c3d0a3a39dff607ff738b20c7310d87d.ppt

- Количество слайдов: 26

Principles of Embedded Computation Rajeev Alur University of Pennsylvania www. cis. upenn. edu/~alur/ Faculty Research Seminar, September 2005

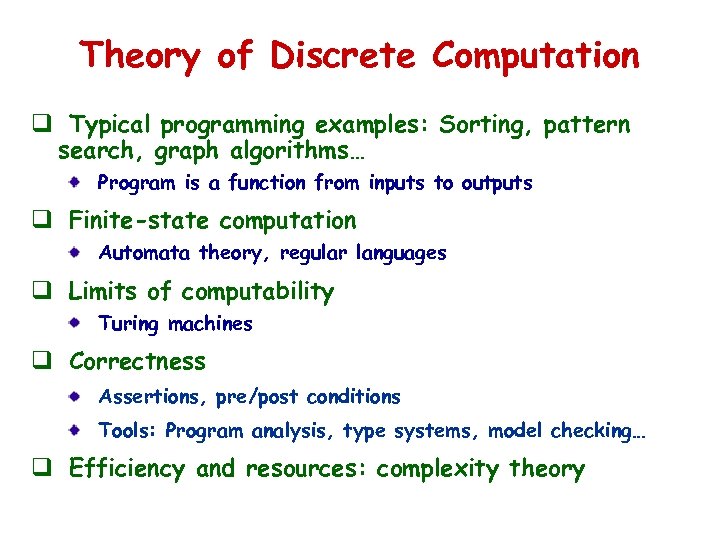

Theory of Discrete Computation q Typical programming examples: Sorting, pattern search, graph algorithms… Program is a function from inputs to outputs q Finite-state computation Automata theory, regular languages q Limits of computability Turing machines q Correctness Assertions, pre/post conditions Tools: Program analysis, type systems, model checking… q Efficiency and resources: complexity theory

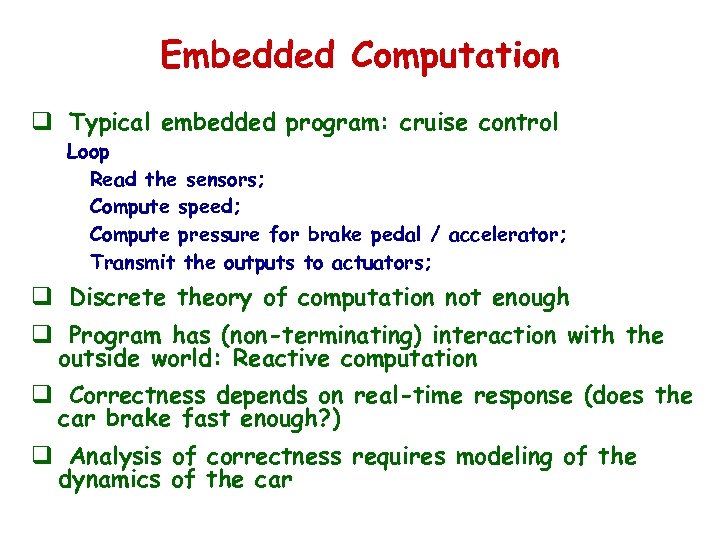

Embedded Computation q Typical embedded program: cruise control Loop Read the sensors; Compute speed; Compute pressure for brake pedal / accelerator; Transmit the outputs to actuators; q Discrete theory of computation not enough q Program has (non-terminating) interaction with the outside world: Reactive computation q Correctness depends on real-time response (does the car brake fast enough? ) q Analysis of correctness requires modeling of the dynamics of the car

