ff8841d789261376852aa819cfb8ebcc.ppt

- Количество слайдов: 17

Prison Mental Illness: America's jails and prisons house more mentally ill individuals than all of the Nation's psychiatric hospitals combined. (US Congress) A National Crisis, A Moral Outrage

Prison Mental Illness: America's jails and prisons house more mentally ill individuals than all of the Nation's psychiatric hospitals combined. (US Congress) A National Crisis, A Moral Outrage

Understanding the Problem: A History During the 1950 -60 s a new approach was taken to the treatment of mental illness. Called deinstitutionalization, politicians sought to close state psychiatric hospitals and replace them with community-based treatment centers. Intended as a humane, liberating and progressive alternative to indefinite hospitalization, deinstitutionalization did not work out as planned. As the majority of state psychiatric hospitals were shut down, mental health need continued to grow and the severely mentally ill were left to fend for themselves. Appropriate resources were not allocated to outpatient centers whose clinicians were unable to adequately serve their overflowing caseloads. By the 70 s, a new trend began to emerge: transinstitutionalization, “the transfer of institutional populations from hospitals to jails, nursing homes, and shelters. ”* Unable to function in society, former psychiatric patients as well as the next generation of mentally ill Americans, were landing in prison at unprecedented rates. Furthermore, during the 1980 s and 1990 s, tougher sentencing, especially for drugs crimes, began to emerge. This has specifically affected the mentally ill because of the frequent comorbidity of mental illness and substance abuse. According to the Department of Justice, 45. 5% of all American inmates suffer from both issues.

Understanding the Problem: A History During the 1950 -60 s a new approach was taken to the treatment of mental illness. Called deinstitutionalization, politicians sought to close state psychiatric hospitals and replace them with community-based treatment centers. Intended as a humane, liberating and progressive alternative to indefinite hospitalization, deinstitutionalization did not work out as planned. As the majority of state psychiatric hospitals were shut down, mental health need continued to grow and the severely mentally ill were left to fend for themselves. Appropriate resources were not allocated to outpatient centers whose clinicians were unable to adequately serve their overflowing caseloads. By the 70 s, a new trend began to emerge: transinstitutionalization, “the transfer of institutional populations from hospitals to jails, nursing homes, and shelters. ”* Unable to function in society, former psychiatric patients as well as the next generation of mentally ill Americans, were landing in prison at unprecedented rates. Furthermore, during the 1980 s and 1990 s, tougher sentencing, especially for drugs crimes, began to emerge. This has specifically affected the mentally ill because of the frequent comorbidity of mental illness and substance abuse. According to the Department of Justice, 45. 5% of all American inmates suffer from both issues.

Statistics: The Scope of the Problem In Pennsylvania. . . • In 2007, the Dept. of Correction reported • America imprisons 1 in 100 of its adult citizens, giving it the world’s highest rate of incarceration. (Pew) • Totaled together, in 2005 there were at least 1, 185, 500 (55% of the prison population) mentally ill Americans incarcerated according to DOJ’s conservative estimate. * • Of these, 6% of the prison population can be classified as “severely mentally ill” with illnesses such as schizophrenia, major depression, and bipolar disorder. (National Alliance on Mental Illness) • About 75% of all inmates who had a mental 21. 5 % of inmates were on the Mental Health Roster, meaning they are mentally ill and in treatment. 2. 8% were designated as “severely” mentally ill. This number only represents people whom the DOC has allowed onto the roster and thus designated as MI, and is likely an underestimate. • For the 11, 081 people on both rosters, the DOC employed 170 “psychology staff”. A ratio of 1 staff member to over 65 inmates. (DOC) • For those correctional officers and supervisors assigned to special needs units, the state requires a two-day training. (PBS) * 705, 600 state prisoners (56%), 78, 800 federal prisoners (45%), 479, 900 jail inmates (64%)

Statistics: The Scope of the Problem In Pennsylvania. . . • In 2007, the Dept. of Correction reported • America imprisons 1 in 100 of its adult citizens, giving it the world’s highest rate of incarceration. (Pew) • Totaled together, in 2005 there were at least 1, 185, 500 (55% of the prison population) mentally ill Americans incarcerated according to DOJ’s conservative estimate. * • Of these, 6% of the prison population can be classified as “severely mentally ill” with illnesses such as schizophrenia, major depression, and bipolar disorder. (National Alliance on Mental Illness) • About 75% of all inmates who had a mental 21. 5 % of inmates were on the Mental Health Roster, meaning they are mentally ill and in treatment. 2. 8% were designated as “severely” mentally ill. This number only represents people whom the DOC has allowed onto the roster and thus designated as MI, and is likely an underestimate. • For the 11, 081 people on both rosters, the DOC employed 170 “psychology staff”. A ratio of 1 staff member to over 65 inmates. (DOC) • For those correctional officers and supervisors assigned to special needs units, the state requires a two-day training. (PBS) * 705, 600 state prisoners (56%), 78, 800 federal prisoners (45%), 479, 900 jail inmates (64%)

