06fb6a3f26c446bfd07989a7eda1094e.ppt

- Количество слайдов: 72

Problem Solving Exercises: Interpretation of selected blood and urine chemistry data Selected electrolyte disorders and acid-base disturbances; and assessment of renal function E. S. Prakash, MBBS Prakash_es@mercer. edu April 20, 2017 Please do not distribute this presentation. There are some images in this illustration that are copyrighted by third parties. This is for your personal use only.

Selected Teaching (Learning) points as they pertain to interpretation of: Water balance Sodium balance Potassium balance Acid-base disturbances (simple, mixed) Arterial blood gas data Coexistence of and interaction between potassium and acid-base abnormalities. • Renal function (BUN, S Creatinine, Creatinine clearance) • Selected urinalysis indices: p. H; specific gravity vs. osmolality; fractional excretion of sodium • • •

#1 • Arterial blood gas data of a 46 year old patient seen at the emergency with reported to be as follows: Variable p. H Pa. CO 2 (mm Hg) HCO 3 (mmol/L) Value Reference Range 7. 30 60 mm Hg 36 mmol/L 7. 35 - 7. 45 35 -45 mm Hg 22 -26 mmol/L What is your interpretation of this data?

![Normal Arterial Plasma [H+] is 40 nanomoles/L corresponds to a p. H of 7. Normal Arterial Plasma [H+] is 40 nanomoles/L corresponds to a p. H of 7.](https://present5.com/presentation/06fb6a3f26c446bfd07989a7eda1094e/image-4.jpg)

Normal Arterial Plasma [H+] is 40 nanomoles/L corresponds to a p. H of 7. 4 • Henderson-Hasselbalch Eq. • p. H = 6. 1 + log [HCO 3] / [H 2 CO 3] • Modified Henderson Equation or Kassirer Bleich eq. (linear scale): • [H+] = 24 [Pa. CO 2] / [HCO 3], • Where: – [H+] is in nanomoles/L; – Pa. CO 2 is in mm Hg and – [HCO 3] is in mmol/L.

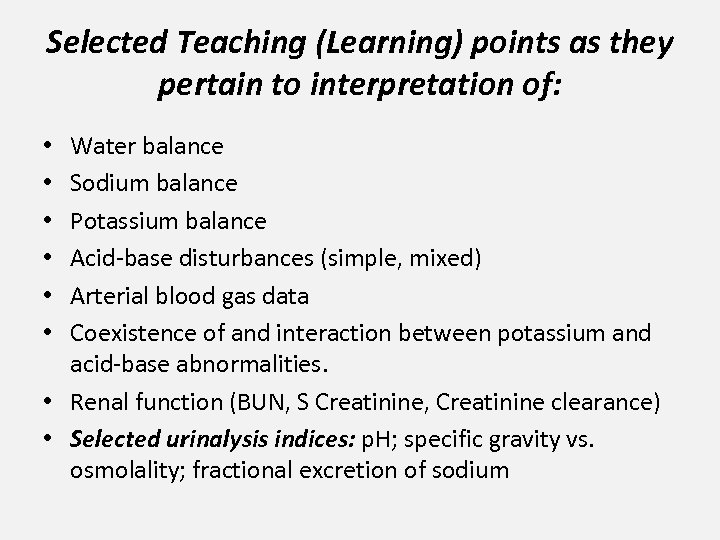

The Linear Scale helps appreciate the magnitude of acid-base disturbances more readily. p. H [H+] in nanomoles/L Condition / Compartment 6. 9 120 ICF (muscle); arterial plasma in life threatening acidosis 7. 0 100 Pure water; severe acidosis 7. 1 80 Inside RBC 7. 33 50 Normal p. H of Cerebrospinal fluid 7. 4 40 Normal average arterial plasma p. H 7. 7 20 Severe alkalosis 8 10 p. H of pancreatic juice

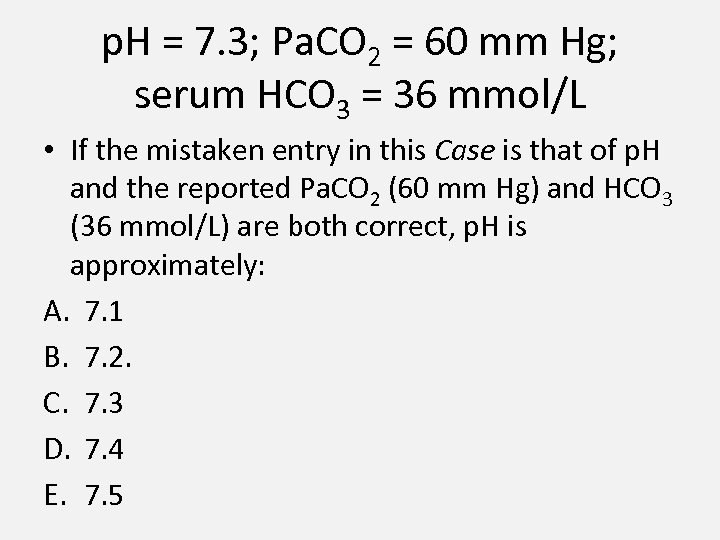

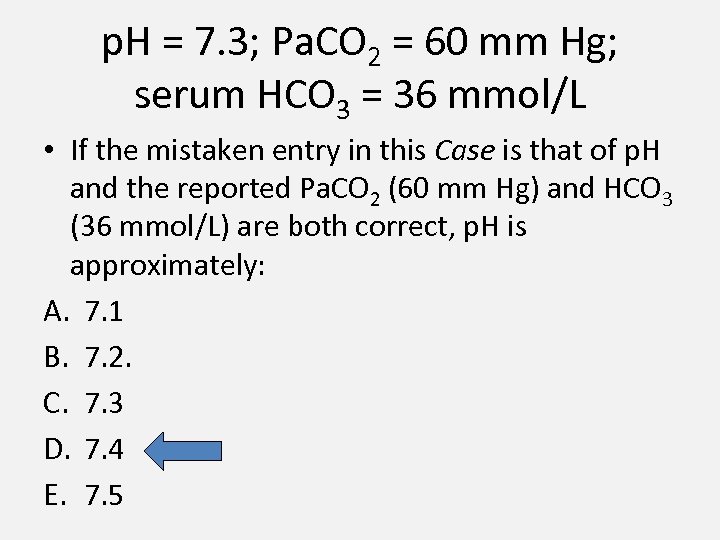

p. H = 7. 3; Pa. CO 2 = 60 mm Hg; serum HCO 3 = 36 mmol/L • If the mistaken entry in this Case is that of p. H and the reported Pa. CO 2 (60 mm Hg) and HCO 3 (36 mmol/L) are both correct, p. H is approximately: A. 7. 1 B. 7. 2. C. 7. 3 D. 7. 4 E. 7. 5

![• Using Henderson’s equation, • [H+] in nanomoles/L = 24 (60) / 36 • Using Henderson’s equation, • [H+] in nanomoles/L = 24 (60) / 36](https://present5.com/presentation/06fb6a3f26c446bfd07989a7eda1094e/image-7.jpg)

• Using Henderson’s equation, • [H+] in nanomoles/L = 24 (60) / 36 = 40 • This corresponds to a p. H of 7. 4.

p. H = 7. 3; Pa. CO 2 = 60 mm Hg; serum HCO 3 = 36 mmol/L • If the mistaken entry in this Case is that of p. H and the reported Pa. CO 2 (60 mm Hg) and HCO 3 (36 mmol/L) are both correct, p. H is approximately: A. 7. 1 B. 7. 2. C. 7. 3 D. 7. 4 E. 7. 5

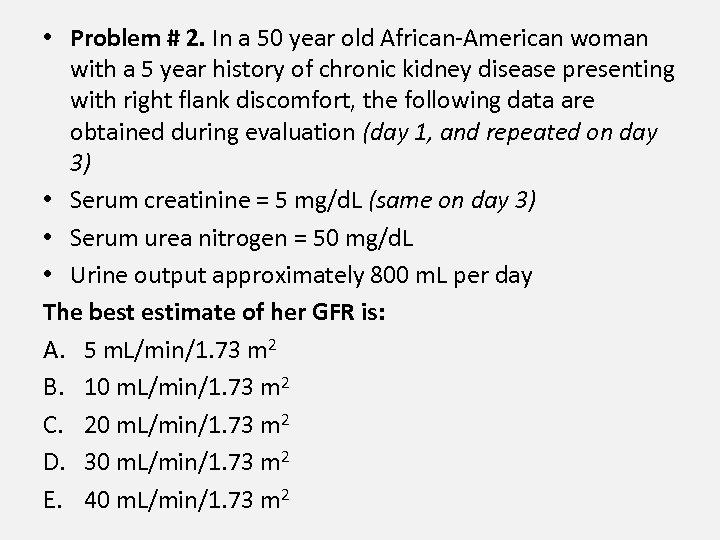

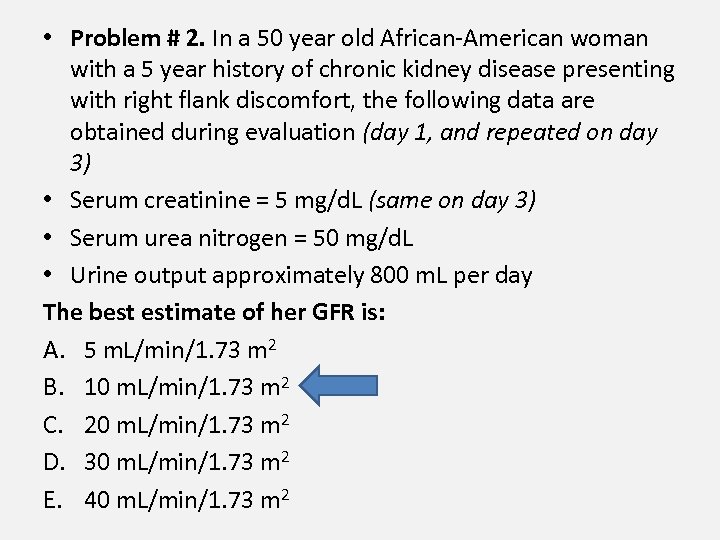

• Problem # 2. In a 50 year old African-American woman with a 5 year history of chronic kidney disease presenting with right flank discomfort, the following data are obtained during evaluation (day 1, and repeated on day 3) • Serum creatinine = 5 mg/d. L (same on day 3) • Serum urea nitrogen = 50 mg/d. L • Urine output approximately 800 m. L per day The best estimate of her GFR is: A. 5 m. L/min/1. 73 m 2 B. 10 m. L/min/1. 73 m 2 C. 20 m. L/min/1. 73 m 2 D. 30 m. L/min/1. 73 m 2 E. 40 m. L/min/1. 73 m 2

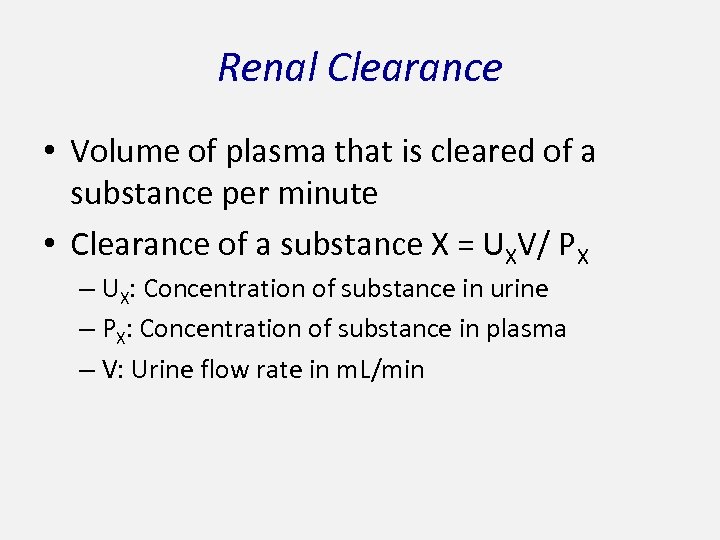

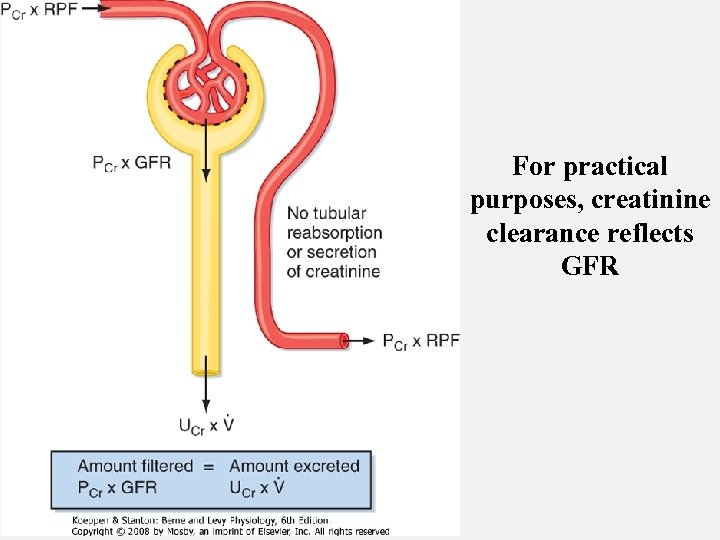

Renal Clearance • Volume of plasma that is cleared of a substance per minute • Clearance of a substance X = UXV/ PX – UX: Concentration of substance in urine – PX: Concentration of substance in plasma – V: Urine flow rate in m. L/min

