9da24f0a7a3e2c360aff0ec1588fdc5e.ppt

- Количество слайдов: 34

Part IV. Renewable Resources A. Fish – part 2: Policy B. Forests C. Water D. Biodiversity 1

Current Fishery Policy • This section will focus on 2 approaches to policy. 1. Those policies that can actually address the issue of entry are termed “limited-entry” techniques. 2. All other regulations or policies that do not explicitly address the problem of entry are termed “open-access” (OA) techniques. • • OA techniques modify fishing behavior of those participants in the fishery without directly affecting participation in the fishery, and typically raise the cost associated with fishing. Analogous to C & C 2

OA regulations – how to catch • OA regulations are designed to maintain the stocks at some target level, usually stocks consistent with MSY. • Because modern technology can give a fishing fleet tremendous fishing power relative to the size of a fish population, OA regulation generally forces inefficiency on the fishers. • In Maryland's share of the Chesapeake, it is illegal to dredge for oysters under motorized power. This means sails, smaller dredging equipment, and slower movement across the oyster beds. 3

OA regulations – who to catch • Regulation which revolves around restrictions on the minimum size of fish that are legal to harvest are designed to leave a portion of the fish stock in the water to provide a sufficient breeding stock to ensure future populations. • Fishers generally implement this restriction by choosing a mesh size for their nets that allows smaller, illegal fish, to escape. 4

OA regulations – when to catch • Because fishing activity may disrupt the spawning process, often the fishing season is closed for a certain period on an annual basis, generally during spawning season. • Also, some species become so extremely congregated during spawning that fishing effort could capture virtually the entire population. 5

OA regulations – where to catch • Regulations on where fish may be caught are designed to protect fish stocks when they are congregated and vulnerable to overharvesting. • These types of regulations also protect vulnerable fishing habitats from destruction by the fishing process. 6

OA regulations – how many to catch • Often, OA regulations take the form of limits on how many fish may be captured in a given time period. • These limits may be in the form of weight caught, number of fish, or volume of catch. • The catch limit on giant bluefin tuna is 1 fish per boat. A fish can often weigh as much as 1000 pounds and the market price has been $18 per pound. 7

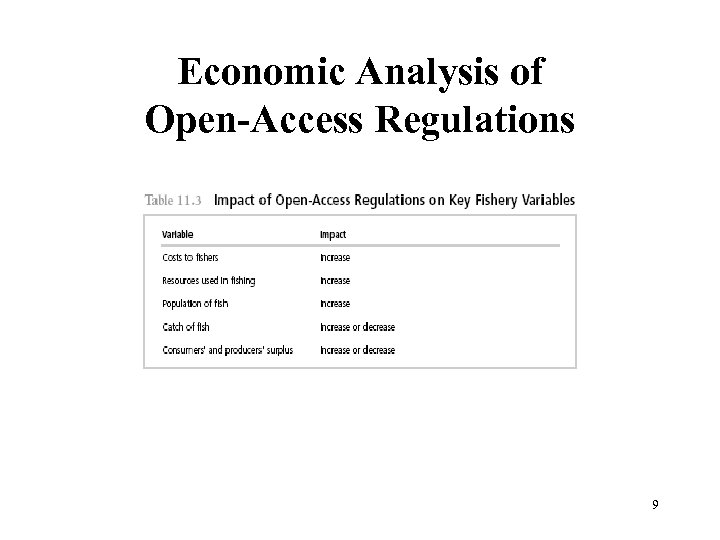

Economic Analysis of Open-Access Regulations • The effect of OA regulation falls has 2 effects: 1. increase in cost due to regulations 2. possible decrease in cost due to higher catch per effort expended. • Net effect increased costs • Table 11. 3 summarizes the impact of the OA regulations on key variables in the fishery. 8

Economic Analysis of Open-Access Regulations 9

Limited Entry Techniques • Limited entry techniques raise the cost for fishers without increasing social costs. • If limited entry techniques are truly analogous to economic incentives for pollution control, then they should be available either as price policies (tax) or quantity policies (MPP). • Fisheries economics literature tends to focus on quantitybased systems. • The name for these systems is individual transferable quotas (ITQs). 10

