5622a01c2e8c064fc8b42d5fdb1f3596.ppt

- Количество слайдов: 152

PEDU 6209 Policy Studies in Education Topic 10 Policy Process Studies: Policy Implementation

PEDU 6209 Policy Studies in Education Topic 10 Policy Process Studies: Policy Implementation

(A) The Top-down or Bottom–up Debate

(A) The Top-down or Bottom–up Debate

Theories of Policy Implementation: An Overview z The rational-technical and top-down approach: It indicates theoretical orientations taking implementation as a separate stage of the policy cycle, which is characterized as an enforcement and execution of the state’s policy decision. z The interpretive and bottom-up approach: It summarizes theoretical orientations conceiving implementation as process of interpretations, figuring out what to do and delivering concrete services to program/policy recipients on diverse localities and situations by “street-level bureaucrats” within different organizational setting.

Theories of Policy Implementation: An Overview z The rational-technical and top-down approach: It indicates theoretical orientations taking implementation as a separate stage of the policy cycle, which is characterized as an enforcement and execution of the state’s policy decision. z The interpretive and bottom-up approach: It summarizes theoretical orientations conceiving implementation as process of interpretations, figuring out what to do and delivering concrete services to program/policy recipients on diverse localities and situations by “street-level bureaucrats” within different organizational setting.

Theories of Policy Implementation: An Overview z The top-down and bottom-up synthesis approach: It characterizes theoretical orientations perceiving implementation as process of constituting coalition, structuration, networking, learning or institutionalization, within which various parties in a specific policy domain/area strive to realize a policy, program or project in a context of complexity.

Theories of Policy Implementation: An Overview z The top-down and bottom-up synthesis approach: It characterizes theoretical orientations perceiving implementation as process of constituting coalition, structuration, networking, learning or institutionalization, within which various parties in a specific policy domain/area strive to realize a policy, program or project in a context of complexity.

The Rational-technical and Top-down Approach

The Rational-technical and Top-down Approach

Policy implementation technical control of the execution of decisions from top down z Sabatier and Mazmanian define that “implementation is the carrying out of a basic policy decision. …The implementation process normally runs through a number of stages y beginning with passage of the basic statute, y followed by the policy output (decisions and specifications) of the implementing agencies, y the compliance of the target groups with those decisions, the actual impact – both intended and unintended – of those outputs, y the perceived impacts of agency decisions, and y finally, important revisions (or attempted revision) in the basic status. ” (1995, p. 153; numbering mine)

Policy implementation technical control of the execution of decisions from top down z Sabatier and Mazmanian define that “implementation is the carrying out of a basic policy decision. …The implementation process normally runs through a number of stages y beginning with passage of the basic statute, y followed by the policy output (decisions and specifications) of the implementing agencies, y the compliance of the target groups with those decisions, the actual impact – both intended and unintended – of those outputs, y the perceived impacts of agency decisions, and y finally, important revisions (or attempted revision) in the basic status. ” (1995, p. 153; numbering mine)

Implementation as Control: Enforcement and Execution of Policy Decisions z Accordingly, implementation is perceived as technical problems of control over the internality and externality of the policy, which has been specified by Sabarier and Mazmanian as follows y. Tractability of the problem x Availability of valid technical theory and technology x Diversity of target-group behavior x Target group as percentage of the population x Extent of behavior change required

Implementation as Control: Enforcement and Execution of Policy Decisions z Accordingly, implementation is perceived as technical problems of control over the internality and externality of the policy, which has been specified by Sabarier and Mazmanian as follows y. Tractability of the problem x Availability of valid technical theory and technology x Diversity of target-group behavior x Target group as percentage of the population x Extent of behavior change required

Implementation as Control: Enforcement and Execution of Policy Decisions z …. control over of the internality and externality of the policy, … y. Ability of statute to structure implementation x Clear and consistent objectives x Incorporation of adequate causal theory x Financial resources x Hierarchical integration with and among implementing agency x Recruitment of implementing official x Formal access by outsiders

Implementation as Control: Enforcement and Execution of Policy Decisions z …. control over of the internality and externality of the policy, … y. Ability of statute to structure implementation x Clear and consistent objectives x Incorporation of adequate causal theory x Financial resources x Hierarchical integration with and among implementing agency x Recruitment of implementing official x Formal access by outsiders

Implementation as Control: Enforcement and Execution of Policy Decisions z …. . control over of the internality and externality of the policy…. y. Non-statutory variables affecting implementation x Socioeconomic conditions and technology x Media attention to the problem x Public support x Attitudes and resource of constituency groups x Support from sovereign x Commitment and leadership skill of implementing officials

Implementation as Control: Enforcement and Execution of Policy Decisions z …. . control over of the internality and externality of the policy…. y. Non-statutory variables affecting implementation x Socioeconomic conditions and technology x Media attention to the problem x Public support x Attitudes and resource of constituency groups x Support from sovereign x Commitment and leadership skill of implementing officials

Implementation as Control: Enforcement and Execution of Policy Decisions z Six sufficient and generally necessary conditions for effective implementation y. Clear and consistent objectives y. Adequate causal theory y. Implementation process legally structured to enhance compliance by implementing officials and target groups y. Committed and skillful implementing officials y. Support of interest groups and sovereigns y. Changes in socioeconomic conditions which do not substantially undermine political support or causal theory.

Implementation as Control: Enforcement and Execution of Policy Decisions z Six sufficient and generally necessary conditions for effective implementation y. Clear and consistent objectives y. Adequate causal theory y. Implementation process legally structured to enhance compliance by implementing officials and target groups y. Committed and skillful implementing officials y. Support of interest groups and sovereigns y. Changes in socioeconomic conditions which do not substantially undermine political support or causal theory.

Hierarchy and Market: The Mechanism of Policy Implementation z According to policy analysts of liberal-economic perspective, such as Weimer & Vining (2005), there are two basic mechanisms in coordinating collective action into attaining societal objectives. One is through market mechanism and the other is state intervention. However, Eliot Freidson contends that besides market and state, there is the third logic at work in public policy implementation process in modern society, namely professional power.

Hierarchy and Market: The Mechanism of Policy Implementation z According to policy analysts of liberal-economic perspective, such as Weimer & Vining (2005), there are two basic mechanisms in coordinating collective action into attaining societal objectives. One is through market mechanism and the other is state intervention. However, Eliot Freidson contends that besides market and state, there is the third logic at work in public policy implementation process in modern society, namely professional power.

Hierarchy and Market: The Mechanism of Policy Implementation z Mechanism of policy implementation y Market mechanism: “Collective action enables society to produce, distribute, and consume a great variety and abundance of goods (and services). Most collective action arises from voluntary agreements among people - within families, private organizations and exchange relations. ” (Weimer & Vining, 2005, p. 30) x Individual rational choice: According to the above-cited premise of liberal economic perspective, the basic decision units in collective actions are individual choices. It is further assumed that these basic units will act in accordance with the principles of maximization of utility and profit.

Hierarchy and Market: The Mechanism of Policy Implementation z Mechanism of policy implementation y Market mechanism: “Collective action enables society to produce, distribute, and consume a great variety and abundance of goods (and services). Most collective action arises from voluntary agreements among people - within families, private organizations and exchange relations. ” (Weimer & Vining, 2005, p. 30) x Individual rational choice: According to the above-cited premise of liberal economic perspective, the basic decision units in collective actions are individual choices. It is further assumed that these basic units will act in accordance with the principles of maximization of utility and profit.

Hierarchy and Market: The Mechanism of Policy Implementation y Market mechanism: … x Prefect competitive market: At macroscopic level, these individual rational choices will meet and exchange in a prefect competitive market with the following operational principles/assumptions (Stiglitz & Walsh, 2002, p. 228; and Stiger, 1986; p. 267)) • All participants (Firms and individuals) take market price as given; i. e. numbers of participants are sufficiently large • Actions by individual participants do not directly affect other participants except through price, i. e. they act independently and freely and not collectively; • All participants must possess tolerable or even prefect knowledge of the market opportunities; • Goods are things that only the buyer can enjoy, i. e. they are private goods. They are of the nature – Rivalry in consumption – Excludability in use

Hierarchy and Market: The Mechanism of Policy Implementation y Market mechanism: … x Prefect competitive market: At macroscopic level, these individual rational choices will meet and exchange in a prefect competitive market with the following operational principles/assumptions (Stiglitz & Walsh, 2002, p. 228; and Stiger, 1986; p. 267)) • All participants (Firms and individuals) take market price as given; i. e. numbers of participants are sufficiently large • Actions by individual participants do not directly affect other participants except through price, i. e. they act independently and freely and not collectively; • All participants must possess tolerable or even prefect knowledge of the market opportunities; • Goods are things that only the buyer can enjoy, i. e. they are private goods. They are of the nature – Rivalry in consumption – Excludability in use

Hierarchy and Market: The Mechanism of Policy Implementation z Mechanism of policy implementation y State intervention: State’s interventions into collective actions of production, distribution and consumption in society involve legitimately uses of coercive power in the name of market failure and/or compensating the losers in market. The means employed by the state are commonly called in public policy study the policy instrument. x Conception of policy instrument: “Public policy instruments are the set of techniques by which governmental authorities wield their power in attempting to ensure support and effect or prevent social change. ” (Veding, 1998, p. 21)

Hierarchy and Market: The Mechanism of Policy Implementation z Mechanism of policy implementation y State intervention: State’s interventions into collective actions of production, distribution and consumption in society involve legitimately uses of coercive power in the name of market failure and/or compensating the losers in market. The means employed by the state are commonly called in public policy study the policy instrument. x Conception of policy instrument: “Public policy instruments are the set of techniques by which governmental authorities wield their power in attempting to ensure support and effect or prevent social change. ” (Veding, 1998, p. 21)

