fce80b2b48b6dbfdcfa949fd3aca47e4.ppt

- Количество слайдов: 70

Real-Time Systems

Real-Time Systems

Real-time research repository § For information on real-time research groups, conferences, journals, books, products, etc. , have a look at: http: //cs-www. bu. edu/pub/ieee-rts/Home. html

Real-time research repository § For information on real-time research groups, conferences, journals, books, products, etc. , have a look at: http: //cs-www. bu. edu/pub/ieee-rts/Home. html

Introduction § A real-time system is a system whose specification includes both a logical and a temporal correctness requirement. § Logical correctness: produce correct output. § Can be checked by various means including Hoare axiomatics and other formal methods. § Temporal correctness: produces output at the right time. § A soft real-time system is one that can tolerate some delay in delivering the result. § A hard real-time system is one that can not afford to miss a dealine.

Introduction § A real-time system is a system whose specification includes both a logical and a temporal correctness requirement. § Logical correctness: produce correct output. § Can be checked by various means including Hoare axiomatics and other formal methods. § Temporal correctness: produces output at the right time. § A soft real-time system is one that can tolerate some delay in delivering the result. § A hard real-time system is one that can not afford to miss a dealine.

Characteristics of real-time systems § § § Event-driven, reactive High cost of failure Concurrency/multiprogramming Stand-alone/continuous operation. Reliability/fault tolerance requirements PREDICTABLE BEHAVIOR

Characteristics of real-time systems § § § Event-driven, reactive High cost of failure Concurrency/multiprogramming Stand-alone/continuous operation. Reliability/fault tolerance requirements PREDICTABLE BEHAVIOR

Misconceptions about real-time systems § There is no science in real-time-system design. § We shall see… § Advances in supercomputing hardware will take care of real-time requirements. § The old “buy a faster processor” argument… § Real-time computing is equivalent to fast computing. § Only to ad agencies. To us, it means PREDICTABLE computing.

Misconceptions about real-time systems § There is no science in real-time-system design. § We shall see… § Advances in supercomputing hardware will take care of real-time requirements. § The old “buy a faster processor” argument… § Real-time computing is equivalent to fast computing. § Only to ad agencies. To us, it means PREDICTABLE computing.

Misconceptions about real-time systems § Real-time programming is assembly coding, … § We would like to automate (as much as possible) realtime system design, instead of relying on clever handcrafted code. § “Real time” is performance engineering. § In real-time computing, timeliness is almost always more important than raw performance … § “Real-time problems” have all been solved in other areas of CS or operations research. § OR people typically use stochastic queuing models or one-shot scheduling models to reason about systems. § CS people are usually interested in optimizing average -case performance.

Misconceptions about real-time systems § Real-time programming is assembly coding, … § We would like to automate (as much as possible) realtime system design, instead of relying on clever handcrafted code. § “Real time” is performance engineering. § In real-time computing, timeliness is almost always more important than raw performance … § “Real-time problems” have all been solved in other areas of CS or operations research. § OR people typically use stochastic queuing models or one-shot scheduling models to reason about systems. § CS people are usually interested in optimizing average -case performance.

Misconceptions about real-time systems § It is not meaningful to talk about guaranteeing real-time performance when things can fail. § Though things may fail, we certainly don’t want the operating system to be the weakest link! § Real-time systems function in a static environment. § Not true. We consider systems in which the operating mode may change dynamically.

Misconceptions about real-time systems § It is not meaningful to talk about guaranteeing real-time performance when things can fail. § Though things may fail, we certainly don’t want the operating system to be the weakest link! § Real-time systems function in a static environment. § Not true. We consider systems in which the operating mode may change dynamically.

Are all systems real-time systems? § Question: Is a payroll processing system a real-time system? § It has a time constraint: Print the pay checks every month. § Perhaps it is a real-time system in a definitional sense, but it doesn’t pay us to view it as such. § We are interested in systems for which it is not a priori obvious how to meet timing constraints.

Are all systems real-time systems? § Question: Is a payroll processing system a real-time system? § It has a time constraint: Print the pay checks every month. § Perhaps it is a real-time system in a definitional sense, but it doesn’t pay us to view it as such. § We are interested in systems for which it is not a priori obvious how to meet timing constraints.

Resources § Resources may be categorized as: § Abundant: Virtually any system design methodology can be used to realize the timing requirements of the application. § Insufficient: The application is ahead of the technology curve; no design methodology can be used to realize the timing requirements of the application. § Sufficient but scarce: It is possible to realize the timing requirements of the application, but careful resource allocation is required.

Resources § Resources may be categorized as: § Abundant: Virtually any system design methodology can be used to realize the timing requirements of the application. § Insufficient: The application is ahead of the technology curve; no design methodology can be used to realize the timing requirements of the application. § Sufficient but scarce: It is possible to realize the timing requirements of the application, but careful resource allocation is required.

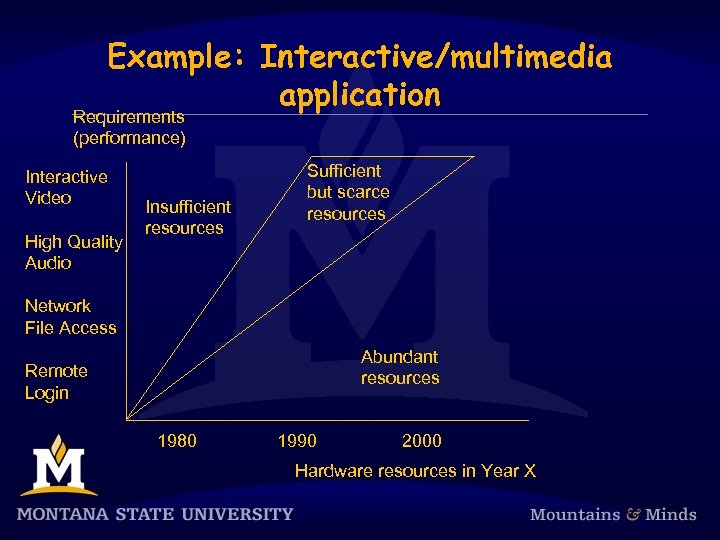

Example: Interactive/multimedia application Requirements (performance) Interactive Video High Quality Audio Insufficient resources Sufficient but scarce resources Network File Access Abundant resources Remote Login 1980 1990 2000 Hardware resources in Year X

Example: Interactive/multimedia application Requirements (performance) Interactive Video High Quality Audio Insufficient resources Sufficient but scarce resources Network File Access Abundant resources Remote Login 1980 1990 2000 Hardware resources in Year X

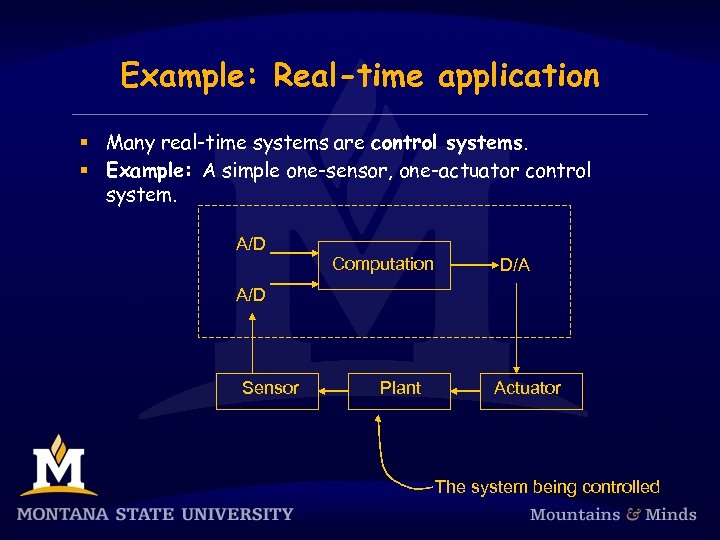

Example: Real-time application § Many real-time systems are control systems. § Example: A simple one-sensor, one-actuator control system. A/D Computation D/A A/D Sensor Plant Actuator The system being controlled

Example: Real-time application § Many real-time systems are control systems. § Example: A simple one-sensor, one-actuator control system. A/D Computation D/A A/D Sensor Plant Actuator The system being controlled

Simple control system § Pseudo-code for this system: set timer to interrupt periodically with period T; at each timer interrupt do do analog-to-digital conversion to get y; compute control output u; output u and do digital-to-analog conversion; od § T is called the sampling period. T is a key design choice. Typical range for T: seconds to milliseconds.

Simple control system § Pseudo-code for this system: set timer to interrupt periodically with period T; at each timer interrupt do do analog-to-digital conversion to get y; compute control output u; output u and do digital-to-analog conversion; od § T is called the sampling period. T is a key design choice. Typical range for T: seconds to milliseconds.

Multi-rate control systems § Example Helicopter flight controller. Do the following in each 1/180 -sec. cycle: validate sensor data and select data source; if failure, reconfigure the system Every sixth cycle do: keyboard input and mode selection; data normalization and coordinate transformation; tracking reference update control laws of the outer pitch-control loop; control laws of the outer roll-control loop; control laws of the outer yaw- and collectivecontrol loop Every other cycle do: control laws of the inner pitch-control loop; control laws of the inner roll- and collectivecontrol loop; Compute the control laws of the inner yaw-control loop; Output commands; Carry out built-in test; Wait until beginning of the next cycle § § Note: Having only harmonic rates simplifies the system. More complicated control systems have multiple sensors and actuators and must support control loops of different rates.

Multi-rate control systems § Example Helicopter flight controller. Do the following in each 1/180 -sec. cycle: validate sensor data and select data source; if failure, reconfigure the system Every sixth cycle do: keyboard input and mode selection; data normalization and coordinate transformation; tracking reference update control laws of the outer pitch-control loop; control laws of the outer roll-control loop; control laws of the outer yaw- and collectivecontrol loop Every other cycle do: control laws of the inner pitch-control loop; control laws of the inner roll- and collectivecontrol loop; Compute the control laws of the inner yaw-control loop; Output commands; Carry out built-in test; Wait until beginning of the next cycle § § Note: Having only harmonic rates simplifies the system. More complicated control systems have multiple sensors and actuators and must support control loops of different rates.

