dcd9039559a8b810deea87ace26197a8.ppt

- Количество слайдов: 62

Phylogenetic Tree Reconstruction Tandy Warnow The Program in Evolutionary Dynamics at Harvard University The University of Texas at Austin

Phylogenetic Tree Reconstruction Tandy Warnow The Program in Evolutionary Dynamics at Harvard University The University of Texas at Austin

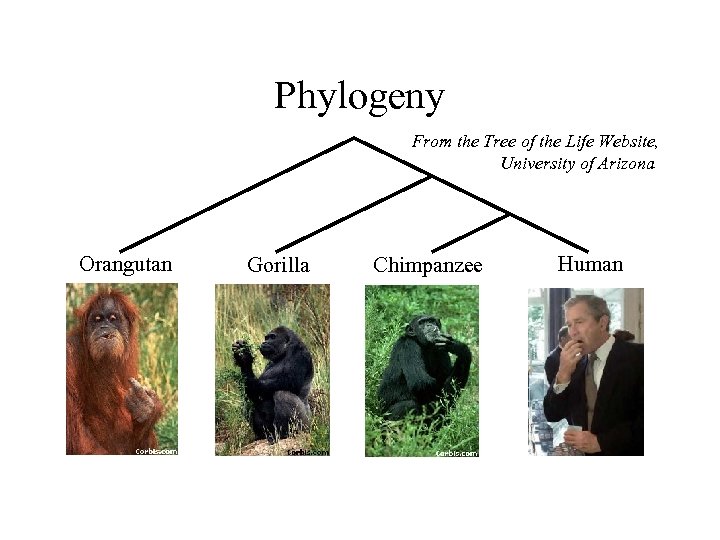

Phylogeny From the Tree of the Life Website, University of Arizona Orangutan Gorilla Chimpanzee Human

Phylogeny From the Tree of the Life Website, University of Arizona Orangutan Gorilla Chimpanzee Human

Reconstructing the “Tree” of Life Handling large datasets: millions of species

Reconstructing the “Tree” of Life Handling large datasets: millions of species

Cyber Infrastructure for Phylogenetic Research Purpose: to create a national infrastructure of hardware, algorithms, database technology, etc. , necessary to infer the Tree of Life. Group: 40 biologists, computer scientists, and mathematicians from 13 institutions. Funding: $11. 6 M (large ITR grant from NSF).

Cyber Infrastructure for Phylogenetic Research Purpose: to create a national infrastructure of hardware, algorithms, database technology, etc. , necessary to infer the Tree of Life. Group: 40 biologists, computer scientists, and mathematicians from 13 institutions. Funding: $11. 6 M (large ITR grant from NSF).

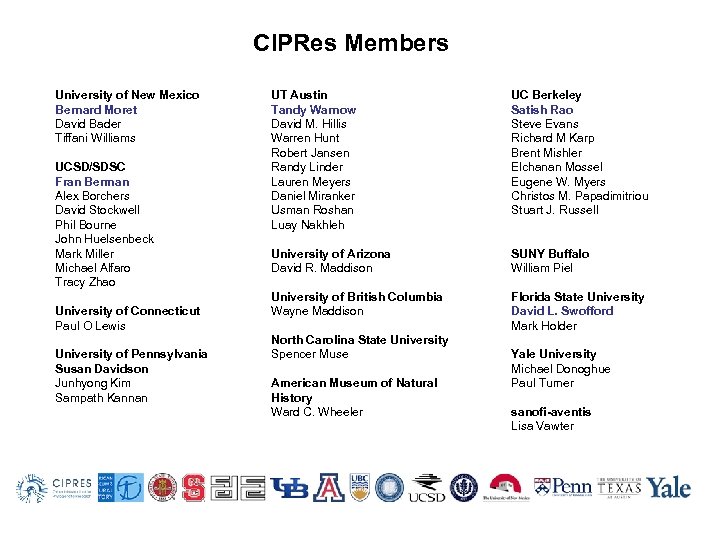

CIPRes Members University of New Mexico Bernard Moret David Bader Tiffani Williams UCSD/SDSC Fran Berman Alex Borchers David Stockwell Phil Bourne John Huelsenbeck Mark Miller Michael Alfaro Tracy Zhao University of Connecticut Paul O Lewis University of Pennsylvania Susan Davidson Junhyong Kim Sampath Kannan UT Austin Tandy Warnow David M. Hillis Warren Hunt Robert Jansen Randy Linder Lauren Meyers Daniel Miranker Usman Roshan Luay Nakhleh UC Berkeley Satish Rao Steve Evans Richard M Karp Brent Mishler Elchanan Mossel Eugene W. Myers Christos M. Papadimitriou Stuart J. Russell University of Arizona David R. Maddison SUNY Buffalo William Piel University of British Columbia Wayne Maddison Florida State University David L. Swofford Mark Holder North Carolina State University Spencer Muse American Museum of Natural History Ward C. Wheeler Yale University Michael Donoghue Paul Turner sanofi-aventis Lisa Vawter

CIPRes Members University of New Mexico Bernard Moret David Bader Tiffani Williams UCSD/SDSC Fran Berman Alex Borchers David Stockwell Phil Bourne John Huelsenbeck Mark Miller Michael Alfaro Tracy Zhao University of Connecticut Paul O Lewis University of Pennsylvania Susan Davidson Junhyong Kim Sampath Kannan UT Austin Tandy Warnow David M. Hillis Warren Hunt Robert Jansen Randy Linder Lauren Meyers Daniel Miranker Usman Roshan Luay Nakhleh UC Berkeley Satish Rao Steve Evans Richard M Karp Brent Mishler Elchanan Mossel Eugene W. Myers Christos M. Papadimitriou Stuart J. Russell University of Arizona David R. Maddison SUNY Buffalo William Piel University of British Columbia Wayne Maddison Florida State University David L. Swofford Mark Holder North Carolina State University Spencer Muse American Museum of Natural History Ward C. Wheeler Yale University Michael Donoghue Paul Turner sanofi-aventis Lisa Vawter

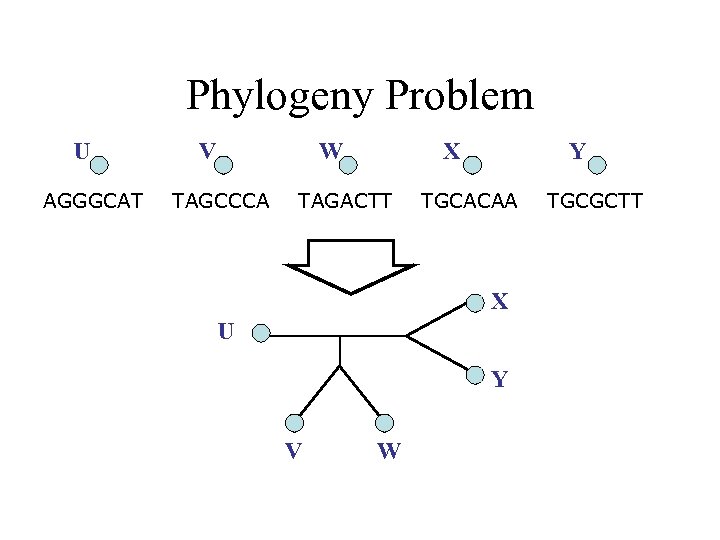

Phylogeny Problem U AGGGCAT V W TAGCCCA X TAGACTT Y TGCACAA X U Y V W TGCGCTT

Phylogeny Problem U AGGGCAT V W TAGCCCA X TAGACTT Y TGCACAA X U Y V W TGCGCTT

Steps in a phylogenetic analysis • Gather data • Align sequences • Reconstruct phylogeny on the multiple alignment often obtaining a large number of trees • Compute consensus (or otherwise estimate the reliable components of the evolutionary history) • Perform post-tree analyses.

Steps in a phylogenetic analysis • Gather data • Align sequences • Reconstruct phylogeny on the multiple alignment often obtaining a large number of trees • Compute consensus (or otherwise estimate the reliable components of the evolutionary history) • Perform post-tree analyses.