What’s Wrong with Incarcerating the Mentally Ill? The mentally ill face innumerable obstacles in every facet of society. It is harder for them to find and maintain employment, housing and acceptance in a society whose rules are sometimes a foreign language. In court, they are less able to assist in their own defense. In prison, a terrifying experience for anyone, the mentally ill are less able to cope with the tense, violent atmosphere and many rules than their peers. Fact: According to the DOJ, mentally ill inmates in state prisons serve on average 15 months longer than other inmates for infractions committed while in psychiatric crisis. In addition, they face parole boards already reluctant to release them into communities which inevitably lack the services they need. (PBS/DOJ) Fact: Inmates with mental illness are denied justice at every juncture. Fact: Inmates with mental illness are more likely to be sexually victimized while in prison than their neurotypical peers. (US Congress) Fact: The mentally ill are disproportionately represented among prisoners in segregation. A result of poor behavioral control, MI inmates land in solitary confinement where they are held in a small cell with no human contact for up to 23 hours per day. Psychiatric research has shown the effects of solitary to be devastating for the healthiest of people; for individuals with MI, solitary confinement is akin to torture. Incarcerating the severely mentally ill does not make anyone safer. The behavior of severely ill inmates endangers guards, other inmates and of course, the individuals themselves. Ultimately, the majority of mentally ill inmates are released back into communities more sick and more dangerous than before. Fact: Prisons are not psychiatric hospitals. Prison mental health care is FACT: America's jails and prisons house more mentally ill individuals than all of the Nation's psychiatric hospitals combined. (US Congress) FACT: Prison is a useless and inhumane alternative to treatment for the mentally ill. severely limited by lack of finances and professionals willing to work in such a challenging setting. Prisons are simply illequipped to handle the complex needs of the mentally ill responsibly, ethically and humanely. . Fact: Mentally ill inmates are often unable to cope with and understand the myriad prison rules. They incur more disciplinary infractions than their peers; in fact 58% of all state prisoners with a diagnosed MI had been charged with rule violations. In effect, they are punished for their illnesses.

What’s Wrong with Incarcerating the Mentally Ill? The mentally ill face innumerable obstacles in every facet of society. It is harder for them to find and maintain employment, housing and acceptance in a society whose rules are sometimes a foreign language. In court, they are less able to assist in their own defense. In prison, a terrifying experience for anyone, the mentally ill are less able to cope with the tense, violent atmosphere and many rules than their peers. Fact: According to the DOJ, mentally ill inmates in state prisons serve on average 15 months longer than other inmates for infractions committed while in psychiatric crisis. In addition, they face parole boards already reluctant to release them into communities which inevitably lack the services they need. (PBS/DOJ) Fact: Inmates with mental illness are denied justice at every juncture. Fact: Inmates with mental illness are more likely to be sexually victimized while in prison than their neurotypical peers. (US Congress) Fact: The mentally ill are disproportionately represented among prisoners in segregation. A result of poor behavioral control, MI inmates land in solitary confinement where they are held in a small cell with no human contact for up to 23 hours per day. Psychiatric research has shown the effects of solitary to be devastating for the healthiest of people; for individuals with MI, solitary confinement is akin to torture. Incarcerating the severely mentally ill does not make anyone safer. The behavior of severely ill inmates endangers guards, other inmates and of course, the individuals themselves. Ultimately, the majority of mentally ill inmates are released back into communities more sick and more dangerous than before. Fact: Prisons are not psychiatric hospitals. Prison mental health care is FACT: America's jails and prisons house more mentally ill individuals than all of the Nation's psychiatric hospitals combined. (US Congress) FACT: Prison is a useless and inhumane alternative to treatment for the mentally ill. severely limited by lack of finances and professionals willing to work in such a challenging setting. Prisons are simply illequipped to handle the complex needs of the mentally ill responsibly, ethically and humanely. . Fact: Mentally ill inmates are often unable to cope with and understand the myriad prison rules. They incur more disciplinary infractions than their peers; in fact 58% of all state prisoners with a diagnosed MI had been charged with rule violations. In effect, they are punished for their illnesses.

