bd5f20cf24800325824c32beffa41f07.ppt

- Количество слайдов: 80

Part VIII. Networks, standards and systems Chapter 20. Markets with network goods Slides Industrial Organization: Markets and Strategies Paul Belleflamme and Martin Peitz © Cambridge University Press 2009

Part VIII. Networks, standards and systems Chapter 20. Markets with network goods Slides Industrial Organization: Markets and Strategies Paul Belleflamme and Martin Peitz © Cambridge University Press 2009

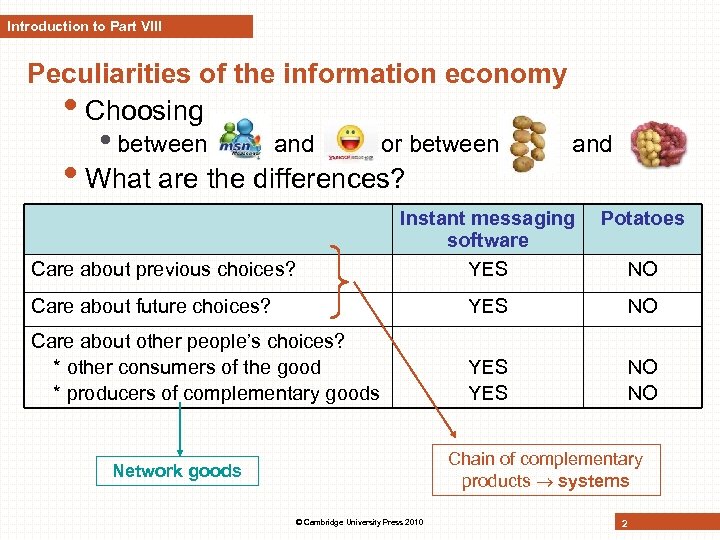

Introduction to Part VIII Peculiarities of the information economy • Choosing • between and or between • What are the differences? and Instant messaging software YES Potatoes Care about future choices? YES NO Care about other people’s choices? * other consumers of the good * producers of complementary goods YES NO NO Care about previous choices? NO Chain of complementary products systems Network goods © Cambridge University Press 2010 2

Introduction to Part VIII Peculiarities of the information economy • Choosing • between and or between • What are the differences? and Instant messaging software YES Potatoes Care about future choices? YES NO Care about other people’s choices? * other consumers of the good * producers of complementary goods YES NO NO Care about previous choices? NO Chain of complementary products systems Network goods © Cambridge University Press 2010 2

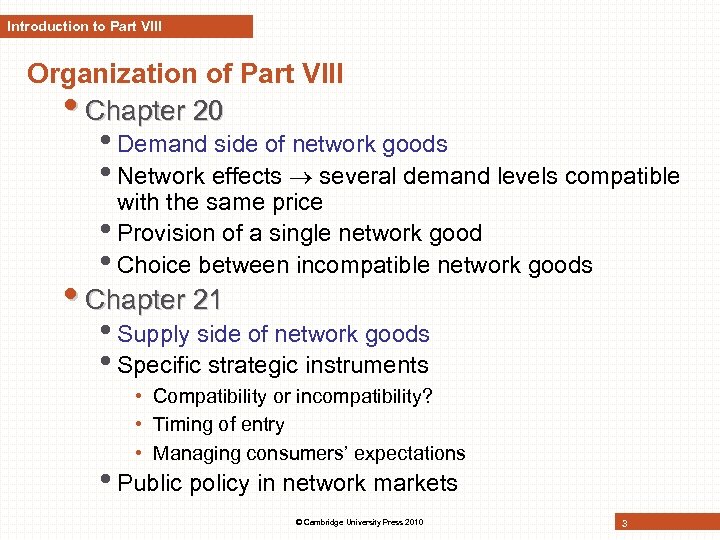

Introduction to Part VIII Organization of Part VIII • Chapter 20 • Demand side of network goods • Network effects several demand levels compatible with the same price • Provision of a single network good • Choice between incompatible network goods • Chapter 21 • Supply side of network goods • Specific strategic instruments • Compatibility or incompatibility? • Timing of entry • Managing consumers’ expectations • Public policy in network markets © Cambridge University Press 2010 3

Introduction to Part VIII Organization of Part VIII • Chapter 20 • Demand side of network goods • Network effects several demand levels compatible with the same price • Provision of a single network good • Choice between incompatible network goods • Chapter 21 • Supply side of network goods • Specific strategic instruments • Compatibility or incompatibility? • Timing of entry • Managing consumers’ expectations • Public policy in network markets © Cambridge University Press 2010 3

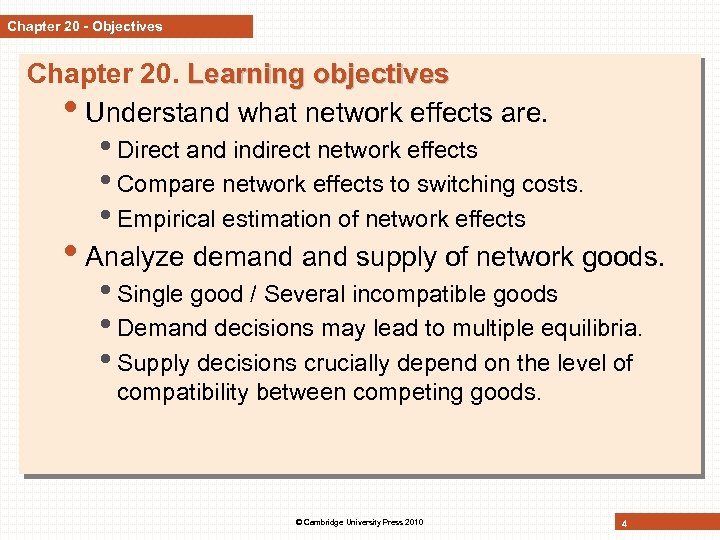

Chapter 20 - Objectives Chapter 20. Learning objectives • Understand what network effects are. • Direct and indirect network effects • Compare network effects to switching costs. • Empirical estimation of network effects • Analyze demand supply of network goods. • Single good / Several incompatible goods • Demand decisions may lead to multiple equilibria. • Supply decisions crucially depend on the level of compatibility between competing goods. © Cambridge University Press 2010 4

Chapter 20 - Objectives Chapter 20. Learning objectives • Understand what network effects are. • Direct and indirect network effects • Compare network effects to switching costs. • Empirical estimation of network effects • Analyze demand supply of network goods. • Single good / Several incompatible goods • Demand decisions may lead to multiple equilibria. • Supply decisions crucially depend on the level of compatibility between competing goods. © Cambridge University Press 2010 4

Chapter 20 - Network effects • Basic idea • Other things being equal, it's better to be connected to a bigger network. • More precisely • A product exhibits network effects if each user's payoff is increasing in the number of other users of that product or of products compatible with it. • Observed in 2 types of markets • Network (or communication) markets • The benefit of consumers comes from the ability to communicate with other consumers via the network. • Direct network effects: more agents in the network more effects communication opportunities more incentives to join the network • Examples: phone, fax, email, instant messaging, languages © Cambridge University Press 2010 5

Chapter 20 - Network effects • Basic idea • Other things being equal, it's better to be connected to a bigger network. • More precisely • A product exhibits network effects if each user's payoff is increasing in the number of other users of that product or of products compatible with it. • Observed in 2 types of markets • Network (or communication) markets • The benefit of consumers comes from the ability to communicate with other consumers via the network. • Direct network effects: more agents in the network more effects communication opportunities more incentives to join the network • Examples: phone, fax, email, instant messaging, languages © Cambridge University Press 2010 5

Chapter 20 - Network effects (cont’d) • Observed in 2 types of markets (cont’d) • System markets • Products are obtained by combining components in a complementary way (e. g. , hardware + software). • Indirect network effects: more users of the system more effects developers desire to write application for the system more incentives for users to buy the system. • Special case: two-sided markets (see Chapter 22) • Examples: videogame consoles, CD and DVD players • Network effects (NE) and switching costs (SC) • Meaning of compatibility • SC. Consumer values compatibility between his/her purchases (ability to take advantage of the same investment). • NE. Consumer values compatibility with other consumers' purchases (ability to communicate or to take advantage of the same complements). © Cambridge University Press 2010 6

Chapter 20 - Network effects (cont’d) • Observed in 2 types of markets (cont’d) • System markets • Products are obtained by combining components in a complementary way (e. g. , hardware + software). • Indirect network effects: more users of the system more effects developers desire to write application for the system more incentives for users to buy the system. • Special case: two-sided markets (see Chapter 22) • Examples: videogame consoles, CD and DVD players • Network effects (NE) and switching costs (SC) • Meaning of compatibility • SC. Consumer values compatibility between his/her purchases (ability to take advantage of the same investment). • NE. Consumer values compatibility with other consumers' purchases (ability to communicate or to take advantage of the same complements). © Cambridge University Press 2010 6

Chapter 20 - Network effects (cont’d) • NE and SC (cont’d) • Competition vs. contracts • SC. Competition focuses on streams of products or services, while contracts often cover only the present. • NE. Competition concerns selling to large groups of users, while contracts usually cover only a bilateral transaction between one seller and one user. • SC and NE. Incomplete contracts potential market failures • Expectations play a key role • Contracts fail to specify complementary transactions buyers' expectations about them are crucial. • History matters • Consumers: past adoptions guide future adoptions • Firms: past market share is a valuable asset © Cambridge University Press 2010 7

Chapter 20 - Network effects (cont’d) • NE and SC (cont’d) • Competition vs. contracts • SC. Competition focuses on streams of products or services, while contracts often cover only the present. • NE. Competition concerns selling to large groups of users, while contracts usually cover only a bilateral transaction between one seller and one user. • SC and NE. Incomplete contracts potential market failures • Expectations play a key role • Contracts fail to specify complementary transactions buyers' expectations about them are crucial. • History matters • Consumers: past adoptions guide future adoptions • Firms: past market share is a valuable asset © Cambridge University Press 2010 7

Chapter 20 - Network effects Case. Network effects or switching costs? • Network effects switching costs • When groups of users make sequential choices, early choices tend to commit later users collective switching costs • Switching costs network effects • When choosing between competing systems, consumers tend to privilege the one offering the largest (current and future) availability of applications. • This availability depends on the number of consumers who adopt the system in question only if there are switching costs between systems, both for consumers and for application writers. • These switching costs are related to the degree of compatibility between systems. © Cambridge University Press 2010 8

Chapter 20 - Network effects Case. Network effects or switching costs? • Network effects switching costs • When groups of users make sequential choices, early choices tend to commit later users collective switching costs • Switching costs network effects • When choosing between competing systems, consumers tend to privilege the one offering the largest (current and future) availability of applications. • This availability depends on the number of consumers who adopt the system in question only if there are switching costs between systems, both for consumers and for application writers. • These switching costs are related to the degree of compatibility between systems. © Cambridge University Press 2010 8

Chapter 20 - Network effects (cont’d) • Empirical evidence • Theoretical prediction • Value of network good with size of associated network • How to test it? • Include demand for the good as a predictor of itself? ü Fraught with difficulty ü Positive coefficient could be the result of network effects, but also of correlations with unobserved taste or quality variables, or of herding and learning effects. • Hedonic price approach ü Estimate implicit price of having either an installed base, or compatible products, or an established standard. • Nested logit approach ü Indirect network effects are characterized by the interaction between consumers’ hardware choice and software producer’s supply decisions. © Cambridge University Press 2010 9

Chapter 20 - Network effects (cont’d) • Empirical evidence • Theoretical prediction • Value of network good with size of associated network • How to test it? • Include demand for the good as a predictor of itself? ü Fraught with difficulty ü Positive coefficient could be the result of network effects, but also of correlations with unobserved taste or quality variables, or of herding and learning effects. • Hedonic price approach ü Estimate implicit price of having either an installed base, or compatible products, or an established standard. • Nested logit approach ü Indirect network effects are characterized by the interaction between consumers’ hardware choice and software producer’s supply decisions. © Cambridge University Press 2010 9

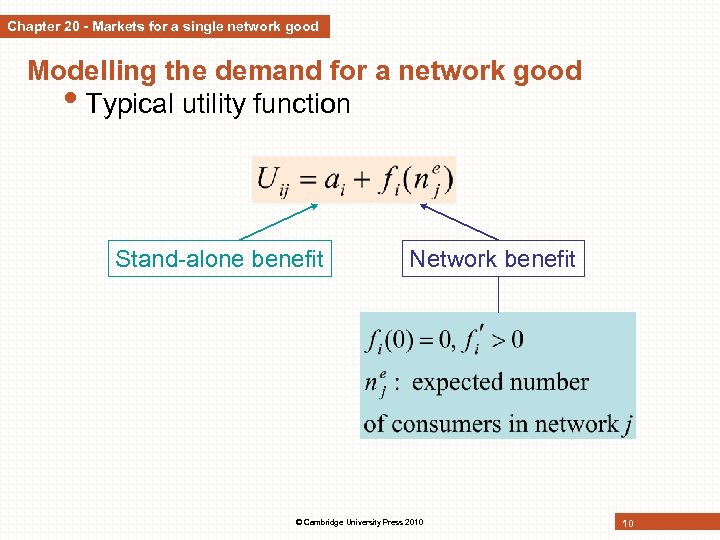

Chapter 20 - Markets for a single network good Modelling the demand for a network good • Typical utility function Stand-alone benefit Network benefit © Cambridge University Press 2010 10

Chapter 20 - Markets for a single network good Modelling the demand for a network good • Typical utility function Stand-alone benefit Network benefit © Cambridge University Press 2010 10

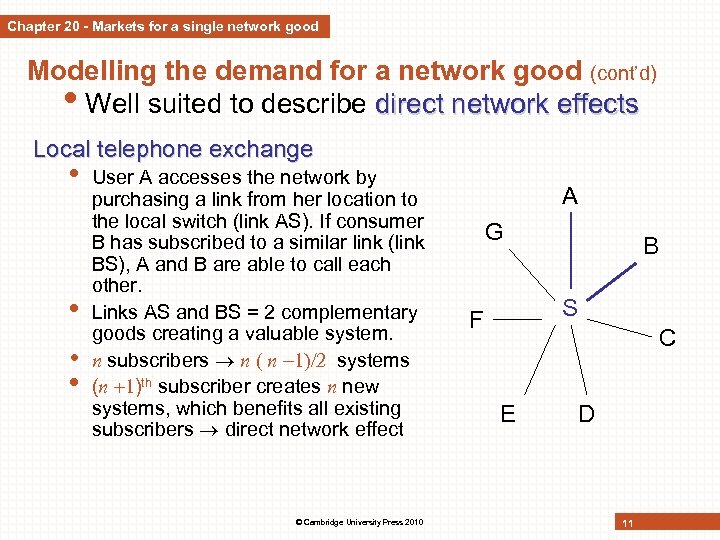

Chapter 20 - Markets for a single network good Modelling the demand for a network good (cont’d) • Well suited to describe direct network effects Local telephone exchange • • User A accesses the network by purchasing a link from her location to the local switch (link AS). If consumer B has subscribed to a similar link (link BS), A and B are able to call each other. Links AS and BS = 2 complementary goods creating a valuable system. n subscribers n n systems (n )th subscriber creates n new systems, which benefits all existing subscribers direct network effect © Cambridge University Press 2010 A G B S F C E D 11