CIPRES research in algorithms • • • Heuristics for NP-hard problems in phylogeny reconstruction Compact representation of sets of trees Reticulate evolution reconstruction Performance of phylogeny reconstruction methods under stochastic models of evolution Gene order phylogeny Genomic alignment Lower bounds for MP Distance-based reconstruction Gene family evolution High-throughput phylogenetic placement Multiple sequence alignment

CIPRES research in algorithms • • • Heuristics for NP-hard problems in phylogeny reconstruction Compact representation of sets of trees Reticulate evolution reconstruction Performance of phylogeny reconstruction methods under stochastic models of evolution Gene order phylogeny Genomic alignment Lower bounds for MP Distance-based reconstruction Gene family evolution High-throughput phylogenetic placement Multiple sequence alignment

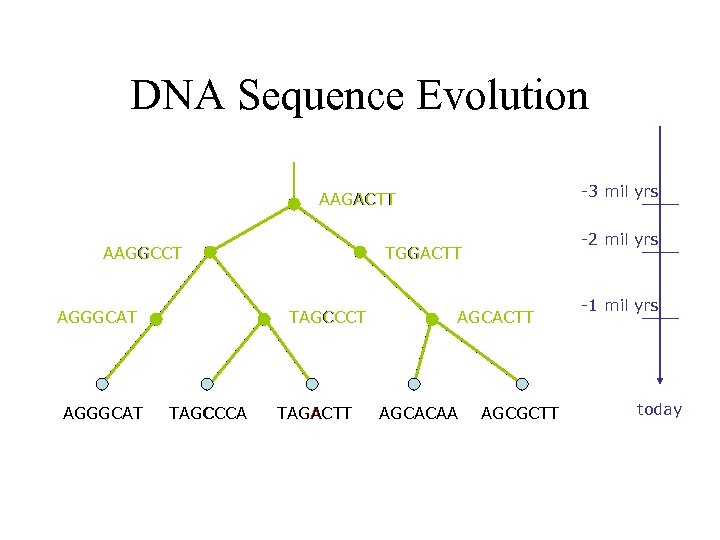

DNA Sequence Evolution -3 mil yrs AAGACTT AAGGCCT AGGGCAT TAGCCCA -2 mil yrs TGGACTT TAGACTT AGCACAA AGCGCTT -1 mil yrs today

DNA Sequence Evolution -3 mil yrs AAGACTT AAGGCCT AGGGCAT TAGCCCA -2 mil yrs TGGACTT TAGACTT AGCACAA AGCGCTT -1 mil yrs today

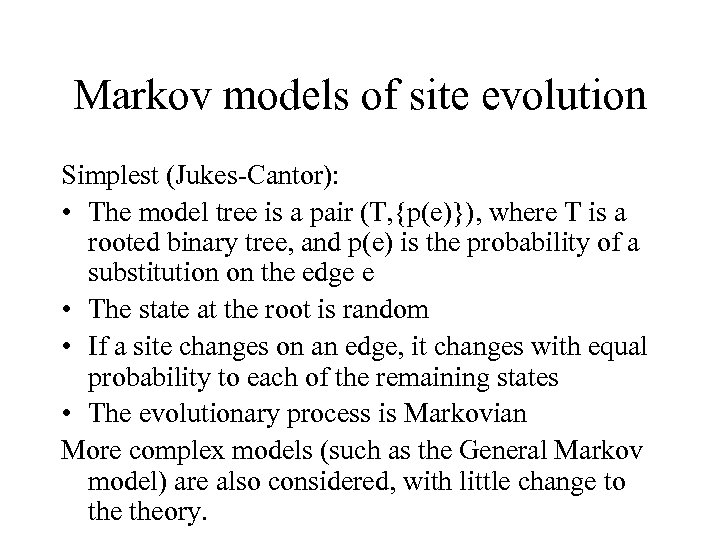

Markov models of site evolution Simplest (Jukes-Cantor): • The model tree is a pair (T, {p(e)}), where T is a rooted binary tree, and p(e) is the probability of a substitution on the edge e • The state at the root is random • If a site changes on an edge, it changes with equal probability to each of the remaining states • The evolutionary process is Markovian More complex models (such as the General Markov model) are also considered, with little change to theory.

Markov models of site evolution Simplest (Jukes-Cantor): • The model tree is a pair (T, {p(e)}), where T is a rooted binary tree, and p(e) is the probability of a substitution on the edge e • The state at the root is random • If a site changes on an edge, it changes with equal probability to each of the remaining states • The evolutionary process is Markovian More complex models (such as the General Markov model) are also considered, with little change to theory.

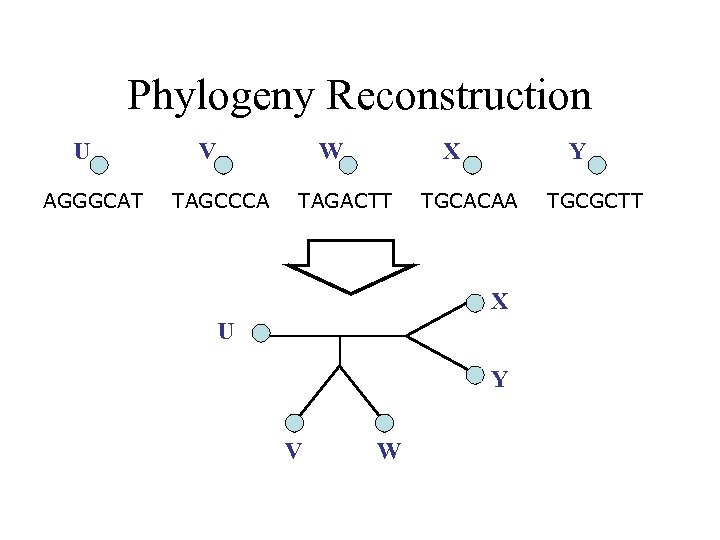

Phylogeny Reconstruction U AGGGCAT V W TAGCCCA X TAGACTT Y TGCACAA X U Y V W TGCGCTT

Phylogeny Reconstruction U AGGGCAT V W TAGCCCA X TAGACTT Y TGCACAA X U Y V W TGCGCTT

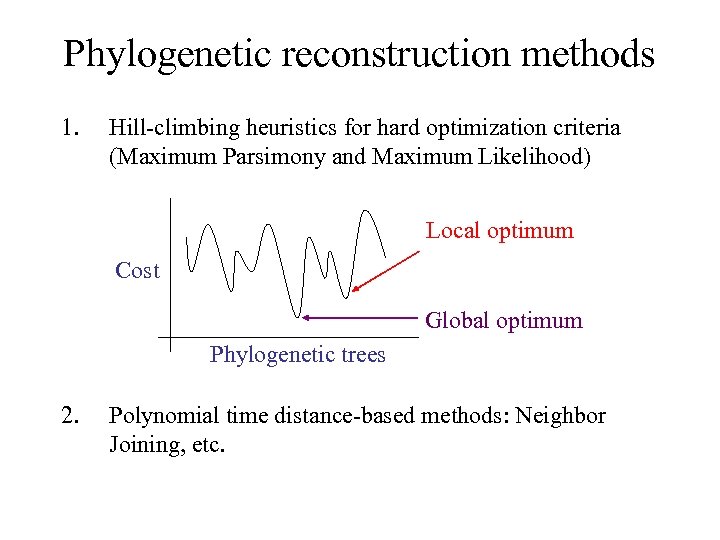

Phylogenetic reconstruction methods 1. Hill-climbing heuristics for hard optimization criteria (Maximum Parsimony and Maximum Likelihood) Local optimum Cost Global optimum Phylogenetic trees 2. Polynomial time distance-based methods: Neighbor Joining, etc.

Phylogenetic reconstruction methods 1. Hill-climbing heuristics for hard optimization criteria (Maximum Parsimony and Maximum Likelihood) Local optimum Cost Global optimum Phylogenetic trees 2. Polynomial time distance-based methods: Neighbor Joining, etc.

Performance criteria • Running time. • Space. • Statistical performance issues (e. g. , statistical consistency) with respect to a Markov model of evolution. • “Topological accuracy” with respect to the underlying true tree. Typically studied in simulation. • Accuracy with respect to a particular criterion (e. g. tree length or likelihood score), on real data.

Performance criteria • Running time. • Space. • Statistical performance issues (e. g. , statistical consistency) with respect to a Markov model of evolution. • “Topological accuracy” with respect to the underlying true tree. Typically studied in simulation. • Accuracy with respect to a particular criterion (e. g. tree length or likelihood score), on real data.

Maximum Parsimony • Input: Set S of n aligned sequences of length k • Output: A phylogenetic tree T – leaf-labeled by sequences in S – additional sequences of length k labeling the internal nodes of T such that is minimized.

Maximum Parsimony • Input: Set S of n aligned sequences of length k • Output: A phylogenetic tree T – leaf-labeled by sequences in S – additional sequences of length k labeling the internal nodes of T such that is minimized.

Theoretical results • Neighbor Joining is polynomial time, and statistically consistent under typical models of evolution. • Maximum Parsimony is NP-hard, and even exact solutions are not statistically consistent under typical models. • Maximum Likelihood is of unknown computational complexity, but statistically consistent under typical models.

Theoretical results • Neighbor Joining is polynomial time, and statistically consistent under typical models of evolution. • Maximum Parsimony is NP-hard, and even exact solutions are not statistically consistent under typical models. • Maximum Likelihood is of unknown computational complexity, but statistically consistent under typical models.

