9f8fd4fac2f099552771893c1a0769ef.ppt

- Количество слайдов: 34

Portfolio Theory

Portfolio Theory

![An Investor’s Preference E[Return] 4 2 3 1 Risk • 2 dominates 1 - An Investor’s Preference E[Return] 4 2 3 1 Risk • 2 dominates 1 -](https://present5.com/presentation/9f8fd4fac2f099552771893c1a0769ef/image-2.jpg) An Investor’s Preference E[Return] 4 2 3 1 Risk • 2 dominates 1 - same risk, but higher return • 2 dominates 3 - same return, but lower risk • 4 dominates 3 – same risk, but higher return

An Investor’s Preference E[Return] 4 2 3 1 Risk • 2 dominates 1 - same risk, but higher return • 2 dominates 3 - same return, but lower risk • 4 dominates 3 – same risk, but higher return

![Indifference Curves Indifference Curve E[Return] - Represents individual’s willingness to trade-off return and risk Indifference Curves Indifference Curve E[Return] - Represents individual’s willingness to trade-off return and risk](https://present5.com/presentation/9f8fd4fac2f099552771893c1a0769ef/image-3.jpg) Indifference Curves Indifference Curve E[Return] - Represents individual’s willingness to trade-off return and risk - Assumptions: 1) 5 Axioms 2) Prefer more to less (Greedy) => Max E[U(W)] 3) Risk aversion Increasing Expected Utility Risk

Indifference Curves Indifference Curve E[Return] - Represents individual’s willingness to trade-off return and risk - Assumptions: 1) 5 Axioms 2) Prefer more to less (Greedy) => Max E[U(W)] 3) Risk aversion Increasing Expected Utility Risk

![Indifference Curves Indifference Curve Expected Return E[R] - Represents individual’s willingness to trade-off return Indifference Curves Indifference Curve Expected Return E[R] - Represents individual’s willingness to trade-off return](https://present5.com/presentation/9f8fd4fac2f099552771893c1a0769ef/image-4.jpg) Indifference Curves Indifference Curve Expected Return E[R] - Represents individual’s willingness to trade-off return and risk - Assumptions: 1) 5 Axioms 2) Prefer more to less (Greedy) => Max E[U(W)] 3) Risk aversion 4) Assets jointly normally distributed Increasing Expected Utility Standard Deviation σR

Indifference Curves Indifference Curve Expected Return E[R] - Represents individual’s willingness to trade-off return and risk - Assumptions: 1) 5 Axioms 2) Prefer more to less (Greedy) => Max E[U(W)] 3) Risk aversion 4) Assets jointly normally distributed Increasing Expected Utility Standard Deviation σR

The transition Indifference Curve - Represents individual’s willingness to trade-off return and risk - Assumptions: From U(E[RETURN], RISK) To U(expected return, standard deviation of return) • This transition means the objects of choice for an investor is normally distributed. • Because only if a random variable’s distribution is normally distributed can it be adequately described by its mean and standard deviation. • This poses a question: “Does that mean the return of any risky asset is always normally-distributed? ” 1) 5 Axioms 2) Prefer more to less (Greedy) => Max E[U(W)] 3) Risk aversion 4) Assets jointly normally distributed The answer: NO! Individual risky asset’s return is not normally-distributed. So why should we assume normally-distributed returns for the objects of choice?

The transition Indifference Curve - Represents individual’s willingness to trade-off return and risk - Assumptions: From U(E[RETURN], RISK) To U(expected return, standard deviation of return) • This transition means the objects of choice for an investor is normally distributed. • Because only if a random variable’s distribution is normally distributed can it be adequately described by its mean and standard deviation. • This poses a question: “Does that mean the return of any risky asset is always normally-distributed? ” 1) 5 Axioms 2) Prefer more to less (Greedy) => Max E[U(W)] 3) Risk aversion 4) Assets jointly normally distributed The answer: NO! Individual risky asset’s return is not normally-distributed. So why should we assume normally-distributed returns for the objects of choice?

The transition Indifference Curve - Represents individual’s willingness to trade-off return and risk - Assumptions: From U(RETURN, RISK) To U(expected return, standard deviation of return) • This transition means the objects of choice for an investor is normally distributed. • Because only if a distribution is normally distributed can it be described only by its mean and standard deviation. • This poses a question: “Does that mean the return of any risky assets is always normally-distributed? ” 1) 5 Axioms 2) Prefer more to less (Greedy) => Max E[U(W)] 3) Risk aversion 4) Assets jointly normally distributed The answer: NO! Individual risky asset’s return is not normally distributed. So why should we assume normally distributed returns for the objects of choice? BECAUSE RATIONAL INDIVIDUAL INVESTORS DO NOT INVEST ONLY IN A SINGLE ASSET!

The transition Indifference Curve - Represents individual’s willingness to trade-off return and risk - Assumptions: From U(RETURN, RISK) To U(expected return, standard deviation of return) • This transition means the objects of choice for an investor is normally distributed. • Because only if a distribution is normally distributed can it be described only by its mean and standard deviation. • This poses a question: “Does that mean the return of any risky assets is always normally-distributed? ” 1) 5 Axioms 2) Prefer more to less (Greedy) => Max E[U(W)] 3) Risk aversion 4) Assets jointly normally distributed The answer: NO! Individual risky asset’s return is not normally distributed. So why should we assume normally distributed returns for the objects of choice? BECAUSE RATIONAL INDIVIDUAL INVESTORS DO NOT INVEST ONLY IN A SINGLE ASSET!

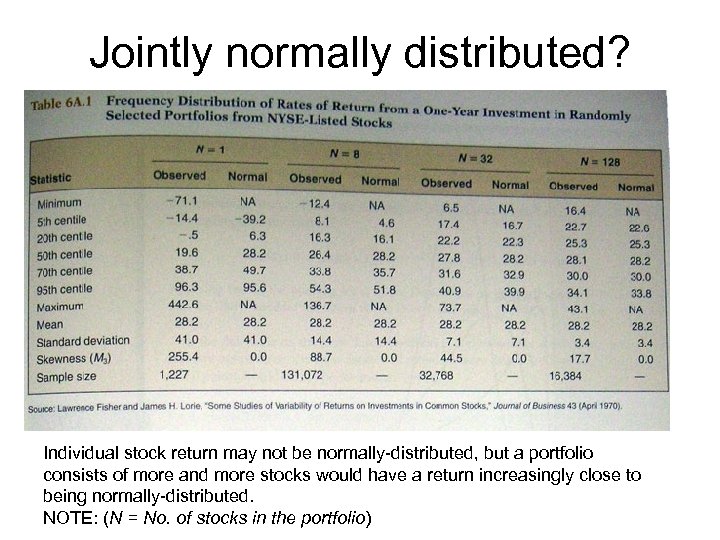

Jointly normally distributed? Individual stock return may not be normally-distributed, but a portfolio consists of more and more stocks would have a return increasingly close to being normally-distributed. NOTE: (N = No. of stocks in the portfolio)

Jointly normally distributed? Individual stock return may not be normally-distributed, but a portfolio consists of more and more stocks would have a return increasingly close to being normally-distributed. NOTE: (N = No. of stocks in the portfolio)

Jointly normally-distributed? 1 st moment: 2 nd moment: Mean = Expected return of portfolio Variance = Variance of the return of portfolio (RISKNESS) Mean and Var as sole choice variables => Distribution of return can be adequately described by mean and variance only That means, distribution has to be normally-distributed. 3 reasons to support mean-variance criteria 1) As the table shows, portfolios consisting of large number of risky assets tend to have returns that are very close to normally-distributed. 2) The fact that investors re-balance their own portfolios frequently will act so as to make higher moments (3 rd, 4 th, etc) unimportant (Samuelson 1970). 3) Cost-effective consideration: data required to compute 3 rd and 4 th moments are very demanding. Both computational and cost inefficient.

