2f3b8512f5a47a6436bf2d10add34b7c.ppt

- Количество слайдов: 85

Public Goods

What is a Public Good • A good with shared benefits • The “public-ness” of a good has to do with its’ innate features and the legal framework • Not whether it is publicly or privately financed • Not because supply is determined by public policy

Public Goods • A public good is a good that is nonexcludable and non-rival in consumption • Whereas only one person at a time benefits from a private good, multiple people benefit from a public good at the same time.

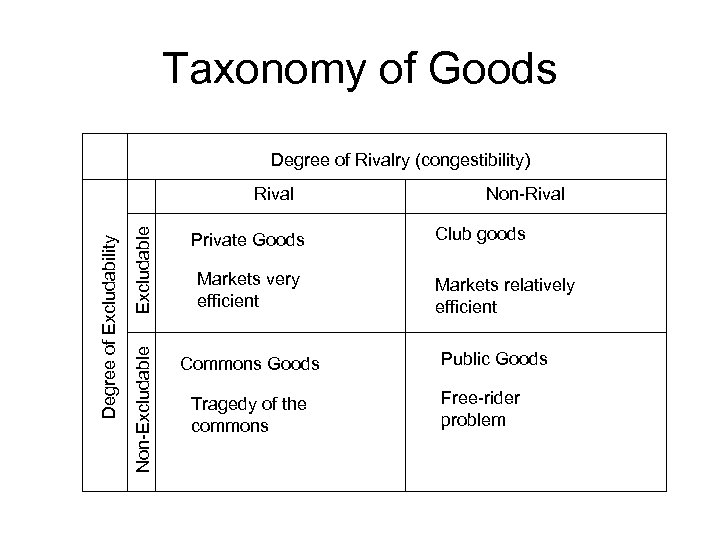

Taxonomy of Goods Degree of Rivalry (congestibility) Excludable Private Goods Non-Excludable Degree of Excludability Rival Commons Goods Markets very efficient Tragedy of the commons Non-Rival Club goods Markets relatively efficient Public Goods Free-rider problem

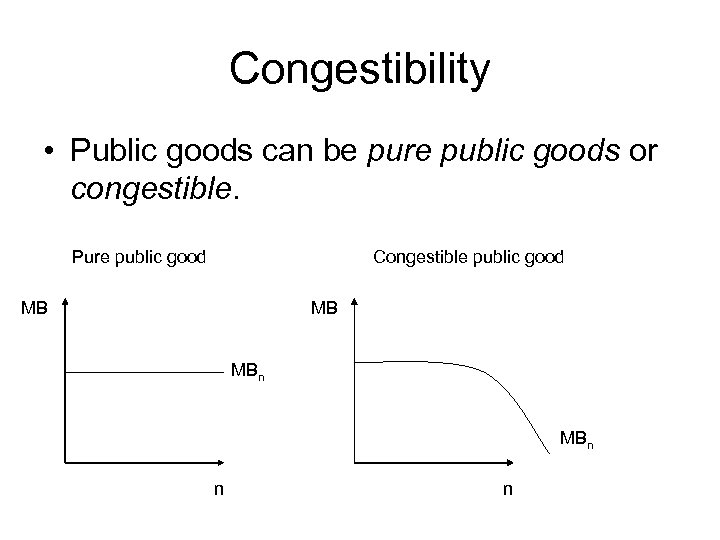

Congestibility • Public goods can be pure public goods or congestible. Pure public good Congestible public good MB MB MBn n n

Market provision of Public Goods • Markets often struggle when it comes to providing public goods • Free-riding means somebody is attempting to benefit from a public good without paying for it. • Markets can and do provide some public goods • non-rivalry is not cause of difficulty in providing public goods, but rather non-excludability is • If everyone attempts to free ride, the public good is not provided

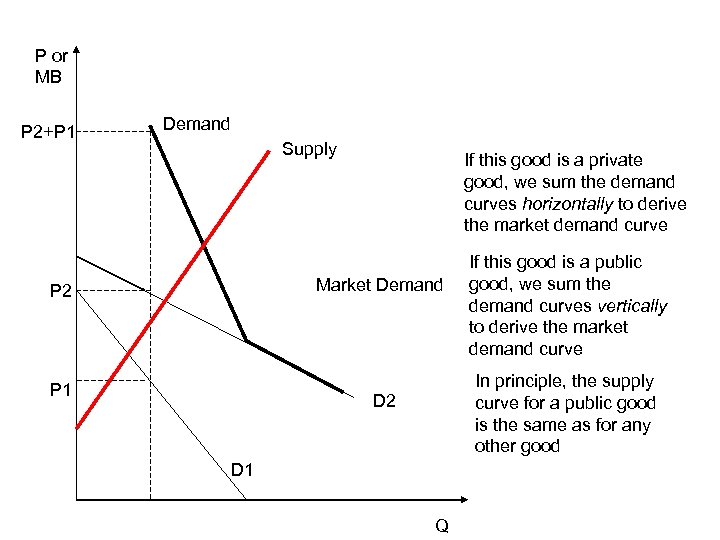

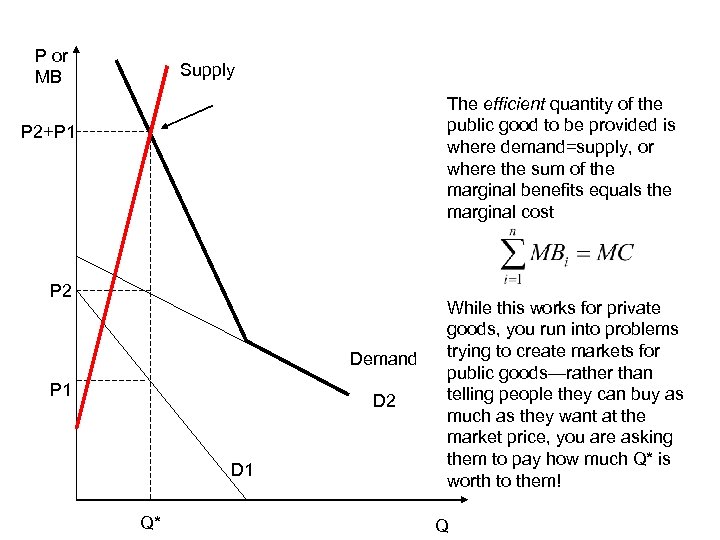

Public and Private Goods • For private goods, to aggregate demand curves (willingness to pay) we sum the individual demand curves horizontally • For public goods, we sum the individual demand curves vertically • The difference comes from rivalry—while only one person can consume a private good, any number of people can consume a public good

P or MB P 2+P 1 Demand Supply If this good is a private good, we sum the demand curves horizontally to derive the market demand curve Market Demand P 2 P 1 If this good is a public good, we sum the demand curves vertically to derive the market demand curve In principle, the supply curve for a public good is the same as for any other good D 2 D 1 Q

P or MB Supply The efficient quantity of the public good to be provided is where demand=supply, or where the sum of the marginal benefits equals the marginal cost P 2+P 1 P 2 Demand P 1 D 2 D 1 Q* While this works for private goods, you run into problems trying to create markets for public goods—rather than telling people they can buy as much as they want at the market price, you are asking them to pay how much Q* is worth to them! Q

