ef1455945ed0517a8d07e4c9224932fe.ppt

- Количество слайдов: 124

Practice Problem: Chapter 2 #6 The rent control agency of NYC has found that aggregate demand is QD = 160 -8 P. Quantity is measured in tens of thousands of apartments. Price, the average monthly rental rate, is measured in hundreds of dollars. The agency also noted that the increase in Q at lower P results from more three-person families coming into the city and demanding apartments. The city’s board of realtors acknowledges that this is a good demand estimate and has shown that supply is QS = 70+7 P. What is the free market price? What is the change in city population if the agency sets a maximum average monthly rent of $300 and all those who cannot find an apartment leave the city?

Chapter 2 #3 l Set quantity supply = quantity demand l P = 6 (convert to $600) l Q = 112 (convert to 1, 120, 000) © 2005 Pearson Education, Inc. Chapter 3 2

Chapter 2: #6 l If the rent control agency sets the rental rate at $300, the quantity supplied would then be 910, 000 (QS = 70 + (7)(3) = 91), a decrease of 210, 000 apartments from the free market equilibrium. (Assuming three people per family per apartment, this would imply a loss of 630, 000 people. ) At the $300 rental rate, the demand for apartments is 1, 360, 000 units, and the resulting shortage is 450, 000 units (1, 360, 000 -910, 000). However, excess demand (supply shortages) and lower quantity demanded are not the same concepts. The supply shortage means that the market cannot accommodate the new people who would have been willing to move into the city at the new lower price. Therefore, the city population will only fall by 630, 000, which is represented by the drop in the number of actual apartments from 1, 120, 000 (the old equilibrium value) to 910, 000, or 210, 000 apartments with 3 people each. © 2005 Pearson Education, Inc. Chapter 3 3

Practice Problem l Suppose the agency bows to the wishes of the board and sets a rental of $900 per month on all apartments to allow landlords a “fair” rate of return. If 50 percent of any increases in apartment offerings come from new construction, how many apartments are constructed? © 2005 Pearson Education, Inc. Chapter 3 4

Answer: l At a rental rate of $900, the supply of apartments would be 70 + 7(9) = 133, or 1, 330, 000 units, which is an increase of 210, 000 units over the free market equilibrium. Therefore, (0. 5)(210, 000) = 105, 000 units would be constructed. Note, however, that since demand is only 880, 000 units, 450, 000 units would go unrented © 2005 Pearson Education, Inc. Chapter 3 5

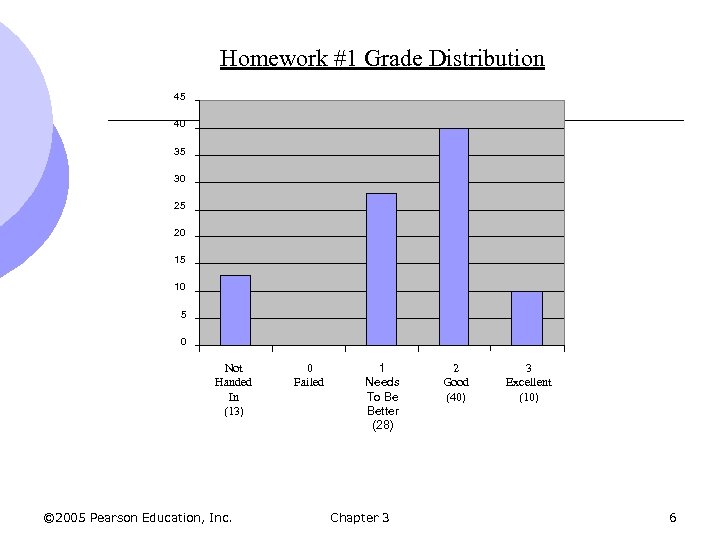

Homework #1 Grade Distribution 45 40 35 30 25 20 15 10 5 0 Not Handed In (13) © 2005 Pearson Education, Inc. 0 Failed 1 Needs To Be Better (28) Chapter 3 2 Good (40) 3 Excellent (10) 6

Chapter 3 Consumer Behavior

Introduction l How are consumer preferences used to determine demand? l How do consumers allocate income to the purchase of different goods? © 2005 Pearson Education, Inc. Chapter 3 8

Consumer Behavior Applications 1. How would General Mills determine the price to charge for a new cereal before it went to the market? 2. To what extent did the food stamp program provide individuals with more food versus merely subsidizing food they bought anyway? © 2005 Pearson Education, Inc. Chapter 3 9

Consumer Behavior Theory l There are three steps involved in the study of consumer behavior 1. Consumer Preferences m To describe how and why people prefer one good to another: algebra and graphs 2. Budget Constraints m People have limited incomes/face prices © 2005 Pearson Education, Inc. Chapter 3 10

Consumer Behavior 3. Consumer Choices m What combination of goods will consumers buy to maximize their satisfaction, given preferences, income and prices? © 2005 Pearson Education, Inc. Chapter 3 11

Consumer Preferences l How might a consumer compare different groups of items available for purchase? l A market basket is a collection of one or more commodities l Individuals can choose between market baskets containing different goods © 2005 Pearson Education, Inc. Chapter 3 12

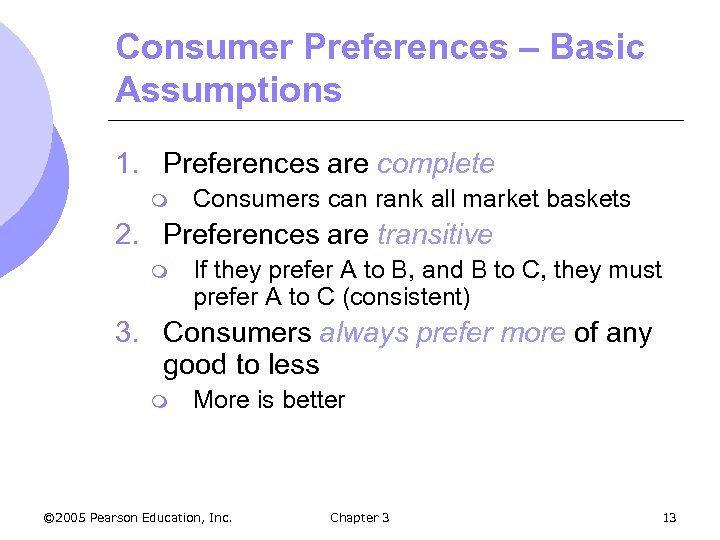

Consumer Preferences – Basic Assumptions 1. Preferences are complete m Consumers can rank all market baskets 2. Preferences are transitive m If they prefer A to B, and B to C, they must prefer A to C (consistent) 3. Consumers always prefer more of any good to less m More is better © 2005 Pearson Education, Inc. Chapter 3 13

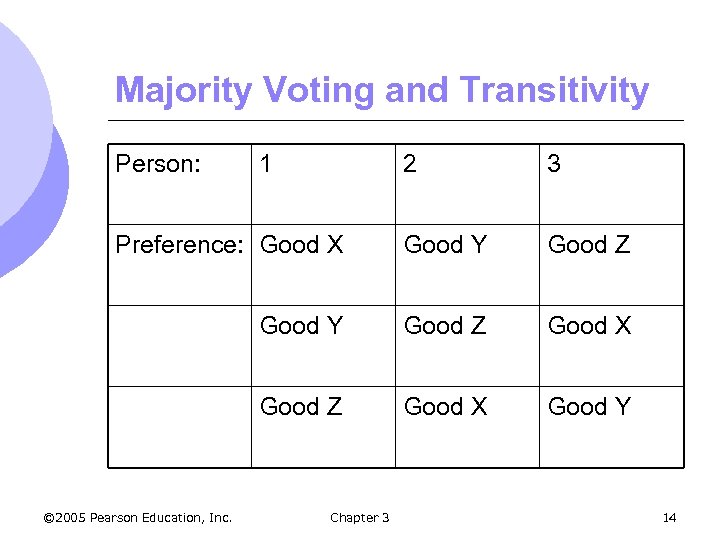

Majority Voting and Transitivity Person: 2 3 Preference: Good X Good Y Good Z Good X Good Y © 2005 Pearson Education, Inc. 1 Chapter 3 14

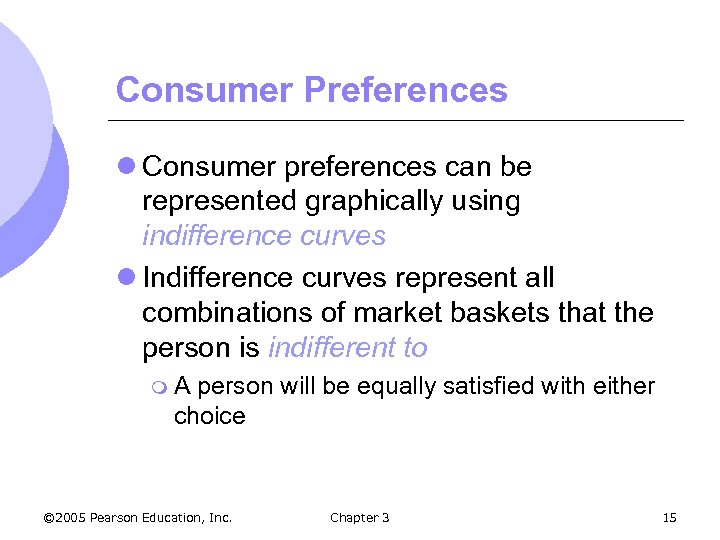

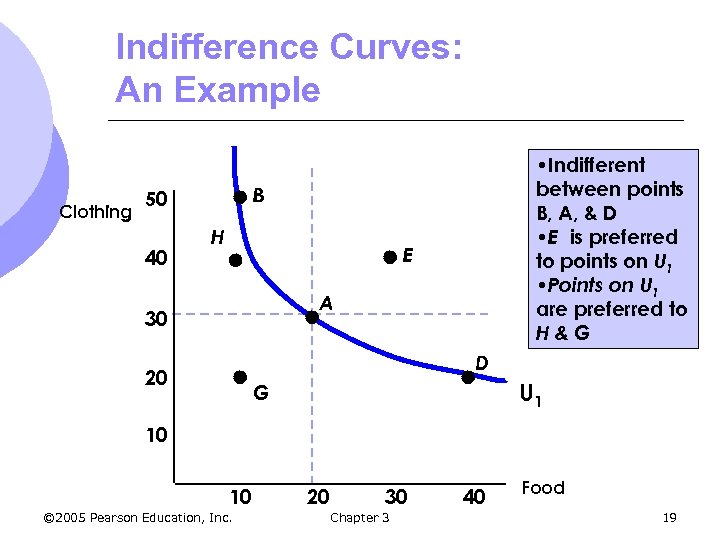

Consumer Preferences l Consumer preferences can be represented graphically using indifference curves l Indifference curves represent all combinations of market baskets that the person is indifferent to m. A person will be equally satisfied with either choice © 2005 Pearson Education, Inc. Chapter 3 15

