speaking MBA.ppt

- Количество слайдов: 52

PREPARING TO SPEAK

PREPARING TO SPEAK

Homework assignments: 28/11/2014 Prepare a 5 min presentation using PPP, handouts, interactive games and other activities. Topic could be chosen independently.

Homework assignments: 28/11/2014 Prepare a 5 min presentation using PPP, handouts, interactive games and other activities. Topic could be chosen independently.

https: //www. youtube. com/watch? v=k. Vy. Di-iwu. NY https: //www. youtube. com/watch? v=6 f. Y 3 BOcj. Anw

https: //www. youtube. com/watch? v=k. Vy. Di-iwu. NY https: //www. youtube. com/watch? v=6 f. Y 3 BOcj. Anw

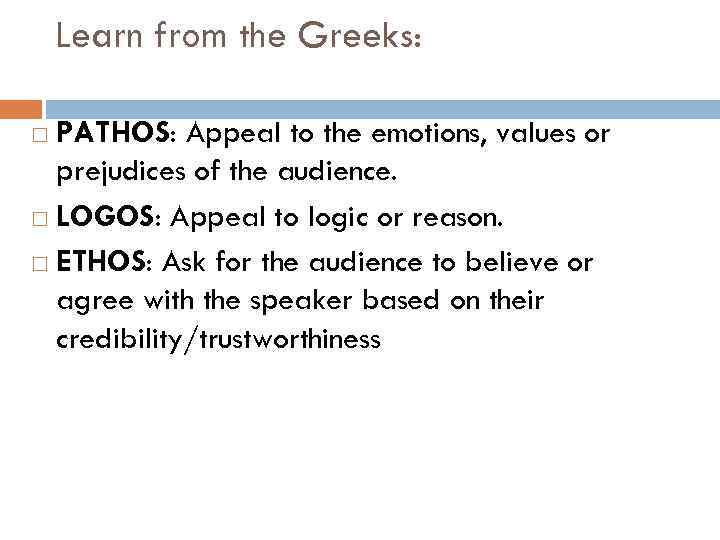

Learn from the Greeks: PATHOS: Appeal to the emotions, values or prejudices of the audience. LOGOS: Appeal to logic or reason. ETHOS: Ask for the audience to believe or agree with the speaker based on their credibility/trustworthiness

Learn from the Greeks: PATHOS: Appeal to the emotions, values or prejudices of the audience. LOGOS: Appeal to logic or reason. ETHOS: Ask for the audience to believe or agree with the speaker based on their credibility/trustworthiness

Exercise: For/Against This public speaking activity encourages flexibility; the ability to see a topic from opposing sides. A speaker has 30 seconds to talk 'for' a topic and then another 30 seconds to speak 'against' it.

Exercise: For/Against This public speaking activity encourages flexibility; the ability to see a topic from opposing sides. A speaker has 30 seconds to talk 'for' a topic and then another 30 seconds to speak 'against' it.

Sample topics: money is the root of all evil a country gets the government it deserves 'green' politics are just the current fashion pets in apartments should be banned marriage is essentially a business contract 'Religion is the opiate of the masses' Karl Marx poverty is a state of mind euthanasia is unjustifiable global warming is media hype cloning animals should be banned animal testing is immoral

Sample topics: money is the root of all evil a country gets the government it deserves 'green' politics are just the current fashion pets in apartments should be banned marriage is essentially a business contract 'Religion is the opiate of the masses' Karl Marx poverty is a state of mind euthanasia is unjustifiable global warming is media hype cloning animals should be banned animal testing is immoral

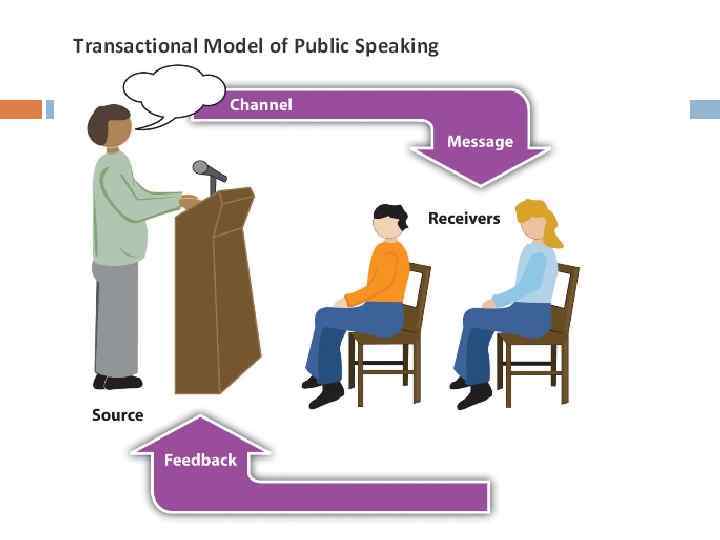

Dialogic Theory of Public Speaking Dialogue is more natural than monologue. Meanings are in people not words. Contexts and social situations impact perceived meanings.