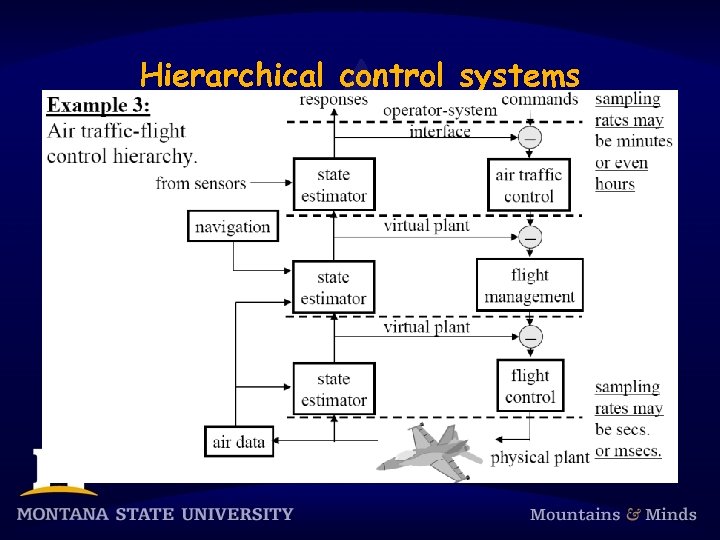

Hierarchical control systems

Hierarchical control systems

Signal processing systems § Signal-processing systems transform data from one form to another. § Examples: § Digital filtering. § Video and voice compression/decompression. § Radar signal processing. § Response times range from a few milliseconds to a few seconds.

Signal processing systems § Signal-processing systems transform data from one form to another. § Examples: § Digital filtering. § Video and voice compression/decompression. § Radar signal processing. § Response times range from a few milliseconds to a few seconds.

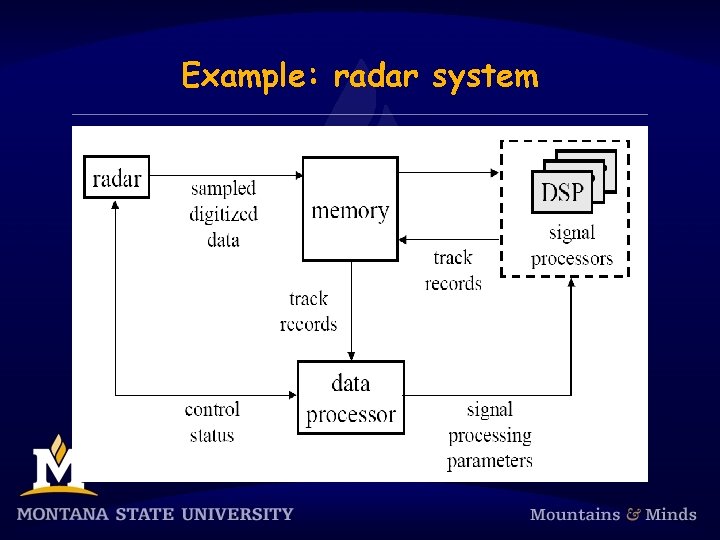

Example: radar system

Example: radar system

Other real-time applications § § Real-time databases. § Transactions must complete by deadlines. § Main dilemma: Transaction scheduling algorithms and real-time scheduling algorithms often have conflicting goals. § Data may be subject to absolute and relative temporal consistency requirements. Multimedia. § Want to process audio and video frames at steady rates. § TV video rate is 30 frames/sec. HDTV is 60 frames/sec. § Telephone audio is 16 Kbits/sec. CD audio is 128 Kbits/sec. § Other requirements: Lip synchronization, low jitter, low end-to -end response times (if interactive).

Other real-time applications § § Real-time databases. § Transactions must complete by deadlines. § Main dilemma: Transaction scheduling algorithms and real-time scheduling algorithms often have conflicting goals. § Data may be subject to absolute and relative temporal consistency requirements. Multimedia. § Want to process audio and video frames at steady rates. § TV video rate is 30 frames/sec. HDTV is 60 frames/sec. § Telephone audio is 16 Kbits/sec. CD audio is 128 Kbits/sec. § Other requirements: Lip synchronization, low jitter, low end-to -end response times (if interactive).

Hard vs. soft real-time § Task: A sequential piece of code. § Job: Instance of a task. § Jobs require resources to execute. § Example resources: CPU, network, disk, critical section. § We will simply call hardware resources “processors”. § Release time of a job: The time instant the job becomes ready to execute. § Deadline of a job: The time instant by which the job must complete execution. § Relative deadline of a job: “Deadline - Release time”. § Response time of a job: “Completion time - Release time”.

Hard vs. soft real-time § Task: A sequential piece of code. § Job: Instance of a task. § Jobs require resources to execute. § Example resources: CPU, network, disk, critical section. § We will simply call hardware resources “processors”. § Release time of a job: The time instant the job becomes ready to execute. § Deadline of a job: The time instant by which the job must complete execution. § Relative deadline of a job: “Deadline - Release time”. § Response time of a job: “Completion time - Release time”.

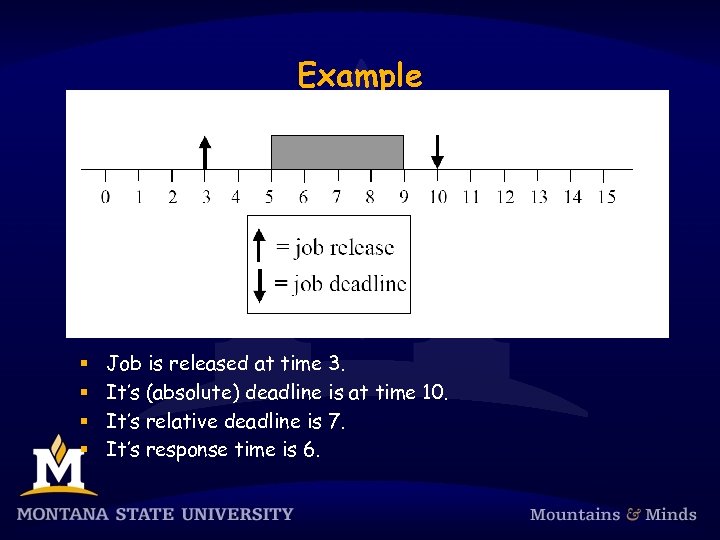

Example § § Job is released at time 3. It’s (absolute) deadline is at time 10. It’s relative deadline is 7. It’s response time is 6.

Example § § Job is released at time 3. It’s (absolute) deadline is at time 10. It’s relative deadline is 7. It’s response time is 6.

Hard real-time systems § A hard deadline must be met. § If any hard deadline is ever missed, then the system is incorrect. § Requires a means for validating that deadlines are met. § Hard real-time system: A real-time system in which all deadlines are hard. § Examples: Nuclear power plant control, flight control.

Hard real-time systems § A hard deadline must be met. § If any hard deadline is ever missed, then the system is incorrect. § Requires a means for validating that deadlines are met. § Hard real-time system: A real-time system in which all deadlines are hard. § Examples: Nuclear power plant control, flight control.

Soft real-time systems § A soft deadline may occasionally be missed. § Question: How to define “occasionally”? § Soft real-time system: A real-time system in which some deadlines are soft. § Examples: Telephone switches, multimedia applications.

Soft real-time systems § A soft deadline may occasionally be missed. § Question: How to define “occasionally”? § Soft real-time system: A real-time system in which some deadlines are soft. § Examples: Telephone switches, multimedia applications.

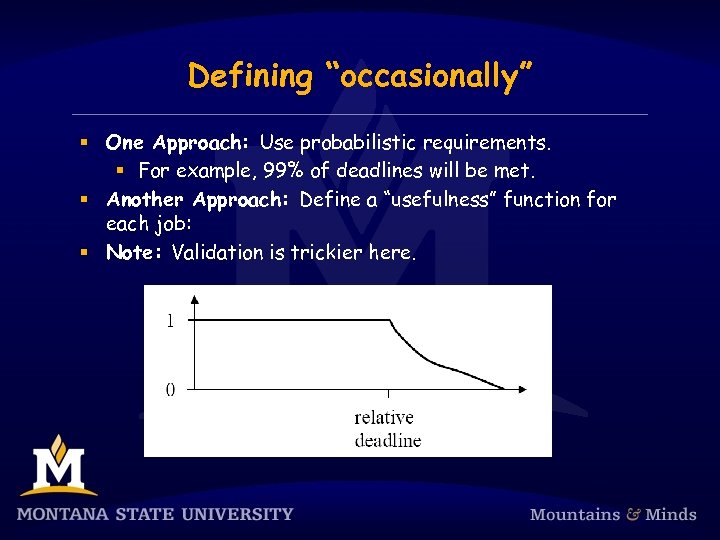

Defining “occasionally” § One Approach: Use probabilistic requirements. § For example, 99% of deadlines will be met. § Another Approach: Define a “usefulness” function for each job: § Note: Validation is trickier here.

Defining “occasionally” § One Approach: Use probabilistic requirements. § For example, 99% of deadlines will be met. § Another Approach: Define a “usefulness” function for each job: § Note: Validation is trickier here.

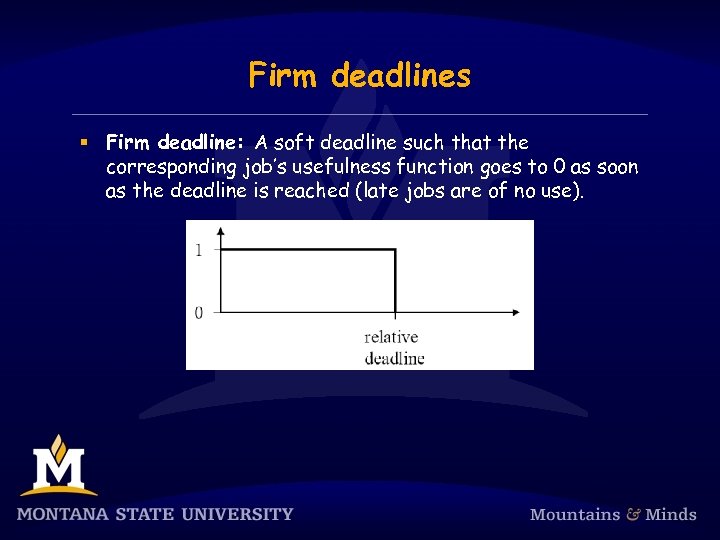

Firm deadlines § Firm deadline: A soft deadline such that the corresponding job’s usefulness function goes to 0 as soon as the deadline is reached (late jobs are of no use).