For practical purposes, creatinine clearance reflects GFR

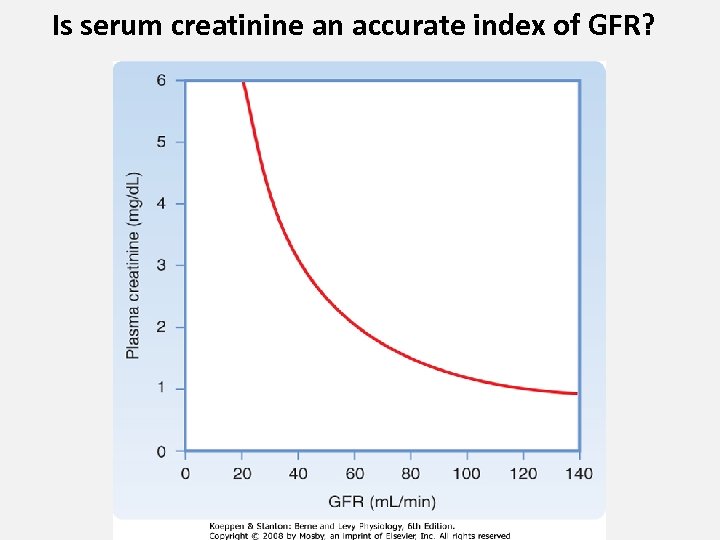

Is serum creatinine an accurate index of GFR?

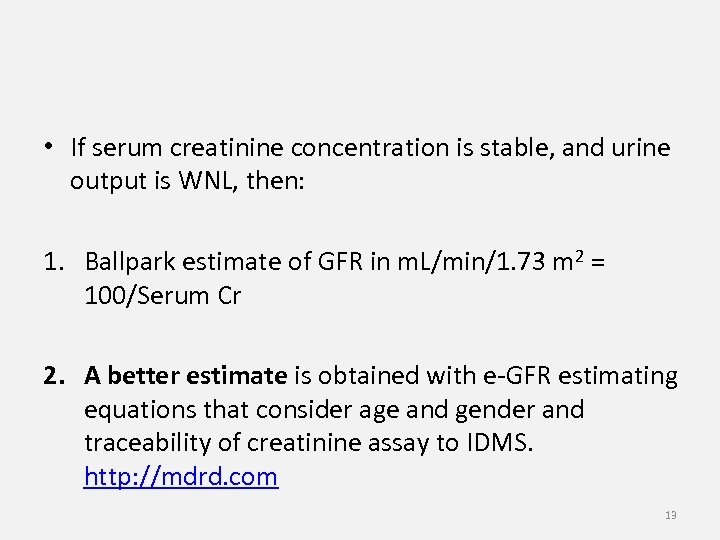

• If serum creatinine concentration is stable, and urine output is WNL, then: 1. Ballpark estimate of GFR in m. L/min/1. 73 m 2 = 100/Serum Cr 2. A better estimate is obtained with e-GFR estimating equations that consider age and gender and traceability of creatinine assay to IDMS. http: //mdrd. com 13

• Problem # 2. In a 50 year old African-American woman with a 5 year history of chronic kidney disease presenting with right flank discomfort, the following data are obtained during evaluation (day 1, and repeated on day 3) • Serum creatinine = 5 mg/d. L (same on day 3) • Serum urea nitrogen = 50 mg/d. L • Urine output approximately 800 m. L per day The best estimate of her GFR is: A. 5 m. L/min/1. 73 m 2 B. 10 m. L/min/1. 73 m 2 C. 20 m. L/min/1. 73 m 2 D. 30 m. L/min/1. 73 m 2 E. 40 m. L/min/1. 73 m 2

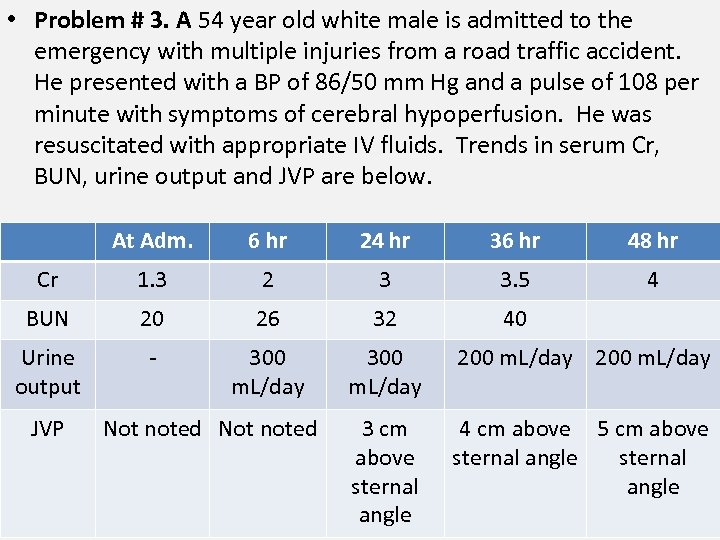

• Problem # 3. A 54 year old white male is admitted to the emergency with multiple injuries from a road traffic accident. He presented with a BP of 86/50 mm Hg and a pulse of 108 per minute with symptoms of cerebral hypoperfusion. He was resuscitated with appropriate IV fluids. Trends in serum Cr, BUN, urine output and JVP are below. At Adm. 6 hr 24 hr 36 hr 48 hr Cr 1. 3 2 3 3. 5 4 BUN 20 26 32 40 Urine output - 300 m. L/day 200 m. L/day 3 cm above sternal angle 4 cm above 5 cm above sternal angle JVP Not noted

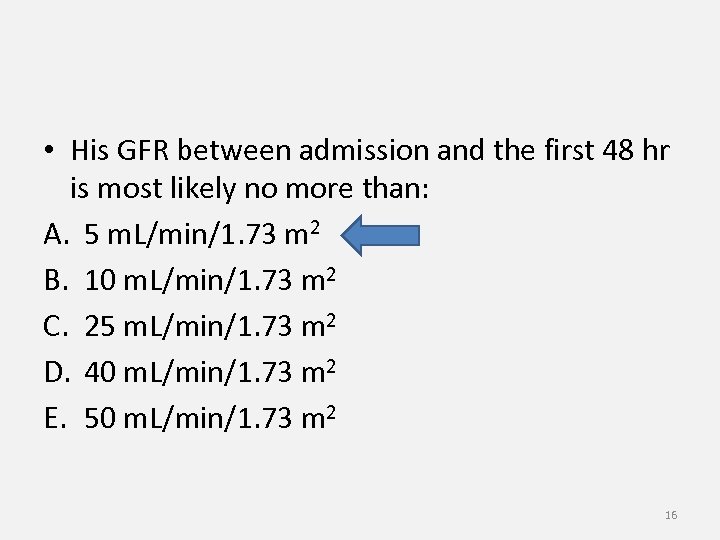

• His GFR between admission and the first 48 hr is most likely no more than: A. 5 m. L/min/1. 73 m 2 B. 10 m. L/min/1. 73 m 2 C. 25 m. L/min/1. 73 m 2 D. 40 m. L/min/1. 73 m 2 E. 50 m. L/min/1. 73 m 2 16

• This patient has a rapidly rising serum creatinine (unstable creatinine) • GFR = Creatinine Clearance = U[Cr] V / P [Cr] • With a 4 fold increase in serum Cr and a six fold decrease in urine output, GFR is likely about 24 fold reduced. • Using a e-GFR estimating equation such as MDRD equation is inappropriate in the context of an unstable serum creatinine. • If GFR is close to zero, the maximum rate at which serum creatinine increases approx. 2 mg/d. L/per day. 17

