Pneumothorax -Pneumothorax is the presence of air within

radiology_pneumothorax.ppt

- Количество слайдов: 36

Pneumothorax -Pneumothorax is the presence of air within the pleural space -Due to disruption of parietal, visceral or mediastinal pleura -May also occur from spontaneous rupture of subpleural bleb -A tension pneumothorax occurs when pleura forms a one-way flap valve -Tension pneumothorax is a medical emergency

Pneumothorax -Pneumothorax is the presence of air within the pleural space -Due to disruption of parietal, visceral or mediastinal pleura -May also occur from spontaneous rupture of subpleural bleb -A tension pneumothorax occurs when pleura forms a one-way flap valve -Tension pneumothorax is a medical emergency

pneumothorax - air leaks into the space between the chest wall and the outer tissues of the lungs. pneumomediastinum - air leaks into the mediastinum (the space in the thoracic cavity behind the sternum and between the two pleural sacs containing the lungs). pneumopericardium - air leaks into the sac surrounding the heart. pulmonary interstitial emphysema (PIE) - air leaks and becomes trapped between the alveoli, the tiny air sacs of the lungs.

pneumothorax - air leaks into the space between the chest wall and the outer tissues of the lungs. pneumomediastinum - air leaks into the mediastinum (the space in the thoracic cavity behind the sternum and between the two pleural sacs containing the lungs). pneumopericardium - air leaks into the sac surrounding the heart. pulmonary interstitial emphysema (PIE) - air leaks and becomes trapped between the alveoli, the tiny air sacs of the lungs.

Classification Spontaneous pneumothorax Primary - no identifiable pathology Secondary - underlying pulmonary disorder Catamenial Traumatic Blunt or penetrating thoracic trauma Iatrogenic Postoperative Mechanical ventilation Thoracocentesis Central venous cannulation

Classification Spontaneous pneumothorax Primary - no identifiable pathology Secondary - underlying pulmonary disorder Catamenial Traumatic Blunt or penetrating thoracic trauma Iatrogenic Postoperative Mechanical ventilation Thoracocentesis Central venous cannulation

Diseases Associated with Ptx The following diseases can be associated with pneumothorax: Chronic obstructive lung disease Asthma HIV infection PCP Necrotizing pneumonia Bronchogenic carcinoma Sarcomas metastatic to the lungs Tuberculosis Cystic fibrosis Interstitial lung diseases associated with connective tissue diseases Idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis Sarcoidosis Lymphangioleiomyomatosis Langerhans cell histiocytosis High-risk occupation (eg, diving, flying)

Diseases Associated with Ptx The following diseases can be associated with pneumothorax: Chronic obstructive lung disease Asthma HIV infection PCP Necrotizing pneumonia Bronchogenic carcinoma Sarcomas metastatic to the lungs Tuberculosis Cystic fibrosis Interstitial lung diseases associated with connective tissue diseases Idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis Sarcoidosis Lymphangioleiomyomatosis Langerhans cell histiocytosis High-risk occupation (eg, diving, flying)

Primary spontaneous pneumothorax Usually occurs in young healthy adult men 85% patients are less than 40 years old Male : female ratio is 6:1 Bilateral in 10% of cases Occurs as result of rupture of an acquired subpleural bleb Blebs have no epithelial lining and arise from rupture of the alveolar wall Apical blebs found in 85% of patients undergoing thoracotomy Frequency of spontaneous pneumothorax increases after each episode Most recurrences occur within 2 years of the initial episode

Primary spontaneous pneumothorax Usually occurs in young healthy adult men 85% patients are less than 40 years old Male : female ratio is 6:1 Bilateral in 10% of cases Occurs as result of rupture of an acquired subpleural bleb Blebs have no epithelial lining and arise from rupture of the alveolar wall Apical blebs found in 85% of patients undergoing thoracotomy Frequency of spontaneous pneumothorax increases after each episode Most recurrences occur within 2 years of the initial episode

Secondary spontaneous pneumothorax Accounts for 10-20% of spontaneous pneumothoraces can be due to: Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease with bulla formation Interstitial lung disease Primary and metastatic neoplasms Ehlers-Danlos syndrome Marfan's syndrome

Secondary spontaneous pneumothorax Accounts for 10-20% of spontaneous pneumothoraces can be due to: Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease with bulla formation Interstitial lung disease Primary and metastatic neoplasms Ehlers-Danlos syndrome Marfan's syndrome

Traumatic pneumothorax Can result from either blunt or penetrating trauma Tracheobronchial and esophageal injuries can cause both mediastinal emphysema and pneumothorax Iatrogenic pneumothorax is common Occurs after : Pneumonectomy Thoracocentesis High-pressure mechanical ventilation Subclavian venous cannulation

Traumatic pneumothorax Can result from either blunt or penetrating trauma Tracheobronchial and esophageal injuries can cause both mediastinal emphysema and pneumothorax Iatrogenic pneumothorax is common Occurs after : Pneumonectomy Thoracocentesis High-pressure mechanical ventilation Subclavian venous cannulation

Catamenial pneumothorax Catamenial pneumothorax refers to the development of pneumothorax at the time of menstruation. represents 3-6% of spontaneous pneumothorax in women. Typically, it occurs in women aged 30-40 years with a history of pelvic endometriosis (20-40%). It usually affects the right lung (90-95%) and occurs within 72 hours after the onset of menses. The recurrence rate in women receiving hormonal treatment is 50% at 1 year.

Catamenial pneumothorax Catamenial pneumothorax refers to the development of pneumothorax at the time of menstruation. represents 3-6% of spontaneous pneumothorax in women. Typically, it occurs in women aged 30-40 years with a history of pelvic endometriosis (20-40%). It usually affects the right lung (90-95%) and occurs within 72 hours after the onset of menses. The recurrence rate in women receiving hormonal treatment is 50% at 1 year.

Pneumothorax in AIDS Spontaneous pneumothorax develops in 2-6% of HIV-infected patients and is associated with P carinii pneumonia in 80% of those patients. Pneumothorax is associated with a high mortality rate in patients with HIV infection with P carinii pneumonia. Pathogenesis of the pneumothorax in this setting is the rupture of large subpleural cysts, which are associated with subpleural necrosis. Recurrent ipsilateral or contralateral pneumothorax also is common

Pneumothorax in AIDS Spontaneous pneumothorax develops in 2-6% of HIV-infected patients and is associated with P carinii pneumonia in 80% of those patients. Pneumothorax is associated with a high mortality rate in patients with HIV infection with P carinii pneumonia. Pathogenesis of the pneumothorax in this setting is the rupture of large subpleural cysts, which are associated with subpleural necrosis. Recurrent ipsilateral or contralateral pneumothorax also is common

Clinical features Predominant symptom is acute pleuritic chest pain Dyspnoea results form pulmonary compression Symptoms are proportional to the size of the pneumothorax Also depend on the degree of pulmonary reserve Physical signs include Tachypnoea Increased resonance Absent breath sounds

Clinical features Predominant symptom is acute pleuritic chest pain Dyspnoea results form pulmonary compression Symptoms are proportional to the size of the pneumothorax Also depend on the degree of pulmonary reserve Physical signs include Tachypnoea Increased resonance Absent breath sounds

Clinical features In a tension pneumothorax The patient is hypotensive with acute respiratory distress The trachea may be shifted away from the affected side Neck veins may be engorged Diagnosis can be confirmed with a chest x-ray

Clinical features In a tension pneumothorax The patient is hypotensive with acute respiratory distress The trachea may be shifted away from the affected side Neck veins may be engorged Diagnosis can be confirmed with a chest x-ray

