PHYS 1 Lecture 1.pptx

- Количество слайдов: 62

PHYSICS 1 • Mechanics • Fluids • Thermodynamics • Harmonic Motion • Wave Theory • Static electricity • Electric Current 1

PHYSICS 1 • Mechanics • Fluids • Thermodynamics • Harmonic Motion • Wave Theory • Static electricity • Electric Current 1

Lecture #1. Kinematics Content : ü ü ü The Realm of Physics The Importance of Accurate Measurements, Calculations, and Uncertainties Motion Speed Average Velocity A Graphical Interpretation of Velocity Instantaneous Velocity Acceleration Motion with Constant Acceleration Galileo and Free Fall 2

Lecture #1. Kinematics Content : ü ü ü The Realm of Physics The Importance of Accurate Measurements, Calculations, and Uncertainties Motion Speed Average Velocity A Graphical Interpretation of Velocity Instantaneous Velocity Acceleration Motion with Constant Acceleration Galileo and Free Fall 2

The Realm of Physics • The word physics comes from a Greek word meaning "knowledge of nature. " • Physics attempts to describe the fundamental nature of the universe and how it works, always striving for the simplest explanations common to the most diverse behavior. • The goal of physics is to explain as many things as possible using as few laws as possible, revealing their underlying simplicity and beauty. 3

The Realm of Physics • The word physics comes from a Greek word meaning "knowledge of nature. " • Physics attempts to describe the fundamental nature of the universe and how it works, always striving for the simplest explanations common to the most diverse behavior. • The goal of physics is to explain as many things as possible using as few laws as possible, revealing their underlying simplicity and beauty. 3

The Realm of Physics • Physicists construct models to represent the world around them. These models form conceptual frameworks that permit us to reduce complex situations into simpler, more understandable forms. • In general, such models of physical systems take a mathematical form. • It is always understood that the models are by nature incomplete and, therefore, imperfect. 4

The Realm of Physics • Physicists construct models to represent the world around them. These models form conceptual frameworks that permit us to reduce complex situations into simpler, more understandable forms. • In general, such models of physical systems take a mathematical form. • It is always understood that the models are by nature incomplete and, therefore, imperfect. 4

The Realm of Physics • Physics is an experimental science. • The acceptance of any physical theory depends on its success in predicting and explaining reproducible observations. • To understand physics, or any experimental science, we must be able to connect our theoretical description of nature with our experimental observations of nature. • This connection is made through quantitative measurements. 5

The Realm of Physics • Physics is an experimental science. • The acceptance of any physical theory depends on its success in predicting and explaining reproducible observations. • To understand physics, or any experimental science, we must be able to connect our theoretical description of nature with our experimental observations of nature. • This connection is made through quantitative measurements. 5

The Importance of Accurate Measurement • A thorough understanding of physical theories rests on knowing how measurements are made and how reliable the measured information is. • Until twentieth century, scientists assumed that a sufficiently clever observer, given enough time and money, could, in principle, measure anything or set of things as accurately as necessary. 6

The Importance of Accurate Measurement • A thorough understanding of physical theories rests on knowing how measurements are made and how reliable the measured information is. • Until twentieth century, scientists assumed that a sufficiently clever observer, given enough time and money, could, in principle, measure anything or set of things as accurately as necessary. 6

The Importance of Accurate Measurement • We cannot make a measurement that does not in some way affect the system being measured, thereby limiting the precision of our measurement. • This limitation is of little or no importance in the everyday measurements. Note That Measurements may be direct and indirect. 7

The Importance of Accurate Measurement • We cannot make a measurement that does not in some way affect the system being measured, thereby limiting the precision of our measurement. • This limitation is of little or no importance in the everyday measurements. Note That Measurements may be direct and indirect. 7

EXSAMPLE • Measuring of the height of the high tree. How can we know the height of the high tree by using a pole with certain height? (Hint: also you know your own height). 8

EXSAMPLE • Measuring of the height of the high tree. How can we know the height of the high tree by using a pole with certain height? (Hint: also you know your own height). 8

Measurements, Calculations, and Uncertainties • The number of digits reported in a measurement, irrespective of the location of the decimal place, is called the number of significant figures. • The number of significant figures is a reflection of how well you know a given quantity. 9

Measurements, Calculations, and Uncertainties • The number of digits reported in a measurement, irrespective of the location of the decimal place, is called the number of significant figures. • The number of significant figures is a reflection of how well you know a given quantity. 9

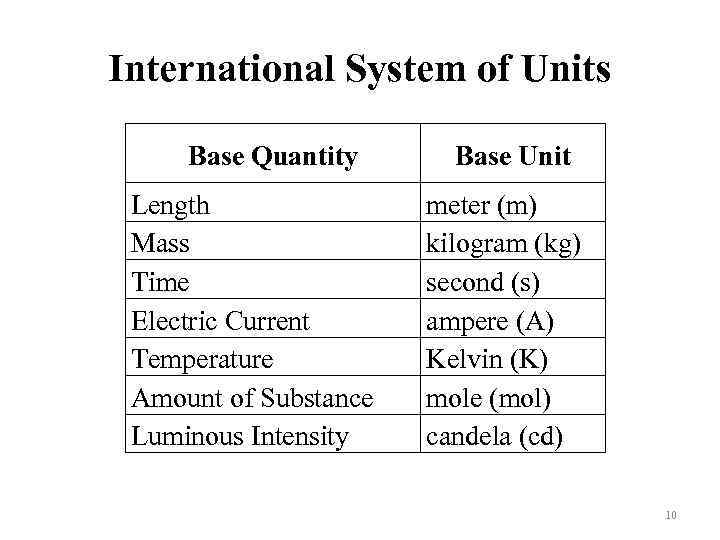

International System of Units Base Quantity Length Mass Time Electric Current Temperature Amount of Substance Luminous Intensity Base Unit meter (m) kilogram (kg) second (s) ampere (A) Kelvin (K) mole (mol) candela (cd) 10

International System of Units Base Quantity Length Mass Time Electric Current Temperature Amount of Substance Luminous Intensity Base Unit meter (m) kilogram (kg) second (s) ampere (A) Kelvin (K) mole (mol) candela (cd) 10

Problem Solving Problem-Solving Guidelines 1. Read the entire problem carefully. Don't worry about the question at first; focus more on what you are being told. 2. Whenever possible, draw a diagram of the physical situation. Label the diagram with the information given in the problem. Be sure to include units, such as meters or kilograms, with the quantities. 11

Problem Solving Problem-Solving Guidelines 1. Read the entire problem carefully. Don't worry about the question at first; focus more on what you are being told. 2. Whenever possible, draw a diagram of the physical situation. Label the diagram with the information given in the problem. Be sure to include units, such as meters or kilograms, with the quantities. 11

Problem Solving 3. Only after you are sure you understand what is given and after you have labeled the diagram should you tackle the question. 4. The next step is to find a mathematical relationship between the known and unknown quantities. In most cases you will need to write the relationship between the known and unknown quantities in the form of an equation, or perhaps several equations. 12

Problem Solving 3. Only after you are sure you understand what is given and after you have labeled the diagram should you tackle the question. 4. The next step is to find a mathematical relationship between the known and unknown quantities. In most cases you will need to write the relationship between the known and unknown quantities in the form of an equation, or perhaps several equations. 12

Problem Solving 5. Next you should solve the equation, or equations, for the unknown quantity or quantities. This means rearranging the formulas in accord with the rules of algebra so that you have an equation with the unknown on the left hand side of the equals sign and all of the known quantities and constants on the right hand side. 6. Now, and only now, should you substitute numerical values into the equation. Do not substitute just "bare numbers, " but substitute both the numerical value and the units. 13

Problem Solving 5. Next you should solve the equation, or equations, for the unknown quantity or quantities. This means rearranging the formulas in accord with the rules of algebra so that you have an equation with the unknown on the left hand side of the equals sign and all of the known quantities and constants on the right hand side. 6. Now, and only now, should you substitute numerical values into the equation. Do not substitute just "bare numbers, " but substitute both the numerical value and the units. 13

Problem Solving Your answer should then come out in the appropriate units. If the units do not come out correctly, you have probably made some basic error. On the other hand, if the units are correct, there is a higher probability that your work is correct. Remember that in giving your final answer you must give the proper number of significant figures. 7. As a final check you should consider whether or not your answer is reasonable. Does your result have the proper order of magnitude? You may even carry out a quick order of magnitude estimate as a way of confirming your work. 14

Problem Solving Your answer should then come out in the appropriate units. If the units do not come out correctly, you have probably made some basic error. On the other hand, if the units are correct, there is a higher probability that your work is correct. Remember that in giving your final answer you must give the proper number of significant figures. 7. As a final check you should consider whether or not your answer is reasonable. Does your result have the proper order of magnitude? You may even carry out a quick order of magnitude estimate as a way of confirming your work. 14

Mechanics The study of mechanics is divided into two parts: kinematics and dynamics. The word kinematics is derived from the Greek word kinema, meaning "motion" — the same root from which we get the word cinema. Kinematics describes the positions and motions of objects in space as a function of time but does not consider the causes of motion. Kinematics provides the means for describing the motions of such varied things as planets, golf balls, and subatomic particles.

Mechanics The study of mechanics is divided into two parts: kinematics and dynamics. The word kinematics is derived from the Greek word kinema, meaning "motion" — the same root from which we get the word cinema. Kinematics describes the positions and motions of objects in space as a function of time but does not consider the causes of motion. Kinematics provides the means for describing the motions of such varied things as planets, golf balls, and subatomic particles.

Introduction The study of the causes of motion is called dynamics. The causes and effects of motion are discussed for many seemingly different situations, but the techniques used are the same.

Introduction The study of the causes of motion is called dynamics. The causes and effects of motion are discussed for many seemingly different situations, but the techniques used are the same.

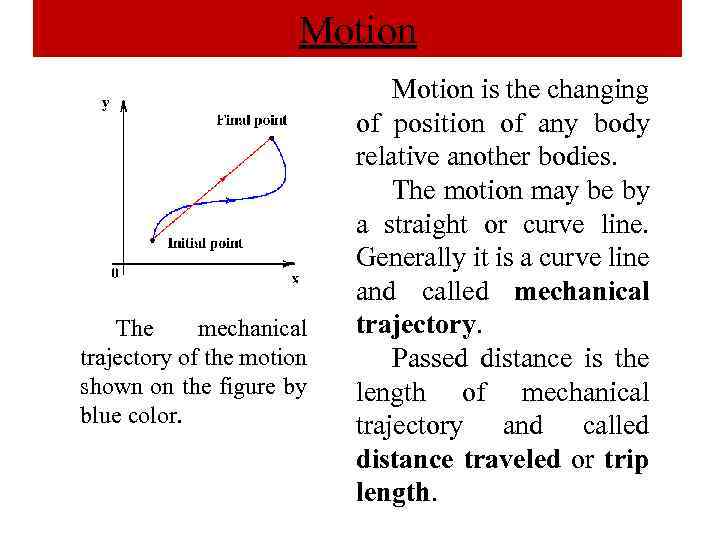

Motion The mechanical trajectory of the motion shown on the figure by blue color. Motion is the changing of position of any body relative another bodies. The motion may be by a straight or curve line. Generally it is a curve line and called mechanical trajectory. Passed distance is the length of mechanical trajectory and called distance traveled or trip length.

