3cfefb00db443aef5aaf042c239822d5.ppt

- Количество слайдов: 85

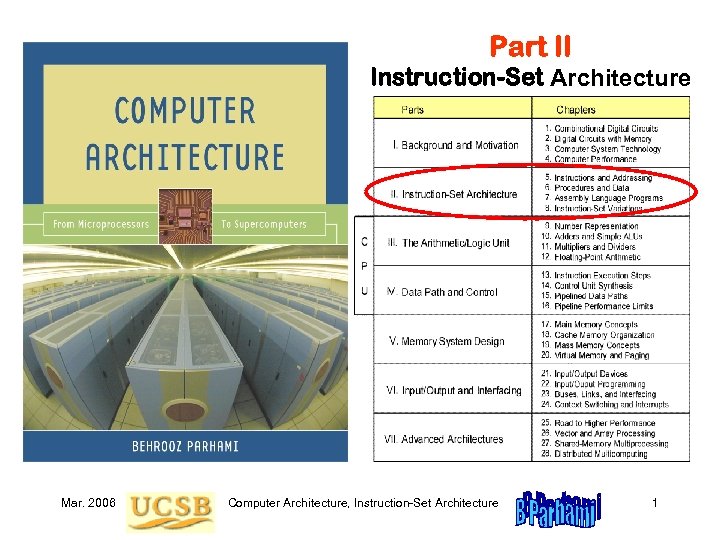

Part II Instruction-Set Architecture Mar. 2006 Computer Architecture, Instruction-Set Architecture 1

Part II Instruction-Set Architecture Mar. 2006 Computer Architecture, Instruction-Set Architecture 1

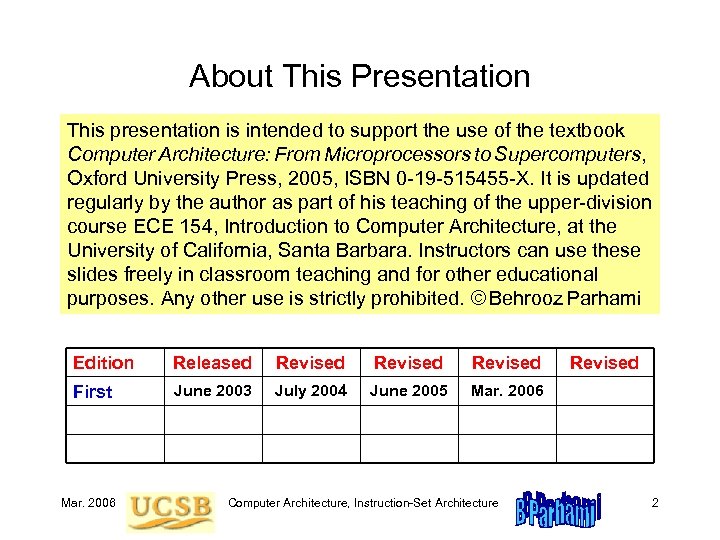

About This Presentation This presentation is intended to support the use of the textbook Computer Architecture: From Microprocessors to Supercomputers, Oxford University Press, 2005, ISBN 0 -19 -515455 -X. It is updated regularly by the author as part of his teaching of the upper-division course ECE 154, Introduction to Computer Architecture, at the University of California, Santa Barbara. Instructors can use these slides freely in classroom teaching and for other educational purposes. Any other use is strictly prohibited. © Behrooz Parhami Edition Released Revised First June 2003 July 2004 June 2005 Mar. 2006 Computer Architecture, Instruction-Set Architecture Revised 2

About This Presentation This presentation is intended to support the use of the textbook Computer Architecture: From Microprocessors to Supercomputers, Oxford University Press, 2005, ISBN 0 -19 -515455 -X. It is updated regularly by the author as part of his teaching of the upper-division course ECE 154, Introduction to Computer Architecture, at the University of California, Santa Barbara. Instructors can use these slides freely in classroom teaching and for other educational purposes. Any other use is strictly prohibited. © Behrooz Parhami Edition Released Revised First June 2003 July 2004 June 2005 Mar. 2006 Computer Architecture, Instruction-Set Architecture Revised 2

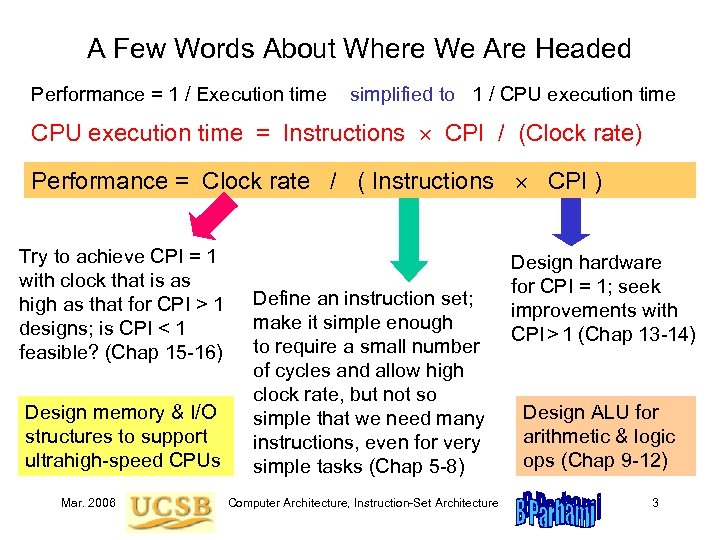

A Few Words About Where We Are Headed Performance = 1 / Execution time simplified to 1 / CPU execution time = Instructions CPI / (Clock rate) Performance = Clock rate / ( Instructions CPI ) Try to achieve CPI = 1 with clock that is as high as that for CPI > 1 designs; is CPI < 1 feasible? (Chap 15 -16) Design memory & I/O structures to support ultrahigh-speed CPUs Mar. 2006 Define an instruction set; make it simple enough to require a small number of cycles and allow high clock rate, but not so simple that we need many instructions, even for very simple tasks (Chap 5 -8) Computer Architecture, Instruction-Set Architecture Design hardware for CPI = 1; seek improvements with CPI > 1 (Chap 13 -14) Design ALU for arithmetic & logic ops (Chap 9 -12) 3

A Few Words About Where We Are Headed Performance = 1 / Execution time simplified to 1 / CPU execution time = Instructions CPI / (Clock rate) Performance = Clock rate / ( Instructions CPI ) Try to achieve CPI = 1 with clock that is as high as that for CPI > 1 designs; is CPI < 1 feasible? (Chap 15 -16) Design memory & I/O structures to support ultrahigh-speed CPUs Mar. 2006 Define an instruction set; make it simple enough to require a small number of cycles and allow high clock rate, but not so simple that we need many instructions, even for very simple tasks (Chap 5 -8) Computer Architecture, Instruction-Set Architecture Design hardware for CPI = 1; seek improvements with CPI > 1 (Chap 13 -14) Design ALU for arithmetic & logic ops (Chap 9 -12) 3

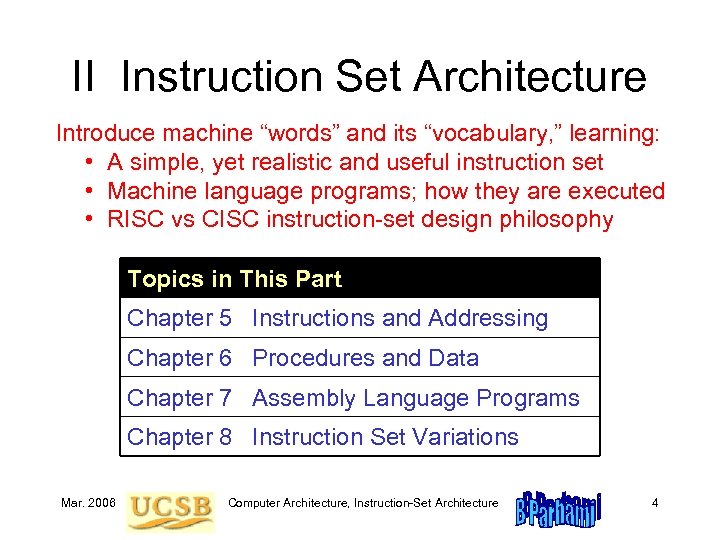

II Instruction Set Architecture Introduce machine “words” and its “vocabulary, ” learning: • A simple, yet realistic and useful instruction set • Machine language programs; how they are executed • RISC vs CISC instruction-set design philosophy Topics in This Part Chapter 5 Instructions and Addressing Chapter 6 Procedures and Data Chapter 7 Assembly Language Programs Chapter 8 Instruction Set Variations Mar. 2006 Computer Architecture, Instruction-Set Architecture 4

II Instruction Set Architecture Introduce machine “words” and its “vocabulary, ” learning: • A simple, yet realistic and useful instruction set • Machine language programs; how they are executed • RISC vs CISC instruction-set design philosophy Topics in This Part Chapter 5 Instructions and Addressing Chapter 6 Procedures and Data Chapter 7 Assembly Language Programs Chapter 8 Instruction Set Variations Mar. 2006 Computer Architecture, Instruction-Set Architecture 4

5 Instructions and Addressing First of two chapters on the instruction set of Mini. MIPS: • Required for hardware concepts in later chapters • Not aiming for proficiency in assembler programming Topics in This Chapter 5. 1 Abstract View of Hardware 5. 2 Instruction Formats 5. 3 Simple Arithmetic / Logic Instructions 5. 4 Load and Store Instructions 5. 5 Jump and Branch Instructions 5. 6 Addressing Modes Mar. 2006 Computer Architecture, Instruction-Set Architecture 5

5 Instructions and Addressing First of two chapters on the instruction set of Mini. MIPS: • Required for hardware concepts in later chapters • Not aiming for proficiency in assembler programming Topics in This Chapter 5. 1 Abstract View of Hardware 5. 2 Instruction Formats 5. 3 Simple Arithmetic / Logic Instructions 5. 4 Load and Store Instructions 5. 5 Jump and Branch Instructions 5. 6 Addressing Modes Mar. 2006 Computer Architecture, Instruction-Set Architecture 5

