Pediatric HSV Epithelial Keratitis W.pptx

- Количество слайдов: 54

Pediartic HSV Epithelial Keratitis

Pediartic HSV Epithelial Keratitis

Herpes simplex virus (HSV) keratitis is an important cause of ocular morbidity that can cause significant vision loss due to its recurring nature. It is caused by the same 2 closely related viruses: herpes simplex virus type 1 (HSV-1) and herpes simplex virus type 2 (HSV-2). HSV -1 is the first member of the human herpes viruses (HHV-1) belonging to the subfamily Alphaherpesviridae. At least 80% of the world’s population has been exposed to HSV-1. Children with HSV keratitis pose a unique challenge to the clinician. The most serious concern in children is that they are susceptible to amblyopia (lazy eye) from corneal scarring that may occur. The virus is transmitted from human to human via secreted fluids and close contact with mucosal surfaces or abraded skin. Initial infection is usually asymptomatic and occurs in children younger than 5 years old. In cases of HSV-2, it is transmitted as the newborn passes through an infected birth canal. Ocular infection may occur directly through droplet spread or indirectly via neuronal spread from a nonocular site such as the oral mucosa.

Herpes simplex virus (HSV) keratitis is an important cause of ocular morbidity that can cause significant vision loss due to its recurring nature. It is caused by the same 2 closely related viruses: herpes simplex virus type 1 (HSV-1) and herpes simplex virus type 2 (HSV-2). HSV -1 is the first member of the human herpes viruses (HHV-1) belonging to the subfamily Alphaherpesviridae. At least 80% of the world’s population has been exposed to HSV-1. Children with HSV keratitis pose a unique challenge to the clinician. The most serious concern in children is that they are susceptible to amblyopia (lazy eye) from corneal scarring that may occur. The virus is transmitted from human to human via secreted fluids and close contact with mucosal surfaces or abraded skin. Initial infection is usually asymptomatic and occurs in children younger than 5 years old. In cases of HSV-2, it is transmitted as the newborn passes through an infected birth canal. Ocular infection may occur directly through droplet spread or indirectly via neuronal spread from a nonocular site such as the oral mucosa.

HSV keratitis occurs when the infection reaches the corneal epithelium and stroma of the cornea. Manifestations can include cutaneous vesicles, blepharitis, conjunctivitis, epithelial keratitis (corneal dendritic ulcers), and stromal keratitis. Nonspecific signs of primary herpetic corneal infection include fever, malaise, and lymphadenopathy. When the virus gains access to the central nervous system, the virus becomes latent in the trigeminal ganglia (HSV-1 or varicella–zoster virus [VZV]) or in the spinal ganglia (HSV-2). Recurrent attacks occur when the virus travels peripherally via sensory nerves to infect target tissues in the eye. These attacks may be triggered by any of the following stressors: fever, ultraviolet light exposure, trauma, stress, menses, and immunosuppression.

HSV keratitis occurs when the infection reaches the corneal epithelium and stroma of the cornea. Manifestations can include cutaneous vesicles, blepharitis, conjunctivitis, epithelial keratitis (corneal dendritic ulcers), and stromal keratitis. Nonspecific signs of primary herpetic corneal infection include fever, malaise, and lymphadenopathy. When the virus gains access to the central nervous system, the virus becomes latent in the trigeminal ganglia (HSV-1 or varicella–zoster virus [VZV]) or in the spinal ganglia (HSV-2). Recurrent attacks occur when the virus travels peripherally via sensory nerves to infect target tissues in the eye. These attacks may be triggered by any of the following stressors: fever, ultraviolet light exposure, trauma, stress, menses, and immunosuppression.

Recurrent ocular HSV-1 infection and inflammation eventually cause corneal scarring, thinning, neovascularization, and stromal keratitis. This disease usually occurs unilaterally, but bilateral infection, although not frequently seen, usually afflicts a younger age group and can be more severe. The corneal dendrites of herpes simplex infections are epithelial ulcers whose edges stain brightly with fluorescein and have terminal bulbs (Figure 19 -1). Herpes zoster dendrites are raised lesions, do not have terminal bulbs, and do not stain well with fluorescein. Some ophthalmic findings of HSV keratitis are not directly caused by the viral infection itself, but instead relate to the immunologic response to the infection, such as chronic keratouveitis (inflammation within the anterior chamber of the eye) and disciform and necrotizing keratitis (cornea is filled with inflammatory cells and has neovascularization despite an intact surface).

Recurrent ocular HSV-1 infection and inflammation eventually cause corneal scarring, thinning, neovascularization, and stromal keratitis. This disease usually occurs unilaterally, but bilateral infection, although not frequently seen, usually afflicts a younger age group and can be more severe. The corneal dendrites of herpes simplex infections are epithelial ulcers whose edges stain brightly with fluorescein and have terminal bulbs (Figure 19 -1). Herpes zoster dendrites are raised lesions, do not have terminal bulbs, and do not stain well with fluorescein. Some ophthalmic findings of HSV keratitis are not directly caused by the viral infection itself, but instead relate to the immunologic response to the infection, such as chronic keratouveitis (inflammation within the anterior chamber of the eye) and disciform and necrotizing keratitis (cornea is filled with inflammatory cells and has neovascularization despite an intact surface).

HSV keratitis in children may differ from that in adults. The rate of bilateral involvement in the largest series of infected children was 10% to 26%, which is higher than seen in adults. The Herpetic Eye Disease Study estimated that both epithelial and stromal keratitis recurred in 18% of patients during a follow-up period of 18 months. Age, sex, ethnicity, and nonocular herpes were not significantly associated with recurrences. However, the Herpetic Eye Disease Study was limited to patients 12 years or older. In different series of pediatric herpetic viral keratitis, recurrence rates ranged from 33% to 80%. Corneal scarring and ulcerations from recurrent herpetic keratitis can be visually debilitating and potentially necessitate surgical intervention with penetrating keratoplasty (corneal transplantation) or tarsorrhaphy (partial lid closure). The inflammatory response from herpetic keratitis leads to stromal scarring and opacification and tends to be more severe in children than adults. For younger children, especially under age 8, the corneal opacity and irregular astigmatism induced by the scars lead to visual deprivation and loss of vision. Even with antiviral therapy, corneal healing can take up to 1 month and will require continued ophthalmic care due to residual corneal scarring and risk of vision loss.

