Re_defining_linguistic_diversity_what_i.pptx

- Количество слайдов: 35

(RE)DEFINING LINGUISTIC DIVERSITY WHAT IS BEING PROTECTED BY LANGUAGE POLICY AND PLANNING? Dr. Dave Sayers Senior Lecturer, Sheffield Hallam University dave. sayers@cantab. net http: //shu. academia. edu/Dave. Sayers

• Look at ‘linguistic diversity’ from: • variationist sociolinguistics – where it is described, but not mentioned by name (case study: British English); • language policy – where it is frequently mentioned by name, but not described (case study: European Charter). • language planning – where it is more or less absent, replaced by a concern with individual languages. –Case studies of two language revivals, Cornish and Welsh. • Evaluate claims to be ‘protecting linguistic diversity’ in language policy, building on the likes of Freeland & Patrick (2004), Wright (2007), Strubell (2007).

What is linguistic diversity? • Unqualified term, not some diversity, or these types of diversity. • Must mean all differences in human language, across space and time.

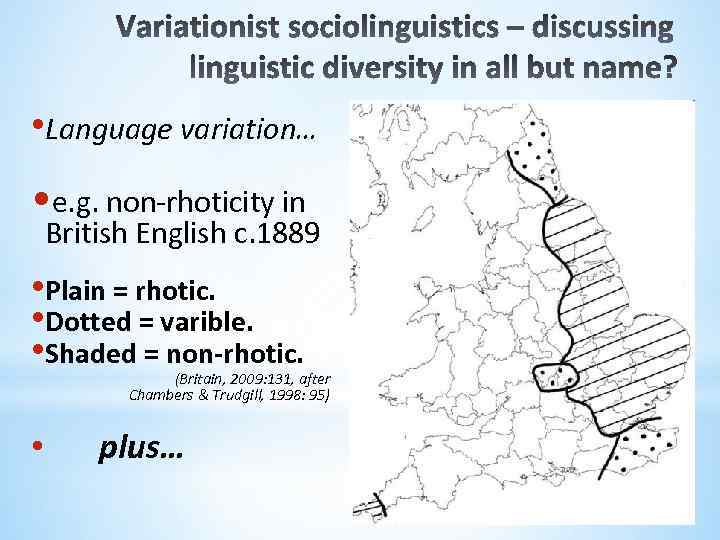

• Language variation… • e. g. non-rhoticity in British English c. 1889 • Plain = rhotic. • Dotted = varible. • Shaded = non-rhotic. (Britain, 2009: 131, after Chambers & Trudgill, 1998: 95) • plus…

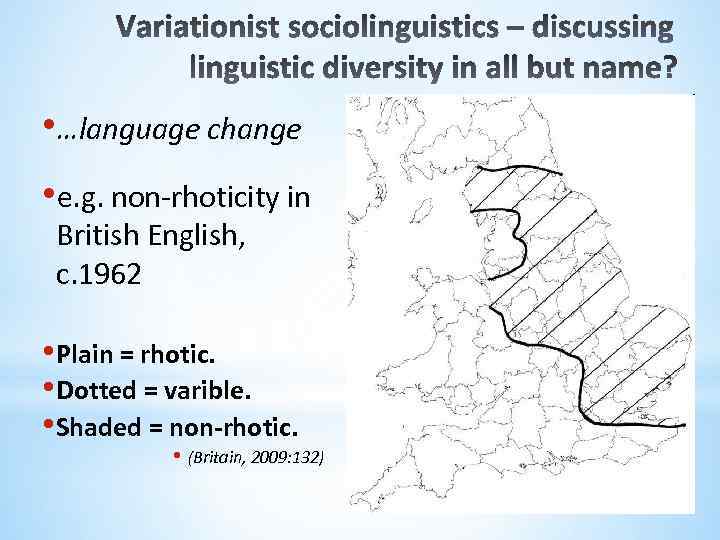

• …language change • e. g. non-rhoticity in British English, c. 1962 • Plain = rhotic. • Dotted = varible. • Shaded = non-rhotic. • (Britain, 2009: 132)

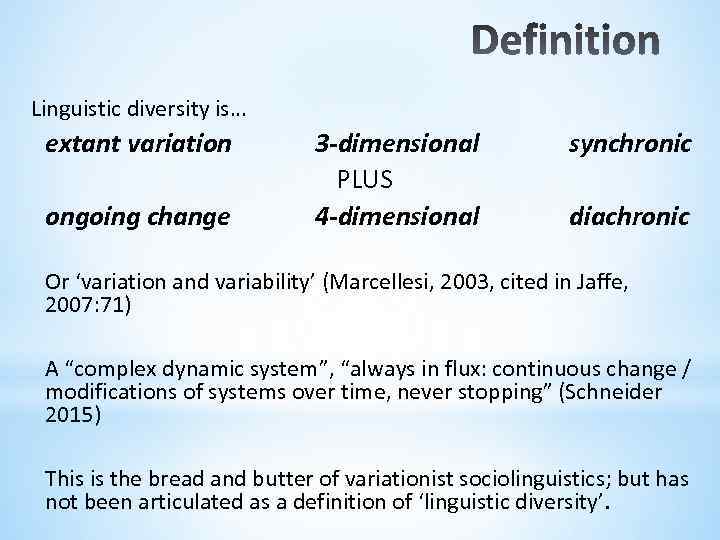

Linguistic diversity is… extant variation ongoing change 3 -dimensional PLUS 4 -dimensional synchronic diachronic Or ‘variation and variability’ (Marcellesi, 2003, cited in Jaffe, 2007: 71) A “complex dynamic system”, “always in flux: continuous change / modifications of systems over time, never stopping” (Schneider 2015) This is the bread and butter of variationist sociolinguistics; but has not been articulated as a definition of ‘linguistic diversity’.