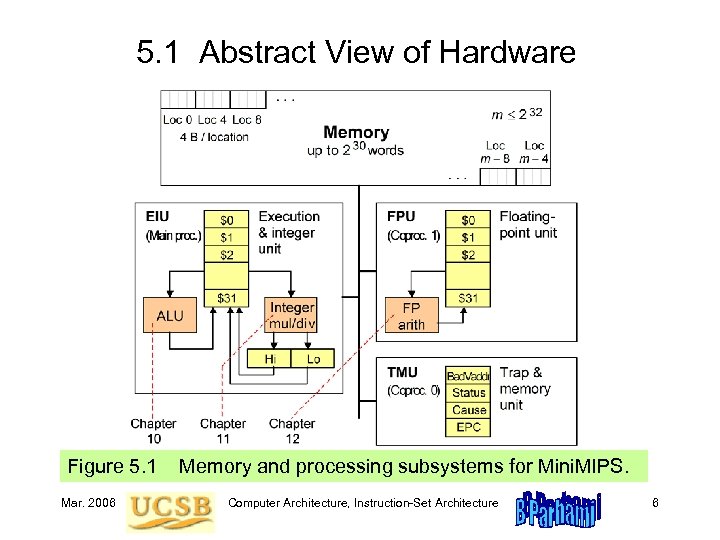

5. 1 Abstract View of Hardware Figure 5. 1 Memory and processing subsystems for Mini. MIPS. Mar. 2006 Computer Architecture, Instruction-Set Architecture 6

5. 1 Abstract View of Hardware Figure 5. 1 Memory and processing subsystems for Mini. MIPS. Mar. 2006 Computer Architecture, Instruction-Set Architecture 6

Data Types Byte = 8 bits Halfword = 2 bytes Word = 4 bytes Doubleword = 8 bytes Mini. MIPS registers hold 32 -bit (4 -byte) words. Other common data sizes include byte, halfword, and doubleword. Mar. 2006 Computer Architecture, Instruction-Set Architecture 7

Data Types Byte = 8 bits Halfword = 2 bytes Word = 4 bytes Doubleword = 8 bytes Mini. MIPS registers hold 32 -bit (4 -byte) words. Other common data sizes include byte, halfword, and doubleword. Mar. 2006 Computer Architecture, Instruction-Set Architecture 7

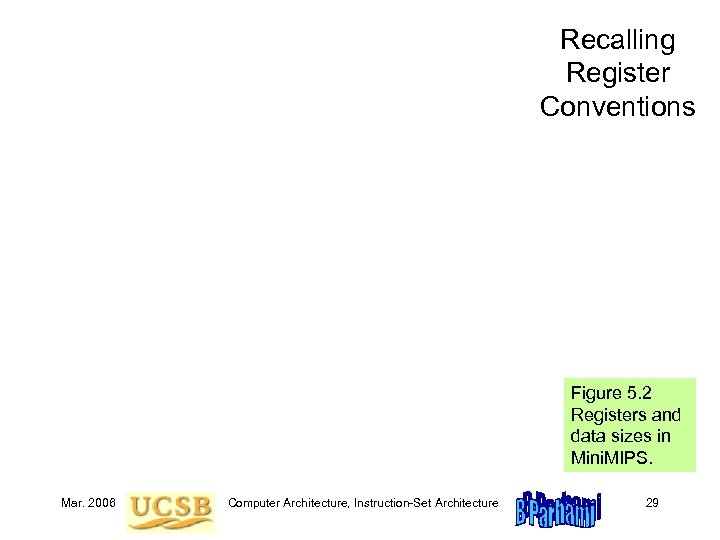

Register Conventions Figure 5. 2 Registers and data sizes in Mini. MIPS. Mar. 2006 Computer Architecture, Instruction-Set Architecture 8

Register Conventions Figure 5. 2 Registers and data sizes in Mini. MIPS. Mar. 2006 Computer Architecture, Instruction-Set Architecture 8

Registers Used in This Chapter 10 temporary registers 8 operand registers Figure 5. 2 (partial) Mar. 2006 Computer Architecture, Instruction-Set Architecture 9

Registers Used in This Chapter 10 temporary registers 8 operand registers Figure 5. 2 (partial) Mar. 2006 Computer Architecture, Instruction-Set Architecture 9

5. 2 Instruction Formats Figure 5. 3 A typical instruction for Mini. MIPS and steps in its execution. Mar. 2006 Computer Architecture, Instruction-Set Architecture 10

5. 2 Instruction Formats Figure 5. 3 A typical instruction for Mini. MIPS and steps in its execution. Mar. 2006 Computer Architecture, Instruction-Set Architecture 10

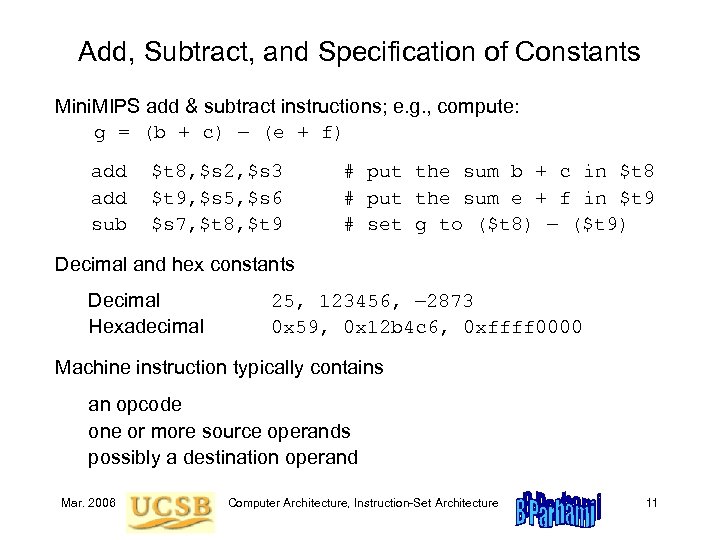

Add, Subtract, and Specification of Constants Mini. MIPS add & subtract instructions; e. g. , compute: g = (b + c) (e + f) add sub $t 8, $s 2, $s 3 $t 9, $s 5, $s 6 $s 7, $t 8, $t 9 # put the sum b + c in $t 8 # put the sum e + f in $t 9 # set g to ($t 8) ($t 9) Decimal and hex constants Decimal Hexadecimal 25, 123456, 2873 0 x 59, 0 x 12 b 4 c 6, 0 xffff 0000 Machine instruction typically contains an opcode one or more source operands possibly a destination operand Mar. 2006 Computer Architecture, Instruction-Set Architecture 11

Add, Subtract, and Specification of Constants Mini. MIPS add & subtract instructions; e. g. , compute: g = (b + c) (e + f) add sub $t 8, $s 2, $s 3 $t 9, $s 5, $s 6 $s 7, $t 8, $t 9 # put the sum b + c in $t 8 # put the sum e + f in $t 9 # set g to ($t 8) ($t 9) Decimal and hex constants Decimal Hexadecimal 25, 123456, 2873 0 x 59, 0 x 12 b 4 c 6, 0 xffff 0000 Machine instruction typically contains an opcode one or more source operands possibly a destination operand Mar. 2006 Computer Architecture, Instruction-Set Architecture 11

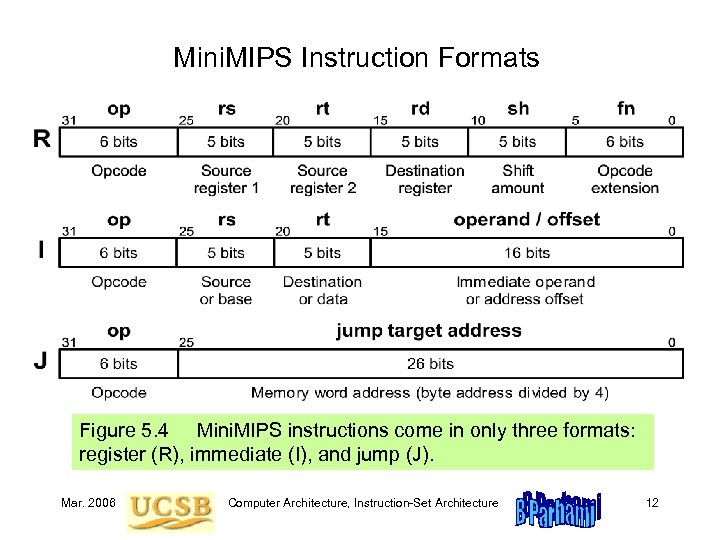

Mini. MIPS Instruction Formats Figure 5. 4 Mini. MIPS instructions come in only three formats: register (R), immediate (I), and jump (J). Mar. 2006 Computer Architecture, Instruction-Set Architecture 12

Mini. MIPS Instruction Formats Figure 5. 4 Mini. MIPS instructions come in only three formats: register (R), immediate (I), and jump (J). Mar. 2006 Computer Architecture, Instruction-Set Architecture 12

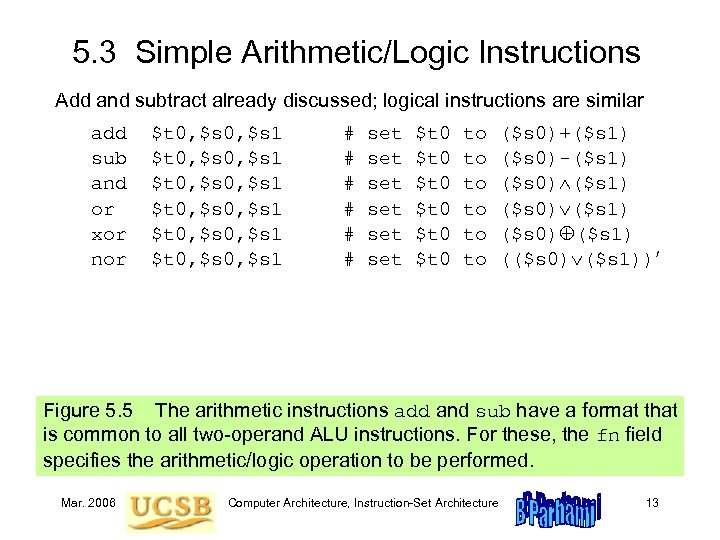

5. 3 Simple Arithmetic/Logic Instructions Add and subtract already discussed; logical instructions are similar add sub and or xor nor $t 0, $s 0, $s 1 $t 0, $s 1 # # # set set set $t 0 $t 0 to to to ($s 0)+($s 1) ($s 0)-($s 1) ($s 0) ($s 1) (($s 0) ($s 1)) Figure 5. 5 The arithmetic instructions add and sub have a format that is common to all two-operand ALU instructions. For these, the fn field specifies the arithmetic/logic operation to be performed. Mar. 2006 Computer Architecture, Instruction-Set Architecture 13