Deception! • If the police were funded entirely by asking citizens to pay them what the citizens thought the police were worth to them, what would happen? • People would misrepresent their personal benefits

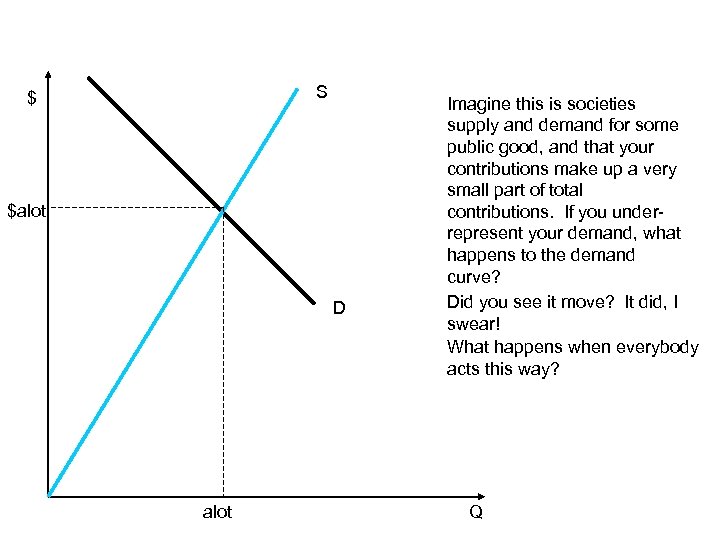

S $ $alot D alot Imagine this is societies supply and demand for some public good, and that your contributions make up a very small part of total contributions. If you underrepresent your demand, what happens to the demand curve? Did you see it move? It did, I swear! What happens when everybody acts this way? Q

Free-Riding • Nearly all individuals have incentive to free ride on the provision of a public good • The amount of the public good actually provided will probably be somewhere near the amount demanded by the person with the highest willingness to pay • Especially in large groups, free riding will lead to massive under provision of the public good

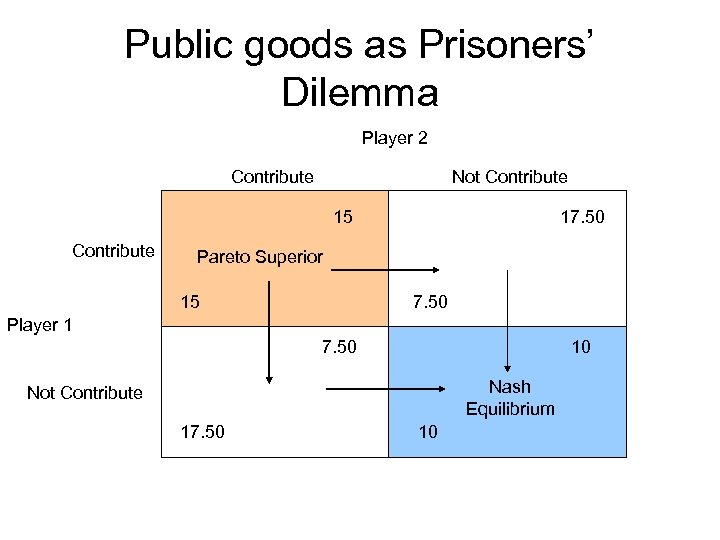

Public goods as Prisoners’ Dilemma • 2 Players • Strategies are to contribute or not to contribute to the public good • Public good works like this. Players can choose to invest 10 dollars in public good. If they do so, each player gets a benefit of $7. 50 each

Public goods as Prisoners’ Dilemma Player 2 Contribute Not Contribute 15 Contribute 17. 50 Pareto Superior 15 7. 50 Player 1 7. 50 10 Nash Equilibrium Not Contribute 17. 50 10

Public goods as Prisoners’ Dilemma • Role of government is to move from “state of nature” (that is, the Nash equilibrium) to the Pareto preferred outcome • Compulsory taxation and public financing of the project

Supply and types of public goods • So far, we have assumed (at least implicitly) that the supply of a public good is additive in nature • Quantity supplied=Σ of contributions • If this is the case, free-riding is rational but inefficient

Other types of public goods • Weakest Link public goods—a good such that the level of the public good that prevails is the amount purchased by the individual who purchased the least. • Volunteer public goods—a good such that, once a single person has provided it, it is provided for everybody (a. k. a. best shot public goods). • Volunteer is the opposite of a weakest link public good.

Volunteer public goods • Volunteer public goods will tend to be provided, despite the fact that free riding in this case is rational • Examples: • Security • Stopping to help a broken down motorist • Free riding is rational and efficient

Volunteer public goods • The amount of the public good received by any one person is identical to the quantity received by anyone else • If zi is the contribution made by the ith member of society, and Gi is the amount of the public good consumed by that member • G=max{z 1, z 2, …zn}=G 1=G 2=…=Gn

Why is free riding efficient? • Consider 4 individuals who incur costs to provide this public good: • z 1=$12 • z 2=$18 • z 3=$7 • z 4=$13 • Because G=max{z 1, z 2, …zn}=G 1=G 2=…=Gn, and max{z 1, z 2, …zn}=$18, everybody gets $18 worth of the public good and the other $32 spent is wasted!

Who will volunteer? • If individuals are heterogeneous, you will likely see the least-cost individual or greatest-benefit individual volunteer. • Example: Say a woman is being mugged on a busy street—who will help her? • Likely the person with the most to gain, or person with lowest cost • Otherwise, you might wind up in a game of “chicken”

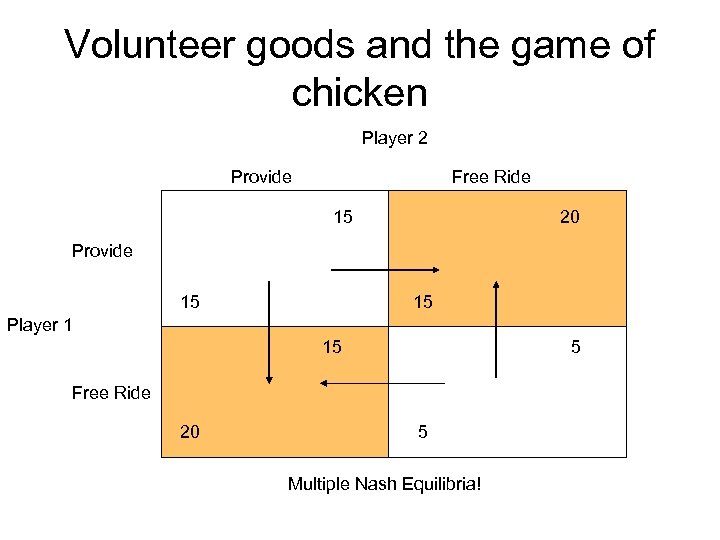

Volunteer goods and the game of chicken • 2 Players • Each can decide to provide the volunteer good or not • The volunteer good is worth $20 to each individual, and it costs $5 to provide it. • If the volunteer good is not provided, each gets a payoff of $5

Volunteer goods and the game of chicken Player 2 Provide Free Ride 15 20 Provide 15 15 Player 1 15 5 Free Ride 20 5 Multiple Nash Equilibria!