Catch based ITQs • ITQs would work in a fashion similar to marketable pollution permits. • Limit placed on total catch, each fisher allocated portion of total catch • Limits effort because cost of effort increases, because people must now buy ITQs to fish • Cost increase serves to eliminate disparity between social and private cost of fishing associated with the OA externality 11

Effort based ITQs • Limited entry techniques structured to direct effort rather than catch can also be developed. • Here only a fixed number of boats would be allowed to operate in the fishery, must have permit be to allowed in • The method of permit allocation could be by auction or historical presence in the fishery. • Completely analogous to MPP’s 12

Transferable ITQs • If these ITQs are transferable, it will be possible to have only the most efficient fisherman in the fishery. • Enforcement of effort-based limits, that is vessel permits, would be much easier than that associated with the catch limits. • No measuring or weighing is necessary; a poster sized certificate of operation would allow easy identification of legal vessels. 13

ITQ problems • Catch-based ITQs are subject to several problems. • People might cheat on their quota by selling to foreign vessels or in an underground market. • Another problem is associated with the differing market values of different size fish. • Once quota is reached, throw less valuable (but now dead) fish overboard to make room for better catch 14

Private oyster beds • Although most fishery regulation relies on OA techniques, an important example of a limited entry technique is the Virginia oyster fishery, where oyster beds are treated as private property. • Eliminates OA exploitation • It gives oyster bed operators incentive to invest in their property such as seeding with larval oysters and creating more structures to which the oysters 15 can attach.

EEZ • An additional example of the limited entry regulation is the economic exclusion zone, established under the authority of the United Nations Convention of the Law of the Sea. • This regulation established a 200 mile limit along the coast of a country where each country has the right to limit access to their waters. This is a partial limited access regulation. 16

Why We Do Not See More Limits to Entry • First, many limits to access are informal. • Fishing communities tend to be close knit and generally resistant to outsiders. • It is difficult to enter into these fisheries without facing barriers and possible sabotage of equipment. • Second, fisherman opposition to the idea of limited entry is high. 17

Why We Do Not See More Limits to Entry • A possible explanation for the opposition to limited entry among current fishers is that these fishers may be utility maximizers rather than profit maximizers. • Pure profit maximizers would see the potential economic rents associated with limited entry, and most would probably support limits to entry in order to obtain these potential rents. • Fishers from communities that have fished for generations fit this category. 18

Why We Do Not See More Limits to Entry • Need to reduce catch today in order to expand fish stock, catch and income in the future. • The desire to support fishing families in the present may result in opposition of limited entry policies. • The greater the uncertainty about the success of limited entry policies to enhance future value in the fishery, the greater the chance fishers will not support the policies. 19

Aquaculture • Aquaculture, the cultivation of fish in artificial environments or in contained natural environments, is often suggested as a means of dealing with the OA problem. • Not all species can be cultivated. • Shellfish are ideal because of their inherent immobility. • Wildfish will only benefit indirectly from aquaculture if the “farmed” species takes part of the market demand for the wildfish and therefore reduces the fishing pressure on the species. 20

Aquaculture’s problems • Aquaculture creates its own set of problems. • Communities and industries that are based on wild fisheries could suffer economic setbacks from the decline in demand for wild fish (as consumers choose aquaculture). 21

Aquaculture’s problems • Aquaculture can severely damage the environment. • Shrimp aquaculture in Central and South America has resulted in a loss of mangrove forests, excess nutrient loading into estuaries and severely reduced dissolved oxygen in areas bordering estuaries. • There also potential problems associated with hybridized fish escaping and damaging the gene pool of existing species. 22

Other Issues in Fishery Management • Other problems associated with fishery management include: – incidental catch; – destruction of habitat through fishing activities; – destruction of wetlands and related habitat through nonfishing activities; – pollution of fishery habitat; – conflicts between user groups and – international cooperation concerning the harvesting of migratory species. 23

Incidental catch • Often the fisher will catch not only the species that they seek but also other species, referred to as incidental catch. • Many types of fishing gear do not discriminate among fish species, and both the desired species and a spectrum of untargeted species are caught by this gear. • Among the most notorious of these are the gill nets, whose lengths often measured in miles. • These nets are vertically suspended in the water, like underwater fences, ensnaring the gill covers of fish as they 24 attempt to back out.