Chapter 20 - Markets for a single network good Modelling the demand for a network good (cont’d) • Well suited to describe direct network effects Local telephone exchange • • User A accesses the network by purchasing a link from her location to the local switch (link AS). If consumer B has subscribed to a similar link (link BS), A and B are able to call each other. Links AS and BS = 2 complementary goods creating a valuable system. n subscribers n n systems (n )th subscriber creates n new systems, which benefits all existing subscribers direct network effect © Cambridge University Press 2010 A G B S F C E D 11

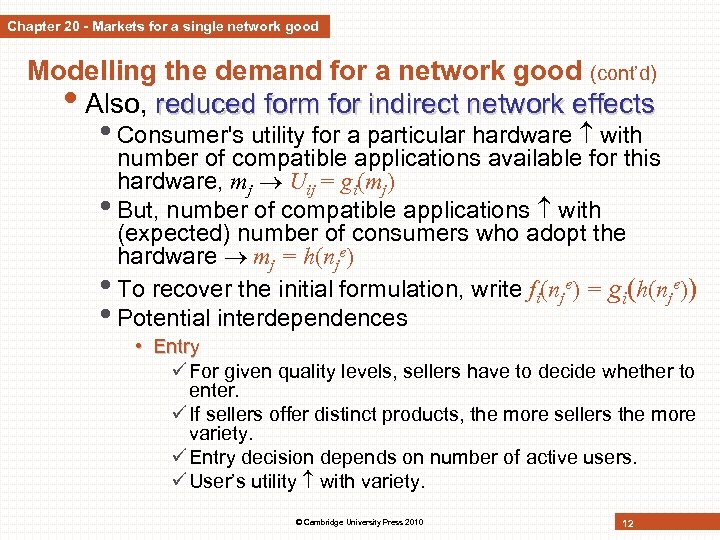

Chapter 20 - Markets for a single network good Modelling the demand for a network good (cont’d) • Also, reduced form for indirect network effects • Consumer's utility for a particular hardware with number of compatible applications available for this hardware, mj Uij = gi(mj) • But, number of compatible applications with (expected) number of consumers who adopt the hardware mj = h(nje) • To recover the initial formulation, write fi(nje) = gi(h(nje)) • Potential interdependences • Entry ü For given quality levels, sellers have to decide whether to enter. ü If sellers offer distinct products, the more sellers the more variety. ü Entry decision depends on number of active users. ü User’s utility with variety. © Cambridge University Press 2010 12

Chapter 20 - Markets for a single network good Modelling the demand for a network good (cont’d) • Also, reduced form for indirect network effects • Consumer's utility for a particular hardware with number of compatible applications available for this hardware, mj Uij = gi(mj) • But, number of compatible applications with (expected) number of consumers who adopt the hardware mj = h(nje) • To recover the initial formulation, write fi(nje) = gi(h(nje)) • Potential interdependences • Entry ü For given quality levels, sellers have to decide whether to enter. ü If sellers offer distinct products, the more sellers the more variety. ü Entry decision depends on number of active users. ü User’s utility with variety. © Cambridge University Press 2010 12

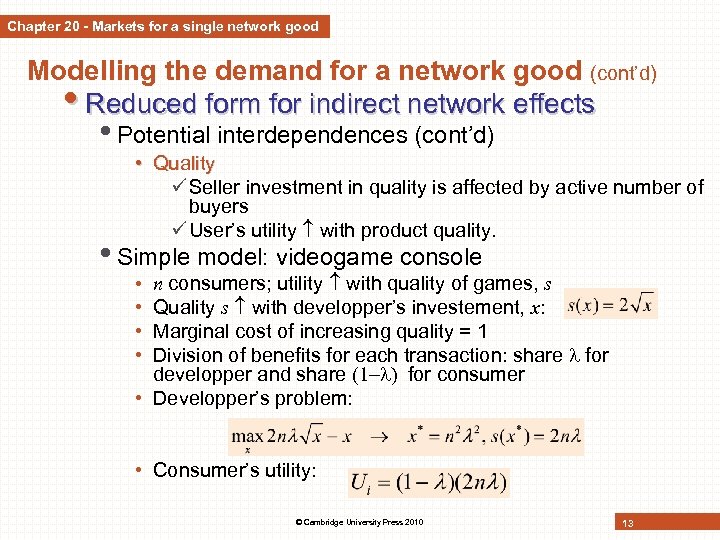

Chapter 20 - Markets for a single network good Modelling the demand for a network good (cont’d) • Reduced form for indirect network effects • Potential interdependences (cont’d) • Quality ü Seller investment in quality is affected by active number of buyers ü User’s utility with product quality. • Simple model: videogame console n consumers; utility with quality of games, s Quality s with developper’s investement, x: Marginal cost of increasing quality = 1 Division of benefits for each transaction: share for developper and share for consumer • Developper’s problem: • • • Consumer’s utility: © Cambridge University Press 2010 13

Chapter 20 - Markets for a single network good Modelling the demand for a network good (cont’d) • Reduced form for indirect network effects • Potential interdependences (cont’d) • Quality ü Seller investment in quality is affected by active number of buyers ü User’s utility with product quality. • Simple model: videogame console n consumers; utility with quality of games, s Quality s with developper’s investement, x: Marginal cost of increasing quality = 1 Division of benefits for each transaction: share for developper and share for consumer • Developper’s problem: • • • Consumer’s utility: © Cambridge University Press 2010 13

Chapter 20 - Markets for a single network good Modelling the demand for a network good (cont’d) • Lesson: Indirect network effects can arise in a buyer– seller context because of the effect of consumer participation (and intensity of use) on quality, price and variety. In the reduced form consumer utility directly depends on the number of consumers. • Modelling expectations • Fulfilled expectations • Consumers base their current purchasing decisions on their expectations about future network sizes. • Attention is restricted on equilibria in which these expectations turn out to be correct (i. e. , are rational). • Myopic expectations • Consumers base their decisions only on actual network sizes. © Cambridge University Press 2010 14

Chapter 20 - Markets for a single network good Modelling the demand for a network good (cont’d) • Lesson: Indirect network effects can arise in a buyer– seller context because of the effect of consumer participation (and intensity of use) on quality, price and variety. In the reduced form consumer utility directly depends on the number of consumers. • Modelling expectations • Fulfilled expectations • Consumers base their current purchasing decisions on their expectations about future network sizes. • Attention is restricted on equilibria in which these expectations turn out to be correct (i. e. , are rational). • Myopic expectations • Consumers base their decisions only on actual network sizes. © Cambridge University Press 2010 14

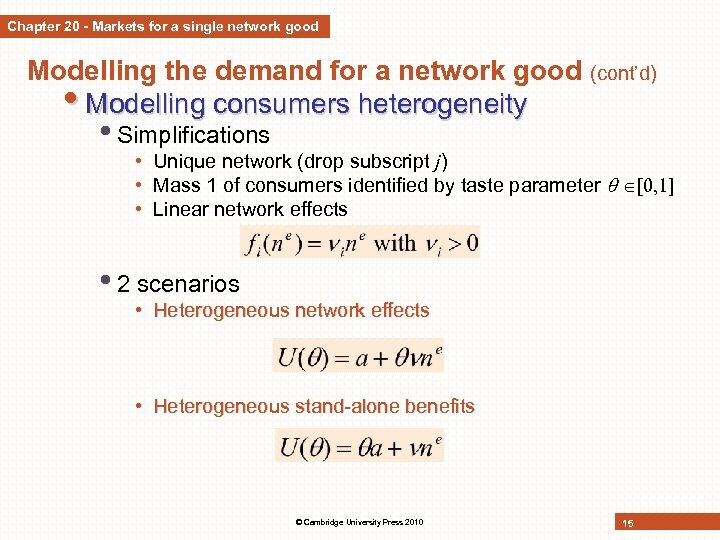

Chapter 20 - Markets for a single network good Modelling the demand for a network good • Modelling consumers heterogeneity (cont’d) • Simplifications • Unique network (drop subscript j) • Mass 1 of consumers identified by taste parameter • Linear network effects • 2 scenarios • Heterogeneous network effects • Heterogeneous stand-alone benefits © Cambridge University Press 2010 15

Chapter 20 - Markets for a single network good Modelling the demand for a network good • Modelling consumers heterogeneity (cont’d) • Simplifications • Unique network (drop subscript j) • Mass 1 of consumers identified by taste parameter • Linear network effects • 2 scenarios • Heterogeneous network effects • Heterogeneous stand-alone benefits © Cambridge University Press 2010 15

Chapter 20 - Markets for a single network good Case. Heterogeneous adopters for network goods • Consumer electronics products • Characterized by sequential adoption • Minority of early adopters “high ” • Why are early adopters keener to adopt the new network good? • Value more network benefits or stand-alone benefits? • Blackberry • Early adopters = business people value highly the possibility of reading and sending emails any time & anywhere heterogeneous network benefits • High-definition television • Early adopters = “tech aficionados” primarily interested in superior picture quality heterogeneous stand-alone benefits © Cambridge University Press 2010 16

Chapter 20 - Markets for a single network good Case. Heterogeneous adopters for network goods • Consumer electronics products • Characterized by sequential adoption • Minority of early adopters “high ” • Why are early adopters keener to adopt the new network good? • Value more network benefits or stand-alone benefits? • Blackberry • Early adopters = business people value highly the possibility of reading and sending emails any time & anywhere heterogeneous network benefits • High-definition television • Early adopters = “tech aficionados” primarily interested in superior picture quality heterogeneous stand-alone benefits © Cambridge University Press 2010 16

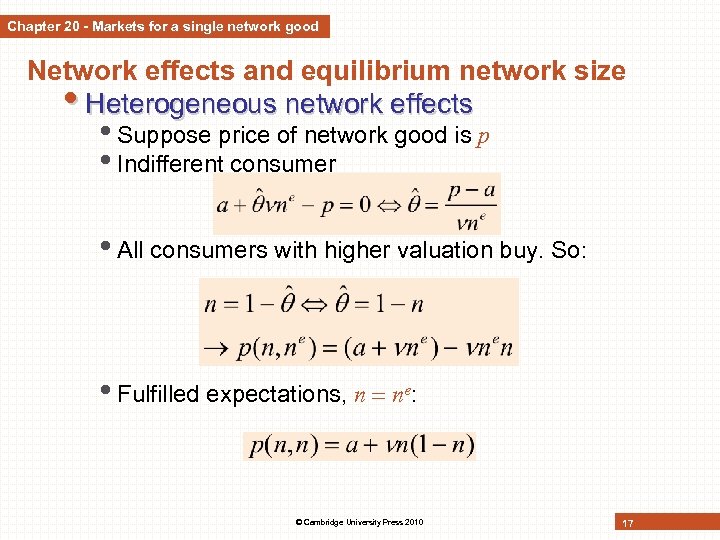

Chapter 20 - Markets for a single network good Network effects and equilibrium network size • Heterogeneous network effects • Suppose price of network good is p • Indifferent consumer • All consumers with higher valuation buy. So: • Fulfilled expectations, n ne: © Cambridge University Press 2010 17

Chapter 20 - Markets for a single network good Network effects and equilibrium network size • Heterogeneous network effects • Suppose price of network good is p • Indifferent consumer • All consumers with higher valuation buy. So: • Fulfilled expectations, n ne: © Cambridge University Press 2010 17

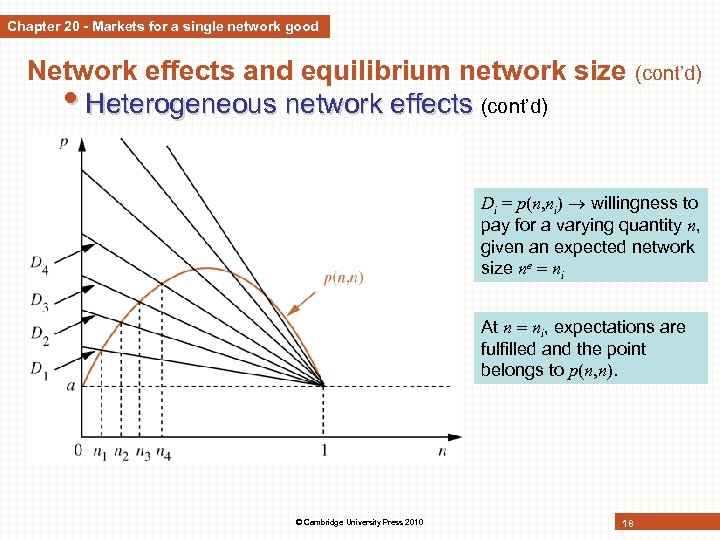

Chapter 20 - Markets for a single network good Network effects and equilibrium network size (cont’d) • Heterogeneous network effects (cont’d) Di = p(n, ni) willingness to pay for a varying quantity n, given an expected network size ne ni At n ni, expectations are fulfilled and the point belongs to p(n, n). © Cambridge University Press 2010 18

Chapter 20 - Markets for a single network good Network effects and equilibrium network size (cont’d) • Heterogeneous network effects (cont’d) Di = p(n, ni) willingness to pay for a varying quantity n, given an expected network size ne ni At n ni, expectations are fulfilled and the point belongs to p(n, n). © Cambridge University Press 2010 18

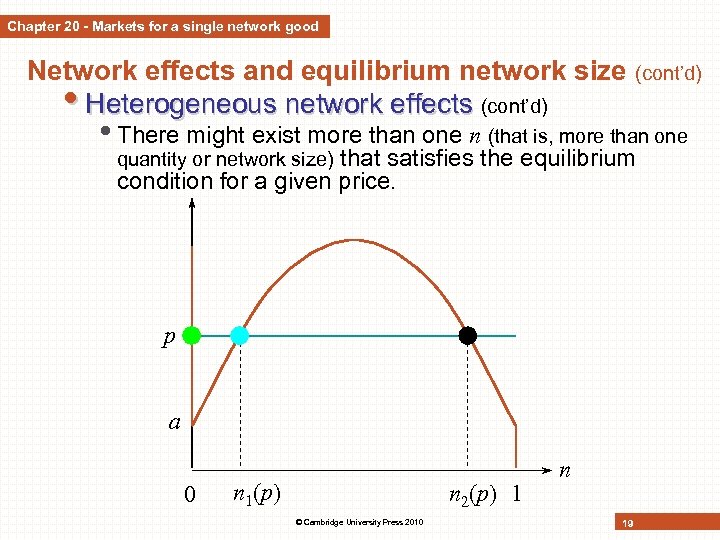

Chapter 20 - Markets for a single network good Network effects and equilibrium network size (cont’d) • Heterogeneous network effects (cont’d) • There might exist more than one n (that is, more than one that satisfies the equilibrium condition for a given price. quantity or network size) p a n 1(p) n 2(p) 1 © Cambridge University Press 2010 n 19

Chapter 20 - Markets for a single network good Network effects and equilibrium network size (cont’d) • Heterogeneous network effects (cont’d) • There might exist more than one n (that is, more than one that satisfies the equilibrium condition for a given price. quantity or network size) p a n 1(p) n 2(p) 1 © Cambridge University Press 2010 n 19

