b4ecf48874d996cff263b4d3670e7a4b.ppt

- Количество слайдов: 139

Querying XML: XQuery, XPath, and SQL/XML in Context Authors: Jim Melton and Stephen Buxton Publisher: Morgan Kaufmann Publication Year: 2006 Lecturer: Kyungpook National University School of EECS Laboratory of Database Systems Young Chul Park 2007 -7/KNU Querying XML: XQuery, XPath, and SQL/XML in Context

Querying XML: XQuery, XPath, and SQL/XML in Context Authors: Jim Melton and Stephen Buxton Publisher: Morgan Kaufmann Publication Year: 2006 Lecturer: Kyungpook National University School of EECS Laboratory of Database Systems Young Chul Park 2007 -7/KNU Querying XML: XQuery, XPath, and SQL/XML in Context

Chapter 10 Introduction to XQuery 1. 0 10. 7 The XQuery Type System Each item in the XQuery Data Model has at least a value and a type name. 10. 7. 1 What Is a Type System Anyway? A type system is a system of splitting entities up into named sets. A strongly typed language such as Java or SQL may do type checking at compile time (static typing) or at run time (dynamic typing). With pessimistic static typing, the processor returns a type error whenever there may be a type error at run time, but if this pessimistic static type check succeeds, then the processor can confidently proceed with the rest of the program or query without bothering with any further type checking. Pessimistic static type checking gains efficiency at the expense of some false type errors. XQuery is a strongly typed language – every entity (every element, attribute, atomic value, etc) has both a value and a type name, and functions and operators are defined to work only on some (combinations of) types. XQuery has an optional static typing feature, which uses pessimistic static typing. 2007 -7/KNU Querying XML: XQuery, XPath, and SQL/XML in Context 2

Chapter 10 Introduction to XQuery 1. 0 10. 7 The XQuery Type System Each item in the XQuery Data Model has at least a value and a type name. 10. 7. 1 What Is a Type System Anyway? A type system is a system of splitting entities up into named sets. A strongly typed language such as Java or SQL may do type checking at compile time (static typing) or at run time (dynamic typing). With pessimistic static typing, the processor returns a type error whenever there may be a type error at run time, but if this pessimistic static type check succeeds, then the processor can confidently proceed with the rest of the program or query without bothering with any further type checking. Pessimistic static type checking gains efficiency at the expense of some false type errors. XQuery is a strongly typed language – every entity (every element, attribute, atomic value, etc) has both a value and a type name, and functions and operators are defined to work only on some (combinations of) types. XQuery has an optional static typing feature, which uses pessimistic static typing. 2007 -7/KNU Querying XML: XQuery, XPath, and SQL/XML in Context 2

Chapter 10 Introduction to XQuery 1. 0 10. 7. 2 XML Schema Types The XQuery type system is based on the types defined in XML Schema Part 2: Datatypes and the structure types defined in XML Schema Part 1: Structures. Datatypes (simple types) Every item (document, node, or atomic value) in the XQuery Data Model has both a value and a named type. XML Schema defines 19 built-in, atomic, primitive data types. – built-in – defined as part of XML Schema, as opposed to user-derived (user-defined) data types. – atomic – a single, indivisible data type definition, as opposed to list (a data type defined as a list of atomic data types) or union (a data type defined as the union of one or more data types). – primitive – a data type that is not defined in terms of other data types. For example, xs: decimal is a primitive data type, while xs: integer is a derived data type, defined as a special case of xs: decimal where fraction. Digits is 0. XML Schema defines 25 built-in, atomic, derived data types. These 44 built-in data types are defined in terms of a value space – the set of values that “belong” to the data type – and a lexical space – the set of valid literals for a data type. Each data type also has some fundamental facets – properties of the data type such as whether the values in the value space have a predefined order, whether the value space is bounded, whether the cardinality of the value space is finite or infinite, and so forth. 2007 -7/KNU Querying XML: XQuery, XPath, and SQL/XML in Context 3

Chapter 10 Introduction to XQuery 1. 0 10. 7. 2 XML Schema Types The XQuery type system is based on the types defined in XML Schema Part 2: Datatypes and the structure types defined in XML Schema Part 1: Structures. Datatypes (simple types) Every item (document, node, or atomic value) in the XQuery Data Model has both a value and a named type. XML Schema defines 19 built-in, atomic, primitive data types. – built-in – defined as part of XML Schema, as opposed to user-derived (user-defined) data types. – atomic – a single, indivisible data type definition, as opposed to list (a data type defined as a list of atomic data types) or union (a data type defined as the union of one or more data types). – primitive – a data type that is not defined in terms of other data types. For example, xs: decimal is a primitive data type, while xs: integer is a derived data type, defined as a special case of xs: decimal where fraction. Digits is 0. XML Schema defines 25 built-in, atomic, derived data types. These 44 built-in data types are defined in terms of a value space – the set of values that “belong” to the data type – and a lexical space – the set of valid literals for a data type. Each data type also has some fundamental facets – properties of the data type such as whether the values in the value space have a predefined order, whether the value space is bounded, whether the cardinality of the value space is finite or infinite, and so forth. 2007 -7/KNU Querying XML: XQuery, XPath, and SQL/XML in Context 3

Chapter 10 Introduction to XQuery 1. 0 In addition to these 44 built-in data types, XML Schema allows for user-derived (user-defined) data types based on the built-in data types. These user-derived data types may combine the built-in data types using list or union, or they may restrict the value space (and hence the lexical space) of a built-in via some constraining facets – properties that restrict the value space, such as length, or an enumeration of allowable values. XML Schema defines one top-level data type, xs: any. Sinple. Type. 2007 -7/KNU Querying XML: XQuery, XPath, and SQL/XML in Context 4

Chapter 10 Introduction to XQuery 1. 0 In addition to these 44 built-in data types, XML Schema allows for user-derived (user-defined) data types based on the built-in data types. These user-derived data types may combine the built-in data types using list or union, or they may restrict the value space (and hence the lexical space) of a built-in via some constraining facets – properties that restrict the value space, such as length, or an enumeration of allowable values. XML Schema defines one top-level data type, xs: any. Sinple. Type. 2007 -7/KNU Querying XML: XQuery, XPath, and SQL/XML in Context 4

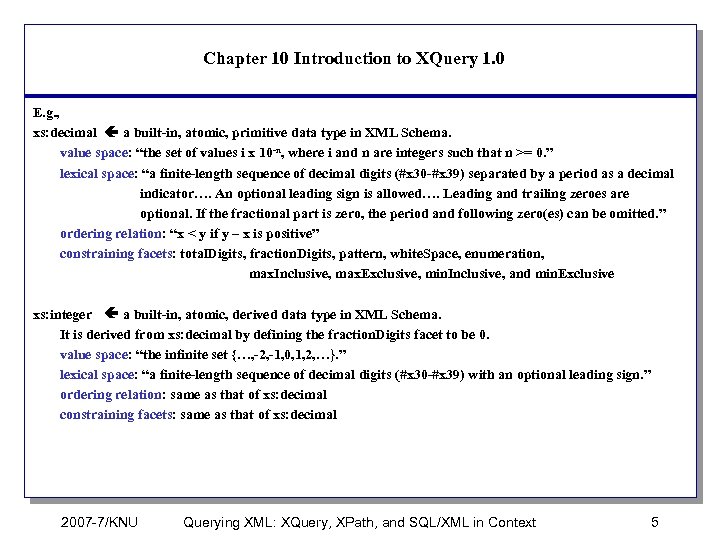

Chapter 10 Introduction to XQuery 1. 0 E. g. , xs: decimal a built-in, atomic, primitive data type in XML Schema. value space: “the set of values i x 10 -n, where i and n are integers such that n >= 0. ” lexical space: “a finite-length sequence of decimal digits (#x 30 -#x 39) separated by a period as a decimal indicator…. An optional leading sign is allowed…. Leading and trailing zeroes are optional. If the fractional part is zero, the period and following zero(es) can be omitted. ” ordering relation: “x < y if y – x is positive” constraining facets: total. Digits, fraction. Digits, pattern, white. Space, enumeration, max. Inclusive, max. Exclusive, min. Inclusive, and min. Exclusive xs: integer a built-in, atomic, derived data type in XML Schema. It is derived from xs: decimal by defining the fraction. Digits facet to be 0. value space: “the infinite set {…, -2, -1, 0, 1, 2, …}. ” lexical space: “a finite-length sequence of decimal digits (#x 30 -#x 39) with an optional leading sign. ” ordering relation: same as that of xs: decimal constraining facets: same as that of xs: decimal 2007 -7/KNU Querying XML: XQuery, XPath, and SQL/XML in Context 5

Chapter 10 Introduction to XQuery 1. 0 E. g. , xs: decimal a built-in, atomic, primitive data type in XML Schema. value space: “the set of values i x 10 -n, where i and n are integers such that n >= 0. ” lexical space: “a finite-length sequence of decimal digits (#x 30 -#x 39) separated by a period as a decimal indicator…. An optional leading sign is allowed…. Leading and trailing zeroes are optional. If the fractional part is zero, the period and following zero(es) can be omitted. ” ordering relation: “x < y if y – x is positive” constraining facets: total. Digits, fraction. Digits, pattern, white. Space, enumeration, max. Inclusive, max. Exclusive, min. Inclusive, and min. Exclusive xs: integer a built-in, atomic, derived data type in XML Schema. It is derived from xs: decimal by defining the fraction. Digits facet to be 0. value space: “the infinite set {…, -2, -1, 0, 1, 2, …}. ” lexical space: “a finite-length sequence of decimal digits (#x 30 -#x 39) with an optional leading sign. ” ordering relation: same as that of xs: decimal constraining facets: same as that of xs: decimal 2007 -7/KNU Querying XML: XQuery, XPath, and SQL/XML in Context 5

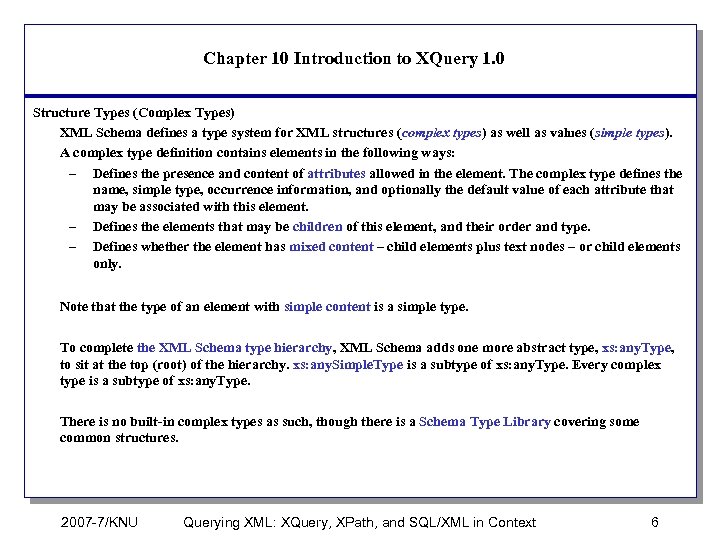

Chapter 10 Introduction to XQuery 1. 0 Structure Types (Complex Types) XML Schema defines a type system for XML structures (complex types) as well as values (simple types). A complex type definition contains elements in the following ways: – Defines the presence and content of attributes allowed in the element. The complex type defines the name, simple type, occurrence information, and optionally the default value of each attribute that may be associated with this element. – Defines the elements that may be children of this element, and their order and type. – Defines whether the element has mixed content – child elements plus text nodes – or child elements only. Note that the type of an element with simple content is a simple type. To complete the XML Schema type hierarchy, XML Schema adds one more abstract type, xs: any. Type, to sit at the top (root) of the hierarchy. xs: any. Simple. Type is a subtype of xs: any. Type. Every complex type is a subtype of xs: any. Type. There is no built-in complex types as such, though there is a Schema Type Library covering some common structures. 2007 -7/KNU Querying XML: XQuery, XPath, and SQL/XML in Context 6

Chapter 10 Introduction to XQuery 1. 0 Structure Types (Complex Types) XML Schema defines a type system for XML structures (complex types) as well as values (simple types). A complex type definition contains elements in the following ways: – Defines the presence and content of attributes allowed in the element. The complex type defines the name, simple type, occurrence information, and optionally the default value of each attribute that may be associated with this element. – Defines the elements that may be children of this element, and their order and type. – Defines whether the element has mixed content – child elements plus text nodes – or child elements only. Note that the type of an element with simple content is a simple type. To complete the XML Schema type hierarchy, XML Schema adds one more abstract type, xs: any. Type, to sit at the top (root) of the hierarchy. xs: any. Simple. Type is a subtype of xs: any. Type. Every complex type is a subtype of xs: any. Type. There is no built-in complex types as such, though there is a Schema Type Library covering some common structures. 2007 -7/KNU Querying XML: XQuery, XPath, and SQL/XML in Context 6

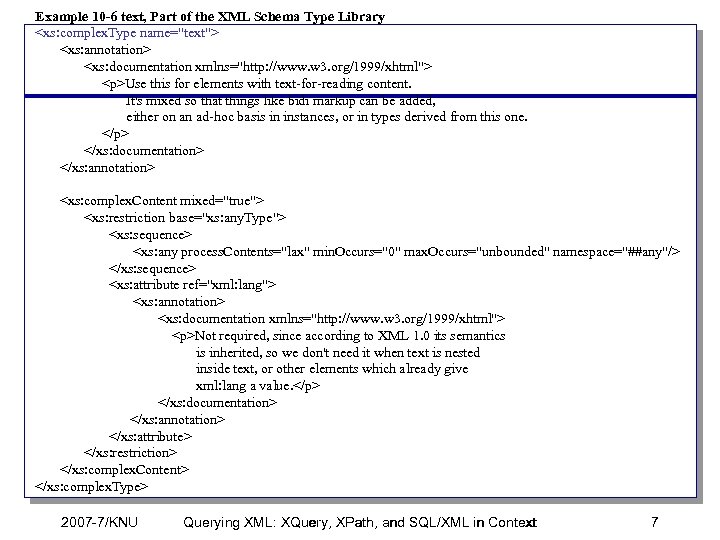

Use this for elements with text-for-reading content. It's mixed so that things like bidi markup can be added, either on an ad-hoc basis in instances, or in types derived from this one. Not required, since according to XML 1. 0 its semantics is inherited, so we don't need it when text is nested inside text, or other elements which already give xml: lang a value.  Example 10 -6 text, Part of the XML Schema Type Library

Example 10 -6 text, Part of the XML Schema Type Library

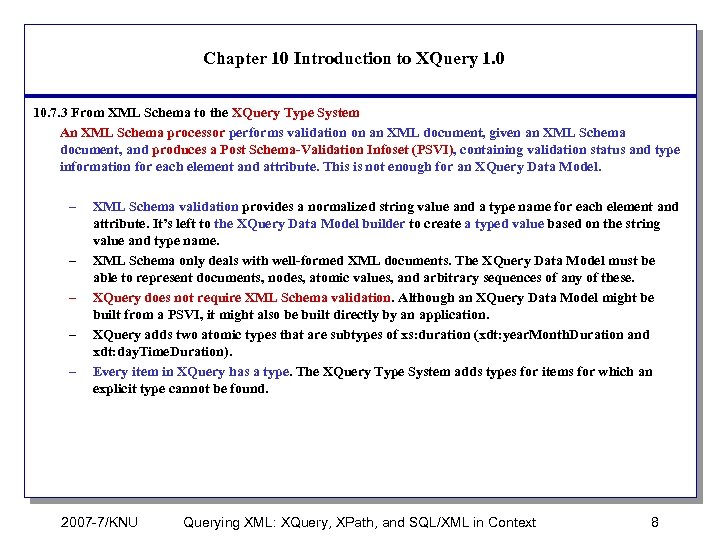

Chapter 10 Introduction to XQuery 1. 0 10. 7. 3 From XML Schema to the XQuery Type System An XML Schema processor performs validation on an XML document, given an XML Schema document, and produces a Post Schema-Validation Infoset (PSVI), containing validation status and type information for each element and attribute. This is not enough for an XQuery Data Model. – – – XML Schema validation provides a normalized string value and a type name for each element and attribute. It’s left to the XQuery Data Model builder to create a typed value based on the string value and type name. XML Schema only deals with well-formed XML documents. The XQuery Data Model must be able to represent documents, nodes, atomic values, and arbitrary sequences of any of these. XQuery does not require XML Schema validation. Although an XQuery Data Model might be built from a PSVI, it might also be built directly by an application. XQuery adds two atomic types that are subtypes of xs: duration (xdt: year. Month. Duration and xdt: day. Time. Duration). Every item in XQuery has a type. The XQuery Type System adds types for items for which an explicit type cannot be found. 2007 -7/KNU Querying XML: XQuery, XPath, and SQL/XML in Context 8

Chapter 10 Introduction to XQuery 1. 0 10. 7. 3 From XML Schema to the XQuery Type System An XML Schema processor performs validation on an XML document, given an XML Schema document, and produces a Post Schema-Validation Infoset (PSVI), containing validation status and type information for each element and attribute. This is not enough for an XQuery Data Model. – – – XML Schema validation provides a normalized string value and a type name for each element and attribute. It’s left to the XQuery Data Model builder to create a typed value based on the string value and type name. XML Schema only deals with well-formed XML documents. The XQuery Data Model must be able to represent documents, nodes, atomic values, and arbitrary sequences of any of these. XQuery does not require XML Schema validation. Although an XQuery Data Model might be built from a PSVI, it might also be built directly by an application. XQuery adds two atomic types that are subtypes of xs: duration (xdt: year. Month. Duration and xdt: day. Time. Duration). Every item in XQuery has a type. The XQuery Type System adds types for items for which an explicit type cannot be found. 2007 -7/KNU Querying XML: XQuery, XPath, and SQL/XML in Context 8

Chapter 10 Introduction to XQuery 1. 0 The XQuery Type System adds the following abstract types: – – – xdt: untyped – is a special type, meaning that no type information is available. xdt: untyped is a subtype of xs: any. Type, and it cannot be a base type for user-derived types. xdt: any. Atomic. Type – is a subtype of xs: any. Simple. Type. It is a little more restrictive than xs: sny. Simple. Type, encompassing all the subtypes of xs: any. Simple. Type except xs: IDREFS, xs: NMTOKENS, xs: ENTITIES, and user-defined list and union types. xdt: untyped. Atomic – if an item has this type, we know that it is an atomic value, but it has not been validated against an XML Schema. 10. 7. 4 Types and Queries We expect the XQuery Data Model and type system to be the foundation of all XML processing, not just XQuery, over time. 2007 -7/KNU Querying XML: XQuery, XPath, and SQL/XML in Context 9

Chapter 10 Introduction to XQuery 1. 0 The XQuery Type System adds the following abstract types: – – – xdt: untyped – is a special type, meaning that no type information is available. xdt: untyped is a subtype of xs: any. Type, and it cannot be a base type for user-derived types. xdt: any. Atomic. Type – is a subtype of xs: any. Simple. Type. It is a little more restrictive than xs: sny. Simple. Type, encompassing all the subtypes of xs: any. Simple. Type except xs: IDREFS, xs: NMTOKENS, xs: ENTITIES, and user-defined list and union types. xdt: untyped. Atomic – if an item has this type, we know that it is an atomic value, but it has not been validated against an XML Schema. 10. 7. 4 Types and Queries We expect the XQuery Data Model and type system to be the foundation of all XML processing, not just XQuery, over time. 2007 -7/KNU Querying XML: XQuery, XPath, and SQL/XML in Context 9

Chapter 10 Introduction to XQuery 1. 0 10. 8 XQuery 1. 0 Formal Semantics and Static Typing The Formal Semantics specification defines the static semantics of XQuery, particularly the rules for determining the static types of expressions. The Formal Semantics specification also defines most of the dynamic semantics of XQuery using the same sort of formal notation. The static type of an expression is a data type that is determinable without seeing any instance data on which the expression might be evaluated. In some languages, it is called the compiled type or the declared type of an expression. This is in contrast to the dynamic type, also known as the run-time type or the mostspecific type. Example 10 -7 An XQuery Expression let $i xs: integer : = 3 return $i + 5 2007 -7/KNU Querying XML: XQuery, XPath, and SQL/XML in Context 10