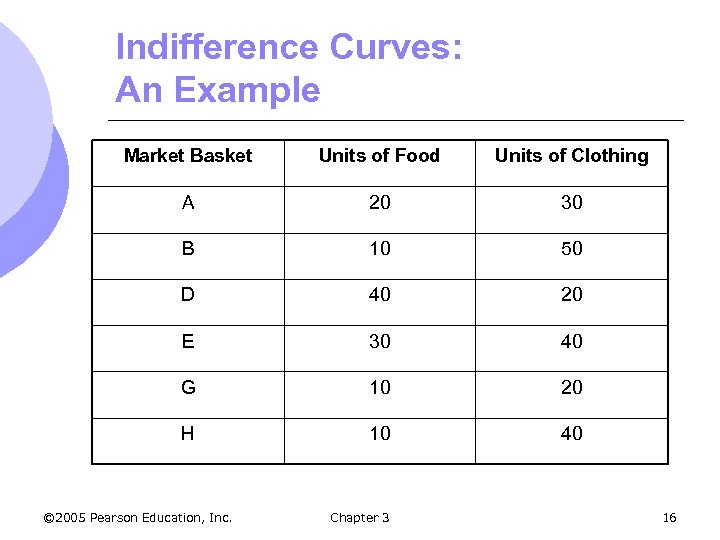

Indifference Curves: An Example Market Basket Units of Food Units of Clothing A 20 30 B 10 50 D 40 20 E 30 40 G 10 20 H 10 40 © 2005 Pearson Education, Inc. Chapter 3 16

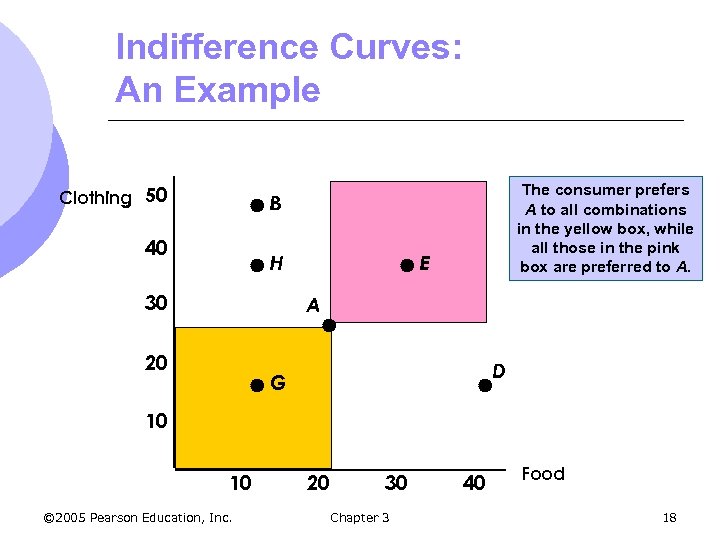

Indifference Curves: An Example l Graph the points with one good on the xaxis and one good on the y-axis l Plotting the points, we can make some immediate observations about preferences m More © 2005 Pearson Education, Inc. is better Chapter 3 17

Indifference Curves: An Example Clothing 50 The consumer prefers A to all combinations in the yellow box, while all those in the pink box are preferred to A. B 40 H 30 E A 20 D G 10 10 © 2005 Pearson Education, Inc. 20 30 Chapter 3 40 Food 18

Indifference Curves: An Example Clothing B 50 40 • Indifferent between points B, A, & D • E is preferred to points on U 1 • Points on U 1 are preferred to H&G H E A 30 D 20 U 1 G 10 10 © 2005 Pearson Education, Inc. 20 30 Chapter 3 40 Food 19

Indifference Curves l Indifference curves slope downward to the right m If they sloped upward, they would violate the assumption that more is preferred to less l Some points that had more of both goods would be indifferent to a basket with less of both goods © 2005 Pearson Education, Inc. Chapter 3 20

Indifference Curves l To describe preferences for all combinations of goods/services, we have a set of indifference curves – an indifference map m Each indifference curve in the map shows the market baskets among which the person is indifferent © 2005 Pearson Education, Inc. Chapter 3 21

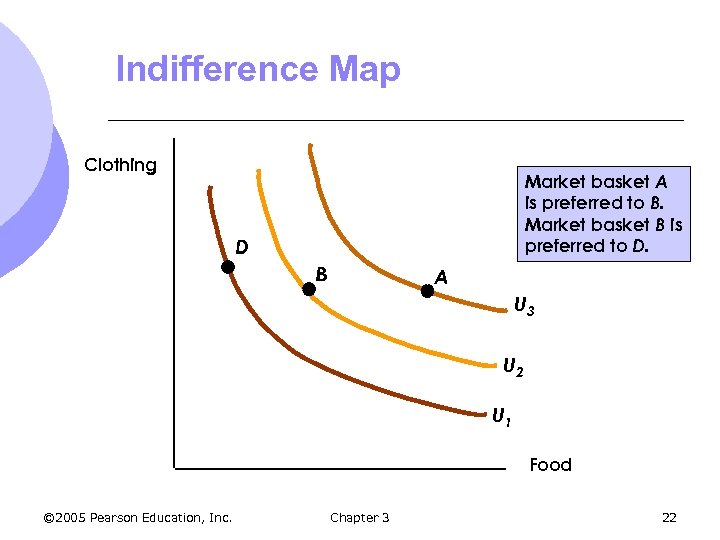

Indifference Map Clothing Market basket A is preferred to B. Market basket B is preferred to D. D B A U 3 U 2 U 1 Food © 2005 Pearson Education, Inc. Chapter 3 22

Indifference Maps l Indifference maps give more information about shapes of indifference curves m Indifference l Violates m Why? © 2005 Pearson Education, Inc. curves cannot cross assumption that more is better What if we assume they can cross? Chapter 3 23

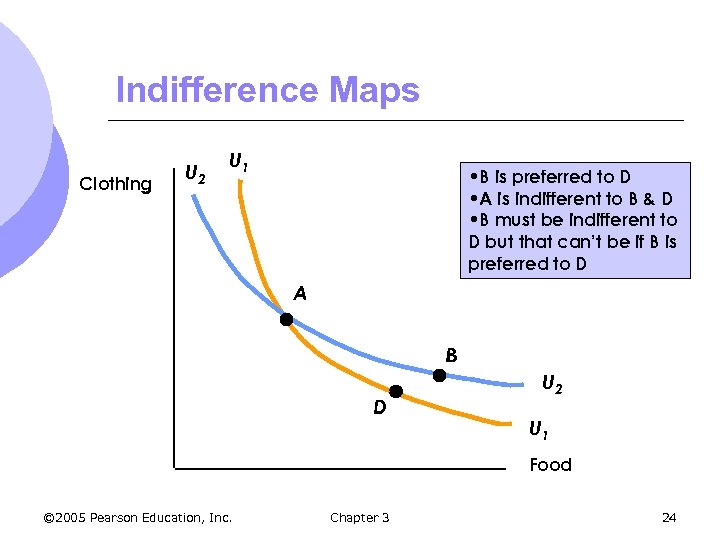

Indifference Maps Clothing U 2 U 1 • B is preferred to D • A is indifferent to B & D • B must be indifferent to D but that can’t be if B is preferred to D A B D U 2 U 1 Food © 2005 Pearson Education, Inc. Chapter 3 24

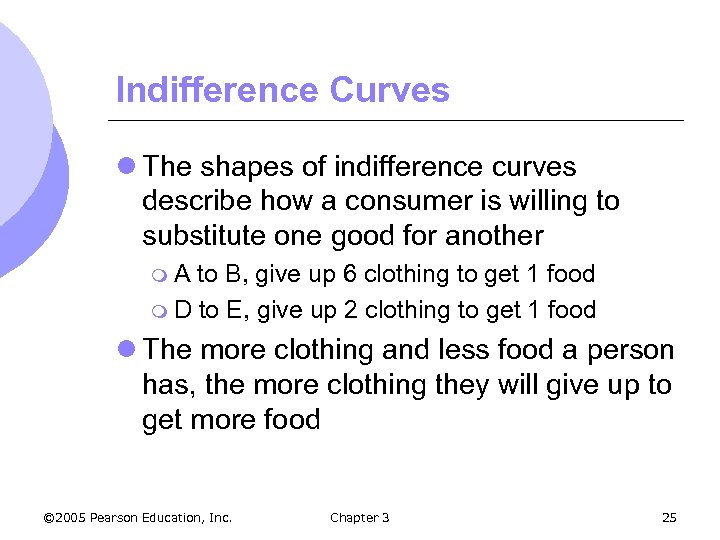

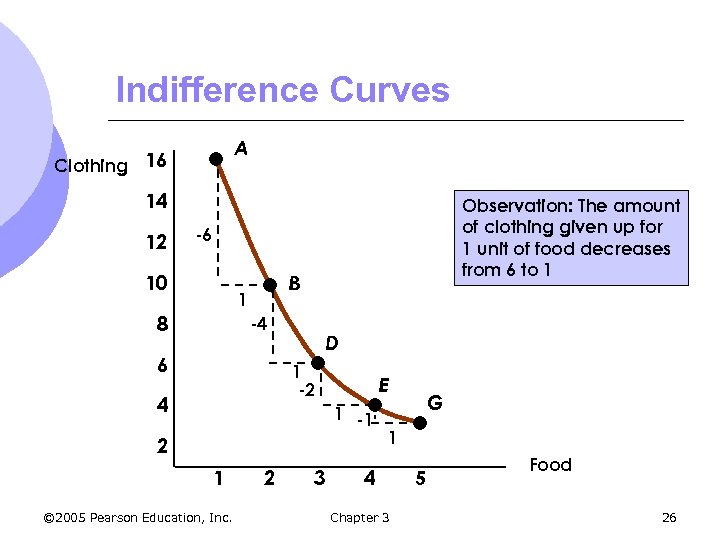

Indifference Curves l The shapes of indifference curves describe how a consumer is willing to substitute one good for another m. A to B, give up 6 clothing to get 1 food m D to E, give up 2 clothing to get 1 food l The more clothing and less food a person has, the more clothing they will give up to get more food © 2005 Pearson Education, Inc. Chapter 3 25

Indifference Curves A Clothing 16 14 12 Observation: The amount of clothing given up for 1 unit of food decreases from 6 to 1 -6 10 B 1 8 -4 6 D 1 -2 4 E 1 -1 2 1 © 2005 Pearson Education, Inc. 2 3 G 1 4 Chapter 3 5 Food 26