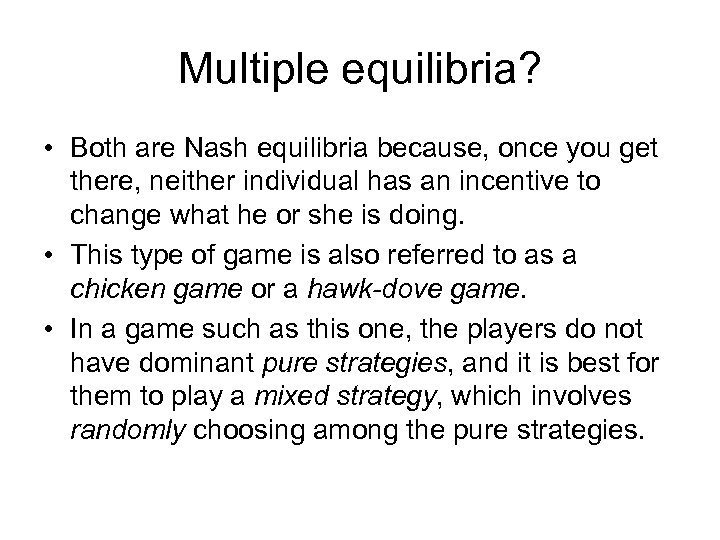

Multiple equilibria? • Both are Nash equilibria because, once you get there, neither individual has an incentive to change what he or she is doing. • This type of game is also referred to as a chicken game or a hawk-dove game. • In a game such as this one, the players do not have dominant pure strategies, and it is best for them to play a mixed strategy, which involves randomly choosing among the pure strategies.

Mixed Strategies • In a mixed strategy equilibrium, each player randomizes between each possible strategy in such a way to make the other player indifferent between all of his choices • What is the intuition? • If you contribute every time, the other guy will never contribute, and you’d like to free ride • If you never contribute, you run the risk of not having the good produced, which you do want.

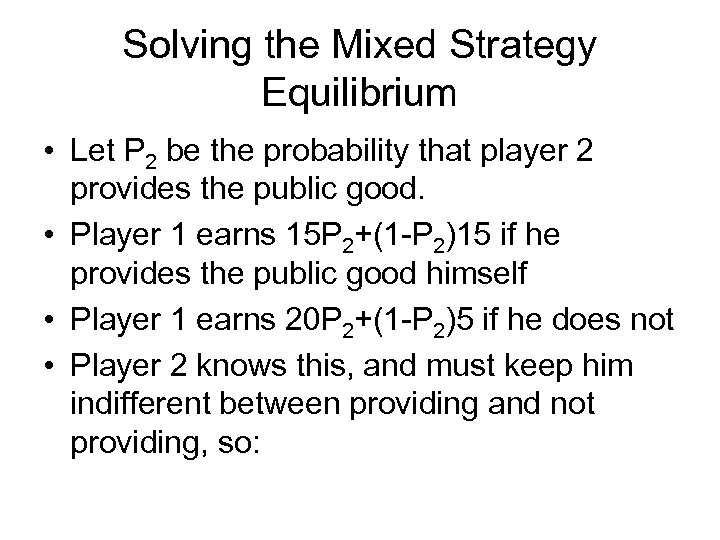

Solving the Mixed Strategy Equilibrium • Let P 2 be the probability that player 2 provides the public good. • Player 1 earns 15 P 2+(1 -P 2)15 if he provides the public good himself • Player 1 earns 20 P 2+(1 -P 2)5 if he does not • Player 2 knows this, and must keep him indifferent between providing and not providing, so:

Solving the Mixed Strategy Equilibrium • 15 P 2+(1 -P 2)15= 20 P 2+(1 -P 2)5 and we solve for P 2=2/3 • By the same logic, P 1=2/3 as well • What is likelihood that the public good gets provided? • 8/9 (4/9 that they both provide it, 2/9 that 1 does and 2 doesn’t, and 2/9 that 2 does and 1 doesn’t)

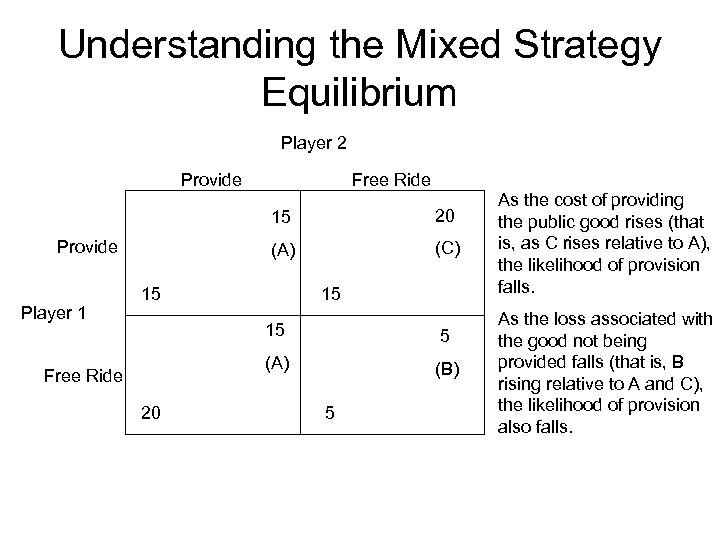

Understanding the Mixed Strategy Equilibrium Player 2 Provide Free Ride 15 (A) Provide Player 1 20 (C) 15 15 15 (A) Free Ride 20 5 (B) 5 As the cost of providing the public good rises (that is, as C rises relative to A), the likelihood of provision falls. As the loss associated with the good not being provided falls (that is, B rising relative to A and C), the likelihood of provision also falls.

Which equilibrium? • Which of the three equilibria will prevail in a simultaneous move game? • Signalling/Pre-commitment • Focal points • Social Norms • Sequential Decisions and last mover

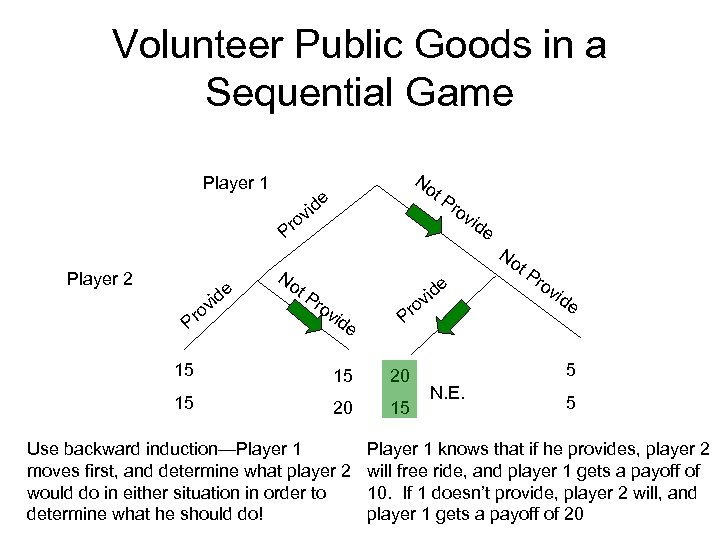

Volunteer Public Goods in a Sequential Game Player 1 Player 2 e vid o Pr 15 15 No e id v ro P No t. P ro vid e No vid e e id v ro P 15 20 20 15 Use backward induction—Player 1 moves first, and determine what player 2 would do in either situation in order to determine what he should do! t. P ro vid e 5 N. E. 5 Player 1 knows that if he provides, player 2 will free ride, and player 1 gets a payoff of 10. If 1 doesn’t provide, player 2 will, and player 1 gets a payoff of 20

