f8846515820cb9382fd87db9feaface1.ppt

- Количество слайдов: 51

Randomisation: Has it been done properly? Professor David Torgerson Director, York Trials Unit

“Randomized controlled trials appear to annoy human nature – if properly conducted indeed they should. ” (Schulz, 1995)

Background • The methodological feature of RCTs that has the strongest association with an outcome’s effect size is the quality of randomisation • Poor quality randomisation is generally associated with larger intervention effects than high quality allocation methods

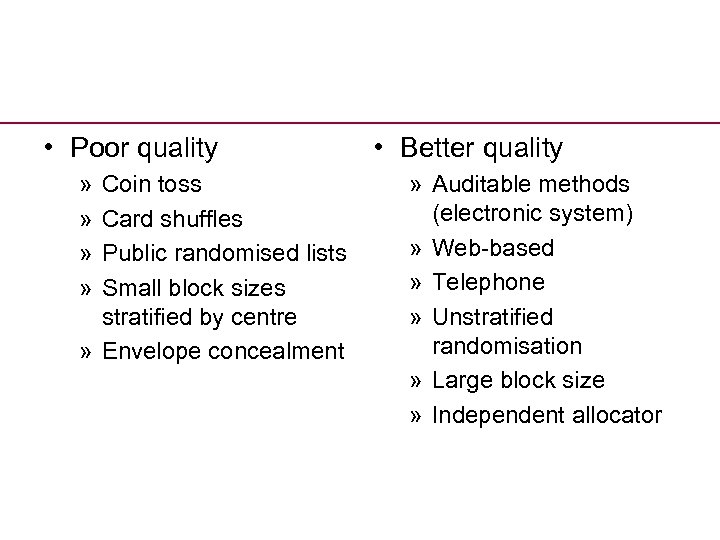

• Poor quality » » Coin toss Card shuffles Public randomised lists Small block sizes stratified by centre » Envelope concealment • Better quality » Auditable methods (electronic system) » Web-based » Telephone » Unstratified randomisation » Large block size » Independent allocator

Randomisation • Significant numbers of trials do not describe a robust randomisation mechanism or there is evidence that the allocation has not been followed • In this presentation I will discuss examples of poor allocation

Concealed allocation • All RCTs can use concealed allocation – often confused with blinding (which often is not possible) • Concealed allocation is where we separate the act of randomisation from those who could be ‘annoyed’ by the use of randomisation – e. g. , clinicians, teachers, developers, some researchers, etc • Independent concealed allocation is the hallmark of a good trial

Randomisation reminder • Two types of randomisation: » Simple » Restricted • Simple » Like tossing a coin – cannot predict next allocation on basis of previous ones • Restricted » Usually using blocked randomisation future allocations can partly be predicted by historic allocations.

Blocked randomisation • Most common method of restricted allocation – uses blocks of repeating allocation (e. g. , block of 4 is: ABAB, AABB, BBAA, BABA, BAAB, ABBA) • Note: numerical imbalance is half the block size x number of stratifying variables (e. g. , block of (4 x 0. 5) x 2 stratifiers = 4 • REMEMBER for oncoming test!

History of poor randomisation • Since mid-1990 s qualitative and quantitative evidence has shown that in health care trials randomisation has been subverted • But subverted allocation occurs in nonhealth care trials as well – just more evidence in health care as methodologists have more trials to look at