Firm deadlines § Firm deadline: A soft deadline such that the corresponding job’s usefulness function goes to 0 as soon as the deadline is reached (late jobs are of no use).

Reference model § Each job Ji is characterized by its release time ri, absolute deadline di, relative deadline Di, and execution time ei. § Sometimes a range of release times is specified: [ri-, ri+]. This range is called release-time jitter. § Likewise, sometimes instead of ei, execution time is specified to range over [ei-, ei+]. § Note: It can be difficult to get a precise estimate of ei

Reference model § Each job Ji is characterized by its release time ri, absolute deadline di, relative deadline Di, and execution time ei. § Sometimes a range of release times is specified: [ri-, ri+]. This range is called release-time jitter. § Likewise, sometimes instead of ei, execution time is specified to range over [ei-, ei+]. § Note: It can be difficult to get a precise estimate of ei

Periodic, sporadic aperiodic tasks § Periodic task: § We associate a period pi with each task Ti. § pi is the time between job releases. § Sporadic and aperiodic tasks: Released at arbitrary times. § Sporadic: Has a hard deadline. § Aperiodic: Has no deadline or a soft deadline.

Periodic, sporadic aperiodic tasks § Periodic task: § We associate a period pi with each task Ti. § pi is the time between job releases. § Sporadic and aperiodic tasks: Released at arbitrary times. § Sporadic: Has a hard deadline. § Aperiodic: Has no deadline or a soft deadline.

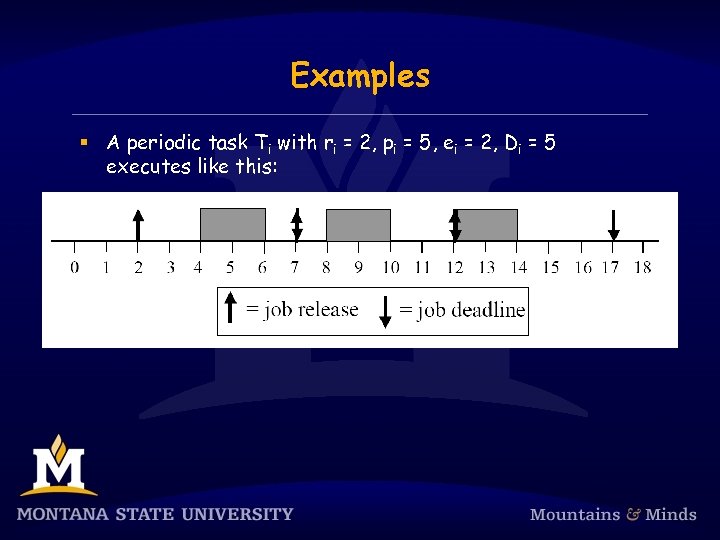

Examples § A periodic task Ti with ri = 2, pi = 5, ei = 2, Di = 5 executes like this:

Examples § A periodic task Ti with ri = 2, pi = 5, ei = 2, Di = 5 executes like this:

Some definitions for periodic task systems § The jobs of task Ti are denoted Ji, 1, Ji, 2, …. § ri, 1 (the release time of Ji, 1) is called the phase of Ti. § Synchronous System: Each task has a phase of 0. § Asynchronous System: Phases are arbitrary. § Hyperperiod: Least common multiple of {pi}. § Task utilization: ui = ei/pi. § System utilization: U = Σi=1. . nui.

Some definitions for periodic task systems § The jobs of task Ti are denoted Ji, 1, Ji, 2, …. § ri, 1 (the release time of Ji, 1) is called the phase of Ti. § Synchronous System: Each task has a phase of 0. § Asynchronous System: Phases are arbitrary. § Hyperperiod: Least common multiple of {pi}. § Task utilization: ui = ei/pi. § System utilization: U = Σi=1. . nui.

Task dependencies § Two main kinds of dependencies: § Critical Sections. § Precedence Constraints. § For example, job Ji may be constrained to be released only after job Jk completes. § Tasks with no dependencies are called independent.

Task dependencies § Two main kinds of dependencies: § Critical Sections. § Precedence Constraints. § For example, job Ji may be constrained to be released only after job Jk completes. § Tasks with no dependencies are called independent.

Scheduling algorithms § We are generally interested in two kinds of algorithms: 1. A scheduler or scheduling algorithm, which generates a schedule at runtime. 2. A feasibility analysis algorithm, which checks if timing constraints are met. § Usually (but not always) Algorithm 1 is pretty straightforward, while Algorithm 2 is more complex.

Scheduling algorithms § We are generally interested in two kinds of algorithms: 1. A scheduler or scheduling algorithm, which generates a schedule at runtime. 2. A feasibility analysis algorithm, which checks if timing constraints are met. § Usually (but not always) Algorithm 1 is pretty straightforward, while Algorithm 2 is more complex.

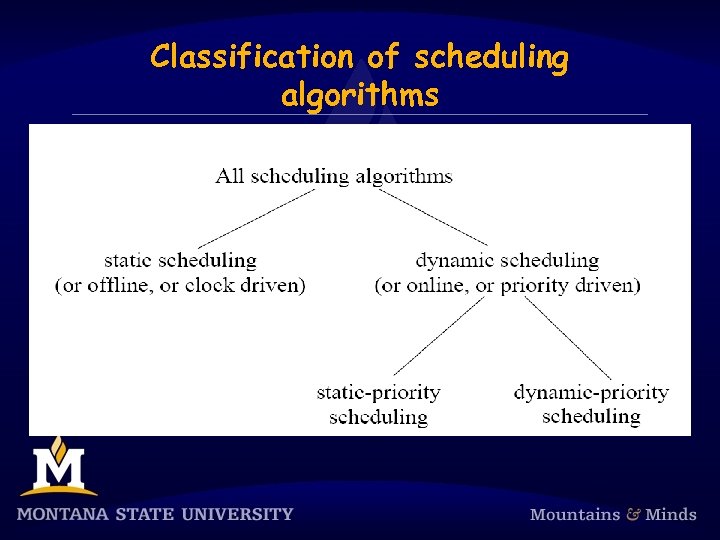

Classification of scheduling algorithms

Classification of scheduling algorithms

Optimality and feasibility § A schedule is feasible if all timing constraints are met. § The term “correct” is probably better — see the next slide. § A task set T is schedulable using scheduling algorithm A if A always produces a feasible schedule for T. § A scheduling algorithm is optimal if it always produces a feasible schedule when one exists (under any scheduling algorithm). § Can similarly define optimality for a class of schedulers, e. g. , “an optimal static-priority scheduling algorithm. ”

Optimality and feasibility § A schedule is feasible if all timing constraints are met. § The term “correct” is probably better — see the next slide. § A task set T is schedulable using scheduling algorithm A if A always produces a feasible schedule for T. § A scheduling algorithm is optimal if it always produces a feasible schedule when one exists (under any scheduling algorithm). § Can similarly define optimality for a class of schedulers, e. g. , “an optimal static-priority scheduling algorithm. ”

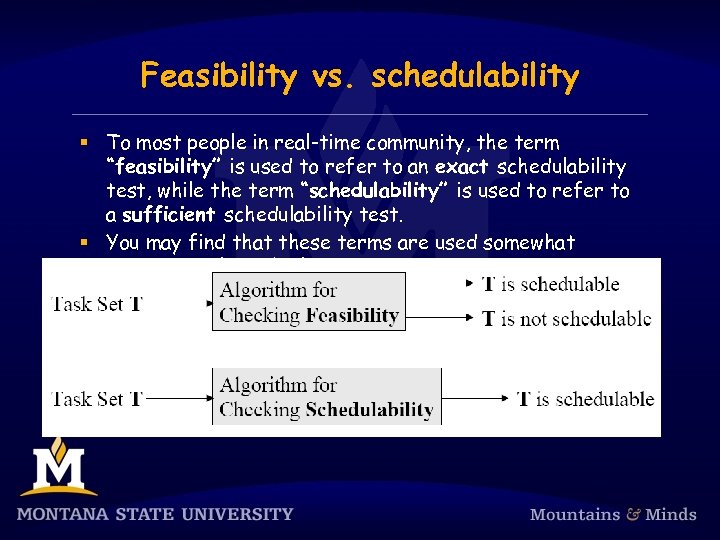

Feasibility vs. schedulability § To most people in real-time community, the term “feasibility” is used to refer to an exact schedulability test, while the term “schedulability” is used to refer to a sufficient schedulability test. § You may find that these terms are used somewhat inconsistently in the literature.

Feasibility vs. schedulability § To most people in real-time community, the term “feasibility” is used to refer to an exact schedulability test, while the term “schedulability” is used to refer to a sufficient schedulability test. § You may find that these terms are used somewhat inconsistently in the literature.

Clock driven (or static) scheduling § Model assumes § n periodic tasks T 1, …, Tn. § The “rest of the world” periodic model is assumed. § Ti is specified by (fi, pi, ei, Di), where § fi is its phase, § pi is its period, § ei is its execution cost per job, and § Di is its relative deadline. § Will abbreviate as (pi, ei, Di) if fi=0, and (pi, ei) if fi=0 ∧ pi=Di. § We also have aperiodic jobs that are released at arbitrary times

Clock driven (or static) scheduling § Model assumes § n periodic tasks T 1, …, Tn. § The “rest of the world” periodic model is assumed. § Ti is specified by (fi, pi, ei, Di), where § fi is its phase, § pi is its period, § ei is its execution cost per job, and § Di is its relative deadline. § Will abbreviate as (pi, ei, Di) if fi=0, and (pi, ei) if fi=0 ∧ pi=Di. § We also have aperiodic jobs that are released at arbitrary times

Schedule table { § Our scheduler will schedule periodic jobs using a static schedule that is computed offline and stored in a table T. § T(tk) = Ti if Ti is to be scheduled at time tk I if no periodic task is scheduled at time tk § For most of this chapter, we assume the table is given. § Later, we consider one algorithm for producing the table. § Note: This algorithm need not be highly efficient. § We will schedule aperiodic jobs (if any are ready) in intervals not used by periodic jobs.

