896e776b24e17711f1bdcc1d9f43c6a3.ppt

- Количество слайдов: 66

Poetry 2: Life, Birth and Death Imagery and Metaphor; Rhyme and Rhythm

Outline • General Questions • Literary Techniques: Figures of Speech, Rhyme and Rhythm • Poems • • • "Days“ “Sestina“ "Metaphors“ “Because I could not stop for Death--" “Do Not Go Gentle into that Good Night” • For Pleasure: • “Stop all the clocks, cut off the telephone” • "Ironic“ Conclusion

General Questions • Life – Sunrise, sunset, what are days for? How do you divide life into different stages? Are we always losing or gaining? • Death – What will we feel when we die? Why do poets write about death?

Life’ s Multiple Meanings an d Rhythms Sound & Sense Form & Content

![[Review] Literary Techniques (1): Rhyme 1. [usually] End Rhyme: the repetition of the final [Review] Literary Techniques (1): Rhyme 1. [usually] End Rhyme: the repetition of the final](https://present5.com/presentation/896e776b24e17711f1bdcc1d9f43c6a3/image-5.jpg)

[Review] Literary Techniques (1): Rhyme 1. [usually] End Rhyme: the repetition of the final syllable (vowel and consonant sounds) in the last words of poetic lines. Different positions: 2. internal rhyme: rhymes within the lines. Sound Patterns: 1. Consonance –repetition of consonants 2. Assonance -- repetition of vowel sounds 3. Alliteration -- repetition of the first consonant (or syllables) Different Kinds of Rhyme: Exact rhyme vs. slant (false) rhyme (“room” & “Storm”), feminine rhyme (of unstressed syllables)

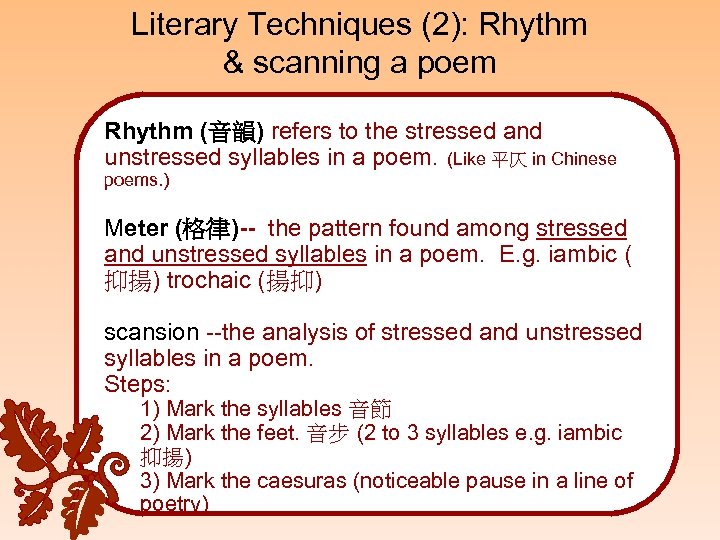

Literary Techniques (2): Rhythm & scanning a poem Rhythm (音韻) refers to the stressed and unstressed syllables in a poem. (Like 平仄 in Chinese poems. ) Meter (格律)-- the pattern found among stressed and unstressed syllables in a poem. E. g. iambic ( 抑揚) trochaic (揚抑) scansion --the analysis of stressed and unstressed syllables in a poem. Steps: 1) Mark the syllables 音節 2) Mark the feet. 音步 (2 to 3 syllables e. g. iambic 抑揚) 3) Mark the caesuras (noticeable pause in a line of poetry)

![[Review] Literary Techniques (2): Imagery (Please refer to my lecture on “Araby”) An ”image” [Review] Literary Techniques (2): Imagery (Please refer to my lecture on “Araby”) An ”image”](https://present5.com/presentation/896e776b24e17711f1bdcc1d9f43c6a3/image-7.jpg)

[Review] Literary Techniques (2): Imagery (Please refer to my lecture on “Araby”) An ”image” is -- “a word or sequence of words that refers to any sensory experience” (Kennedy and Gioia 741). An image cluster (group) -- evokes a mental image, an atmosphere, or creates symbolic meanings.

Literary Techniques (3): Figures of Speech (比喻語言) Poets often deviate from the denotative meanings of words to create fresher ideas and images. Such deviations from the literal meanings are called figures of speech or figurative language. • Example: If you giddily whisper to your classmate that the introduction to literature class is so wonderful and exciting that the class sessions seem to only last a minute, you are using a figure of speech. • Example: If you say that our textbook is your best friend, you are using a figure of speech. Used by you in • Kinds: metaphors, similes, personification, writing, hyperbole, understatement, paradox, and pun. speaking and joking.

Literary Techniques (3 -1): Metaphor A Metaphor is a type of speech that compares or equates two or more things that have something in common. A metaphor does NOT use like or as. Example: Life is a box of chocolate. You'll never know what you're going to get. A bowl of cherries. – Eat it up! More life metaphor /similes here! http: //crinago 1172. blogspot. com/2007/12/life-metaphors. html (reference)

![Literary Techniques (3 -2): Simile, etc. Simile: -- [e. g. ] Her voice was Literary Techniques (3 -2): Simile, etc. Simile: -- [e. g. ] Her voice was](https://present5.com/presentation/896e776b24e17711f1bdcc1d9f43c6a3/image-10.jpg)

Literary Techniques (3 -2): Simile, etc. Simile: -- [e. g. ] Her voice was like nails on a chalkboard. Personification: Describing an object or animal as though it had human characteristics. -- [e. g. ] Emily’s “coquettish” house in “A Rose for Emily” Apostrophe: a direct address to an imaginary object or absent person. -- [e. g. ] “A Noiseless Patient Spider” More later: sestina, villanelle, irony… (reference)

Philip Larkin

"Days" What are days for? Days are where we live. They come, they wake us Time and time over. They are to be happy in: Where can we live but days? Ah, solving that question Brings the priest and the doctor In their long coats Running over the fields.

“Days” --Questions • 1. How would you answer the question of what days are for? And the question that follows (where do we live but days? ) When would we ask such questions? Why is it an important question attracting the attention of the priest and the doctor? • 2. Why do the doctor and the priest run over “the fields”? • 3. The contrast between stanzas 1 and 2: how are they different in their line arrangements? Do you find any lines rhythmical?

“Days” • 1. What “days” means– meaning of life, of the (relentless, interesting, repetitive) passing of life. • 2. “Where do we live but days? ” Can we live elsewhere? (Is life composed of anything other than days? ) Is there a sense of the inevitable or a need for escape, for another perspective? • 3. “The priest and the doctor with their long robes” – authorities over the spiritual or the physical aspects of our lives. • 4. running over “the fields”—the fields of knowledge, of life • 5. The contrast between stanzas 1 and 2—stanza 2 – a long sentence with “solving the question” as its subject.

