03668ec0beb338713f36db6c9fa1a98e.ppt

- Количество слайдов: 84

Prof Steve Dinham Research Director Teaching, Learning and Leadership

Prof Steve Dinham Research Director Teaching, Learning and Leadership

“The chains of habit are too weak to be felt until they are too strong to be broken. ” Dr Samuel Johnson Much of what we do in education is the result of taken-for-granted routines, habits, mind-sets, ideologies, superstitions and untested assumptions and beliefs. However, we are now in the age of evidence and we need to ask some hard questions (what? , why? , how? , effects? ). Is your school in a groove or a rut? 2

“The chains of habit are too weak to be felt until they are too strong to be broken. ” Dr Samuel Johnson Much of what we do in education is the result of taken-for-granted routines, habits, mind-sets, ideologies, superstitions and untested assumptions and beliefs. However, we are now in the age of evidence and we need to ask some hard questions (what? , why? , how? , effects? ). Is your school in a groove or a rut? 2

“ …the focus of every school, every educational system and every education department or faculty of education – [should be] student learning and achievement. ” Dinham, 2008: 1). 3

“ …the focus of every school, every educational system and every education department or faculty of education – [should be] student learning and achievement. ” Dinham, 2008: 1). 3

The Declaration articulates two important goals for education in Australia: ◦ Goal 1: Australian schooling promotes equity and excellence ◦ Goal 2: All young Australians become: ■ successful learners ■ confident and creative individuals ■ active and informed citizens. 4

The Declaration articulates two important goals for education in Australia: ◦ Goal 1: Australian schooling promotes equity and excellence ◦ Goal 2: All young Australians become: ■ successful learners ■ confident and creative individuals ■ active and informed citizens. 4

Background Until the mid-1960 s the view was that schools make almost no difference to student achievement, which was largely pre -determined by socio-economic status, family circumstances and innate ability (Coleman Report, 1966). However, research has powerfully refuted that view. We now know that teachers, teaching and schools make a significant difference to student success. 5

Background Until the mid-1960 s the view was that schools make almost no difference to student achievement, which was largely pre -determined by socio-economic status, family circumstances and innate ability (Coleman Report, 1966). However, research has powerfully refuted that view. We now know that teachers, teaching and schools make a significant difference to student success. 5

Background As a result, there has been a major international emphasis on improving the quality of teachers and teaching since the 1980 s. We now know how teacher expertise develops and we know what good teaching looks like. However we also know that teacher quality varies within schools and across the nation. A quality teacher in every classroom is the ultimate aim, but how to achieve this is the big question and challenge. 6

Background As a result, there has been a major international emphasis on improving the quality of teachers and teaching since the 1980 s. We now know how teacher expertise develops and we know what good teaching looks like. However we also know that teacher quality varies within schools and across the nation. A quality teacher in every classroom is the ultimate aim, but how to achieve this is the big question and challenge. 6

‘. . . the most important factor affecting student learning is the teacher. . The immediate and clear implication of this finding is that seemingly more can be done to improve education by improving the effectiveness of teachers than by any other single factor’. Wright, S. ; Horn, S. & Sanders, W. (1997). 'Teacher and Classroom Context Effects on Student Achievement: Implications for Teacher Evaluation', Journal of Personnel Evaluation in Education, 11, pp. 57 -67. 7

‘. . . the most important factor affecting student learning is the teacher. . The immediate and clear implication of this finding is that seemingly more can be done to improve education by improving the effectiveness of teachers than by any other single factor’. Wright, S. ; Horn, S. & Sanders, W. (1997). 'Teacher and Classroom Context Effects on Student Achievement: Implications for Teacher Evaluation', Journal of Personnel Evaluation in Education, 11, pp. 57 -67. 7

8

8

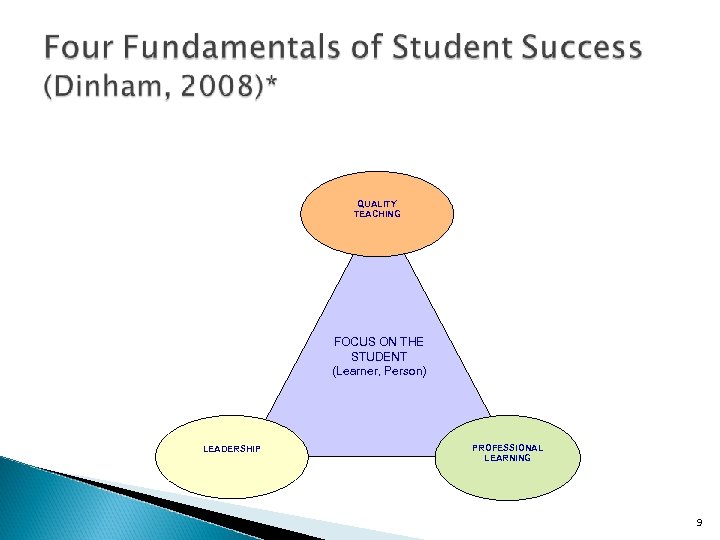

QUALITY TEACHING FOCUS ON THE STUDENT (Learner, Person) LEADERSHIP PROFESSIONAL LEARNING 9

QUALITY TEACHING FOCUS ON THE STUDENT (Learner, Person) LEADERSHIP PROFESSIONAL LEARNING 9

Student Learning and Achievement Quality Teaching in Action Professional Learning Leadership for Quality Teaching and Learning 10

Student Learning and Achievement Quality Teaching in Action Professional Learning Leadership for Quality Teaching and Learning 10

What Does Current Research Tell Us?

What Does Current Research Tell Us?

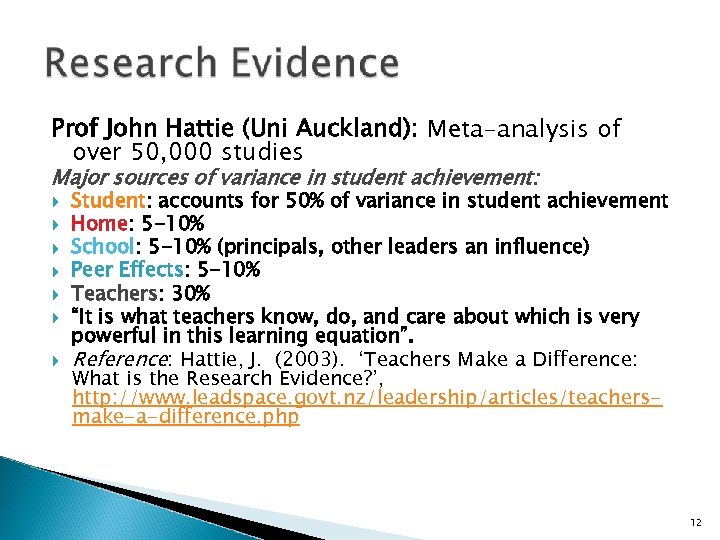

Prof John Hattie (Uni Auckland): Meta-analysis of over 50, 000 studies Major sources of variance in student achievement: Student: accounts for 50% of variance in student achievement Home: 5 -10% School: 5 -10% (principals, other leaders an influence) Peer Effects: 5 -10% Teachers: 30% “It is what teachers know, do, and care about which is very powerful in this learning equation”. Reference: Hattie, J. (2003). ‘Teachers Make a Difference: What is the Research Evidence? ’, http: //www. leadspace. govt. nz/leadership/articles/teachersmake-a-difference. php 12

Prof John Hattie (Uni Auckland): Meta-analysis of over 50, 000 studies Major sources of variance in student achievement: Student: accounts for 50% of variance in student achievement Home: 5 -10% School: 5 -10% (principals, other leaders an influence) Peer Effects: 5 -10% Teachers: 30% “It is what teachers know, do, and care about which is very powerful in this learning equation”. Reference: Hattie, J. (2003). ‘Teachers Make a Difference: What is the Research Evidence? ’, http: //www. leadspace. govt. nz/leadership/articles/teachersmake-a-difference. php 12

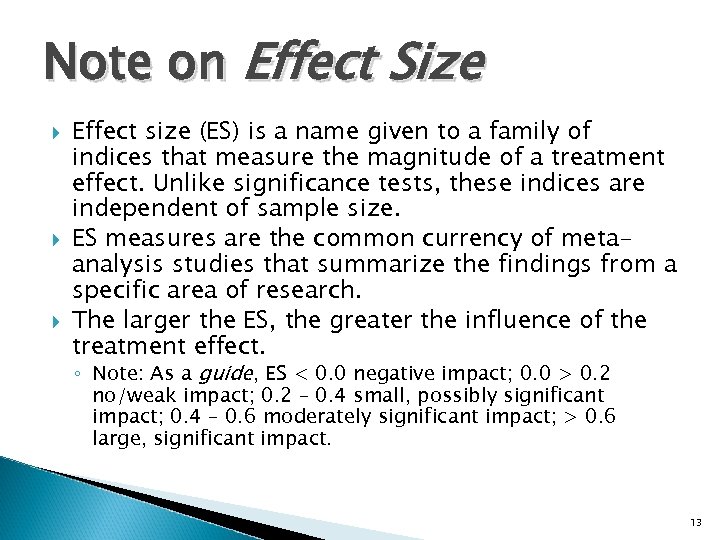

Note on Effect Size Effect size (ES) is a name given to a family of indices that measure the magnitude of a treatment effect. Unlike significance tests, these indices are independent of sample size. ES measures are the common currency of metaanalysis studies that summarize the findings from a specific area of research. The larger the ES, the greater the influence of the treatment effect. ◦ Note: As a guide, ES < 0. 0 negative impact; 0. 0 > 0. 2 no/weak impact; 0. 2 – 0. 4 small, possibly significant impact; 0. 4 – 0. 6 moderately significant impact; > 0. 6 large, significant impact. 13

Note on Effect Size Effect size (ES) is a name given to a family of indices that measure the magnitude of a treatment effect. Unlike significance tests, these indices are independent of sample size. ES measures are the common currency of metaanalysis studies that summarize the findings from a specific area of research. The larger the ES, the greater the influence of the treatment effect. ◦ Note: As a guide, ES < 0. 0 negative impact; 0. 0 > 0. 2 no/weak impact; 0. 2 – 0. 4 small, possibly significant impact; 0. 4 – 0. 6 moderately significant impact; > 0. 6 large, significant impact. 13

