7b32ebf2308989ca7117854eb1a116fc.ppt

- Количество слайдов: 49

PERFORMANCE MANAGEMENT POLICIES OF HEALTH SYSTEMS IN TURKEY AND ENGLAND: A CRITICAL COMPARATIVE REVIEW Dr. Pinar Guven-Uslu Norwich Business School, University of East Anglia, UK p. guven@uea. ac. uk Dr. Gulbiye Yenimahalleli Yasar Assist. Professor, University of Ankara, Turkey gulbiyey@yahoo. com

PERFORMANCE MANAGEMENT POLICIES OF HEALTH SYSTEMS IN TURKEY AND ENGLAND: A CRITICAL COMPARATIVE REVIEW Dr. Pinar Guven-Uslu Norwich Business School, University of East Anglia, UK p. guven@uea. ac. uk Dr. Gulbiye Yenimahalleli Yasar Assist. Professor, University of Ankara, Turkey gulbiyey@yahoo. com

Aim of the paper To investigate recent policy changes around performance management in the Turkish health care system and comparisons with English health service management.

Aim of the paper To investigate recent policy changes around performance management in the Turkish health care system and comparisons with English health service management.

Performance management related changes in Turkish health care system Turkey used to run a nationalised health system during the five decades. It was faced with serious problems; due to the lack of interest of the health authorities Thus, Turkish health system entered to the eighties with various problems (Aksakoglu, 2011; Yavuz, 2011).

Performance management related changes in Turkish health care system Turkey used to run a nationalised health system during the five decades. It was faced with serious problems; due to the lack of interest of the health authorities Thus, Turkish health system entered to the eighties with various problems (Aksakoglu, 2011; Yavuz, 2011).

Turkish health care system has been experiencing neoliberal transformation since the coup d’état in 1980. Reform proposals of the 1990 s focused on ◦ ◦ ◦ ◦ the introduction of a general health insurance (GHI) system, decentralisation, introduction of a family medicine scheme, purchaser-provider split, contracting out, quasi-markets, improvement of management information systems (Mo. H, 1993). Subsequent attempts have been made by “Health Transformation Program” (HTP) since 2003.

Turkish health care system has been experiencing neoliberal transformation since the coup d’état in 1980. Reform proposals of the 1990 s focused on ◦ ◦ ◦ ◦ the introduction of a general health insurance (GHI) system, decentralisation, introduction of a family medicine scheme, purchaser-provider split, contracting out, quasi-markets, improvement of management information systems (Mo. H, 1993). Subsequent attempts have been made by “Health Transformation Program” (HTP) since 2003.

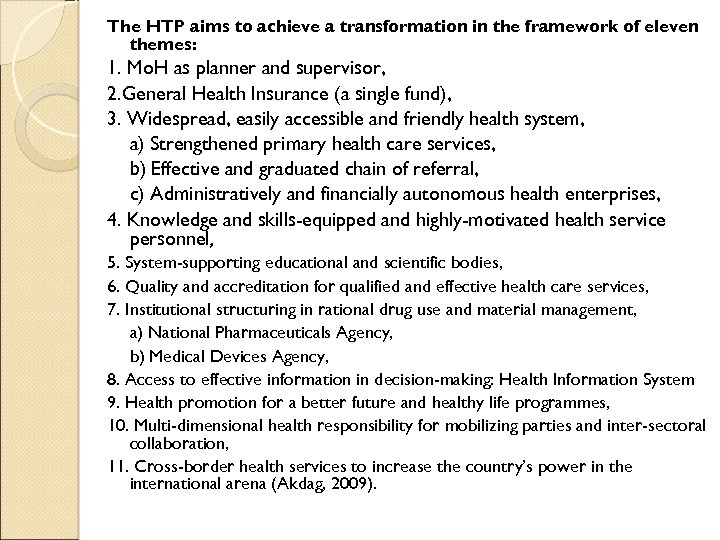

The HTP aims to achieve a transformation in the framework of eleven themes: 1. Mo. H as planner and supervisor, 2. General Health Insurance (a single fund), 3. Widespread, easily accessible and friendly health system, a) Strengthened primary health care services, b) Effective and graduated chain of referral, c) Administratively and financially autonomous health enterprises, 4. Knowledge and skills-equipped and highly-motivated health service personnel, 5. System-supporting educational and scientific bodies, 6. Quality and accreditation for qualified and effective health care services, 7. Institutional structuring in rational drug use and material management, a) National Pharmaceuticals Agency, b) Medical Devices Agency, 8. Access to effective information in decision-making: Health Information System 9. Health promotion for a better future and healthy life programmes, 10. Multi-dimensional health responsibility for mobilizing parties and inter-sectoral collaboration, 11. Cross-border health services to increase the country’s power in the international arena (Akdag, 2009).

The HTP aims to achieve a transformation in the framework of eleven themes: 1. Mo. H as planner and supervisor, 2. General Health Insurance (a single fund), 3. Widespread, easily accessible and friendly health system, a) Strengthened primary health care services, b) Effective and graduated chain of referral, c) Administratively and financially autonomous health enterprises, 4. Knowledge and skills-equipped and highly-motivated health service personnel, 5. System-supporting educational and scientific bodies, 6. Quality and accreditation for qualified and effective health care services, 7. Institutional structuring in rational drug use and material management, a) National Pharmaceuticals Agency, b) Medical Devices Agency, 8. Access to effective information in decision-making: Health Information System 9. Health promotion for a better future and healthy life programmes, 10. Multi-dimensional health responsibility for mobilizing parties and inter-sectoral collaboration, 11. Cross-border health services to increase the country’s power in the international arena (Akdag, 2009).

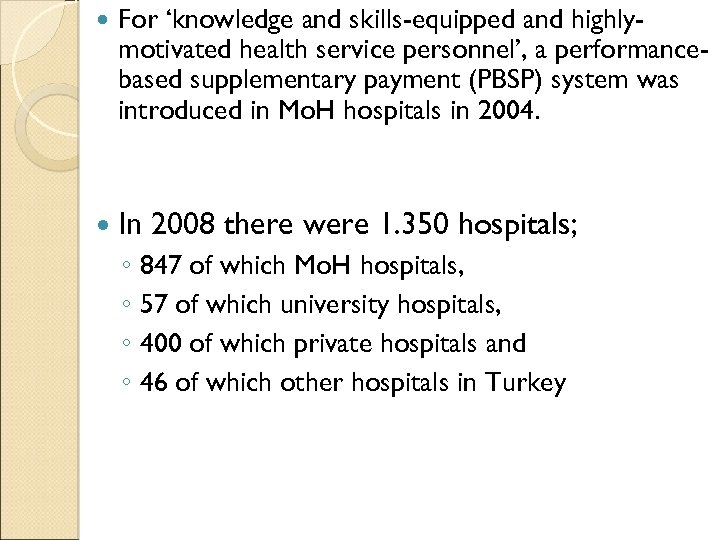

For ‘knowledge and skills-equipped and highlymotivated health service personnel’, a performancebased supplementary payment (PBSP) system was introduced in Mo. H hospitals in 2004. In 2008 there were 1. 350 hospitals; ◦ 847 of which Mo. H hospitals, ◦ 57 of which university hospitals, ◦ 400 of which private hospitals and ◦ 46 of which other hospitals in Turkey

For ‘knowledge and skills-equipped and highlymotivated health service personnel’, a performancebased supplementary payment (PBSP) system was introduced in Mo. H hospitals in 2004. In 2008 there were 1. 350 hospitals; ◦ 847 of which Mo. H hospitals, ◦ 57 of which university hospitals, ◦ 400 of which private hospitals and ◦ 46 of which other hospitals in Turkey

