0541f84dd63caf7704daeb6b266e5752.ppt

- Количество слайдов: 38

Piazza: Data Management Infrastructure for the Semantic Web Joint work with Alon Halevy, Peter Mork, Dan Suciu, Igor Tatarinov, University of Washington Zachary G. Ives University of Pennsylvania CIS 700 – Internet-Scale Distributed Computing February 3, 2004

The Big Question in P 2 P Why use a P 2 P system vs. a centralized one? § PRO : P 2 P offers greater flexibility and resource utilization § CON : P 2 P often sacrifices reliability guarantees, accountability, and sometimes even performance There a few simple cases where P 2 P wins: § Avoiding the law/RIAA/MPAA: copying music, videos, etc. § Anonymity (Free. Net, etc. ) § Exploiting idle cycles But are there applications that are inherently P 2 P? 2

Most P 2 P Work is “Bottom-up” § The basis of P 2 P: Algorithms/data structures papers § Chord, CAN, Pastry § Focus on providing a robust DHT – not what to do with it § Several systems build functionality over the DHT: § Tang et al. information retrieval paper Maps LSI space into CAN multidimensional space Interesting but uncertain benefits § Berkeley PIER DB query engine: uses distributed hash table to do distributed joins § Sophia Prolog rules in a distributed environment for network monitoring § None of these apps are inherently (or perhaps even best) based on P 2 P architectures 3

Thinking Top-Down § Find an application that has needs matching the properties of P 2 P: § No central authority (and no logical owner of central server) § Loose, relatively ad hoc membership § Capabilities of a system grow as new members join § Participants are generally cooperative 4

One Possible Answer: Data Integration/Interchange Applications § Multiple parties have proprietary data + sources § Not willing to relinquish control or change their data representation, but are willing to share § Examples: § UPenn hospital system is looking to modernize information sharing among departments (trauma, neurology, etc. ) § Many bioinformatics warehouses (e. g. , Penn’s GUS, NCBI’s Gene. Bank) have related info they would like to share § The W 3 C’s vision of the “Semantic Web”: a web where all pages are annotated with meaning, meanings are well-defined, and complex questions can be answered 5

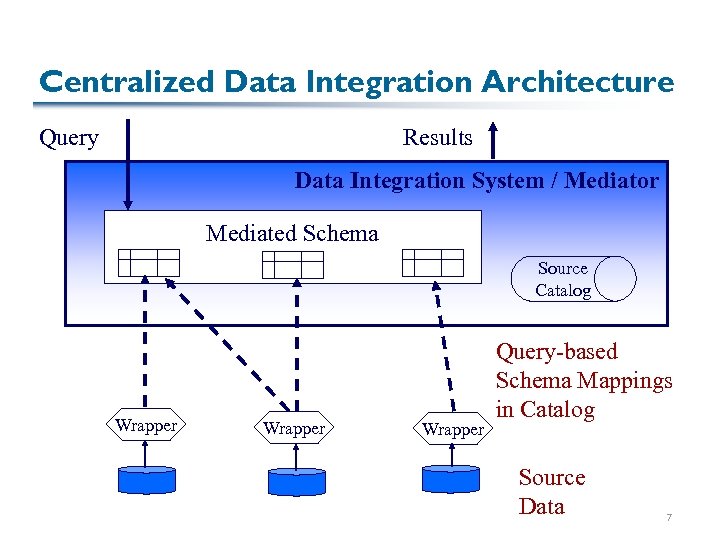

The “Old” Model: Centralization § Get all parties to hash out a standard, global schema or ontology § Different classes of objects to be represented § Constraints + relationships between them § Relate all of the data sources to that schema § Relationships are specified as named queries – views § Efficient techniques exist for using these views to answer future queries posed over the mediated schema 6

Centralized Data Integration Architecture Query Results Data Integration System / Mediator Mediated Schema Source Catalog Wrapper Query-based Schema Mappings in Catalog Source Data 7

Centralization Doesn’t Scale § Difficult to arrive at one standard schema § … When we do, it’s slow to evolve to new needs § This is a human factor, but it is also a scalability issue § Hard to leverage mappings well: § If we map source A mediated schema, does this help us map source B, even if source B is “almost” like source A? § Can we prevent mappings from “breaking” when we update the central schema? § Users often prefer familiar schema, not central one § More schemas more users forced to change schemas 8

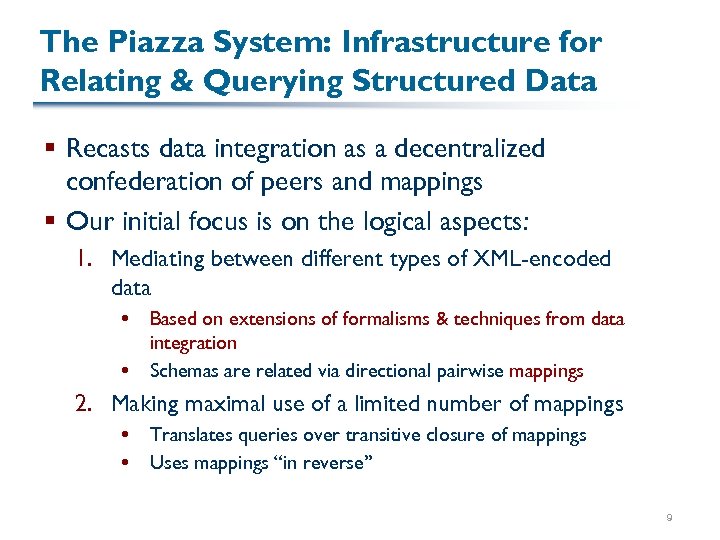

The Piazza System: Infrastructure for Relating & Querying Structured Data § Recasts data integration as a decentralized confederation of peers and mappings § Our initial focus is on the logical aspects: 1. Mediating between different types of XML-encoded data Based on extensions of formalisms & techniques from data integration Schemas are related via directional pairwise mappings 2. Making maximal use of a limited number of mappings Translates queries over transitive closure of mappings Uses mappings “in reverse” 9