Hierarchy and Market: The Mechanism of Policy Implementation y. State intervention: x. Typology of policy instruments • Regulation (Sticks): they are “means undertaken by governmental unit to influence people by means of formulated rules and directives which mandate receivers to action in accordance with what is ordered in these rules and directive. ” (p. 31) • Economic policy instruments (Carrots): They “involve either the handing out or the taking away of material resources, be they in cash or in kind. Economic instruments make it cheaper or more expensive in terms of money, time, effort, and other valuables to pursue certain actions (either compliance or defiance to policy measures). ” (p. 32) • Information (Sermons): They refer “to as ‘moral suasion, ’ or exhortation, covers attempts at influencing people through the transfer of knowledge, the communication of reasoned argument, and persuasion. ” (p. 33)

Hierarchy and Market: The Mechanism of Policy Implementation y. State intervention: x. Typology of policy instruments • Regulation (Sticks): they are “means undertaken by governmental unit to influence people by means of formulated rules and directives which mandate receivers to action in accordance with what is ordered in these rules and directive. ” (p. 31) • Economic policy instruments (Carrots): They “involve either the handing out or the taking away of material resources, be they in cash or in kind. Economic instruments make it cheaper or more expensive in terms of money, time, effort, and other valuables to pursue certain actions (either compliance or defiance to policy measures). ” (p. 32) • Information (Sermons): They refer “to as ‘moral suasion, ’ or exhortation, covers attempts at influencing people through the transfer of knowledge, the communication of reasoned argument, and persuasion. ” (p. 33)

Hierarchy and Market: The Mechanism of Policy Implementation z Mechanism of policy implementation y Professional power: x The third logic in public policy: “For decades now, the popular watchwords driving policy formation (and implementation) have been ‘competition’ and ‘efficiency’, the first referring to competition in a free market, and the second to the benefit of the skilled management of firms (governmental agencies). …I will show in some detail how properties of professionalism fit together to form a whole that differs systematically from the free market on the one hand, and the …bureaucracy, in the other. ” (Freidson, 2001, p. 2 -3) Therefore, Freidson contends that “like Max Weber’s model of rational-legal bureaucracy which represents managerialism and Adam Smith’s model of the free market which represents consumerism” (p. 180), “professionalism is conceived of as one of the three logically distinct methods of organizing and controlling. ” (p. 180)

Hierarchy and Market: The Mechanism of Policy Implementation z Mechanism of policy implementation y Professional power: x The third logic in public policy: “For decades now, the popular watchwords driving policy formation (and implementation) have been ‘competition’ and ‘efficiency’, the first referring to competition in a free market, and the second to the benefit of the skilled management of firms (governmental agencies). …I will show in some detail how properties of professionalism fit together to form a whole that differs systematically from the free market on the one hand, and the …bureaucracy, in the other. ” (Freidson, 2001, p. 2 -3) Therefore, Freidson contends that “like Max Weber’s model of rational-legal bureaucracy which represents managerialism and Adam Smith’s model of the free market which represents consumerism” (p. 180), “professionalism is conceived of as one of the three logically distinct methods of organizing and controlling. ” (p. 180)

Hierarchy and Market: The Mechanism of Policy Implementation z Mechanism of policy implementation y Professional power: x Constituents of Professionalism: “Professionalism is based on specialized bodies of knowledge and skill that have no coercive power of their own but only what may be delegated to them by the state or capital. They gain their protected (and legitimate) status by project of successful persuasion, not by buying it or capturing it at the point of a gun. But because of the special nature of the knowledge and skill imputed to professionals as well as the fact that their practice is protected, friendly commentators have long invoked the need to trust their intention. ” (p. 214) Accordingly the constituents of professionalism may comprise • • Academically respectable knowledge Practically credible skill Socially trustful codes of ethnics and practices Effective authority and autonomy over the above constituents

Hierarchy and Market: The Mechanism of Policy Implementation z Mechanism of policy implementation y Professional power: x Constituents of Professionalism: “Professionalism is based on specialized bodies of knowledge and skill that have no coercive power of their own but only what may be delegated to them by the state or capital. They gain their protected (and legitimate) status by project of successful persuasion, not by buying it or capturing it at the point of a gun. But because of the special nature of the knowledge and skill imputed to professionals as well as the fact that their practice is protected, friendly commentators have long invoked the need to trust their intention. ” (p. 214) Accordingly the constituents of professionalism may comprise • • Academically respectable knowledge Practically credible skill Socially trustful codes of ethnics and practices Effective authority and autonomy over the above constituents

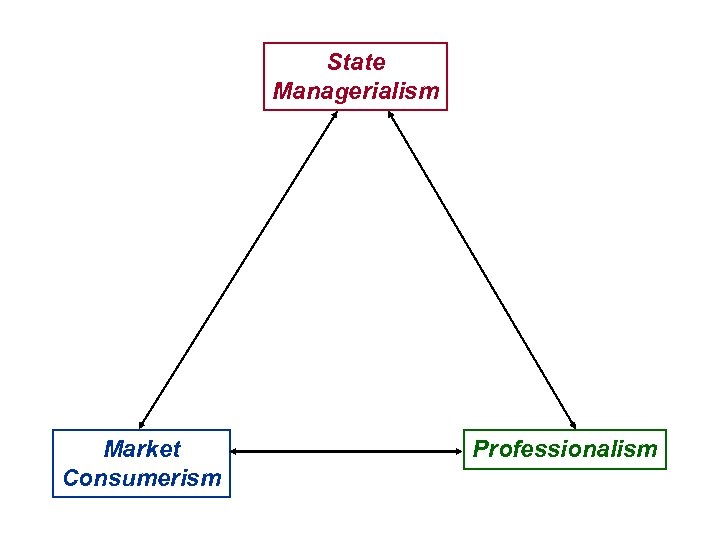

State Managerialism Market Consumerism Professionalism

State Managerialism Market Consumerism Professionalism

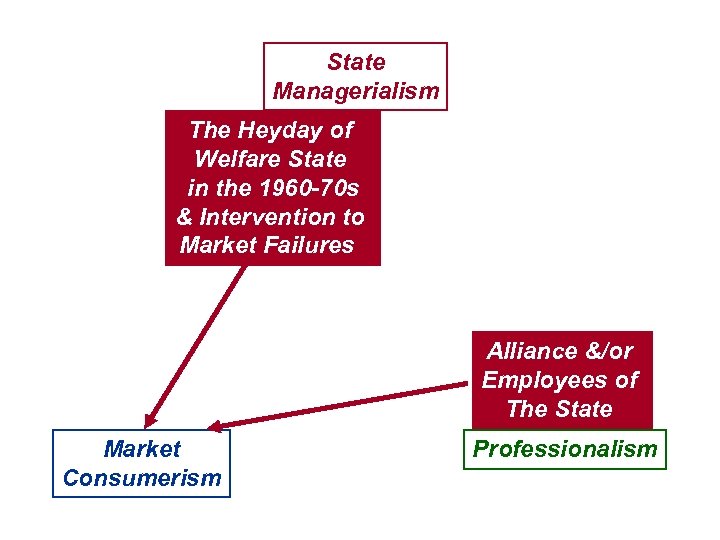

State Managerialism The Heyday of Welfare State in the 1960 -70 s & Intervention to Market Failures Alliance &/or Employees of The State Market Consumerism Professionalism

State Managerialism The Heyday of Welfare State in the 1960 -70 s & Intervention to Market Failures Alliance &/or Employees of The State Market Consumerism Professionalism

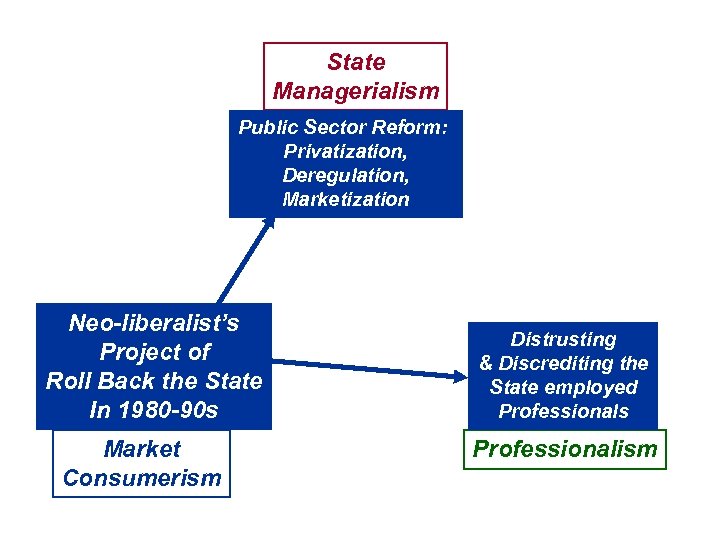

State Managerialism Public Sector Reform: Privatization, Deregulation, Marketization Neo-liberalist’s Project of Roll Back the State In 1980 -90 s Market Consumerism Distrusting & Discrediting the State employed Professionals Professionalism

State Managerialism Public Sector Reform: Privatization, Deregulation, Marketization Neo-liberalist’s Project of Roll Back the State In 1980 -90 s Market Consumerism Distrusting & Discrediting the State employed Professionals Professionalism

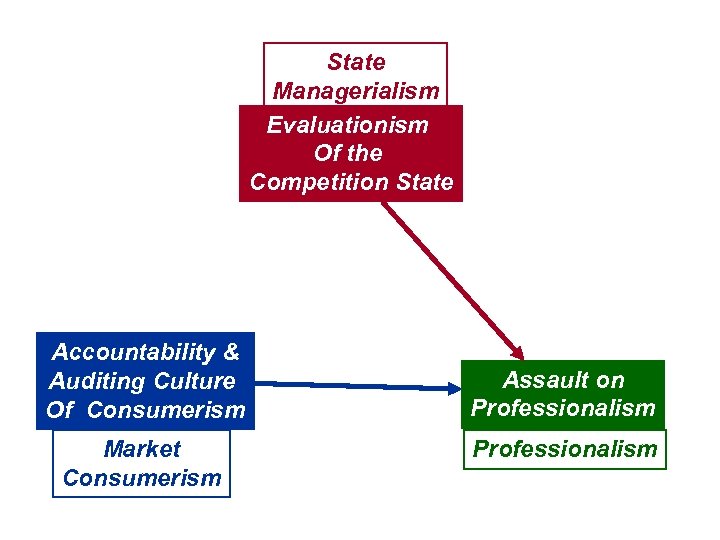

State Managerialism Evaluationism Of the Competition State Accountability & Auditing Culture Of Consumerism Market Consumerism Assault on Professionalism

State Managerialism Evaluationism Of the Competition State Accountability & Auditing Culture Of Consumerism Market Consumerism Assault on Professionalism

The Interpretive & Bottom-up Model

The Interpretive & Bottom-up Model

Michael Lipsky’s street-level bureaucracy model z Lipsky’s book entitled Street-level Bureaucracy (1980) has been viewed as the leading challenge to the topdown model of policy implementation models and the starting point of bottom-up model.

