31b849674de10de71de40a48063efad3.ppt

- Количество слайдов: 64

Perl course The teacher: Peter Wad Sackett Center for Biological Sequence Analysis pws@cbs. dtu. dk Computer scientist. Programmed in Perl since 1995. Taught Perl since 2002.

Perl course The teacher: Peter Wad Sackett Center for Biological Sequence Analysis pws@cbs. dtu. dk Computer scientist. Programmed in Perl since 1995. Taught Perl since 2002.

Books The beginner book Learning Perl, 4 th ed. by Randal Schwartz & Tom Christiansen (O'Reilly) The bible Programming Perl, 3 rd ed. by Larry Wall, Tom Christiansen & Jon Orwant (O'Reilly) The rest are more or less successful spin-offs.

Books The beginner book Learning Perl, 4 th ed. by Randal Schwartz & Tom Christiansen (O'Reilly) The bible Programming Perl, 3 rd ed. by Larry Wall, Tom Christiansen & Jon Orwant (O'Reilly) The rest are more or less successful spin-offs.

Links Main Perl web site http: //www. perl. org/ Perl documentation http: //perldoc. perl. org/ Perl module/library repository http: //cpan. perl. org/ Online perl book http: //www. perl. org/books/beginning-perl/

Links Main Perl web site http: //www. perl. org/ Perl documentation http: //perldoc. perl. org/ Perl module/library repository http: //cpan. perl. org/ Online perl book http: //www. perl. org/books/beginning-perl/

Perl strengths and weaknesses PROS: Fairly standard C-like syntax Runs on Unix, Windows and Mac among others Powerful text parsing facilities Large library base Quick development Known as the ”glue” that connects applications CONS: Not as quick as compiled languages Possible (and easy) to make ugly and hard to maintain code

Perl strengths and weaknesses PROS: Fairly standard C-like syntax Runs on Unix, Windows and Mac among others Powerful text parsing facilities Large library base Quick development Known as the ”glue” that connects applications CONS: Not as quick as compiled languages Possible (and easy) to make ugly and hard to maintain code

Variables All variables (scalars) starts with $. A variable name may contain alphanumeric characters and underscore. Case matters. A simple variable can be either a string or floating point number, but does not need to be declared as any specific type. Perl has a number of predefined variables (sometimes used), consisting of $ and a single non-alphanumeric character. Examples: $var 1, $i, $My. Count, $remember_this.

Variables All variables (scalars) starts with $. A variable name may contain alphanumeric characters and underscore. Case matters. A simple variable can be either a string or floating point number, but does not need to be declared as any specific type. Perl has a number of predefined variables (sometimes used), consisting of $ and a single non-alphanumeric character. Examples: $var 1, $i, $My. Count, $remember_this.

Numbers and operators Numbers are assigned in a ”natural” manner; $num = 1; $num = 324. 657; $num = -0. 043; Standard numeric operators: + - * / ** % Bitwise operators: | (or) & (and) ^ (xor) ~ (not) >> (rightshift) << (leftshift) Autoincrement and autodecrement: ++ --

Numbers and operators Numbers are assigned in a ”natural” manner; $num = 1; $num = 324. 657; $num = -0. 043; Standard numeric operators: + - * / ** % Bitwise operators: | (or) & (and) ^ (xor) ~ (not) >> (rightshift) << (leftshift) Autoincrement and autodecrement: ++ --

Strings are assigned with quotes: $string = ’This is a literal string’; $string = ”This is an $interpolated stringn”; Interpolated strings are searched for variables and special character combinations that has meaning, like n for newline and t for tab. If a number is used in a string context then it is changed to a string and vice versa. String operators: . (concatenation) x (repetition)

Strings are assigned with quotes: $string = ’This is a literal string’; $string = ”This is an $interpolated stringn”; Interpolated strings are searched for variables and special character combinations that has meaning, like n for newline and t for tab. If a number is used in a string context then it is changed to a string and vice versa. String operators: . (concatenation) x (repetition)

Conditional statement A standard if statement if (predicate) { # this will be executed if the predicate is true } if statements exists in various forms in perl if (predicate) { # this will be executed if the predicate is true } elsif (predicate 2) { # no spelling mistake # this will be executed if this predicate is true } else { # finally this is excuted if no predicates where true } Can be turned around unless (predicate) { # this will be executed if the predicate is false }

Conditional statement A standard if statement if (predicate) { # this will be executed if the predicate is true } if statements exists in various forms in perl if (predicate) { # this will be executed if the predicate is true } elsif (predicate 2) { # no spelling mistake # this will be executed if this predicate is true } else { # finally this is excuted if no predicates where true } Can be turned around unless (predicate) { # this will be executed if the predicate is false }

Predicates are simple boolean expressions that can be stringed together via boolean operators forming complex logic. Numerical comparison operators: < > <= >= == != <=> String comparison operators: lt gt le ge eq ne cmp Boolean operators: && and || or ! not xor Examples: $age > 18 and $height < 1. 4 ($name eq ’Peter’ or $name eq ’Chris’) and $wage <= 25000 Perl is using short-circuit (lazy) evaluation.

Predicates are simple boolean expressions that can be stringed together via boolean operators forming complex logic. Numerical comparison operators: < > <= >= == != <=> String comparison operators: lt gt le ge eq ne cmp Boolean operators: && and || or ! not xor Examples: $age > 18 and $height < 1. 4 ($name eq ’Peter’ or $name eq ’Chris’) and $wage <= 25000 Perl is using short-circuit (lazy) evaluation.

Loops - while The standard while loop. # some initialization while (predicate) { # code which is executed while the predicate is true } There are various forms of the while loop: until (predicate) { # code which is executed while the predicate is false } do { # code } while (predicate);

Loops - while The standard while loop. # some initialization while (predicate) { # code which is executed while the predicate is true } There are various forms of the while loop: until (predicate) { # code which is executed while the predicate is false } do { # code } while (predicate);

Loops - for Perl has the standard for loop: for(init; predicate; increment) {} for($i = 0; $i < 10; $i++) { # code executed 10 times } A infinite loop is often written as for (; ; ) { # code executed forever }

Loops - for Perl has the standard for loop: for(init; predicate; increment) {} for($i = 0; $i < 10; $i++) { # code executed 10 times } A infinite loop is often written as for (; ; ) { # code executed forever }

Loops - control There are 3 loop control primitives that can be used in all forms of loops: last breaks (ends) the loop next starts the loop from the top and executes the predicate redo starts the loop from the top, do not execute the predicate

Loops - control There are 3 loop control primitives that can be used in all forms of loops: last breaks (ends) the loop next starts the loop from the top and executes the predicate redo starts the loop from the top, do not execute the predicate

Shorthand notation Often if statements and sometimes loops only has one line of code to be executed in the block. Perl has a shorthand notation for that. if ($age > 80) { print ”Oldn”; } Shorthand print ”Oldn” if $age > 80; $x = 0 unless $x > 0; print ”$in” for ($i = 1; $i <= 10, $++); As seen the structure of the statement is turned around.