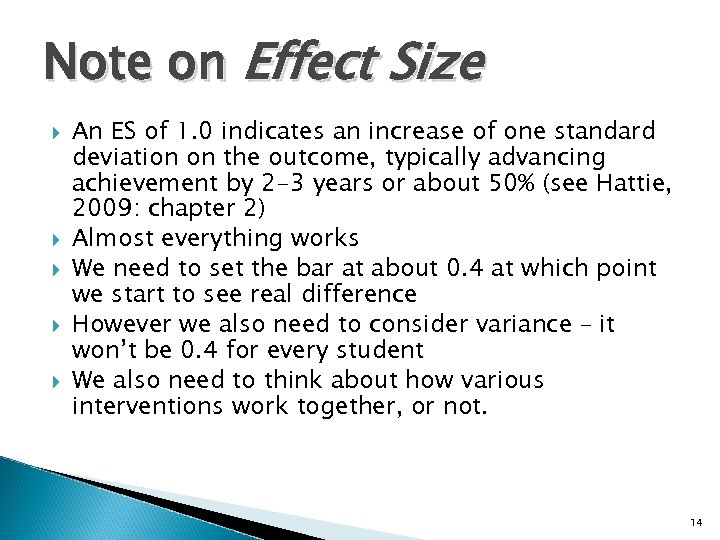

Note on Effect Size An ES of 1. 0 indicates an increase of one standard deviation on the outcome, typically advancing achievement by 2 -3 years or about 50% (see Hattie, 2009: chapter 2) Almost everything works We need to set the bar at about 0. 4 at which point we start to see real difference However we also need to consider variance – it won’t be 0. 4 for every student We also need to think about how various interventions work together, or not. 14

Note on Effect Size An ES of 1. 0 indicates an increase of one standard deviation on the outcome, typically advancing achievement by 2 -3 years or about 50% (see Hattie, 2009: chapter 2) Almost everything works We need to set the bar at about 0. 4 at which point we start to see real difference However we also need to consider variance – it won’t be 0. 4 for every student We also need to think about how various interventions work together, or not. 14

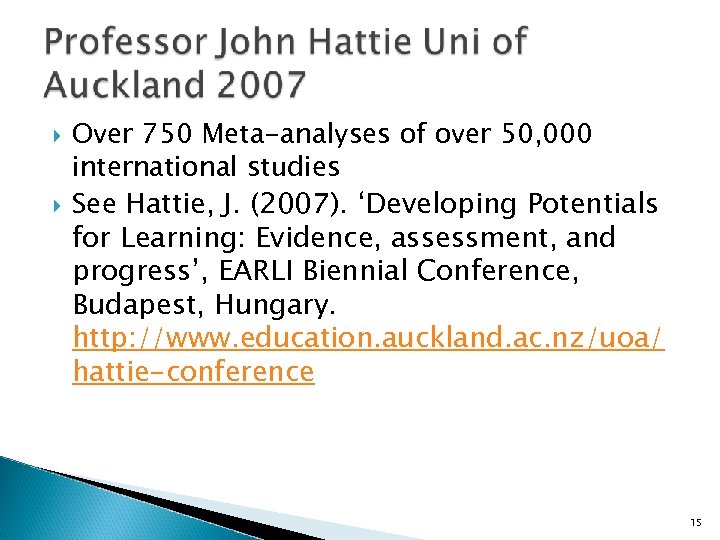

Over 750 Meta-analyses of over 50, 000 international studies See Hattie, J. (2007). ‘Developing Potentials for Learning: Evidence, assessment, and progress’, EARLI Biennial Conference, Budapest, Hungary. http: //www. education. auckland. ac. nz/uoa/ hattie-conference 15

Over 750 Meta-analyses of over 50, 000 international studies See Hattie, J. (2007). ‘Developing Potentials for Learning: Evidence, assessment, and progress’, EARLI Biennial Conference, Budapest, Hungary. http: //www. education. auckland. ac. nz/uoa/ hattie-conference 15

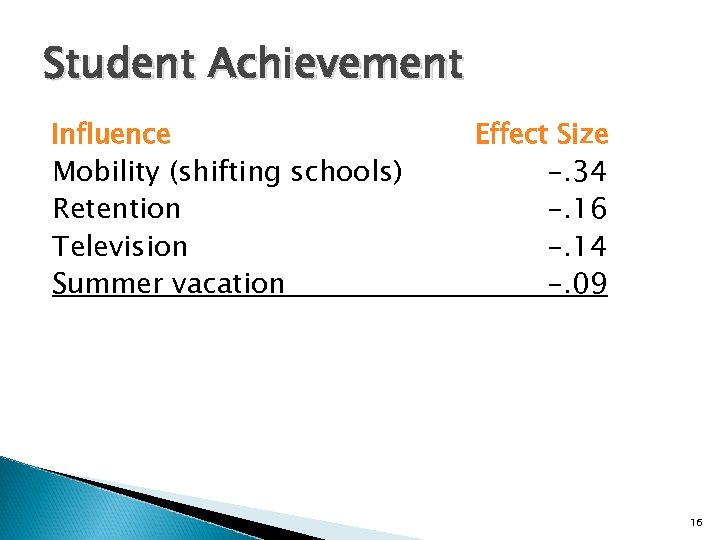

Student Achievement Influence Mobility (shifting schools) Retention Television Summer vacation Effect Size -. 34 -. 16 -. 14 -. 09 16

Student Achievement Influence Mobility (shifting schools) Retention Television Summer vacation Effect Size -. 34 -. 16 -. 14 -. 09 16

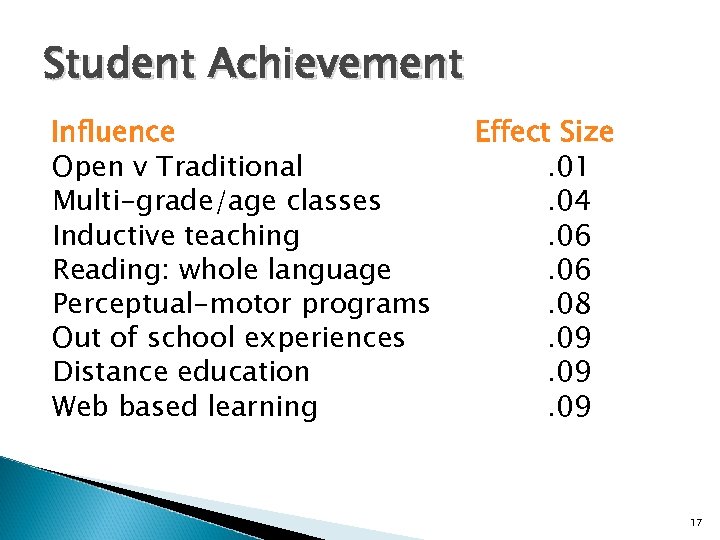

Student Achievement Influence Open v Traditional Multi-grade/age classes Inductive teaching Reading: whole language Perceptual-motor programs Out of school experiences Distance education Web based learning Effect Size. 01. 04. 06. 08. 09. 09 17

Student Achievement Influence Open v Traditional Multi-grade/age classes Inductive teaching Reading: whole language Perceptual-motor programs Out of school experiences Distance education Web based learning Effect Size. 01. 04. 06. 08. 09. 09 17

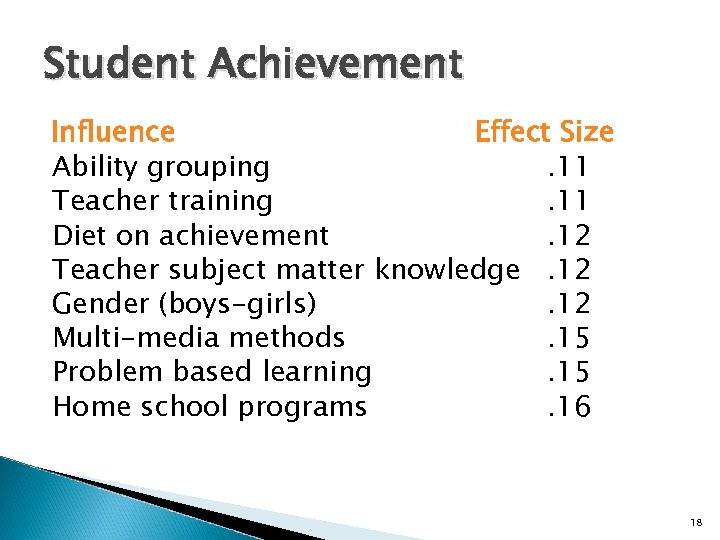

Student Achievement Influence Effect Size Ability grouping. 11 Teacher training. 11 Diet on achievement. 12 Teacher subject matter knowledge. 12 Gender (boys-girls). 12 Multi-media methods. 15 Problem based learning. 15 Home school programs. 16 18

Student Achievement Influence Effect Size Ability grouping. 11 Teacher training. 11 Diet on achievement. 12 Teacher subject matter knowledge. 12 Gender (boys-girls). 12 Multi-media methods. 15 Problem based learning. 15 Home school programs. 16 18

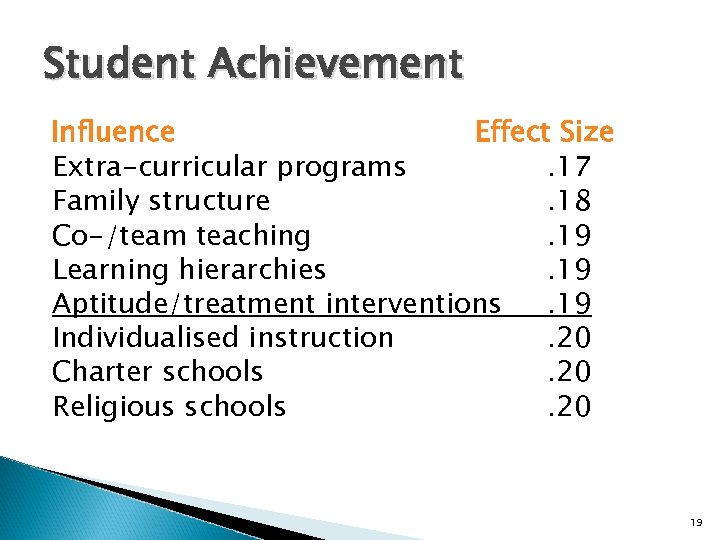

Student Achievement Influence Effect Size Extra-curricular programs. 17 Family structure. 18 Co-/team teaching. 19 Learning hierarchies. 19 Aptitude/treatment interventions. 19 Individualised instruction. 20 Charter schools. 20 Religious schools. 20 19

Student Achievement Influence Effect Size Extra-curricular programs. 17 Family structure. 18 Co-/team teaching. 19 Learning hierarchies. 19 Aptitude/treatment interventions. 19 Individualised instruction. 20 Charter schools. 20 Religious schools. 20 19