HSV keratitis in children may differ from that in adults. The rate of bilateral involvement in the largest series of infected children was 10% to 26%, which is higher than seen in adults. The Herpetic Eye Disease Study estimated that both epithelial and stromal keratitis recurred in 18% of patients during a follow-up period of 18 months. Age, sex, ethnicity, and nonocular herpes were not significantly associated with recurrences. However, the Herpetic Eye Disease Study was limited to patients 12 years or older. In different series of pediatric herpetic viral keratitis, recurrence rates ranged from 33% to 80%. Corneal scarring and ulcerations from recurrent herpetic keratitis can be visually debilitating and potentially necessitate surgical intervention with penetrating keratoplasty (corneal transplantation) or tarsorrhaphy (partial lid closure). The inflammatory response from herpetic keratitis leads to stromal scarring and opacification and tends to be more severe in children than adults. For younger children, especially under age 8, the corneal opacity and irregular astigmatism induced by the scars lead to visual deprivation and loss of vision. Even with antiviral therapy, corneal healing can take up to 1 month and will require continued ophthalmic care due to residual corneal scarring and risk of vision loss.

HERPES SIMPLEX VIRUS PRIMARY HSV INFECTION Primary HSV ocular infection most commonly manifests as blepharoconjunctivitis (often with conjunctival ulceration) that heals without scarring (Fig. 4 -15 -3). The associated follicular conjunctivitis is often mistaken for adenoviral conjunctivitis (Fig. 4 -15 -4); up to a third of unilateral follicular conjunctivitis may be culture-positive for HSV. 13– 15 Other features include lid vesicles and conjunctival dendrites. Keratitis is rare, occurring in only 3– 5% of cases, though severe bilateral disease can occur in atopic or immunocompromised patients.

HERPES SIMPLEX VIRUS PRIMARY HSV INFECTION Primary HSV ocular infection most commonly manifests as blepharoconjunctivitis (often with conjunctival ulceration) that heals without scarring (Fig. 4 -15 -3). The associated follicular conjunctivitis is often mistaken for adenoviral conjunctivitis (Fig. 4 -15 -4); up to a third of unilateral follicular conjunctivitis may be culture-positive for HSV. 13– 15 Other features include lid vesicles and conjunctival dendrites. Keratitis is rare, occurring in only 3– 5% of cases, though severe bilateral disease can occur in atopic or immunocompromised patients.

RECURRENT HSV INFECTIONS Multiple factors are thought to trigger recurrence, including fever, menses, sunlight, irradiation, and emotional stress. Anecdotal reports have also implicated prostaglandin analogs, immunosuppression, and refractive surgery. Recurrent disease, estimated to occur in 27% of patients at one year and over 60% at 20 years, commonly causes keratitis (HSVK), though it can affect all parts of the eye. 5 HSVK is broadly classifed into epithelial and stromal/endothelial keratitis. This classifcation is not only anatomical but is also important for understanding the pathophysiology of HSVK and for planning treatment.

RECURRENT HSV INFECTIONS Multiple factors are thought to trigger recurrence, including fever, menses, sunlight, irradiation, and emotional stress. Anecdotal reports have also implicated prostaglandin analogs, immunosuppression, and refractive surgery. Recurrent disease, estimated to occur in 27% of patients at one year and over 60% at 20 years, commonly causes keratitis (HSVK), though it can affect all parts of the eye. 5 HSVK is broadly classifed into epithelial and stromal/endothelial keratitis. This classifcation is not only anatomical but is also important for understanding the pathophysiology of HSVK and for planning treatment.

Sunlight, local physical trauma, hormonal changes, and immunological stress (as by fever) are thought to contribute to risk of recurrence of non-ocular herpetic disease [ 9 ]. However, with correction for recall bias, the Herpetic Eye Disease Study (HEDS) Group found that none of these factors were a signifi cant cause of recurrent ocular herpes [ 10 ]. However, a history of atopic disease has been associated with recurrent herpetic eye disease, possibly secondary to immunologic dysfunction [ 11 – 13 ]. Therefore, the practitioner should inquire about personal and family history of conditions such as asthma, eczema, and seasonal allergies.

Sunlight, local physical trauma, hormonal changes, and immunological stress (as by fever) are thought to contribute to risk of recurrence of non-ocular herpetic disease [ 9 ]. However, with correction for recall bias, the Herpetic Eye Disease Study (HEDS) Group found that none of these factors were a signifi cant cause of recurrent ocular herpes [ 10 ]. However, a history of atopic disease has been associated with recurrent herpetic eye disease, possibly secondary to immunologic dysfunction [ 11 – 13 ]. Therefore, the practitioner should inquire about personal and family history of conditions such as asthma, eczema, and seasonal allergies.

Epithelial ulcers may cause sensitivity to light, blurriness, or a foreign body sensation [ 24 ]. In children, photophobia is easily observed [ 26 ]. Pediatric HSV keratitis is typically unilateral; however, atopy and an altered immune system predispose to bilateral disease [ 7 ]. Diagnosis of HSV epithelial keratitis is typically based on clinical fi ndings. Figure 11. 2 shows a typical HSV dendrite. The distinctive appearance and staining pattern of these ulcers are important diagnostic points.