Shorthand notation Often if statements and sometimes loops only has one line of code to be executed in the block. Perl has a shorthand notation for that. if ($age > 80) { print ”Oldn”; } Shorthand print ”Oldn” if $age > 80; $x = 0 unless $x > 0; print ”$in” for ($i = 1; $i <= 10, $++); As seen the structure of the statement is turned around.

Output – printing to screen The print statement prints a comma separated list of values. print ”Hello worldn”; print ’Result is ’, $num 1 + $num 2, ”n”; print ”My name is $namen”; For better output formatting use printf, which is similar to the C function. printf (”%02 d/%02 d %04 dn”, $day, $month, $year); printf (”Sum is %7. 2 fn”, $sum); The output of print(f) goes to the last selected filehandle unless otherwise specified. This is usually STDOUT, which is usually the screen.

Output – printing to screen The print statement prints a comma separated list of values. print ”Hello worldn”; print ’Result is ’, $num 1 + $num 2, ”n”; print ”My name is $namen”; For better output formatting use printf, which is similar to the C function. printf (”%02 d/%02 d %04 dn”, $day, $month, $year); printf (”Sum is %7. 2 fn”, $sum); The output of print(f) goes to the last selected filehandle unless otherwise specified. This is usually STDOUT, which is usually the screen.

Input – getting it from the keyboard The keyboard is usually STDIN unless redirection is in play. Lines are read from the keyboard like any lines are read from a filehandle. $line =

Input – getting it from the keyboard The keyboard is usually STDIN unless redirection is in play. Lines are read from the keyboard like any lines are read from a filehandle. $line =

A simple Perl program #!/usr/bin/perl –w print ”Hello user !n. What is your name: ”; $name =

A simple Perl program #!/usr/bin/perl –w print ”Hello user !n. What is your name: ”; $name =

Strict Perl is a rather loose and forgiving language. This can be improved somewhat by using strict. #!/usr/bin/perl –w use strict; This will enforce variable declaration and proper scoping, disallow symbolic references and most barewords. This is a good thing as some stupid errors are caught and the code is more portable and version independant. Variables are declared by the key word my and are private (local) to the block in which they are declared.

Strict Perl is a rather loose and forgiving language. This can be improved somewhat by using strict. #!/usr/bin/perl –w use strict; This will enforce variable declaration and proper scoping, disallow symbolic references and most barewords. This is a good thing as some stupid errors are caught and the code is more portable and version independant. Variables are declared by the key word my and are private (local) to the block in which they are declared.

Scope (lexical) A block can be considered as the statements between { and }. A variable declared with my is known only in the enclosing block. Only the ”most recent” declared variable is known in the block. my $age; # declaring $age in main program making it a global # here is unwritten code that gets age if ($age < 10) { for (my $i = 1; $i < $age; $i++) { # private $i print ”Year: $in”; } } elsif ($age > 80) { my $age = 40; # private $age only known in this block print ”You are only $age years old. n”; } print ”You are really $age years old. n”;

Scope (lexical) A block can be considered as the statements between { and }. A variable declared with my is known only in the enclosing block. Only the ”most recent” declared variable is known in the block. my $age; # declaring $age in main program making it a global # here is unwritten code that gets age if ($age < 10) { for (my $i = 1; $i < $age; $i++) { # private $i print ”Year: $in”; } } elsif ($age > 80) { my $age = 40; # private $age only known in this block print ”You are only $age years old. n”; } print ”You are really $age years old. n”;

Opening files The modern open is a three parameters function call. open(FILEHANDLE, $mode, $filename) The usual file modes are: < reading > writing >> appending +< reading and writing |- output is piped to program in $filename -| output from program in $filename is piped (read) to Perl open(IN, ’<’, ”myfile. txt”) or die ”Can’t read file $!n”; close IN;

Opening files The modern open is a three parameters function call. open(FILEHANDLE, $mode, $filename) The usual file modes are: < reading > writing >> appending +< reading and writing |- output is piped to program in $filename -| output from program in $filename is piped (read) to Perl open(IN, ’<’, ”myfile. txt”) or die ”Can’t read file $!n”; close IN;

Semi-useful program #!/usr/bin/perl –w # Summing numbers in a file use strict; print ”What file should I sum: ”; my $filename =

Semi-useful program #!/usr/bin/perl –w # Summing numbers in a file use strict; print ”What file should I sum: ”; my $filename =

File system functions exit $optional_error_code; die ”This sentence is printed on STDERR”; unlink $filename; rename $old_filename, $new_filename; chmod 0755, $filename; mkdir $directoryname, 0755; rmdir $directoryname; chdir $directoryname; opendir(DIR, $directoryname); readdir(DIR); closedir DIR; system(”$program $parameters”); my $output = `$program $parameters`;

File system functions exit $optional_error_code; die ”This sentence is printed on STDERR”; unlink $filename; rename $old_filename, $new_filename; chmod 0755, $filename; mkdir $directoryname, 0755; rmdir $directoryname; chdir $directoryname; opendir(DIR, $directoryname); readdir(DIR); closedir DIR; system(”$program $parameters”); my $output = `$program $parameters`;

File test operators There is a whole range of file test operators that all look like –X. print ”File exists” if –e $filename; Some of the more useful are: -e True if file exists -z True if file has zero size -s Returns file size -T True if text file -B True if binary file -r True if file is readable by effective uid/gid -d True if file is a directory -l True if file is a symbolic link

File test operators There is a whole range of file test operators that all look like –X. print ”File exists” if –e $filename; Some of the more useful are: -e True if file exists -z True if file has zero size -s Returns file size -T True if text file -B True if binary file -r True if file is readable by effective uid/gid -d True if file is a directory -l True if file is a symbolic link

String functions 1 Remove a trailing record separator from a string, usually newline my $no_of_chars_removed = chomp $line; Remove the last character from a string my $char_removed = chop $line; Return lower-case version of a string my $lstring = lc($string); Return a string with just the first letter in lower case my $lfstring = lcfirst($string); Return upper-case version of a string my $ustring = uc($string); Return a string with just the first letter in upper case my $ufstring = ucfirst($string); Get character this number represents my $char = chr($number); Find a character's numeric representation my $number = ord($char);

String functions 1 Remove a trailing record separator from a string, usually newline my $no_of_chars_removed = chomp $line; Remove the last character from a string my $char_removed = chop $line; Return lower-case version of a string my $lstring = lc($string); Return a string with just the first letter in lower case my $lfstring = lcfirst($string); Return upper-case version of a string my $ustring = uc($string); Return a string with just the first letter in upper case my $ufstring = ucfirst($string); Get character this number represents my $char = chr($number); Find a character's numeric representation my $number = ord($char);