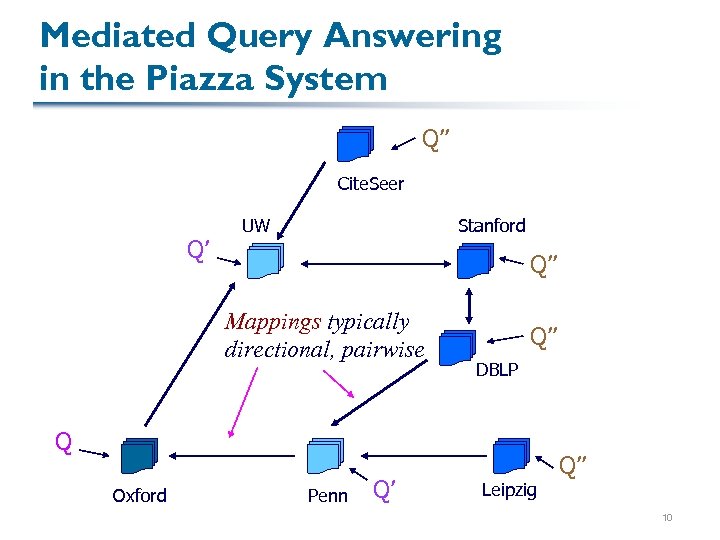

Mediated Query Answering in the Piazza System Q’’ Cite. Seer Q’ UW Stanford Q’’ Mappings typically directional, pairwise Q’’ DBLP Q Oxford Penn Q’ Leipzig Q’’ 10

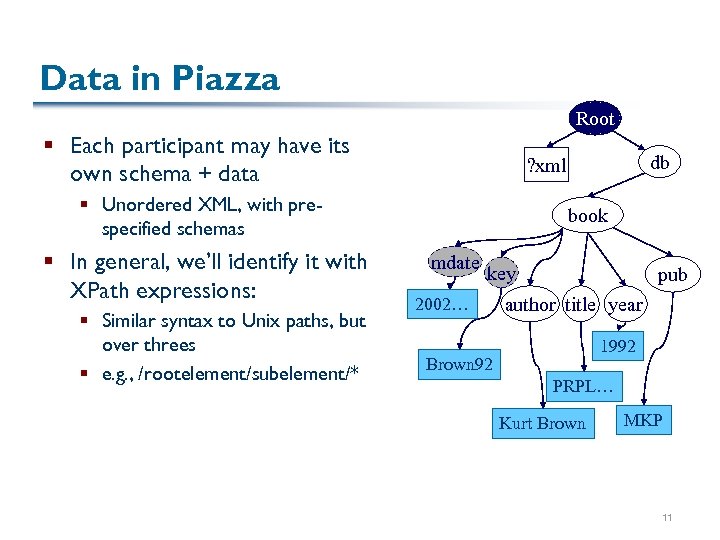

Data in Piazza Root § Each participant may have its own schema + data § Unordered XML, with prespecified schemas § In general, we’ll identify it with XPath expressions: § Similar syntax to Unix paths, but over threes § e. g. , /rootelement/subelement/* db ? xml book mdate key 2002… pub author title year 1992 Brown 92 PRPL… Kurt Brown MKP 11

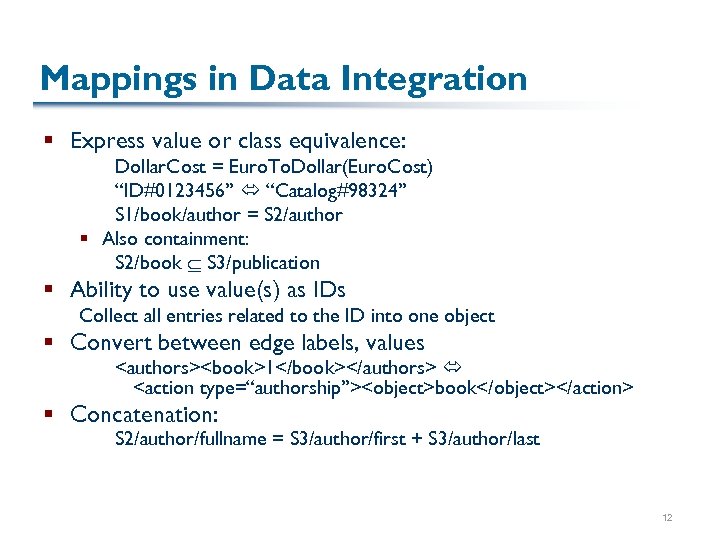

Mappings in Data Integration § Express value or class equivalence: Dollar. Cost = Euro. To. Dollar(Euro. Cost) “ID#0123456” “Catalog#98324” S 1/book/author = S 2/author § Also containment: S 2/book S 3/publication § Ability to use value(s) as IDs Collect all entries related to the ID into one object § Convert between edge labels, values <authors><book>1</book></authors> <action type=“authorship”><object>book</object></action> § Concatenation: S 2/author/fullname = S 3/author/first + S 3/author/last 12