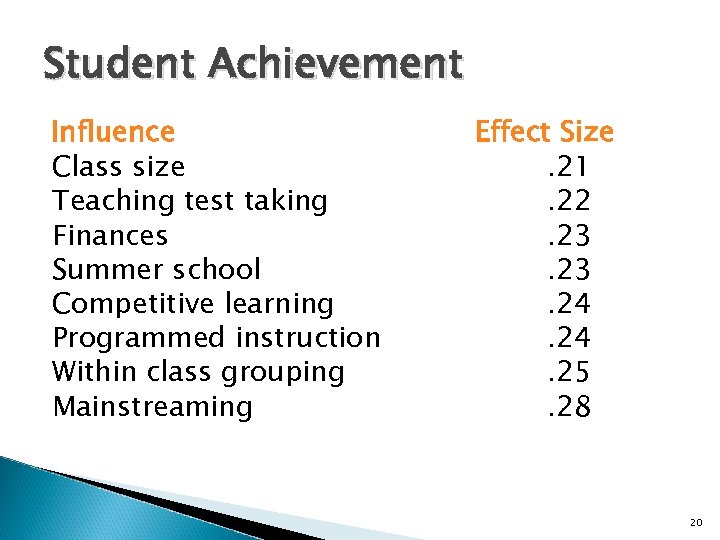

Student Achievement Influence Class size Teaching test taking Finances Summer school Competitive learning Programmed instruction Within class grouping Mainstreaming Effect Size. 21. 22. 23. 24. 25. 28 20

Student Achievement Influence Class size Teaching test taking Finances Summer school Competitive learning Programmed instruction Within class grouping Mainstreaming Effect Size. 21. 22. 23. 24. 25. 28 20

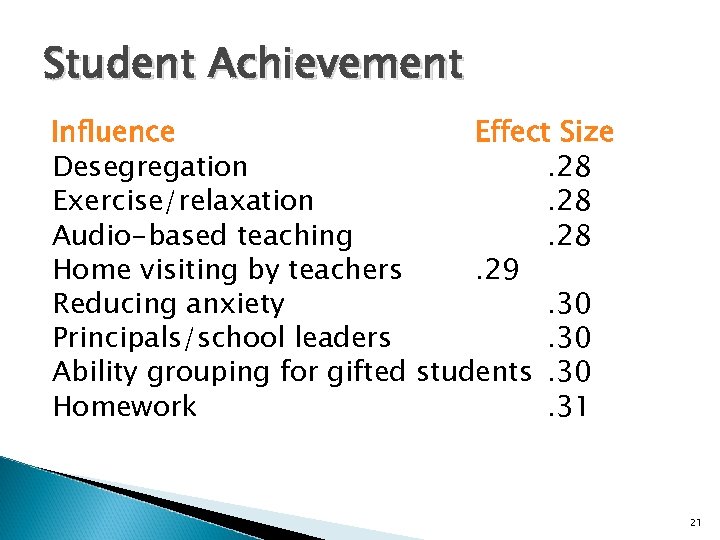

Student Achievement Influence Effect Size Desegregation. 28 Exercise/relaxation. 28 Audio-based teaching. 28 Home visiting by teachers. 29 Reducing anxiety. 30 Principals/school leaders. 30 Ability grouping for gifted students. 30 Homework. 31 21

Student Achievement Influence Effect Size Desegregation. 28 Exercise/relaxation. 28 Audio-based teaching. 28 Home visiting by teachers. 29 Reducing anxiety. 30 Principals/school leaders. 30 Ability grouping for gifted students. 30 Homework. 31 21

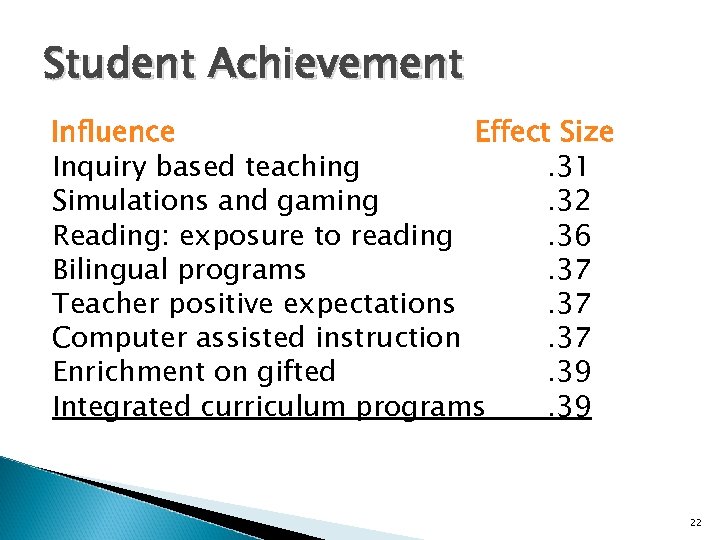

Student Achievement Influence Effect Size Inquiry based teaching. 31 Simulations and gaming. 32 Reading: exposure to reading. 36 Bilingual programs. 37 Teacher positive expectations. 37 Computer assisted instruction. 37 Enrichment on gifted. 39 Integrated curriculum programs. 39 22

Student Achievement Influence Effect Size Inquiry based teaching. 31 Simulations and gaming. 32 Reading: exposure to reading. 36 Bilingual programs. 37 Teacher positive expectations. 37 Computer assisted instruction. 37 Enrichment on gifted. 39 Integrated curriculum programs. 39 22

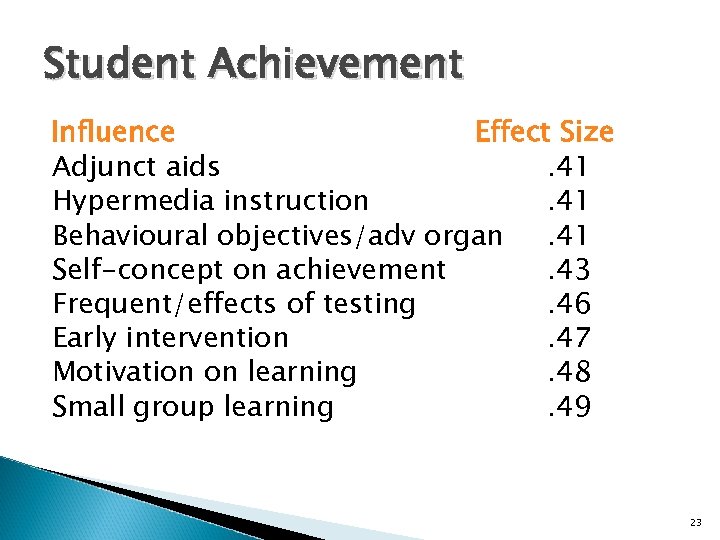

Student Achievement Influence Effect Size Adjunct aids. 41 Hypermedia instruction. 41 Behavioural objectives/adv organ. 41 Self-concept on achievement. 43 Frequent/effects of testing. 46 Early intervention. 47 Motivation on learning. 48 Small group learning. 49 23

Student Achievement Influence Effect Size Adjunct aids. 41 Hypermedia instruction. 41 Behavioural objectives/adv organ. 41 Self-concept on achievement. 43 Frequent/effects of testing. 46 Early intervention. 47 Motivation on learning. 48 Small group learning. 49 23

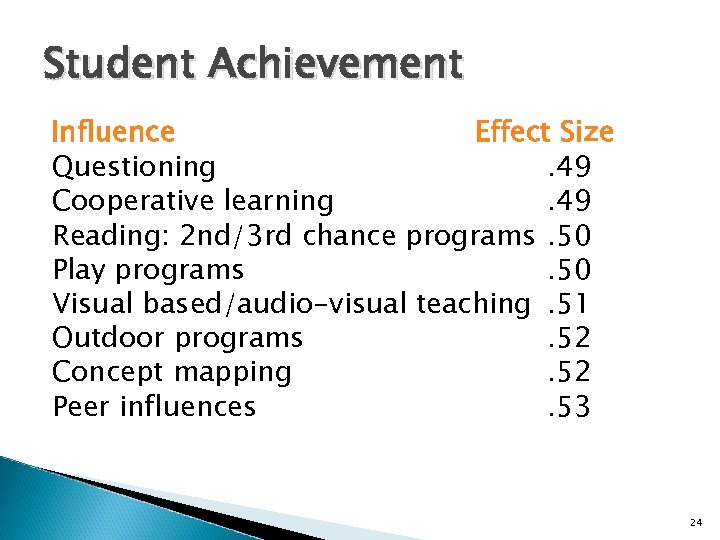

Student Achievement Influence Effect Size Questioning. 49 Cooperative learning. 49 Reading: 2 nd/3 rd chance programs. 50 Play programs. 50 Visual based/audio-visual teaching. 51 Outdoor programs. 52 Concept mapping. 52 Peer influences. 53 24

Student Achievement Influence Effect Size Questioning. 49 Cooperative learning. 49 Reading: 2 nd/3 rd chance programs. 50 Play programs. 50 Visual based/audio-visual teaching. 51 Outdoor programs. 52 Concept mapping. 52 Peer influences. 53 24

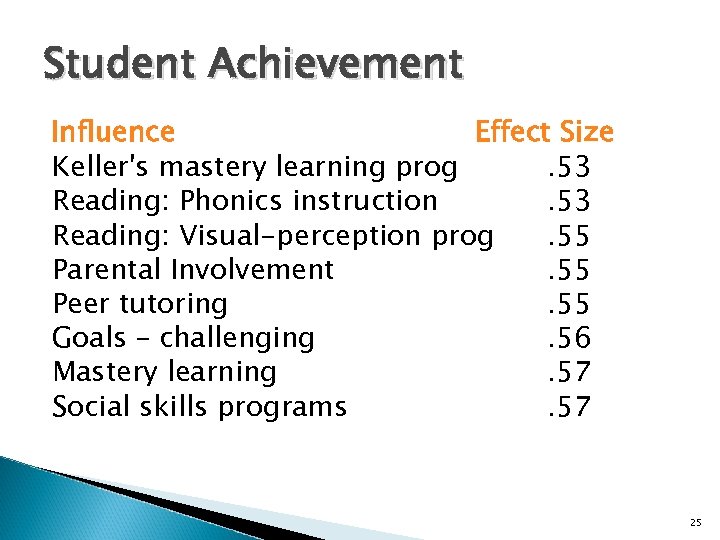

Student Achievement Influence Effect Size Keller's mastery learning prog. 53 Reading: Phonics instruction. 53 Reading: Visual-perception prog. 55 Parental Involvement. 55 Peer tutoring. 55 Goals – challenging. 56 Mastery learning. 57 Social skills programs. 57 25