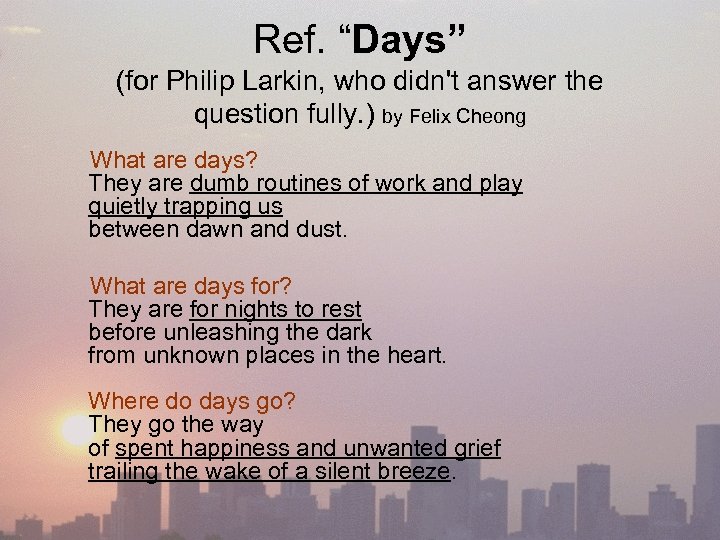

Ref. “Days” (for Philip Larkin, who didn't answer the question fully. ) by Felix Cheong What are days? They are dumb routines of work and play quietly trapping us between dawn and dust. What are days for? They are for nights to rest before unleashing the dark from unknown places in the heart. Where do days go? They go the way of spent happiness and unwanted grief trailing the wake of a silent breeze.

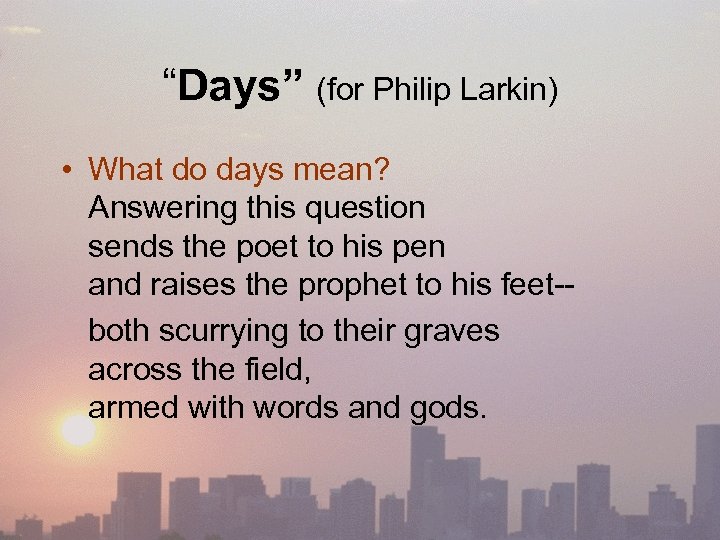

“Days” (for Philip Larkin) • What do days mean? Answering this question sends the poet to his pen and raises the prophet to his feet- both scurrying to their graves across the field, armed with words and gods.

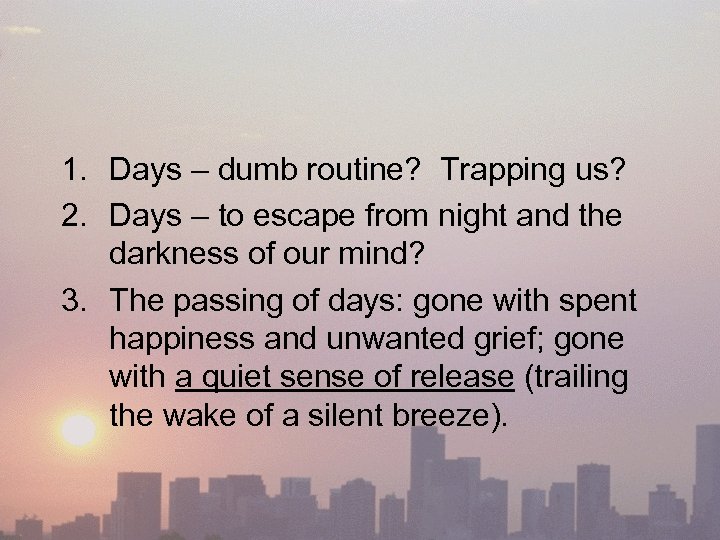

1. Days – dumb routine? Trapping us? 2. Days – to escape from night and the darkness of our mind? 3. The passing of days: gone with spent happiness and unwanted grief; gone with a quiet sense of release (trailing the wake of a silent breeze).

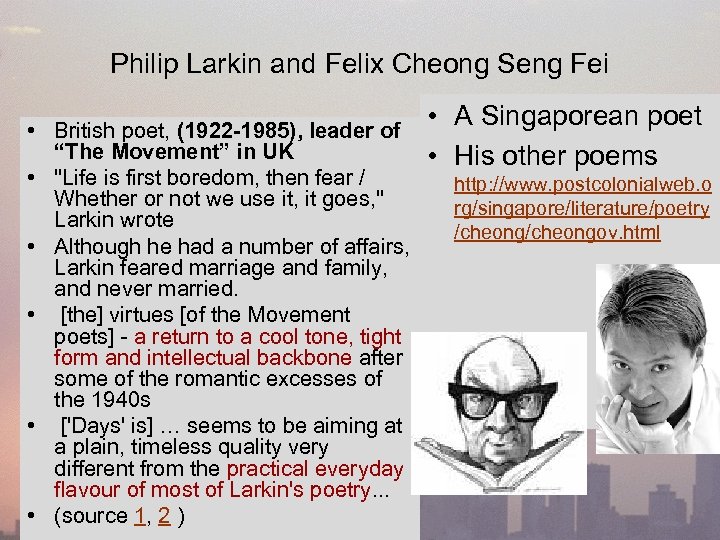

Philip Larkin and Felix Cheong Seng Fei • British poet, (1922 -1985), leader of “The Movement” in UK • "Life is first boredom, then fear / Whether or not we use it, it goes, " Larkin wrote • Although he had a number of affairs, Larkin feared marriage and family, and never married. • [the] virtues [of the Movement poets] - a return to a cool tone, tight form and intellectual backbone after some of the romantic excesses of the 1940 s • ['Days' is] … seems to be aiming at a plain, timeless quality very different from the practical everyday flavour of most of Larkin's poetry. . . • (source 1, 2 ) • A Singaporean poet • His other poems http: //www. postcolonialweb. o rg/singapore/literature/poetry /cheongov. html

Questions for you … • Compare the two poem, which do you like better? What’s the difference between feeling trapped in our days, and happily living in our days? Why (and in what situations) do we feel in one way or another? • What does routine mean for you? And the different types of people (doctors, priests, poets and prophets) mentioned in the two poems?

Elizabeth Bishop

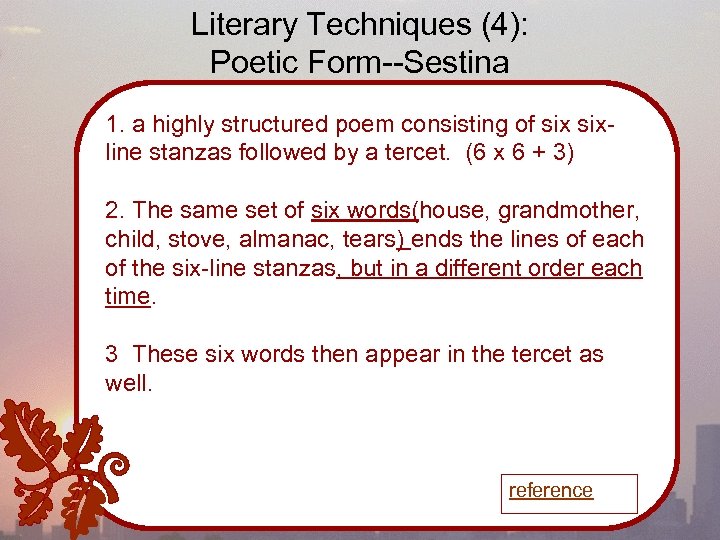

Literary Techniques (4): Poetic Form--Sestina 1. a highly structured poem consisting of sixline stanzas followed by a tercet. (6 x 6 + 3) 2. The same set of six words(house, grandmother, child, stove, almanac, tears) ends the lines of each of the six-line stanzas, but in a different order each time. 3 These six words then appear in the tercet as well. reference

