f9b4795b8aba30a12b489048f3156acf.ppt

- Количество слайдов: 25

Part IV. Pricing strategies and market segmentation Chapter 10. Intertemporal price discrimination Slides Industrial Organization: Markets and Strategies Paul Belleflamme and Martin Peitz © Cambridge University Press 2009

Part IV. Pricing strategies and market segmentation Chapter 10. Intertemporal price discrimination Slides Industrial Organization: Markets and Strategies Paul Belleflamme and Martin Peitz © Cambridge University Press 2009

Chapter 10 - Objectives Chapter 10. Learning objectives • Understand the peculiarities of durable goods. • Analyze how a firm sets the price of a durable good at different periods of time. • Is intertemporal price discrimination profitable? • Be able to explain why the answer to the previous question crucially depends on the possibility to commit to future prices and on the number of consumers. • Understand the practice of behaviour-based price discrimination, and its implications for firms and consumers. © Cambridge University Press 2010 2

Chapter 10 - Objectives Chapter 10. Learning objectives • Understand the peculiarities of durable goods. • Analyze how a firm sets the price of a durable good at different periods of time. • Is intertemporal price discrimination profitable? • Be able to explain why the answer to the previous question crucially depends on the possibility to commit to future prices and on the number of consumers. • Understand the practice of behaviour-based price discrimination, and its implications for firms and consumers. © Cambridge University Press 2010 2

Chapter 10 - Durable goods • Main features • Firms offer the same product in different periods. • Consumers buy only 1 item over the whole horizon. • Benefits are derived over a number of periods. • Consumers can decide on the timing of their purchase. • car, washing machine, computer, software, . . . • By analogy, items that can be ordered in advance • holiday package, plane ticket, concert ticket, . . . • Main question • Selling at various points in time opens up the possibility of intertemporal price discrimination • Is it a profitable option for the firm? © Cambridge University Press 2010 3

Chapter 10 - Durable goods • Main features • Firms offer the same product in different periods. • Consumers buy only 1 item over the whole horizon. • Benefits are derived over a number of periods. • Consumers can decide on the timing of their purchase. • car, washing machine, computer, software, . . . • By analogy, items that can be ordered in advance • holiday package, plane ticket, concert ticket, . . . • Main question • Selling at various points in time opens up the possibility of intertemporal price discrimination • Is it a profitable option for the firm? © Cambridge University Press 2010 3

Chapter 10 - Durable good monopoly without commitment • Basic outline • Monopoly selling a durable good • No possibility to commit over future prices • The firm sets the period t price in that period, not earlier. • It has to take into account the consumers’ expectations over future prices. • Is intertemporal price discrimination profitable? • Rough answer: • Yes if small number of consumers • No if large number of consumers • To show this, we contrast 2 models • Small number of consumers 2 consumers • Large number of consumers continuum © Cambridge University Press 2010 4

Chapter 10 - Durable good monopoly without commitment • Basic outline • Monopoly selling a durable good • No possibility to commit over future prices • The firm sets the period t price in that period, not earlier. • It has to take into account the consumers’ expectations over future prices. • Is intertemporal price discrimination profitable? • Rough answer: • Yes if small number of consumers • No if large number of consumers • To show this, we contrast 2 models • Small number of consumers 2 consumers • Large number of consumers continuum © Cambridge University Press 2010 4

Chapter 10 - Durable good monopoly without commitment • Common framework for the 2 models (cont’d) • Durable product can be sold over 2 periods • Consumers derive utility from a unit of this product only in these 2 periods. • Monopolist sets price of product in period 1 (p 1) and in period 2 (p 2). • Consumers who purchase the product in period 1 (2) benefit from its services for 2 (1) periods. • Firm and consumers have the same discount factor, . © Cambridge University Press 2010 5

Chapter 10 - Durable good monopoly without commitment • Common framework for the 2 models (cont’d) • Durable product can be sold over 2 periods • Consumers derive utility from a unit of this product only in these 2 periods. • Monopolist sets price of product in period 1 (p 1) and in period 2 (p 2). • Consumers who purchase the product in period 1 (2) benefit from its services for 2 (1) periods. • Firm and consumers have the same discount factor, . © Cambridge University Press 2010 5