Chapter 10 Introduction to XQuery 1. 0 10. 8 XQuery 1. 0 Formal Semantics and Static Typing The Formal Semantics specification defines the static semantics of XQuery, particularly the rules for determining the static types of expressions. The Formal Semantics specification also defines most of the dynamic semantics of XQuery using the same sort of formal notation. The static type of an expression is a data type that is determinable without seeing any instance data on which the expression might be evaluated. In some languages, it is called the compiled type or the declared type of an expression. This is in contrast to the dynamic type, also known as the run-time type or the mostspecific type. Example 10 -7 An XQuery Expression let $i xs: integer : = 3 return $i + 5 2007 -7/KNU Querying XML: XQuery, XPath, and SQL/XML in Context 10

Chapter 10 Introduction to XQuery 1. 0 10. 8. 1 Notations This notation depends on the concepts of judgments, inference rules, and mapping rules. A judgment is a statement about whether some property holds (“is a fact”) or not. An inference rule states that some judgment holds if and only if other specified judgments also hold. A mapping rule describes how an ordinary XQuery expression is mapped onto a “core XQuery expression. ” (1) The symbol “=>” means “evaluates to”, (2) a colon (“: ”) separates an expression from a type name, and (3) the “turnstile” symbol (which should be “|-” but is simulated in the Formal Semantics spec by “|-” because of HTML and font limitations) separates the name of an environment from a judgment regarding something in that environment. In the Formal Semantics, an environment is a context in which objects can exist; XQuery’s static context and dynamic context are the environments used in the spec. Judgments don’t always use the symbols “=>” and “: ”. They are sometimes written using ordinary English words (“is” or “raises, ” for example). turnstile : 회전식 십자문, 회전식 개찰구 2007 -7/KNU Querying XML: XQuery, XPath, and SQL/XML in Context 11

Chapter 10 Introduction to XQuery 1. 0 10. 8. 1 Notations This notation depends on the concepts of judgments, inference rules, and mapping rules. A judgment is a statement about whether some property holds (“is a fact”) or not. An inference rule states that some judgment holds if and only if other specified judgments also hold. A mapping rule describes how an ordinary XQuery expression is mapped onto a “core XQuery expression. ” (1) The symbol “=>” means “evaluates to”, (2) a colon (“: ”) separates an expression from a type name, and (3) the “turnstile” symbol (which should be “|-” but is simulated in the Formal Semantics spec by “|-” because of HTML and font limitations) separates the name of an environment from a judgment regarding something in that environment. In the Formal Semantics, an environment is a context in which objects can exist; XQuery’s static context and dynamic context are the environments used in the spec. Judgments don’t always use the symbols “=>” and “: ”. They are sometimes written using ordinary English words (“is” or “raises, ” for example). turnstile : 회전식 십자문, 회전식 개찰구 2007 -7/KNU Querying XML: XQuery, XPath, and SQL/XML in Context 11

Chapter 10 Introduction to XQuery 1. 0 Example 10 -8 Sample Formal Semantics Judgments The following judgment holds? 3 => 3 Film is depressing Expr => Value movies/movie/release. Date = 1989 The following judgment holds if Expr has the type Type Expr : Type E. g. , Net. Movie[title=movies/movie/title]/price : xs: decimal The following judgment holds when Expr raises the error Expr raises Error E. g. , 15 div 0 raises err: FOAR 0001 The following judgment holds when, in the static environment stat. Env (that is, in the static context), an expression Expr has type Type stat. Env |- Expr : Type E. g. , in our sample data, the following judgment always holds stat. Env |- $DVDCost : xs: decimal 2007 -7/KNU Querying XML: XQuery, XPath, and SQL/XML in Context 12

Chapter 10 Introduction to XQuery 1. 0 Example 10 -8 Sample Formal Semantics Judgments The following judgment holds? 3 => 3 Film is depressing Expr => Value movies/movie/release. Date = 1989 The following judgment holds if Expr has the type Type Expr : Type E. g. , Net. Movie[title=movies/movie/title]/price : xs: decimal The following judgment holds when Expr raises the error Expr raises Error E. g. , 15 div 0 raises err: FOAR 0001 The following judgment holds when, in the static environment stat. Env (that is, in the static context), an expression Expr has type Type stat. Env |- Expr : Type E. g. , in our sample data, the following judgment always holds stat. Env |- $DVDCost : xs: decimal 2007 -7/KNU Querying XML: XQuery, XPath, and SQL/XML in Context 12

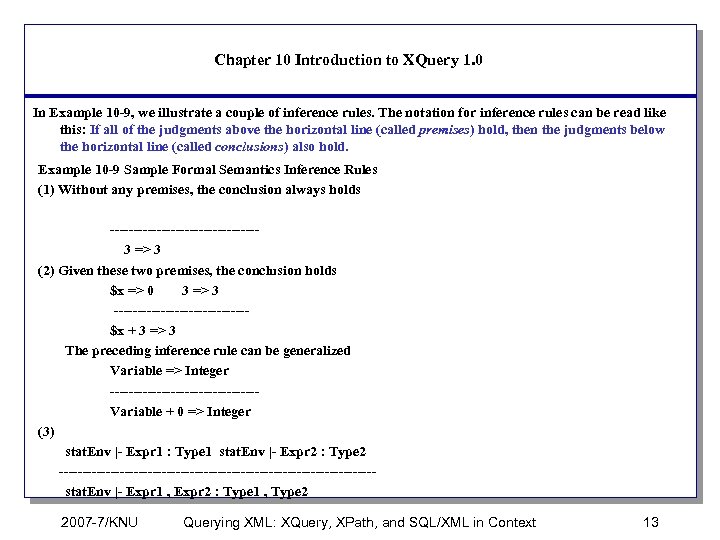

Chapter 10 Introduction to XQuery 1. 0 In Example 10 -9, we illustrate a couple of inference rules. The notation for inference rules can be read like this: If all of the judgments above the horizontal line (called premises) hold, then the judgments below the horizontal line (called conclusions) also hold. Example 10 -9 Sample Formal Semantics Inference Rules (1) Without any premises, the conclusion always holds ----------------3 => 3 (2) Given these two premises, the conclusion holds $x => 0 3 => 3 --------------$x + 3 => 3 The preceding inference rule can be generalized Variable => Integer ----------------Variable + 0 => Integer (3) stat. Env |- Expr 1 : Type 1 stat. Env |- Expr 2 : Type 2 ----------------------------------stat. Env |- Expr 1 , Expr 2 : Type 1 , Type 2 2007 -7/KNU Querying XML: XQuery, XPath, and SQL/XML in Context 13

Chapter 10 Introduction to XQuery 1. 0 In Example 10 -9, we illustrate a couple of inference rules. The notation for inference rules can be read like this: If all of the judgments above the horizontal line (called premises) hold, then the judgments below the horizontal line (called conclusions) also hold. Example 10 -9 Sample Formal Semantics Inference Rules (1) Without any premises, the conclusion always holds ----------------3 => 3 (2) Given these two premises, the conclusion holds $x => 0 3 => 3 --------------$x + 3 => 3 The preceding inference rule can be generalized Variable => Integer ----------------Variable + 0 => Integer (3) stat. Env |- Expr 1 : Type 1 stat. Env |- Expr 2 : Type 2 ----------------------------------stat. Env |- Expr 1 , Expr 2 : Type 1 , Type 2 2007 -7/KNU Querying XML: XQuery, XPath, and SQL/XML in Context 13

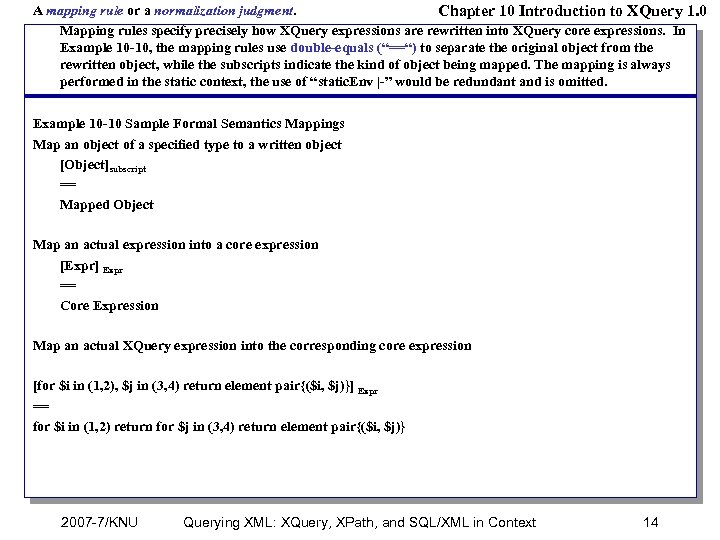

A mapping rule or a normalization judgment. Chapter 10 Introduction to XQuery 1. 0 Mapping rules specify precisely how XQuery expressions are rewritten into XQuery core expressions. In Example 10 -10, the mapping rules use double-equals (“==“) to separate the original object from the rewritten object, while the subscripts indicate the kind of object being mapped. The mapping is always performed in the static context, the use of “static. Env |-” would be redundant and is omitted. Example 10 -10 Sample Formal Semantics Mappings Map an object of a specified type to a written object [Object]subscript == Mapped Object Map an actual expression into a core expression [Expr] Expr == Core Expression Map an actual XQuery expression into the corresponding core expression [for $i in (1, 2), $j in (3, 4) return element pair{($i, $j)}] Expr == for $i in (1, 2) return for $j in (3, 4) return element pair{($i, $j)} 2007 -7/KNU Querying XML: XQuery, XPath, and SQL/XML in Context 14

A mapping rule or a normalization judgment. Chapter 10 Introduction to XQuery 1. 0 Mapping rules specify precisely how XQuery expressions are rewritten into XQuery core expressions. In Example 10 -10, the mapping rules use double-equals (“==“) to separate the original object from the rewritten object, while the subscripts indicate the kind of object being mapped. The mapping is always performed in the static context, the use of “static. Env |-” would be redundant and is omitted. Example 10 -10 Sample Formal Semantics Mappings Map an object of a specified type to a written object [Object]subscript == Mapped Object Map an actual expression into a core expression [Expr] Expr == Core Expression Map an actual XQuery expression into the corresponding core expression [for $i in (1, 2), $j in (3, 4) return element pair{($i, $j)}] Expr == for $i in (1, 2) return for $j in (3, 4) return element pair{($i, $j)} 2007 -7/KNU Querying XML: XQuery, XPath, and SQL/XML in Context 14

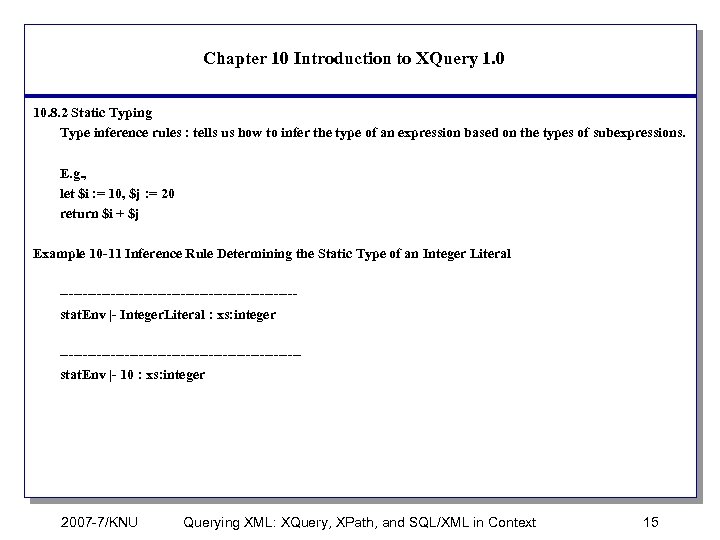

Chapter 10 Introduction to XQuery 1. 0 10. 8. 2 Static Typing Type inference rules : tells us how to infer the type of an expression based on the types of subexpressions. E. g. , let $i : = 10, $j : = 20 return $i + $j Example 10 -11 Inference Rule Determining the Static Type of an Integer Literal -------------------------stat. Env |- Integer. Literal : xs: integer --------------------------stat. Env |- 10 : xs: integer 2007 -7/KNU Querying XML: XQuery, XPath, and SQL/XML in Context 15

Chapter 10 Introduction to XQuery 1. 0 10. 8. 2 Static Typing Type inference rules : tells us how to infer the type of an expression based on the types of subexpressions. E. g. , let $i : = 10, $j : = 20 return $i + $j Example 10 -11 Inference Rule Determining the Static Type of an Integer Literal -------------------------stat. Env |- Integer. Literal : xs: integer --------------------------stat. Env |- 10 : xs: integer 2007 -7/KNU Querying XML: XQuery, XPath, and SQL/XML in Context 15

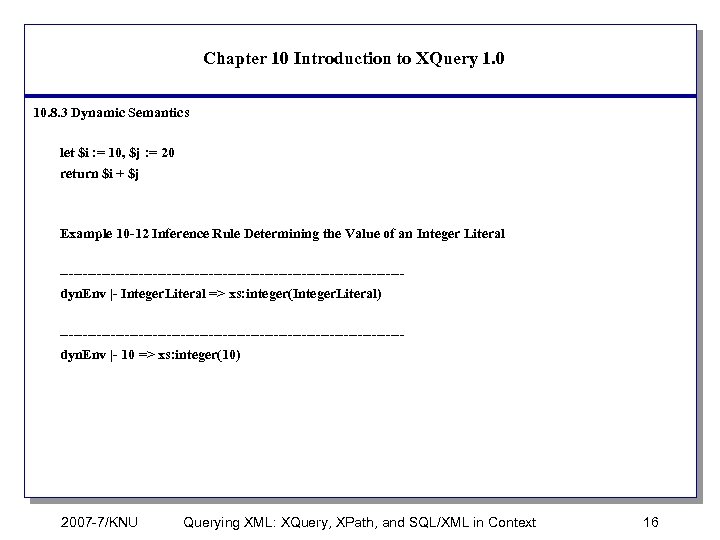

Chapter 10 Introduction to XQuery 1. 0 10. 8. 3 Dynamic Semantics let $i : = 10, $j : = 20 return $i + $j Example 10 -12 Inference Rule Determining the Value of an Integer Literal -------------------------------------dyn. Env |- Integer. Literal => xs: integer(Integer. Literal) -------------------------------------dyn. Env |- 10 => xs: integer(10) 2007 -7/KNU Querying XML: XQuery, XPath, and SQL/XML in Context 16

Chapter 10 Introduction to XQuery 1. 0 10. 8. 3 Dynamic Semantics let $i : = 10, $j : = 20 return $i + $j Example 10 -12 Inference Rule Determining the Value of an Integer Literal -------------------------------------dyn. Env |- Integer. Literal => xs: integer(Integer. Literal) -------------------------------------dyn. Env |- 10 => xs: integer(10) 2007 -7/KNU Querying XML: XQuery, XPath, and SQL/XML in Context 16

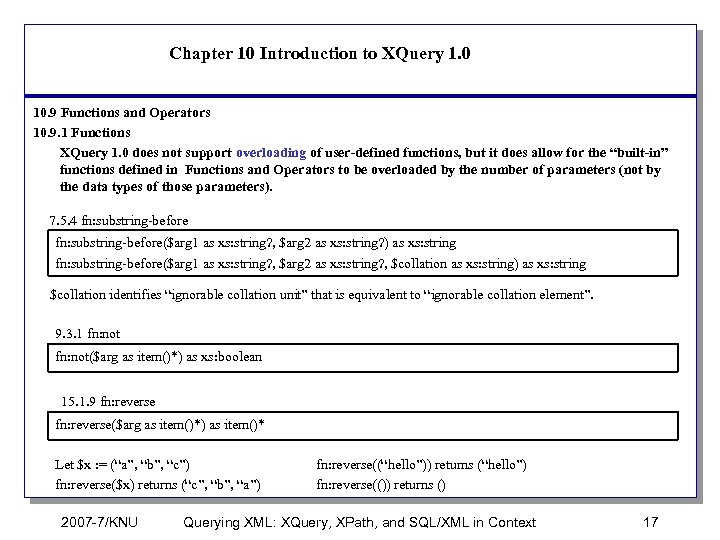

Chapter 10 Introduction to XQuery 1. 0 10. 9 Functions and Operators 10. 9. 1 Functions XQuery 1. 0 does not support overloading of user-defined functions, but it does allow for the “built-in” functions defined in Functions and Operators to be overloaded by the number of parameters (not by the data types of those parameters). 7. 5. 4 fn: substring-before($arg 1 as xs: string? , $arg 2 as xs: string? ) as xs: string fn: substring-before($arg 1 as xs: string? , $arg 2 as xs: string? , $collation as xs: string) as xs: string $collation identifies “ignorable collation unit” that is equivalent to “ignorable collation element”. 9. 3. 1 fn: not($arg as item()*) as xs: boolean 15. 1. 9 fn: reverse($arg as item()*) as item()* Let $x : = (“a”, “b”, “c”) fn: reverse($x) returns (“c”, “b”, “a”) 2007 -7/KNU fn: reverse((“hello”)) returns (“hello”) fn: reverse(()) returns () Querying XML: XQuery, XPath, and SQL/XML in Context 17

Chapter 10 Introduction to XQuery 1. 0 10. 9 Functions and Operators 10. 9. 1 Functions XQuery 1. 0 does not support overloading of user-defined functions, but it does allow for the “built-in” functions defined in Functions and Operators to be overloaded by the number of parameters (not by the data types of those parameters). 7. 5. 4 fn: substring-before($arg 1 as xs: string? , $arg 2 as xs: string? ) as xs: string fn: substring-before($arg 1 as xs: string? , $arg 2 as xs: string? , $collation as xs: string) as xs: string $collation identifies “ignorable collation unit” that is equivalent to “ignorable collation element”. 9. 3. 1 fn: not($arg as item()*) as xs: boolean 15. 1. 9 fn: reverse($arg as item()*) as item()* Let $x : = (“a”, “b”, “c”) fn: reverse($x) returns (“c”, “b”, “a”) 2007 -7/KNU fn: reverse((“hello”)) returns (“hello”) fn: reverse(()) returns () Querying XML: XQuery, XPath, and SQL/XML in Context 17

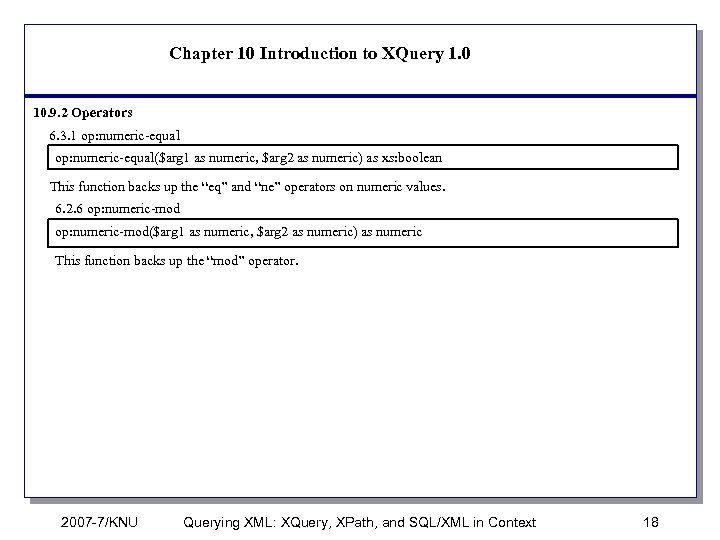

Chapter 10 Introduction to XQuery 1. 0 10. 9. 2 Operators 6. 3. 1 op: numeric-equal($arg 1 as numeric, $arg 2 as numeric) as xs: boolean This function backs up the “eq” and “ne” operators on numeric values. 6. 2. 6 op: numeric-mod($arg 1 as numeric, $arg 2 as numeric) as numeric This function backs up the “mod” operator. 2007 -7/KNU Querying XML: XQuery, XPath, and SQL/XML in Context 18

Chapter 10 Introduction to XQuery 1. 0 10. 9. 2 Operators 6. 3. 1 op: numeric-equal($arg 1 as numeric, $arg 2 as numeric) as xs: boolean This function backs up the “eq” and “ne” operators on numeric values. 6. 2. 6 op: numeric-mod($arg 1 as numeric, $arg 2 as numeric) as numeric This function backs up the “mod” operator. 2007 -7/KNU Querying XML: XQuery, XPath, and SQL/XML in Context 18