Jointly normally-distributed? 1 st moment: 2 nd moment: Mean = Expected return of portfolio Variance = Variance of the return of portfolio (RISKNESS) Mean and Var as sole choice variables => Distribution of return can be adequately described by mean and variance only That means, distribution has to be normally-distributed. 3 reasons to support mean-variance criteria 1) As the table shows, portfolios consisting of large number of risky assets tend to have returns that are very close to normally-distributed. 2) The fact that investors re-balance their own portfolios frequently will act so as to make higher moments (3 rd, 4 th, etc) unimportant (Samuelson 1970). 3) Cost-effective consideration: data required to compute 3 rd and 4 th moments are very demanding. Both computational and cost inefficient.

Conclusion • From the investor’s point of view, it is cost-effective, and more intuitive. • From the objects of choice, if the unit of choice is an investment portfolio with large number of risky assets, it is close to normally-distributed. • So we are convinced that the indifference curves on the 2 -D space makes sense. • Now, we’ll work on the computations of expected return and standard deviation (i. e. , the square root of variance) of an investment portfolio. • We make our lives easier by assuming individual risky assets’ returns are normally-distributed to illustrate. We don’t buy this assumption, but for the purpose of math, we’ll stick with it.

Conclusion • From the investor’s point of view, it is cost-effective, and more intuitive. • From the objects of choice, if the unit of choice is an investment portfolio with large number of risky assets, it is close to normally-distributed. • So we are convinced that the indifference curves on the 2 -D space makes sense. • Now, we’ll work on the computations of expected return and standard deviation (i. e. , the square root of variance) of an investment portfolio. • We make our lives easier by assuming individual risky assets’ returns are normally-distributed to illustrate. We don’t buy this assumption, but for the purpose of math, we’ll stick with it.

Math Review I • Asset j’s return in State s: Rjs = (Ws – W 0) / W 0 • Expected return on asset j: E(Rj) = ∑s. Prob(State=s)x. Rjs • Asset j’s variance: σ2 j = ∑s. Prob(State=s)x[Rjs- E(Rj)]2 • Asset j’s standard deviation: σj = √σ2 j • Thus, Rj ~ N(E(Rj), σ2 j)

Math Review I • Asset j’s return in State s: Rjs = (Ws – W 0) / W 0 • Expected return on asset j: E(Rj) = ∑s. Prob(State=s)x. Rjs • Asset j’s variance: σ2 j = ∑s. Prob(State=s)x[Rjs- E(Rj)]2 • Asset j’s standard deviation: σj = √σ2 j • Thus, Rj ~ N(E(Rj), σ2 j)

Math Review I • Covariance of asset i’s return & j’s return: Cov(Ri, Rj)= E[(Ris- E(Ri))x(Rjs- E(Rj))] =∑s. Prob(State=s)x[Ris- E(Ri)]x[Rjs- E(Rj)] • Correlation of asset i’s return & j’s return: ρij = Cov(Ri, Rj) / (σiσj) -1 ≤ ρij ≤ 1 When ρij = 1 => i and j are perfectly positively correlated. They move together all the time. When ρij = -1 => i and j are perfectly negatively correlated. They move opposite to each other all the time.

Math Review I • Covariance of asset i’s return & j’s return: Cov(Ri, Rj)= E[(Ris- E(Ri))x(Rjs- E(Rj))] =∑s. Prob(State=s)x[Ris- E(Ri)]x[Rjs- E(Rj)] • Correlation of asset i’s return & j’s return: ρij = Cov(Ri, Rj) / (σiσj) -1 ≤ ρij ≤ 1 When ρij = 1 => i and j are perfectly positively correlated. They move together all the time. When ρij = -1 => i and j are perfectly negatively correlated. They move opposite to each other all the time.

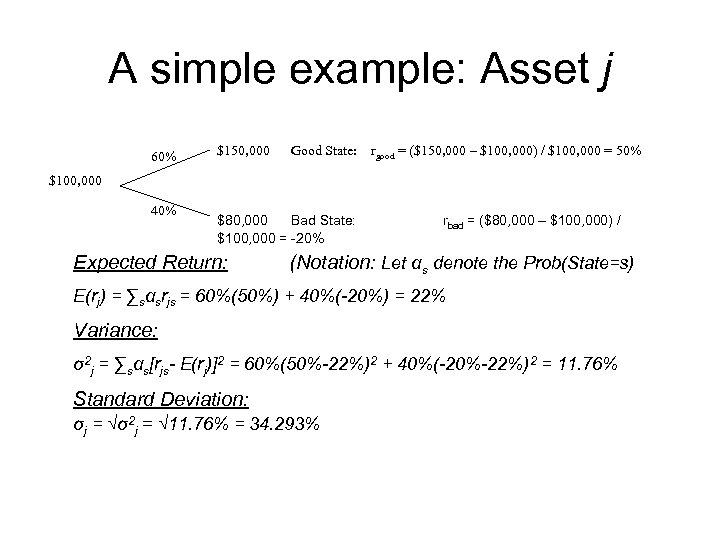

A simple example: Asset j 60% $150, 000 Good State: rgood = ($150, 000 – $100, 000) / $100, 000 = 50% $100, 000 40% $80, 000 Bad State: $100, 000 = -20% Expected Return: rbad = ($80, 000 – $100, 000) / (Notation: Let αs denote the Prob(State=s) E(rj) = ∑sαsrjs = 60%(50%) + 40%(-20%) = 22% Variance: σ2 j = ∑sαs[rjs- E(rj)]2 = 60%(50%-22%)2 + 40%(-20%-22%)2 = 11. 76% Standard Deviation: σj = √σ2 j = √ 11. 76% = 34. 293%

A simple example: Asset j 60% $150, 000 Good State: rgood = ($150, 000 – $100, 000) / $100, 000 = 50% $100, 000 40% $80, 000 Bad State: $100, 000 = -20% Expected Return: rbad = ($80, 000 – $100, 000) / (Notation: Let αs denote the Prob(State=s) E(rj) = ∑sαsrjs = 60%(50%) + 40%(-20%) = 22% Variance: σ2 j = ∑sαs[rjs- E(rj)]2 = 60%(50%-22%)2 + 40%(-20%-22%)2 = 11. 76% Standard Deviation: σj = √σ2 j = √ 11. 76% = 34. 293%