Incarcerating the Mentally Ill: Legal Issues and Standards We know that prison in general, and solitary confinement specifically, are not effective responses to crime committed by the mentally ill. We know that the conditions created by this atavistic system are backwards and inhumane. The next question is, by what laws are they regulated? There are several legal standards relevant to the treatment of mentally inmates: The 8 th Amendment of the US Constitution: Also known as the “Cruel and Unusual Punishment Clause”, this fundamental Constitutional law protects an individual’s right to be free from “the wanton infliction of pain”. Lawyers have argued that treatment such as the use of prolonged isolation in solitary confinement on mentally inmates constitutes cruel and unusual punishment. Unfortunately, recent legislation (PLRA) creating administrative roadblocks, unsympathetic juries and judges and lack of access to the court system has made it difficult for inmates to argue their 8 th Amendment cases. Due Process: Due Process is the legal guarantee (5 th/14 th Am. ) that government will respect a person’s Constitutional right to liberty The Supreme Court has found that this standard applies to prisoners in situations where the length of sentence may change (a “liberty interest”). According to Due Process, inmates have a right to be heard in front of an impartial decision maker with limited representation. This is extremely important for MI inmates whose frequent behavioral transgressions may result in lengthened sentences. Unfortunately, adherence to Due Process behind prison walls is cursory. Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA): The most frequently cited federal law in prison MH cases, the ADA ensures equal access for people with disabilities. Disability law firms have sued prison systems successfully contending that they fail to adequately accommodate and respect MI inmates’ legal right to equal access on the basis of psychiatric disability. International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (Torture Convention): This piece of international law was ratified by the US in 1992, giving it the same legal standing as federal statutory law. Its language prohibits “torture and other cruel, inhuman, or degrading treatment or punishment. ” Unfortunately, caveats added by the US have made these laws virtually unenforceable. ICCPR has not been used successfully in an American prison abuse suit.

Incarcerating the Mentally Ill: Legal Issues and Standards We know that prison in general, and solitary confinement specifically, are not effective responses to crime committed by the mentally ill. We know that the conditions created by this atavistic system are backwards and inhumane. The next question is, by what laws are they regulated? There are several legal standards relevant to the treatment of mentally inmates: The 8 th Amendment of the US Constitution: Also known as the “Cruel and Unusual Punishment Clause”, this fundamental Constitutional law protects an individual’s right to be free from “the wanton infliction of pain”. Lawyers have argued that treatment such as the use of prolonged isolation in solitary confinement on mentally inmates constitutes cruel and unusual punishment. Unfortunately, recent legislation (PLRA) creating administrative roadblocks, unsympathetic juries and judges and lack of access to the court system has made it difficult for inmates to argue their 8 th Amendment cases. Due Process: Due Process is the legal guarantee (5 th/14 th Am. ) that government will respect a person’s Constitutional right to liberty The Supreme Court has found that this standard applies to prisoners in situations where the length of sentence may change (a “liberty interest”). According to Due Process, inmates have a right to be heard in front of an impartial decision maker with limited representation. This is extremely important for MI inmates whose frequent behavioral transgressions may result in lengthened sentences. Unfortunately, adherence to Due Process behind prison walls is cursory. Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA): The most frequently cited federal law in prison MH cases, the ADA ensures equal access for people with disabilities. Disability law firms have sued prison systems successfully contending that they fail to adequately accommodate and respect MI inmates’ legal right to equal access on the basis of psychiatric disability. International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (Torture Convention): This piece of international law was ratified by the US in 1992, giving it the same legal standing as federal statutory law. Its language prohibits “torture and other cruel, inhuman, or degrading treatment or punishment. ” Unfortunately, caveats added by the US have made these laws virtually unenforceable. ICCPR has not been used successfully in an American prison abuse suit.