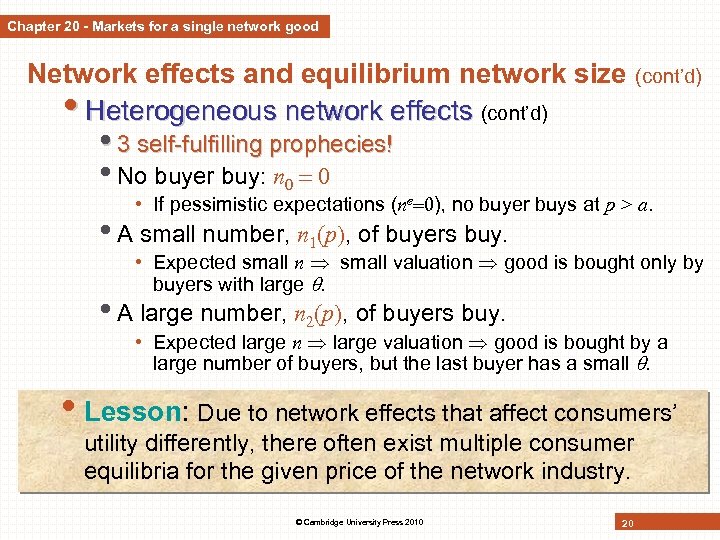

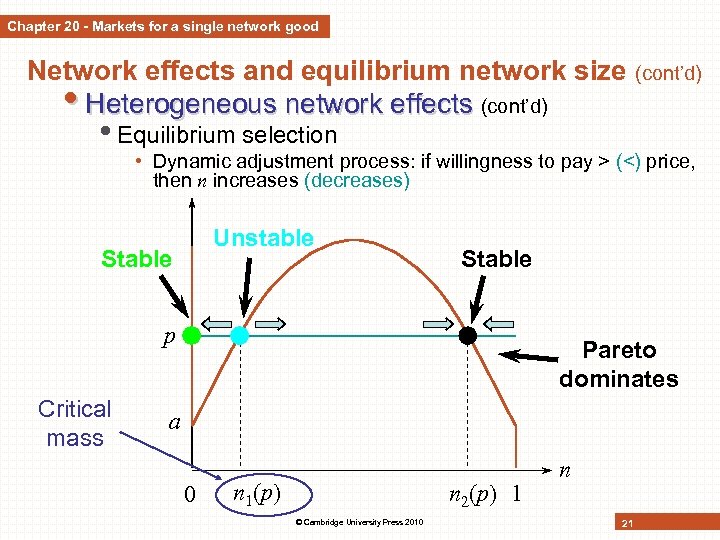

Chapter 20 - Markets for a single network good Network effects and equilibrium network size (cont’d) • Heterogeneous network effects (cont’d) • 3 self-fulfilling prophecies! • No buyer buy: n • If pessimistic expectations (ne ), no buyer buys at p > a. • A small number, n 1(p), of buyers buy. • Expected small n small valuation good is bought only by buyers with large . • A large number, n 2(p), of buyers buy. • Expected large n large valuation good is bought by a large number of buyers, but the last buyer has a small . • Lesson: Due to network effects that affect consumers’ utility differently, there often exist multiple consumer equilibria for the given price of the network industry. © Cambridge University Press 2010 20

Chapter 20 - Markets for a single network good Network effects and equilibrium network size (cont’d) • Heterogeneous network effects (cont’d) • 3 self-fulfilling prophecies! • No buyer buy: n • If pessimistic expectations (ne ), no buyer buys at p > a. • A small number, n 1(p), of buyers buy. • Expected small n small valuation good is bought only by buyers with large . • A large number, n 2(p), of buyers buy. • Expected large n large valuation good is bought by a large number of buyers, but the last buyer has a small . • Lesson: Due to network effects that affect consumers’ utility differently, there often exist multiple consumer equilibria for the given price of the network industry. © Cambridge University Press 2010 20

Chapter 20 - Markets for a single network good Network effects and equilibrium network size (cont’d) • Heterogeneous network effects (cont’d) • Equilibrium selection • Dynamic adjustment process: if willingness to pay > (<) price, then n increases (decreases) Unstable Stable p Critical mass Pareto dominates a n 1(p) n 2(p) 1 © Cambridge University Press 2010 n 21

Chapter 20 - Markets for a single network good Network effects and equilibrium network size (cont’d) • Heterogeneous network effects (cont’d) • Equilibrium selection • Dynamic adjustment process: if willingness to pay > (<) price, then n increases (decreases) Unstable Stable p Critical mass Pareto dominates a n 1(p) n 2(p) 1 © Cambridge University Press 2010 n 21

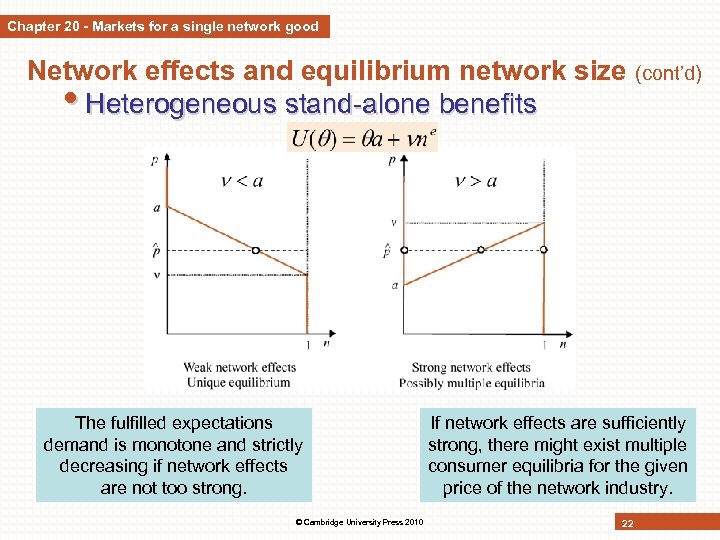

Chapter 20 - Markets for a single network good Network effects and equilibrium network size (cont’d) • Heterogeneous stand-alone benefits The fulfilled expectations demand is monotone and strictly decreasing if network effects are not too strong. © Cambridge University Press 2010 If network effects are sufficiently strong, there might exist multiple consumer equilibria for the given price of the network industry. 22

Chapter 20 - Markets for a single network good Network effects and equilibrium network size (cont’d) • Heterogeneous stand-alone benefits The fulfilled expectations demand is monotone and strictly decreasing if network effects are not too strong. © Cambridge University Press 2010 If network effects are sufficiently strong, there might exist multiple consumer equilibria for the given price of the network industry. 22

Chapter 20 - Markets for a single network good Provision of a network good • Assumptions • A single network good is available. • Consumers’ expectations are fulfilled at equilibrium. • Selection of Pareto-dominant equilibrium (if multiplicity) • Constant marginal cost of production: c • Supply decision • Perfect competition vs. Monopoly • Comparison with social optimum • Are network effects a source of externalities? • See details in book. © Cambridge University Press 2010 23

Chapter 20 - Markets for a single network good Provision of a network good • Assumptions • A single network good is available. • Consumers’ expectations are fulfilled at equilibrium. • Selection of Pareto-dominant equilibrium (if multiplicity) • Constant marginal cost of production: c • Supply decision • Perfect competition vs. Monopoly • Comparison with social optimum • Are network effects a source of externalities? • See details in book. © Cambridge University Press 2010 23

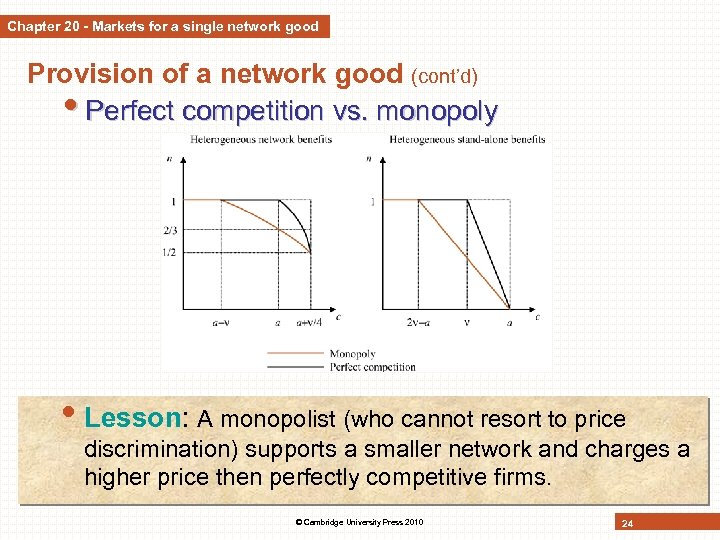

Chapter 20 - Markets for a single network good Provision of a network good (cont’d) • Perfect competition vs. monopoly • Lesson: A monopolist (who cannot resort to price discrimination) supports a smaller network and charges a higher price then perfectly competitive firms. © Cambridge University Press 2010 24

Chapter 20 - Markets for a single network good Provision of a network good (cont’d) • Perfect competition vs. monopoly • Lesson: A monopolist (who cannot resort to price discrimination) supports a smaller network and charges a higher price then perfectly competitive firms. © Cambridge University Press 2010 24

Chapter 20 - Markets for a single network good Provision of a network good (cont’d) • Comparison with social optimum • Social welfare is maximized when all consumers join the network (n ) underprovision by the market network externalities • Sources of market failure • Consumers fail to internalize that other consumers are also made better off by their decision to “join the network”. • If large enough production cost, neither a monopolist nor competitive firms manage to internalize these external effects. • Lesson: There is a tendency towards underprovision of the network good by the monopolist, and even by perfectly competitive firms. © Cambridge University Press 2010 25

Chapter 20 - Markets for a single network good Provision of a network good (cont’d) • Comparison with social optimum • Social welfare is maximized when all consumers join the network (n ) underprovision by the market network externalities • Sources of market failure • Consumers fail to internalize that other consumers are also made better off by their decision to “join the network”. • If large enough production cost, neither a monopolist nor competitive firms manage to internalize these external effects. • Lesson: There is a tendency towards underprovision of the network good by the monopolist, and even by perfectly competitive firms. © Cambridge University Press 2010 25

Chapter 20 - Markets for several network goods • Consumers may have to choose between several competing network goods. • Relevant if network goods are incompatible. • 2 approaches • Consumers’ coordination efforts • Consumers try to coordinate their actions to make their choices compatible. • Simplifying assumptions: 2 competitively supplied goods • Firms’ compatibility decisions • Firms may decide to provide some degree of compatibility between their products. • Simplifying assumptions: Cournot duopoly © Cambridge University Press 2010 26

Chapter 20 - Markets for several network goods • Consumers may have to choose between several competing network goods. • Relevant if network goods are incompatible. • 2 approaches • Consumers’ coordination efforts • Consumers try to coordinate their actions to make their choices compatible. • Simplifying assumptions: 2 competitively supplied goods • Firms’ compatibility decisions • Firms may decide to provide some degree of compatibility between their products. • Simplifying assumptions: Cournot duopoly © Cambridge University Press 2010 26

Chapter 20 - Markets for several network goods Demand for incompatible network goods • Main results • Coordination problems among consumers • Potential market failures • Dominance of the market by the ‘wrong’ technology • Excess inertia or excess momentum • More likely under incomplete information • Sequential choices: self-reinforcement and lock-in • Model • 2 goods exhibiting network effects: A and B • Heterogeneous stand-alone benefits ü ‘A-fans’ derive larger benefits from A than from B ü ‘B-fans’ derive larger benefits from B than from A ü Equally represented in the population • Myopic expectations © Cambridge University Press 2010 27

Chapter 20 - Markets for several network goods Demand for incompatible network goods • Main results • Coordination problems among consumers • Potential market failures • Dominance of the market by the ‘wrong’ technology • Excess inertia or excess momentum • More likely under incomplete information • Sequential choices: self-reinforcement and lock-in • Model • 2 goods exhibiting network effects: A and B • Heterogeneous stand-alone benefits ü ‘A-fans’ derive larger benefits from A than from B ü ‘B-fans’ derive larger benefits from B than from A ü Equally represented in the population • Myopic expectations © Cambridge University Press 2010 27

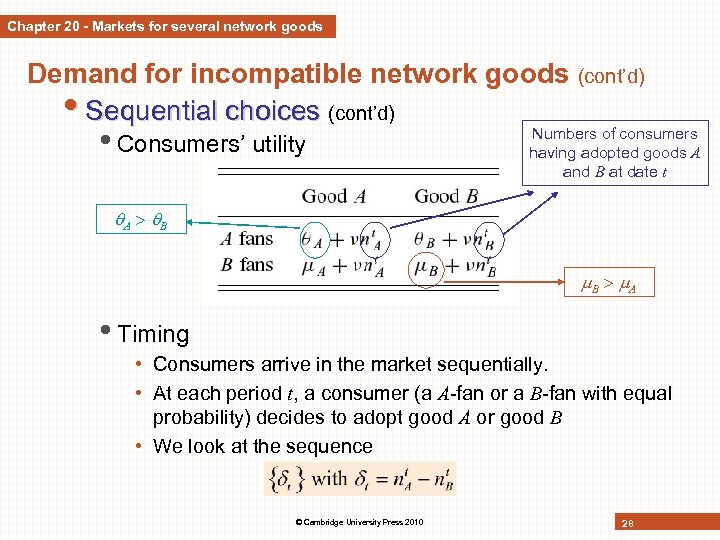

Chapter 20 - Markets for several network goods Demand for incompatible network goods (cont’d) • Sequential choices (cont’d) • Consumers’ utility Numbers of consumers having adopted goods A and B at date t A B B A • Timing • Consumers arrive in the market sequentially. • At each period t, a consumer (a A-fan or a B-fan with equal probability) decides to adopt good A or good B • We look at the sequence © Cambridge University Press 2010 28

Chapter 20 - Markets for several network goods Demand for incompatible network goods (cont’d) • Sequential choices (cont’d) • Consumers’ utility Numbers of consumers having adopted goods A and B at date t A B B A • Timing • Consumers arrive in the market sequentially. • At each period t, a consumer (a A-fan or a B-fan with equal probability) decides to adopt good A or good B • We look at the sequence © Cambridge University Press 2010 28

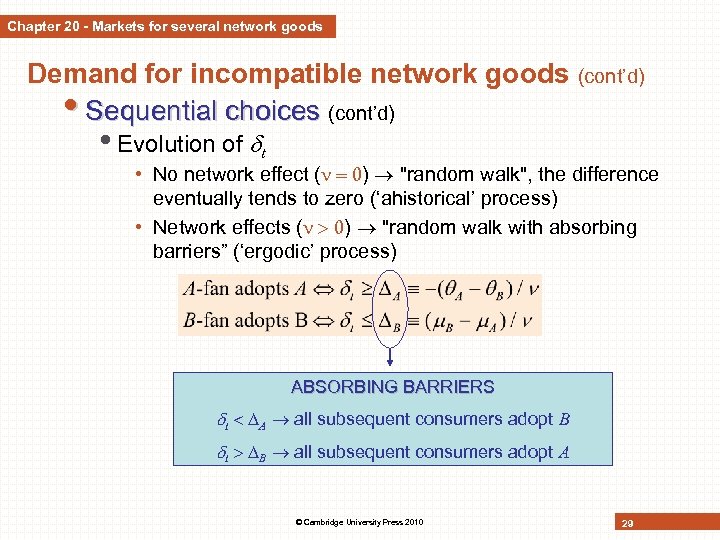

Chapter 20 - Markets for several network goods Demand for incompatible network goods (cont’d) • Sequential choices (cont’d) • Evolution of t • No network effect ( ) "random walk", the difference eventually tends to zero (‘ahistorical’ process) • Network effects ( ) "random walk with absorbing barriers” (‘ergodic’ process) ABSORBING BARRIERS t A all subsequent consumers adopt B t B all subsequent consumers adopt A © Cambridge University Press 2010 29