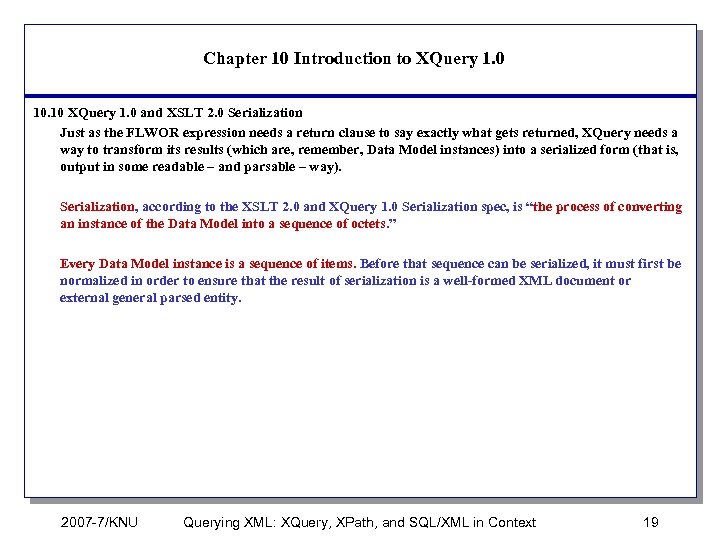

Chapter 10 Introduction to XQuery 1. 0 10. 10 XQuery 1. 0 and XSLT 2. 0 Serialization Just as the FLWOR expression needs a return clause to say exactly what gets returned, XQuery needs a way to transform its results (which are, remember, Data Model instances) into a serialized form (that is, output in some readable – and parsable – way). Serialization, according to the XSLT 2. 0 and XQuery 1. 0 Serialization spec, is “the process of converting an instance of the Data Model into a sequence of octets. ” Every Data Model instance is a sequence of items. Before that sequence can be serialized, it must first be normalized in order to ensure that the result of serialization is a well-formed XML document or external general parsed entity. 2007 -7/KNU Querying XML: XQuery, XPath, and SQL/XML in Context 19

Chapter 10 Introduction to XQuery 1. 0 10. 10 XQuery 1. 0 and XSLT 2. 0 Serialization Just as the FLWOR expression needs a return clause to say exactly what gets returned, XQuery needs a way to transform its results (which are, remember, Data Model instances) into a serialized form (that is, output in some readable – and parsable – way). Serialization, according to the XSLT 2. 0 and XQuery 1. 0 Serialization spec, is “the process of converting an instance of the Data Model into a sequence of octets. ” Every Data Model instance is a sequence of items. Before that sequence can be serialized, it must first be normalized in order to ensure that the result of serialization is a well-formed XML document or external general parsed entity. 2007 -7/KNU Querying XML: XQuery, XPath, and SQL/XML in Context 19

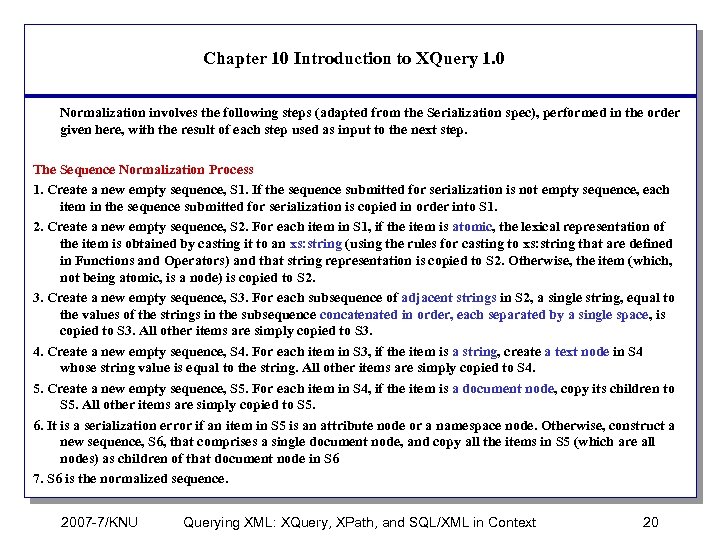

Chapter 10 Introduction to XQuery 1. 0 Normalization involves the following steps (adapted from the Serialization spec), performed in the order given here, with the result of each step used as input to the next step. The Sequence Normalization Process 1. Create a new empty sequence, S 1. If the sequence submitted for serialization is not empty sequence, each item in the sequence submitted for serialization is copied in order into S 1. 2. Create a new empty sequence, S 2. For each item in S 1, if the item is atomic, the lexical representation of the item is obtained by casting it to an xs: string (using the rules for casting to xs: string that are defined in Functions and Operators) and that string representation is copied to S 2. Otherwise, the item (which, not being atomic, is a node) is copied to S 2. 3. Create a new empty sequence, S 3. For each subsequence of adjacent strings in S 2, a single string, equal to the values of the strings in the subsequence concatenated in order, each separated by a single space, is copied to S 3. All other items are simply copied to S 3. 4. Create a new empty sequence, S 4. For each item in S 3, if the item is a string, create a text node in S 4 whose string value is equal to the string. All other items are simply copied to S 4. 5. Create a new empty sequence, S 5. For each item in S 4, if the item is a document node, copy its children to S 5. All other items are simply copied to S 5. 6. It is a serialization error if an item in S 5 is an attribute node or a namespace node. Otherwise, construct a new sequence, S 6, that comprises a single document node, and copy all the items in S 5 (which are all nodes) as children of that document node in S 6 7. S 6 is the normalized sequence. 2007 -7/KNU Querying XML: XQuery, XPath, and SQL/XML in Context 20

Chapter 10 Introduction to XQuery 1. 0 Normalization involves the following steps (adapted from the Serialization spec), performed in the order given here, with the result of each step used as input to the next step. The Sequence Normalization Process 1. Create a new empty sequence, S 1. If the sequence submitted for serialization is not empty sequence, each item in the sequence submitted for serialization is copied in order into S 1. 2. Create a new empty sequence, S 2. For each item in S 1, if the item is atomic, the lexical representation of the item is obtained by casting it to an xs: string (using the rules for casting to xs: string that are defined in Functions and Operators) and that string representation is copied to S 2. Otherwise, the item (which, not being atomic, is a node) is copied to S 2. 3. Create a new empty sequence, S 3. For each subsequence of adjacent strings in S 2, a single string, equal to the values of the strings in the subsequence concatenated in order, each separated by a single space, is copied to S 3. All other items are simply copied to S 3. 4. Create a new empty sequence, S 4. For each item in S 3, if the item is a string, create a text node in S 4 whose string value is equal to the string. All other items are simply copied to S 4. 5. Create a new empty sequence, S 5. For each item in S 4, if the item is a document node, copy its children to S 5. All other items are simply copied to S 5. 6. It is a serialization error if an item in S 5 is an attribute node or a namespace node. Otherwise, construct a new sequence, S 6, that comprises a single document node, and copy all the items in S 5 (which are all nodes) as children of that document node in S 6 7. S 6 is the normalized sequence. 2007 -7/KNU Querying XML: XQuery, XPath, and SQL/XML in Context 20

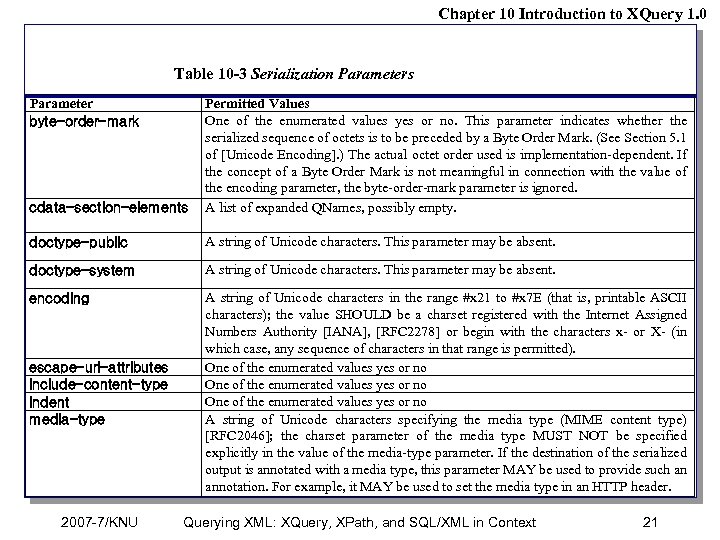

Chapter 10 Introduction to XQuery 1. 0 Table 10 -3 Serialization Parameters Parameter byte-order-mark cdata-section-elements Permitted Values One of the enumerated values yes or no. This parameter indicates whether the serialized sequence of octets is to be preceded by a Byte Order Mark. (See Section 5. 1 of [Unicode Encoding]. ) The actual octet order used is implementation-dependent. If the concept of a Byte Order Mark is not meaningful in connection with the value of the encoding parameter, the byte-order-mark parameter is ignored. A list of expanded QNames, possibly empty. doctype-public A string of Unicode characters. This parameter may be absent. doctype-system A string of Unicode characters. This parameter may be absent. encoding A string of Unicode characters in the range #x 21 to #x 7 E (that is, printable ASCII characters); the value SHOULD be a charset registered with the Internet Assigned Numbers Authority [IANA], [RFC 2278] or begin with the characters x- or X- (in which case, any sequence of characters in that range is permitted). One of the enumerated values yes or no A string of Unicode characters specifying the media type (MIME content type) [RFC 2046]; the charset parameter of the media type MUST NOT be specified explicitly in the value of the media-type parameter. If the destination of the serialized output is annotated with a media type, this parameter MAY be used to provide such an annotation. For example, it MAY be used to set the media type in an HTTP header. escape-uri-attributes include-content-type indent media-type 2007 -7/KNU Querying XML: XQuery, XPath, and SQL/XML in Context 21

Chapter 10 Introduction to XQuery 1. 0 Table 10 -3 Serialization Parameters Parameter byte-order-mark cdata-section-elements Permitted Values One of the enumerated values yes or no. This parameter indicates whether the serialized sequence of octets is to be preceded by a Byte Order Mark. (See Section 5. 1 of [Unicode Encoding]. ) The actual octet order used is implementation-dependent. If the concept of a Byte Order Mark is not meaningful in connection with the value of the encoding parameter, the byte-order-mark parameter is ignored. A list of expanded QNames, possibly empty. doctype-public A string of Unicode characters. This parameter may be absent. doctype-system A string of Unicode characters. This parameter may be absent. encoding A string of Unicode characters in the range #x 21 to #x 7 E (that is, printable ASCII characters); the value SHOULD be a charset registered with the Internet Assigned Numbers Authority [IANA], [RFC 2278] or begin with the characters x- or X- (in which case, any sequence of characters in that range is permitted). One of the enumerated values yes or no A string of Unicode characters specifying the media type (MIME content type) [RFC 2046]; the charset parameter of the media type MUST NOT be specified explicitly in the value of the media-type parameter. If the destination of the serialized output is annotated with a media type, this parameter MAY be used to provide such an annotation. For example, it MAY be used to set the media type in an HTTP header. escape-uri-attributes include-content-type indent media-type 2007 -7/KNU Querying XML: XQuery, XPath, and SQL/XML in Context 21

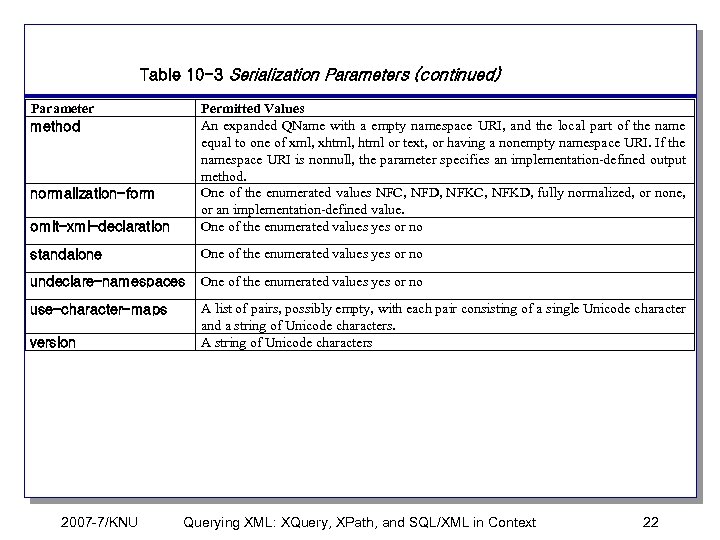

Table 10 -3 Serialization Parameters (continued) Parameter method omit-xml-declaration Permitted Values An expanded QName with a empty namespace URI, and the local part of the name equal to one of xml, xhtml, html or text, or having a nonempty namespace URI. If the namespace URI is nonnull, the parameter specifies an implementation-defined output method. One of the enumerated values NFC, NFD, NFKC, NFKD, fully normalized, or none, or an implementation-defined value. One of the enumerated values yes or no standalone One of the enumerated values yes or no undeclare-namespaces One of the enumerated values yes or no use-character-maps A list of pairs, possibly empty, with each pair consisting of a single Unicode character and a string of Unicode characters. A string of Unicode characters normalization-form version 2007 -7/KNU Querying XML: XQuery, XPath, and SQL/XML in Context 22

Table 10 -3 Serialization Parameters (continued) Parameter method omit-xml-declaration Permitted Values An expanded QName with a empty namespace URI, and the local part of the name equal to one of xml, xhtml, html or text, or having a nonempty namespace URI. If the namespace URI is nonnull, the parameter specifies an implementation-defined output method. One of the enumerated values NFC, NFD, NFKC, NFKD, fully normalized, or none, or an implementation-defined value. One of the enumerated values yes or no standalone One of the enumerated values yes or no undeclare-namespaces One of the enumerated values yes or no use-character-maps A list of pairs, possibly empty, with each pair consisting of a single Unicode character and a string of Unicode characters. A string of Unicode characters normalization-form version 2007 -7/KNU Querying XML: XQuery, XPath, and SQL/XML in Context 22

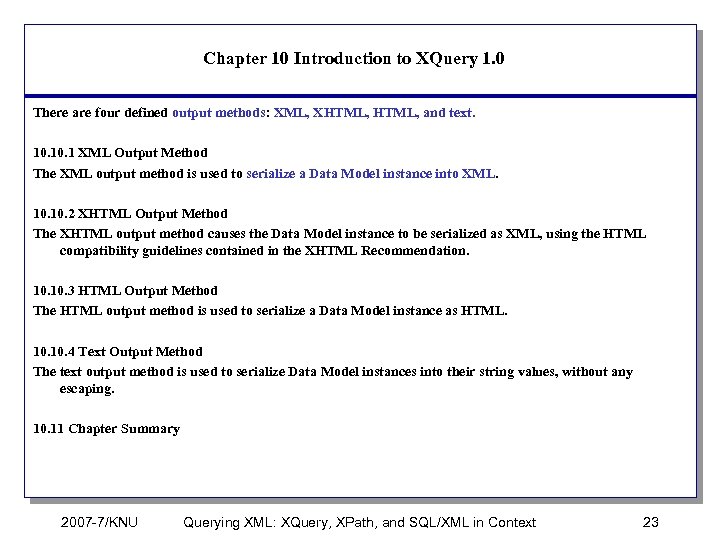

Chapter 10 Introduction to XQuery 1. 0 There are four defined output methods: XML, XHTML, and text. 10. 1 XML Output Method The XML output method is used to serialize a Data Model instance into XML. 10. 2 XHTML Output Method The XHTML output method causes the Data Model instance to be serialized as XML, using the HTML compatibility guidelines contained in the XHTML Recommendation. 10. 3 HTML Output Method The HTML output method is used to serialize a Data Model instance as HTML. 10. 4 Text Output Method The text output method is used to serialize Data Model instances into their string values, without any escaping. 10. 11 Chapter Summary 2007 -7/KNU Querying XML: XQuery, XPath, and SQL/XML in Context 23

Chapter 10 Introduction to XQuery 1. 0 There are four defined output methods: XML, XHTML, and text. 10. 1 XML Output Method The XML output method is used to serialize a Data Model instance into XML. 10. 2 XHTML Output Method The XHTML output method causes the Data Model instance to be serialized as XML, using the HTML compatibility guidelines contained in the XHTML Recommendation. 10. 3 HTML Output Method The HTML output method is used to serialize a Data Model instance as HTML. 10. 4 Text Output Method The text output method is used to serialize Data Model instances into their string values, without any escaping. 10. 11 Chapter Summary 2007 -7/KNU Querying XML: XQuery, XPath, and SQL/XML in Context 23

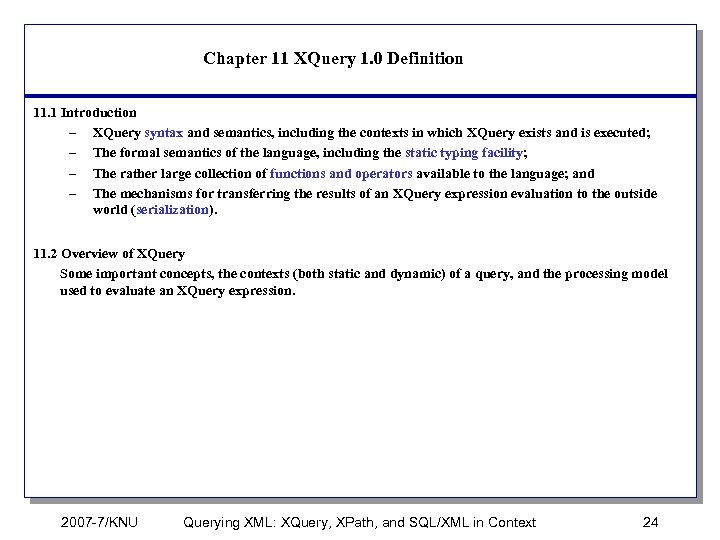

Chapter 11 XQuery 1. 0 Definition 11. 1 Introduction – XQuery syntax and semantics, including the contexts in which XQuery exists and is executed; – The formal semantics of the language, including the static typing facility; – The rather large collection of functions and operators available to the language; and – The mechanisms for transferring the results of an XQuery expression evaluation to the outside world (serialization). 11. 2 Overview of XQuery Some important concepts, the contexts (both static and dynamic) of a query, and the processing model used to evaluate an XQuery expression. 2007 -7/KNU Querying XML: XQuery, XPath, and SQL/XML in Context 24

Chapter 11 XQuery 1. 0 Definition 11. 1 Introduction – XQuery syntax and semantics, including the contexts in which XQuery exists and is executed; – The formal semantics of the language, including the static typing facility; – The rather large collection of functions and operators available to the language; and – The mechanisms for transferring the results of an XQuery expression evaluation to the outside world (serialization). 11. 2 Overview of XQuery Some important concepts, the contexts (both static and dynamic) of a query, and the processing model used to evaluate an XQuery expression. 2007 -7/KNU Querying XML: XQuery, XPath, and SQL/XML in Context 24

Chapter 11 XQuery 1. 0 Definition 11. 2. 1 Concepts n Document order – n Sequence – A sequence is an ordered collection of zero or more items. E. g. , (), (1, 2, 3, 4, 5), (3. 14159, 2. 71828, 0. 5772) n Atomization – Atomization is the result of invoking the fn: data() function on the sequence. That result is the sequence of atomic values produced by applying the following rules to each item in the input sequence: – If the item is an atomic value, it is returned. – If the item is a node, its typed value is returned (an error is raised if the node has no typed value). E. g. , Atomizing the sequence (

Chapter 11 XQuery 1. 0 Definition 11. 2. 1 Concepts n Document order – n Sequence – A sequence is an ordered collection of zero or more items. E. g. , (), (1, 2, 3, 4, 5), (3. 14159, 2. 71828, 0. 5772) n Atomization – Atomization is the result of invoking the fn: data() function on the sequence. That result is the sequence of atomic values produced by applying the following rules to each item in the input sequence: – If the item is an atomic value, it is returned. – If the item is a node, its typed value is returned (an error is raised if the node has no typed value). E. g. , Atomizing the sequence (