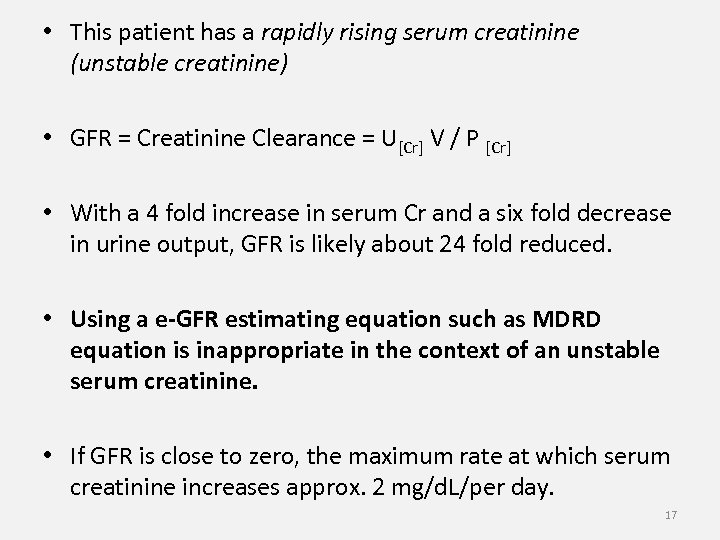

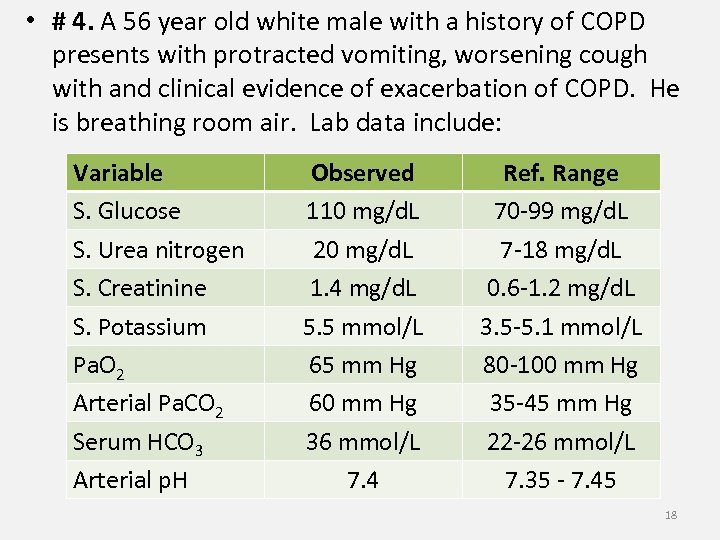

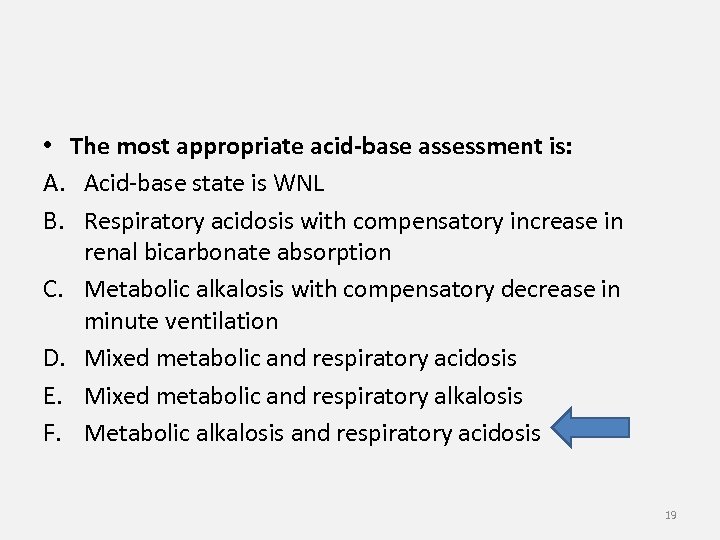

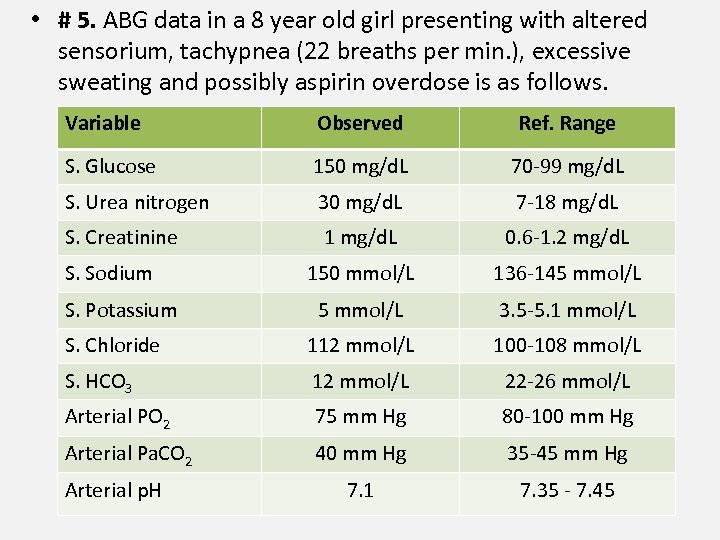

• # 4. A 56 year old white male with a history of COPD presents with protracted vomiting, worsening cough with and clinical evidence of exacerbation of COPD. He is breathing room air. Lab data include: Variable S. Glucose S. Urea nitrogen S. Creatinine S. Potassium Pa. O 2 Arterial Pa. CO 2 Serum HCO 3 Arterial p. H Observed 110 mg/d. L 20 mg/d. L 1. 4 mg/d. L 5. 5 mmol/L 65 mm Hg 60 mm Hg 36 mmol/L 7. 4 Ref. Range 70 -99 mg/d. L 7 -18 mg/d. L 0. 6 -1. 2 mg/d. L 3. 5 -5. 1 mmol/L 80 -100 mm Hg 35 -45 mm Hg 22 -26 mmol/L 7. 35 - 7. 45 18

• The most appropriate acid-base assessment is: A. Acid-base state is WNL B. Respiratory acidosis with compensatory increase in renal bicarbonate absorption C. Metabolic alkalosis with compensatory decrease in minute ventilation D. Mixed metabolic and respiratory acidosis E. Mixed metabolic and respiratory alkalosis F. Metabolic alkalosis and respiratory acidosis 19

# 4 – Teaching Points 1. Compensation for a simple acid-base disturbance does not return p. H to normal; the latter requires correction of the underlying disease process. 2. If a patient has an abnormal PCO 2 and HCO 3 and a p. H that is within the normal range, consider a mixed acid-base disturbance. 20

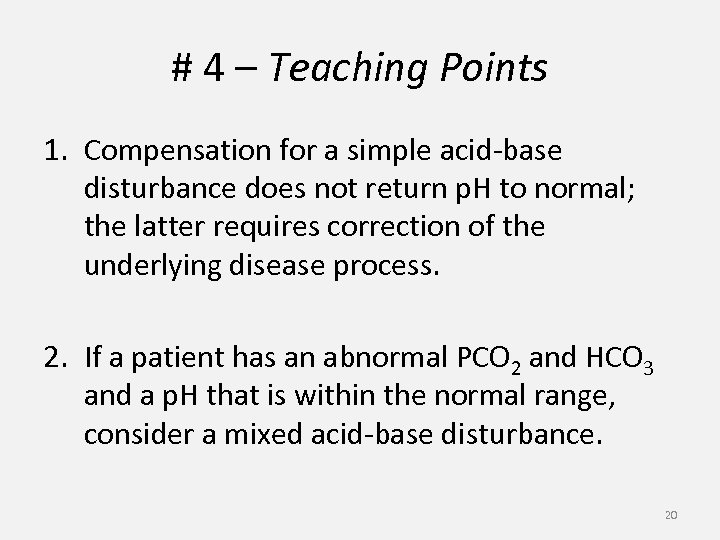

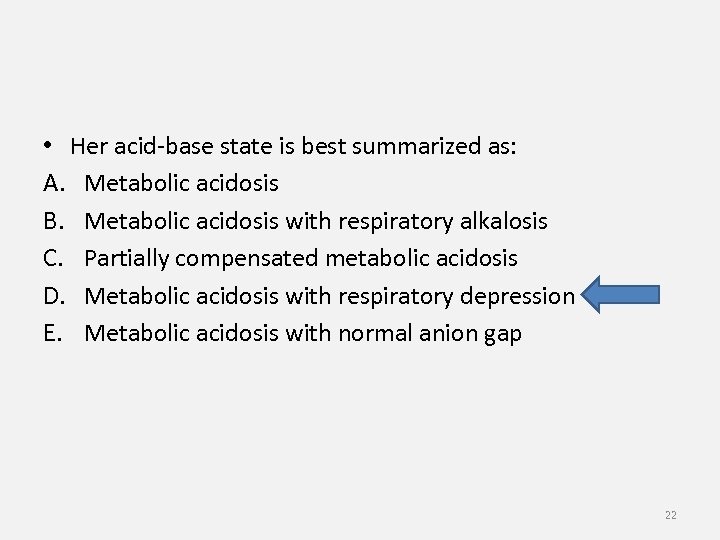

• # 5. ABG data in a 8 year old girl presenting with altered sensorium, tachypnea (22 breaths per min. ), excessive sweating and possibly aspirin overdose is as follows. Variable Observed Ref. Range S. Glucose 150 mg/d. L 70 -99 mg/d. L S. Urea nitrogen 30 mg/d. L 7 -18 mg/d. L S. Creatinine 1 mg/d. L 0. 6 -1. 2 mg/d. L 150 mmol/L 136 -145 mmol/L 3. 5 -5. 1 mmol/L S. Chloride 112 mmol/L 100 -108 mmol/L S. HCO 3 12 mmol/L 22 -26 mmol/L Arterial PO 2 75 mm Hg 80 -100 mm Hg Arterial Pa. CO 2 40 mm Hg 35 -45 mm Hg 7. 1 7. 35 - 7. 45 S. Sodium S. Potassium Arterial p. H

• Her acid-base state is best summarized as: A. Metabolic acidosis B. Metabolic acidosis with respiratory alkalosis C. Partially compensated metabolic acidosis D. Metabolic acidosis with respiratory depression E. Metabolic acidosis with normal anion gap 22

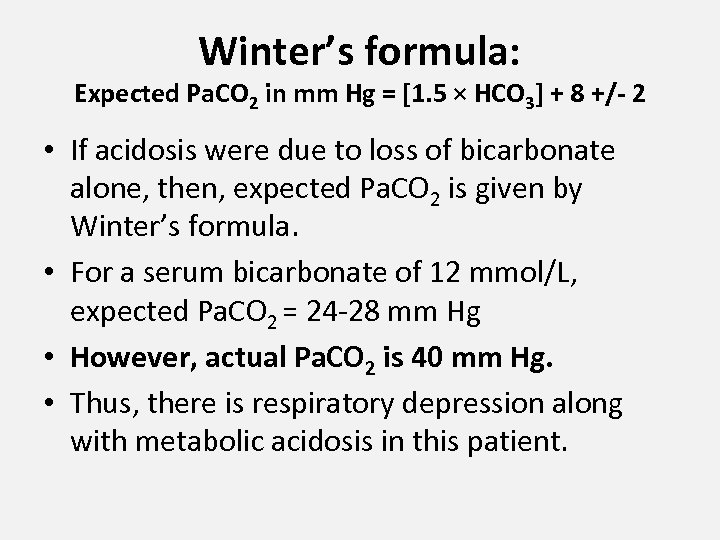

Winter’s formula: Expected Pa. CO 2 in mm Hg = [1. 5 × HCO 3] + 8 +/- 2 • If acidosis were due to loss of bicarbonate alone, then, expected Pa. CO 2 is given by Winter’s formula. • For a serum bicarbonate of 12 mmol/L, expected Pa. CO 2 = 24 -28 mm Hg • However, actual Pa. CO 2 is 40 mm Hg. • Thus, there is respiratory depression along with metabolic acidosis in this patient.

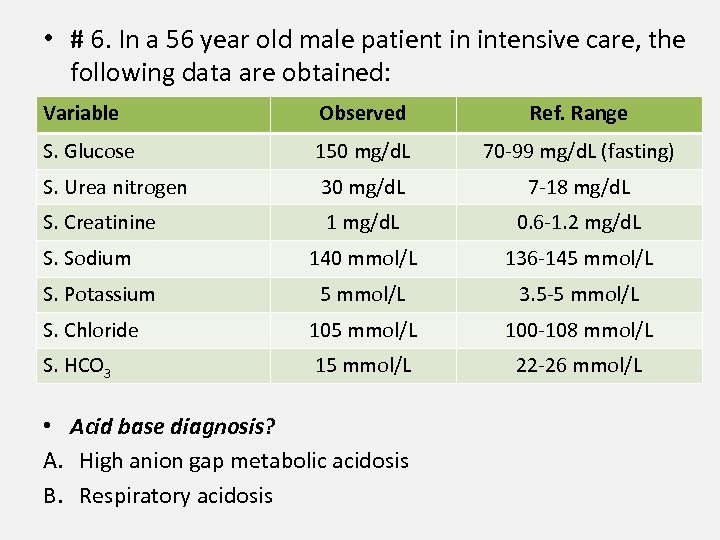

• # 6. In a 56 year old male patient in intensive care, the following data are obtained: Variable Observed Ref. Range S. Glucose 150 mg/d. L 70 -99 mg/d. L (fasting) S. Urea nitrogen 30 mg/d. L 7 -18 mg/d. L S. Creatinine 1 mg/d. L 0. 6 -1. 2 mg/d. L 140 mmol/L 136 -145 mmol/L 3. 5 -5 mmol/L S. Chloride 105 mmol/L 100 -108 mmol/L S. HCO 3 15 mmol/L 22 -26 mmol/L S. Sodium S. Potassium • Acid base diagnosis? A. High anion gap metabolic acidosis B. Respiratory acidosis

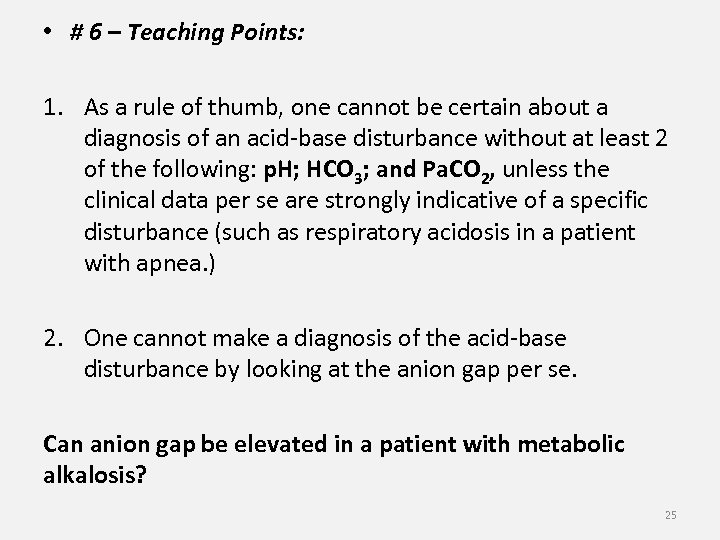

• # 6 – Teaching Points: 1. As a rule of thumb, one cannot be certain about a diagnosis of an acid-base disturbance without at least 2 of the following: p. H; HCO 3; and Pa. CO 2, unless the clinical data per se are strongly indicative of a specific disturbance (such as respiratory acidosis in a patient with apnea. ) 2. One cannot make a diagnosis of the acid-base disturbance by looking at the anion gap per se. Can anion gap be elevated in a patient with metabolic alkalosis? 25