Chapter 20 - Markets for several network goods Demand for incompatible network goods (cont’d) • Sequential choices (cont’d) • Evolution of t • No network effect ( ) "random walk", the difference eventually tends to zero (‘ahistorical’ process) • Network effects ( ) "random walk with absorbing barriers” (‘ergodic’ process) ABSORBING BARRIERS t A all subsequent consumers adopt B t B all subsequent consumers adopt A © Cambridge University Press 2010 29

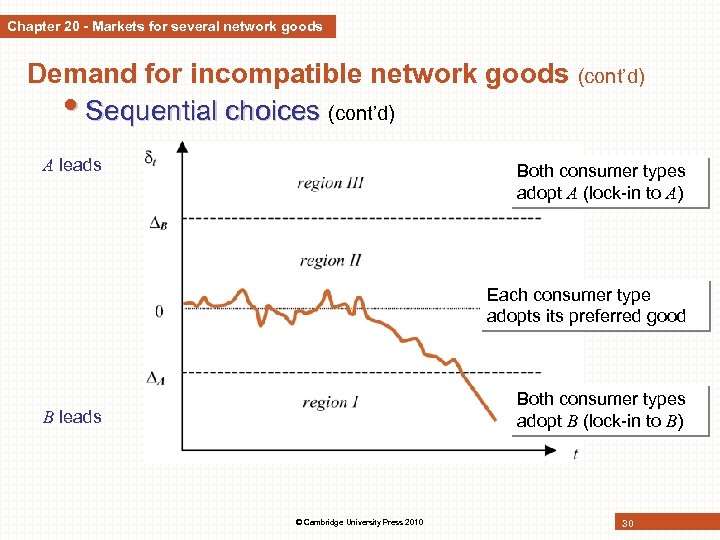

Chapter 20 - Markets for several network goods Demand for incompatible network goods (cont’d) • Sequential choices (cont’d) A leads Both consumer types adopt A (lock-in to A) Each consumer type adopts its preferred good Both consumer types adopt B (lock-in to B) B leads © Cambridge University Press 2010 30

Chapter 20 - Markets for several network goods Demand for incompatible network goods (cont’d) • Sequential choices (cont’d) A leads Both consumer types adopt A (lock-in to A) Each consumer type adopts its preferred good Both consumer types adopt B (lock-in to B) B leads © Cambridge University Press 2010 30

Chapter 20 - Markets for several network goods Demand for incompatible network goods (cont’d) • Sequential choices (cont’d) • Competition between incompatible goods: properties • Path-dependence outcome depends on the way in which adoptions build up (i. e. , on the path the process takes). • Inflexibility, or lock-in the left-behind good would need to Inflexibility bridge a widening gap if it is chosen by adopters at all. • Non predictability the process locks in to monopoly of one of the 2 goods, but which good is not predictable in advance. • Potential inefficiency the good that “takes the market” needs not be the one with the longer-term higher payoff. • Lesson: The competition between incompatible network goods is likely to lead, in the long run, to market dominance by a single good. The dominant good cannot be predicted beforehand might not be the best available option. © Cambridge University Press 2010 31

Chapter 20 - Markets for several network goods Demand for incompatible network goods (cont’d) • Sequential choices (cont’d) • Competition between incompatible goods: properties • Path-dependence outcome depends on the way in which adoptions build up (i. e. , on the path the process takes). • Inflexibility, or lock-in the left-behind good would need to Inflexibility bridge a widening gap if it is chosen by adopters at all. • Non predictability the process locks in to monopoly of one of the 2 goods, but which good is not predictable in advance. • Potential inefficiency the good that “takes the market” needs not be the one with the longer-term higher payoff. • Lesson: The competition between incompatible network goods is likely to lead, in the long run, to market dominance by a single good. The dominant good cannot be predicted beforehand might not be the best available option. © Cambridge University Press 2010 31

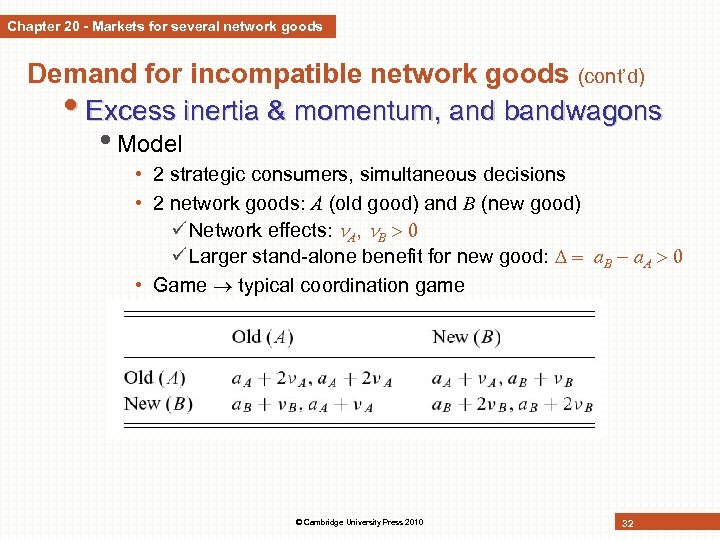

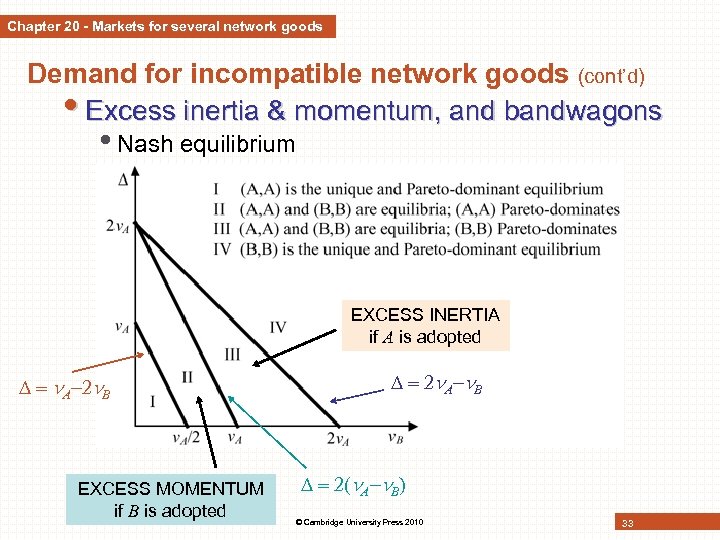

Chapter 20 - Markets for several network goods Demand for incompatible network goods (cont’d) • Excess inertia & momentum, and bandwagons • Model • 2 strategic consumers, simultaneous decisions • 2 network goods: A (old good) and B (new good) ü Network effects: A, B ü Larger stand-alone benefit for new good: a. B a. A • Game typical coordination game © Cambridge University Press 2010 32

Chapter 20 - Markets for several network goods Demand for incompatible network goods (cont’d) • Excess inertia & momentum, and bandwagons • Model • 2 strategic consumers, simultaneous decisions • 2 network goods: A (old good) and B (new good) ü Network effects: A, B ü Larger stand-alone benefit for new good: a. B a. A • Game typical coordination game © Cambridge University Press 2010 32

Chapter 20 - Markets for several network goods Demand for incompatible network goods (cont’d) • Excess inertia & momentum, and bandwagons • Nash equilibrium EXCESS INERTIA if A is adopted A B EXCESS MOMENTUM if B is adopted A B © Cambridge University Press 2010 33

Chapter 20 - Markets for several network goods Demand for incompatible network goods (cont’d) • Excess inertia & momentum, and bandwagons • Nash equilibrium EXCESS INERTIA if A is adopted A B EXCESS MOMENTUM if B is adopted A B © Cambridge University Press 2010 33

Chapter 20 - Markets for several network goods Demand for incompatible network goods (cont’d) • Excess inertia & momentum, and bandwagons • If complete information about other users’ preferences • Coordination failures are an artifact of simultaneous decisions (if sequential choices users coordinate on Paretodominating good). • If incomplete information, real possibility of excess information inertia and excess momentum typical situation: • You would enjoy the largest benefits if you and the other user switched to the new good. • But you don’t know the other user’s payoff and there is thus a chance that you would not be followed in the case you initiated the switch. • As you fear the low benefits you would earn in that case, you are not willing to take the risk of moving first. • Now, if the other user is just like you, both of you will wait and no one will switch, therefore failing to achieve high benefits. © Cambridge University Press 2010 34

Chapter 20 - Markets for several network goods Demand for incompatible network goods (cont’d) • Excess inertia & momentum, and bandwagons • If complete information about other users’ preferences • Coordination failures are an artifact of simultaneous decisions (if sequential choices users coordinate on Paretodominating good). • If incomplete information, real possibility of excess information inertia and excess momentum typical situation: • You would enjoy the largest benefits if you and the other user switched to the new good. • But you don’t know the other user’s payoff and there is thus a chance that you would not be followed in the case you initiated the switch. • As you fear the low benefits you would earn in that case, you are not willing to take the risk of moving first. • Now, if the other user is just like you, both of you will wait and no one will switch, therefore failing to achieve high benefits. © Cambridge University Press 2010 34

Chapter 20 - Markets for several network goods Demand for incompatible network goods (cont’d) • Excess inertia & momentum, and bandwagons • Lesson: There is excess inertia when users fail to switch to a new network good although they would be made better off if every user switched. Excess inertia is more likely to happen in markets with indirect rather than direct network effects and where each user only has incomplete rather than full information about the other users’ preferences (which might conflict with hers). • Model with incomplete information • See details in book. • Illustration of ‘Bandwagon equilibrium’ © Cambridge University Press 2010 35

Chapter 20 - Markets for several network goods Demand for incompatible network goods (cont’d) • Excess inertia & momentum, and bandwagons • Lesson: There is excess inertia when users fail to switch to a new network good although they would be made better off if every user switched. Excess inertia is more likely to happen in markets with indirect rather than direct network effects and where each user only has incomplete rather than full information about the other users’ preferences (which might conflict with hers). • Model with incomplete information • See details in book. • Illustration of ‘Bandwagon equilibrium’ © Cambridge University Press 2010 35

Chapter 20 - Markets for several network goods Case. Failure of quadraphonic sound • Early 1970 s • Quadraphonic sound introduced as alternative to stereophonic sound for playing audio recordings. • Higher quality but it didn’t become the new industry standard. • Why did the initial support quickly fade? • Early adopters were dissatisfied. • Several incompatible formats coexisted. • Uncertainty about which version would prevail. • Similar stories • Digital cassettes • Digital videos • Different versions of teletext © Cambridge University Press 2010 36

Chapter 20 - Markets for several network goods Case. Failure of quadraphonic sound • Early 1970 s • Quadraphonic sound introduced as alternative to stereophonic sound for playing audio recordings. • Higher quality but it didn’t become the new industry standard. • Why did the initial support quickly fade? • Early adopters were dissatisfied. • Several incompatible formats coexisted. • Uncertainty about which version would prevail. • Similar stories • Digital cassettes • Digital videos • Different versions of teletext © Cambridge University Press 2010 36

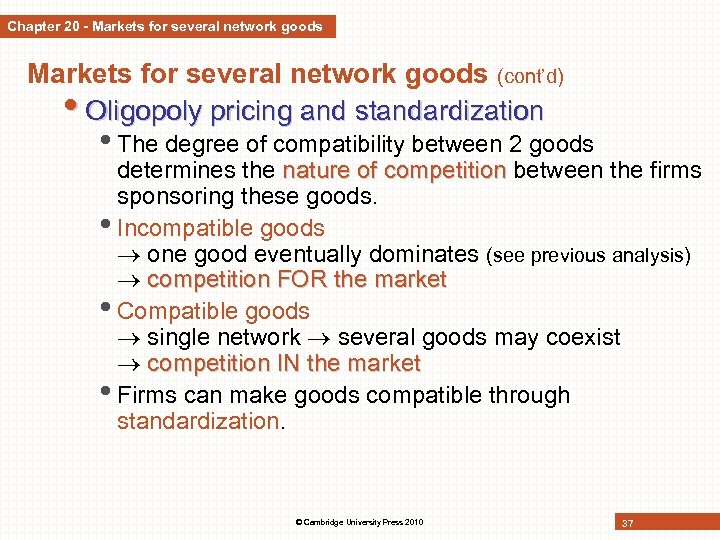

Chapter 20 - Markets for several network goods (cont’d) • Oligopoly pricing and standardization • The degree of compatibility between 2 goods determines the nature of competition between the firms sponsoring these goods. • Incompatible goods one good eventually dominates (see previous analysis) competition FOR the market • Compatible goods single network several goods may coexist competition IN the market • Firms can make goods compatible through standardization. © Cambridge University Press 2010 37

Chapter 20 - Markets for several network goods (cont’d) • Oligopoly pricing and standardization • The degree of compatibility between 2 goods determines the nature of competition between the firms sponsoring these goods. • Incompatible goods one good eventually dominates (see previous analysis) competition FOR the market • Compatible goods single network several goods may coexist competition IN the market • Firms can make goods compatible through standardization. © Cambridge University Press 2010 37

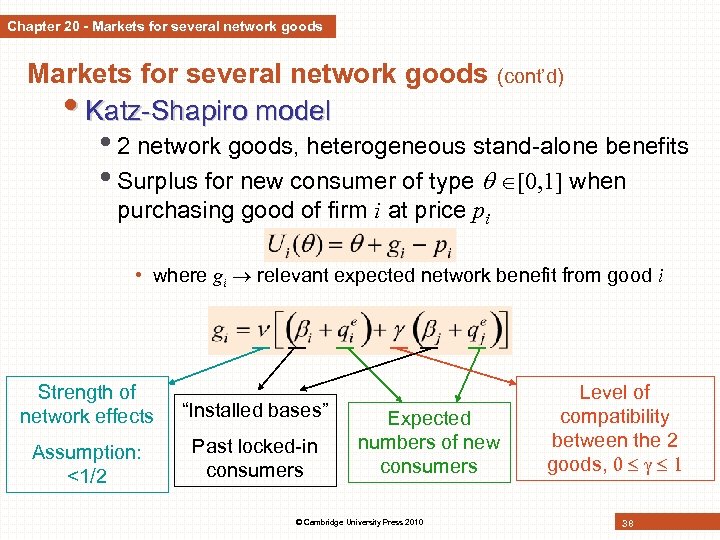

Chapter 20 - Markets for several network goods (cont’d) • Katz-Shapiro model • 2 network goods, heterogeneous stand-alone benefits • Surplus for new consumer of type when purchasing good of firm i at price pi • where gi relevant expected network benefit from good i Strength of network effects “Installed bases” Assumption: <1/2 Past locked-in consumers Expected numbers of new consumers © Cambridge University Press 2010 Level of compatibility between the 2 goods, 38

Chapter 20 - Markets for several network goods (cont’d) • Katz-Shapiro model • 2 network goods, heterogeneous stand-alone benefits • Surplus for new consumer of type when purchasing good of firm i at price pi • where gi relevant expected network benefit from good i Strength of network effects “Installed bases” Assumption: <1/2 Past locked-in consumers Expected numbers of new consumers © Cambridge University Press 2010 Level of compatibility between the 2 goods, 38