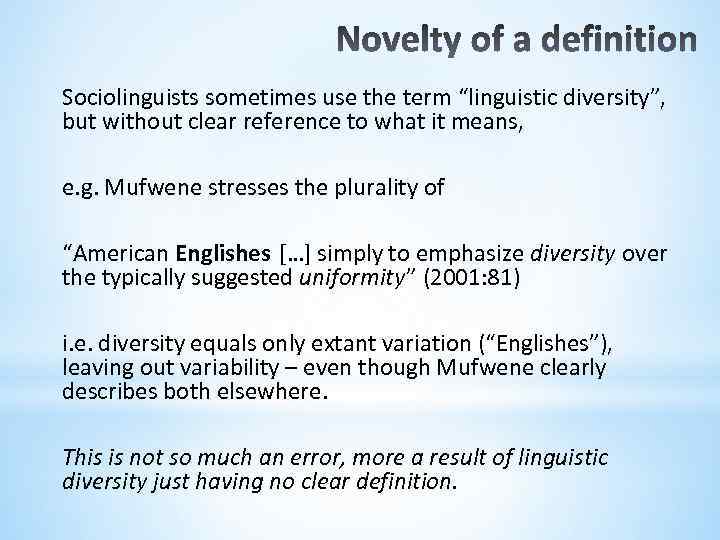

Sociolinguists sometimes use the term “linguistic diversity”, but without clear reference to what it means, e. g. Mufwene stresses the plurality of “American Englishes […] simply to emphasize diversity over the typically suggested uniformity” (2001: 81) i. e. diversity equals only extant variation (“Englishes”), leaving out variability – even though Mufwene clearly describes both elsewhere. This is not so much an error, more a result of linguistic diversity just having no clear definition.

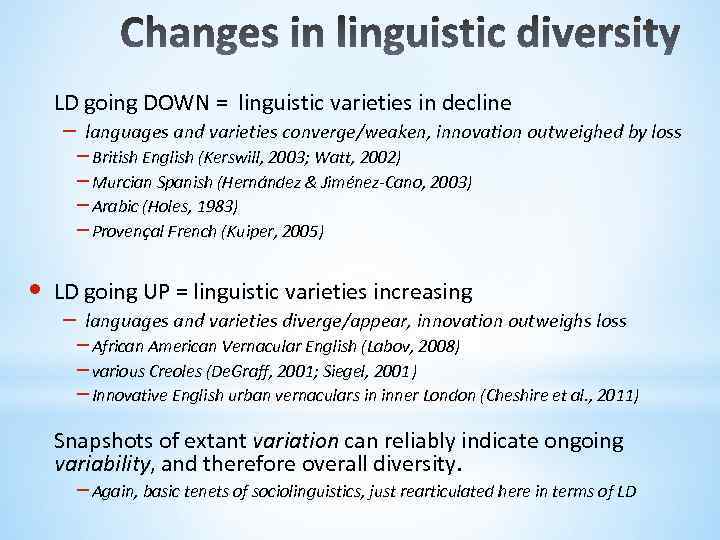

LD going DOWN = linguistic varieties in decline – • languages and varieties converge/weaken, innovation outweighed by loss – British English (Kerswill, 2003; Watt, 2002) – Murcian Spanish (Hernández & Jiménez-Cano, 2003) – Arabic (Holes, 1983) – Provençal French (Kuiper, 2005) LD going UP = linguistic varieties increasing – languages and varieties diverge/appear, innovation outweighs loss – African American Vernacular English (Labov, 2008) – various Creoles (De. Graff, 2001; Siegel, 2001) – Innovative English urban vernaculars in inner London (Cheshire et al. , 2011) Snapshots of extant variation can reliably indicate ongoing variability, and therefore overall diversity. – Again, basic tenets of sociolinguistics, just rearticulated here in terms of LD

• Language policy is founded on “the desirability of linguistic diversity” (Spolsky, 2004: ix) • “the preservation of linguistic diversity is a central, if not overriding, goal for language policy” (Ferguson, 2006: 7) • See also e. g. : • Romaine, S. (2006). ‘Planning for the survival of linguistic diversity’. Language Policy, 5(2): 441 -473. • Dominicis, A. D. , (2008). Undescribed and Endangered Languages: the Preservation of Linguistic Diversity, Newcastleupon-Tyne: Cambridge Scholars.