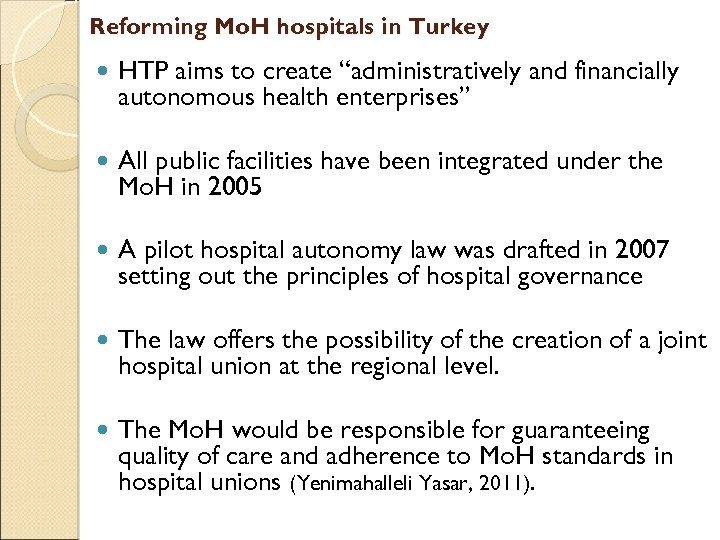

Reforming Mo. H hospitals in Turkey HTP aims to create “administratively and financially autonomous health enterprises” All public facilities have been integrated under the Mo. H in 2005 A pilot hospital autonomy law was drafted in 2007 setting out the principles of hospital governance The law offers the possibility of the creation of a joint hospital union at the regional level. The Mo. H would be responsible for guaranteeing quality of care and adherence to Mo. H standards in hospital unions (Yenimahalleli Yasar, 2011).

Reforming Mo. H hospitals in Turkey HTP aims to create “administratively and financially autonomous health enterprises” All public facilities have been integrated under the Mo. H in 2005 A pilot hospital autonomy law was drafted in 2007 setting out the principles of hospital governance The law offers the possibility of the creation of a joint hospital union at the regional level. The Mo. H would be responsible for guaranteeing quality of care and adherence to Mo. H standards in hospital unions (Yenimahalleli Yasar, 2011).

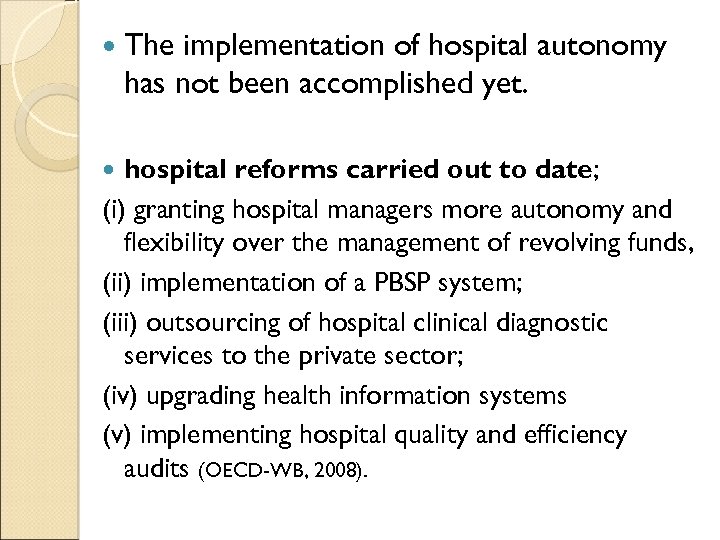

The implementation of hospital autonomy has not been accomplished yet. hospital reforms carried out to date; (i) granting hospital managers more autonomy and flexibility over the management of revolving funds, (ii) implementation of a PBSP system; (iii) outsourcing of hospital clinical diagnostic services to the private sector; (iv) upgrading health information systems (v) implementing hospital quality and efficiency audits (OECD-WB, 2008).

The implementation of hospital autonomy has not been accomplished yet. hospital reforms carried out to date; (i) granting hospital managers more autonomy and flexibility over the management of revolving funds, (ii) implementation of a PBSP system; (iii) outsourcing of hospital clinical diagnostic services to the private sector; (iv) upgrading health information systems (v) implementing hospital quality and efficiency audits (OECD-WB, 2008).

Objectives of the PBSP system in Turkey The PBSP system has aimed to encourage job motivation and productivity among public sector health personnel claiming shortage of both physicians and nurses. ◦ the ratio of health personnel to population was lower than in other middle-income and OECD countries, ◦ the majority of public doctors worked part-time and ◦ doctors preferred to work in the private sector. Another important objective is to improve performance of the Mo. H hospitals, focusing on quality of care, efficiency and patient satisfaction (Mo. H, 2008: 45; OECD-WB, 2008: 49).

Objectives of the PBSP system in Turkey The PBSP system has aimed to encourage job motivation and productivity among public sector health personnel claiming shortage of both physicians and nurses. ◦ the ratio of health personnel to population was lower than in other middle-income and OECD countries, ◦ the majority of public doctors worked part-time and ◦ doctors preferred to work in the private sector. Another important objective is to improve performance of the Mo. H hospitals, focusing on quality of care, efficiency and patient satisfaction (Mo. H, 2008: 45; OECD-WB, 2008: 49).

Historical development of the PBSP system in Turkey The PBSP system in Turkey can be examined under three phases: (a) Before 2004 (b) PBSP system in 2004 (c) Quality Improvement and Performance Evaluation System from 2005 onwards.

Historical development of the PBSP system in Turkey The PBSP system in Turkey can be examined under three phases: (a) Before 2004 (b) PBSP system in 2004 (c) Quality Improvement and Performance Evaluation System from 2005 onwards.

(a) Before 2004: The staff working in the institutions with revolving budgets started to get payment from the revenues of revolving budgets since 1990 The major features of the system before 2004 are: a. Outsourced staff working in the services such as cleaning, security, data entry into computers and catering do not benefit from supplementary payment. b. Top supplementary payment rate is applied as 100 -120% for doctors, and 80% for other staff.

(a) Before 2004: The staff working in the institutions with revolving budgets started to get payment from the revenues of revolving budgets since 1990 The major features of the system before 2004 are: a. Outsourced staff working in the services such as cleaning, security, data entry into computers and catering do not benefit from supplementary payment. b. Top supplementary payment rate is applied as 100 -120% for doctors, and 80% for other staff.

(b) PBSP system in 2004: In 2004 the system was piloted Initially pilot has been realized for ten hospitals Subsequently expanded to the all Mo. H facilities Developed by strictly monitoring the changes and evaluating the feed backs Currently all 850 Mo. H hospitals have in place within the PBSP system

(b) PBSP system in 2004: In 2004 the system was piloted Initially pilot has been realized for ten hospitals Subsequently expanded to the all Mo. H facilities Developed by strictly monitoring the changes and evaluating the feed backs Currently all 850 Mo. H hospitals have in place within the PBSP system

(c) Quality Improvement and Performance Evaluation System from 2005 onwards: Introduced some elements of “internal markets” whereby the Mo. H Performance Management and Quality Improvement Unit implements a pay-for-performance scheme in Mo. H hospitals, linked to institutional performance criteria.

(c) Quality Improvement and Performance Evaluation System from 2005 onwards: Introduced some elements of “internal markets” whereby the Mo. H Performance Management and Quality Improvement Unit implements a pay-for-performance scheme in Mo. H hospitals, linked to institutional performance criteria.