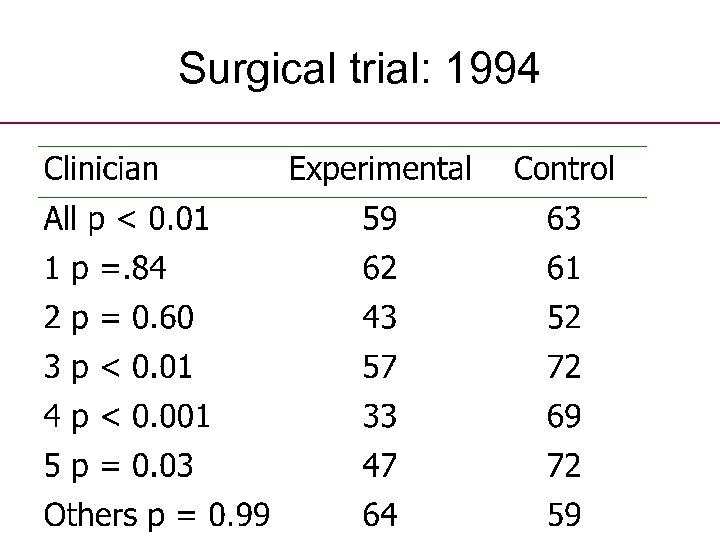

Surgical trial: 1994

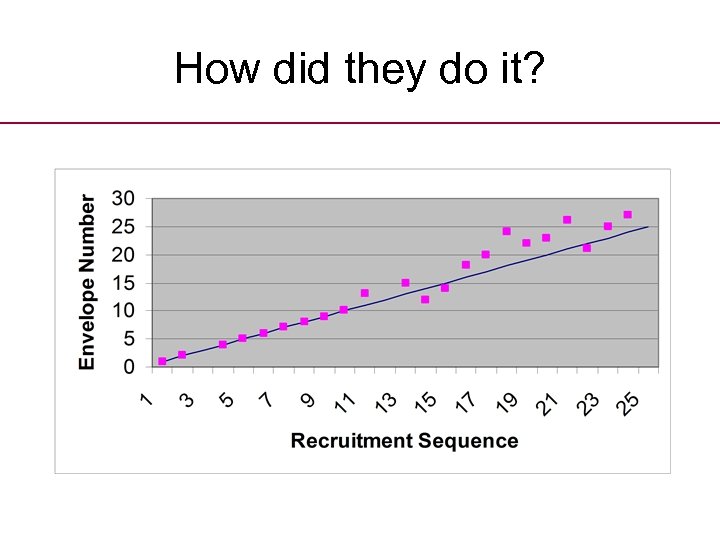

How did they do it?

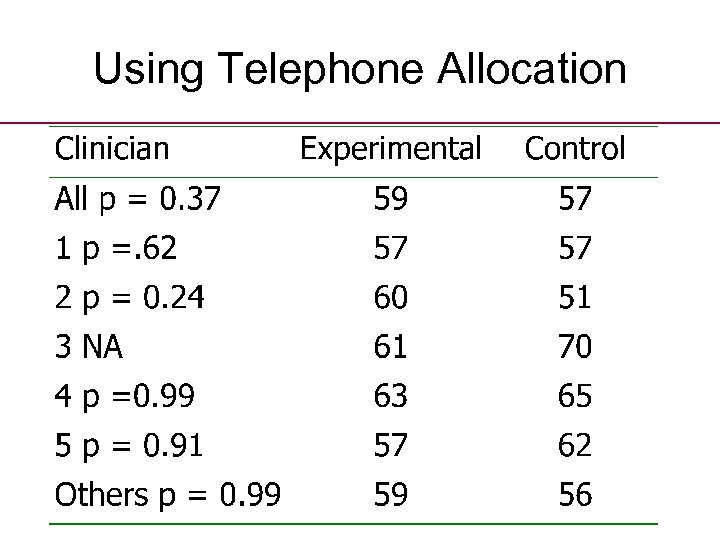

Using Telephone Allocation

First Test • Remember blocking this ensures numerical balance across the stratifying variable • It is common to stratify by study site to ensure similar numbers of participants are in each group at each site

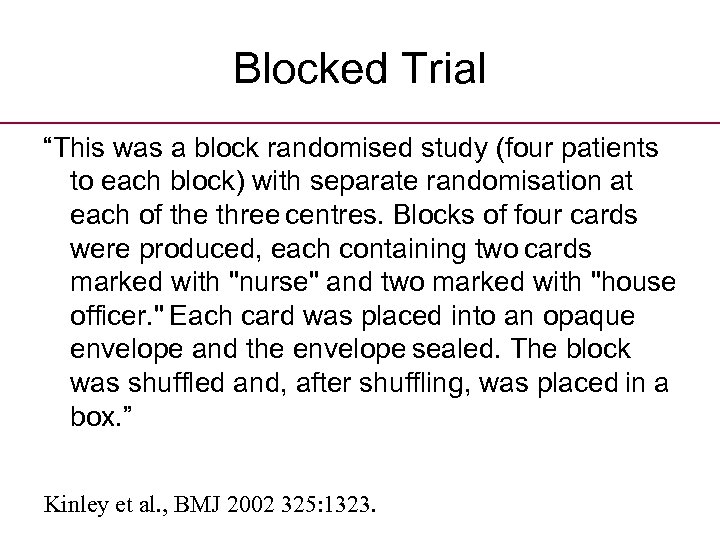

Blocked Trial “This was a block randomised study (four patients to each block) with separate randomisation at each of the three centres. Blocks of four cards were produced, each containing two cards marked with "nurse" and two marked with "house officer. " Each card was placed into an opaque envelope and the envelope sealed. The block was shuffled and, after shuffling, was placed in a box. ” Kinley et al. , BMJ 2002 325: 1323.