Michael Lipsky’s street-level bureaucracy model z Lipsky’s book entitled Street-level Bureaucracy (1980) has been viewed as the leading challenge to the topdown model of policy implementation models and the starting point of bottom-up model.

Michael Lipsky’s street-level bureaucracy model z Lipsky “argue(s) that public policy is not best understood as made in legislatures or top-floor suites of high ranking administrators, because in important ways it is actually made in the crowded offices and daily encounters in street-level workers. ” And “the street-level bureaucrats, the routines they establish, and the devices they invent to cope with uncertainties and work pressures, effectively become the public policies they carry out. ” (Lipsky, 1993, p. 382) Accordingly, study of education policy implementation should look into teachers’ instructional routines delivered in crowded classrooms and school officials’ policy measures imposed upon teachers and students.

Michael Lipsky’s street-level bureaucracy model z Lipsky “argue(s) that public policy is not best understood as made in legislatures or top-floor suites of high ranking administrators, because in important ways it is actually made in the crowded offices and daily encounters in street-level workers. ” And “the street-level bureaucrats, the routines they establish, and the devices they invent to cope with uncertainties and work pressures, effectively become the public policies they carry out. ” (Lipsky, 1993, p. 382) Accordingly, study of education policy implementation should look into teachers’ instructional routines delivered in crowded classrooms and school officials’ policy measures imposed upon teachers and students.

Michael Lipsky’s street-level bureaucracy model z Lipsky underlines that in implementing policy at street level, front-line worker are confronted with conflict and ambiguities. These may include y. Inadequate resource and unsatisfactory working condition, e. g. large classes for teachers, huge caseloads for social workers, dangerous and hostile neighborhood for police officers. y. Unpredictable, uncooperative, skeptical clients y. Unclear and ambiguous job specification and guidelines.

Michael Lipsky’s street-level bureaucracy model z Lipsky underlines that in implementing policy at street level, front-line worker are confronted with conflict and ambiguities. These may include y. Inadequate resource and unsatisfactory working condition, e. g. large classes for teachers, huge caseloads for social workers, dangerous and hostile neighborhood for police officers. y. Unpredictable, uncooperative, skeptical clients y. Unclear and ambiguous job specification and guidelines.

Michael Lipsky’s street-level bureaucracy model z Confronted with these inadequacies and uncertainties, street-level bureaucrats derive coping strategies or even survival strategies to deal with the unaccommodating working situations. Lipsky point out that in daily “client-processing” routines, street-level bureaucrats in fact have considerable amount of powers and discretions at their disposal, which may lead to substantial deviations from, if not complete alterations of, official and top-down policy specifications.

Michael Lipsky’s street-level bureaucracy model z Confronted with these inadequacies and uncertainties, street-level bureaucrats derive coping strategies or even survival strategies to deal with the unaccommodating working situations. Lipsky point out that in daily “client-processing” routines, street-level bureaucrats in fact have considerable amount of powers and discretions at their disposal, which may lead to substantial deviations from, if not complete alterations of, official and top-down policy specifications.

Michael Lipsky’s street-level bureaucracy model z These discretions or even deviations may take the from of y Modification of client demand: This may include various devices to delay, deter or practically dissolve clients’ demands in overcrowded and overloaded working situations. y Modification of job conception: This may include strategies of lowering the service standards or even alteration of the natures and features of the services supposed to be delivered in order to ease the excessive demands. y Modification of client conception: This may include devices of differentiating clients into non-mandatory categories and to provide different service, e. g. “creaming off” the deserving or educable and “marginalizing” the undeserving and troublemakers

Michael Lipsky’s street-level bureaucracy model z These discretions or even deviations may take the from of y Modification of client demand: This may include various devices to delay, deter or practically dissolve clients’ demands in overcrowded and overloaded working situations. y Modification of job conception: This may include strategies of lowering the service standards or even alteration of the natures and features of the services supposed to be delivered in order to ease the excessive demands. y Modification of client conception: This may include devices of differentiating clients into non-mandatory categories and to provide different service, e. g. “creaming off” the deserving or educable and “marginalizing” the undeserving and troublemakers

Martin Rein’s Down-ward Puzzlement Model Martin Rein (1983) has put forth a theoretical perspective of implementation by questioning the controllability of the implementation policy and injecting the concept of puzzlement and conflict into the study of policy implementation

Martin Rein’s Down-ward Puzzlement Model Martin Rein (1983) has put forth a theoretical perspective of implementation by questioning the controllability of the implementation policy and injecting the concept of puzzlement and conflict into the study of policy implementation

Martin Rein’s down-ward puzzlement model z Rein does not conceptualize the policy implementation process and a clearly defined enforcement process, instead he contends that “Implementation is understood as (1) a declaration of government preferences, (2) mediated by a number of actors, who (3) create a circular process characterized by reciprocal power relations and negotiations, then the actors must take into account three potentially conflicting imperatives: (a) the legal imperative to do what is legally required, (b) the rationalbureaucratic imperative to do what is rationally defensible, and (c) the consensual imperative to do what can help to establish agreement among contending influential parties who have a stake in the outcome. ” (p. 118, the alphabetical numbering is mine)

Martin Rein’s down-ward puzzlement model z Rein does not conceptualize the policy implementation process and a clearly defined enforcement process, instead he contends that “Implementation is understood as (1) a declaration of government preferences, (2) mediated by a number of actors, who (3) create a circular process characterized by reciprocal power relations and negotiations, then the actors must take into account three potentially conflicting imperatives: (a) the legal imperative to do what is legally required, (b) the rationalbureaucratic imperative to do what is rationally defensible, and (c) the consensual imperative to do what can help to establish agreement among contending influential parties who have a stake in the outcome. ” (p. 118, the alphabetical numbering is mine)

Martin Rein’s down-ward puzzlement model z Apart from the three components of the implementation process and the three conflicting imperatives, Rein has further specifies three types of primary actors in the implementation process. They are y guideline developers, y interest groups, and y program administrators

Martin Rein’s down-ward puzzlement model z Apart from the three components of the implementation process and the three conflicting imperatives, Rein has further specifies three types of primary actors in the implementation process. They are y guideline developers, y interest groups, and y program administrators

Martin Rein’s down-ward puzzlement model z In view of such a complicate arena of implementation, Rein underlines that “policy implementation is a matter not only of power but of puzzlement, of ‘men collectively wondering what to do. ’” (p. 117) Such puzzlement is mainly derived from the following scenarios (p. 117) y The program administrators and front-line works “do not know what is required of them (by the legislation or executive policy) since they are asked either to pursue uncertain or evolving goals or reconcile incompatible requirements. ” y “The resources at hand are insufficient for the task. ” y The workers “lack the knowledge and skill (and technology) to take action. ”

Martin Rein’s down-ward puzzlement model z In view of such a complicate arena of implementation, Rein underlines that “policy implementation is a matter not only of power but of puzzlement, of ‘men collectively wondering what to do. ’” (p. 117) Such puzzlement is mainly derived from the following scenarios (p. 117) y The program administrators and front-line works “do not know what is required of them (by the legislation or executive policy) since they are asked either to pursue uncertain or evolving goals or reconcile incompatible requirements. ” y “The resources at hand are insufficient for the task. ” y The workers “lack the knowledge and skill (and technology) to take action. ”

Martin Rein’s down-ward puzzlement model z The downward spiral of puzzlement Rein further specifies that “When the purposes of policy are unclear and incompatible, each successive stage in the process of implementation provides a new context for seeking further clarification. One of the consequences of passing ambiguity an inconsistent legislation is that the arena of decision making shifts to a lower level. The everyday practitioners become the ones who resolve the lack of consensus through their concrete actions. ” (p. 117)

Martin Rein’s down-ward puzzlement model z The downward spiral of puzzlement Rein further specifies that “When the purposes of policy are unclear and incompatible, each successive stage in the process of implementation provides a new context for seeking further clarification. One of the consequences of passing ambiguity an inconsistent legislation is that the arena of decision making shifts to a lower level. The everyday practitioners become the ones who resolve the lack of consensus through their concrete actions. ” (p. 117)

Richard Elmore’s organizational model z Elmore asserts that one of the vital features of policy implementation is “the process by which policies are translated into administrative actions. …(And) the translation of an idea into action involves certain crucial simplification. ” (Elmore, 1993, p. 313)

Richard Elmore’s organizational model z Elmore asserts that one of the vital features of policy implementation is “the process by which policies are translated into administrative actions. …(And) the translation of an idea into action involves certain crucial simplification. ” (Elmore, 1993, p. 313)

Richard Elmore’s organizational model z Elmore further points out that “virtually all public policies are implemented by large public organization. …(And) organizations are simplifiers; they work on problems by breaking them into discrete, manageable tasks and allocating responsibility for those tasks to specialized units. ” (1993, p. 313) In other words, organizations assigned with the task to carry out policies and programs may modify, simplify or even reorientate the policies measures to suit the internal structures and conventional procedures of the organization.