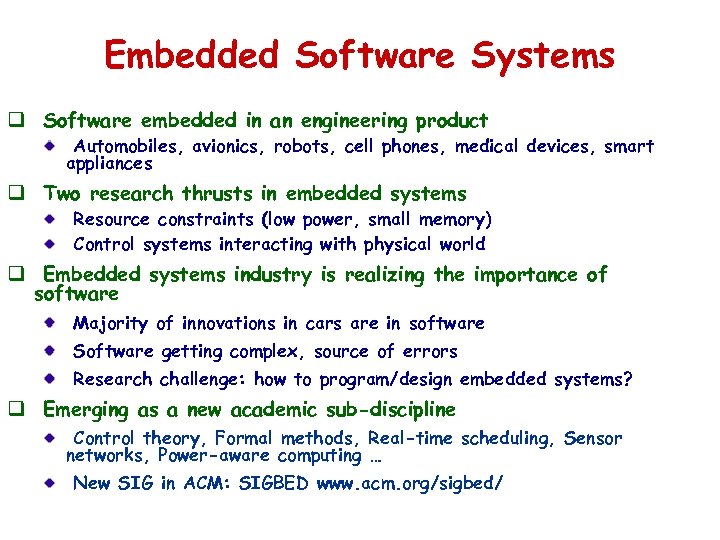

Embedded Software Systems q Software embedded in an engineering product Automobiles, avionics, robots, cell phones, medical devices, smart appliances q Two research thrusts in embedded systems Resource constraints (low power, small memory) Control systems interacting with physical world q Embedded systems industry is realizing the importance of software Majority of innovations in cars are in software Software getting complex, source of errors Research challenge: how to program/design embedded systems? q Emerging as a new academic sub-discipline Control theory, Formal methods, Real-time scheduling, Sensor networks, Power-aware computing … New SIG in ACM: SIGBED www. acm. org/sigbed/

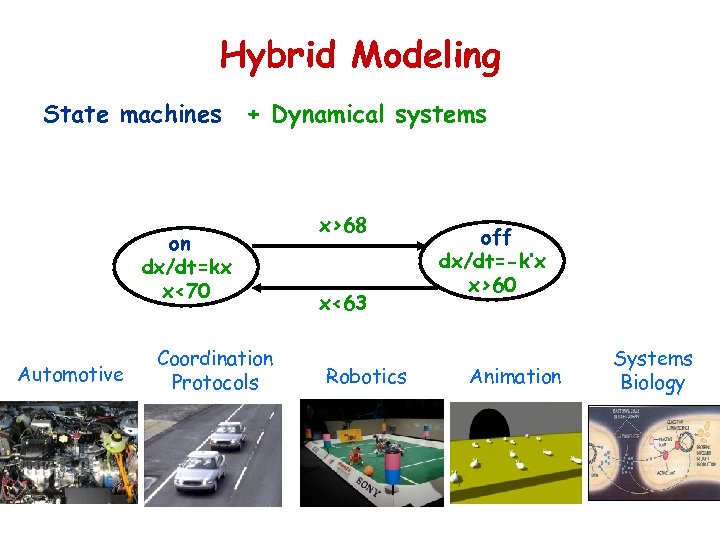

Hybrid Modeling State machines + Dynamical systems on dx/dt=kx x<70 Automotive Coordination Protocols x>68 x<63 Robotics off dx/dt=-k’x x>60 Animation Systems Biology

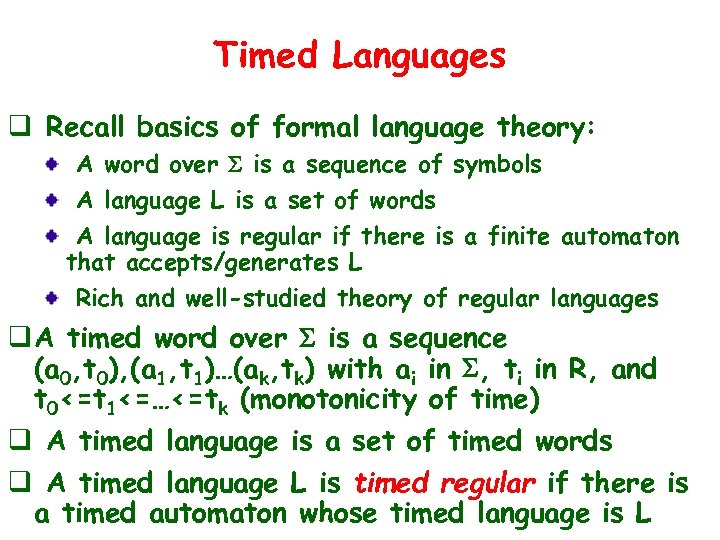

Timed Languages q Recall basics of formal language theory: A word over S is a sequence of symbols A language L is a set of words A language is regular if there is a finite automaton that accepts/generates L Rich and well-studied theory of regular languages q A timed word over S is a sequence (a 0, t 0), (a 1, t 1)…(ak, tk) with ai in S, ti in R, and t 0<=t 1<=…<=tk (monotonicity of time) q A timed language is a set of timed words q A timed language L is timed regular if there is a timed automaton whose timed language is L