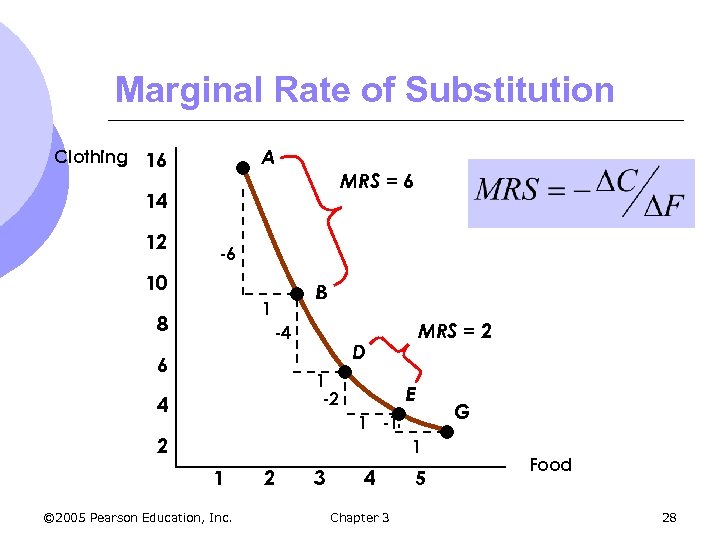

Indifference Curves l We measure how a person trades one good for another using the marginal rate of substitution (MRS) m It quantifies the amount of one good a consumer will give up to obtain more of another good m It is measured by the slope of the indifference curve © 2005 Pearson Education, Inc. Chapter 3 27

Marginal Rate of Substitution A Clothing 16 MRS = 6 14 12 -6 10 B 1 8 -4 6 D 1 -2 4 MRS = 2 E 1 -1 2 1 1 © 2005 Pearson Education, Inc. 2 3 4 Chapter 3 5 G Food 28

Marginal Rate of Substitution l Indifference curves are convex (bowed inward) m As more of one good is consumed, a consumer would prefer to give up fewer units of a second good to get additional units of the first one l Consumers generally prefer a balanced market basket © 2005 Pearson Education, Inc. Chapter 3 29

Marginal Rate of Substitution l The MRS decreases as we move down the indifference curve m Along an indifference curve there is a diminishing marginal rate of substitution. m The MRS went from 6 to 4 to 1 © 2005 Pearson Education, Inc. Chapter 3 30

Marginal Rate of Substitution l Indifference curves with different shapes imply a different willingness to substitute l Two polar cases are of interest m Perfect substitutes m Perfect complements © 2005 Pearson Education, Inc. Chapter 3 31

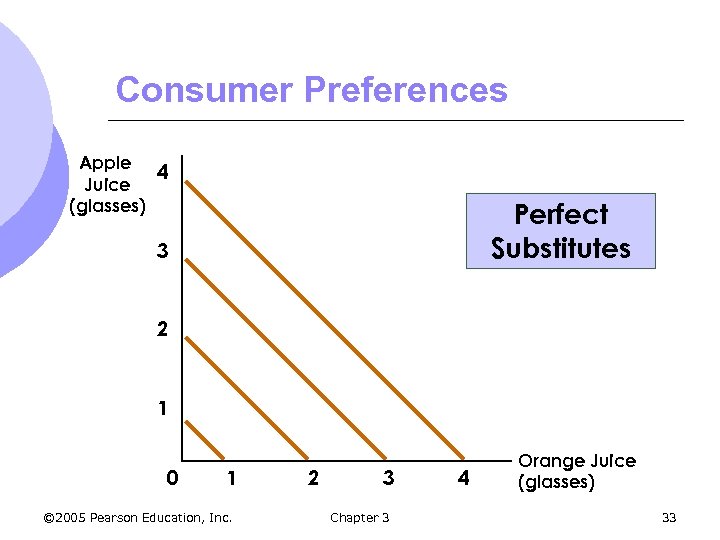

Marginal Rate of Substitution l Perfect Substitutes m Two goods are perfect substitutes when the marginal rate of substitution of one good for the other is constant m Example: a person might consider apple juice and orange juice perfect substitutes l They would always trade 1 glass of OJ for 1 glass of Apple Juice © 2005 Pearson Education, Inc. Chapter 3 32

Consumer Preferences Apple 4 Juice (glasses) Perfect Substitutes 3 2 1 0 1 © 2005 Pearson Education, Inc. 2 3 Chapter 3 4 Orange Juice (glasses) 33

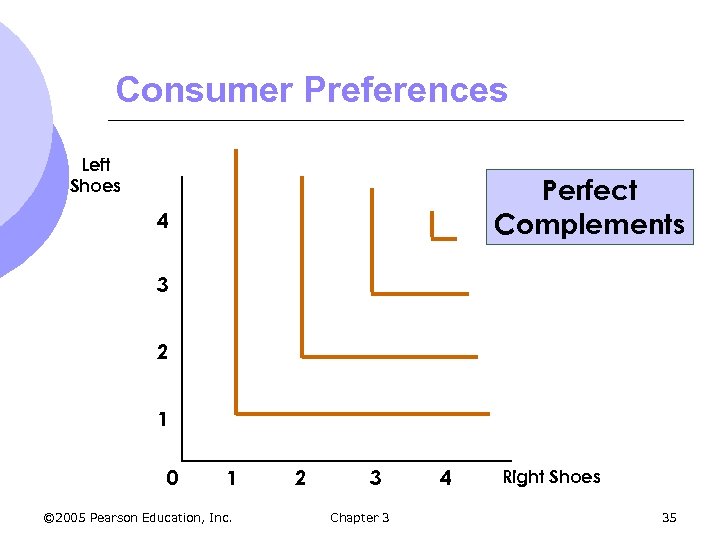

Consumer Preferences l Perfect Complements m Two goods are perfect complements when the indifference curves for the goods are shaped as right angles m Example: If you have 1 left shoe and 1 right shoe, you are indifferent between having more left shoes only l Must © 2005 Pearson Education, Inc. have one right for one left Chapter 3 34

Consumer Preferences Left Shoes Perfect Complements 4 3 2 1 0 1 © 2005 Pearson Education, Inc. 2 3 Chapter 3 4 Right Shoes 35

Consumer Preferences l We have assumed all our commodities are “goods” l There are commodities we don’t want more of - bads m Things for which less is preferred to more l Examples m Air pollution m Asbestos © 2005 Pearson Education, Inc. Chapter 3 36

Consumer Preferences l How do we account for bads in our preference analysis? m We redefine the commodity l Clean air l Pollution reduction l Asbestos removal © 2005 Pearson Education, Inc. Chapter 3 37

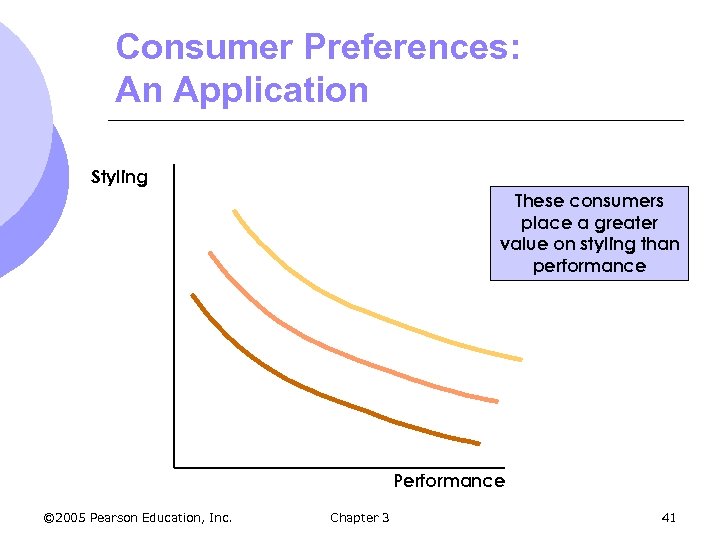

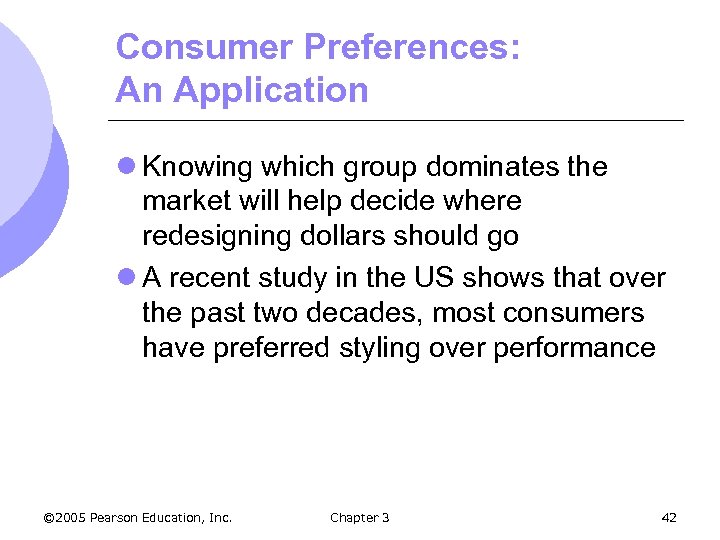

Consumer Preferences: An Application l In designing new cars, automobile executives must determine how much time and money to invest in restyling versus increased performance m Higher demand for car with better styling and performance m Both cost more to improve © 2005 Pearson Education, Inc. Chapter 3 38

Consumer Preferences: An Application l An analysis of consumer preferences would help to determine where to spend more on change: performance or styling l Some consumers will prefer better styling and some will prefer better performance © 2005 Pearson Education, Inc. Chapter 3 39

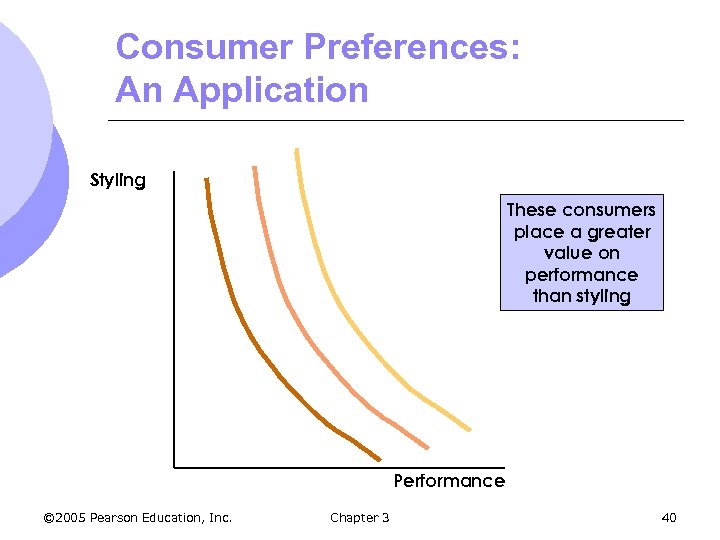

Consumer Preferences: An Application Styling These consumers place a greater value on performance than styling Performance © 2005 Pearson Education, Inc. Chapter 3 40

Consumer Preferences: An Application Styling These consumers place a greater value on styling than performance Performance © 2005 Pearson Education, Inc. Chapter 3 41

Consumer Preferences: An Application l Knowing which group dominates the market will help decide where redesigning dollars should go l A recent study in the US shows that over the past two decades, most consumers have preferred styling over performance © 2005 Pearson Education, Inc. Chapter 3 42