Dialogic Theory of Public Speaking Dialogue is more natural than monologue. Meanings are in people not words. Contexts and social situations impact perceived meanings.

Dialogue vs. Monologue The first tenet/norm of the dialogic perspective is that communication should be a dialogue and not a monologue. Even public speaking situations often turn into dialogues when audience members actively engage speakers by asking questions. Nonverbal behavior (e. g. , nodding one’s head in agreement or scowling) functions as feedback for speakers and contributes to a dialogue.

Dialogue vs. Monologue The first tenet/norm of the dialogic perspective is that communication should be a dialogue and not a monologue. Even public speaking situations often turn into dialogues when audience members actively engage speakers by asking questions. Nonverbal behavior (e. g. , nodding one’s head in agreement or scowling) functions as feedback for speakers and contributes to a dialogue.

Meanings Are in People, Not Words You and your audience may differ in how you see your speech The meanings of words must be mutually agreed upon by people interacting with each other. If you say the word “dog” and think of a soft, furry pet and your audience member thinks of the animal that attacked him as a child, the two of you perceive the word from very different vantage points. We must know quite a bit about our audience so we can make language choices that will be the most appropriate for the context

Meanings Are in People, Not Words You and your audience may differ in how you see your speech The meanings of words must be mutually agreed upon by people interacting with each other. If you say the word “dog” and think of a soft, furry pet and your audience member thinks of the animal that attacked him as a child, the two of you perceive the word from very different vantage points. We must know quite a bit about our audience so we can make language choices that will be the most appropriate for the context

Contexts and Social Situations Human interactions take place according to cultural norms and rules https: //www. youtube. com/watch? v=FG 0 -z. Ego. S_Y Considering the context of a public speech involves thinking about De. Vito’s four dimensions : o physical, o temporal, o social-psychological, and o cultural

Contexts and Social Situations Human interactions take place according to cultural norms and rules https: //www. youtube. com/watch? v=FG 0 -z. Ego. S_Y Considering the context of a public speech involves thinking about De. Vito’s four dimensions : o physical, o temporal, o social-psychological, and o cultural

Physical Dimension For example, you may find yourself speaking in a classroom, a corporate board room, or a large amphitheater. Each of these real environments will influence your ability to interact with your audience. Larger physical spaces may require you to use a microphone and speaker system to make yourself heard or to use projected presentation aids to convey visual material.

Physical Dimension For example, you may find yourself speaking in a classroom, a corporate board room, or a large amphitheater. Each of these real environments will influence your ability to interact with your audience. Larger physical spaces may require you to use a microphone and speaker system to make yourself heard or to use projected presentation aids to convey visual material.

Temporal Dimension The time of day can have a dramatic effect on how alert one’s audience is. Don’t believe us? Try giving a speech in front of a class around 12: 30 p. m. when no one’s had lunch. We often face temporal dimensions related to how our speech will be viewed in light of societal events. Imagine how a speech on the importance of campus security would be interpreted on the day after a shooting occurred.

Temporal Dimension The time of day can have a dramatic effect on how alert one’s audience is. Don’t believe us? Try giving a speech in front of a class around 12: 30 p. m. when no one’s had lunch. We often face temporal dimensions related to how our speech will be viewed in light of societal events. Imagine how a speech on the importance of campus security would be interpreted on the day after a shooting occurred.

Social-Psychological Dimension The social-psychological dimension of context refers to “status relationships among participants, roles and games that people play, norms of the society or group, and the friendliness, formality, or gravity of the situation. ” You have to know the types of people in your audience and how they react to a wide range of messages.

Social-Psychological Dimension The social-psychological dimension of context refers to “status relationships among participants, roles and games that people play, norms of the society or group, and the friendliness, formality, or gravity of the situation. ” You have to know the types of people in your audience and how they react to a wide range of messages.

Cultural Dimension When we interact with others from different cultures, misunderstandings can result from differing cultural beliefs, norms, and practices. As public speakers engaging in a dialogue with our audience members, we must attempt to understand the cultural makeup of our audience so that we can avoid these misunderstandings as much as possible.