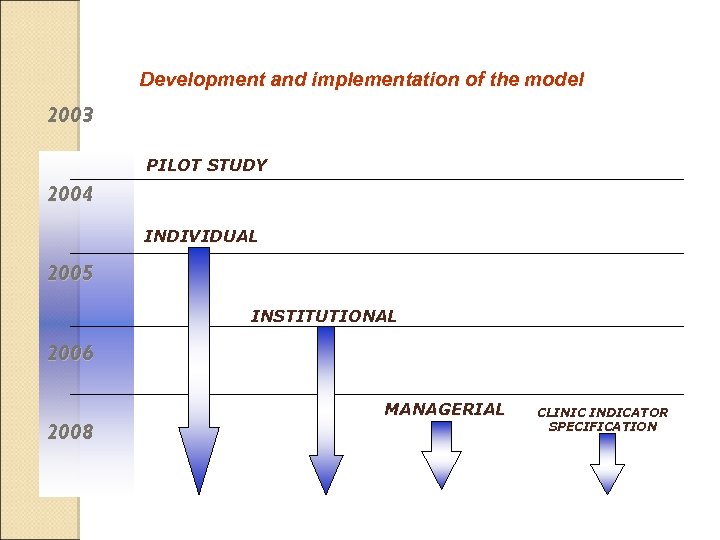

Development and implementation of the model 2003 PILOT STUDY 2004 INDIVIDUAL 2005 INSTITUTIONAL 2006 2008 MANAGERIAL CLINIC INDICATOR SPECIFICATION

Development and implementation of the model 2003 PILOT STUDY 2004 INDIVIDUAL 2005 INSTITUTIONAL 2006 2008 MANAGERIAL CLINIC INDICATOR SPECIFICATION

What is the PBSP system? An additional payment in addition to regular salaries. Base salary from line item budget. Performance-based payment from hospital earnings Bonus payments linked to performance of health personnel.

What is the PBSP system? An additional payment in addition to regular salaries. Base salary from line item budget. Performance-based payment from hospital earnings Bonus payments linked to performance of health personnel.

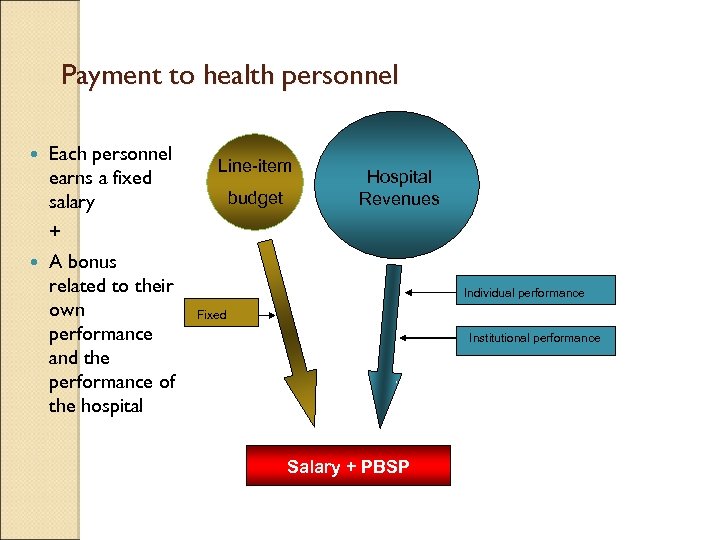

Payment to health personnel Each personnel earns a fixed salary + A bonus related to their own performance and the performance of the hospital Line-item budget Hospital Revenues Individual performance Fixed Institutional performance Salary + PBSP

Payment to health personnel Each personnel earns a fixed salary + A bonus related to their own performance and the performance of the hospital Line-item budget Hospital Revenues Individual performance Fixed Institutional performance Salary + PBSP

Individual performance measurement Each service is rated with a point Each clinician collects points from his/her tasks (load of service)

Individual performance measurement Each service is rated with a point Each clinician collects points from his/her tasks (load of service)

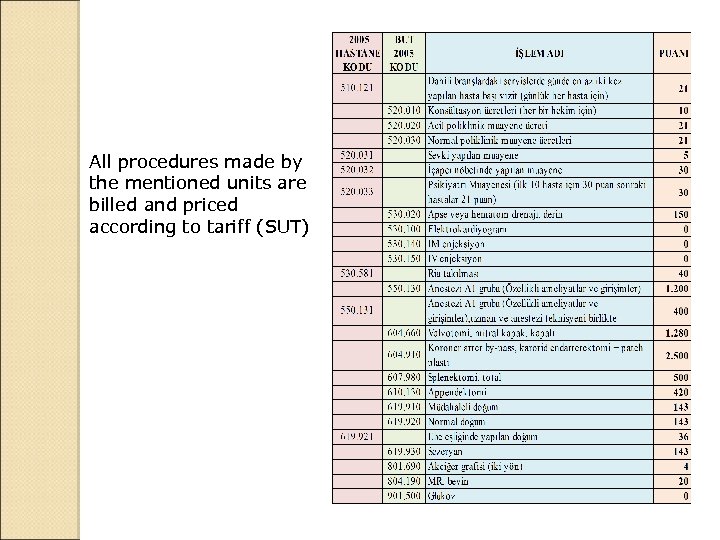

All procedures made by the mentioned units are billed and priced according to tariff (SUT)

All procedures made by the mentioned units are billed and priced according to tariff (SUT)

How does it work? Factors which determine how much health personnel will receive as performance-based payments: ◦ The total amount capped at 40% of hospital revenues. ◦ This total (capped) amount is subsequently adjusted based on institutional performance of the hospital (0 -1). ◦ An individual level performance score is calculated for each staff member. ◦ Total points score for a physician is adjusted by a job title coefficient

How does it work? Factors which determine how much health personnel will receive as performance-based payments: ◦ The total amount capped at 40% of hospital revenues. ◦ This total (capped) amount is subsequently adjusted based on institutional performance of the hospital (0 -1). ◦ An individual level performance score is calculated for each staff member. ◦ Total points score for a physician is adjusted by a job title coefficient

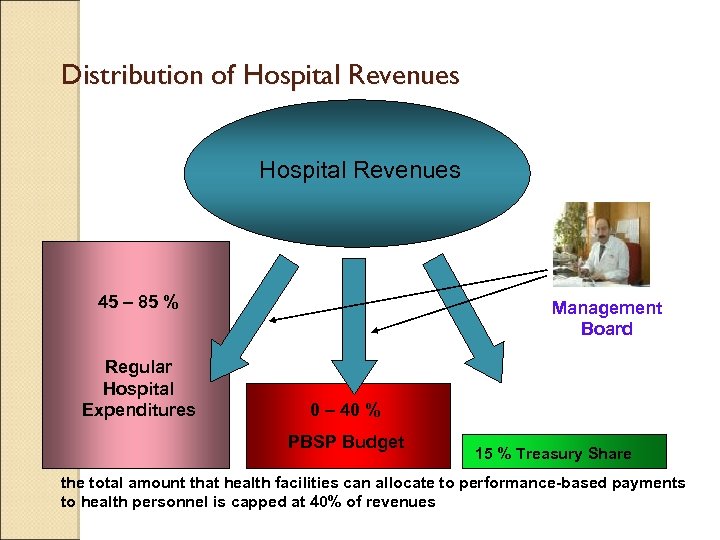

Distribution of Hospital Revenues 45 – 85 % Regular Hospital Expenditures Management Board 0 – 40 % PBSP Budget 15 % Treasury Share the total amount that health facilities can allocate to performance-based payments to health personnel is capped at 40% of revenues

Distribution of Hospital Revenues 45 – 85 % Regular Hospital Expenditures Management Board 0 – 40 % PBSP Budget 15 % Treasury Share the total amount that health facilities can allocate to performance-based payments to health personnel is capped at 40% of revenues