Student Achievement Influence Effect Size Keller's mastery learning prog. 53 Reading: Phonics instruction. 53 Reading: Visual-perception prog. 55 Parental Involvement. 55 Peer tutoring. 55 Goals – challenging. 56 Mastery learning. 57 Social skills programs. 57 25

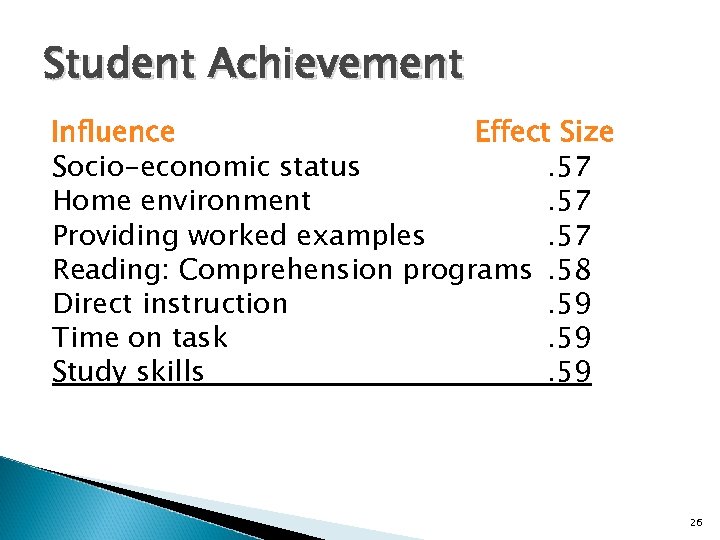

Student Achievement Influence Effect Size Socio-economic status. 57 Home environment. 57 Providing worked examples. 57 Reading: Comprehension programs. 58 Direct instruction. 59 Time on task. 59 Study skills. 59 26

Student Achievement Influence Effect Size Socio-economic status. 57 Home environment. 57 Providing worked examples. 57 Reading: Comprehension programs. 58 Direct instruction. 59 Time on task. 59 Study skills. 59 26

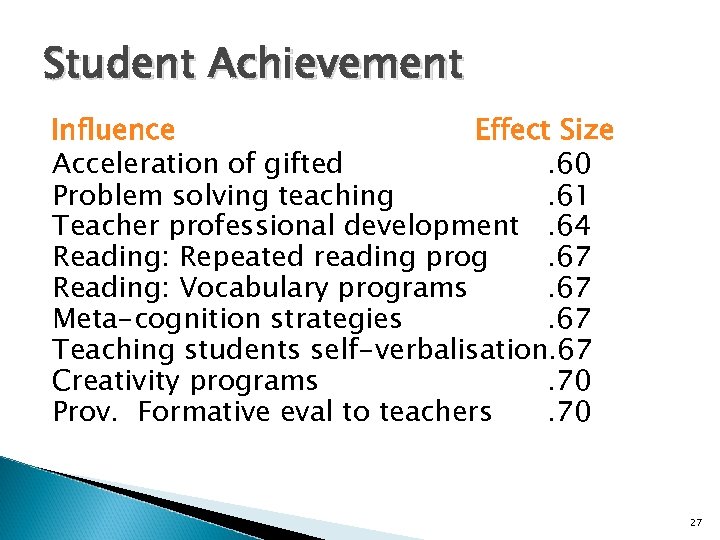

Student Achievement Influence Effect Size Acceleration of gifted. 60 Problem solving teaching. 61 Teacher professional development. 64 Reading: Repeated reading prog. 67 Reading: Vocabulary programs. 67 Meta-cognition strategies. 67 Teaching students self-verbalisation. 67 Creativity programs. 70 Prov. Formative eval to teachers. 70 27

Student Achievement Influence Effect Size Acceleration of gifted. 60 Problem solving teaching. 61 Teacher professional development. 64 Reading: Repeated reading prog. 67 Reading: Vocabulary programs. 67 Meta-cognition strategies. 67 Teaching students self-verbalisation. 67 Creativity programs. 70 Prov. Formative eval to teachers. 70 27

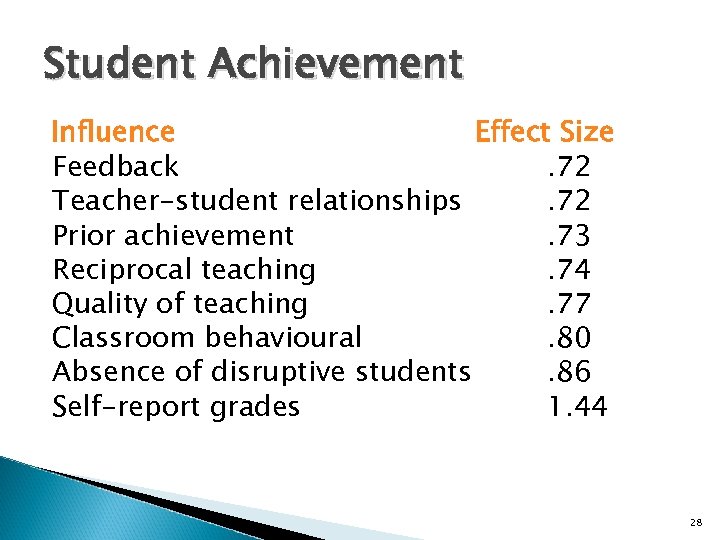

Student Achievement Influence Effect Size Feedback. 72 Teacher-student relationships. 72 Prior achievement. 73 Reciprocal teaching. 74 Quality of teaching. 77 Classroom behavioural. 80 Absence of disruptive students. 86 Self-report grades 1. 44 28

Student Achievement Influence Effect Size Feedback. 72 Teacher-student relationships. 72 Prior achievement. 73 Reciprocal teaching. 74 Quality of teaching. 77 Classroom behavioural. 80 Absence of disruptive students. 86 Self-report grades 1. 44 28

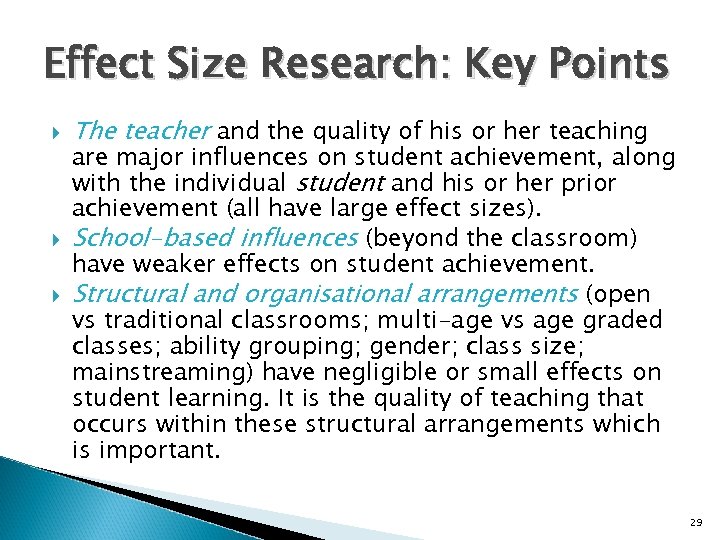

Effect Size Research: Key Points The teacher and the quality of his or her teaching are major influences on student achievement, along with the individual student and his or her prior achievement (all have large effect sizes). School-based influences (beyond the classroom) have weaker effects on student achievement. Structural and organisational arrangements (open vs traditional classrooms; multi-age vs age graded classes; ability grouping; gender; class size; mainstreaming) have negligible or small effects on student learning. It is the quality of teaching that occurs within these structural arrangements which is important. 29

Effect Size Research: Key Points The teacher and the quality of his or her teaching are major influences on student achievement, along with the individual student and his or her prior achievement (all have large effect sizes). School-based influences (beyond the classroom) have weaker effects on student achievement. Structural and organisational arrangements (open vs traditional classrooms; multi-age vs age graded classes; ability grouping; gender; class size; mainstreaming) have negligible or small effects on student learning. It is the quality of teaching that occurs within these structural arrangements which is important. 29

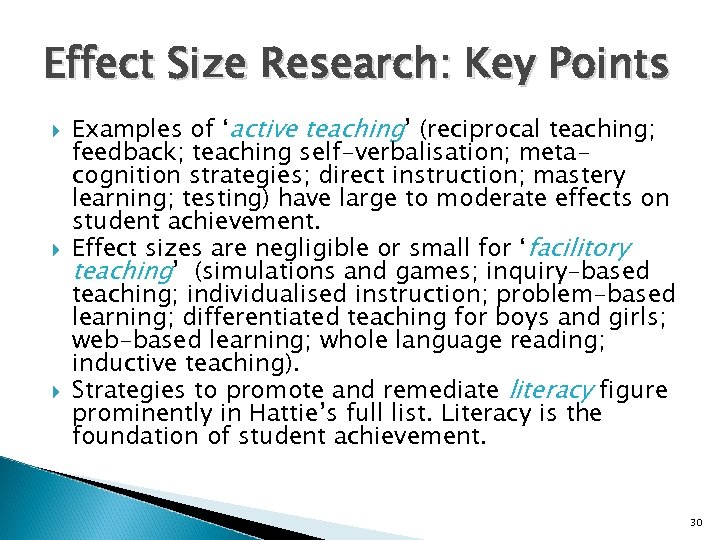

Effect Size Research: Key Points Examples of ‘active teaching’ (reciprocal teaching; feedback; teaching self-verbalisation; metacognition strategies; direct instruction; mastery learning; testing) have large to moderate effects on student achievement. Effect sizes are negligible or small for ‘facilitory teaching’ (simulations and games; inquiry-based teaching; individualised instruction; problem-based learning; differentiated teaching for boys and girls; web-based learning; whole language reading; inductive teaching). Strategies to promote and remediate literacy figure prominently in Hattie’s full list. Literacy is the foundation of student achievement. 30

Effect Size Research: Key Points Examples of ‘active teaching’ (reciprocal teaching; feedback; teaching self-verbalisation; metacognition strategies; direct instruction; mastery learning; testing) have large to moderate effects on student achievement. Effect sizes are negligible or small for ‘facilitory teaching’ (simulations and games; inquiry-based teaching; individualised instruction; problem-based learning; differentiated teaching for boys and girls; web-based learning; whole language reading; inductive teaching). Strategies to promote and remediate literacy figure prominently in Hattie’s full list. Literacy is the foundation of student achievement. 30