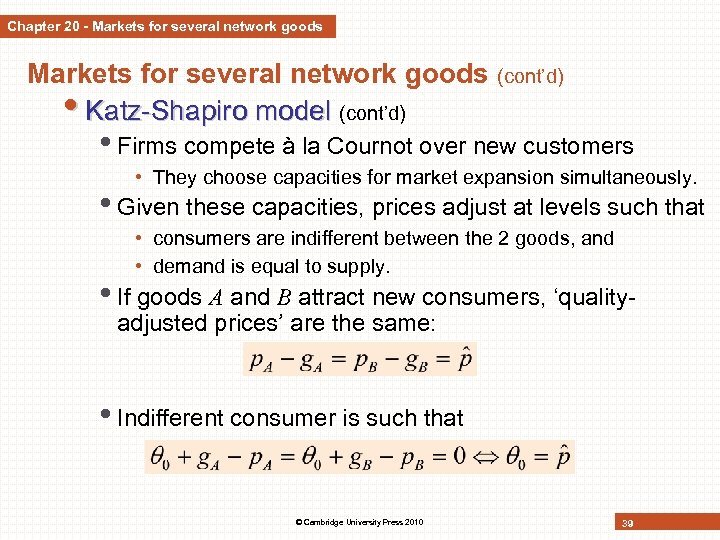

Chapter 20 - Markets for several network goods (cont’d) • Katz-Shapiro model (cont’d) • Firms compete à la Cournot over new customers • They choose capacities for market expansion simultaneously. • Given these capacities, prices adjust at levels such that • consumers are indifferent between the 2 goods, and • demand is equal to supply. • If goods A and B attract new consumers, ‘qualityadjusted prices’ are the same: • Indifferent consumer is such that © Cambridge University Press 2010 39

Chapter 20 - Markets for several network goods (cont’d) • Katz-Shapiro model (cont’d) • Firms compete à la Cournot over new customers • They choose capacities for market expansion simultaneously. • Given these capacities, prices adjust at levels such that • consumers are indifferent between the 2 goods, and • demand is equal to supply. • If goods A and B attract new consumers, ‘qualityadjusted prices’ are the same: • Indifferent consumer is such that © Cambridge University Press 2010 39

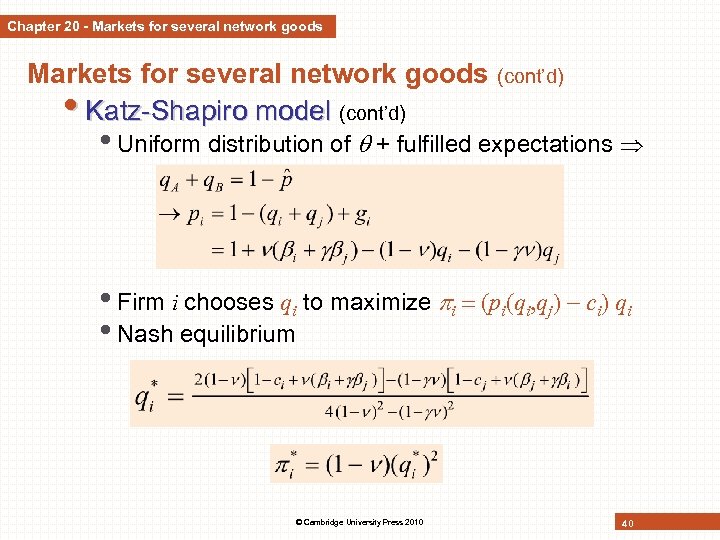

Chapter 20 - Markets for several network goods (cont’d) • Katz-Shapiro model (cont’d) • Uniform distribution of + fulfilled expectations • Firm i chooses qi to maximize i (pi(qi, qj) ci) qi • Nash equilibrium © Cambridge University Press 2010 40

Chapter 20 - Markets for several network goods (cont’d) • Katz-Shapiro model (cont’d) • Uniform distribution of + fulfilled expectations • Firm i chooses qi to maximize i (pi(qi, qj) ci) qi • Nash equilibrium © Cambridge University Press 2010 40

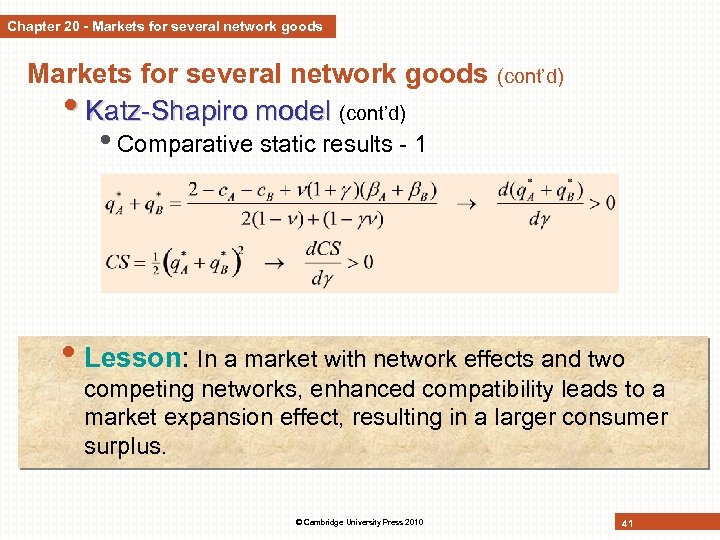

Chapter 20 - Markets for several network goods (cont’d) • Katz-Shapiro model (cont’d) • Comparative static results - 1 • Lesson: In a market with network effects and two competing networks, enhanced compatibility leads to a market expansion effect, resulting in a larger consumer surplus. © Cambridge University Press 2010 41

Chapter 20 - Markets for several network goods (cont’d) • Katz-Shapiro model (cont’d) • Comparative static results - 1 • Lesson: In a market with network effects and two competing networks, enhanced compatibility leads to a market expansion effect, resulting in a larger consumer surplus. © Cambridge University Press 2010 41

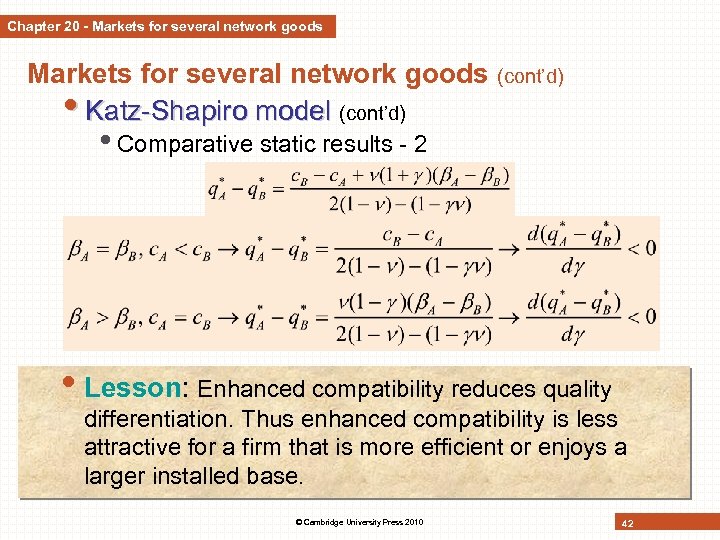

Chapter 20 - Markets for several network goods (cont’d) • Katz-Shapiro model (cont’d) • Comparative static results - 2 • Lesson: Enhanced compatibility reduces quality differentiation. Thus enhanced compatibility is less attractive for a firm that is more efficient or enjoys a larger installed base. © Cambridge University Press 2010 42

Chapter 20 - Markets for several network goods (cont’d) • Katz-Shapiro model (cont’d) • Comparative static results - 2 • Lesson: Enhanced compatibility reduces quality differentiation. Thus enhanced compatibility is less attractive for a firm that is more efficient or enjoys a larger installed base. © Cambridge University Press 2010 42

Chapter 20 - Markets for several network goods Case. Lego - a wall to protect the bricks? • Toy bricks = network good • The more compatible bricks you and your friends have, the larger your building possibilities. • Intellectual Property protection of Lego bricks • Last patents expired in 1978 • Since then, the LEGO Group has zealously guarded its trademarks and other IP rights. • Dozens of lawsuits against competitors • 2005: LEGO failed in its attempt to enforce its trademark for the design of its bricks in the Canadian Supreme Court: ü “The monopoly on the bricks is over, and Mega Bloks and Lego bricks may be interchangeable in the bins of the playrooms of the nation. Dragons, castles and knights may be designed with them, without any distinction. ” © Cambridge University Press 2010 43

Chapter 20 - Markets for several network goods Case. Lego - a wall to protect the bricks? • Toy bricks = network good • The more compatible bricks you and your friends have, the larger your building possibilities. • Intellectual Property protection of Lego bricks • Last patents expired in 1978 • Since then, the LEGO Group has zealously guarded its trademarks and other IP rights. • Dozens of lawsuits against competitors • 2005: LEGO failed in its attempt to enforce its trademark for the design of its bricks in the Canadian Supreme Court: ü “The monopoly on the bricks is over, and Mega Bloks and Lego bricks may be interchangeable in the bins of the playrooms of the nation. Dragons, castles and knights may be designed with them, without any distinction. ” © Cambridge University Press 2010 43

Chapter 20 - Review questions • Define direct and indirect network effects, and illustrate with examples. • Explain why there often exist multiple consumer equilibria for a given price of the network industry. • Explain why there is a tendency towards underprovision of a network good by a monopolist, and even by perfectly competitive firms. • Explain why the competition between incompatible network goods is likely to lead, in the long run, to market dominance by a single good. © Cambridge University Press 2010 44

Chapter 20 - Review questions • Define direct and indirect network effects, and illustrate with examples. • Explain why there often exist multiple consumer equilibria for a given price of the network industry. • Explain why there is a tendency towards underprovision of a network good by a monopolist, and even by perfectly competitive firms. • Explain why the competition between incompatible network goods is likely to lead, in the long run, to market dominance by a single good. © Cambridge University Press 2010 44

Chapter 20 - Review questions (cont’d) • Describe what is meant by excess inertia and explain why this situation is more likely to happen in markets with indirect rather than direct network effects and where each user only has incomplete rather than full information about the other users’ preferences. © Cambridge University Press 2010 45

Chapter 20 - Review questions (cont’d) • Describe what is meant by excess inertia and explain why this situation is more likely to happen in markets with indirect rather than direct network effects and where each user only has incomplete rather than full information about the other users’ preferences. © Cambridge University Press 2010 45

Part VIII. Networks, standards and systems Chapter 21. Strategies for network goods Slides Industrial Organization: Markets and Strategies Paul Belleflamme and Martin Peitz © Cambridge University Press 2010

Part VIII. Networks, standards and systems Chapter 21. Strategies for network goods Slides Industrial Organization: Markets and Strategies Paul Belleflamme and Martin Peitz © Cambridge University Press 2010

Chapter 21 - Objectives Chapter 21. Learning objectives • Understand better the decision making on the supply side of network markets. • Analyze how firms choose whether to compete ‘for the market’ or ‘in the market’. • Be able to describe and analyse a number of strategic instruments that firms can resort to in order to win a standards war. • Understand why public interventions are fraught with difficulties in network markets. © Cambridge University Press 2010 47

Chapter 21 - Objectives Chapter 21. Learning objectives • Understand better the decision making on the supply side of network markets. • Analyze how firms choose whether to compete ‘for the market’ or ‘in the market’. • Be able to describe and analyse a number of strategic instruments that firms can resort to in order to win a standards war. • Understand why public interventions are fraught with difficulties in network markets. © Cambridge University Press 2010 47

Chapter 21 - Choosing how to compete • Firms’ choices with respect to compatibility • Simplification • Compatibility is achieved through standardization (i. e. , if firms decide to produce the same good) • Programme • Typology of potential equilibria • More precise characterization using the Katz-Shapiro model. • 2 scenarios ü Asymmetric firms in terms of installed bases ü Symmetric firms but competition from an existing good ( collective switching costs) © Cambridge University Press 2010 48

Chapter 21 - Choosing how to compete • Firms’ choices with respect to compatibility • Simplification • Compatibility is achieved through standardization (i. e. , if firms decide to produce the same good) • Programme • Typology of potential equilibria • More precise characterization using the Katz-Shapiro model. • 2 scenarios ü Asymmetric firms in terms of installed bases ü Symmetric firms but competition from an existing good ( collective switching costs) © Cambridge University Press 2010 48

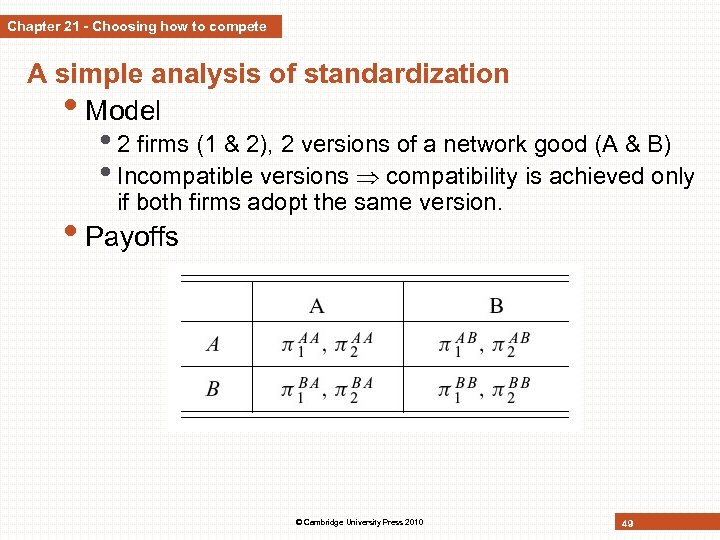

Chapter 21 - Choosing how to compete A simple analysis of standardization • Model • 2 firms (1 & 2), 2 versions of a network good (A & B) • Incompatible versions compatibility is achieved only if both firms adopt the same version. • Payoffs © Cambridge University Press 2010 49

Chapter 21 - Choosing how to compete A simple analysis of standardization • Model • 2 firms (1 & 2), 2 versions of a network good (A & B) • Incompatible versions compatibility is achieved only if both firms adopt the same version. • Payoffs © Cambridge University Press 2010 49

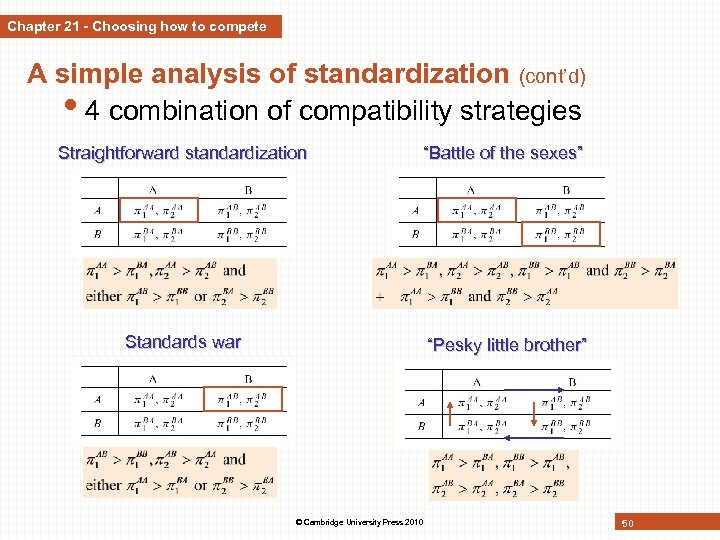

Chapter 21 - Choosing how to compete A simple analysis of standardization (cont’d) • 4 combination of compatibility strategies Straightforward standardization “Battle of the sexes” Standards war “Pesky little brother” © Cambridge University Press 2010 50

Chapter 21 - Choosing how to compete A simple analysis of standardization (cont’d) • 4 combination of compatibility strategies Straightforward standardization “Battle of the sexes” Standards war “Pesky little brother” © Cambridge University Press 2010 50