Cultural Dimension When we interact with others from different cultures, misunderstandings can result from differing cultural beliefs, norms, and practices. As public speakers engaging in a dialogue with our audience members, we must attempt to understand the cultural makeup of our audience so that we can avoid these misunderstandings as much as possible.

Discussion When thinking about your first speech in class, explain the context of your speech using De. Vito’s four dimensions: physical, temporal, social-psychological, and cultural. How might you address challenges posed by each of these four dimensions?

Discussion When thinking about your first speech in class, explain the context of your speech using De. Vito’s four dimensions: physical, temporal, social-psychological, and cultural. How might you address challenges posed by each of these four dimensions?

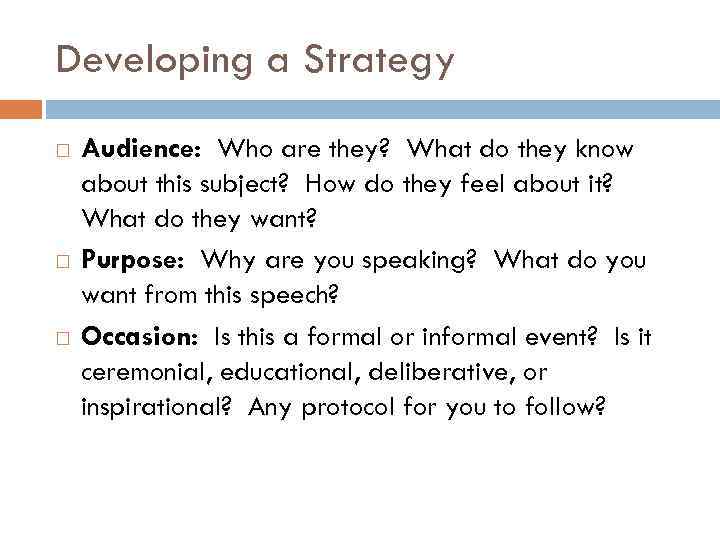

Developing a Strategy Audience: Who are they? What do they know about this subject? How do they feel about it? What do they want? Purpose: Why are you speaking? What do you want from this speech? Occasion: Is this a formal or informal event? Is it ceremonial, educational, deliberative, or inspirational? Any protocol for you to follow?

Developing a Strategy Audience: Who are they? What do they know about this subject? How do they feel about it? What do they want? Purpose: Why are you speaking? What do you want from this speech? Occasion: Is this a formal or informal event? Is it ceremonial, educational, deliberative, or inspirational? Any protocol for you to follow?

What Makes People Listen? Self-interest. Who's telling it. How it's told.

What Makes People Listen? Self-interest. Who's telling it. How it's told.

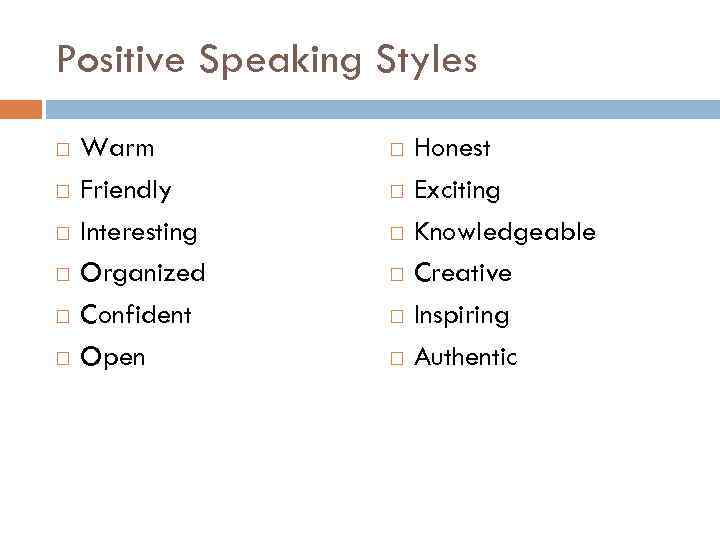

Positive Speaking Styles Warm Friendly Interesting Organized Confident Open Honest Exciting Knowledgeable Creative Inspiring Authentic

Positive Speaking Styles Warm Friendly Interesting Organized Confident Open Honest Exciting Knowledgeable Creative Inspiring Authentic