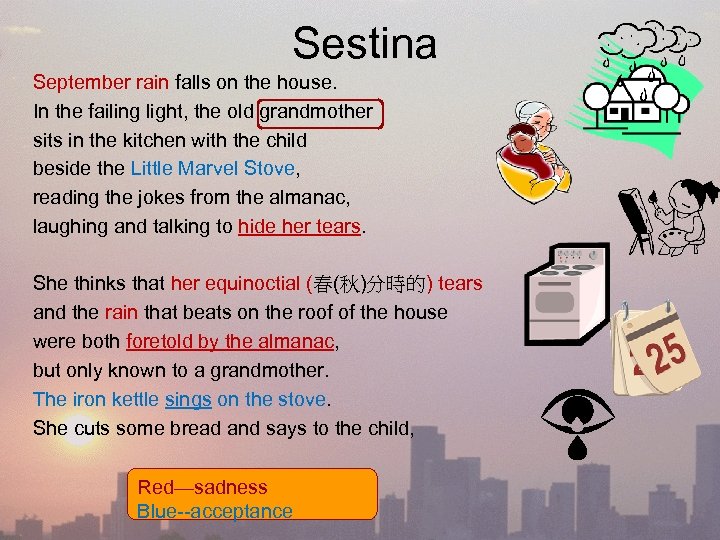

Sestina September rain falls on the house. In the failing light, the old grandmother sits in the kitchen with the child beside the Little Marvel Stove, reading the jokes from the almanac, laughing and talking to hide her tears. She thinks that her equinoctial (春(秋)分時的) tears and the rain that beats on the roof of the house were both foretold by the almanac, but only known to a grandmother. The iron kettle sings on the stove. She cuts some bread and says to the child, Red—sadness Blue--acceptance

Sestina It's time for tea now; but the child is watching the teakettle's small hard tears dance like mad on the hot black stove, the way the rain must dance on the house. Tidying up, the old grandmother hangs up the clever almanac on its string. Birdlike, the almanac hovers half open above the child, hovers above the old grandmother and her teacup full of dark brown tears. She shivers and says she thinks the house feels chilly, and puts more wood in the stove.

Sestina It was to be, says the Marvel Stove. I know what I know, says the almanac. With crayons the child draws a rigid house and a winding pathway. Then the child puts in a man with buttons like tears and shows it proudly to the grandmother. But secretly, while the grandmother busies herself about the stove, the little moons fall down like tears from between the pages of the almanac into the flower bed the child has carefully placed in the front of the house. Time to plant tears, says the almanac. The grandmother sings to the marvelous stove and the child draws another inscrutable house.

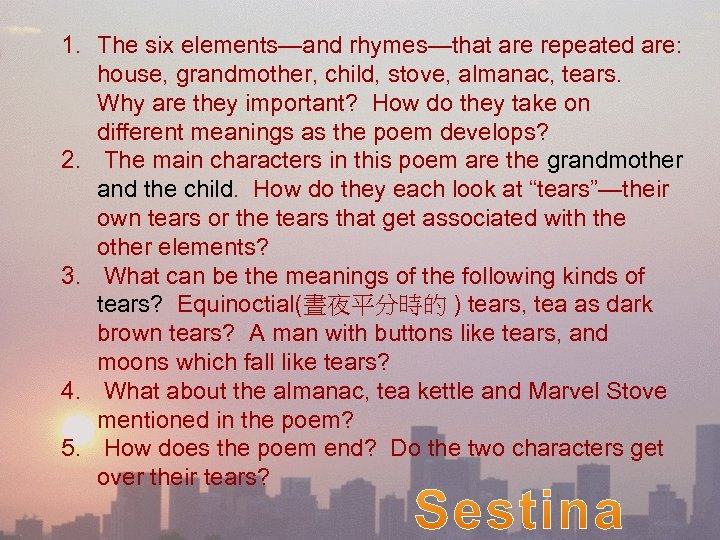

1. The six elements—and rhymes—that are repeated are: house, grandmother, child, stove, almanac, tears. Why are they important? How do they take on different meanings as the poem develops? 2. The main characters in this poem are the grandmother and the child. How do they each look at “tears”—their own tears or the tears that get associated with the other elements? 3. What can be the meanings of the following kinds of tears? Equinoctial(晝夜平分時的 ) tears, tea as dark brown tears? A man with buttons like tears, and moons which fall like tears? 4. What about the almanac, tea kettle and Marvel Stove mentioned in the poem? 5. How does the poem end? Do the two characters get over their tears?

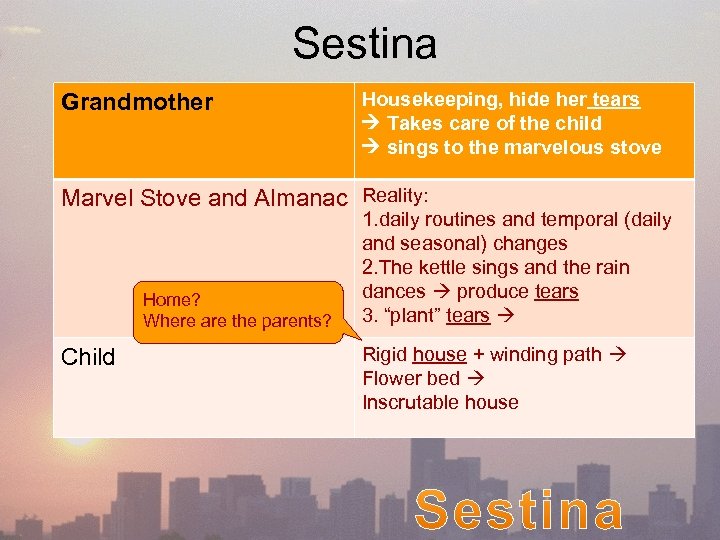

Sestina Grandmother Housekeeping, hide her tears Takes care of the child sings to the marvelous stove Marvel Stove and Almanac Reality: Home? Where are the parents? Child 1. daily routines and temporal (daily and seasonal) changes 2. The kettle sings and the rain dances produce tears 3. “plant” tears Rigid house + winding path Flower bed Inscrutable house

Elizabeth Bishop • • • born on 8 February 1911 in Worcester, Massachusetts. Before age 1 -- her father died; Age 5 -- her mother committed to a mental hospital Age 3 -6 – lived in Nova Scotia, Canada, with her mother's parents Age 7 -- taken in by her father's family in Worcester and Boston. (source) • A life of displacement: she moved to Brazil in 1951; moved back to the US after her girlfriend committed suicide. • “In the Village” about her mother’s scream • “A scream, the echo of a scream, hangs over that Nova Scotian village. No one hears it; it hangs there forever, a slight stain in those pure blue skies. . The scream hang like that, unheard, in memory—in the past, in the present, and those years between. It was not even loud to begin with, perhaps. It just came to live there, forever—not loud, just alive forever. Its pitch would be the pitch of my village. (source)

Questions for you … • Do you think that the poem is a sad story or a story of survival? • When we deal with a loss or other kinds of trauma, how can daily routine, chores (housekeeping, for instance), and actions such as painting and writing help?