Motion The mechanical trajectory of the motion shown on the figure by blue color. Motion is the changing of position of any body relative another bodies. The motion may be by a straight or curve line. Generally it is a curve line and called mechanical trajectory. Passed distance is the length of mechanical trajectory and called distance traveled or trip length.

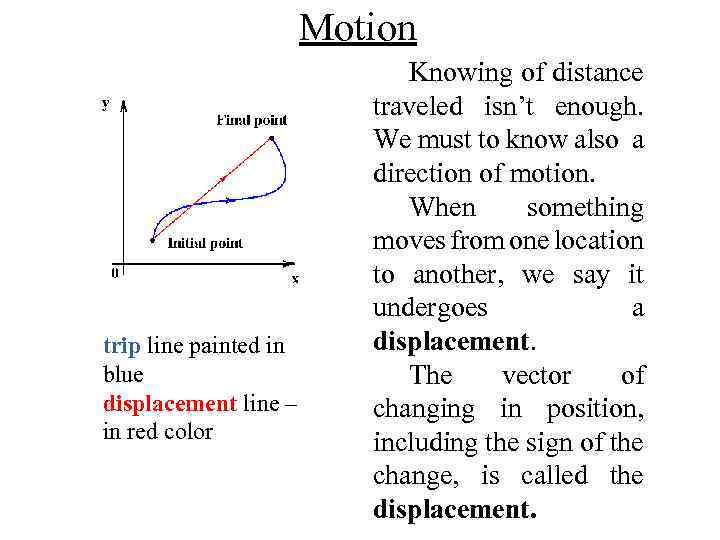

Motion trip line painted in blue displacement line – in red color Knowing of distance traveled isn’t enough. We must to know also a direction of motion. When something moves from one location to another, we say it undergoes a displacement. The vector of changing in position, including the sign of the change, is called the displacement.

Motion trip line painted in blue displacement line – in red color Knowing of distance traveled isn’t enough. We must to know also a direction of motion. When something moves from one location to another, we say it undergoes a displacement. The vector of changing in position, including the sign of the change, is called the displacement.

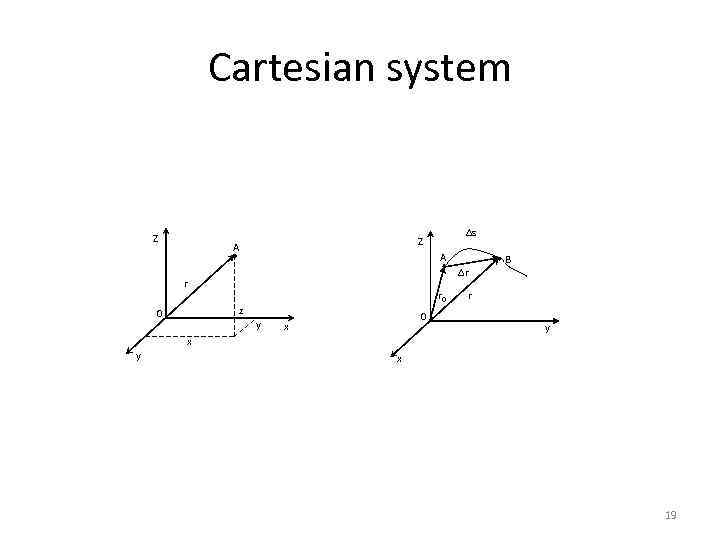

Cartesian system Z A A r r r 0 z 0 s Z y 0 x B r y x 19

Cartesian system Z A A r r r 0 z 0 s Z y 0 x B r y x 19

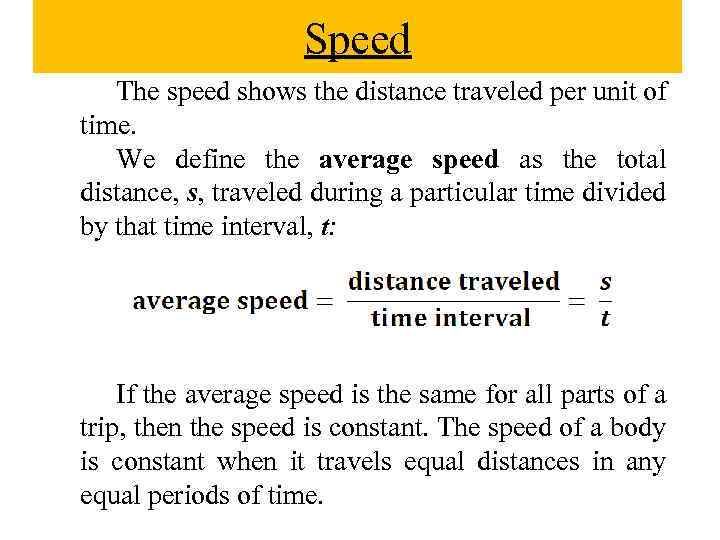

Speed The speed shows the distance traveled per unit of time. We define the average speed as the total distance, s, traveled during a particular time divided by that time interval, t: If the average speed is the same for all parts of a trip, then the speed is constant. The speed of a body is constant when it travels equal distances in any equal periods of time.

Speed The speed shows the distance traveled per unit of time. We define the average speed as the total distance, s, traveled during a particular time divided by that time interval, t: If the average speed is the same for all parts of a trip, then the speed is constant. The speed of a body is constant when it travels equal distances in any equal periods of time.

Speed It is worth emphasizing that this definition refers to neither the size nor shape nor mass nor any other property of the moving body, nor to how the body is influenced by its surroundings. The definition deals only with the motion itself. In the same way, other definitions in kinematics are restricted to properties of the motion only.

Speed It is worth emphasizing that this definition refers to neither the size nor shape nor mass nor any other property of the moving body, nor to how the body is influenced by its surroundings. The definition deals only with the motion itself. In the same way, other definitions in kinematics are restricted to properties of the motion only.

Average Velocity In reality, motion is usually not restricted to one dimension and we must take account of the direction as well as the speed of an object's motion. The name for the quantity that describes both the direction and speed of motion is velocity. In determining a velocity, we refer to a starting (or initial) position and final position.

Average Velocity In reality, motion is usually not restricted to one dimension and we must take account of the direction as well as the speed of an object's motion. The name for the quantity that describes both the direction and speed of motion is velocity. In determining a velocity, we refer to a starting (or initial) position and final position.

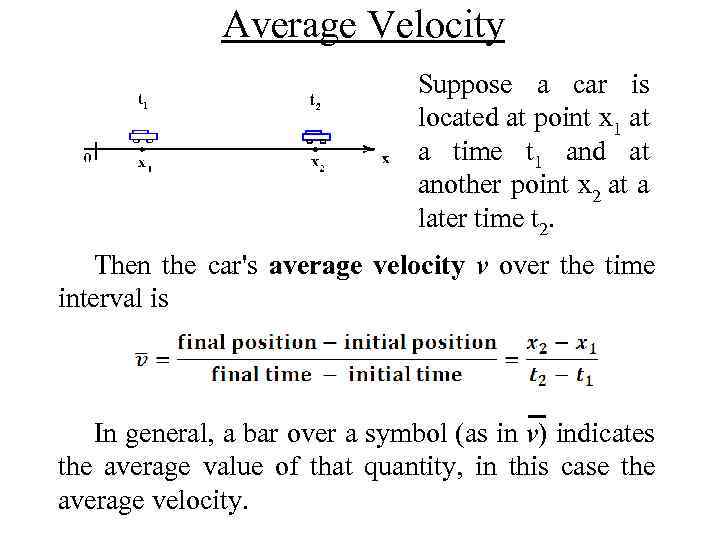

Average Velocity Suppose a car is located at point x 1 at a time t 1 and at another point x 2 at a later time t 2. Then the car's average velocity v over the time interval is In general, a bar over a symbol (as in v) indicates the average value of that quantity, in this case the average velocity.

Average Velocity Suppose a car is located at point x 1 at a time t 1 and at another point x 2 at a later time t 2. Then the car's average velocity v over the time interval is In general, a bar over a symbol (as in v) indicates the average value of that quantity, in this case the average velocity.

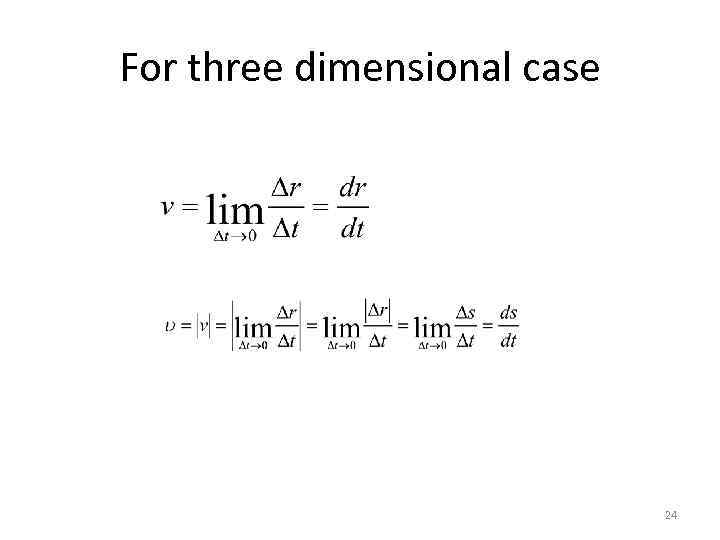

For three dimensional case 24

For three dimensional case 24

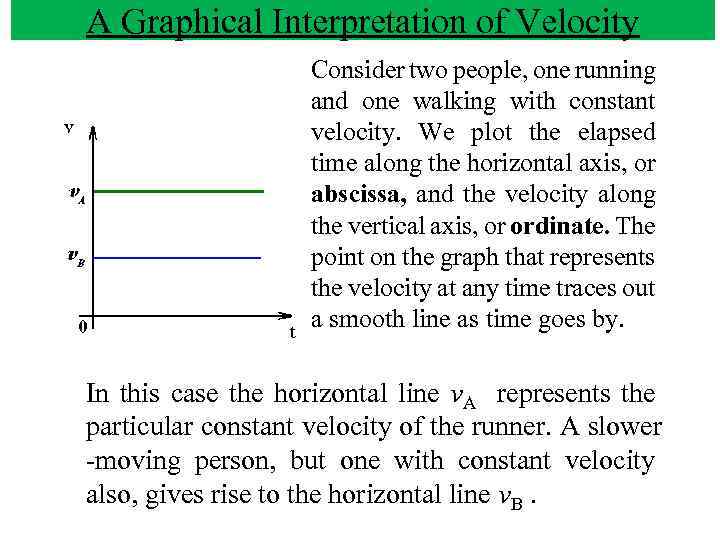

A Graphical Interpretation of Velocity Consider two people, one running and one walking with constant velocity. We plot the elapsed time along the horizontal axis, or abscissa, and the velocity along the vertical axis, or ordinate. The point on the graph that represents the velocity at any time traces out a smooth line as time goes by. In this case the horizontal line v. A represents the particular constant velocity of the runner. A slower moving person, but one with constant velocity also, gives rise to the horizontal line v. B.