5. 3 Simple Arithmetic/Logic Instructions Add and subtract already discussed; logical instructions are similar add sub and or xor nor $t 0, $s 0, $s 1 $t 0, $s 1 # # # set set set $t 0 $t 0 to to to ($s 0)+($s 1) ($s 0)-($s 1) ($s 0) ($s 1) (($s 0) ($s 1)) Figure 5. 5 The arithmetic instructions add and sub have a format that is common to all two-operand ALU instructions. For these, the fn field specifies the arithmetic/logic operation to be performed. Mar. 2006 Computer Architecture, Instruction-Set Architecture 13

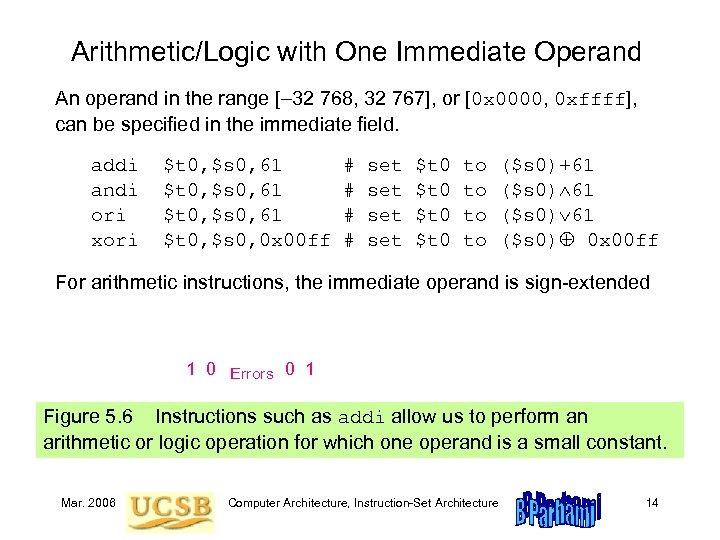

Arithmetic/Logic with One Immediate Operand An operand in the range [ 32 768, 32 767], or [0 x 0000, 0 xffff], can be specified in the immediate field. addi andi ori xori $t 0, $s 0, 61 $t 0, $s 0, 0 x 00 ff # # set set $t 0 to to ($s 0)+61 ($s 0) 0 x 00 ff For arithmetic instructions, the immediate operand is sign-extended 1 0 Errors 0 1 Figure 5. 6 Instructions such as addi allow us to perform an arithmetic or logic operation for which one operand is a small constant. Mar. 2006 Computer Architecture, Instruction-Set Architecture 14

Arithmetic/Logic with One Immediate Operand An operand in the range [ 32 768, 32 767], or [0 x 0000, 0 xffff], can be specified in the immediate field. addi andi ori xori $t 0, $s 0, 61 $t 0, $s 0, 0 x 00 ff # # set set $t 0 to to ($s 0)+61 ($s 0) 0 x 00 ff For arithmetic instructions, the immediate operand is sign-extended 1 0 Errors 0 1 Figure 5. 6 Instructions such as addi allow us to perform an arithmetic or logic operation for which one operand is a small constant. Mar. 2006 Computer Architecture, Instruction-Set Architecture 14

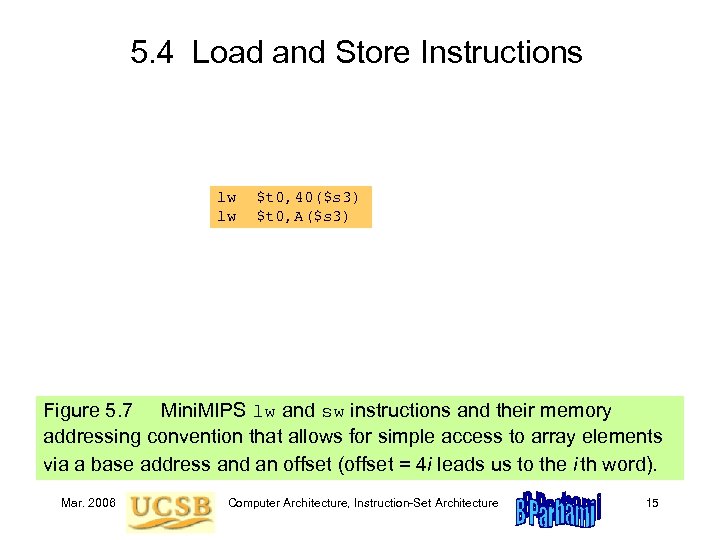

5. 4 Load and Store Instructions lw lw $t 0, 40($s 3) $t 0, A($s 3) Figure 5. 7 Mini. MIPS lw and sw instructions and their memory addressing convention that allows for simple access to array elements via a base address and an offset (offset = 4 i leads us to the i th word). Mar. 2006 Computer Architecture, Instruction-Set Architecture 15

5. 4 Load and Store Instructions lw lw $t 0, 40($s 3) $t 0, A($s 3) Figure 5. 7 Mini. MIPS lw and sw instructions and their memory addressing convention that allows for simple access to array elements via a base address and an offset (offset = 4 i leads us to the i th word). Mar. 2006 Computer Architecture, Instruction-Set Architecture 15

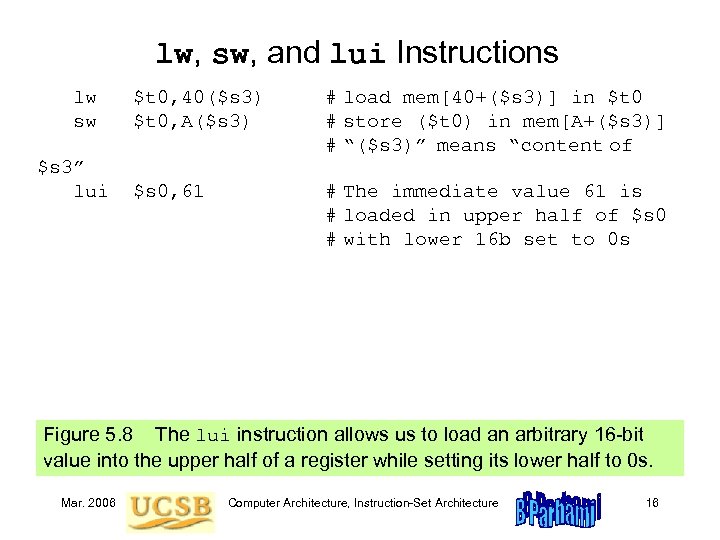

lw, sw, and lui Instructions lw sw $s 3” lui $t 0, 40($s 3) $t 0, A($s 3) # load mem[40+($s 3)] in $t 0 # store ($t 0) in mem[A+($s 3)] # “($s 3)” means “content of $s 0, 61 # The immediate value 61 is # loaded in upper half of $s 0 # with lower 16 b set to 0 s Figure 5. 8 The lui instruction allows us to load an arbitrary 16 -bit value into the upper half of a register while setting its lower half to 0 s. Mar. 2006 Computer Architecture, Instruction-Set Architecture 16

lw, sw, and lui Instructions lw sw $s 3” lui $t 0, 40($s 3) $t 0, A($s 3) # load mem[40+($s 3)] in $t 0 # store ($t 0) in mem[A+($s 3)] # “($s 3)” means “content of $s 0, 61 # The immediate value 61 is # loaded in upper half of $s 0 # with lower 16 b set to 0 s Figure 5. 8 The lui instruction allows us to load an arbitrary 16 -bit value into the upper half of a register while setting its lower half to 0 s. Mar. 2006 Computer Architecture, Instruction-Set Architecture 16

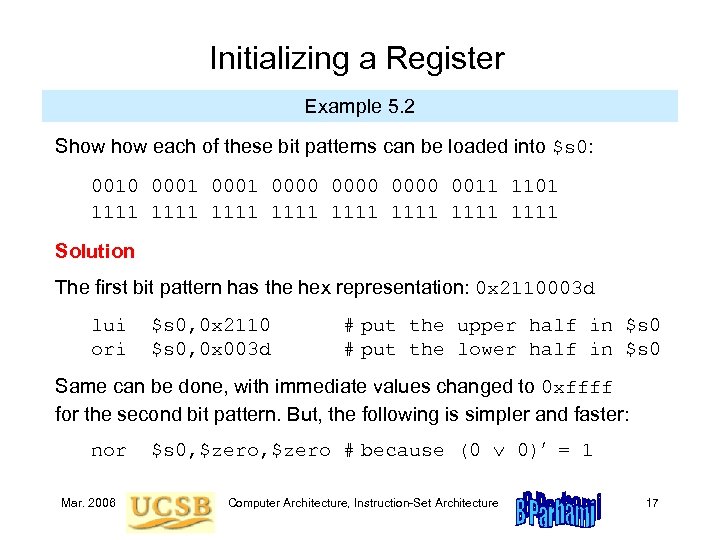

Initializing a Register Example 5. 2 Show each of these bit patterns can be loaded into $s 0: 0010 0001 0000 0011 1101 1111 1111 Solution The first bit pattern has the hex representation: 0 x 2110003 d lui ori $s 0, 0 x 2110 $s 0, 0 x 003 d # put the upper half in $s 0 # put the lower half in $s 0 Same can be done, with immediate values changed to 0 xffff for the second bit pattern. But, the following is simpler and faster: nor Mar. 2006 $s 0, $zero # because (0 0) = 1 Computer Architecture, Instruction-Set Architecture 17

Initializing a Register Example 5. 2 Show each of these bit patterns can be loaded into $s 0: 0010 0001 0000 0011 1101 1111 1111 Solution The first bit pattern has the hex representation: 0 x 2110003 d lui ori $s 0, 0 x 2110 $s 0, 0 x 003 d # put the upper half in $s 0 # put the lower half in $s 0 Same can be done, with immediate values changed to 0 xffff for the second bit pattern. But, the following is simpler and faster: nor Mar. 2006 $s 0, $zero # because (0 0) = 1 Computer Architecture, Instruction-Set Architecture 17