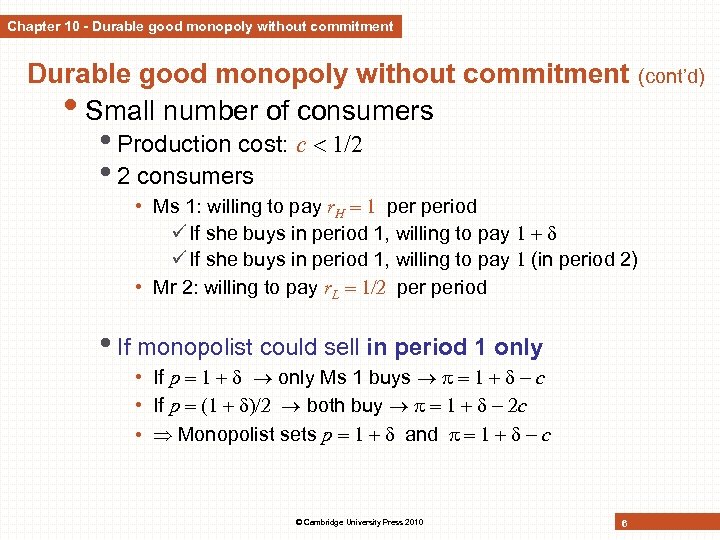

Chapter 10 - Durable good monopoly without commitment • Small number of consumers • Production cost: c • 2 consumers • Ms 1: willing to pay r. H period ü If she buys in period 1, willing to pay (in period 2) • Mr 2: willing to pay r. L period • If monopolist could sell in period 1 only • If p only Ms 1 buys c • If p both buy c • Monopolist sets p and c © Cambridge University Press 2010 6 (cont’d)

Chapter 10 - Durable good monopoly without commitment • Small number of consumers • Production cost: c • 2 consumers • Ms 1: willing to pay r. H period ü If she buys in period 1, willing to pay (in period 2) • Mr 2: willing to pay r. L period • If monopolist could sell in period 1 only • If p only Ms 1 buys c • If p both buy c • Monopolist sets p and c © Cambridge University Press 2010 6 (cont’d)

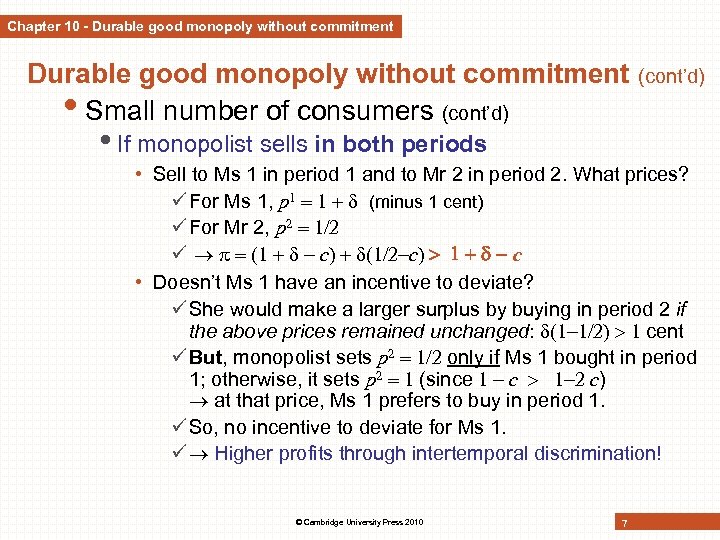

Chapter 10 - Durable good monopoly without commitment • Small number of consumers (cont’d) • If monopolist sells in both periods • Sell to Ms 1 in period 1 and to Mr 2 in period 2. What prices? ü For Ms 1, p 1 (minus 1 cent) ü For Mr 2, p 2 ü c c • Doesn’t Ms 1 have an incentive to deviate? ü She would make a larger surplus by buying in period 2 if the above prices remained unchanged: cent ü But, monopolist sets p 2 only if Ms 1 bought in period 1; otherwise, it sets p 2 (since c c) at that price, Ms 1 prefers to buy in period 1. ü So, no incentive to deviate for Ms 1. ü Higher profits through intertemporal discrimination! © Cambridge University Press 2010 7