A Graphical Interpretation of Velocity Consider two people, one running and one walking with constant velocity. We plot the elapsed time along the horizontal axis, or abscissa, and the velocity along the vertical axis, or ordinate. The point on the graph that represents the velocity at any time traces out a smooth line as time goes by. In this case the horizontal line v. A represents the particular constant velocity of the runner. A slower moving person, but one with constant velocity also, gives rise to the horizontal line v. B.

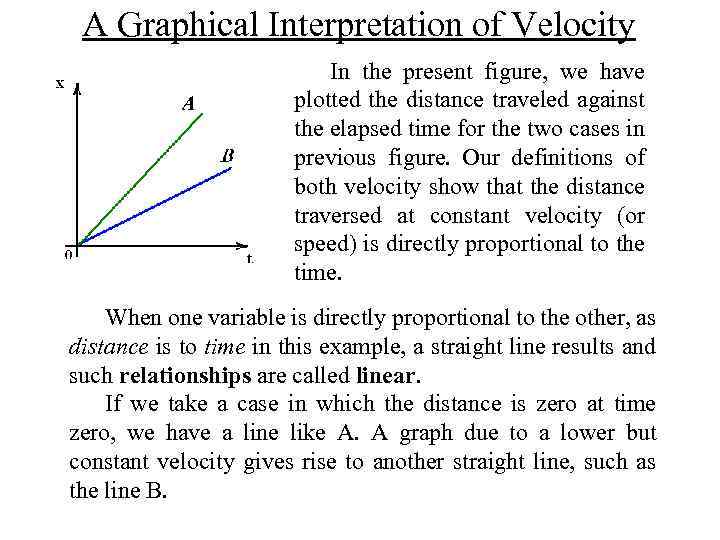

A Graphical Interpretation of Velocity In the present figure, we have plotted the distance traveled against the elapsed time for the two cases in previous figure. Our definitions of both velocity show that the distance traversed at constant velocity (or speed) is directly proportional to the time. When one variable is directly proportional to the other, as distance is to time in this example, a straight line results and such relationships are called linear. If we take a case in which the distance is zero at time zero, we have a line like A. A graph due to a lower but constant velocity gives rise to another straight line, such as the line B.

A Graphical Interpretation of Velocity In the present figure, we have plotted the distance traveled against the elapsed time for the two cases in previous figure. Our definitions of both velocity show that the distance traversed at constant velocity (or speed) is directly proportional to the time. When one variable is directly proportional to the other, as distance is to time in this example, a straight line results and such relationships are called linear. If we take a case in which the distance is zero at time zero, we have a line like A. A graph due to a lower but constant velocity gives rise to another straight line, such as the line B.

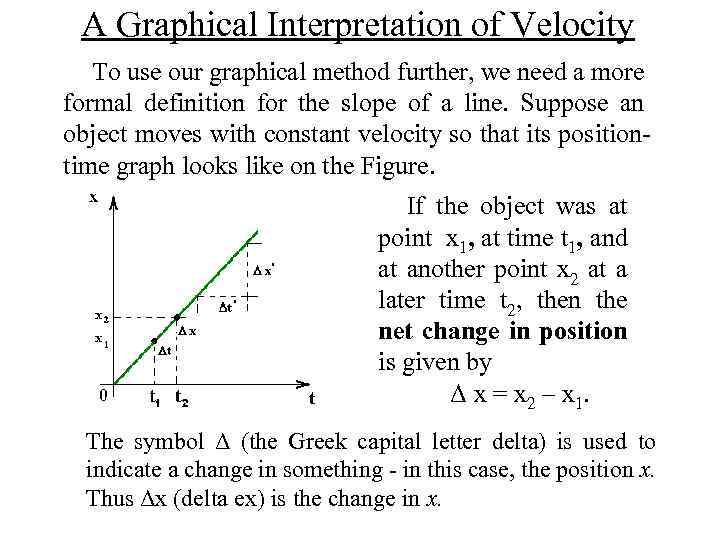

A Graphical Interpretation of Velocity To use our graphical method further, we need a more formal definition for the slope of a line. Suppose an object moves with constant velocity so that its position time graph looks like on the Figure. If the object was at point x 1, at time t 1, and at another point x 2 at a later time t 2, then the net change in position is given by Δ x = x 2 – x 1. The symbol Δ (the Greek capital letter delta) is used to indicate a change in something in this case, the position x. Thus Δx (delta ex) is the change in x.

A Graphical Interpretation of Velocity To use our graphical method further, we need a more formal definition for the slope of a line. Suppose an object moves with constant velocity so that its position time graph looks like on the Figure. If the object was at point x 1, at time t 1, and at another point x 2 at a later time t 2, then the net change in position is given by Δ x = x 2 – x 1. The symbol Δ (the Greek capital letter delta) is used to indicate a change in something in this case, the position x. Thus Δx (delta ex) is the change in x.

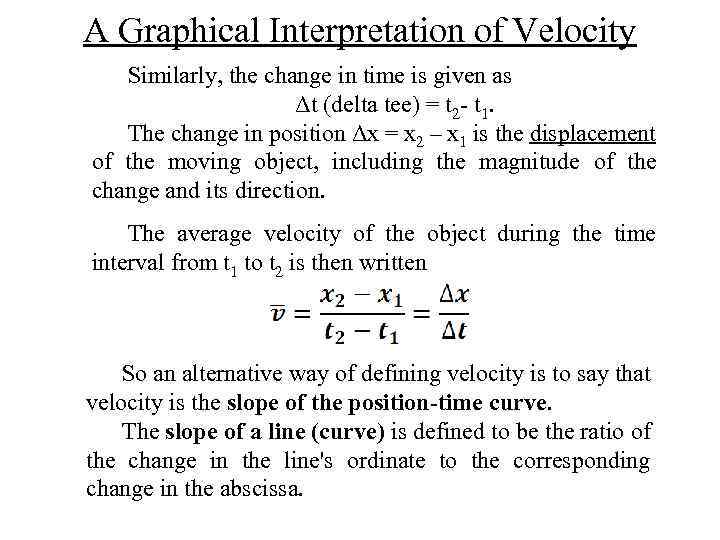

A Graphical Interpretation of Velocity Similarly, the change in time is given as Δt (delta tee) = t 2 t 1. The change in position Δx = x 2 – x 1 is the displacement of the moving object, including the magnitude of the change and its direction. The average velocity of the object during the time interval from t 1 to t 2 is then written So an alternative way of defining velocity is to say that velocity is the slope of the position-time curve. The slope of a line (curve) is defined to be the ratio of the change in the line's ordinate to the corresponding change in the abscissa.

A Graphical Interpretation of Velocity Similarly, the change in time is given as Δt (delta tee) = t 2 t 1. The change in position Δx = x 2 – x 1 is the displacement of the moving object, including the magnitude of the change and its direction. The average velocity of the object during the time interval from t 1 to t 2 is then written So an alternative way of defining velocity is to say that velocity is the slope of the position-time curve. The slope of a line (curve) is defined to be the ratio of the change in the line's ordinate to the corresponding change in the abscissa.

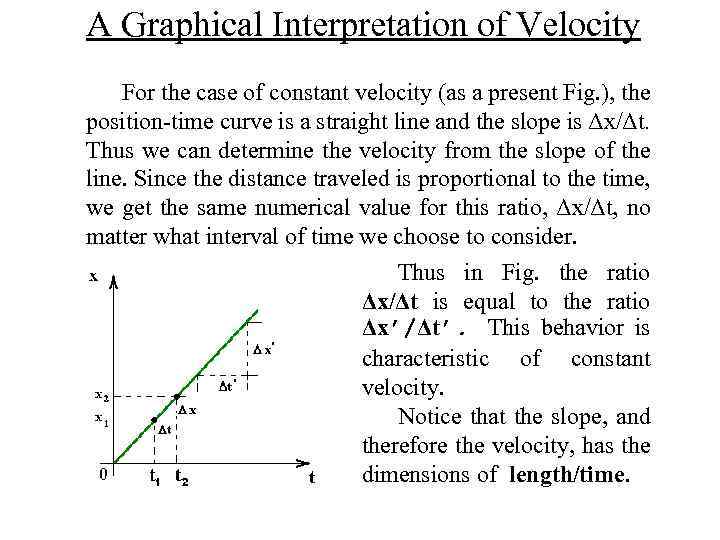

A Graphical Interpretation of Velocity For the case of constant velocity (as a present Fig. ), the position time curve is a straight line and the slope is Δx/Δt. Thus we can determine the velocity from the slope of the line. Since the distance traveled is proportional to the time, we get the same numerical value for this ratio, Δx/Δt, no matter what interval of time we choose to consider. Thus in Fig. the ratio Δx/Δt is equal to the ratio Δx’/Δt’. This behavior is characteristic of constant velocity. Notice that the slope, and therefore the velocity, has the dimensions of length/time.

A Graphical Interpretation of Velocity For the case of constant velocity (as a present Fig. ), the position time curve is a straight line and the slope is Δx/Δt. Thus we can determine the velocity from the slope of the line. Since the distance traveled is proportional to the time, we get the same numerical value for this ratio, Δx/Δt, no matter what interval of time we choose to consider. Thus in Fig. the ratio Δx/Δt is equal to the ratio Δx’/Δt’. This behavior is characteristic of constant velocity. Notice that the slope, and therefore the velocity, has the dimensions of length/time.