Incarcerating the Mentally Ill: Professional Incarcerating the mentally ill: Standards Professional Standards Providing mental health treatment in prison is a challenge. From lack of resources to understaffing, professionals face many obstacles in treating their patients. Psychologists, physicians, social workers and nurses all have professional standards which they must uphold. An ethical dilemma arises when the realities of practicing in a prison conflict with the standards and expectations of a profession. For example, a prison psychologist has dual responsibilities: he or she must use his/her professional expertise to help prison officials manage an inmate while also maintaining the patient's confidentiality, an expectation dictated by the American Psychological Association. Below are some of the issues professionals face in trying to provide quality treatment to mentally ill inmates: Inadequate Screening/Monitoring: Despite screening requirements upon admittance, many mentally ill prisoners are not identified and thus left untreated. This due to inadequate screening methods, unqualified staff and disorganization. Lack of Treatment Plan: Outdated, psychotropic medication is frequently utilized as the sole treatment for prisoners with mental illness. In addition, it is difficult to ensure that proper administration and follow-up care occur. Lack of Confidentiality: In a prison setting, confidentiality is complicated by lack of private facilities for therapy sessions and staff apathy about importance of privacy issues. Instead, therapy sessions and healthcare consultations are often held through the patient's cell door. This lack of privacy causes the patient to withhold important personal information. Diagnoses of Malingering: Prisoners' mental health complaints are often dismissed as malingering, or “faking it” for attention or simply to be manipulative. Staffing: Mentally ill prisoners frequently lack access to the necessary range of various mental health professionals required for comprehensive treatment. Prisons often hire under-qualified staff as a means to lower costs; however, this staffing deficiency translates to inadequate healthcare and treatment options for prisoners. Lack of Access: According to the APA, “[t]imely and effective access to mental health treatment is the hallmark of adequate mental health care. ” 345 However, administrative regulations often prevent timely access to treatment forcing inmates to wait as long as several months just for their request to be processed

Incarcerating the Mentally Ill: Professional Incarcerating the mentally ill: Standards Professional Standards Providing mental health treatment in prison is a challenge. From lack of resources to understaffing, professionals face many obstacles in treating their patients. Psychologists, physicians, social workers and nurses all have professional standards which they must uphold. An ethical dilemma arises when the realities of practicing in a prison conflict with the standards and expectations of a profession. For example, a prison psychologist has dual responsibilities: he or she must use his/her professional expertise to help prison officials manage an inmate while also maintaining the patient's confidentiality, an expectation dictated by the American Psychological Association. Below are some of the issues professionals face in trying to provide quality treatment to mentally ill inmates: Inadequate Screening/Monitoring: Despite screening requirements upon admittance, many mentally ill prisoners are not identified and thus left untreated. This due to inadequate screening methods, unqualified staff and disorganization. Lack of Treatment Plan: Outdated, psychotropic medication is frequently utilized as the sole treatment for prisoners with mental illness. In addition, it is difficult to ensure that proper administration and follow-up care occur. Lack of Confidentiality: In a prison setting, confidentiality is complicated by lack of private facilities for therapy sessions and staff apathy about importance of privacy issues. Instead, therapy sessions and healthcare consultations are often held through the patient's cell door. This lack of privacy causes the patient to withhold important personal information. Diagnoses of Malingering: Prisoners' mental health complaints are often dismissed as malingering, or “faking it” for attention or simply to be manipulative. Staffing: Mentally ill prisoners frequently lack access to the necessary range of various mental health professionals required for comprehensive treatment. Prisons often hire under-qualified staff as a means to lower costs; however, this staffing deficiency translates to inadequate healthcare and treatment options for prisoners. Lack of Access: According to the APA, “[t]imely and effective access to mental health treatment is the hallmark of adequate mental health care. ” 345 However, administrative regulations often prevent timely access to treatment forcing inmates to wait as long as several months just for their request to be processed

Women, Prison and Mental Illness It is widely known that female prison population is vastly different from the male counterpart. Incarcerated women tend to be more mentally ill, drug-addicted, abused and disadvantaged than male inmates. The crimes they commit are less violent, most frequently related to drug possession and sale. The majority of female violent crime is committed in response to abuse. Despite these differences and their critical implications, women are incarcerated in a system designed for males, which offers them fewer resources and less treatment than their male counterparts because of their minority presence. Female inmates attempt suicide five times more often than their female counterparts in the community and twice as often as their incarcerated male counterparts. (SHMAI) More than half of all female prisoners are serving time for a drug offense. (DOJ) Female inmates in jails and prisons are less likely than men to receive the services they need. (Northwestern) In 2004 the DOJ reported 877 cases of substantiated sexual abuse by guards against female prisoners. This number only represents cases that were reported. Most are not. Pre-prison sexual/physical abuse statistics for women range from 68% (DOJ), to 90% (NY DOC). An estimated 73% of females in State prisons, compared to 55% of male inmates, had a mental health problem. (DOJ) Nearly two-thirds of the women serving a sentence for a violent crime had victimized a relative, intimate, or someone else they knew.