Epithelial ulcers may cause sensitivity to light, blurriness, or a foreign body sensation [ 24 ]. In children, photophobia is easily observed [ 26 ]. Pediatric HSV keratitis is typically unilateral; however, atopy and an altered immune system predispose to bilateral disease [ 7 ]. Diagnosis of HSV epithelial keratitis is typically based on clinical fi ndings. Figure 11. 2 shows a typical HSV dendrite. The distinctive appearance and staining pattern of these ulcers are important diagnostic points.

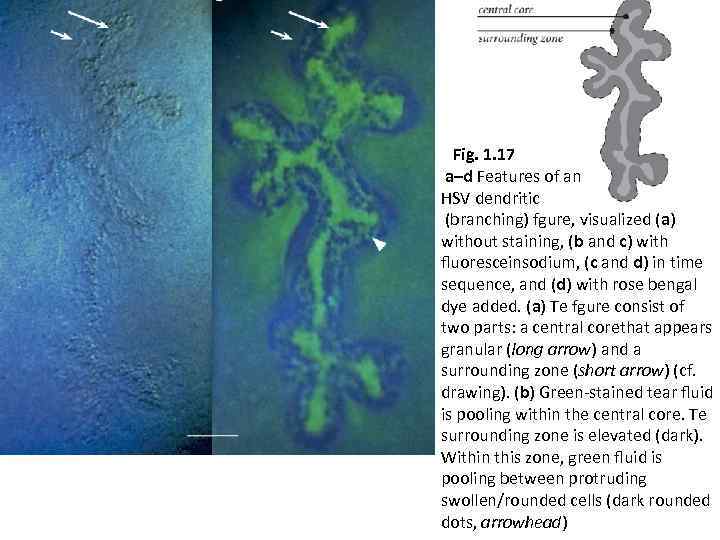

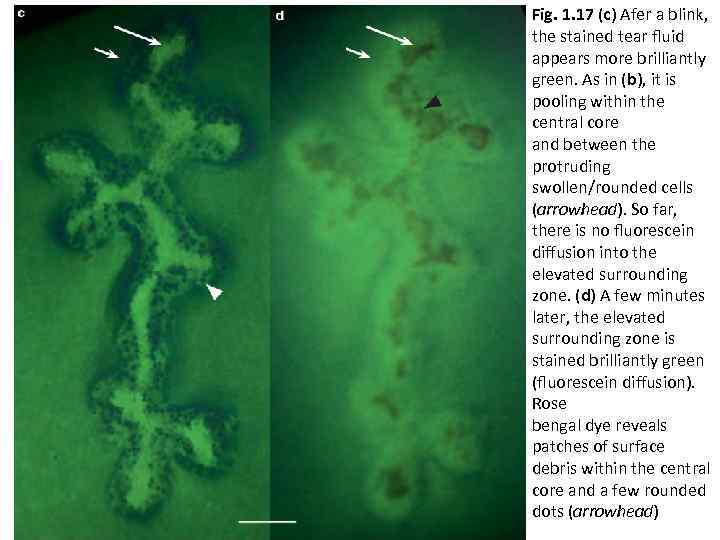

Fig. 1. 17 a–d Features of an HSV dendritic (branching) fgure, visualized (a) without staining, (b and c) with fluoresceinsodium, (c and d) in time sequence, and (d) with rose bengal dye added. (a) Te fgure consist of two parts: a central corethat appears granular (long arrow) and a surrounding zone (short arrow) (cf. drawing). (b) Green-stained tear fluid is pooling within the central core. Te surrounding zone is elevated (dark). Within this zone, green fluid is pooling between protruding swollen/rounded cells (dark rounded dots, arrowhead)

Fig. 1. 17 a–d Features of an HSV dendritic (branching) fgure, visualized (a) without staining, (b and c) with fluoresceinsodium, (c and d) in time sequence, and (d) with rose bengal dye added. (a) Te fgure consist of two parts: a central corethat appears granular (long arrow) and a surrounding zone (short arrow) (cf. drawing). (b) Green-stained tear fluid is pooling within the central core. Te surrounding zone is elevated (dark). Within this zone, green fluid is pooling between protruding swollen/rounded cells (dark rounded dots, arrowhead)

Fig. 1. 17 (c) Afer a blink, the stained tear fluid appears more brilliantly green. As in (b), it is pooling within the central core and between the protruding swollen/rounded cells (arrowhead). So far, there is no fluorescein diffusion into the elevated surrounding zone. (d) A few minutes later, the elevated surrounding zone is stained brilliantly green (fluorescein diffusion). Rose bengal dye reveals patches of surface debris within the central core and a few rounded dots (arrowhead)

Fig. 1. 17 (c) Afer a blink, the stained tear fluid appears more brilliantly green. As in (b), it is pooling within the central core and between the protruding swollen/rounded cells (arrowhead). So far, there is no fluorescein diffusion into the elevated surrounding zone. (d) A few minutes later, the elevated surrounding zone is stained brilliantly green (fluorescein diffusion). Rose bengal dye reveals patches of surface debris within the central core and a few rounded dots (arrowhead)

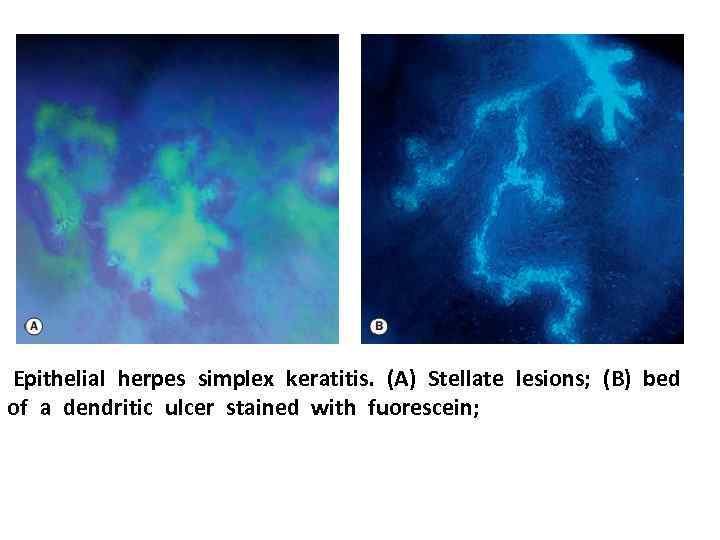

Epithelial herpes simplex keratitis. (A) Stellate lesions; (B) bed of a dendritic ulcer stained with fuorescein;