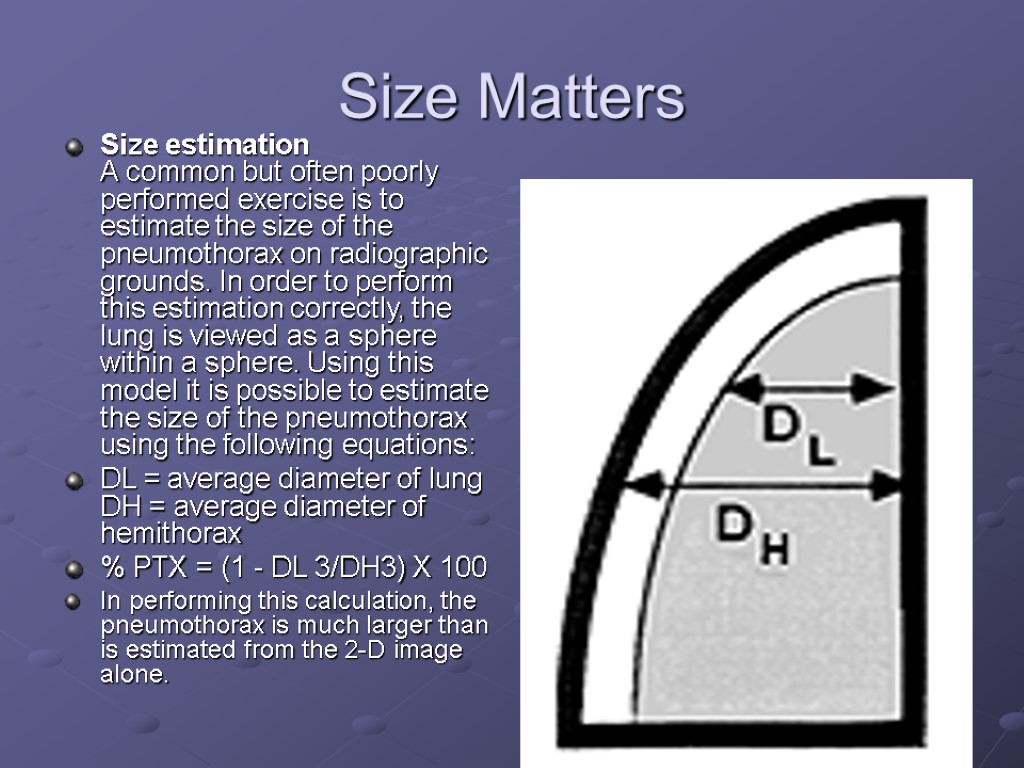

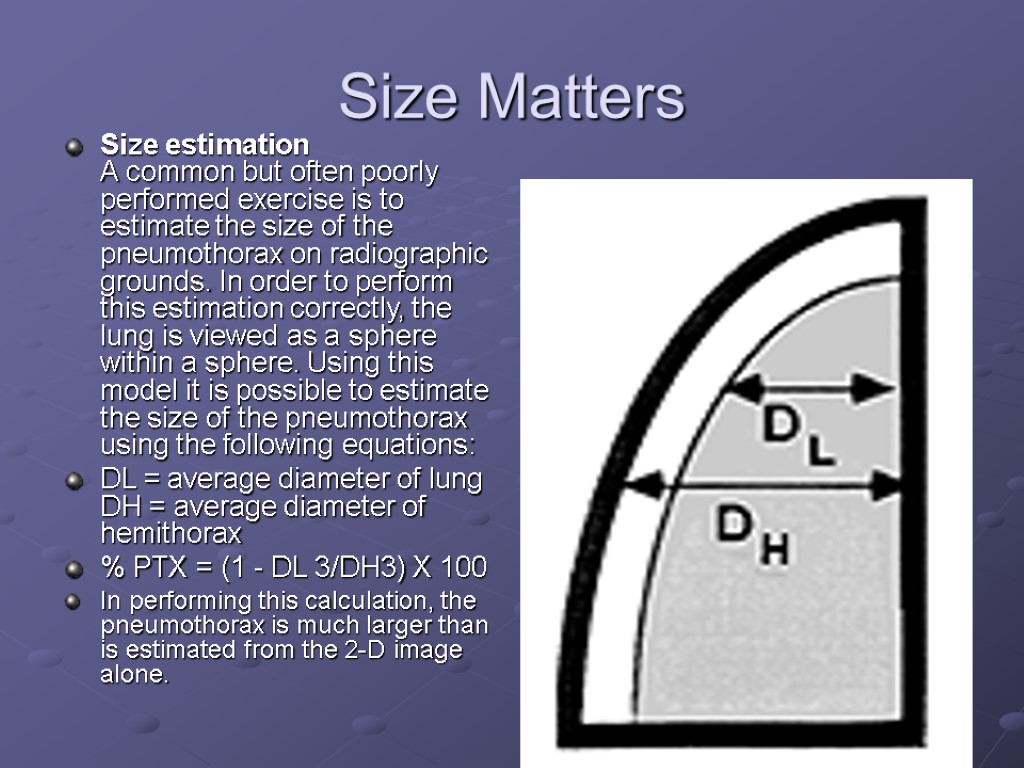

Size Matters Size estimation A common but often poorly performed exercise is to estimate the size of the pneumothorax on radiographic grounds. In order to perform this estimation correctly, the lung is viewed as a sphere within a sphere. Using this model it is possible to estimate the size of the pneumothorax using the following equations: DL = average diameter of lung DH = average diameter of hemithorax % PTX = (1 - DL 3/DH3) X 100 In performing this calculation, the pneumothorax is much larger than is estimated from the 2-D image alone.

Size Matters Size estimation A common but often poorly performed exercise is to estimate the size of the pneumothorax on radiographic grounds. In order to perform this estimation correctly, the lung is viewed as a sphere within a sphere. Using this model it is possible to estimate the size of the pneumothorax using the following equations: DL = average diameter of lung DH = average diameter of hemithorax % PTX = (1 - DL 3/DH3) X 100 In performing this calculation, the pneumothorax is much larger than is estimated from the 2-D image alone.