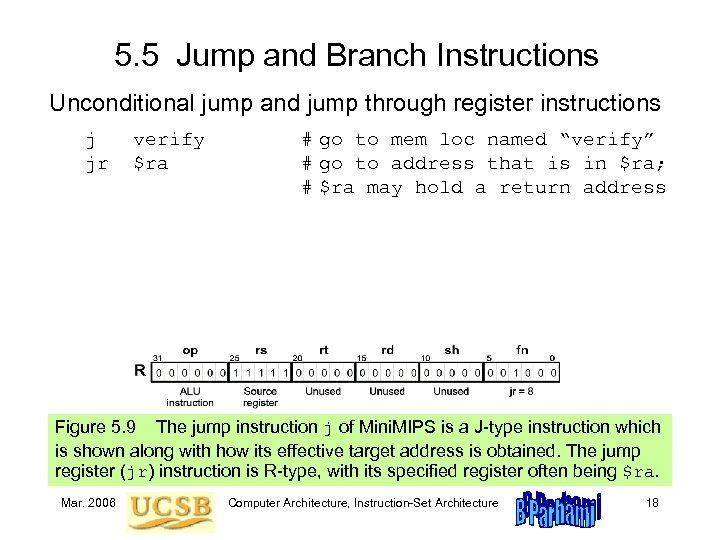

5. 5 Jump and Branch Instructions Unconditional jump and jump through register instructions j jr verify $ra # go to mem loc named “verify” # go to address that is in $ra; # $ra may hold a return address Figure 5. 9 The jump instruction j of Mini. MIPS is a J-type instruction which is shown along with how its effective target address is obtained. The jump register (jr) instruction is R-type, with its specified register often being $ra. Mar. 2006 Computer Architecture, Instruction-Set Architecture 18

5. 5 Jump and Branch Instructions Unconditional jump and jump through register instructions j jr verify $ra # go to mem loc named “verify” # go to address that is in $ra; # $ra may hold a return address Figure 5. 9 The jump instruction j of Mini. MIPS is a J-type instruction which is shown along with how its effective target address is obtained. The jump register (jr) instruction is R-type, with its specified register often being $ra. Mar. 2006 Computer Architecture, Instruction-Set Architecture 18

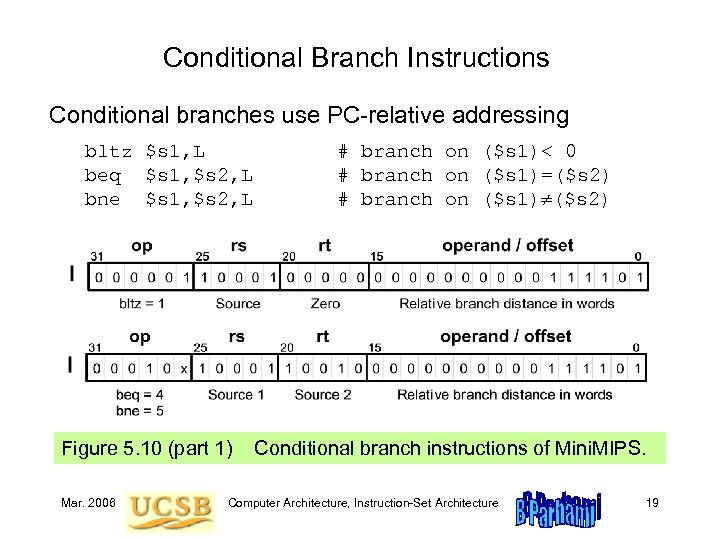

Conditional Branch Instructions Conditional branches use PC-relative addressing bltz $s 1, L beq $s 1, $s 2, L bne $s 1, $s 2, L # branch on ($s 1)< 0 # branch on ($s 1)=($s 2) # branch on ($s 1) ($s 2) Figure 5. 10 (part 1) Conditional branch instructions of Mini. MIPS. Mar. 2006 Computer Architecture, Instruction-Set Architecture 19

Conditional Branch Instructions Conditional branches use PC-relative addressing bltz $s 1, L beq $s 1, $s 2, L bne $s 1, $s 2, L # branch on ($s 1)< 0 # branch on ($s 1)=($s 2) # branch on ($s 1) ($s 2) Figure 5. 10 (part 1) Conditional branch instructions of Mini. MIPS. Mar. 2006 Computer Architecture, Instruction-Set Architecture 19

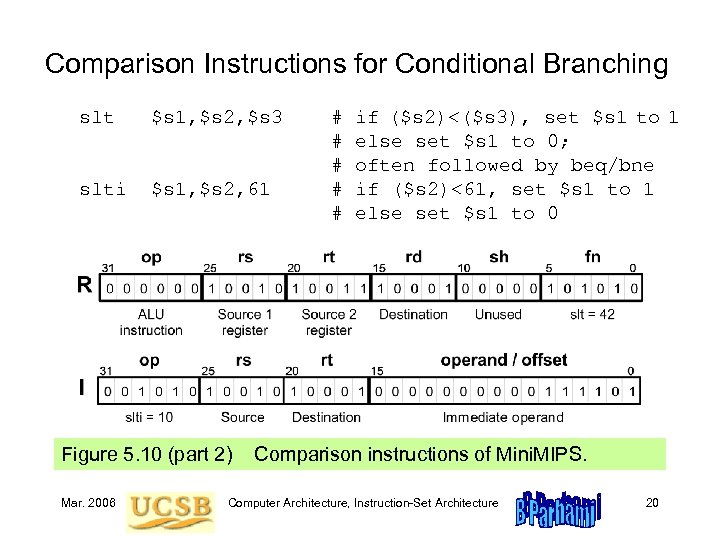

Comparison Instructions for Conditional Branching slt $s 1, $s 2, $s 3 slti $s 1, $s 2, 61 # # # if ($s 2)<($s 3), set $s 1 to 1 else set $s 1 to 0; often followed by beq/bne if ($s 2)<61, set $s 1 to 1 else set $s 1 to 0 Figure 5. 10 (part 2) Comparison instructions of Mini. MIPS. Mar. 2006 Computer Architecture, Instruction-Set Architecture 20

Comparison Instructions for Conditional Branching slt $s 1, $s 2, $s 3 slti $s 1, $s 2, 61 # # # if ($s 2)<($s 3), set $s 1 to 1 else set $s 1 to 0; often followed by beq/bne if ($s 2)<61, set $s 1 to 1 else set $s 1 to 0 Figure 5. 10 (part 2) Comparison instructions of Mini. MIPS. Mar. 2006 Computer Architecture, Instruction-Set Architecture 20

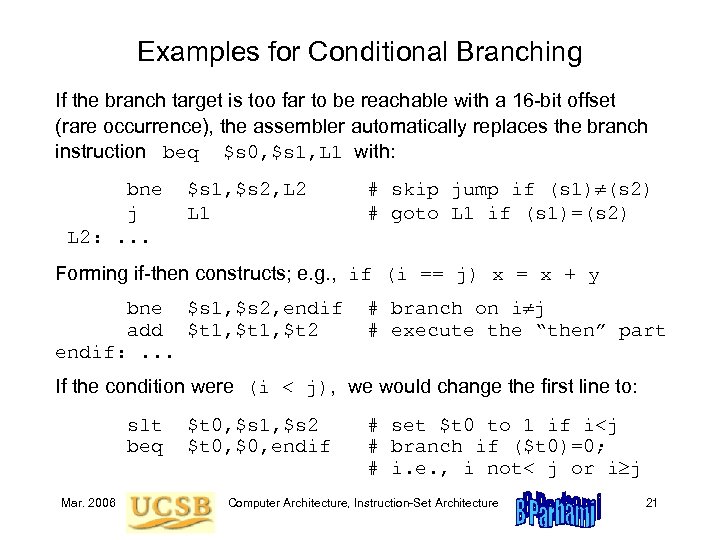

Examples for Conditional Branching If the branch target is too far to be reachable with a 16 -bit offset (rare occurrence), the assembler automatically replaces the branch instruction beq $s 0, $s 1, L 1 with: bne j L 2: . . . $s 1, $s 2, L 2 L 1 # skip jump if (s 1) (s 2) # goto L 1 if (s 1)=(s 2) Forming if-then constructs; e. g. , if (i == j) x = x + y bne $s 1, $s 2, endif add $t 1, $t 2 endif: . . . # branch on i j # execute the “then” part If the condition were (i < j), we would change the first line to: slt beq Mar. 2006 $t 0, $s 1, $s 2 $t 0, $0, endif # set $t 0 to 1 if i

Examples for Conditional Branching If the branch target is too far to be reachable with a 16 -bit offset (rare occurrence), the assembler automatically replaces the branch instruction beq $s 0, $s 1, L 1 with: bne j L 2: . . . $s 1, $s 2, L 2 L 1 # skip jump if (s 1) (s 2) # goto L 1 if (s 1)=(s 2) Forming if-then constructs; e. g. , if (i == j) x = x + y bne $s 1, $s 2, endif add $t 1, $t 2 endif: . . . # branch on i j # execute the “then” part If the condition were (i < j), we would change the first line to: slt beq Mar. 2006 $t 0, $s 1, $s 2 $t 0, $0, endif # set $t 0 to 1 if i

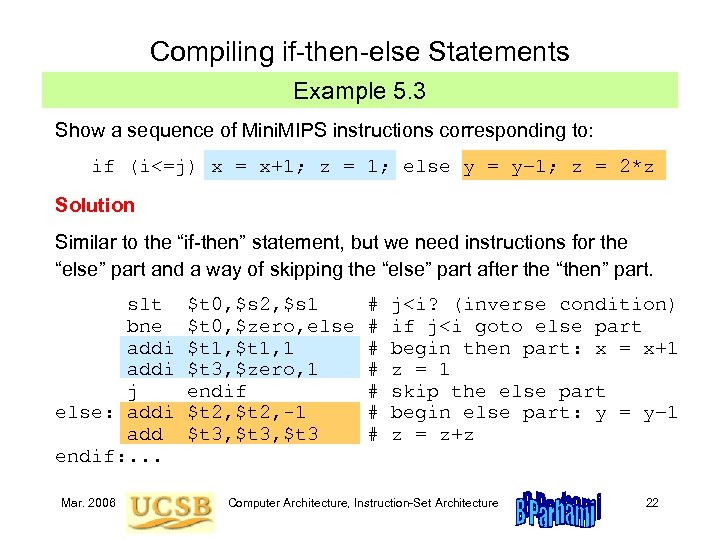

Compiling if-then-else Statements Example 5. 3 Show a sequence of Mini. MIPS instructions corresponding to: if (i<=j) x = x+1; z = 1; else y = y– 1; z = 2*z Solution Similar to the “if-then” statement, but we need instructions for the “else” part and a way of skipping the “else” part after the “then” part. slt bne addi j else: addi add endif: . . . Mar. 2006 $t 0, $s 2, $s 1 $t 0, $zero, else $t 1, 1 $t 3, $zero, 1 endif $t 2, -1 $t 3, $t 3 # # # # j