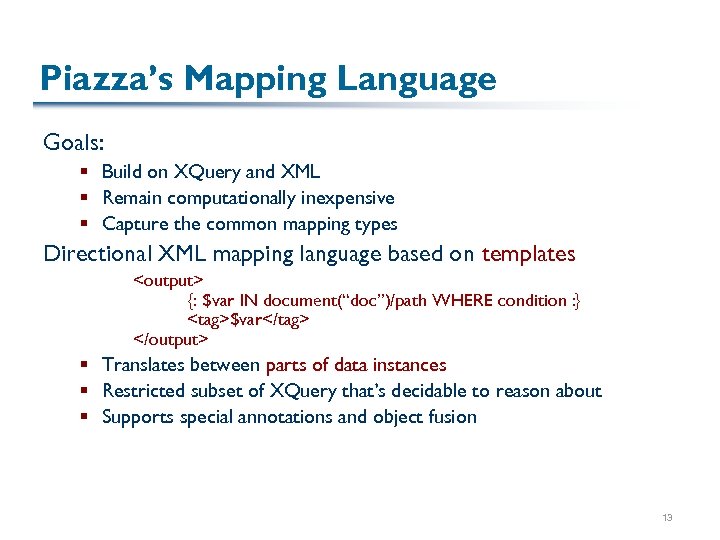

Piazza’s Mapping Language Goals: § Build on XQuery and XML § Remain computationally inexpensive § Capture the common mapping types Directional XML mapping language based on templates <output> {: $var IN document(“doc”)/path WHERE condition : } <tag>$var</tag> </output> § Translates between parts of data instances § Restricted subset of XQuery that’s decidable to reason about § Supports special annotations and object fusion 13

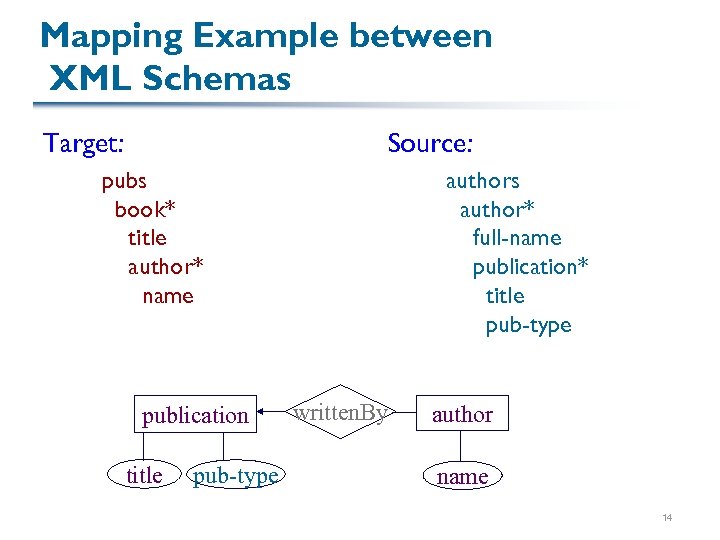

Mapping Example between XML Schemas Target: Source: pubs book* title author* name publication title pub-type authors author* full-name publication* title pub-type written. By author name 14

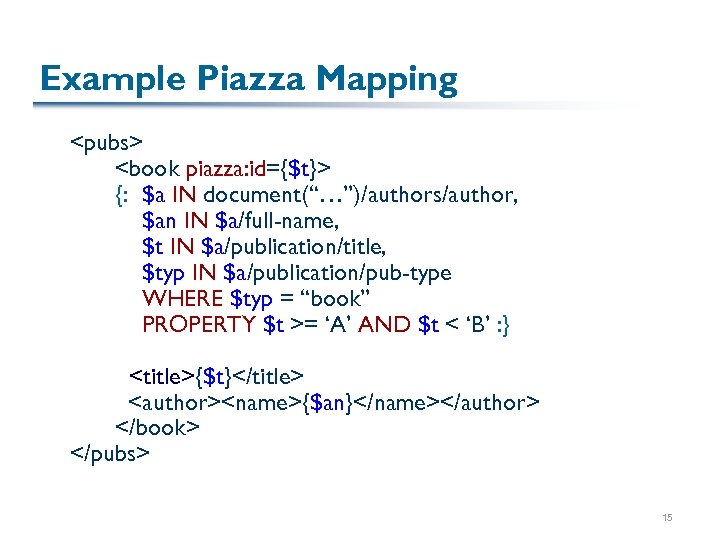

Example Piazza Mapping <pubs> <book piazza: id={$t}> {: $a IN document(“…”)/authors/author, $an IN $a/full-name, $t IN $a/publication/title, $typ IN $a/publication/pub-type WHERE $typ = “book” PROPERTY $t >= ‘A’ AND $t < ‘B’ : } <title>{$t}</title> <author><name>{$an}</name></author> </book> </pubs> 15

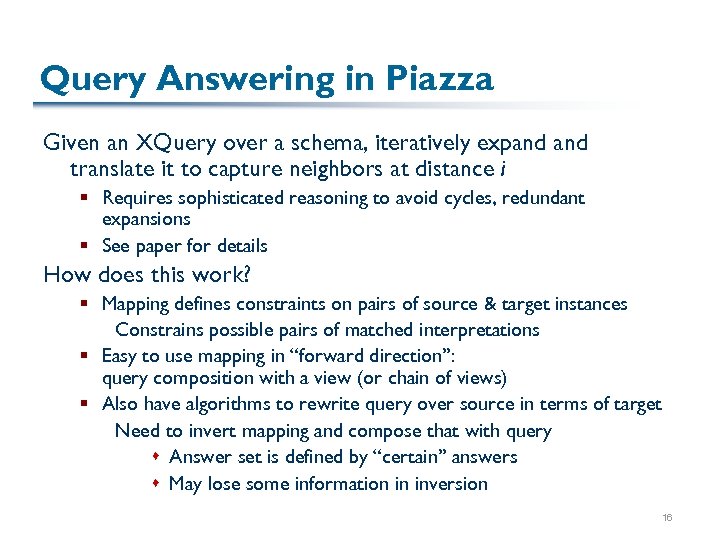

Query Answering in Piazza Given an XQuery over a schema, iteratively expand translate it to capture neighbors at distance i § Requires sophisticated reasoning to avoid cycles, redundant expansions § See paper for details How does this work? § Mapping defines constraints on pairs of source & target instances Constrains possible pairs of matched interpretations § Easy to use mapping in “forward direction”: query composition with a view (or chain of views) § Also have algorithms to rewrite query over source in terms of target Need to invert mapping and compose that with query s Answer set is defined by “certain” answers s May lose some information in inversion 16