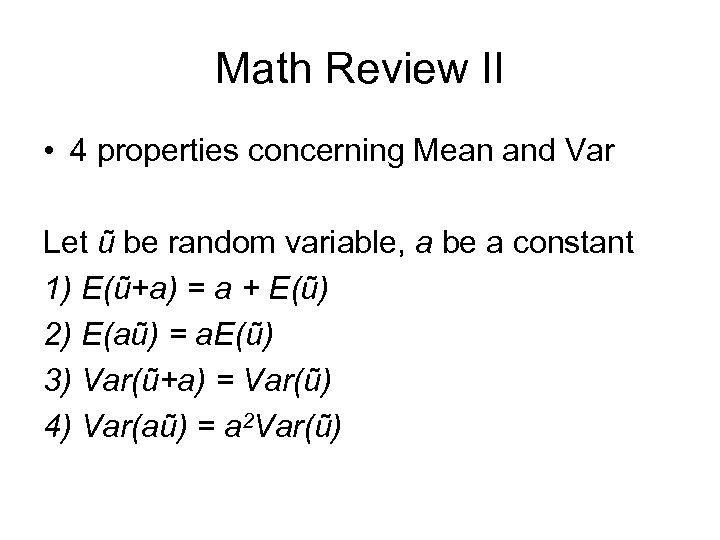

Math Review II • 4 properties concerning Mean and Var Let ũ be random variable, a be a constant 1) E(ũ+a) = a + E(ũ) 2) E(aũ) = a. E(ũ) 3) Var(ũ+a) = Var(ũ) 4) Var(aũ) = a 2 Var(ũ)

Math Review II • 4 properties concerning Mean and Var Let ũ be random variable, a be a constant 1) E(ũ+a) = a + E(ũ) 2) E(aũ) = a. E(ũ) 3) Var(ũ+a) = Var(ũ) 4) Var(aũ) = a 2 Var(ũ)

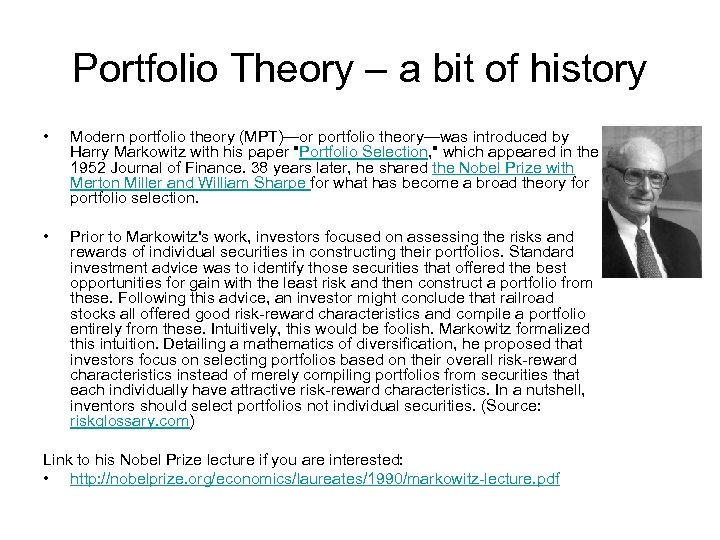

Portfolio Theory – a bit of history • Modern portfolio theory (MPT)—or portfolio theory—was introduced by Harry Markowitz with his paper "Portfolio Selection, " which appeared in the 1952 Journal of Finance. 38 years later, he shared the Nobel Prize with Merton Miller and William Sharpe for what has become a broad theory for portfolio selection. • Prior to Markowitz's work, investors focused on assessing the risks and rewards of individual securities in constructing their portfolios. Standard investment advice was to identify those securities that offered the best opportunities for gain with the least risk and then construct a portfolio from these. Following this advice, an investor might conclude that railroad stocks all offered good risk-reward characteristics and compile a portfolio entirely from these. Intuitively, this would be foolish. Markowitz formalized this intuition. Detailing a mathematics of diversification, he proposed that investors focus on selecting portfolios based on their overall risk-reward characteristics instead of merely compiling portfolios from securities that each individually have attractive risk-reward characteristics. In a nutshell, inventors should select portfolios not individual securities. (Source: riskglossary. com) Link to his Nobel Prize lecture if you are interested: • http: //nobelprize. org/economics/laureates/1990/markowitz-lecture. pdf

Portfolio Theory – a bit of history • Modern portfolio theory (MPT)—or portfolio theory—was introduced by Harry Markowitz with his paper "Portfolio Selection, " which appeared in the 1952 Journal of Finance. 38 years later, he shared the Nobel Prize with Merton Miller and William Sharpe for what has become a broad theory for portfolio selection. • Prior to Markowitz's work, investors focused on assessing the risks and rewards of individual securities in constructing their portfolios. Standard investment advice was to identify those securities that offered the best opportunities for gain with the least risk and then construct a portfolio from these. Following this advice, an investor might conclude that railroad stocks all offered good risk-reward characteristics and compile a portfolio entirely from these. Intuitively, this would be foolish. Markowitz formalized this intuition. Detailing a mathematics of diversification, he proposed that investors focus on selecting portfolios based on their overall risk-reward characteristics instead of merely compiling portfolios from securities that each individually have attractive risk-reward characteristics. In a nutshell, inventors should select portfolios not individual securities. (Source: riskglossary. com) Link to his Nobel Prize lecture if you are interested: • http: //nobelprize. org/economics/laureates/1990/markowitz-lecture. pdf

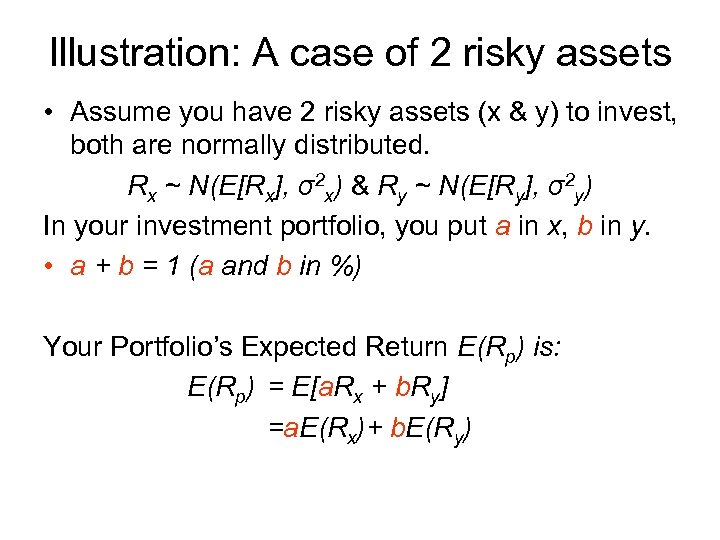

Illustration: A case of 2 risky assets • Assume you have 2 risky assets (x & y) to invest, both are normally distributed. Rx ~ N(E[Rx], σ2 x) & Ry ~ N(E[Ry], σ2 y) In your investment portfolio, you put a in x, b in y. • a + b = 1 (a and b in %) Your Portfolio’s Expected Return E(Rp) is: E(Rp) = E[a. Rx + b. Ry] =a. E(Rx)+ b. E(Ry)