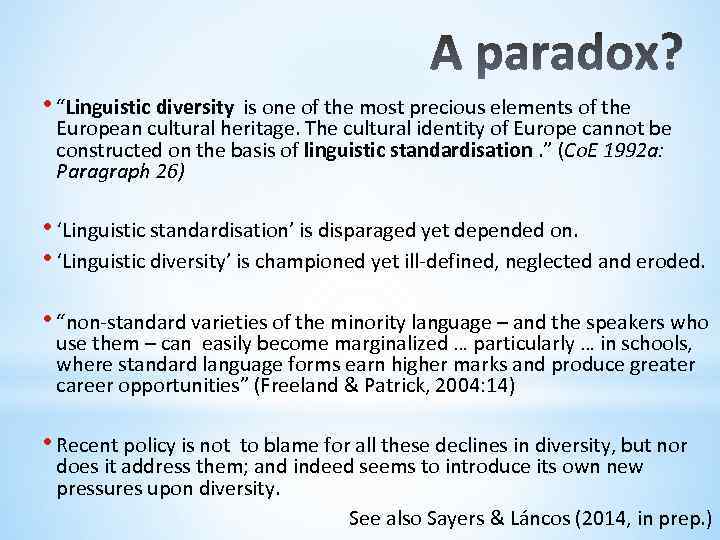

• European Charter for Regional & Minority Languages begins… • “Linguistic diversity is one of the most precious elements of the European cultural heritage. The cultural identity of Europe cannot be constructed on the basis of linguistic standardisation. On the contrary, the protection and strengthening of its traditional regional and minority languages represents a contribution to the building of Europe, which, according to the ideals of the members of the Council of Europe, can be founded only on pluralist principles. ” • Paragraph 26, Co. E (1992 a) – preamble

• “Probably the most linguistically diverse places in the world are to be found in the Pacific”, e. g. Papua New Guinea with “ 1100 languages” (Austin, 2007: 82). • “[A part of Nigeria has] arguably the greatest linguistic diversity, with between 250 and 400 languages” (Grenoble & Whaley, 2006: 37) • “India, Tanzania and Malaysia […] are among the world’s most linguistically diverse countries, with 415, 128 and 140 languages respectively” (Romaine, 2006: 463)

• Linguistic diversity • Definition • Series of languages • Linguistic diversity is not so much defined as a series of languages. It is not really defined at all. The term is used, and placed next to this description of a series of languages…

![• “[T]hese diverse languages” are “marginalised and under pressure from the larger [languages]”, • “[T]hese diverse languages” are “marginalised and under pressure from the larger [languages]”,](https://present5.com/presentation/-103116360_437592592/image-13.jpg)

• “[T]hese diverse languages” are “marginalised and under pressure from the larger [languages]”, resulting in the “loss of language diversity” (Austin, 2007: 82 -3) • Protection of “cultural and linguistic diversity” means opposition to “stigmatisation and marginalisation […] of minority languages” (May, 2000: 379 -80) • Language death – the loss of whole languages – equals “the loss of linguistic diversity” (Grenoble & Whaley, 2006: 2).

Protection of diversity and promotion of languages routinely conflated as complementary goals: “The maintenance of language diversity and the promotion of language learning and multilingualism are seen as essential elements for the improvement of communication and for the reduction of intercultural misunderstanding. ” (Extra & Yagmur, 2005: 37, emphases added) “Promoting linguistic diversity means actively encouraging the teaching and learning of the widest possible range of languages …. ” (European Commission, 2003: 9, emphases added) (See also e. g. Mc. Pake et al. , 2004; Balboni, 2004; Ricento, 2005; García et al. , 2006; De Schutter, 2007; Loos, 2007; De Dominicis, 2008. )

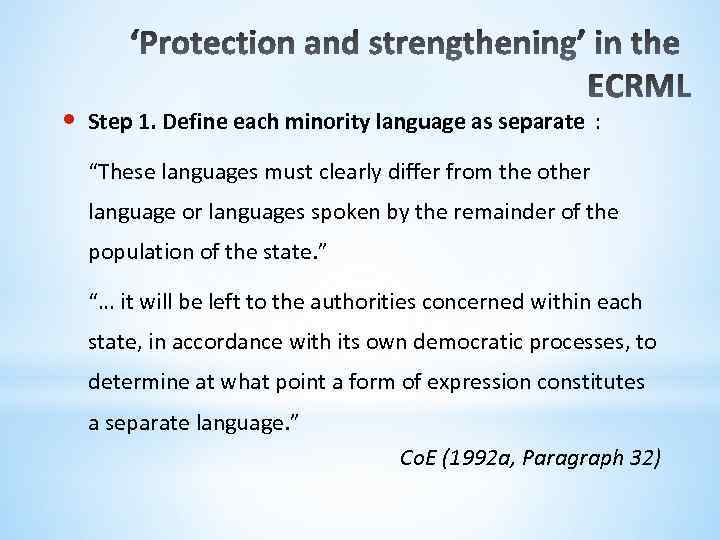

• Step 1. Define each minority language as separate : “These languages must clearly differ from the other language or languages spoken by the remainder of the population of the state. ” “… it will be left to the authorities concerned within each state, in accordance with its own democratic processes, to determine at what point a form of expression constitutes a separate language. ” Co. E (1992 a, Paragraph 32)