Epithelial herpes simplex keratitis. (A) Stellate lesions; (B) bed of a dendritic ulcer stained with fuorescein;

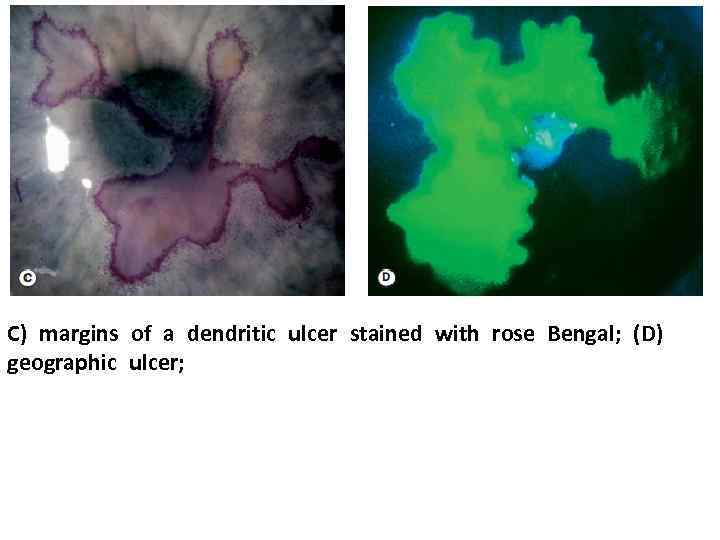

C) margins of a dendritic ulcer stained with rose Bengal; (D) geographic ulcer;

C) margins of a dendritic ulcer stained with rose Bengal; (D) geographic ulcer;

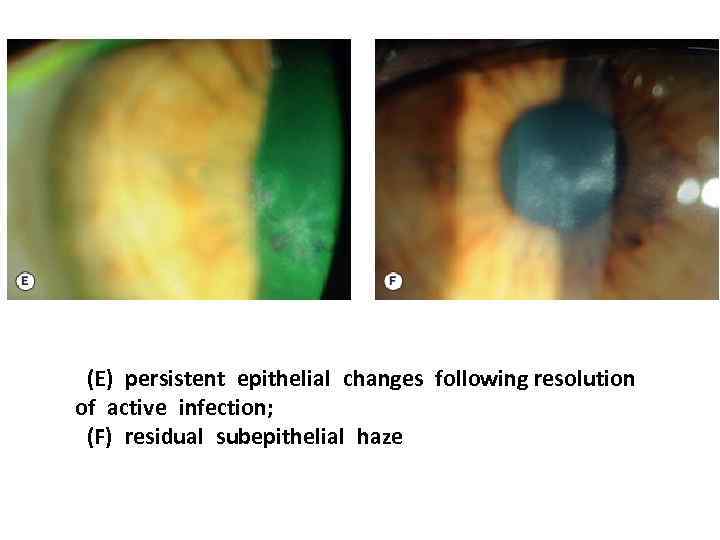

(E) persistent epithelial changes following resolution of active infection; (F) residual subepithelial haze

(E) persistent epithelial changes following resolution of active infection; (F) residual subepithelial haze

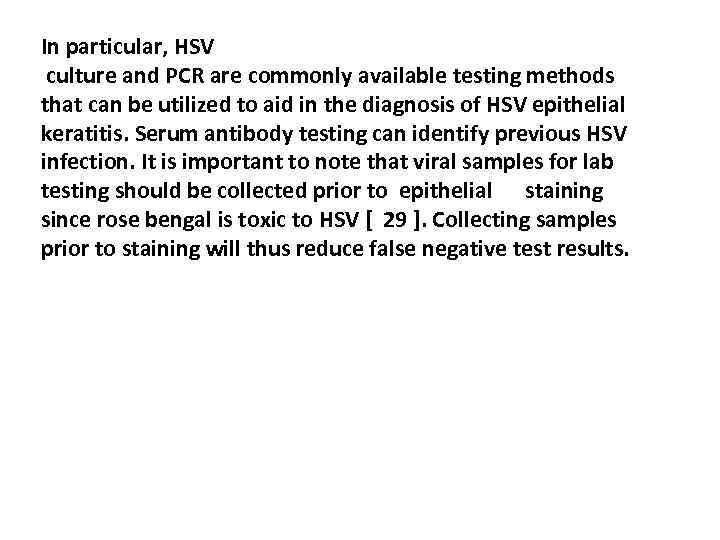

In particular, HSV culture and PCR are commonly available testing methods that can be utilized to aid in the diagnosis of HSV epithelial keratitis. Serum antibody testing can identify previous HSV infection. It is important to note that viral samples for lab testing should be collected prior to epithelial staining since rose bengal is toxic to HSV [ 29 ]. Collecting samples prior to staining will thus reduce false negative test results.

In particular, HSV culture and PCR are commonly available testing methods that can be utilized to aid in the diagnosis of HSV epithelial keratitis. Serum antibody testing can identify previous HSV infection. It is important to note that viral samples for lab testing should be collected prior to epithelial staining since rose bengal is toxic to HSV [ 29 ]. Collecting samples prior to staining will thus reduce false negative test results.