Problems with NJ • Theory: The convergence rate is exponential: the number of sites needed to obtain an accurate reconstruction of the tree with high probability grows exponentially in the evolutionary diameter. • Empirical: NJ has poor performance on datasets with some large leaf-to-leaf distances.

Problems with NJ • Theory: The convergence rate is exponential: the number of sites needed to obtain an accurate reconstruction of the tree with high probability grows exponentially in the evolutionary diameter. • Empirical: NJ has poor performance on datasets with some large leaf-to-leaf distances.

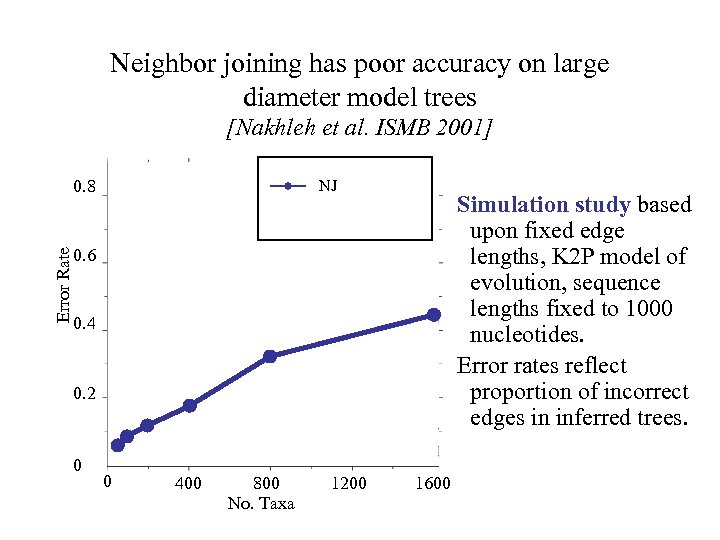

Neighbor joining has poor accuracy on large diameter model trees [Nakhleh et al. ISMB 2001] Error Rate 0. 8 NJ Simulation study based upon fixed edge lengths, K 2 P model of evolution, sequence lengths fixed to 1000 nucleotides. Error rates reflect proportion of incorrect edges in inferred trees. 0. 6 0. 4 0. 2 0 0 400 800 No. Taxa 1200 1600

Neighbor joining has poor accuracy on large diameter model trees [Nakhleh et al. ISMB 2001] Error Rate 0. 8 NJ Simulation study based upon fixed edge lengths, K 2 P model of evolution, sequence lengths fixed to 1000 nucleotides. Error rates reflect proportion of incorrect edges in inferred trees. 0. 6 0. 4 0. 2 0 0 400 800 No. Taxa 1200 1600

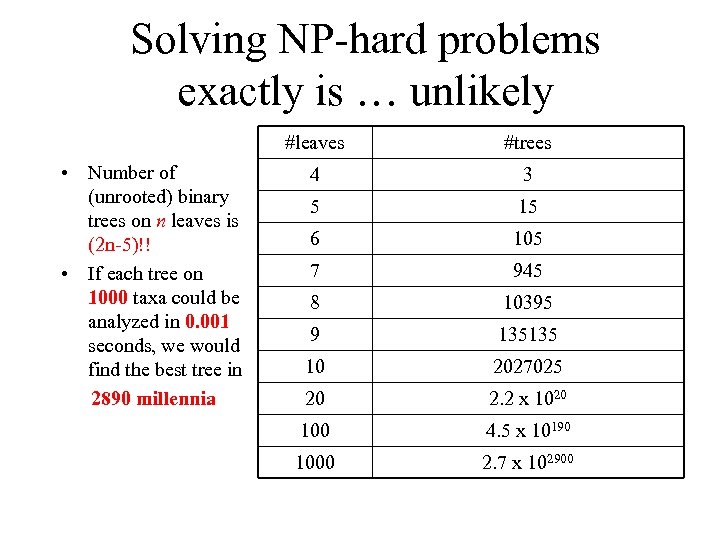

Solving NP-hard problems exactly is … unlikely #leaves • Number of (unrooted) binary trees on n leaves is (2 n-5)!! • If each tree on 1000 taxa could be analyzed in 0. 001 seconds, we would find the best tree in 2890 millennia #trees 4 3 5 15 6 105 7 945 8 10395 9 135135 10 2027025 20 2. 2 x 1020 100 4. 5 x 10190 1000 2. 7 x 102900

Solving NP-hard problems exactly is … unlikely #leaves • Number of (unrooted) binary trees on n leaves is (2 n-5)!! • If each tree on 1000 taxa could be analyzed in 0. 001 seconds, we would find the best tree in 2890 millennia #trees 4 3 5 15 6 105 7 945 8 10395 9 135135 10 2027025 20 2. 2 x 1020 100 4. 5 x 10190 1000 2. 7 x 102900

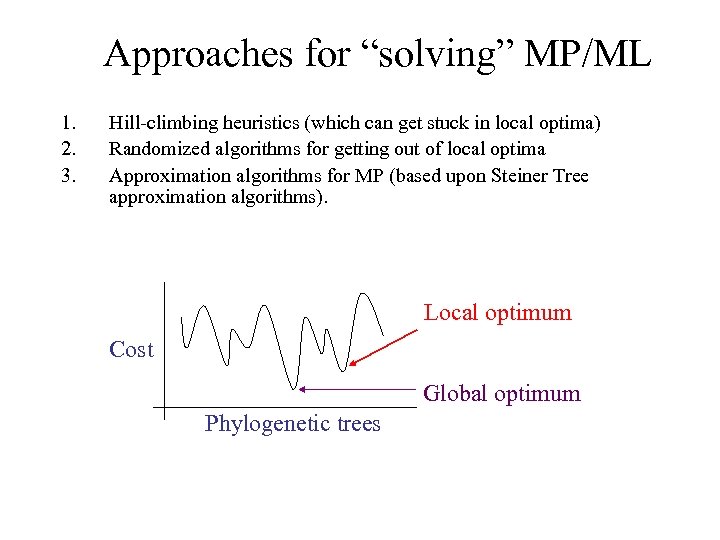

Approaches for “solving” MP/ML 1. 2. 3. Hill-climbing heuristics (which can get stuck in local optima) Randomized algorithms for getting out of local optima Approximation algorithms for MP (based upon Steiner Tree approximation algorithms). Local optimum Cost Global optimum Phylogenetic trees

Approaches for “solving” MP/ML 1. 2. 3. Hill-climbing heuristics (which can get stuck in local optima) Randomized algorithms for getting out of local optima Approximation algorithms for MP (based upon Steiner Tree approximation algorithms). Local optimum Cost Global optimum Phylogenetic trees

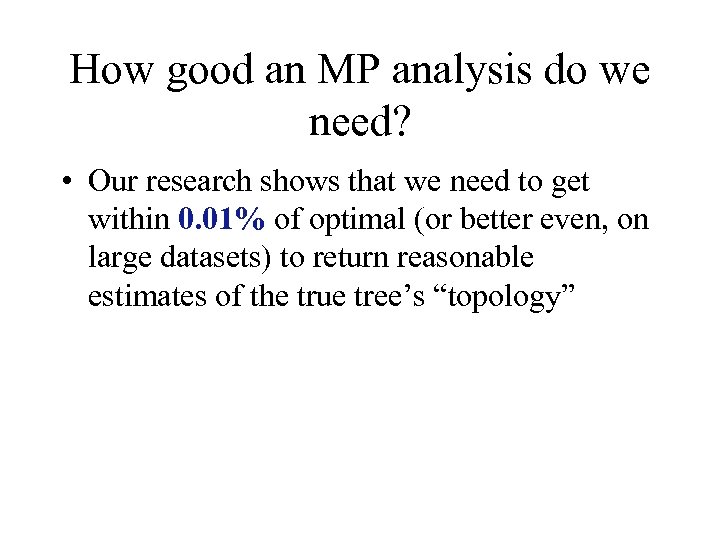

How good an MP analysis do we need? • Our research shows that we need to get within 0. 01% of optimal (or better even, on large datasets) to return reasonable estimates of the true tree’s “topology”

How good an MP analysis do we need? • Our research shows that we need to get within 0. 01% of optimal (or better even, on large datasets) to return reasonable estimates of the true tree’s “topology”

Datasets Obtained from various researchers and online databases • • • 1322 lsu r. RNA of all organisms 2000 Eukaryotic r. RNA 2594 rbc. L DNA 4583 Actinobacteria 16 s r. RNA 6590 ssu r. RNA of all Eukaryotes 7180 three-domain r. RNA 7322 Firmicutes bacteria 16 s r. RNA 8506 three-domain+2 org r. RNA 11361 ssu r. RNA of all Bacteria 13921 Proteobacteria 16 s r. RNA