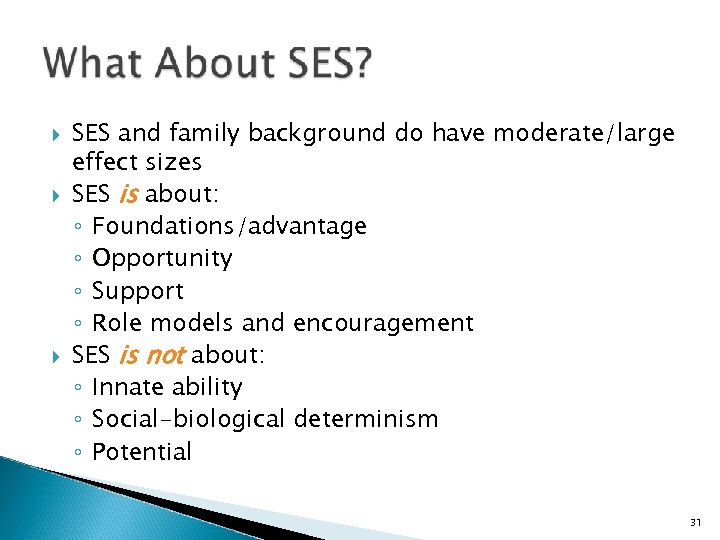

SES and family background do have moderate/large effect sizes SES is about: ◦ Foundations/advantage ◦ Opportunity ◦ Support ◦ Role models and encouragement SES is not about: ◦ Innate ability ◦ Social-biological determinism ◦ Potential 31

SES and family background do have moderate/large effect sizes SES is about: ◦ Foundations/advantage ◦ Opportunity ◦ Support ◦ Role models and encouragement SES is not about: ◦ Innate ability ◦ Social-biological determinism ◦ Potential 31

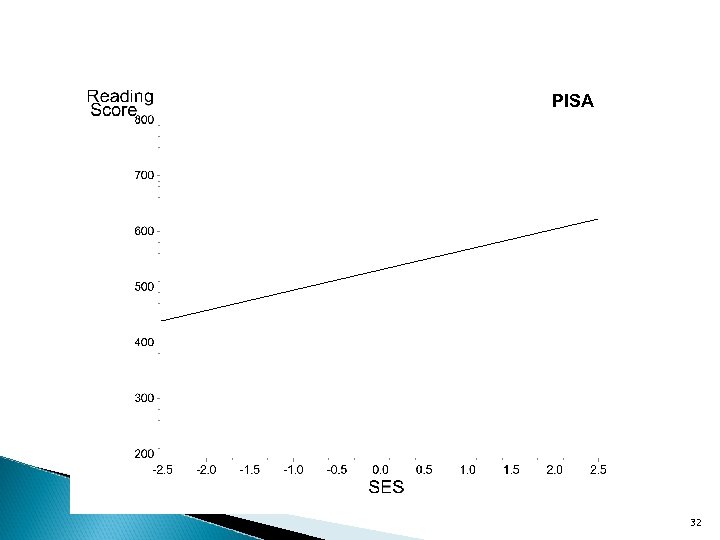

PISA 2000 PISA 32

PISA 2000 PISA 32

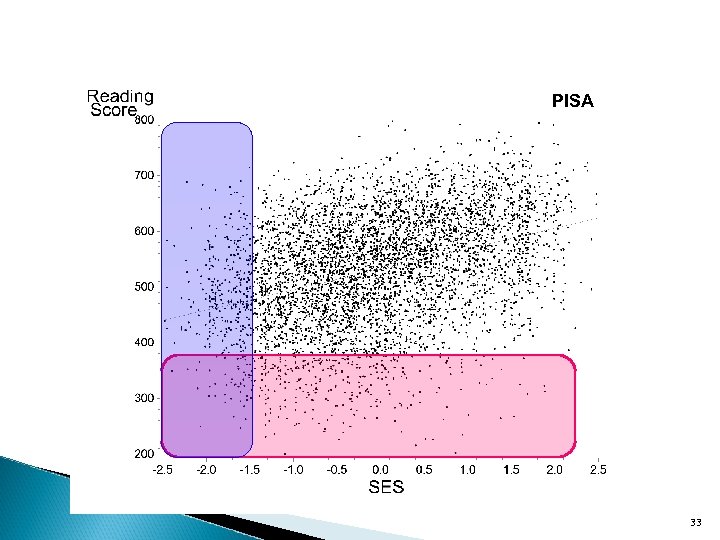

PISA 2000 PISA 33

PISA 2000 PISA 33

Poor student performance is spread across the SES spectrum Schooling represents an obstacle course. Some students have certain advantages and others have obstacles. Life is not fair, but good teaching and good schools can help overcome SES disadvantage 34

Poor student performance is spread across the SES spectrum Schooling represents an obstacle course. Some students have certain advantages and others have obstacles. Life is not fair, but good teaching and good schools can help overcome SES disadvantage 34

“ … school improvement by itself has potential to make an enormous difference in the lives of children even if broader social change is slow in coming. The children who depend most on good schooling for academic growth are the least likely to receive it. If school improvement begins early in life and if sustained, the most disadvantaged children stand to benefit most. This reasoning suggests that increasing the amount and the quality of schooling to which these children have access would reduce inequality in academic achievement. ” 35

“ … school improvement by itself has potential to make an enormous difference in the lives of children even if broader social change is slow in coming. The children who depend most on good schooling for academic growth are the least likely to receive it. If school improvement begins early in life and if sustained, the most disadvantaged children stand to benefit most. This reasoning suggests that increasing the amount and the quality of schooling to which these children have access would reduce inequality in academic achievement. ” 35

Since the 1970 s More than 70 models Psychologists and neuroscientists believe there is little efficacy for these models which rest on dubious grounds Confusion with teaching strategies (as with ‘constructivism’ – see over) “It is hard not to sceptical about these learning preference claims” (Hattie, 2009: 197). Problems caused by categorisation, labelling, limiting learning experiences; potential harm 36

Since the 1970 s More than 70 models Psychologists and neuroscientists believe there is little efficacy for these models which rest on dubious grounds Confusion with teaching strategies (as with ‘constructivism’ – see over) “It is hard not to sceptical about these learning preference claims” (Hattie, 2009: 197). Problems caused by categorisation, labelling, limiting learning experiences; potential harm 36

“… one of the most damaging things we can do to people is to put them into categories and treat them accordingly. ” (Dinham, 2008: 2) 37

“… one of the most damaging things we can do to people is to put them into categories and treat them accordingly. ” (Dinham, 2008: 2) 37

‘As constructivism has become the dominant view of how students learn, it may seem obvious to equate active learning with active methods of instruction. Thus, educators who wish to use constructivist methods of instruction are often encouraged to focus on discovery learning – in which students are free to work in a learning environment with little or no guidance. Under the banner of social constructivism, the call for discovery learning remains, but with a modest shift in form – students are expected to work in groups in a learning environment with little or no guidance. … The research in this brief review shows that the formula constructivism = hands-on activity is a formula for educational disaster’. ◦ Mayer, R. (2004). Should there be a three-strikes rule against pure Discovery Learning? , American Psychologist, 59(1) , 14 -19. 38

‘As constructivism has become the dominant view of how students learn, it may seem obvious to equate active learning with active methods of instruction. Thus, educators who wish to use constructivist methods of instruction are often encouraged to focus on discovery learning – in which students are free to work in a learning environment with little or no guidance. Under the banner of social constructivism, the call for discovery learning remains, but with a modest shift in form – students are expected to work in groups in a learning environment with little or no guidance. … The research in this brief review shows that the formula constructivism = hands-on activity is a formula for educational disaster’. ◦ Mayer, R. (2004). Should there be a three-strikes rule against pure Discovery Learning? , American Psychologist, 59(1) , 14 -19. 38

1. 2. Ø 3. Carefully explain to students an assignment or learning activity, including key terms and directions. Provide students with the assessment rubric, including criteria and the marking/assessment scale/method for each item/criterion. Optional: Jointly discuss and determine criteria to be used. Students complete the activity (individually or in groups), using rubric as a guide. 39

1. 2. Ø 3. Carefully explain to students an assignment or learning activity, including key terms and directions. Provide students with the assessment rubric, including criteria and the marking/assessment scale/method for each item/criterion. Optional: Jointly discuss and determine criteria to be used. Students complete the activity (individually or in groups), using rubric as a guide. 39

4. Ø 5. 6. Ø Students assess their work using the rubric. Optional: Students assess another student’s work, discuss with student concerned. Teacher assesses each student’s work, providing feedback using rubric. Student and teacher discuss/compare their assessments. One-to-one conferences are powerful 40

4. Ø 5. 6. Ø Students assess their work using the rubric. Optional: Students assess another student’s work, discuss with student concerned. Teacher assesses each student’s work, providing feedback using rubric. Student and teacher discuss/compare their assessments. One-to-one conferences are powerful 40

‘In a nutshell: The teacher decides the learning intentions and success criteria, makes them transparent to the students, demonstrates by modelling, evaluates if they understand what they had been told by checking for understanding, and re-telling them what they had been told by tying it all together with closure. ’ (Hattie, 2009: 205206). ◦ It is a major mistake to confuse direct instruction/explicit teaching with didactic teaching. 41

‘In a nutshell: The teacher decides the learning intentions and success criteria, makes them transparent to the students, demonstrates by modelling, evaluates if they understand what they had been told by checking for understanding, and re-telling them what they had been told by tying it all together with closure. ’ (Hattie, 2009: 205206). ◦ It is a major mistake to confuse direct instruction/explicit teaching with didactic teaching. 41

Feedback “Look at learning or mastery in fields as diverse as sports, the arts, languages, the sciences or recreational activities and it’s easy to see how important feedback is to learning and accomplishment. An expert teacher, mentor or coach can readily explain, demonstrate and detect flaws in performance. He or she can also identify talent and potential, and build on these. In contrast, trial and error learning or poor teaching are less effective and take longer. If performance flaws are not detected and corrected, these can become ingrained and will be much harder to eradicate later. Learners who don’t receive instruction, encouragement and correction can become disillusioned and quit due to lack of progress. ” (Dinham, Feedback on Feedback, 2008) 42

Feedback “Look at learning or mastery in fields as diverse as sports, the arts, languages, the sciences or recreational activities and it’s easy to see how important feedback is to learning and accomplishment. An expert teacher, mentor or coach can readily explain, demonstrate and detect flaws in performance. He or she can also identify talent and potential, and build on these. In contrast, trial and error learning or poor teaching are less effective and take longer. If performance flaws are not detected and corrected, these can become ingrained and will be much harder to eradicate later. Learners who don’t receive instruction, encouragement and correction can become disillusioned and quit due to lack of progress. ” (Dinham, Feedback on Feedback, 2008) 42

Feedback The four questions of Students: 1. What can I do? 2. What can’t I do? 3. How does my work compare with that of others? 4. How can I do better? 43