Women, Prison and Mental Illness It is widely known that female prison population is vastly different from the male counterpart. Incarcerated women tend to be more mentally ill, drug-addicted, abused and disadvantaged than male inmates. The crimes they commit are less violent, most frequently related to drug possession and sale. The majority of female violent crime is committed in response to abuse. Despite these differences and their critical implications, women are incarcerated in a system designed for males, which offers them fewer resources and less treatment than their male counterparts because of their minority presence. Female inmates attempt suicide five times more often than their female counterparts in the community and twice as often as their incarcerated male counterparts. (SHMAI) More than half of all female prisoners are serving time for a drug offense. (DOJ) Female inmates in jails and prisons are less likely than men to receive the services they need. (Northwestern) In 2004 the DOJ reported 877 cases of substantiated sexual abuse by guards against female prisoners. This number only represents cases that were reported. Most are not. Pre-prison sexual/physical abuse statistics for women range from 68% (DOJ), to 90% (NY DOC). An estimated 73% of females in State prisons, compared to 55% of male inmates, had a mental health problem. (DOJ) Nearly two-thirds of the women serving a sentence for a violent crime had victimized a relative, intimate, or someone else they knew.

Conclusions: What Needs to Be Done The prison mental health crisis is cyclical. Lack of safe and effective alternatives leave judges little choice but to sentence these individuals to prison, a toxic environment but perhaps the only in which they are likely to receive treatment. Upon release, mentally ill inmates have few places to turn. As one Ohio inmate, Sigmond Clark, put it: "Six days with $75 in my pocket. Fare the best way you can, man. We done took 12 years out of your life, and you're mentally ill … do what you can for yourself. According to PBS, “when Clark's $75 ran out six days after his release, he violated his parole by stealing a woman's purse. He was given a two-year mandatory sentence and was returned to Ohio corrections to continue his original sentence of 11 to 40 years. ” The Consensus Project, run by the Council of State Governments, released these recommendations to improve services for released mentally ill inmates: 1. Implement an evidence-based practices into public mental health. 2. Integration of Services: integrate different services and fields of medicine to provide comprehensive care. 3. Co-Occurring Disorders: implement a holistic, integrated approach to treatment of persons with co-occurring mental illness and substance abuse disorders 4. Housing: Make affordable, coordinated public housing with array of options to meet different levels of need. 5. Workforce: Plan to increase the supply of and to train skilled mental health providers. 6. Consumer and Family Member Involvement: Involve participants and their families throughout the process to ensure all that people with MI are accessing all benefits for which they are eligible. 7. Cultural Competency: employ minorities and develop outreach programs to make services available to members of minority communities. 8. Accountability: Use customer evaluations and utilize performance measures in budgeting, contracting, and managing mental health services. 9. Advocacy: Create public support for the necessary investment in these services.

Conclusions: What Needs to Be Done The prison mental health crisis is cyclical. Lack of safe and effective alternatives leave judges little choice but to sentence these individuals to prison, a toxic environment but perhaps the only in which they are likely to receive treatment. Upon release, mentally ill inmates have few places to turn. As one Ohio inmate, Sigmond Clark, put it: "Six days with $75 in my pocket. Fare the best way you can, man. We done took 12 years out of your life, and you're mentally ill … do what you can for yourself. According to PBS, “when Clark's $75 ran out six days after his release, he violated his parole by stealing a woman's purse. He was given a two-year mandatory sentence and was returned to Ohio corrections to continue his original sentence of 11 to 40 years. ” The Consensus Project, run by the Council of State Governments, released these recommendations to improve services for released mentally ill inmates: 1. Implement an evidence-based practices into public mental health. 2. Integration of Services: integrate different services and fields of medicine to provide comprehensive care. 3. Co-Occurring Disorders: implement a holistic, integrated approach to treatment of persons with co-occurring mental illness and substance abuse disorders 4. Housing: Make affordable, coordinated public housing with array of options to meet different levels of need. 5. Workforce: Plan to increase the supply of and to train skilled mental health providers. 6. Consumer and Family Member Involvement: Involve participants and their families throughout the process to ensure all that people with MI are accessing all benefits for which they are eligible. 7. Cultural Competency: employ minorities and develop outreach programs to make services available to members of minority communities. 8. Accountability: Use customer evaluations and utilize performance measures in budgeting, contracting, and managing mental health services. 9. Advocacy: Create public support for the necessary investment in these services.