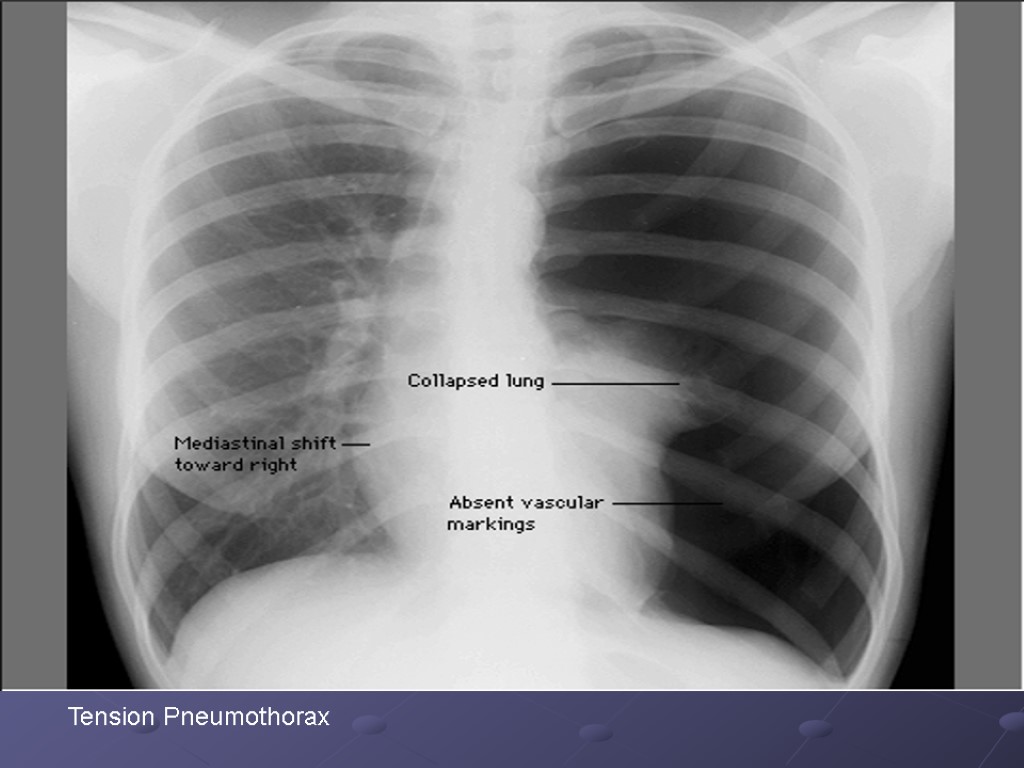

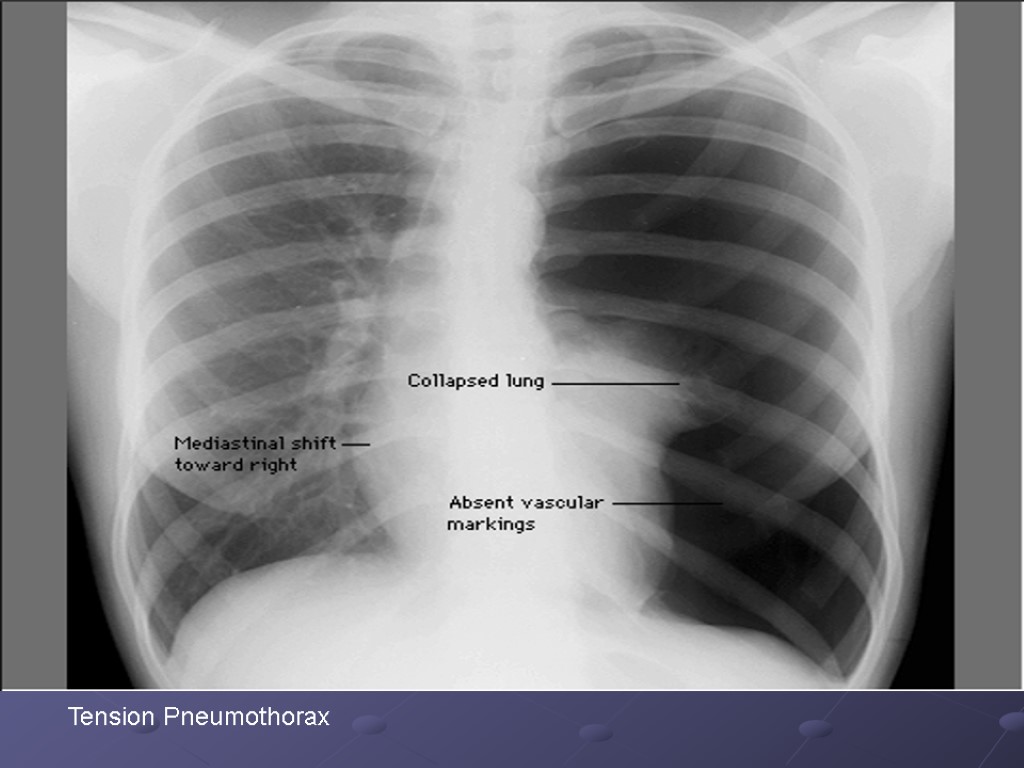

Tension Pneumothorax

Tension Pneumothorax

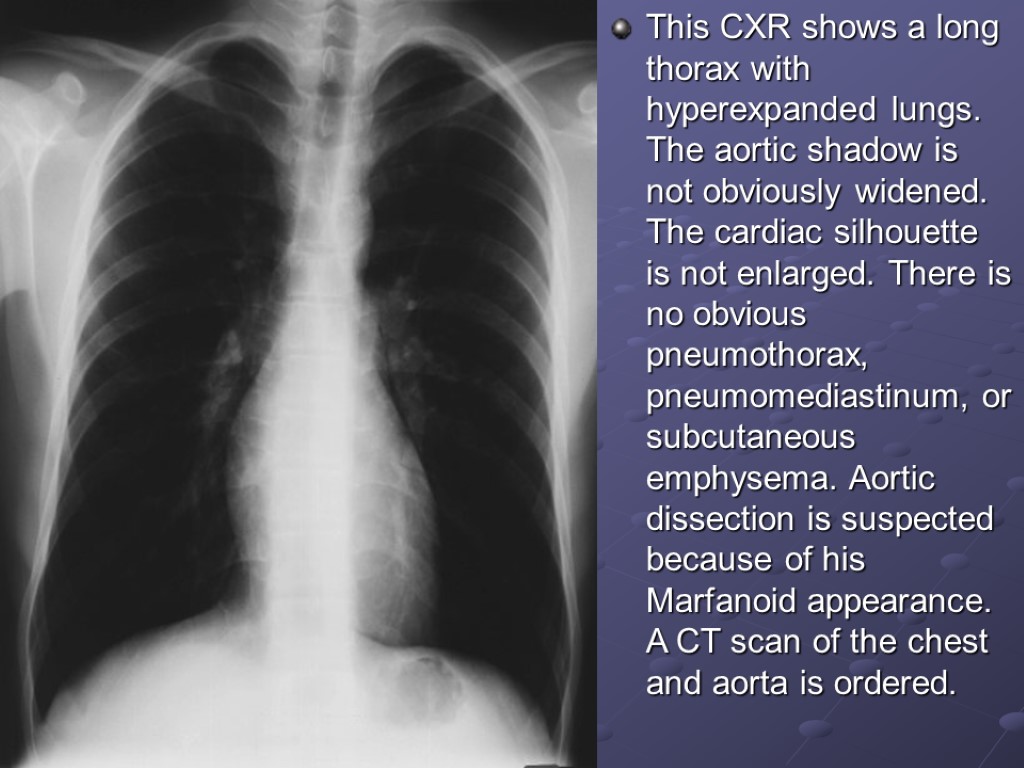

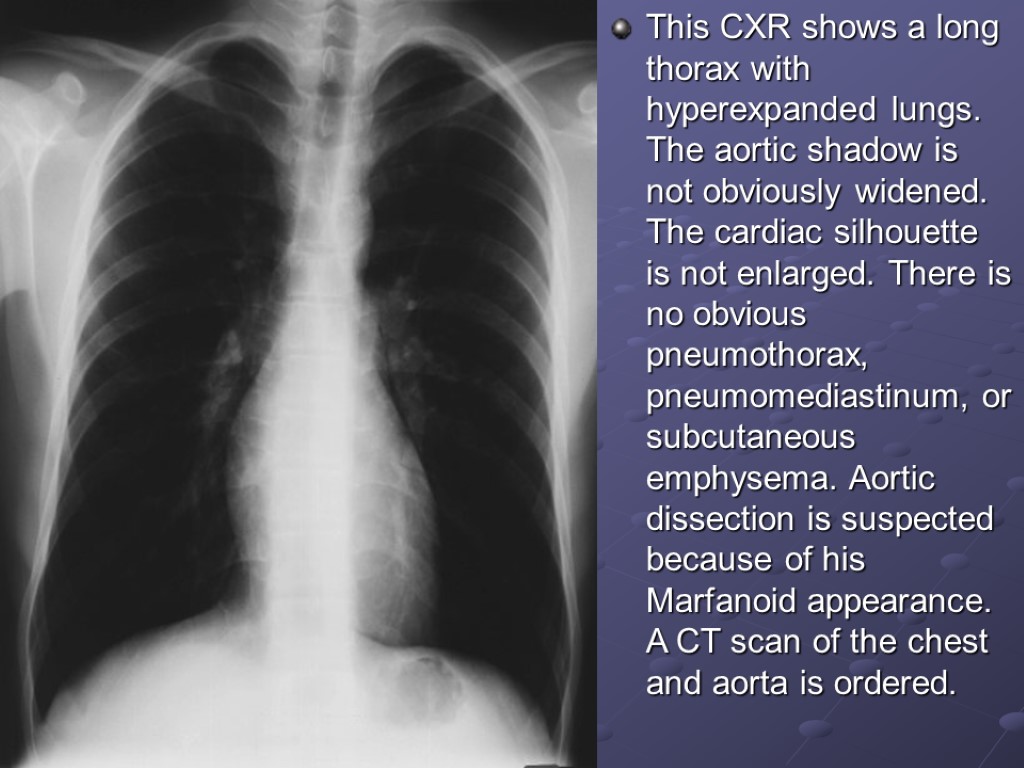

This CXR shows a long thorax with hyperexpanded lungs. The aortic shadow is not obviously widened. The cardiac silhouette is not enlarged. There is no obvious pneumothorax, pneumomediastinum, or subcutaneous emphysema. Aortic dissection is suspected because of his Marfanoid appearance. A CT scan of the chest and aorta is ordered.

This CXR shows a long thorax with hyperexpanded lungs. The aortic shadow is not obviously widened. The cardiac silhouette is not enlarged. There is no obvious pneumothorax, pneumomediastinum, or subcutaneous emphysema. Aortic dissection is suspected because of his Marfanoid appearance. A CT scan of the chest and aorta is ordered.