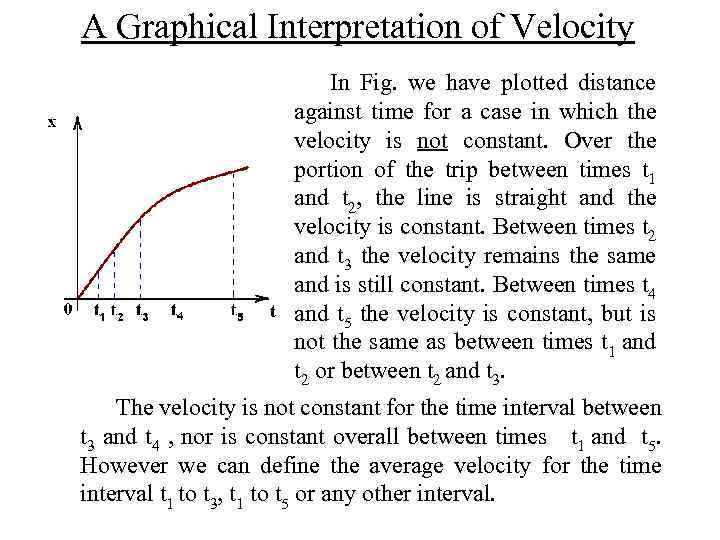

A Graphical Interpretation of Velocity In Fig. we have plotted distance against time for a case in which the velocity is not constant. Over the portion of the trip between times t 1 and t 2, the line is straight and the velocity is constant. Between times t 2 and t 3 the velocity remains the same and is still constant. Between times t 4 and t 5 the velocity is constant, but is not the same as between times t 1 and t 2 or between t 2 and t 3. The velocity is not constant for the time interval between t 3 and t 4 , nor is constant overall between times t 1 and t 5. However we can define the average velocity for the time interval t 1 to t 3, t 1 to t 5 or any other interval.

A Graphical Interpretation of Velocity In Fig. we have plotted distance against time for a case in which the velocity is not constant. Over the portion of the trip between times t 1 and t 2, the line is straight and the velocity is constant. Between times t 2 and t 3 the velocity remains the same and is still constant. Between times t 4 and t 5 the velocity is constant, but is not the same as between times t 1 and t 2 or between t 2 and t 3. The velocity is not constant for the time interval between t 3 and t 4 , nor is constant overall between times t 1 and t 5. However we can define the average velocity for the time interval t 1 to t 3, t 1 to t 5 or any other interval.

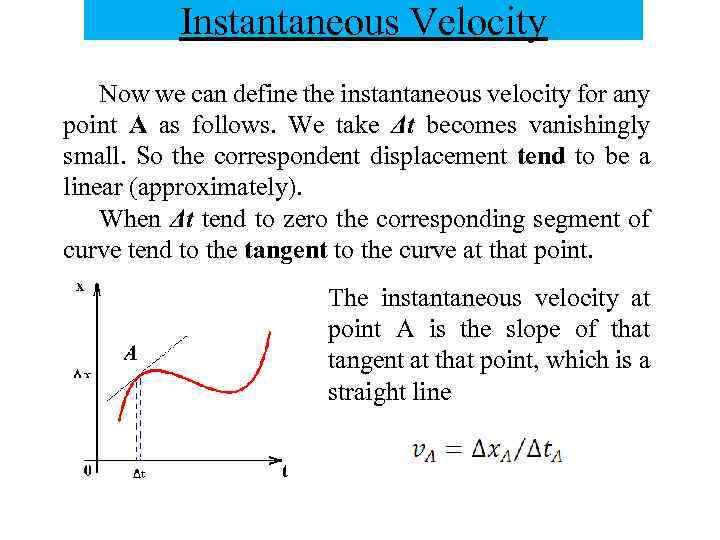

Instantaneous Velocity Now we can define the instantaneous velocity for any point A as follows. We take Δt becomes vanishingly small. So the correspondent displacement tend to be a linear (approximately). When Δt tend to zero the corresponding segment of curve tend to the tangent to the curve at that point. The instantaneous velocity at point A is the slope of that tangent at that point, which is a straight line

Instantaneous Velocity Now we can define the instantaneous velocity for any point A as follows. We take Δt becomes vanishingly small. So the correspondent displacement tend to be a linear (approximately). When Δt tend to zero the corresponding segment of curve tend to the tangent to the curve at that point. The instantaneous velocity at point A is the slope of that tangent at that point, which is a straight line

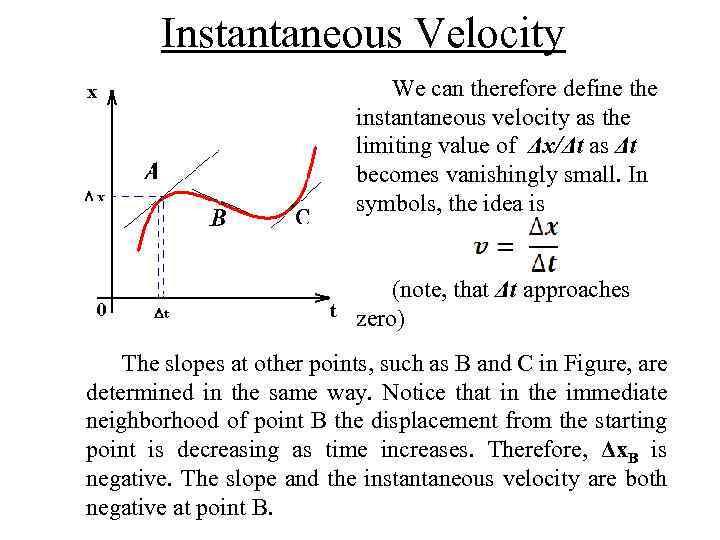

Instantaneous Velocity We can therefore define the instantaneous velocity as the limiting value of Δx/Δt as Δt becomes vanishingly small. In symbols, the idea is (note, that Δt approaches zero) The slopes at other points, such as В and С in Figure, are determined in the same way. Notice that in the immediate neighborhood of point B the displacement from the starting point is decreasing as time increases. Therefore, Δx. B is negative. The slope and the instantaneous velocity are both negative at point B.

Instantaneous Velocity We can therefore define the instantaneous velocity as the limiting value of Δx/Δt as Δt becomes vanishingly small. In symbols, the idea is (note, that Δt approaches zero) The slopes at other points, such as В and С in Figure, are determined in the same way. Notice that in the immediate neighborhood of point B the displacement from the starting point is decreasing as time increases. Therefore, Δx. B is negative. The slope and the instantaneous velocity are both negative at point B.

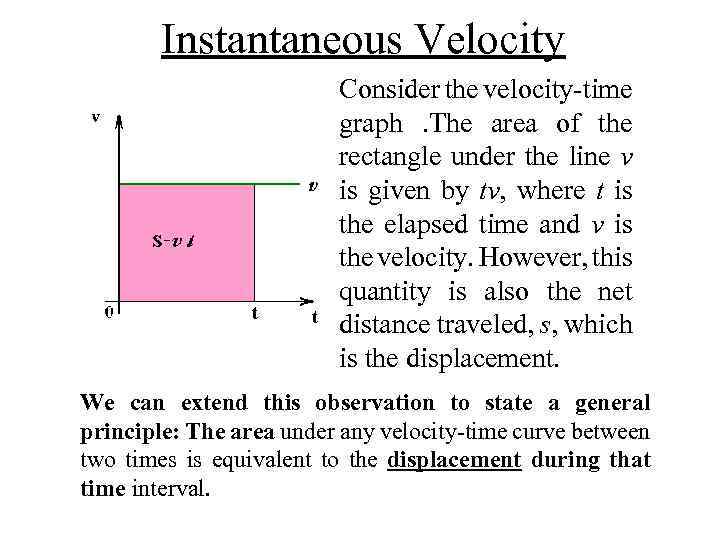

Instantaneous Velocity Consider the velocity time graph. The area of the rectangle under the line v is given by tv, where t is the elapsed time and v is the velocity. However, this quantity is also the net distance traveled, s, which is the displacement. We can extend this observation to state a general principle: The area under any velocity time curve between two times is equivalent to the displacement during that time interval.

Instantaneous Velocity Consider the velocity time graph. The area of the rectangle under the line v is given by tv, where t is the elapsed time and v is the velocity. However, this quantity is also the net distance traveled, s, which is the displacement. We can extend this observation to state a general principle: The area under any velocity time curve between two times is equivalent to the displacement during that time interval.

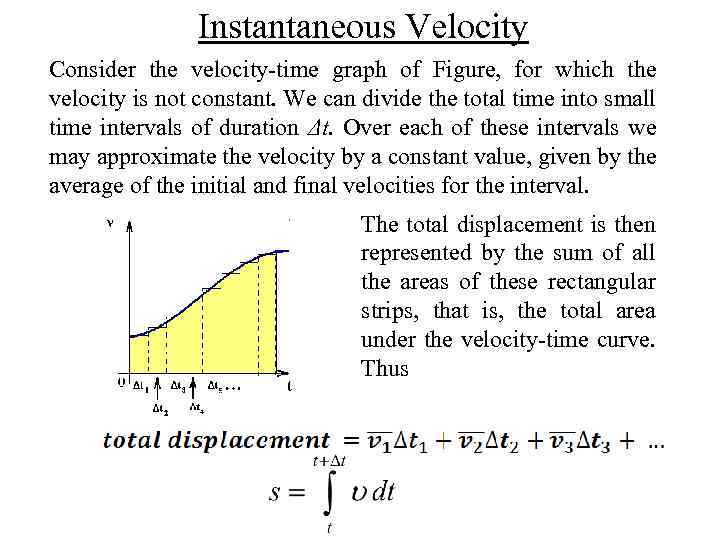

Instantaneous Velocity Consider the velocity time graph of Figure, for which the velocity is not constant. We can divide the total time into small time intervals of duration Δt. Over each of these intervals we may approximate the velocity by a constant value, given by the average of the initial and final velocities for the interval. The total displacement is then represented by the sum of all the areas of these rectangular strips, that is, the total area under the velocity time curve. Thus

Instantaneous Velocity Consider the velocity time graph of Figure, for which the velocity is not constant. We can divide the total time into small time intervals of duration Δt. Over each of these intervals we may approximate the velocity by a constant value, given by the average of the initial and final velocities for the interval. The total displacement is then represented by the sum of all the areas of these rectangular strips, that is, the total area under the velocity time curve. Thus

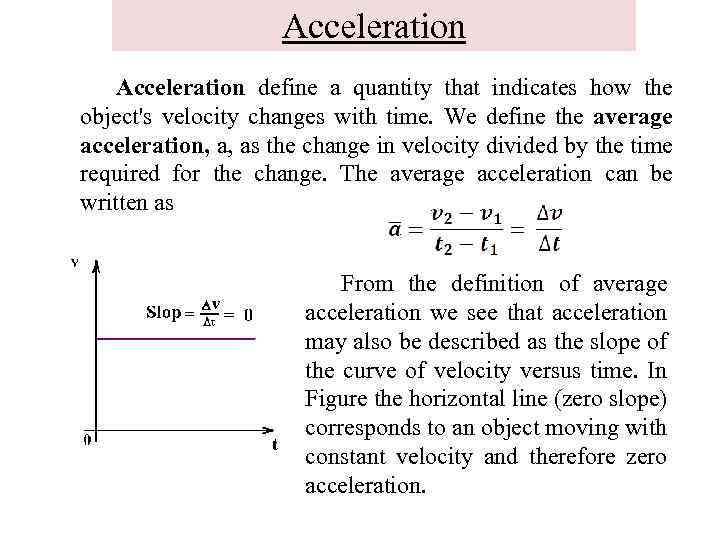

Acceleration define a quantity that indicates how the object's velocity changes with time. We define the average acceleration, a, as the change in velocity divided by the time required for the change. The average acceleration can be written as From the definition of average acceleration we see that acceleration may also be described as the slope of the curve of velocity versus time. In Figure the horizontal line (zero slope) corresponds to an object moving with constant velocity and therefore zero acceleration.