Preferences and Numerical Values l The theory of consumer behavior does not require assigning a numerical value to the level of satisfaction l Although ranking of market baskets is good, sometimes numerical value is useful © 2005 Pearson Education, Inc. Chapter 3 43

Consumer Preferences l Utility m. A numerical score representing the satisfaction that a consumer gets from a given market basket m If buying 3 copies of Microeconomics makes you happier than buying one shirt, then we say that the books give you more utility than the shirt © 2005 Pearson Education, Inc. Chapter 3 44

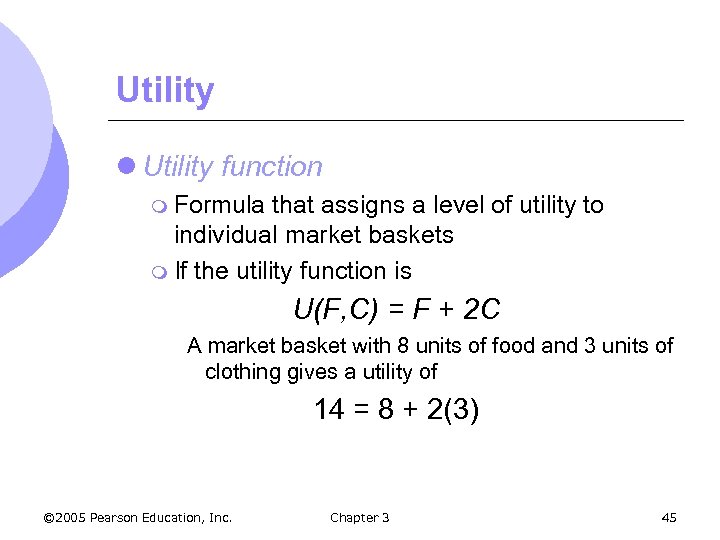

Utility l Utility function m Formula that assigns a level of utility to individual market baskets m If the utility function is U(F, C) = F + 2 C A market basket with 8 units of food and 3 units of clothing gives a utility of 14 = 8 + 2(3) © 2005 Pearson Education, Inc. Chapter 3 45

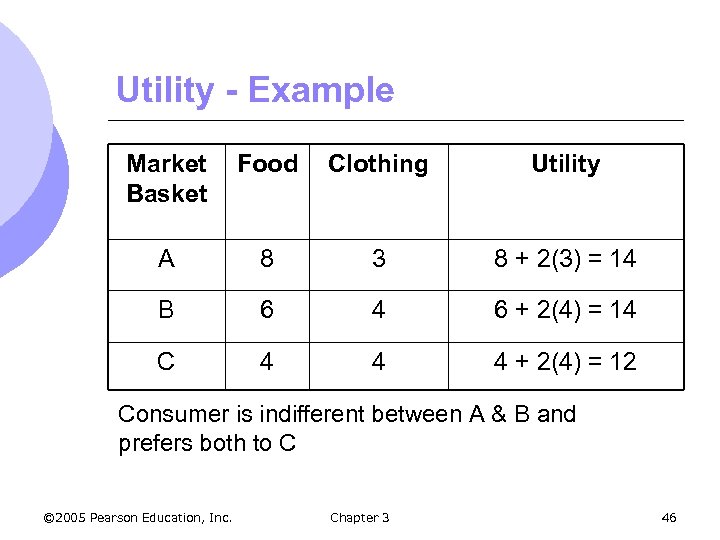

Utility - Example Market Basket Food Clothing Utility A 8 3 8 + 2(3) = 14 B 6 4 6 + 2(4) = 14 C 4 4 4 + 2(4) = 12 Consumer is indifferent between A & B and prefers both to C © 2005 Pearson Education, Inc. Chapter 3 46

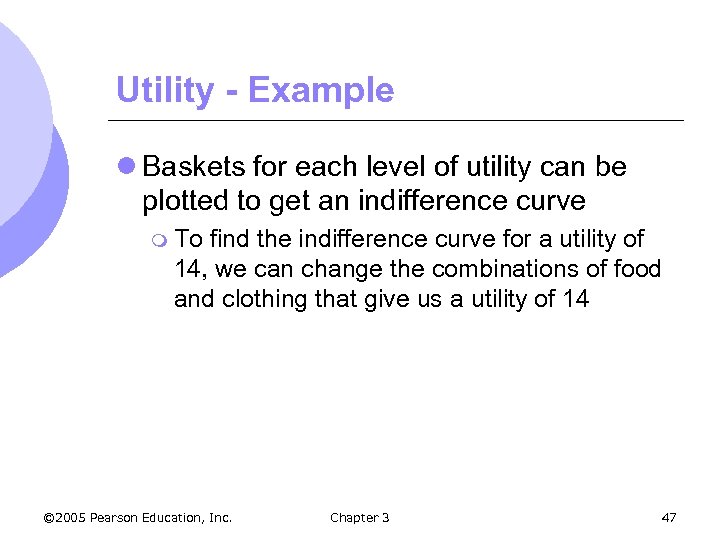

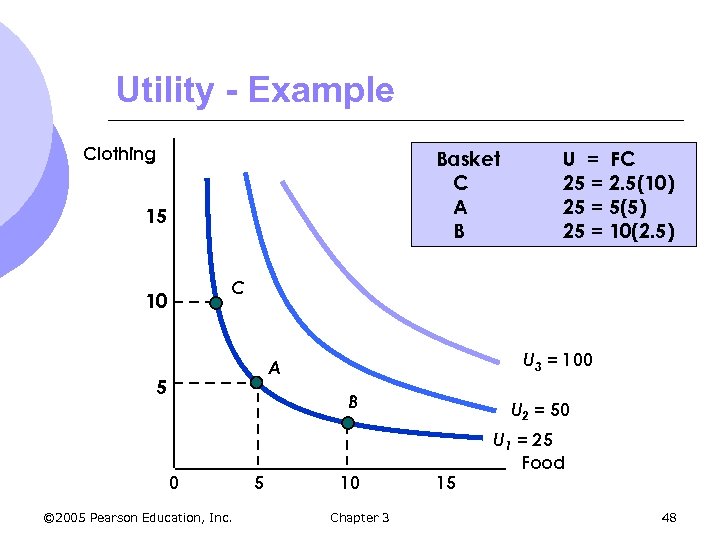

Utility - Example l Baskets for each level of utility can be plotted to get an indifference curve m To find the indifference curve for a utility of 14, we can change the combinations of food and clothing that give us a utility of 14 © 2005 Pearson Education, Inc. Chapter 3 47

Utility - Example Clothing Basket C A B 15 U = FC 25 = 2. 5(10) 25 = 5(5) 25 = 10(2. 5) C 10 U 3 = 100 A 5 B 0 © 2005 Pearson Education, Inc. 5 10 Chapter 3 U 2 = 50 15 U 1 = 25 Food 48

Utility l Although we numerically rank baskets and indifference curves, numbers are ONLY for ranking l A utility of 4 is not necessarily twice as good as a utility of 2, just better l There are two types of rankings m Ordinal ranking m Cardinal ranking © 2005 Pearson Education, Inc. Chapter 3 49

Utility l Ordinal Utility Function m Places market baskets in the order of most preferred to least preferred, but it does not indicate how much one market basket is preferred to another m Interpersonal comparisons impossible l Cardinal Utility Function m Utility function describing the extent to which one market basket is preferred to another © 2005 Pearson Education, Inc. Chapter 3 50

Budget Constraints l Preferences do not explain all of consumer behavior l Budget constraints also limit an individual’s ability to consume in light of the prices they must pay for various goods and services © 2005 Pearson Education, Inc. Chapter 3 51

Budget Constraints l The Budget Line m Indicates all combinations of two commodities for which total money spent equals total income m We assume only 2 goods are consumed, so we do not consider savings © 2005 Pearson Education, Inc. Chapter 3 52

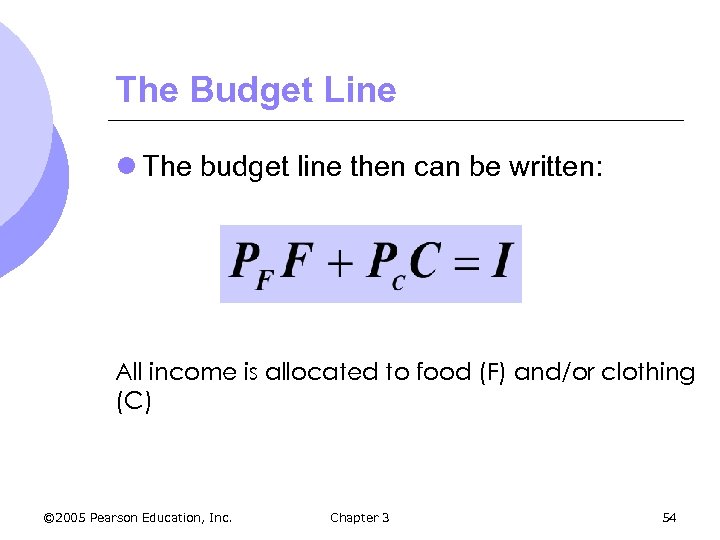

The Budget Line l Let F equal the amount of food purchased, and C is the amount of clothing l Price of food = PF and price of clothing = PC l Then PFF is the amount of money spent on food, and PCC is the amount of money spent on clothing © 2005 Pearson Education, Inc. Chapter 3 53

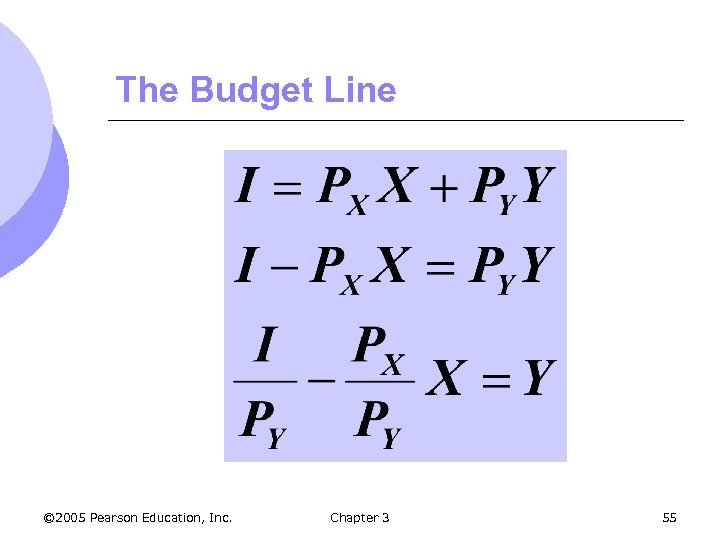

The Budget Line l The budget line then can be written: All income is allocated to food (F) and/or clothing (C) © 2005 Pearson Education, Inc. Chapter 3 54