Feedback The four questions of Students: 1. What can I do? 2. What can’t I do? 3. How does my work compare with that of others? 4. How can I do better? 43

Feedback “When asked to provide evidence and guidance on enhancing the quality of teaching and student performance, I’m usually equivocal about advocating quick fixes … In the case of feedback, however, I’m prepared to state categorically that if you focus on providing students with improved, quality feedback in individual classrooms, departments and schools you’ll have an almost immediate positive effect. The research evidence is clear: great teachers give great feedback, and every teacher is capable of giving more effective feedback. ” (Dinham, Feedback on Feedback, 2008). 44

Feedback “When asked to provide evidence and guidance on enhancing the quality of teaching and student performance, I’m usually equivocal about advocating quick fixes … In the case of feedback, however, I’m prepared to state categorically that if you focus on providing students with improved, quality feedback in individual classrooms, departments and schools you’ll have an almost immediate positive effect. The research evidence is clear: great teachers give great feedback, and every teacher is capable of giving more effective feedback. ” (Dinham, Feedback on Feedback, 2008). 44

G. Nuthall (2007). The Hidden Lives of Learners. Wellington: NZCER. 80% of feedback students receive about their work in primary school comes from other students 80% of this student-student feedback is incorrect. 45

G. Nuthall (2007). The Hidden Lives of Learners. Wellington: NZCER. 80% of feedback students receive about their work in primary school comes from other students 80% of this student-student feedback is incorrect. 45

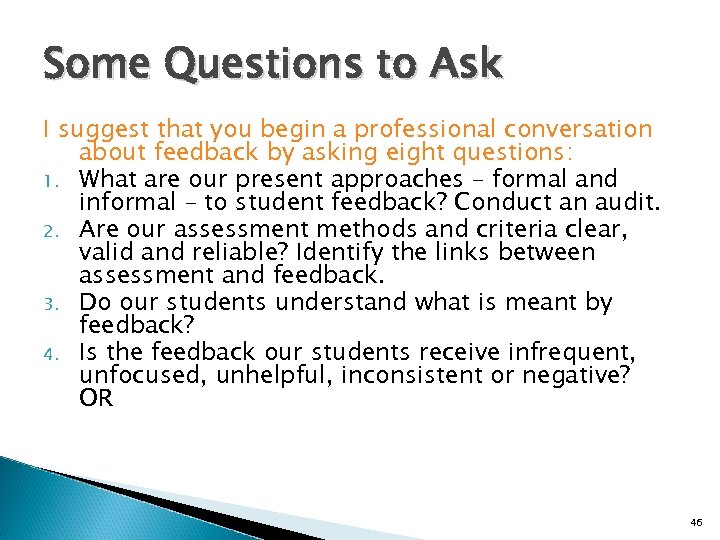

Some Questions to Ask I suggest that you begin a professional conversation about feedback by asking eight questions: 1. What are our present approaches – formal and informal – to student feedback? Conduct an audit. 2. Are our assessment methods and criteria clear, valid and reliable? Identify the links between assessment and feedback. 3. Do our students understand what is meant by feedback? 4. Is the feedback our students receive infrequent, unfocused, unhelpful, inconsistent or negative? OR 46

Some Questions to Ask I suggest that you begin a professional conversation about feedback by asking eight questions: 1. What are our present approaches – formal and informal – to student feedback? Conduct an audit. 2. Are our assessment methods and criteria clear, valid and reliable? Identify the links between assessment and feedback. 3. Do our students understand what is meant by feedback? 4. Is the feedback our students receive infrequent, unfocused, unhelpful, inconsistent or negative? OR 46

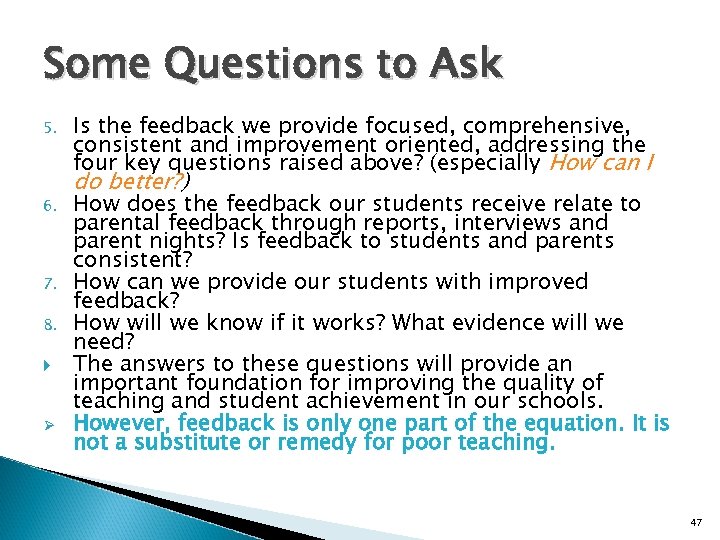

Some Questions to Ask 5. 6. 7. 8. Ø Is the feedback we provide focused, comprehensive, consistent and improvement oriented, addressing the four key questions raised above? (especially How can I do better? ) How does the feedback our students receive relate to parental feedback through reports, interviews and parent nights? Is feedback to students and parents consistent? How can we provide our students with improved feedback? How will we know if it works? What evidence will we need? The answers to these questions will provide an important foundation for improving the quality of teaching and student achievement in our schools. However, feedback is only one part of the equation. It is not a substitute or remedy for poor teaching. 47

Some Questions to Ask 5. 6. 7. 8. Ø Is the feedback we provide focused, comprehensive, consistent and improvement oriented, addressing the four key questions raised above? (especially How can I do better? ) How does the feedback our students receive relate to parental feedback through reports, interviews and parent nights? Is feedback to students and parents consistent? How can we provide our students with improved feedback? How will we know if it works? What evidence will we need? The answers to these questions will provide an important foundation for improving the quality of teaching and student achievement in our schools. However, feedback is only one part of the equation. It is not a substitute or remedy for poor teaching. 47

Case Study: Successful Senior Secondary Teaching

Case Study: Successful Senior Secondary Teaching

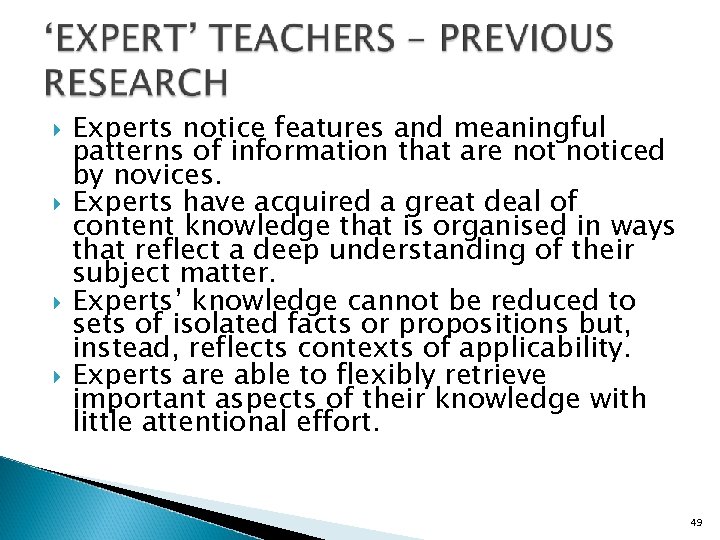

Experts notice features and meaningful patterns of information that are noticed by novices. Experts have acquired a great deal of content knowledge that is organised in ways that reflect a deep understanding of their subject matter. Experts’ knowledge cannot be reduced to sets of isolated facts or propositions but, instead, reflects contexts of applicability. Experts are able to flexibly retrieve important aspects of their knowledge with little attentional effort. 49

Experts notice features and meaningful patterns of information that are noticed by novices. Experts have acquired a great deal of content knowledge that is organised in ways that reflect a deep understanding of their subject matter. Experts’ knowledge cannot be reduced to sets of isolated facts or propositions but, instead, reflects contexts of applicability. Experts are able to flexibly retrieve important aspects of their knowledge with little attentional effort. 49

May appear ‘arational’, intuitive, nonanalytic Understand solve problems at a deeper level ‘Know’ their students; students ‘know’ them Though experts know their disciplines thoroughly, this does not guarantee that they are able to teach others. Both teacher and students have high expectations Experience gained over time important Expert teachers can’t (easily) articulate their practice 50

May appear ‘arational’, intuitive, nonanalytic Understand solve problems at a deeper level ‘Know’ their students; students ‘know’ them Though experts know their disciplines thoroughly, this does not guarantee that they are able to teach others. Both teacher and students have high expectations Experience gained over time important Expert teachers can’t (easily) articulate their practice 50

51

51

identify the relationship between teaching methods and HSC outcomes for students identify the characteristics of successful HSC teaching methodology consider the implications of the study findings for improving teacher efficiency 52

identify the relationship between teaching methods and HSC outcomes for students identify the characteristics of successful HSC teaching methodology consider the implications of the study findings for improving teacher efficiency 52

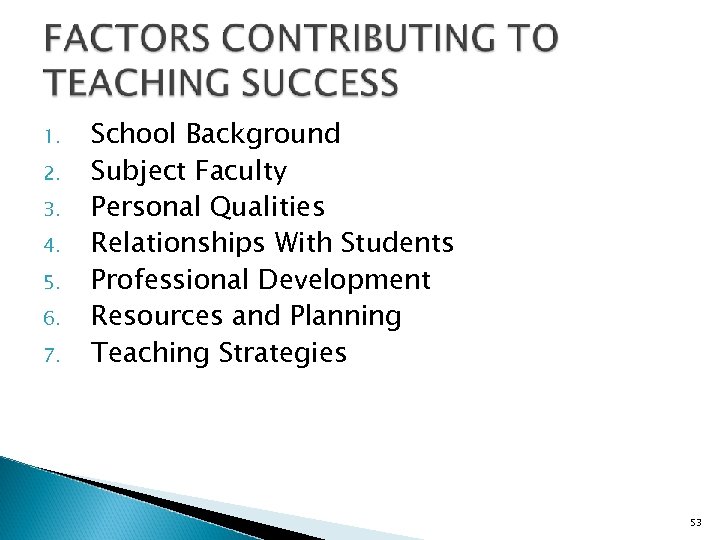

1. 2. 3. 4. 5. 6. 7. School Background Subject Faculty Personal Qualities Relationships With Students Professional Development Resources and Planning Teaching Strategies 53

1. 2. 3. 4. 5. 6. 7. School Background Subject Faculty Personal Qualities Relationships With Students Professional Development Resources and Planning Teaching Strategies 53