Acceleration define a quantity that indicates how the object's velocity changes with time. We define the average acceleration, a, as the change in velocity divided by the time required for the change. The average acceleration can be written as From the definition of average acceleration we see that acceleration may also be described as the slope of the curve of velocity versus time. In Figure the horizontal line (zero slope) corresponds to an object moving with constant velocity and therefore zero acceleration.

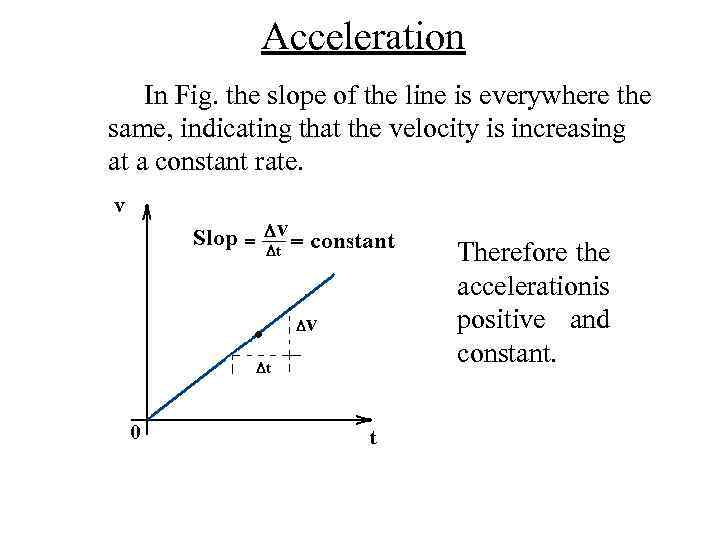

Acceleration In Fig. the slope of the line is everywhere the same, indicating that the velocity is increasing at a constant rate. Therefore the accelerationis positive and constant.

Acceleration In Fig. the slope of the line is everywhere the same, indicating that the velocity is increasing at a constant rate. Therefore the accelerationis positive and constant.

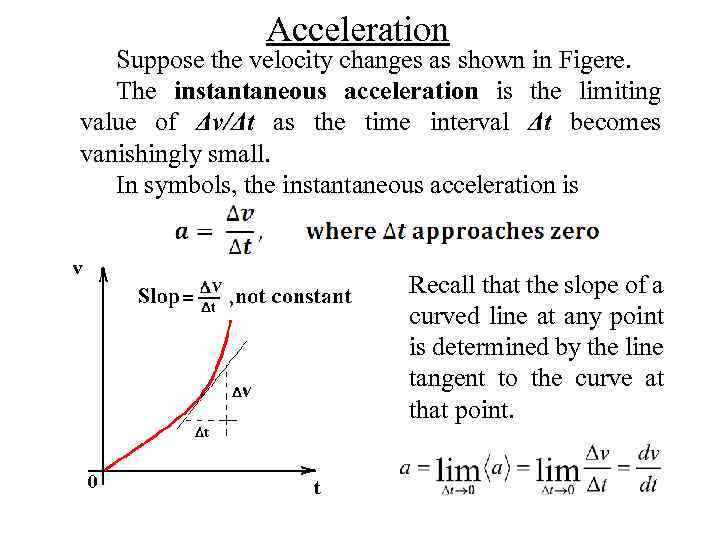

Acceleration Suppose the velocity changes as shown in Figere. The instantaneous acceleration is the limiting value of Δv/Δt as the time interval Δt becomes vanishingly small. In symbols, the instantaneous acceleration is Recall that the slope of a curved line at any point is determined by the line tangent to the curve at that point.

Acceleration Suppose the velocity changes as shown in Figere. The instantaneous acceleration is the limiting value of Δv/Δt as the time interval Δt becomes vanishingly small. In symbols, the instantaneous acceleration is Recall that the slope of a curved line at any point is determined by the line tangent to the curve at that point.

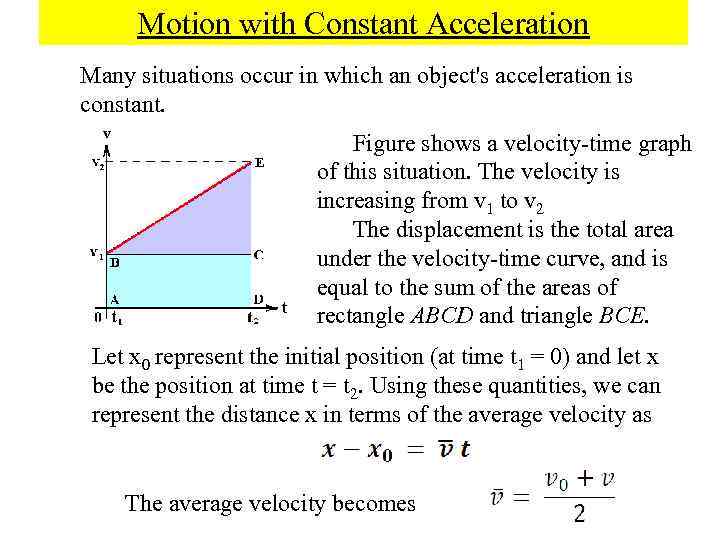

Motion with Constant Acceleration Many situations occur in which an object's acceleration is constant. Figure shows a velocity time graph of this situation. The velocity is increasing from v 1 to v 2 The displacement is the total area under the velocity time curve, and is equal to the sum of the areas of rectangle ABCD and triangle ВСЕ. Let x 0 represent the initial position (at time t 1 = 0) and let x be the position at time t = t 2. Using these quantities, we can represent the distance x in terms of the average velocity as The average velocity becomes

Motion with Constant Acceleration Many situations occur in which an object's acceleration is constant. Figure shows a velocity time graph of this situation. The velocity is increasing from v 1 to v 2 The displacement is the total area under the velocity time curve, and is equal to the sum of the areas of rectangle ABCD and triangle ВСЕ. Let x 0 represent the initial position (at time t 1 = 0) and let x be the position at time t = t 2. Using these quantities, we can represent the distance x in terms of the average velocity as The average velocity becomes

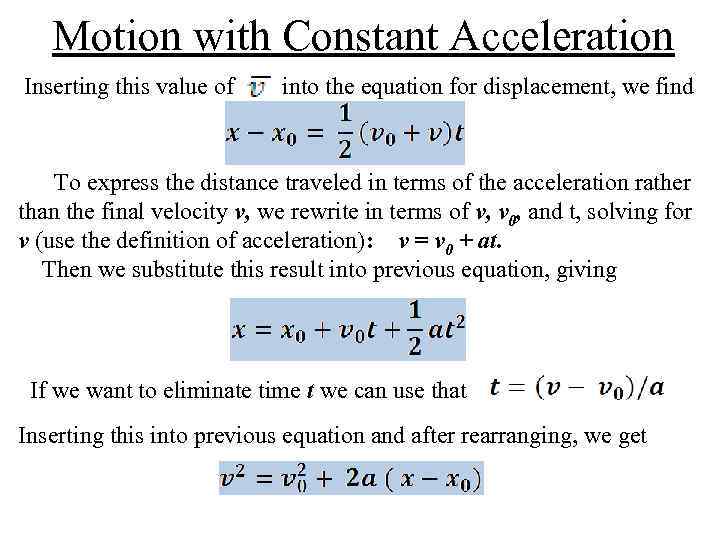

Motion with Constant Acceleration Inserting this value of into the equation for displacement, we find To express the distance traveled in terms of the acceleration rather than the final velocity v, we rewrite in terms of v, v 0, and t, solving for v (use the definition of acceleration): v = v 0 + at. Then we substitute this result into previous equation, giving If we want to eliminate time t we can use that Inserting this into previous equation and after rearranging, we get

Motion with Constant Acceleration Inserting this value of into the equation for displacement, we find To express the distance traveled in terms of the acceleration rather than the final velocity v, we rewrite in terms of v, v 0, and t, solving for v (use the definition of acceleration): v = v 0 + at. Then we substitute this result into previous equation, giving If we want to eliminate time t we can use that Inserting this into previous equation and after rearranging, we get

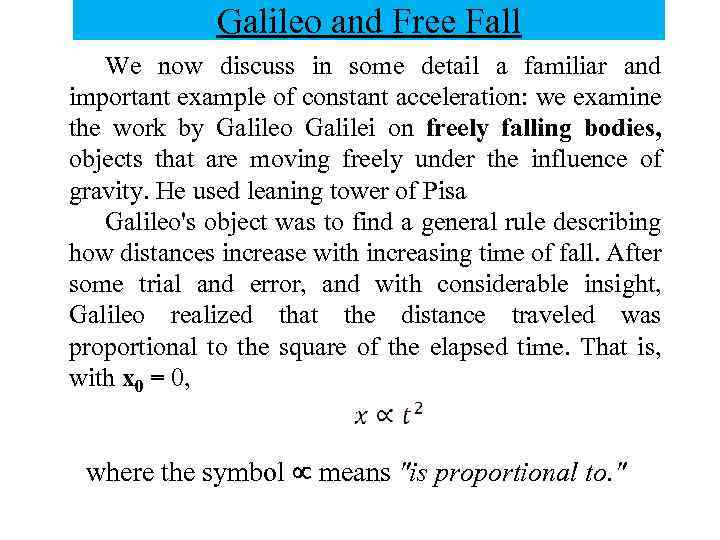

Galileo and Free Fall We now discuss in some detail a familiar and important example of constant acceleration: we examine the work by Galileo Galilei on freely falling bodies, objects that are moving freely under the influence of gravity. He used leaning tower of Pisa Galileo's object was to find a general rule describing how distances increase with increasing time of fall. After some trial and error, and with considerable insight, Galileo realized that the distance traveled was proportional to the square of the elapsed time. That is, with x 0 = 0, where the symbol means "is proportional to. "