The Budget Line © 2005 Pearson Education, Inc. Chapter 3 55

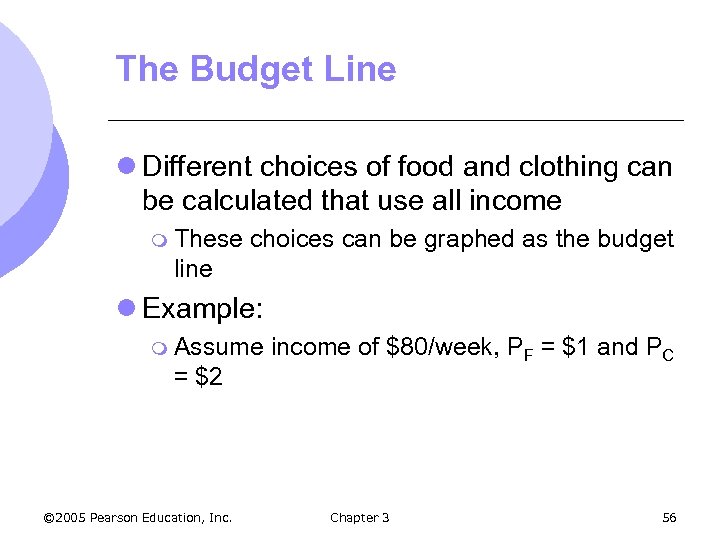

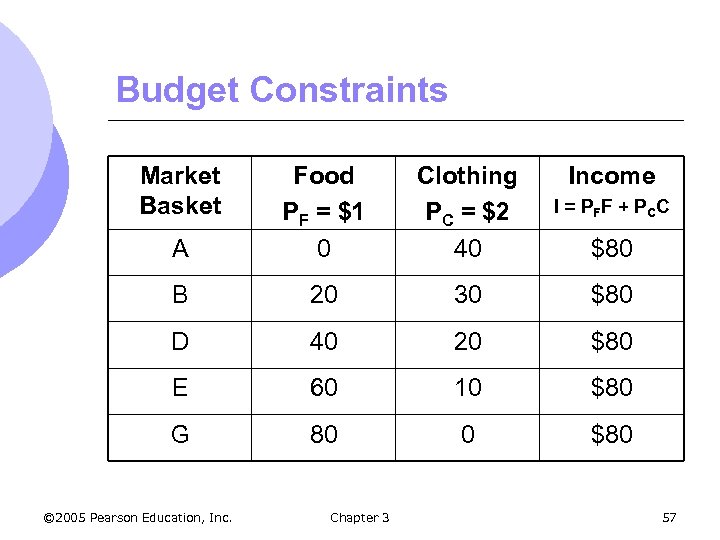

The Budget Line l Different choices of food and clothing can be calculated that use all income m These choices can be graphed as the budget line l Example: m Assume = $2 © 2005 Pearson Education, Inc. income of $80/week, PF = $1 and PC Chapter 3 56

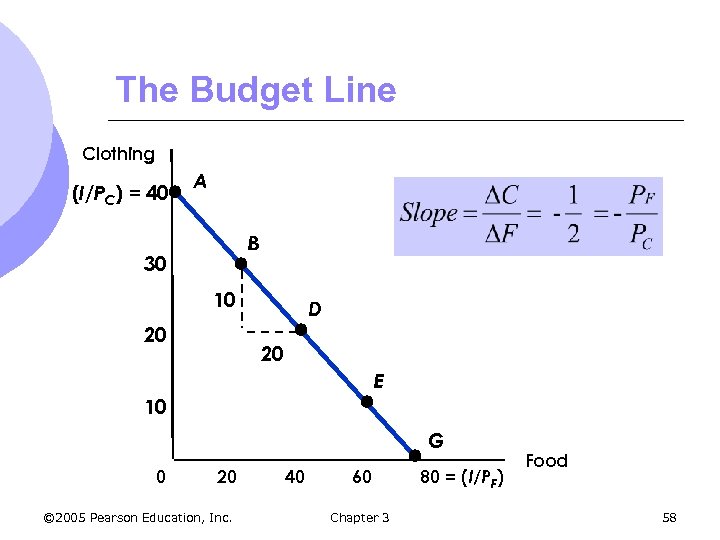

Budget Constraints Market Basket Clothing PC = $2 40 I = PFF + PCC A Food PF = $1 0 B 20 30 $80 D 40 20 $80 E 60 10 $80 G 80 0 $80 © 2005 Pearson Education, Inc. Chapter 3 Income $80 57

The Budget Line Clothing (I/PC) = 40 A B 30 10 20 D 20 E 10 G 0 20 © 2005 Pearson Education, Inc. 40 60 Chapter 3 80 = (I/PF) Food 58

The Budget Line l As consumption moves along a budget line from the intercept, the consumer spends less on one item and more on the other l The slope of the line measures the relative cost of food and clothing l The slope is the negative of the ratio of the prices of the two goods © 2005 Pearson Education, Inc. Chapter 3 59

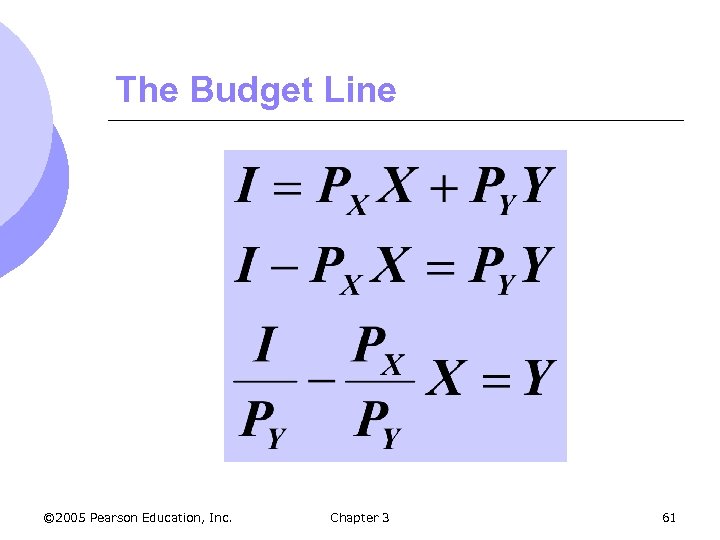

The Budget Line l The slope indicates the rate at which the two goods can be substituted without changing the amount of money spent l We can rearrange the budget line equation to make this more clear © 2005 Pearson Education, Inc. Chapter 3 60

The Budget Line © 2005 Pearson Education, Inc. Chapter 3 61

Budget Constraints l The Budget Line m The vertical intercept, I/PC, illustrates the maximum amount of C that can be purchased with income I m The horizontal intercept, I/PF, illustrates the maximum amount of F that can be purchased with income I © 2005 Pearson Education, Inc. Chapter 3 62

The Budget Line l As we know, income and prices can change l As incomes and prices change, there are changes in budget lines l We can show the effects of these changes on budget lines and consumer choices © 2005 Pearson Education, Inc. Chapter 3 63

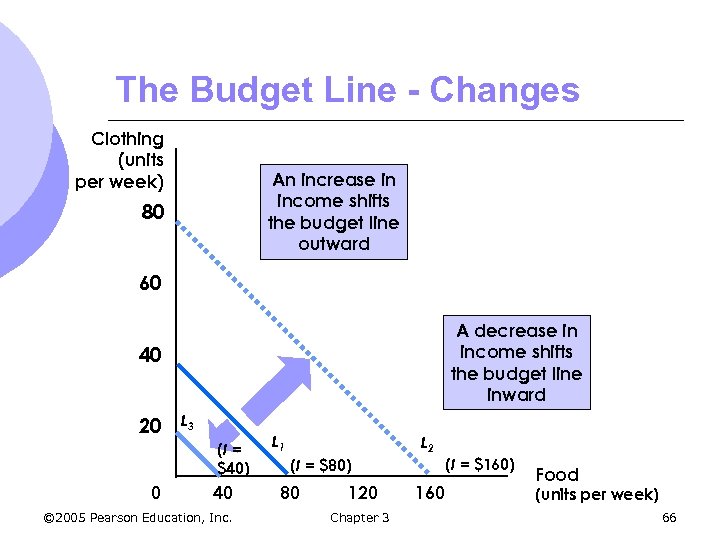

The Budget Line - Changes l The Effects of Changes in Income m An increase in income causes the budget line to shift outward, parallel to the original line (holding prices constant). m Can buy more of both goods with more income © 2005 Pearson Education, Inc. Chapter 3 64

The Budget Line - Changes l The Effects of Changes in Income m. A decrease in income causes the budget line to shift inward, parallel to the original line (holding prices constant) m Can buy less of both goods with less income © 2005 Pearson Education, Inc. Chapter 3 65

The Budget Line - Changes Clothing (units per week) An increase in income shifts the budget line outward 80 60 A decrease in income shifts the budget line inward 40 20 L 3 (I = $40) 0 40 © 2005 Pearson Education, Inc. L 1 L 2 (I = $80) 80 120 Chapter 3 (I = $160) 160 Food (units per week) 66

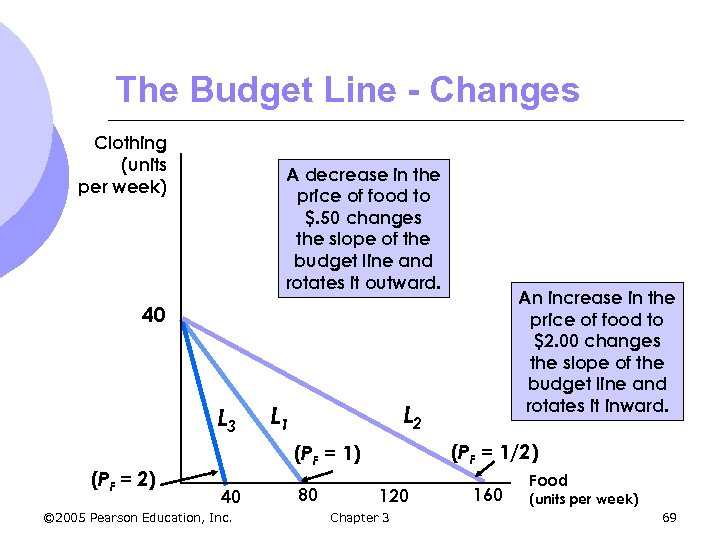

The Budget Line - Changes l The Effects of Changes in Prices m If the price of one good increases, the budget line shifts inward, pivoting from the other good’s intercept. m If the price of food increases and you buy only food (x-intercept), then you can’t buy as much food. The x-intercept shifts in. m If you buy only clothing (y-intercept), you can buy the same amount. No change in yintercept. © 2005 Pearson Education, Inc. Chapter 3 67

The Budget Line - Changes l The Effects of Changes in Prices m If the price of one good decreases, the budget line shifts outward, pivoting from the other good’s intercept. m If the price of food decreases and you buy only food (x-intercept), then you can buy more food. The x-intercept shifts out. m If you buy only clothing (y-intercept), you can buy the same amount. No change in yintercept. © 2005 Pearson Education, Inc. Chapter 3 68