String functions 2 Strings start with position 0 Return the number of charaters in a string my $len = length($string); Find a substring within a string my $pos = index($string, $substring, $optional_position); Right-to-left substring search my $pos = rindex($string, $substring, $optional_position); Flip/reverse a string my $rstring = reverse $string; Formatted print into a string (like printf) sprintf($format, $variables…); Get or alter a portion of a string my $substring = substr($string, $position); my $substring = substr($string, $position, $length); substr($string, $position, $length, $replacementstring);

String functions 2 Strings start with position 0 Return the number of charaters in a string my $len = length($string); Find a substring within a string my $pos = index($string, $substring, $optional_position); Right-to-left substring search my $pos = rindex($string, $substring, $optional_position); Flip/reverse a string my $rstring = reverse $string; Formatted print into a string (like printf) sprintf($format, $variables…); Get or alter a portion of a string my $substring = substr($string, $position); my $substring = substr($string, $position, $length); substr($string, $position, $length, $replacementstring);

Stateful parsing is a robust and simple method to read data that are split up on several lines in a file. It works by recognizing the line (or line before) where data starts (green line) and the line (or line after) it ends (red line). The green and/or red line can contain part of the data. The principle is shown here, but code can be easily added to handle specific situations. my $flag = 0; my $data = ’’; while (defined (my $line =

Stateful parsing is a robust and simple method to read data that are split up on several lines in a file. It works by recognizing the line (or line before) where data starts (green line) and the line (or line after) it ends (red line). The green and/or red line can contain part of the data. The principle is shown here, but code can be easily added to handle specific situations. my $flag = 0; my $data = ’’; while (defined (my $line =

Arrays are denoted with @. They are initalized as a comma separeted list of values (scalars). They can contain any mix of numbers, strings or references. The first element is at position 0, i. e. arrays are zero-based. There is no need to declare the size of the array except for performance reasons for large arrays. It grows and shrinks as needed. my @array; my @array = (1, ’two, 3, ’four is 4’); Individual elements are accessed as variables, i. e. with $ print $array[0], $array[1]; Length of an array. scalar(@array) == $#array + 1

Arrays are denoted with @. They are initalized as a comma separeted list of values (scalars). They can contain any mix of numbers, strings or references. The first element is at position 0, i. e. arrays are zero-based. There is no need to declare the size of the array except for performance reasons for large arrays. It grows and shrinks as needed. my @array; my @array = (1, ’two, 3, ’four is 4’); Individual elements are accessed as variables, i. e. with $ print $array[0], $array[1]; Length of an array. scalar(@array) == $#array + 1

Array slices You can access a slice of an array. my @slice = @array[5. . 8]; my @slice = @array[$position. . $#array]; my ($var 1, $var 2) = @array[4, $pos]; Or assign to a slice. @array[4. . 7] = (1, 2, 3, 4); @array[$pos, 5] = @tmp[2. . 3]; Printing arrays print @array, ”@array”;

Array slices You can access a slice of an array. my @slice = @array[5. . 8]; my @slice = @array[$position. . $#array]; my ($var 1, $var 2) = @array[4, $pos]; Or assign to a slice. @array[4. . 7] = (1, 2, 3, 4); @array[$pos, 5] = @tmp[2. . 3]; Printing arrays print @array, ”@array”;

Iterating over arrays A straightforward for-loop. for (my $i = 0; $i <= $#array; $i++) { print $array[$i]*2, ”n”; } The special foreach-loop designed for arrays. foreach my $element (@array) { print $element*2, ”n”; } If you change the $element inside the foreach loop the actual value in the array is changed.

Iterating over arrays A straightforward for-loop. for (my $i = 0; $i <= $#array; $i++) { print $array[$i]*2, ”n”; } The special foreach-loop designed for arrays. foreach my $element (@array) { print $element*2, ”n”; } If you change the $element inside the foreach loop the actual value in the array is changed.

Array functions 1 Inserting an element in the beginning of an array unshift(@array, $value); Removing an element from the beginning of an array my $value = shift(@array); Adding an element to the end of an array push(@array, $value); Removing an element from the end of an array my $value = pop(@array); Adding and/or removing element at any place in an array my @goners = splice(@array, $position); my @goners = splice(@array, $position, $length, $value); my @goners = splice(@array, $position, $length, @tmp);

Array functions 1 Inserting an element in the beginning of an array unshift(@array, $value); Removing an element from the beginning of an array my $value = shift(@array); Adding an element to the end of an array push(@array, $value); Removing an element from the end of an array my $value = pop(@array); Adding and/or removing element at any place in an array my @goners = splice(@array, $position); my @goners = splice(@array, $position, $length, $value); my @goners = splice(@array, $position, $length, @tmp);

Array functions 2 Sorting an array. @array = sort @array; # alphabetical sort @array = sort {$a <=> $b} @array; # numerical sort Reversing an array. @array = reverse @array; Splitting a string into an array. my @array = split(m/regex/, $string, $optional_number); my @array = split(’ ’, $string); Joining an array into a string my $string = join(”n”, @array); Find elements in a list test true against a given criterion @newarray = grep(m/regex/, @array);

Array functions 2 Sorting an array. @array = sort @array; # alphabetical sort @array = sort {$a <=> $b} @array; # numerical sort Reversing an array. @array = reverse @array; Splitting a string into an array. my @array = split(m/regex/, $string, $optional_number); my @array = split(’ ’, $string); Joining an array into a string my $string = join(”n”, @array); Find elements in a list test true against a given criterion @newarray = grep(m/regex/, @array);

Predefined arrays Perl has a few predefined arrays. @INC, which is a list of include directories used for location modules. @ARGV, which is the argument vector. Any parameters given to the program on command line ends up here. . /perl_program 1 file. txt @ARGV contains (1, ’file. txt’) at program start. Very useful for serious programs.

Predefined arrays Perl has a few predefined arrays. @INC, which is a list of include directories used for location modules. @ARGV, which is the argument vector. Any parameters given to the program on command line ends up here. . /perl_program 1 file. txt @ARGV contains (1, ’file. txt’) at program start. Very useful for serious programs.

Regular expressions – classes Regular expressions return a true/false value and the match is available. print ”match” if $string =~ m/regex/; print ”match” if not $string !~ m/regex/; Character classes with [ ] m/A[BCD]A/ m/A[a-g]A/ m/A[12 a-z]A/ m/A[^a-zd]A/ Standard classes s whitespace, i. e. [ tnrf] S non-whitespace w ”word” char, i. e. [A-Za-z 0 -9_] W non-word d digit, i. e. [0 -9] D non-digit . any character except newline n newline {char} escape for special characters like \, [ etc.