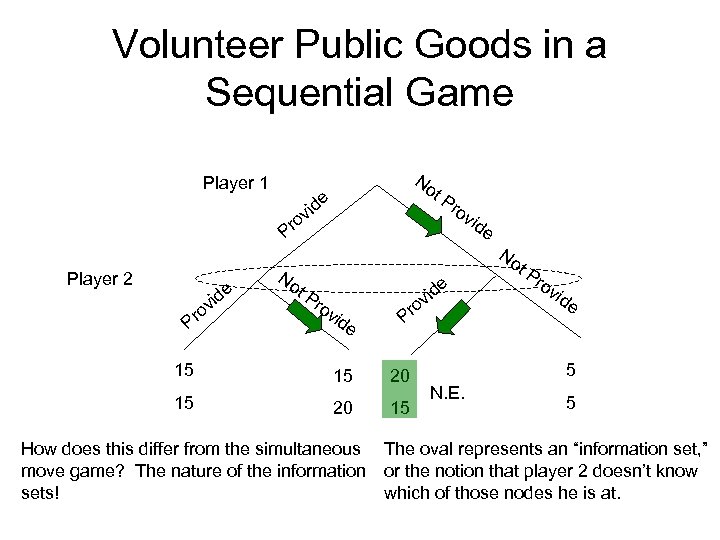

Volunteer Public Goods in a Sequential Game Player 1 Player 2 e vid o Pr 15 15 No e id v ro P No t. P ro vid e No vid e e id v ro P 15 20 20 15 t. P ro vid e 5 N. E. 5 How does this differ from the simultaneous The oval represents an “information set, ” move game? The nature of the information or the notion that player 2 doesn’t know sets! which of those nodes he is at.

Weakest-Link public goods • The amount of the public good received by any one person is identical to the quantity received by anyone else • If zi is the contribution made by the ith member of society, and Gi is the amount of the public good consumed by that member • G=min{z 1, z 2, …zn}=G 1=G 2=…=Gn

Weakest Link public goods • Volunteer public goods will tend to be provided, because free riding in this case is irrational • Examples: • Levees • Technological standards • Health/disease control • Airport security • Free riding is inefficient and irrational

Why is free riding irrational? • Consider 4 individuals who incur costs to provide this public good: • z 1=$12 • z 2=$18 • z 3=$7 • z 4=$13 • Because G=min{z 1, z 2, …zn}=G 1=G 2=…=Gn, and max{z 1, z 2, …zn}=$7, everybody gets $7 worth of the public good. If the consumer who put in $7 actually valued it at (say) $12, free riding has harmed him!

What is the likely outcome? • If individuals are heterogeneous, you will likely see an amount provided equal to the amount wanted by the lowest value demander. • Unless the decisions are made sequentially, you wind up in a coordination game.

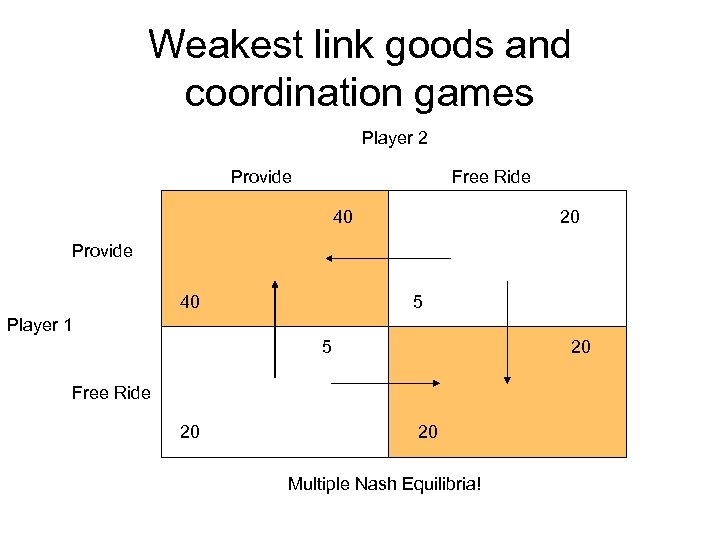

Weakest link goods and coordination games • 2 Players • Each can decide to provide the public good or not • The weakest link good is worth $55 to each individual, and it costs $15 to provide it. • If the volunteer good is not provided, each gets a payoff of $20

Weakest link goods and coordination games Player 2 Provide Free Ride 40 20 Provide 40 5 Player 1 5 20 Free Ride 20 20 Multiple Nash Equilibria!

Coordination games v. Hawk. Dove/Chicken games • In a coordination game, both players want to play the same strategy • In a hawk-dove or chicken game, both players want to play different strategies. • Both types are going to have multiple equilibria, both in pure and mixed strategies.

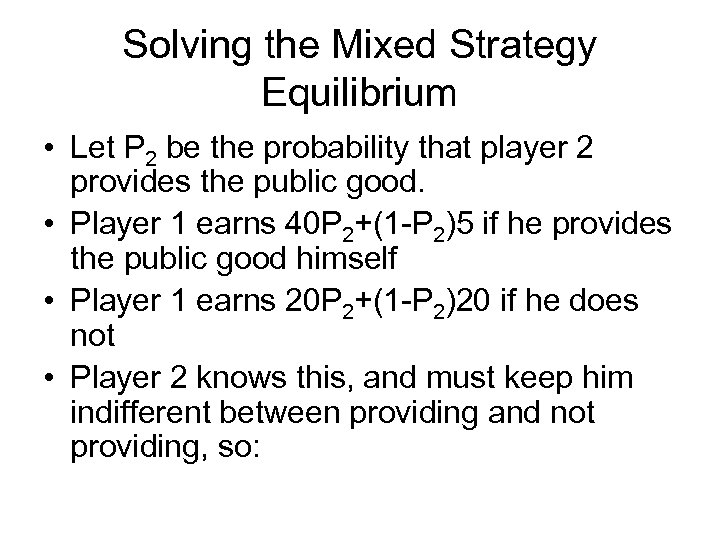

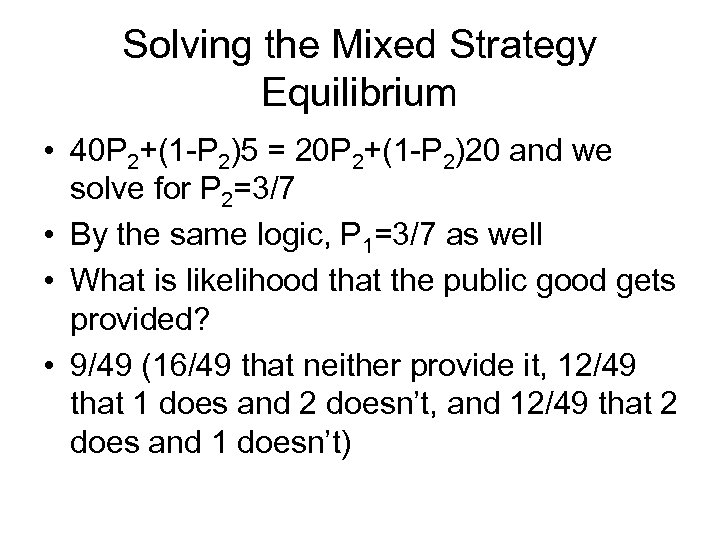

Solving the Mixed Strategy Equilibrium • Let P 2 be the probability that player 2 provides the public good. • Player 1 earns 40 P 2+(1 -P 2)5 if he provides the public good himself • Player 1 earns 20 P 2+(1 -P 2)20 if he does not • Player 2 knows this, and must keep him indifferent between providing and not providing, so:

Solving the Mixed Strategy Equilibrium • 40 P 2+(1 -P 2)5 = 20 P 2+(1 -P 2)20 and we solve for P 2=3/7 • By the same logic, P 1=3/7 as well • What is likelihood that the public good gets provided? • 9/49 (16/49 that neither provide it, 12/49 that 1 does and 2 doesn’t, and 12/49 that 2 does and 1 doesn’t)

Which equilibrium? • Which of the three equilibria will prevail in a simultaneous move game? • Again, the answers may be found through such mechanisms as Signalling/Precommitment, Focal points, Social Norms, and Sequential Decisions

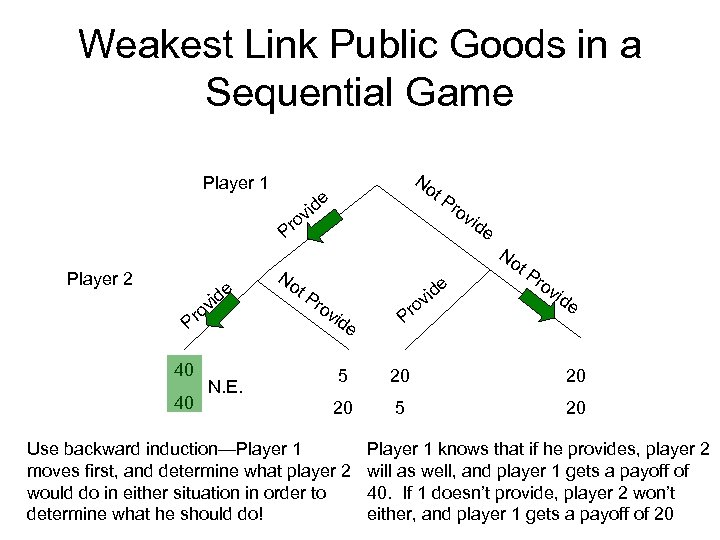

Weakest Link Public Goods in a Sequential Game Player 1 Player 2 e vid o Pr 40 40 N. E. No e id v ro P No t. P ro vid e No vid e e id v ro P t. P ro vid e 5 20 20 20 5 20 Use backward induction—Player 1 moves first, and determine what player 2 would do in either situation in order to determine what he should do! Player 1 knows that if he provides, player 2 will as well, and player 1 gets a payoff of 40. If 1 doesn’t provide, player 2 won’t either, and player 1 gets a payoff of 20

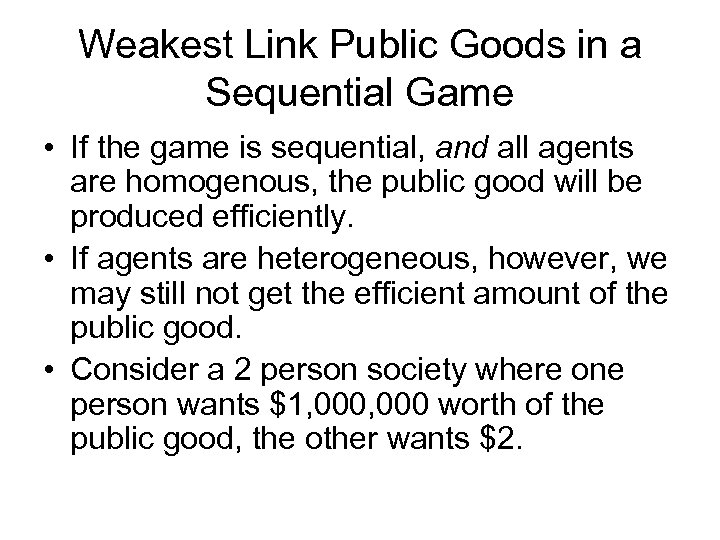

Weakest Link Public Goods in a Sequential Game • If the game is sequential, and all agents are homogenous, the public good will be produced efficiently. • If agents are heterogeneous, however, we may still not get the efficient amount of the public good. • Consider a 2 person society where one person wants $1, 000 worth of the public good, the other wants $2.

National Defence as a public good • War (or the threat of warfare) may be enough to justify a government. • Consider a game between 2 countries • Each can spend $1 T on military or not • Without spending, GDP in each country is $5 T • If one spends and the other doesn’t, the spender can invade and take money—we’ll assume that they destroy $1 T worth of stuff and take $3 T home with them

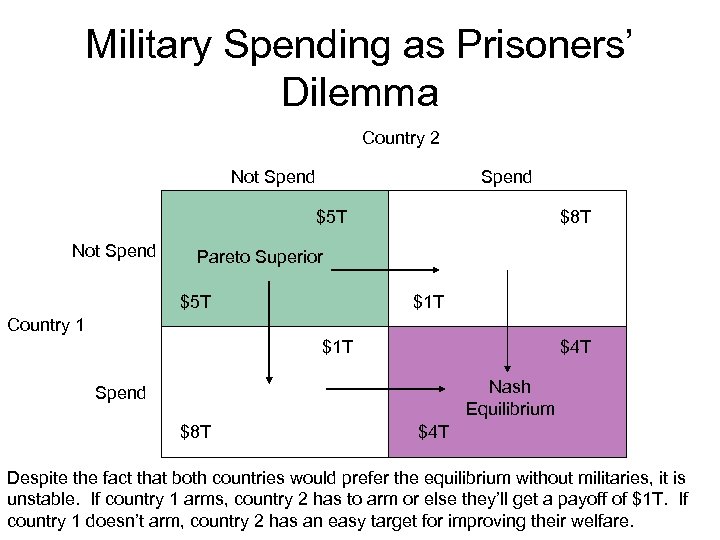

Military Spending as Prisoners’ Dilemma Country 2 Not Spend $5 T Not Spend $8 T Pareto Superior $5 T $1 T Country 1 $1 T $4 T Nash Equilibrium Spend $8 T $4 T Despite the fact that both countries would prefer the equilibrium without militaries, it is unstable. If country 1 arms, country 2 has to arm or else they’ll get a payoff of $1 T. If country 1 doesn’t arm, country 2 has an easy target for improving their welfare.

National Defence as a public good • But doesn’t the same logic apply to individuals within a country, deciding to volunteer for service or not (or to contribute money to defence)? • Everybody in the country would prefer to free ride on the contributions of everyone else. • Without some coercive taxation and public financing of military, the country will wind up overrun by their neighbours!