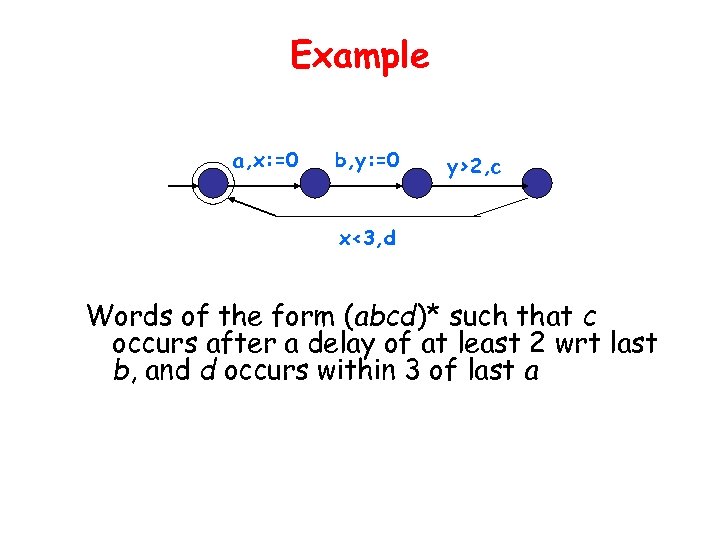

Example a, x: =0 b, y: =0 y>2, c x<3, d Words of the form (abcd)* such that c occurs after a delay of at least 2 wrt last b, and d occurs within 3 of last a

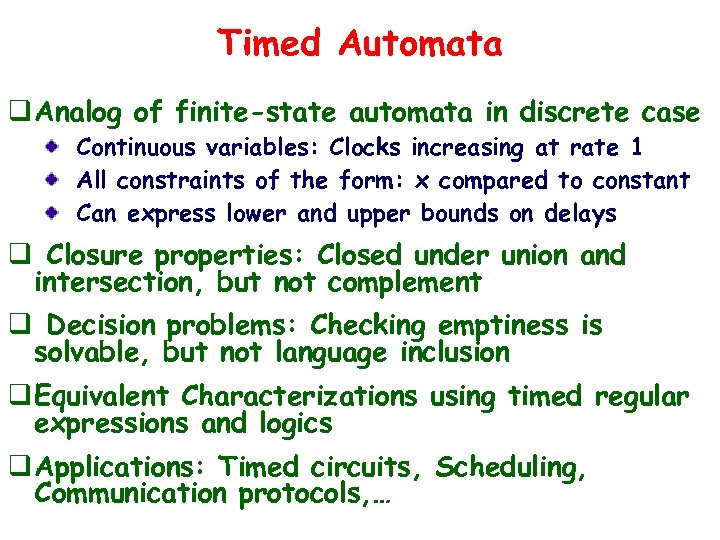

Timed Automata q Analog of finite-state automata in discrete case Continuous variables: Clocks increasing at rate 1 All constraints of the form: x compared to constant Can express lower and upper bounds on delays q Closure properties: Closed under union and intersection, but not complement q Decision problems: Checking emptiness is solvable, but not language inclusion q Equivalent Characterizations using timed regular expressions and logics q Applications: Timed circuits, Scheduling, Communication protocols, …

Untiming q Given a timed language L over S the language Untime(L) consists of words a 0, a 1, …ak such that there exists a timed word (a 0, t 0), (a 1, t 1)…(ak, tk) in L q Thm: If L is timed regular, then Untime(L) is regular. § proof by region construction

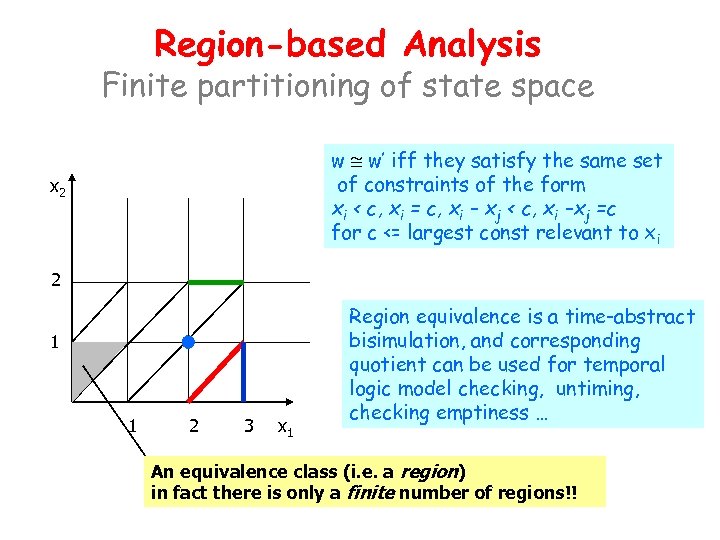

Region-based Analysis Finite partitioning of state space w @ w’ iff they satisfy the same set of constraints of the form xi < c, xi = c, xi – xj < c, xi –xj =c for c <= largest const relevant to xi x 2 2 1 1 2 3 x 1 Region equivalence is a time-abstract bisimulation, and corresponding quotient can be used for temporal logic model checking, untiming, checking emptiness … An equivalence class (i. e. a region) in fact there is only a finite number of regions!!

