c36e48c89554ff0073e864b268311e45.ppt

- Количество слайдов: 10

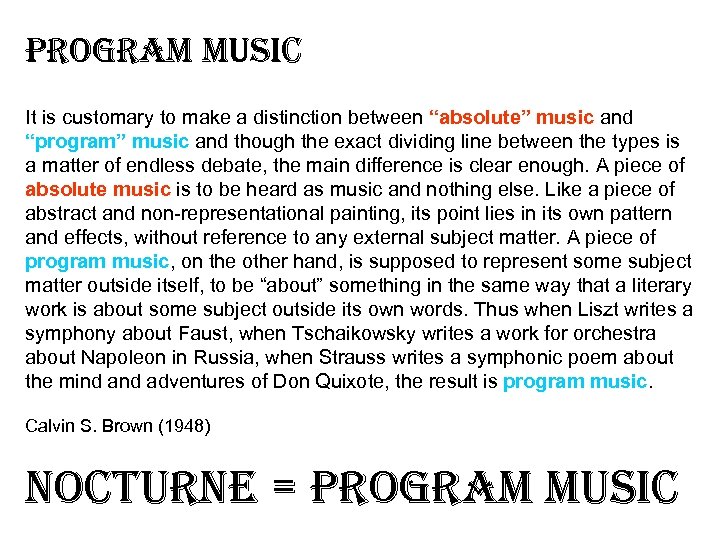

PROGRAM MUs. IC It is customary to make a distinction between “absolute” music and “program” music and though the exact dividing line between the types is a matter of endless debate, the main difference is clear enough. A piece of absolute music is to be heard as music and nothing else. Like a piece of abstract and non-representational painting, its point lies in its own pattern and effects, without reference to any external subject matter. A piece of program music, on the other hand, is supposed to represent some subject matter outside itself, to be “about” something in the same way that a literary work is about some subject outside its own words. Thus when Liszt writes a symphony about Faust, when Tschaikowsky writes a work for orchestra about Napoleon in Russia, when Strauss writes a symphonic poem about the mind adventures of Don Quixote, the result is program music. Calvin S. Brown (1948) NOCTURNE = PROGRAM MUs. IC

PROGRAM MUs. IC It is customary to make a distinction between “absolute” music and “program” music and though the exact dividing line between the types is a matter of endless debate, the main difference is clear enough. A piece of absolute music is to be heard as music and nothing else. Like a piece of abstract and non-representational painting, its point lies in its own pattern and effects, without reference to any external subject matter. A piece of program music, on the other hand, is supposed to represent some subject matter outside itself, to be “about” something in the same way that a literary work is about some subject outside its own words. Thus when Liszt writes a symphony about Faust, when Tschaikowsky writes a work for orchestra about Napoleon in Russia, when Strauss writes a symphonic poem about the mind adventures of Don Quixote, the result is program music. Calvin S. Brown (1948) NOCTURNE = PROGRAM MUs. IC