Regular expressions – classes Regular expressions return a true/false value and the match is available. print ”match” if $string =~ m/regex/; print ”match” if not $string !~ m/regex/; Character classes with [ ] m/A[BCD]A/ m/A[a-g]A/ m/A[12 a-z]A/ m/A[^a-zd]A/ Standard classes s whitespace, i. e. [ tnrf] S non-whitespace w ”word” char, i. e. [A-Za-z 0 -9_] W non-word d digit, i. e. [0 -9] D non-digit . any character except newline n newline {char} escape for special characters like \, [ etc.

Regular expressions – quantifiers Often a match contains repeated parts, like an unknown number of digits. This is done with a quantifier that follows the character. ? 0 or 1 occurence + 1 or more occurences * 0 or more occurences {n} excatly n occurences {n, } at least n occurences {n, m} between n and m occurences m/A+B? / m/[A-Z]{1, 2}d{4, }/ Matches are greedy, i. e. will match as much as possible. This can be changed by adding ? to the quantifier making the match non-greedy. m/A+? /

Regular expressions – quantifiers Often a match contains repeated parts, like an unknown number of digits. This is done with a quantifier that follows the character. ? 0 or 1 occurence + 1 or more occurences * 0 or more occurences {n} excatly n occurences {n, } at least n occurences {n, m} between n and m occurences m/A+B? / m/[A-Z]{1, 2}d{4, }/ Matches are greedy, i. e. will match as much as possible. This can be changed by adding ? to the quantifier making the match non-greedy. m/A+? /

Regular expressions – groups Often a pattern consists of repeated groups of characters. A group is created by parenthesis. This is also the way to extract data from a match. m/(AB)+/ m/([A-Z]{1, 2}d{4, })/ The match of the first group will be available in $1, second group in $2. . . If a data line looks like e. g. first line in a swissprot entry ID ASM_HUMAN STANDARD; PRT; $id = $1 if $line =~ m/IDs+(w+)/; Alternation with | is a way to match either this or that. $name = $1 if $string =~ m/(Peter|Chris)/; 629 AA.

Regular expressions – groups Often a pattern consists of repeated groups of characters. A group is created by parenthesis. This is also the way to extract data from a match. m/(AB)+/ m/([A-Z]{1, 2}d{4, })/ The match of the first group will be available in $1, second group in $2. . . If a data line looks like e. g. first line in a swissprot entry ID ASM_HUMAN STANDARD; PRT; $id = $1 if $line =~ m/IDs+(w+)/; Alternation with | is a way to match either this or that. $name = $1 if $string =~ m/(Peter|Chris)/; 629 AA.

Regular expressions – bindings A very useful and performance efficient trick is to bind the match to the beginning and/or end of the line. m/^IDs(w+)/ caret at first position binds to the beginning of the line m/pattern$/ dollersign at last position binds to the end of the line Always define patterns to be as narrow as possible as that makes them stronger and more exact. Regular expressions are best created by matching the pattern you look for, not by matching what the pattern is not. Variables can be used in a pattern.

Regular expressions – bindings A very useful and performance efficient trick is to bind the match to the beginning and/or end of the line. m/^IDs(w+)/ caret at first position binds to the beginning of the line m/pattern$/ dollersign at last position binds to the end of the line Always define patterns to be as narrow as possible as that makes them stronger and more exact. Regular expressions are best created by matching the pattern you look for, not by matching what the pattern is not. Variables can be used in a pattern.

Regular expressions – modifiers The function of a RE can be modified by adding a letter after the final /. The most useful modifiers are: i case-insensitive g global – all occurences o compile once, improve performance when not using variables m multiline - ^ and $ match internal lines m/peter/io finds Peter and PETER in a line - fast. A wonderful trick to find all numbers in a line is my @array = $line =~ m/d+/g; my @array = $line =~ m/=(d+)/go; print ”Good number” if $line =~ m/^-? d+(. d+)? $/o;

Regular expressions – modifiers The function of a RE can be modified by adding a letter after the final /. The most useful modifiers are: i case-insensitive g global – all occurences o compile once, improve performance when not using variables m multiline - ^ and $ match internal lines m/peter/io finds Peter and PETER in a line - fast. A wonderful trick to find all numbers in a line is my @array = $line =~ m/d+/g; my @array = $line =~ m/=(d+)/go; print ”Good number” if $line =~ m/^-? d+(. d+)? $/o;

Regular expressions - substitution Regular expressions can also be used to replace text in a string. This is substitution and is quite similar to matching. The newtext is quite literal, however $1, $2 etc works here. $string =~ s/regex/newtext/; $string =~ s/(d+) kr/$1 dollar/; # replacing kroner with dollar There is a useful extra modifier e which allows perl code to be executed as the replacement text in substitution. $string =~ s/(d+) kr/’X’ x length($1). ’ dollar’/e; # replacing kroner with dollar, but replacing the amount with x’es.

Regular expressions - substitution Regular expressions can also be used to replace text in a string. This is substitution and is quite similar to matching. The newtext is quite literal, however $1, $2 etc works here. $string =~ s/regex/newtext/; $string =~ s/(d+) kr/$1 dollar/; # replacing kroner with dollar There is a useful extra modifier e which allows perl code to be executed as the replacement text in substitution. $string =~ s/(d+) kr/’X’ x length($1). ’ dollar’/e; # replacing kroner with dollar, but replacing the amount with x’es.

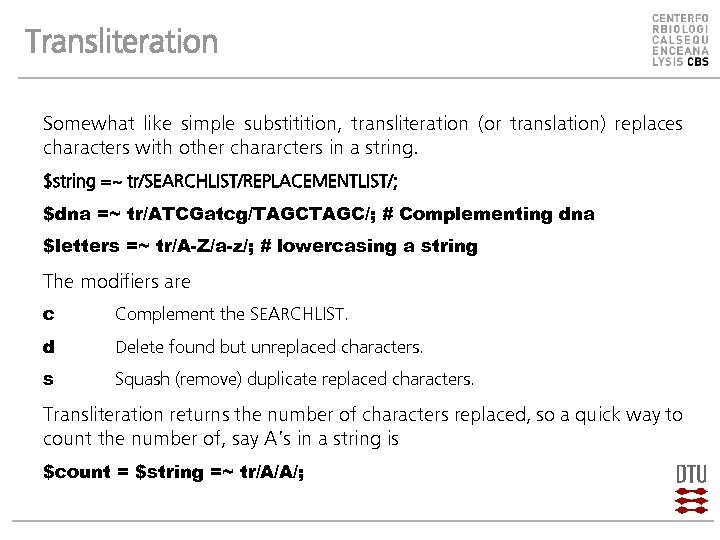

Transliteration Somewhat like simple substitition, transliteration (or translation) replaces characters with other chararcters in a string. $string =~ tr/SEARCHLIST/REPLACEMENTLIST/; $dna =~ tr/ATCGatcg/TAGC/; # Complementing dna $letters =~ tr/A-Z/a-z/; # lowercasing a string The modifiers are c Complement the SEARCHLIST. d Delete found but unreplaced characters. s Squash (remove) duplicate replaced characters. Transliteration returns the number of characters replaced, so a quick way to count the number of, say A’s in a string is $count = $string =~ tr/A/A/;