Illustration: A case of 2 risky assets • Assume you have 2 risky assets (x & y) to invest, both are normally distributed. Rx ~ N(E[Rx], σ2 x) & Ry ~ N(E[Ry], σ2 y) In your investment portfolio, you put a in x, b in y. • a + b = 1 (a and b in %) Your Portfolio’s Expected Return E(Rp) is: E(Rp) = E[a. Rx + b. Ry] =a. E(Rx)+ b. E(Ry)

![Illustration: A case of 2 risky assets • Rx ~ N(E[Rx], σ2 x) & Illustration: A case of 2 risky assets • Rx ~ N(E[Rx], σ2 x) &](https://present5.com/presentation/9f8fd4fac2f099552771893c1a0769ef/image-16.jpg) Illustration: A case of 2 risky assets • Rx ~ N(E[Rx], σ2 x) & Ry ~ N(E[Ry], σ2 y) To calculate your Portfolio Variance: σ2 p = E[Rp - E(Rp)]2 = E[(a. Rx + b. Ry)-E[a. Rx + b. Ry]]2 = E[(a. Rx - a. E[Rx])+(b. Ry - b. E[b. Ry])]2 = E[a 2(Rx - E[Rx])2 + b 2(Ry - E[Ry])2 + 2 ab(Rx- E[Rx])(Ry - E[Ry])] = a 2 σ2 x + b 2 σ2 y + 2 ab. Cov(Rx, Ry) Var σ2 p = a 2 σ2 x + b 2 σ2 y + 2 abσxσyρxy s. d. σp = √(a 2 σ2 x + b 2 σ2 y + 2 abσxσyρxy) • Thus, the portfolio’s return is normally distributed too Rp ~ N(E[Rp], σ2 p)

Illustration: A case of 2 risky assets • Rx ~ N(E[Rx], σ2 x) & Ry ~ N(E[Ry], σ2 y) To calculate your Portfolio Variance: σ2 p = E[Rp - E(Rp)]2 = E[(a. Rx + b. Ry)-E[a. Rx + b. Ry]]2 = E[(a. Rx - a. E[Rx])+(b. Ry - b. E[b. Ry])]2 = E[a 2(Rx - E[Rx])2 + b 2(Ry - E[Ry])2 + 2 ab(Rx- E[Rx])(Ry - E[Ry])] = a 2 σ2 x + b 2 σ2 y + 2 ab. Cov(Rx, Ry) Var σ2 p = a 2 σ2 x + b 2 σ2 y + 2 abσxσyρxy s. d. σp = √(a 2 σ2 x + b 2 σ2 y + 2 abσxσyρxy) • Thus, the portfolio’s return is normally distributed too Rp ~ N(E[Rp], σ2 p)

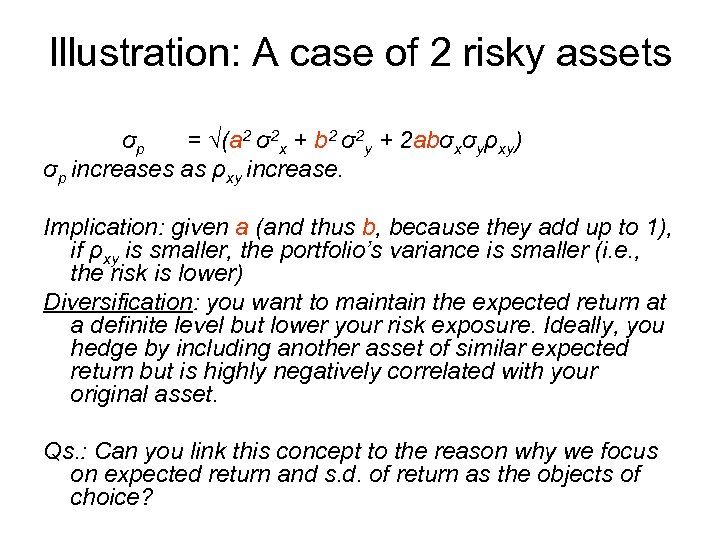

Illustration: A case of 2 risky assets σp = √(a 2 σ2 x + b 2 σ2 y + 2 abσxσyρxy) σp increases as ρxy increase. Implication: given a (and thus b, because they add up to 1), if ρxy is smaller, the portfolio’s variance is smaller (i. e. , the risk is lower) Diversification: you want to maintain the expected return at a definite level but lower your risk exposure. Ideally, you hedge by including another asset of similar expected return but is highly negatively correlated with your original asset. Qs. : Can you link this concept to the reason why we focus on expected return and s. d. of return as the objects of choice?

Illustration: A case of 2 risky assets σp = √(a 2 σ2 x + b 2 σ2 y + 2 abσxσyρxy) σp increases as ρxy increase. Implication: given a (and thus b, because they add up to 1), if ρxy is smaller, the portfolio’s variance is smaller (i. e. , the risk is lower) Diversification: you want to maintain the expected return at a definite level but lower your risk exposure. Ideally, you hedge by including another asset of similar expected return but is highly negatively correlated with your original asset. Qs. : Can you link this concept to the reason why we focus on expected return and s. d. of return as the objects of choice?

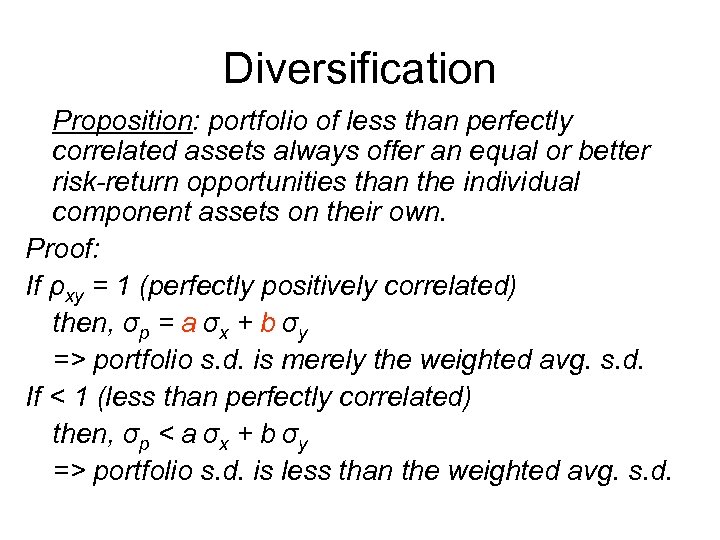

Diversification Proposition: portfolio of less than perfectly correlated assets always offer an equal or better risk-return opportunities than the individual component assets on their own. Proof: If ρxy = 1 (perfectly positively correlated) then, σp = a σx + b σy => portfolio s. d. is merely the weighted avg. s. d. If < 1 (less than perfectly correlated) then, σp < a σx + b σy => portfolio s. d. is less than the weighted avg. s. d.