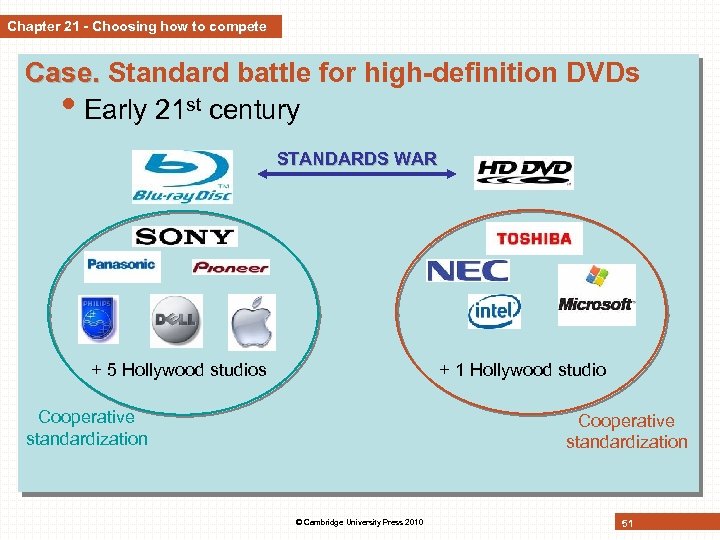

Chapter 21 - Choosing how to compete Case. Standard battle for high-definition DVDs • Early 21 st century STANDARDS WAR + 5 Hollywood studios + 1 Hollywood studio Cooperative standardization © Cambridge University Press 2010 51

Chapter 21 - Choosing how to compete Case. Standard battle for high-definition DVDs • Early 21 st century STANDARDS WAR + 5 Hollywood studios + 1 Hollywood studio Cooperative standardization © Cambridge University Press 2010 51

Chapter 21 - Choosing how to compete Case. Virgin. Mega vs Apple • Digital Right Management (DRM) systems • Enable copyright owners to specify what someone else can do with the copyrighted product. • Distribution of digital music • Apple uses a DRM technology called Fairplay. • Apple keeps Fairplay proprietary. • 2004: Virgin-Mega claimed that Apple was guilty of anticompetitive behaviour by refusing to license its DRM technology. • ‘Pesky Little Brother’ attitude • Ruled to be short of convincing evidence by the French Competition Council. © Cambridge University Press 2010 52

Chapter 21 - Choosing how to compete Case. Virgin. Mega vs Apple • Digital Right Management (DRM) systems • Enable copyright owners to specify what someone else can do with the copyrighted product. • Distribution of digital music • Apple uses a DRM technology called Fairplay. • Apple keeps Fairplay proprietary. • 2004: Virgin-Mega claimed that Apple was guilty of anticompetitive behaviour by refusing to license its DRM technology. • ‘Pesky Little Brother’ attitude • Ruled to be short of convincing evidence by the French Competition Council. © Cambridge University Press 2010 52

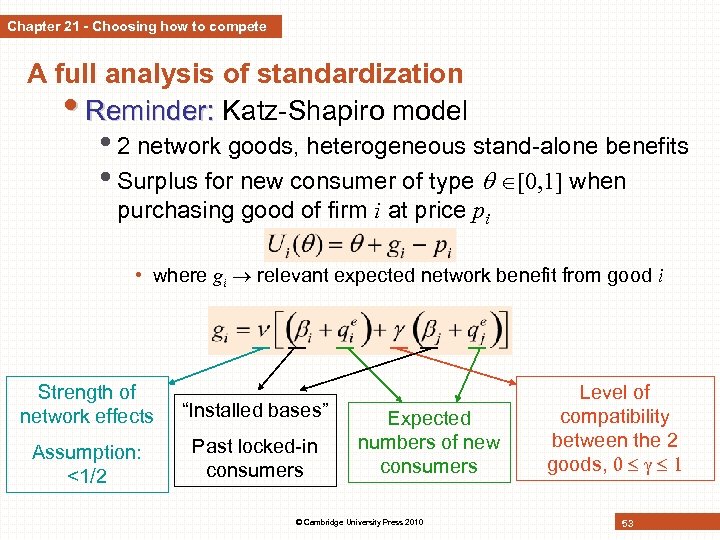

Chapter 21 - Choosing how to compete A full analysis of standardization • Reminder: Katz-Shapiro model • 2 network goods, heterogeneous stand-alone benefits • Surplus for new consumer of type when purchasing good of firm i at price pi • where gi relevant expected network benefit from good i Strength of network effects “Installed bases” Assumption: <1/2 Past locked-in consumers Expected numbers of new consumers © Cambridge University Press 2010 Level of compatibility between the 2 goods, 53

Chapter 21 - Choosing how to compete A full analysis of standardization • Reminder: Katz-Shapiro model • 2 network goods, heterogeneous stand-alone benefits • Surplus for new consumer of type when purchasing good of firm i at price pi • where gi relevant expected network benefit from good i Strength of network effects “Installed bases” Assumption: <1/2 Past locked-in consumers Expected numbers of new consumers © Cambridge University Press 2010 Level of compatibility between the 2 goods, 53

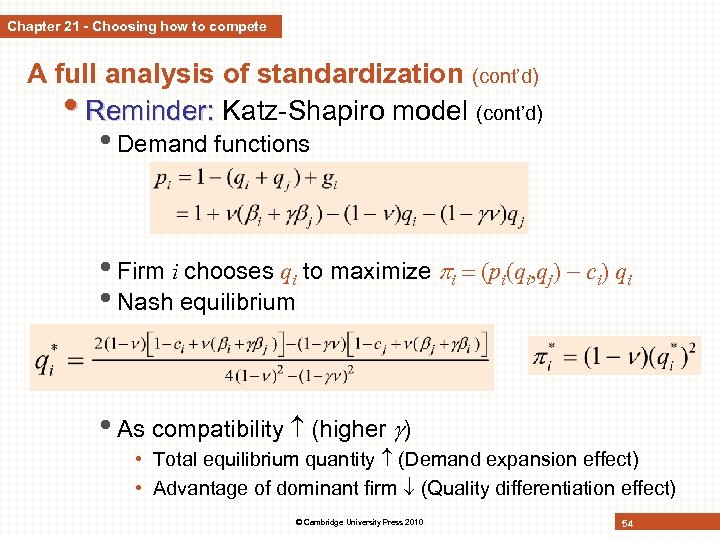

Chapter 21 - Choosing how to compete A full analysis of standardization (cont’d) • Reminder: Katz-Shapiro model (cont’d) • Demand functions • Firm i chooses qi to maximize i (pi(qi, qj) ci) qi • Nash equilibrium • As compatibility (higher ) • Total equilibrium quantity (Demand expansion effect) • Advantage of dominant firm (Quality differentiation effect) © Cambridge University Press 2010 54

Chapter 21 - Choosing how to compete A full analysis of standardization (cont’d) • Reminder: Katz-Shapiro model (cont’d) • Demand functions • Firm i chooses qi to maximize i (pi(qi, qj) ci) qi • Nash equilibrium • As compatibility (higher ) • Total equilibrium quantity (Demand expansion effect) • Advantage of dominant firm (Quality differentiation effect) © Cambridge University Press 2010 54

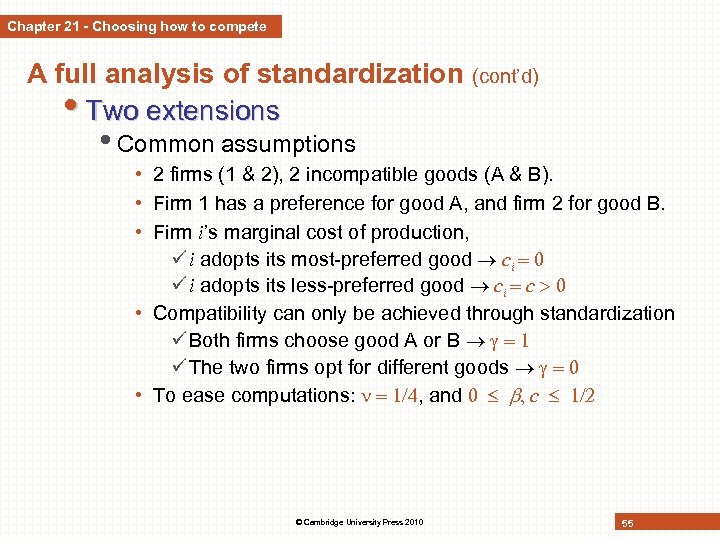

Chapter 21 - Choosing how to compete A full analysis of standardization (cont’d) • Two extensions • Common assumptions • 2 firms (1 & 2), 2 incompatible goods (A & B). • Firm 1 has a preference for good A, and firm 2 for good B. • Firm i’s marginal cost of production, ü i adopts its most-preferred good ci ü i adopts its less-preferred good ci c • Compatibility can only be achieved through standardization ü Both firms choose good A or B ü The two firms opt for different goods • To ease computations: , and c © Cambridge University Press 2010 55

Chapter 21 - Choosing how to compete A full analysis of standardization (cont’d) • Two extensions • Common assumptions • 2 firms (1 & 2), 2 incompatible goods (A & B). • Firm 1 has a preference for good A, and firm 2 for good B. • Firm i’s marginal cost of production, ü i adopts its most-preferred good ci ü i adopts its less-preferred good ci c • Compatibility can only be achieved through standardization ü Both firms choose good A or B ü The two firms opt for different goods • To ease computations: , and c © Cambridge University Press 2010 55

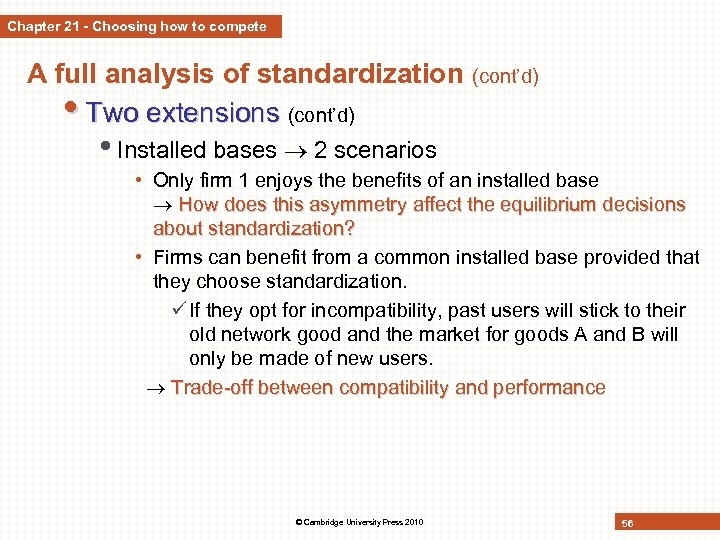

Chapter 21 - Choosing how to compete A full analysis of standardization (cont’d) • Two extensions (cont’d) • Installed bases 2 scenarios • Only firm 1 enjoys the benefits of an installed base How does this asymmetry affect the equilibrium decisions about standardization? • Firms can benefit from a common installed base provided that they choose standardization. ü If they opt for incompatibility, past users will stick to their old network good and the market for goods A and B will only be made of new users. Trade-off between compatibility and performance © Cambridge University Press 2010 56

Chapter 21 - Choosing how to compete A full analysis of standardization (cont’d) • Two extensions (cont’d) • Installed bases 2 scenarios • Only firm 1 enjoys the benefits of an installed base How does this asymmetry affect the equilibrium decisions about standardization? • Firms can benefit from a common installed base provided that they choose standardization. ü If they opt for incompatibility, past users will stick to their old network good and the market for goods A and B will only be made of new users. Trade-off between compatibility and performance © Cambridge University Press 2010 56

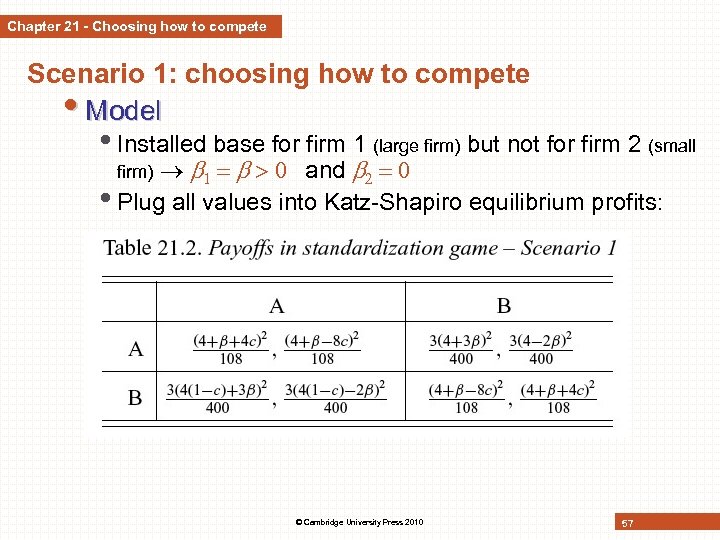

Chapter 21 - Choosing how to compete Scenario 1: choosing how to compete • Model • Installed base for firm 1 (large firm) but not for firm 2 (small and • Plug all values into Katz-Shapiro equilibrium profits: firm) © Cambridge University Press 2010 57

Chapter 21 - Choosing how to compete Scenario 1: choosing how to compete • Model • Installed base for firm 1 (large firm) but not for firm 2 (small and • Plug all values into Katz-Shapiro equilibrium profits: firm) © Cambridge University Press 2010 57

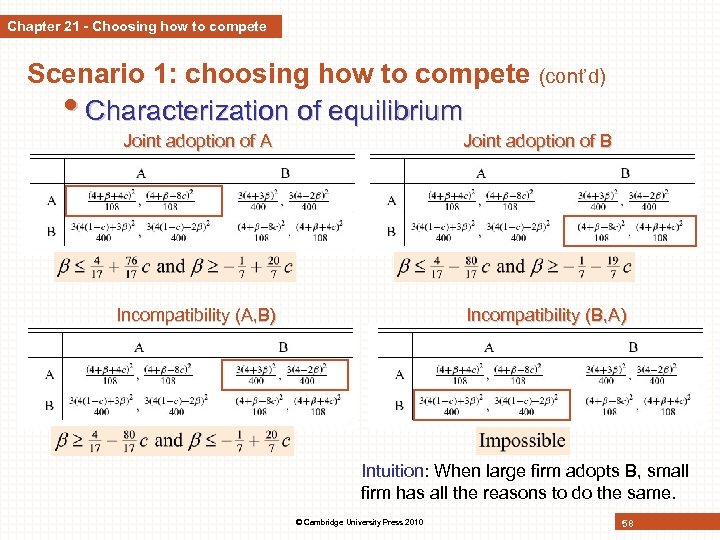

Chapter 21 - Choosing how to compete Scenario 1: choosing how to compete (cont’d) • Characterization of equilibrium Joint adoption of A Joint adoption of B Incompatibility (A, B) Incompatibility (B, A) Intuition: When large firm adopts B, small firm has all the reasons to do the same. © Cambridge University Press 2010 58

Chapter 21 - Choosing how to compete Scenario 1: choosing how to compete (cont’d) • Characterization of equilibrium Joint adoption of A Joint adoption of B Incompatibility (A, B) Incompatibility (B, A) Intuition: When large firm adopts B, small firm has all the reasons to do the same. © Cambridge University Press 2010 58