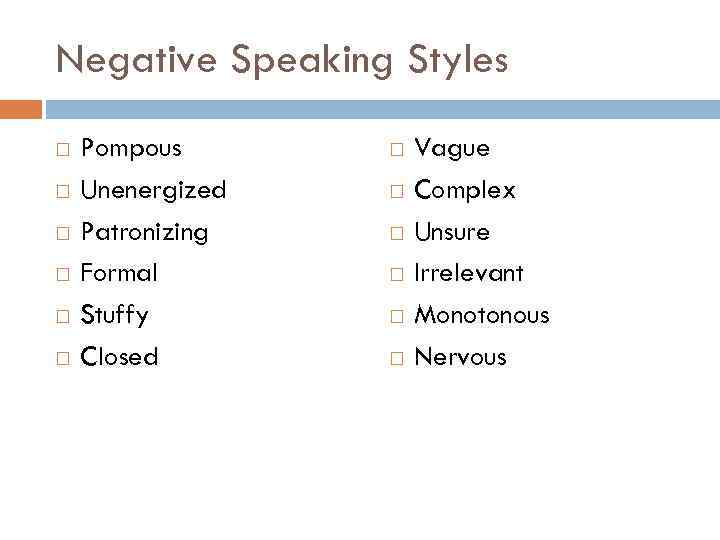

Negative Speaking Styles Pompous Unenergized Patronizing Formal Stuffy Closed Vague Complex Unsure Irrelevant Monotonous Nervous

Negative Speaking Styles Pompous Unenergized Patronizing Formal Stuffy Closed Vague Complex Unsure Irrelevant Monotonous Nervous

Questions Listeners Will Bring to Just About Any Listening Situation Do you know what I need to know? Can I trust you? Am I comfortable with you? How can you affect me? What's my experience with you? Are you reasonable?

Questions Listeners Will Bring to Just About Any Listening Situation Do you know what I need to know? Can I trust you? Am I comfortable with you? How can you affect me? What's my experience with you? Are you reasonable?

Five Common Obstacles to Effective Communication Stereotypes Prejudice Feelings Language Culture

Five Common Obstacles to Effective Communication Stereotypes Prejudice Feelings Language Culture

When People Feel Threatened, Intimidated, Lost or Confused. . . They stop listening. They discover how much they don't know. They become frustrated. They may become angry, hostile. They may withdraw entirely.

When People Feel Threatened, Intimidated, Lost or Confused. . . They stop listening. They discover how much they don't know. They become frustrated. They may become angry, hostile. They may withdraw entirely.

Myths about Communication Apprehension People who suffer from speaking anxiety are neurotic. Speaking anxiety is a normal reaction. Good speakers can get nervous just as poor speakers do. Winston Churchill, for example, would get physically ill before major speeches in Parliament. Telling a joke or two is always a good way to begin a speech. Humor is some of the toughest material to deliver effectively because it requires an exquisite sense of timing.

Myths about Communication Apprehension People who suffer from speaking anxiety are neurotic. Speaking anxiety is a normal reaction. Good speakers can get nervous just as poor speakers do. Winston Churchill, for example, would get physically ill before major speeches in Parliament. Telling a joke or two is always a good way to begin a speech. Humor is some of the toughest material to deliver effectively because it requires an exquisite sense of timing.

Example of a not appropriate joke for the international event On the roof of a very tall building are four men; one is asian, one is mexican, one is black, and the last one is white. The asian walks to the ledge and says, "This is for all my people" and jumps off the roof. Next, the mexican walks to the ledge and also says, "This is for all my people" and then he jumps off the roof. Next is the black guy's turn. The black guy walks to the ledge and says, "This is for all my people" and then throws the white guy off the roof.

Example of a not appropriate joke for the international event On the roof of a very tall building are four men; one is asian, one is mexican, one is black, and the last one is white. The asian walks to the ledge and says, "This is for all my people" and jumps off the roof. Next, the mexican walks to the ledge and also says, "This is for all my people" and then he jumps off the roof. Next is the black guy's turn. The black guy walks to the ledge and says, "This is for all my people" and then throws the white guy off the roof.

Myths about Communication Apprehension Imagine the audience is naked. This tip just plain doesn’t work because imagining the audience naked will do nothing to calm your nerves. As Malcolm Kushner noted (America's Favorite Humor Consultant ), “There are some folks in the audience I wouldn’t want to see naked—especially if I’m trying not to be frightened. ” Any mistake means that you have “blown it. ” We all make mistakes. What matters is not whether we make a mistake but how well we recover. A speech does not have to be perfect.