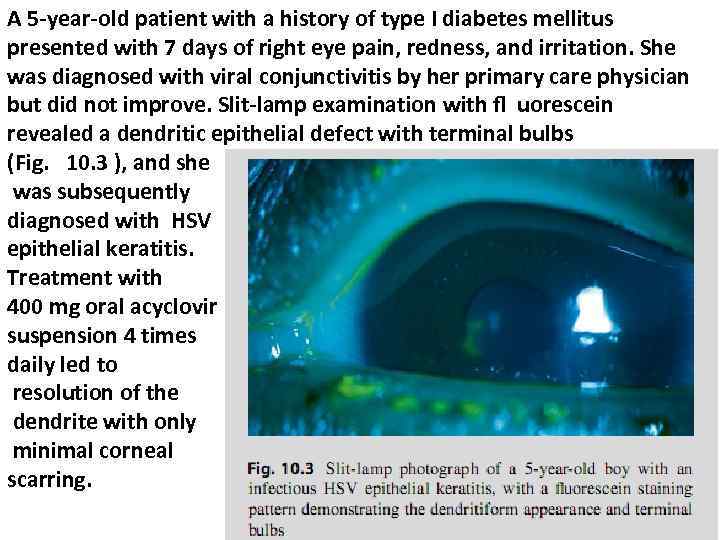

A 5 -year-old patient with a history of type I diabetes mellitus presented with 7 days of right eye pain, redness, and irritation. She was diagnosed with viral conjunctivitis by her primary care physician but did not improve. Slit-lamp examination with fl uorescein revealed a dendritic epithelial defect with terminal bulbs (Fig. 10. 3 ), and she was subsequently diagnosed with HSV epithelial keratitis. Treatment with 400 mg oral acyclovir suspension 4 times daily led to resolution of the dendrite with only minimal corneal scarring.

A 5 -year-old patient with a history of type I diabetes mellitus presented with 7 days of right eye pain, redness, and irritation. She was diagnosed with viral conjunctivitis by her primary care physician but did not improve. Slit-lamp examination with fl uorescein revealed a dendritic epithelial defect with terminal bulbs (Fig. 10. 3 ), and she was subsequently diagnosed with HSV epithelial keratitis. Treatment with 400 mg oral acyclovir suspension 4 times daily led to resolution of the dendrite with only minimal corneal scarring.

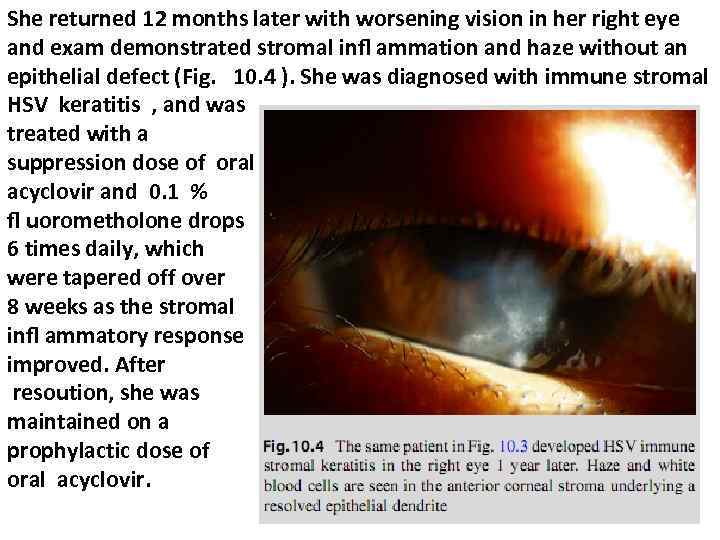

She returned 12 months later with worsening vision in her right eye and exam demonstrated stromal infl ammation and haze without an epithelial defect (Fig. 10. 4 ). She was diagnosed with immune stromal HSV keratitis , and was treated with a suppression dose of oral acyclovir and 0. 1 % fl uorometholone drops 6 times daily, which were tapered off over 8 weeks as the stromal infl ammatory response improved. After resoution, she was maintained on a prophylactic dose of oral acyclovir.

She returned 12 months later with worsening vision in her right eye and exam demonstrated stromal infl ammation and haze without an epithelial defect (Fig. 10. 4 ). She was diagnosed with immune stromal HSV keratitis , and was treated with a suppression dose of oral acyclovir and 0. 1 % fl uorometholone drops 6 times daily, which were tapered off over 8 weeks as the stromal infl ammatory response improved. After resoution, she was maintained on a prophylactic dose of oral acyclovir.

![Although HSV epithelial disease may resolve in some cases without intervention [ 30 ], Although HSV epithelial disease may resolve in some cases without intervention [ 30 ],](https://present5.com/presentation/34750290_453495104/image-31.jpg) Although HSV epithelial disease may resolve in some cases without intervention [ 30 ], medication is utilized to speed resolution, reduce corneal scarring, and diminish stromal infl ammation. Since the epithelial ulcers are caused by actively replicating virus, treatment targets the virus itself. Topical antiviral drugs (trifluridine drops, vidarabine ointment [not currently commercially available], or ganciclovir gel) have been shown to be effective in resolving HSV epithelial keratitis. However, instillation of eye drops in small children may be difficult, and tear dilution from crying could prevent an effective dose. Oral acyclovir thus provides an important adjunctive treatment for pediatric HSV epithelial keratitis, and may provide effective treatment without the use of a topical antiviral [ 21 ]. See Table 11. 1 for acyclovir dosage considerations.

Although HSV epithelial disease may resolve in some cases without intervention [ 30 ], medication is utilized to speed resolution, reduce corneal scarring, and diminish stromal infl ammation. Since the epithelial ulcers are caused by actively replicating virus, treatment targets the virus itself. Topical antiviral drugs (trifluridine drops, vidarabine ointment [not currently commercially available], or ganciclovir gel) have been shown to be effective in resolving HSV epithelial keratitis. However, instillation of eye drops in small children may be difficult, and tear dilution from crying could prevent an effective dose. Oral acyclovir thus provides an important adjunctive treatment for pediatric HSV epithelial keratitis, and may provide effective treatment without the use of a topical antiviral [ 21 ]. See Table 11. 1 for acyclovir dosage considerations.