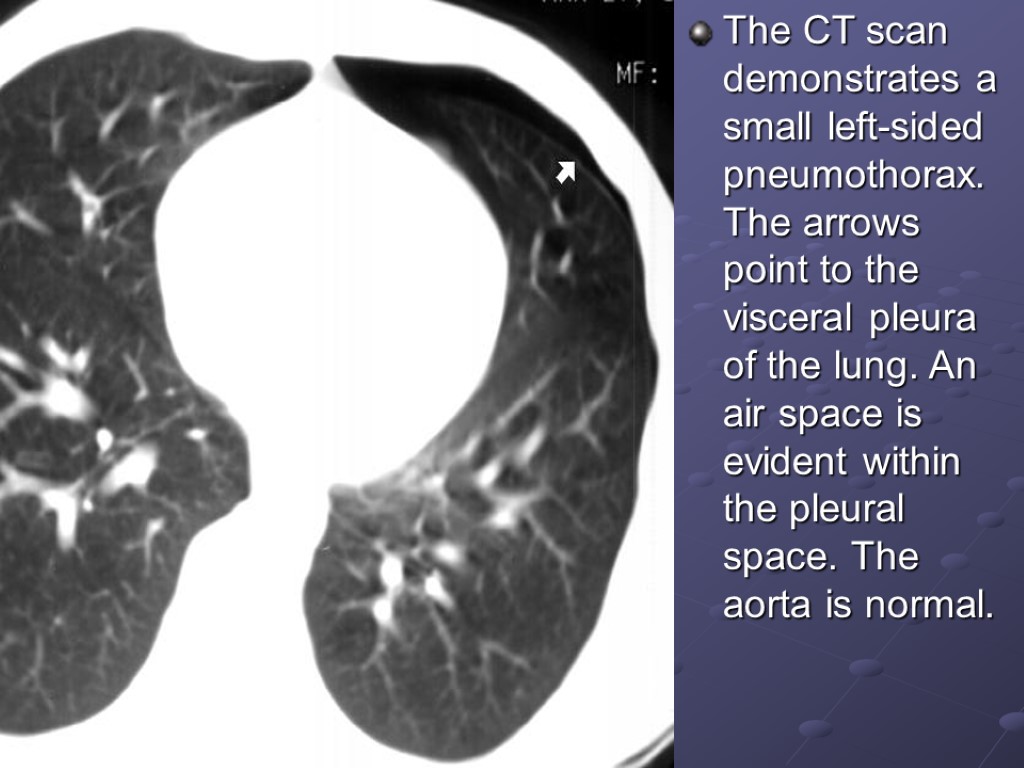

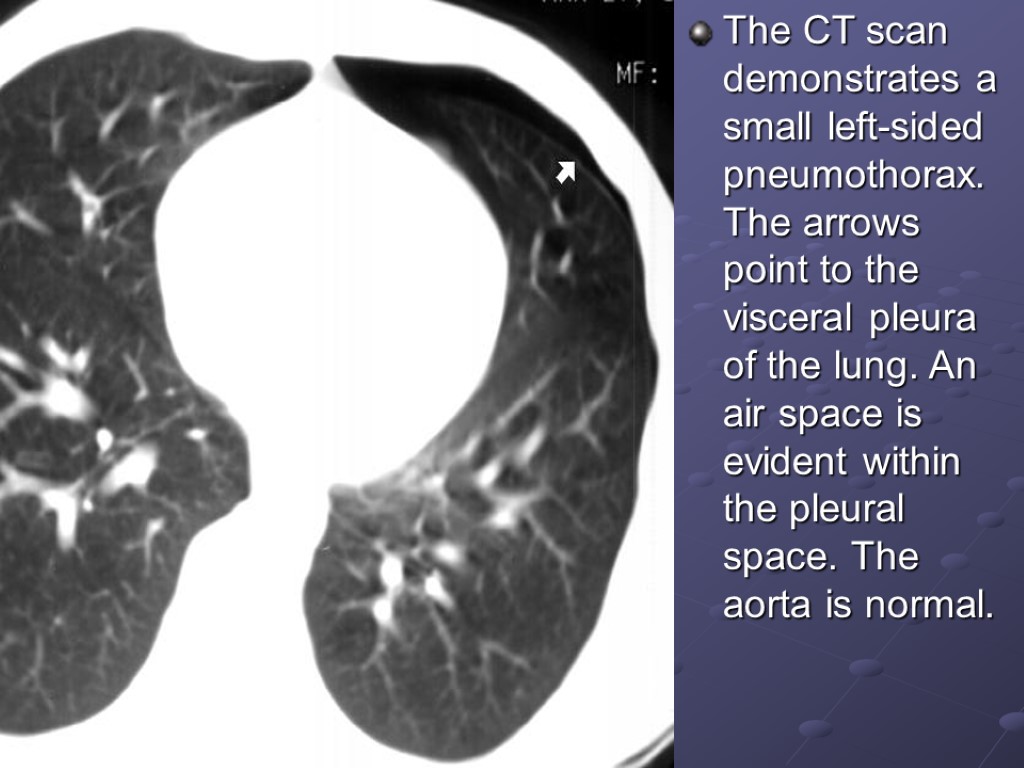

The CT scan demonstrates a small left-sided pneumothorax. The arrows point to the visceral pleura of the lung. An air space is evident within the pleural space. The aorta is normal.

The CT scan demonstrates a small left-sided pneumothorax. The arrows point to the visceral pleura of the lung. An air space is evident within the pleural space. The aorta is normal.