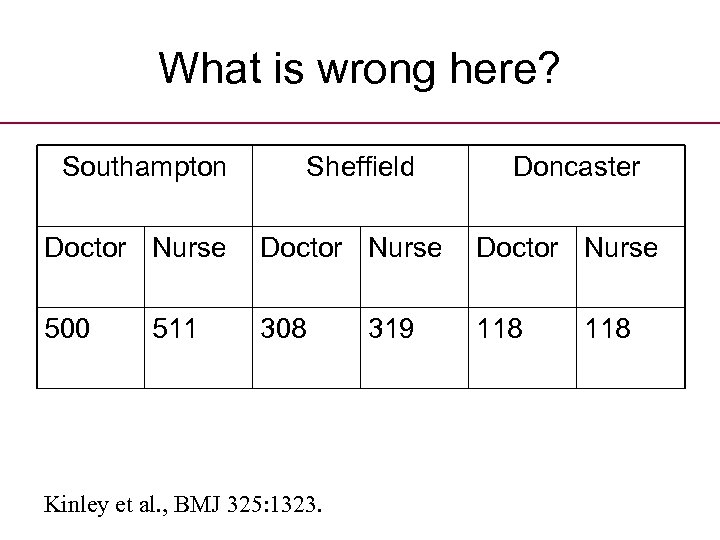

What is wrong here? Southampton Sheffield Doncaster Doctor Nurse 500 308 118 511 Kinley et al. , BMJ 325: 1323. 319 118

• Didn’t see it » Never mind nor did BMJ’s referees or the study statistician • Saw it » Well done! • Now some quantitative evidence

Subversion – survey evidence • In a survey of 25 researchers 4 admitted to keeping ‘a log’ of previous allocations to try and predict future allocations. Brown et al. Stats in Medicine, 2005, 24: 3715.

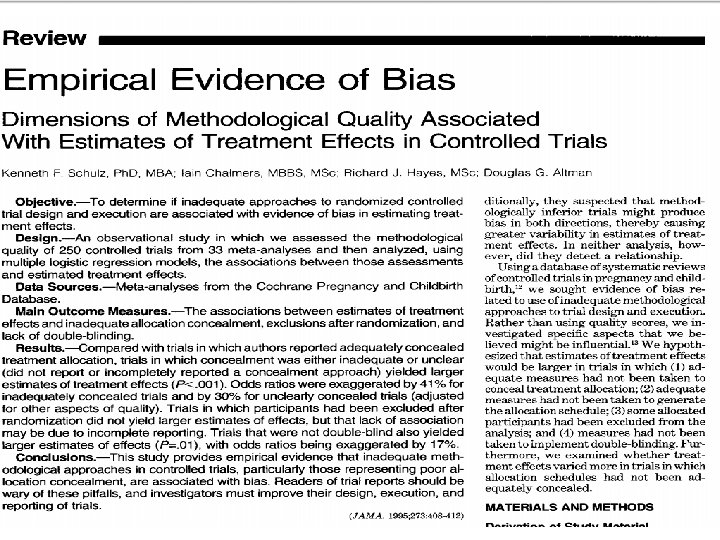

More Evidence • Hewitt and colleagues examined the association between p values and adequate concealment in 4 major medical journals. • Inadequate concealment largely used opaque envelopes. • The average p value for inadequately concealed trials was 0. 022 compared with 0. 052 for adequate trials (test for difference p = 0. 045). Hewitt et al. BMJ; 2005: March 10 th.

Not trial evidence? • OK this is ‘observational’ data it could be that those researchers who use poor randomisation method are more likely to choose ‘effective’ interventions than those researchers who use robust randomisation systems • Some people believe the Earth is flat, the moon is made of cheese and that homeopathy works!

Meta-analysis of age Why on earth would you do that? We know the null is true!