The Budget Line - Changes Clothing (units per week) A decrease in the price of food to $. 50 changes the slope of the budget line and rotates it outward. An increase in the price of food to $2. 00 changes the slope of the budget line and rotates it inward. 40 L 3 (PF = 2) L 2 L 1 (PF = 1/2) (PF = 1) 40 © 2005 Pearson Education, Inc. 80 120 Chapter 3 160 Food (units per week) 69

The Budget Line - Changes l The Effects of Changes in Prices m If the two goods increase in price, but the ratio of the two prices is unchanged, the slope will not change m However, the budget line will shift inward parallel to the original budget line © 2005 Pearson Education, Inc. Chapter 3 70

The Budget Line - Changes l The Effects of Changes in Prices m If the two goods decrease in price, but the ratio of the two prices is unchanged, the slope will not change m However, the budget line will shift outward parallel to the original budget line © 2005 Pearson Education, Inc. Chapter 3 71

Consumer Choice l Given preferences and budget constraints, how do consumers choose what to buy? l Consumers choose a combination of goods that will maximize their satisfaction, given the limited budget available to them © 2005 Pearson Education, Inc. Chapter 3 72

Consumer Choice l The maximizing market basket must satisfy two conditions: 1. It must be located on the budget line m They spend all their income – more is better 2. It must give the consumer the most preferred combination of goods and services © 2005 Pearson Education, Inc. Chapter 3 73

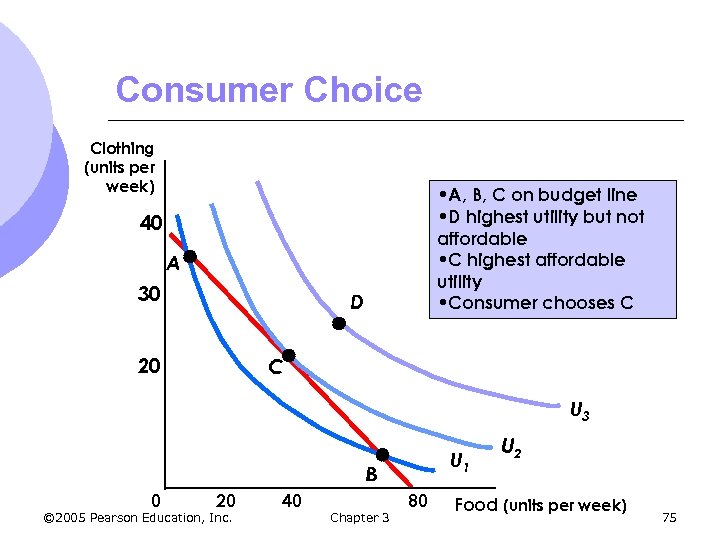

Consumer Choice l Graphically, we can see different indifference curves of a consumer choosing between clothing and food l Remember that U 3 > U 2 > U 1 for our indifference curves l Consumer wants to choose highest utility within their budget © 2005 Pearson Education, Inc. Chapter 3 74

Consumer Choice Clothing (units per week) • A, B, C on budget line • D highest utility but not affordable • C highest affordable utility • Consumer chooses C 40 A 30 D 20 C U 3 U 1 B 0 20 © 2005 Pearson Education, Inc. 40 Chapter 3 80 U 2 Food (units per week) 75

Consumer Choice l Consumer will choose highest indifference curve on budget line l In previous graph, point C is where the indifference curve is just tangent to the budget line l Slope of the budget line equals the slope of the indifference curve at this point © 2005 Pearson Education, Inc. Chapter 3 76

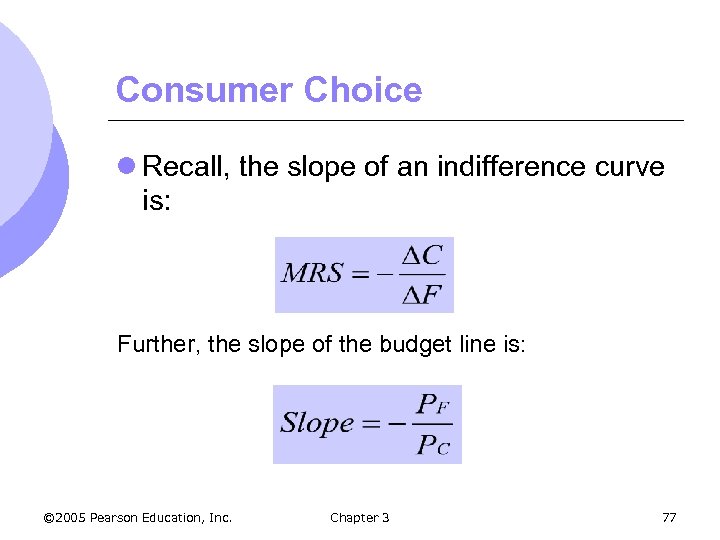

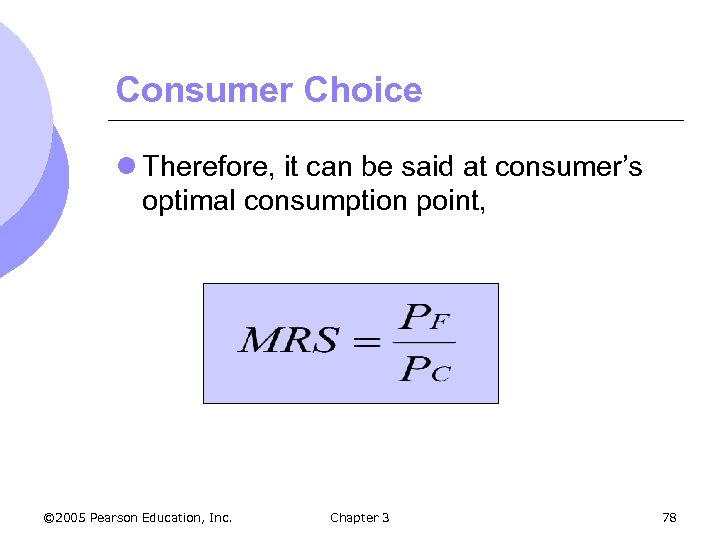

Consumer Choice l Recall, the slope of an indifference curve is: Further, the slope of the budget line is: © 2005 Pearson Education, Inc. Chapter 3 77

Consumer Choice l Therefore, it can be said at consumer’s optimal consumption point, © 2005 Pearson Education, Inc. Chapter 3 78

Consumer Choice l It can be said that satisfaction is maximized when marginal rate of substitution (of C for F) is equal to the ratio of the prices (of F to C) l Note this is ONLY true at the optimal consumption point © 2005 Pearson Education, Inc. Chapter 3 79

Consumer Choice l Optimal consumption point is where marginal benefits equal marginal costs l MB = MRS = benefit associated with consumption of 1 more unit of food l MC = cost of additional unit of food m 1 unit food = ½ unit clothing m PF/PC © 2005 Pearson Education, Inc. Chapter 3 80

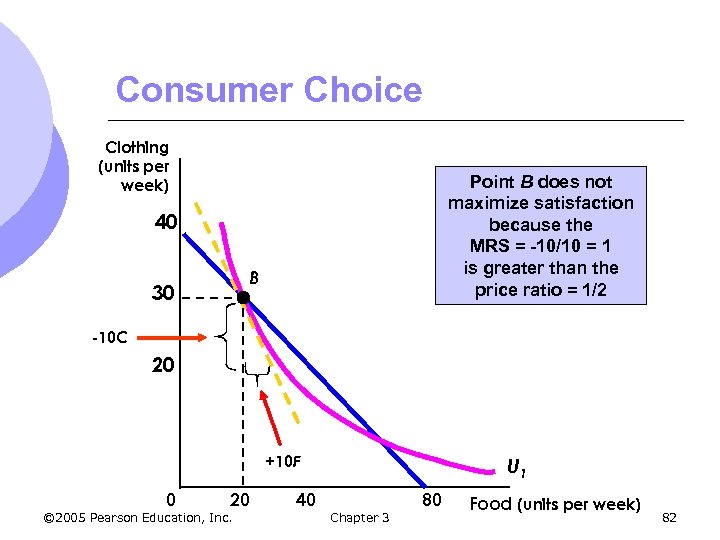

Consumer Choice l If MRS ≠ PF/PC then individuals can reallocate basket to increase utility l If MRS > PF/PC m Will increase food and decrease clothing until MRS = PF/PC l If MRS < PF/PC m Will increase clothing and decrease food until MRS = PF/PC © 2005 Pearson Education, Inc. Chapter 3 81

Consumer Choice Clothing (units per week) Point B does not maximize satisfaction because the MRS = -10/10 = 1 is greater than the price ratio = 1/2 40 B 30 -10 C 20 +10 F 0 20 © 2005 Pearson Education, Inc. 40 U 1 Chapter 3 80 Food (units per week) 82

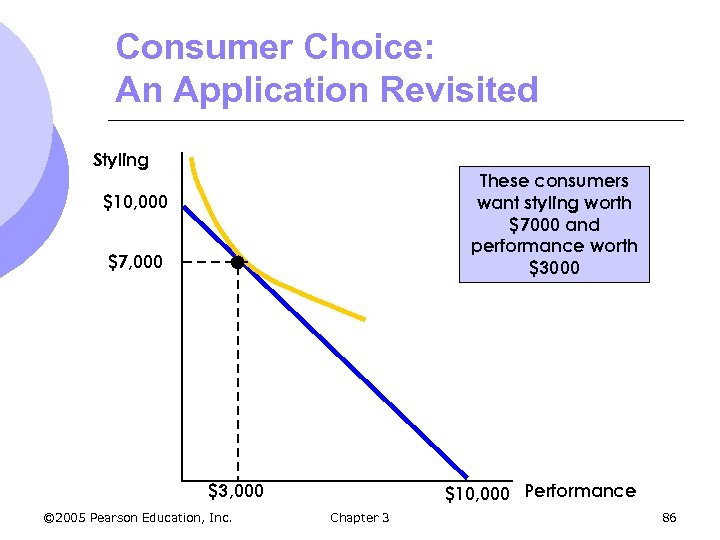

Consumer Choice: An Application Revisited l Consider two groups of consumers, each wishing to spend $10, 000 on the styling and performance of a car l Each group has different preferences © 2005 Pearson Education, Inc. Chapter 3 83

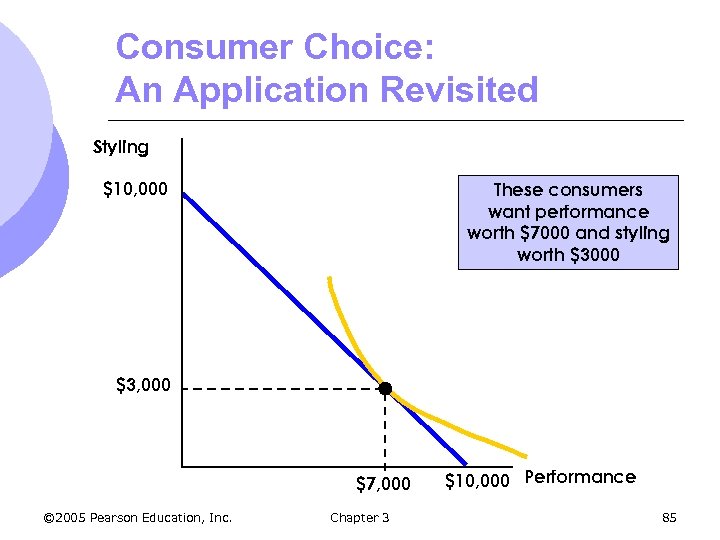

Consumer Choice: An Application Revisited l By finding the point of tangency between a group’s indifference curve and the budget constraint, auto companies can see how much consumers value each attribute © 2005 Pearson Education, Inc. Chapter 3 84