Datasets Obtained from various researchers and online databases • • • 1322 lsu r. RNA of all organisms 2000 Eukaryotic r. RNA 2594 rbc. L DNA 4583 Actinobacteria 16 s r. RNA 6590 ssu r. RNA of all Eukaryotes 7180 three-domain r. RNA 7322 Firmicutes bacteria 16 s r. RNA 8506 three-domain+2 org r. RNA 11361 ssu r. RNA of all Bacteria 13921 Proteobacteria 16 s r. RNA

Problems with current techniques for MP Average MP scores above optimal of best methods at 24 hours across 10 datasets Best current techniques fail to reach 0. 01% of optimal at the end of 24 hours, on large datasets

Problems with current techniques for MP Average MP scores above optimal of best methods at 24 hours across 10 datasets Best current techniques fail to reach 0. 01% of optimal at the end of 24 hours, on large datasets

Problems with current techniques for MP Shown here is the performance of the TNT heuristic search for maximum parsimony on a real dataset of almost 14, 000 sequences. The required level of accuracy with respect to MP score is no more than 0. 01% error (otherwise high topological error results). (“Optimal” here means best score to date, using any method for any amount of time. ) Performance of TNT with time

Problems with current techniques for MP Shown here is the performance of the TNT heuristic search for maximum parsimony on a real dataset of almost 14, 000 sequences. The required level of accuracy with respect to MP score is no more than 0. 01% error (otherwise high topological error results). (“Optimal” here means best score to date, using any method for any amount of time. ) Performance of TNT with time

Empirical problems with existing methods • Heuristics for Maximum Parsimony (MP) and Maximum Likelihood (ML) cannot handle large datasets (take too long!) – we need new heuristics for MP/ML that can analyze large datasets • Polynomial time methods have poor topological accuracy on large datasets – we need better polynomial time methods

Empirical problems with existing methods • Heuristics for Maximum Parsimony (MP) and Maximum Likelihood (ML) cannot handle large datasets (take too long!) – we need new heuristics for MP/ML that can analyze large datasets • Polynomial time methods have poor topological accuracy on large datasets – we need better polynomial time methods

“Boosting” phylogeny reconstruction methods • DCMs “boost” the performance of phylogeny reconstruction methods. Base method M DCM-M

“Boosting” phylogeny reconstruction methods • DCMs “boost” the performance of phylogeny reconstruction methods. Base method M DCM-M

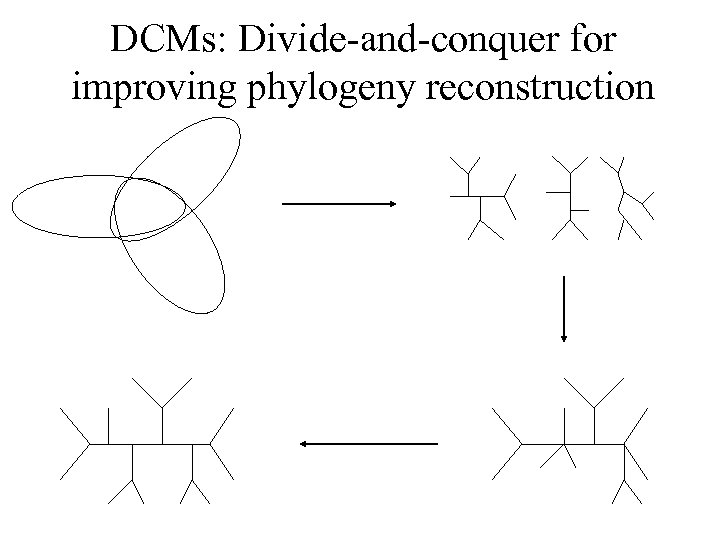

DCMs: Divide-and-conquer for improving phylogeny reconstruction

DCMs: Divide-and-conquer for improving phylogeny reconstruction

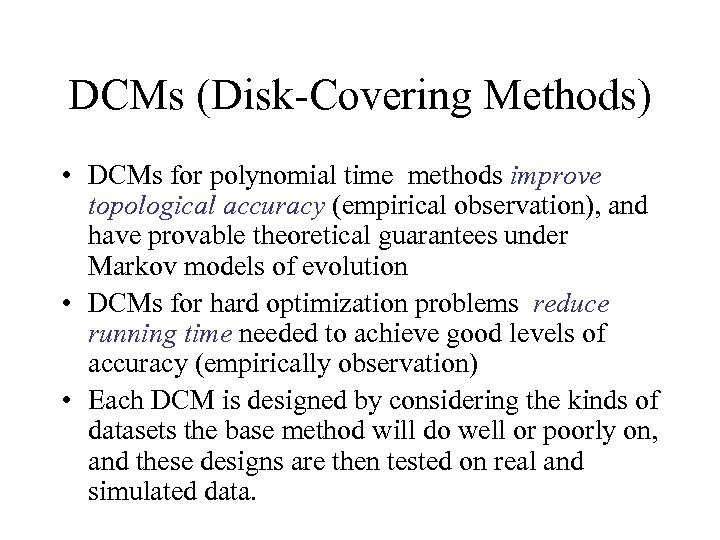

DCMs (Disk-Covering Methods) • DCMs for polynomial time methods improve topological accuracy (empirical observation), and have provable theoretical guarantees under Markov models of evolution • DCMs for hard optimization problems reduce running time needed to achieve good levels of accuracy (empirically observation) • Each DCM is designed by considering the kinds of datasets the base method will do well or poorly on, and these designs are then tested on real and simulated data.

DCMs (Disk-Covering Methods) • DCMs for polynomial time methods improve topological accuracy (empirical observation), and have provable theoretical guarantees under Markov models of evolution • DCMs for hard optimization problems reduce running time needed to achieve good levels of accuracy (empirically observation) • Each DCM is designed by considering the kinds of datasets the base method will do well or poorly on, and these designs are then tested on real and simulated data.

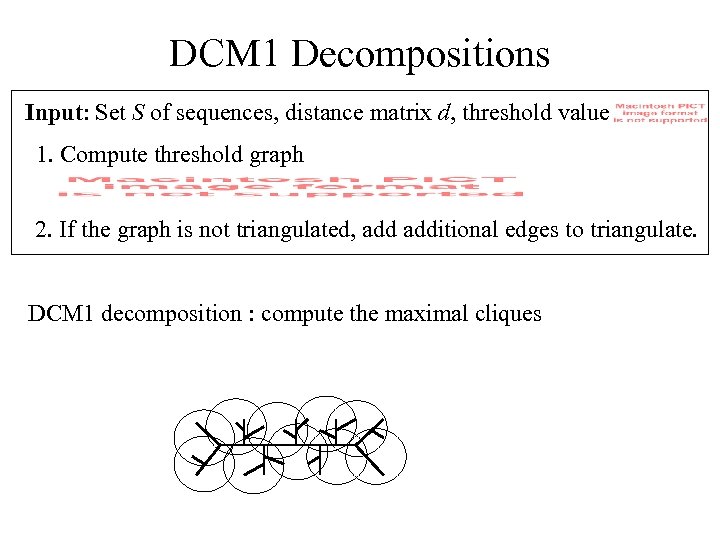

DCM 1 Decompositions Input: Set S of sequences, distance matrix d, threshold value 1. Compute threshold graph 2. If the graph is not triangulated, additional edges to triangulate. DCM 1 decomposition : compute the maximal cliques

DCM 1 Decompositions Input: Set S of sequences, distance matrix d, threshold value 1. Compute threshold graph 2. If the graph is not triangulated, additional edges to triangulate. DCM 1 decomposition : compute the maximal cliques

![DCM 1 -boosting distance-based methods [Nakhleh et al. ISMB 2001] Error Rate 0. 8 DCM 1 -boosting distance-based methods [Nakhleh et al. ISMB 2001] Error Rate 0. 8](https://present5.com/presentation/dcd9039559a8b810deea87ace26197a8/image-29.jpg) DCM 1 -boosting distance-based methods [Nakhleh et al. ISMB 2001] Error Rate 0. 8 NJ DCM 1 -NJ 0. 6 0. 4 0. 2 0 0 400 800 No. Taxa 1200 • DCM 1 -boosting makes distancebased methods more accurate • Theoretical guarantees that DCM 1 -NJ converges to the true tree from polynomial length 1600 sequences

DCM 1 -boosting distance-based methods [Nakhleh et al. ISMB 2001] Error Rate 0. 8 NJ DCM 1 -NJ 0. 6 0. 4 0. 2 0 0 400 800 No. Taxa 1200 • DCM 1 -boosting makes distancebased methods more accurate • Theoretical guarantees that DCM 1 -NJ converges to the true tree from polynomial length 1600 sequences

Major challenge: MP and ML • Maximum Parsimony (MP) and Maximum Likelihood (ML) remain the methods of choice for most systematists • The main challenge here is to make it possible to obtain good solutions to MP or ML in reasonable time periods on large datasets

Major challenge: MP and ML • Maximum Parsimony (MP) and Maximum Likelihood (ML) remain the methods of choice for most systematists • The main challenge here is to make it possible to obtain good solutions to MP or ML in reasonable time periods on large datasets

Maximum Parsimony • Input: Set S of n aligned sequences of length k • Output: A phylogenetic tree T – leaf-labeled by sequences in S – additional sequences of length k labeling the internal nodes of T such that is minimized.