Myths about Communication Apprehension Imagine the audience is naked. This tip just plain doesn’t work because imagining the audience naked will do nothing to calm your nerves. As Malcolm Kushner noted (America's Favorite Humor Consultant ), “There are some folks in the audience I wouldn’t want to see naked—especially if I’m trying not to be frightened. ” Any mistake means that you have “blown it. ” We all make mistakes. What matters is not whether we make a mistake but how well we recover. A speech does not have to be perfect.

Myths about Communication Apprehension Avoid speaking anxiety by writing your speech out word for word and memorizing it. Instead of remembering three to five main points and subpoints, you will try to commit to memory more than a thousand bits of data. Audiences are out to get you. With only a few exceptions, the natural state of audiences is empathy, not antipathy.

Myths about Communication Apprehension Avoid speaking anxiety by writing your speech out word for word and memorizing it. Instead of remembering three to five main points and subpoints, you will try to commit to memory more than a thousand bits of data. Audiences are out to get you. With only a few exceptions, the natural state of audiences is empathy, not antipathy.

Myths about Communication Apprehension You will look to the audience as nervous as you feel. Empirical research has shown that audiences do not perceive the level of nervousness that speakers report feeling. A little nervousness helps you give a better speech. This “myth” is true!

Myths about Communication Apprehension You will look to the audience as nervous as you feel. Empirical research has shown that audiences do not perceive the level of nervousness that speakers report feeling. A little nervousness helps you give a better speech. This “myth” is true!

Discussion With a partner or in a small group, discuss which myths create the biggest problems for public speakers. Why do people believe in these myths?

Discussion With a partner or in a small group, discuss which myths create the biggest problems for public speakers. Why do people believe in these myths?

Reducing Communication Apprehension 1. 2. 3. 4. 5. 6. 7. Indicators of physiological stress at different milestones in the process: expectation (the minute prior to starting the speech), confrontation (the first minute of the speech), adaptation (the last minute of the speech), and release (the minute immediately following the end of the speech). Reducing Anxiety through Preparation Analyze Your Audience Clearly Organize Your Ideas Adapt Your Language to the Oral Mode Practice in Conditions Similar to Those You Will Face When Speaking Watch What You Eat

Reducing Communication Apprehension 1. 2. 3. 4. 5. 6. 7. Indicators of physiological stress at different milestones in the process: expectation (the minute prior to starting the speech), confrontation (the first minute of the speech), adaptation (the last minute of the speech), and release (the minute immediately following the end of the speech). Reducing Anxiety through Preparation Analyze Your Audience Clearly Organize Your Ideas Adapt Your Language to the Oral Mode Practice in Conditions Similar to Those You Will Face When Speaking Watch What You Eat

Diction exercises The speakers repeat the tongue twister responding to the conductor's direction. He/she can make them go faster or slower, louder or quieter. The goal of the exercise is to practice articulation coupled with vocal variety that is speech rate and volume. 2. Модификатор модифицировал, да не выдемодифицировал. Взбиваем сливки, Сливаем взбивки. 3. Шел Шура по шоссе и шуршал ногами. 1. 4. 5. 6. Five flippant Frenchmen fly from France for fashions Kiss her quick, kiss her quicker, kiss her quickest. Six thick thistle sticks

Diction exercises The speakers repeat the tongue twister responding to the conductor's direction. He/she can make them go faster or slower, louder or quieter. The goal of the exercise is to practice articulation coupled with vocal variety that is speech rate and volume. 2. Модификатор модифицировал, да не выдемодифицировал. Взбиваем сливки, Сливаем взбивки. 3. Шел Шура по шоссе и шуршал ногами. 1. 4. 5. 6. Five flippant Frenchmen fly from France for fashions Kiss her quick, kiss her quicker, kiss her quickest. Six thick thistle sticks

Reducing Nervousness during Delivery Anticipate the Reactions of Your Body Focus on the Audience, Not on Yourself Maintain Your Sense of Humor Stress Management Techniques

Reducing Nervousness during Delivery Anticipate the Reactions of Your Body Focus on the Audience, Not on Yourself Maintain Your Sense of Humor Stress Management Techniques

Coping with the Unexpected Speech Content Issues Technical Difficulties External Distractions

Coping with the Unexpected Speech Content Issues Technical Difficulties External Distractions

Do You Need Visuals? Visual support will explain, reinforce, clarify. Perhaps you can't say it easily, but you may be able to show it. Some people are visual-attenders, others are aural -attenders. Don’t leave anyone out. Say it to them, show it to them, and tell them where to find more.