Piazza Is One of Several Similar Efforts § Peer-to-peer databases: PIER, Peer. DB, Hyperion, [Bernstein et al. Web. DB 02], [Aberer et al. WWW 03] § RDF engines and mediators for the Semantic Web: EDUTELLA, Sesame § Makes use of semi-automated mapping construction techniques from the database/machine learning communities: § Clio, LSD, GLUE, Cupid, many others 17

Summary: Infrastructure for Decentralized Mediation § Powerful XML mappings and transformations § Extensible, scalable architecture, thanks to sophisticated reasoning techniques for mappings The model itself is peer-to-peer at a logical level – functionality that is best suited to a P 2 P architecture 18

Where from Here? Ongoing Work § Piazza effort at U. Wash. continues to focus on problems relating to mappings § Orchestra at Penn follows up with a focus on two questions: § What does a true DHT-based P 2 P integration system look like? Covers a variety of query processing stages, including mapping reformulation and query optimization, not just execution (as in PIER) § Where should we materialize or replicate data The “data placement” problem § What issues arise when we want to consider updates and synchronization at web-scale? 19

Data Management and P 2 P § We’ve now seen a number of approaches § § Information retrieval Network monitoring Query execution Decentralized data integration § Common themes: § Declarative query languages separate logical + physical levels § Large amount of data with semantic info, distributed in many sites § Which ideas hold the most promise? § Is data management well-suited to P 2 P and DHTs? Does data management need P 2 P? 20

Backup slides… 21

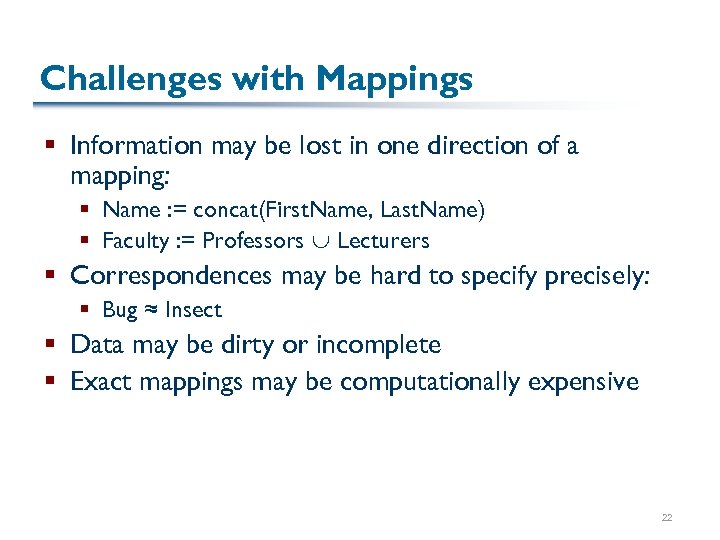

Challenges with Mappings § Information may be lost in one direction of a mapping: § Name : = concat(First. Name, Last. Name) § Faculty : = Professors Lecturers § Correspondences may be hard to specify precisely: § Bug ≈ Insect § Data may be dirty or incomplete § Exact mappings may be computationally expensive 22

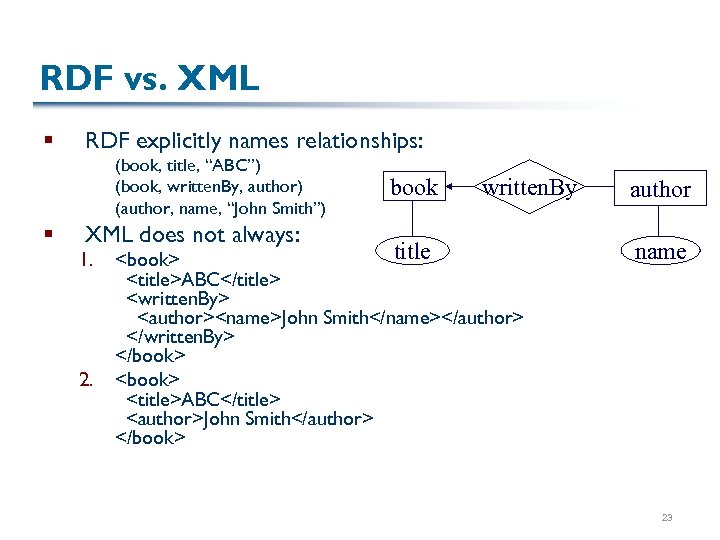

RDF vs. XML § RDF explicitly names relationships: (book, title, “ABC”) (book, written. By, author) (author, name, “John Smith”) § XML does not always: 1. 2. book written. By title <book> <title>ABC</title> <written. By> <author><name>John Smith</name></author> </written. By> </book> <title>ABC</title> <author>John Smith</author> </book> author name 23