Questions for the future Questions: Professional standards exist for practitioners of medicine and psychology to protect the dignity, safety and comfort of their clients. To be in accordance with these expectations, are there certain assignments or circumstances in which professionals cannot work? What basic standards must be met to remain in keeping with professional ethics (for psychologists, nurses and physicians)? In circumstances where resources such as supplies, medicine, and staff needed to maintain standard-of-care treatment are limited, in what ways are the professional's responsibility to industry standards and guidelines adjusted? To what extent is a professional expected to follow up with and ensure that the treatment he/she prescribes is made available to the patient? Does this standard change for the professional who practices under the auspices of a non-medical institution such as a prison? In treating institutionalized persons whose situations may prevent optimal or standard-of-care treatment, what is expected of the professional? Should she ALWAYS treat/evaluate the inmate to the best of his/her ability? Are there any situations in which a professional's responsibility to ethical standards overrides the imperative to offer medical/psychological attention to someone in his/her care? If the outcome of providing professional care/assessment may result in an ethical violation (such as participation in an execution or torture) or in a change of circumstances that would be medically/psychologically contraindicated (such as the placement of a person with psychosis in solitary confinement), what is expected of the professional? Should he or she withhold services? To what extent is s/he considered culpable: professionally, ethically and legally, for adverse (medical and/or ethical) outcomes of care? What can be done to better allow professionals to balance the competing demands of their profession with the reality of prison practice? To whom is the professional's responsibility greater, his/her employer or to those in his/her care? What is expected of the practitioner in situations where those needs conflict? Do professional organizations have a responsibility to lobby for changes in law or policy that reflect the outcomes of research within their field?

Questions for the future Questions: Professional standards exist for practitioners of medicine and psychology to protect the dignity, safety and comfort of their clients. To be in accordance with these expectations, are there certain assignments or circumstances in which professionals cannot work? What basic standards must be met to remain in keeping with professional ethics (for psychologists, nurses and physicians)? In circumstances where resources such as supplies, medicine, and staff needed to maintain standard-of-care treatment are limited, in what ways are the professional's responsibility to industry standards and guidelines adjusted? To what extent is a professional expected to follow up with and ensure that the treatment he/she prescribes is made available to the patient? Does this standard change for the professional who practices under the auspices of a non-medical institution such as a prison? In treating institutionalized persons whose situations may prevent optimal or standard-of-care treatment, what is expected of the professional? Should she ALWAYS treat/evaluate the inmate to the best of his/her ability? Are there any situations in which a professional's responsibility to ethical standards overrides the imperative to offer medical/psychological attention to someone in his/her care? If the outcome of providing professional care/assessment may result in an ethical violation (such as participation in an execution or torture) or in a change of circumstances that would be medically/psychologically contraindicated (such as the placement of a person with psychosis in solitary confinement), what is expected of the professional? Should he or she withhold services? To what extent is s/he considered culpable: professionally, ethically and legally, for adverse (medical and/or ethical) outcomes of care? What can be done to better allow professionals to balance the competing demands of their profession with the reality of prison practice? To whom is the professional's responsibility greater, his/her employer or to those in his/her care? What is expected of the practitioner in situations where those needs conflict? Do professional organizations have a responsibility to lobby for changes in law or policy that reflect the outcomes of research within their field?