Model-Based Design q Benefits of model-based design Detecting errors in early stages Powerful and formal analysis Reusable components Automatic code generation q Many commercial tools are available for design of embedded control systems (e. g. Simulink) Typically, semantics is not formal Typically, only simulation-based analysis Code generation available, but precise relationship between model and code not understood

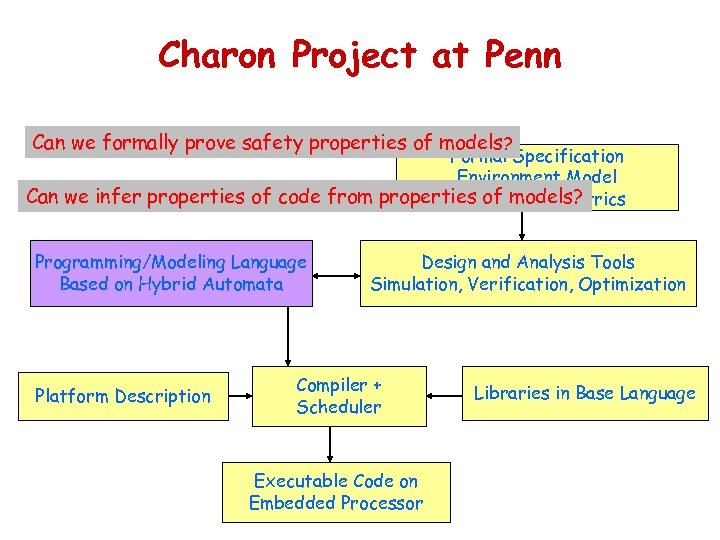

Charon Project at Penn Can we formally prove safety properties of models ? Formal Specification Environment Model Can we infer properties of code from properties of models? Performance Metrics Programming/Modeling Language Based on Hybrid Automata Platform Description Design and Analysis Tools Simulation, Verification, Optimization Compiler + Scheduler Executable Code on Embedded Processor Libraries in Base Language

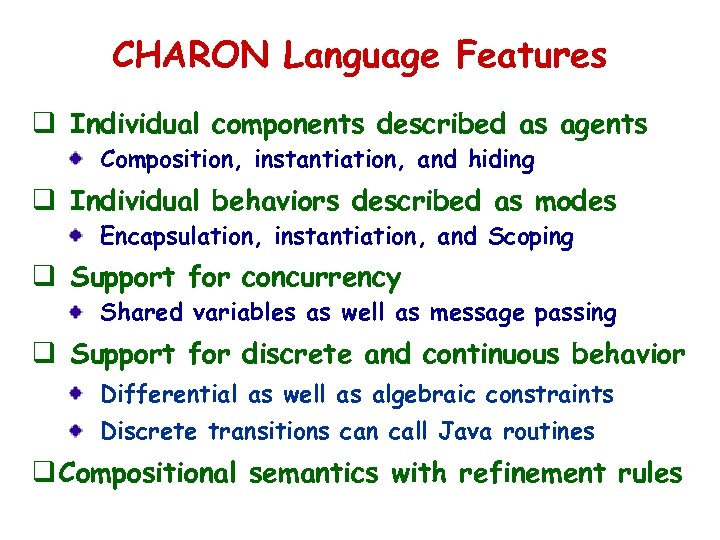

CHARON Language Features q Individual components described as agents Composition, instantiation, and hiding q Individual behaviors described as modes Encapsulation, instantiation, and Scoping q Support for concurrency Shared variables as well as message passing q Support for discrete and continuous behavior Differential as well as algebraic constraints Discrete transitions can call Java routines q Compositional semantics with refinement rules