Galileo and Free Fall We now discuss in some detail a familiar and important example of constant acceleration: we examine the work by Galileo Galilei on freely falling bodies, objects that are moving freely under the influence of gravity. He used leaning tower of Pisa Galileo's object was to find a general rule describing how distances increase with increasing time of fall. After some trial and error, and with considerable insight, Galileo realized that the distance traveled was proportional to the square of the elapsed time. That is, with x 0 = 0, where the symbol means "is proportional to. "

Galileo and Free Fall Galileo further deduced from his observations that heavy objects fall in the same way that light objects do. Some thirty years later, Robert Boyle, in a series of experiments made possible by his new vacuum pump, showed that this observation is strictly true for bodies falling without the retarding effect of air resistance. Therefore we can write the relation between distance and time squared as an equality, where the proportionality constant к does not depend on the nature of the falling object:

Galileo and Free Fall Galileo further deduced from his observations that heavy objects fall in the same way that light objects do. Some thirty years later, Robert Boyle, in a series of experiments made possible by his new vacuum pump, showed that this observation is strictly true for bodies falling without the retarding effect of air resistance. Therefore we can write the relation between distance and time squared as an equality, where the proportionality constant к does not depend on the nature of the falling object:

Leaning tower of Pisa 42

Leaning tower of Pisa 42

Relative Velocity is not an absolute quantity but is measured relative to other objects. Thus to measure an object's velocity we must first specify the coordinate system or frame of reference in which the measurement is to be made.

Relative Velocity is not an absolute quantity but is measured relative to other objects. Thus to measure an object's velocity we must first specify the coordinate system or frame of reference in which the measurement is to be made.

Relative Velocity When we say that an automobile is traveling 90 km/h, we usually mean that it is going 90 km/h relative to the road. Imagine that you are driving down the highway at 90 km/h when another car passes you at 100 km/h. Although both cars are moving rapidly down the road, the faster car appears to overtake you very slowly. Relative to a coordinate system fixed on your car, the passing car is going only 100 km/h 90 km/h = 10 km/h.

Relative Velocity When we say that an automobile is traveling 90 km/h, we usually mean that it is going 90 km/h relative to the road. Imagine that you are driving down the highway at 90 km/h when another car passes you at 100 km/h. Although both cars are moving rapidly down the road, the faster car appears to overtake you very slowly. Relative to a coordinate system fixed on your car, the passing car is going only 100 km/h 90 km/h = 10 km/h.

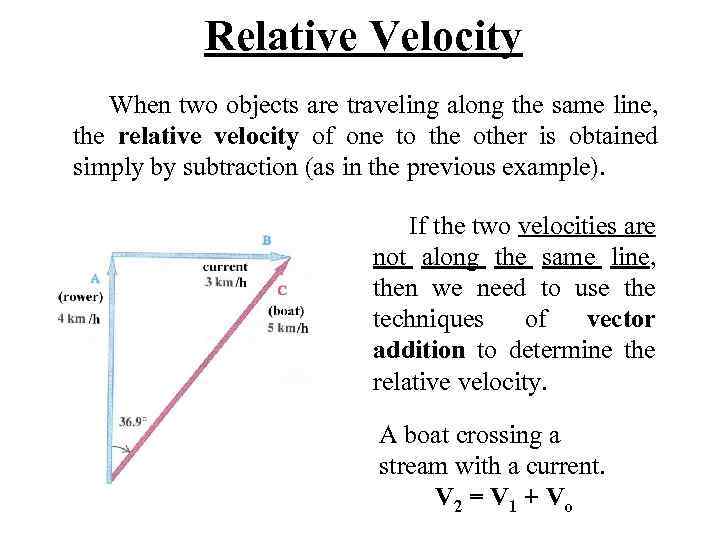

Relative Velocity When two objects are traveling along the same line, the relative velocity of one to the other is obtained simply by subtraction (as in the previous example). If the two velocities are not along the same line, then we need to use the techniques of vector addition to determine the relative velocity. A boat crossing a stream with a current. V 2 = V 1 + V o

Relative Velocity When two objects are traveling along the same line, the relative velocity of one to the other is obtained simply by subtraction (as in the previous example). If the two velocities are not along the same line, then we need to use the techniques of vector addition to determine the relative velocity. A boat crossing a stream with a current. V 2 = V 1 + V o

Resolution of Vectors It is often useful to represent a vector as the sum of two or three other vectors. We call these other vectors components, and they are especially convenient when we choose components at right angles to each other. In two dimensions we frequently choose these component vectors to lie along the x and у axes of a rectangular (Cartesian) coordinate system.

Resolution of Vectors It is often useful to represent a vector as the sum of two or three other vectors. We call these other vectors components, and they are especially convenient when we choose components at right angles to each other. In two dimensions we frequently choose these component vectors to lie along the x and у axes of a rectangular (Cartesian) coordinate system.

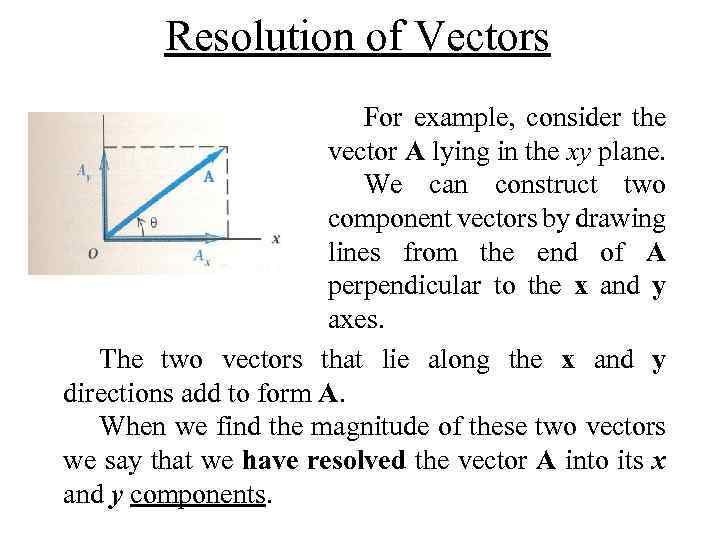

Resolution of Vectors For example, consider the vector A lying in the xy plane. We can construct two component vectors by drawing lines from the end of A perpendicular to the x and у axes. The two vectors that lie along the x and у directions add to form A. When we find the magnitude of these two vectors we say that we have resolved the vector A into its x and у components.

Resolution of Vectors For example, consider the vector A lying in the xy plane. We can construct two component vectors by drawing lines from the end of A perpendicular to the x and у axes. The two vectors that lie along the x and у directions add to form A. When we find the magnitude of these two vectors we say that we have resolved the vector A into its x and у components.

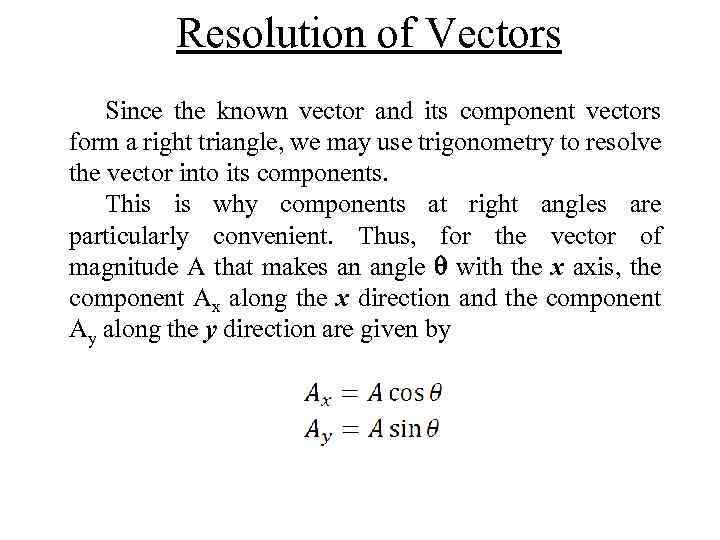

Resolution of Vectors Since the known vector and its component vectors form a right triangle, we may use trigonometry to resolve the vector into its components. This is why components at right angles are particularly convenient. Thus, for the vector of magnitude A that makes an angle q with the x axis, the component Ax along the x direction and the component Ay along the у direction are given by

Resolution of Vectors Since the known vector and its component vectors form a right triangle, we may use trigonometry to resolve the vector into its components. This is why components at right angles are particularly convenient. Thus, for the vector of magnitude A that makes an angle q with the x axis, the component Ax along the x direction and the component Ay along the у direction are given by

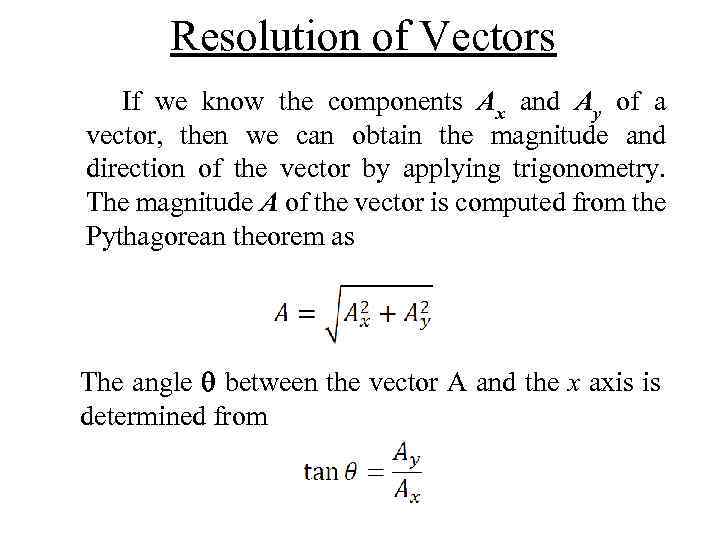

Resolution of Vectors If we know the components Ax and Ay of a vector, then we can obtain the magnitude and direction of the vector by applying trigonometry. The magnitude A of the vector is computed from the Pythagorean theorem as The angle q between the vector A and the x axis is determined from