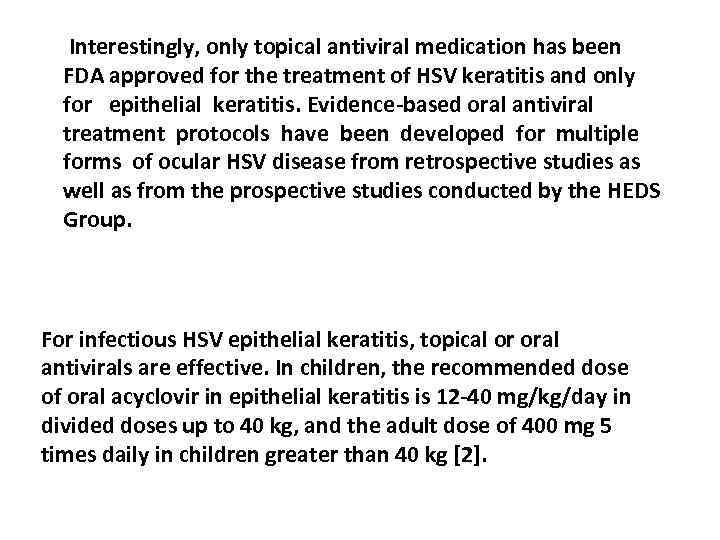

Interestingly, only topical antiviral medication has been FDA approved for the treatment of HSV keratitis and only for epithelial keratitis. Evidence-based oral antiviral treatment protocols have been developed for multiple forms of ocular HSV disease from retrospective studies as well as from the prospective studies conducted by the HEDS Group. For infectious HSV epithelial keratitis, topical or oral antivirals are effective. In children, the recommended dose of oral acyclovir in epithelial keratitis is 12 -40 mg/kg/day in divided doses up to 40 kg, and the adult dose of 400 mg 5 times daily in children greater than 40 kg [2].

Interestingly, only topical antiviral medication has been FDA approved for the treatment of HSV keratitis and only for epithelial keratitis. Evidence-based oral antiviral treatment protocols have been developed for multiple forms of ocular HSV disease from retrospective studies as well as from the prospective studies conducted by the HEDS Group. For infectious HSV epithelial keratitis, topical or oral antivirals are effective. In children, the recommended dose of oral acyclovir in epithelial keratitis is 12 -40 mg/kg/day in divided doses up to 40 kg, and the adult dose of 400 mg 5 times daily in children greater than 40 kg [2].

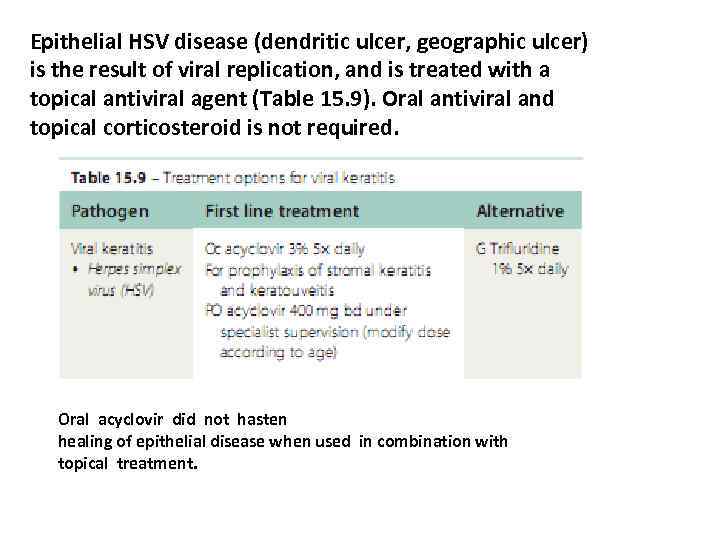

Epithelial HSV disease (dendritic ulcer, geographic ulcer) is the result of viral replication, and is treated with a topical antiviral agent (Table 15. 9). Oral antiviral and topical corticosteroid is not required. Oral acyclovir did not hasten healing of epithelial disease when used in combination with topical treatment.

Epithelial HSV disease (dendritic ulcer, geographic ulcer) is the result of viral replication, and is treated with a topical antiviral agent (Table 15. 9). Oral antiviral and topical corticosteroid is not required. Oral acyclovir did not hasten healing of epithelial disease when used in combination with topical treatment.

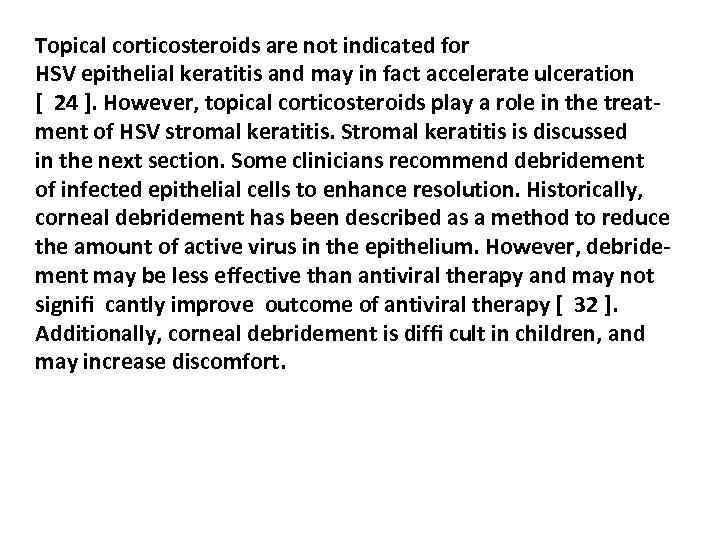

Topical corticosteroids are not indicated for HSV epithelial keratitis and may in fact accelerate ulceration [ 24 ]. However, topical corticosteroids play a role in the treatment of HSV stromal keratitis. Stromal keratitis is discussed in the next section. Some clinicians recommend debridement of infected epithelial cells to enhance resolution. Historically, corneal debridement has been described as a method to reduce the amount of active virus in the epithelium. However, debridement may be less effective than antiviral therapy and may not signifi cantly improve outcome of antiviral therapy [ 32 ]. Additionally, corneal debridement is diffi cult in children, and may increase discomfort.