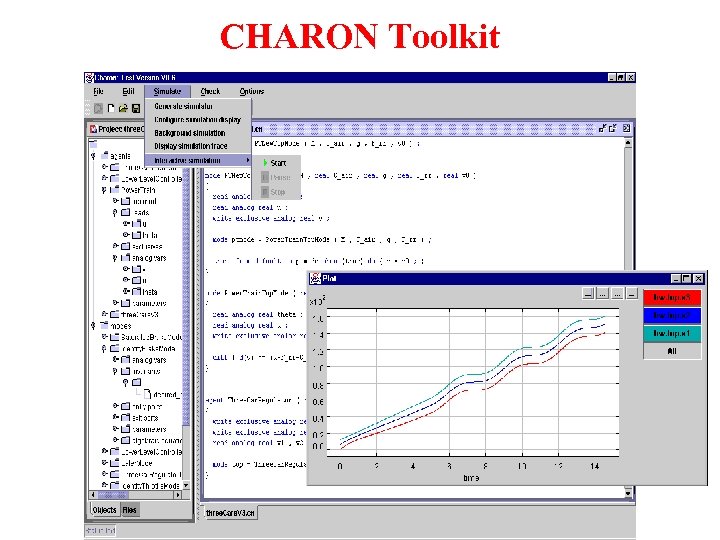

CHARON Toolkit

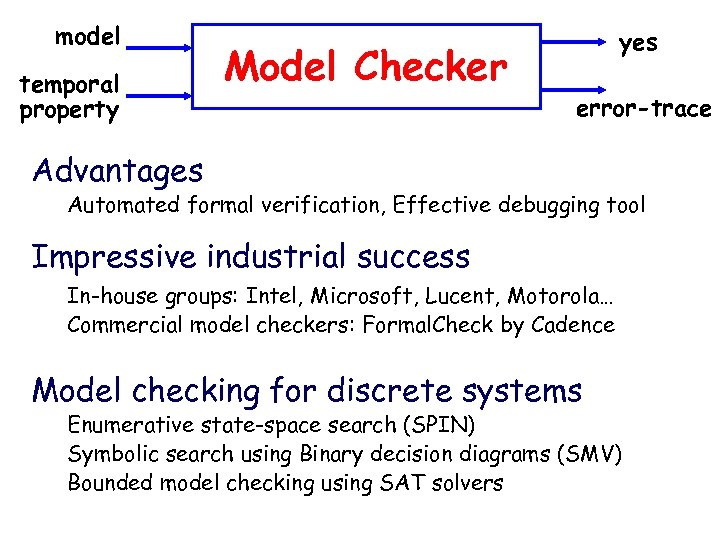

model temporal property Model Checker yes error-trace Advantages Automated formal verification, Effective debugging tool Impressive industrial success In-house groups: Intel, Microsoft, Lucent, Motorola… Commercial model checkers: Formal. Check by Cadence Model checking for discrete systems Enumerative state-space search (SPIN) Symbolic search using Binary decision diagrams (SMV) Bounded model checking using SAT solvers

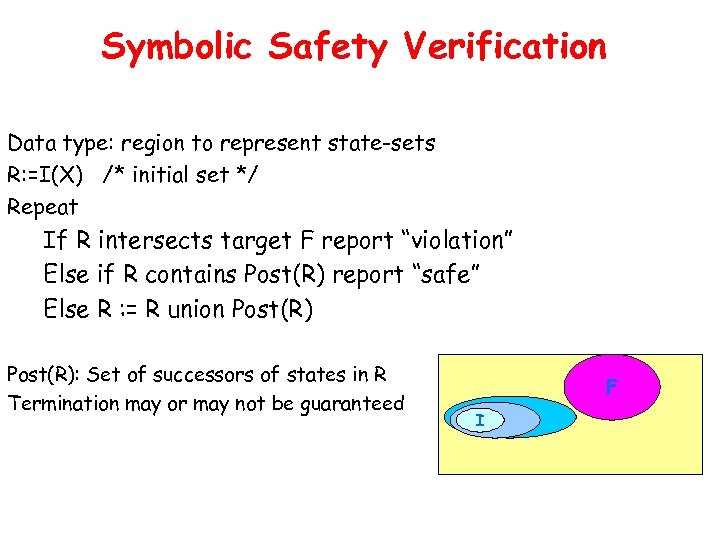

Symbolic Safety Verification Data type: region to represent state-sets R: =I(X) /* initial set */ Repeat If R intersects target F report “violation” Else if R contains Post(R) report “safe” Else R : = R union Post(R): Set of successors of states in R Termination may or may not be guaranteed F I