Diversification Proposition: portfolio of less than perfectly correlated assets always offer an equal or better risk-return opportunities than the individual component assets on their own. Proof: If ρxy = 1 (perfectly positively correlated) then, σp = a σx + b σy => portfolio s. d. is merely the weighted avg. s. d. If < 1 (less than perfectly correlated) then, σp < a σx + b σy => portfolio s. d. is less than the weighted avg. s. d.

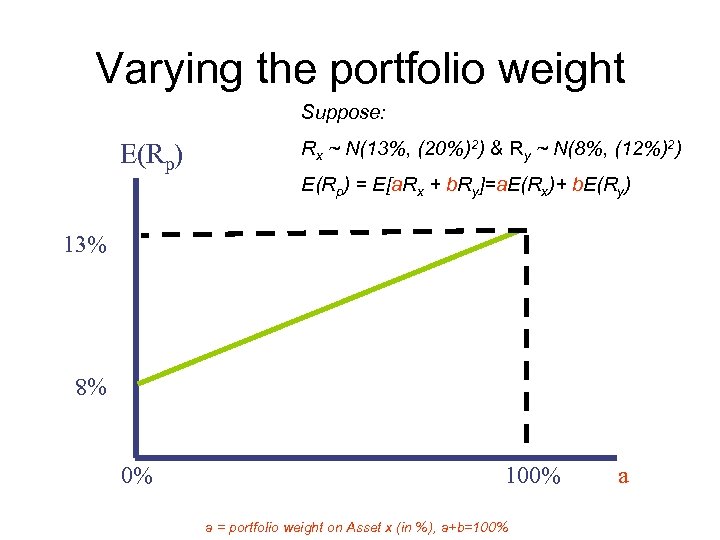

Varying the portfolio weight Suppose: E(Rp) Rx ~ N(13%, (20%)2) & Ry ~ N(8%, (12%)2) E(Rp) = E[a. Rx + b. Ry]=a. E(Rx)+ b. E(Ry) 13% %8 0% 100% a = portfolio weight on Asset x (in %), a+b=100% a

Varying the portfolio weight Suppose: E(Rp) Rx ~ N(13%, (20%)2) & Ry ~ N(8%, (12%)2) E(Rp) = E[a. Rx + b. Ry]=a. E(Rx)+ b. E(Ry) 13% %8 0% 100% a = portfolio weight on Asset x (in %), a+b=100% a

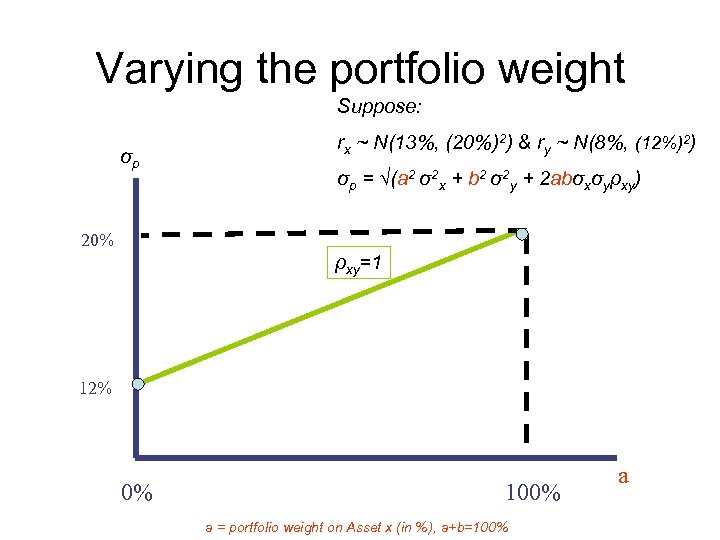

Varying the portfolio weight Suppose: σp rx ~ N(13%, (20%)2) & ry ~ N(8%, (12%)2) σp = √(a 2 σ2 x + b 2 σ2 y + 2 abσxσyρxy) 20% ρxy=1 12% 0% 100% a = portfolio weight on Asset x (in %), a+b=100% a

Varying the portfolio weight Suppose: σp rx ~ N(13%, (20%)2) & ry ~ N(8%, (12%)2) σp = √(a 2 σ2 x + b 2 σ2 y + 2 abσxσyρxy) 20% ρxy=1 12% 0% 100% a = portfolio weight on Asset x (in %), a+b=100% a