Do You Need Visuals? Visual support will explain, reinforce, clarify. Perhaps you can't say it easily, but you may be able to show it. Some people are visual-attenders, others are aural -attenders. Don’t leave anyone out. Say it to them, show it to them, and tell them where to find more.

When Do Visuals Work Best? New data. Complex, technical information. New context. Numbers, facts, quotes, lists. Comparisons. Geographical or spatial patterns.

When Do Visuals Work Best? New data. Complex, technical information. New context. Numbers, facts, quotes, lists. Comparisons. Geographical or spatial patterns.

Good Visuals Will. . . Be simple in nature. Explain relationships. Use color effectively. Be easy to set up, display and transport. Reinforce the spoken message.

Good Visuals Will. . . Be simple in nature. Explain relationships. Use color effectively. Be easy to set up, display and transport. Reinforce the spoken message.

Four Modes of Expression Manuscripted. Memorized. Extemporaneous/improvisation.

Four Modes of Expression Manuscripted. Memorized. Extemporaneous/improvisation.

If You Use Notes, They Must Be. . . Simple. Compact. Easy-to-follow. Easy-to-handle. Numbered. Readable.

If You Use Notes, They Must Be. . . Simple. Compact. Easy-to-follow. Easy-to-handle. Numbered. Readable.

What Else Should You Do? Move from the familiar to the unfamiliar. Talk process first, then detail. Tell them where this speech is going. Visualize and demonstrate. Use interim summaries, transitions.

What Else Should You Do? Move from the familiar to the unfamiliar. Talk process first, then detail. Tell them where this speech is going. Visualize and demonstrate. Use interim summaries, transitions.

Anything Else? Give examples. Humanize and personalize. Tell stories. Dramatize. Use yourself, involve them.

Anything Else? Give examples. Humanize and personalize. Tell stories. Dramatize. Use yourself, involve them.

Finally, The Checklist Date, time, location. Microphone & acoustics. Stage. Lectern. Lights. Room layout. Visual-aids. Time limits. Notes. Try it out.

Finally, The Checklist Date, time, location. Microphone & acoustics. Stage. Lectern. Lights. Room layout. Visual-aids. Time limits. Notes. Try it out.

EXAMPLE OF INFORMATIVE SPEECH OUTLINE

EXAMPLE OF INFORMATIVE SPEECH OUTLINE

Techniques of Informative Speaking Informative Purpose Statement Precedes a thesis statement In one sentence asks: What is your speech going to do? What will the audience walk away with?

Techniques of Informative Speaking Informative Purpose Statement Precedes a thesis statement In one sentence asks: What is your speech going to do? What will the audience walk away with?

Techniques of Informative Speaking Informative Purpose Statement Precedes a thesis statement In one sentence asks: What is your speech going to do? What will the audience walk away with?

Techniques of Informative Speaking Informative Purpose Statement Precedes a thesis statement In one sentence asks: What is your speech going to do? What will the audience walk away with?

Techniques of Informative Speaking, cont. Make it easy to listen Watch for information overload Choose Use 3 to 5 main ideas information and examples that connect to the audience Use simple information and build up to complex ideas

Techniques of Informative Speaking, cont. Make it easy to listen Watch for information overload Choose Use 3 to 5 main ideas information and examples that connect to the audience Use simple information and build up to complex ideas

Techniques of Informative Speaking, cont. Emphasize important points Repetition Rewording Signposts of important points Words or phrases that emphasize the importance of what you are about to say

Techniques of Informative Speaking, cont. Emphasize important points Repetition Rewording Signposts of important points Words or phrases that emphasize the importance of what you are about to say

Techniques of Informative Speaking, cont. Make the message clear Be aware of what you intend to communicate Would this message sound clear to you if you heard if for the first time?

Techniques of Informative Speaking, cont. Make the message clear Be aware of what you intend to communicate Would this message sound clear to you if you heard if for the first time?

Techniques of Informative Speaking, cont. Make the presentation interesting Relate to your listeners interests Create interesting presentation aids Use humor to make a point Make yourself the butt of the joke Use humorous quotations

Techniques of Informative Speaking, cont. Make the presentation interesting Relate to your listeners interests Create interesting presentation aids Use humor to make a point Make yourself the butt of the joke Use humorous quotations

Knowing your audience is essential to an effective persuasive speech

Knowing your audience is essential to an effective persuasive speech

Exercise PERSUASIVE SPEAKING

Exercise PERSUASIVE SPEAKING