Topical corticosteroids are not indicated for HSV epithelial keratitis and may in fact accelerate ulceration [ 24 ]. However, topical corticosteroids play a role in the treatment of HSV stromal keratitis. Stromal keratitis is discussed in the next section. Some clinicians recommend debridement of infected epithelial cells to enhance resolution. Historically, corneal debridement has been described as a method to reduce the amount of active virus in the epithelium. However, debridement may be less effective than antiviral therapy and may not signifi cantly improve outcome of antiviral therapy [ 32 ]. Additionally, corneal debridement is diffi cult in children, and may increase discomfort.

Unfortunately, as described in the introduction, HSV epithelial keratitis can recur. After an epithelial ulcer resolves, a faint stromal scar may remain. Recurrent HSV dendritic ulcers may recur near the scar. Epithelial recurrences increase the risk of HSV stromal keratitis, an immune-mediated disease process. Recurrence of HSV keratitis is higher in children and is a major management concern [ 21 ]. Thus, monitoring of children with periodic follow-up examinations and educating the parents for signs of recurrence are essential.

Unfortunately, as described in the introduction, HSV epithelial keratitis can recur. After an epithelial ulcer resolves, a faint stromal scar may remain. Recurrent HSV dendritic ulcers may recur near the scar. Epithelial recurrences increase the risk of HSV stromal keratitis, an immune-mediated disease process. Recurrence of HSV keratitis is higher in children and is a major management concern [ 21 ]. Thus, monitoring of children with periodic follow-up examinations and educating the parents for signs of recurrence are essential.

HSV stromal keratitis classically involves an immunemediated response to inactive HSV antigen in the corneal stroma [ 6 ]. However, complex presentations with mixed patterns of anterior corneal disease and corneal scarring from multiple recurrences are possible [ 24 ]. Simple HSV stromal keratitis may present with single or multifocal sub-epithelial infl ammatory infi ltrates.

HSV stromal keratitis classically involves an immunemediated response to inactive HSV antigen in the corneal stroma [ 6 ]. However, complex presentations with mixed patterns of anterior corneal disease and corneal scarring from multiple recurrences are possible [ 24 ]. Simple HSV stromal keratitis may present with single or multifocal sub-epithelial infl ammatory infi ltrates.

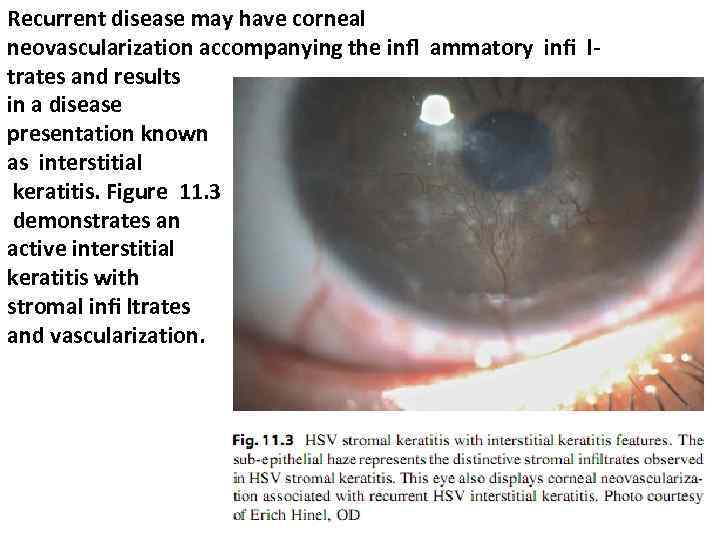

Recurrent disease may have corneal neovascularization accompanying the infl ammatory infi ltrates and results in a disease presentation known as interstitial keratitis. Figure 11. 3 demonstrates an active interstitial keratitis with stromal infi ltrates and vascularization.

Recurrent disease may have corneal neovascularization accompanying the infl ammatory infi ltrates and results in a disease presentation known as interstitial keratitis. Figure 11. 3 demonstrates an active interstitial keratitis with stromal infi ltrates and vascularization.

Treatment of stromal keratitis in children typically involves the use of topical corticosteroids and oral antivirals. The topical corticosteroid is necessary to treat the stromal infl ammation, and the oral antiviral treats any active viral disease in addition to a putative contribution in preventing recurrence

Treatment of stromal keratitis in children typically involves the use of topical corticosteroids and oral antivirals. The topical corticosteroid is necessary to treat the stromal infl ammation, and the oral antiviral treats any active viral disease in addition to a putative contribution in preventing recurrence

The topical corticosteroid may be tapered and the oral antiviral discontinued after the fi rst episode. However, longitudinal treatment throughout the amblyogenic period may be required to prevent visually debilitating scarring in the visual axis and resultant amblyopia. Corticosteroid should be tapered to the minimum amount necessary to control infl ammation.

The topical corticosteroid may be tapered and the oral antiviral discontinued after the fi rst episode. However, longitudinal treatment throughout the amblyogenic period may be required to prevent visually debilitating scarring in the visual axis and resultant amblyopia. Corticosteroid should be tapered to the minimum amount necessary to control infl ammation.