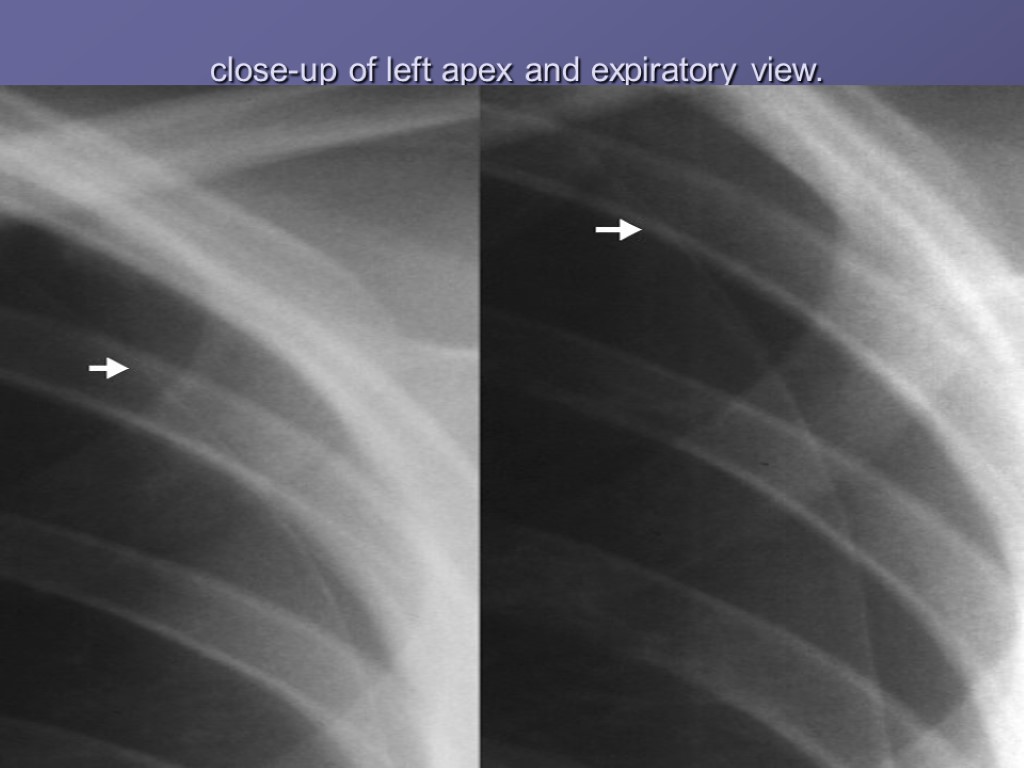

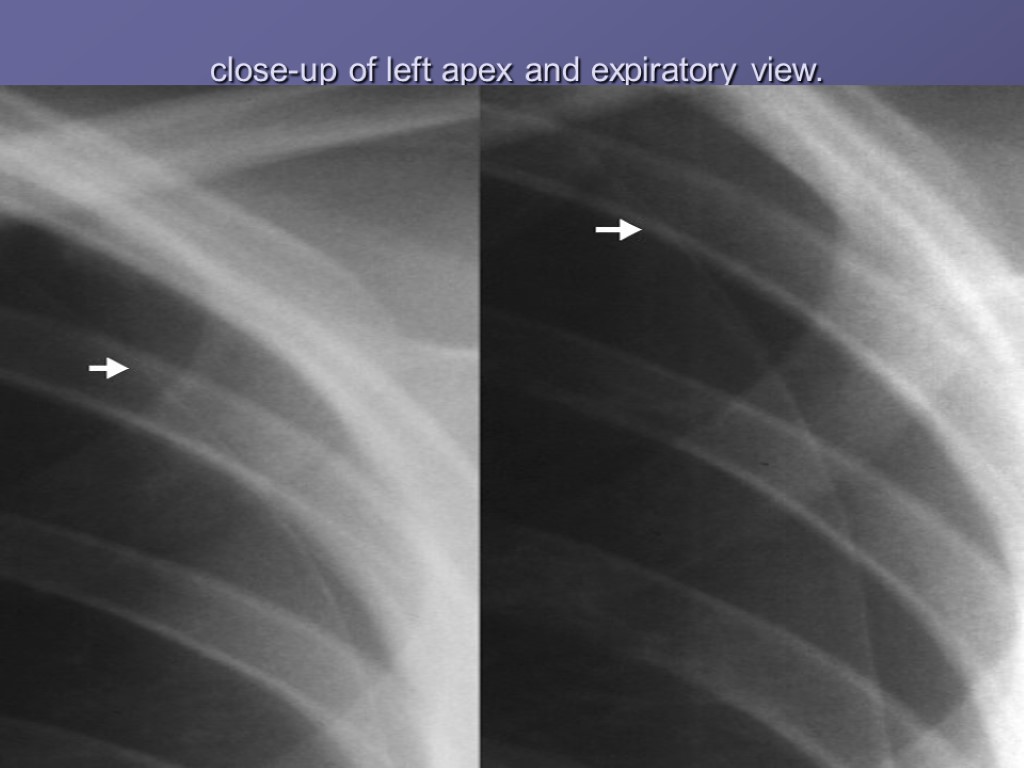

close-up of left apex and expiratory view.

close-up of left apex and expiratory view.

Treatment Pneumothorax associated with mechanical ventilation should almost always be treated with chest tube placement because of the high risk of progression to tension pneumothorax. A spontaneous pneumothorax which is relatively asymptomatic and occupies up to 15 to 25 percent of the hemithorax can be followed clinically and with serial chest xrays. An uncomplicated, untreated pneumothorax will resolve slowly--approximately 1.25 percent per day. This rate of resorbtion can be increased by using supplemental oxygen, which increases the nitrogen gradient from the lung to the pleura

Treatment Pneumothorax associated with mechanical ventilation should almost always be treated with chest tube placement because of the high risk of progression to tension pneumothorax. A spontaneous pneumothorax which is relatively asymptomatic and occupies up to 15 to 25 percent of the hemithorax can be followed clinically and with serial chest xrays. An uncomplicated, untreated pneumothorax will resolve slowly--approximately 1.25 percent per day. This rate of resorbtion can be increased by using supplemental oxygen, which increases the nitrogen gradient from the lung to the pleura

Treatment Surgery is often indicated for recurrent pneumothorax, bilateral pneumothorax, prolonged air leak (longer than five to seven days), or inability to fully expand the lung. Treatment of secondary pneumothorax is often more difficult because of the associated underlying lung disease and because the patients are often symptomatic. Pneumothorax tends to recur more often in these patients, and thus requires more definitive therapy. Sclerotherapy with doxycline or talc should be considered for poor surgical candidates, but this approach may complicate future surgical intervention or lung transplant. A thoracic surgeon should be consulted on these patients. If it is decided that the best treatment is surgical, the recent development of thoracoscopic intervention offers certain benefits. The surgeon can thoracoscopically visualize the full pleura, staple or resect blebs, apply electrocautery, laser, resect pleura or instill sclerosant (usually talc).

Treatment Surgery is often indicated for recurrent pneumothorax, bilateral pneumothorax, prolonged air leak (longer than five to seven days), or inability to fully expand the lung. Treatment of secondary pneumothorax is often more difficult because of the associated underlying lung disease and because the patients are often symptomatic. Pneumothorax tends to recur more often in these patients, and thus requires more definitive therapy. Sclerotherapy with doxycline or talc should be considered for poor surgical candidates, but this approach may complicate future surgical intervention or lung transplant. A thoracic surgeon should be consulted on these patients. If it is decided that the best treatment is surgical, the recent development of thoracoscopic intervention offers certain benefits. The surgeon can thoracoscopically visualize the full pleura, staple or resect blebs, apply electrocautery, laser, resect pleura or instill sclerosant (usually talc).