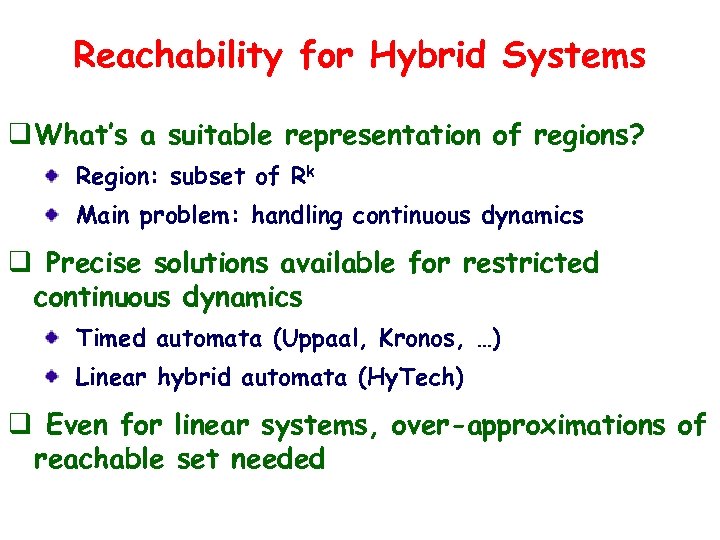

Reachability for Hybrid Systems q What’s a suitable representation of regions? Region: subset of Rk Main problem: handling continuous dynamics q Precise solutions available for restricted continuous dynamics Timed automata (Uppaal, Kronos, …) Linear hybrid automata (Hy. Tech) q Even for linear systems, over-approximations of reachable set needed

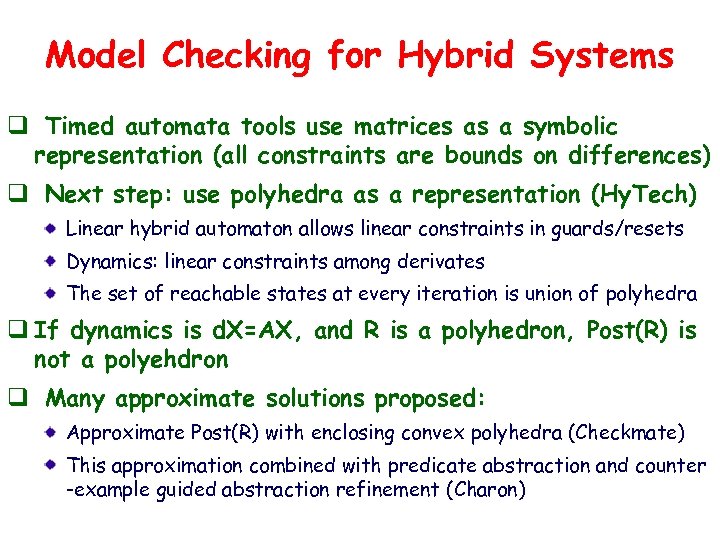

Model Checking for Hybrid Systems q Timed automata tools use matrices as a symbolic representation (all constraints are bounds on differences) q Next step: use polyhedra as a representation (Hy. Tech) Linear hybrid automaton allows linear constraints in guards/resets Dynamics: linear constraints among derivates The set of reachable states at every iteration is union of polyhedra q If dynamics is d. X=AX, and R is a polyhedron, Post(R) is not a polyehdron q Many approximate solutions proposed: Approximate Post(R) with enclosing convex polyhedra (Checkmate) This approximation combined with predicate abstraction and counter -example guided abstraction refinement (Charon)

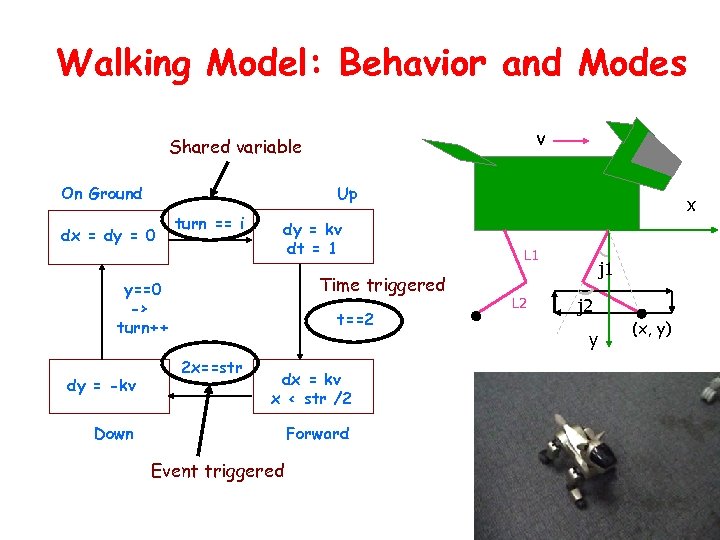

Walking Model: Behavior and Modes v Shared variable On Ground Up dx = dy = 0 turn == i dy = kv dt = 1 Time triggered y==0 -> turn++ dy = -kv t==2 2 x==str dx = kv x < str /2 Down Forward Event triggered x L 1 L 2 j 1 j 2 y (x, y)