METAPHORS Sylvia Plath

Metaphors Sylvia Plath (1960) I'm a riddle in nine syllables, An elephant, a ponderous house, A melon strolling on two tendrils. O red fruit, ivory, fine timbers! This loaf's big with its yeasty rising. Money's new-minted in this fat purse. I‘m a means, a stage, a cow in calf. (懷孕的母牛) I've eaten a bag of green apples, Boarded the train there's no getting off.

Metaphors Sylvia Plath (1960) • What fact about the speaker do all of the metaphors in this poem refer to? At which point did you realize that they are about her pregnancy? • Why does the speaker in line one say that she is a riddle? Why nine syllables? (Note: the poem has nine lines, why? ) • Metaphors: How do the metaphors suggest what the speaker feel about her situation? Try to sort out the different kinds of metaphors. • Explain the final line of the poem. What do you think of her tone--full of expectation, or with resignation? Do you agree with the speaker? Have you ever been on "a train there's no getting off"?

Metaphors Sylvia Plath (1960) • A Pregnant woman = riddle = Metaphors: – Physical: Large and eating: An elephant, a ponderous house, a melon strolling on two tendrils. (a loaf , fat purse, a cow, eaten a bag of green apples) – Serving as a house: red fruit(biblical allusion to "fruit of thy womb“), ivory, fine timbers – Productive (child, money): , money new-minted, a cow in calf, fat purse – Serving as a means to an end: a means, a stage, a cow in calf – Metaphysical -- The unknown: a riddle, boarded the train there's no getting off – But then is the riddle really solved or fully understood?

Sylvia Plath (1932 -1963) • Suffered from depression and attempted suicide once after her trip to NY, where she served as a ``guest editor'' at Mademoiselle Magazine one summer in her junior year. • Married Ted Hughes (a famous American poet) and then struggled between housework and her need to compose poetry; • Divorced by Hughes • Committed suicide by throwing her head into a gas stove.

The Bulge by George Johnston Another Poem on pregnancy, seen more in terms of products than process. Nobody knows what‘s growing in Bridget. Nobody knows whose is. What’s more, maybe a beauty queen Maybe a midget, maybe a braided bull(警 察) to stand by the door Lovely full Bridget Her eyes are figs; Her belly's an ocean heaving with fish; Her hair's a barn yard with chickens and pigs; Her outside is a banquet; Her tongue is a dish. Something enormous is bulging in Bridget: A milkman, a postman, a sugar stick, a slop, An old maid, a bad maid, a dull head, a fidget. Multiple sweet Bridget, What will she draw? http: //www. nfb. ca/film/poets_on_film_no_1 6: 00

Questions for you … • What do you think about pregnant women? Do you agree with either of the two descriptions of pregnancy? • Can you try to realize each or some of the metaphors by providing a context for its story to take place? For instance, when is a pregnant woman seen as “fine timbers” or fat purse?

Because I could not stop for Death Emily Dickinson

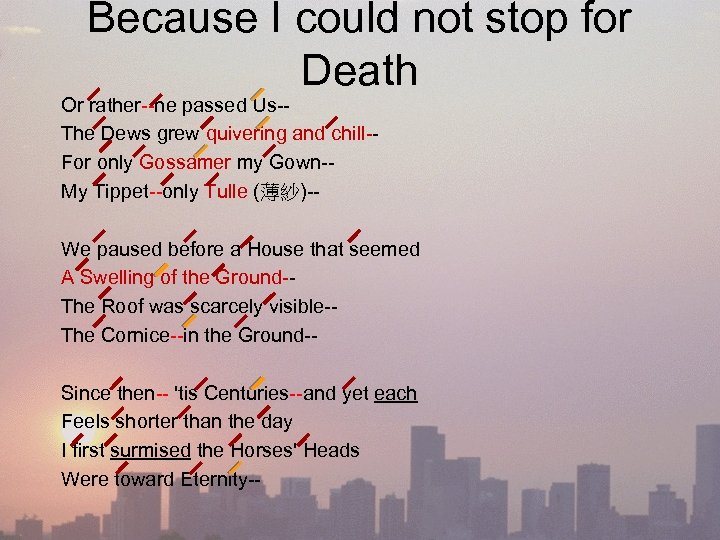

Because I could not stop for Death-- He kindly stopped for me-- The carriage held but just ourselves-- And Immortality. Personified as a gentleman We slowly drove--he knew no haste, And I had put away My labor, and my leisure too, For His Civility– Symbolic of We passed the school, where children strove 1. Learning At Recess--in the Ring-- 2. Harvesting We passed the Fields of Gazing Grain-- 3. aging We passed the Setting Sun--

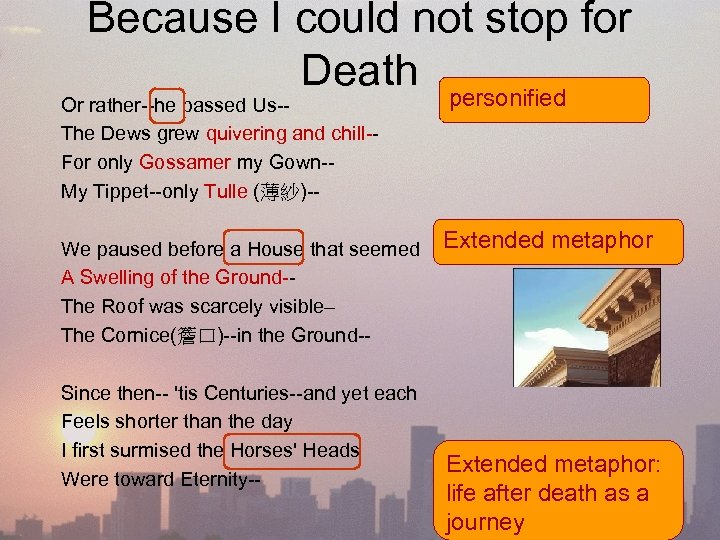

Because I could not stop for Death personified Or rather--he passed Us-- The Dews grew quivering and chill-- For only Gossamer my Gown-- My Tippet--only Tulle (薄紗)-- We paused before a House that seemed A Swelling of the Ground-- The Roof was scarcely visible– The Cornice(簷口)--in the Ground-- Since then-- 'tis Centuries--and yet each Feels shorter than the day I first surmised the Horses' Heads Were toward Eternity-- Extended metaphor: life after death as a journey

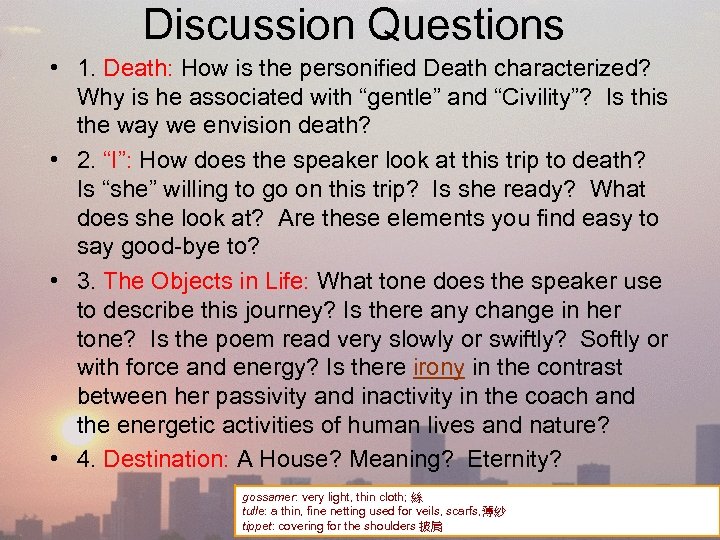

Discussion Questions • 1. Death: How is the personified Death characterized? Why is he associated with “gentle” and “Civility”? Is this the way we envision death? • 2. “I”: How does the speaker look at this trip to death? Is “she” willing to go on this trip? Is she ready? What does she look at? Are these elements you find easy to say good-bye to? • 3. The Objects in Life: What tone does the speaker use to describe this journey? Is there any change in her tone? Is the poem read very slowly or swiftly? Softly or with force and energy? Is there irony in the contrast between her passivity and inactivity in the coach and the energetic activities of human lives and nature? • 4. Destination: A House? Meaning? Eternity? gossamer: very light, thin cloth; 絲 tulle: a thin, fine netting used for veils, scarfs, 薄紗 tippet: covering for the shoulders 披肩