Chapter 10 - Durable good monopoly without commitment • Small number of consumers (cont’d) • If monopolist sells in both periods • Sell to Ms 1 in period 1 and to Mr 2 in period 2. What prices? ü For Ms 1, p 1 (minus 1 cent) ü For Mr 2, p 2 ü c c • Doesn’t Ms 1 have an incentive to deviate? ü She would make a larger surplus by buying in period 2 if the above prices remained unchanged: cent ü But, monopolist sets p 2 only if Ms 1 bought in period 1; otherwise, it sets p 2 (since c c) at that price, Ms 1 prefers to buy in period 1. ü So, no incentive to deviate for Ms 1. ü Higher profits through intertemporal discrimination! © Cambridge University Press 2010 7

Chapter 10 - Durable good monopoly without commitment • Small number of consumers (cont’d) • The argument can be extended • to essentially any distribution of willingness to pay ü r. L r. H (see details in book) • to any finite number of consumers and periods • Crucial assumption: monopolist is able to spot individual consumer deviations • Realistic if small number of consumers • Lesson: In a market with 2 consumers, the firm may prefer intertemporal pricing to selling to both consumers in the first period because the firm can fully discriminate between the 2 consumers. © Cambridge University Press 2010 8

Chapter 10 - Durable good monopoly without commitment • Small number of consumers (cont’d) • The argument can be extended • to essentially any distribution of willingness to pay ü r. L r. H (see details in book) • to any finite number of consumers and periods • Crucial assumption: monopolist is able to spot individual consumer deviations • Realistic if small number of consumers • Lesson: In a market with 2 consumers, the firm may prefer intertemporal pricing to selling to both consumers in the first period because the firm can fully discriminate between the 2 consumers. © Cambridge University Press 2010 8

Chapter 10 - Durable good monopoly without commitment • Large number of consumers - Model A (cont’d) • Exact same setting as before with 1 difference: • Continuum of buyers of each type • Each group assumed to be of size 1 • If monopolist could sell in period 1 only • Same as before: it sets p and c • If monopolist sells in both periods • Impossible to condition p 2 on individual deviation of some consumer of type 1 as such deviation cannot be observed. • all Ms 1 expect that if they all buy in period 1, then p 2 • But if p 1 , then all Ms 1 prefer to buy in period 2. • largest possible p 1: p 1 © Cambridge University Press 2010 9

Chapter 10 - Durable good monopoly without commitment • Large number of consumers - Model A (cont’d) • Exact same setting as before with 1 difference: • Continuum of buyers of each type • Each group assumed to be of size 1 • If monopolist could sell in period 1 only • Same as before: it sets p and c • If monopolist sells in both periods • Impossible to condition p 2 on individual deviation of some consumer of type 1 as such deviation cannot be observed. • all Ms 1 expect that if they all buy in period 1, then p 2 • But if p 1 , then all Ms 1 prefer to buy in period 2. • largest possible p 1: p 1 © Cambridge University Press 2010 9

Chapter 10 - Durable good monopoly without commitment (cont’d) • Large number of consumers - Model A (cont’d) • If monopolist sells in both periods • Present discounted value of profit • Lesson: With a continuum of consumers, a durable good monopolist cannot increase profits through intertemporal price discrimination compared to a situation in which it is only active in the first period. © Cambridge University Press 2010 10

Chapter 10 - Durable good monopoly without commitment (cont’d) • Large number of consumers - Model A (cont’d) • If monopolist sells in both periods • Present discounted value of profit • Lesson: With a continuum of consumers, a durable good monopolist cannot increase profits through intertemporal price discrimination compared to a situation in which it is only active in the first period. © Cambridge University Press 2010 10

Chapter 10 - Durable good monopoly without commitment • Large number of consumers - Model B (cont’d) • Same model but with a continuum of different types • Consumer derives in each period a value r from 1 unit. • r is distributed uniformly on [0, 1]; firm’s marginal cost = 0 • If monopolist could sell in period 1 only • Consumer of type r is willing to pay r • Optimal price: p • If monopolist sells in both periods • Candidate equilibrium: p 1 in period 1, consumer buy if r residual demand in period 2: Q 2(p 2) p 2 optimal price: p 2 but at these prices, consumers with r just above prefer to postpone purchase Not an equilibrium © Cambridge University Press 2010 11