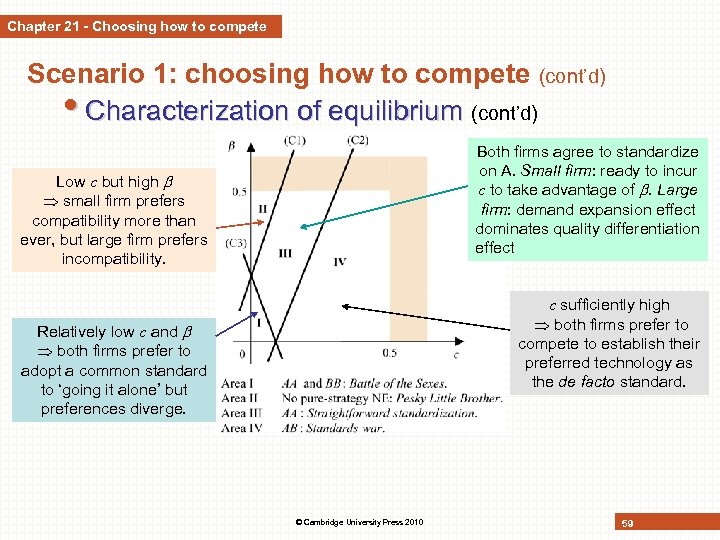

Chapter 21 - Choosing how to compete Scenario 1: choosing how to compete (cont’d) • Characterization of equilibrium (cont’d) Both firms agree to standardize on A. Small firm: ready to incur c to take advantage of . Large firm: demand expansion effect dominates quality differentiation effect Low c but high small firm prefers compatibility more than ever, but large firm prefers incompatibility. c sufficiently high both firms prefer to compete to establish their preferred technology as the de facto standard. Relatively low c and both firms prefer to adopt a common standard to ‘going it alone’ but preferences diverge. © Cambridge University Press 2010 59

Chapter 21 - Choosing how to compete Scenario 1: choosing how to compete (cont’d) • Characterization of equilibrium (cont’d) Both firms agree to standardize on A. Small firm: ready to incur c to take advantage of . Large firm: demand expansion effect dominates quality differentiation effect Low c but high small firm prefers compatibility more than ever, but large firm prefers incompatibility. c sufficiently high both firms prefer to compete to establish their preferred technology as the de facto standard. Relatively low c and both firms prefer to adopt a common standard to ‘going it alone’ but preferences diverge. © Cambridge University Press 2010 59

Chapter 21 - Choosing how to compete Scenario 1: choosing how to compete (cont’d) • Lesson: Pre-market standardization is more likely to emerge as an equilibrium when the parties are relatively symmetric and do not have marked preferences for a particular good. In contrast, a standards war is more likely to emerge as an equilibrium when the parties have marked (and diverging) preferences for a particular good. © Cambridge University Press 2010 60

Chapter 21 - Choosing how to compete Scenario 1: choosing how to compete (cont’d) • Lesson: Pre-market standardization is more likely to emerge as an equilibrium when the parties are relatively symmetric and do not have marked preferences for a particular good. In contrast, a standards war is more likely to emerge as an equilibrium when the parties have marked (and diverging) preferences for a particular good. © Cambridge University Press 2010 60

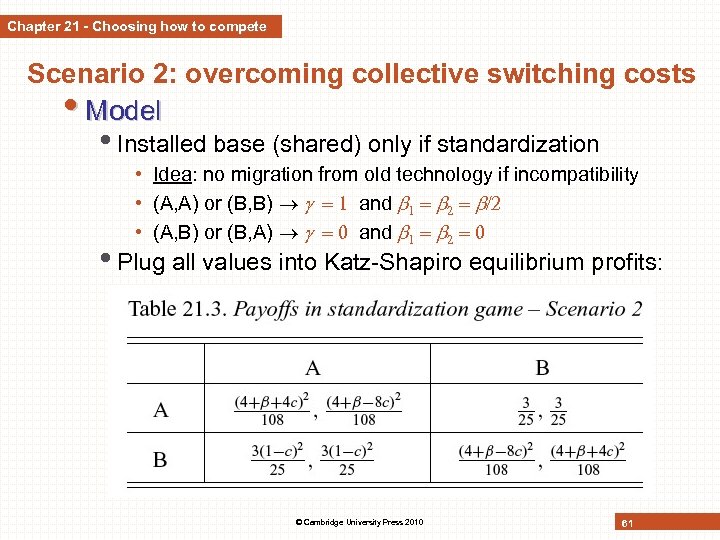

Chapter 21 - Choosing how to compete Scenario 2: overcoming collective switching costs • Model • Installed base (shared) only if standardization • Idea: no migration from old technology if incompatibility • (A, A) or (B, B) and • (A, B) or (B, A) and • Plug all values into Katz-Shapiro equilibrium profits: © Cambridge University Press 2010 61

Chapter 21 - Choosing how to compete Scenario 2: overcoming collective switching costs • Model • Installed base (shared) only if standardization • Idea: no migration from old technology if incompatibility • (A, A) or (B, B) and • (A, B) or (B, A) and • Plug all values into Katz-Shapiro equilibrium profits: © Cambridge University Press 2010 61

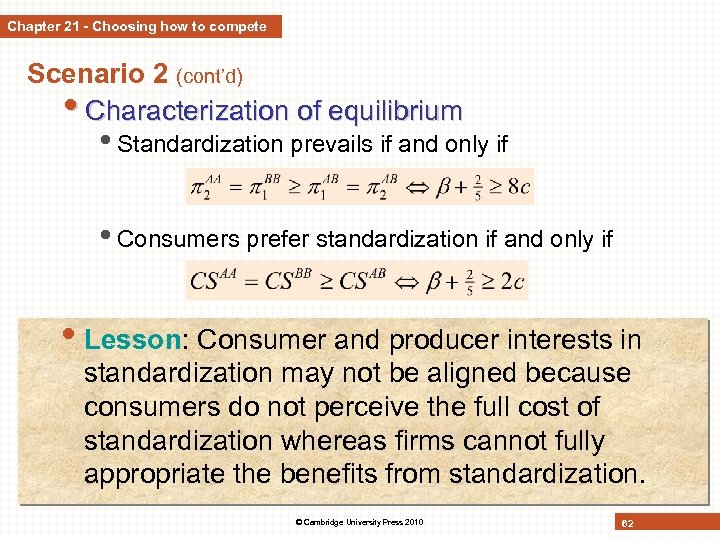

Chapter 21 - Choosing how to compete Scenario 2 (cont’d) • Characterization of equilibrium • Standardization prevails if and only if • Consumers prefer standardization if and only if • Lesson: Consumer and producer interests in standardization may not be aligned because consumers do not perceive the full cost of standardization whereas firms cannot fully appropriate the benefits from standardization. © Cambridge University Press 2010 62

Chapter 21 - Choosing how to compete Scenario 2 (cont’d) • Characterization of equilibrium • Standardization prevails if and only if • Consumers prefer standardization if and only if • Lesson: Consumer and producer interests in standardization may not be aligned because consumers do not perceive the full cost of standardization whereas firms cannot fully appropriate the benefits from standardization. © Cambridge University Press 2010 62

Chapter 21 - Strategies in standards wars Strategies in network markets • 2 specificities • Firms have to factor in network effects in the formation of their strategies. • Multiple equilibria on the demand side • Self-reinforcing effects • Firms also develop specific strategic instruments • Strategic choice of compatibility • Building an early installed base to preempt rivals • Entry on network markets ü Trade-off between compatibility and performance • Expectations management © Cambridge University Press 2010 63

Chapter 21 - Strategies in standards wars Strategies in network markets • 2 specificities • Firms have to factor in network effects in the formation of their strategies. • Multiple equilibria on the demand side • Self-reinforcing effects • Firms also develop specific strategic instruments • Strategic choice of compatibility • Building an early installed base to preempt rivals • Entry on network markets ü Trade-off between compatibility and performance • Expectations management © Cambridge University Press 2010 63

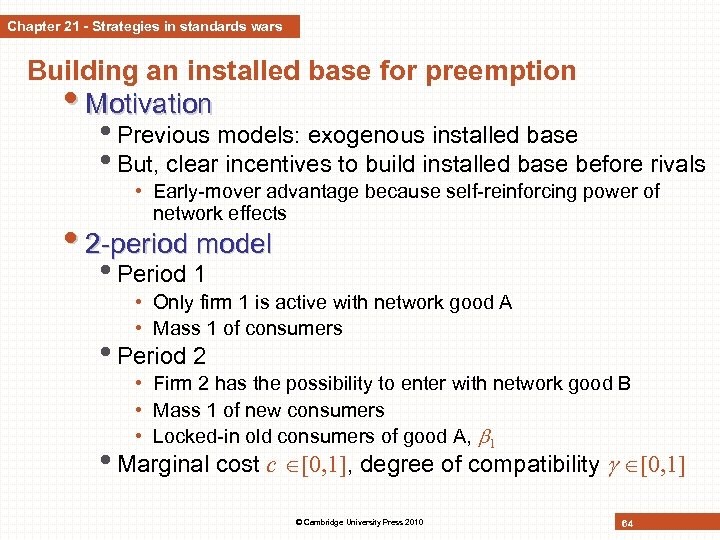

Chapter 21 - Strategies in standards wars Building an installed base for preemption • Motivation • Previous models: exogenous installed base • But, clear incentives to build installed base before rivals • Early-mover advantage because self-reinforcing power of network effects • 2 -period model • Period 1 • Only firm 1 is active with network good A • Mass 1 of consumers • Period 2 • Firm 2 has the possibility to enter with network good B • Mass 1 of new consumers • Locked-in old consumers of good A, • Marginal cost c , degree of compatibility © Cambridge University Press 2010 64

Chapter 21 - Strategies in standards wars Building an installed base for preemption • Motivation • Previous models: exogenous installed base • But, clear incentives to build installed base before rivals • Early-mover advantage because self-reinforcing power of network effects • 2 -period model • Period 1 • Only firm 1 is active with network good A • Mass 1 of consumers • Period 2 • Firm 2 has the possibility to enter with network good B • Mass 1 of new consumers • Locked-in old consumers of good A, • Marginal cost c , degree of compatibility © Cambridge University Press 2010 64

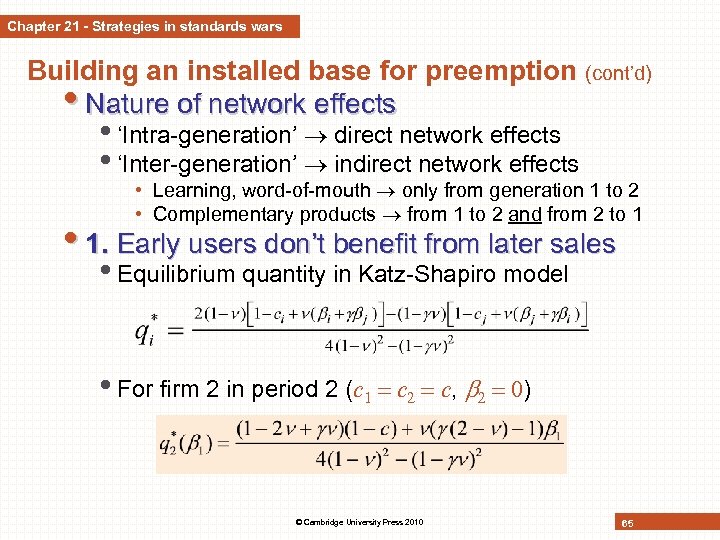

Chapter 21 - Strategies in standards wars Building an installed base for preemption • Nature of network effects (cont’d) • ‘Intra-generation’ direct network effects • ‘Inter-generation’ indirect network effects • Learning, word-of-mouth only from generation 1 to 2 • Complementary products from 1 to 2 and from 2 to 1 • 1. Early users don’t benefit from later sales • Equilibrium quantity in Katz-Shapiro model • For firm 2 in period 2 (c 1 c 2 c, ) © Cambridge University Press 2010 65

Chapter 21 - Strategies in standards wars Building an installed base for preemption • Nature of network effects (cont’d) • ‘Intra-generation’ direct network effects • ‘Inter-generation’ indirect network effects • Learning, word-of-mouth only from generation 1 to 2 • Complementary products from 1 to 2 and from 2 to 1 • 1. Early users don’t benefit from later sales • Equilibrium quantity in Katz-Shapiro model • For firm 2 in period 2 (c 1 c 2 c, ) © Cambridge University Press 2010 65

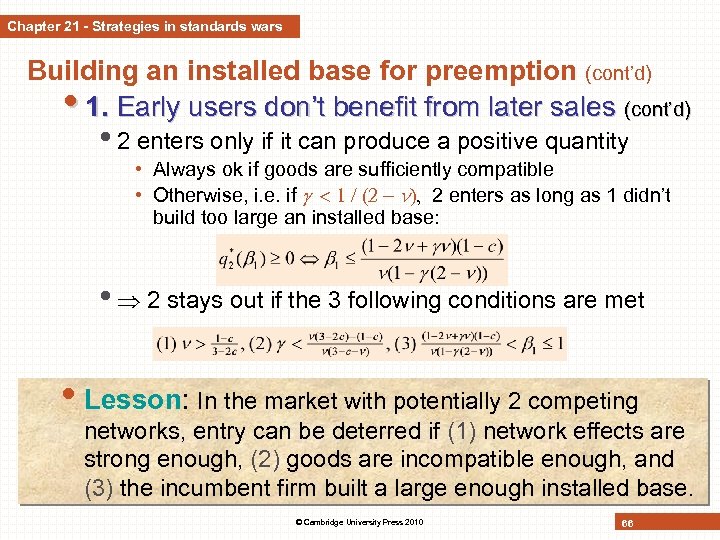

Chapter 21 - Strategies in standards wars Building an installed base for preemption (cont’d) • 1. Early users don’t benefit from later sales (cont’d) • 2 enters only if it can produce a positive quantity • Always ok if goods are sufficiently compatible • Otherwise, i. e. if 2 enters as long as 1 didn’t build too large an installed base: • 2 stays out if the 3 following conditions are met • Lesson: In the market with potentially 2 competing networks, entry can be deterred if (1) network effects are strong enough, (2) goods are incompatible enough, and (3) the incumbent firm built a large enough installed base. © Cambridge University Press 2010 66

Chapter 21 - Strategies in standards wars Building an installed base for preemption (cont’d) • 1. Early users don’t benefit from later sales (cont’d) • 2 enters only if it can produce a positive quantity • Always ok if goods are sufficiently compatible • Otherwise, i. e. if 2 enters as long as 1 didn’t build too large an installed base: • 2 stays out if the 3 following conditions are met • Lesson: In the market with potentially 2 competing networks, entry can be deterred if (1) network effects are strong enough, (2) goods are incompatible enough, and (3) the incumbent firm built a large enough installed base. © Cambridge University Press 2010 66

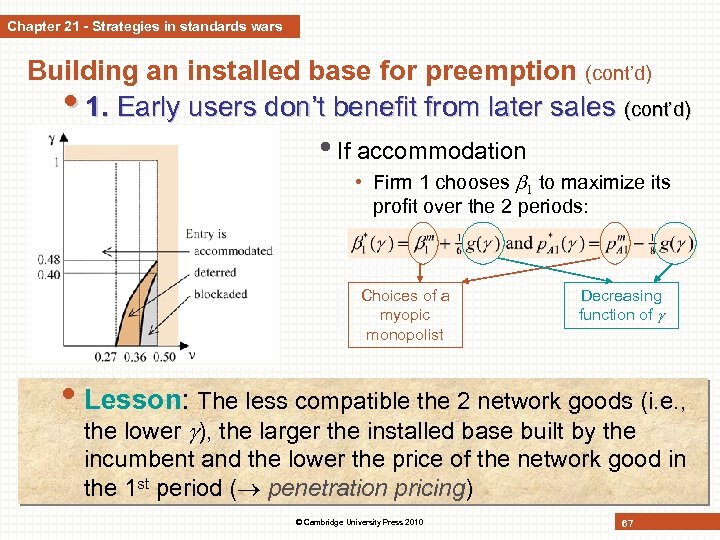

Chapter 21 - Strategies in standards wars Building an installed base for preemption (cont’d) • 1. Early users don’t benefit from later sales (cont’d) • If accommodation • Firm 1 chooses to maximize its profit over the 2 periods: Choices of a myopic monopolist Decreasing function of • Lesson: The less compatible the 2 network goods (i. e. , the lower ), the larger the installed base built by the incumbent and the lower the price of the network good in the 1 st period ( penetration pricing) © Cambridge University Press 2010 67