Compiling if-then-else Statements Example 5. 3 Show a sequence of Mini. MIPS instructions corresponding to: if (i<=j) x = x+1; z = 1; else y = y– 1; z = 2*z Solution Similar to the “if-then” statement, but we need instructions for the “else” part and a way of skipping the “else” part after the “then” part. slt bne addi j else: addi add endif: . . . Mar. 2006 $t 0, $s 2, $s 1 $t 0, $zero, else $t 1, 1 $t 3, $zero, 1 endif $t 2, -1 $t 3, $t 3 # # # # j

5. 6 Addressing Modes Figure 5. 11 Schematic representation of addressing modes in Mini. MIPS. Mar. 2006 Computer Architecture, Instruction-Set Architecture 23

5. 6 Addressing Modes Figure 5. 11 Schematic representation of addressing modes in Mini. MIPS. Mar. 2006 Computer Architecture, Instruction-Set Architecture 23

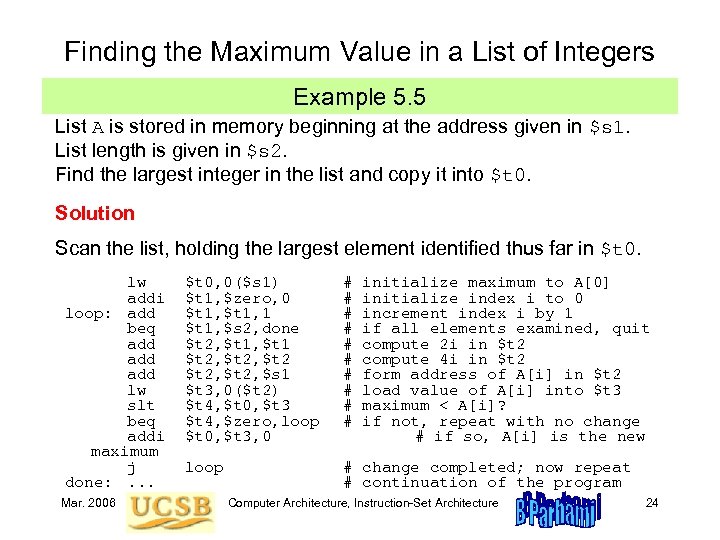

Finding the Maximum Value in a List of Integers Example 5. 5 List A is stored in memory beginning at the address given in $s 1. List length is given in $s 2. Find the largest integer in the list and copy it into $t 0. Solution Scan the list, holding the largest element identified thus far in $t 0. lw addi loop: add beq add add lw slt beq addi maximum j done: . . . Mar. 2006 $t 0, 0($s 1) $t 1, $zero, 0 $t 1, 1 $t 1, $s 2, done $t 2, $t 1 $t 2, $t 2, $s 1 $t 3, 0($t 2) $t 4, $t 0, $t 3 $t 4, $zero, loop $t 0, $t 3, 0 # # # # # initialize maximum to A[0] initialize index i to 0 increment index i by 1 if all elements examined, quit compute 2 i in $t 2 compute 4 i in $t 2 form address of A[i] in $t 2 load value of A[i] into $t 3 maximum < A[i]? if not, repeat with no change # if so, A[i] is the new loop # change completed; now repeat # continuation of the program Computer Architecture, Instruction-Set Architecture 24

Finding the Maximum Value in a List of Integers Example 5. 5 List A is stored in memory beginning at the address given in $s 1. List length is given in $s 2. Find the largest integer in the list and copy it into $t 0. Solution Scan the list, holding the largest element identified thus far in $t 0. lw addi loop: add beq add add lw slt beq addi maximum j done: . . . Mar. 2006 $t 0, 0($s 1) $t 1, $zero, 0 $t 1, 1 $t 1, $s 2, done $t 2, $t 1 $t 2, $t 2, $s 1 $t 3, 0($t 2) $t 4, $t 0, $t 3 $t 4, $zero, loop $t 0, $t 3, 0 # # # # # initialize maximum to A[0] initialize index i to 0 increment index i by 1 if all elements examined, quit compute 2 i in $t 2 compute 4 i in $t 2 form address of A[i] in $t 2 load value of A[i] into $t 3 maximum < A[i]? if not, repeat with no change # if so, A[i] is the new loop # change completed; now repeat # continuation of the program Computer Architecture, Instruction-Set Architecture 24

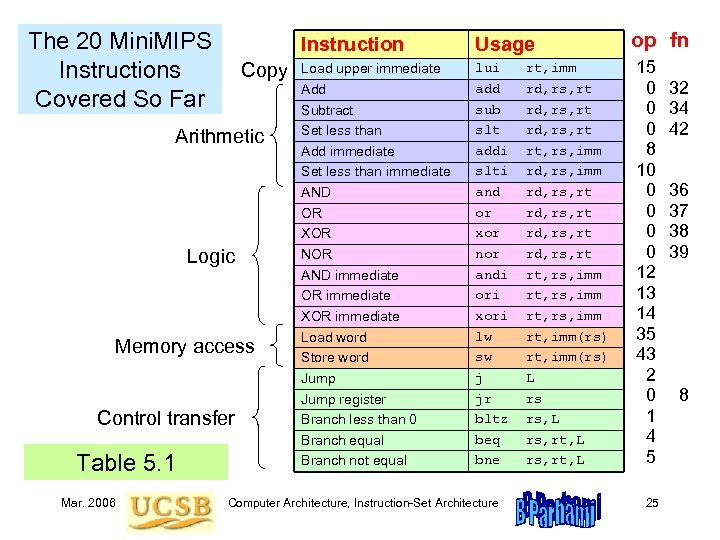

The 20 Mini. MIPS Instruction Copy Load upper immediate Instructions Add Covered So Far Subtract Arithmetic Logic Memory access Control transfer Table 5. 1 Mar. 2006 Set less than Add immediate Set less than immediate AND OR XOR NOR AND immediate OR immediate XOR immediate Load word Store word Jump register Branch less than 0 Branch equal Branch not equal Usage lui add sub slt addi slti and or xor nor andi ori xori lw sw j jr bltz beq bne Computer Architecture, Instruction-Set Architecture rt, imm rd, rs, rt rt, rs, imm rd, rs, rt rd, rs, rt rt, rs, imm rt, imm(rs) L rs rs, L rs, rt, L op fn 15 0 0 0 8 10 0 0 12 13 14 35 43 2 0 1 4 5 25 32 34 42 36 37 38 39 8

The 20 Mini. MIPS Instruction Copy Load upper immediate Instructions Add Covered So Far Subtract Arithmetic Logic Memory access Control transfer Table 5. 1 Mar. 2006 Set less than Add immediate Set less than immediate AND OR XOR NOR AND immediate OR immediate XOR immediate Load word Store word Jump register Branch less than 0 Branch equal Branch not equal Usage lui add sub slt addi slti and or xor nor andi ori xori lw sw j jr bltz beq bne Computer Architecture, Instruction-Set Architecture rt, imm rd, rs, rt rt, rs, imm rd, rs, rt rd, rs, rt rt, rs, imm rt, imm(rs) L rs rs, L rs, rt, L op fn 15 0 0 0 8 10 0 0 12 13 14 35 43 2 0 1 4 5 25 32 34 42 36 37 38 39 8

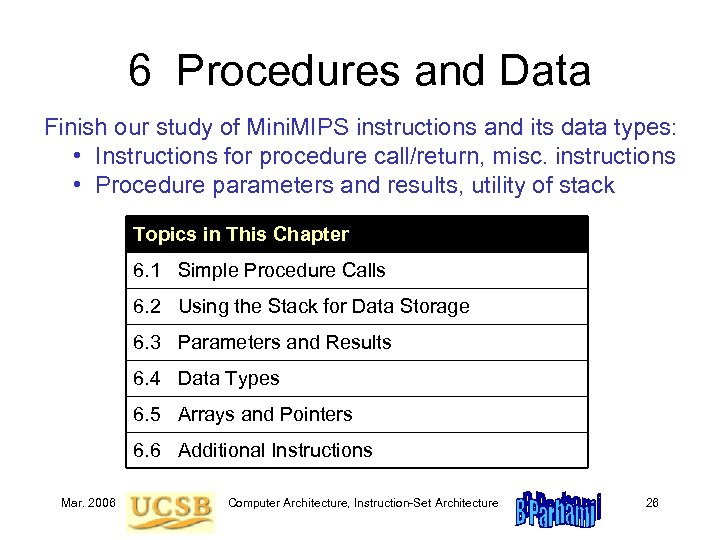

6 Procedures and Data Finish our study of Mini. MIPS instructions and its data types: • Instructions for procedure call/return, misc. instructions • Procedure parameters and results, utility of stack Topics in This Chapter 6. 1 Simple Procedure Calls 6. 2 Using the Stack for Data Storage 6. 3 Parameters and Results 6. 4 Data Types 6. 5 Arrays and Pointers 6. 6 Additional Instructions Mar. 2006 Computer Architecture, Instruction-Set Architecture 26

6 Procedures and Data Finish our study of Mini. MIPS instructions and its data types: • Instructions for procedure call/return, misc. instructions • Procedure parameters and results, utility of stack Topics in This Chapter 6. 1 Simple Procedure Calls 6. 2 Using the Stack for Data Storage 6. 3 Parameters and Results 6. 4 Data Types 6. 5 Arrays and Pointers 6. 6 Additional Instructions Mar. 2006 Computer Architecture, Instruction-Set Architecture 26