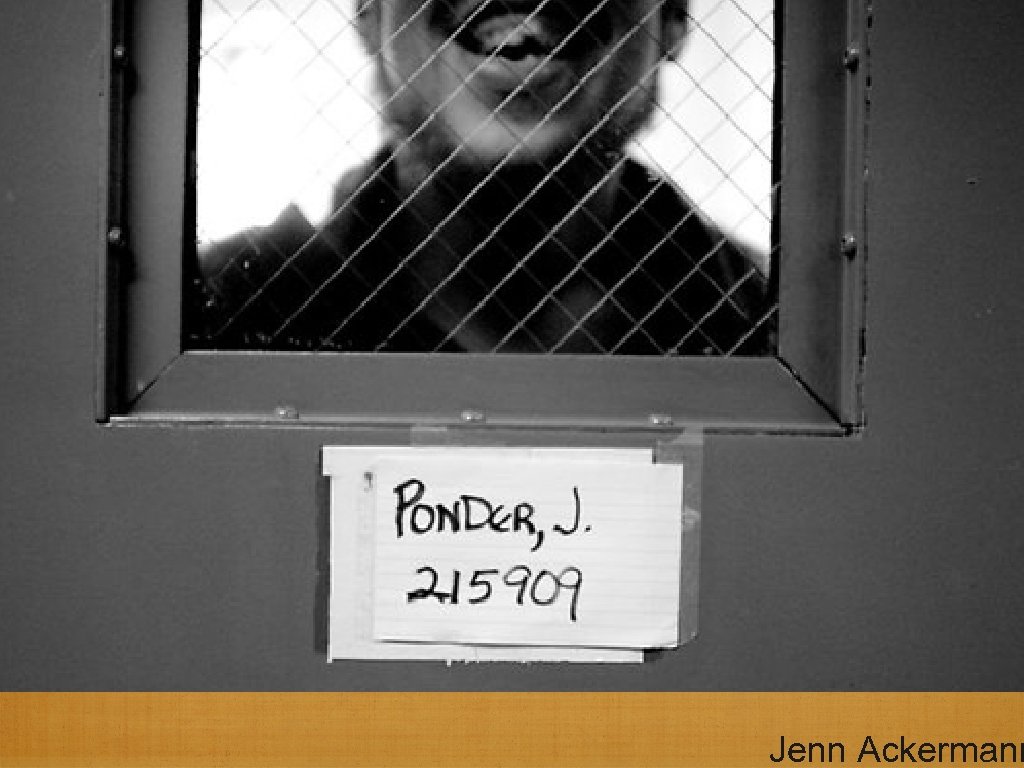

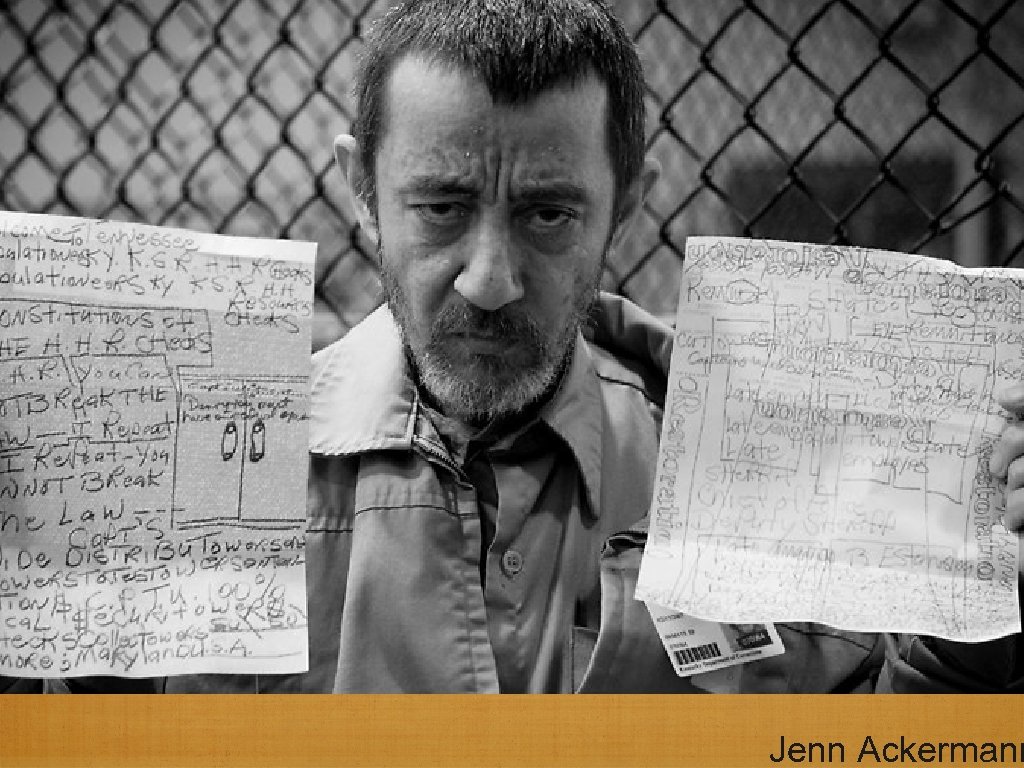

Jenn Ackermann

Jenn Ackermann

Jenn Ackermann

Jenn Ackermann

Jenn Ackermann

Jenn Ackermann

Jenn Ackermann

Jenn Ackermann

Jenn Ackermann

Jenn Ackermann

Jenn Ackermann

Jenn Ackermann

Jenn Ackermann

Jenn Ackermann

Bibliography: Professional Standards/orgs: http: //www. psych. org/Main. Menu/Psychiatric. Practice/Ethics/Resources. Standards. aspxhttp: //www. bazelon. org/index. html. Bazelon Center for Mental Health Law http: //www. apa. org/ethics/code 1992. html http: //www. bazelon. org/issues/criminalization/factsheets/pdfs/index. htm. Bazelon Center for Mental Health Law: Fact Sheet on Criminalization of MI Prisonershttp: //www. mhasp. org/advocacy/systems. html. Mental Health Association of Southern Pennsylvaniahttp: //www. nami. org/Template. cfm? Section=Issue_Spotlights&template=/Content. Management/Content. Display. cfm&Content. ID=76792 NAMI's official stance regarding criminalization of the mentally ill; includes official statements regarding access to treatment while incarcerated, and training/education of service personnel. Stuart Grassian, MD, Solitary Confinement Report: http: //www. nami. org/Template. cfm? Section=Issue_Spotlights&template=/Content. Management/Content. Display. cfm&Content. ID=76792 om/gview? a=v&q=cache: Yhm 87 k. Csl 7 o. J: www. prisonco mmission. org/statements/grassian_stuart_long. pdf+stuart+grassian+report&hl=en&gl=us “Hellhole”, New Yorker article about solitary by Atul Gawande: http: //www. newyorker. com/reporting/2009/03/30/090330 fa_fact_gawande Legal Standards: http: //www. law. harvard. edu/students/orgs/crcl/vol 41_2/fellner. pdf. A Harvard Law document about mental illness and prison ruleshttp: //www. stanford. edu/group/psylawseminar/Ethics. htm http: //www. abanet. org/crimjust/standards/prisoners_status. html STATE/FED/STATS: http: //www. pacode. com/secure/data/049/chapter 41/s 41. 61. htmlhttp: //www. hrw. org/reports/2003/usa 1003/index. htm. An extremely detailed and throroughly rssearched report on the mentally ill in US prisons. DOJ: http: //ojp. usdoj. gov/bjs/pub/ascii/mhppji. txthttp: //ojp. usdoj. gov/bjs/pub/press/mhppjipr. htmhttp: //suicideandmentalhealthassociationinternational. org/preventionprison. html Multimedia: www. jennackerman. com: Beautiful prison photography, focus on MIwww. pbs. org/wgbh/pages/frontline/shows/asylums. AMAZING documentary on MI in prison, great links and resources. t