Richard Elmore’s organizational model z Elmore further points out that “virtually all public policies are implemented by large public organization. …(And) organizations are simplifiers; they work on problems by breaking them into discrete, manageable tasks and allocating responsibility for those tasks to specialized units. ” (1993, p. 313) In other words, organizations assigned with the task to carry out policies and programs may modify, simplify or even reorientate the policies measures to suit the internal structures and conventional procedures of the organization.

Richard Elmore’s organizational model z Different organizational models will translate a given policy in different way. They will simplify or “localize” in accordance with their y central principle, y power structure, y decision making procedure, and y implementation process

Richard Elmore’s organizational model z Different organizational models will translate a given policy in different way. They will simplify or “localize” in accordance with their y central principle, y power structure, y decision making procedure, and y implementation process

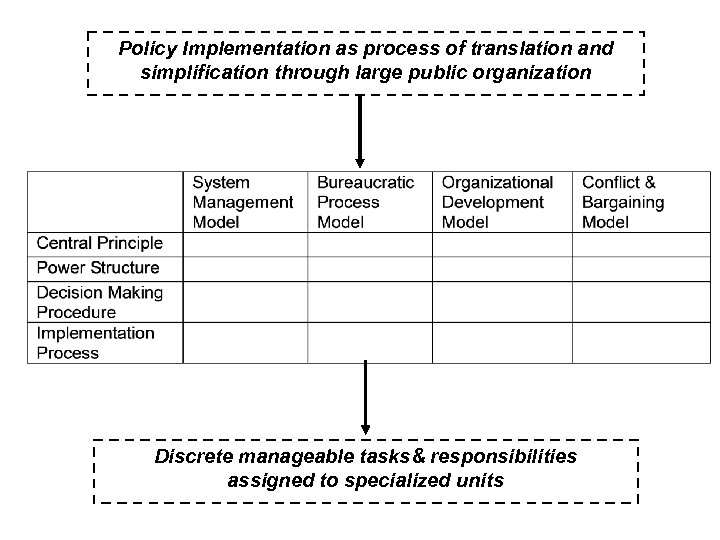

Policy Implementation as process of translation and simplification through large public organization Discrete manageable tasks& responsibilities assigned to specialized units

Policy Implementation as process of translation and simplification through large public organization Discrete manageable tasks& responsibilities assigned to specialized units

(B) Beyond Top and Bottom Dichotomy: The 3 rd Generation of Implementation Theory

(B) Beyond Top and Bottom Dichotomy: The 3 rd Generation of Implementation Theory

Barrett and Fudge's Action-Centered Approach (1981) z Distinction between policy-centered and actioncentered approaches: In reviewing the studies of policy implementation before the 1980 s, Barrett and Fudge classify them into two approaches y Policy-centered approach: This approach takes the policy mandate as the foundation and crux of the implementation process. x. It defines the process of implementation is the logic and administrative lock-steps of "putting the policy into effect". x. The approach accepts the perspectives of the policy makers as the primary concerns and implementation is but the act of carrying out the policy-makers' prescription to the full. x. Accordingly, implementation is construed as a purely administrative task of imposing of control and soliciting compliance

Barrett and Fudge's Action-Centered Approach (1981) z Distinction between policy-centered and actioncentered approaches: In reviewing the studies of policy implementation before the 1980 s, Barrett and Fudge classify them into two approaches y Policy-centered approach: This approach takes the policy mandate as the foundation and crux of the implementation process. x. It defines the process of implementation is the logic and administrative lock-steps of "putting the policy into effect". x. The approach accepts the perspectives of the policy makers as the primary concerns and implementation is but the act of carrying out the policy-makers' prescription to the full. x. Accordingly, implementation is construed as a purely administrative task of imposing of control and soliciting compliance

Barrett and Fudge's Action-Centered Approach (1981) z Distinction between policy-centered and action centered approaches: y Action-centered approach: x It defines policy implementation as series of actions, i. e. a project or an agency, through which "getting something done" or "making something happen" is the primary goal rather than simply securing the compliance of the "street-level bureaucrats" x The approach conceived policy implementation as performance rather than conformance. The performance or action is environment-dependent and context-dependent, hence constraints imposed by the environment as well as perspectives held by interaction partners must be taken into consideration as the implementation process unfolds in the field x According, implementation is conceived as both a negotiating process as well as responsive process

Barrett and Fudge's Action-Centered Approach (1981) z Distinction between policy-centered and action centered approaches: y Action-centered approach: x It defines policy implementation as series of actions, i. e. a project or an agency, through which "getting something done" or "making something happen" is the primary goal rather than simply securing the compliance of the "street-level bureaucrats" x The approach conceived policy implementation as performance rather than conformance. The performance or action is environment-dependent and context-dependent, hence constraints imposed by the environment as well as perspectives held by interaction partners must be taken into consideration as the implementation process unfolds in the field x According, implementation is conceived as both a negotiating process as well as responsive process

Barrett and Fudge's Action-Centered Approach (1981) z Policy implementation as process of structuration y. Susan Barrett specifically underlines the influence of Giddens' Theory of Structuration on her formulation the Policy-Action Model. (2004, p. 256 -257)

Barrett and Fudge's Action-Centered Approach (1981) z Policy implementation as process of structuration y. Susan Barrett specifically underlines the influence of Giddens' Theory of Structuration on her formulation the Policy-Action Model. (2004, p. 256 -257)

Barrett and Fudge's Action-Centered Approach (1981) z Policy implementation as process of structuration y Three conceptual constituents in the Theory of Structuration (Giddens, 1984) x The agency and the agent: • • Agency is conceived as a flow of intentional action, i. e. a project: Agent is defined as knowledgeable human actor, who possesses the capacity of carrying out intentional action x The Structure: Structure refers to those rules and resources, which "make possible for discernibly similar social practices to exist across varying spans of time and space. ' (Giddens, 1984, p. 17) In other words, it refers to "rules and resources recursively implicated in the reproduction of social systems. " (Giddens, 1984, p. 377)

Barrett and Fudge's Action-Centered Approach (1981) z Policy implementation as process of structuration y Three conceptual constituents in the Theory of Structuration (Giddens, 1984) x The agency and the agent: • • Agency is conceived as a flow of intentional action, i. e. a project: Agent is defined as knowledgeable human actor, who possesses the capacity of carrying out intentional action x The Structure: Structure refers to those rules and resources, which "make possible for discernibly similar social practices to exist across varying spans of time and space. ' (Giddens, 1984, p. 17) In other words, it refers to "rules and resources recursively implicated in the reproduction of social systems. " (Giddens, 1984, p. 377)

Barrett and Fudge's Action-Centered Approach (1981) y Three conceptual constituents in the Theory of Structuration x. Structuration: "Analysing the structuration of social systems grounded in the knowledgeable activities of situated actors who draw upon rules and resources in the diversity of action contexts, are produced and reproduced in interaction. …The constitution of agents and structures are not two independently given sets of phenomena, a dualism, but represent a duality. According to the notion duality of structure, the structural properties of social systems are both medium and outcome of the practices they recursively organized. Structure is not 'external' to individuals: as memory traces, and as instantiated in social practices, it is in a sense more 'internal' than exterior to their activities…. Structure is not to be equated with constraint but is always both constraining and enabling. " (P. 25) For example, the structure of a language system both constraints and enable agents, who are knowledgeable to that language, expressing herself and communicating with other agents in daily interactions.

Barrett and Fudge's Action-Centered Approach (1981) y Three conceptual constituents in the Theory of Structuration x. Structuration: "Analysing the structuration of social systems grounded in the knowledgeable activities of situated actors who draw upon rules and resources in the diversity of action contexts, are produced and reproduced in interaction. …The constitution of agents and structures are not two independently given sets of phenomena, a dualism, but represent a duality. According to the notion duality of structure, the structural properties of social systems are both medium and outcome of the practices they recursively organized. Structure is not 'external' to individuals: as memory traces, and as instantiated in social practices, it is in a sense more 'internal' than exterior to their activities…. Structure is not to be equated with constraint but is always both constraining and enabling. " (P. 25) For example, the structure of a language system both constraints and enable agents, who are knowledgeable to that language, expressing herself and communicating with other agents in daily interactions.

Barrett and Fudge's Action-Centered Approach (1981) z Policy implementation as action-and-response process By applying the duality of structure and theory of structuration to the study of policy implementation, policy and its implementation can be reformulated as follows: y Policy can be conceived as a structure, i. e. rules and resources implicating the recurrence of particular sets of social practices. To take EMI policy as an example, it implicates that teachers and students will recursively adopt English as medium of instruction in their lessons. y The duality of the structure can be illustrated by the fact that EMI policy as a structure is both the medium and the outcome of implementation process.

Barrett and Fudge's Action-Centered Approach (1981) z Policy implementation as action-and-response process By applying the duality of structure and theory of structuration to the study of policy implementation, policy and its implementation can be reformulated as follows: y Policy can be conceived as a structure, i. e. rules and resources implicating the recurrence of particular sets of social practices. To take EMI policy as an example, it implicates that teachers and students will recursively adopt English as medium of instruction in their lessons. y The duality of the structure can be illustrated by the fact that EMI policy as a structure is both the medium and the outcome of implementation process.