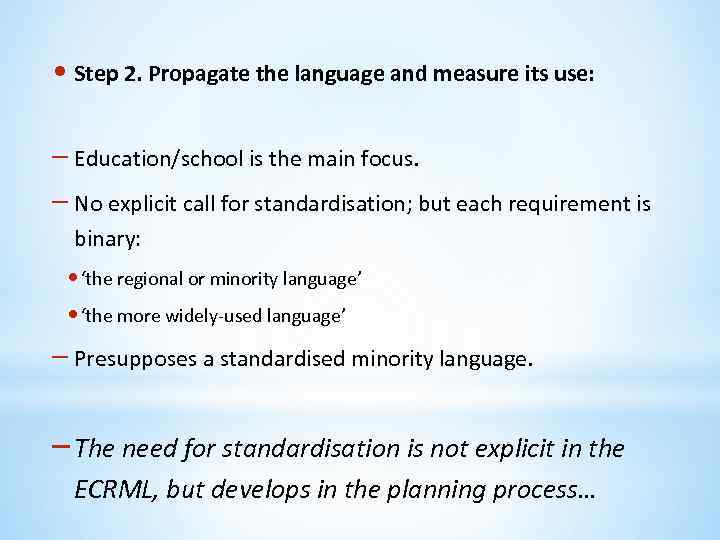

• Step 2. Propagate the language and measure its use: – Education/school is the main focus. – No explicit call for standardisation; but each requirement is binary: • ‘the regional or minority language’ • ‘the more widely-used language’ – Presupposes a standardised minority language. – The need for standardisation is not explicit in the ECRML, but develops in the planning process…

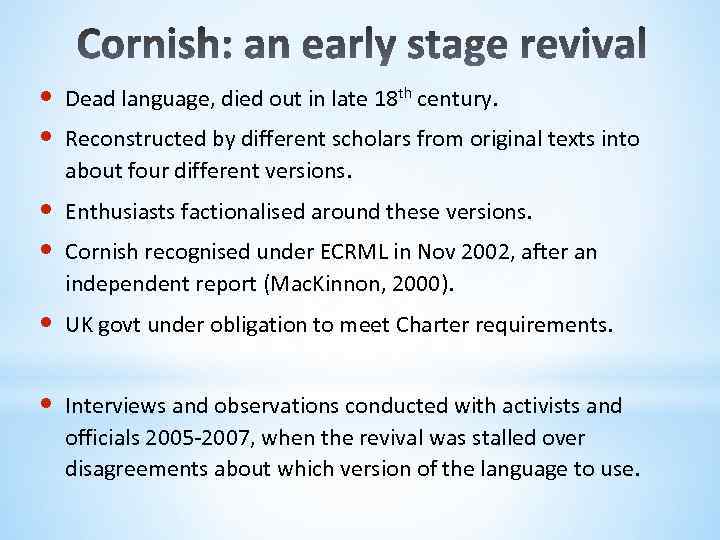

• • Dead language, died out in late 18 th century. • • Enthusiasts factionalised around these versions. • UK govt under obligation to meet Charter requirements. • Interviews and observations conducted with activists and officials 2005 -2007, when the revival was stalled over disagreements about which version of the language to use. Reconstructed by different scholars from original texts into about four different versions. Cornish recognised under ECRML in Nov 2002, after an independent report (Mac. Kinnon, 2000).

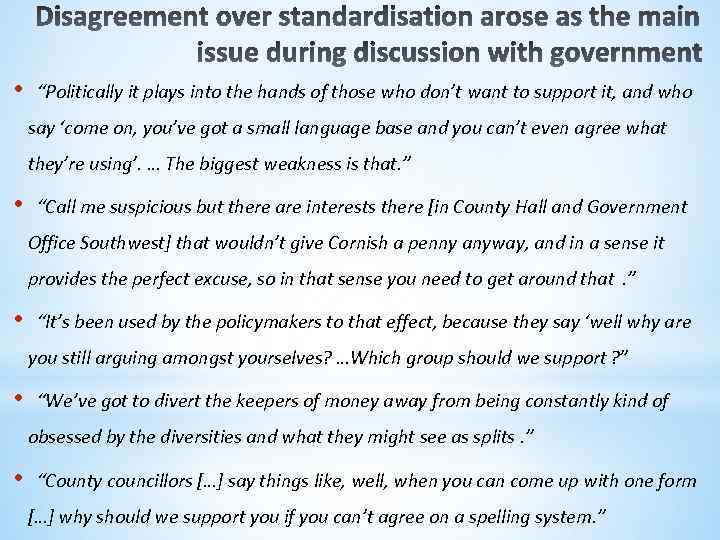

• “Politically it plays into the hands of those who don’t want to support it, and who say ‘come on, you’ve got a small language base and you can’t even agree what they’re using’. … The biggest weakness is that. ” • “Call me suspicious but there are interests there [in County Hall and Government Office Southwest] that wouldn’t give Cornish a penny anyway, and in a sense it provides the perfect excuse, so in that sense you need to get around that. ” • “It’s been used by the policymakers to that effect, because they say ‘well why are you still arguing amongst yourselves? …Which group should we support ? ” • “We’ve got to divert the keepers of money away from being constantly kind of obsessed by the diversities and what they might see as splits. ” • “County councillors […] say things like, well, when you can come up with one form […] why should we support you if you can’t agree on a spelling system. ”

![• “Obviously we’ll need one [form of Cornish], we need to try and • “Obviously we’ll need one [form of Cornish], we need to try and](https://present5.com/presentation/-103116360_437592592/image-19.jpg)