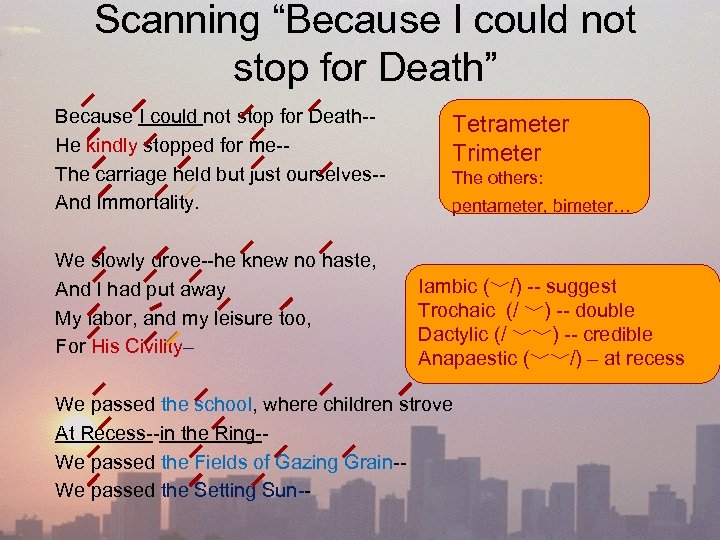

Scanning “Because I could not stop for Death” Because I could not stop for Death-- He kindly stopped for me-- The carriage held but just ourselves-- And Immortality. Tetrameter Trimeter We slowly drove--he knew no haste, And I had put away My labor, and my leisure too, For His Civility– The others: pentameter, bimeter… Iambic (﹀/) -- suggest Trochaic (/ ﹀) -- double Dactylic (/ ﹀﹀) -- credible Anapaestic (﹀﹀/) – at recess We passed the school, where children strove At Recess--in the Ring-- We passed the Fields of Gazing Grain-- We passed the Setting Sun--

Because I could not stop for Death Or rather--he passed Us-- The Dews grew quivering and chill-- For only Gossamer my Gown-- My Tippet--only Tulle (薄紗)-- We paused before a House that seemed A Swelling of the Ground-- The Roof was scarcely visible-- The Cornice--in the Ground-- Since then-- 'tis Centuries--and yet each Feels shorter than the day I first surmised the Horses' Heads Were toward Eternity--

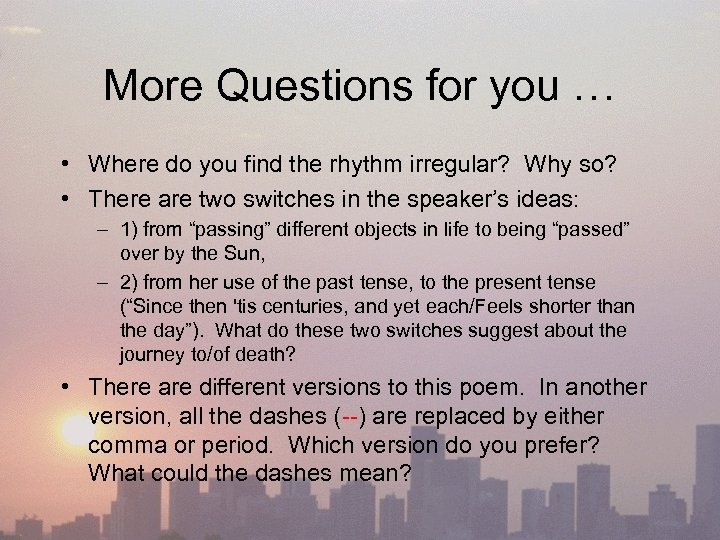

More Questions for you … • Where do you find the rhythm irregular? Why so? • There are two switches in the speaker’s ideas: – 1) from “passing” different objects in life to being “passed” over by the Sun, – 2) from her use of the past tense, to the present tense (“Since then 'tis centuries, and yet each/Feels shorter than the day”). What do these two switches suggest about the journey to/of death? • There are different versions to this poem. In another version, all the dashes (--) are replaced by either comma or period. Which version do you prefer? What could the dashes mean?

Because I could not stop for Death • Reluctance about death; Death (or what comes after death) is hard to know. • Main Ideas: – The speaker is missing the life she has to leave behind; – The world after death is cold, lonely and boring. – She realizes what eternity is only centuries later, but this eternity (the life behind time) seems quite bland uneventful. • Sound and Sense: – The regularity of the poem suggests her apparent readiness to go with death, while the pauses reflect her uncertainty and hesitation about the ideas she is to present.

Do not go gentle into that good night Dylan Thomas

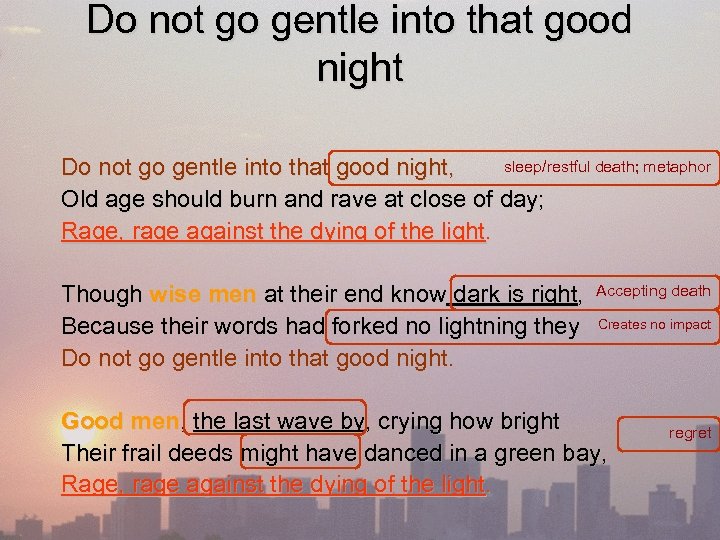

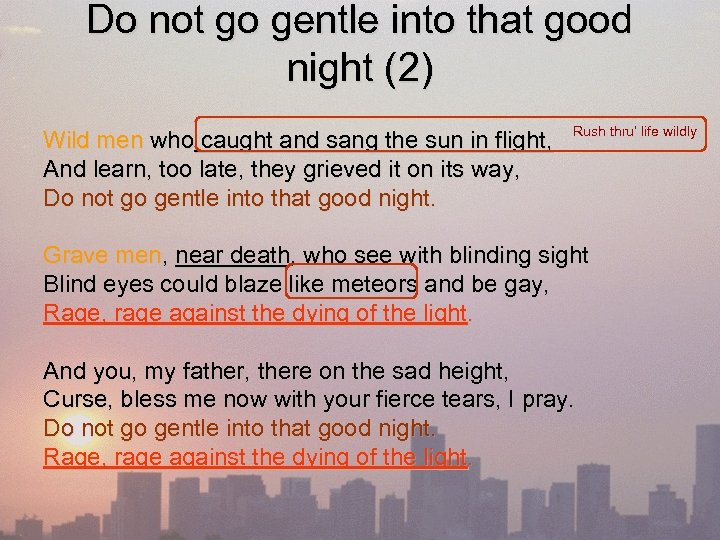

Do not go gentle into that good night sleep/restful death; metaphor Do not go gentle into that good night, Old age should burn and rave at close of day; Rage, rage against the dying of the light. Though wise men at their end know dark is right, Accepting death Because their words had forked no lightning they Creates no impact Do not go gentle into that good night. Good men, the last wave by, crying how bright Their frail deeds might have danced in a green bay, Rage, rage against the dying of the light. regret