Public Finance and Public Supply • For most prisoners’ dilemma type goods, and many weakest-link type goods, there is some potential for a government to improve on the anarchic outcome by overcoming the free rider problem • 2 methods—public finance and public supply

Public Finance and Public Supply • Public Finance—government raises revenues, and then contracts out to private firms. • Public Supply—government raises revenues, and uses these revenues to produce the public good themselves. • Overcoming free riding problem makes a case for public finance, but it does not necessarily make a case for public supply!

Information and Public Goods

Information and Public Goods • From here, we’ll mostly stick to discussing public goods that are prisoners’ dilemmas in nature. • For these goods, the quantity of the public good supplied is the sum of individual contributions. • n=the number of people contributing • zi=the contribution of individual i

Information and Public Goods • The quantity of the public good G available to the entire population of n people is: • The individual contributions are to be provided through coercive taxation.

Information and Public Goods • Two simplifying assumptions have been made so far, at least implicitly: 1. All individuals value the public good by the same amount 2. The government has full information on how much each individual values the public good

Heterogenous Individuals • If individuals have different valuations, efficiency dictates that each person pays his/her marginal valuation of the good in taxes: • Ti=MBi for all I • Thus, the tax T simply replaces the price that people won’t truthfully pay

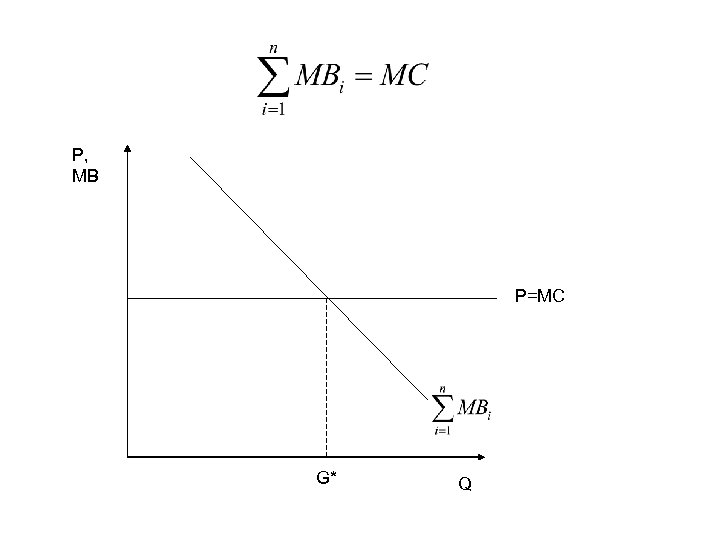

Imperfect information • What if, however, the government doesn’t have full information? • Individuals have no incentive to accurately reveal their marginal valuations • Government can not determine efficient amount of the public good! • Recall efficiency condition:

P, MB P=MC G* Q

Imperfect information • If the government doesn’t have full information the government confronts the identical information problem that was the whole reason for wanting a government to finance the public good!

Optimal pricing and the Lindahl solution • Assume 2 individuals, person 1 and person 2 • They each share the cost of the public good, and pay a proportion of the cost of the public good, s 1 and s 2, where s 1=1 -s 2 (alternately, Σsi=1) • Thus, if the per-unit price is P, person 1 pays P 1=s 1 P

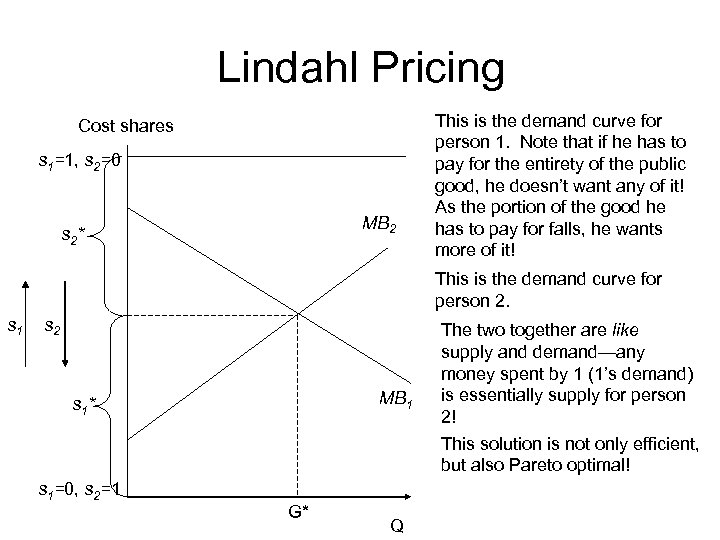

Lindahl Pricing Cost shares s 1=1, s 2=0 MB 2 s 2* This is the demand curve for person 1. Note that if he has to pay for the entirety of the public good, he doesn’t want any of it! As the portion of the good he has to pay for falls, he wants more of it! This is the demand curve for person 2. s 1 s 2 MB 1 s 1* s 1=0, s 2=1 G* Q The two together are like supply and demand—any money spent by 1 (1’s demand) is essentially supply for person 2! This solution is not only efficient, but also Pareto optimal!

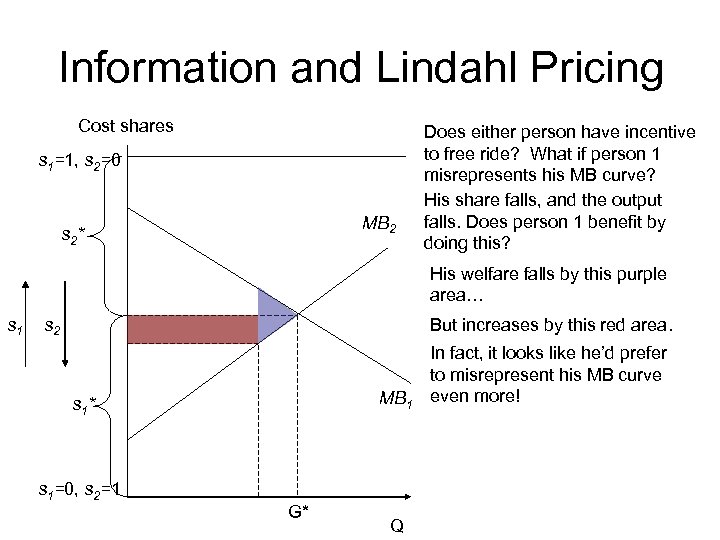

Information and Lindahl Pricing Cost shares s 1=1, s 2=0 MB 2 s 2* Does either person have incentive to free ride? What if person 1 misrepresents his MB curve? His share falls, and the output falls. Does person 1 benefit by doing this? His welfare falls by this purple area… s 1 s 2 But increases by this red area. MB 1 s 1* s 1=0, s 2=1 G* Q In fact, it looks like he’d prefer to misrepresent his MB curve even more!

Information problems • It should be obvious by now that, if individuals would free ride on the provision of a public good without government intervention, they’ll do it if the government gets involved as well. • So, how to get them to reveal honestly?