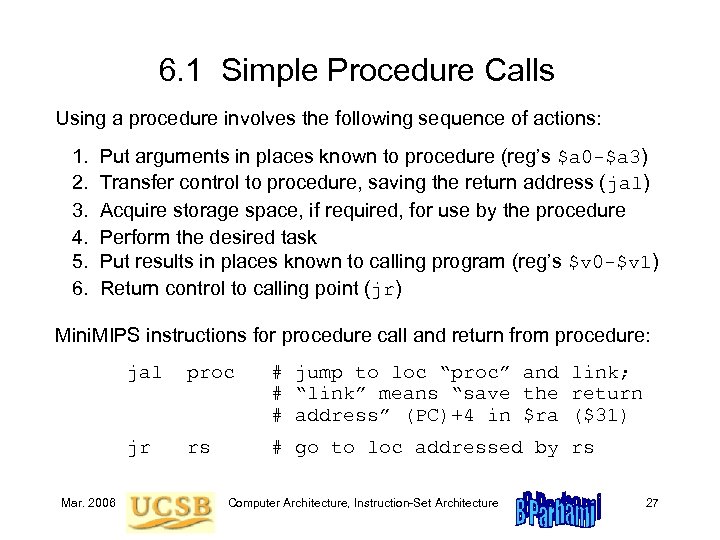

6. 1 Simple Procedure Calls Using a procedure involves the following sequence of actions: 1. Put arguments in places known to procedure (reg’s $a 0 -$a 3) 2. Transfer control to procedure, saving the return address (jal) 3. Acquire storage space, if required, for use by the procedure 4. Perform the desired task 5. Put results in places known to calling program (reg’s $v 0 -$v 1) 6. Return control to calling point (jr) Mini. MIPS instructions for procedure call and return from procedure: proc # jump to loc “proc” and link; # “link” means “save the return # address” (PC)+4 in $ra ($31) jr Mar. 2006 jal rs # go to loc addressed by rs Computer Architecture, Instruction-Set Architecture 27

6. 1 Simple Procedure Calls Using a procedure involves the following sequence of actions: 1. Put arguments in places known to procedure (reg’s $a 0 -$a 3) 2. Transfer control to procedure, saving the return address (jal) 3. Acquire storage space, if required, for use by the procedure 4. Perform the desired task 5. Put results in places known to calling program (reg’s $v 0 -$v 1) 6. Return control to calling point (jr) Mini. MIPS instructions for procedure call and return from procedure: proc # jump to loc “proc” and link; # “link” means “save the return # address” (PC)+4 in $ra ($31) jr Mar. 2006 jal rs # go to loc addressed by rs Computer Architecture, Instruction-Set Architecture 27

Illustrating a Procedure Call Figure 6. 1 Relationship between the main program and a procedure. Mar. 2006 Computer Architecture, Instruction-Set Architecture 28

Illustrating a Procedure Call Figure 6. 1 Relationship between the main program and a procedure. Mar. 2006 Computer Architecture, Instruction-Set Architecture 28

Recalling Register Conventions Figure 5. 2 Registers and data sizes in Mini. MIPS. Mar. 2006 Computer Architecture, Instruction-Set Architecture 29

Recalling Register Conventions Figure 5. 2 Registers and data sizes in Mini. MIPS. Mar. 2006 Computer Architecture, Instruction-Set Architecture 29

A Simple Mini. MIPS Procedure Example 6. 1 Procedure to find the absolute value of an integer. $v 0 |($a 0)| Solution The absolute value of x is –x if x < 0 and x otherwise. abs: sub $v 0, $zero, $a 0 bltz $a 0, done add $v 0, $a 0, $zero done: jr $ra # # # put -($a 0) in $v 0; in case ($a 0) < 0 if ($a 0)<0 then done else put ($a 0) in $v 0 return to calling program In practice, we seldom use such short procedures because of the overhead that they entail. In this example, we have 3 -4 instructions of overhead for 3 instructions of useful computation. Mar. 2006 Computer Architecture, Instruction-Set Architecture 30

A Simple Mini. MIPS Procedure Example 6. 1 Procedure to find the absolute value of an integer. $v 0 |($a 0)| Solution The absolute value of x is –x if x < 0 and x otherwise. abs: sub $v 0, $zero, $a 0 bltz $a 0, done add $v 0, $a 0, $zero done: jr $ra # # # put -($a 0) in $v 0; in case ($a 0) < 0 if ($a 0)<0 then done else put ($a 0) in $v 0 return to calling program In practice, we seldom use such short procedures because of the overhead that they entail. In this example, we have 3 -4 instructions of overhead for 3 instructions of useful computation. Mar. 2006 Computer Architecture, Instruction-Set Architecture 30

Nested Procedure Calls Text version is incorrect Figure 6. 2 Example of nested procedure calls. Mar. 2006 Computer Architecture, Instruction-Set Architecture 31

Nested Procedure Calls Text version is incorrect Figure 6. 2 Example of nested procedure calls. Mar. 2006 Computer Architecture, Instruction-Set Architecture 31

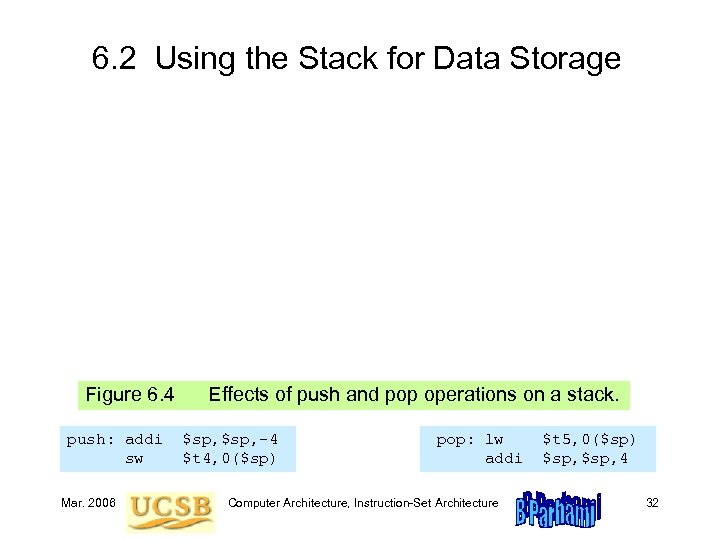

6. 2 Using the Stack for Data Storage Figure 6. 4 Effects of push and pop operations on a stack. push: addi sw Mar. 2006 $sp, -4 $t 4, 0($sp) pop: lw addi Computer Architecture, Instruction-Set Architecture $t 5, 0($sp) $sp, 4 32

6. 2 Using the Stack for Data Storage Figure 6. 4 Effects of push and pop operations on a stack. push: addi sw Mar. 2006 $sp, -4 $t 4, 0($sp) pop: lw addi Computer Architecture, Instruction-Set Architecture $t 5, 0($sp) $sp, 4 32

Memory Map in Mini. MIPS 80000000 Figure 6. 3 Overview of the memory address space in Mini. MIPS. Mar. 2006 Computer Architecture, Instruction-Set Architecture 33

Memory Map in Mini. MIPS 80000000 Figure 6. 3 Overview of the memory address space in Mini. MIPS. Mar. 2006 Computer Architecture, Instruction-Set Architecture 33

6. 3 Parameters and Results Stack allows us to pass/return an arbitrary number of values Figure 6. 5 Use of the stack by a procedure. Mar. 2006 Computer Architecture, Instruction-Set Architecture 34

6. 3 Parameters and Results Stack allows us to pass/return an arbitrary number of values Figure 6. 5 Use of the stack by a procedure. Mar. 2006 Computer Architecture, Instruction-Set Architecture 34

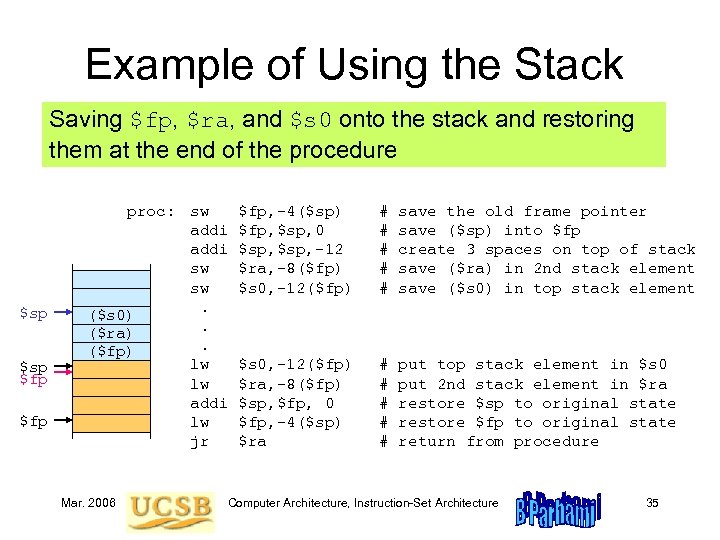

Example of Using the Stack Saving $fp, $ra, and $s 0 onto the stack and restoring them at the end of the procedure $sp $fp proc: sw addi sw sw. ($s 0). ($ra). ($fp) lw lw addi lw jr Mar. 2006 $fp, -4($sp) $fp, $sp, 0 $sp, – 12 $ra, -8($fp) $s 0, -12($fp) # # # save the old frame pointer save ($sp) into $fp create 3 spaces on top of stack save ($ra) in 2 nd stack element save ($s 0) in top stack element $s 0, -12($fp) $ra, -8($fp) $sp, $fp, 0 $fp, -4($sp) $ra # # # put top stack element in $s 0 put 2 nd stack element in $ra restore $sp to original state restore $fp to original state return from procedure Computer Architecture, Instruction-Set Architecture 35

Example of Using the Stack Saving $fp, $ra, and $s 0 onto the stack and restoring them at the end of the procedure $sp $fp proc: sw addi sw sw. ($s 0). ($ra). ($fp) lw lw addi lw jr Mar. 2006 $fp, -4($sp) $fp, $sp, 0 $sp, – 12 $ra, -8($fp) $s 0, -12($fp) # # # save the old frame pointer save ($sp) into $fp create 3 spaces on top of stack save ($ra) in 2 nd stack element save ($s 0) in top stack element $s 0, -12($fp) $ra, -8($fp) $sp, $fp, 0 $fp, -4($sp) $ra # # # put top stack element in $s 0 put 2 nd stack element in $ra restore $sp to original state restore $fp to original state return from procedure Computer Architecture, Instruction-Set Architecture 35