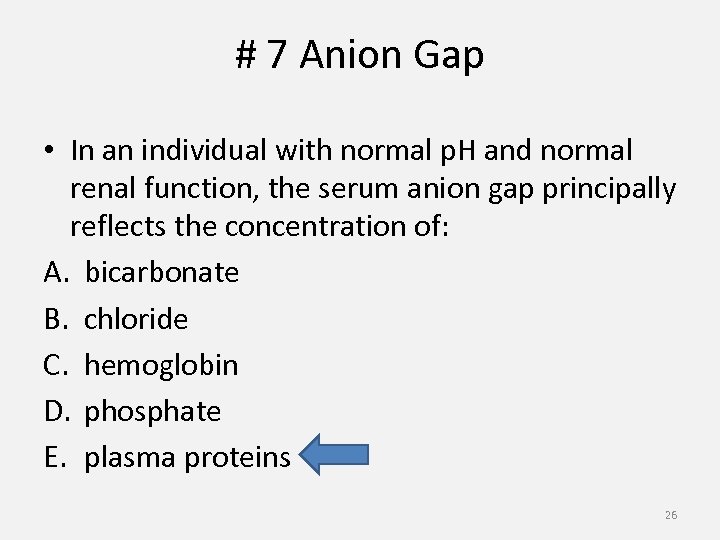

# 7 Anion Gap • In an individual with normal p. H and normal renal function, the serum anion gap principally reflects the concentration of: A. bicarbonate B. chloride C. hemoglobin D. phosphate E. plasma proteins 26

# 7. 1 True or False? • In a patient with high anion gap metabolic acidosis, anion gap is elevated because of a decrease in serum bicarbonate. 27

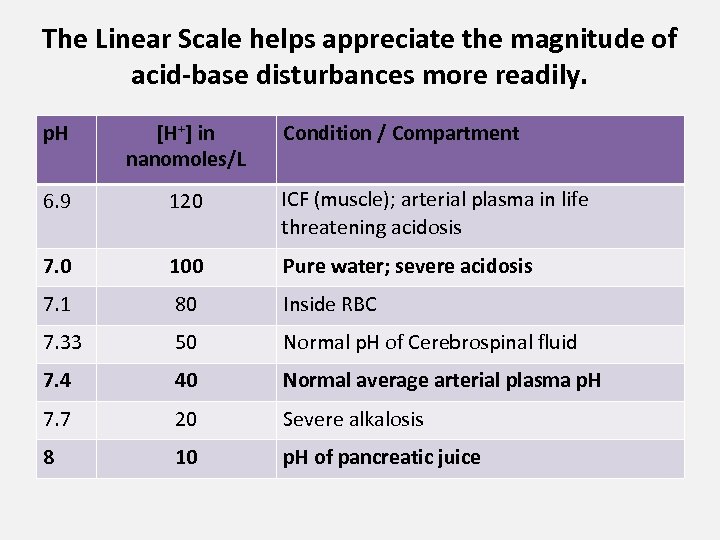

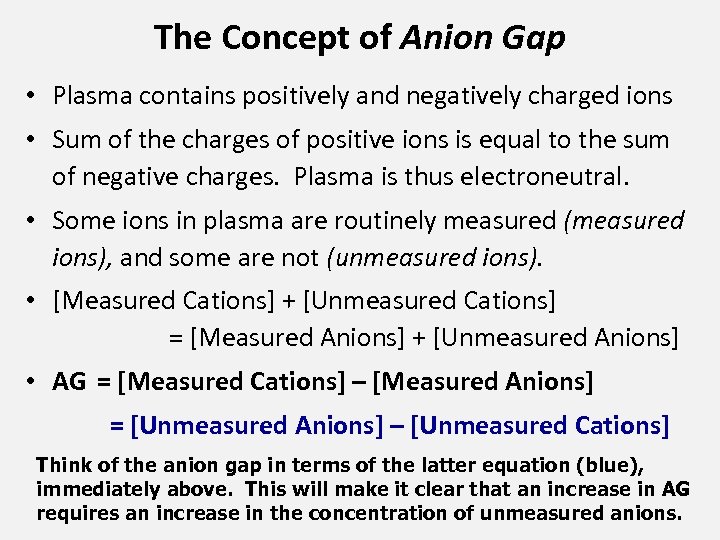

The Concept of Anion Gap • Plasma contains positively and negatively charged ions • Sum of the charges of positive ions is equal to the sum of negative charges. Plasma is thus electroneutral. • Some ions in plasma are routinely measured (measured ions), and some are not (unmeasured ions). • [Measured Cations] + [Unmeasured Cations] = [Measured Anions] + [Unmeasured Anions] • AG = [Measured Cations] – [Measured Anions] = [Unmeasured Anions] – [Unmeasured Cations] Think of the anion gap in terms of the latter equation (blue), immediately above. This will make it clear that an increase in AG requires an increase in the concentration of unmeasured anions.

![{[Na+] + [K+]} – {[Cl-] + [HCO 3]} = [Unmeasured anions] – [Unmeasured cations] {[Na+] + [K+]} – {[Cl-] + [HCO 3]} = [Unmeasured anions] – [Unmeasured cations]](https://present5.com/presentation/06fb6a3f26c446bfd07989a7eda1094e/image-29.jpg)

{[Na+] + [K+]} – {[Cl-] + [HCO 3]} = [Unmeasured anions] – [Unmeasured cations] 1. Ref. range: 8 -16 mmol/L 2. AG is when there is an in the concentration of unmeasured anions, or a in the concentration of unmeasured cations. 3. Practically, the anion gap increases significantly only when there is an increase in the concentration of 1 or more unmeasured anions. 4. AG may be normal or increased in metabolic acidosis; it is used in the differential dx of metabolic acidosis.

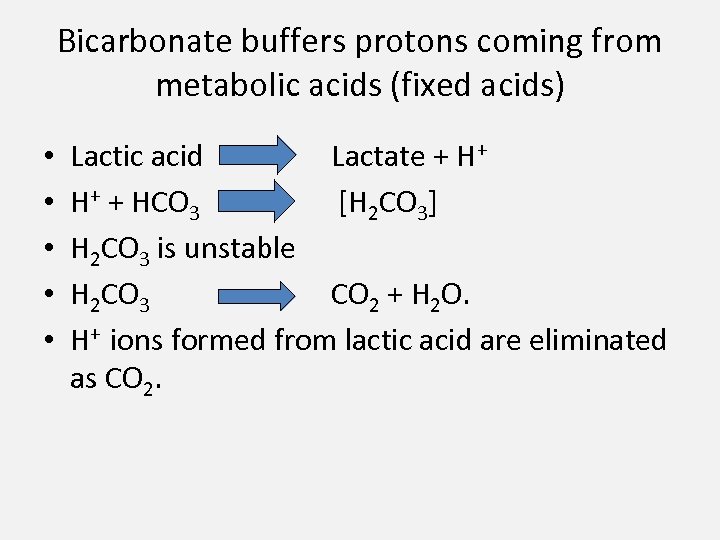

Bicarbonate buffers protons coming from metabolic acids (fixed acids) • • • Lactic acid Lactate + H+ H+ + HCO 3 [H 2 CO 3] H 2 CO 3 is unstable H 2 CO 3 CO 2 + H 2 O. H+ ions formed from lactic acid are eliminated as CO 2.

![Many calculate AG as: {[Na+]} – {[Cl-] + [HCO 3]} • Dropping potassium (although Many calculate AG as: {[Na+]} – {[Cl-] + [HCO 3]} • Dropping potassium (although](https://present5.com/presentation/06fb6a3f26c446bfd07989a7eda1094e/image-31.jpg)

Many calculate AG as: {[Na+]} – {[Cl-] + [HCO 3]} • Dropping potassium (although it is invariably regularly measured). • Upper bound should be lower: 12 mmol/L • However, (per Cecil & Harrison), the ref. range is 8 -16 mmol/L.

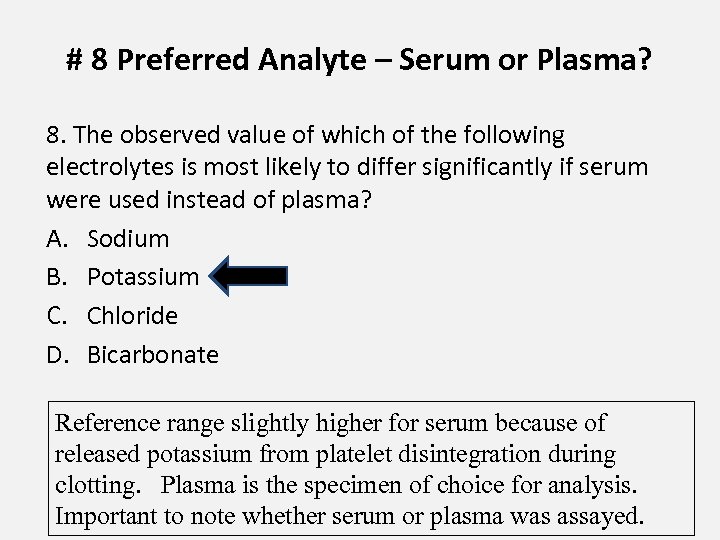

# 8 Preferred Analyte – Serum or Plasma? 8. The observed value of which of the following electrolytes is most likely to differ significantly if serum were used instead of plasma? A. Sodium B. Potassium C. Chloride D. Bicarbonate Reference range slightly higher for serum because of released potassium from platelet disintegration during clotting. Plasma is the specimen of choice for analysis. Important to note whether serum or plasma was assayed.

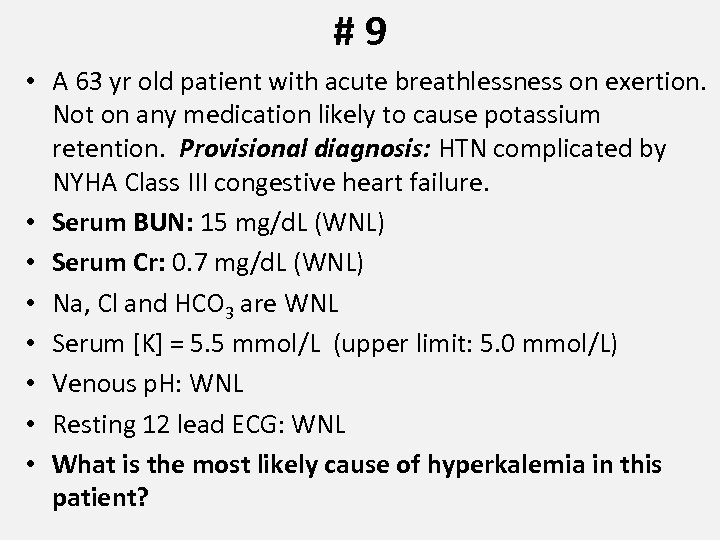

#9 • A 63 yr old patient with acute breathlessness on exertion. Not on any medication likely to cause potassium retention. Provisional diagnosis: HTN complicated by NYHA Class III congestive heart failure. • Serum BUN: 15 mg/d. L (WNL) • Serum Cr: 0. 7 mg/d. L (WNL) • Na, Cl and HCO 3 are WNL • Serum [K] = 5. 5 mmol/L (upper limit: 5. 0 mmol/L) • Venous p. H: WNL • Resting 12 lead ECG: WNL • What is the most likely cause of hyperkalemia in this patient?