Long Lines • Another indiscriminate fishing method is “long-lining. ” • A long-line consists of line that may be 10 km in length or longer, with baited hooks every several meters. • These lines are employed off the Atlantic coast in pursuit of highly profitable swordfish. • Because sharks are often caught, these long-lines have been an important factor in the decline of the shark populations. 25

Policy • Due to the difficulties of monitoring, restrictions on fishing methods may be preferential to policies based on economic incentives. • An example of this type of policy is the requirement that shrimpers install a Turtle Excluder Device (TED) in their nets to allow endangered sea turtles to escape. • In addition to the turtles which are “kicked” out of the shrimp net, non-targeted fish are also allowed to escape. 26

Policy • Whether policy makers should implement the restrictions on gill nets and long-line operations needs to be determined on a case-by-case basis for each potential restriction. • The benefits of protecting untargeted species are spread out over a large number of people, but the costs are concentrated upon a very few. 27

Destruction of Habitat • Damage can occur when contact of fishing gear with the floor of the estuary or ocean uproots aquatic plants, breaks coral, dislodges shell fish, and so on. • One particularly sensitive ecosystem is that associated with a coral reef, where anchors and boat bottoms dragging across the coral can kill it. • Even more destructive is the practice of fishing using explosions or the use of cyanide in the coral to stun and collect fish for consumption and aquariums. 28

Destruction of Habitat • Other habitats such as upland coastal wetlands, temperate forests and free flowing rivers are critically important to fisheries. • The temperate rainforests of the Pacific Northwest are critically important to maintaining the riverine habitat, which is essential to anadromous fish, such as salmon and steelhead. • Any activity which impacts the quality of these ecosystems can impact the quality of the riverine system and the salmon and steelhead. 29

Pollution of Fishery Habitat • This pollution and loss of habitat has affected virtually every freshwater species, and many saltwater species, where saltwater species are affected by estuarine pollution. • Anadromous species such as salmon, steelhead, shad, and striped bass are particularly vulnerable to riverine pollution. • In developing countries, soil erosion from deforestation and intensive cultivation of hillside lands has severely impacted water quality not only in the rivers, but in reservoirs, estuaries, lagoons, and coral reefs. 30

Management of Recreational Fishery Resources • Limits on the number of fish that may be kept, restricted seasons, and size limits. • By stocking fish, where a very large number of fish are hatched, grown to size, and released into the wild, the problem of OA is addressed by increasing resource base. • Often have closed seasons timed to coincide with spawning periods in the fishery. • Access improvements such as launching ramps, fishing piers, parking areas, and artificial reefs can be designed to 31 reduce congestion in the fishery, but may also lead to increased use.

Management of Recreational Fishery Resources • Catch & release programs are based on the idea that a recreational angler does not have to kill his or her catch to produce utility from fishing. • Size limits place restrictions on the minimum (and sometimes maximum) size of fish that are legal to keep. • Creel limits place restrictions on the maximum number of fish per day that may be kept. • Both restrictions are designed to protect the reproductive viability of the fish stocks. 32

Management of Recreational Fishery Resources • In order to find the benefits associated with a particular recreational fishing activity, a valuation study must be done. Usually CV or travel cost studies. • Freeman (1979) and many others note that the major benefit of improving water quality can be attributed to recreational uses of water resources, including boating, swimming, and recreational fishing. 33

Summary • Fishery resources are renewable but destructible. • The destructibility problem is amplified by the open-access nature of many of the world’s fishery resources. • For commercial fishing, optimal management strategy requires the limitation of effort to a level that maximizes the sum of CS, PS, and fishery rent. • Actual fishery management seldom achieves this goal and is based on developing restrictions on how, when, where, and how much fish can be caught. 34

9da24f0a7a3e2c360aff0ec1588fdc5e.ppt