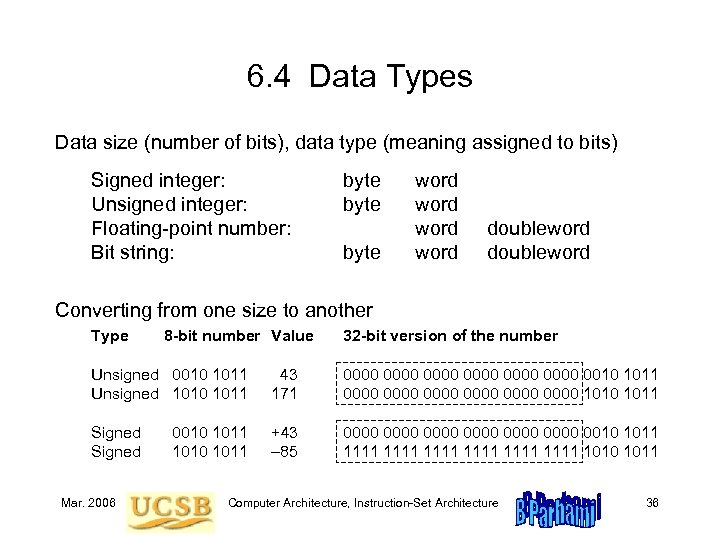

6. 4 Data Types Data size (number of bits), data type (meaning assigned to bits) Signed integer: Unsigned integer: Floating-point number: Bit string: byte word doubleword Converting from one size to another Type 8 -bit number Value 32 -bit version of the number Unsigned 0010 1011 Unsigned 1010 1011 43 171 0000 0000 0010 1011 0000 0000 1010 1011 Signed 0010 1011 Signed 1010 1011 +43 – 85 0000 0000 0010 1011 1111 1111 1010 1011 Mar. 2006 Computer Architecture, Instruction-Set Architecture 36

6. 4 Data Types Data size (number of bits), data type (meaning assigned to bits) Signed integer: Unsigned integer: Floating-point number: Bit string: byte word doubleword Converting from one size to another Type 8 -bit number Value 32 -bit version of the number Unsigned 0010 1011 Unsigned 1010 1011 43 171 0000 0000 0010 1011 0000 0000 1010 1011 Signed 0010 1011 Signed 1010 1011 +43 – 85 0000 0000 0010 1011 1111 1111 1010 1011 Mar. 2006 Computer Architecture, Instruction-Set Architecture 36

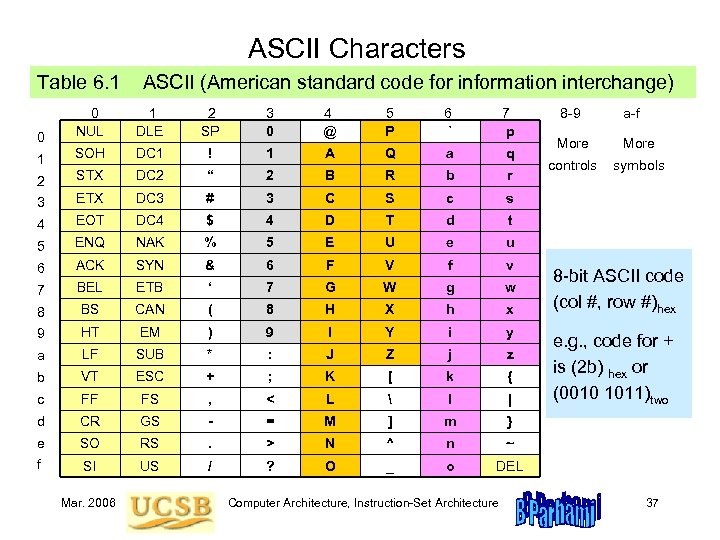

ASCII Characters Table 6. 1 ASCII (American standard code for information interchange) 2 0 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 -9 a-f NUL DLE SP 0 @ P ` p More SOH DC 1 ! 1 A Q a q controls symbols STX DC 2 “ 2 B R b r 3 ETX DC 3 # 3 C S c s 4 EOT DC 4 $ 4 D T d t 5 ENQ NAK % 5 E U e u 6 ACK SYN & 6 F V f v 7 BEL ETB ‘ 7 G W g w 8 BS CAN ( 8 H X h x 9 HT EM ) 9 I Y i y a LF SUB * : J Z j z b VT ESC + ; K [ k { c FF FS , < L l | d CR GS - = M ] m } e SO RS . > N ^ n ~ f SI US / ? O _ o DEL 0 1 Mar. 2006 Computer Architecture, Instruction-Set Architecture 8 -bit ASCII code (col #, row #)hex e. g. , code for + is (2 b) hex or (0010 1011)two 37

ASCII Characters Table 6. 1 ASCII (American standard code for information interchange) 2 0 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 -9 a-f NUL DLE SP 0 @ P ` p More SOH DC 1 ! 1 A Q a q controls symbols STX DC 2 “ 2 B R b r 3 ETX DC 3 # 3 C S c s 4 EOT DC 4 $ 4 D T d t 5 ENQ NAK % 5 E U e u 6 ACK SYN & 6 F V f v 7 BEL ETB ‘ 7 G W g w 8 BS CAN ( 8 H X h x 9 HT EM ) 9 I Y i y a LF SUB * : J Z j z b VT ESC + ; K [ k { c FF FS , < L l | d CR GS - = M ] m } e SO RS . > N ^ n ~ f SI US / ? O _ o DEL 0 1 Mar. 2006 Computer Architecture, Instruction-Set Architecture 8 -bit ASCII code (col #, row #)hex e. g. , code for + is (2 b) hex or (0010 1011)two 37

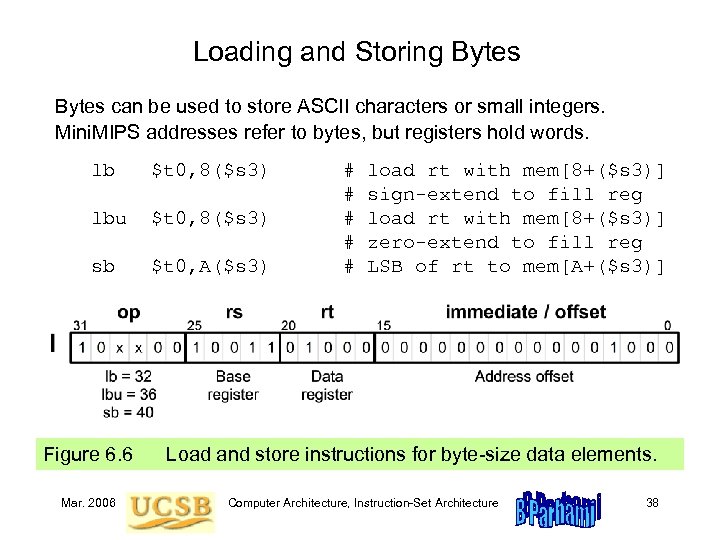

Loading and Storing Bytes can be used to store ASCII characters or small integers. Mini. MIPS addresses refer to bytes, but registers hold words. lb $t 0, 8($s 3) lbu $t 0, 8($s 3) sb $t 0, A($s 3) # # # load rt with mem[8+($s 3)] sign-extend to fill reg load rt with mem[8+($s 3)] zero-extend to fill reg LSB of rt to mem[A+($s 3)] Figure 6. 6 Load and store instructions for byte-size data elements. Mar. 2006 Computer Architecture, Instruction-Set Architecture 38

Loading and Storing Bytes can be used to store ASCII characters or small integers. Mini. MIPS addresses refer to bytes, but registers hold words. lb $t 0, 8($s 3) lbu $t 0, 8($s 3) sb $t 0, A($s 3) # # # load rt with mem[8+($s 3)] sign-extend to fill reg load rt with mem[8+($s 3)] zero-extend to fill reg LSB of rt to mem[A+($s 3)] Figure 6. 6 Load and store instructions for byte-size data elements. Mar. 2006 Computer Architecture, Instruction-Set Architecture 38

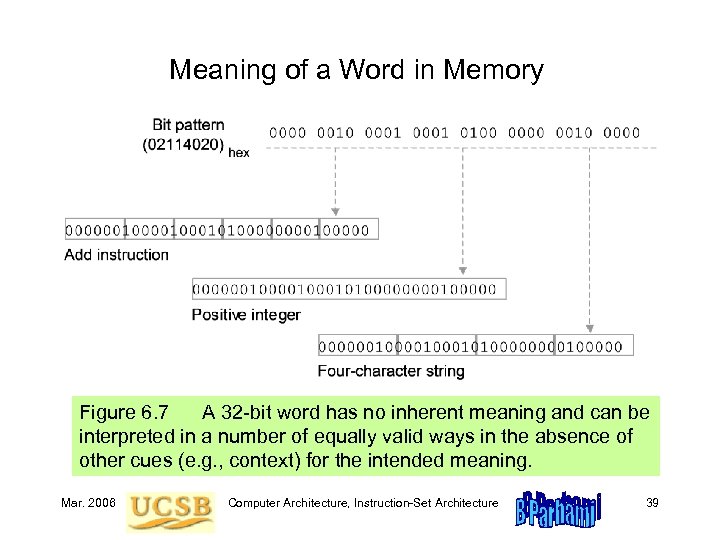

Meaning of a Word in Memory Figure 6. 7 A 32 -bit word has no inherent meaning and can be interpreted in a number of equally valid ways in the absence of other cues (e. g. , context) for the intended meaning. Mar. 2006 Computer Architecture, Instruction-Set Architecture 39

Meaning of a Word in Memory Figure 6. 7 A 32 -bit word has no inherent meaning and can be interpreted in a number of equally valid ways in the absence of other cues (e. g. , context) for the intended meaning. Mar. 2006 Computer Architecture, Instruction-Set Architecture 39