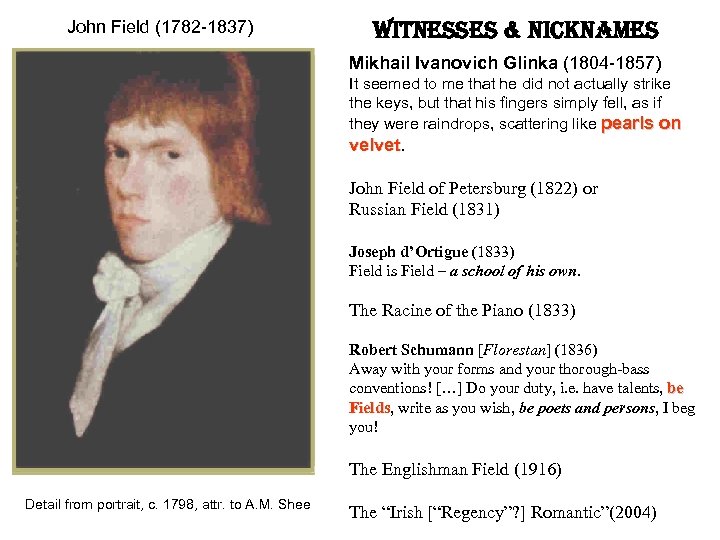

John Field (1782 -1837) Witnesses & nicknames Mikhail Ivanovich Glinka (1804 -1857) It seemed to me that he did not actually strike the keys, but that his fingers simply fell, as if they were raindrops, scattering like pearls on velvet John Field of Petersburg (1822) or Russian Field (1831) Joseph d’Ortigue (1833) Field is Field – a school of his own. The Racine of the Piano (1833) Robert Schumann [Florestan] (1836) Away with your forms and your thorough-bass conventions! […] Do your duty, i. e. have talents, be Fields, write as you wish, be poets and persons, I beg Fields you! The Englishman Field (1916) Detail from portrait, c. 1798, attr. to A. M. Shee The “Irish [“Regency”? ] Romantic”(2004)

John Field (1782 -1837) Witnesses & nicknames Mikhail Ivanovich Glinka (1804 -1857) It seemed to me that he did not actually strike the keys, but that his fingers simply fell, as if they were raindrops, scattering like pearls on velvet John Field of Petersburg (1822) or Russian Field (1831) Joseph d’Ortigue (1833) Field is Field – a school of his own. The Racine of the Piano (1833) Robert Schumann [Florestan] (1836) Away with your forms and your thorough-bass conventions! […] Do your duty, i. e. have talents, be Fields, write as you wish, be poets and persons, I beg Fields you! The Englishman Field (1916) Detail from portrait, c. 1798, attr. to A. M. Shee The “Irish [“Regency”? ] Romantic”(2004)

![field’s “nocturnality”? Ludwig Spohr (1802) […] the technical perfection and the “dreamy melancholy” of field’s “nocturnality”? Ludwig Spohr (1802) […] the technical perfection and the “dreamy melancholy” of](https://present5.com/presentation/c36e48c89554ff0073e864b268311e45/image-4.jpg) field’s “nocturnality”? Ludwig Spohr (1802) […] the technical perfection and the “dreamy melancholy” of that young artist’s melancholy execution Adolph Kullak (1861) [one] who ranks as one the greatest masters of all times in his picturesque diffusion of light and shade, in perfect shade finish united with the warmest feeling. Oscar Bie (1898) One of the chief nocturne-romanticists James Parsons (2004) The bright sun of Enlightenment guides the intellect, while night inspires the unhampered imagination. Schlegel’s imagination contemporaries evidently agreed, as is attested by John Field and Frédéric Chopin’s nocturnes for solo piano […].

field’s “nocturnality”? Ludwig Spohr (1802) […] the technical perfection and the “dreamy melancholy” of that young artist’s melancholy execution Adolph Kullak (1861) [one] who ranks as one the greatest masters of all times in his picturesque diffusion of light and shade, in perfect shade finish united with the warmest feeling. Oscar Bie (1898) One of the chief nocturne-romanticists James Parsons (2004) The bright sun of Enlightenment guides the intellect, while night inspires the unhampered imagination. Schlegel’s imagination contemporaries evidently agreed, as is attested by John Field and Frédéric Chopin’s nocturnes for solo piano […].