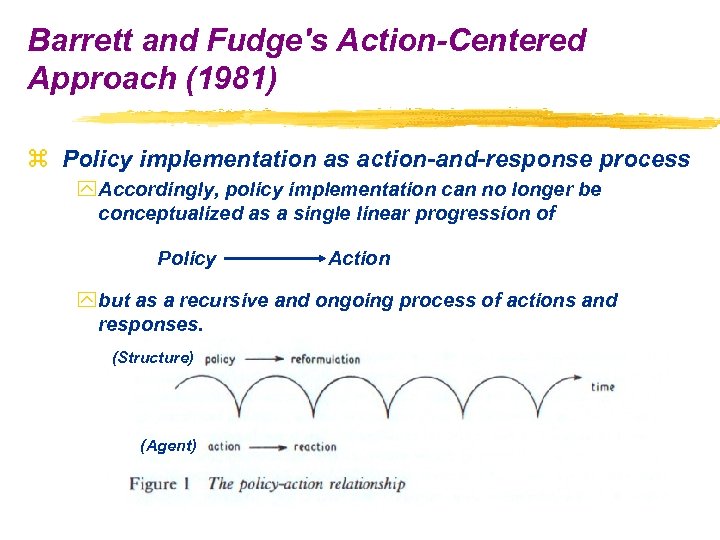

Barrett and Fudge's Action-Centered Approach (1981) z Policy implementation as action-and-response process y Accordingly, policy implementation can no longer be conceptualized as a single linear progression of Policy Action y but as a recursive and ongoing process of actions and responses. (Structure) (Agent)

Barrett and Fudge's Action-Centered Approach (1981) z Policy implementation as action-and-response process y Accordingly, policy implementation can no longer be conceptualized as a single linear progression of Policy Action y but as a recursive and ongoing process of actions and responses. (Structure) (Agent)

S Paul A. Sabatier’s Advocacy Coalition Framework z Sabatier (1986/1993) puts forth the “advocacy coalition framework” as a means to synthesize the top-down and bottom-up models in policy implementation. z By advocacy coalition, Sabatier refers to “actors from various public and private organizations who share a set of beliefs and who seek to realize their common goals over time” in a specific policy system (domain). (Sabatier, 1993, p. 284; and Sabatier and Jenkins. Smith, 1999, p. 120) From this definition, four essential features of advocacy coalition can be deduced.

S Paul A. Sabatier’s Advocacy Coalition Framework z Sabatier (1986/1993) puts forth the “advocacy coalition framework” as a means to synthesize the top-down and bottom-up models in policy implementation. z By advocacy coalition, Sabatier refers to “actors from various public and private organizations who share a set of beliefs and who seek to realize their common goals over time” in a specific policy system (domain). (Sabatier, 1993, p. 284; and Sabatier and Jenkins. Smith, 1999, p. 120) From this definition, four essential features of advocacy coalition can be deduced.

Paul A. Sabatier’s Advocacy Coalition Framework z From this definition, four essential features of advocacy coalition can be deduced. y. The composition of an advocacy coalition is made up of a variety of groupings: (Sabatier and Jenkins-Smith, 1999, p. 118 -119) x x x administrative agencies, legislative committee, interest groups, journalists, researchers, and policy analysts, and actors at all levels of government active in policy formulation and implementation.

Paul A. Sabatier’s Advocacy Coalition Framework z From this definition, four essential features of advocacy coalition can be deduced. y. The composition of an advocacy coalition is made up of a variety of groupings: (Sabatier and Jenkins-Smith, 1999, p. 118 -119) x x x administrative agencies, legislative committee, interest groups, journalists, researchers, and policy analysts, and actors at all levels of government active in policy formulation and implementation.

Paul A. Sabatier’s Advocacy Coalition Framework z From this definition, four essential features of advocacy coalition can be deduced. y. The unit of analysis of policy implementation is neither the top-down officials and their policy directives nor the street-level bureaucrats and their accommodating strategies, but is the advocacy coalitions in a specific policy problem or issue, i. e. policy subsystem, such as higher education or air pollution control. (Sabatier, 1993, 284)

Paul A. Sabatier’s Advocacy Coalition Framework z From this definition, four essential features of advocacy coalition can be deduced. y. The unit of analysis of policy implementation is neither the top-down officials and their policy directives nor the street-level bureaucrats and their accommodating strategies, but is the advocacy coalitions in a specific policy problem or issue, i. e. policy subsystem, such as higher education or air pollution control. (Sabatier, 1993, 284)

Paul A. Sabatier’s Advocacy Coalition Framework z From this definition, four essential features of advocacy coalition can be deduced. y. The delineative line or the integrative force of an advocacy coalition is its belief system, which can be differentiated into three levels. (Sabatier, 1993, p. 287; and Sabatier, 1999, p. 133) x. The deep core: Fundamental normative and ontological axioms x. The policy core: Fundamental policy position concerning the basic strategies for achieving core values within the subsystem x. Instrumental decisions and information searches for necessary to implement policy core

Paul A. Sabatier’s Advocacy Coalition Framework z From this definition, four essential features of advocacy coalition can be deduced. y. The delineative line or the integrative force of an advocacy coalition is its belief system, which can be differentiated into three levels. (Sabatier, 1993, p. 287; and Sabatier, 1999, p. 133) x. The deep core: Fundamental normative and ontological axioms x. The policy core: Fundamental policy position concerning the basic strategies for achieving core values within the subsystem x. Instrumental decisions and information searches for necessary to implement policy core

Paul A. Sabatier’s Advocacy Coalition Framework z From this definition, four essential features of advocacy coalition can be deduced. y. A longer time frame, i. e. a decade or more should be adopted in policy implementation so as to allow the policy process “to complete at least one formulation/implementation/reformulation cycle, to obtain a reasonably accurate portrait of success and failure, and to appreciate the variety of strategies actors pursue over time. ” (Sabatier, 1993, p. 119)

Paul A. Sabatier’s Advocacy Coalition Framework z From this definition, four essential features of advocacy coalition can be deduced. y. A longer time frame, i. e. a decade or more should be adopted in policy implementation so as to allow the policy process “to complete at least one formulation/implementation/reformulation cycle, to obtain a reasonably accurate portrait of success and failure, and to appreciate the variety of strategies actors pursue over time. ” (Sabatier, 1993, p. 119)

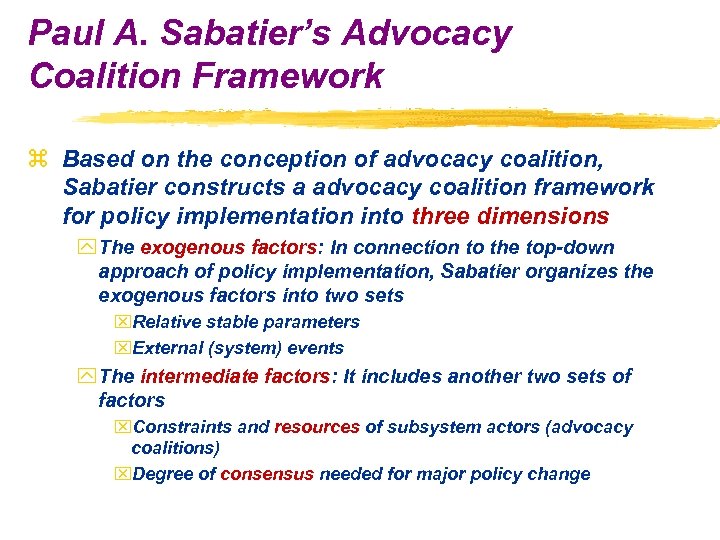

Paul A. Sabatier’s Advocacy Coalition Framework z Based on the conception of advocacy coalition, Sabatier constructs a advocacy coalition framework for policy implementation into three dimensions y The exogenous factors: In connection to the top-down approach of policy implementation, Sabatier organizes the exogenous factors into two sets x. Relative stable parameters x. External (system) events y The intermediate factors: It includes another two sets of factors x. Constraints and resources of subsystem actors (advocacy coalitions) x. Degree of consensus needed for major policy change

Paul A. Sabatier’s Advocacy Coalition Framework z Based on the conception of advocacy coalition, Sabatier constructs a advocacy coalition framework for policy implementation into three dimensions y The exogenous factors: In connection to the top-down approach of policy implementation, Sabatier organizes the exogenous factors into two sets x. Relative stable parameters x. External (system) events y The intermediate factors: It includes another two sets of factors x. Constraints and resources of subsystem actors (advocacy coalitions) x. Degree of consensus needed for major policy change

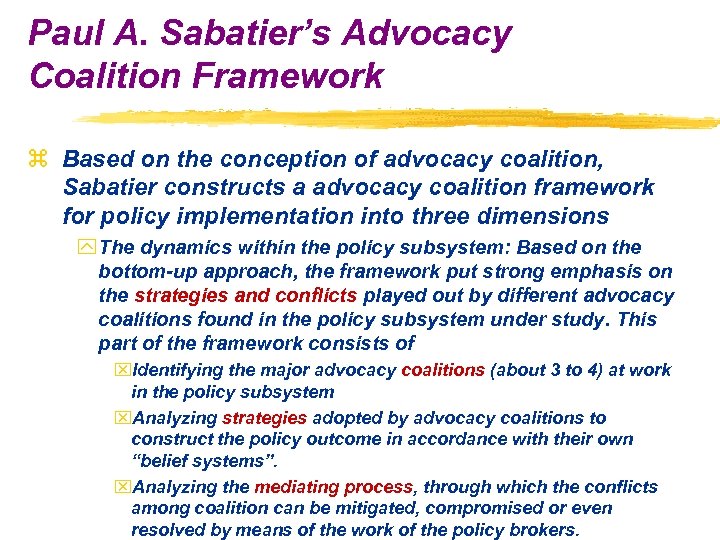

Paul A. Sabatier’s Advocacy Coalition Framework z Based on the conception of advocacy coalition, Sabatier constructs a advocacy coalition framework for policy implementation into three dimensions y The dynamics within the policy subsystem: Based on the bottom-up approach, the framework put strong emphasis on the strategies and conflicts played out by different advocacy coalitions found in the policy subsystem under study. This part of the framework consists of x. Identifying the major advocacy coalitions (about 3 to 4) at work in the policy subsystem x. Analyzing strategies adopted by advocacy coalitions to construct the policy outcome in accordance with their own “belief systems”. x. Analyzing the mediating process, through which the conflicts among coalition can be mitigated, compromised or even resolved by means of the work of the policy brokers.