Chapter 11 XQuery 1. 0 Definition n Effective Boolean value (EBV) – The effective Boolean value of an expression is the result of invoking the fn: boolean() function on the value of expression. That result is a Boolean value produced by applying the following rules, in this order: – If its operand is an empty sequence, fn: boolean() returns false. – If its operand is a sequence whose first item is a node, fn: boolean() returns true. – If its operand is a singleton value of type xs: Boolean or derived from xs: boolean, fn: boolean() returns the value of its operand unchanged. – If its operand is a singleton value of type xs: string, xdt: untyped. Atomic, or a type derived from one of these, fn: boolean() returns false if the operand value has zero length and true otherwise. – If its operand is a singleton value of any numeric type or derived from a numeric type, fn: boolean() returns false if the operand value is Na. N or is numerically equal to zero and true otherwise. – In all other cases, fn: boolean() raises a type error. n String value – Every node has a string value. The string value of a node is a string and, formally, is the result of applying fn: string() to the node. n Typed value – Every node has a typed value. The typed value of a node is a sequence of atomic values and, formally, is the result of applying fn: data() to the node. 2007 -7/KNU Querying XML: XQuery, XPath, and SQL/XML in Context 26

Chapter 11 XQuery 1. 0 Definition n Effective Boolean value (EBV) – The effective Boolean value of an expression is the result of invoking the fn: boolean() function on the value of expression. That result is a Boolean value produced by applying the following rules, in this order: – If its operand is an empty sequence, fn: boolean() returns false. – If its operand is a sequence whose first item is a node, fn: boolean() returns true. – If its operand is a singleton value of type xs: Boolean or derived from xs: boolean, fn: boolean() returns the value of its operand unchanged. – If its operand is a singleton value of type xs: string, xdt: untyped. Atomic, or a type derived from one of these, fn: boolean() returns false if the operand value has zero length and true otherwise. – If its operand is a singleton value of any numeric type or derived from a numeric type, fn: boolean() returns false if the operand value is Na. N or is numerically equal to zero and true otherwise. – In all other cases, fn: boolean() raises a type error. n String value – Every node has a string value. The string value of a node is a string and, formally, is the result of applying fn: string() to the node. n Typed value – Every node has a typed value. The typed value of a node is a sequence of atomic values and, formally, is the result of applying fn: data() to the node. 2007 -7/KNU Querying XML: XQuery, XPath, and SQL/XML in Context 26

Chapter 11 XQuery 1. 0 Definition 11. 3 The XQuery Processing Model XQuery Processor XQuery Engine 2007 -7/KNU Querying XML: XQuery, XPath, and SQL/XML in Context 27

Chapter 11 XQuery 1. 0 Definition 11. 3 The XQuery Processing Model XQuery Processor XQuery Engine 2007 -7/KNU Querying XML: XQuery, XPath, and SQL/XML in Context 27

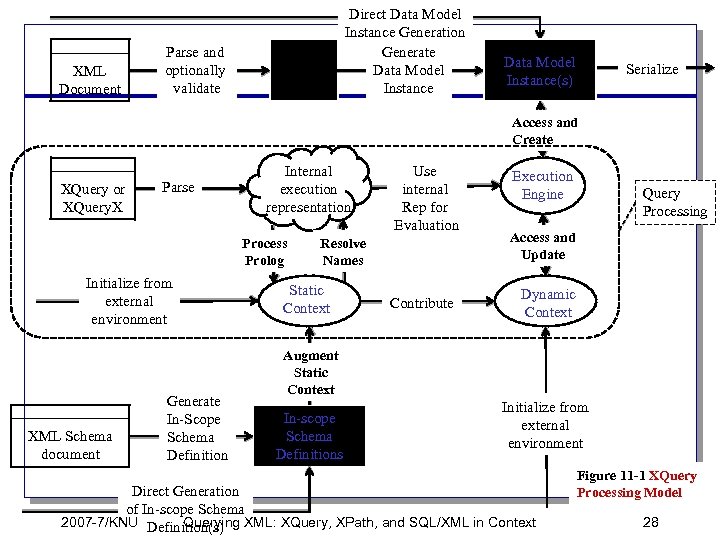

XML Document Parse and optionally validate Infoset or PSVI Direct Data Model Instance Generation Generate Data Model Instance(s) Serialize Access and Create XQuery or XQuery. X Parse Internal execution representation Process Prolog Initialize from external environment XML Schema document Generate In-Scope Schema Definition Use internal Rep for Evaluation Resolve Names Static Context Contribute Execution Engine Query Processing Access and Update Dynamic Context Augment Static Context In-scope Schema Definitions Initialize from external environment Direct Generation of In-scope Schema 2007 -7/KNU Definition(s) XML: XQuery, XPath, and SQL/XML in Context Querying Figure 11 -1 XQuery Processing Model 28

XML Document Parse and optionally validate Infoset or PSVI Direct Data Model Instance Generation Generate Data Model Instance(s) Serialize Access and Create XQuery or XQuery. X Parse Internal execution representation Process Prolog Initialize from external environment XML Schema document Generate In-Scope Schema Definition Use internal Rep for Evaluation Resolve Names Static Context Contribute Execution Engine Query Processing Access and Update Dynamic Context Augment Static Context In-scope Schema Definitions Initialize from external environment Direct Generation of In-scope Schema 2007 -7/KNU Definition(s) XML: XQuery, XPath, and SQL/XML in Context Querying Figure 11 -1 XQuery Processing Model 28

Chapter 11 XQuery 1. 0 Definition 11. 3. 1 The Static Context Whenever an XQuery expression is processed, the set of initial conditions governing its behavior is called the static context. The static context is a set of components, with values that are set globally by the XQuery implementation before any expression is evaluated. The values of a few of those components can be modified by the query prolog, and the values of a very few can be modified by the actions of the query itself. 2007 -7/KNU Querying XML: XQuery, XPath, and SQL/XML in Context 29

Chapter 11 XQuery 1. 0 Definition 11. 3. 1 The Static Context Whenever an XQuery expression is processed, the set of initial conditions governing its behavior is called the static context. The static context is a set of components, with values that are set globally by the XQuery implementation before any expression is evaluated. The values of a few of those components can be modified by the query prolog, and the values of a very few can be modified by the actions of the query itself. 2007 -7/KNU Querying XML: XQuery, XPath, and SQL/XML in Context 29

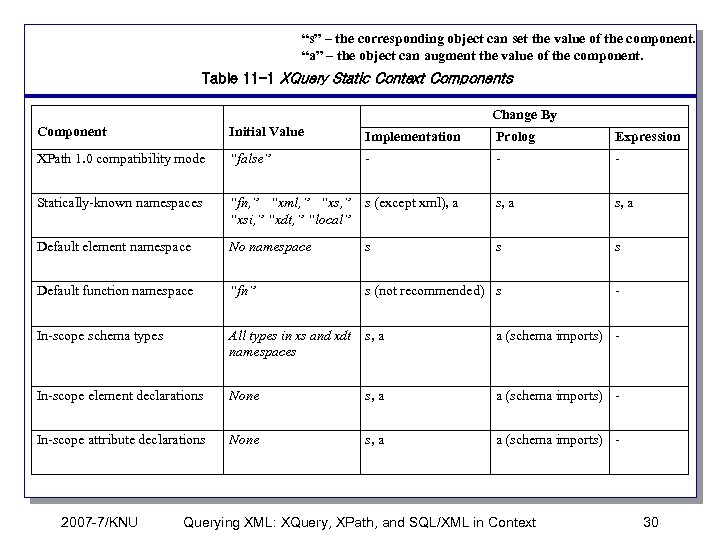

“s” – the corresponding object can set the value of the component. “a” – the object can augment the value of the component. Table 11 -1 XQuery Static Context Components Change By Component Initial Value Implementation Prolog Expression XPath 1. 0 compatibility mode “false” - - - Statically-known namespaces “fn, ” “xml, ” “xsi, ” “xdt, ” “local” s (except xml), a s, a Default element namespace No namespace s s s Default function namespace “fn” s (not recommended) s - In-scope schema types All types in xs and xdt namespaces s, a a (schema imports) - In-scope element declarations None s, a a (schema imports) - In-scope attribute declarations None s, a a (schema imports) - 2007 -7/KNU Querying XML: XQuery, XPath, and SQL/XML in Context 30

“s” – the corresponding object can set the value of the component. “a” – the object can augment the value of the component. Table 11 -1 XQuery Static Context Components Change By Component Initial Value Implementation Prolog Expression XPath 1. 0 compatibility mode “false” - - - Statically-known namespaces “fn, ” “xml, ” “xsi, ” “xdt, ” “local” s (except xml), a s, a Default element namespace No namespace s s s Default function namespace “fn” s (not recommended) s - In-scope schema types All types in xs and xdt namespaces s, a a (schema imports) - In-scope element declarations None s, a a (schema imports) - In-scope attribute declarations None s, a a (schema imports) - 2007 -7/KNU Querying XML: XQuery, XPath, and SQL/XML in Context 30

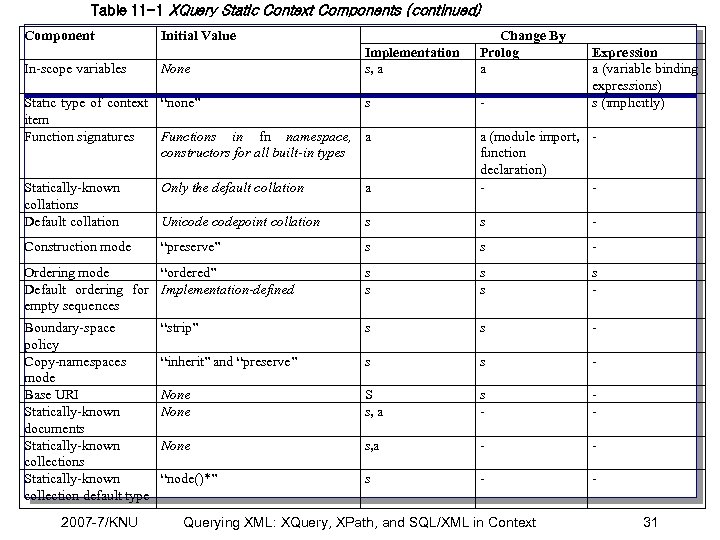

Table 11 -1 XQuery Static Context Components (continued) Component In-scope variables Initial Value None Implementation s, a Static type of context “none” s item Function signatures Functions in fn namespace, a constructors for all built-in types Change By Prolog a - Expression a (variable binding expressions) s (implicitly) Statically-known collations Default collation Only the default collation a a (module import, function declaration) - Unicodepoint collation s s - Construction mode “preserve” s s - Ordering mode “ordered” Default ordering for Implementation-defined empty sequences s s - Boundary-space policy Copy-namespaces mode Base URI Statically-known documents Statically-known collection default type “strip” s s - “inherit” and “preserve” s s - None S s, a s - - None s, a - - “node()*” s - - 2007 -7/KNU Querying XML: XQuery, XPath, and SQL/XML in Context 31

Table 11 -1 XQuery Static Context Components (continued) Component In-scope variables Initial Value None Implementation s, a Static type of context “none” s item Function signatures Functions in fn namespace, a constructors for all built-in types Change By Prolog a - Expression a (variable binding expressions) s (implicitly) Statically-known collations Default collation Only the default collation a a (module import, function declaration) - Unicodepoint collation s s - Construction mode “preserve” s s - Ordering mode “ordered” Default ordering for Implementation-defined empty sequences s s - Boundary-space policy Copy-namespaces mode Base URI Statically-known documents Statically-known collection default type “strip” s s - “inherit” and “preserve” s s - None S s, a s - - None s, a - - “node()*” s - - 2007 -7/KNU Querying XML: XQuery, XPath, and SQL/XML in Context 31

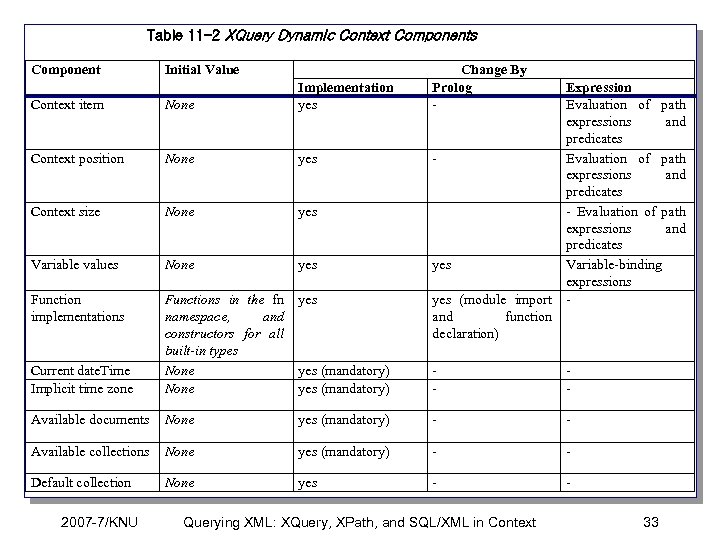

Chapter 11 XQuery 1. 0 Definition 11. 3. 2 The Dynamic Context The dynamic context represents aspects of the environment that may change during the evaluation of an XQuery or that might be changed by environmental factors other than the XQuery implementation itself. Some people, us included, view the static context as part of the dynamic context; others don’t. 2007 -7/KNU Querying XML: XQuery, XPath, and SQL/XML in Context 32

Chapter 11 XQuery 1. 0 Definition 11. 3. 2 The Dynamic Context The dynamic context represents aspects of the environment that may change during the evaluation of an XQuery or that might be changed by environmental factors other than the XQuery implementation itself. Some people, us included, view the static context as part of the dynamic context; others don’t. 2007 -7/KNU Querying XML: XQuery, XPath, and SQL/XML in Context 32

Table 11 -2 XQuery Dynamic Context Components Component Initial Value Change By Prolog - Context item None Implementation yes Context position None yes Context size None yes Variable values None yes Function implementations yes Current date. Time Implicit time zone Functions in the fn namespace, and constructors for all built-in types None yes (mandatory) - - Available documents None yes (mandatory) - - Available collections None yes (mandatory) - - Default collection None yes - - 2007 -7/KNU Expression Evaluation of path expressions and predicates - Evaluation of path expressions and predicates yes Variable-binding expressions yes (module import and function declaration) Querying XML: XQuery, XPath, and SQL/XML in Context 33

Table 11 -2 XQuery Dynamic Context Components Component Initial Value Change By Prolog - Context item None Implementation yes Context position None yes Context size None yes Variable values None yes Function implementations yes Current date. Time Implicit time zone Functions in the fn namespace, and constructors for all built-in types None yes (mandatory) - - Available documents None yes (mandatory) - - Available collections None yes (mandatory) - - Default collection None yes - - 2007 -7/KNU Expression Evaluation of path expressions and predicates - Evaluation of path expressions and predicates yes Variable-binding expressions yes (module import and function declaration) Querying XML: XQuery, XPath, and SQL/XML in Context 33

Chapter 11 XQuery 1. 0 Definition 11. 4 The XQuery Grammar Appendix C: XQuery 1. 0 Grammar contains the complete XQuery 1. 0 grammar in EBNF (Extended Backus-Nauer Form). XQuery’s comment syntax A comment is started with the sequence “(: ” and terminated with the sequence “: )”. Comments can be nested to any level, which means that “(: ” within a comment will be interpreted as the beginning of a nested comment. 2007 -7/KNU Querying XML: XQuery, XPath, and SQL/XML in Context 34

Chapter 11 XQuery 1. 0 Definition 11. 4 The XQuery Grammar Appendix C: XQuery 1. 0 Grammar contains the complete XQuery 1. 0 grammar in EBNF (Extended Backus-Nauer Form). XQuery’s comment syntax A comment is started with the sequence “(: ” and terminated with the sequence “: )”. Comments can be nested to any level, which means that “(: ” within a comment will be interpreted as the beginning of a nested comment. 2007 -7/KNU Querying XML: XQuery, XPath, and SQL/XML in Context 34

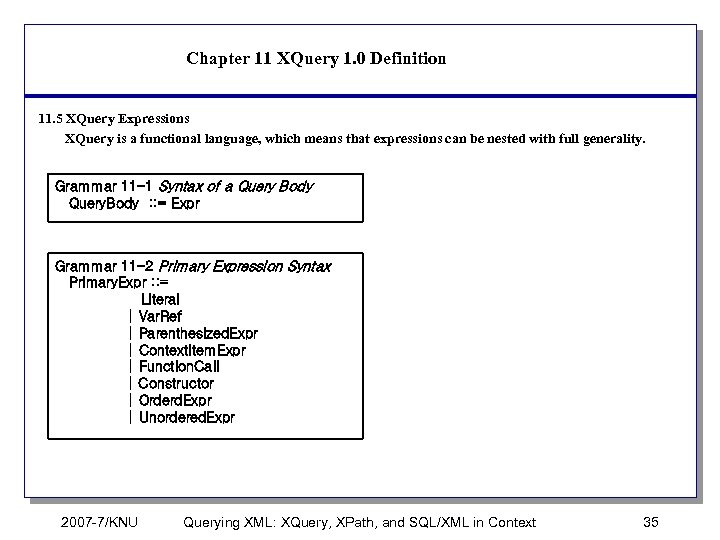

Chapter 11 XQuery 1. 0 Definition 11. 5 XQuery Expressions XQuery is a functional language, which means that expressions can be nested with full generality. Grammar 11 -1 Syntax of a Query Body Query. Body : : = Expr Grammar 11 -2 Primary Expression Syntax Primary. Expr : : = Literal | Var. Ref | Parenthesized. Expr | Context. Item. Expr | Function. Call | Constructor | Orderd. Expr | Unordered. Expr 2007 -7/KNU Querying XML: XQuery, XPath, and SQL/XML in Context 35

Chapter 11 XQuery 1. 0 Definition 11. 5 XQuery Expressions XQuery is a functional language, which means that expressions can be nested with full generality. Grammar 11 -1 Syntax of a Query Body Query. Body : : = Expr Grammar 11 -2 Primary Expression Syntax Primary. Expr : : = Literal | Var. Ref | Parenthesized. Expr | Context. Item. Expr | Function. Call | Constructor | Orderd. Expr | Unordered. Expr 2007 -7/KNU Querying XML: XQuery, XPath, and SQL/XML in Context 35

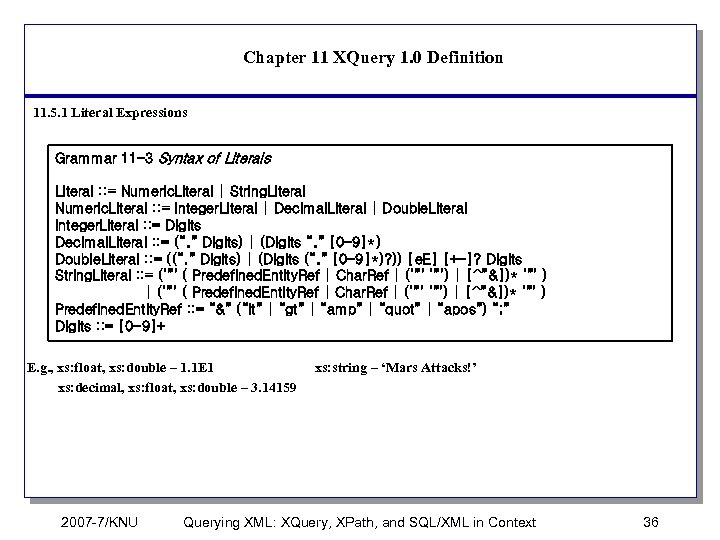

Chapter 11 XQuery 1. 0 Definition 11. 5. 1 Literal Expressions Grammar 11 -3 Syntax of Literals Literal : : = Numeric. Literal | String. Literal Numeric. Literal : : = Integer. Literal | Decimal. Literal | Double. Literal Integer. Literal : : = Digits Decimal. Literal : : = (“. ” Digits) | (Digits “. ” [0 -9]*) Double. Literal : : = ((“. ” Digits) | (Digits (“. ” [0 -9]*)? )) [e. E] [+-]? Digits String. Literal : : = (‘”’ ( Predefined. Entity. Ref | Char. Ref | (‘”’ ‘”’) | [^”&])* ‘”’ ) | (‘”’ ( Predefined. Entity. Ref | Char. Ref | (‘”’ ‘”’) | [^”&])* ‘”’ ) Predefined. Entity. Ref : : = “&” (“lt” | “gt” | “amp” | “quot” | “apos”) “; ” Digits : : = [0 -9]+ E. g. , xs: float, xs: double – 1. 1 E 1 xs: decimal, xs: float, xs: double – 3. 14159 2007 -7/KNU xs: string – ‘Mars Attacks!’ Querying XML: XQuery, XPath, and SQL/XML in Context 36