Information Revelation • How can we get individuals to reveal their true MB information? • What if we assure people that we will finance the project through general taxation? • Result: overstating benefits and overprovision! • One solution: Clarke tax—individuals have incentive to truthfully reveal

Cost-Benefit Analysis • Many reasons for using CBA • Individuals have no incentive to accurately reveal preferences • Suppliers (both private and public) may have incentives to misrepresent their costs

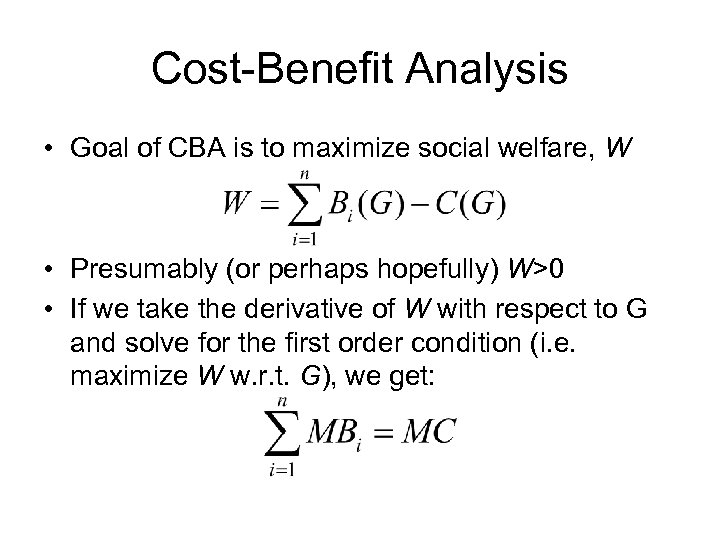

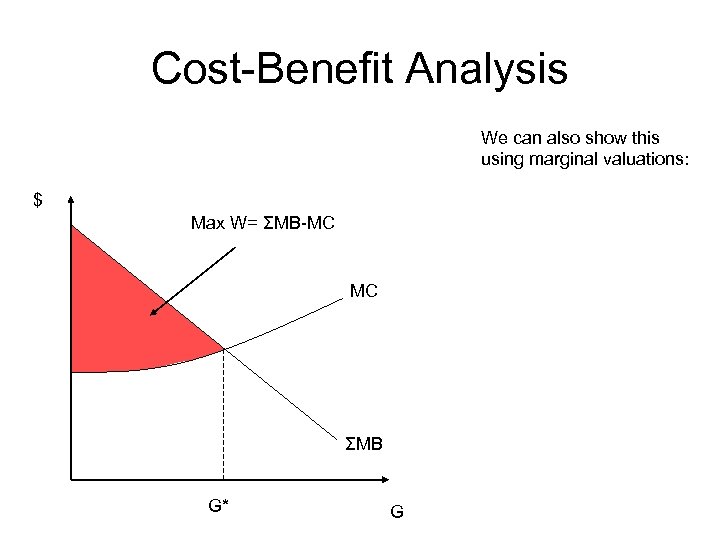

Cost-Benefit Analysis • Goal of CBA is to maximize social welfare, W • Presumably (or perhaps hopefully) W>0 • If we take the derivative of W with respect to G and solve for the first order condition (i. e. maximize W w. r. t. G), we get:

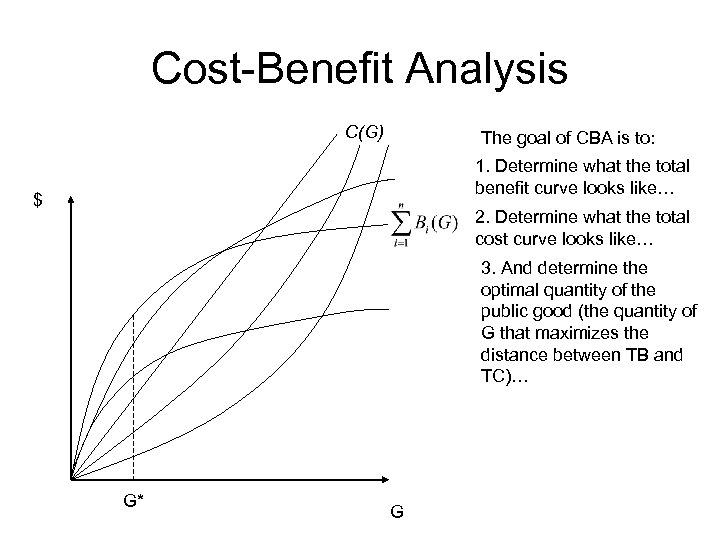

Cost-Benefit Analysis C(G) The goal of CBA is to: 1. Determine what the total benefit curve looks like… $ 2. Determine what the total cost curve looks like… 3. And determine the optimal quantity of the public good (the quantity of G that maximizes the distance between TB and TC)… G* G

Cost-Benefit Analysis We can also show this using marginal valuations: $ Max W= ΣMB-MC MC ΣMB G* G

Estimating the value of life • How much do you value your life? • The value of human life is not infinite • While we don’t ask this question directly, we do use market prices to try to estimate the value of a human life…

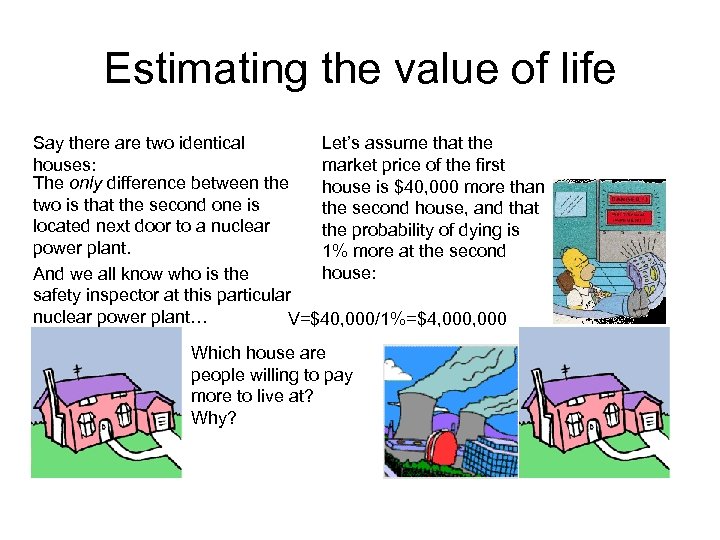

Estimating the value of life Say there are two identical Let’s assume that the houses: market price of the first The only difference between the house is $40, 000 more than two is that the second one is the second house, and that located next door to a nuclear the probability of dying is power plant. 1% more at the second house: And we all know who is the safety inspector at this particular nuclear power plant… V=$40, 000/1%=$4, 000 Which house are people willing to pay more to live at? Why?

CBA and Time • Benefits and Costs of public goods generally extend over a period of time • Most goods have costs now and benefits later (generally any time any building is undertaken) • Some goods have benefits not and costs later (environmental damage, for example) • To value a good over time, we need to choose a discount rate

Discount rates • A discount rate, r, tells us how much we value the present relative to the future • If r=0, then we care about the future just as much as today • If r=∞, then we care only about today • The choice of discount rates is very important in determining whether or not a project gets funded.

Two methods of time valuation • Choose a discount rate and calculate the NPV (net present value) • Calculate the IRR (internal rate of return) —the discount rate at which the project breaks even • In both cases, higher is better

Risk and Uncertainty • With time comes risk and uncertainty: • Will a project be relevant in 10 -20 years? • What will the costs of a project be in 20 years? • What is the appropriate amount of risk for a government to take on?

Other considerations • Equity and distributional effects • General caveat: It is more efficient to do pure transfers than to create an inefficient public good for distributional reasons.