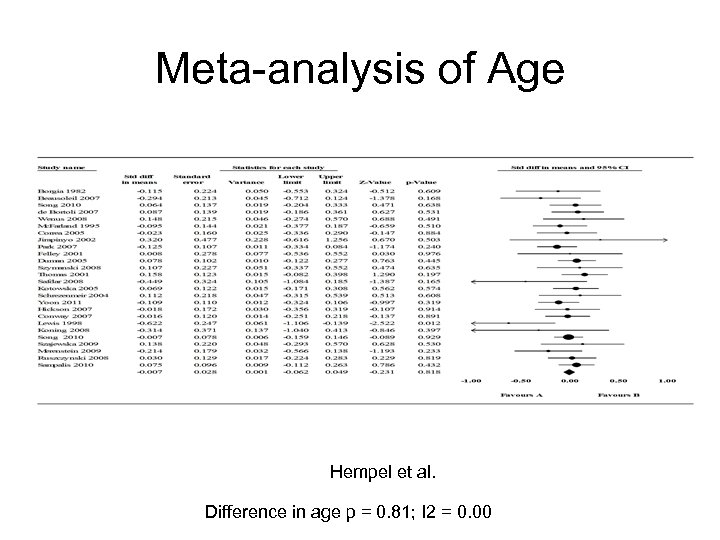

Meta-analysis of Age Hempel et al. Difference in age p = 0. 81; I 2 = 0. 00

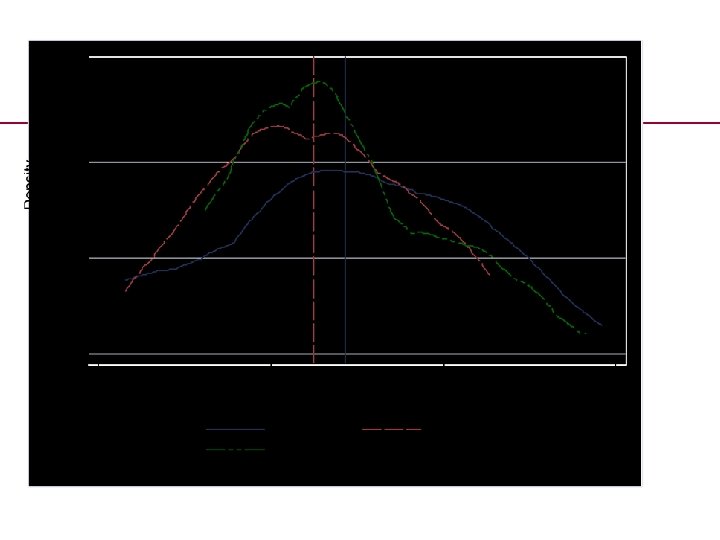

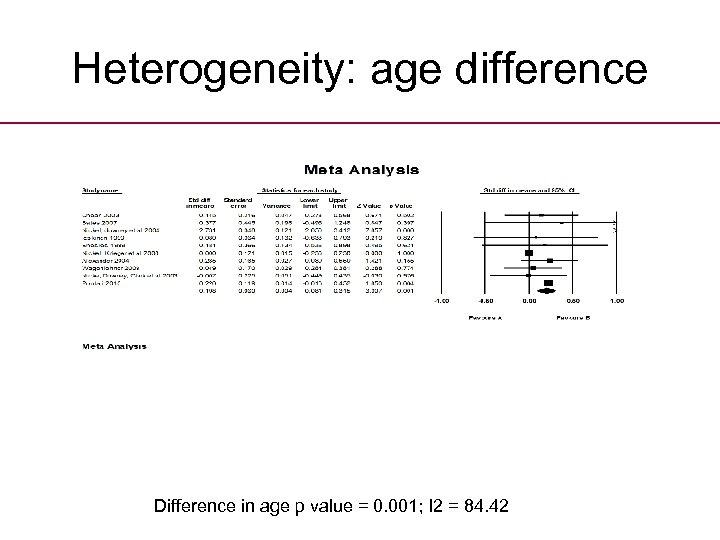

Heterogeneity: age difference Difference in age p value = 0. 001; I 2 = 84. 42

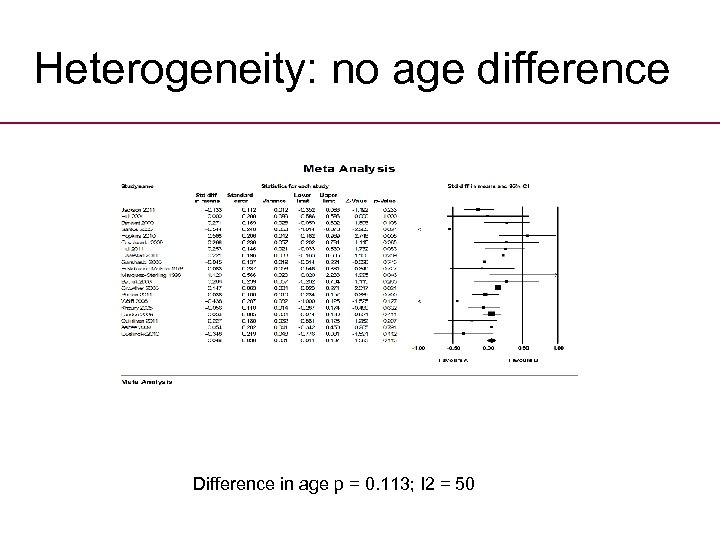

Heterogeneity: no age difference Difference in age p = 0. 113; I 2 = 50

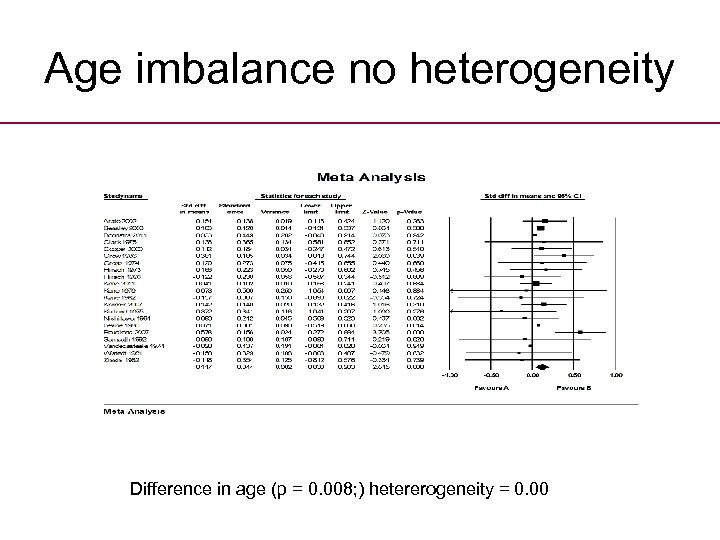

Age imbalance no heterogeneity Difference in age (p = 0. 008; ) hetererogeneity = 0. 00

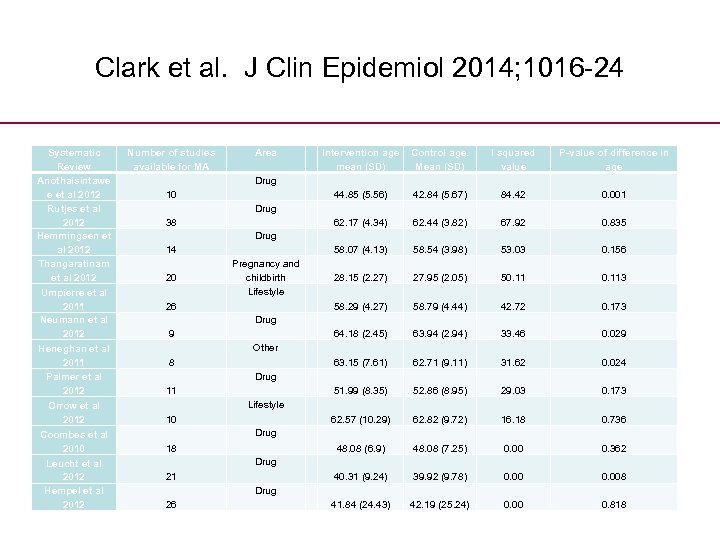

Clark et al. J Clin Epidemiol 2014; 1016 -24 Systematic Review Anothaisintawe e et al 2012 Rutjes et al 2012 Hemmingsen et al 2012 Thangaratinam et al 2012 Umpierre et al 2011 Neumann et al 2012 Heneghan et al 2011 Palmer et al 2012 Number of studies available for MA 10 38 14 20 Area Intervention age Control age. mean (SD) Mean (SD) Drug 44. 85 (5. 56) 42. 84 (5. 67) Drug 62. 17 (4. 34) 62. 44 (3. 82) Drug 58. 07 (4. 13) 58. 54 (3. 98) Pregnancy and childbirth 28. 15 (2. 27) 27. 95 (2. 05) Lifestyle 26 67. 92 0. 835 53. 03 0. 156 50. 113 0. 173 63. 94 (2. 94) 33. 46 0. 029 62. 71 (9. 11) 31. 62 0. 024 51. 99 (8. 35) 52. 86 (8. 95) 29. 03 0. 173 62. 57 (10. 29) 62. 82 (9. 72) 16. 18 0. 736 48. 08 (6. 9) 48. 08 (7. 25) 0. 00 0. 362 40. 31 (9. 24) 39. 92 (9. 78) 0. 008 41. 84 (24. 43) 42. 19 (25. 24) 0. 00 0. 818 Lifestyle 42. 72 63. 15 (7. 61) Drug 58. 79 (4. 44) 8 11 18 Drug 21 26 0. 001 64. 18 (2. 45) Other 10 Leucht et al 2012 Hempel et al 2012 84. 42 9 Coombes et al 2010 P-value of difference in age 58. 29 (4. 27) Drug Orrow et al 2012 I squared value