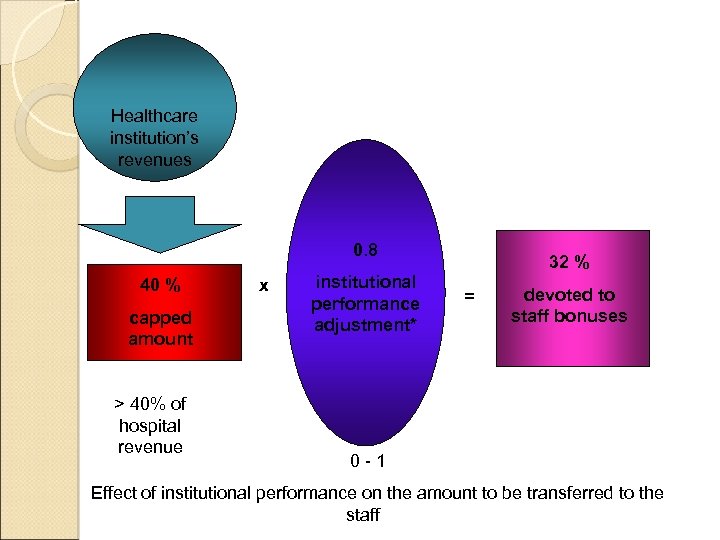

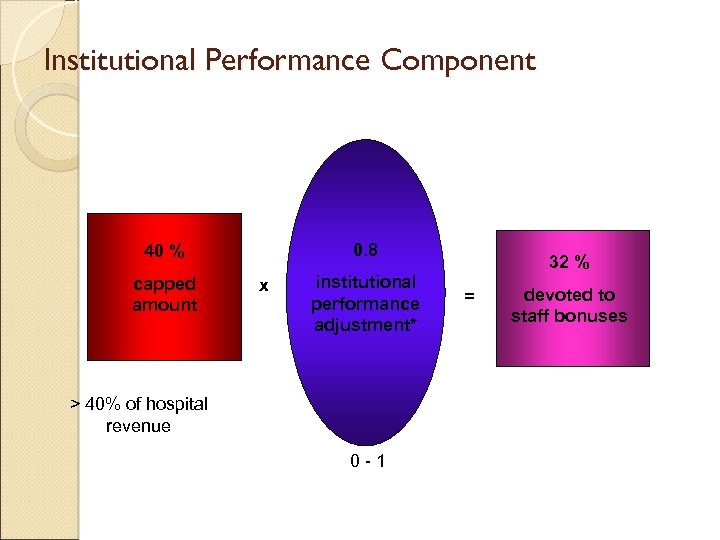

Healthcare institution’s revenues 0. 8 40 % capped amount > 40% of hospital revenue x institutional performance adjustment* 32 % = devoted to staff bonuses 0 -1 Effect of institutional performance on the amount to be transferred to the staff

Healthcare institution’s revenues 0. 8 40 % capped amount > 40% of hospital revenue x institutional performance adjustment* 32 % = devoted to staff bonuses 0 -1 Effect of institutional performance on the amount to be transferred to the staff

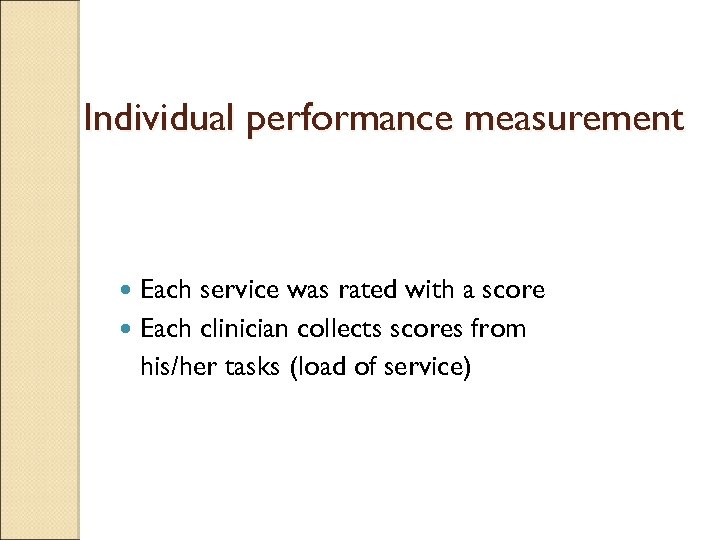

Individual performance measurement Each service was rated with a score Each clinician collects scores from his/her tasks (load of service)

Individual performance measurement Each service was rated with a score Each clinician collects scores from his/her tasks (load of service)

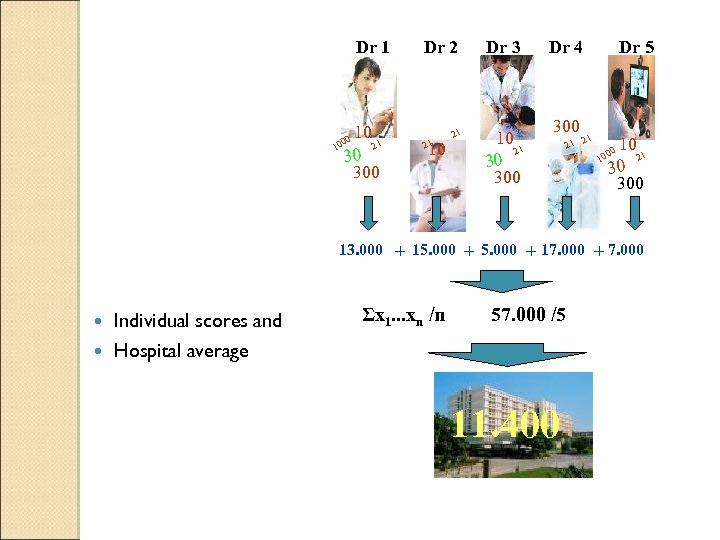

Dr 1 10 21 1 30 300 0 00 Dr 2 21 10 21 Dr 3 10 21 30 300 Dr 4 300 21 Dr 5 21 10 21 30 300 00 10 13. 000 + 15. 000 + 17. 000 + 7. 000 Individual scores and Hospital average Σx 1. . . xn /n 57. 000 /5 11. 400

Dr 1 10 21 1 30 300 0 00 Dr 2 21 10 21 Dr 3 10 21 30 300 Dr 4 300 21 Dr 5 21 10 21 30 300 00 10 13. 000 + 15. 000 + 17. 000 + 7. 000 Individual scores and Hospital average Σx 1. . . xn /n 57. 000 /5 11. 400

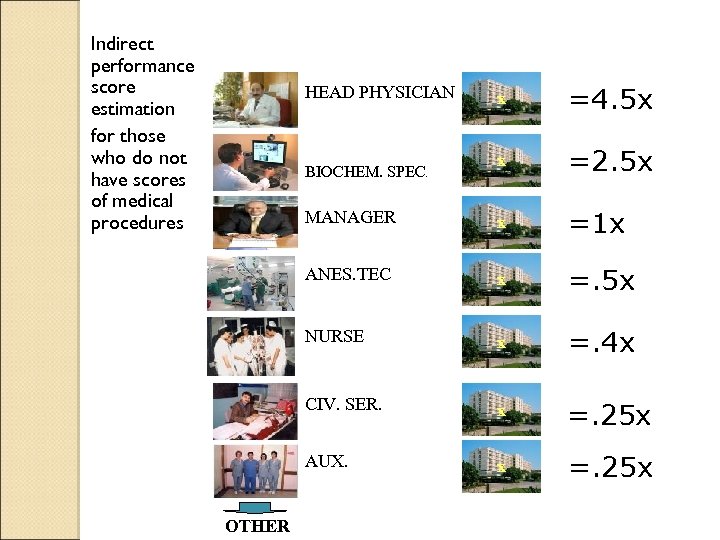

Indirect performance score estimation for those who do not have scores of medical procedures x =4. 5 x x =2. 5 x MANAGER x =1 x ANES. TEC x =. 5 x NURSE x =. 4 x CIV. SER. x =. 25 x AUX. x =. 25 x HEAD PHYSICIAN BIOCHEM. SPEC. OTHER

Indirect performance score estimation for those who do not have scores of medical procedures x =4. 5 x x =2. 5 x MANAGER x =1 x ANES. TEC x =. 5 x NURSE x =. 4 x CIV. SER. x =. 25 x AUX. x =. 25 x HEAD PHYSICIAN BIOCHEM. SPEC. OTHER

Adjustments The total points score for a physician is adjusted by, ◦ a job title coefficient: to measure workload aside from providing clinical care (i. e. administrative duties, teaching etc. ) ◦ the number of days the person has worked in that month. ◦ depending on whether the person is doing private practice or not (0. 4/1. 0).

Adjustments The total points score for a physician is adjusted by, ◦ a job title coefficient: to measure workload aside from providing clinical care (i. e. administrative duties, teaching etc. ) ◦ the number of days the person has worked in that month. ◦ depending on whether the person is doing private practice or not (0. 4/1. 0).