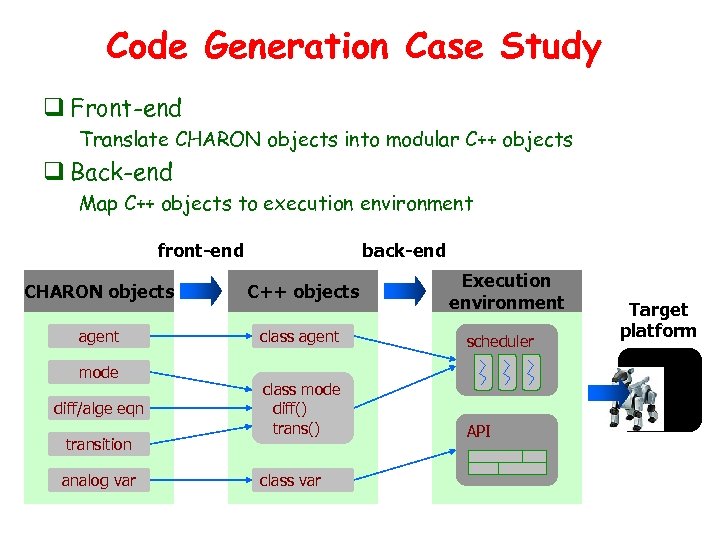

Code Generation Case Study q Front-end Translate CHARON objects into modular C++ objects q Back-end Map C++ objects to execution environment front-end back-end Execution environment CHARON objects C++ objects agent class agent scheduler class mode diff() trans() API mode diff/alge eqn transition analog var class var Target platform

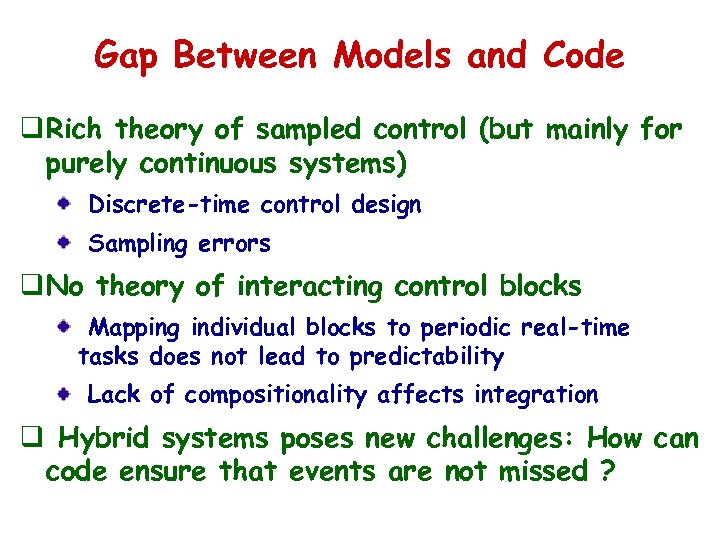

Gap Between Models and Code q Rich theory of sampled control (but mainly for purely continuous systems) Discrete-time control design Sampling errors q No theory of interacting control blocks Mapping individual blocks to periodic real-time tasks does not lead to predictability Lack of compositionality affects integration q Hybrid systems poses new challenges: How can code ensure that events are not missed ?

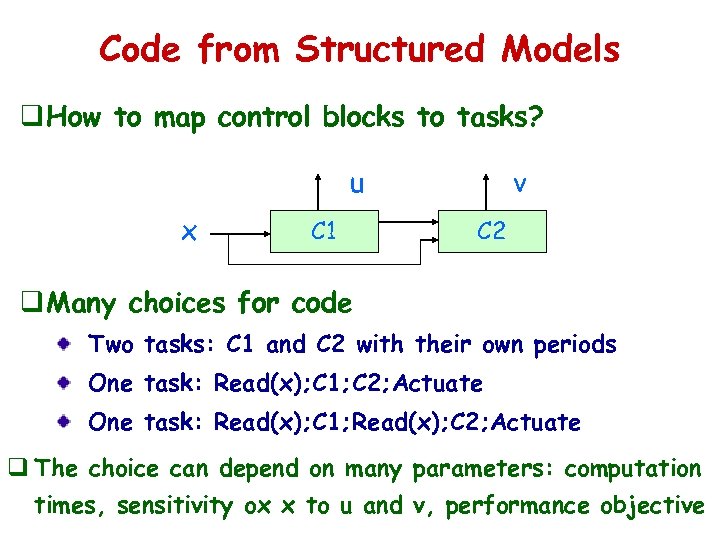

Code from Structured Models q How to map control blocks to tasks? u x C 1 v C 2 q Many choices for code Two tasks: C 1 and C 2 with their own periods One task: Read(x); C 1; C 2; Actuate One task: Read(x); C 1; Read(x); C 2; Actuate q The choice can depend on many parameters: computation times, sensitivity ox x to u and v, performance objective