Transliteration Somewhat like simple substitition, transliteration (or translation) replaces characters with other chararcters in a string. $string =~ tr/SEARCHLIST/REPLACEMENTLIST/; $dna =~ tr/ATCGatcg/TAGC/; # Complementing dna $letters =~ tr/A-Z/a-z/; # lowercasing a string The modifiers are c Complement the SEARCHLIST. d Delete found but unreplaced characters. s Squash (remove) duplicate replaced characters. Transliteration returns the number of characters replaced, so a quick way to count the number of, say A’s in a string is $count = $string =~ tr/A/A/;

Hashes are unordered lists and are very fexible data structures. Arrays can be considered as a special case of hashes. % is used for a hash. Data is a hash is a number of key/value pairs. One of the more obvious uses af a hash is as a translation table. my %hash = (1 => ’one’, ’one’ => 1, 2 => ’two’, ’two’ => 2); print $hash{1}, ”n” if $hash{’two’} == $number; $hash{3} = ’three’; It should be obvious from the key/value pair structure, that a key is unique in the hash, where a value can be repeated any number of times. Hash slices are possible on the values. Notice the @. my @slice = @hash{’one’, ’two’};

Hashes are unordered lists and are very fexible data structures. Arrays can be considered as a special case of hashes. % is used for a hash. Data is a hash is a number of key/value pairs. One of the more obvious uses af a hash is as a translation table. my %hash = (1 => ’one’, ’one’ => 1, 2 => ’two’, ’two’ => 2); print $hash{1}, ”n” if $hash{’two’} == $number; $hash{3} = ’three’; It should be obvious from the key/value pair structure, that a key is unique in the hash, where a value can be repeated any number of times. Hash slices are possible on the values. Notice the @. my @slice = @hash{’one’, ’two’};

Hash functions delete $hash{$key}; # Deletes a key/value pair exists $hash{$key} # Returns true if the key/value pair exists keys %hash # Returns an array with all the keys of the hash values %hash # Returns an array with the values of the hash each %hash # Used in iteration over the hash The usual ways to iterate over a hash are foreach my $key (keys %hash) { print ”$key => $hash{$key}n”; } while (my ($key, $value) = each %hash) { print ”$key => $valuen”; }

Hash functions delete $hash{$key}; # Deletes a key/value pair exists $hash{$key} # Returns true if the key/value pair exists keys %hash # Returns an array with all the keys of the hash values %hash # Returns an array with the values of the hash each %hash # Used in iteration over the hash The usual ways to iterate over a hash are foreach my $key (keys %hash) { print ”$key => $hash{$key}n”; } while (my ($key, $value) = each %hash) { print ”$key => $valuen”; }

Semi-advanced hash usage Sparse N-dimensional matrix You need a large sparsely populated N-dimensional matrix. A very good and easy way is to use a hash, even if a hash is a "flat" data structure. The secret is in constructing an appropriate key. An example could be a three dimensional matrix which could be populated in this way: $matrix{"$x, $y, $z"} = $value; Access the matrix like this: $value = exists $matrix{"$x, $y, $z"} ? $matrix{"$x, $y, $z"} : 0; Notice that $x, $y, $z is not limited to numbers, they could be Swiss. Prot IDs or other data that makes sense. The matrix does not have to be regular.

Semi-advanced hash usage Sparse N-dimensional matrix You need a large sparsely populated N-dimensional matrix. A very good and easy way is to use a hash, even if a hash is a "flat" data structure. The secret is in constructing an appropriate key. An example could be a three dimensional matrix which could be populated in this way: $matrix{"$x, $y, $z"} = $value; Access the matrix like this: $value = exists $matrix{"$x, $y, $z"} ? $matrix{"$x, $y, $z"} : 0; Notice that $x, $y, $z is not limited to numbers, they could be Swiss. Prot IDs or other data that makes sense. The matrix does not have to be regular.

Subroutines 1 Subroutines serve two functions; Code reusage and hiding program complexity. All parameters to a subroutine are passed in a single list @_ no matter if they are scalars, arrays or hashes. Likewise a subroutine returns a single flat list of values. All the parameters in @_ are aliases to the real variable in the calling environment, meaning if you change $_[0] etc. , it is changed in the main program. sub mysub { my ($parm 1, $parm 2) = @_; # call-by-value return $parm 1 + $parm 2; } sub mysub 2 { return $_[0] + $_[1]; } # call-by-reference

Subroutines 1 Subroutines serve two functions; Code reusage and hiding program complexity. All parameters to a subroutine are passed in a single list @_ no matter if they are scalars, arrays or hashes. Likewise a subroutine returns a single flat list of values. All the parameters in @_ are aliases to the real variable in the calling environment, meaning if you change $_[0] etc. , it is changed in the main program. sub mysub { my ($parm 1, $parm 2) = @_; # call-by-value return $parm 1 + $parm 2; } sub mysub 2 { return $_[0] + $_[1]; } # call-by-reference

Subroutines 2 There can be any number of return statements in a subroutine. You can return any number of scalars, arrays and/or hashes but they will just be flattened into a list. This means that for practical purposes, you can return any number of scalars, but just one array or one hash. The same argument is valid for parameters passed to the subroutine. The way around this problem is to use references. sub passarray { my ($parm 1, $parm 2, @array) = @_; sub passhash { my ($parm 1, %hash) = @_; Subroutine calls are usually denoted with & my ($res 1, $res 2) = &calc 1($parm 1, $parm 2); my %hash = &calc(1, @parmarray);

Subroutines 2 There can be any number of return statements in a subroutine. You can return any number of scalars, arrays and/or hashes but they will just be flattened into a list. This means that for practical purposes, you can return any number of scalars, but just one array or one hash. The same argument is valid for parameters passed to the subroutine. The way around this problem is to use references. sub passarray { my ($parm 1, $parm 2, @array) = @_; sub passhash { my ($parm 1, %hash) = @_; Subroutine calls are usually denoted with & my ($res 1, $res 2) = &calc 1($parm 1, $parm 2); my %hash = &calc(1, @parmarray);

References A reference is much like a pointer in other languages. You create references with the backslash operator. Examples: $variablereference = $variable; $arrayreference = @array; $hashreference = %hash; $codereference = &subroutine; $filereference = *STDOUT;

References A reference is much like a pointer in other languages. You create references with the backslash operator. Examples: $variablereference = $variable; $arrayreference = @array; $hashreference = %hash; $codereference = &subroutine; $filereference = *STDOUT;