![ICF [K] = 140 mmol/L If dietary intake of potassium is relatively constant: Sustained ICF [K] = 140 mmol/L If dietary intake of potassium is relatively constant: Sustained](https://present5.com/presentation/06fb6a3f26c446bfd07989a7eda1094e/image-34.jpg)

ICF [K] = 140 mmol/L If dietary intake of potassium is relatively constant: Sustained hyperkalemia is invariably due to reduced renal excretion of potassium. Transient hyperkalemia may occur from release of K from cells into ECF. Figure from http: //medical-dictionary. thefreedictionary. com/potassium 34

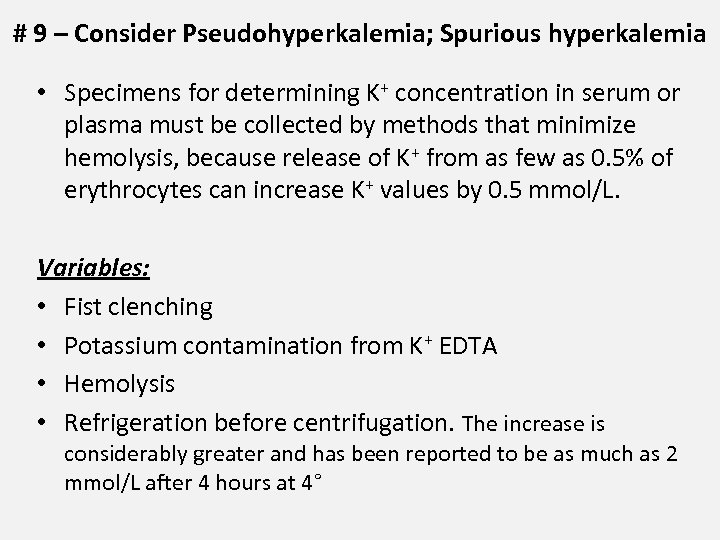

# 9 – Consider Pseudohyperkalemia; Spurious hyperkalemia • Specimens for determining K+ concentration in serum or plasma must be collected by methods that minimize hemolysis, because release of K+ from as few as 0. 5% of erythrocytes can increase K+ values by 0. 5 mmol/L. Variables: • Fist clenching • Potassium contamination from K+ EDTA • Hemolysis • Refrigeration before centrifugation. The increase is considerably greater and has been reported to be as much as 2 mmol/L after 4 hours at 4°

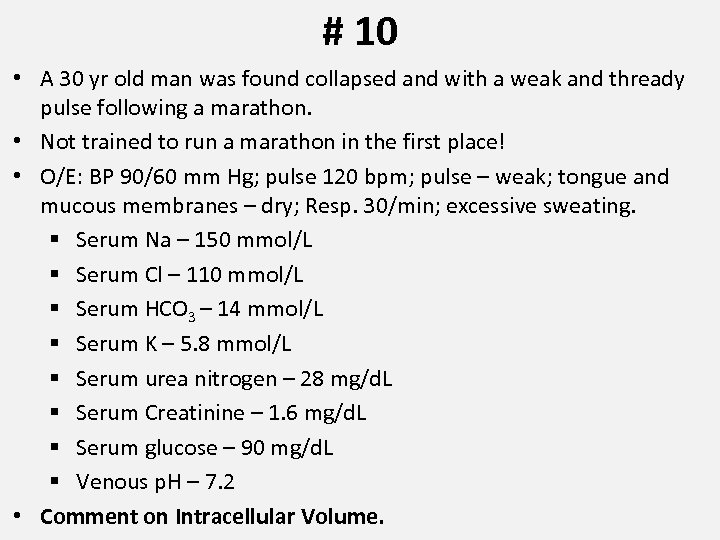

# 10 • A 30 yr old man was found collapsed and with a weak and thready pulse following a marathon. • Not trained to run a marathon in the first place! • O/E: BP 90/60 mm Hg; pulse 120 bpm; pulse – weak; tongue and mucous membranes – dry; Resp. 30/min; excessive sweating. § Serum Na – 150 mmol/L § Serum Cl – 110 mmol/L § Serum HCO 3 – 14 mmol/L § Serum K – 5. 8 mmol/L § Serum urea nitrogen – 28 mg/d. L § Serum Creatinine – 1. 6 mg/d. L § Serum glucose – 90 mg/d. L § Venous p. H – 7. 2 • Comment on Intracellular Volume.

![• Calculated Plasma Osmolality (m. Osm/Kg H 2 O) = 2 [Na+] + • Calculated Plasma Osmolality (m. Osm/Kg H 2 O) = 2 [Na+] +](https://present5.com/presentation/06fb6a3f26c446bfd07989a7eda1094e/image-37.jpg)

• Calculated Plasma Osmolality (m. Osm/Kg H 2 O) = 2 [Na+] + [Glucose] / 18 + [BUN] / 2. 8 (mmol/L) (mg/d. L) • Normal plasma osmolality 285 -295 m. Osm/Kg H 2 O • If serum BUN, glucose and Na are WNL, then osmolality is WNL. • Calculated osmolality correlates well with and reliably predicts measured osmolality of plasma except when there is a significant concentration of one or more unmeasured osmotically active species in plasma. 37

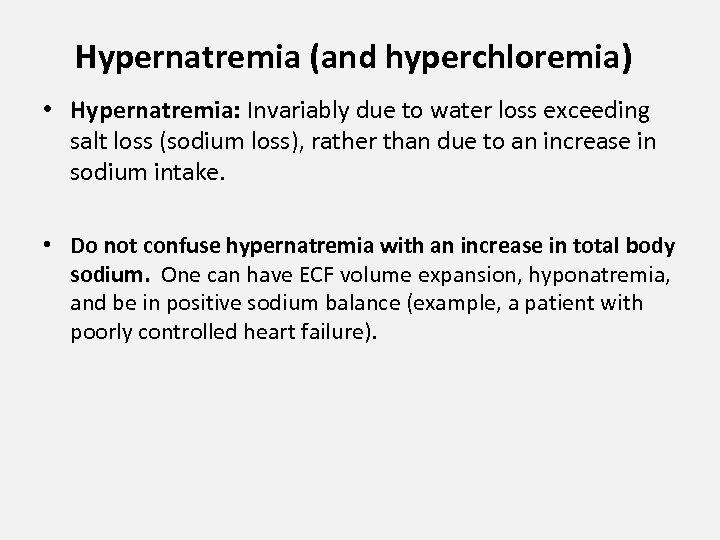

Hypernatremia (and hyperchloremia) • Hypernatremia: Invariably due to water loss exceeding salt loss (sodium loss), rather than due to an increase in sodium intake. • Do not confuse hypernatremia with an increase in total body sodium. One can have ECF volume expansion, hyponatremia, and be in positive sodium balance (example, a patient with poorly controlled heart failure).

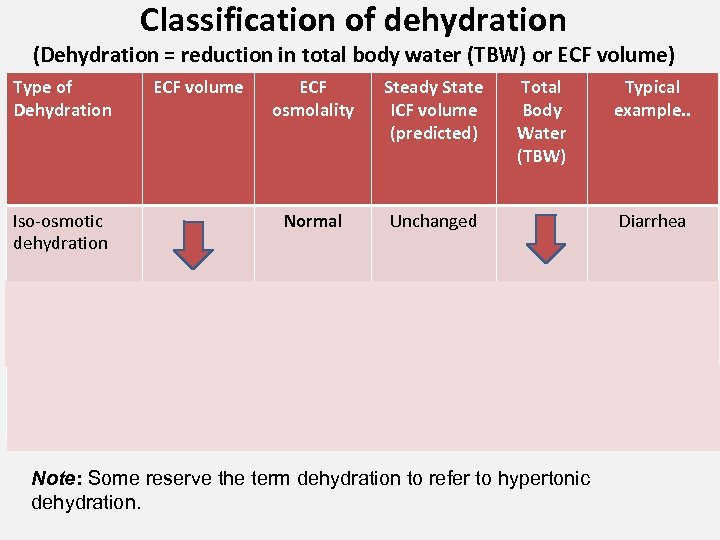

Classification of dehydration (Dehydration = reduction in total body water (TBW) or ECF volume) Type of Dehydration Iso-osmotic dehydration ECF volume ECF osmolality Steady State ICF volume (predicted) Normal Total Body Water (TBW) Unchanged Typical example. . Diarrhea Hyper-osmotic dehydration Diabetic ketoacidosis Hypo-osmotic dehydration Adrenocortical insufficiency Note: Some reserve the term dehydration to refer to hypertonic dehydration.

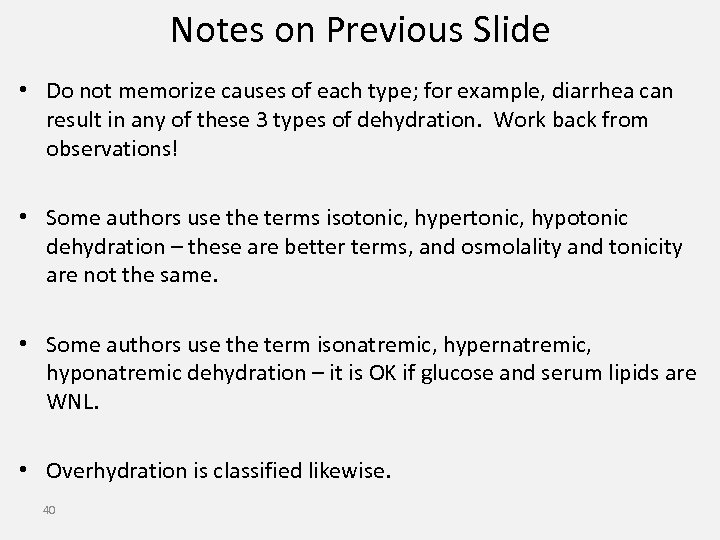

Notes on Previous Slide • Do not memorize causes of each type; for example, diarrhea can result in any of these 3 types of dehydration. Work back from observations! • Some authors use the terms isotonic, hypertonic, hypotonic dehydration – these are better terms, and osmolality and tonicity are not the same. • Some authors use the term isonatremic, hypernatremic, hyponatremic dehydration – it is OK if glucose and serum lipids are WNL. • Overhydration is classified likewise. 40

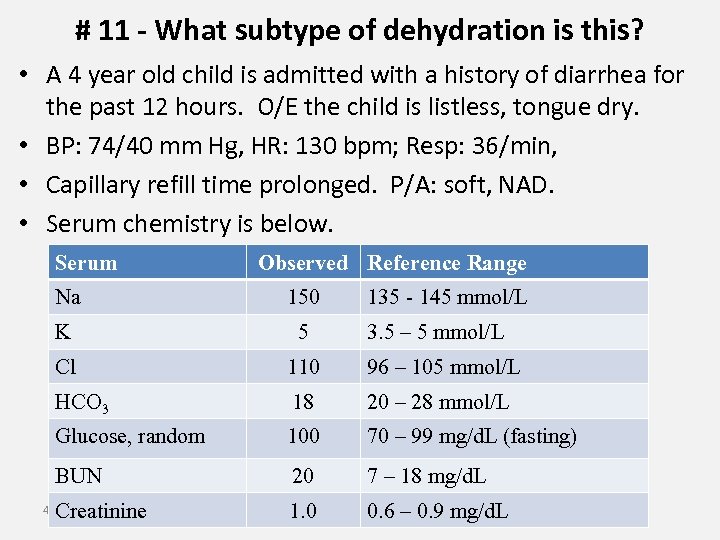

# 11 - What subtype of dehydration is this? • A 4 year old child is admitted with a history of diarrhea for the past 12 hours. O/E the child is listless, tongue dry. • BP: 74/40 mm Hg, HR: 130 bpm; Resp: 36/min, • Capillary refill time prolonged. P/A: soft, NAD. • Serum chemistry is below. Serum Observed Reference Range Na 150 K 5 Cl 110 96 – 105 mmol/L HCO 3 18 20 – 28 mmol/L Glucose, random 100 70 – 99 mg/d. L (fasting) BUN 20 7 – 18 mg/d. L Creatinine 1. 0 0. 6 – 0. 9 mg/d. L 41 135 - 145 mmol/L 3. 5 – 5 mmol/L

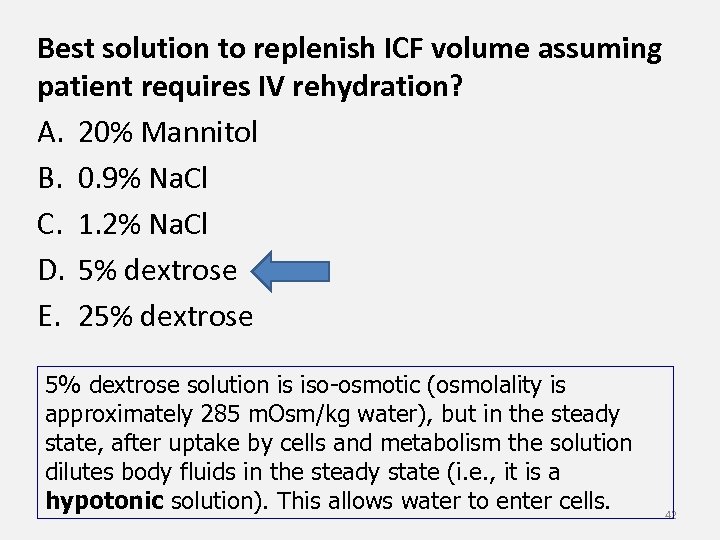

Best solution to replenish ICF volume assuming patient requires IV rehydration? A. 20% Mannitol B. 0. 9% Na. Cl C. 1. 2% Na. Cl D. 5% dextrose E. 25% dextrose solution is iso-osmotic (osmolality is approximately 285 m. Osm/kg water), but in the steady state, after uptake by cells and metabolism the solution dilutes body fluids in the steady state (i. e. , it is a hypotonic solution). This allows water to enter cells. 42