Resolution of Vectors If we know the components Ax and Ay of a vector, then we can obtain the magnitude and direction of the vector by applying trigonometry. The magnitude A of the vector is computed from the Pythagorean theorem as The angle q between the vector A and the x axis is determined from

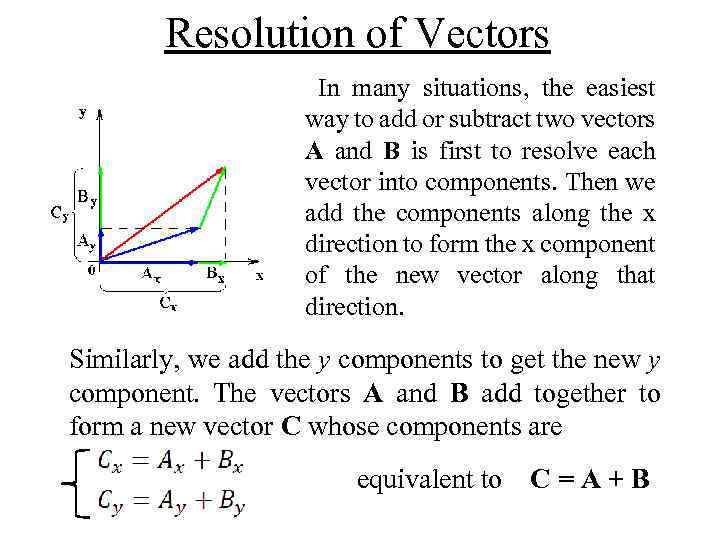

Resolution of Vectors In many situations, the easiest way to add or subtract two vectors A and В is first to resolve each vector into components. Then we add the components along the x direction to form the x component of the new vector along that direction. Similarly, we add the у components to get the new у component. The vectors A and В add together to form a new vector С whose components are equivalent to C=A+B

Resolution of Vectors In many situations, the easiest way to add or subtract two vectors A and В is first to resolve each vector into components. Then we add the components along the x direction to form the x component of the new vector along that direction. Similarly, we add the у components to get the new у component. The vectors A and В add together to form a new vector С whose components are equivalent to C=A+B

Resolution of Vectors If two vectors A and В are to be subtracted, we can use the same procedure of resolving each vector into components and subtracting them in proper order. To this point we have considered the addition or subtraction of two vectors that lie in the same plane. Other cases occur in nature in which the vectors occupy three dimensions, rather than two. Although we will not deal with such cases very often in this text, we will state the basic principle for adding and subtracting vectors in three dimensions. The vectors to be added (or subtracted) are resolved into components along the x, y, and z axes and the components are added (or subtracted). This procedure is the same as that used for vectors lying in a plane except that there are three rather than two dimensions.

Resolution of Vectors If two vectors A and В are to be subtracted, we can use the same procedure of resolving each vector into components and subtracting them in proper order. To this point we have considered the addition or subtraction of two vectors that lie in the same plane. Other cases occur in nature in which the vectors occupy three dimensions, rather than two. Although we will not deal with such cases very often in this text, we will state the basic principle for adding and subtracting vectors in three dimensions. The vectors to be added (or subtracted) are resolved into components along the x, y, and z axes and the components are added (or subtracted). This procedure is the same as that used for vectors lying in a plane except that there are three rather than two dimensions.

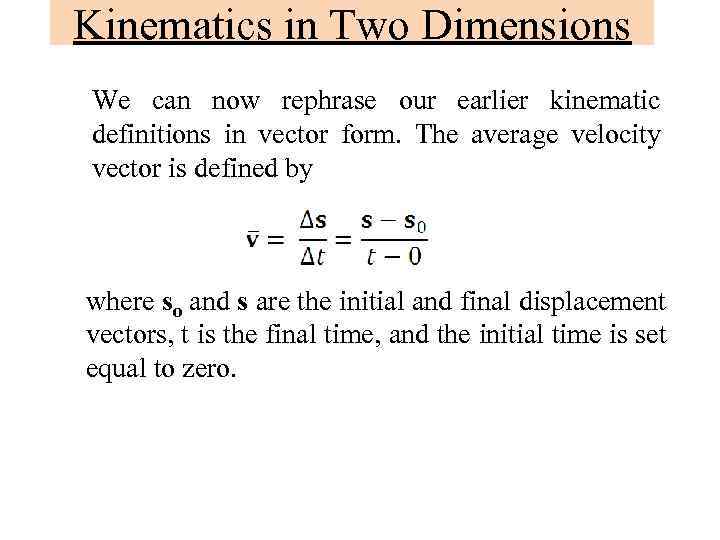

Kinematics in Two Dimensions We can now rephrase our earlier kinematic definitions in vector form. The average velocity vector is defined by where so and s are the initial and final displacement vectors, t is the final time, and the initial time is set equal to zero.

Kinematics in Two Dimensions We can now rephrase our earlier kinematic definitions in vector form. The average velocity vector is defined by where so and s are the initial and final displacement vectors, t is the final time, and the initial time is set equal to zero.

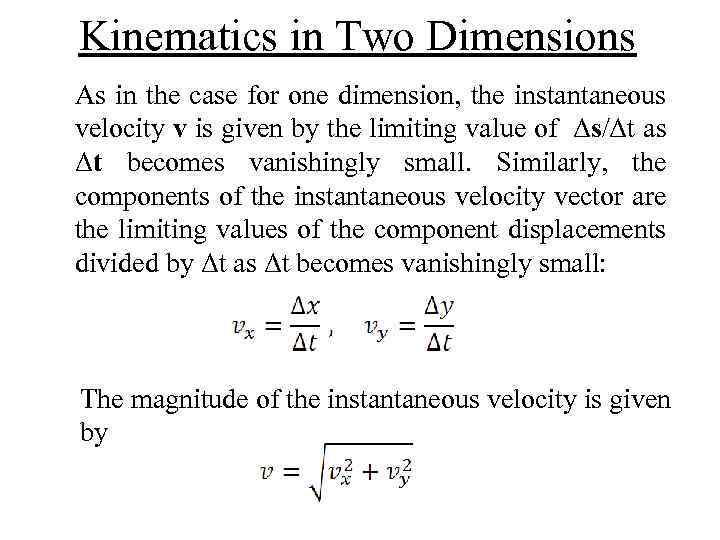

Kinematics in Two Dimensions As in the case for one dimension, the instantaneous velocity v is given by the limiting value of Δs/Δt as Δt becomes vanishingly small. Similarly, the components of the instantaneous velocity vector are the limiting values of the component displacements divided by Δt as Δt becomes vanishingly small: The magnitude of the instantaneous velocity is given by

Kinematics in Two Dimensions As in the case for one dimension, the instantaneous velocity v is given by the limiting value of Δs/Δt as Δt becomes vanishingly small. Similarly, the components of the instantaneous velocity vector are the limiting values of the component displacements divided by Δt as Δt becomes vanishingly small: The magnitude of the instantaneous velocity is given by

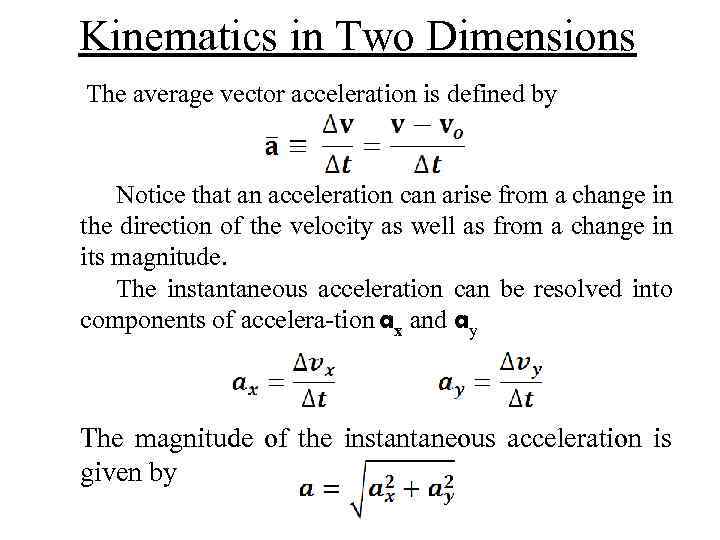

Kinematics in Two Dimensions The average vector acceleration is defined by Notice that an acceleration can arise from a change in the direction of the velocity as well as from a change in its magnitude. The instantaneous acceleration can be resolved into components of accelera tion ax and ay The magnitude of the instantaneous acceleration is given by

Kinematics in Two Dimensions The average vector acceleration is defined by Notice that an acceleration can arise from a change in the direction of the velocity as well as from a change in its magnitude. The instantaneous acceleration can be resolved into components of accelera tion ax and ay The magnitude of the instantaneous acceleration is given by

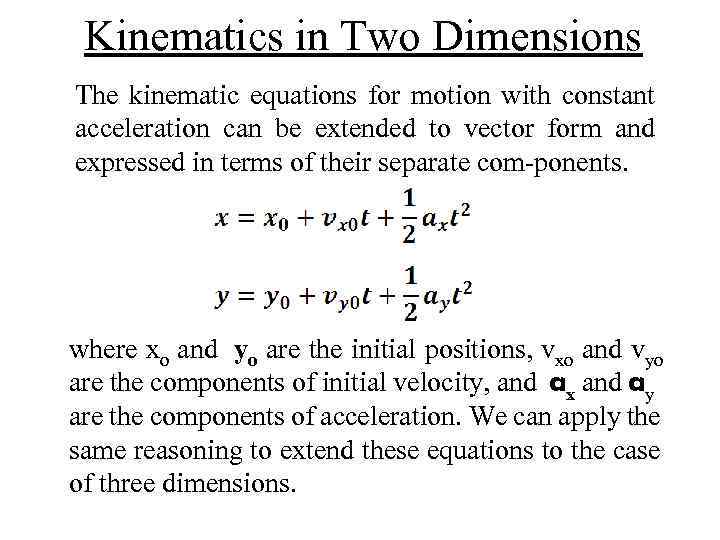

Kinematics in Two Dimensions The kinematic equations for motion with constant acceleration can be extended to vector form and expressed in terms of their separate com ponents. where xo and yo are the initial positions, vxo and vyo are the components of initial velocity, and ax and ay are the components of acceleration. We can apply the same reasoning to extend these equations to the case of three dimensions.

Kinematics in Two Dimensions The kinematic equations for motion with constant acceleration can be extended to vector form and expressed in terms of their separate com ponents. where xo and yo are the initial positions, vxo and vyo are the components of initial velocity, and ax and ay are the components of acceleration. We can apply the same reasoning to extend these equations to the case of three dimensions.