• “Obviously we’ll need one [form of Cornish], we need to try and work together towards … what Cornish gets used in schools ” • “It does need to be done in mostly one form. The differences are used by people who have an anti-Cornish language slant like [critical education figure] … to say oh well we can’t have any Cornish in schools because they can’t even decide what system. ” • “I think there is going to have to be some compromise [in education] in order to get the authorities […] engaged, because you have got to contend with the LEA, you’ve got to contend with Df. ES […] because if a child moves from here to there, they want them to be able to work in the same system. ” • “If you’re actually talking about putting resources into producing materials and in training teachers … how are you going to produce it in three or four forms? That’s the problem. ”

• “You could say well it’s up to each authority … to say what they want to do [in terms of selecting a variety of Cornish] but they’re not going to. […] Essentially it comes down to what the County Council does – because that’s most official documentation. […] What we have to do now is to ensure that everything is done to a standard, and that we look at securing the younger language base. ” • “It’s difficult, if it’s going to be something that’s across the whole of Cornwall with national curricula and everything else it’ll have to be more standardised. … People have to … weigh up what’s more advantageous… is it more advantageous for some sort of Cornish to be taught in schools … or to carry on arguing and never get it in schools. ”

• This requirement materialised in the planning process, not stipulated explicitly in the policy. • A standard allows: – – – • Maximally efficient production of resources. Measurement of progress as learning outcomes. Movement of pupils between schools. This was more to do with quite mundane practicalities than any particular ideology.

![• “A Commission of international experts [including Joshua Fishman] has been assembled to • “A Commission of international experts [including Joshua Fishman] has been assembled to](https://present5.com/presentation/-103116360_437592592/image-22.jpg)

• “A Commission of international experts [including Joshua Fishman] has been assembled to assist us in the work towards establishing a single written form and with language planning generally. ” • (Cornish Language Partnership newsletter, Jan 2007) • New standard finally agreed in 2008. • Currently being rolled out in state education through new textbooks and other standardised materials.

• The versions of Cornish do not represent diversity in the sense of natural variation or variability, but nor are these things encouraged. • The propagation and reproduction of a single standard form is the main priority. • The potential for diversity seems stifled in this revival… • But then, ‘diversity’ is no longer in the discourse; the language, ‘Cornish’, is the priority. For more, see Sayers (2012); Renkó-Michelsén (2013, in prep. ); Sayers & Renkó-Michelsén (forthcoming).

• Unlike Cornish, Welsh declined but did not die out. • Welsh Language Act (1967) • Welsh recognised under the ECRML in 2000. • Since the 1980 s, a steady and sustained increase in Welsh medium education. • 2% increase in self-reportage of Welsh proficiency between 1991 and 2001 census (ONS, 2004; Farrell et al. 1997; H. Jones 2005), though declining 1% 2001 -2011 (ONS 2011) • But what of diversity?

• Success defined almost exclusively by speaker numbers, and attributed to education (ONS, 2004; C. H. Williams, 2008: 254) Aitchison & Carter (2000: 141). “Demography – the numbers and distribution of people reporting themselves to have ability in Welsh, based on census data – is the usual focus of debate on the current ‘health’ of the language. ” (Coupland et al. , 2005: 2)

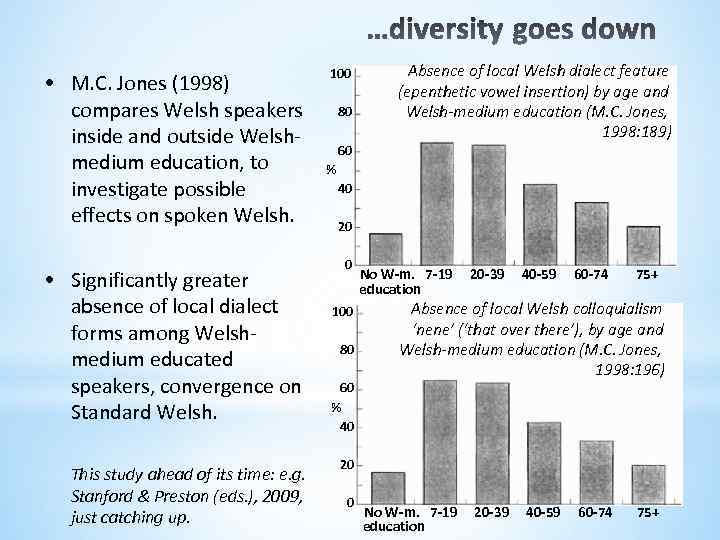

• M. C. Jones (1998) compares Welsh speakers inside and outside Welshmedium education, to investigate possible effects on spoken Welsh. • Significantly greater absence of local dialect forms among Welshmedium educated speakers, convergence on Standard Welsh. This study ahead of its time: e. g. Stanford & Preston (eds. ), 2009, just catching up. 100 80 60 Absence of local Welsh dialect feature (epenthetic vowel insertion) by age and Welsh-medium education (M. C. Jones, 1998: 189) % 40 20 0 100 80 60 % 40 No W-m. 7 -19 education 20 -39 40 -59 60 -74 75+ Absence of local Welsh colloquialism ‘nene’ (‘that over there’), by age and Welsh-medium education (M. C. Jones, 1998: 196) 20 0 No W-m. 7 -19 education 20 -39 40 -59 60 -74 75+