Chapter 10 - Durable good monopoly without commitment • Large number of consumers - Model B (cont’d) • Same model but with a continuum of different types • Consumer derives in each period a value r from 1 unit. • r is distributed uniformly on [0, 1]; firm’s marginal cost = 0 • If monopolist could sell in period 1 only • Consumer of type r is willing to pay r • Optimal price: p • If monopolist sells in both periods • Candidate equilibrium: p 1 in period 1, consumer buy if r residual demand in period 2: Q 2(p 2) p 2 optimal price: p 2 but at these prices, consumers with r just above prefer to postpone purchase Not an equilibrium © Cambridge University Press 2010 11

Chapter 10 - Durable good monopoly without commitment (cont’d) • Large number of consumers - Model B (cont’d) • If monopolist sells in both periods: equilibrium • Indifferent consumer between buying in period 1 or 2 • Consumers with lower value of r buy in period 2 • Optimal price in period 2 © Cambridge University Press 2010 12

Chapter 10 - Durable good monopoly without commitment (cont’d) • Large number of consumers - Model B (cont’d) • If monopolist sells in both periods: equilibrium • Indifferent consumer between buying in period 1 or 2 • Consumers with lower value of r buy in period 2 • Optimal price in period 2 © Cambridge University Press 2010 12

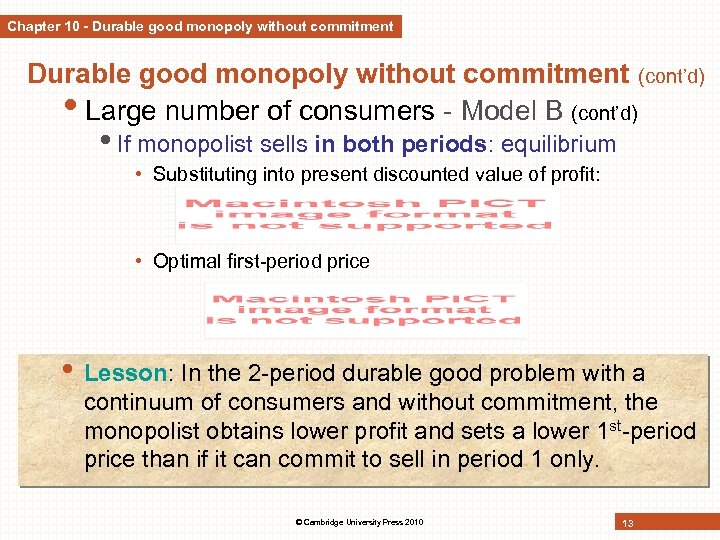

Chapter 10 - Durable good monopoly without commitment (cont’d) • Large number of consumers - Model B (cont’d) • If monopolist sells in both periods: equilibrium • Substituting into present discounted value of profit: • Optimal first-period price • Lesson: In the 2 -period durable good problem with a continuum of consumers and without commitment, the monopolist obtains lower profit and sets a lower 1 st-period price than if it can commit to sell in period 1 only. © Cambridge University Press 2010 13

Chapter 10 - Durable good monopoly without commitment (cont’d) • Large number of consumers - Model B (cont’d) • If monopolist sells in both periods: equilibrium • Substituting into present discounted value of profit: • Optimal first-period price • Lesson: In the 2 -period durable good problem with a continuum of consumers and without commitment, the monopolist obtains lower profit and sets a lower 1 st-period price than if it can commit to sell in period 1 only. © Cambridge University Press 2010 13

Chapter 10 - Durable good monopoly without commitment (cont’d) • Large number of consumers - Model B (cont’d) • Why is intertemporal price discrimination not profitable? • Monopolist faces competition from his own product in period 2 downward pressure on 1 st-period price lower profit • Argument can be extended to more than 2 periods. • When periods become sufficiently small Coase Conjecture: firm loses all price-setting power monopoly setting leads to outcome that converges to the perfectly competitive outcome • Small or large number of consumers? • Consumer goods continuous approximation seems more convincing • If buyers are retailers or intermediaries, model with small number of consumers could be relevant. © Cambridge University Press 2010 14