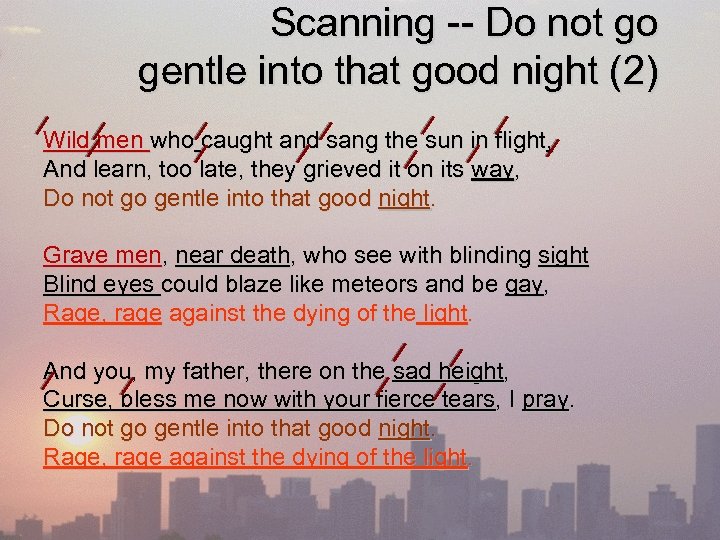

Do not go gentle into that good night (2) Wild men who caught and sang the sun in flight, And learn, too late, they grieved it on its way, Do not go gentle into that good night. Rush thru’ life wildly Grave men, near death, who see with blinding sight Blind eyes could blaze like meteors and be gay, Rage, rage against the dying of the light. And you, my father, there on the sad height, Curse, bless me now with your fierce tears, I pray. Do not go gentle into that good night. Rage, rage against the dying of the light.

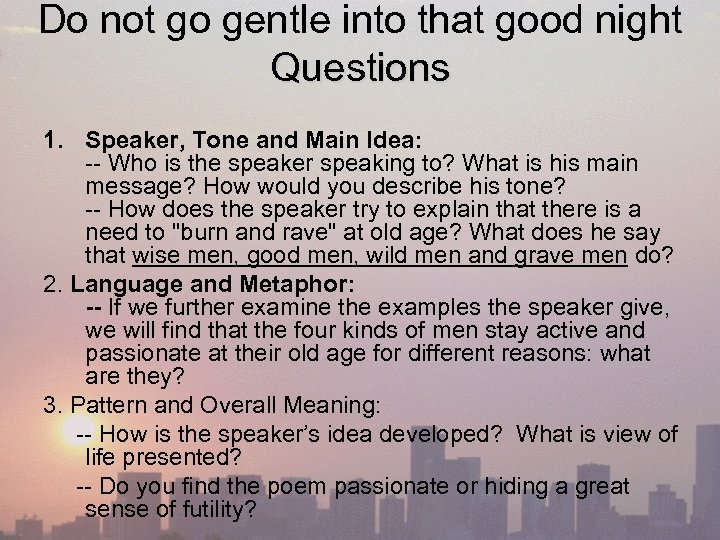

Do not go gentle into that good night Questions 1. Speaker, Tone and Main Idea: -- Who is the speaker speaking to? What is his main message? How would you describe his tone? -- How does the speaker try to explain that there is a need to "burn and rave" at old age? What does he say that wise men, good men, wild men and grave men do? 2. Language and Metaphor: 2. -- If we further examine the examples the speaker give, we will find that the four kinds of men stay active and passionate at their old age for different reasons: what are they? 3. Pattern and Overall Meaning: -- How is the speaker’s idea developed? What is view of life presented? -- Do you find the poem passionate or hiding a great sense of futility?

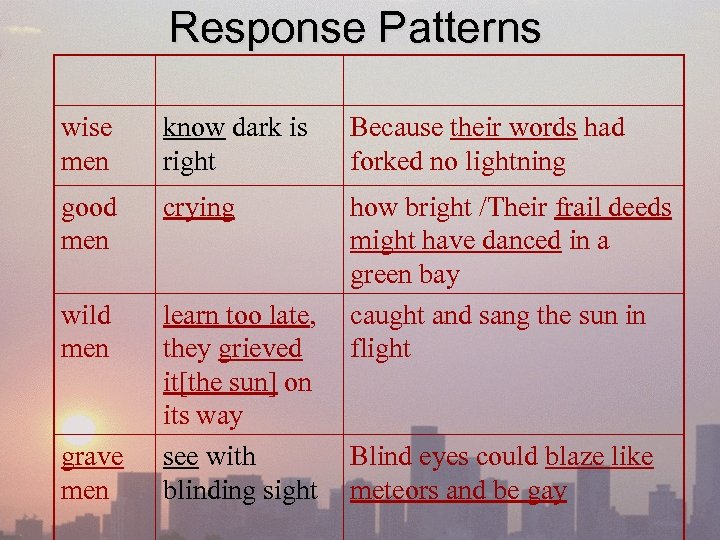

Response Patterns wise men know dark is right Because their words had forked no lightning good men crying wild men learn too late, they grieved it[the sun] on its way see with blinding sight how bright /Their frail deeds might have danced in a green bay caught and sang the sun in flight grave men Blind eyes could blaze like meteors and be gay

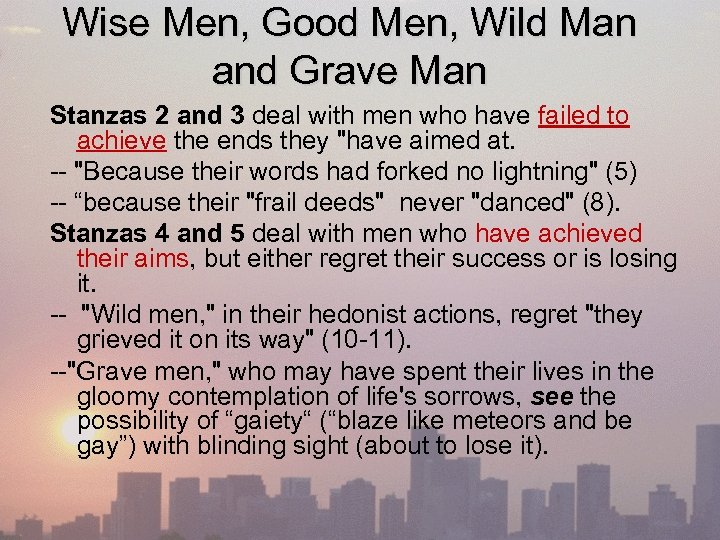

Wise Men, Good Men, Wild Man and Grave Man Stanzas 2 and 3 deal with men who have failed to achieve the ends they "have aimed at. -- "Because their words had forked no lightning" (5) -- “because their "frail deeds" never "danced" (8). Stanzas 4 and 5 deal with men who have achieved their aims, but either regret their success or is losing it. -- "Wild men, " in their hedonist actions, regret "they grieved it on its way" (10 -11). --"Grave men, " who may have spent their lives in the gloomy contemplation of life's sorrows, see the possibility of “gaiety“ (“blaze like meteors and be gay”) with blinding sight (about to lose it).