Cases

Cases

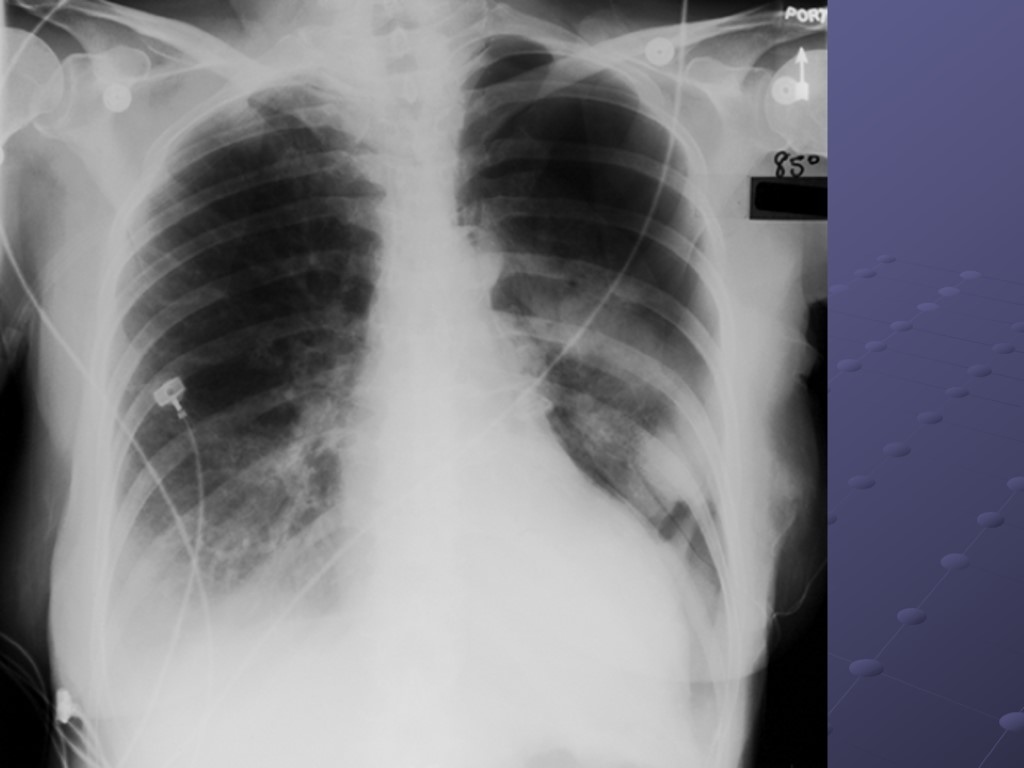

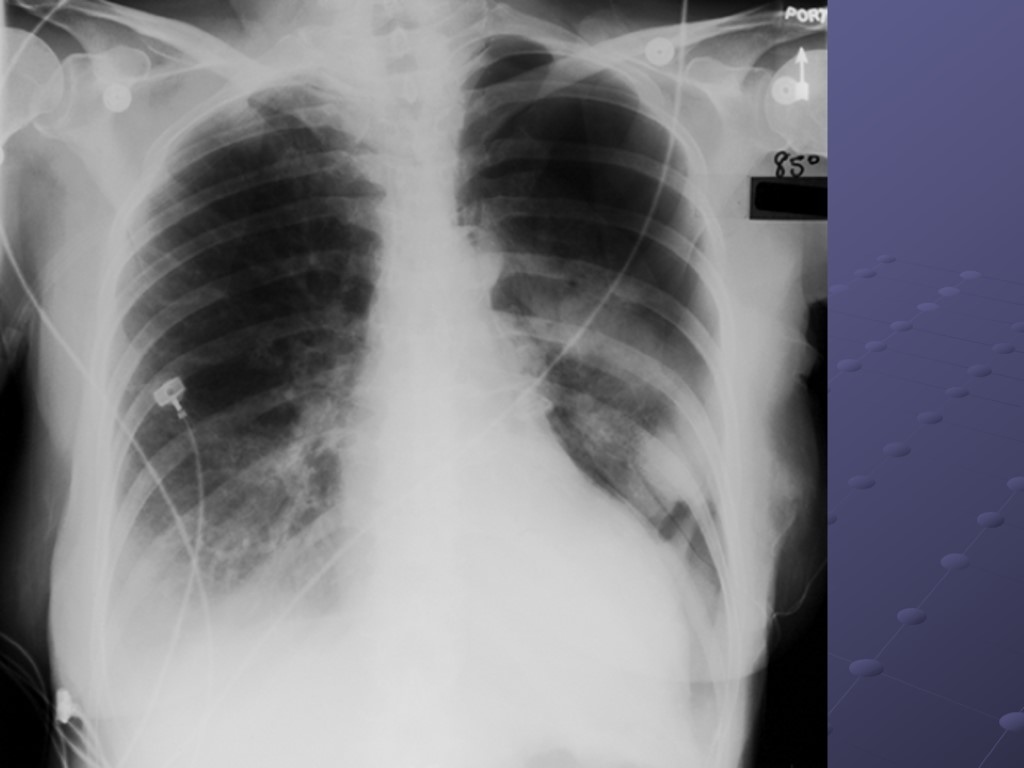

This CXR shows two signs of pneumothorax: a visible pleural line with absent lung markings peripherally and a deep sulcus sign. The "deep sulcus" is due to anterior pneumothorax accentuating the costophronic angle.

This CXR shows two signs of pneumothorax: a visible pleural line with absent lung markings peripherally and a deep sulcus sign. The "deep sulcus" is due to anterior pneumothorax accentuating the costophronic angle.

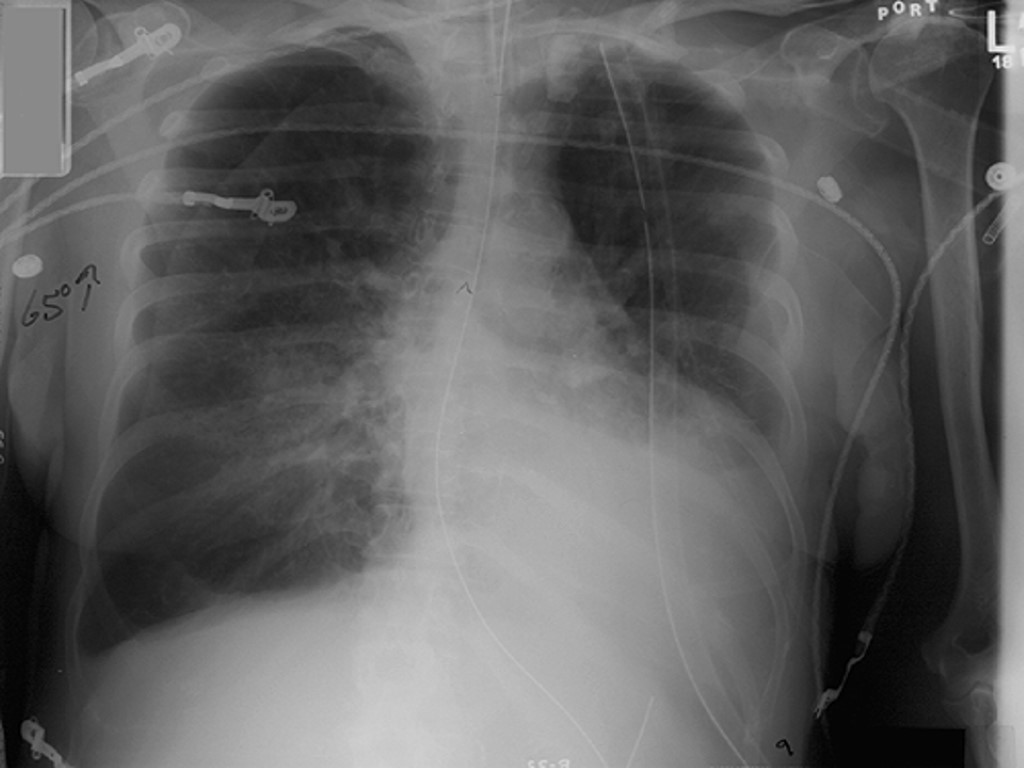

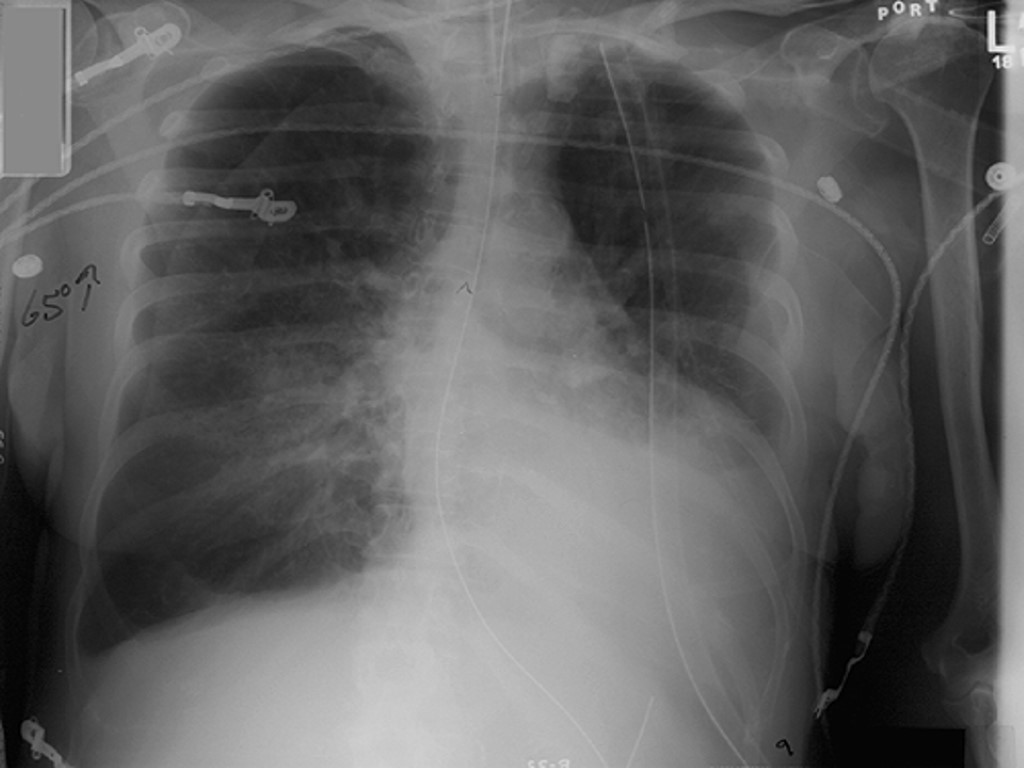

A chest tube was placed with resolution of the left pneumothorax. However, the patient required mechanical ventilation for recurrent pulmonary edema exacerbated by inferior myocardial ischemia and mitral valve dysfunction. Her cardiopulmonary status slowly improved. Several days later, the intern was called with a stat radiology report of a large right pneumothorax. The patient's clinical status had not significantly changed.

A chest tube was placed with resolution of the left pneumothorax. However, the patient required mechanical ventilation for recurrent pulmonary edema exacerbated by inferior myocardial ischemia and mitral valve dysfunction. Her cardiopulmonary status slowly improved. Several days later, the intern was called with a stat radiology report of a large right pneumothorax. The patient's clinical status had not significantly changed.

This CXR shows a skin fold initially thought to represent a pneumothorax. Unlike a true pneumothorax, a skin fold extends beyond the thorax and lung markings are visible beyond the line. Sometimes however, it can be difficult to make a clear distinction between pneumothorax and skin folds.

This CXR shows a skin fold initially thought to represent a pneumothorax. Unlike a true pneumothorax, a skin fold extends beyond the thorax and lung markings are visible beyond the line. Sometimes however, it can be difficult to make a clear distinction between pneumothorax and skin folds.