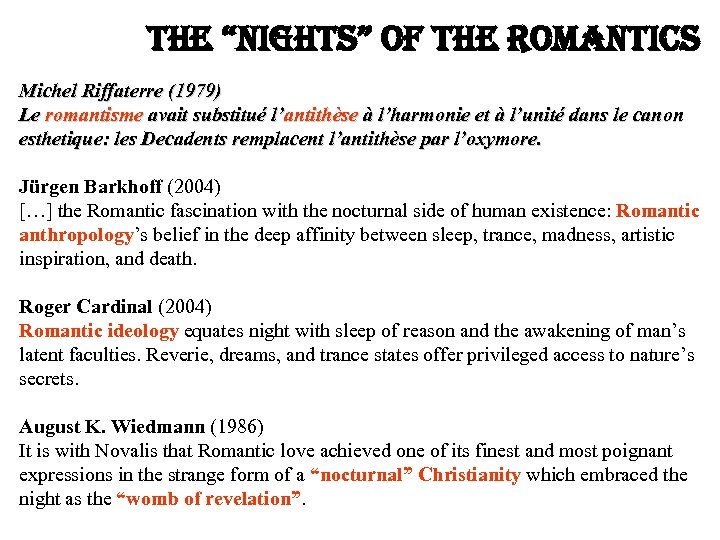

the “nights” of the romantics Michel Riffaterre (1979) Le romantisme avait substitué l’antithèse à l’harmonie et à l’unité dans le canon esthetique: les Decadents remplacent l’antithèse par l’oxymore. Jürgen Barkhoff (2004) […] the Romantic fascination with the nocturnal side of human existence: Romantic anthropology’s belief in the deep affinity between sleep, trance, madness, artistic inspiration, and death. Roger Cardinal (2004) Romantic ideology equates night with sleep of reason and the awakening of man’s latent faculties. Reverie, dreams, and trance states offer privileged access to nature’s secrets. August K. Wiedmann (1986) It is with Novalis that Romantic love achieved one of its finest and most poignant expressions in the strange form of a “nocturnal” Christianity which embraced the night as the “womb of revelation”.

the “nights” of the romantics Michel Riffaterre (1979) Le romantisme avait substitué l’antithèse à l’harmonie et à l’unité dans le canon esthetique: les Decadents remplacent l’antithèse par l’oxymore. Jürgen Barkhoff (2004) […] the Romantic fascination with the nocturnal side of human existence: Romantic anthropology’s belief in the deep affinity between sleep, trance, madness, artistic inspiration, and death. Roger Cardinal (2004) Romantic ideology equates night with sleep of reason and the awakening of man’s latent faculties. Reverie, dreams, and trance states offer privileged access to nature’s secrets. August K. Wiedmann (1986) It is with Novalis that Romantic love achieved one of its finest and most poignant expressions in the strange form of a “nocturnal” Christianity which embraced the night as the “womb of revelation”.

the “nights” of the “celtic” romantics James Thomson, Liberty (1736), Part IV Now turn your view, and mark from Celtic night To present grandeur how my Britain rose. Bold were those Britons, who, the careless sons Of Nature, roam'd the forest-bounds, at once Their verdant city, high-embowering fane, And the gay circle of their woodland wars: For by the Druid taught, that death but shifts [outlawed by emperor Claudius in 54 AD] The vital scene, they that prime fear despised; And, prone to rush on steel, disdain'd to spare An ill saved life that must again return. Edmund Burke, Philos. Enq. (1756), Part II, Sect. XV I think then, that all edifices calculated to produce an idea of the sublime, ought rather to be dark and gloomy, and this for two reasons; the first is, that darkness itself on other occasions is known by experience to have a greater effect on the passions than light. The second is, that to make an object very striking, we should make it as different as possible from the objects with which we have been immediately conversant […]. Oisín & James Macpherson’s Ossian (1773) [countless occurrences…]

the “nights” of the “celtic” romantics James Thomson, Liberty (1736), Part IV Now turn your view, and mark from Celtic night To present grandeur how my Britain rose. Bold were those Britons, who, the careless sons Of Nature, roam'd the forest-bounds, at once Their verdant city, high-embowering fane, And the gay circle of their woodland wars: For by the Druid taught, that death but shifts [outlawed by emperor Claudius in 54 AD] The vital scene, they that prime fear despised; And, prone to rush on steel, disdain'd to spare An ill saved life that must again return. Edmund Burke, Philos. Enq. (1756), Part II, Sect. XV I think then, that all edifices calculated to produce an idea of the sublime, ought rather to be dark and gloomy, and this for two reasons; the first is, that darkness itself on other occasions is known by experience to have a greater effect on the passions than light. The second is, that to make an object very striking, we should make it as different as possible from the objects with which we have been immediately conversant […]. Oisín & James Macpherson’s Ossian (1773) [countless occurrences…]