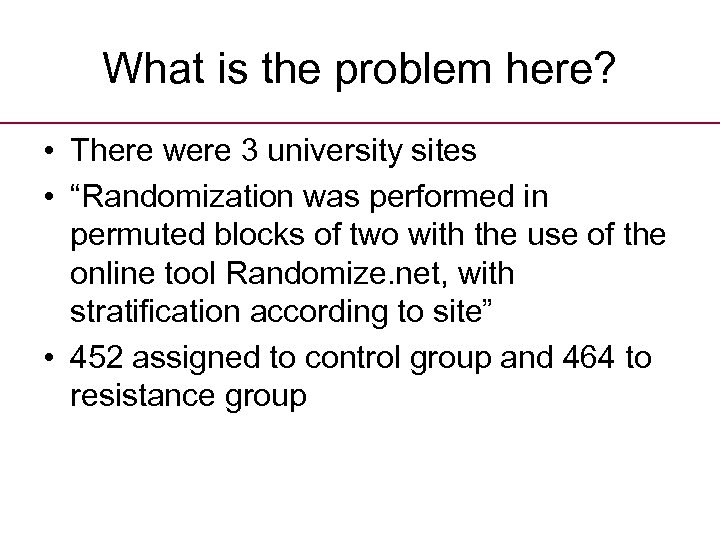

What is the problem here? • There were 3 university sites • “Randomization was performed in permuted blocks of two with the use of the online tool Randomize. net, with stratification according to site” • 452 assigned to control group and 464 to resistance group

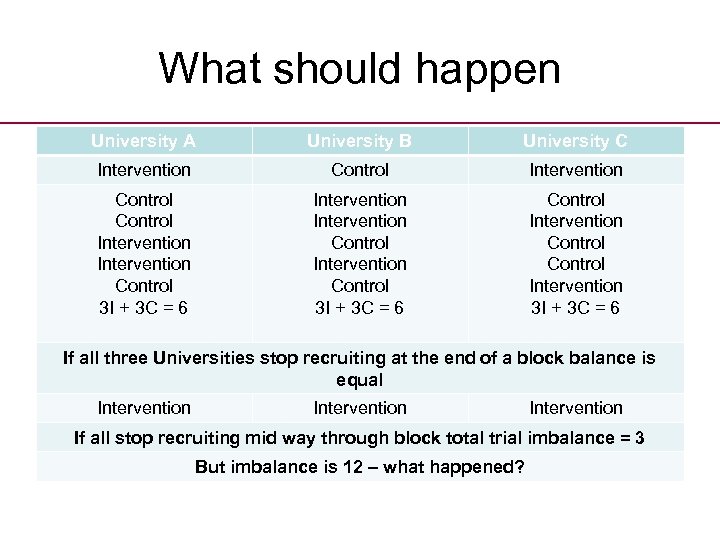

What should happen University A University B University C Intervention Control Intervention Control 3 I + 3 C = 6 Intervention Control 3 I + 3 C = 6 Control Intervention 3 I + 3 C = 6 If all three Universities stop recruiting at the end of a block balance is equal Intervention If all stop recruiting mid way through block total trial imbalance = 3 But imbalance is 12 – what happened?

Problem? • Imbalance of 12 – assume 2 due to trial finishing half way through the block leaves 10 – authors state the reasons were quasirandom (e. g. , computer glitch) – but for all 10 to end up in one group through random processes is unlikely (p = 0. 004).