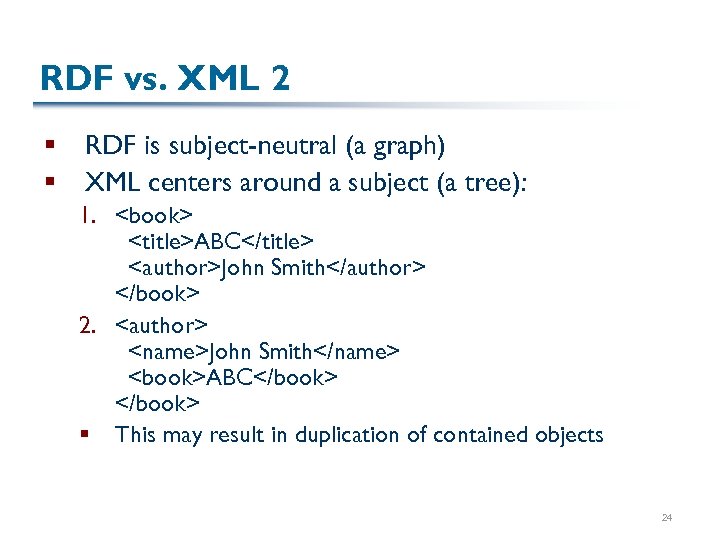

RDF vs. XML 2 § § RDF is subject-neutral (a graph) XML centers around a subject (a tree): 1. <book> <title>ABC</title> <author>John Smith</author> </book> 2. <author> <name>John Smith</name> <book>ABC</book> § This may result in duplication of contained objects 24

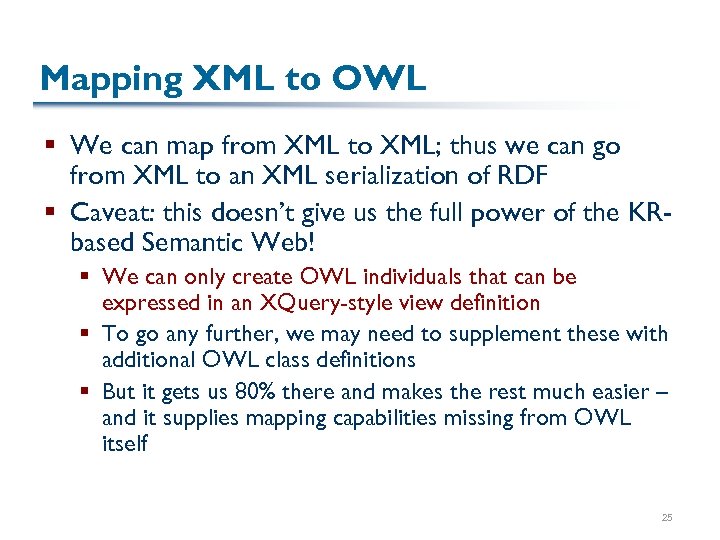

Mapping XML to OWL § We can map from XML to XML; thus we can go from XML to an XML serialization of RDF § Caveat: this doesn’t give us the full power of the KRbased Semantic Web! § We can only create OWL individuals that can be expressed in an XQuery-style view definition § To go any further, we may need to supplement these with additional OWL class definitions § But it gets us 80% there and makes the rest much easier – and it supplies mapping capabilities missing from OWL itself 25

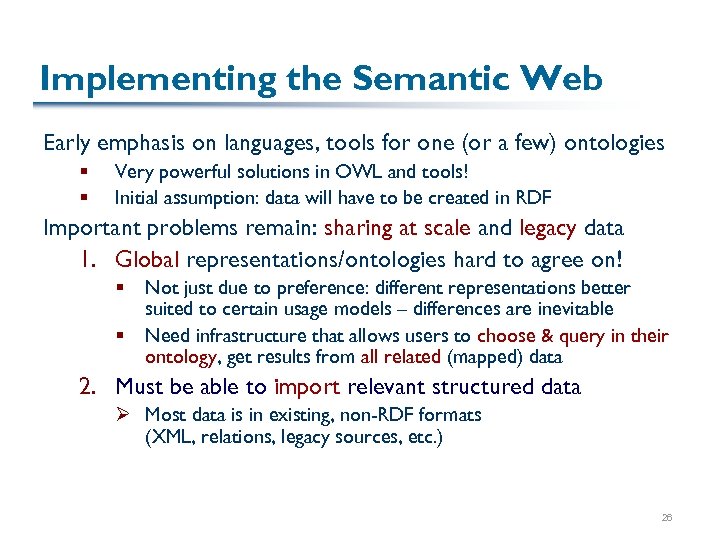

Implementing the Semantic Web Early emphasis on languages, tools for one (or a few) ontologies § § Very powerful solutions in OWL and tools! Initial assumption: data will have to be created in RDF Important problems remain: sharing at scale and legacy data 1. Global representations/ontologies hard to agree on! § § Not just due to preference: different representations better suited to certain usage models – differences are inevitable Need infrastructure that allows users to choose & query in their ontology, get results from all related (mapped) data 2. Must be able to import relevant structured data Ø Most data is in existing, non-RDF formats (XML, relations, legacy sources, etc. ) 26

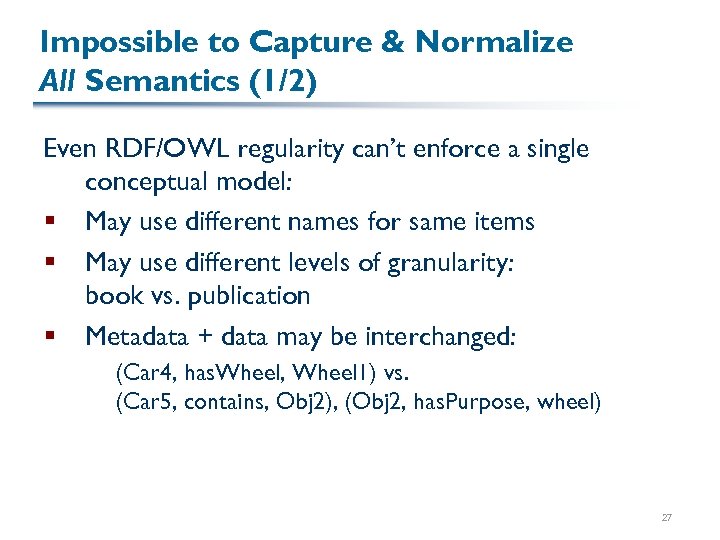

Impossible to Capture & Normalize All Semantics (1/2) Even RDF/OWL regularity can’t enforce a single conceptual model: § May use different names for same items § May use different levels of granularity: book vs. publication § Metadata + data may be interchanged: (Car 4, has. Wheel, Wheel 1) vs. (Car 5, contains, Obj 2), (Obj 2, has. Purpose, wheel) 27