Maximum Parsimony • Input: Set S of n aligned sequences of length k • Output: A phylogenetic tree T – leaf-labeled by sequences in S – additional sequences of length k labeling the internal nodes of T such that is minimized.

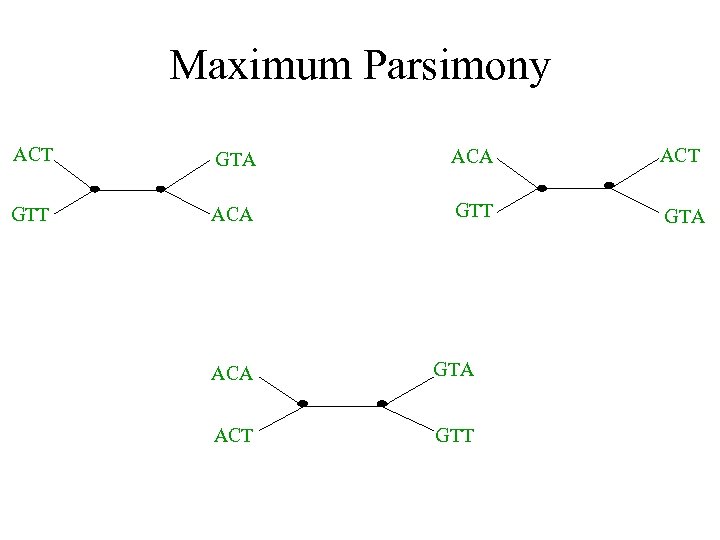

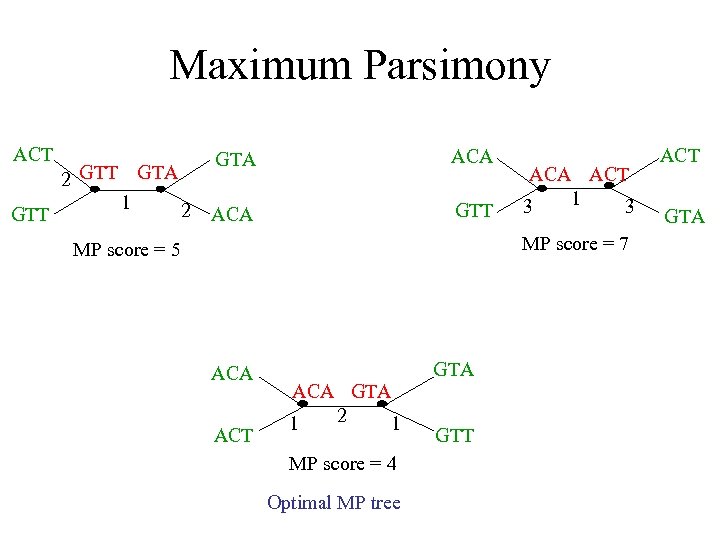

Maximum parsimony (example) • Input: Four sequences – ACT – ACA – GTT – GTA • Question: which of the three trees has the best MP scores?

Maximum parsimony (example) • Input: Four sequences – ACT – ACA – GTT – GTA • Question: which of the three trees has the best MP scores?

Maximum Parsimony ACT GTA ACT GTT ACA GTT GTA ACA GTA ACT GTT

Maximum Parsimony ACT GTA ACT GTT ACA GTT GTA ACA GTA ACT GTT

Maximum Parsimony ACT GTT 2 GTT GTA 1 2 GTA ACA GTT ACA ACT 1 3 3 MP score = 7 MP score = 5 ACA ACT GTA ACA GTA 2 1 1 MP score = 4 Optimal MP tree GTT ACT GTA

Maximum Parsimony ACT GTT 2 GTT GTA 1 2 GTA ACA GTT ACA ACT 1 3 3 MP score = 7 MP score = 5 ACA ACT GTA ACA GTA 2 1 1 MP score = 4 Optimal MP tree GTT ACT GTA

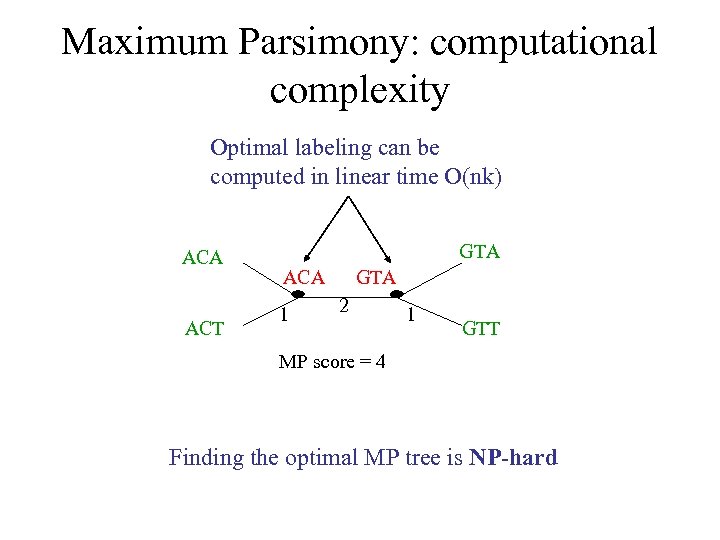

Maximum Parsimony: computational complexity Optimal labeling can be computed in linear time O(nk) ACA ACT GTA ACA 1 GTA 2 1 GTT MP score = 4 Finding the optimal MP tree is NP-hard

Maximum Parsimony: computational complexity Optimal labeling can be computed in linear time O(nk) ACA ACT GTA ACA 1 GTA 2 1 GTT MP score = 4 Finding the optimal MP tree is NP-hard

Problems with current techniques for MP Even the best of the current methods do not reach 0. 01% of “optimal” on large datasets in 24 hours. (“Optimal” means best score to date, using any method over any amount of time. ) Performance of TNT with time

Problems with current techniques for MP Even the best of the current methods do not reach 0. 01% of “optimal” on large datasets in 24 hours. (“Optimal” means best score to date, using any method over any amount of time. ) Performance of TNT with time

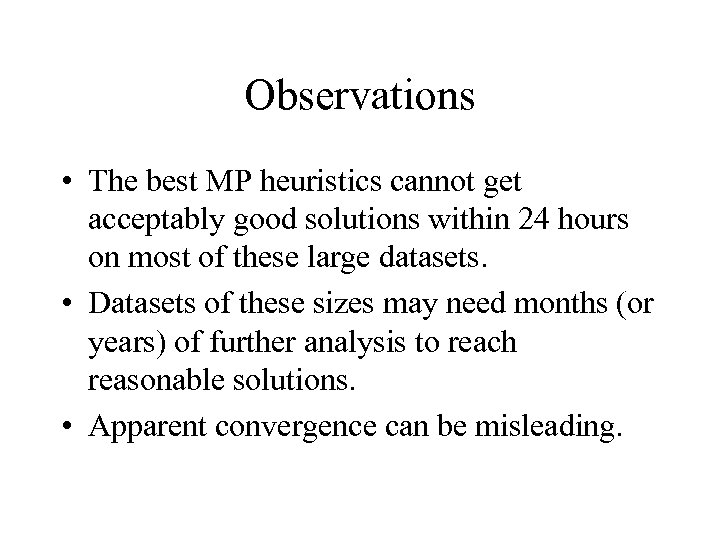

Observations • The best MP heuristics cannot get acceptably good solutions within 24 hours on most of these large datasets. • Datasets of these sizes may need months (or years) of further analysis to reach reasonable solutions. • Apparent convergence can be misleading.

Observations • The best MP heuristics cannot get acceptably good solutions within 24 hours on most of these large datasets. • Datasets of these sizes may need months (or years) of further analysis to reach reasonable solutions. • Apparent convergence can be misleading.

How can we improve upon existing techniques?

How can we improve upon existing techniques?