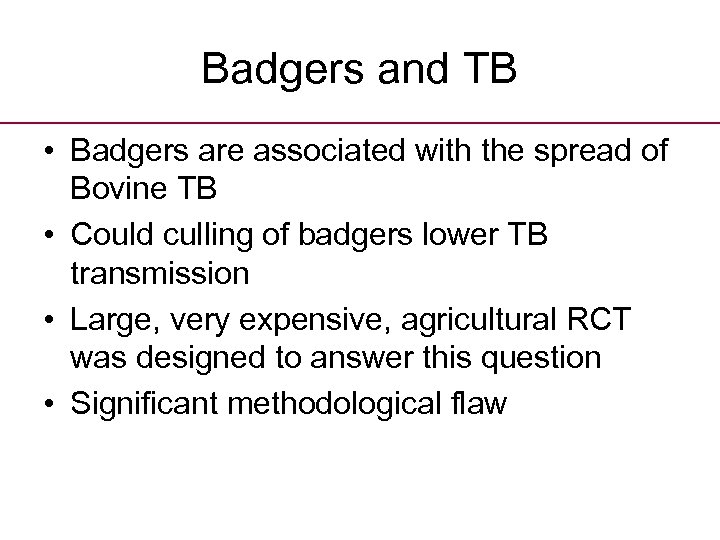

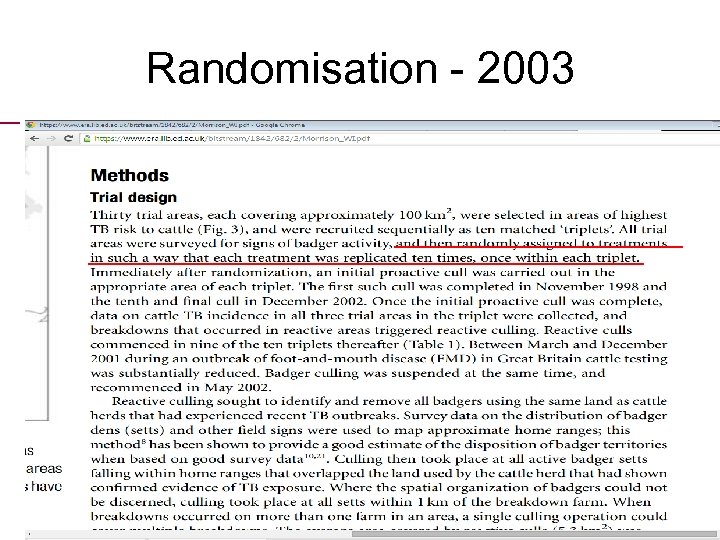

Badgers and TB • Badgers are associated with the spread of Bovine TB • Could culling of badgers lower TB transmission • Large, very expensive, agricultural RCT was designed to answer this question • Significant methodological flaw

Design of badger trial - 2003

Randomisation - 2003

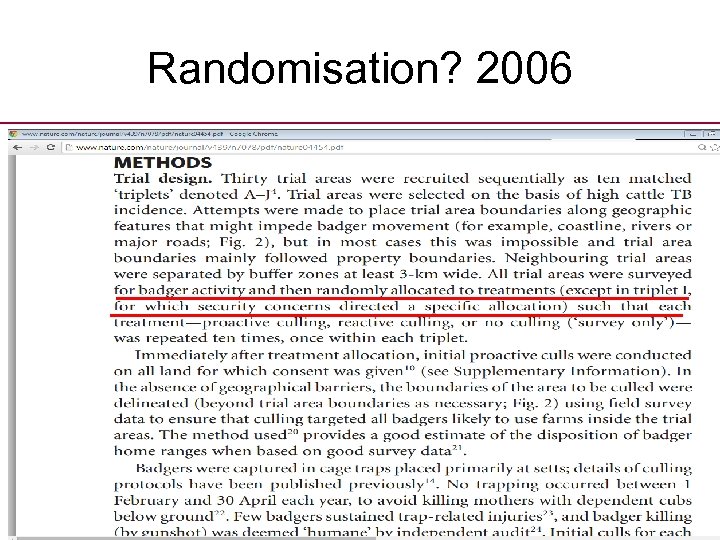

Randomisation? 2006

Is it a RCT? • It seems that 10% of the allocation was deterministic not random • At the very least a sensitivity analysis should have been done to see if the exclusion of that triplet altered the results

CONSORT statement • Most health care journals and many nonhealth care journals request RCTs follow CONSORT guidance for reporting • Yet in RCTs published in 2015 in the top 4 medical journals (BMJ, JAMA, Lancet New England Journal) 22% don’t give enough information, 19% use poor allocation concealment Clark et al, BMJ 2016: In press.

What about other areas? • So far mainly anecdote » Police trial in USA, officers subverted allocation to ensure ‘worse’ perpetrators were taken to police station » Work and Pensions trial allocated by NI number and found unequal groups » Education trial some allocations changed to match school preference

Stick to the randomisation • Even when randomisation has been done properly some over-ride the allocation because it is not preferred or for some other reason • Again can introduce bias

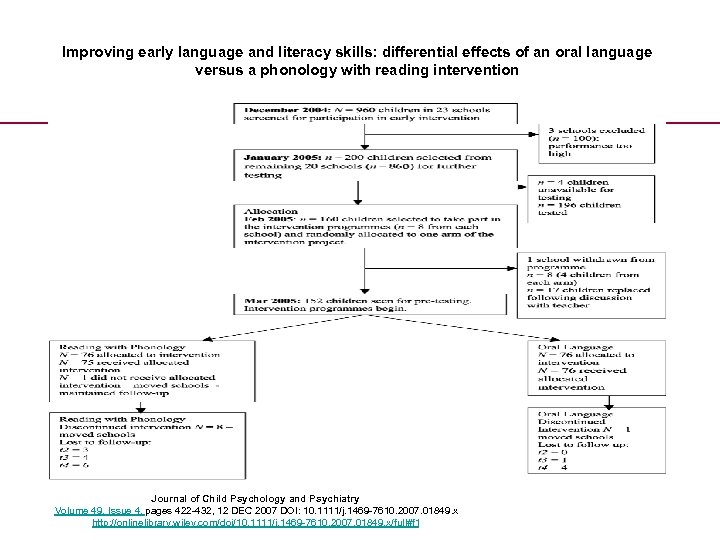

Improving early language and literacy skills: differential effects of an oral language versus a phonology with reading intervention Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry Volume 49, Issue 4, pages 422 -432, 12 DEC 2007 DOI: 10. 1111/j. 1469 -7610. 2007. 01849. x http: //onlinelibrary. wiley. com/doi/10. 1111/j. 1469 -7610. 2007. 01849. x/full#f 1