Valacyclovir may be considered for older teenage patients with HSV stromal keratitis since it has been FDA approved for long-term treatment (at the 1 g/day suppressive therapy dose for genital herpes) [ 33 ]. Valacyclovir is a pro-drug of acyclovir that has an ester moiety that is removed by esterases to result in the active acyclovir. As a pro-drug of acyclovir, valacyclovir has greater bioavailability and would theoretically be expected to have a similar side effect profi le. Famciclovir has also been approved for longterm suppressive therapy of genital herpes (at 250 mg twice a day), so it may also be considered for HSV stromal keratitis in older teenage patients [ 34 ]. However, famciclovir is not FDA approved for children.

Valacyclovir may be considered for older teenage patients with HSV stromal keratitis since it has been FDA approved for long-term treatment (at the 1 g/day suppressive therapy dose for genital herpes) [ 33 ]. Valacyclovir is a pro-drug of acyclovir that has an ester moiety that is removed by esterases to result in the active acyclovir. As a pro-drug of acyclovir, valacyclovir has greater bioavailability and would theoretically be expected to have a similar side effect profi le. Famciclovir has also been approved for longterm suppressive therapy of genital herpes (at 250 mg twice a day), so it may also be considered for HSV stromal keratitis in older teenage patients [ 34 ]. However, famciclovir is not FDA approved for children.

Epithelial keratitis later followed by stromal keratitis or concomitant epithelial disease. In cases with concomitant epithelial disease, topical treatment is generally added for the fi rst 2 weeks.

Epithelial keratitis later followed by stromal keratitis or concomitant epithelial disease. In cases with concomitant epithelial disease, topical treatment is generally added for the fi rst 2 weeks.

The Herpes Eye Disease Study Group treatment guidelines are as follows: • For stromal disease (e. g. disciform keratitis), topical steroid (1% prednisolone phosphate four times daily), in conjunction with topical antiviral cover, reduces recovery time by 68% with no increased risk of recurrence at 6 months. • There is no additional effect of oral acyclovir over topical steroid and F 3 T when treating stromal keratitis. • After epithelial HSV a 3 -week course of oral acyclovir (400 mg 5 times a day) does not prevent stromal disease in the subsequent year. • Prophylactic treatment with acyclovir (400 mg bd) reduces epithelial recurrences and stromal recurrences in patients with prior stromal disease by about 50% over 12 months. Prophylactic treatment is usually restricted to patients with bilateral disease, prior HSV keratitis in atopes, or the immunosuppressed, especially following corneal surgery.

The Herpes Eye Disease Study Group treatment guidelines are as follows: • For stromal disease (e. g. disciform keratitis), topical steroid (1% prednisolone phosphate four times daily), in conjunction with topical antiviral cover, reduces recovery time by 68% with no increased risk of recurrence at 6 months. • There is no additional effect of oral acyclovir over topical steroid and F 3 T when treating stromal keratitis. • After epithelial HSV a 3 -week course of oral acyclovir (400 mg 5 times a day) does not prevent stromal disease in the subsequent year. • Prophylactic treatment with acyclovir (400 mg bd) reduces epithelial recurrences and stromal recurrences in patients with prior stromal disease by about 50% over 12 months. Prophylactic treatment is usually restricted to patients with bilateral disease, prior HSV keratitis in atopes, or the immunosuppressed, especially following corneal surgery.

Typical features of a neonatal HSV infection include localized external lesions (skin, eye, and/or mouth), disseminated herpes affecting internal organs, and central nervous system infection (encephalitis). An infected infant may display several of these features. Ocular herpes in the newborn typically appears as periorbital skin vesicles, blepharoconjunctivitis, keratitis, anterior uveitis, chorioretinitis, and congenital cataracts [ 3 , 39 ]. Importantly, a dilated fundus examination should be performed in any neonate with suspected HSV infection. Since herpes infections may resemble other neonatal infections, laboratory tests (e. g. , fl uorescein antibody tests, herpes culture, or PCR testing) should be performed in all cases of suspected neonatal herpes [ 28 ]. While awaiting lab results, the newborn should be empirically treated with intravenous acyclovir.

Typical features of a neonatal HSV infection include localized external lesions (skin, eye, and/or mouth), disseminated herpes affecting internal organs, and central nervous system infection (encephalitis). An infected infant may display several of these features. Ocular herpes in the newborn typically appears as periorbital skin vesicles, blepharoconjunctivitis, keratitis, anterior uveitis, chorioretinitis, and congenital cataracts [ 3 , 39 ]. Importantly, a dilated fundus examination should be performed in any neonate with suspected HSV infection. Since herpes infections may resemble other neonatal infections, laboratory tests (e. g. , fl uorescein antibody tests, herpes culture, or PCR testing) should be performed in all cases of suspected neonatal herpes [ 28 ]. While awaiting lab results, the newborn should be empirically treated with intravenous acyclovir.

Overall prognosis of neonatal ocular HSV infection treated with intravenous antiviral therapy is generally good. However, mortality is higher in newborns with disseminated infection or CNS disease [ 28 ]. Visual outcome is poorer when corneal herpetic disease causes scarring. Infants must also be monitored closely for evidence of recurrent disease. Infants with recurrent HSV keratitis are typically followed longitudinally by an infectious disease specialist. Additionally, longitudinal follow-up by a pediatric ophthalmologist is important due to the risk of amblyopia development associated with recurrent HSV keratitis. If there is recurrent neonatal ocular HSV infection, higher oral doses of acyclovir may be necessary.

Overall prognosis of neonatal ocular HSV infection treated with intravenous antiviral therapy is generally good. However, mortality is higher in newborns with disseminated infection or CNS disease [ 28 ]. Visual outcome is poorer when corneal herpetic disease causes scarring. Infants must also be monitored closely for evidence of recurrent disease. Infants with recurrent HSV keratitis are typically followed longitudinally by an infectious disease specialist. Additionally, longitudinal follow-up by a pediatric ophthalmologist is important due to the risk of amblyopia development associated with recurrent HSV keratitis. If there is recurrent neonatal ocular HSV infection, higher oral doses of acyclovir may be necessary.