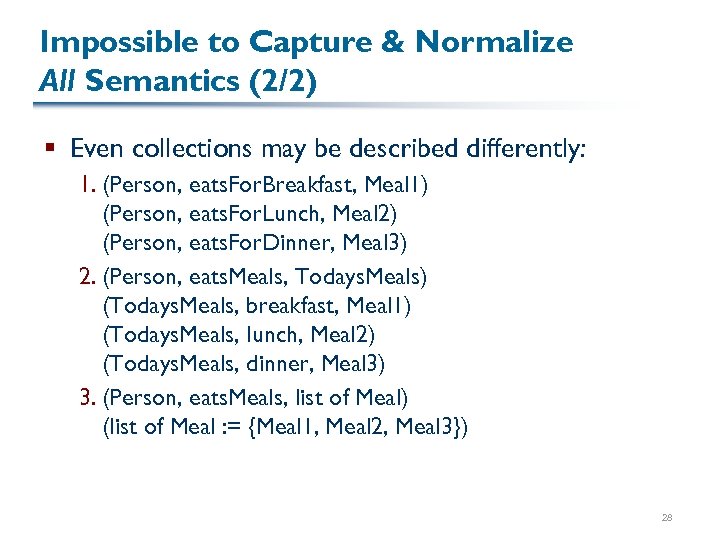

Impossible to Capture & Normalize All Semantics (2/2) § Even collections may be described differently: 1. (Person, eats. For. Breakfast, Meal 1) (Person, eats. For. Lunch, Meal 2) (Person, eats. For. Dinner, Meal 3) 2. (Person, eats. Meals, Todays. Meals) (Todays. Meals, breakfast, Meal 1) (Todays. Meals, lunch, Meal 2) (Todays. Meals, dinner, Meal 3) 3. (Person, eats. Meals, list of Meal) (list of Meal : = {Meal 1, Meal 2, Meal 3}) 28

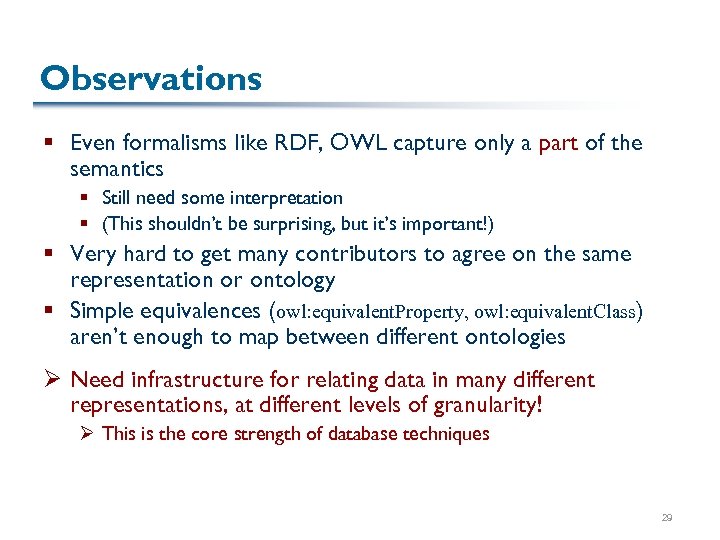

Observations § Even formalisms like RDF, OWL capture only a part of the semantics § Still need some interpretation § (This shouldn’t be surprising, but it’s important!) § Very hard to get many contributors to agree on the same representation or ontology § Simple equivalences (owl: equivalent. Property, owl: equivalent. Class) aren’t enough to map between different ontologies Ø Need infrastructure for relating data in many different representations, at different levels of granularity! Ø This is the core strength of database techniques 29

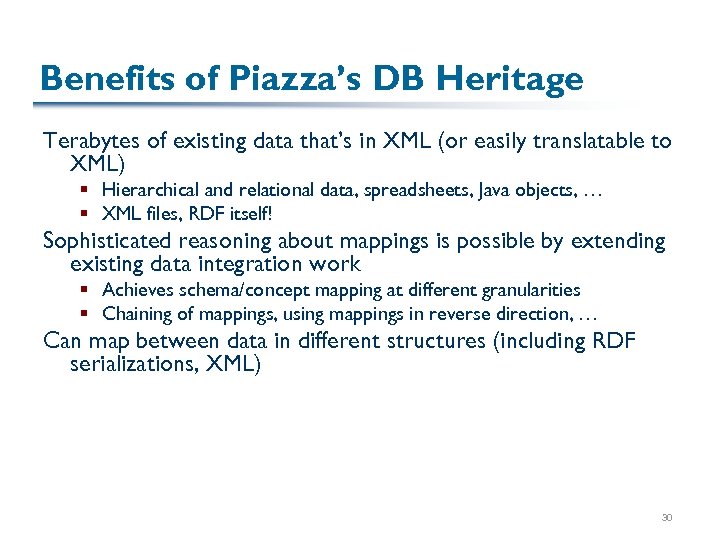

Benefits of Piazza’s DB Heritage Terabytes of existing data that’s in XML (or easily translatable to XML) § Hierarchical and relational data, spreadsheets, Java objects, … § XML files, RDF itself! Sophisticated reasoning about mappings is possible by extending existing data integration work § Achieves schema/concept mapping at different granularities § Chaining of mappings, using mappings in reverse direction, … Can map between data in different structures (including RDF serializations, XML) 30