Solutions? • Independent, verifiable, randomisation procedure » Mechanical methods, coin toss, card shuffling cannot be audited or varified • Large studies (n>100 -200) use simple randomisation • Small studies use minimisation

Note on cluster randomised trials • Allocation concealment is essential in individual randomised trials it is also essential cluster randomised trials • In a cluster trial groups of individuals (e. g. , pupils in a school) are randomised • To conceal the allocation recruitment of the individuals must be done before recruitment • Often this does not happen

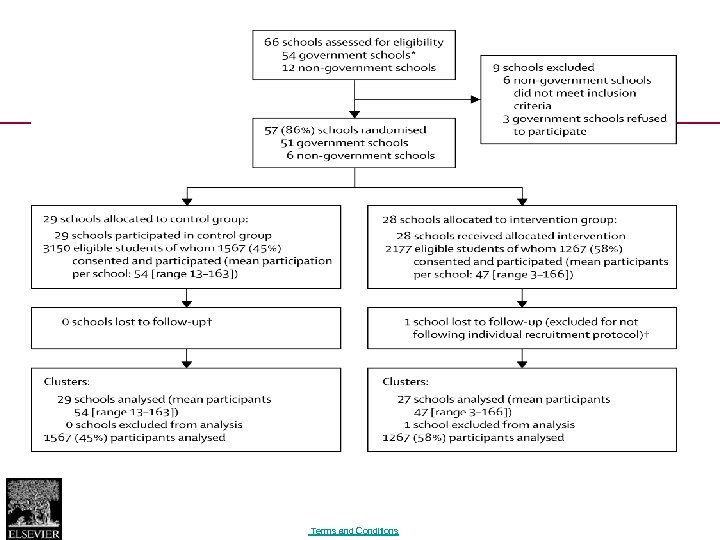

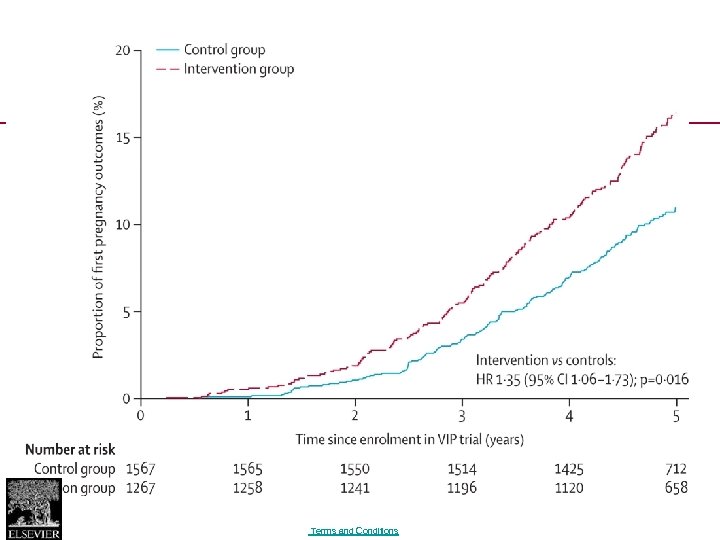

Efficacy of infant simulator programmes to prevent teenage pregnancy: a school-based cluster randomised controlled trial in Western Australia Dr Sally A Brinkman, Ph. D, Sarah E Johnson, Ph. D, Prof James P Codde, Ph. D, Michael B Hart, FAFPHM, Judith A Straton, MD, Murthy N Mittinty, Ph. D, Prof Sven R Silburn, MSc The Lancet DOI: 10. 1016/S 0140 -6736(16)30384 -1 Copyright © 2016 Elsevier Ltd Terms and Conditions

Figure 1 The Lancet DOI: (10. 1016/S 0140 -6736(16)30384 -1) Copyright © 2016 Elsevier Ltd Terms and Conditions

Figure 2 The Lancet DOI: (10. 1016/S 0140 -6736(16)30384 -1) Copyright © 2016 Elsevier Ltd Terms and Conditions

Conclusions • There is a long and ignoble history of misallocation in RCTs in health care, which is ongoing • It is very likely the same problem afflicts non-health care trials • We need to ensure rigorous and robust allocation methods for our trials

f8846515820cb9382fd87db9feaface1.ppt