Father and Son: use of oxymoron And you, my father, there on the sad height, Curse, bless me now with your fierce tears, I pray. Do not go gentle into that good night. power Rage, rage against the dying of the light. futility

Dylan Thomas • Born in Wales. Wrote several poems on his birthdays which are to do with death. E. g. “THE FORCE THAT THROUGH THE GREEN FUSE DRIVES THE FLOWER” • Thomas: under strong influence of his father. • "the only person I can't show the little enclosed poem to is, of course, my father, who doesn't know he's dying" (Letters 359)

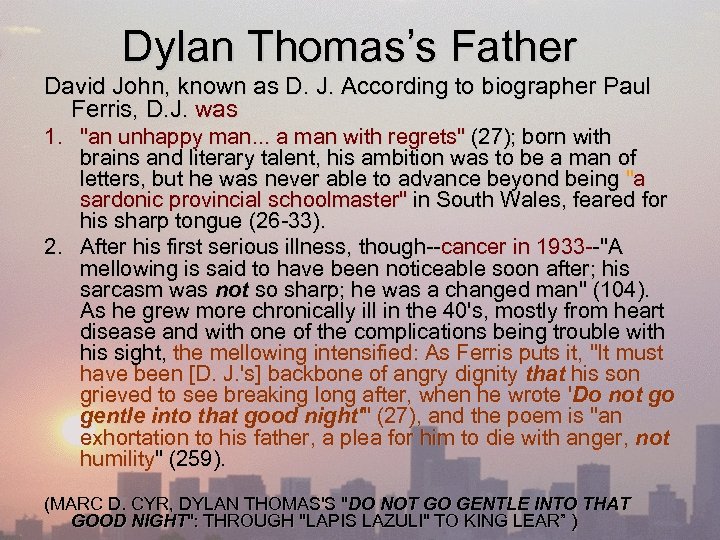

Dylan Thomas’s Father David John, known as D. J. According to biographer Paul Ferris, D. J. was 1. "an unhappy man. . . a man with regrets" (27); born with brains and literary talent, his ambition was to be a man of letters, but he was never able to advance beyond being "a sardonic provincial schoolmaster" in South Wales, feared for his sharp tongue (26 -33). 2. After his first serious illness, though--cancer in 1933 --"A mellowing is said to have been noticeable soon after; his sarcasm was not so sharp; he was a changed man" (104). As he grew more chronically ill in the 40's, mostly from heart disease and with one of the complications being trouble with his sight, the mellowing intensified: As Ferris puts it, "It must have been [D. J. 's] backbone of angry dignity that his son grieved to see breaking long after, when he wrote 'Do not go gentle into that good night'" (27), and the poem is "an exhortation to his father, a plea for him to die with anger, not humility" (259). (MARC D. CYR, DYLAN THOMAS'S "DO NOT GO GENTLE INTO THAT GOOD NIGHT": THROUGH "LAPIS LAZULI" TO KING LEAR” )

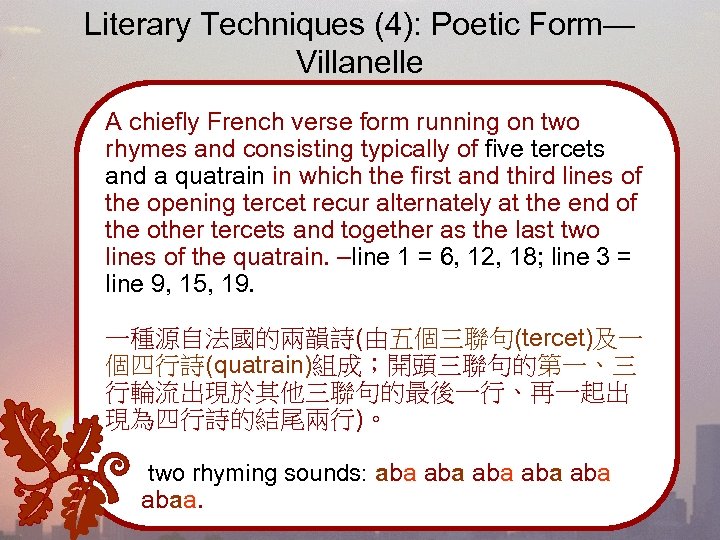

Literary Techniques (4): Poetic Form— Villanelle A chiefly French verse form running on two rhymes and consisting typically of five tercets and a quatrain in which the first and third lines of the opening tercet recur alternately at the end of the other tercets and together as the last two lines of the quatrain. –line 1 = 6, 12, 18; line 3 = line 9, 15, 19. 一種源自法國的兩韻詩(由五個三聯句(tercet)及一 個四行詩(quatrain)組成;開頭三聯句的第一、三 行輪流出現於其他三聯句的最後一行、再一起出 現為四行詩的結尾兩行)。 two rhyming sounds: aba aba abaa.

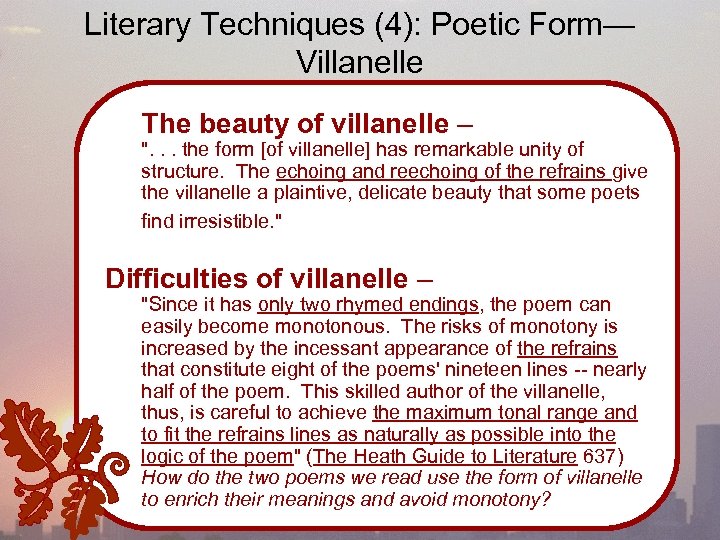

Literary Techniques (4): Poetic Form— Villanelle The beauty of villanelle – ". . . the form [of villanelle] has remarkable unity of structure. The echoing and reechoing of the refrains give the villanelle a plaintive, delicate beauty that some poets find irresistible. " Difficulties of villanelle – "Since it has only two rhymed endings, the poem can easily become monotonous. The risks of monotony is increased by the incessant appearance of the refrains that constitute eight of the poems' nineteen lines -- nearly half of the poem. This skilled author of the villanelle, thus, is careful to achieve the maximum tonal range and to fit the refrains lines as naturally as possible into the logic of the poem" (The Heath Guide to Literature 637) How do the two poems we read use the form of villanelle to enrich their meanings and avoid monotony?

Sound & Sense -- Do not go gentle into that good night spondee Do not go gentle into that good night, Old age should burn and rave at close of day; Rage, rage against the dying of the light. command Though wise men at their end know dark is right, Because their words had forked no lightning they Do not go gentle into that good night. action Good men, the last wave by, crying how bright Their frail deeds might have danced in a green bay, Rage, rage against the dying of the light.