![• “It is significant that the … English-medium [pupils] obtained an overall score • “It is significant that the … English-medium [pupils] obtained an overall score](https://present5.com/presentation/-103116360_437592592/image-27.jpg)

• “It is significant that the … English-medium [pupils] obtained an overall score of 42 per cent [dialect use] … 23 per cent lower than [those in] Welsh-medium education. The speech of these children, who learn Welsh at home … is still heavily coloured by local features. This is irrefutable evidence of the influence of Welsh-medium education …. ” (M. C. Jones, 1998: 204) • “It is significant that such a leap in standardization and dialect mixing should occur in the Welsh of the first generation to have Welsh-medium media and a complete system of Welsh-medium education” (M. C. Jones, 1994: 256) • “Welsh-medium comprehensive schools typically have … wide catchment areas, bringing together pupils from many different communities … resulting in many different varieties being spoken in these schools, creating an environment conducive to dialect mixing. ” (M. C. Jones, 1998: 94) • Local dialect use prompts “teasing … by classmates. … The stigma attached to the dialect … provoked in them a conscious attempt to conform to a more standardised variety in order to be more like their friends” (M. C. Jones, 1998: 196) Those who first learn Welsh in school are exposed mainly to Standard Welsh. Existing Welsh speakers face new pressures towards Standard Welsh.

• Diversity in Welsh declining on (at least) two levels: • Dialect convergence/weakening, which is common to other “healthy” languages like English and French (M. C. Jones, 1998: 235) • New pressures, apparently created by the propagation of a standardised language, i. e. by the revival itself. “most of the linguistic processes that are common in language death situations are also common in contact situations in which no languages are dying” (Thomason, 2001: 230). “What is noteworthy [in] modern spoken Welsh […] is the amount and rate of change” (M. C. Jones, 1998: 235 – orig. emphasis)

• “Their Welsh is becoming a non-locatable amalgam of elements drawn from all over Wales” (M. C. Jones, 1998: 117). • “Welsh dialects are becoming increasingly mixed and standardised, to the extent that young Welsh speakers can no longer reliably identify […] their own […] dialect. […] [T]he language will survive at the cost of its dialectal diversity” (Mc. Mahon, 1994: 291). • ‘Linguistic diversity’ declines, despite apparent increase in speakers (the main measure of success in the revival).

• “Linguistic diversity is one of the most precious elements of the European cultural heritage. The cultural identity of Europe cannot be constructed on the basis of linguistic standardisation. ” (Co. E 1992 a: Paragraph 26) • ‘Linguistic standardisation’ is disparaged yet depended on. • ‘Linguistic diversity’ is championed yet ill-defined, neglected and eroded. • “non-standard varieties of the minority language – and the speakers who use them – can easily become marginalized … particularly … in schools, where standard language forms earn higher marks and produce greater career opportunities” (Freeland & Patrick, 2004: 14) • Recent policy is not to blame for all these declines in diversity, but nor does it address them; and indeed seems to introduce its own new pressures upon diversity. See also Sayers & Láncos (2014, in prep. )

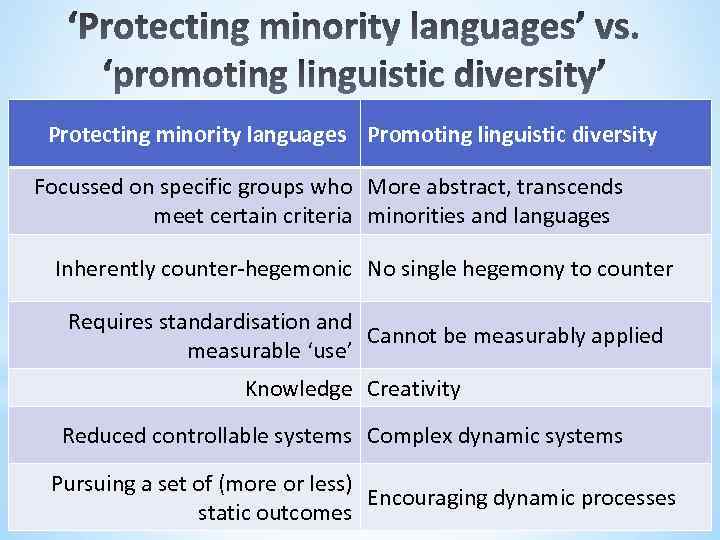

Protecting minority languages Promoting linguistic diversity Focussed on specific groups who More abstract, transcends meet certain criteria minorities and languages Inherently counter-hegemonic No single hegemony to counter Requires standardisation and Cannot be measurably applied measurable ‘use’ Knowledge Creativity Reduced controllable systems Complex dynamic systems Pursuing a set of (more or less) Encouraging dynamic processes static outcomes