Chapter 11 XQuery 1. 0 Definition 11. 5. 1 Literal Expressions Grammar 11 -3 Syntax of Literals Literal : : = Numeric. Literal | String. Literal Numeric. Literal : : = Integer. Literal | Decimal. Literal | Double. Literal Integer. Literal : : = Digits Decimal. Literal : : = (“. ” Digits) | (Digits “. ” [0 -9]*) Double. Literal : : = ((“. ” Digits) | (Digits (“. ” [0 -9]*)? )) [e. E] [+-]? Digits String. Literal : : = (‘”’ ( Predefined. Entity. Ref | Char. Ref | (‘”’ ‘”’) | [^”&])* ‘”’ ) | (‘”’ ( Predefined. Entity. Ref | Char. Ref | (‘”’ ‘”’) | [^”&])* ‘”’ ) Predefined. Entity. Ref : : = “&” (“lt” | “gt” | “amp” | “quot” | “apos”) “; ” Digits : : = [0 -9]+ E. g. , xs: float, xs: double – 1. 1 E 1 xs: decimal, xs: float, xs: double – 3. 14159 2007 -7/KNU xs: string – ‘Mars Attacks!’ Querying XML: XQuery, XPath, and SQL/XML in Context 36

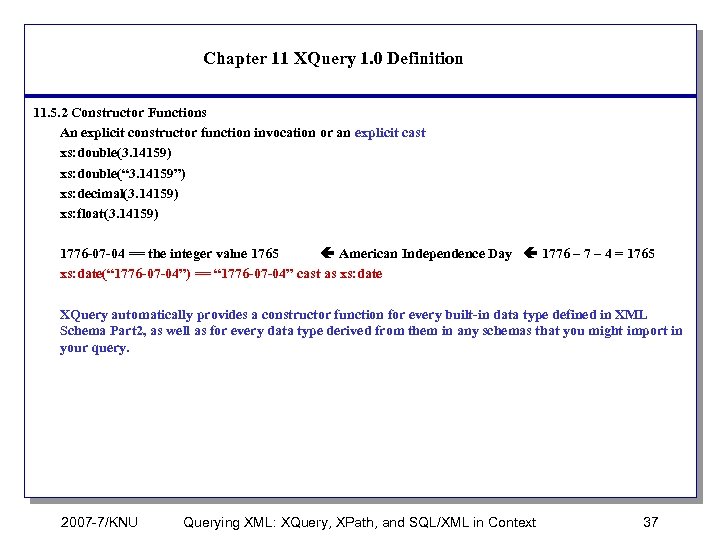

Chapter 11 XQuery 1. 0 Definition 11. 5. 2 Constructor Functions An explicit constructor function invocation or an explicit cast xs: double(3. 14159) xs: double(“ 3. 14159”) xs: decimal(3. 14159) xs: float(3. 14159) 1776 -07 -04 == the integer value 1765 American Independence Day 1776 – 7 – 4 = 1765 xs: date(“ 1776 -07 -04”) == “ 1776 -07 -04” cast as xs: date XQuery automatically provides a constructor function for every built-in data type defined in XML Schema Part 2, as well as for every data type derived from them in any schemas that you might import in your query. 2007 -7/KNU Querying XML: XQuery, XPath, and SQL/XML in Context 37

Chapter 11 XQuery 1. 0 Definition 11. 5. 2 Constructor Functions An explicit constructor function invocation or an explicit cast xs: double(3. 14159) xs: double(“ 3. 14159”) xs: decimal(3. 14159) xs: float(3. 14159) 1776 -07 -04 == the integer value 1765 American Independence Day 1776 – 7 – 4 = 1765 xs: date(“ 1776 -07 -04”) == “ 1776 -07 -04” cast as xs: date XQuery automatically provides a constructor function for every built-in data type defined in XML Schema Part 2, as well as for every data type derived from them in any schemas that you might import in your query. 2007 -7/KNU Querying XML: XQuery, XPath, and SQL/XML in Context 37

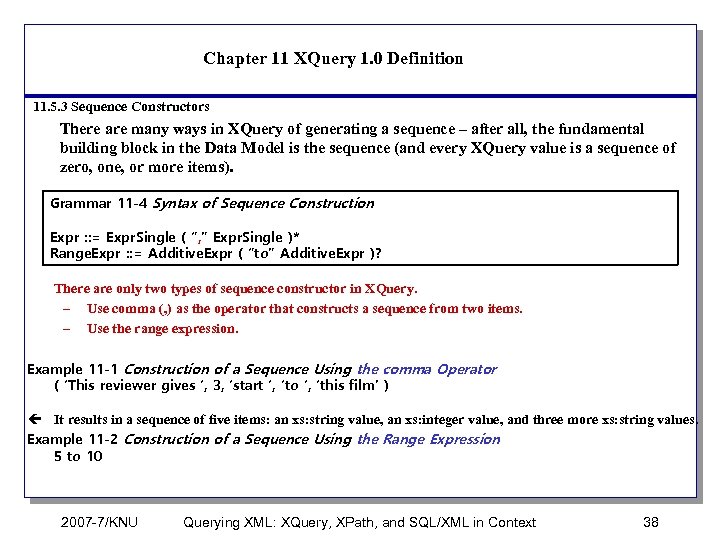

Chapter 11 XQuery 1. 0 Definition 11. 5. 3 Sequence Constructors There are many ways in XQuery of generating a sequence – after all, the fundamental building block in the Data Model is the sequence (and every XQuery value is a sequence of zero, one, or more items). Grammar 11 -4 Syntax of Sequence Construction Expr : : = Expr. Single ( “, ” Expr. Single )* Range. Expr : : = Additive. Expr ( “to” Additive. Expr )? There are only two types of sequence constructor in XQuery. – Use comma (, ) as the operator that constructs a sequence from two items. – Use the range expression. Example 11 -1 Construction of a Sequence Using the comma Operator ( ‘This reviewer gives ‘, 3, ‘start ‘, ‘to ‘, ‘this film’ ) It results in a sequence of five items: an xs: string value, an xs: integer value, and three more xs: string values. Example 11 -2 Construction of a Sequence Using the Range Expression 5 to 10 2007 -7/KNU Querying XML: XQuery, XPath, and SQL/XML in Context 38

Chapter 11 XQuery 1. 0 Definition 11. 5. 3 Sequence Constructors There are many ways in XQuery of generating a sequence – after all, the fundamental building block in the Data Model is the sequence (and every XQuery value is a sequence of zero, one, or more items). Grammar 11 -4 Syntax of Sequence Construction Expr : : = Expr. Single ( “, ” Expr. Single )* Range. Expr : : = Additive. Expr ( “to” Additive. Expr )? There are only two types of sequence constructor in XQuery. – Use comma (, ) as the operator that constructs a sequence from two items. – Use the range expression. Example 11 -1 Construction of a Sequence Using the comma Operator ( ‘This reviewer gives ‘, 3, ‘start ‘, ‘to ‘, ‘this film’ ) It results in a sequence of five items: an xs: string value, an xs: integer value, and three more xs: string values. Example 11 -2 Construction of a Sequence Using the Range Expression 5 to 10 2007 -7/KNU Querying XML: XQuery, XPath, and SQL/XML in Context 38

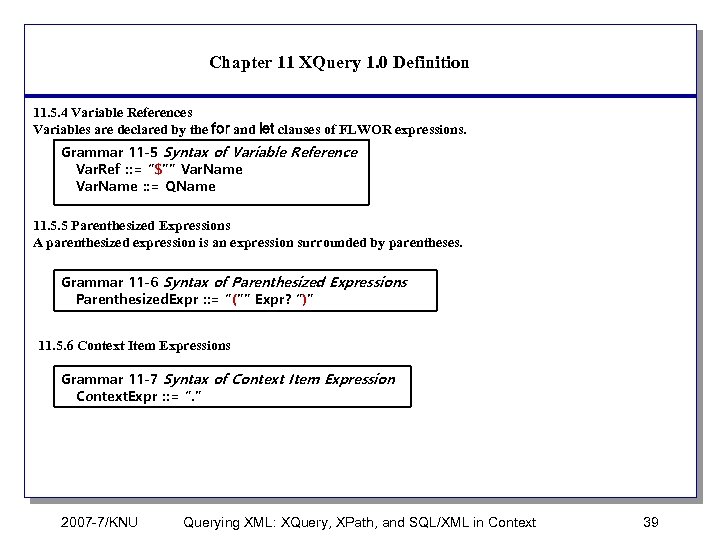

Chapter 11 XQuery 1. 0 Definition 11. 5. 4 Variable References Variables are declared by the for and let clauses of FLWOR expressions. Grammar 11 -5 Syntax of Variable Reference Var. Ref : : = “$”” Var. Name : : = QName 11. 5. 5 Parenthesized Expressions A parenthesized expression is an expression surrounded by parentheses. Grammar 11 -6 Syntax of Parenthesized Expressions Parenthesized. Expr : : = “(”” Expr? “)” 11. 5. 6 Context Item Expressions Grammar 11 -7 Syntax of Context Item Expression Context. Expr : : = “. ” 2007 -7/KNU Querying XML: XQuery, XPath, and SQL/XML in Context 39

Chapter 11 XQuery 1. 0 Definition 11. 5. 4 Variable References Variables are declared by the for and let clauses of FLWOR expressions. Grammar 11 -5 Syntax of Variable Reference Var. Ref : : = “$”” Var. Name : : = QName 11. 5. 5 Parenthesized Expressions A parenthesized expression is an expression surrounded by parentheses. Grammar 11 -6 Syntax of Parenthesized Expressions Parenthesized. Expr : : = “(”” Expr? “)” 11. 5. 6 Context Item Expressions Grammar 11 -7 Syntax of Context Item Expression Context. Expr : : = “. ” 2007 -7/KNU Querying XML: XQuery, XPath, and SQL/XML in Context 39

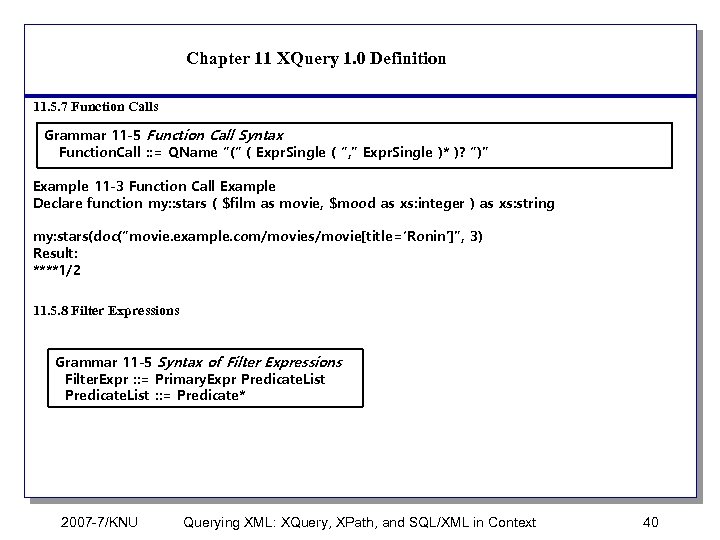

Chapter 11 XQuery 1. 0 Definition 11. 5. 7 Function Calls Grammar 11 -5 Function Call Syntax Function. Call : : = QName “(“ ( Expr. Single ( “, ” Expr. Single )* )? “)” Example 11 -3 Function Call Example Declare function my: : stars ( $film as movie, $mood as xs: integer ) as xs: string my: stars(doc(“movie. example. com/movies/movie[title=‘Ronin’]”, 3) Result: ****1/2 11. 5. 8 Filter Expressions Grammar 11 -5 Syntax of Filter Expressions Filter. Expr : : = Primary. Expr Predicate. List : : = Predicate* 2007 -7/KNU Querying XML: XQuery, XPath, and SQL/XML in Context 40

Chapter 11 XQuery 1. 0 Definition 11. 5. 7 Function Calls Grammar 11 -5 Function Call Syntax Function. Call : : = QName “(“ ( Expr. Single ( “, ” Expr. Single )* )? “)” Example 11 -3 Function Call Example Declare function my: : stars ( $film as movie, $mood as xs: integer ) as xs: string my: stars(doc(“movie. example. com/movies/movie[title=‘Ronin’]”, 3) Result: ****1/2 11. 5. 8 Filter Expressions Grammar 11 -5 Syntax of Filter Expressions Filter. Expr : : = Primary. Expr Predicate. List : : = Predicate* 2007 -7/KNU Querying XML: XQuery, XPath, and SQL/XML in Context 40

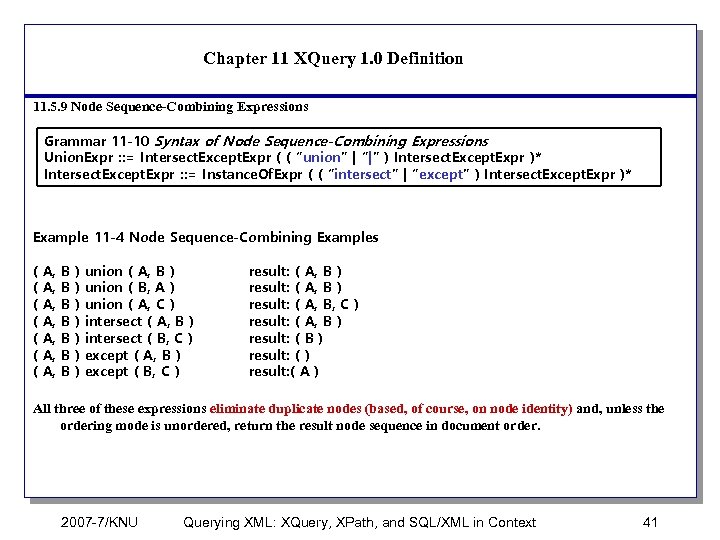

Chapter 11 XQuery 1. 0 Definition 11. 5. 9 Node Sequence-Combining Expressions Grammar 11 -10 Syntax of Node Sequence-Combining Expressions Union. Expr : : = Intersect. Except. Expr ( ( “union” | “|” ) Intersect. Except. Expr )* Intersect. Except. Expr : : = Instance. Of. Expr ( ( “intersect” | “except” ) Intersect. Except. Expr )* Example 11 -4 Node Sequence-Combining Examples ( ( ( ( A, A, B B B B ) ) ) ) union ( A, B ) union ( B, A ) union ( A, C ) intersect ( A, B ) intersect ( B, C ) except ( A, B ) except ( B, C ) result: ( A, B, C ) result: ( A, B ) result: ( A ) All three of these expressions eliminate duplicate nodes (based, of course, on node identity) and, unless the ordering mode is unordered, return the result node sequence in document order. 2007 -7/KNU Querying XML: XQuery, XPath, and SQL/XML in Context 41

Chapter 11 XQuery 1. 0 Definition 11. 5. 9 Node Sequence-Combining Expressions Grammar 11 -10 Syntax of Node Sequence-Combining Expressions Union. Expr : : = Intersect. Except. Expr ( ( “union” | “|” ) Intersect. Except. Expr )* Intersect. Except. Expr : : = Instance. Of. Expr ( ( “intersect” | “except” ) Intersect. Except. Expr )* Example 11 -4 Node Sequence-Combining Examples ( ( ( ( A, A, B B B B ) ) ) ) union ( A, B ) union ( B, A ) union ( A, C ) intersect ( A, B ) intersect ( B, C ) except ( A, B ) except ( B, C ) result: ( A, B, C ) result: ( A, B ) result: ( A ) All three of these expressions eliminate duplicate nodes (based, of course, on node identity) and, unless the ordering mode is unordered, return the result node sequence in document order. 2007 -7/KNU Querying XML: XQuery, XPath, and SQL/XML in Context 41

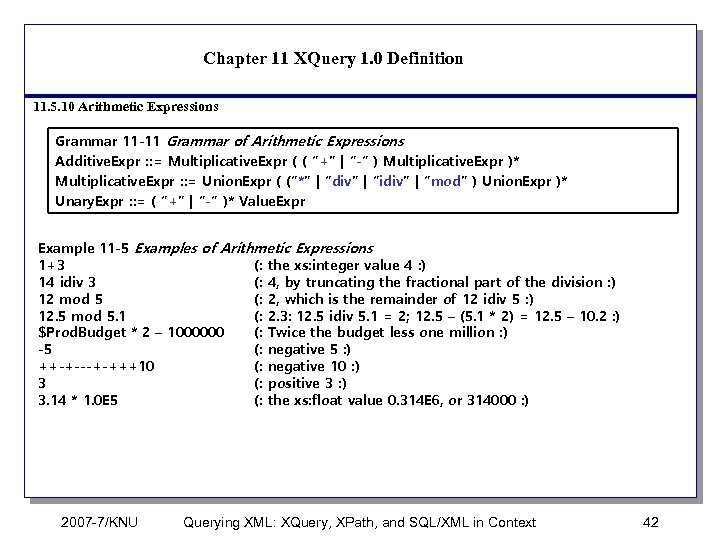

Chapter 11 XQuery 1. 0 Definition 11. 5. 10 Arithmetic Expressions Grammar 11 -11 Grammar of Arithmetic Expressions Additive. Expr : : = Multiplicative. Expr ( ( “+” | “-“ ) Multiplicative. Expr )* Multiplicative. Expr : : = Union. Expr ( (“*” | “div” | “idiv” | “mod” ) Union. Expr )* Unary. Expr : : = ( “+” | “-“ )* Value. Expr Example 11 -5 Examples of Arithmetic Expressions 1+3 (: the xs: integer value 4 : ) 14 idiv 3 (: 4, by truncating the fractional part of the division : ) 12 mod 5 (: 2, which is the remainder of 12 idiv 5 : ) 12. 5 mod 5. 1 (: 2. 3: 12. 5 idiv 5. 1 = 2; 12. 5 – (5. 1 * 2) = 12. 5 – 10. 2 : ) $Prod. Budget * 2 – 1000000 (: Twice the budget less one million : ) -5 (: negative 5 : ) ++-+---+-+++10 (: negative 10 : ) 3 (: positive 3 : ) 3. 14 * 1. 0 E 5 (: the xs: float value 0. 314 E 6, or 314000 : ) 2007 -7/KNU Querying XML: XQuery, XPath, and SQL/XML in Context 42

Chapter 11 XQuery 1. 0 Definition 11. 5. 10 Arithmetic Expressions Grammar 11 -11 Grammar of Arithmetic Expressions Additive. Expr : : = Multiplicative. Expr ( ( “+” | “-“ ) Multiplicative. Expr )* Multiplicative. Expr : : = Union. Expr ( (“*” | “div” | “idiv” | “mod” ) Union. Expr )* Unary. Expr : : = ( “+” | “-“ )* Value. Expr Example 11 -5 Examples of Arithmetic Expressions 1+3 (: the xs: integer value 4 : ) 14 idiv 3 (: 4, by truncating the fractional part of the division : ) 12 mod 5 (: 2, which is the remainder of 12 idiv 5 : ) 12. 5 mod 5. 1 (: 2. 3: 12. 5 idiv 5. 1 = 2; 12. 5 – (5. 1 * 2) = 12. 5 – 10. 2 : ) $Prod. Budget * 2 – 1000000 (: Twice the budget less one million : ) -5 (: negative 5 : ) ++-+---+-+++10 (: negative 10 : ) 3 (: positive 3 : ) 3. 14 * 1. 0 E 5 (: the xs: float value 0. 314 E 6, or 314000 : ) 2007 -7/KNU Querying XML: XQuery, XPath, and SQL/XML in Context 42