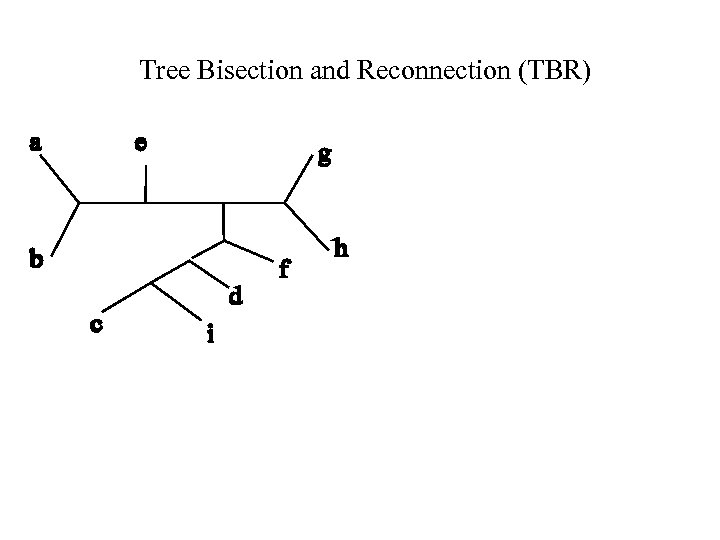

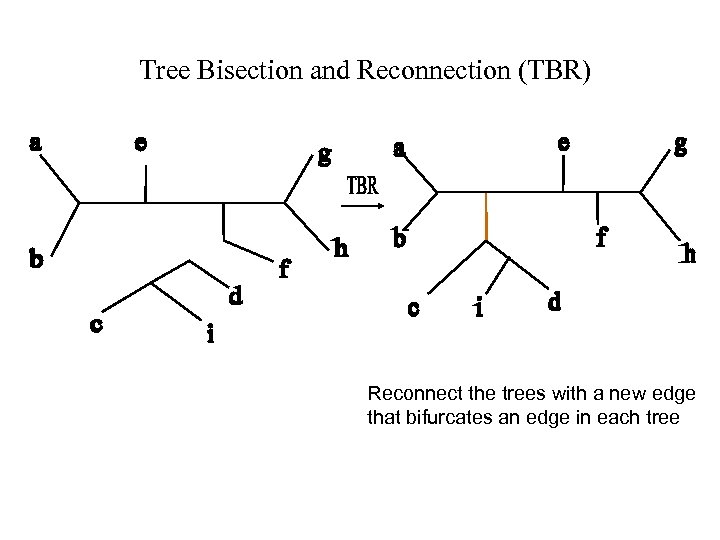

Tree Bisection and Reconnection (TBR)

Tree Bisection and Reconnection (TBR)

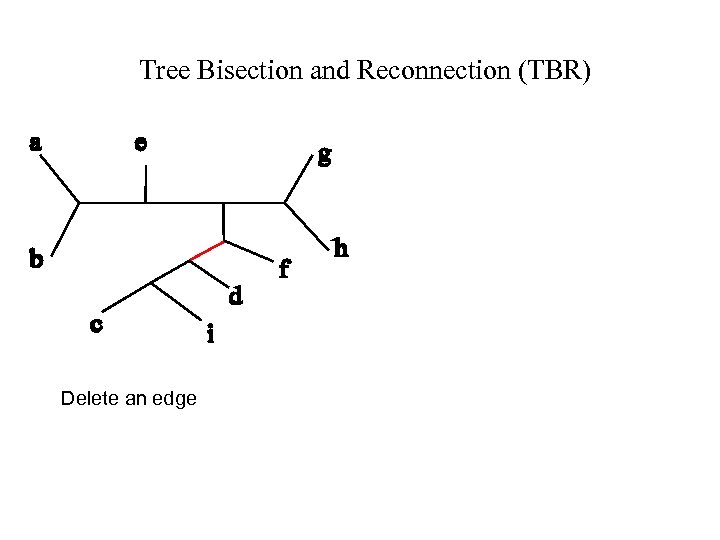

Tree Bisection and Reconnection (TBR) Delete an edge

Tree Bisection and Reconnection (TBR) Delete an edge

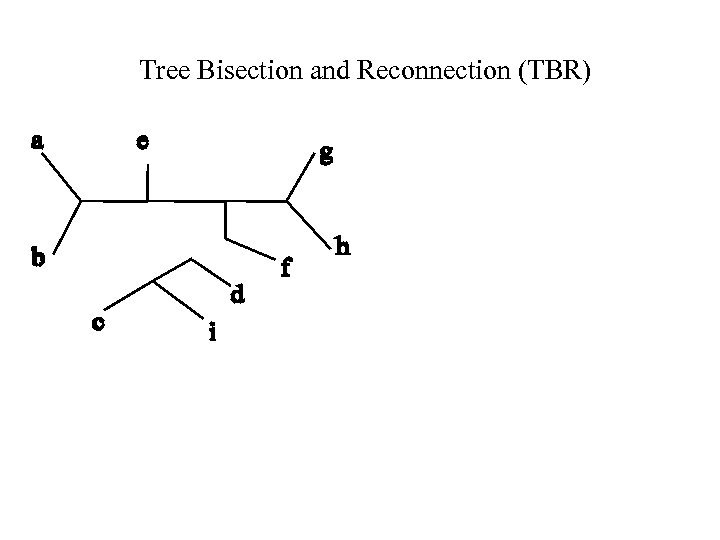

Tree Bisection and Reconnection (TBR)

Tree Bisection and Reconnection (TBR)

Tree Bisection and Reconnection (TBR) Reconnect the trees with a new edge that bifurcates an edge in each tree

Tree Bisection and Reconnection (TBR) Reconnect the trees with a new edge that bifurcates an edge in each tree

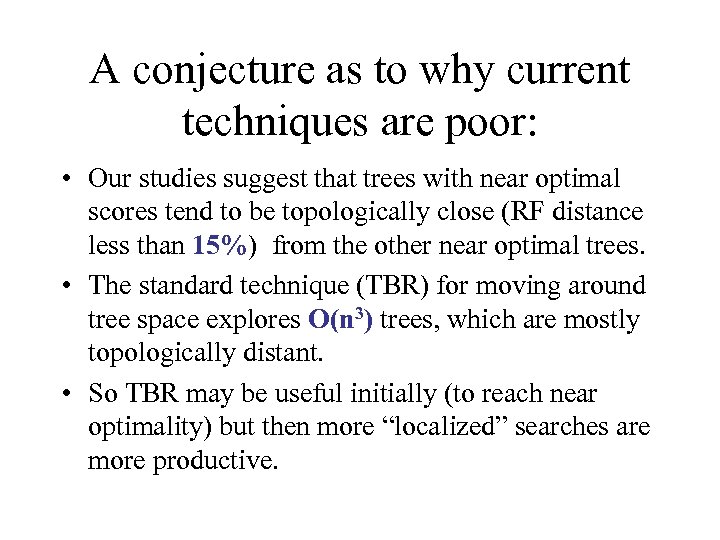

A conjecture as to why current techniques are poor: • Our studies suggest that trees with near optimal scores tend to be topologically close (RF distance less than 15%) from the other near optimal trees. • The standard technique (TBR) for moving around tree space explores O(n 3) trees, which are mostly topologically distant. • So TBR may be useful initially (to reach near optimality) but then more “localized” searches are more productive.

A conjecture as to why current techniques are poor: • Our studies suggest that trees with near optimal scores tend to be topologically close (RF distance less than 15%) from the other near optimal trees. • The standard technique (TBR) for moving around tree space explores O(n 3) trees, which are mostly topologically distant. • So TBR may be useful initially (to reach near optimality) but then more “localized” searches are more productive.

Using DCMs differently • Observation: DCMs make small local changes to the tree • New algorithmic strategy: use DCMs iteratively and/or recursively to improve heuristics on large datasets • However, the initial DCMs for MP – produced large subproblems and – took too long to compute • We needed a decomposition strategy that produces small subproblems quickly.

Using DCMs differently • Observation: DCMs make small local changes to the tree • New algorithmic strategy: use DCMs iteratively and/or recursively to improve heuristics on large datasets • However, the initial DCMs for MP – produced large subproblems and – took too long to compute • We needed a decomposition strategy that produces small subproblems quickly.

Using DCMs differently • Observation: DCMs make small local changes to the tree • New algorithmic strategy: use DCMs iteratively and/or recursively to improve heuristics on large datasets • However, the initial DCMs for MP – produced large subproblems and – took too long to compute • We needed a decomposition strategy that produces small subproblems quickly.

Using DCMs differently • Observation: DCMs make small local changes to the tree • New algorithmic strategy: use DCMs iteratively and/or recursively to improve heuristics on large datasets • However, the initial DCMs for MP – produced large subproblems and – took too long to compute • We needed a decomposition strategy that produces small subproblems quickly.

Using DCMs differently • Observation: DCMs make small local changes to the tree • New algorithmic strategy: use DCMs iteratively and/or recursively to improve heuristics on large datasets • However, the initial DCMs for MP – produced large subproblems and – took too long to compute • We needed a decomposition strategy that produces small subproblems quickly.