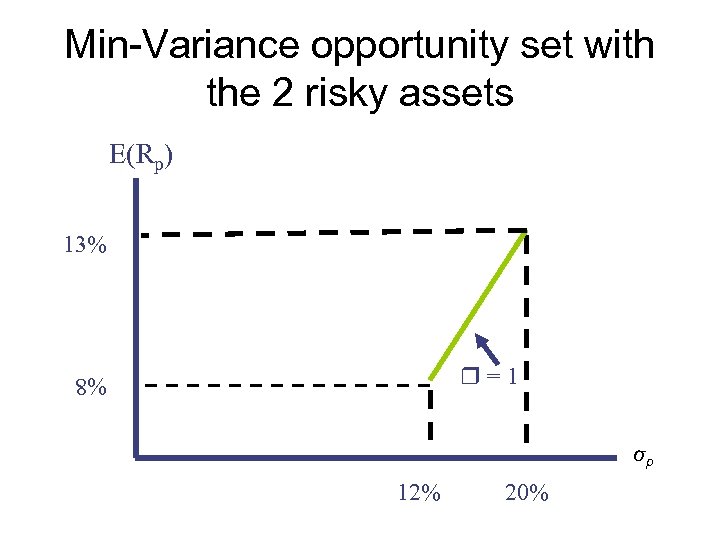

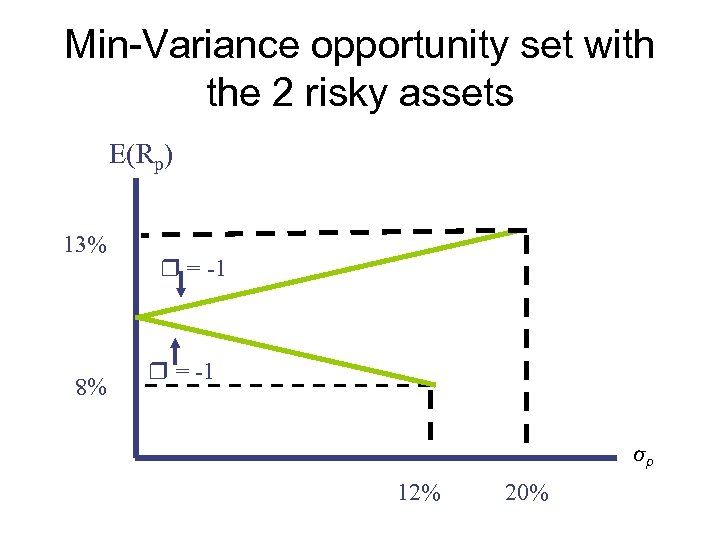

Min-Variance opportunity set with the 2 risky assets E(Rp) 13% =1 %8 σp 12% 20%

Min-Variance opportunity set with the 2 risky assets E(Rp) 13% =1 %8 σp 12% 20%

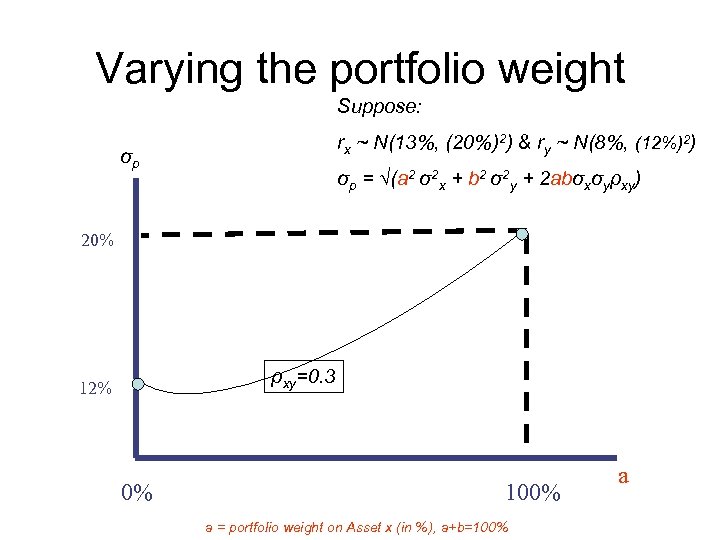

Varying the portfolio weight Suppose: rx ~ N(13%, (20%)2) & ry ~ N(8%, (12%)2) σp σp = √(a 2 σ2 x + b 2 σ2 y + 2 abσxσyρxy) 20% ρxy=0. 3 12% 0% 100% a = portfolio weight on Asset x (in %), a+b=100% a

Varying the portfolio weight Suppose: rx ~ N(13%, (20%)2) & ry ~ N(8%, (12%)2) σp σp = √(a 2 σ2 x + b 2 σ2 y + 2 abσxσyρxy) 20% ρxy=0. 3 12% 0% 100% a = portfolio weight on Asset x (in %), a+b=100% a

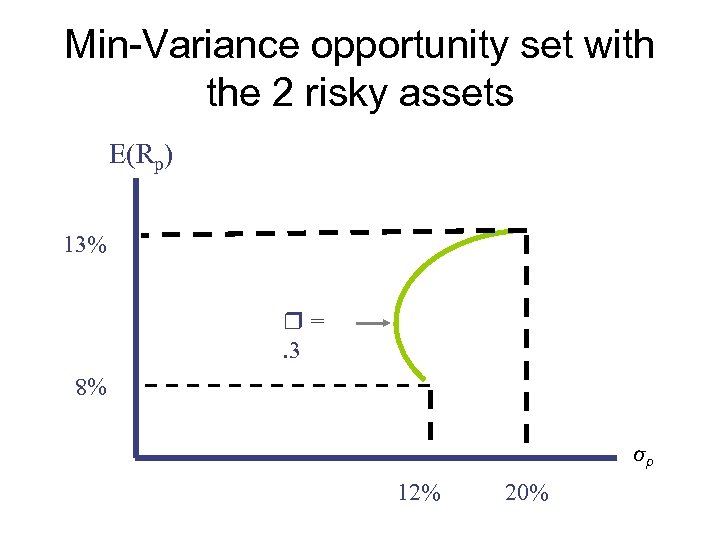

Min-Variance opportunity set with the 2 risky assets E(Rp) 13% =. 3 %8 σp 12% 20%

Min-Variance opportunity set with the 2 risky assets E(Rp) 13% =. 3 %8 σp 12% 20%

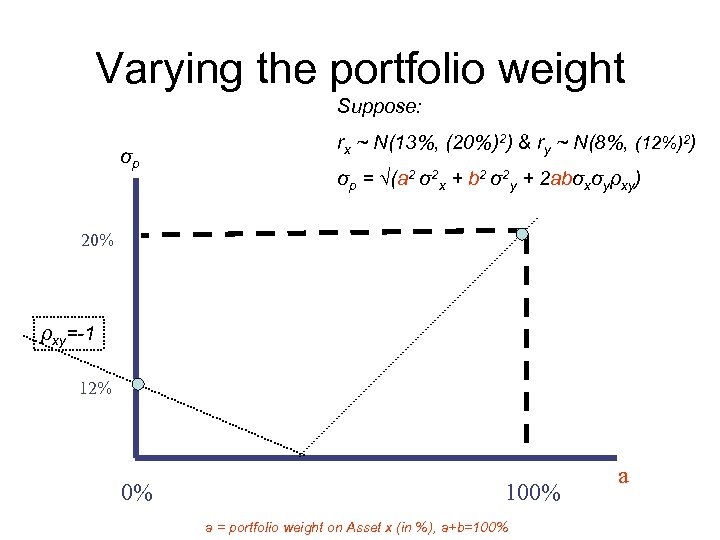

Varying the portfolio weight Suppose: σp rx ~ N(13%, (20%)2) & ry ~ N(8%, (12%)2) σp = √(a 2 σ2 x + b 2 σ2 y + 2 abσxσyρxy) 20% ρxy=-1 12% 0% 100% a = portfolio weight on Asset x (in %), a+b=100% a

Varying the portfolio weight Suppose: σp rx ~ N(13%, (20%)2) & ry ~ N(8%, (12%)2) σp = √(a 2 σ2 x + b 2 σ2 y + 2 abσxσyρxy) 20% ρxy=-1 12% 0% 100% a = portfolio weight on Asset x (in %), a+b=100% a

Min-Variance opportunity set with the 2 risky assets E(Rp) 13% = -1 σp 12% 20% %8

Min-Variance opportunity set with the 2 risky assets E(Rp) 13% = -1 σp 12% 20% %8