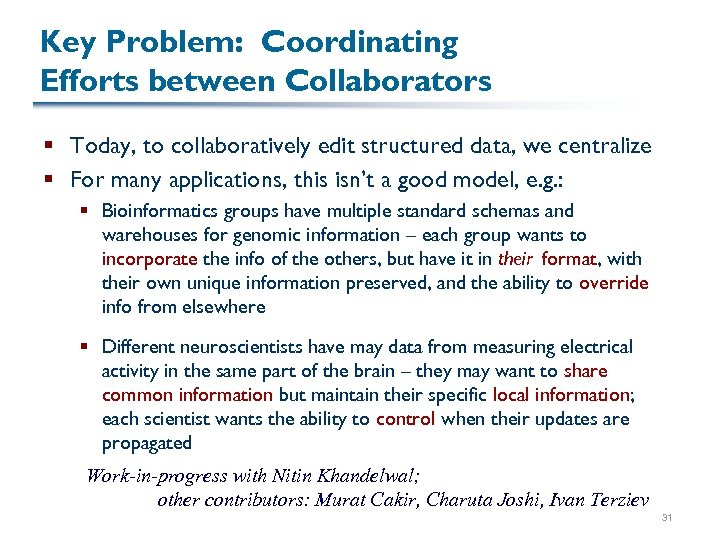

Key Problem: Coordinating Efforts between Collaborators § Today, to collaboratively edit structured data, we centralize § For many applications, this isn’t a good model, e. g. : § Bioinformatics groups have multiple standard schemas and warehouses for genomic information – each group wants to incorporate the info of the others, but have it in their format, with their own unique information preserved, and the ability to override info from elsewhere § Different neuroscientists have may data from measuring electrical activity in the same part of the brain – they may want to share common information but maintain their specific local information; each scientist wants the ability to control when their updates are propagated Work-in-progress with Nitin Khandelwal; other contributors: Murat Cakir, Charuta Joshi, Ivan Terziev 31

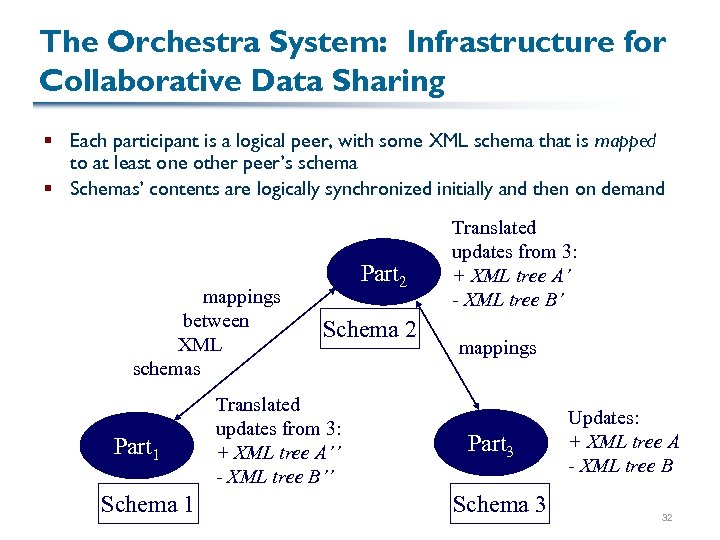

The Orchestra System: Infrastructure for Collaborative Data Sharing § Each participant is a logical peer, with some XML schema that is mapped to at least one other peer’s schema § Schemas’ contents are logically synchronized initially and then on demand mappings between XML schemas Part 1 Schema 1 Part 2 Schema 2 Translated updates from 3: + XML tree A’’ - XML tree B’’ Translated updates from 3: + XML tree A’ - XML tree B’ mappings Part 3 Schema 3 Updates: + XML tree A - XML tree B 32

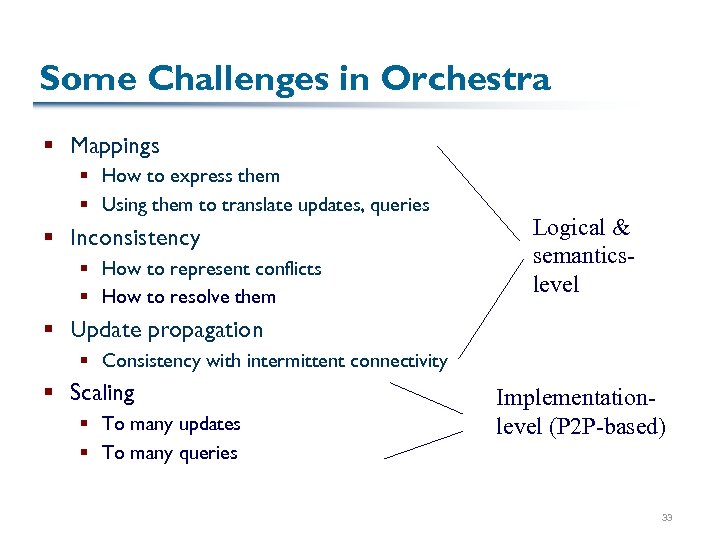

Some Challenges in Orchestra § Mappings § How to express them § Using them to translate updates, queries § Inconsistency § How to represent conflicts § How to resolve them Logical & semanticslevel § Update propagation § Consistency with intermittent connectivity § Scaling § To many updates § To many queries Implementationlevel (P 2 P-based) 33