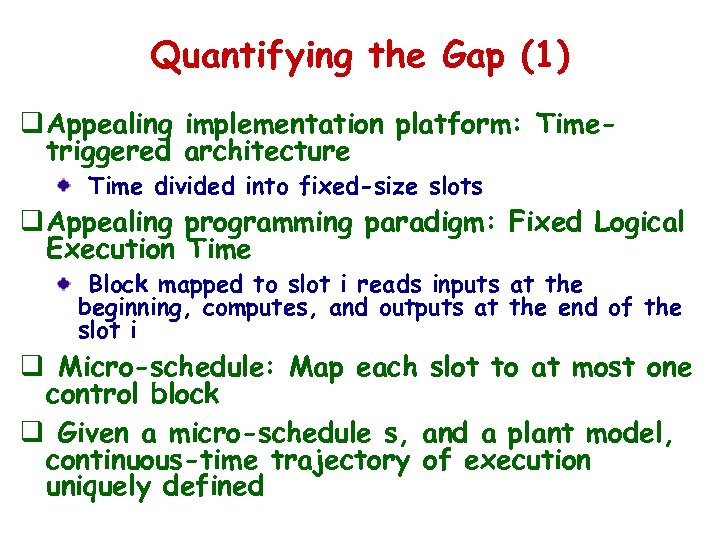

Quantifying the Gap (1) q Appealing implementation platform: Timetriggered architecture Time divided into fixed-size slots q Appealing programming paradigm: Fixed Logical Execution Time Block mapped to slot i reads inputs at the beginning, computes, and outputs at the end of the slot i q Micro-schedule: Map each slot to at most one control block q Given a micro-schedule s, and a plant model, continuous-time trajectory of execution uniquely defined

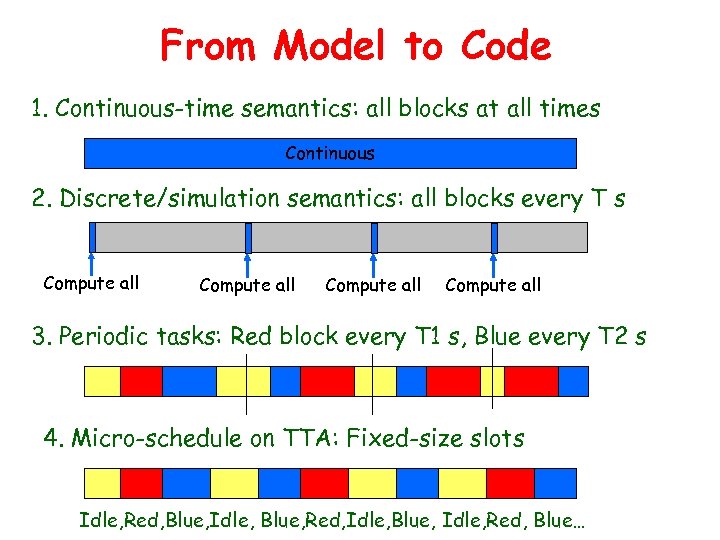

From Model to Code 1. Continuous-time semantics: all blocks at all times Continuous 2. Discrete/simulation semantics: all blocks every T s Compute all 3. Periodic tasks: Red block every T 1 s, Blue every T 2 s 4. Micro-schedule on TTA: Fixed-size slots Idle, Red, Blue, Idle, Blue, Red, Idle, Blue, Idle, Red, Blue…

Quantifying the Gap (2) q Define a performance metric: for two continuous-time trajectories t 1 and t 2, d(t 1, t 2) measures the distance q Quality of a micro-schedule s is d(t*, ts), where t* is the continuous-time simulation trajectory and ts is the trajectory of code when executed according to s q For linear systems, d(t*, ts) is computable when d is, say, L 2 -norm, using ideas from PLTIs (Periodic linear time invariant systems) q This allows comparing micro-schedules by precisely quantifying their metrics

Wrap-Up q Many application domains for hybrid systems q Embedded software: Emerging research area q Current Research: Understanding and quantifying the gap between models and code to add rigor in the code generation step Ongoing: Stochastic hybrid systems q Embedded systems research at Penn: Lee, Pappas, Sokolsky, GRASP lab q Other Research Area: Formal Methods for hardware and software analysis (see talk in 2003 versoin of 996 seminar: Catching bugs in software)

c3d0a3a39dff607ff738b20c7310d87d.ppt