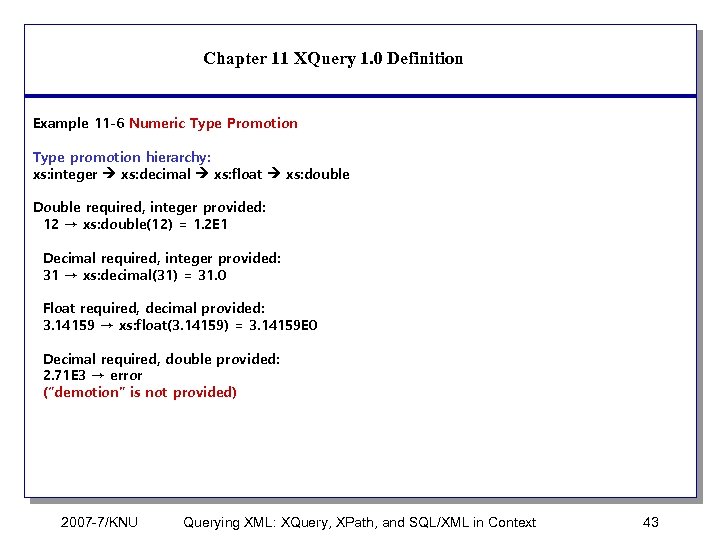

Chapter 11 XQuery 1. 0 Definition Example 11 -6 Numeric Type Promotion Type promotion hierarchy: xs: integer xs: decimal xs: float xs: double Double required, integer provided: 12 → xs: double(12) = 1. 2 E 1 Decimal required, integer provided: 31 → xs: decimal(31) = 31. 0 Float required, decimal provided: 3. 14159 → xs: float(3. 14159) = 3. 14159 E 0 Decimal required, double provided: 2. 71 E 3 → error (“demotion” is not provided) 2007 -7/KNU Querying XML: XQuery, XPath, and SQL/XML in Context 43

Chapter 11 XQuery 1. 0 Definition Example 11 -6 Numeric Type Promotion Type promotion hierarchy: xs: integer xs: decimal xs: float xs: double Double required, integer provided: 12 → xs: double(12) = 1. 2 E 1 Decimal required, integer provided: 31 → xs: decimal(31) = 31. 0 Float required, decimal provided: 3. 14159 → xs: float(3. 14159) = 3. 14159 E 0 Decimal required, double provided: 2. 71 E 3 → error (“demotion” is not provided) 2007 -7/KNU Querying XML: XQuery, XPath, and SQL/XML in Context 43

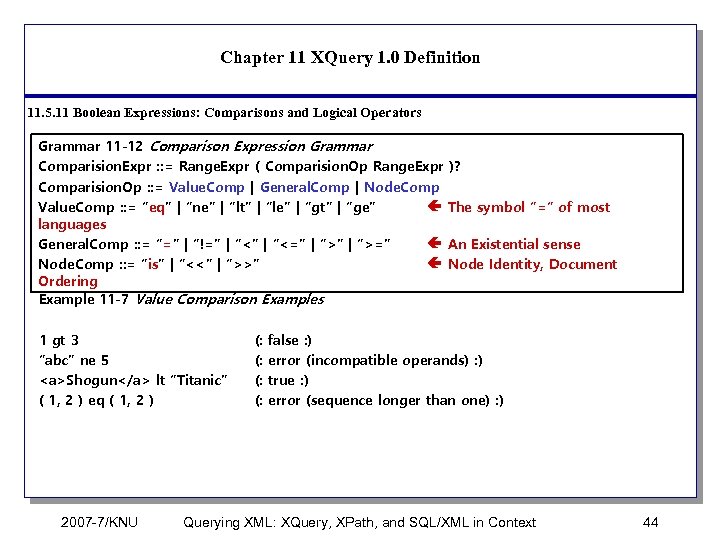

Chapter 11 XQuery 1. 0 Definition 11. 5. 11 Boolean Expressions: Comparisons and Logical Operators Grammar 11 -12 Comparison Expression Grammar Comparision. Expr : : = Range. Expr ( Comparision. Op Range. Expr )? Comparision. Op : : = Value. Comp | General. Comp | Node. Comp Value. Comp : : = “eq” | “ne” | “lt” | “le” | “gt” | “ge” The symbol “=“ of most languages General. Comp : : = “=” | “!=” | “<=” | “>=” An Existential sense Node. Comp : : = “is” | “<<” | “>>” Node Identity, Document Ordering Example 11 -7 Value Comparison Examples 1 gt 3 “abc” ne 5 Shogun lt “Titanic” ( 1, 2 ) eq ( 1, 2 ) 2007 -7/KNU (: (: false : ) error (incompatible operands) : ) true : ) error (sequence longer than one) : ) Querying XML: XQuery, XPath, and SQL/XML in Context 44

Chapter 11 XQuery 1. 0 Definition 11. 5. 11 Boolean Expressions: Comparisons and Logical Operators Grammar 11 -12 Comparison Expression Grammar Comparision. Expr : : = Range. Expr ( Comparision. Op Range. Expr )? Comparision. Op : : = Value. Comp | General. Comp | Node. Comp Value. Comp : : = “eq” | “ne” | “lt” | “le” | “gt” | “ge” The symbol “=“ of most languages General. Comp : : = “=” | “!=” | “<=” | “>=” An Existential sense Node. Comp : : = “is” | “<<” | “>>” Node Identity, Document Ordering Example 11 -7 Value Comparison Examples 1 gt 3 “abc” ne 5 Shogun lt “Titanic” ( 1, 2 ) eq ( 1, 2 ) 2007 -7/KNU (: (: false : ) error (incompatible operands) : ) true : ) error (sequence longer than one) : ) Querying XML: XQuery, XPath, and SQL/XML in Context 44

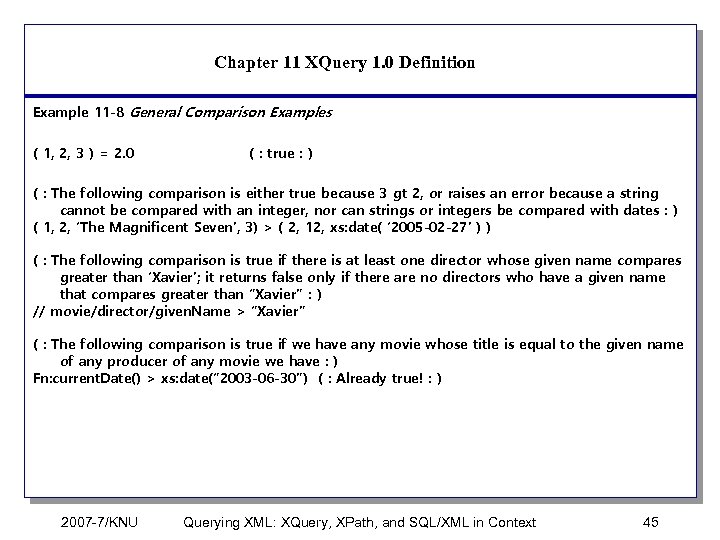

Chapter 11 XQuery 1. 0 Definition Example 11 -8 General Comparison Examples ( 1, 2, 3 ) = 2. 0 ( : true : ) ( : The following comparison is either true because 3 gt 2, or raises an error because a string cannot be compared with an integer, nor can strings or integers be compared with dates : ) ( 1, 2, ‘The Magnificent Seven’, 3) > ( 2, 12, xs: date( ‘ 2005 -02 -27’ ) ) ( : The following comparison is true if there is at least one director whose given name compares greater than ‘Xavier’; it returns false only if there are no directors who have a given name that compares greater than “Xavier” : ) // movie/director/given. Name > “Xavier” ( : The following comparison is true if we have any movie whose title is equal to the given name of any producer of any movie we have : ) Fn: current. Date() > xs: date(“ 2003 -06 -30”) ( : Already true! : ) 2007 -7/KNU Querying XML: XQuery, XPath, and SQL/XML in Context 45

Chapter 11 XQuery 1. 0 Definition Example 11 -8 General Comparison Examples ( 1, 2, 3 ) = 2. 0 ( : true : ) ( : The following comparison is either true because 3 gt 2, or raises an error because a string cannot be compared with an integer, nor can strings or integers be compared with dates : ) ( 1, 2, ‘The Magnificent Seven’, 3) > ( 2, 12, xs: date( ‘ 2005 -02 -27’ ) ) ( : The following comparison is true if there is at least one director whose given name compares greater than ‘Xavier’; it returns false only if there are no directors who have a given name that compares greater than “Xavier” : ) // movie/director/given. Name > “Xavier” ( : The following comparison is true if we have any movie whose title is equal to the given name of any producer of any movie we have : ) Fn: current. Date() > xs: date(“ 2003 -06 -30”) ( : Already true! : ) 2007 -7/KNU Querying XML: XQuery, XPath, and SQL/XML in Context 45

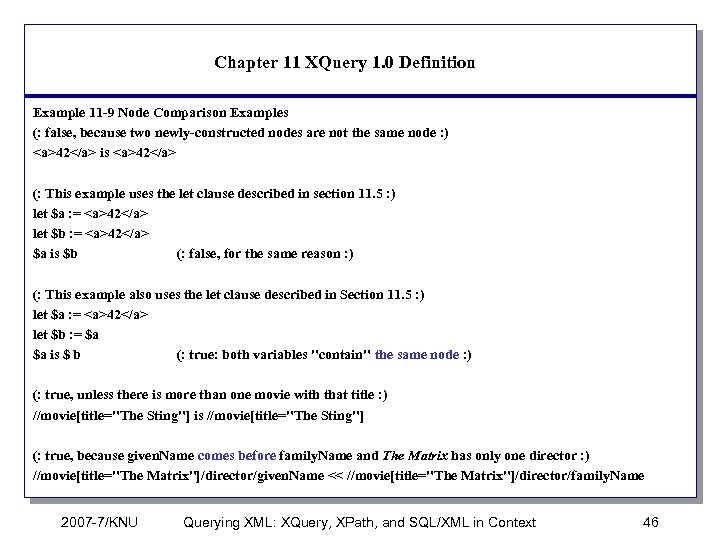

Chapter 11 XQuery 1. 0 Definition Example 11 -9 Node Comparison Examples (: false, because two newly-constructed nodes are not the same node : ) 42 is 42 (: This example uses the let clause described in section 11. 5 : ) let $a : = 42 let $b : = 42 $a is $b (: false, for the same reason : ) (: This example also uses the let clause described in Section 11. 5 : ) let $a : = 42 let $b : = $a $a is $ b (: true: both variables "contain" the same node : ) (: true, unless there is more than one movie with that title : ) //movie[title="The Sting"] is //movie[title="The Sting"] (: true, because given. Name comes before family. Name and The Matrix has only one director : ) //movie[title="The Matrix"]/director/given. Name << //movie[title="The Matrix"]/director/family. Name 2007 -7/KNU Querying XML: XQuery, XPath, and SQL/XML in Context 46

Chapter 11 XQuery 1. 0 Definition Example 11 -9 Node Comparison Examples (: false, because two newly-constructed nodes are not the same node : ) 42 is 42 (: This example uses the let clause described in section 11. 5 : ) let $a : = 42 let $b : = 42 $a is $b (: false, for the same reason : ) (: This example also uses the let clause described in Section 11. 5 : ) let $a : = 42 let $b : = $a $a is $ b (: true: both variables "contain" the same node : ) (: true, unless there is more than one movie with that title : ) //movie[title="The Sting"] is //movie[title="The Sting"] (: true, because given. Name comes before family. Name and The Matrix has only one director : ) //movie[title="The Matrix"]/director/given. Name << //movie[title="The Matrix"]/director/family. Name 2007 -7/KNU Querying XML: XQuery, XPath, and SQL/XML in Context 46

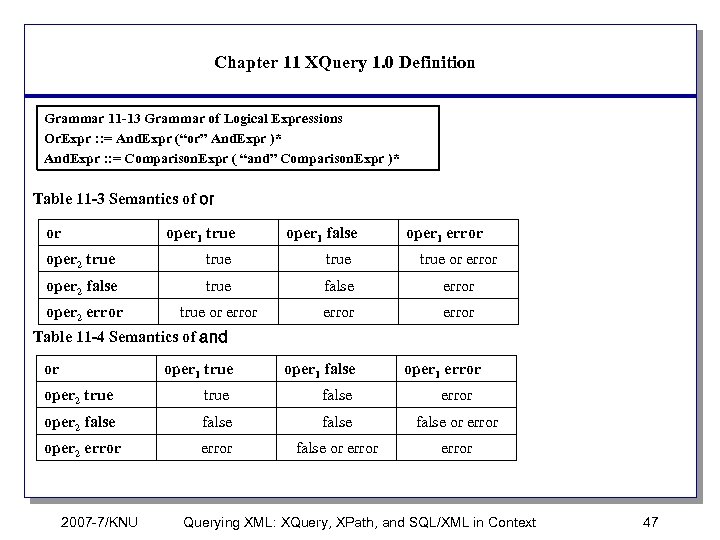

Chapter 11 XQuery 1. 0 Definition Grammar 11 -13 Grammar of Logical Expressions Or. Expr : : = And. Expr (“or” And. Expr )* And. Expr : : = Comparison. Expr ( “and” Comparison. Expr )* Table 11 -3 Semantics of or or oper 1 true oper 1 false oper 1 error oper 2 true or error oper 2 false true false error oper 2 error true or error Table 11 -4 Semantics of and or oper 1 true oper 1 false oper 2 true false error oper 2 false or error oper 2 error false or error 2007 -7/KNU oper 1 error Querying XML: XQuery, XPath, and SQL/XML in Context 47

Chapter 11 XQuery 1. 0 Definition Grammar 11 -13 Grammar of Logical Expressions Or. Expr : : = And. Expr (“or” And. Expr )* And. Expr : : = Comparison. Expr ( “and” Comparison. Expr )* Table 11 -3 Semantics of or or oper 1 true oper 1 false oper 1 error oper 2 true or error oper 2 false true false error oper 2 error true or error Table 11 -4 Semantics of and or oper 1 true oper 1 false oper 2 true false error oper 2 false or error oper 2 error false or error 2007 -7/KNU oper 1 error Querying XML: XQuery, XPath, and SQL/XML in Context 47

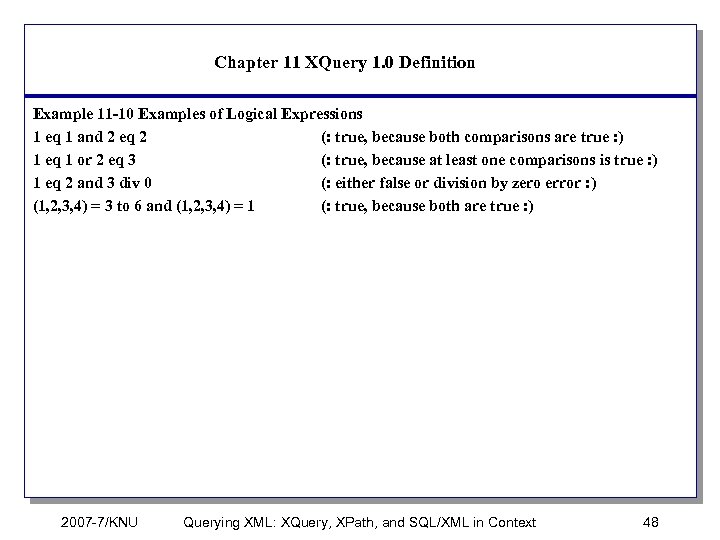

Chapter 11 XQuery 1. 0 Definition Example 11 -10 Examples of Logical Expressions 1 eq 1 and 2 eq 2 (: true, because both comparisons are true : ) 1 eq 1 or 2 eq 3 (: true, because at least one comparisons is true : ) 1 eq 2 and 3 div 0 (: either false or division by zero error : ) (1, 2, 3, 4) = 3 to 6 and (1, 2, 3, 4) = 1 (: true, because both are true : ) 2007 -7/KNU Querying XML: XQuery, XPath, and SQL/XML in Context 48

Chapter 11 XQuery 1. 0 Definition Example 11 -10 Examples of Logical Expressions 1 eq 1 and 2 eq 2 (: true, because both comparisons are true : ) 1 eq 1 or 2 eq 3 (: true, because at least one comparisons is true : ) 1 eq 2 and 3 div 0 (: either false or division by zero error : ) (1, 2, 3, 4) = 3 to 6 and (1, 2, 3, 4) = 1 (: true, because both are true : ) 2007 -7/KNU Querying XML: XQuery, XPath, and SQL/XML in Context 48

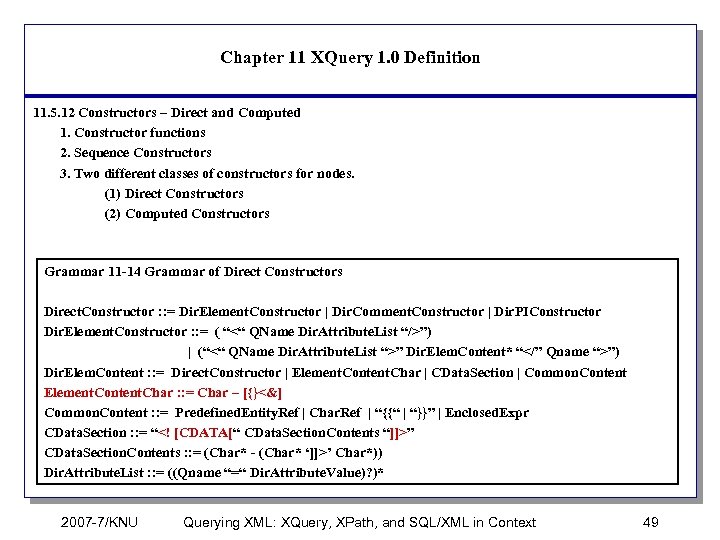

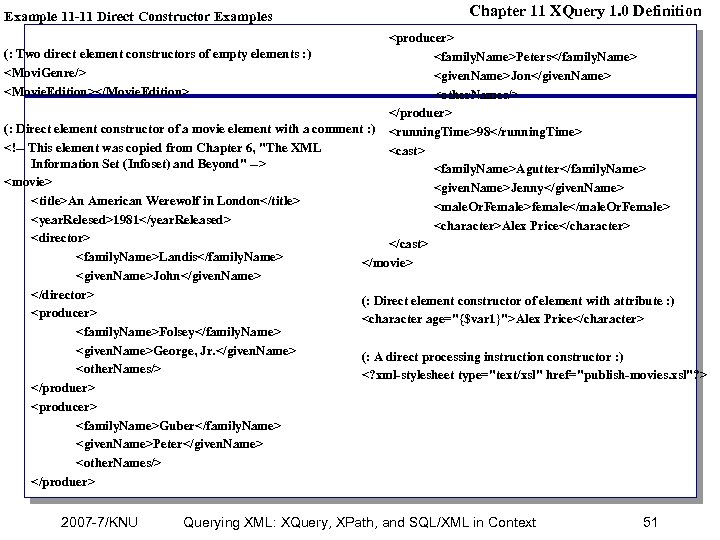

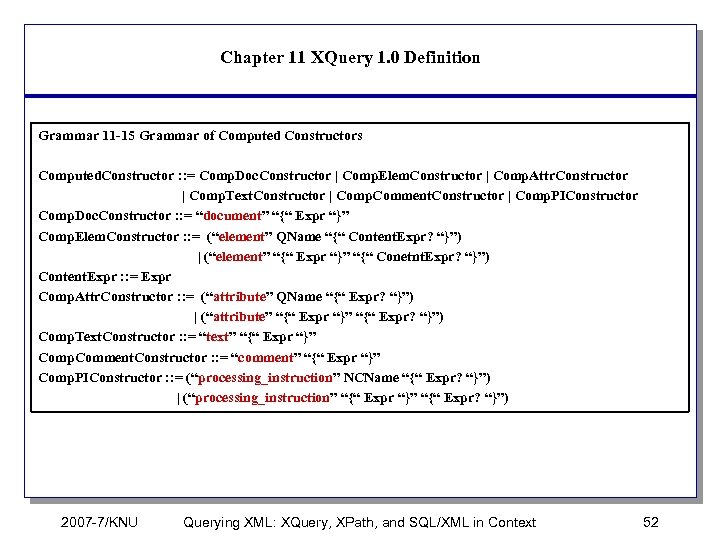

Chapter 11 XQuery 1. 0 Definition 11. 5. 12 Constructors – Direct and Computed 1. Constructor functions 2. Sequence Constructors 3. Two different classes of constructors for nodes. (1) Direct Constructors (2) Computed Constructors Grammar 11 -14 Grammar of Direct Constructors Direct. Constructor : : = Dir. Element. Constructor | Dir. Comment. Constructor | Dir. PIConstructor Dir. Element. Constructor : : = ( “<“ QName Dir. Attribute. List “/>”) | (“<“ QName Dir. Attribute. List “>” Dir. Elem. Content* “”) Dir. Elem. Content : : = Direct. Constructor | Element. Content. Char | CData. Section | Common. Content Element. Content. Char : : = Char – [{}<&] Common. Content : : = Predefined. Entity. Ref | Char. Ref | “{{“ | “}}” | Enclosed. Expr CData. Section : : = “” CData. Section. Contents : : = (Char* - (Char* ‘]]>’ Char*)) Dir. Attribute. List : : = ((Qname “=“ Dir. Attribute. Value)? )* 2007 -7/KNU Querying XML: XQuery, XPath, and SQL/XML in Context 49