Paul A. Sabatier’s Advocacy Coalition Framework z Based on the conception of advocacy coalition, Sabatier constructs a advocacy coalition framework for policy implementation into three dimensions y The dynamics within the policy subsystem: Based on the bottom-up approach, the framework put strong emphasis on the strategies and conflicts played out by different advocacy coalitions found in the policy subsystem under study. This part of the framework consists of x. Identifying the major advocacy coalitions (about 3 to 4) at work in the policy subsystem x. Analyzing strategies adopted by advocacy coalitions to construct the policy outcome in accordance with their own “belief systems”. x. Analyzing the mediating process, through which the conflicts among coalition can be mitigated, compromised or even resolved by means of the work of the policy brokers.

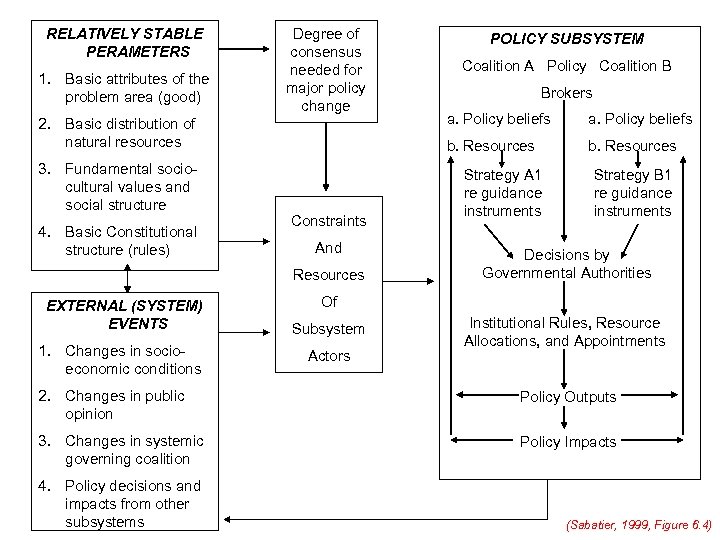

RELATIVELY STABLE PERAMETERS 1. Basic attributes of the problem area (good) Degree of consensus needed for major policy change POLICY SUBSYSTEM Coalition A Policy Coalition B Brokers 2. Basic distribution of natural resources a. Policy beliefs b. Resources 3. Fundamental sociocultural values and social structure Strategy A 1 re guidance instruments 4. Basic Constitutional structure (rules) Constraints And Resources EXTERNAL (SYSTEM) EVENTS 1. Changes in socioeconomic conditions Strategy B 1 re guidance instruments Decisions by Governmental Authorities Of Subsystem Actors Institutional Rules, Resource Allocations, and Appointments 2. Changes in public opinion Policy Outputs 3. Changes in systemic governing coalition Policy Impacts 4. Policy decisions and impacts from other subsystems (Sabatier, 1999, Figure 6. 4)

RELATIVELY STABLE PERAMETERS 1. Basic attributes of the problem area (good) Degree of consensus needed for major policy change POLICY SUBSYSTEM Coalition A Policy Coalition B Brokers 2. Basic distribution of natural resources a. Policy beliefs b. Resources 3. Fundamental sociocultural values and social structure Strategy A 1 re guidance instruments 4. Basic Constitutional structure (rules) Constraints And Resources EXTERNAL (SYSTEM) EVENTS 1. Changes in socioeconomic conditions Strategy B 1 re guidance instruments Decisions by Governmental Authorities Of Subsystem Actors Institutional Rules, Resource Allocations, and Appointments 2. Changes in public opinion Policy Outputs 3. Changes in systemic governing coalition Policy Impacts 4. Policy decisions and impacts from other subsystems (Sabatier, 1999, Figure 6. 4)

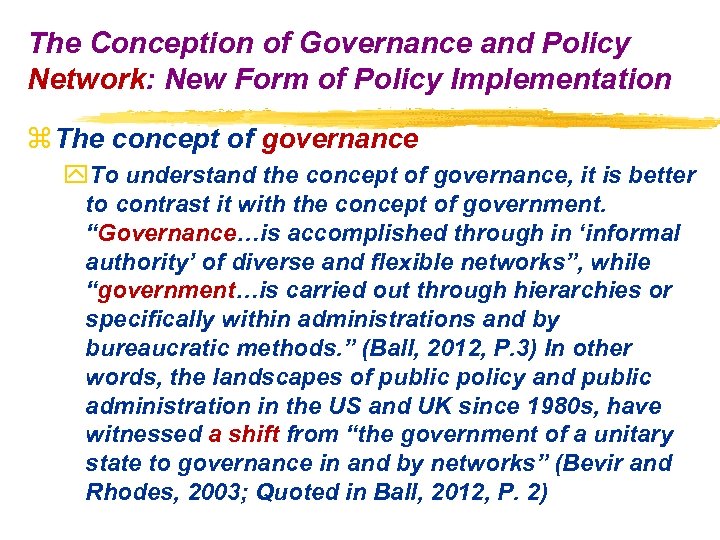

The Conception of Governance and Policy Network: New Form of Policy Implementation z The concept of governance y. To understand the concept of governance, it is better to contrast it with the concept of government. “Governance…is accomplished through in ‘informal authority’ of diverse and flexible networks”, while “government…is carried out through hierarchies or specifically within administrations and by bureaucratic methods. ” (Ball, 2012, P. 3) In other words, the landscapes of public policy and public administration in the US and UK since 1980 s, have witnessed a shift from “the government of a unitary state to governance in and by networks” (Bevir and Rhodes, 2003; Quoted in Ball, 2012, P. 2)

The Conception of Governance and Policy Network: New Form of Policy Implementation z The concept of governance y. To understand the concept of governance, it is better to contrast it with the concept of government. “Governance…is accomplished through in ‘informal authority’ of diverse and flexible networks”, while “government…is carried out through hierarchies or specifically within administrations and by bureaucratic methods. ” (Ball, 2012, P. 3) In other words, the landscapes of public policy and public administration in the US and UK since 1980 s, have witnessed a shift from “the government of a unitary state to governance in and by networks” (Bevir and Rhodes, 2003; Quoted in Ball, 2012, P. 2)

The Conception of Governance and Policy Network: New Form of Policy Implementation z The concept of governance… y. In the field of policy making and implementation, the traditional bureaucratic model, which is characterized by clear and definite rules and regulations, consistent and routine procedures, and well-defined lines of authority and chains of commands, has been replaced to a substantial extent by the model commonly called “policy network. ”

The Conception of Governance and Policy Network: New Form of Policy Implementation z The concept of governance… y. In the field of policy making and implementation, the traditional bureaucratic model, which is characterized by clear and definite rules and regulations, consistent and routine procedures, and well-defined lines of authority and chains of commands, has been replaced to a substantial extent by the model commonly called “policy network. ”

The Conception of Governance and Policy Network: New Form of Policy Implementation z The concept of policy network: To have a comprehensive understanding of the concept of policy network, we can begin with the idea of network logics and its effects on human society.

The Conception of Governance and Policy Network: New Form of Policy Implementation z The concept of policy network: To have a comprehensive understanding of the concept of policy network, we can begin with the idea of network logics and its effects on human society.

The Conception of Governance and Policy Network: New Form of Policy Implementation z The concept of policy network: … y. The constitution of the network logics x “The Atom is the past. The symbol of science for the next century is the dynamical Net … Whereas the Atom represents clean simplicity, the Net channels the messy power of complexity. …The only organization capable of nonprejudiced growth, or unguided learning is a network. All other typologies limited what can happen. A network swarm is all edges and therefore open ended any way you come at it. Indeed, the network is the least structured organization that can be said to have any structure at all. …In fact a plurality of truly divergent components can only remain coherent in a network. No other arrangement – chain, pyramid, tree, circle, hub – can contain ture diversity work as a whole. ” (Kelly, 1995, p. 25 -27 quoted in Castells, 19976, note 71, p. 61 -62)

The Conception of Governance and Policy Network: New Form of Policy Implementation z The concept of policy network: … y. The constitution of the network logics x “The Atom is the past. The symbol of science for the next century is the dynamical Net … Whereas the Atom represents clean simplicity, the Net channels the messy power of complexity. …The only organization capable of nonprejudiced growth, or unguided learning is a network. All other typologies limited what can happen. A network swarm is all edges and therefore open ended any way you come at it. Indeed, the network is the least structured organization that can be said to have any structure at all. …In fact a plurality of truly divergent components can only remain coherent in a network. No other arrangement – chain, pyramid, tree, circle, hub – can contain ture diversity work as a whole. ” (Kelly, 1995, p. 25 -27 quoted in Castells, 19976, note 71, p. 61 -62)

The Conception of Governance and Policy Network: New Form of Policy Implementation z The concept of policy network: … y. The constitution of the network logics… x “Network can now be materially implemented, in all kinds of processes, and organizations, by newly available information technologies. Without them, the networking logic would be too cumbersome to implement. Yet this networking logic is needed to structure the unstructured while preserving flexibaility, since the unstructured is the driving force of innovation in human activity” (Castells, 1996, p. 62)