Institutional Performance Component 0. 8 40 % capped amount x institutional performance adjustment* > 40% of hospital revenue 0 -1 32 % = devoted to staff bonuses

Institutional Performance Component 0. 8 40 % capped amount x institutional performance adjustment* > 40% of hospital revenue 0 -1 32 % = devoted to staff bonuses

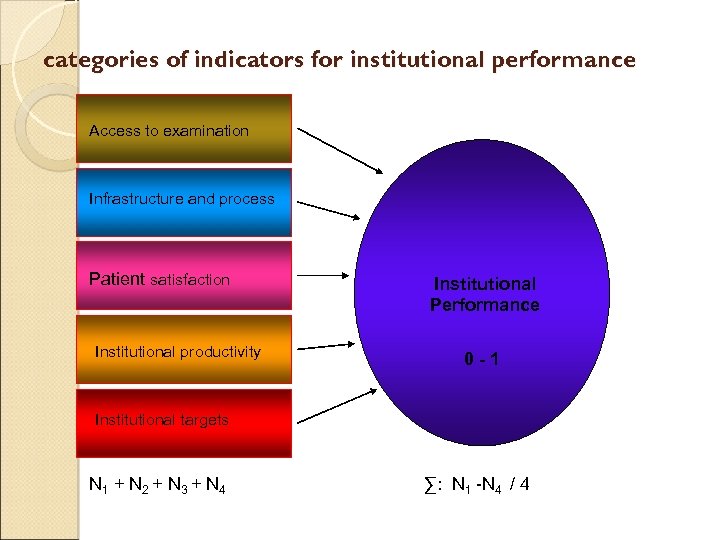

categories of indicators for institutional performance Access to examination Infrastructure and process Patient satisfaction Institutional productivity Institutional Performance 0 -1 Institutional targets N 1 + N 2 + N 3 + N 4 ∑: N 1 -N 4 / 4

categories of indicators for institutional performance Access to examination Infrastructure and process Patient satisfaction Institutional productivity Institutional Performance 0 -1 Institutional targets N 1 + N 2 + N 3 + N 4 ∑: N 1 -N 4 / 4

Upper Cap Restrictions Types of upper cap restrictions in the system: ◦Cap for distributing hospital revenues (40 %) ◦Control of fluid cash (Managerial Board) ◦Multiplier of basic salary for profession

Upper Cap Restrictions Types of upper cap restrictions in the system: ◦Cap for distributing hospital revenues (40 %) ◦Control of fluid cash (Managerial Board) ◦Multiplier of basic salary for profession

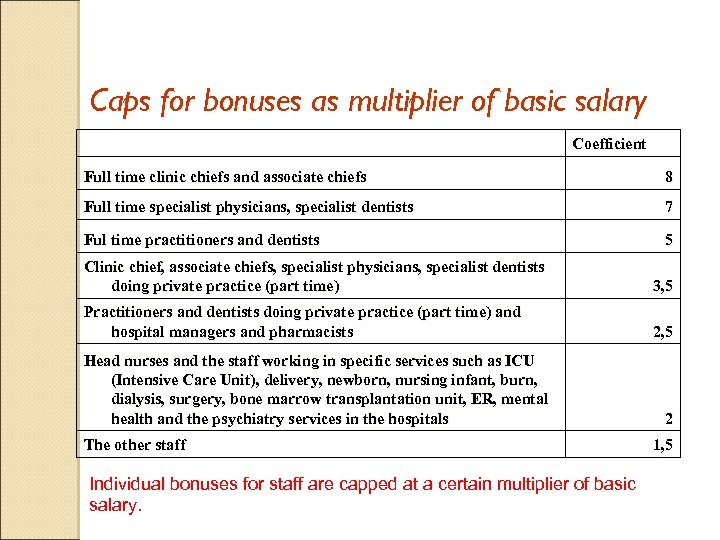

Caps for bonuses as multiplier of basic salary Coefficient Full time clinic chiefs and associate chiefs 8 Full time specialist physicians, specialist dentists 7 Ful time practitioners and dentists 5 Clinic chief, associate chiefs, specialist physicians, specialist dentists doing private practice (part time) 3, 5 Practitioners and dentists doing private practice (part time) and hospital managers and pharmacists 2, 5 Head nurses and the staff working in specific services such as ICU (Intensive Care Unit), delivery, newborn, nursing infant, burn, dialysis, surgery, bone marrow transplantation unit, ER, mental health and the psychiatry services in the hospitals The other staff Individual bonuses for staff are capped at a certain multiplier of basic salary. 2 1, 5

Caps for bonuses as multiplier of basic salary Coefficient Full time clinic chiefs and associate chiefs 8 Full time specialist physicians, specialist dentists 7 Ful time practitioners and dentists 5 Clinic chief, associate chiefs, specialist physicians, specialist dentists doing private practice (part time) 3, 5 Practitioners and dentists doing private practice (part time) and hospital managers and pharmacists 2, 5 Head nurses and the staff working in specific services such as ICU (Intensive Care Unit), delivery, newborn, nursing infant, burn, dialysis, surgery, bone marrow transplantation unit, ER, mental health and the psychiatry services in the hospitals The other staff Individual bonuses for staff are capped at a certain multiplier of basic salary. 2 1, 5

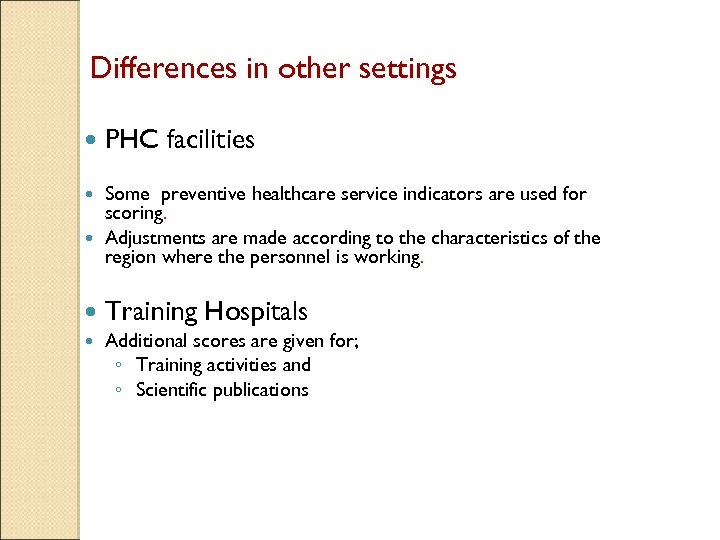

Differences in other settings PHC facilities Some preventive healthcare service indicators are used for scoring. Adjustments are made according to the characteristics of the region where the personnel is working. Training Hospitals Additional scores are given for; ◦ Training activities and ◦ Scientific publications

Differences in other settings PHC facilities Some preventive healthcare service indicators are used for scoring. Adjustments are made according to the characteristics of the region where the personnel is working. Training Hospitals Additional scores are given for; ◦ Training activities and ◦ Scientific publications

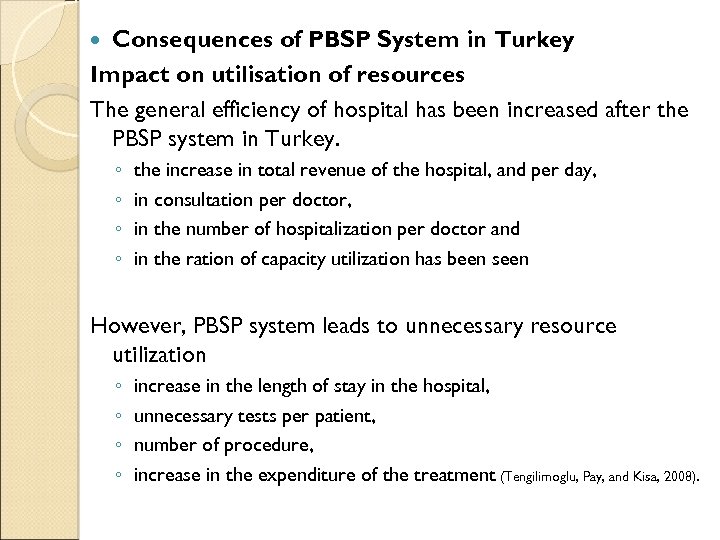

Consequences of PBSP System in Turkey Impact on utilisation of resources The general efficiency of hospital has been increased after the PBSP system in Turkey. ◦ ◦ the increase in total revenue of the hospital, and per day, in consultation per doctor, in the number of hospitalization per doctor and in the ration of capacity utilization has been seen However, PBSP system leads to unnecessary resource utilization ◦ ◦ increase in the length of stay in the hospital, unnecessary tests per patient, number of procedure, increase in the expenditure of the treatment (Tengilimoglu, Pay, and Kisa, 2008).