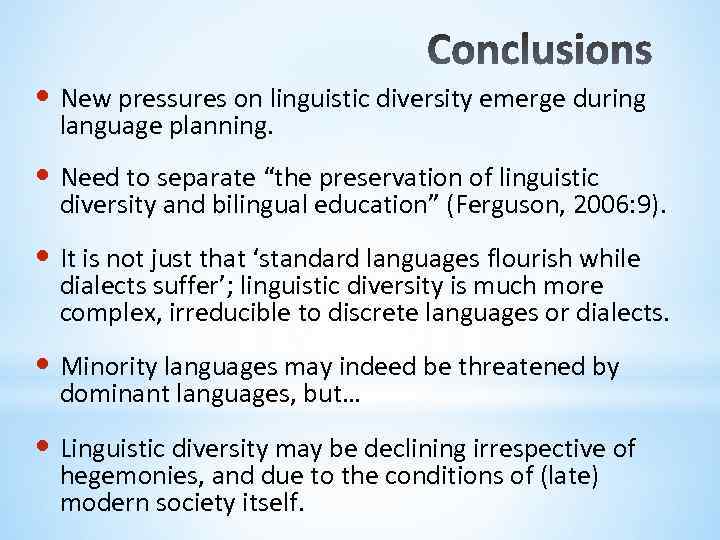

• New pressures on linguistic diversity emerge during language planning. • Need to separate “the preservation of linguistic diversity and bilingual education” (Ferguson, 2006: 9). • It is not just that ‘standard languages flourish while dialects suffer’; linguistic diversity is much more complex, irreducible to discrete languages or dialects. • Minority languages may indeed be threatened by dominant languages, but… • Linguistic diversity may be declining irrespective of hegemonies, and due to the conditions of (late) modern society itself.

• • • • • • Austin, P. (2007). ‘Survival of language’. In E. B. E. Shuckburgh, Survival: The Survival of the Human Race, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press (pp. 80 -98). Balboni, P. E. (2004) Transition to Babel: The Language Policy of the European Union. Transition Studies Review 11(3), 161 -170. Britain, D. (2005). ‘Innovation diffusion, ‘Estuary English’ and local dialect differentiation: the survival of Fenland Englishes’. Linguistics, 43(5): 995 -1022. Britain, D. (2009). ‘One foot in the grave? Dialect death, dialect contact, and dialect birth in England’. Int’l. J. Soc. Lang. 196/197: 121– 155. Chambers, J. K. & P. Trudgill (1998). Dialectology (2 nd ed. ). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press Cheshire, J. , Kerswill, P. , Fox, S. and Torgersen, E. (2011), Contact, the feature pool and the speech community: The emergence of Multicultural London English. Journal of Sociolinguistics, 15: 151– 196. Co. E (Council of Europe) (1992 a) European Charter for Regional or Minority Languages: Explanatory Report. European Treaty Series 148. Strasbourg: Council of Europe. Co. E (Council of Europe) (1992 b) European Charter for Regional or Minority Languages. European Treaty Series 148. Strasbourg: Council of Europe. Cornish Language Partnership newsletter (2007). <www. magakernow. org. uk> Coupland, N. , H. Bishop, A. Williams, B. Evans & P. Garrett (2005). ‘Affiliation, Engagement, Language Use and Vitality: Secondary School Students’ Subjective Orientations to Welsh and Welshness’. International Journal of Bilingual Education & Bilingualism, 8(1): 1 -24. De. Graff, M. (2001). ‘Morphology and Creole Genesis: Linguistics and Ideology’. In K. Hale (ed. ), A Life in Language, Cambridge, MA: MIT Press (pp. 53 -121). De Schutter, H. (2007) Language policy and political philosophy: On the emerging linguistic justice debate. Language Problems & Language Planning, 31(1): 1 -23. Dominicis, A. D. , (2008). Undescribed and Endangered Languages: the Preservation of Linguistic Diversity, Newcastle-upon-Tyne: Cambridge Scholars. Extra, G. , & K. Yagmur (2005). ‘Sociolinguistic perspectives on emerging multilingualism in urban Europe’. International Journal of the Sociology of Language, 175 -6: 17 -40. European Commission (2003). Promoting Language Learning and Linguistic Diversity. An Action Plan 2004– 2006. Brussels: COM. Also online: <http: //europa. eu. int/eur-lex/Lex. Uri. Serv/site/en/com/2003/com 2003_0449 en 01. pdf> Farrell, S. , Wynford, B. , Higgs, G. and White, S. (1997) The Distribution of Younger Welsh Speakers in Anglicised Areas of South East Wales. Journal of Multilingual and Multicultural Development, 18(6): 489 -495. Ferguson, G. (2006) Language Planning and Education. Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press. Freeland, J. & D. Patrick (2004). ‘Language rights and language survival: Sociolinguistic and sociocultural perspectives’. In J. Freeland D. Patrick (eds. ), Language Rights and Language Survival: Sociolinguistic and Sociocultural Perspectives, Manchester: St. Jerome (pp. 1 -33). Grenoble, L. A. and Whaley, L. J. (2006) Saving Languages: An Introduction to Language Revitalization. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. Hernández, J. M. , & J. M. Jiménez-Cano (2003). ‘Broadcasting Standardisation: An analysis of the linguistic normalisation process in Murcian Spanish’. Journal of Sociolinguistics, 7(3): 321 -347. Holes, C. (1986). ‘The social motivation for phonological convergence in three Arabic dialects’. International Journal of the Sociology of Language, 61: 33 -51. Jones, H. (2005) A longitudinal study: Welsh in the census. Cardiff: Bwrdd yr Iaith Gymraeg. Jones, M. C. (1994) Standardization in modern spoken Welsh. In M. M. Parry, W. V. Davies & R. A. M. Temple (eds. ), The Changing Voices of Europe, Cardiff: University of Wales Press (pp. 243 -264). Jones, M. C. (1998) Language Obsolescence and Revitalization: Linguistic Change in Two Sociolinguistically Contrasting Welsh Communities. Oxford: Clarendon Press.