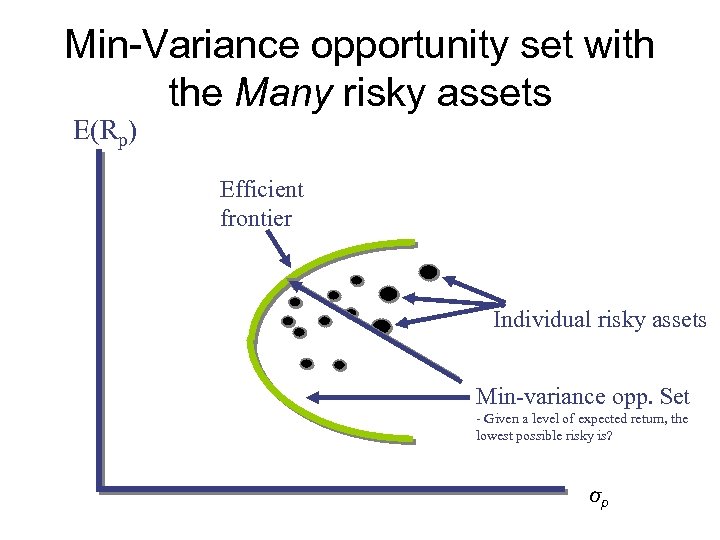

Min-Variance opportunity set with the Many risky assets E(Rp) Efficient frontier Individual risky assets Min-variance opp. Set - Given a level of expected return, the lowest possible risky is? σp

Min-Variance opportunity set with the Many risky assets E(Rp) Efficient frontier Individual risky assets Min-variance opp. Set - Given a level of expected return, the lowest possible risky is? σp

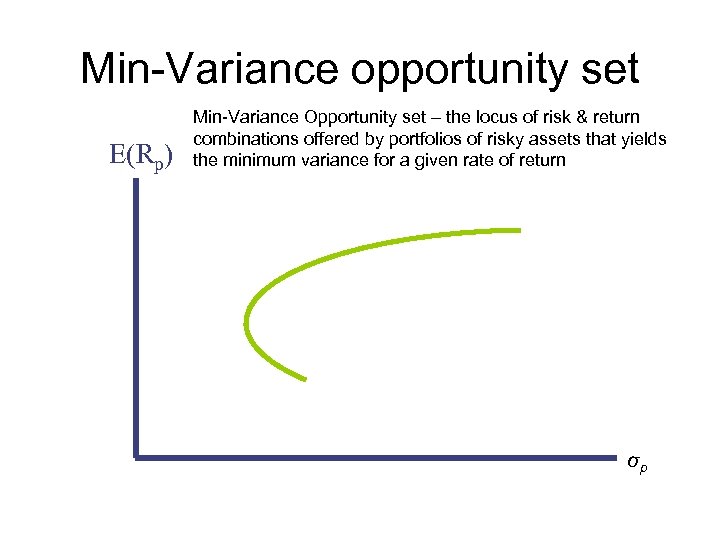

Min-Variance opportunity set E(Rp) Min-Variance Opportunity set – the locus of risk & return combinations offered by portfolios of risky assets that yields the minimum variance for a given rate of return σp

Min-Variance opportunity set E(Rp) Min-Variance Opportunity set – the locus of risk & return combinations offered by portfolios of risky assets that yields the minimum variance for a given rate of return σp

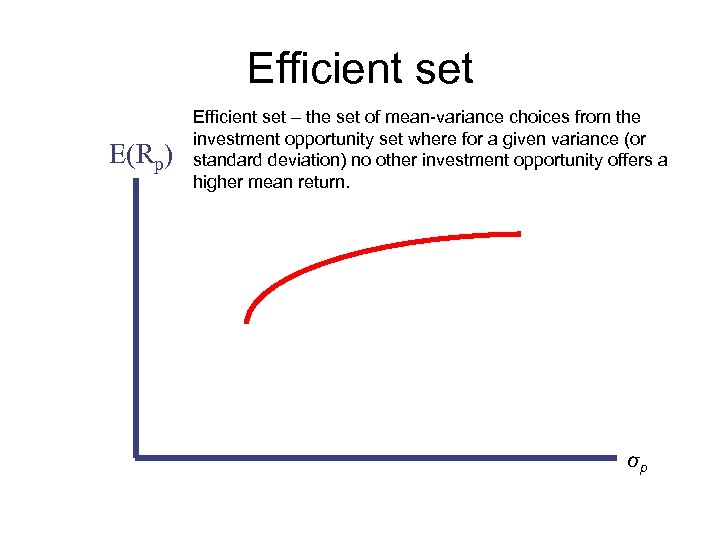

Efficient set E(Rp) Efficient set – the set of mean-variance choices from the investment opportunity set where for a given variance (or standard deviation) no other investment opportunity offers a higher mean return. σp

Efficient set E(Rp) Efficient set – the set of mean-variance choices from the investment opportunity set where for a given variance (or standard deviation) no other investment opportunity offers a higher mean return. σp

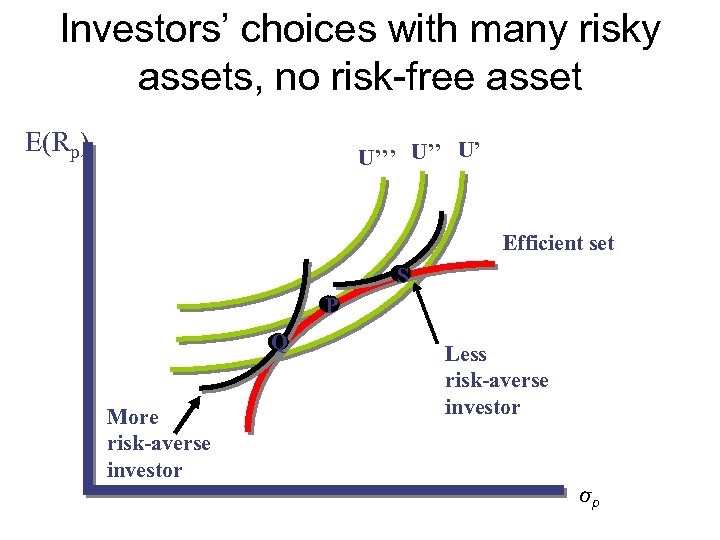

Investors’ choices with many risky assets, no risk-free asset E(Rp) U’’’ U’ Efficient set S P Q More risk-averse investor Less risk-averse investor σp

Investors’ choices with many risky assets, no risk-free asset E(Rp) U’’’ U’ Efficient set S P Q More risk-averse investor Less risk-averse investor σp

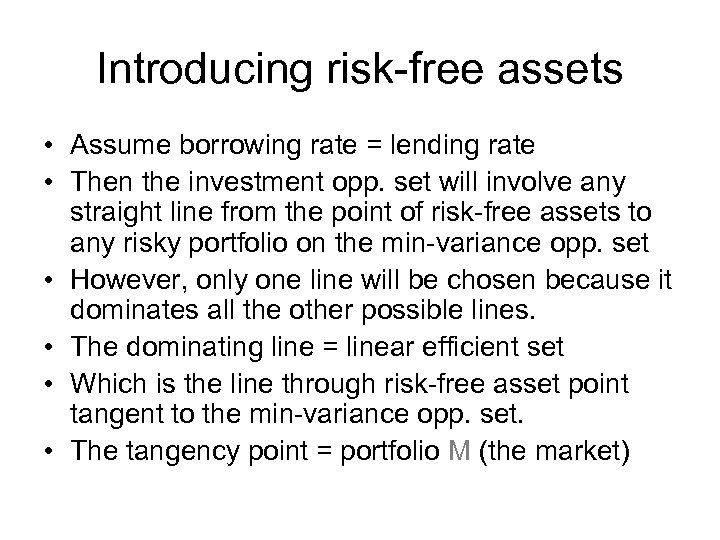

Introducing risk-free assets • Assume borrowing rate = lending rate • Then the investment opp. set will involve any straight line from the point of risk-free assets to any risky portfolio on the min-variance opp. set • However, only one line will be chosen because it dominates all the other possible lines. • The dominating line = linear efficient set • Which is the line through risk-free asset point tangent to the min-variance opp. set. • The tangency point = portfolio M (the market)