Chapter 21 - Strategies in standards wars Building an installed base for preemption (cont’d) • 1. Early users don’t benefit from later sales (cont’d) • If accommodation • Firm 1 chooses to maximize its profit over the 2 periods: Choices of a myopic monopolist Decreasing function of • Lesson: The less compatible the 2 network goods (i. e. , the lower ), the larger the installed base built by the incumbent and the lower the price of the network good in the 1 st period ( penetration pricing) © Cambridge University Press 2010 67

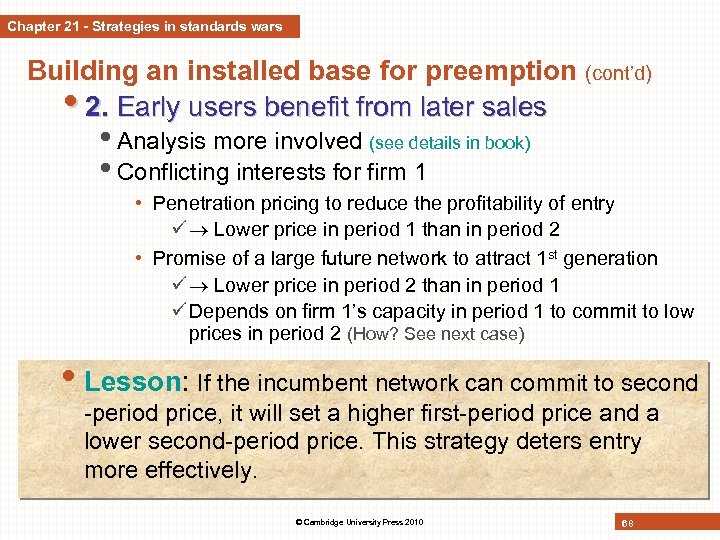

Chapter 21 - Strategies in standards wars Building an installed base for preemption • 2. Early users benefit from later sales (cont’d) • Analysis more involved (see details in book) • Conflicting interests for firm 1 • Penetration pricing to reduce the profitability of entry ü Lower price in period 1 than in period 2 • Promise of a large future network to attract 1 st generation ü Lower price in period 2 than in period 1 ü Depends on firm 1’s capacity in period 1 to commit to low prices in period 2 (How? See next case) • Lesson: If the incumbent network can commit to second -period price, it will set a higher first-period price and a lower second-period price. This strategy deters entry more effectively. © Cambridge University Press 2010 68

Chapter 21 - Strategies in standards wars Building an installed base for preemption • 2. Early users benefit from later sales (cont’d) • Analysis more involved (see details in book) • Conflicting interests for firm 1 • Penetration pricing to reduce the profitability of entry ü Lower price in period 1 than in period 2 • Promise of a large future network to attract 1 st generation ü Lower price in period 2 than in period 1 ü Depends on firm 1’s capacity in period 1 to commit to low prices in period 2 (How? See next case) • Lesson: If the incumbent network can commit to second -period price, it will set a higher first-period price and a lower second-period price. This strategy deters entry more effectively. © Cambridge University Press 2010 68

Chapter 21 - Strategies in standards wars Case. The VCR standards war • 2 formats for video cassette recorders (VCR) • Beta (sponsored by Sony) & VHS (sponsored by JVC) • Importance of commitment in the standards war • 1976: Start of the market, Beta dominates 1976 • Sony started production on a very large scale. • Motivation: to commit credibly to lower future prices by immediately sinking part of the production costs. • 1980: VHS installed base becomes larger in the US 1980 • JVC had formed a large group of allies, aggressively pursuing licensing agreements. • Motivation: guarantee mass production and lower prices for the technology in the future. • 1989: Beta exits the consumer market. 1989 © Cambridge University Press 2010 69

Chapter 21 - Strategies in standards wars Case. The VCR standards war • 2 formats for video cassette recorders (VCR) • Beta (sponsored by Sony) & VHS (sponsored by JVC) • Importance of commitment in the standards war • 1976: Start of the market, Beta dominates 1976 • Sony started production on a very large scale. • Motivation: to commit credibly to lower future prices by immediately sinking part of the production costs. • 1980: VHS installed base becomes larger in the US 1980 • JVC had formed a large group of allies, aggressively pursuing licensing agreements. • Motivation: guarantee mass production and lower prices for the technology in the future. • 1989: Beta exits the consumer market. 1989 © Cambridge University Press 2010 69

Chapter 21 - Strategies in standards wars Backward compatibility and performance • Trade-off • Backward compatibility as a way to ease entry and overcome collective switching costs. • But, restricts the potential for horizontal and vertical differentiation. Case. Drupal backward compatible? “Unfortunately, there is no right or wrong answer here: there are both advantages and disadvantages to backward compatibility. As a result, there will always be a tension between the need for hassle-free upgrades and the desire to have fast, cruft-free code with clean and flexible APIs. At the end of the day, we can’t make everybody happy and it is very important that you realize that. ” (Dries Buytaert, lead of the Drupal Project, an open source content management platform) © Cambridge University Press 2010 70

Chapter 21 - Strategies in standards wars Backward compatibility and performance • Trade-off • Backward compatibility as a way to ease entry and overcome collective switching costs. • But, restricts the potential for horizontal and vertical differentiation. Case. Drupal backward compatible? “Unfortunately, there is no right or wrong answer here: there are both advantages and disadvantages to backward compatibility. As a result, there will always be a tension between the need for hassle-free upgrades and the desire to have fast, cruft-free code with clean and flexible APIs. At the end of the day, we can’t make everybody happy and it is very important that you realize that. ” (Dries Buytaert, lead of the Drupal Project, an open source content management platform) © Cambridge University Press 2010 70

Chapter 21 - Strategies in standards wars Backward compatibility and performance (cont’d) • Model • Same 2 -period model as before • Only firm 1 is active in period 1; it produces at cost c 1 c ; it builds an installed base of users (locked in period 2) • Firm 2 can enter in period 2. • New feature • Firm 2 can choose the degree of compatibility, , between its network good (B) and firm 1’s network good (A) • Conflicting effects of larger compatibility • Easier entry ü 2 benefits more from 1’s installed base • Higher production costs ü Assumption: c 2 c ü 2’s cost advantage with © Cambridge University Press 2010 71

Chapter 21 - Strategies in standards wars Backward compatibility and performance (cont’d) • Model • Same 2 -period model as before • Only firm 1 is active in period 1; it produces at cost c 1 c ; it builds an installed base of users (locked in period 2) • Firm 2 can enter in period 2. • New feature • Firm 2 can choose the degree of compatibility, , between its network good (B) and firm 1’s network good (A) • Conflicting effects of larger compatibility • Easier entry ü 2 benefits more from 1’s installed base • Higher production costs ü Assumption: c 2 c ü 2’s cost advantage with © Cambridge University Press 2010 71

Chapter 21 - Strategies in standards wars Backward compatibility and performance (cont’d) • Resolution • Key variable: c difference between • ‘installed-base effect’ of full compatibility • ‘performance effect’ of full incompatibility • Optimal compatibility choice (see details in book) • full compatibility • full incompatibility • Lesson: A firm that enters a network market with a superior product makes this product incompatible with the competitor’s existing inferior product only if what it gains by selling a higher-quality product is sufficiently larger than what it loses by not being compatible with the incumbent’s installed base. © Cambridge University Press 2010 72

Chapter 21 - Strategies in standards wars Backward compatibility and performance (cont’d) • Resolution • Key variable: c difference between • ‘installed-base effect’ of full compatibility • ‘performance effect’ of full incompatibility • Optimal compatibility choice (see details in book) • full compatibility • full incompatibility • Lesson: A firm that enters a network market with a superior product makes this product incompatible with the competitor’s existing inferior product only if what it gains by selling a higher-quality product is sufficiently larger than what it loses by not being compatible with the incumbent’s installed base. © Cambridge University Press 2010 72

Chapter 21 - Strategies in standards wars Expectations management • Intuition • Expectations are crucial in network markets. • They may determine the outcome of standards wars. • Firms want to manipulate expectations in their favour. • How? • Advertising about the size of the network • May become self-fulfilling if successful. See Case 21. 6 about high-definition DVDs • ‘Fear Uncertainty and Doubt (FUD)’ • Disseminate negative information about rival products to generate pessimistic expectations. See Case 21. 7 about Microsoft’s ‘cereal box’ ad campaign against Novell • Product preannouncement • Announce a new product well in advance of actual market availability to freeze sales of competing existing products • If not credible: ‘vaporware’ © Cambridge University Press 2010 73

Chapter 21 - Strategies in standards wars Expectations management • Intuition • Expectations are crucial in network markets. • They may determine the outcome of standards wars. • Firms want to manipulate expectations in their favour. • How? • Advertising about the size of the network • May become self-fulfilling if successful. See Case 21. 6 about high-definition DVDs • ‘Fear Uncertainty and Doubt (FUD)’ • Disseminate negative information about rival products to generate pessimistic expectations. See Case 21. 7 about Microsoft’s ‘cereal box’ ad campaign against Novell • Product preannouncement • Announce a new product well in advance of actual market availability to freeze sales of competing existing products • If not credible: ‘vaporware’ © Cambridge University Press 2010 73

Chapter 21 - Public policy in network markets • Network effects create market failures • Users may coordinate on inferior standards. • Firms may provide lower compatibility than socially optimal. • Can public intervention correct (alleviate) them? • 2 types of public interventions • Ex ante interventions • Public authorities take an active part in the competition process among network goods, before standardization takes place. • Ex post interventions • Public authorities don’t try to influence the competition process, but aim at safeguarding it by controlling firms’ conduct. • Both types are fraught with major difficulties. © Cambridge University Press 2010 74

Chapter 21 - Public policy in network markets • Network effects create market failures • Users may coordinate on inferior standards. • Firms may provide lower compatibility than socially optimal. • Can public intervention correct (alleviate) them? • 2 types of public interventions • Ex ante interventions • Public authorities take an active part in the competition process among network goods, before standardization takes place. • Ex post interventions • Public authorities don’t try to influence the competition process, but aim at safeguarding it by controlling firms’ conduct. • Both types are fraught with major difficulties. © Cambridge University Press 2010 74

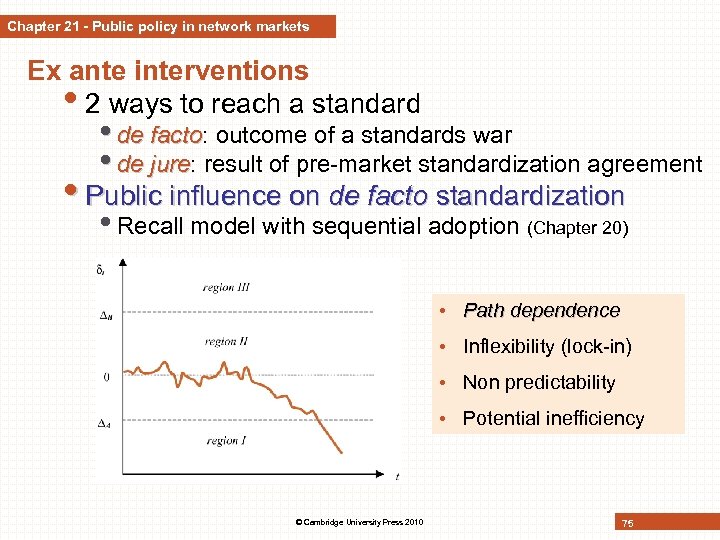

Chapter 21 - Public policy in network markets Ex ante interventions • 2 ways to reach a standard • de facto: outcome of a standards war facto • de jure: result of pre-market standardization agreement jure • Public influence on de facto standardization • Recall model with sequential adoption (Chapter 20) • Path dependence • Inflexibility (lock-in) • Non predictability • Potential inefficiency © Cambridge University Press 2010 75

Chapter 21 - Public policy in network markets Ex ante interventions • 2 ways to reach a standard • de facto: outcome of a standards war facto • de jure: result of pre-market standardization agreement jure • Public influence on de facto standardization • Recall model with sequential adoption (Chapter 20) • Path dependence • Inflexibility (lock-in) • Non predictability • Potential inefficiency © Cambridge University Press 2010 75

Chapter 21 - Public policy in network markets Ex ante interventions (cont’d) • Public influence on de facto standardization (cont’d) • Path-dependence 3 generic problems (David, 1987) • Narrow Policy Window Paradox • “Window” for effective intervention: by influencing 1 st users (by taxes/subsidies), it is possible to influence the whole process. • But the window may close very quickly. • Blind Giant's Quandary • Limited information during the window of intervention • Possible strategy: "counter-action" ü Handicap the leader and favour other network goods that remain behind in the competition for the market. • Angry Technological Orphans • Counter-action is socially costly ü Some network effects are not exploited. ü Creation of “angry technological orphans” © Cambridge University Press 2010 76

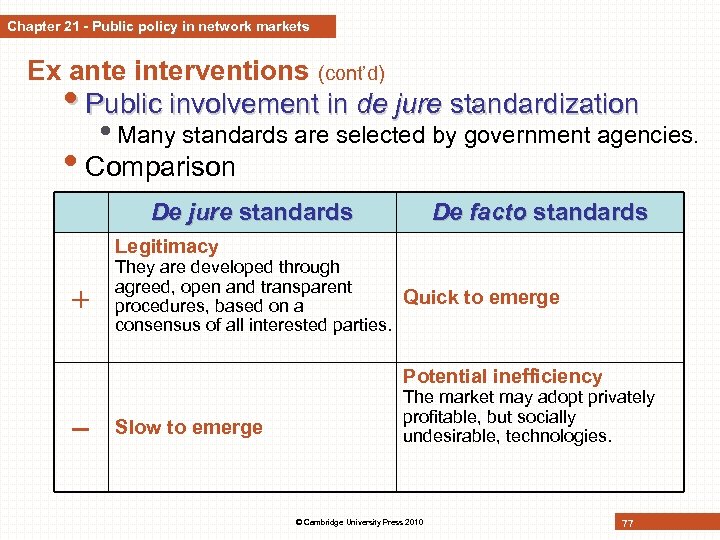

Chapter 21 - Public policy in network markets Ex ante interventions (cont’d) • Public influence on de facto standardization (cont’d) • Path-dependence 3 generic problems (David, 1987) • Narrow Policy Window Paradox • “Window” for effective intervention: by influencing 1 st users (by taxes/subsidies), it is possible to influence the whole process. • But the window may close very quickly. • Blind Giant's Quandary • Limited information during the window of intervention • Possible strategy: "counter-action" ü Handicap the leader and favour other network goods that remain behind in the competition for the market. • Angry Technological Orphans • Counter-action is socially costly ü Some network effects are not exploited. ü Creation of “angry technological orphans” © Cambridge University Press 2010 76