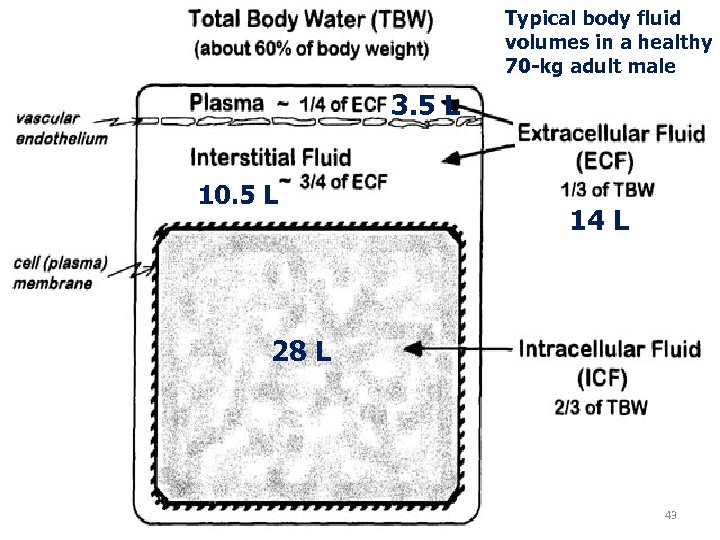

Typical body fluid volumes in a healthy 70 -kg adult male 3. 5 L 10. 5 L 14 L 28 L 43

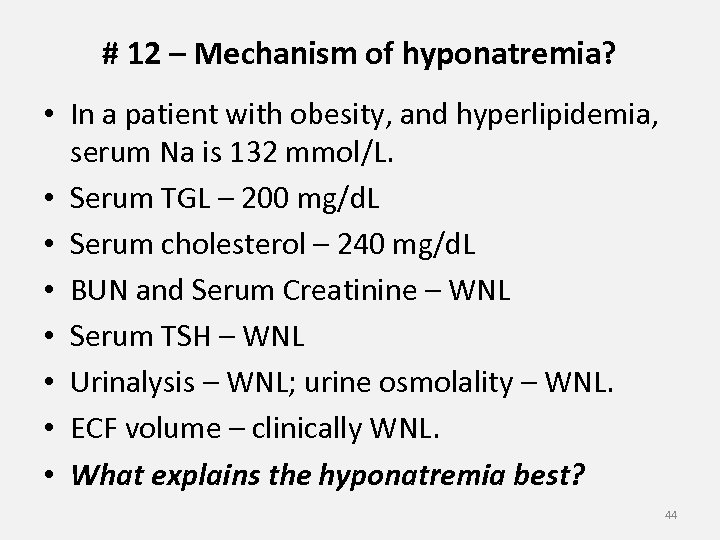

# 12 – Mechanism of hyponatremia? • In a patient with obesity, and hyperlipidemia, serum Na is 132 mmol/L. • Serum TGL – 200 mg/d. L • Serum cholesterol – 240 mg/d. L • BUN and Serum Creatinine – WNL • Serum TSH – WNL • Urinalysis – WNL; urine osmolality – WNL. • ECF volume – clinically WNL. • What explains the hyponatremia best? 44

Is this really hyponatremia? • Pseudohyponatremia: 1. Na dissolves only in the water phase of plasma or serum. Thus, when a greater than normal proportion of plasma is accounted for by lipids or proteins, the concentration of Na in the aqueous phase remains normal but it may be lower in a serum sample or plasma sample. 2. Most common cause of pseudohyponatremia is hyperlipidemia. 3. The problem can be bypassed by using ion-selective electrodes for measurement of sodium concentration which measures sodium concentration in the aqueous phase of plasma rather than whole plasma.

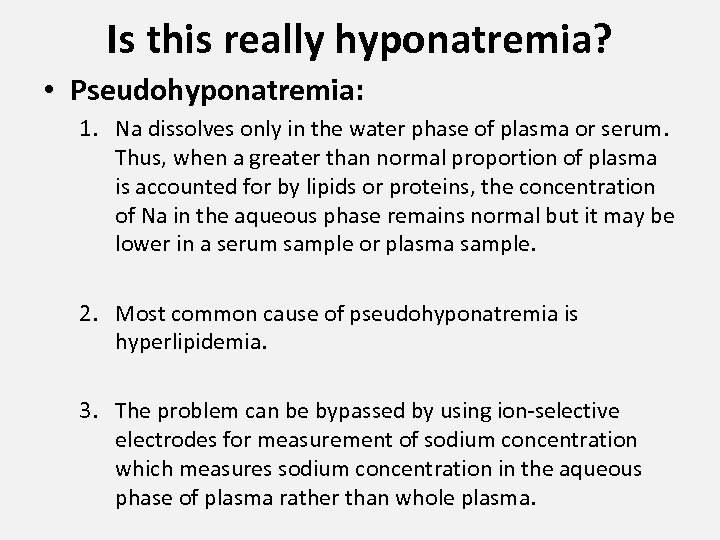

# 13 – Mechanism of hyponatremia? • James Williams, a 46 year old African-American male, presents with an episode of hematemesis. Longstanding h/o excessive alcohol intake. Clinical findings suggestive of cirrhosis with portal HTN. • O/E – tense ascites; pedal edema +++ • Serum chemistry: § § § Na – 130 mmol/L K – 4 mmol/L Cl – 100 mmol/L HCO 3 – 26 mmol/L Glucose – WNL Creatinine – 1. 5 mg/d. L (elevated) 46

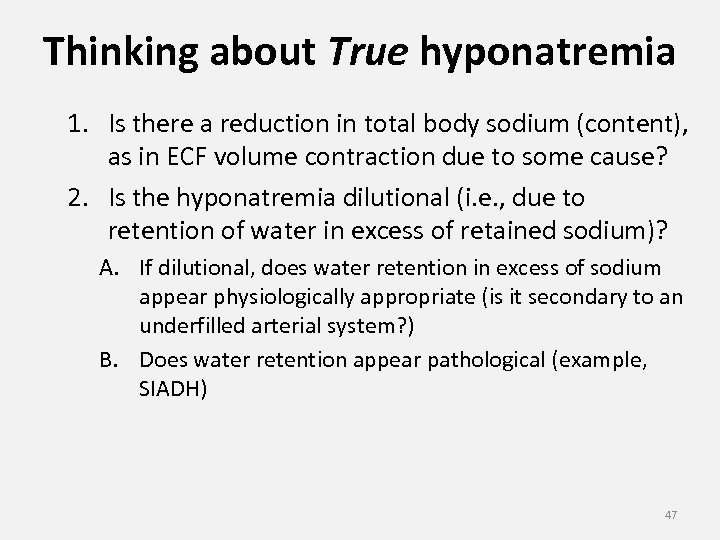

Thinking about True hyponatremia 1. Is there a reduction in total body sodium (content), as in ECF volume contraction due to some cause? 2. Is the hyponatremia dilutional (i. e. , due to retention of water in excess of retained sodium)? A. If dilutional, does water retention in excess of sodium appear physiologically appropriate (is it secondary to an underfilled arterial system? ) B. Does water retention appear pathological (example, SIADH) 47

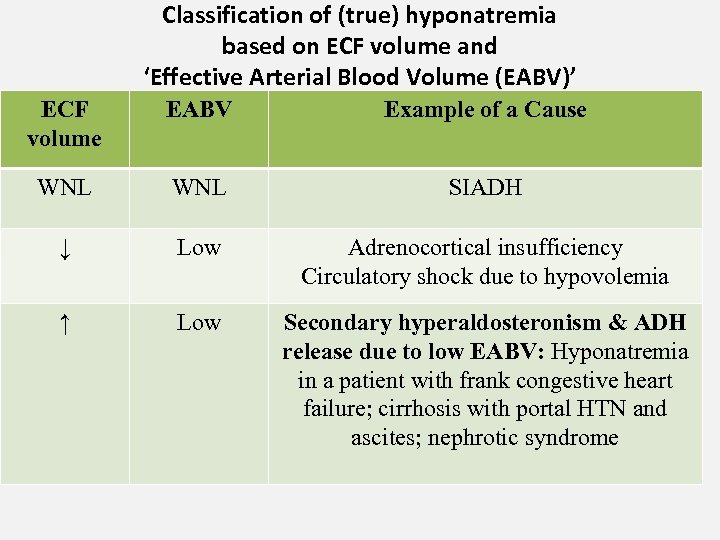

Classification of (true) hyponatremia based on ECF volume and ‘Effective Arterial Blood Volume (EABV)’ ECF volume EABV Example of a Cause WNL SIADH ↓ Low Adrenocortical insufficiency Circulatory shock due to hypovolemia ↑ Low Secondary hyperaldosteronism & ADH release due to low EABV: Hyponatremia in a patient with frank congestive heart failure; cirrhosis with portal HTN and ascites; nephrotic syndrome

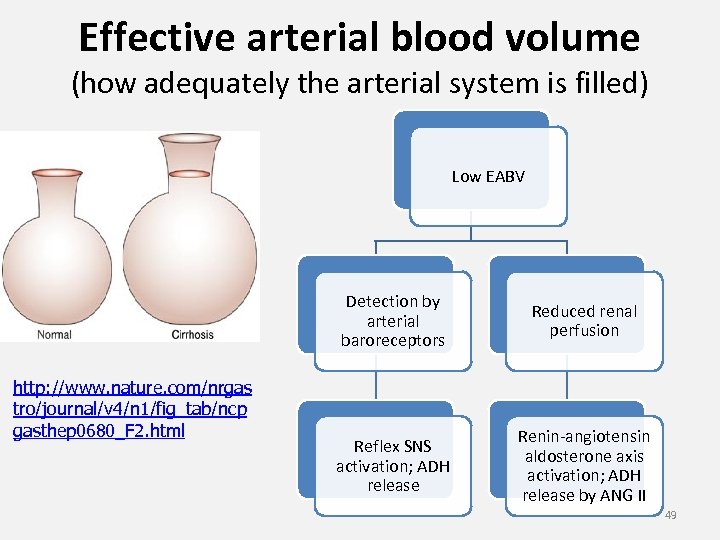

Effective arterial blood volume (how adequately the arterial system is filled) Low EABV Detection by arterial baroreceptors http: //www. nature. com/nrgas tro/journal/v 4/n 1/fig_tab/ncp gasthep 0680_F 2. html Reduced renal perfusion Reflex SNS activation; ADH release Renin-angiotensin aldosterone axis activation; ADH release by ANG II 49

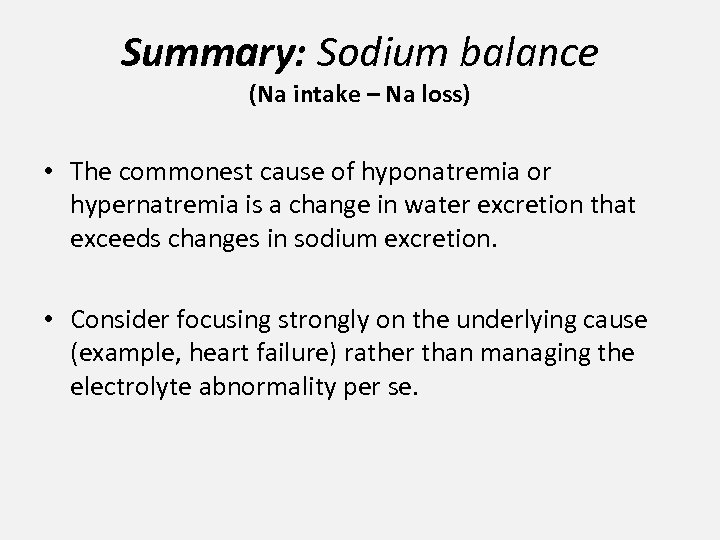

Summary: Sodium balance (Na intake – Na loss) • The commonest cause of hyponatremia or hypernatremia is a change in water excretion that exceeds changes in sodium excretion. • Consider focusing strongly on the underlying cause (example, heart failure) rather than managing the electrolyte abnormality per se.