Using DCMs differently • Observation: DCMs make small local changes to the tree • New algorithmic strategy: use DCMs iteratively and/or recursively to improve heuristics on large datasets • However, the initial DCMs for MP – produced large subproblems and – took too long to compute • We needed a decomposition strategy that produces small subproblems quickly.

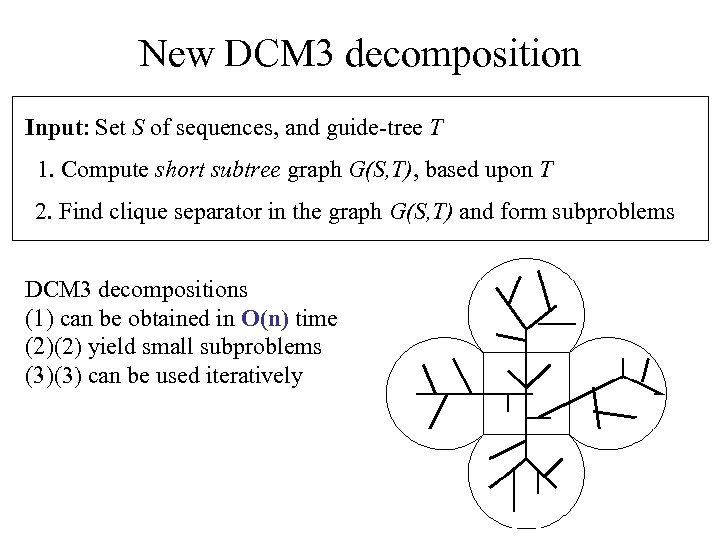

New DCM 3 decomposition Input: Set S of sequences, and guide-tree T 1. Compute short subtree graph G(S, T), based upon T 2. Find clique separator in the graph G(S, T) and form subproblems DCM 3 decompositions (1) can be obtained in O(n) time (2)(2) yield small subproblems (3)(3) can be used iteratively

New DCM 3 decomposition Input: Set S of sequences, and guide-tree T 1. Compute short subtree graph G(S, T), based upon T 2. Find clique separator in the graph G(S, T) and form subproblems DCM 3 decompositions (1) can be obtained in O(n) time (2)(2) yield small subproblems (3)(3) can be used iteratively

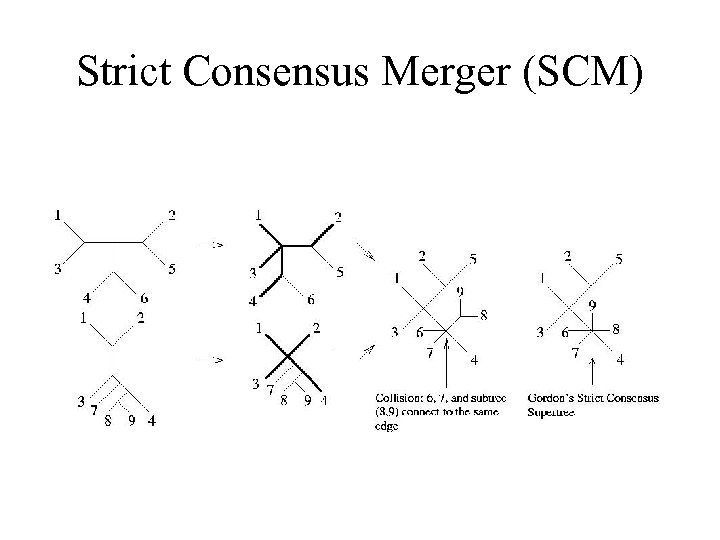

Strict Consensus Merger (SCM)

Strict Consensus Merger (SCM)

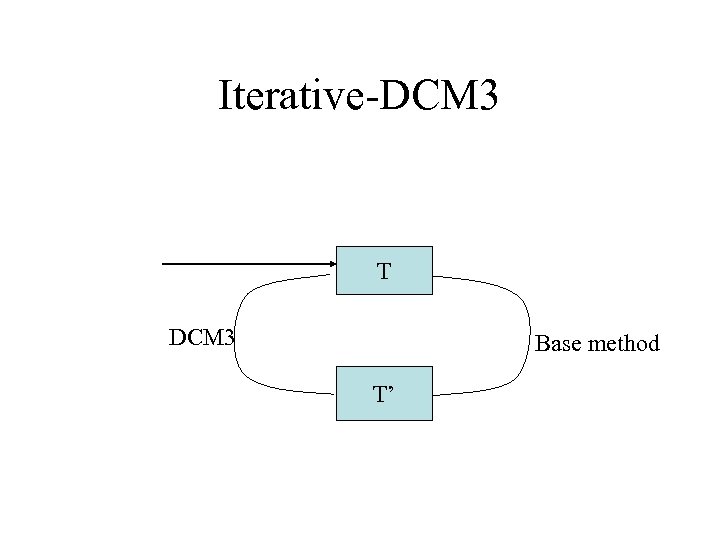

Iterative-DCM 3 T DCM 3 Base method T’

Iterative-DCM 3 T DCM 3 Base method T’

New DCMs • DCM 3 1. 2. 3. 4. • • Recursive-DCM 3 Iterative DCM 3 1. 2. • Compute subproblems using DCM 3 decomposition Apply base method to each subproblem to yield subtrees Merge subtrees using the Strict Consensus Merger technique Randomly refine to make it binary Compute a DCM 3 tree Perform local search and go to step 1 Recursive-Iterative DCM 3

New DCMs • DCM 3 1. 2. 3. 4. • • Recursive-DCM 3 Iterative DCM 3 1. 2. • Compute subproblems using DCM 3 decomposition Apply base method to each subproblem to yield subtrees Merge subtrees using the Strict Consensus Merger technique Randomly refine to make it binary Compute a DCM 3 tree Perform local search and go to step 1 Recursive-Iterative DCM 3

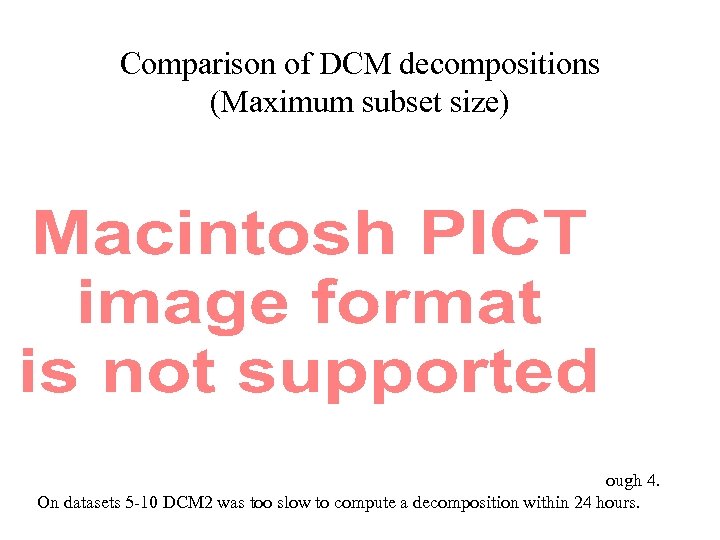

Comparison of DCM decompositions (Maximum subset size) DCM 2 subproblems are almost as large as the full dataset size on datasets 1 through 4. On datasets 5 -10 DCM 2 was too slow to compute a decomposition within 24 hours.

Comparison of DCM decompositions (Maximum subset size) DCM 2 subproblems are almost as large as the full dataset size on datasets 1 through 4. On datasets 5 -10 DCM 2 was too slow to compute a decomposition within 24 hours.

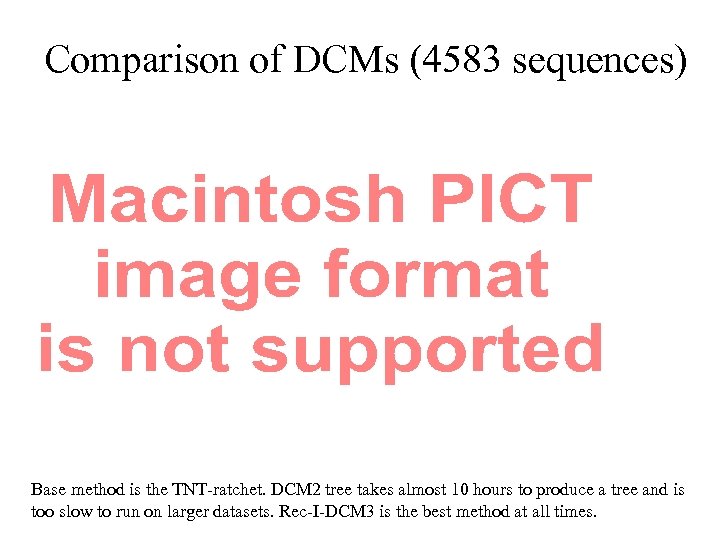

Comparison of DCMs (4583 sequences) Base method is the TNT-ratchet. DCM 2 tree takes almost 10 hours to produce a tree and is too slow to run on larger datasets. Rec-I-DCM 3 is the best method at all times.