Dereferencing references You use/dereference the data that your reference points to in this way. print $$variablereference; $$arrayreference[0] = 1; print $$arrayreference[0]; @tab = @$arrayreference; $$hashreference{'alpha'} = 1; %hash = %$hashreference; &$codereference('parameter'); print $filereference $data; $data = <$filereference>; It is recommended to use the infix operator -> on arrays, hashes and subroutines. The examples below are just different syntactical ways to express the same thing. $$hashref{$key} = 'blabla'; ${$hashref}{$key} = 'blabla'; $hashref->{$key} = 'blabla';

Dereferencing references You use/dereference the data that your reference points to in this way. print $$variablereference; $$arrayreference[0] = 1; print $$arrayreference[0]; @tab = @$arrayreference; $$hashreference{'alpha'} = 1; %hash = %$hashreference; &$codereference('parameter'); print $filereference $data; $data = <$filereference>; It is recommended to use the infix operator -> on arrays, hashes and subroutines. The examples below are just different syntactical ways to express the same thing. $$hashref{$key} = 'blabla'; ${$hashref}{$key} = 'blabla'; $hashref->{$key} = 'blabla';

Is it a reference? To check if a variable really is a reference use the ref function to test it. if (ref $hashreference) { print "This is a referencen"; } else { print "This is a normal variablen"; } If the variable tested is really a reference, then the type of reference is returned by ref. if (ref $reference eq 'SCALAR') { print "This is a reference to a scalar (variable)n"; } elsif (ref $reference eq 'ARRAY') { print "This is a reference to an arrayn"; } elsif (ref $reference eq 'HASH') { print "This is a reference to a hashn"; } elsif (ref $reference eq 'CODE') { print "This is a reference to a subroutinen"; } elsif (ref $reference eq 'REF') { print "This is a reference to another referencen"; } There a few other possibilities, but they are seldom used.

Is it a reference? To check if a variable really is a reference use the ref function to test it. if (ref $hashreference) { print "This is a referencen"; } else { print "This is a normal variablen"; } If the variable tested is really a reference, then the type of reference is returned by ref. if (ref $reference eq 'SCALAR') { print "This is a reference to a scalar (variable)n"; } elsif (ref $reference eq 'ARRAY') { print "This is a reference to an arrayn"; } elsif (ref $reference eq 'HASH') { print "This is a reference to a hashn"; } elsif (ref $reference eq 'CODE') { print "This is a reference to a subroutinen"; } elsif (ref $reference eq 'REF') { print "This is a reference to another referencen"; } There a few other possibilities, but they are seldom used.

Subroutines revisited By passing just the reference to arrays/hashes it is possible to have any number of lists as parameters to subroutines just as it is possible to return references to any number of lists. sub refarraypass { my ($arrayref 1, $arrayref 2, $hashref) = @_; print $hashref->{’key’} if $$arrayref 1[1] eq ${$arrayref 2}[2]; } # Main program &refarraypass(@monsterarray, @bigarray, %tinyhash); Passing lists as references is efficient, both with respect to performance and memory.

Subroutines revisited By passing just the reference to arrays/hashes it is possible to have any number of lists as parameters to subroutines just as it is possible to return references to any number of lists. sub refarraypass { my ($arrayref 1, $arrayref 2, $hashref) = @_; print $hashref->{’key’} if $$arrayref 1[1] eq ${$arrayref 2}[2]; } # Main program &refarraypass(@monsterarray, @bigarray, %tinyhash); Passing lists as references is efficient, both with respect to performance and memory.

Arrays of arrays 1 N-dimensional matrix with arrays of arrays…. my @Ao. A = ([1, 2, 3], ['John', 'Joe, 'Ib'], ['Eat', 2]); print $Ao. A[1][2]; # Simple assignment # prints Ib # Suppose you want to read a matrix in from a file while (defined (my $line =

Arrays of arrays 1 N-dimensional matrix with arrays of arrays…. my @Ao. A = ([1, 2, 3], ['John', 'Joe, 'Ib'], ['Eat', 2]); print $Ao. A[1][2]; # Simple assignment # prints Ib # Suppose you want to read a matrix in from a file while (defined (my $line =

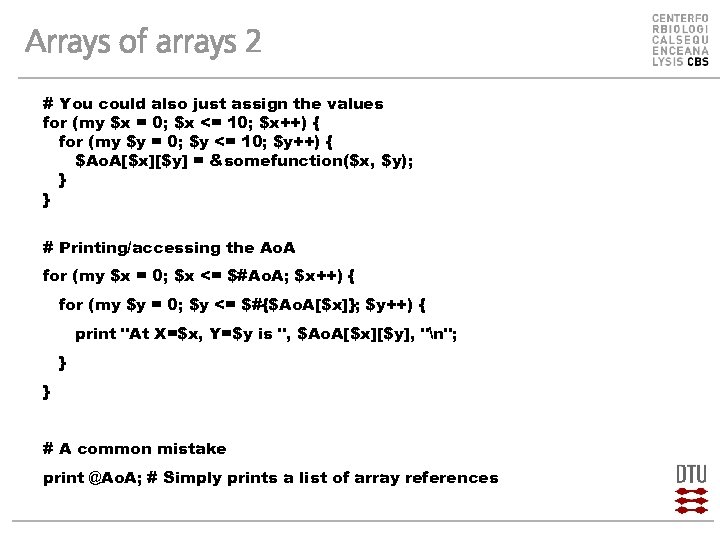

Arrays of arrays 2 # You could also just assign the values for (my $x = 0; $x <= 10; $x++) { for (my $y = 0; $y <= 10; $y++) { $Ao. A[$x][$y] = &somefunction($x, $y); } } # Printing/accessing the Ao. A for (my $x = 0; $x <= $#Ao. A; $x++) { for (my $y = 0; $y <= $#{$Ao. A[$x]}; $y++) { print "At X=$x, Y=$y is ", $Ao. A[$x][$y], "n"; } } # A common mistake print @Ao. A; # Simply prints a list of array references

Arrays of arrays 2 # You could also just assign the values for (my $x = 0; $x <= 10; $x++) { for (my $y = 0; $y <= 10; $y++) { $Ao. A[$x][$y] = &somefunction($x, $y); } } # Printing/accessing the Ao. A for (my $x = 0; $x <= $#Ao. A; $x++) { for (my $y = 0; $y <= $#{$Ao. A[$x]}; $y++) { print "At X=$x, Y=$y is ", $Ao. A[$x][$y], "n"; } } # A common mistake print @Ao. A; # Simply prints a list of array references