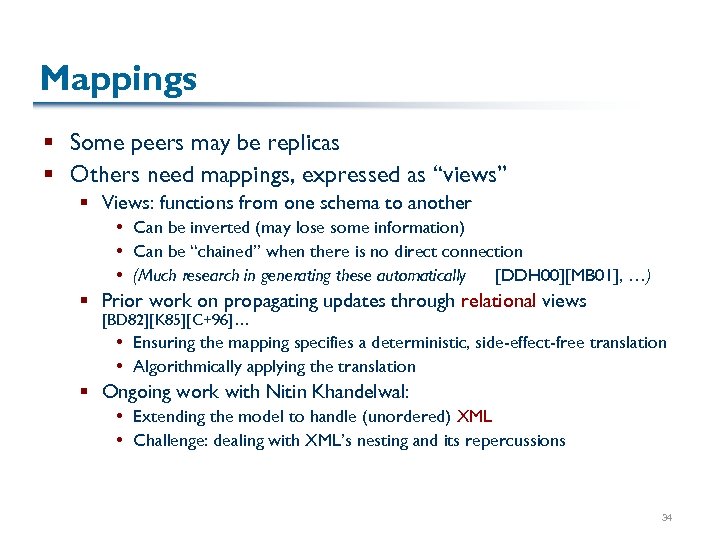

Mappings § Some peers may be replicas § Others need mappings, expressed as “views” § Views: functions from one schema to another Can be inverted (may lose some information) Can be “chained” when there is no direct connection (Much research in generating these automatically [DDH 00][MB 01], …) § Prior work on propagating updates through relational views [BD 82][K 85][C+96]… Ensuring the mapping specifies a deterministic, side-effect-free translation Algorithmically applying the translation § Ongoing work with Nitin Khandelwal: Extending the model to handle (unordered) XML Challenge: dealing with XML’s nesting and its repercussions 34

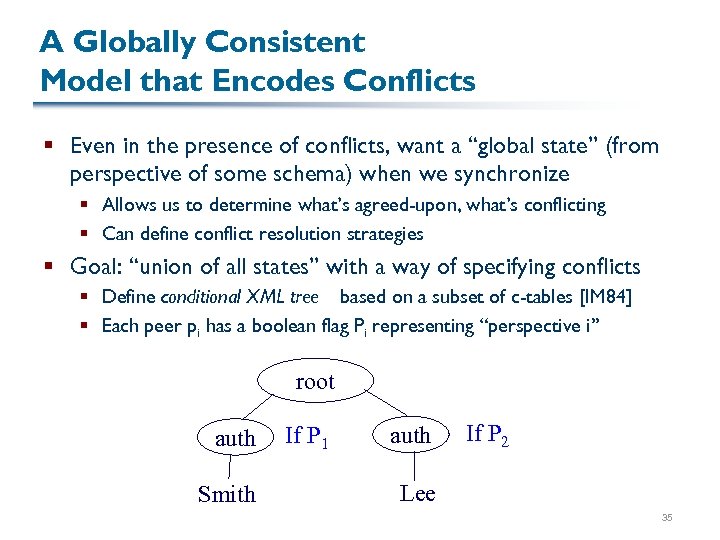

A Globally Consistent Model that Encodes Conflicts § Even in the presence of conflicts, want a “global state” (from perspective of some schema) when we synchronize § Allows us to determine what’s agreed-upon, what’s conflicting § Can define conflict resolution strategies § Goal: “union of all states” with a way of specifying conflicts § Define conditional XML tree based on a subset of c-tables [IM 84] § Each peer pi has a boolean flag Pi representing “perspective i” root auth Smith If P 1 auth If P 2 Lee 35

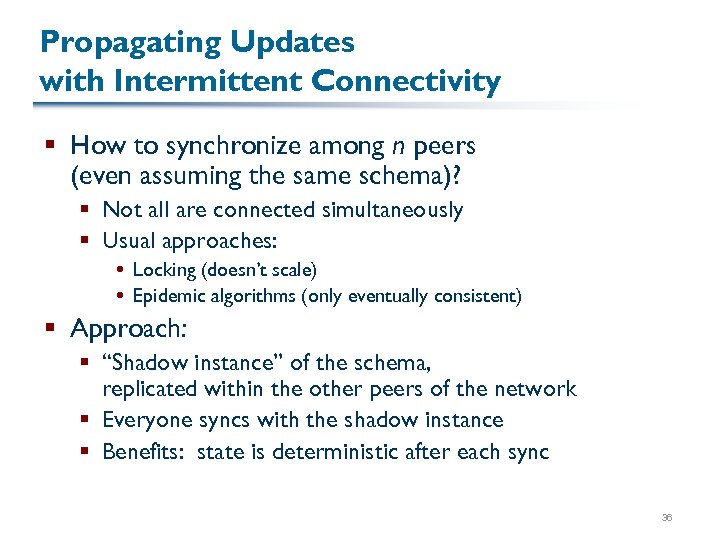

Propagating Updates with Intermittent Connectivity § How to synchronize among n peers (even assuming the same schema)? § Not all are connected simultaneously § Usual approaches: Locking (doesn’t scale) Epidemic algorithms (only eventually consistent) § Approach: § “Shadow instance” of the schema, replicated within the other peers of the network § Everyone syncs with the shadow instance § Benefits: state is deterministic after each sync 36

Scaling, Using P 2 P Techniques § Update synchronization § Key problem: find values conflicting with “shadow instance” § Partition the “shadow instance” across the network § Query execution § Partition computation across multiple peers (PIER does this) § Query optimization § Optimization breaks the query into sub-problems, uses dynamic programming to build up estimates of the costs of applying operators § Can recast as recursion + memoization Use P 2 P overlay to distribute each recursive step Memoize results at every node § Why is this useful? Suppose 2 peers ask the same query! 37

Current Status § Have a basic strategy for addressing many of the problems in collaborative data sharing § Initial sketches of the core algorithms § Need to develop them further § … And to implement (and validate) them in a real system! 38

0541f84dd63caf7704daeb6b266e5752.ppt