Schedule table { § Our scheduler will schedule periodic jobs using a static schedule that is computed offline and stored in a table T. § T(tk) = Ti if Ti is to be scheduled at time tk I if no periodic task is scheduled at time tk § For most of this chapter, we assume the table is given. § Later, we consider one algorithm for producing the table. § Note: This algorithm need not be highly efficient. § We will schedule aperiodic jobs (if any are ready) in intervals not used by periodic jobs.

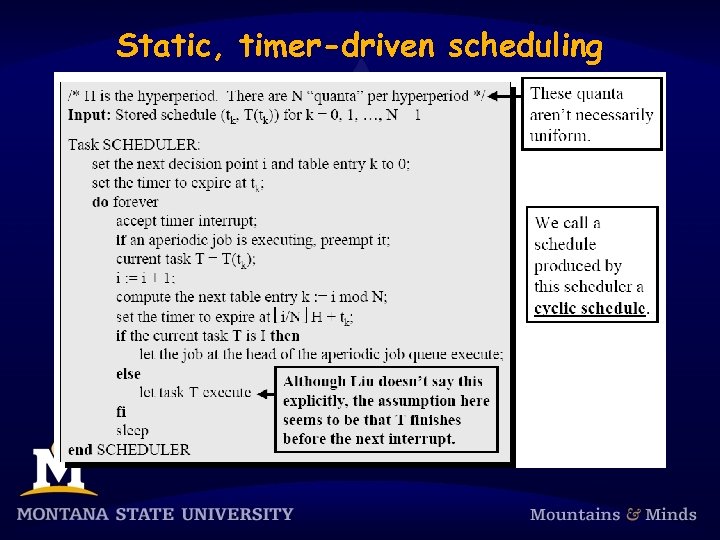

Static, timer-driven scheduling

Static, timer-driven scheduling

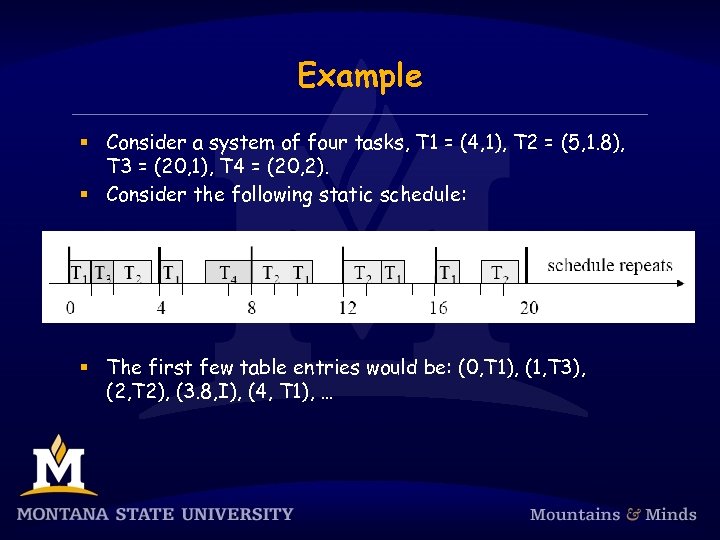

Example § Consider a system of four tasks, T 1 = (4, 1), T 2 = (5, 1. 8), T 3 = (20, 1), T 4 = (20, 2). § Consider the following static schedule: § The first few table entries would be: (0, T 1), (1, T 3), (2, T 2), (3. 8, I), (4, T 1), …

Example § Consider a system of four tasks, T 1 = (4, 1), T 2 = (5, 1. 8), T 3 = (20, 1), T 4 = (20, 2). § Consider the following static schedule: § The first few table entries would be: (0, T 1), (1, T 3), (2, T 2), (3. 8, I), (4, T 1), …

Frames § Let us refine this notion of scheduling… § To keep the table small, we divide the time line into frames and make scheduling decisions only at frame boundaries. § Each job is executed as a procedure call that must fit within a frame. § Multiple jobs may be executed in a frame, but the table is only examined at frame boundaries (the number of “columns” in the table = the number of frames per hyperperiod). § In addition to making scheduling decisions, the scheduler also checks for various error conditions, like task overruns, at the beginning of each frame. § We let f denote the frame size.

Frames § Let us refine this notion of scheduling… § To keep the table small, we divide the time line into frames and make scheduling decisions only at frame boundaries. § Each job is executed as a procedure call that must fit within a frame. § Multiple jobs may be executed in a frame, but the table is only examined at frame boundaries (the number of “columns” in the table = the number of frames per hyperperiod). § In addition to making scheduling decisions, the scheduler also checks for various error conditions, like task overruns, at the beginning of each frame. § We let f denote the frame size.

Frame size constraints § We want frames to be sufficiently long so that every job can execute within a frame nonpreemptively. So, § f ³ max 1£i£n(ei). § To keep table small, f should divide H. Thus, for at least one task Ti, ëpi/fû - pi/f = 0. § Let F = H/f. (Note: F is an integer. ) Each interval of length H is called a major cycle. Each interval of length f is called a minor cycle. § There are F minor cycles per major cycle.

Frame size constraints § We want frames to be sufficiently long so that every job can execute within a frame nonpreemptively. So, § f ³ max 1£i£n(ei). § To keep table small, f should divide H. Thus, for at least one task Ti, ëpi/fû - pi/f = 0. § Let F = H/f. (Note: F is an integer. ) Each interval of length H is called a major cycle. Each interval of length f is called a minor cycle. § There are F minor cycles per major cycle.

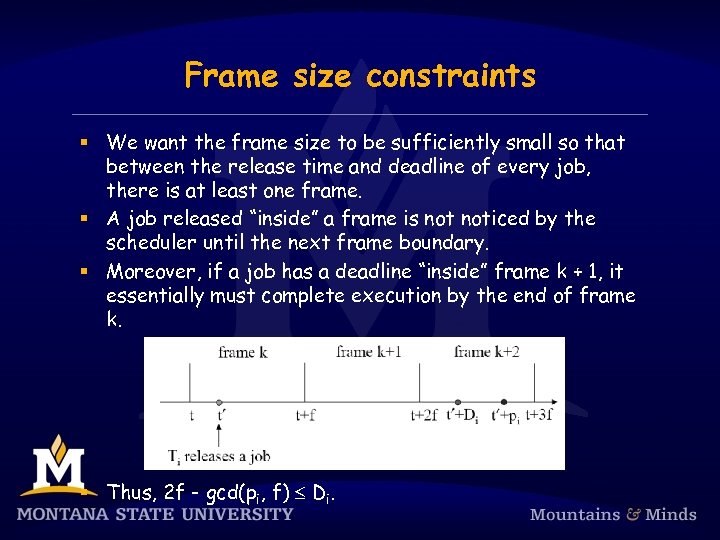

Frame size constraints § We want the frame size to be sufficiently small so that between the release time and deadline of every job, there is at least one frame. § A job released “inside” a frame is noticed by the scheduler until the next frame boundary. § Moreover, if a job has a deadline “inside” frame k + 1, it essentially must complete execution by the end of frame k. § Thus, 2 f - gcd(pi, f) £ Di.

Frame size constraints § We want the frame size to be sufficiently small so that between the release time and deadline of every job, there is at least one frame. § A job released “inside” a frame is noticed by the scheduler until the next frame boundary. § Moreover, if a job has a deadline “inside” frame k + 1, it essentially must complete execution by the end of frame k. § Thus, 2 f - gcd(pi, f) £ Di.

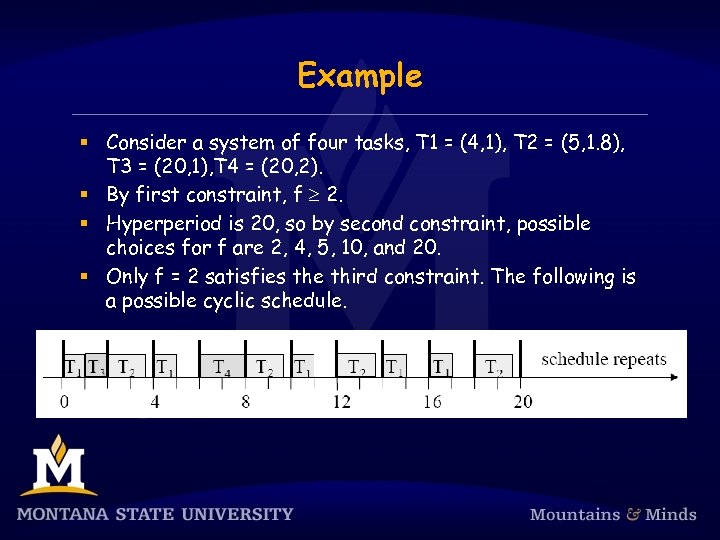

Example § Consider a system of four tasks, T 1 = (4, 1), T 2 = (5, 1. 8), T 3 = (20, 1), T 4 = (20, 2). § By first constraint, f ³ 2. § Hyperperiod is 20, so by second constraint, possible choices for f are 2, 4, 5, 10, and 20. § Only f = 2 satisfies the third constraint. The following is a possible cyclic schedule.

Example § Consider a system of four tasks, T 1 = (4, 1), T 2 = (5, 1. 8), T 3 = (20, 1), T 4 = (20, 2). § By first constraint, f ³ 2. § Hyperperiod is 20, so by second constraint, possible choices for f are 2, 4, 5, 10, and 20. § Only f = 2 satisfies the third constraint. The following is a possible cyclic schedule.