Chapter 10 - Durable good monopoly without commitment (cont’d) • Large number of consumers - Model B (cont’d) • Why is intertemporal price discrimination not profitable? • Monopolist faces competition from his own product in period 2 downward pressure on 1 st-period price lower profit • Argument can be extended to more than 2 periods. • When periods become sufficiently small Coase Conjecture: firm loses all price-setting power monopoly setting leads to outcome that converges to the perfectly competitive outcome • Small or large number of consumers? • Consumer goods continuous approximation seems more convincing • If buyers are retailers or intermediaries, model with small number of consumers could be relevant. © Cambridge University Press 2010 14

Chapter 10 - Durable good monopoly without commitment Case. The Microsoft case • 1998 • US Do. J accused Microsoft (MS) of antitrust violation • Motive: inclusion of web browser in operating system • Testimony of R. L. Schmalensee on behalf of MS • “Microsoft does not have monopoly power. . . ” • Argument: when assessing market power, one should look at dynamic competition • “Software products are durable goods, so the producer can make additional sales only as a result of selling to people who have not previously bought the product or by selling upgrades to previous customers. Selling upgrades to their installed base of users has historically been an important source of revenue for software firms. In the case of Microsoft, more than 35 percent of Office revenues comes from upgrades rather than new sales. ” © Cambridge University Press 2010 15

Chapter 10 - Durable good monopoly without commitment Case. The Microsoft case • 1998 • US Do. J accused Microsoft (MS) of antitrust violation • Motive: inclusion of web browser in operating system • Testimony of R. L. Schmalensee on behalf of MS • “Microsoft does not have monopoly power. . . ” • Argument: when assessing market power, one should look at dynamic competition • “Software products are durable goods, so the producer can make additional sales only as a result of selling to people who have not previously bought the product or by selling upgrades to previous customers. Selling upgrades to their installed base of users has historically been an important source of revenue for software firms. In the case of Microsoft, more than 35 percent of Office revenues comes from upgrades rather than new sales. ” © Cambridge University Press 2010 15

Chapter 10 - Durable good monopoly with commitment • How can firms commit to future prices? • Renting instead of selling. • Contracts return policies, money-back guarantees, repurchase agreements • Reputation • Technology planned obsolescence (software, textbooks), capacity restrictions • Is intertemporal price discrimination (through introductory offers or clearance sales) profitable? • YES if capacities are fixed (and limited • NO if capacities are flexible. © Cambridge University Press 2010 16

Chapter 10 - Durable good monopoly with commitment • How can firms commit to future prices? • Renting instead of selling. • Contracts return policies, money-back guarantees, repurchase agreements • Reputation • Technology planned obsolescence (software, textbooks), capacity restrictions • Is intertemporal price discrimination (through introductory offers or clearance sales) profitable? • YES if capacities are fixed (and limited • NO if capacities are flexible. © Cambridge University Press 2010 16

Chapter 10 - Durable good monopoly with commitment (cont’d) • Fixed capacity • Monopolist faces a binding capacity constraint. • Example: sale of tickets for a particular event • May use intertemporal price discrimination. • Introductory offer: a limited quantity is provided at a low price in advance. • Clearance sale: the firm initially sells at a high price and commits to sell the remaining units at a low price. • Lesson: Under fixed and limited capacity, and under demand certainty, both clearance sales and introductory offers allow the monopolist to ‘concavify’ its single-price revenue function and lead to the same revenue, which may be greater than with uniform pricing. © Cambridge University Press 2010 17

Chapter 10 - Durable good monopoly with commitment (cont’d) • Fixed capacity • Monopolist faces a binding capacity constraint. • Example: sale of tickets for a particular event • May use intertemporal price discrimination. • Introductory offer: a limited quantity is provided at a low price in advance. • Clearance sale: the firm initially sells at a high price and commits to sell the remaining units at a low price. • Lesson: Under fixed and limited capacity, and under demand certainty, both clearance sales and introductory offers allow the monopolist to ‘concavify’ its single-price revenue function and lead to the same revenue, which may be greater than with uniform pricing. © Cambridge University Press 2010 17