• Kerswill, P. (2003). ‘Dialect levelling and geographical diffusion in British English’. In D. Britain & J. Cheshire (eds. ), Social Dialectology, Amsterdam: John Benjamins (pp. 223 -43). • Kibbee, D. A. (2003). Language policy and linguistic theory. In J. Maurais & M. A. Morris (eds. ), Languages in a Globalising World, Cambridge: CUP (pp. 47 -57). • Kuiper, L. (2005). ‘Perception is reality: Parisian and Provencal perceptions of regional varieties of French’. Journal of Sociolinguistics 9(1), 2005: 28 -52. • Kuper, Adam (1999). Culture: The Anthropologist’s Account. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press. • Labov, W. (2008). ‘Unendangered Dialects, Endangered People’. In K. A. King et al. (eds. ), Sustaining Linguistic Diversity: Endangered and Minority Languages and Language Varieties, Washington, DC: Georgetown University Press (pp. 219 -238). • Loos, E. 2007. Language policy in an enacted world: the organization of linguistic diversity. Language Problems & Language Planning, 31(1): 37 -60 • Mac. Kinnon, K, (2000). ‘An Independent Academic Study on Cornish’. linguae-celticae. org/dateien/Independent_Study_on_Cornish_Language. pdf • May, S. (2000). ‘Uncommon languages: The challenges and possibilities of minority language rights’. Journal of Multilingual and Multicultural Development, 21: 366 -385. • Mc. Mahon, A. (1994) Understanding Language Change. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. • Mc. Pake, J. et al. (2004). ‘Promoting linguistic diversity? Local, National and Europe-wide Support for Community Languages’. Unpublished paper at Language and the Future of Europe: Ideologies, Policies and Practices, Southampton, UK. • ONS – Office for National Statistics. 2004. Welsh Language – Welsh speakers increase to 21%. www. statistics. gov. uk/CCI/nugget. asp? ID=447 • ONS – Office for National Statistics. 2011. Statistical bulletin: 2011 Census: Key Statistics for Wales, March 2011. http: //www. ons. gov. uk/ons/rel/census/2011 census/key-statistics-for-unitary-authorities-in-wales/stb-2011 -census-key-statistics-for-wales. html • Ricento, T. (2005). ‘Problems with the ‘language-as-resource’ discourse in the promotion of heritage languages in the U. S. A. ’. J. Sociolinguistics, 9(3): 348 -368. • Renkó-Michelsén, Zsuzsanna. 2013. Language death and revival: Cornish as a minority language in UK. J. Estonian and Finno-Ugric Linguistics 4(2): 179 -197. • Renkó-Michelsén, Zsuzsanna (in prep. ). Intergenerational Transmission of Revived Cornish. Ph. D dissertation, University of Helsinki. • Romaine, S. (2006). ‘Planning for the survival of linguistic diversity’. Language Policy, 5(2): 441 -473. • Sayers, Dave. 2012. Standardising Cornish: The politics of a new minority language. Language Problems & Language Planning 36(2): 99– 119. • Sayers, Dave & Petra Lea Láncos. 2014. (Re)defining linguistic diversity: what is being protected in European language policy? Legal and sociolinguistic insights. Presentation to Multidisciplinary Approaches in Language Policy & Planning. U. Calgary. www. academia. edu/7503981/ • Sayers, Dave & Zsuzsanna Renkó-Michelsén (forthcoming). Phoenix from the Ashes: Reconstructed Cornish in relation to Einar Haugen’s four-step model of language standardisation. Sociolinguistica 29. • Schneider, Edgar. 2015. Calling World Englishes as complex dynamic systems: diffusion, restructuring, exaptation. Plenary address to Changing English, University of Helsinki. • Siegel, J. (2001). ‘Koine formation and creole genesis’. In N. Smith & T. Veenstra (eds. ), Creolization and Contact, Amsterdam: John Benjamins (pp. 175 -97). • Spolsky, B. (2004) Language Policy. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. • Stanford, J. N. & Preston, D. R. (eds. ), 2009. Variations in Indigenous Minority Languages. Amsterdam: John Benjamins. • Strubell, M. (2007). ‘The Political Discourse on Multilingualism in the European Union’. In D. Castiglione & C. Longman (eds. ), The Language Question in Europe and Diverse Societies: Political, Legal and Social Perspectives. Oxford: Hart (pp. 149 -184). • Watt, D. (2002). ‘ ‘I don’t speak with a Geordie accent, I speak, like, the Northern accent’: Contact-induced levelling in the Tyneside vowel system’. Journal of Sociolinguistics, 6(1): 44 -63. • Wright, S. (2007). ‘What is a Language? The Difficulties Inherent in Language Rights’. In D. Castiglione & C. Longman (eds. ), The Language Question in Europe and Diverse Societies: Political, Legal and Social Perspectives, Oxford: Hart (pp. 81 -100).

Q&A dave. sayers@cantab. net This presentation (and lots of other stuff!) available at: http: //shu. academia. edu/Dave. Sayers/

Re_defining_linguistic_diversity_what_i.pptx