Chapter 11 XQuery 1. 0 Definition 11. 5. 12 Constructors – Direct and Computed 1. Constructor functions 2. Sequence Constructors 3. Two different classes of constructors for nodes. (1) Direct Constructors (2) Computed Constructors Grammar 11 -14 Grammar of Direct Constructors Direct. Constructor : : = Dir. Element. Constructor | Dir. Comment. Constructor | Dir. PIConstructor Dir. Element. Constructor : : = ( “<“ QName Dir. Attribute. List “/>”) | (“<“ QName Dir. Attribute. List “>” Dir. Elem. Content* “”) Dir. Elem. Content : : = Direct. Constructor | Element. Content. Char | CData. Section | Common. Content Element. Content. Char : : = Char – [{}<&] Common. Content : : = Predefined. Entity. Ref | Char. Ref | “{{“ | “}}” | Enclosed. Expr CData. Section : : = “” CData. Section. Contents : : = (Char* - (Char* ‘]]>’ Char*)) Dir. Attribute. List : : = ((Qname “=“ Dir. Attribute. Value)? )* 2007 -7/KNU Querying XML: XQuery, XPath, and SQL/XML in Context 49

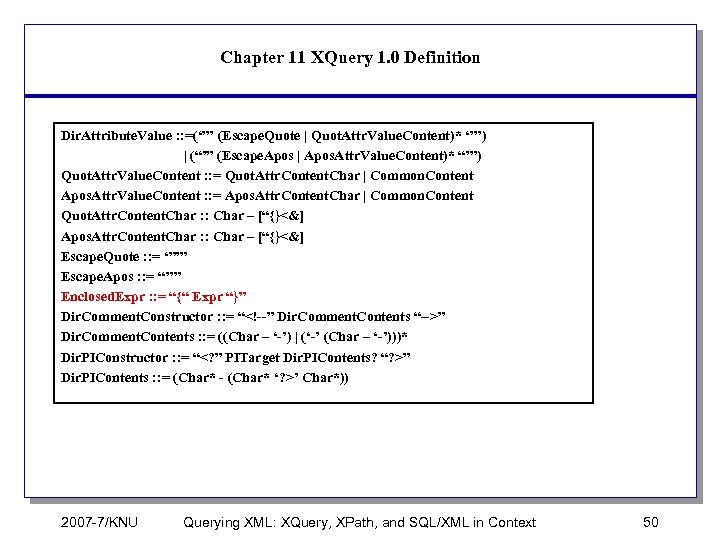

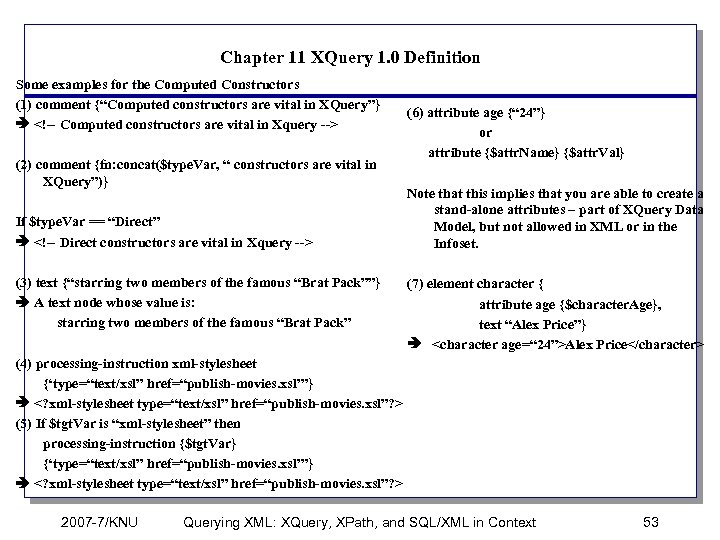

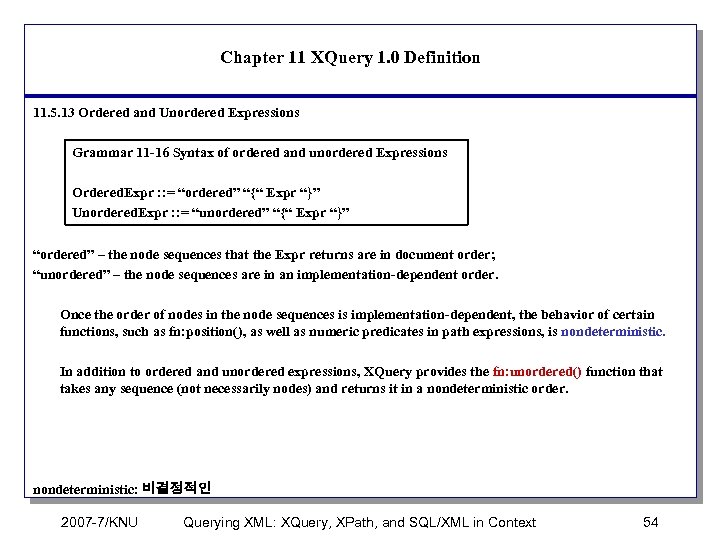

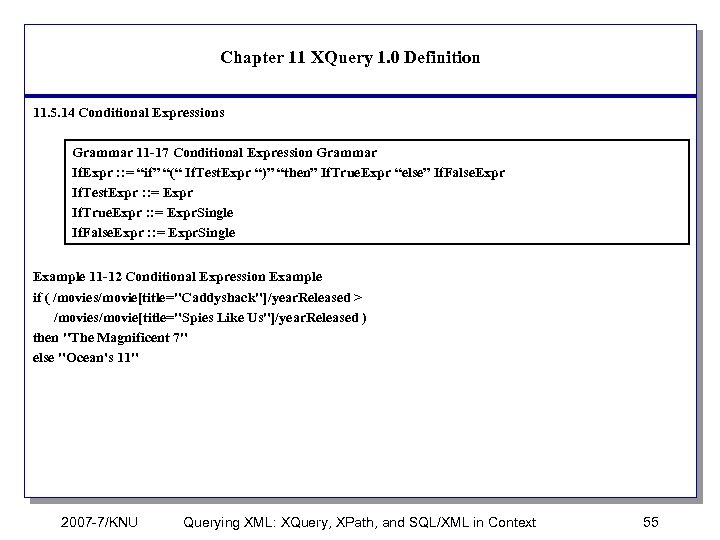

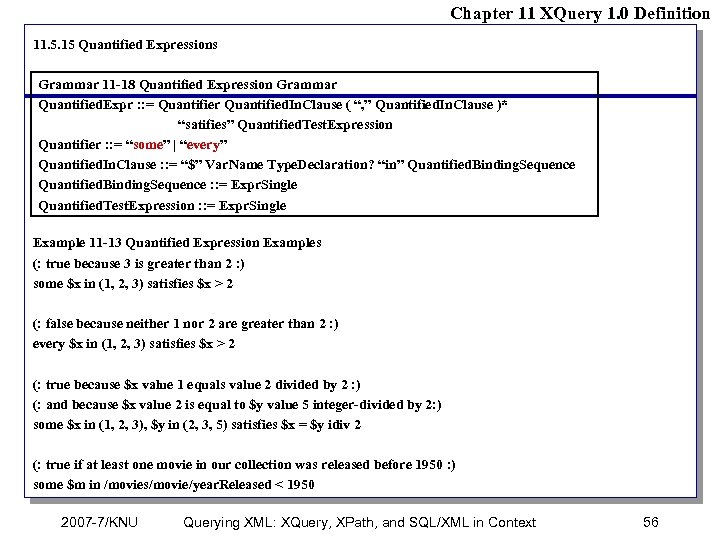

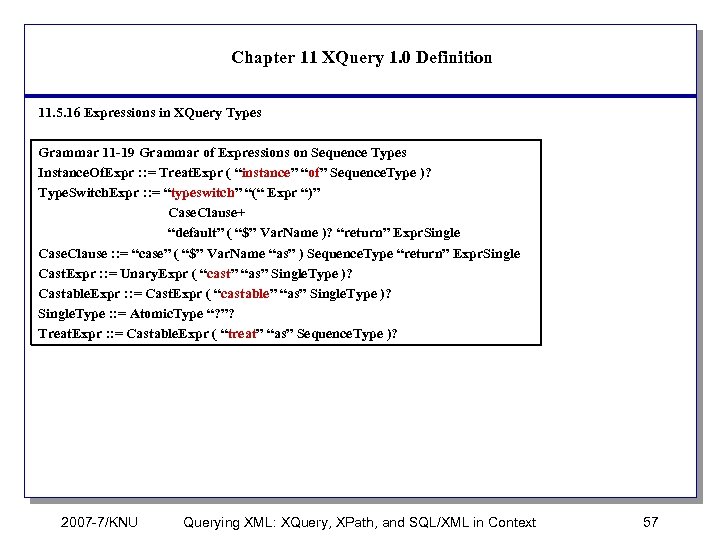

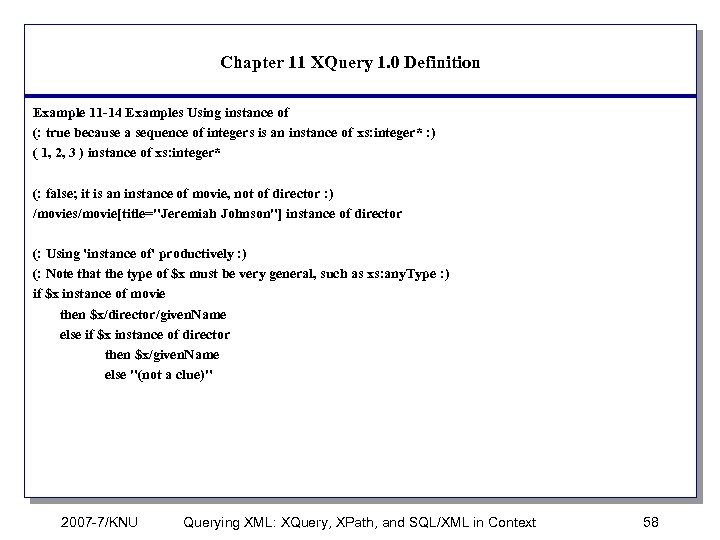

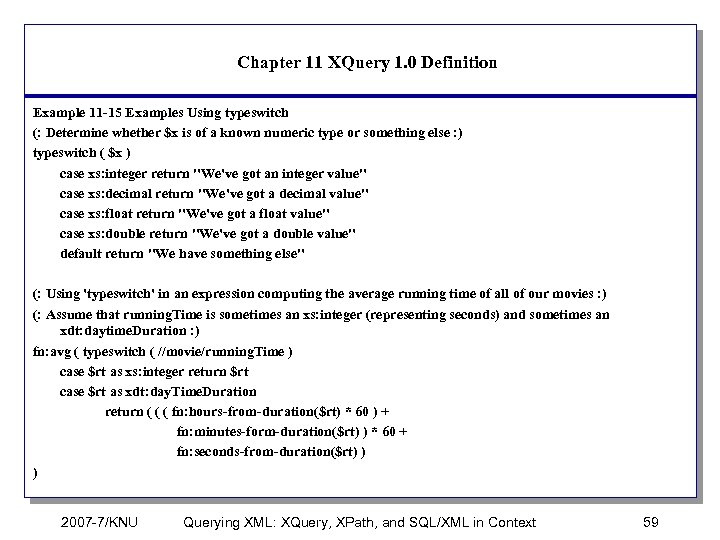

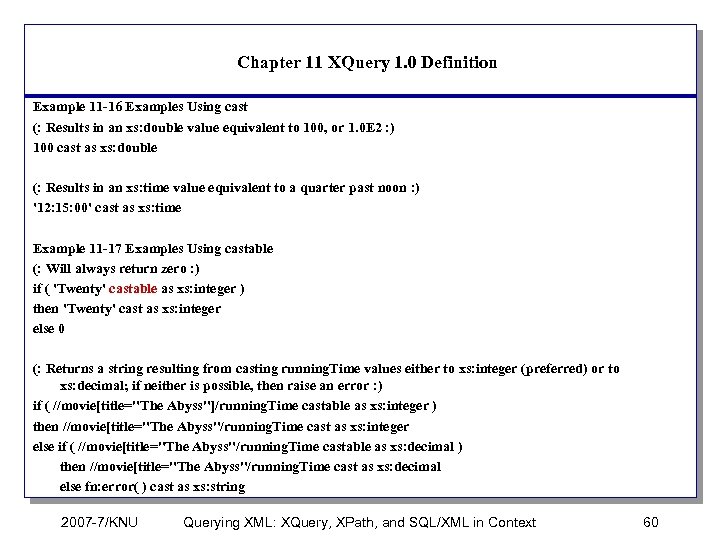

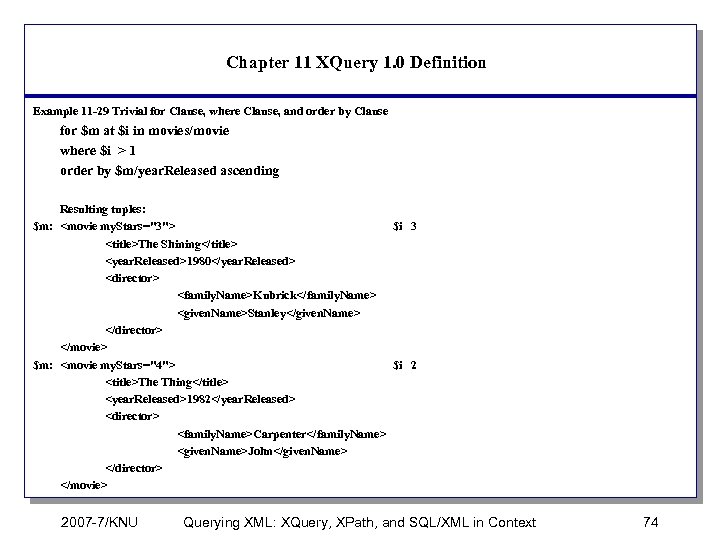

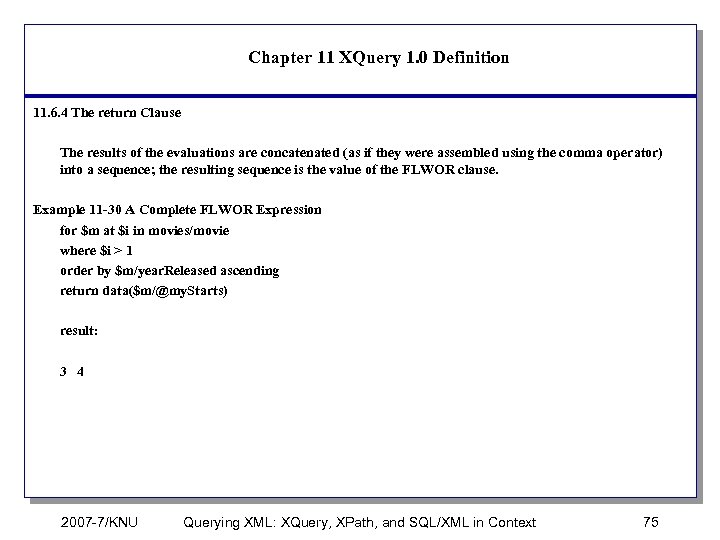

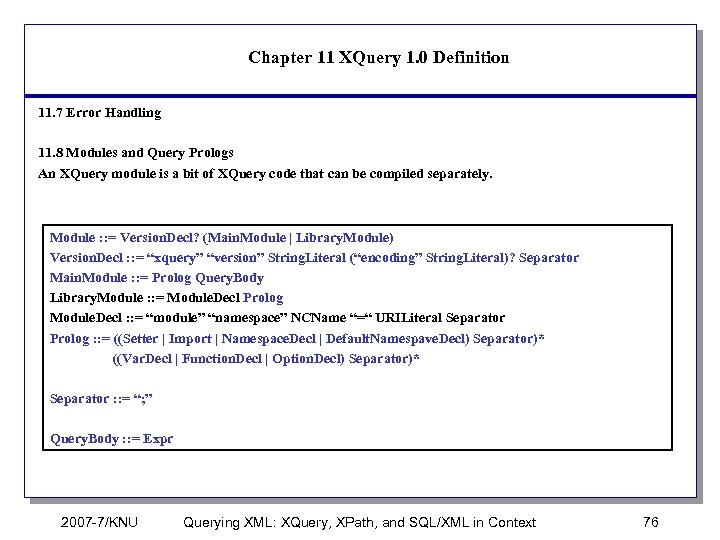