Consequences of PBSP System in Turkey Impact on utilisation of resources The general efficiency of hospital has been increased after the PBSP system in Turkey. ◦ ◦ the increase in total revenue of the hospital, and per day, in consultation per doctor, in the number of hospitalization per doctor and in the ration of capacity utilization has been seen However, PBSP system leads to unnecessary resource utilization ◦ ◦ increase in the length of stay in the hospital, unnecessary tests per patient, number of procedure, increase in the expenditure of the treatment (Tengilimoglu, Pay, and Kisa, 2008).

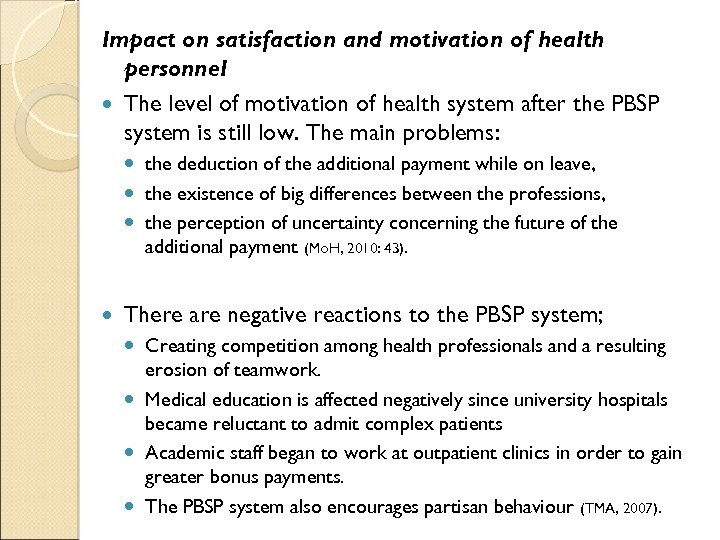

Impact on satisfaction and motivation of health personnel The level of motivation of health system after the PBSP system is still low. The main problems: the deduction of the additional payment while on leave, the existence of big differences between the professions, the perception of uncertainty concerning the future of the additional payment (Mo. H, 2010: 43). There are negative reactions to the PBSP system; Creating competition among health professionals and a resulting erosion of teamwork. Medical education is affected negatively since university hospitals became reluctant to admit complex patients Academic staff began to work at outpatient clinics in order to gain greater bonus payments. The PBSP system also encourages partisan behaviour (TMA, 2007).

Impact on satisfaction and motivation of health personnel The level of motivation of health system after the PBSP system is still low. The main problems: the deduction of the additional payment while on leave, the existence of big differences between the professions, the perception of uncertainty concerning the future of the additional payment (Mo. H, 2010: 43). There are negative reactions to the PBSP system; Creating competition among health professionals and a resulting erosion of teamwork. Medical education is affected negatively since university hospitals became reluctant to admit complex patients Academic staff began to work at outpatient clinics in order to gain greater bonus payments. The PBSP system also encourages partisan behaviour (TMA, 2007).

There are some significant differences among personnel’s review about PBSP system in terms of gender, education status, vocations and departments. The health personnel found this system is unjust because of both the imbalance of fee rates between the doctors themselves and doctors with other personnel (Gazi et al, 2009).

There are some significant differences among personnel’s review about PBSP system in terms of gender, education status, vocations and departments. The health personnel found this system is unjust because of both the imbalance of fee rates between the doctors themselves and doctors with other personnel (Gazi et al, 2009).

Impact on health services According to a research which investigates the effects of the PBSP system on primary health care in Bursa shows that there had been some differences in health care quantities before and after the PBSP system. As an example; while examination and laboratory study numbers had increased, the ratio of referring had decreased. Besides, infant mortality rates had decreased, risk groups’ mean follow up rates had increased. In general, these differences have to be seen positive in terms of health care. But, because of the structure of the system, to have a judgement about the quality of the care is impossible. The study concludes that if care has been evaluated not only in terms of quantity but also quality, beyond the desired, there had been some unfavourable returns of the system. For that reason leaving the system or to restructure is thought to be appropriate (Kizek et al, 2010).

Impact on health services According to a research which investigates the effects of the PBSP system on primary health care in Bursa shows that there had been some differences in health care quantities before and after the PBSP system. As an example; while examination and laboratory study numbers had increased, the ratio of referring had decreased. Besides, infant mortality rates had decreased, risk groups’ mean follow up rates had increased. In general, these differences have to be seen positive in terms of health care. But, because of the structure of the system, to have a judgement about the quality of the care is impossible. The study concludes that if care has been evaluated not only in terms of quantity but also quality, beyond the desired, there had been some unfavourable returns of the system. For that reason leaving the system or to restructure is thought to be appropriate (Kizek et al, 2010).

Performance Management Changes in English National Health Service Since the publication of ‘The New NHS: Modern and Dependable’ white paper (Do. H, 1997), the UK’s National Health Service (NHS) has undergone considerable structural reorganisation. This was a ten year programme that aimed to provide ‘the best healthcare in the world’ (Do. H, 1998). Cost and service quality improvements were expected to be achieved through greater collaboration and partnership, benchmarking and the implementation of performance related management. The annual publication of ‘league tables of hospital efficiency’, however, allowed direct cross-organisation comparison on the basis of cost alone and this, therefore, was inclined to shift priorities towards cost of care at the expense of quality of care (Jones, 2002).

Performance Management Changes in English National Health Service Since the publication of ‘The New NHS: Modern and Dependable’ white paper (Do. H, 1997), the UK’s National Health Service (NHS) has undergone considerable structural reorganisation. This was a ten year programme that aimed to provide ‘the best healthcare in the world’ (Do. H, 1998). Cost and service quality improvements were expected to be achieved through greater collaboration and partnership, benchmarking and the implementation of performance related management. The annual publication of ‘league tables of hospital efficiency’, however, allowed direct cross-organisation comparison on the basis of cost alone and this, therefore, was inclined to shift priorities towards cost of care at the expense of quality of care (Jones, 2002).

In order to address some of these critics, the Government then introduced the ‘star rating’ system to measure organisational performance of hopsitals with first wave implementaiton in 2002 -03. This was a multi-dimensional measure combining financial and nonfinancial performance measures that are defined by the Do. H. It was an adoptation of a balanced score card approach (Kaplan and Norton, 2001) with an expectation to combine financial outcomes such as balanced budget, with patient satisfaction outcomes such as 4 hours waiting times to be seen at an Accident and Emergency Unit, or hospital cleanliness etc. Each defined area of performance had a centrally determined target to be achieved by hospitals.

In order to address some of these critics, the Government then introduced the ‘star rating’ system to measure organisational performance of hopsitals with first wave implementaiton in 2002 -03. This was a multi-dimensional measure combining financial and nonfinancial performance measures that are defined by the Do. H. It was an adoptation of a balanced score card approach (Kaplan and Norton, 2001) with an expectation to combine financial outcomes such as balanced budget, with patient satisfaction outcomes such as 4 hours waiting times to be seen at an Accident and Emergency Unit, or hospital cleanliness etc. Each defined area of performance had a centrally determined target to be achieved by hospitals.