Consumer Choice: An Application Revisited Styling $10, 000 These consumers want performance worth $7000 and styling worth $3000 $3, 000 $7, 000 © 2005 Pearson Education, Inc. Chapter 3 $10, 000 Performance 85

Consumer Choice: An Application Revisited Styling These consumers want styling worth $7000 and performance worth $3000 $10, 000 $7, 000 $10, 000 Performance $3, 000 © 2005 Pearson Education, Inc. Chapter 3 86

Consumer Choice: An Application Revisited l Once a company knows preferences, it can design a production and marketing plan l Company can then make a sensible strategic business decision on how to allocate performance and styling on new cars © 2005 Pearson Education, Inc. Chapter 3 87

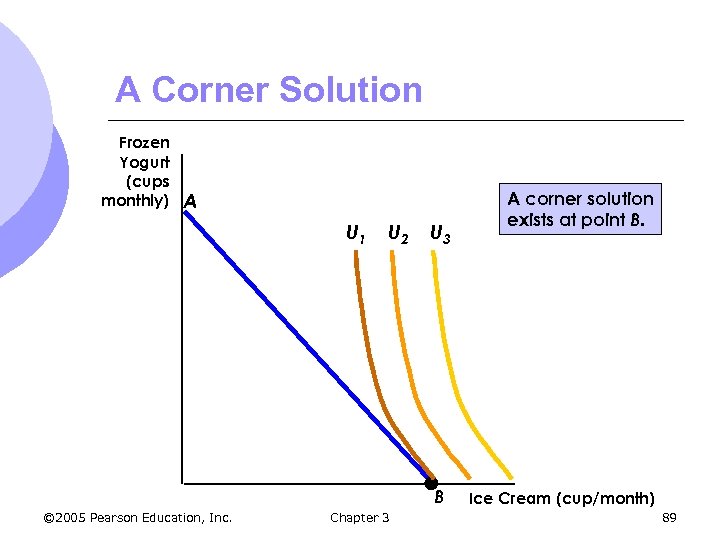

Consumer Choice l A corner solution exists if a consumer buys in extremes, and buys all of one category of good and none of another m MRS © 2005 Pearson Education, Inc. is not necessarily equal to PB/PA Chapter 3 88

A Corner Solution Frozen Yogurt (cups monthly) A U 1 U 2 U 3 B © 2005 Pearson Education, Inc. Chapter 3 A corner solution exists at point B. Ice Cream (cup/month) 89

A Corner Solution l At point B, the MRS of frozen yogurt for ice cream is greater than the slope of the budget line l If the consumer could give up more frozen yogurt for ice cream, he would do so l However, there is no more frozen yogurt to give up l Opposite is true if corner solution was at point A © 2005 Pearson Education, Inc. Chapter 3 90

A Corner Solution l When a corner solution arises, the consumer’s MRS does not necessarily equal the price ratio l In this instance it can be said that: © 2005 Pearson Education, Inc. Chapter 3 91

A Corner Solution l If the MRS is, in fact, significantly greater than the price ratio, then a small decrease in the price of frozen yogurt will not alter the consumer’s market basket © 2005 Pearson Education, Inc. Chapter 3 92

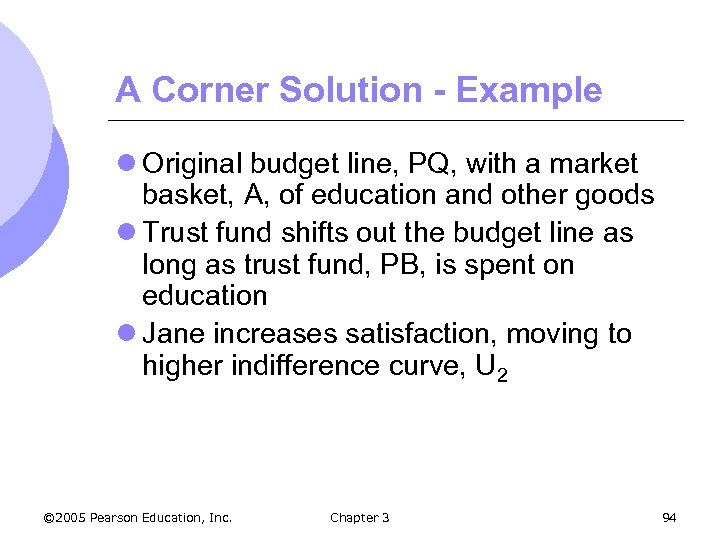

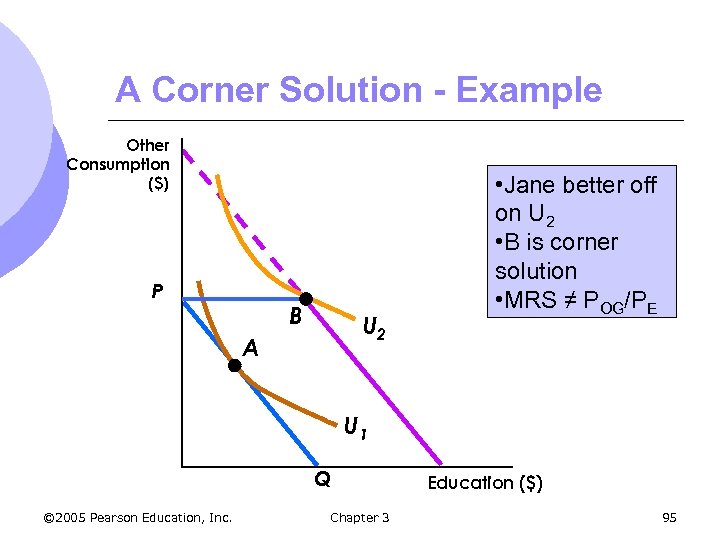

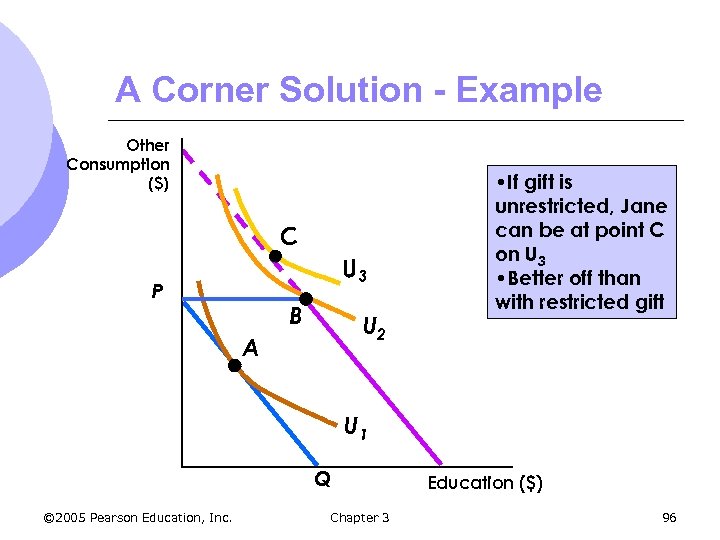

A Corner Solution - Example l Suppose Jane Doe’s parents set up a trust fund for her college education l The money must be used only for education l Although a welcome gift, an unrestricted gift might be better © 2005 Pearson Education, Inc. Chapter 3 93

A Corner Solution - Example l Original budget line, PQ, with a market basket, A, of education and other goods l Trust fund shifts out the budget line as long as trust fund, PB, is spent on education l Jane increases satisfaction, moving to higher indifference curve, U 2 © 2005 Pearson Education, Inc. Chapter 3 94

A Corner Solution - Example Other Consumption ($) P B U 2 A • Jane better off on U 2 • B is corner solution • MRS ≠ POG/PE U 1 Q © 2005 Pearson Education, Inc. Chapter 3 Education ($) 95

A Corner Solution - Example Other Consumption ($) C U 3 P B U 2 A • If gift is unrestricted, Jane can be at point C on U 3 • Better off than with restricted gift U 1 Q © 2005 Pearson Education, Inc. Chapter 3 Education ($) 96

Marginal Utility and Consumer Choice l Marginal utility measures the additional satisfaction obtained from consuming one additional unit of a good m How much happier is the individual from consuming one more unit of food? © 2005 Pearson Education, Inc. Chapter 3 97

Marginal Utility - Example l The marginal utility derived from increasing from 0 to 1 units of food might be 9 l Increasing from 1 to 2 might be 7 l Increasing from 2 to 3 might be 5 l Observation: Marginal utility is diminishing as consumption increases © 2005 Pearson Education, Inc. Chapter 3 98

Marginal Utility l The principle of diminishing marginal utility states that as more of a good is consumed, the additional utility the consumer gains will be smaller and smaller l Note that total utility will continue to increase since consumer makes choices that make them happier © 2005 Pearson Education, Inc. Chapter 3 99

Marginal Utility and Indifference Curves l As consumption moves along an indifference curve: m Additional utility derived from an increase in the consumption one good, food (F), must balance the loss of utility from the decrease in the consumption in the other good, clothing (C) © 2005 Pearson Education, Inc. Chapter 3 100

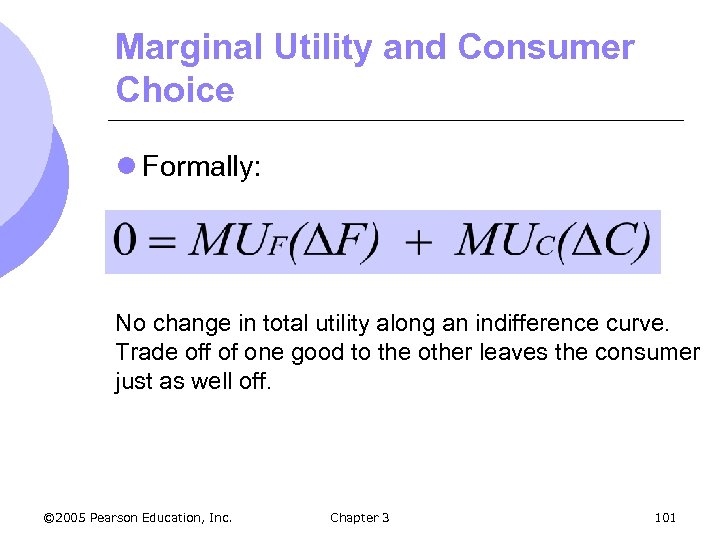

Marginal Utility and Consumer Choice l Formally: No change in total utility along an indifference curve. Trade off of one good to the other leaves the consumer just as well off. © 2005 Pearson Education, Inc. Chapter 3 101