Hashes of hashes 1 This is a very flexible (and unordered) data structure. # Simple assignment %Ho. H = ('Masterkey 1' => {'Key 1' => 'Value 1', 'Key 2' => 'Value 2' }, 'Masterkey 2' => {'Key 1' => 'Value 1', 'Key. X' => 'Value. Y' } ); # Adding an anonymous hash to the hash $Ho. H{'New. Master. Key'} = {'New. Key 1' => 'New. Value 1', ‘Key 2' => 'Value 2'}; # Or if you have a hash you want to add $Ho. H{'New. Master. Key'} = { %My. Old. Hash }; # Adding a key/value pair in the "second" level. $Ho. H{'Master. Key 1'}{'New. Key'} = 'New. Value';

Hashes of hashes 1 This is a very flexible (and unordered) data structure. # Simple assignment %Ho. H = ('Masterkey 1' => {'Key 1' => 'Value 1', 'Key 2' => 'Value 2' }, 'Masterkey 2' => {'Key 1' => 'Value 1', 'Key. X' => 'Value. Y' } ); # Adding an anonymous hash to the hash $Ho. H{'New. Master. Key'} = {'New. Key 1' => 'New. Value 1', ‘Key 2' => 'Value 2'}; # Or if you have a hash you want to add $Ho. H{'New. Master. Key'} = { %My. Old. Hash }; # Adding a key/value pair in the "second" level. $Ho. H{'Master. Key 1'}{'New. Key'} = 'New. Value';

Hashes of hashes 2 # Printing/using a single value print $Ho. H{'Master. Key 1'}{'Key 1'}; # Accessing the structure foreach my $masterkey (keys %Ho. H) { print "First level: $masterkeyn"; foreach my $key (keys %{$Ho. H{$masterkey}}) { print "$key => $Ho. H{$masterkey}{$key}n"; } } Beware of the autovivification trap print ”ups, trapped” unless exists $Ho. H{$mkey}{$somekey}; print ”right” if exists $Ho. H{$mkey} and exists $Ho. H{$mkey}{$somekey};

Hashes of hashes 2 # Printing/using a single value print $Ho. H{'Master. Key 1'}{'Key 1'}; # Accessing the structure foreach my $masterkey (keys %Ho. H) { print "First level: $masterkeyn"; foreach my $key (keys %{$Ho. H{$masterkey}}) { print "$key => $Ho. H{$masterkey}{$key}n"; } } Beware of the autovivification trap print ”ups, trapped” unless exists $Ho. H{$mkey}{$somekey}; print ”right” if exists $Ho. H{$mkey} and exists $Ho. H{$mkey}{$somekey};

![Hashes of arrays # Simple assignment %Ho. A = ('Numbers' => [1, 2, 3], Hashes of arrays # Simple assignment %Ho. A = ('Numbers' => [1, 2, 3],](https://present5.com/presentation/31b849674de10de71de40a48063efad3/image-52.jpg) Hashes of arrays # Simple assignment %Ho. A = ('Numbers' => [1, 2, 3], 'Names' => ['John', 'Joe, 'Ib']); # Adding an array to the hash my @tmp = split(' ', $line); $Ho. A{'New. Key'} = [@tmp]; # Appending a new element to one the arrays push(@{$Ho. A{'New. Key'}}, 'Some. Value'); # Two ways of accessing the structure print $Ho. A{'Numbers'}[1]; # prints 2 print $Ho. A{'Names'}->[1]; # prints Joe

Hashes of arrays # Simple assignment %Ho. A = ('Numbers' => [1, 2, 3], 'Names' => ['John', 'Joe, 'Ib']); # Adding an array to the hash my @tmp = split(' ', $line); $Ho. A{'New. Key'} = [@tmp]; # Appending a new element to one the arrays push(@{$Ho. A{'New. Key'}}, 'Some. Value'); # Two ways of accessing the structure print $Ho. A{'Numbers'}[1]; # prints 2 print $Ho. A{'Names'}->[1]; # prints Joe

Arrays of hashes # Simple assignment @Ao. H = ({'key 1' => 'value 1', 'key 2' => 'value 2}, {'newhashkey 1' => 'value 1', 'key 2' => 'value 2}, {'anotherhashkey 1' => 'value 1', 'key 2' => 'value 2}); # Adding anonymous hash to the array push(@Ao. H, {'key' => 'val', 'xkey' => 'xval'}); $Ao. H[2] = {'key' => 'val', 'xkey' => 'xval'}; # Adding single key/value pair in one of the hashes $Ao. H[1]{'New. Key'} = 'New. Value'; # Accessing the structure for (my $i = 0; $i <= $#Ao. H; $i++) { foreach my $key (keys %{$Ao. H[$i]}) { print $Ao. H[$i]{$key}, "n"; } }

Arrays of hashes # Simple assignment @Ao. H = ({'key 1' => 'value 1', 'key 2' => 'value 2}, {'newhashkey 1' => 'value 1', 'key 2' => 'value 2}, {'anotherhashkey 1' => 'value 1', 'key 2' => 'value 2}); # Adding anonymous hash to the array push(@Ao. H, {'key' => 'val', 'xkey' => 'xval'}); $Ao. H[2] = {'key' => 'val', 'xkey' => 'xval'}; # Adding single key/value pair in one of the hashes $Ao. H[1]{'New. Key'} = 'New. Value'; # Accessing the structure for (my $i = 0; $i <= $#Ao. H; $i++) { foreach my $key (keys %{$Ao. H[$i]}) { print $Ao. H[$i]{$key}, "n"; } }

Installing modules Perl has a large repository of free modules (libraries) available at CPAN. The chosen module has to be installed before use. 1) gunzip and (un)tar 2) run ”perl Makefile. PL” in the created directory 3) make, make test, make install 4) Alternatively use the interactive automated tool from commandline: 5) perl -MCPAN -e shell Lacking the rights to install modules, you can still use most of them by identifying the library file (. pm) and place it in the same directory as your program.

Installing modules Perl has a large repository of free modules (libraries) available at CPAN. The chosen module has to be installed before use. 1) gunzip and (un)tar 2) run ”perl Makefile. PL” in the created directory 3) make, make test, make install 4) Alternatively use the interactive automated tool from commandline: 5) perl -MCPAN -e shell Lacking the rights to install modules, you can still use most of them by identifying the library file (. pm) and place it in the same directory as your program.

Module types Most modules are object oriented where data and methods are encapsulated in the module. Some modules are more like a collection of subroutines. Sometimes you have to decide what to import in your namespace. Some can be used both ways. All modules contain an explanation on how to use them. The magic statement is use module;

Module types Most modules are object oriented where data and methods are encapsulated in the module. Some modules are more like a collection of subroutines. Sometimes you have to decide what to import in your namespace. Some can be used both ways. All modules contain an explanation on how to use them. The magic statement is use module;

Module – old style An example of a module that simply gives you access to two functions when you use it is the Crypt: : Simple module use Crypt: : Simple; my $data = encrypt(@stuff); my @same_stuff = decrypt($data); If the module allows you to import subroutines in your namespace it is usually done like this use somemodule qw(function 1 function 2 function 3); Modules like these are pretty trivial to use, but they are polluting your namespace.