The NHS performance ratings system placed NHS hospitals in England into one of four categories: trusts with the highest levels of performance are awarded a performance rating of three stars trusts that are performing well overall, but have not quite reached the same consistently high standards, are awarded a performance rating of two stars trusts where there is some cause for concern regarding particular areas of performance are awarded a performance rating of one star trusts that have shown the poorest levels of performance against the indicators or little progress in implementing clinical governance are awarded a performance rating of zero stars

The NHS performance ratings system placed NHS hospitals in England into one of four categories: trusts with the highest levels of performance are awarded a performance rating of three stars trusts that are performing well overall, but have not quite reached the same consistently high standards, are awarded a performance rating of two stars trusts where there is some cause for concern regarding particular areas of performance are awarded a performance rating of one star trusts that have shown the poorest levels of performance against the indicators or little progress in implementing clinical governance are awarded a performance rating of zero stars

Where a trust has a low rating based on poor performance on a number of key targets and indicators, it meant that performance must be improved in a number of key areas. The Government's purpose in introducing star ratings was ◦ to lessen variation in performance between trusts, ◦ raise standards, and ◦ make services more accountable to the public. The system was abolished in 2004 and was replaced by a new system of annual health checks. Some of the main performance indicators remained but the philosophy behind centrally rating of performance, ranking of organisations according to that calculation and publication of these rankings in public domain started to change.

Where a trust has a low rating based on poor performance on a number of key targets and indicators, it meant that performance must be improved in a number of key areas. The Government's purpose in introducing star ratings was ◦ to lessen variation in performance between trusts, ◦ raise standards, and ◦ make services more accountable to the public. The system was abolished in 2004 and was replaced by a new system of annual health checks. Some of the main performance indicators remained but the philosophy behind centrally rating of performance, ranking of organisations according to that calculation and publication of these rankings in public domain started to change.

The Healthcare Commission replaced the Commission for Healthcare Improvement in March 2004 and introduced the annual health check with a belief that "health checks" can be used to provide an annual report on each health care organisation. This was a self declaration by hospitals on their organisational performance. A number of trusts randomly selected would be audited to assess whether they had made a fair declaration of their organisational affairs.

The Healthcare Commission replaced the Commission for Healthcare Improvement in March 2004 and introduced the annual health check with a belief that "health checks" can be used to provide an annual report on each health care organisation. This was a self declaration by hospitals on their organisational performance. A number of trusts randomly selected would be audited to assess whether they had made a fair declaration of their organisational affairs.

Around the same time in 2004, the Foundation Trust concept was introduced to the NHS to devolve decision making from central to local organisations and communities. It represents a profound change in the history of the NHS and the way in which hospital services are managed and provided. FTs have been assessed as performing as expected by the Government according to targets set for them. Some of the requirements to become a foundation trust were; ◦ balanced budget (no deficit), ◦ have and operate a performance management framework, ◦ meet national clinical targets such as A&E waiting time of 4 hours. They have the freedom to use their surplus in their preferred ways. They are regulated by an independent body Monitor.

Around the same time in 2004, the Foundation Trust concept was introduced to the NHS to devolve decision making from central to local organisations and communities. It represents a profound change in the history of the NHS and the way in which hospital services are managed and provided. FTs have been assessed as performing as expected by the Government according to targets set for them. Some of the requirements to become a foundation trust were; ◦ balanced budget (no deficit), ◦ have and operate a performance management framework, ◦ meet national clinical targets such as A&E waiting time of 4 hours. They have the freedom to use their surplus in their preferred ways. They are regulated by an independent body Monitor.

From 2006, an annual health check replaced the 'star ratings' assessment system and looked at a much broader range of issues than the targets used previously. It sought to make much better use of the data, judgements and expertise of others to focus on measuring what matters to people who use and provide healthcare services. Trusts had to declare their compliance with the core standards set out in Standards for Better Health[9][10], published by the Department of Health in 2004.

From 2006, an annual health check replaced the 'star ratings' assessment system and looked at a much broader range of issues than the targets used previously. It sought to make much better use of the data, judgements and expertise of others to focus on measuring what matters to people who use and provide healthcare services. Trusts had to declare their compliance with the core standards set out in Standards for Better Health[9][10], published by the Department of Health in 2004.

The Standards for Better Health (Sf. BH) document sets out the level of quality that all NHS organisations are expected to meet or aspire to in the delivery of care. The document contains 24 standards with 44 elements that healthcare organisations are annually assessed against. From April 1 st 2009 the responsibility for regulating Sf. BH has moved to the Care Quality Commission. The standards have been developed with two principle objectives; ◦ first, they provide a common set of requirements applying across all health care organisations to ensure that healthcare is commissioned and provided safely and are of a high quality; ◦ second, they provide a framework for continuous improvement in the overall quality of care that people receive.

The Standards for Better Health (Sf. BH) document sets out the level of quality that all NHS organisations are expected to meet or aspire to in the delivery of care. The document contains 24 standards with 44 elements that healthcare organisations are annually assessed against. From April 1 st 2009 the responsibility for regulating Sf. BH has moved to the Care Quality Commission. The standards have been developed with two principle objectives; ◦ first, they provide a common set of requirements applying across all health care organisations to ensure that healthcare is commissioned and provided safely and are of a high quality; ◦ second, they provide a framework for continuous improvement in the overall quality of care that people receive.

The standards set out in Sf. BH are organised within seven "domains", which are designed to cover the full range of health care as defined in the Health and Social Care (Community Health and Standards) Act 2003. The domains cover all areas of health care, including prevention, and are described and monitored in terms of outcomes. The seven domains are: Safety Clinical and Cost Effectiveness Governance Patient Focus Accessible and Responsive Care Environment and Amenities Public Health

The standards set out in Sf. BH are organised within seven "domains", which are designed to cover the full range of health care as defined in the Health and Social Care (Community Health and Standards) Act 2003. The domains cover all areas of health care, including prevention, and are described and monitored in terms of outcomes. The seven domains are: Safety Clinical and Cost Effectiveness Governance Patient Focus Accessible and Responsive Care Environment and Amenities Public Health

From April 2010 all healthcare providers working for the NHS will be legally obliged to publish "quality accounts" on safety, patients’ experience, and clinical outcomes, in the same way that they publish financial accounts. The accounts will augment the government’s agenda on choice by giving patients information - accessible through NHS websites - on all health services in England, to help them decide where to be treated. Legislation will dictate that all providers produce their first quality account - carrying a pre-selected set of measures for public consumption - at the end of 2009 -10. This means deciding which measures will be included, and making sure solid data collection is in place to report them, before the end of March 2010.

From April 2010 all healthcare providers working for the NHS will be legally obliged to publish "quality accounts" on safety, patients’ experience, and clinical outcomes, in the same way that they publish financial accounts. The accounts will augment the government’s agenda on choice by giving patients information - accessible through NHS websites - on all health services in England, to help them decide where to be treated. Legislation will dictate that all providers produce their first quality account - carrying a pre-selected set of measures for public consumption - at the end of 2009 -10. This means deciding which measures will be included, and making sure solid data collection is in place to report them, before the end of March 2010.

Comparison With a contextualist approach to this analysis, we conclude that each country’s healthcare system is in important ways unique and highly local: ◦ ◦ ◦ a product of its distinctive history, its particular politics, its economic system, its geographical and cultural diversity, and its values. We grouped our analysis according to three dimensions of contextual approach to change management.

Comparison With a contextualist approach to this analysis, we conclude that each country’s healthcare system is in important ways unique and highly local: ◦ ◦ ◦ a product of its distinctive history, its particular politics, its economic system, its geographical and cultural diversity, and its values. We grouped our analysis according to three dimensions of contextual approach to change management.