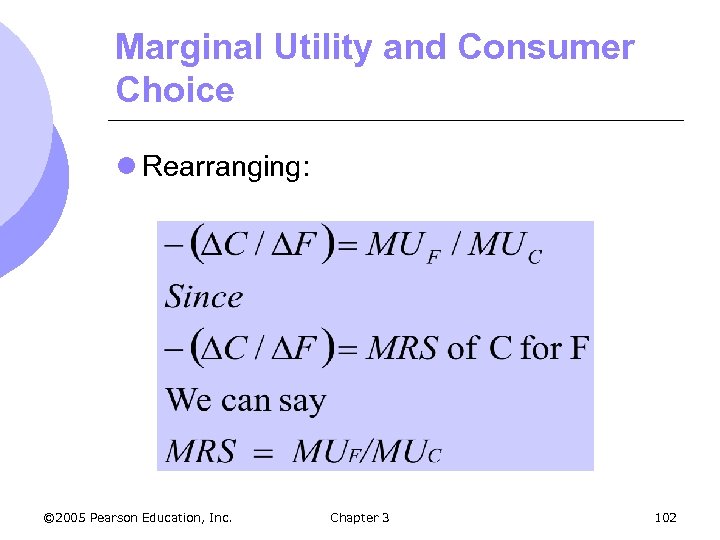

Marginal Utility and Consumer Choice l Rearranging: © 2005 Pearson Education, Inc. Chapter 3 102

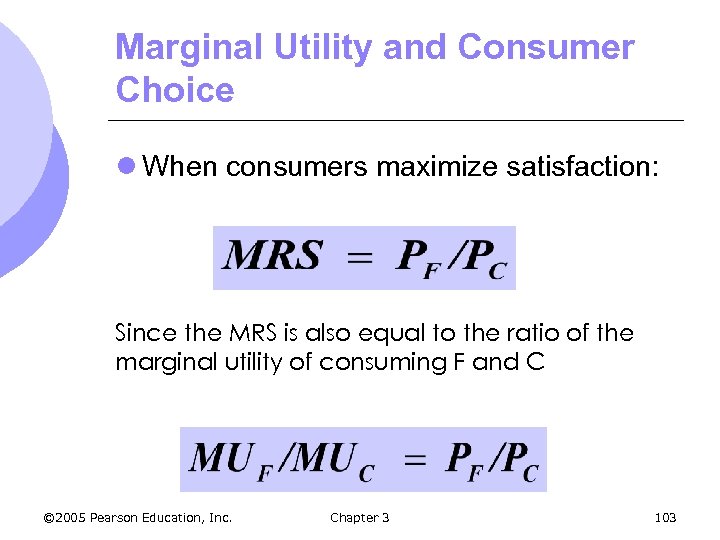

Marginal Utility and Consumer Choice l When consumers maximize satisfaction: Since the MRS is also equal to the ratio of the marginal utility of consuming F and C © 2005 Pearson Education, Inc. Chapter 3 103

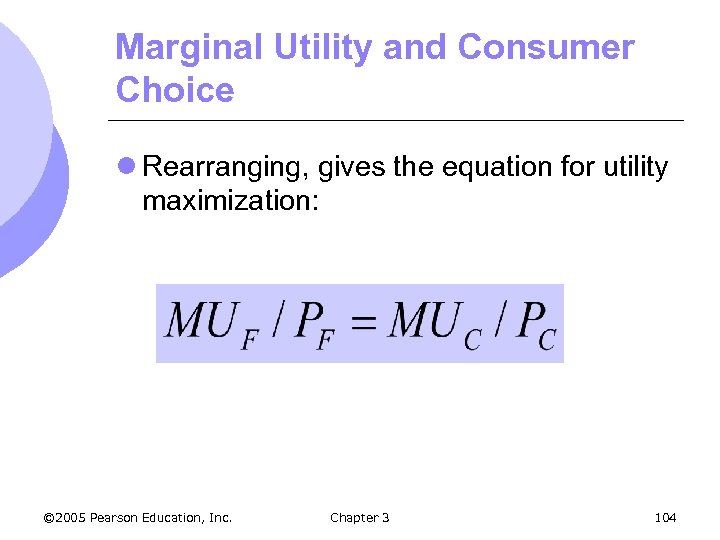

Marginal Utility and Consumer Choice l Rearranging, gives the equation for utility maximization: © 2005 Pearson Education, Inc. Chapter 3 104

Marginal Utility and Consumer Choice l Total utility is maximized when the budget is allocated so that the marginal utility per dollar of expenditure is the same for each good. l This is referred to as the equal marginal principle. © 2005 Pearson Education, Inc. Chapter 3 105

Cost-of-Living Indexes l Social Security payments are given to qualifying individuals l Each year the benefit increases equal to the rate of increase of the Consumer Price Index (CPI) m Ratio of the present cost of typical bundle of goods/services in comparison to the cost during a base period © 2005 Pearson Education, Inc. Chapter 3 106

Cost-of-Living Indexes l Does the CPI give a good measure of inflation and therefore a measure of the cost of living changes? l Should the CPI be used to measure how much cost of living has increased, determining increases in government payment programs? © 2005 Pearson Education, Inc. Chapter 3 107

Cost-of-Living Indexes l The ideal cost of living index represents the cost of attaining a given level of utility at current prices relative to the cost of attaining the same utility at base prices l Takes into account the fact that consumers can and will substitute some goods for others © 2005 Pearson Education, Inc. Chapter 3 108

Cost-of-Living Indexes l To obtain the ideal cost of living index would require too much information, such as consumer preferences as well as prices and expenditures l Actual price indexes are based on consumer purchases, not preferences © 2005 Pearson Education, Inc. Chapter 3 109

Cost-of-Living Indexes l Laspeyres price index m Amount of money at current year prices that an individual requires to purchase a bundle of goods/services chosen in a base year divided by the cost of purchasing the same bundle at base-year prices m Ex: CPI © 2005 Pearson Education, Inc. Chapter 3 110

Cost-of-Living Indexes l The Laspeyres price index assumes that consumers do not alter their consumption patterns as prices change l Tends to overstate the true cost of living index l Using the CPI to adjust retirement benefits will tend to overcompensate most recipients, requiring greater government expenditure © 2005 Pearson Education, Inc. Chapter 3 111

Cost-of-Living Indexes l Paasche index m Focuses on the cost of buying the current year’s bundle m Amount of money at current-year prices that an individual requires to purchase a current bundle of goods/services divided by the cost of purchasing the same bundle in a base year © 2005 Pearson Education, Inc. Chapter 3 112

Cost-of-Living Indexes l Comparison of indexes m Both are fixed weight indexes m Quantities of various goods and services in each index remain unchanged m Laspeyres index keeps quantities at base year levels m Paasche index keeps unchanged quantities at current year levels © 2005 Pearson Education, Inc. Chapter 3 113

Cost-of-Living Indexes l Paasche Index understates inflation l Overstates the cost of the base year bundle (current bundle at base year prices) – consumer would not have chosen that bundle with different relative prices l Thus, denominator overstated and index is understated © 2005 Pearson Education, Inc. Chapter 3 114

Cost-of-Living Indexes l Chain-Weighted Indexes m Cost-of-living index that accounts for changes in quantities of goods and services m Introduced to overcome problems that arose when long-term comparisons were made using fixed weight price indexes © 2005 Pearson Education, Inc. Chapter 3 115

Practice: Chapter 3, #15 l 15. Jane receives utility from days spent traveling on vacation domestically (D) and days spent traveling on vacation in a foreign country (F), as given by the utility function: U = 10 DF. In addition, the price of a day spent traveling domestically is $100, the price of a day spent traveling in a foreign country is $400, and Jane’s annual travel budget is $4, 000. l Illustrate the indifference curve associated with a utility of 800 and the indifference curve associated with a utility of 1200. © 2005 Pearson Education, Inc. Chapter 3 116

Practice l The indifference curve with a utility of 800 has the equation 10 DF=800, or DF=80. Choose combinations of D and F whose product is 80 to find a few bundles. The indifference curve with a utility of 1200 has the equation 10 DF=1200, or DF=120. Choose combinations of D and F whose product is 120 to find a few bundles. © 2005 Pearson Education, Inc. Chapter 3 117

Practice l l Can Jane afford any of the bundles that give her a utility of 800? What about a utility of 1200? Yes she can afford some of the bundles that give her a utility of 800 as part of this indifference curve lies below the budget line. She cannot afford any of the bundles that give her a utility of 1200 as this whole indifference curve lies above the budget line. © 2005 Pearson Education, Inc. Chapter 3 118

Practice l Find Jane’s utility maximizing choice of days spent traveling domestically and days spent in a foreign country. (We will need to set the slope of the budget line equal to the slope of the indifference curve by taking two derivatives. ) © 2005 Pearson Education, Inc. Chapter 3 119

Practice l The optimal bundle is where the slope of the indifference curve is equal to the slope of the budget line, and Jane is spending her entire income. The slope of the budget line is -PD/PF = -1/4 l The slope of the indifference curve is: MRS= -MUD/MUF = -10 F/10 D = -F/D l Setting the two equal we get: -F/D = -1/4 l We now have two equations and two unknowns: 4 F=D and 100 D+400 F=$4000 l Solving the above two equations gives D=20 and F=5. Utility is 1000. l This bundle is on an indifference curve between the two you had previously drawn. © 2005 Pearson Education, Inc. Chapter 3 120

Practice: Chapter 3, #4 l Janelle and Brian each plan to spend $20, 000 on the styling and gas mileage features of a new car. They can each choose all styling, all gas mileage, or some combination of the two. Janelle does not care at all about styling and wants the best gas mileage possible. Brian likes both equally and wants to spend an equal amount on the two features. Using indifference curves and budget lines, illustrate the choice that each person will make. © 2005 Pearson Education, Inc. Chapter 3 121

Practice l Assume styling is on the vertical axis and gas mileage is on the horizontal axis. Janelle has indifference curves that are vertical. As her indifference curves move over to the right, she gains more gas mileage and more satisfaction. She will spend all $20, 000 on gas mileage. This is a corner solution. © 2005 Pearson Education, Inc. Chapter 3 122

Practice l Brian has indifference curves that are Lshaped. He will not spend more on one feature than on the other feature. He will spend $10, 000 on styling and $10, 000 on gas mileage. Styling and gas mileage are perfect complements for Brian. © 2005 Pearson Education, Inc. Chapter 3 123

Homework Due Wednesday, October 24 l Exercises Chapter 3: #3, #4 and #5 l Questions for Review Chapter 4: #3 and #8 © 2005 Pearson Education, Inc. Chapter 3 124

ef1455945ed0517a8d07e4c9224932fe.ppt