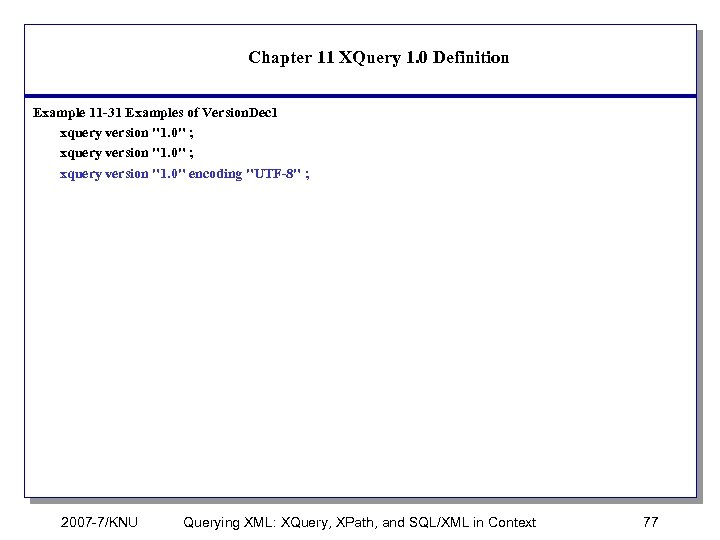

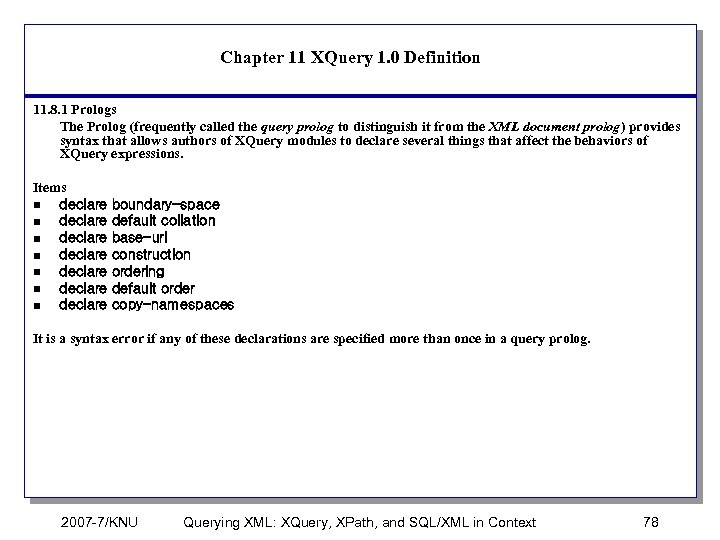

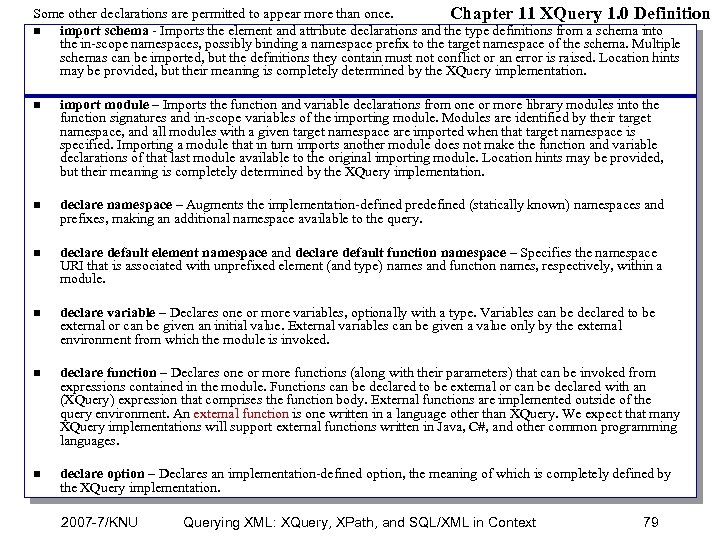

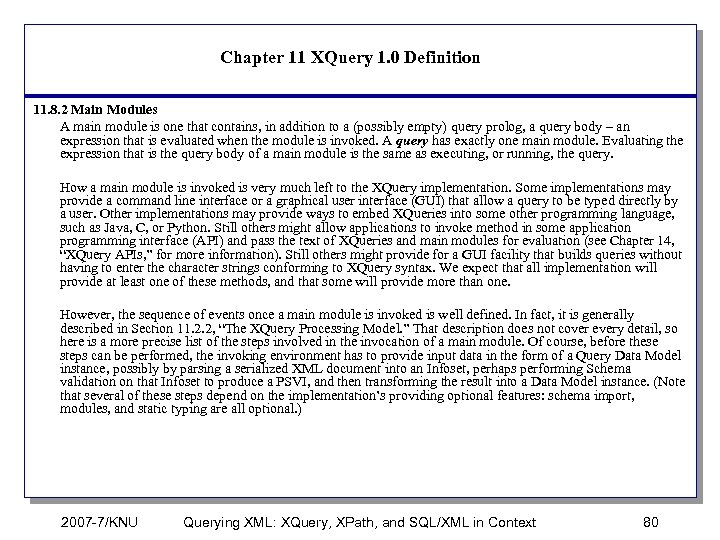

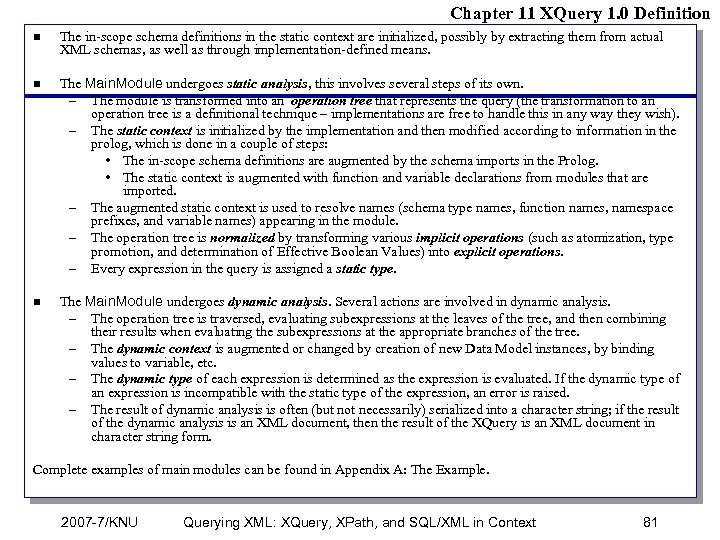

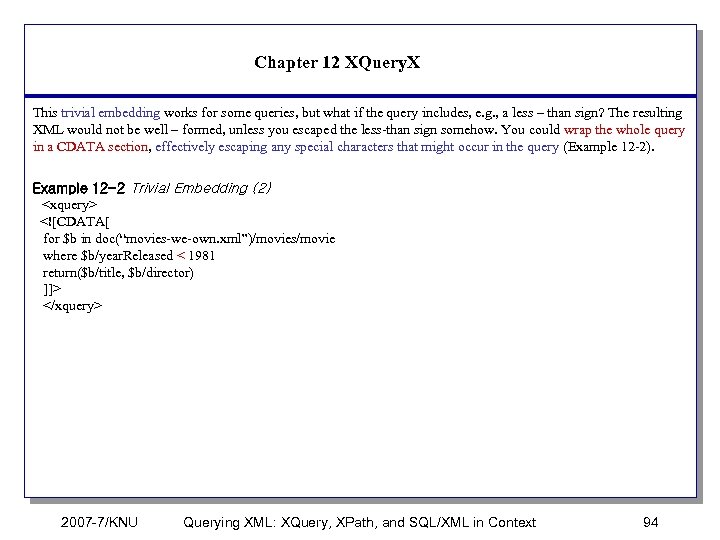

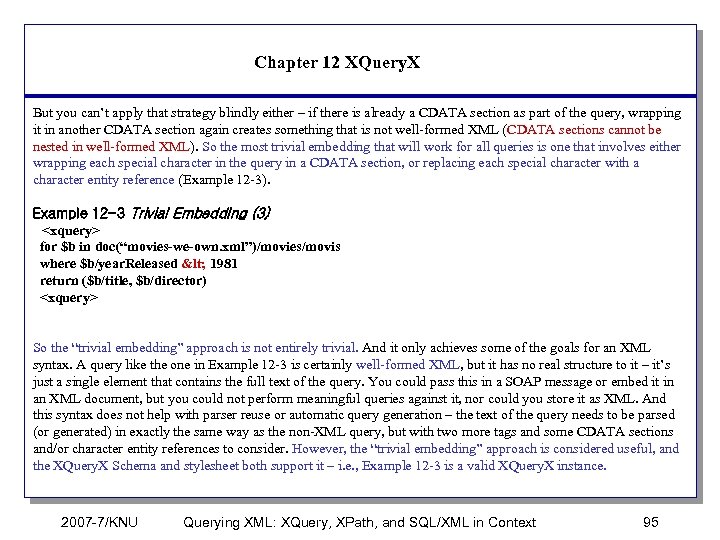

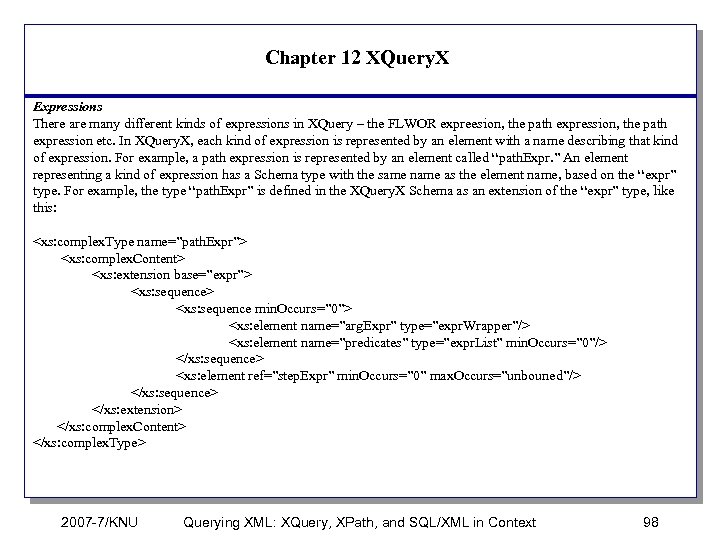

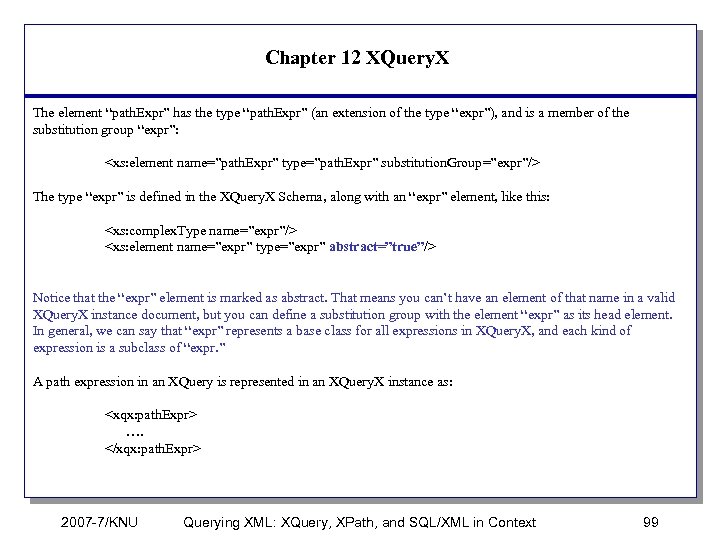

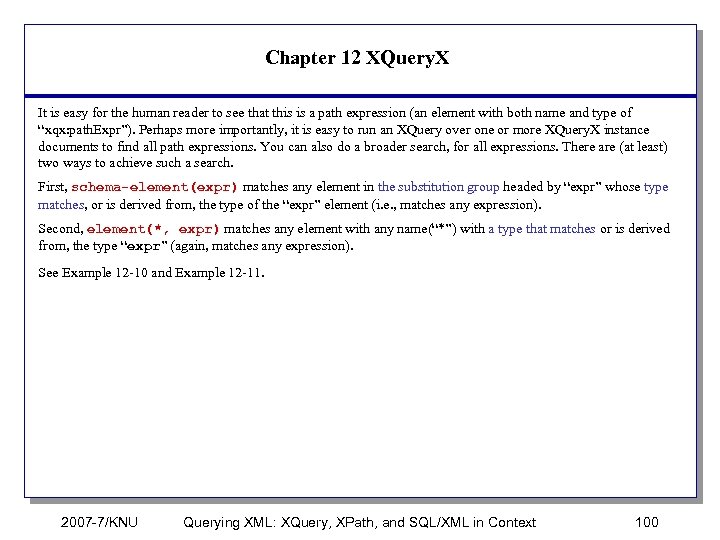

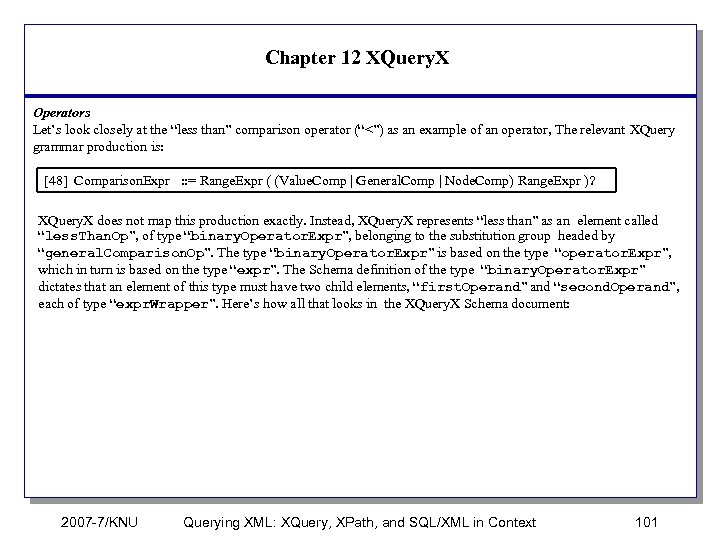

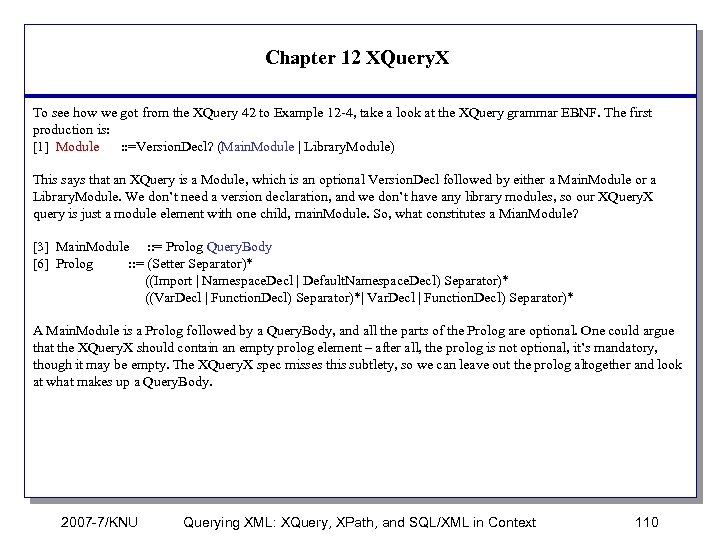

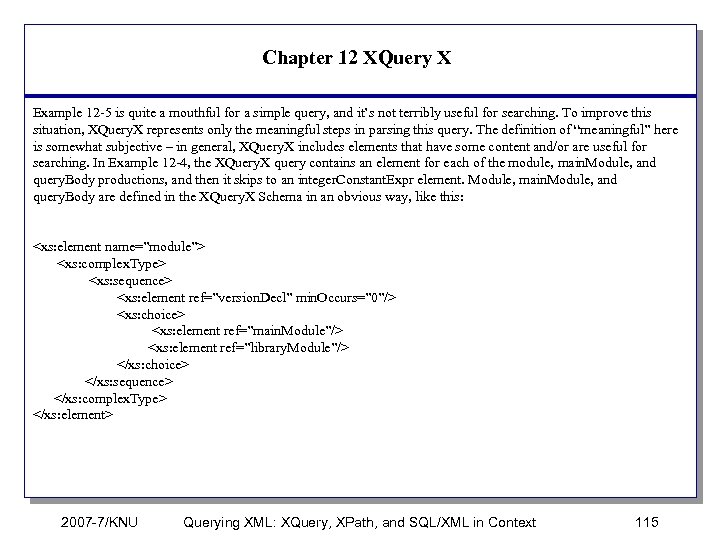

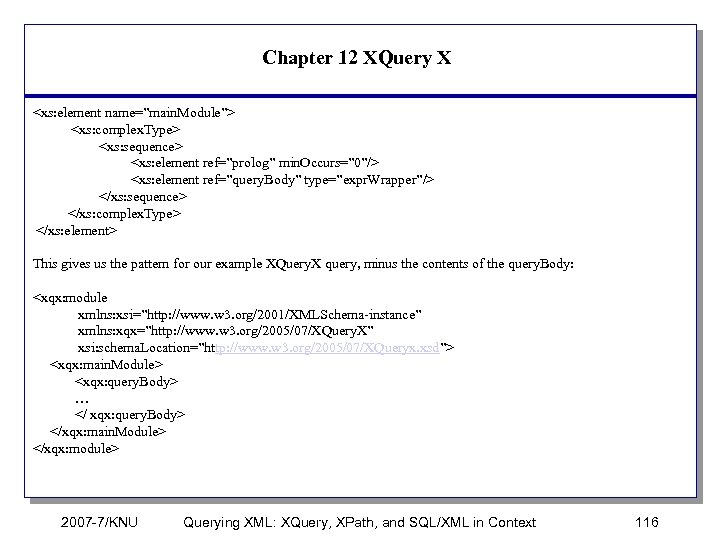

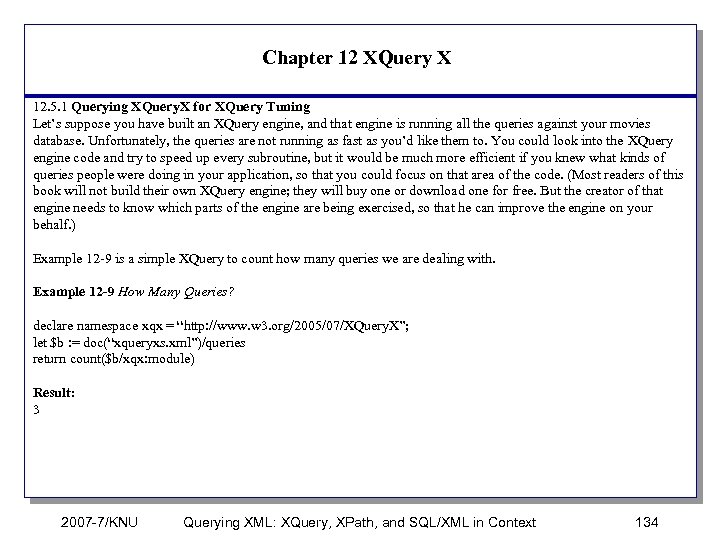

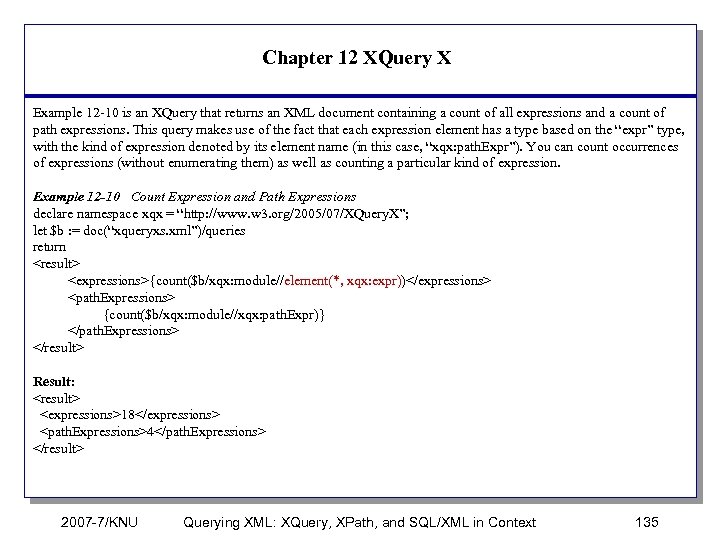

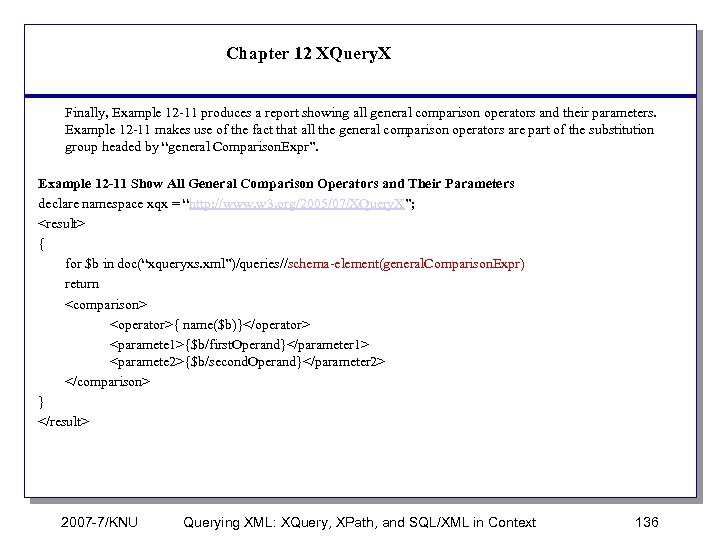

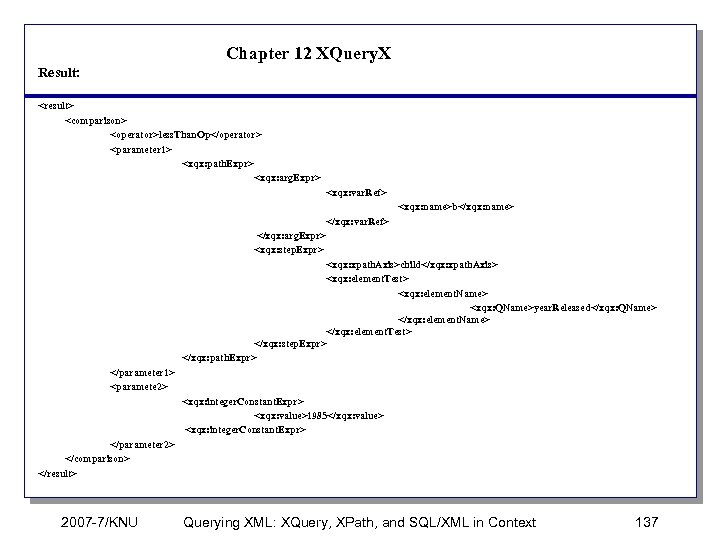

Chapter 11 XQuery 1. 0 Definition Dir. Attribute. Value : : =(‘”’ (Escape. Quote | Quot. Attr. Value. Content)* ‘”’) | (“’” (Escape. Apos | Apos. Attr. Value. Content)* “’”) Quot. Attr. Value. Content : : = Quot. Attr. Content. Char | Common. Content Apos. Attr. Value. Content : : = Apos. Attr. Content. Char | Common. Content Quot. Attr. Content. Char : : Char – [“{}<&] Apos. Attr. Content. Char : : Char – [“{}<&] Escape. Quote : : = ‘””’ Escape. Apos : : = “’’” Enclosed. Expr : : = “{“ Expr “}” Dir. Comment. Constructor : : = “” Dir. Comment. Contents : : = ((Char – ‘-’) | (‘-’ (Char – ‘-’)))* Dir. PIConstructor : : = “” Dir. PIContents : : = (Char* - (Char* ‘? >’ Char*)) 2007 -7/KNU Querying XML: XQuery, XPath, and SQL/XML in Context 50