Scanning -- Do not go gentle into that good night (2) Wild men who caught and sang the sun in flight, And learn, too late, they grieved it on its way, Do not go gentle into that good night. Grave men, near death, who see with blinding sight Blind eyes could blaze like meteors and be gay, Rage, rage against the dying of the light. And you, my father, there on the sad height, Curse, bless me now with your fierce tears, I pray. Do not go gentle into that good night. Rage, rage against the dying of the light.

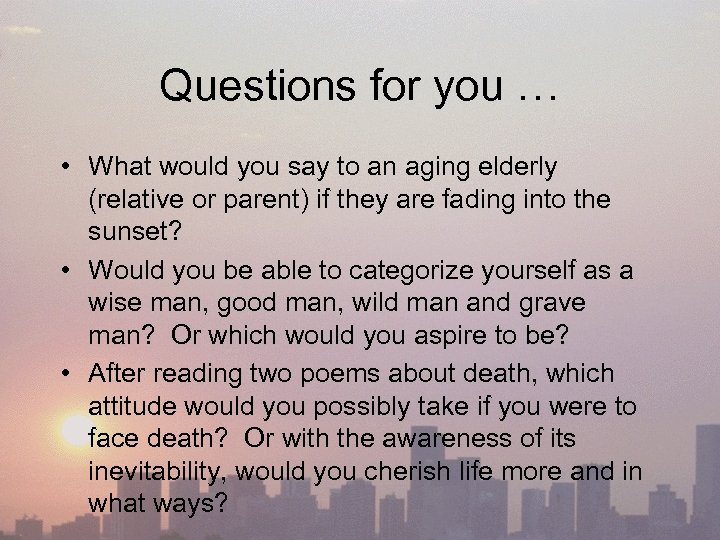

Questions for you … • What would you say to an aging elderly (relative or parent) if they are fading into the sunset? • Would you be able to categorize yourself as a wise man, good man, wild man and grave man? Or which would you aspire to be? • After reading two poems about death, which attitude would you possibly take if you were to face death? Or with the awareness of its inevitability, would you cherish life more and in what ways?

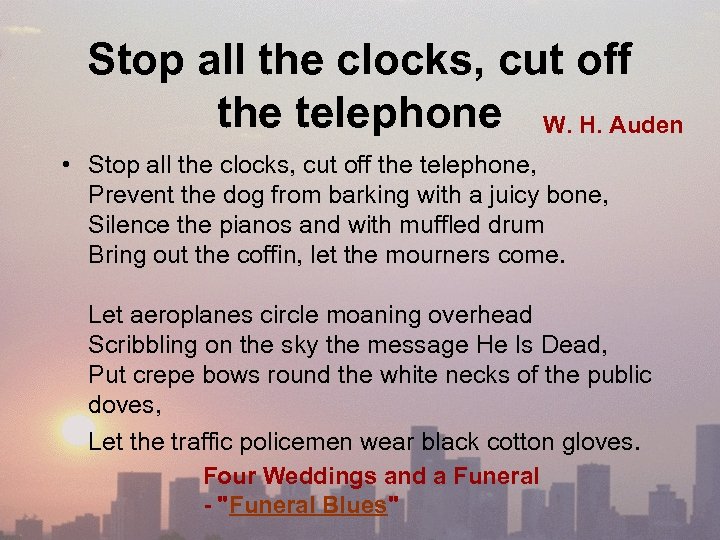

Stop all the clocks, cut off the telephone W. H. Auden • Stop all the clocks, cut off the telephone, Prevent the dog from barking with a juicy bone, Silence the pianos and with muffled drum Bring out the coffin, let the mourners come. Let aeroplanes circle moaning overhead Scribbling on the sky the message He Is Dead, Put crepe bows round the white necks of the public doves, Let the traffic policemen wear black cotton gloves. Four Weddings and a Funeral - "Funeral Blues"

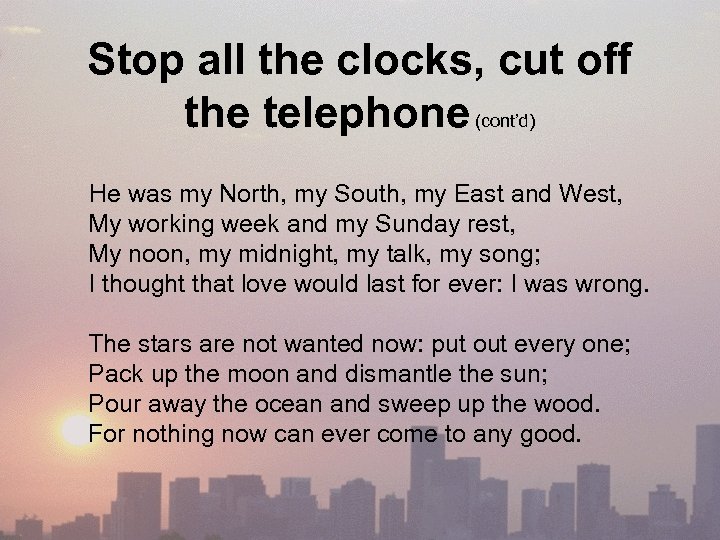

Stop all the clocks, cut off the telephone (cont’d) He was my North, my South, my East and West, My working week and my Sunday rest, My noon, my midnight, my talk, my song; I thought that love would last for ever: I was wrong. The stars are not wanted now: put out every one; Pack up the moon and dismantle the sun; Pour away the ocean and sweep up the wood. For nothing now can ever come to any good.

Moment of Sadness • One can be totally immersed in sadness, so that s/he commands all to stop and to mourn for his/her dead lover. • On the other hand, there are ways to put death in its context of life, and for us to survive this overwhelming moment of sadness.

Alanis Morissette: Ironic • ironies of life and death: won the lottery and died the next day; a death row pardon two minutes too late; Mr. Play It Safe • Twists and turns in life: you think everything's okay and everything's going right/ (the other way around) • the unfortunate? • the unlucky: a black fly in your Chardonnay; rain on your wedding day; A traffic jam when you're already late • the funny coincidence: free ride already paid; • Which do you think matters for you? • Lyrics • A comedian’s comment: she just mourns over some unfortunate things.

Your Responses? 1. A good laugh. 2. The comedian gives a “literal” definition of “irony, ” while Morissette describes the situations which one does not expect and can not help—situational irony, or the irony of fate.

Literary Techniques (5): Irony involves a contradiction. "In general, irony is the perception of a clash between appearance and reality, between seems and is, or between ought and is" (Harper Handbook). • Verbal irony: --"Saying something contrary to what it means" • "Oh, how lucky we are to have SO MANY online materials offered by the Introduction to Literature class!" you said. ” • Dramatic irony: "saying or doing something while being unaware of its ironic contrast with the whole truth. • Situational irony: "events turning to the opposite of what is expected or what should be.

Review & Conclusion Form Long and short lines “Days”—long journey or long-time searching, short actions Villanelle and Sestina Life and its constraints Metaphor Content Pregnancy, life, death

Works Cites • Kennedy, X. J. and Dana Gioia, eds. Literature: An Introduction to Fiction, Poetry, and Drama. 7 th ed. New York: Longman, 1999. • Literary Terms: Power. Point Presentation <http: //www. clintweb. net/ctw/littermsppt. ppt>

896e776b24e17711f1bdcc1d9f43c6a3.ppt