The Conception of Governance and Policy Network: New Form of Policy Implementation z The concept of policy network: … y. The constitution of the network logics… x “Network can now be materially implemented, in all kinds of processes, and organizations, by newly available information technologies. Without them, the networking logic would be too cumbersome to implement. Yet this networking logic is needed to structure the unstructured while preserving flexibaility, since the unstructured is the driving force of innovation in human activity” (Castells, 1996, p. 62)

The Conception of Governance and Policy Network: New Form of Policy Implementation z The concept of policy network: … y. The definitive features of network: The fluid structure of the network and its IT infrastructure have constituted numbers of features which is novel if not totally foreign to the bureaucratic structure of modern society. x. Flexibility x. Convergence x. Mobility and autonomy

The Conception of Governance and Policy Network: New Form of Policy Implementation z The concept of policy network: … y. The definitive features of network: The fluid structure of the network and its IT infrastructure have constituted numbers of features which is novel if not totally foreign to the bureaucratic structure of modern society. x. Flexibility x. Convergence x. Mobility and autonomy

The Conception of Governance and Policy Network: New Form of Policy Implementation z The concept of policy network: … y. The definitive features of network: … x. Flexibility: By flexibility, it refers to the state of affairs in which “not only processes are reversible, but organizations and institutions can be modified, and even fundamentally altered, by rearrangeing their components. What is distinctive to the configuration of the new technological paradigm is its ability to reconfigure, a decisive feature in a society characterized by constant change and organizational fluidity. …. Flexibility could be a liberating force, but also a repressive tendency if the rewriters of rules are always the powers that be. As Mulgan wrote: ‘Networks are created not just to communicate, but also to gain position, to outcommunicate. ’” (Castells, 1996, p. 62)

The Conception of Governance and Policy Network: New Form of Policy Implementation z The concept of policy network: … y. The definitive features of network: … x. Flexibility: By flexibility, it refers to the state of affairs in which “not only processes are reversible, but organizations and institutions can be modified, and even fundamentally altered, by rearrangeing their components. What is distinctive to the configuration of the new technological paradigm is its ability to reconfigure, a decisive feature in a society characterized by constant change and organizational fluidity. …. Flexibility could be a liberating force, but also a repressive tendency if the rewriters of rules are always the powers that be. As Mulgan wrote: ‘Networks are created not just to communicate, but also to gain position, to outcommunicate. ’” (Castells, 1996, p. 62)

The Conception of Governance and Policy Network: New Form of Policy Implementation z The concept of policy network: … y. The definitive features of network: … x. Convergence: Built on the above-mentioned features of IT network, the network also equips with high degree of compatibility and convergeability, with other systems. x. Mobility and autonomy: As informational technology and mass communication turn from “wired” to “wireless”, they have become much more mobile. IT and communication apparatuses are no longer confined or pinned down to a definite location. As a result, they have allowed their users to liberate from particular physical localities and even social institutions, such as families, workplaces, offices, and schools, etc. (Castell, 2008, Pp 448 -449)

The Conception of Governance and Policy Network: New Form of Policy Implementation z The concept of policy network: … y. The definitive features of network: … x. Convergence: Built on the above-mentioned features of IT network, the network also equips with high degree of compatibility and convergeability, with other systems. x. Mobility and autonomy: As informational technology and mass communication turn from “wired” to “wireless”, they have become much more mobile. IT and communication apparatuses are no longer confined or pinned down to a definite location. As a result, they have allowed their users to liberate from particular physical localities and even social institutions, such as families, workplaces, offices, and schools, etc. (Castell, 2008, Pp 448 -449)

The Conception of Governance and Policy Network: New Form of Policy Implementation z The concept of policy network: … y. According to Castells analysis, two of the essential consequences that the advent of the IT paradigm and network logic brings to bear on human relationship are x. Space of flow x. Timeless time

The Conception of Governance and Policy Network: New Form of Policy Implementation z The concept of policy network: … y. According to Castells analysis, two of the essential consequences that the advent of the IT paradigm and network logic brings to bear on human relationship are x. Space of flow x. Timeless time

The Conception of Governance and Policy Network: New Form of Policy Implementation z The concept of policy network: … y…two of the essential consequences …bear on human relationship x. Space of flow: Brought about by the global-informational infrastructure is the separation of simultaneous social practices from physical contiguity, that is time-sharing social practices are no long embedded in locality of close proximity and/or within finite boundary. As a result, the traditional notion of space of places has been transformed into space of flows. In informational network, such as the internet, "no place exists by itself, since the positions are defined by flows. " There Manuel Castells (1996) underlines that one of the profound features is practically no boundary, no concepts of center or periphery, no beginning or end. It is all but flows.

The Conception of Governance and Policy Network: New Form of Policy Implementation z The concept of policy network: … y…two of the essential consequences …bear on human relationship x. Space of flow: Brought about by the global-informational infrastructure is the separation of simultaneous social practices from physical contiguity, that is time-sharing social practices are no long embedded in locality of close proximity and/or within finite boundary. As a result, the traditional notion of space of places has been transformed into space of flows. In informational network, such as the internet, "no place exists by itself, since the positions are defined by flows. " There Manuel Castells (1996) underlines that one of the profound features is practically no boundary, no concepts of center or periphery, no beginning or end. It is all but flows.

The Conception of Governance and Policy Network: New Form of Policy Implementation z The concept of policy network: … y…two of the essential consequences …bear on human relationship x. Timeless time: Castells also underlines that the global. Informational infrastructure has also transform the conception of time in human society. Time is no longer comprehended in terms of localities around the globe according to the international time-zones. Human activities around the global can be coordinated "simultaneously" in disregard of conception of local time, such as morning, evening, late at night, etc. Furthermore, with the aid of IT, the conventional linear, sequential, diachronic concepts of time has been disturbed. "Timing becoming synchronic inflate horizon, with no beginning, no end, no sequence. " (Castells, 1996, p. 74)

The Conception of Governance and Policy Network: New Form of Policy Implementation z The concept of policy network: … y…two of the essential consequences …bear on human relationship x. Timeless time: Castells also underlines that the global. Informational infrastructure has also transform the conception of time in human society. Time is no longer comprehended in terms of localities around the globe according to the international time-zones. Human activities around the global can be coordinated "simultaneously" in disregard of conception of local time, such as morning, evening, late at night, etc. Furthermore, with the aid of IT, the conventional linear, sequential, diachronic concepts of time has been disturbed. "Timing becoming synchronic inflate horizon, with no beginning, no end, no sequence. " (Castells, 1996, p. 74)

The Conception of Governance and Policy Network: New Form of Policy Implementation z The concept of policy network: … y. The concept of network society: As a result, the modern society that we are so familiar with and used to, i. e. a configuration of social institutions, such as economy, polity, culture, and even social identity, built on definite physical locality and duration in time, has dissolved if not evaporated. In its replacement is a set of social institutions that are organized around the logic of network, namely operated in the flow of space and timeless time.

The Conception of Governance and Policy Network: New Form of Policy Implementation z The concept of policy network: … y. The concept of network society: As a result, the modern society that we are so familiar with and used to, i. e. a configuration of social institutions, such as economy, polity, culture, and even social identity, built on definite physical locality and duration in time, has dissolved if not evaporated. In its replacement is a set of social institutions that are organized around the logic of network, namely operated in the flow of space and timeless time.

The Conception of Governance and Policy Network: New Form of Policy Implementation z The concept of policy network: … y. The concept of policy network: x. By policy network, it refers to non-governmental and/or quasi-governmental organizations, which are independent and autonomous from one another but are connected in terms of resource-exchanges, contracting-in or out, partnership, strategic alliances, etc. They would jointly and collaboratively deliver services and achieve objectives prescribed in public policies. (Ball, 2012, P. 1 -12)

The Conception of Governance and Policy Network: New Form of Policy Implementation z The concept of policy network: … y. The concept of policy network: x. By policy network, it refers to non-governmental and/or quasi-governmental organizations, which are independent and autonomous from one another but are connected in terms of resource-exchanges, contracting-in or out, partnership, strategic alliances, etc. They would jointly and collaboratively deliver services and achieve objectives prescribed in public policies. (Ball, 2012, P. 1 -12)

The Conception of Governance and Policy Network: New Form of Policy Implementation z The concept of policy network: … y. The concept of policy network: … x. It has been conceived that policy network as a form of governance that can be located between the continuum of Hierarchy and Market. As a form of governance, it “is characterized by the plurality of autonomous actors, as they are found within markets, and the capacity to pursue collective goals through deliberately coordinated actions, which is one of the major elements of hierarchy. ” (Raab and Kennis, 2007, 191)

The Conception of Governance and Policy Network: New Form of Policy Implementation z The concept of policy network: … y. The concept of policy network: … x. It has been conceived that policy network as a form of governance that can be located between the continuum of Hierarchy and Market. As a form of governance, it “is characterized by the plurality of autonomous actors, as they are found within markets, and the capacity to pursue collective goals through deliberately coordinated actions, which is one of the major elements of hierarchy. ” (Raab and Kennis, 2007, 191)

The Conception of Governance and Policy Network: New Form of Policy Implementation z The concept of policy network: … y. The network governance and its effects x. The hybrid structure of the network governance: Stephen J. Ball summarizes his study of Networks, New Governance and Education in UK that “what is emerging here is a new hybrid form or mix of networks + bureaucracy + markets that is nonetheless fashioned in the shadow of hierarchy. ” (Ball, 2012, P. 133)

The Conception of Governance and Policy Network: New Form of Policy Implementation z The concept of policy network: … y. The network governance and its effects x. The hybrid structure of the network governance: Stephen J. Ball summarizes his study of Networks, New Governance and Education in UK that “what is emerging here is a new hybrid form or mix of networks + bureaucracy + markets that is nonetheless fashioned in the shadow of hierarchy. ” (Ball, 2012, P. 133)