Locational Choice • “Voting with your feet” • Different communities/governments create different bundles of public goods financed through taxation. • Individuals move to the community with the best mix of taxes and goods for them. • Logic of federalism yields efficient supply of many public goods by creating a “market” for public goods.

Public Financing for Public Goods

Public Goods—how much • Unfortunately, we may never know how much is efficient! • Governments lack the required information to make efficient choices and implementing Lindahl solutions • CBA, Clarke taxes, and federalism provide potential means of figuring out information • We’ll proceed, assuming that the government has figured out the efficient quantity.

Public Goods—How to pay for them? • Lots of methods, but all boil down to taxes. • Issuing government debt is little more than deferred taxation (Ricardian Equivalence or fiscal illusion? )— however, can be important to ensure that future beneficiaries of public goods pay for them. • Inflation is a tax on people who hold currency (seigniorage tax) • All taxes reduce welfare via two components—transfers (recall rent seeking, however) and DWL • The government receives the transfer • The DWL is never to be seen again!

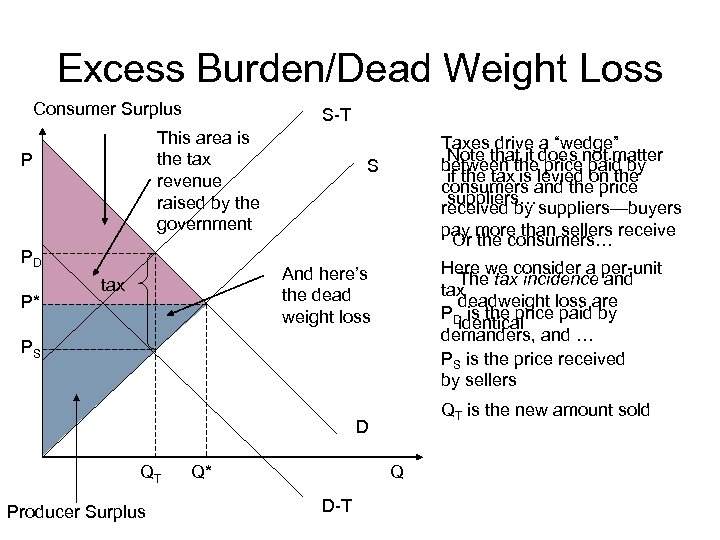

Excess Burden/Dead Weight Loss Consumer Surplus S-T This area is the tax revenue raised by the government P PD P* Taxes drive a “wedge” Note that it does not matter between the price paid by if the tax is levied on the consumers and the price suppliers… received by suppliers—buyers pay more than sellers receive Or the consumers… S Here we consider a per-unit The tax incidence and tax deadweight loss are PD is the price paid by identical demanders, and … PS is the price received by sellers And here’s the dead weight loss tax PS QT is the new amount sold D QT Producer Surplus Q* Q D-T

Excess Burden/Dead Weight Loss • While it is possible for individuals to receive some benefit from the transfer, it is impossible to receive any benefit from the DWL • DWL is greater the more elastic the supply and/or demand curve are • As the tax rate increases, the dead weight loss increases by disproportionately more

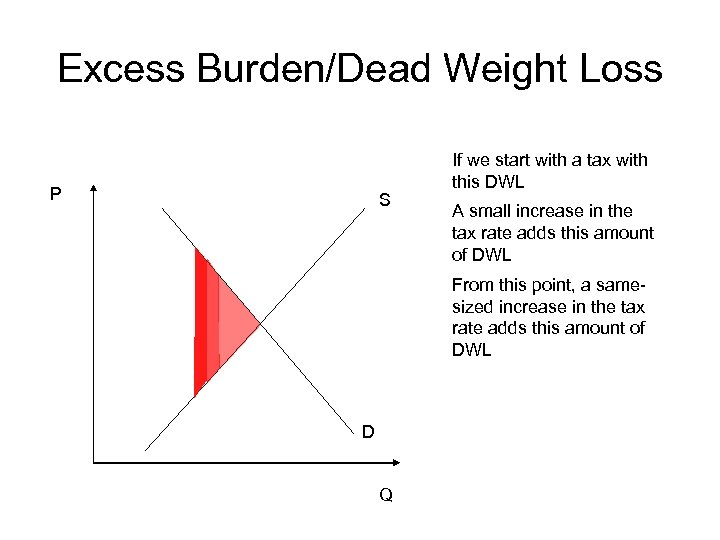

Excess Burden/Dead Weight Loss P S If we start with a tax with this DWL A small increase in the tax rate adds this amount of DWL From this point, a samesized increase in the tax rate adds this amount of DWL D Q

Other sources of inefficiency • • • Administrative costs Enforcement costs Costs of compliance Avoidance costs Evasion costs Rent-Seeking Costs

Why is all this important? • For every one dollar the government spends, they take far more than a dollar out of the economy. • How much is called the marginal cost of government funds • What is the MCF? Estimates range from $1. 2 to well over $4! • Often depends on how many types of cost are considered.

Taxes without excess burden • Property taxes • Taxes on inelastic goods • Lump-sum/poll taxes

Who pays the tax? • Tax incidence refers to the question of who bears the burden of a tax • Government can not influence tax incidence! • Tax incidence is determined by the relative elasticities of the supply and demand curves • Whichever is more inelastic will bear more of the burden of the tax

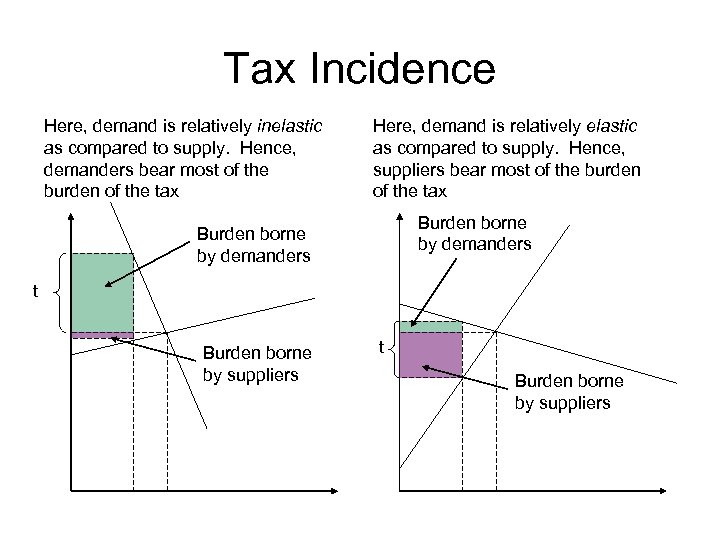

Tax Incidence Here, demand is relatively inelastic as compared to supply. Hence, demanders bear most of the burden of the tax Here, demand is relatively elastic as compared to supply. Hence, suppliers bear most of the burden of the tax Burden borne by demanders t Burden borne by suppliers

Surplus revenue • Sometimes government have more money than they know what to do with! • Cut taxes—this reduces DWL, improves efficiency, and generally increases incomes • Repay debt—this reduces the tax burden of future generations • Why not just spend it on something else—this often leads to the flypaper effect and ratchets.

2f3b8512f5a47a6436bf2d10add34b7c.ppt