• Problem # 14: 40 year old man with uncontrolled HTN, serum K of 3 mmol/L, serum HCO 3 of 30 mmol/L, and venous p. H of 7. 48. Serum aldosterone was elevated. Plasma renin activity suppressed. – Cause of hypokalemia? – Metabolic alkalosis? • Primary hyperaldosteronism (a common cause) underlies hypokalemia as well as metabolic alkalosis

Coexistence of (or Interaction between) Potassium and acid-base abnormalities • Hyperkalemia and metabolic acidosis • Hypokalemia and metabolic alkalosis • Hypokalemia and metabolic acidosis – All combinations described. – If observations are reliable, account for them!

Problem # 15: Mechanism of hypokalemia in states in which there is ECF volume contraction • A 54 year old male with gastric outlet obstruction and recurrent vomiting. Has clinical evidence suggestive of ECF volume contraction. • Venous p. H: 7. 5. • Serum [K]: 2. 8 mmol/L • Explain why K is low and why p. H is raised? • Hypokalemia and alkalosis from vomiting. • What likely happens to renal K excretion in this case?

• Angiotensin stimulates aldosterone release and aldosterone facilitates Na, Cl and water reabsorption, increases renal K secretion and may exacerbate hypokalemia. • However, if the patient is hypokalemic for any reason (example, vomiting), hypokalemia inhibits aldosterone secretion. • That is, serum K affected by multiple variables.

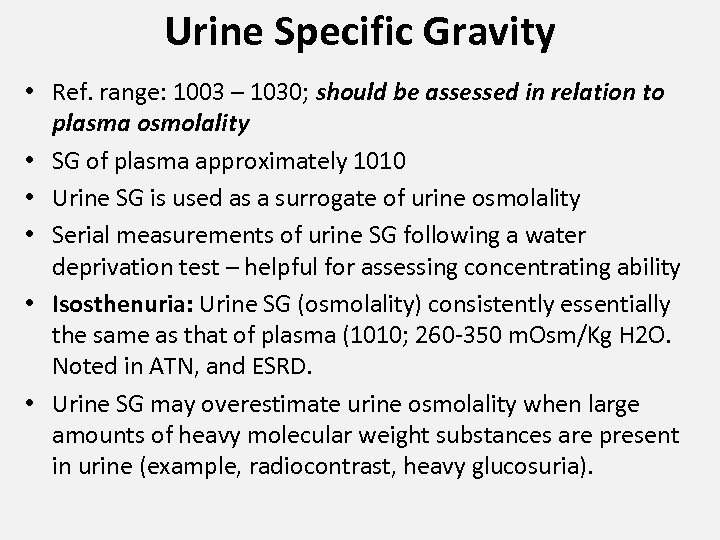

• Problem # 16: A 30 year old male with a H/O HTN (8 yr) was found to have a urine SG of 1010 (reference range 1003 – 1030). • BUN – 80 mg/d. L • Serum Cr - 4 mg/d. L • Serum [K] - 5. 8 mmol/L • Venous p. H - 7. 28 • Comment on urine concentrating ability.

• 16 A. Water deprivation for 7 hr fails to produce an increase in urine osmolality in: A. neurogenic diabetes insipidus B. nephrogenic diabetes insipidus

Urine Specific Gravity • Ref. range: 1003 – 1030; should be assessed in relation to plasma osmolality • SG of plasma approximately 1010 • Urine SG is used as a surrogate of urine osmolality • Serial measurements of urine SG following a water deprivation test – helpful for assessing concentrating ability • Isosthenuria: Urine SG (osmolality) consistently essentially the same as that of plasma (1010; 260 -350 m. Osm/Kg H 2 O. Noted in ATN, and ESRD. • Urine SG may overestimate urine osmolality when large amounts of heavy molecular weight substances are present in urine (example, radiocontrast, heavy glucosuria).

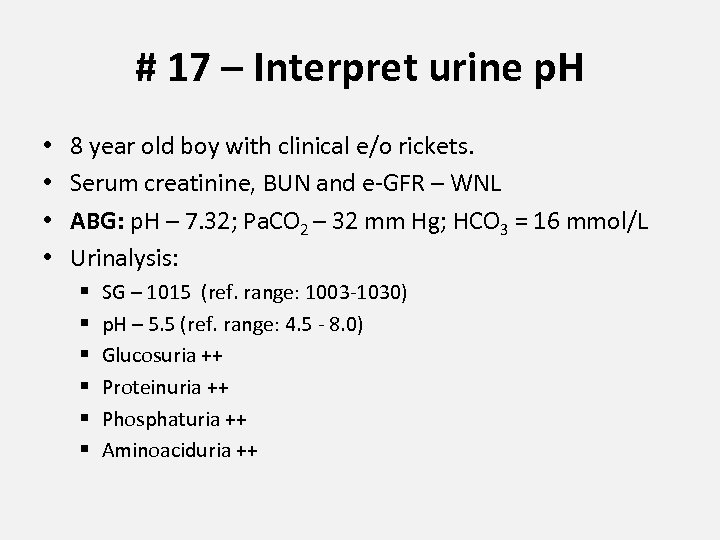

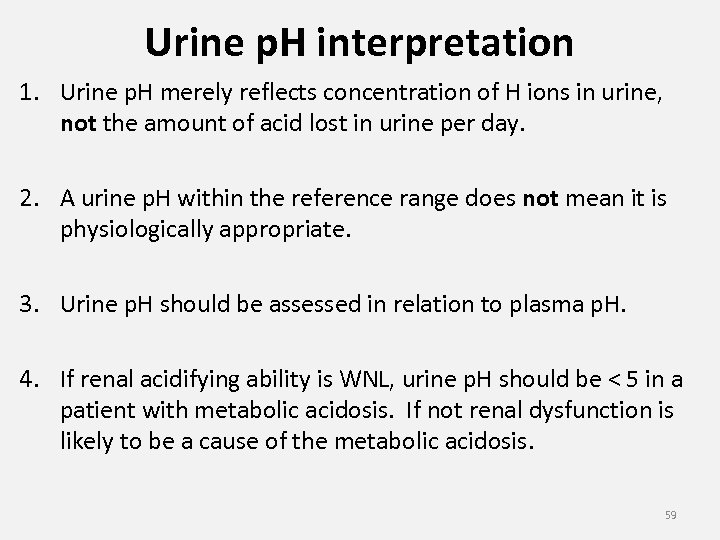

# 17 – Interpret urine p. H • • 8 year old boy with clinical e/o rickets. Serum creatinine, BUN and e-GFR – WNL ABG: p. H – 7. 32; Pa. CO 2 – 32 mm Hg; HCO 3 = 16 mmol/L Urinalysis: § § § SG – 1015 (ref. range: 1003 -1030) p. H – 5. 5 (ref. range: 4. 5 - 8. 0) Glucosuria ++ Proteinuria ++ Phosphaturia ++ Aminoaciduria ++

Urine p. H interpretation 1. Urine p. H merely reflects concentration of H ions in urine, not the amount of acid lost in urine per day. 2. A urine p. H within the reference range does not mean it is physiologically appropriate. 3. Urine p. H should be assessed in relation to plasma p. H. 4. If renal acidifying ability is WNL, urine p. H should be < 5 in a patient with metabolic acidosis. If not renal dysfunction is likely to be a cause of the metabolic acidosis. 59

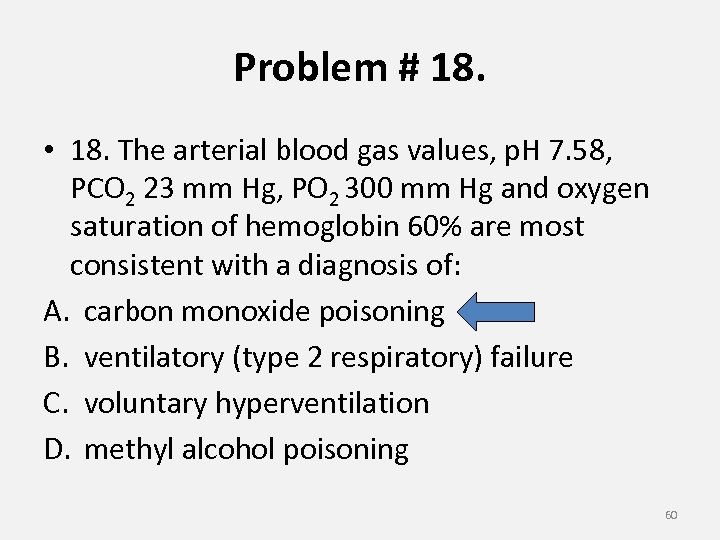

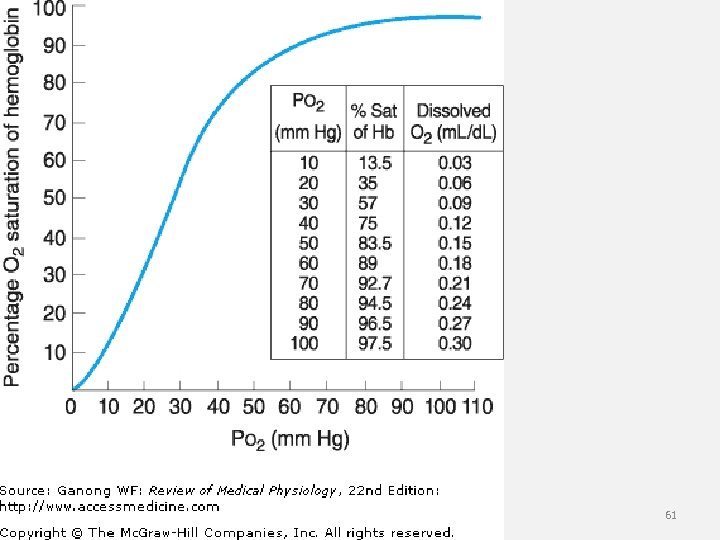

Problem # 18. • 18. The arterial blood gas values, p. H 7. 58, PCO 2 23 mm Hg, PO 2 300 mm Hg and oxygen saturation of hemoglobin 60% are most consistent with a diagnosis of: A. carbon monoxide poisoning B. ventilatory (type 2 respiratory) failure C. voluntary hyperventilation D. methyl alcohol poisoning 60

61

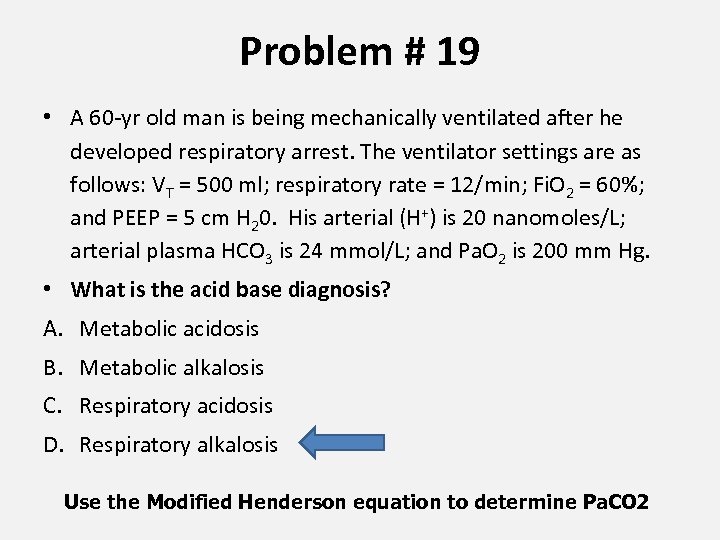

Problem # 19 • A 60 -yr old man is being mechanically ventilated after he developed respiratory arrest. The ventilator settings are as follows: VT = 500 ml; respiratory rate = 12/min; Fi. O 2 = 60%; and PEEP = 5 cm H 20. His arterial (H+) is 20 nanomoles/L; arterial plasma HCO 3 is 24 mmol/L; and Pa. O 2 is 200 mm Hg. • What is the acid base diagnosis? A. Metabolic acidosis B. Metabolic alkalosis C. Respiratory acidosis D. Respiratory alkalosis Use the Modified Henderson equation to determine Pa. CO 2