Teachers genuinely expert in their subject area(s), and enjoyed teaching Three sorts of knowledge essential: ◦ Subject content knowledge (what subject content to teach) ◦ Subject pedagogic knowledge (how to teach particular subject content) ◦ Subject course knowledge (subject curriculum, assessment, exam knowledge) 54

Teachers genuinely expert in their subject area(s), and enjoyed teaching Three sorts of knowledge essential: ◦ Subject content knowledge (what subject content to teach) ◦ Subject pedagogic knowledge (how to teach particular subject content) ◦ Subject course knowledge (subject curriculum, assessment, exam knowledge) 54

HSC Findings Lessons were student centred and teacher directed. Teachers were highly responsive to students and highly demanding, i. e. authoritative, rather than uninvolved, permissive or authoritarian. Mutual respect, confidence and high expectations. 55

HSC Findings Lessons were student centred and teacher directed. Teachers were highly responsive to students and highly demanding, i. e. authoritative, rather than uninvolved, permissive or authoritarian. Mutual respect, confidence and high expectations. 55

HSC Findings Although wide range of strategies used, key common factor was emphasis on having students think, solve problems and apply knowledge. Understanding built in layers, connections. Frequent assessment and feedback. Teachers saw their role as challenging students beyond demands of the HSC. 56

HSC Findings Although wide range of strategies used, key common factor was emphasis on having students think, solve problems and apply knowledge. Understanding built in layers, connections. Frequent assessment and feedback. Teachers saw their role as challenging students beyond demands of the HSC. 56

HSC Findings Assisted note building, ownership of notemaking Group work, community learning more common than might be expected Good relationships and positive classroom climate essential Overall, no instant recipe for teaching success, yet much can be learned from successful teachers and faculties – a framework for reflection and action 57

HSC Findings Assisted note building, ownership of notemaking Group work, community learning more common than might be expected Good relationships and positive classroom climate essential Overall, no instant recipe for teaching success, yet much can be learned from successful teachers and faculties – a framework for reflection and action 57

Key Points Overall, the quality of the teacher and the quality of teaching (large effect sizes) are much more important than structural or working conditions (negligible or small effect sizes), demonstrating the futility and waste of ‘fiddling around the edges’ of schooling without sufficiently addressing the quality of teachers and the quality of teaching within schools and classrooms. 58

Key Points Overall, the quality of the teacher and the quality of teaching (large effect sizes) are much more important than structural or working conditions (negligible or small effect sizes), demonstrating the futility and waste of ‘fiddling around the edges’ of schooling without sufficiently addressing the quality of teachers and the quality of teaching within schools and classrooms. 58

Key Points Quality teaching matters and it’s time we started acting like it. A quality teacher in every classroom is the biggest equity issue in Australian Education today. “It’s no use saying ‘we are doing our best’. You have got to succeed in doing what is necessary”. (Sir Winston Churchill) 59

Key Points Quality teaching matters and it’s time we started acting like it. A quality teacher in every classroom is the biggest equity issue in Australian Education today. “It’s no use saying ‘we are doing our best’. You have got to succeed in doing what is necessary”. (Sir Winston Churchill) 59

60

60

Teaching, like life generally, is heavily dependent on relationships. 62

Teaching, like life generally, is heavily dependent on relationships. 62

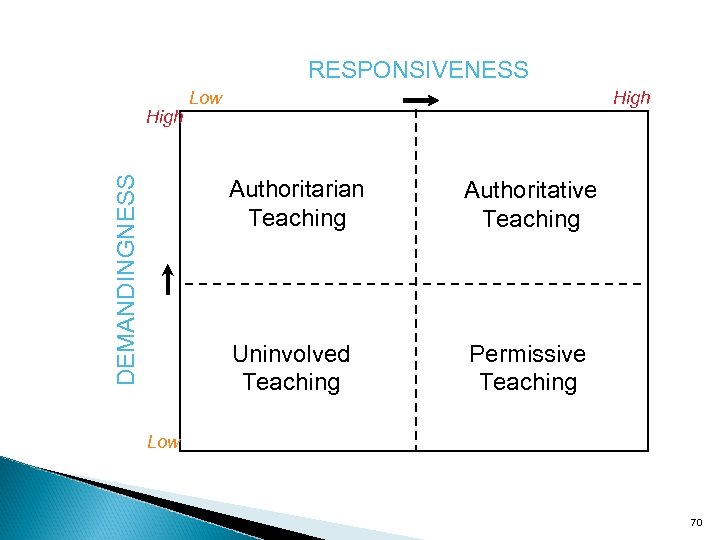

Work of Diana Baumrind on parenting styles Two dimensions underlie parenting style: Responsiveness - ‘the extent to which parents intentionally foster individuality, self-regulation and assertion by being attuned, supportive, and acquiescent to children’s special needs and demands’. Demandingness - ‘the claims parents make on children to become integrated into the family whole, by their maturity demands, supervision, disciplinary efforts and willingness to confront the child who disobeys’. (Baumrind, 1991: 62) 63

Work of Diana Baumrind on parenting styles Two dimensions underlie parenting style: Responsiveness - ‘the extent to which parents intentionally foster individuality, self-regulation and assertion by being attuned, supportive, and acquiescent to children’s special needs and demands’. Demandingness - ‘the claims parents make on children to become integrated into the family whole, by their maturity demands, supervision, disciplinary efforts and willingness to confront the child who disobeys’. (Baumrind, 1991: 62) 63

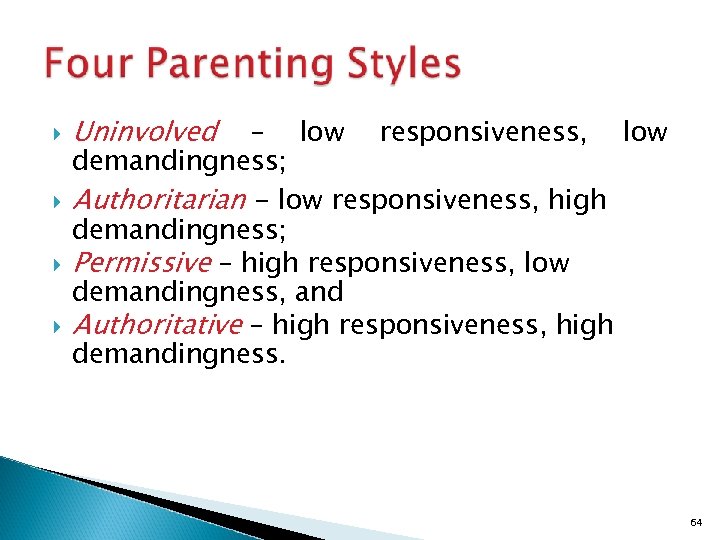

Uninvolved – low responsiveness, low demandingness; Authoritarian - low responsiveness, high demandingness; Permissive – high responsiveness, low demandingness, and Authoritative – high responsiveness, high demandingness. 64

Uninvolved – low responsiveness, low demandingness; Authoritarian - low responsiveness, high demandingness; Permissive – high responsiveness, low demandingness, and Authoritative – high responsiveness, high demandingness. 64

Authoritative Parenting “… authoritative parents are high on both responsiveness and demandingness. They are warm and supportive of their children, aware of their current developmental levels and sensitive to their needs. They also, however, have high expectations, and set appropriate limits while providing structure and consistent rules, the reasons for which they explain to their children, rather than simply expecting unthinking obedience. 65

Authoritative Parenting “… authoritative parents are high on both responsiveness and demandingness. They are warm and supportive of their children, aware of their current developmental levels and sensitive to their needs. They also, however, have high expectations, and set appropriate limits while providing structure and consistent rules, the reasons for which they explain to their children, rather than simply expecting unthinking obedience. 65

Authoritative Parenting While they maintain adult authority they are also willing to listen to their child and to negotiate about rules and situations. This combination of sensitivity, caring, high expectations and structure has been shown to have the best consequences for children, who commonly display academic achievement, good social skills, moral maturity, autonomy and high self esteem. ” (Scott & Dinham, 2005) 66

Authoritative Parenting While they maintain adult authority they are also willing to listen to their child and to negotiate about rules and situations. This combination of sensitivity, caring, high expectations and structure has been shown to have the best consequences for children, who commonly display academic achievement, good social skills, moral maturity, autonomy and high self esteem. ” (Scott & Dinham, 2005) 66

Can the four types of parenting identified by Baumrind be productively applied to teaching? 67

Can the four types of parenting identified by Baumrind be productively applied to teaching? 67

Study of Successful NSW HSC Teaching (Ayres, Dinham & Sawyer) Study of faculties and teams achieving exceptional educational outcomes Years 710 (AESOP project) Study of a primary school where boys outperform girls (Dinham, Buckland, Callingham, Mays) Evaluation of AGQTP Action Learning for NSW DET (Aubusson, Brady & Dinham) 68

Study of Successful NSW HSC Teaching (Ayres, Dinham & Sawyer) Study of faculties and teams achieving exceptional educational outcomes Years 710 (AESOP project) Study of a primary school where boys outperform girls (Dinham, Buckland, Callingham, Mays) Evaluation of AGQTP Action Learning for NSW DET (Aubusson, Brady & Dinham) 68

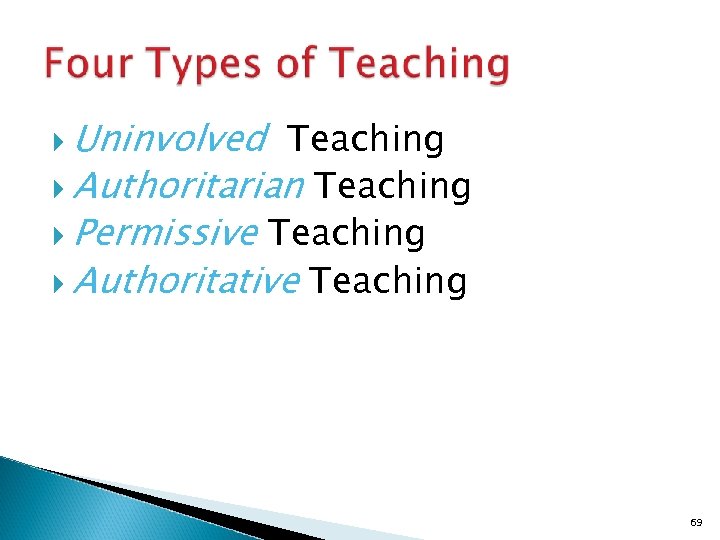

Uninvolved Teaching Authoritarian Teaching Permissive Teaching Authoritative Teaching 69

Uninvolved Teaching Authoritarian Teaching Permissive Teaching Authoritative Teaching 69