Module – old style An example of a module that simply gives you access to two functions when you use it is the Crypt: : Simple module use Crypt: : Simple; my $data = encrypt(@stuff); my @same_stuff = decrypt($data); If the module allows you to import subroutines in your namespace it is usually done like this use somemodule qw(function 1 function 2 function 3); Modules like these are pretty trivial to use, but they are polluting your namespace.

Modules – object oriented style A nice OO module to introduce is CGI: : Minimal. The subroutines are available via the object and are called methods. The object data is not ”seen”, and is only accessible via the methods. There is no pollution of your namespace. use CGI: : Minimal; my $cgi = CGI: : Minimal->new; # Creating an object instance if ($cgi->truncated) { # Using a method &scream_about_bad_form; exit; } my $form_field_value = $cgi->param('some_field_name');

Modules – object oriented style A nice OO module to introduce is CGI: : Minimal. The subroutines are available via the object and are called methods. The object data is not ”seen”, and is only accessible via the methods. There is no pollution of your namespace. use CGI: : Minimal; my $cgi = CGI: : Minimal->new; # Creating an object instance if ($cgi->truncated) { # Using a method &scream_about_bad_form; exit; } my $form_field_value = $cgi->param('some_field_name');

Bio. Perl example Transforming sequence files The object is instantiated – a hash with parameters is used. use Bio: : Seq. IO; $in = Bio: : Seq. IO->new(-file => "inputfilename", -format => 'Fasta'); $out = Bio: : Seq. IO->new(-file => ">outputfilename", -format => 'EMBL'); while ( my $seq = $in->next_seq() ) { $out->write_seq($seq); }

Bio. Perl example Transforming sequence files The object is instantiated – a hash with parameters is used. use Bio: : Seq. IO; $in = Bio: : Seq. IO->new(-file => "inputfilename", -format => 'Fasta'); $out = Bio: : Seq. IO->new(-file => ">outputfilename", -format => 'EMBL'); while ( my $seq = $in->next_seq() ) { $out->write_seq($seq); }

Creating a subroutine collection Collect your useful subroutines in a file. End the file with 1; Use the collection by requiring the file in your program. #!/usr/bin/perl –w require ”mysubcollection. pl”; This is easy, but a beginners solution.

Creating a subroutine collection Collect your useful subroutines in a file. End the file with 1; Use the collection by requiring the file in your program. #!/usr/bin/perl –w require ”mysubcollection. pl”; This is easy, but a beginners solution.

Creating your own OO module 1 package My. Module. Name; use strict; # This subroutine is automatically called (if it exists) when the last # reference to the object disappears or the program ends. sub DESTROY { my $self = shift @_; # close files perhaps } # This block is automatically called (if it exists) when the # module is loaded by the main program. Anything here is executed # BEFORE any statements in the main program. BEGIN { }

Creating your own OO module 1 package My. Module. Name; use strict; # This subroutine is automatically called (if it exists) when the last # reference to the object disappears or the program ends. sub DESTROY { my $self = shift @_; # close files perhaps } # This block is automatically called (if it exists) when the # module is loaded by the main program. Anything here is executed # BEFORE any statements in the main program. BEGIN { }

Creating your own OO module 2 # Instantiating (creating) a new module/class object. sub new { my ($self, $filename) = @_; my $hash = {}; $self->_error("No file name given") unless $filename; my $filehandle; open($filehandle, $filename) or $self->error("Can't open file: $filenamen. Reason: $!"); while (defined (my $line = <$filehandle>)) { next unless $line =~ m/^>S+/; # Compute on file } $hash->{'_File'} = $filehandle; return bless($hash, ref($self) || $self); }

Creating your own OO module 2 # Instantiating (creating) a new module/class object. sub new { my ($self, $filename) = @_; my $hash = {}; $self->_error("No file name given") unless $filename; my $filehandle; open($filehandle, $filename) or $self->error("Can't open file: $filenamen. Reason: $!"); while (defined (my $line = <$filehandle>)) { next unless $line =~ m/^>S+/; # Compute on file } $hash->{'_File'} = $filehandle; return bless($hash, ref($self) || $self); }

Creating your own OO module 3 # Private internal subroutine to handle errors gracefully. sub _error { my ($self, $msg) = @_; chomp $msg; warn "$msgn"; exit; } # Method sub Name { my $self = shift @_; return $self->{'Name'} if $self->{'Name'}; return undef; }

Creating your own OO module 3 # Private internal subroutine to handle errors gracefully. sub _error { my ($self, $msg) = @_; chomp $msg; warn "$msgn"; exit; } # Method sub Name { my $self = shift @_; return $self->{'Name'} if $self->{'Name'}; return undef; }

Advice 1 Know your problem Very often the reason for having difficulty in programming is that you do not know the problem; you have not studied the input enough and seen all the patterns in the data. You have not analyzed the task sufficiently and thought about all implications and consequences. Know your tool Perl is the tool and when in a learning phase (and we all are) you do not know what Perl is capable of doing to ease your task. You must investigate Perl in depth. It is better for rapid programming to know a small part very well, instead of just the surface of most Perl. On the other hand, when faced with a problem, having surface knowledge of most Perl enables you to zoom in on features that might help you.

Advice 1 Know your problem Very often the reason for having difficulty in programming is that you do not know the problem; you have not studied the input enough and seen all the patterns in the data. You have not analyzed the task sufficiently and thought about all implications and consequences. Know your tool Perl is the tool and when in a learning phase (and we all are) you do not know what Perl is capable of doing to ease your task. You must investigate Perl in depth. It is better for rapid programming to know a small part very well, instead of just the surface of most Perl. On the other hand, when faced with a problem, having surface knowledge of most Perl enables you to zoom in on features that might help you.

Advice 2 Get started You should not wait until a problem is completely understood or Perl is completely learned before programming. Very often deeper understanding settles as you program, but you must have the core of understanding first. Your assumptions trip you up Whenever there is a bug in the program it is because you have assumed something about the data or problem, which is not true, or something about how Perl works, which is false. Learn to recognize your assumptions and when found, verify that they are true. Read what it says, not what you think it says In the same line as above. Often people do not read the text properly. Learn to really see the code/input data/problem description.

Advice 2 Get started You should not wait until a problem is completely understood or Perl is completely learned before programming. Very often deeper understanding settles as you program, but you must have the core of understanding first. Your assumptions trip you up Whenever there is a bug in the program it is because you have assumed something about the data or problem, which is not true, or something about how Perl works, which is false. Learn to recognize your assumptions and when found, verify that they are true. Read what it says, not what you think it says In the same line as above. Often people do not read the text properly. Learn to really see the code/input data/problem description.