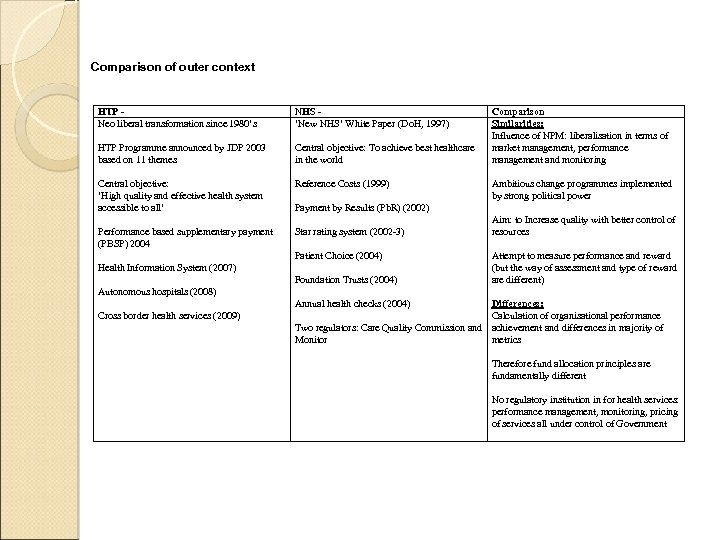

Comparison of outer context HTP Neo liberal transformation since 1980’s NHS ‘New NHS’ White Paper (Do. H, 1997) HTP Programme announced by JDP 2003 based on 11 themes Central objective: To achieve best healthcare in the world Central objective: ‘High quality and effective health system accessible to all’ Reference Costs (1999) Performance based supplementary payment (PBSP) 2004 Star rating system (2002 -3) Comparison Similarities: Influence of NPM: liberalisation in terms of market management, performance management and monitoring Ambitious change programmes implemented by strong political power Payment by Results (Pb. R) (2002) Patient Choice (2004) Health Information System (2007) Foundation Trusts (2004) Aim: to Increase quality with better control of resources Attempt to measure performance and reward (but the way of assessment and type of reward are different) Autonomous hospitals (2008) Annual health checks (2004) Cross border health services (2009) Differences: Calculation of organisational performance Two regulators: Care Quality Commission and achievement and differences in majority of Monitor metrics Therefore fund allocation principles are fundamentally different No regulatory institution in for health services: performance management, monitoring, pricing of services all under control of Government

Comparison of outer context HTP Neo liberal transformation since 1980’s NHS ‘New NHS’ White Paper (Do. H, 1997) HTP Programme announced by JDP 2003 based on 11 themes Central objective: To achieve best healthcare in the world Central objective: ‘High quality and effective health system accessible to all’ Reference Costs (1999) Performance based supplementary payment (PBSP) 2004 Star rating system (2002 -3) Comparison Similarities: Influence of NPM: liberalisation in terms of market management, performance management and monitoring Ambitious change programmes implemented by strong political power Payment by Results (Pb. R) (2002) Patient Choice (2004) Health Information System (2007) Foundation Trusts (2004) Aim: to Increase quality with better control of resources Attempt to measure performance and reward (but the way of assessment and type of reward are different) Autonomous hospitals (2008) Annual health checks (2004) Cross border health services (2009) Differences: Calculation of organisational performance Two regulators: Care Quality Commission and achievement and differences in majority of Monitor metrics Therefore fund allocation principles are fundamentally different No regulatory institution in for health services: performance management, monitoring, pricing of services all under control of Government

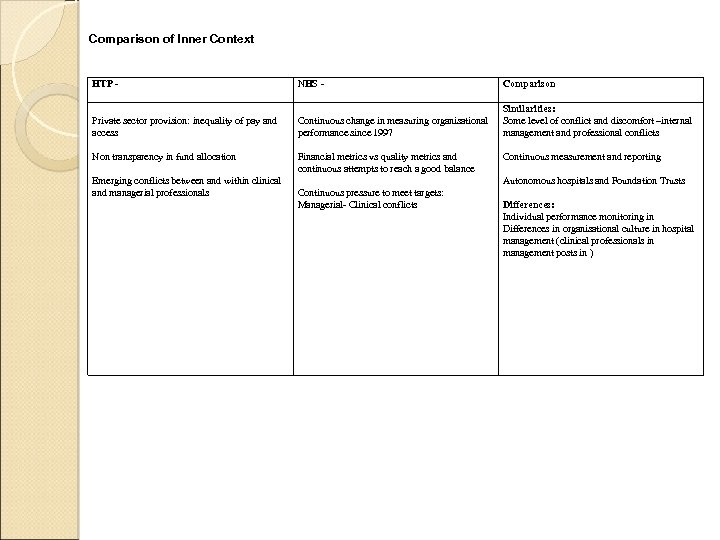

Comparison of Inner Context HTP - NHS - Comparison Private sector provision: inequality of pay and access Continuous change in measuring organisational performance since 1997 Similarities: Some level of conflict and discomfort –internal management and professional conflicts Non transparency in fund allocation Financial metrics vs quality metrics and continuous attempts to reach a good balance Emerging conflicts between and within clinical and managerial professionals Continuous measurement and reporting Autonomous hospitals and Foundation Trusts Continuous pressure to meet targets: Managerial- Clinical conflicts Differences: Individual performance monitoring in Differences in organisational culture in hospital management (clinical professionals in management posts in )

Comparison of Inner Context HTP - NHS - Comparison Private sector provision: inequality of pay and access Continuous change in measuring organisational performance since 1997 Similarities: Some level of conflict and discomfort –internal management and professional conflicts Non transparency in fund allocation Financial metrics vs quality metrics and continuous attempts to reach a good balance Emerging conflicts between and within clinical and managerial professionals Continuous measurement and reporting Autonomous hospitals and Foundation Trusts Continuous pressure to meet targets: Managerial- Clinical conflicts Differences: Individual performance monitoring in Differences in organisational culture in hospital management (clinical professionals in management posts in )

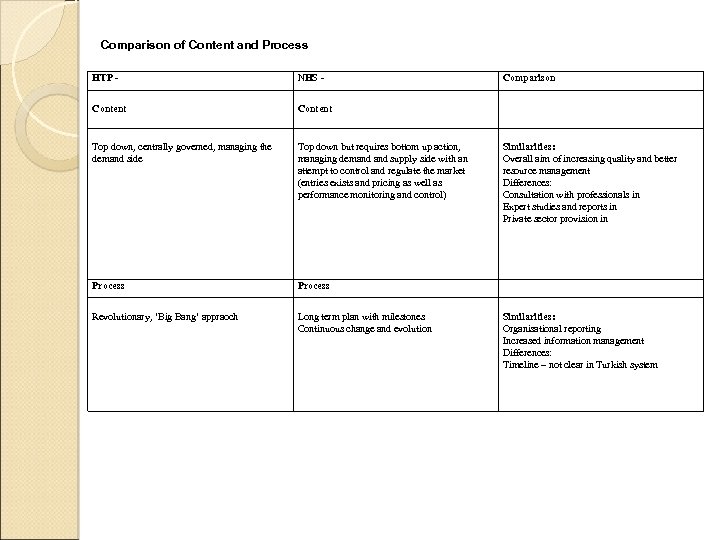

Comparison of Content and Process HTP - NHS - Content Top down, centrally governed, managing the demand side Top down but requires bottom up action, managing demand supply side with an attempt to control and regulate the market (entries exists and pricing as well as performance monitoring and control) Process Revolutionary, ‘Big Bang’ appraoch Long term plan with milestones Continuous change and evolution Comparison Similarities: Overall aim of increasing quality and better resource management Differences: Consultation with professionals in Expert studies and reports in Private sector provision in Similarities: Organisational reporting Increased information management Differences: Timeline – not clear in Turkish system

Comparison of Content and Process HTP - NHS - Content Top down, centrally governed, managing the demand side Top down but requires bottom up action, managing demand supply side with an attempt to control and regulate the market (entries exists and pricing as well as performance monitoring and control) Process Revolutionary, ‘Big Bang’ appraoch Long term plan with milestones Continuous change and evolution Comparison Similarities: Overall aim of increasing quality and better resource management Differences: Consultation with professionals in Expert studies and reports in Private sector provision in Similarities: Organisational reporting Increased information management Differences: Timeline – not clear in Turkish system

Thank you very much

Thank you very much