Chapter 10 - Durable good monopoly with commitment (cont’d) • Flexible capacity • Here: monopoly can adjust capacity at an initial stage without cost. • Lesson: If capacity can be adjusted without cost, there is no rationale to intertemporally price discriminate in markets in which demand is certain and in which consumers do not learn over time. • More generally: intertemporal price discrimination can only be optimal if • capacity costs are not linear • the single-price revenue function is not single-peaked. (See details in book. ) © Cambridge University Press 2010 18

Chapter 10 - Durable good monopoly with commitment (cont’d) • Flexible capacity • Here: monopoly can adjust capacity at an initial stage without cost. • Lesson: If capacity can be adjusted without cost, there is no rationale to intertemporally price discriminate in markets in which demand is certain and in which consumers do not learn over time. • More generally: intertemporal price discrimination can only be optimal if • capacity costs are not linear • the single-price revenue function is not single-peaked. (See details in book. ) © Cambridge University Press 2010 18

Chapter 10 - Durable good monopoly with commitment (cont’d) • Demand uncertainty • Attractiveness of intertemporal price discrimination • Aggregate demand uncertainty • Firm’s demand is subject to shocks. • Introductory offers and clearance sales can dominate uniform pricing even if there are no capacity costs ex ante. ü For clearance sales: must be able to commit to total capacity and a second-period price. ü For introductory offers: must be able to limit the supply of the product in the first period. • Lesson: Even if capacity can be adjusted ex ante without cost, intertemporal price discrimination can be profit maximizing under aggregate demand uncertainty. © Cambridge University Press 2010 19

Chapter 10 - Durable good monopoly with commitment (cont’d) • Demand uncertainty • Attractiveness of intertemporal price discrimination • Aggregate demand uncertainty • Firm’s demand is subject to shocks. • Introductory offers and clearance sales can dominate uniform pricing even if there are no capacity costs ex ante. ü For clearance sales: must be able to commit to total capacity and a second-period price. ü For introductory offers: must be able to limit the supply of the product in the first period. • Lesson: Even if capacity can be adjusted ex ante without cost, intertemporal price discrimination can be profit maximizing under aggregate demand uncertainty. © Cambridge University Press 2010 19

Chapter 10 - Durable good monopoly with commitment Case. Zara and the clothing industry • Demand uncertainty is high. • Demand for clothing varies with weather conditions and changes in tastes. • Capacity constraints • Retailers have to order stocks before new season. • Restocking during season used to be difficult. • Clearance or season sales are used to clear stocks before new collection arrives. • Recent advances • Flexible manufacturing & use of IT lead time. • Vertically integrated clothing companies, like Zara, are able to replenish stocks rapidly. • Zara uses clearance sales less frequently (as previous theory predicts). © Cambridge University Press 2010 20

Chapter 10 - Durable good monopoly with commitment Case. Zara and the clothing industry • Demand uncertainty is high. • Demand for clothing varies with weather conditions and changes in tastes. • Capacity constraints • Retailers have to order stocks before new season. • Restocking during season used to be difficult. • Clearance or season sales are used to clear stocks before new collection arrives. • Recent advances • Flexible manufacturing & use of IT lead time. • Vertically integrated clothing companies, like Zara, are able to replenish stocks rapidly. • Zara uses clearance sales less frequently (as previous theory predicts). © Cambridge University Press 2010 20

Chapter 10 - Durable good monopoly with commitment (cont’d) • Demand uncertainty (cont’d) • Uncertainty for individual consumers • Consumers obtain better knowledge about their valuation for the product over time. ü Applies to many ticket purchases • Advantage of intertemporal price discrimination ü Distinguish between different types of consumers who have different valuations of the good and whose valuation for the product is revealed over time. • Lesson: A firm may optimally use intertemporal pricing as a price discrimination device in an environment in which it can perfectly predict its demand but not all consumers can perfectly predict their valuation at the beginning. © Cambridge University Press 2010 21