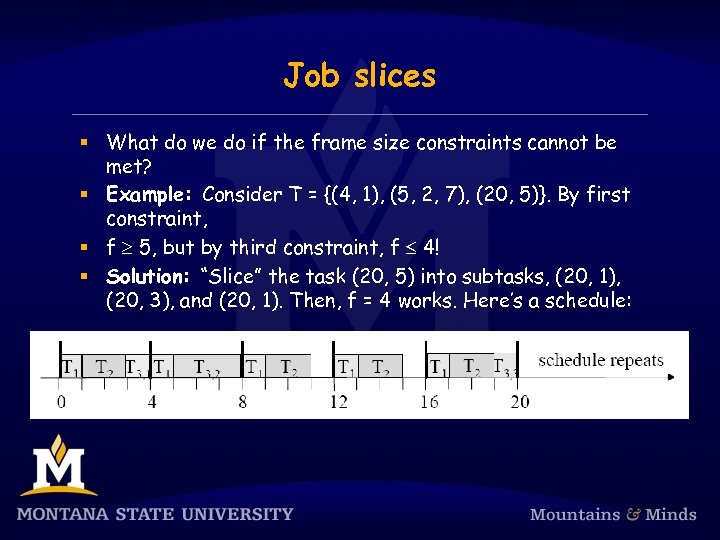

Job slices § What do we do if the frame size constraints cannot be met? § Example: Consider T = {(4, 1), (5, 2, 7), (20, 5)}. By first constraint, § f ³ 5, but by third constraint, f £ 4! § Solution: “Slice” the task (20, 5) into subtasks, (20, 1), (20, 3), and (20, 1). Then, f = 4 works. Here’s a schedule:

Job slices § What do we do if the frame size constraints cannot be met? § Example: Consider T = {(4, 1), (5, 2, 7), (20, 5)}. By first constraint, § f ³ 5, but by third constraint, f £ 4! § Solution: “Slice” the task (20, 5) into subtasks, (20, 1), (20, 3), and (20, 1). Then, f = 4 works. Here’s a schedule:

Summary of design decisions § Three design decisions: § choosing a frame size, § partitioning jobs into slices, and § placing slices in frames. § In general, these decisions cannot be made independently.

Summary of design decisions § Three design decisions: § choosing a frame size, § partitioning jobs into slices, and § placing slices in frames. § In general, these decisions cannot be made independently.

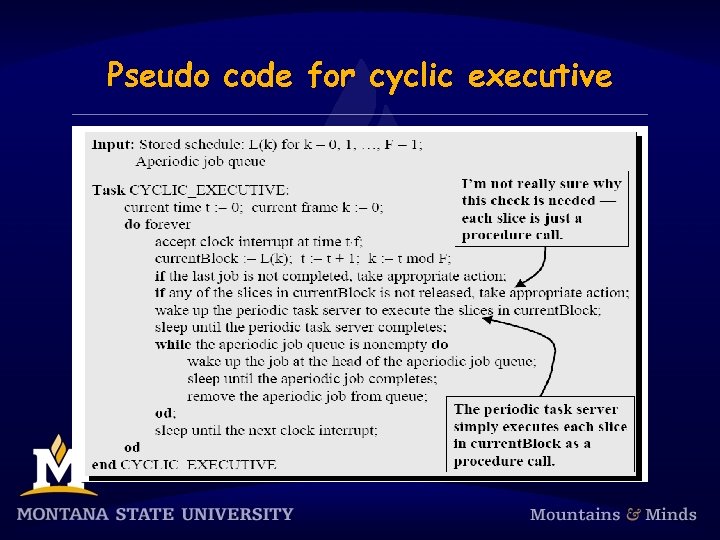

Pseudo code for cyclic executive

Pseudo code for cyclic executive

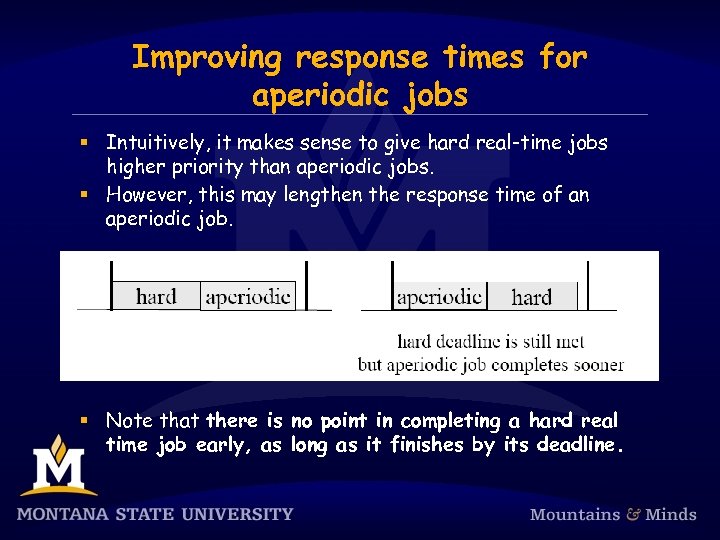

Improving response times for aperiodic jobs § Intuitively, it makes sense to give hard real-time jobs higher priority than aperiodic jobs. § However, this may lengthen the response time of an aperiodic job. § Note that there is no point in completing a hard real time job early, as long as it finishes by its deadline.

Improving response times for aperiodic jobs § Intuitively, it makes sense to give hard real-time jobs higher priority than aperiodic jobs. § However, this may lengthen the response time of an aperiodic job. § Note that there is no point in completing a hard real time job early, as long as it finishes by its deadline.

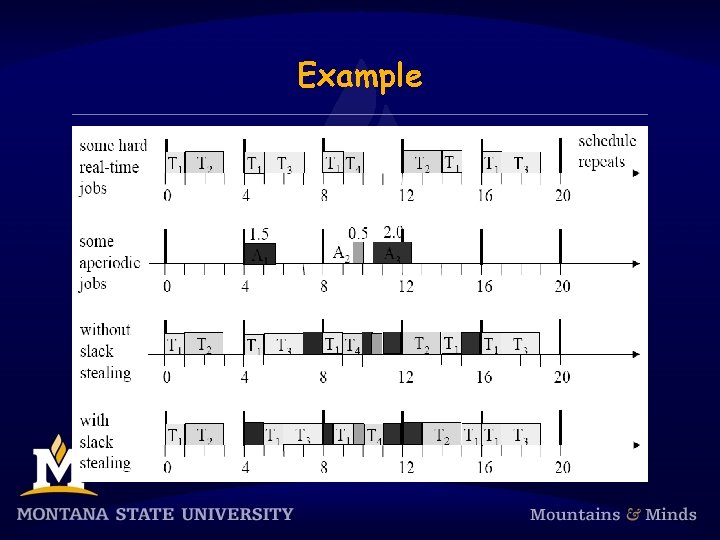

Slack stealing § Let the total amount of time allocated to all the slices scheduled in frame k be xk. § Definition: The slack available at the beginning of frame k is f - xk. § Change to scheduler: § If the aperiodic job queue is non-empty, let aperiodic jobs execute in each frame whenever there is nonzero slack.

Slack stealing § Let the total amount of time allocated to all the slices scheduled in frame k be xk. § Definition: The slack available at the beginning of frame k is f - xk. § Change to scheduler: § If the aperiodic job queue is non-empty, let aperiodic jobs execute in each frame whenever there is nonzero slack.

Example

Example

Implementing slack stealing § Use a pre-computed “initial slack” table. § Initial slack depends only on static quantities. § Use an interval timer to keep track of available slack. § Set the timer when an aperiodic job begins to run. If it goes off, must start executing periodic jobs. § Problem: Most OSs do not provide sub-millisecond granularity interval timers. § So, to use slack stealing, temporal parameters must be on the order of 100 s of msecs. or secs.

Implementing slack stealing § Use a pre-computed “initial slack” table. § Initial slack depends only on static quantities. § Use an interval timer to keep track of available slack. § Set the timer when an aperiodic job begins to run. If it goes off, must start executing periodic jobs. § Problem: Most OSs do not provide sub-millisecond granularity interval timers. § So, to use slack stealing, temporal parameters must be on the order of 100 s of msecs. or secs.

Scheduling sporiadic jobs Sporadic jobs arrive at arbitrary times. They have hard deadlines. Implies we cannot hope to schedule every sporadic job. When a sporadic job arrives, the scheduler performs an acceptance test to see if the job can be completed by its deadline. § We must ensure that a new sporadic job does not cause a previously-accepted sporadic job to miss its deadline. § We assume sporadic jobs are prioritized on an earliest deadline- first (EDF) basis. § §

Scheduling sporiadic jobs Sporadic jobs arrive at arbitrary times. They have hard deadlines. Implies we cannot hope to schedule every sporadic job. When a sporadic job arrives, the scheduler performs an acceptance test to see if the job can be completed by its deadline. § We must ensure that a new sporadic job does not cause a previously-accepted sporadic job to miss its deadline. § We assume sporadic jobs are prioritized on an earliest deadline- first (EDF) basis. § §

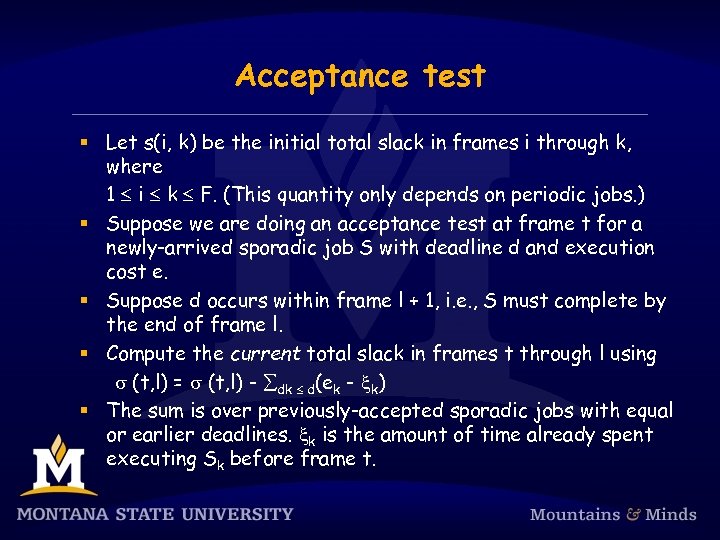

Acceptance test § Let s(i, k) be the initial total slack in frames i through k, where 1 £ i £ k £ F. (This quantity only depends on periodic jobs. ) § Suppose we are doing an acceptance test at frame t for a newly-arrived sporadic job S with deadline d and execution cost e. § Suppose d occurs within frame l + 1, i. e. , S must complete by the end of frame l. § Compute the current total slack in frames t through l using s (t, l) = s (t, l) - ådk £ d(ek - xk) § The sum is over previously-accepted sporadic jobs with equal or earlier deadlines. xk is the amount of time already spent executing Sk before frame t.