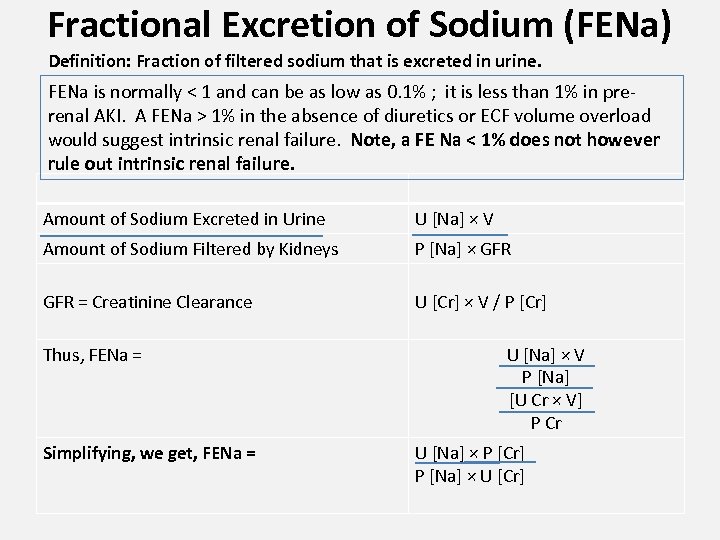

Fractional Excretion of Sodium (FENa) Definition: Fraction of filtered sodium that is excreted in urine. FENa is normally < 1 and can be as low as 0. 1% ; it is less than 1% in prerenal AKI. A FENa > 1% in the absence of diuretics or ECF volume overload would suggest intrinsic renal failure. Note, a FE Na < 1% does not however rule out intrinsic renal failure. Amount of Sodium Excreted in Urine U [Na] × V Amount of Sodium Filtered by Kidneys P [Na] × GFR = Creatinine Clearance U [Cr] × V / P [Cr] Thus, FENa = Simplifying, we get, FENa = U [Na] × V P [Na] [U Cr × V] P Cr U [Na] × P [Cr] P [Na] × U [Cr]

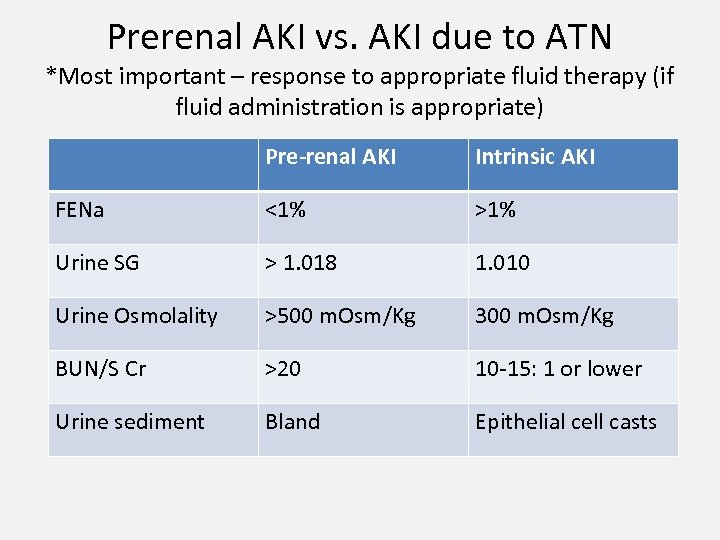

Prerenal AKI vs. AKI due to ATN *Most important – response to appropriate fluid therapy (if fluid administration is appropriate) Pre-renal AKI Intrinsic AKI FENa <1% >1% Urine SG > 1. 018 1. 010 Urine Osmolality >500 m. Osm/Kg 300 m. Osm/Kg BUN/S Cr >20 10 -15: 1 or lower Urine sediment Bland Epithelial cell casts

Gastrointestinal & Hepatobilary

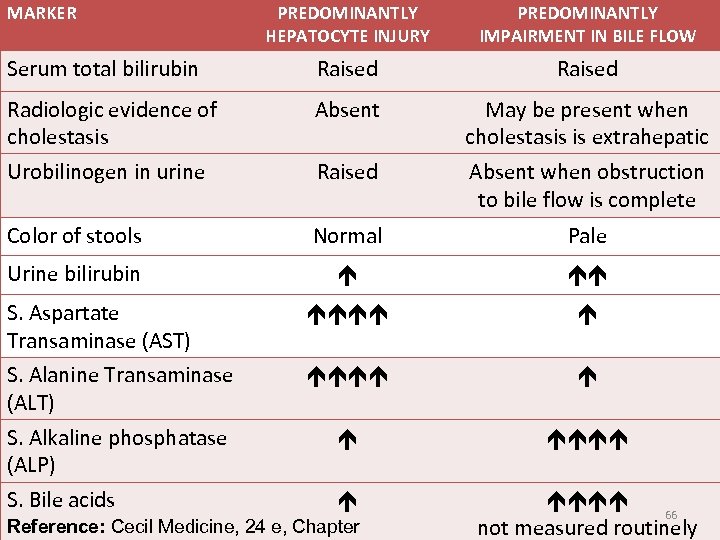

MARKER PREDOMINANTLY HEPATOCYTE INJURY PREDOMINANTLY IMPAIRMENT IN BILE FLOW Serum total bilirubin Raised Radiologic evidence of cholestasis Absent May be present when cholestasis is extrahepatic Urobilinogen in urine Raised Absent when obstruction to bile flow is complete Color of stools Normal Pale Urine bilirubin S. Aspartate Transaminase (AST) S. Alanine Transaminase (ALT) S. Alkaline phosphatase (ALP) S. Bile acids 66 not measured routinely Reference: Cecil Medicine, 24 e, Chapter

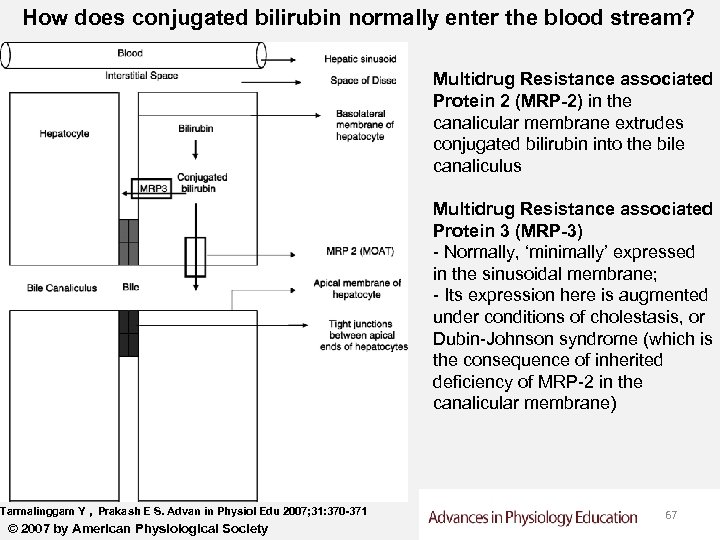

How does conjugated bilirubin normally enter the blood stream? Multidrug Resistance associated Protein 2 (MRP-2) in the canalicular membrane extrudes conjugated bilirubin into the bile canaliculus Multidrug Resistance associated Protein 3 (MRP-3) - Normally, ‘minimally’ expressed in the sinusoidal membrane; - Its expression here is augmented under conditions of cholestasis, or Dubin-Johnson syndrome (which is the consequence of inherited deficiency of MRP-2 in the canalicular membrane) Tarmalinggam Y , Prakash E S. Advan in Physiol Edu 2007; 31: 370 -371 © 2007 by American Physiological Society 67

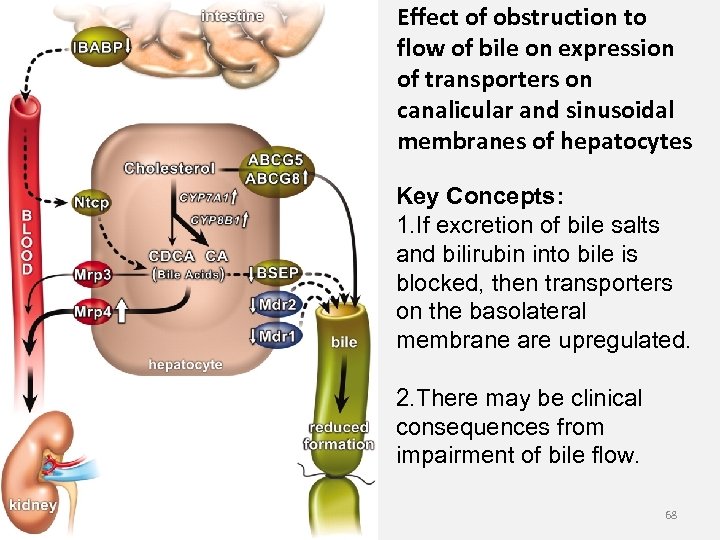

Effect of obstruction to flow of bile on expression of transporters on canalicular and sinusoidal membranes of hepatocytes Key Concepts: 1. If excretion of bile salts and bilirubin into bile is blocked, then transporters on the basolateral membrane are upregulated. 2. There may be clinical consequences from impairment of bile flow. 68

http: //web. squ. edu. om/med. Lib/MED_CD/E_CDs/anesthesia/site/content/figures/2017 F 02. gif 69

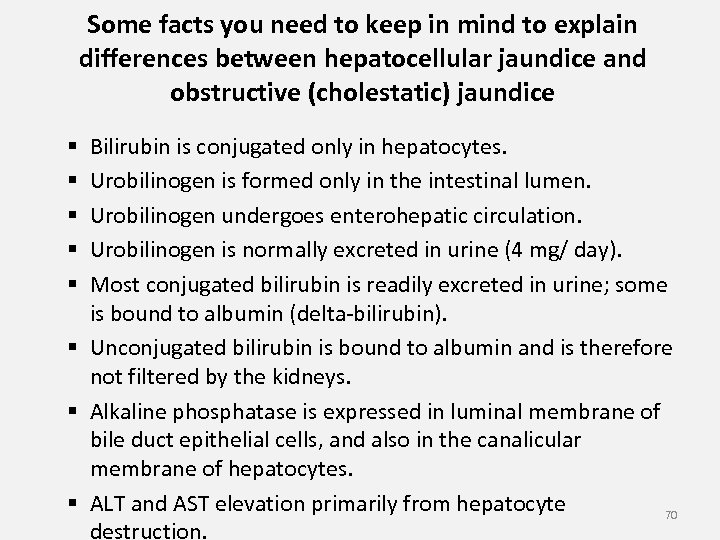

Some facts you need to keep in mind to explain differences between hepatocellular jaundice and obstructive (cholestatic) jaundice Bilirubin is conjugated only in hepatocytes. Urobilinogen is formed only in the intestinal lumen. Urobilinogen undergoes enterohepatic circulation. Urobilinogen is normally excreted in urine (4 mg/ day). Most conjugated bilirubin is readily excreted in urine; some is bound to albumin (delta-bilirubin). § Unconjugated bilirubin is bound to albumin and is therefore not filtered by the kidneys. § Alkaline phosphatase is expressed in luminal membrane of bile duct epithelial cells, and also in the canalicular membrane of hepatocytes. § ALT and AST elevation primarily from hepatocyte 70 destruction. § § §

Why does acute diarrhea often result in metabolic acidosis? Colon is normally presented with 2 liters of fluid per day… Normally, up to 4 liters of fluid can be absorbed in the colon… Much of Cl is absorbed in exchange for secretion of HCO 3 Na and Cl absorption is prioritized in the colon, and with it water follows. • ECF volume defense prioritized over ECF p. H defense. • Metabolic acidosis due to loss of HCO 3. • • 71

Anion Gap in Diarrhea • Typically, AG is normal. • Reason: there is no increase in an unmeasured anion! • In diarrheas complicated by hypotension, shock and acute renal injury, AG may increase as a result of accumulation of lactate and other anions. 72

06fb6a3f26c446bfd07989a7eda1094e.ppt