Comparison of DCMs (4583 sequences) Base method is the TNT-ratchet. DCM 2 tree takes almost 10 hours to produce a tree and is too slow to run on larger datasets. Rec-I-DCM 3 is the best method at all times.

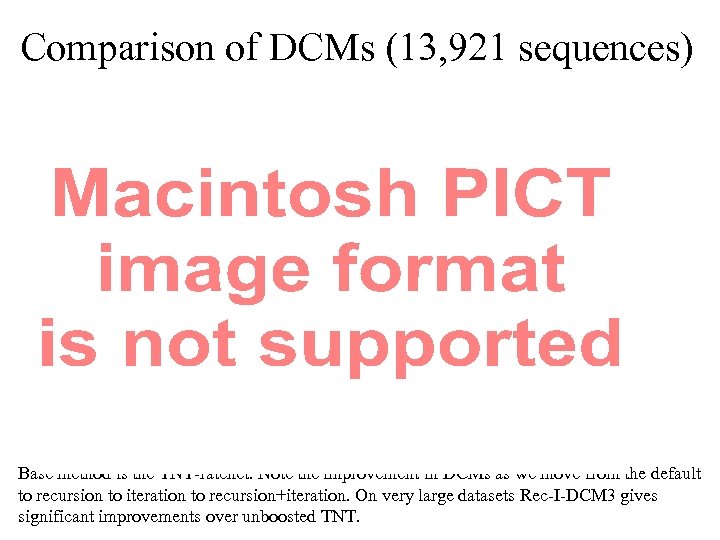

Comparison of DCMs (13, 921 sequences) Base method is the TNT-ratchet. Note the improvement in DCMs as we move from the default to recursion to iteration to recursion+iteration. On very large datasets Rec-I-DCM 3 gives significant improvements over unboosted TNT.

Comparison of DCMs (13, 921 sequences) Base method is the TNT-ratchet. Note the improvement in DCMs as we move from the default to recursion to iteration to recursion+iteration. On very large datasets Rec-I-DCM 3 gives significant improvements over unboosted TNT.

Rec-I-DCM 3 significantly improves performance Current best techniques DCM boosted version of best techniques Comparison of TNT to Rec-I-DCM 3(TNT) on one large dataset

Rec-I-DCM 3 significantly improves performance Current best techniques DCM boosted version of best techniques Comparison of TNT to Rec-I-DCM 3(TNT) on one large dataset

Rec-I-DCM 3(TNT) vs. TNT (Comparison of scores at 24 hours) The base method is the default TNT technique, the current best method for MP on large datasets. Rec-I-DCM 3 significantly improves upon the unboosted TNT.

Rec-I-DCM 3(TNT) vs. TNT (Comparison of scores at 24 hours) The base method is the default TNT technique, the current best method for MP on large datasets. Rec-I-DCM 3 significantly improves upon the unboosted TNT.

Observations • Rec-I-DCM 3 improves upon the best performing heuristics for MP. • The improvement increases with the difficulty of the dataset. • DCMs also boost the performance of ML heuristics (not shown).

Observations • Rec-I-DCM 3 improves upon the best performing heuristics for MP. • The improvement increases with the difficulty of the dataset. • DCMs also boost the performance of ML heuristics (not shown).

Questions • Tree shape (including branch lengths) has an impact on phylogeny reconstruction - but what model of tree shape to use? • What is the sequence length requirement for Maximum Likelihood? (Result by Szekely and Steel is worse than that for Neighbor Joining. ) • Why is MP not so bad?

Questions • Tree shape (including branch lengths) has an impact on phylogeny reconstruction - but what model of tree shape to use? • What is the sequence length requirement for Maximum Likelihood? (Result by Szekely and Steel is worse than that for Neighbor Joining. ) • Why is MP not so bad?

General comments • There is interesting computer science research to be done in computational phylogenetics, with a tremendous potential for impact. • Algorithm development must be tested on both real and simulated data. • The interplay between data, stochastic models of evolution, optimization problems, and algorithms, is important and instructive.

General comments • There is interesting computer science research to be done in computational phylogenetics, with a tremendous potential for impact. • Algorithm development must be tested on both real and simulated data. • The interplay between data, stochastic models of evolution, optimization problems, and algorithms, is important and instructive.

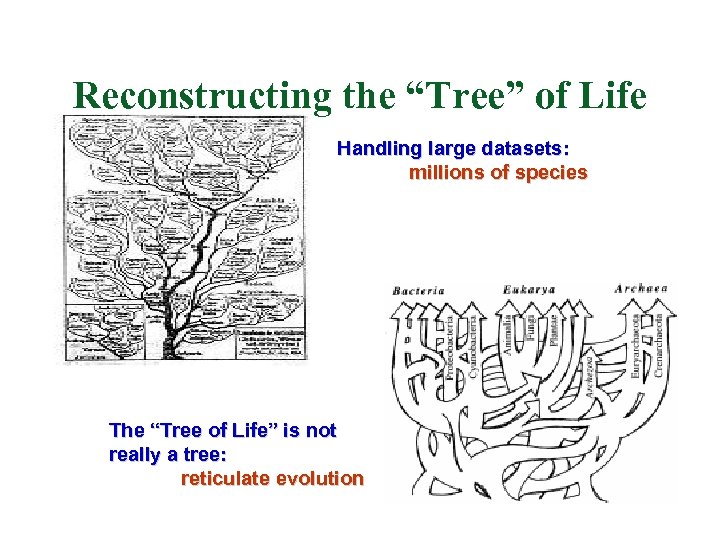

Reconstructing the “Tree” of Life Handling large datasets: millions of species The “Tree of Life” is not really a tree: reticulate evolution

Reconstructing the “Tree” of Life Handling large datasets: millions of species The “Tree of Life” is not really a tree: reticulate evolution

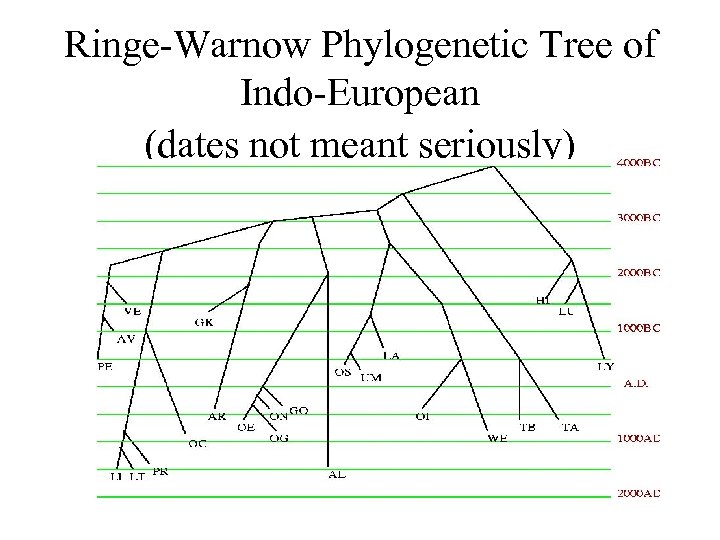

Ringe-Warnow Phylogenetic Tree of Indo-European (dates not meant seriously)

Ringe-Warnow Phylogenetic Tree of Indo-European (dates not meant seriously)

Websites for more information • Please see the CIPRES web site at http: //www. phylo. org for more about biological phylogenetics • The Computational Phylogenetics for Historical Linguistics project web site has papers, data, and additional material, as well as a workshop announcement for March 21, 2005 on Mathematical Modelling and Analysis of Language Diversification: http: //www. cs. rice. edu/~nakhleh/CPHL

Websites for more information • Please see the CIPRES web site at http: //www. phylo. org for more about biological phylogenetics • The Computational Phylogenetics for Historical Linguistics project web site has papers, data, and additional material, as well as a workshop announcement for March 21, 2005 on Mathematical Modelling and Analysis of Language Diversification: http: //www. cs. rice. edu/~nakhleh/CPHL

Acknowledgements • NSF • The David and Lucile Packard Foundation • The Radcliffe Institute for Advanced Study, and the Program in Evolutionary Dynamics at Harvard • The Institute for Cellular and Molecular Biology at UT-Austin • Collaborators: Usman Roshan, Bernard Moret, and Tiffani Williams

Acknowledgements • NSF • The David and Lucile Packard Foundation • The Radcliffe Institute for Advanced Study, and the Program in Evolutionary Dynamics at Harvard • The Institute for Cellular and Molecular Biology at UT-Austin • Collaborators: Usman Roshan, Bernard Moret, and Tiffani Williams