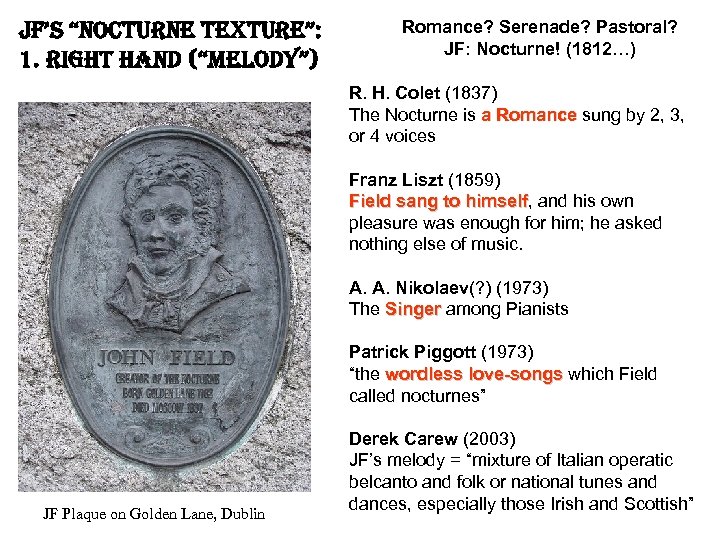

jf’s “nocturne texture”: 1. right hand (“melody”) Romance? Serenade? Pastoral? JF: Nocturne! (1812…) R. H. Colet (1837) The Nocturne is a Romance sung by 2, 3, or 4 voices Franz Liszt (1859) Field sang to himself, and his own himself pleasure was enough for him; he asked nothing else of music. A. A. Nikolaev(? ) (1973) The Singer among Pianists Patrick Piggott (1973) “the wordless love-songs which Field called nocturnes” JF Plaque on Golden Lane, Dublin Derek Carew (2003) JF’s melody = “mixture of Italian operatic belcanto and folk or national tunes and dances, especially those Irish and Scottish”

jf’s “nocturne texture”: 1. right hand (“melody”) Romance? Serenade? Pastoral? JF: Nocturne! (1812…) R. H. Colet (1837) The Nocturne is a Romance sung by 2, 3, or 4 voices Franz Liszt (1859) Field sang to himself, and his own himself pleasure was enough for him; he asked nothing else of music. A. A. Nikolaev(? ) (1973) The Singer among Pianists Patrick Piggott (1973) “the wordless love-songs which Field called nocturnes” JF Plaque on Golden Lane, Dublin Derek Carew (2003) JF’s melody = “mixture of Italian operatic belcanto and folk or national tunes and dances, especially those Irish and Scottish”

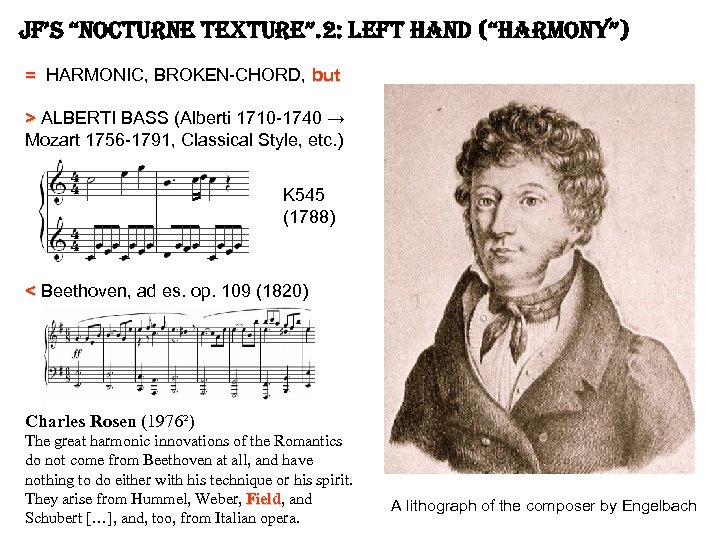

jf’s “nocturne texture”. 2: left hand (“harmony”) = HARMONIC, BROKEN-CHORD, but > ALBERTI BASS (Alberti 1710 -1740 → Mozart 1756 -1791, Classical Style, etc. ) K 545 (1788) < Beethoven, ad es. op. 109 (1820) Charles Rosen (1976²) The great harmonic innovations of the Romantics do not come from Beethoven at all, and have nothing to do either with his technique or his spirit. They arise from Hummel, Weber, Field, and Field Schubert […], and, too, from Italian opera. A lithograph of the composer by Engelbach