Acceptance test § Let s(i, k) be the initial total slack in frames i through k, where 1 £ i £ k £ F. (This quantity only depends on periodic jobs. ) § Suppose we are doing an acceptance test at frame t for a newly-arrived sporadic job S with deadline d and execution cost e. § Suppose d occurs within frame l + 1, i. e. , S must complete by the end of frame l. § Compute the current total slack in frames t through l using s (t, l) = s (t, l) - ådk £ d(ek - xk) § The sum is over previously-accepted sporadic jobs with equal or earlier deadlines. xk is the amount of time already spent executing Sk before frame t.

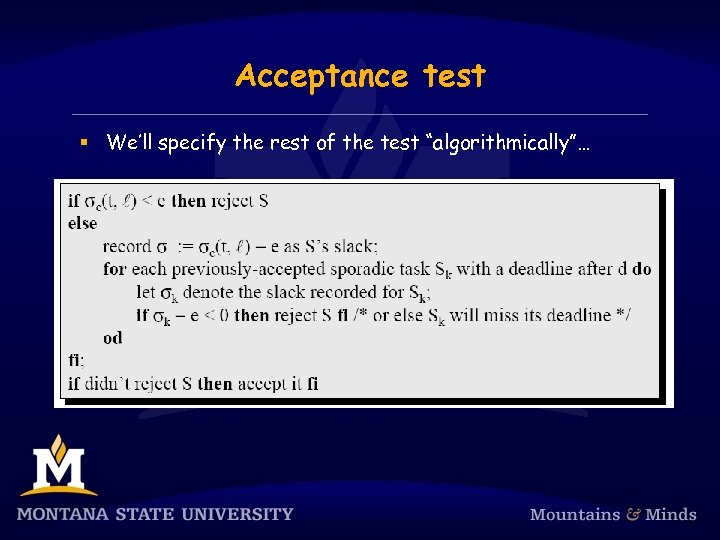

Acceptance test § We’ll specify the rest of the test “algorithmically”…

Acceptance test § We’ll specify the rest of the test “algorithmically”…

Acceptance test § To summarize, the scheduler must maintain the following data: § pre-computed initial slack table s(i, k); § xk values to use at the beginning of the current frame § the current slack sk of every accepted sporadic job Sk.

Acceptance test § To summarize, the scheduler must maintain the following data: § pre-computed initial slack table s(i, k); § xk values to use at the beginning of the current frame § the current slack sk of every accepted sporadic job Sk.

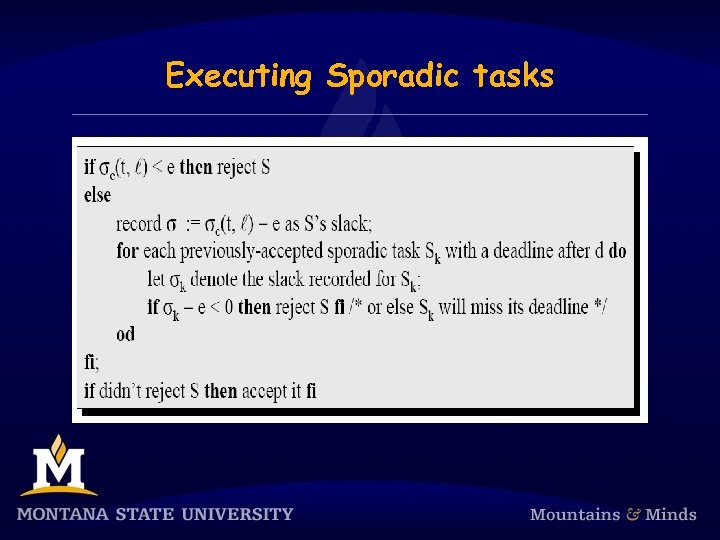

Executing Sporadic tasks

Executing Sporadic tasks

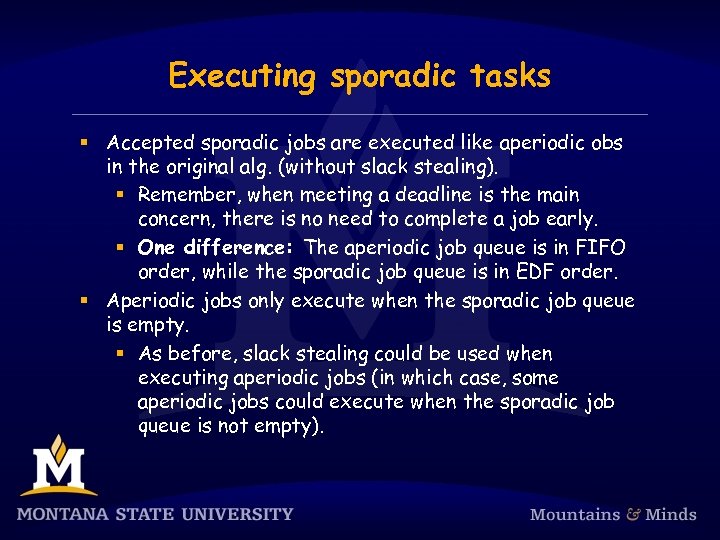

Executing sporadic tasks § Accepted sporadic jobs are executed like aperiodic obs in the original alg. (without slack stealing). § Remember, when meeting a deadline is the main concern, there is no need to complete a job early. § One difference: The aperiodic job queue is in FIFO order, while the sporadic job queue is in EDF order. § Aperiodic jobs only execute when the sporadic job queue is empty. § As before, slack stealing could be used when executing aperiodic jobs (in which case, some aperiodic jobs could execute when the sporadic job queue is not empty).

Executing sporadic tasks § Accepted sporadic jobs are executed like aperiodic obs in the original alg. (without slack stealing). § Remember, when meeting a deadline is the main concern, there is no need to complete a job early. § One difference: The aperiodic job queue is in FIFO order, while the sporadic job queue is in EDF order. § Aperiodic jobs only execute when the sporadic job queue is empty. § As before, slack stealing could be used when executing aperiodic jobs (in which case, some aperiodic jobs could execute when the sporadic job queue is not empty).

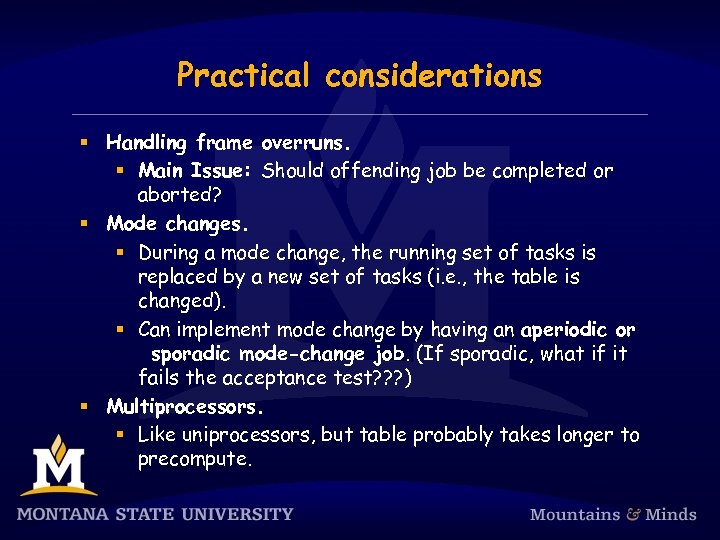

Practical considerations § Handling frame overruns. § Main Issue: Should offending job be completed or aborted? § Mode changes. § During a mode change, the running set of tasks is replaced by a new set of tasks (i. e. , the table is changed). § Can implement mode change by having an aperiodic or sporadic mode-change job. (If sporadic, what if it fails the acceptance test? ? ? ) § Multiprocessors. § Like uniprocessors, but table probably takes longer to precompute.

Practical considerations § Handling frame overruns. § Main Issue: Should offending job be completed or aborted? § Mode changes. § During a mode change, the running set of tasks is replaced by a new set of tasks (i. e. , the table is changed). § Can implement mode change by having an aperiodic or sporadic mode-change job. (If sporadic, what if it fails the acceptance test? ? ? ) § Multiprocessors. § Like uniprocessors, but table probably takes longer to precompute.

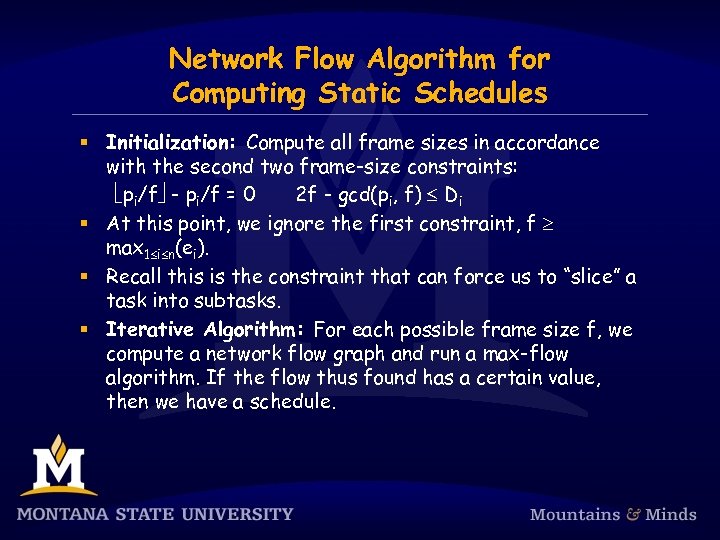

Network Flow Algorithm for Computing Static Schedules § Initialization: Compute all frame sizes in accordance with the second two frame-size constraints: ëpi/fû - pi/f = 0 2 f - gcd(pi, f) £ Di § At this point, we ignore the first constraint, f ³ max 1£i£n(ei). § Recall this is the constraint that can force us to “slice” a task into subtasks. § Iterative Algorithm: For each possible frame size f, we compute a network flow graph and run a max-flow algorithm. If the flow thus found has a certain value, then we have a schedule.