Introducing risk-free assets • Assume borrowing rate = lending rate • Then the investment opp. set will involve any straight line from the point of risk-free assets to any risky portfolio on the min-variance opp. set • However, only one line will be chosen because it dominates all the other possible lines. • The dominating line = linear efficient set • Which is the line through risk-free asset point tangent to the min-variance opp. set. • The tangency point = portfolio M (the market)

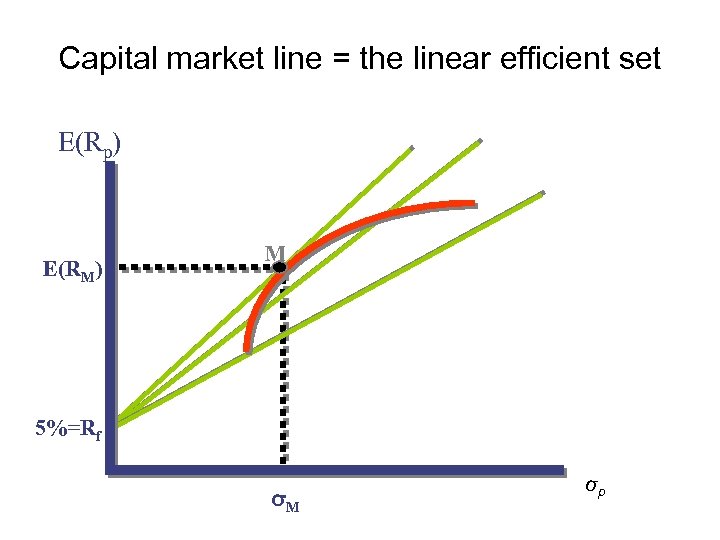

Capital market line = the linear efficient set E(Rp) E(RM) M 5%=Rf σM σp

Capital market line = the linear efficient set E(Rp) E(RM) M 5%=Rf σM σp

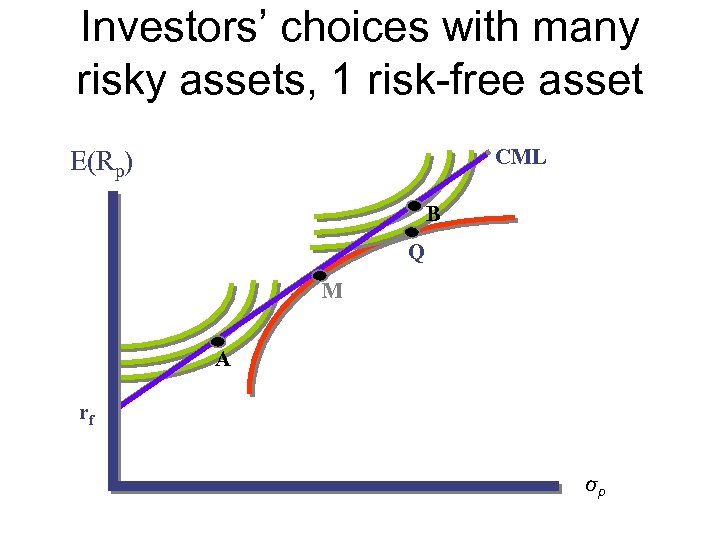

Investors’ choices with many risky assets, 1 risk-free asset CML E(Rp) B Q M A rf σp

Investors’ choices with many risky assets, 1 risk-free asset CML E(Rp) B Q M A rf σp

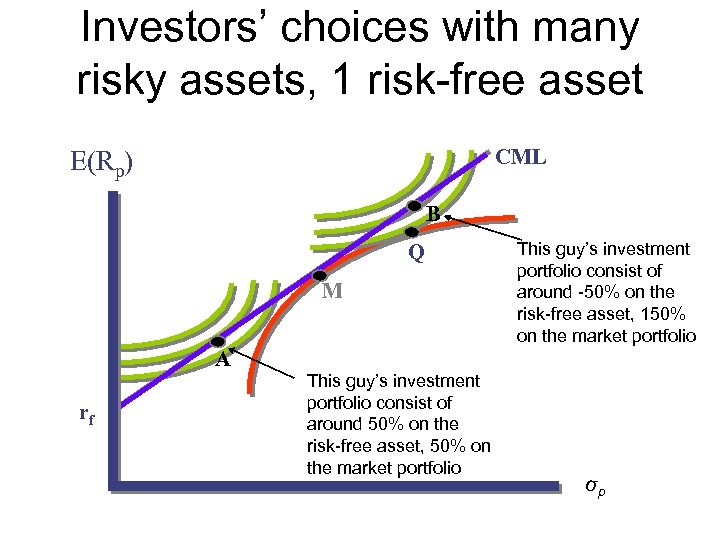

Investors’ choices with many risky assets, 1 risk-free asset CML E(Rp) B Q M This guy’s investment portfolio consist of around -50% on the risk-free asset, 150% on the market portfolio A rf This guy’s investment portfolio consist of around 50% on the risk-free asset, 50% on the market portfolio σp

Investors’ choices with many risky assets, 1 risk-free asset CML E(Rp) B Q M This guy’s investment portfolio consist of around -50% on the risk-free asset, 150% on the market portfolio A rf This guy’s investment portfolio consist of around 50% on the risk-free asset, 50% on the market portfolio σp

2 -Fund Separation • All an investor needs to know is the combination of risky assets that makes up the portfolio M as well as the risk-free asset. This is true for any investor, regardless of his degree of risk aversion. 2 -Fund Separation: • “Each investor will have his own utility-maximizing portfolio that is a combination of the risk-free asset and a portfolio (or fund) of risky assets that is determined by the line drawn from the risk-free rate of return tangent to the investor’s efficient set of risky assets. ”

2 -Fund Separation • All an investor needs to know is the combination of risky assets that makes up the portfolio M as well as the risk-free asset. This is true for any investor, regardless of his degree of risk aversion. 2 -Fund Separation: • “Each investor will have his own utility-maximizing portfolio that is a combination of the risk-free asset and a portfolio (or fund) of risky assets that is determined by the line drawn from the risk-free rate of return tangent to the investor’s efficient set of risky assets. ”