jf’s “nocturne texture”. 2: left hand (“harmony”) = HARMONIC, BROKEN-CHORD, but > ALBERTI BASS (Alberti 1710 -1740 → Mozart 1756 -1791, Classical Style, etc. ) K 545 (1788) < Beethoven, ad es. op. 109 (1820) Charles Rosen (1976²) The great harmonic innovations of the Romantics do not come from Beethoven at all, and have nothing to do either with his technique or his spirit. They arise from Hummel, Weber, Field, and Field Schubert […], and, too, from Italian opera. A lithograph of the composer by Engelbach

JF’s REZEPTIONs. GEs. CHICHTE Quiz: perché è ignorato il ruolo musicoletterario dei Nocturnes dell’irlandese JF? Scegliete una (o più di una) risposta tra le seguenti (qui sinteticamente formulate): 1) Perché la storia della sua ricezione incrocia quella della Guerra Fredda. 2) Per la non benevola influenza (diretta e indiretta) dell’Inghilterra nella fissazione del codice culturale anglofono per il XIX secolo (e oltre). 3) Per una certa “reticenza” adottata dalla cultura inglese del XIX secolo nei confronti della cultura musicale-musicologica. 4) Altre risposte altrettanto plausibili che lascio all’intelligenza dell’uditorio… Soluzione del quiz: tutte le risposte insieme e qualche altra che non ho il tempo di menzionare in questa sede… Ritratto da Hulton-Archive (1820)

JF’s REZEPTIONs. GEs. CHICHTE Quiz: perché è ignorato il ruolo musicoletterario dei Nocturnes dell’irlandese JF? Scegliete una (o più di una) risposta tra le seguenti (qui sinteticamente formulate): 1) Perché la storia della sua ricezione incrocia quella della Guerra Fredda. 2) Per la non benevola influenza (diretta e indiretta) dell’Inghilterra nella fissazione del codice culturale anglofono per il XIX secolo (e oltre). 3) Per una certa “reticenza” adottata dalla cultura inglese del XIX secolo nei confronti della cultura musicale-musicologica. 4) Altre risposte altrettanto plausibili che lascio all’intelligenza dell’uditorio… Soluzione del quiz: tutte le risposte insieme e qualche altra che non ho il tempo di menzionare in questa sede… Ritratto da Hulton-Archive (1820)

Murray Perahia (1947 -), “The Poet of the Piano” A: Performance interests me less than the idea behind it, and the idea behind it should be these great ideas of counterpoint and harmony Q: You are Jewish and say you are not observant. Yet your family has a house in observant Jerusalem, you teach in a music school there and one of your sons served in the Israeli army. Is there a message of support for Israel in this? A: I don't agree with everything, with their policies. My feelings come strictly from culture. I feel the Judaeo-Christian culture [. . . ] can't exist without input from this way of thinking and one has to cultivate it. I'm not observant [. . . ] but I do think the roots of music lie in religion and that doesn't mean you should be religious [. . . ]. I think you can't get there by just practicing, playing notes and living a hermetic life as a musician. You have to know from where these ideas came.

Murray Perahia (1947 -), “The Poet of the Piano” A: Performance interests me less than the idea behind it, and the idea behind it should be these great ideas of counterpoint and harmony Q: You are Jewish and say you are not observant. Yet your family has a house in observant Jerusalem, you teach in a music school there and one of your sons served in the Israeli army. Is there a message of support for Israel in this? A: I don't agree with everything, with their policies. My feelings come strictly from culture. I feel the Judaeo-Christian culture [. . . ] can't exist without input from this way of thinking and one has to cultivate it. I'm not observant [. . . ] but I do think the roots of music lie in religion and that doesn't mean you should be religious [. . . ]. I think you can't get there by just practicing, playing notes and living a hermetic life as a musician. You have to know from where these ideas came.