RESPONSIVENESS DEMANDINGNESS High Low High Authoritarian Teaching Authoritative Teaching Uninvolved Teaching Permissive Teaching Low 70

RESPONSIVENESS DEMANDINGNESS High Low High Authoritarian Teaching Authoritative Teaching Uninvolved Teaching Permissive Teaching Low 70

What might each type of Teaching look like? Uninvolved Teaching Authoritarian Teaching Permissive Teaching Authoritative Teaching 71

What might each type of Teaching look like? Uninvolved Teaching Authoritarian Teaching Permissive Teaching Authoritative Teaching 71

Enhancing Student Achievement and Self Esteem “We argued that an authoritative teaching style where high responsiveness is accompanied with high demandingness provides the best model for enhancing both student achievement and self esteem, and that a pre-occupation with building student self esteem through a permissive approach in the hope that this will translate into student achievement and development is counter productive. 72

Enhancing Student Achievement and Self Esteem “We argued that an authoritative teaching style where high responsiveness is accompanied with high demandingness provides the best model for enhancing both student achievement and self esteem, and that a pre-occupation with building student self esteem through a permissive approach in the hope that this will translate into student achievement and development is counter productive. 72

Enhancing Student Achievement and Self Esteem We noted recent research where schools that were successful in facilitating students’ academic, personal and social development achieved this through an effective balance of focus on student achievement and student welfare, regardless of whether the school might be perceived by others as being either a ‘welfare’ or ‘academic’ school, an unhelpful and damaging false dichotomy” (Scott & Dinham, 2005; Dinham, 2005). 73

Enhancing Student Achievement and Self Esteem We noted recent research where schools that were successful in facilitating students’ academic, personal and social development achieved this through an effective balance of focus on student achievement and student welfare, regardless of whether the school might be perceived by others as being either a ‘welfare’ or ‘academic’ school, an unhelpful and damaging false dichotomy” (Scott & Dinham, 2005; Dinham, 2005). 73

What Effective Schools Do For Students Overall focus on students as learners and people Expect a lot, give a lot Clear, agreed high standards Everybody knows where he or she stands Flexibility and compassion when needed Recognition: find ways for all students to be successful 74

What Effective Schools Do For Students Overall focus on students as learners and people Expect a lot, give a lot Clear, agreed high standards Everybody knows where he or she stands Flexibility and compassion when needed Recognition: find ways for all students to be successful 74

What Effective Schools Do For Students Create a culture of doing one’s best Centrality of student welfare Focus on “getting students into learning”, not “warm fuzzies”, self-esteem, self concept Students see student welfare has something done for them, not to them Early, appropriate intervention 75

What Effective Schools Do For Students Create a culture of doing one’s best Centrality of student welfare Focus on “getting students into learning”, not “warm fuzzies”, self-esteem, self concept Students see student welfare has something done for them, not to them Early, appropriate intervention 75

Postscript - Education Since the 1960 s In the early 1960 s education generally was characterised by high demandingness and low responsiveness, i. e. , the relationship between schools and students was authoritarian. A wave of social change saw pressure to make schools more responsive to students and their needs. 76

Postscript - Education Since the 1960 s In the early 1960 s education generally was characterised by high demandingness and low responsiveness, i. e. , the relationship between schools and students was authoritarian. A wave of social change saw pressure to make schools more responsive to students and their needs. 76

Postscript - Education Since the 1960 s However, demandingness and responsiveness were falsely dichotomised Greater responsiveness was thought to require less demandingness, and thus the relationship between schools and students became more permissive as demandingness decreased and responsiveness increased. 77

Postscript - Education Since the 1960 s However, demandingness and responsiveness were falsely dichotomised Greater responsiveness was thought to require less demandingness, and thus the relationship between schools and students became more permissive as demandingness decreased and responsiveness increased. 77

Postscript - Education Since the 1960 s This false dichotomy and others (knowledge/skills; subject content/process; academic/welfare; competition/ collaboration; student centred/teacher centred; ‘sage’/ ‘guide’) has resulted in many of the problems we see in schools today, e. g. , ◦ Disengagement, low expectations, behaviourial problems, role conflict and ambiguity, social determinism/stigmatisation, under-achievement, abrogation of teacher responsibility, fear of ‘competition’, learning must be ‘fun’, grade inflation 78

Postscript - Education Since the 1960 s This false dichotomy and others (knowledge/skills; subject content/process; academic/welfare; competition/ collaboration; student centred/teacher centred; ‘sage’/ ‘guide’) has resulted in many of the problems we see in schools today, e. g. , ◦ Disengagement, low expectations, behaviourial problems, role conflict and ambiguity, social determinism/stigmatisation, under-achievement, abrogation of teacher responsibility, fear of ‘competition’, learning must be ‘fun’, grade inflation 78

Postscript - Education Since the 1960 s When such problems occur, there is a tendency to conclude that responsiveness has not gone far enough and is still being hindered by too high demandingness. Thus, problems are further exacerbated 79

Postscript - Education Since the 1960 s When such problems occur, there is a tendency to conclude that responsiveness has not gone far enough and is still being hindered by too high demandingness. Thus, problems are further exacerbated 79

Postscript - Education Since the 1960 s Some who speak out about this situation are seen as traditionalists or part of a ‘back to basics’ movement, i. e. , seeking more authoritarianism. However, the best teachers/leaders and schools today exhibit both high demandingness and high responsiveness, i. e. , the relationship between schools, teachers, leaders and students is authoritative. 80

Postscript - Education Since the 1960 s Some who speak out about this situation are seen as traditionalists or part of a ‘back to basics’ movement, i. e. , seeking more authoritarianism. However, the best teachers/leaders and schools today exhibit both high demandingness and high responsiveness, i. e. , the relationship between schools, teachers, leaders and students is authoritative. 80

Quality teaching matters Leadership is the big enabler Professional Learning is essential The best classrooms, departments, schools, and even systems have a central focus on students as learners and people Educational systems, leaders and teachers need to plan, proceed, assess, evaluate and modify as necessary ON THE BASIS OF EVIDENCE. Data is not just about compliance – it is about improvement Vision is important but it must rest on evidence. 81

Quality teaching matters Leadership is the big enabler Professional Learning is essential The best classrooms, departments, schools, and even systems have a central focus on students as learners and people Educational systems, leaders and teachers need to plan, proceed, assess, evaluate and modify as necessary ON THE BASIS OF EVIDENCE. Data is not just about compliance – it is about improvement Vision is important but it must rest on evidence. 81

82

82

Ayres, P. ; Dinham, S. & Sawyer, W. (1999). Successful Teaching in the NSW Higher School Certificate. Sydney: NSW Department of Education and Training. Ayres, P. ; Dinham, S. & Sawyer, W. (2000). ‘Successful Senior Secondary Teaching’, Quality Teaching Series, No 1, Australian College of Education, September, pp. 1 -20. Ayres, P. ; Dinham, S. & Sawyer, W. (2004). ‘Effective Teaching in the Context of a Grade 12 High Stakes External Examination in New South Wales, Australia’, British Educational Research Journal, 30 (1), pp. 141 -165. Dinham, S. (2009). ‘Teacher Effects – What makes a difference to student achievement? ’, The Spray, 3, NSWIT (in press). Dinham, S. (2008). ‘Feedback on Feedback’, Teacher, May, pp. 20 -23. Dinham, S. (2008). How to get your School Moving and Improving: An evidence-based approach. Melbourne: ACER Press. Dinham, S. (2008). ‘Powerful Teacher Feedback’, Synergy, 6(2), pp. 35 -38. Available at: http: //www. slav. schools. net. au/synergy/vol 6 num 2/dinham. pdf Dinham, S. (2007). Leadership for Exceptional Educational Outcomes. Teneriffe, Qld. : Post Pressed. Hattie, J. (2009). Visible Learning. London: Routledge. Hattie, J. & Timperley, H. (2007). ‘The Power of Feedback’, Review of Educational Research, 77(1), pp. 81112. Marzano, R. ; Pickering, D. & Pollock, J. (2005). Classroom Instruction that Works – Research-based strategies for increasing student achievement. Upper Saddle River, NJ: Pearson. National Research Council. (2000). How People Learn: Brain, Mind, Experience and School. Washington, DC: National Research Council. 83

Ayres, P. ; Dinham, S. & Sawyer, W. (1999). Successful Teaching in the NSW Higher School Certificate. Sydney: NSW Department of Education and Training. Ayres, P. ; Dinham, S. & Sawyer, W. (2000). ‘Successful Senior Secondary Teaching’, Quality Teaching Series, No 1, Australian College of Education, September, pp. 1 -20. Ayres, P. ; Dinham, S. & Sawyer, W. (2004). ‘Effective Teaching in the Context of a Grade 12 High Stakes External Examination in New South Wales, Australia’, British Educational Research Journal, 30 (1), pp. 141 -165. Dinham, S. (2009). ‘Teacher Effects – What makes a difference to student achievement? ’, The Spray, 3, NSWIT (in press). Dinham, S. (2008). ‘Feedback on Feedback’, Teacher, May, pp. 20 -23. Dinham, S. (2008). How to get your School Moving and Improving: An evidence-based approach. Melbourne: ACER Press. Dinham, S. (2008). ‘Powerful Teacher Feedback’, Synergy, 6(2), pp. 35 -38. Available at: http: //www. slav. schools. net. au/synergy/vol 6 num 2/dinham. pdf Dinham, S. (2007). Leadership for Exceptional Educational Outcomes. Teneriffe, Qld. : Post Pressed. Hattie, J. (2009). Visible Learning. London: Routledge. Hattie, J. & Timperley, H. (2007). ‘The Power of Feedback’, Review of Educational Research, 77(1), pp. 81112. Marzano, R. ; Pickering, D. & Pollock, J. (2005). Classroom Instruction that Works – Research-based strategies for increasing student achievement. Upper Saddle River, NJ: Pearson. National Research Council. (2000). How People Learn: Brain, Mind, Experience and School. Washington, DC: National Research Council. 83

Professor Stephen Dinham Research Director – Teaching, Learning and Leadership ACER Private Bag 55 Camberwell Vic 3124 Email: dinham@acer. edu. au Phone: 03 9277 5463 Website: www. acer. edu. au/staffbio/dinham_stephen. html Publications: http: //works. bepress. com/stephen_dinham/ 84

Professor Stephen Dinham Research Director – Teaching, Learning and Leadership ACER Private Bag 55 Camberwell Vic 3124 Email: dinham@acer. edu. au Phone: 03 9277 5463 Website: www. acer. edu. au/staffbio/dinham_stephen. html Publications: http: //works. bepress. com/stephen_dinham/ 84