Bibliography: Professional Standards/orgs: http: //www. psych. org/Main. Menu/Psychiatric. Practice/Ethics/Resources. Standards. aspxhttp: //www. bazelon. org/index. html. Bazelon Center for Mental Health Law http: //www. apa. org/ethics/code 1992. html http: //www. bazelon. org/issues/criminalization/factsheets/pdfs/index. htm. Bazelon Center for Mental Health Law: Fact Sheet on Criminalization of MI Prisonershttp: //www. mhasp. org/advocacy/systems. html. Mental Health Association of Southern Pennsylvaniahttp: //www. nami. org/Template. cfm? Section=Issue_Spotlights&template=/Content. Management/Content. Display. cfm&Content. ID=76792 NAMI's official stance regarding criminalization of the mentally ill; includes official statements regarding access to treatment while incarcerated, and training/education of service personnel. Stuart Grassian, MD, Solitary Confinement Report: http: //www. nami. org/Template. cfm? Section=Issue_Spotlights&template=/Content. Management/Content. Display. cfm&Content. ID=76792 om/gview? a=v&q=cache: Yhm 87 k. Csl 7 o. J: www. prisonco mmission. org/statements/grassian_stuart_long. pdf+stuart+grassian+report&hl=en&gl=us “Hellhole”, New Yorker article about solitary by Atul Gawande: http: //www. newyorker. com/reporting/2009/03/30/090330 fa_fact_gawande Legal Standards: http: //www. law. harvard. edu/students/orgs/crcl/vol 41_2/fellner. pdf. A Harvard Law document about mental illness and prison ruleshttp: //www. stanford. edu/group/psylawseminar/Ethics. htm http: //www. abanet. org/crimjust/standards/prisoners_status. html STATE/FED/STATS: http: //www. pacode. com/secure/data/049/chapter 41/s 41. 61. htmlhttp: //www. hrw. org/reports/2003/usa 1003/index. htm. An extremely detailed and throroughly rssearched report on the mentally ill in US prisons. DOJ: http: //ojp. usdoj. gov/bjs/pub/ascii/mhppji. txthttp: //ojp. usdoj. gov/bjs/pub/press/mhppjipr. htmhttp: //suicideandmentalhealthassociationinternational. org/preventionprison. html Multimedia: www. jennackerman. com: Beautiful prison photography, focus on MIwww. pbs. org/wgbh/pages/frontline/shows/asylums. AMAZING documentary on MI in prison, great links and resources. t