![Projectile motion Galileo observed that we could think of the projectile [prə'ʤektaɪl] motion as Projectile motion Galileo observed that we could think of the projectile [prə'ʤektaɪl] motion as](https://present5.com/presentation/231541200_437981139/image-56.jpg) Projectile motion Galileo observed that we could think of the projectile [prə'ʤektaɪl] motion as consisting of a horizontal part with constant speed and a vertical part with constant downward acceleration. Each of these motions is independent of the other, but their combination describes the motion of the projectile. For example, a ball thrown horizontally from a bridge falls with the same downward acceleration as a ball that is simply dropped. The downward motion is unaffected by the horizontal motion. Thus the ball thrown horizontally reaches the river at the same time as the ball dropped vertically, a result predicted by Galileo.

Projectile motion Galileo observed that we could think of the projectile [prə'ʤektaɪl] motion as consisting of a horizontal part with constant speed and a vertical part with constant downward acceleration. Each of these motions is independent of the other, but their combination describes the motion of the projectile. For example, a ball thrown horizontally from a bridge falls with the same downward acceleration as a ball that is simply dropped. The downward motion is unaffected by the horizontal motion. Thus the ball thrown horizontally reaches the river at the same time as the ball dropped vertically, a result predicted by Galileo.

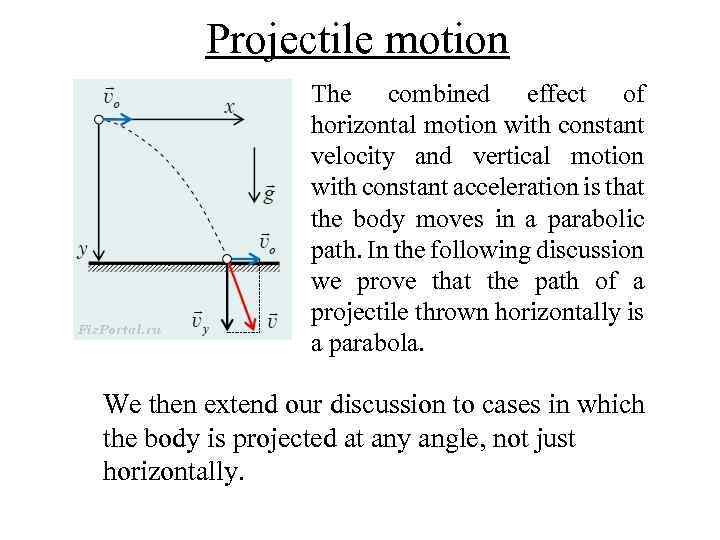

Projectile motion The combined effect of horizontal motion with constant velocity and vertical motion with constant acceleration is that the body moves in a parabolic path. In the following discussion we prove that the path of a projectile thrown horizontally is a parabola. We then extend our discussion to cases in which the body is projected at any angle, not just horizontally.

Projectile motion The combined effect of horizontal motion with constant velocity and vertical motion with constant acceleration is that the body moves in a parabolic path. In the following discussion we prove that the path of a projectile thrown horizontally is a parabola. We then extend our discussion to cases in which the body is projected at any angle, not just horizontally.

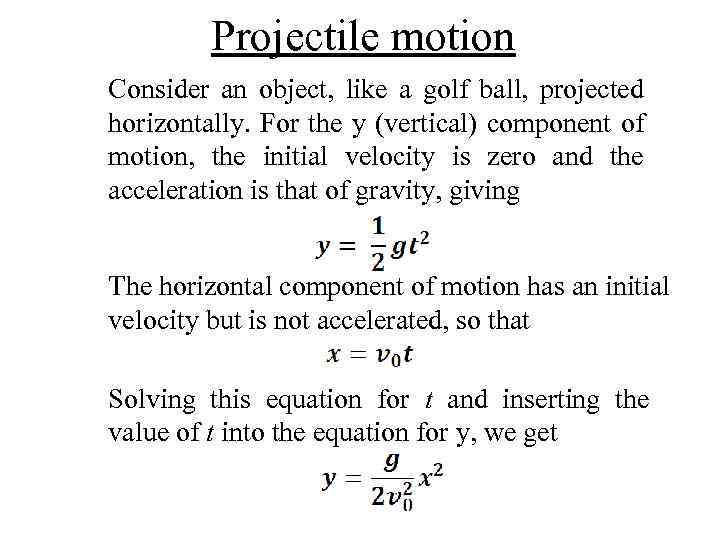

Projectile motion Consider an object, like a golf ball, projected horizontally. For the у (vertical) component of motion, the initial velocity is zero and the acceleration is that of gravity, giving The horizontal component of motion has an initial velocity but is not accelerated, so that Solving this equation for t and inserting the value of t into the equation for y, we get

Projectile motion Consider an object, like a golf ball, projected horizontally. For the у (vertical) component of motion, the initial velocity is zero and the acceleration is that of gravity, giving The horizontal component of motion has an initial velocity but is not accelerated, so that Solving this equation for t and inserting the value of t into the equation for y, we get

Projectile motion Equation has the same form as the equation for a parabola. In both cases the factor that is multiplied by x 2 on the right hand side is a constant for a particular problem. Thus we conclude that projectile motion is parabolic. A more detailed analysis would take account of air resistance, which causes a departure from a true parabolic path in many real situations. In this course, we will consider air resistance to be negligible unless stated otherwise.

Projectile motion Equation has the same form as the equation for a parabola. In both cases the factor that is multiplied by x 2 on the right hand side is a constant for a particular problem. Thus we conclude that projectile motion is parabolic. A more detailed analysis would take account of air resistance, which causes a departure from a true parabolic path in many real situations. In this course, we will consider air resistance to be negligible unless stated otherwise.

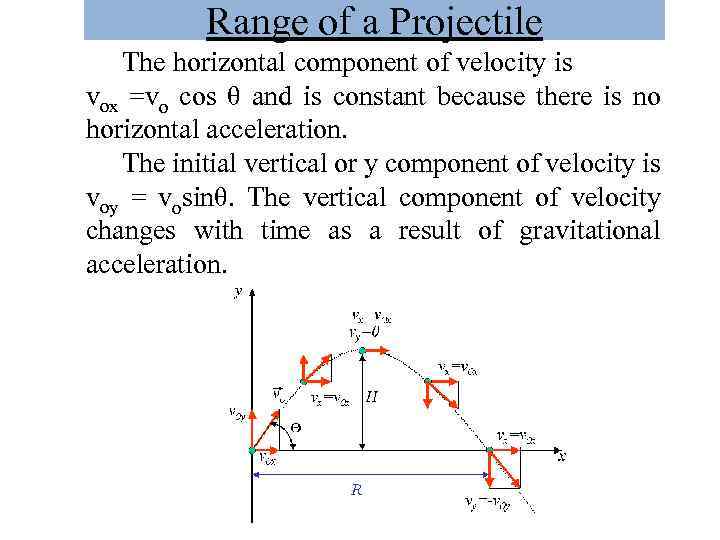

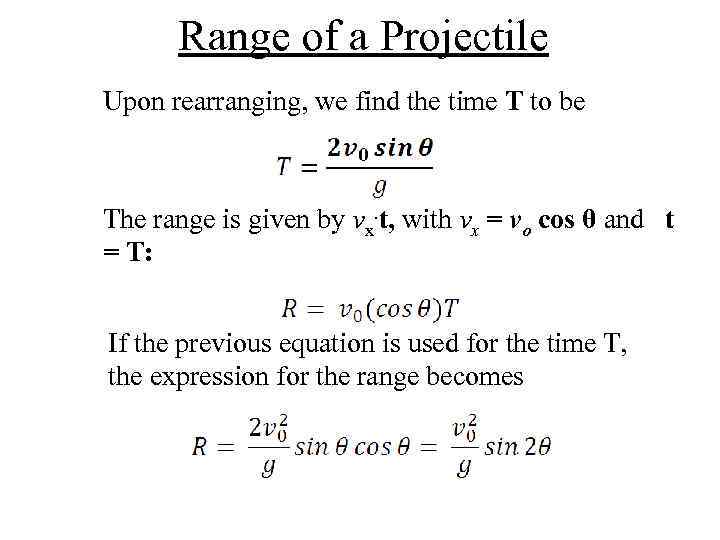

Range of a Projectile The horizontal component of velocity is vox =vo cos θ and is constant because there is no horizontal acceleration. The initial vertical or у component of velocity is voy = vosinθ. The vertical component of velocity changes with time as a result of gravitational acceleration.

Range of a Projectile The horizontal component of velocity is vox =vo cos θ and is constant because there is no horizontal acceleration. The initial vertical or у component of velocity is voy = vosinθ. The vertical component of velocity changes with time as a result of gravitational acceleration.

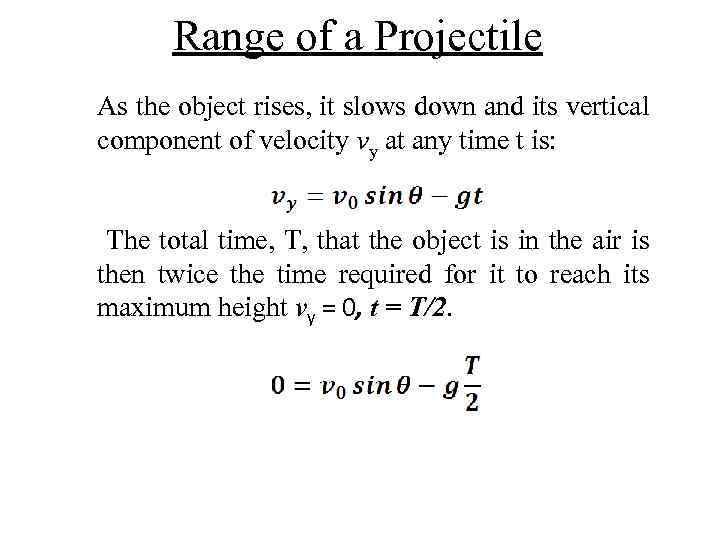

Range of a Projectile As the object rises, it slows down and its vertical component of velocity vy at any time t is: The total time, T, that the object is in the air is then twice the time required for it to reach its maximum height vy = 0, t = T/2.

Range of a Projectile As the object rises, it slows down and its vertical component of velocity vy at any time t is: The total time, T, that the object is in the air is then twice the time required for it to reach its maximum height vy = 0, t = T/2.

Range of a Projectile Upon rearranging, we find the time T to be The range is given by vx. t, with vx = vo cos θ and t = T: If the previous equation is used for the time T, the expression for the range becomes

Range of a Projectile Upon rearranging, we find the time T to be The range is given by vx. t, with vx = vo cos θ and t = T: If the previous equation is used for the time T, the expression for the range becomes