Network Flow Algorithm for Computing Static Schedules § Initialization: Compute all frame sizes in accordance with the second two frame-size constraints: ëpi/fû - pi/f = 0 2 f - gcd(pi, f) £ Di § At this point, we ignore the first constraint, f ³ max 1£i£n(ei). § Recall this is the constraint that can force us to “slice” a task into subtasks. § Iterative Algorithm: For each possible frame size f, we compute a network flow graph and run a max-flow algorithm. If the flow thus found has a certain value, then we have a schedule.

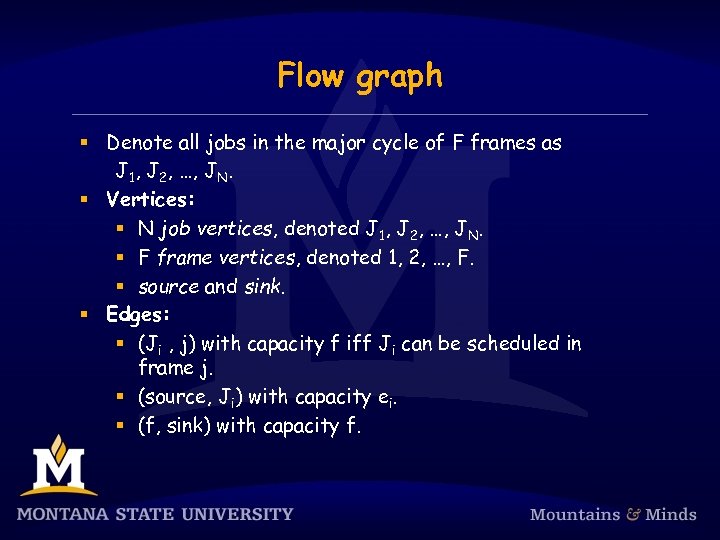

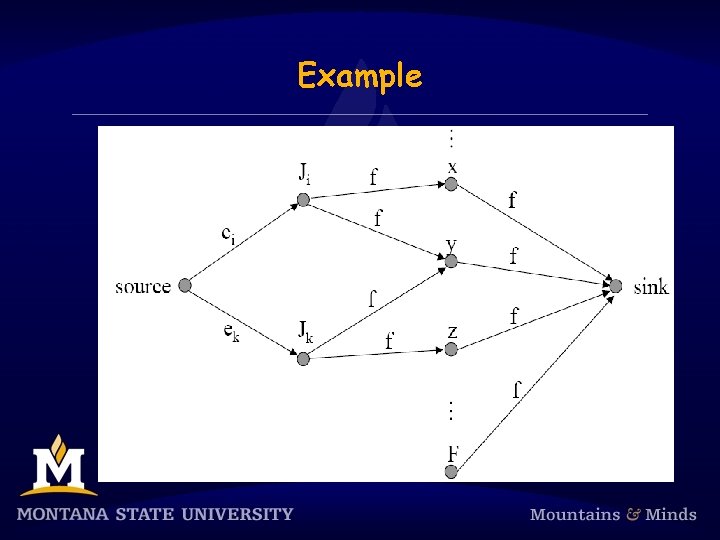

Flow graph § Denote all jobs in the major cycle of F frames as J 1, J 2, …, JN. § Vertices: § N job vertices, denoted J 1, J 2, …, JN. § F frame vertices, denoted 1, 2, …, F. § source and sink. § Edges: § (Ji , j) with capacity f iff Ji can be scheduled in frame j. § (source, Ji) with capacity ei. § (f, sink) with capacity f.

Flow graph § Denote all jobs in the major cycle of F frames as J 1, J 2, …, JN. § Vertices: § N job vertices, denoted J 1, J 2, …, JN. § F frame vertices, denoted 1, 2, …, F. § source and sink. § Edges: § (Ji , j) with capacity f iff Ji can be scheduled in frame j. § (source, Ji) with capacity ei. § (f, sink) with capacity f.

Example

Example

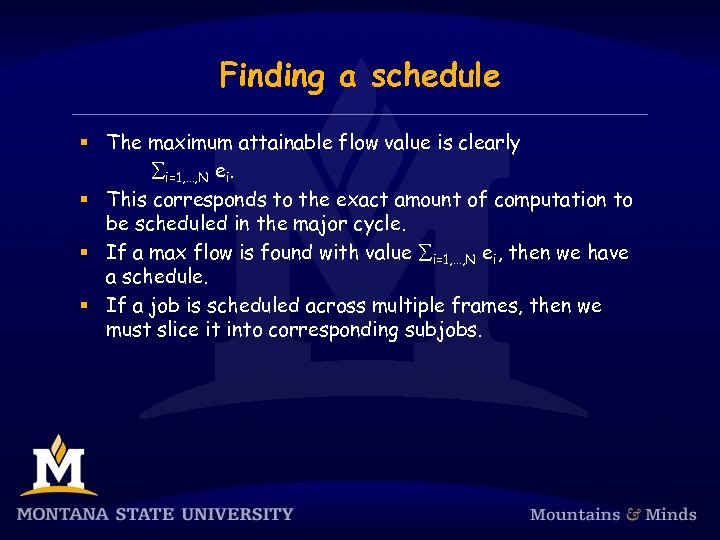

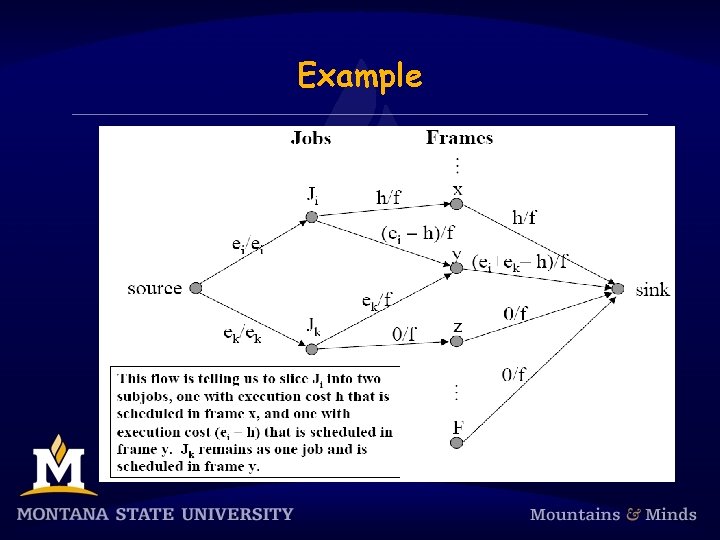

Finding a schedule § The maximum attainable flow value is clearly åi=1, …, N ei. § This corresponds to the exact amount of computation to be scheduled in the major cycle. § If a max flow is found with value åi=1, …, N ei, then we have a schedule. § If a job is scheduled across multiple frames, then we must slice it into corresponding subjobs.

Finding a schedule § The maximum attainable flow value is clearly åi=1, …, N ei. § This corresponds to the exact amount of computation to be scheduled in the major cycle. § If a max flow is found with value åi=1, …, N ei, then we have a schedule. § If a job is scheduled across multiple frames, then we must slice it into corresponding subjobs.

Example

Example

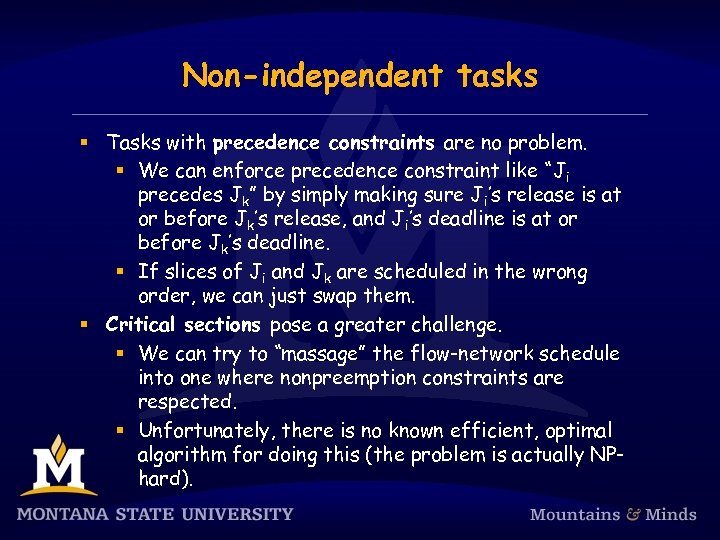

Non-independent tasks § Tasks with precedence constraints are no problem. § We can enforce precedence constraint like “Ji precedes Jk” by simply making sure Ji’s release is at or before Jk’s release, and Ji’s deadline is at or before Jk’s deadline. § If slices of Ji and Jk are scheduled in the wrong order, we can just swap them. § Critical sections pose a greater challenge. § We can try to “massage” the flow-network schedule into one where nonpreemption constraints are respected. § Unfortunately, there is no known efficient, optimal algorithm for doing this (the problem is actually NPhard).

Non-independent tasks § Tasks with precedence constraints are no problem. § We can enforce precedence constraint like “Ji precedes Jk” by simply making sure Ji’s release is at or before Jk’s release, and Ji’s deadline is at or before Jk’s deadline. § If slices of Ji and Jk are scheduled in the wrong order, we can just swap them. § Critical sections pose a greater challenge. § We can try to “massage” the flow-network schedule into one where nonpreemption constraints are respected. § Unfortunately, there is no known efficient, optimal algorithm for doing this (the problem is actually NPhard).

Pros and Cons of Cyclic Executives § Main Advantage: CEs are very simple - you just need a table. § For example, additional mechanisms for concurrency control and synchronization are not needed. In fact, there’s really no notion of a “process” here – just procedure calls. § Can validate, test, and certify with very high confidence. § Certain anomalies will not occur. § For these reasons, cyclic executives are the predominant approach in many safety-critical applications (like airplanes).

Pros and Cons of Cyclic Executives § Main Advantage: CEs are very simple - you just need a table. § For example, additional mechanisms for concurrency control and synchronization are not needed. In fact, there’s really no notion of a “process” here – just procedure calls. § Can validate, test, and certify with very high confidence. § Certain anomalies will not occur. § For these reasons, cyclic executives are the predominant approach in many safety-critical applications (like airplanes).