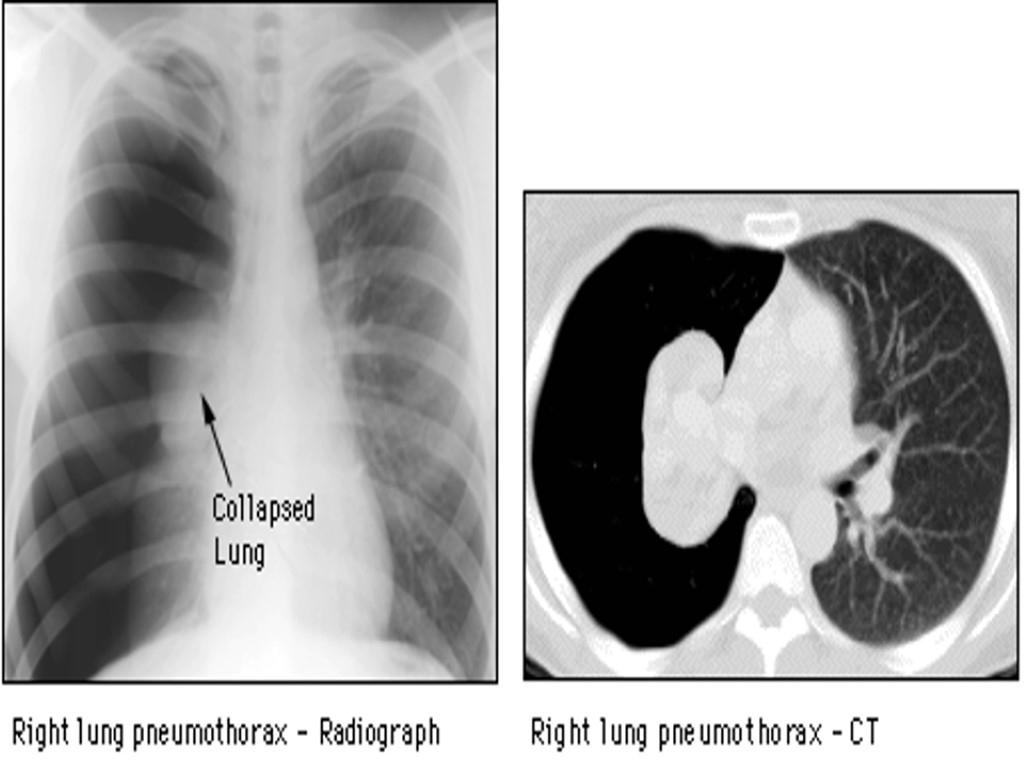

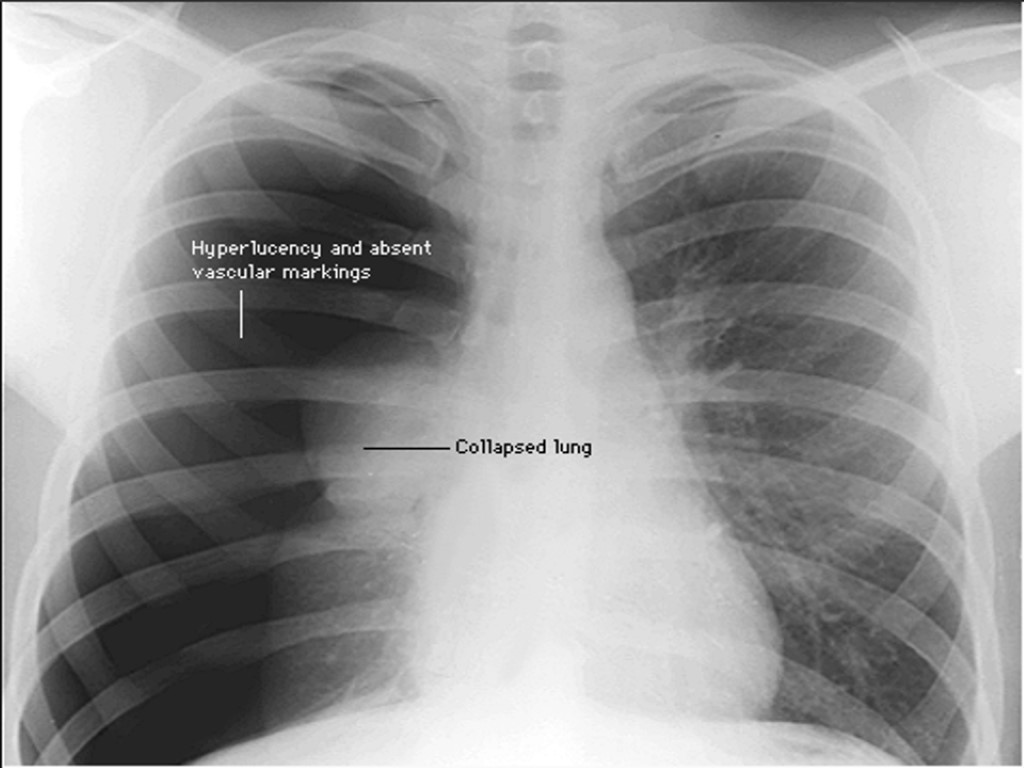

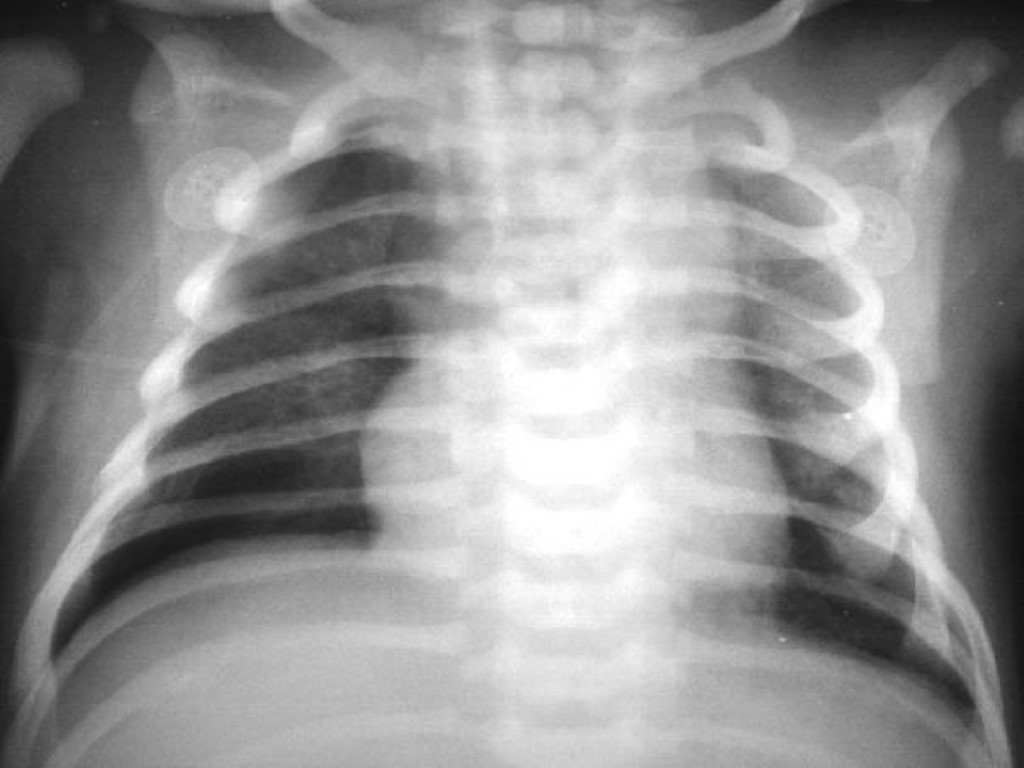

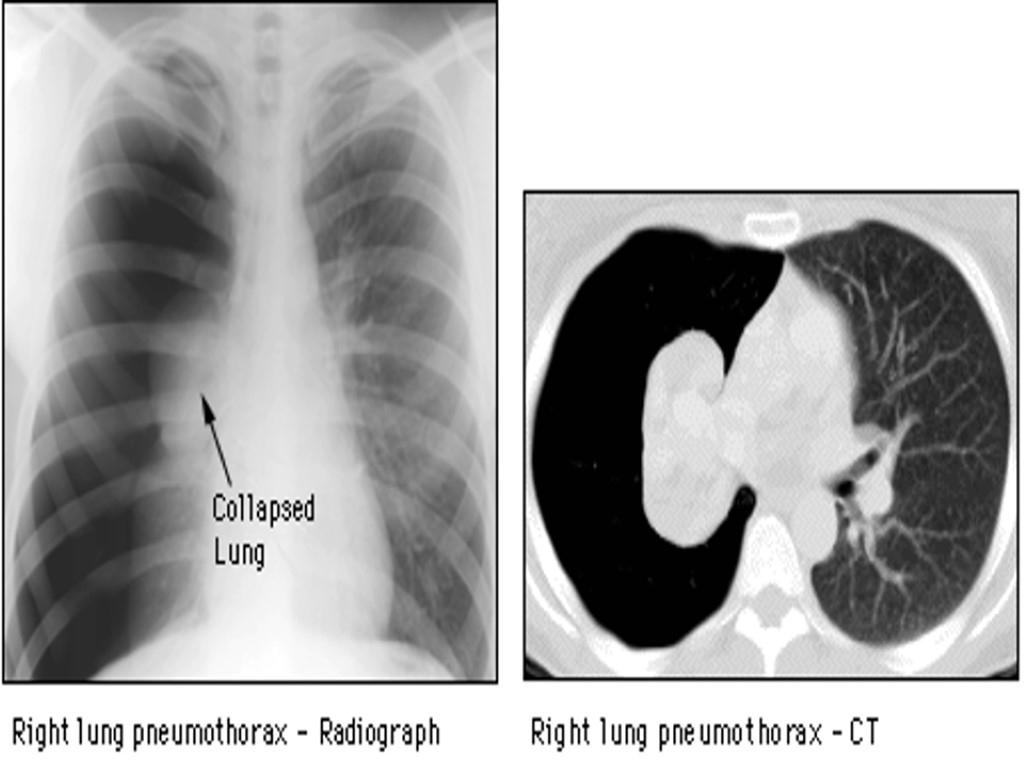

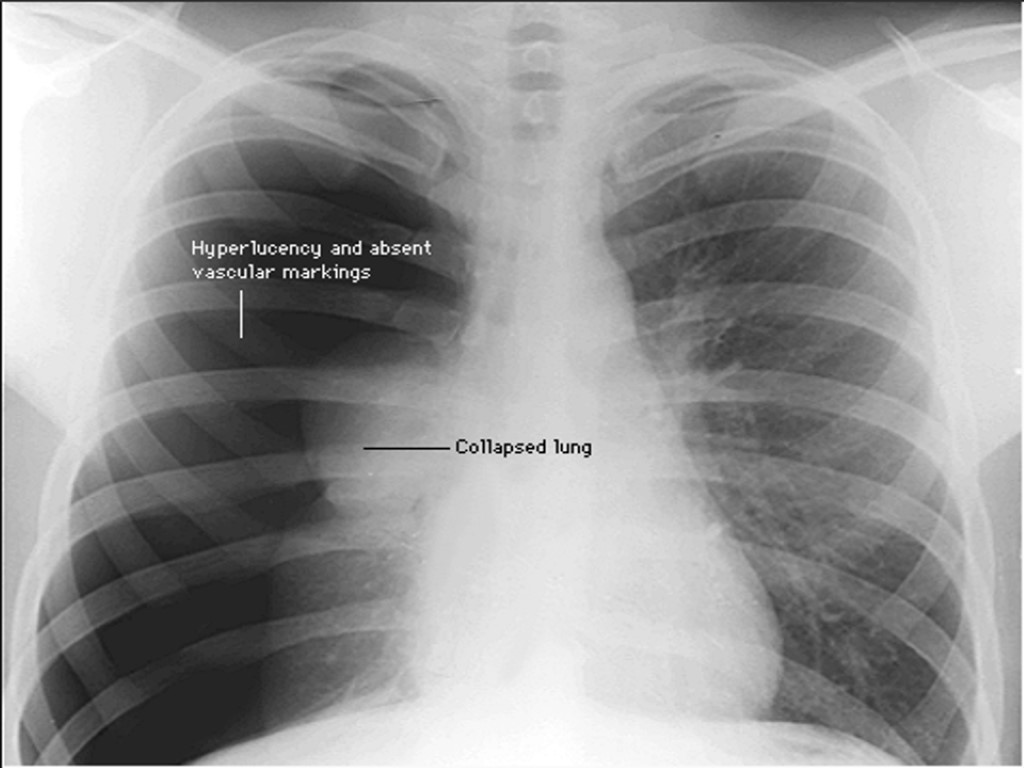

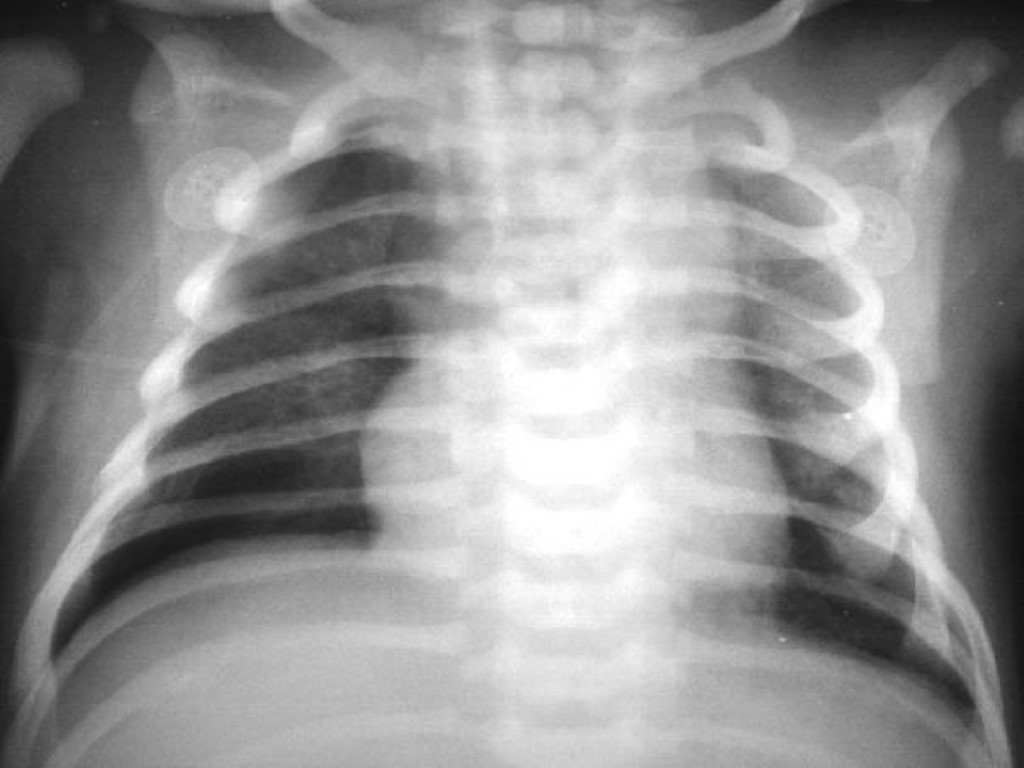

Subtle right pneumothorax.

Subtle right pneumothorax.

This chest radiograph shows pneumomediastinum (radiolucency noted around the left heart border) in this patient who had a respiratory and circulatory arrest in the ED after experiencing multiple episodes of vomiting and a rigid abdomen. The patient was taken immediately to the operating room, where a large rupture of the esophagus was repaired.

This chest radiograph shows pneumomediastinum (radiolucency noted around the left heart border) in this patient who had a respiratory and circulatory arrest in the ED after experiencing multiple episodes of vomiting and a rigid abdomen. The patient was taken immediately to the operating room, where a large rupture of the esophagus was repaired.

Note that although a skin fold can mimic subtle pneumothorax, lung markings are visible beyond the skin fold.

Note that although a skin fold can mimic subtle pneumothorax, lung markings are visible beyond the skin fold.

Deep sulcus sign in a supine patient in the ICU.

Deep sulcus sign in a supine patient in the ICU.

An older man admitted to ICU postoperatively. Note the right-sided pneumothorax induced by the incorrectly positioned small bowel feeding tube in the right-sided bronchial tree. Marked depression of the right hemidiaphragm is noted, and mediastinal shift is to the left side, suggestive of tension pneumothorax. The endotracheal tube is in a good position

An older man admitted to ICU postoperatively. Note the right-sided pneumothorax induced by the incorrectly positioned small bowel feeding tube in the right-sided bronchial tree. Marked depression of the right hemidiaphragm is noted, and mediastinal shift is to the left side, suggestive of tension pneumothorax. The endotracheal tube is in a good position