The Conception of Governance and Policy Network: New Form of Policy Implementation z The concept of policy network: … y. The network governance and its effects … x. The operative principle of the network governance: Ball underlines that working underlying the emerging form of network governance is “the interplay or dialectic of performance management and deconcentration” (Ball, 2012, P. 133) It refers to mechanism of steering (in contrast to rolling) at a distance, such as policy mechanism of output accountability, value for money, quality assurance inspection, performance auditing, etc. “This is the means of ‘governing through governance’―the state becomes a contractor, performance monitor, benchmarker and target setter, engaging in managing. ” Ball, 2012, P. 133) As a result, the role of the in policy delivery has undergone “a shift from ‘directing bureaucracy’ to ‘managing networks’. ” (Ball, 2012, P. 134)

The Conception of Governance and Policy Network: New Form of Policy Implementation z The concept of policy network: … y. The network governance and its effects … x. The operative principle of the network governance: Ball underlines that working underlying the emerging form of network governance is “the interplay or dialectic of performance management and deconcentration” (Ball, 2012, P. 133) It refers to mechanism of steering (in contrast to rolling) at a distance, such as policy mechanism of output accountability, value for money, quality assurance inspection, performance auditing, etc. “This is the means of ‘governing through governance’―the state becomes a contractor, performance monitor, benchmarker and target setter, engaging in managing. ” Ball, 2012, P. 133) As a result, the role of the in policy delivery has undergone “a shift from ‘directing bureaucracy’ to ‘managing networks’. ” (Ball, 2012, P. 134)

The Conception of Governance and Policy Network: New Form of Policy Implementation z The concept of policy network: … y. The network governance and its effects … x. The foundational epistemology of the network governance: Ball points out that emergence from “the mix of market, hierarchies and network” in network governance is a new type of player in policy and service delivery, what he called the “new philanthropy”. By new philanthropy it refers to “the direct relation of ‘giving’ to ‘outcome’ and the direct involvement of givers in philanthropic action and policy community. …This new sensibilities of giving are based upon the increasing use of commercial and enterprise models of practice as a new generic form of philanthropic organization, practice and language. ” (Ball, 2012, P. 49) ….

The Conception of Governance and Policy Network: New Form of Policy Implementation z The concept of policy network: … y. The network governance and its effects … x. The foundational epistemology of the network governance: Ball points out that emergence from “the mix of market, hierarchies and network” in network governance is a new type of player in policy and service delivery, what he called the “new philanthropy”. By new philanthropy it refers to “the direct relation of ‘giving’ to ‘outcome’ and the direct involvement of givers in philanthropic action and policy community. …This new sensibilities of giving are based upon the increasing use of commercial and enterprise models of practice as a new generic form of philanthropic organization, practice and language. ” (Ball, 2012, P. 49) ….

The Conception of Governance and Policy Network: New Form of Policy Implementation z The concept of policy network: … y. The network governance and its effects … x. The foundational epistemology of the network governance: …. As a result, in the domain of network governance, “public sector education, philanthropy and business are increasingly blurred and increasingly convergent in relation to a ‘foundational epistemology’―which is ‘pragmatic entrepreneurialsim’. ” (Ball, 2012, P. 135)

The Conception of Governance and Policy Network: New Form of Policy Implementation z The concept of policy network: … y. The network governance and its effects … x. The foundational epistemology of the network governance: …. As a result, in the domain of network governance, “public sector education, philanthropy and business are increasingly blurred and increasingly convergent in relation to a ‘foundational epistemology’―which is ‘pragmatic entrepreneurialsim’. ” (Ball, 2012, P. 135)

The Conception of Governance and Policy Network: New Form of Policy Implementation z The concept of policy network: … y. The network governance and its effects … x Etho-politics of responsible self-government: Ball further asserts that “new governance is a moral field in a dual sense. (i) There is a bottom-up morality expressed in form of charitable giving and hands-on philanthropy and CSR (corporate social responsibility)―a taking on of responsibility for social problems. …. (ii) There is also a topdown morality expressed and enacted―incitements to responsibility for yourself and others―in forms like volunteering participation in local voluntary association and mutualism. ” (Ball, 2012, P. 135)

The Conception of Governance and Policy Network: New Form of Policy Implementation z The concept of policy network: … y. The network governance and its effects … x Etho-politics of responsible self-government: Ball further asserts that “new governance is a moral field in a dual sense. (i) There is a bottom-up morality expressed in form of charitable giving and hands-on philanthropy and CSR (corporate social responsibility)―a taking on of responsibility for social problems. …. (ii) There is also a topdown morality expressed and enacted―incitements to responsibility for yourself and others―in forms like volunteering participation in local voluntary association and mutualism. ” (Ball, 2012, P. 135)

The Conception of Governance and Policy Network: New Form of Policy Implementation z The concept of policy network: … y. The network governance and its effects … x. Etho-politics of responsible self-government: …. “Together, these commitments and incitements constitute a very particular version of what Rose …calls ‘etho-politics’…. Self-government or mutual government replaces state government: ‘etho-politics concerns itself with selftechniques necessary for responsible self-government. Government, or either governance, acts upon ‘the ethical formation and the ethical self management of individuals’ (Rose, 199, P. 475) as individual take on social responsibilities that were formerly the domain of the state. ” (Ball, 2012, P. 136)

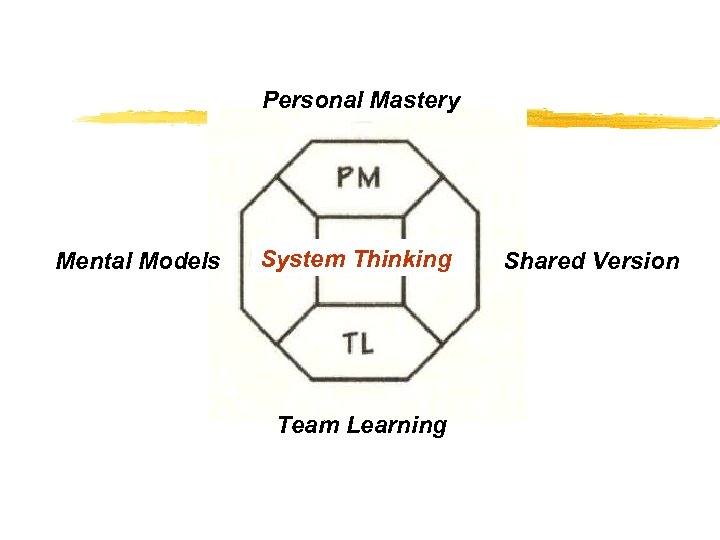

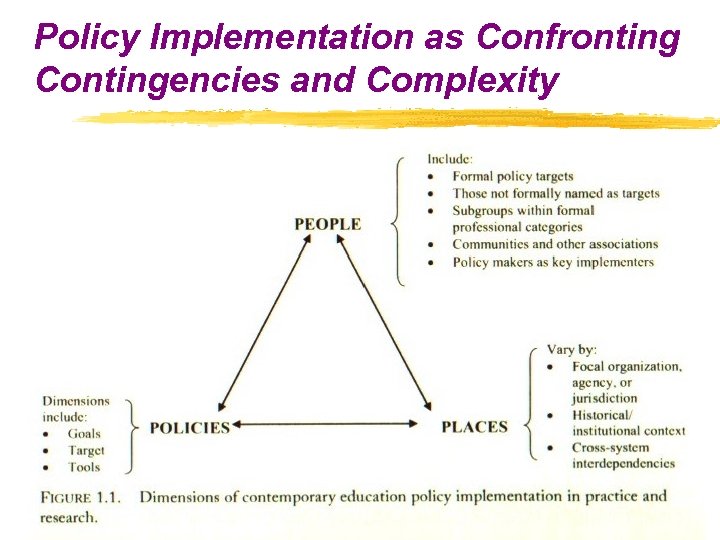

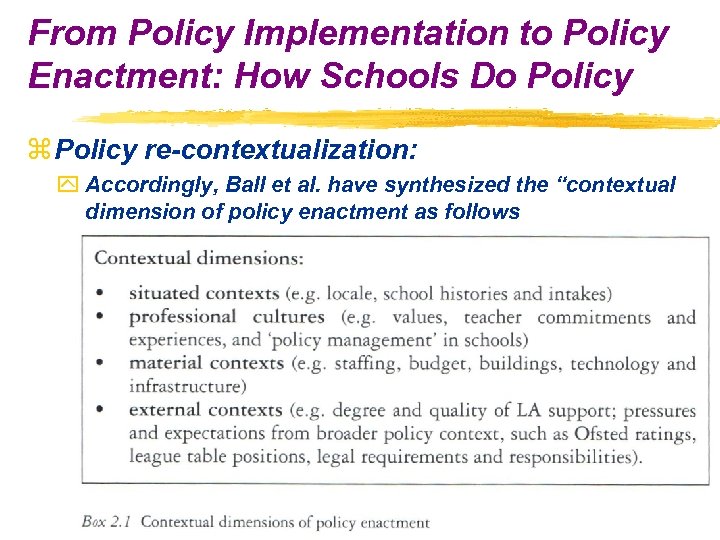

The Conception of Governance and Policy Network: New Form of Policy Implementation z The concept of policy network: … y. The network governance and its effects … x. Etho-politics of responsible self-government: …. “Together, these commitments and incitements constitute a very particular version of what Rose …calls ‘etho-politics’…. Self-government or mutual government replaces state government: ‘etho-politics concerns itself with selftechniques necessary for responsible self-government. Government, or either governance, acts upon ‘the ethical formation and the ethical self management of individuals’ (Rose, 199, P. 475) as individual take on social responsibilities that were formerly the domain of the state. ” (Ball, 2012, P. 136)