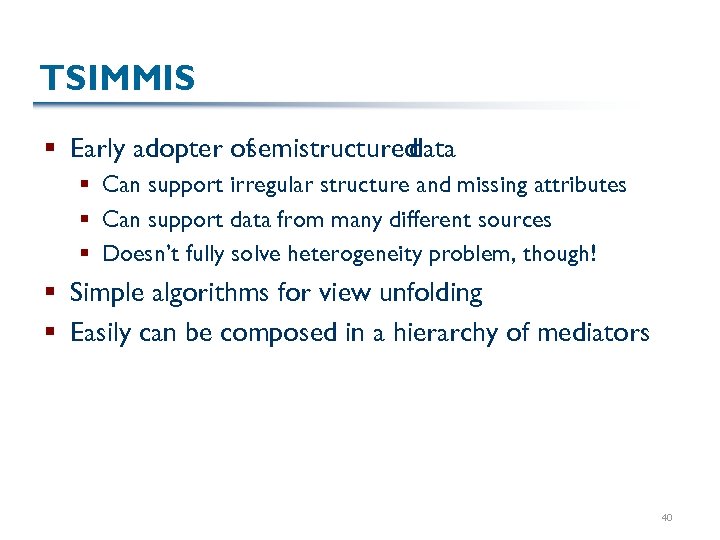

TSIMMIS § Early adopter of semistructured data § Can support irregular structure and missing attributes § Can support data from many different sources § Doesn’t fully solve heterogeneity problem, though! § Simple algorithms for view unfolding § Easily can be composed in a hierarchy of mediators 40

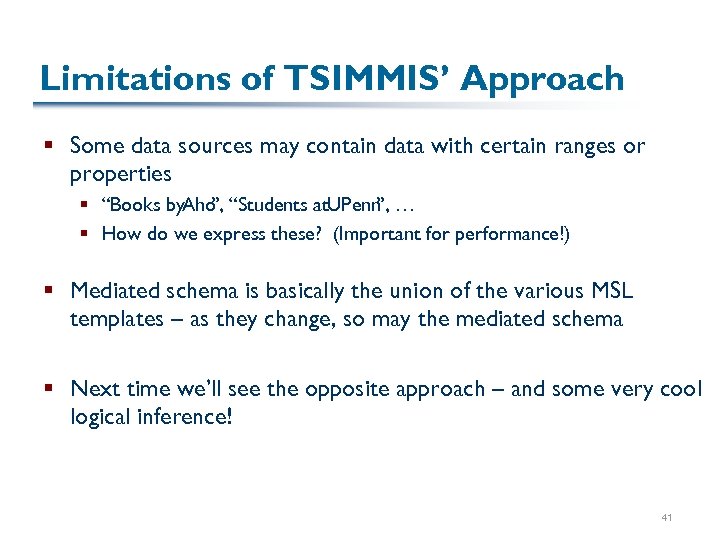

Limitations of TSIMMIS’ Approach § Some data sources may contain data with certain ranges or properties § “Books by. Aho “Students at. UPenn … ”, ”, § How do we express these? (Important for performance!) § Mediated schema is basically the union of the various MSL templates – as they change, so may the mediated schema § Next time we’ll see the opposite approach – and some very cool logical inference! 41

247f2ef74186b43c568c0097039266b0.ppt