Chapter 10 - Durable good monopoly with commitment (cont’d) • Demand uncertainty (cont’d) • Uncertainty for individual consumers • Consumers obtain better knowledge about their valuation for the product over time. ü Applies to many ticket purchases • Advantage of intertemporal price discrimination ü Distinguish between different types of consumers who have different valuations of the good and whose valuation for the product is revealed over time. • Lesson: A firm may optimally use intertemporal pricing as a price discrimination device in an environment in which it can perfectly predict its demand but not all consumers can perfectly predict their valuation at the beginning. © Cambridge University Press 2010 21

Chapter 10 - Behaviour-based price discrimination • Prices are based on purchasing history. • E-commerce: ‘cookies’ allow sellers to monitor consumer transactions. • Model • Continuum of consumer types • Willingness to pay: r U • Non-durable good • Consumption occurs in the period of purchase • 2 periods; consumers may want to buy in any period. • Same discount factor firm and consumers: • Firm cannot commit to future prices but can make nd 2 -period price conditional on whether consumer has purchased in period 1; firm sets Offered to consumers who didn’t buy in period 1 © Cambridge University Press 2010 22

Chapter 10 - Behaviour-based price discrimination • Prices are based on purchasing history. • E-commerce: ‘cookies’ allow sellers to monitor consumer transactions. • Model • Continuum of consumer types • Willingness to pay: r U • Non-durable good • Consumption occurs in the period of purchase • 2 periods; consumers may want to buy in any period. • Same discount factor firm and consumers: • Firm cannot commit to future prices but can make nd 2 -period price conditional on whether consumer has purchased in period 1; firm sets Offered to consumers who didn’t buy in period 1 © Cambridge University Press 2010 22

Chapter 10 - Behaviour-based price discrimination (cont’d) • Equilibrium • 2 nd period: if all consumers with have bought in period 1, then optimal price for consumers who bought in period 1 is Other consumers are offered • 1 st period: indifferent consumer satisfies • Firm’s profits © Cambridge University Press 2010 23

Chapter 10 - Behaviour-based price discrimination (cont’d) • Equilibrium • 2 nd period: if all consumers with have bought in period 1, then optimal price for consumers who bought in period 1 is Other consumers are offered • 1 st period: indifferent consumer satisfies • Firm’s profits © Cambridge University Press 2010 23

Chapter 10 - Behaviour-based price discrimination (cont’d) • Lesson: A firm that sells a good over 2 periods and cannot commit to future prices conditions its second-period price on purchase history. • If firm was able to commit to future prices • Not profitable to condition price on purchase history • Optimum: p 1 p 2 higher profit: • Standard commitment problem. Why? • Present model is equivalent to a model of renting a durable good. • If a durable good monopolist operates in a market that opens for 2 periods and is able to condition its rental price on rental history, selling or renting out a durable good is revenue equivalent. © Cambridge University Press 2010 24

Chapter 10 - Behaviour-based price discrimination (cont’d) • Lesson: A firm that sells a good over 2 periods and cannot commit to future prices conditions its second-period price on purchase history. • If firm was able to commit to future prices • Not profitable to condition price on purchase history • Optimum: p 1 p 2 higher profit: • Standard commitment problem. Why? • Present model is equivalent to a model of renting a durable good. • If a durable good monopolist operates in a market that opens for 2 periods and is able to condition its rental price on rental history, selling or renting out a durable good is revenue equivalent. © Cambridge University Press 2010 24

Chapter 10 - Review questions • If a durable good monopolist cannot commit to future prices, does the number of consumers matter? Explain. • Does a durable good monopolist have an incentive to set its prices flexibly in each period? Discuss. • Why would a monopolist deviate from uniform pricing and set non-constant prices? And what selling policies may it choose? • What happens if a firm can set individualized prices depending on previous purchases? © Cambridge University Press 2010 25

Chapter 10 - Review questions • If a durable good monopolist cannot commit to future prices, does the number of consumers matter? Explain. • Does a durable good monopolist have an incentive to set its prices flexibly in each period? Discuss. • Why would a monopolist deviate from uniform pricing and set non-constant prices? And what selling policies may it choose? • What happens if a firm can set individualized prices depending on previous purchases? © Cambridge University Press 2010 25