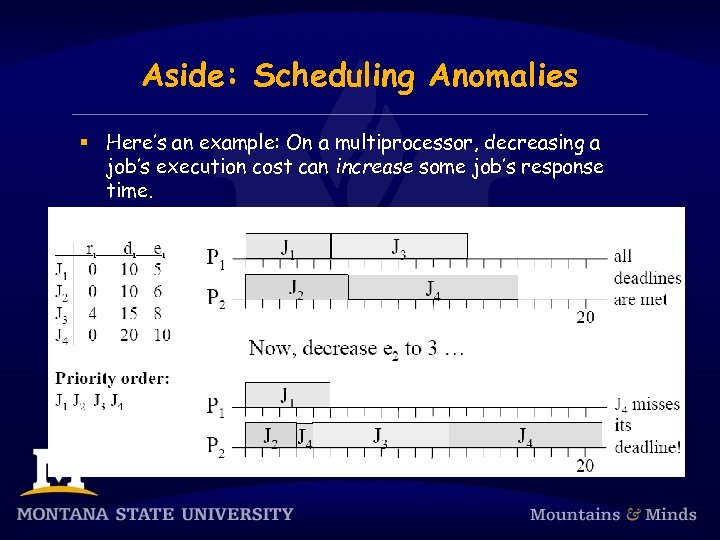

Aside: Scheduling Anomalies § Here’s an example: On a multiprocessor, decreasing a job’s execution cost can increase some job’s response time. § Example: Suppose we have one job queue, preemption, but no migration.

Aside: Scheduling Anomalies § Here’s an example: On a multiprocessor, decreasing a job’s execution cost can increase some job’s response time. § Example: Suppose we have one job queue, preemption, but no migration.

Disadvantages § Disadvantages of cyclic executives: § Very brittle: Any change, no matter how trivial, requires that a new table be computed! § Release times of all jobs must be fixed, i. e. , “real-world” sporadic tasks are difficult to support. § Temporal parameters essentially must be multiples of f. § F could be huge! § All combinations of periodic tasks that may execute together must a priori be analyzed. § From a software engineering standpoint, “slicing” one procedure into several could be error-prone.

Disadvantages § Disadvantages of cyclic executives: § Very brittle: Any change, no matter how trivial, requires that a new table be computed! § Release times of all jobs must be fixed, i. e. , “real-world” sporadic tasks are difficult to support. § Temporal parameters essentially must be multiples of f. § F could be huge! § All combinations of periodic tasks that may execute together must a priori be analyzed. § From a software engineering standpoint, “slicing” one procedure into several could be error-prone.

Dynamic-priority scheduling § Let us consider a priority-based dynamic scheduling approach. § Each job is assigned a priority, and the highestpriority job executes at any time. § Under dynamic-priority scheduling, different jobs of a task may be assigned different priorities. § Can have the following: job Ji, k of task Ti has higher priority than job Jj, m of task Tj, but job Ji, l of Ti has lower priority than job Jj, n of Tj.

Dynamic-priority scheduling § Let us consider a priority-based dynamic scheduling approach. § Each job is assigned a priority, and the highestpriority job executes at any time. § Under dynamic-priority scheduling, different jobs of a task may be assigned different priorities. § Can have the following: job Ji, k of task Ti has higher priority than job Jj, m of task Tj, but job Ji, l of Ti has lower priority than job Jj, n of Tj.

Outline § We consider both earliest-deadline-first (EDF) and least-laxity-first (LLF) scheduling. § Outline: § Optimality of EDF and LLF § Utilization-based schedulability test for EDF

Outline § We consider both earliest-deadline-first (EDF) and least-laxity-first (LLF) scheduling. § Outline: § Optimality of EDF and LLF § Utilization-based schedulability test for EDF

![Optimality of EDF § Theorem: [Liu and Layland] When preemption is allowed and jobs Optimality of EDF § Theorem: [Liu and Layland] When preemption is allowed and jobs](https://present5.com/presentation/fce80b2b48b6dbfdcfa949fd3aca47e4/image-66.jpg) Optimality of EDF § Theorem: [Liu and Layland] When preemption is allowed and jobs do not contend for resources, the EDF algorithm can produce a feasible schedule of a set J of independent jobs with arbitrary release times and deadlines on a processor if and only if J has feasible schedules. § Notes: § Applies even if tasks are not periodic. § If periodic, a task’s relative deadline can be less than its period, equal to its period, or greater than its period.

Optimality of EDF § Theorem: [Liu and Layland] When preemption is allowed and jobs do not contend for resources, the EDF algorithm can produce a feasible schedule of a set J of independent jobs with arbitrary release times and deadlines on a processor if and only if J has feasible schedules. § Notes: § Applies even if tasks are not periodic. § If periodic, a task’s relative deadline can be less than its period, equal to its period, or greater than its period.

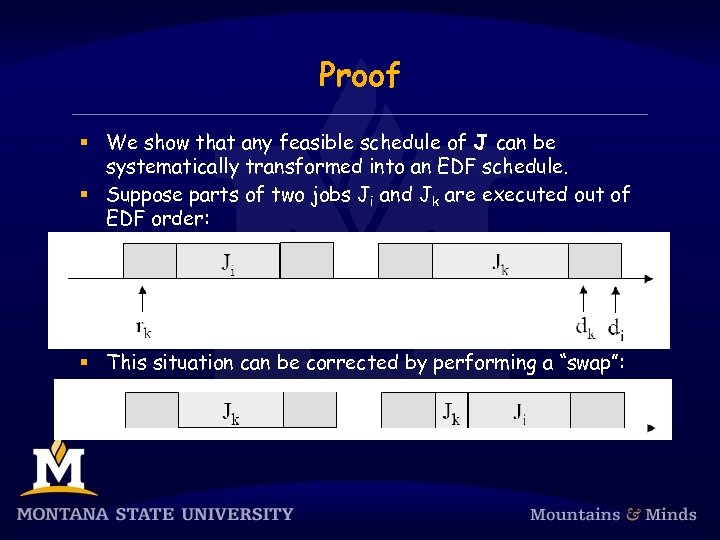

Proof § We show that any feasible schedule of J can be systematically transformed into an EDF schedule. § Suppose parts of two jobs Ji and Jk are executed out of EDF order: § This situation can be corrected by performing a “swap”:

Proof § We show that any feasible schedule of J can be systematically transformed into an EDF schedule. § Suppose parts of two jobs Ji and Jk are executed out of EDF order: § This situation can be corrected by performing a “swap”:

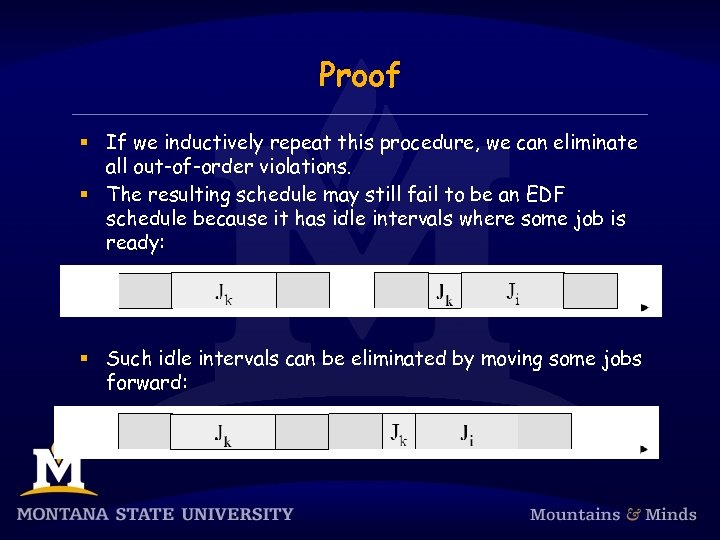

Proof § If we inductively repeat this procedure, we can eliminate all out-of-order violations. § The resulting schedule may still fail to be an EDF schedule because it has idle intervals where some job is ready: § Such idle intervals can be eliminated by moving some jobs forward:

Proof § If we inductively repeat this procedure, we can eliminate all out-of-order violations. § The resulting schedule may still fail to be an EDF schedule because it has idle intervals where some job is ready: § Such idle intervals can be eliminated by moving some jobs forward:

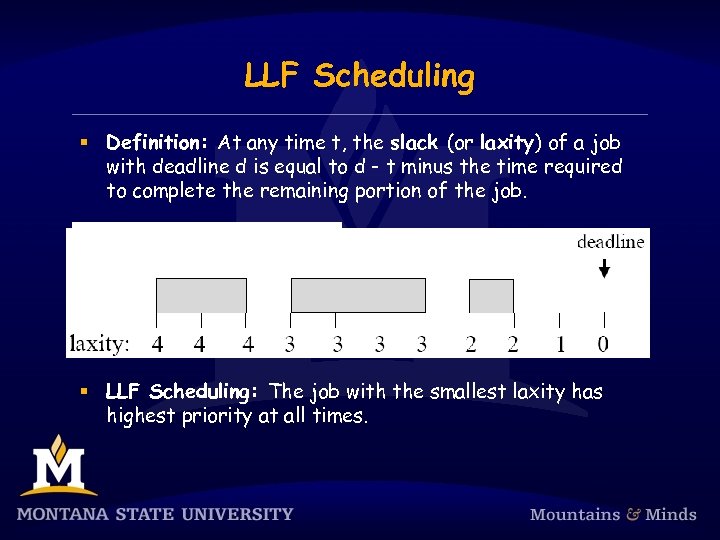

LLF Scheduling § Definition: At any time t, the slack (or laxity) of a job with deadline d is equal to d - t minus the time required to complete the remaining portion of the job. § LLF Scheduling: The job with the smallest laxity has highest priority at all times.

LLF Scheduling § Definition: At any time t, the slack (or laxity) of a job with deadline d is equal to d - t minus the time required to complete the remaining portion of the job. § LLF Scheduling: The job with the smallest laxity has highest priority at all times.

Optimality of LLF § Theorem: When preemption is allowed and jobs do not contend for resources, the LLF algorithm can produce a feasible schedule of a set J of independent jobs with arbitrary release times and deadlines on a processor if and only if J has feasible schedules. § The proof is similar to that for EDF.

Optimality of LLF § Theorem: When preemption is allowed and jobs do not contend for resources, the LLF algorithm can produce a feasible schedule of a set J of independent jobs with arbitrary release times and deadlines on a processor if and only if J has feasible schedules. § The proof is similar to that for EDF.