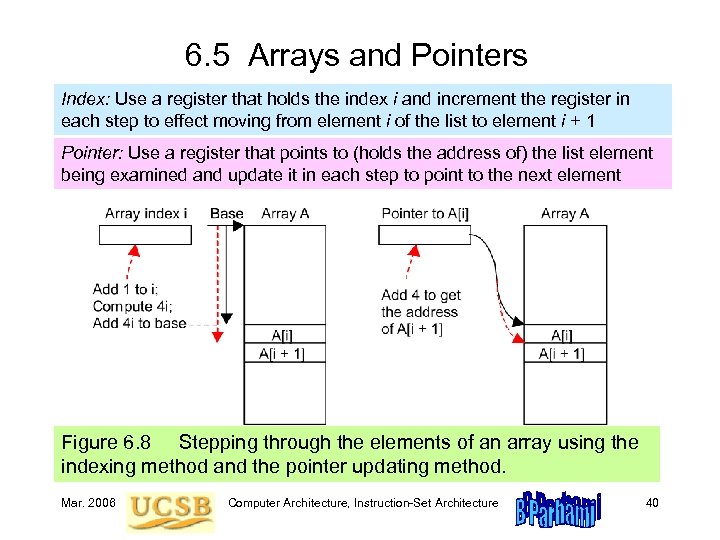

6. 5 Arrays and Pointers Index: Use a register that holds the index i and increment the register in each step to effect moving from element i of the list to element i + 1 Pointer: Use a register that points to (holds the address of) the list element being examined and update it in each step to point to the next element Figure 6. 8 Stepping through the elements of an array using the indexing method and the pointer updating method. Mar. 2006 Computer Architecture, Instruction-Set Architecture 40

6. 5 Arrays and Pointers Index: Use a register that holds the index i and increment the register in each step to effect moving from element i of the list to element i + 1 Pointer: Use a register that points to (holds the address of) the list element being examined and update it in each step to point to the next element Figure 6. 8 Stepping through the elements of an array using the indexing method and the pointer updating method. Mar. 2006 Computer Architecture, Instruction-Set Architecture 40

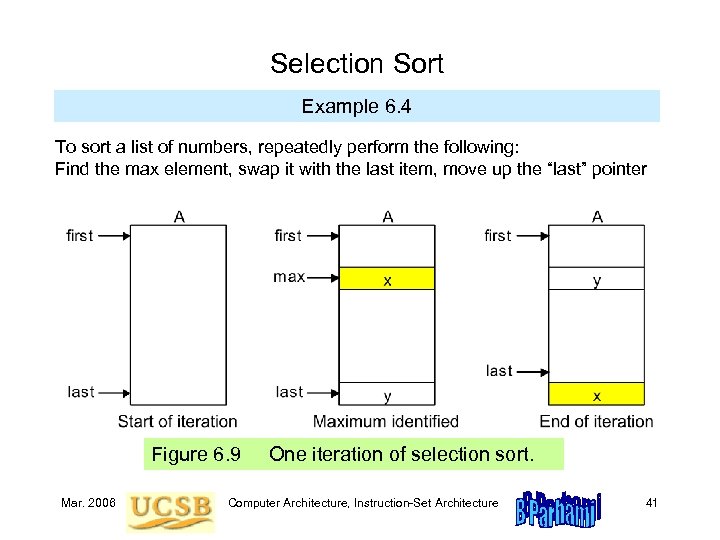

Selection Sort Example 6. 4 To sort a list of numbers, repeatedly perform the following: Find the max element, swap it with the last item, move up the “last” pointer Figure 6. 9 One iteration of selection sort. Mar. 2006 Computer Architecture, Instruction-Set Architecture 41

Selection Sort Example 6. 4 To sort a list of numbers, repeatedly perform the following: Find the max element, swap it with the last item, move up the “last” pointer Figure 6. 9 One iteration of selection sort. Mar. 2006 Computer Architecture, Instruction-Set Architecture 41

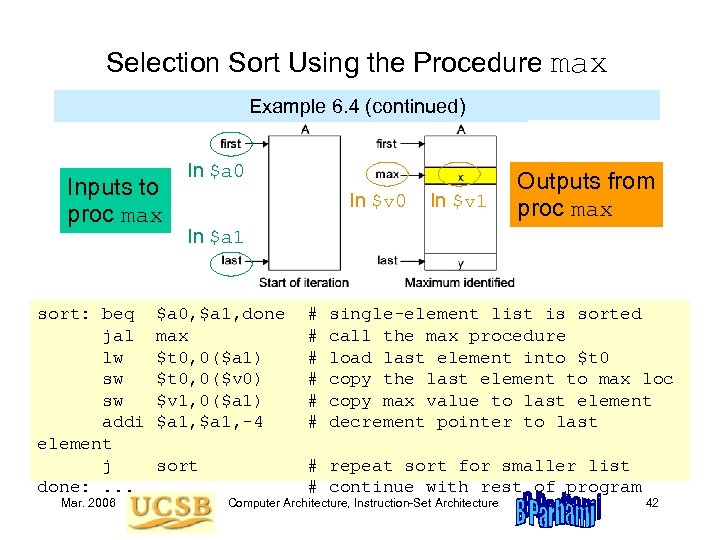

Selection Sort Using the Procedure max Example 6. 4 (continued) Inputs to proc max sort: beq jal lw sw sw addi element j done: . . . Mar. 2006 In $a 0 In $v 1 Outputs from proc max In $a 1 $a 0, $a 1, done max $t 0, 0($a 1) $t 0, 0($v 0) $v 1, 0($a 1) $a 1, -4 # # # single-element list is sorted call the max procedure load last element into $t 0 copy the last element to max loc copy max value to last element decrement pointer to last sort # repeat sort for smaller list # continue with rest of program Computer Architecture, Instruction-Set Architecture 42

Selection Sort Using the Procedure max Example 6. 4 (continued) Inputs to proc max sort: beq jal lw sw sw addi element j done: . . . Mar. 2006 In $a 0 In $v 1 Outputs from proc max In $a 1 $a 0, $a 1, done max $t 0, 0($a 1) $t 0, 0($v 0) $v 1, 0($a 1) $a 1, -4 # # # single-element list is sorted call the max procedure load last element into $t 0 copy the last element to max loc copy max value to last element decrement pointer to last sort # repeat sort for smaller list # continue with rest of program Computer Architecture, Instruction-Set Architecture 42

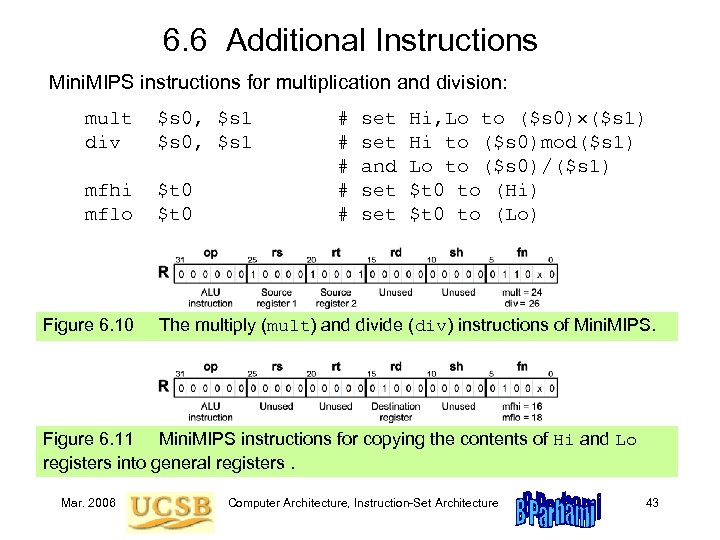

6. 6 Additional Instructions Mini. MIPS instructions for multiplication and division: mult div $s 0, $s 1 mfhi mflo $t 0 # # # set and set Hi, Lo to ($s 0) ($s 1) Hi to ($s 0)mod($s 1) Lo to ($s 0)/($s 1) $t 0 to (Hi) $t 0 to (Lo) Figure 6. 10 The multiply (mult) and divide (div) instructions of Mini. MIPS. Figure 6. 11 Mini. MIPS instructions for copying the contents of Hi and Lo registers into general registers. Mar. 2006 Computer Architecture, Instruction-Set Architecture 43

6. 6 Additional Instructions Mini. MIPS instructions for multiplication and division: mult div $s 0, $s 1 mfhi mflo $t 0 # # # set and set Hi, Lo to ($s 0) ($s 1) Hi to ($s 0)mod($s 1) Lo to ($s 0)/($s 1) $t 0 to (Hi) $t 0 to (Lo) Figure 6. 10 The multiply (mult) and divide (div) instructions of Mini. MIPS. Figure 6. 11 Mini. MIPS instructions for copying the contents of Hi and Lo registers into general registers. Mar. 2006 Computer Architecture, Instruction-Set Architecture 43

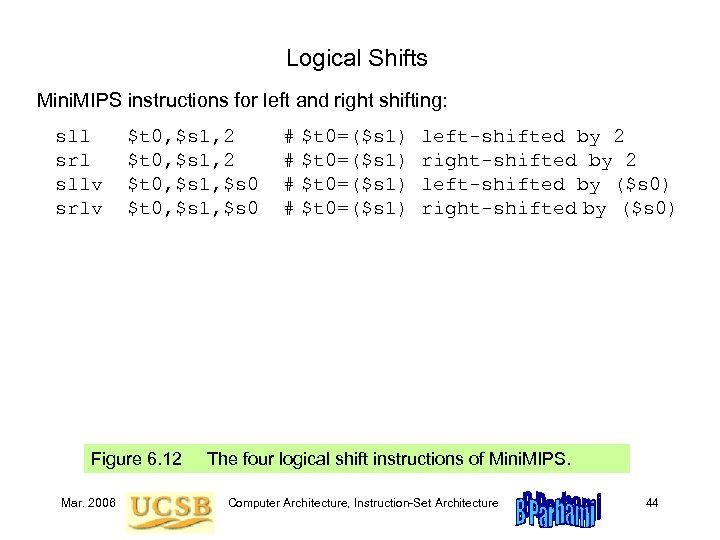

Logical Shifts Mini. MIPS instructions for left and right shifting: sll srl sllv srlv $t 0, $s 1, 2 $t 0, $s 1, $s 0 # # $t 0=($s 1) left-shifted by 2 right-shifted by 2 left-shifted by ($s 0) right-shifted by ($s 0) Figure 6. 12 The four logical shift instructions of Mini. MIPS. Mar. 2006 Computer Architecture, Instruction-Set Architecture 44

Logical Shifts Mini. MIPS instructions for left and right shifting: sll srl sllv srlv $t 0, $s 1, 2 $t 0, $s 1, $s 0 # # $t 0=($s 1) left-shifted by 2 right-shifted by 2 left-shifted by ($s 0) right-shifted by ($s 0) Figure 6. 12 The four logical shift instructions of Mini. MIPS. Mar. 2006 Computer Architecture, Instruction-Set Architecture 44

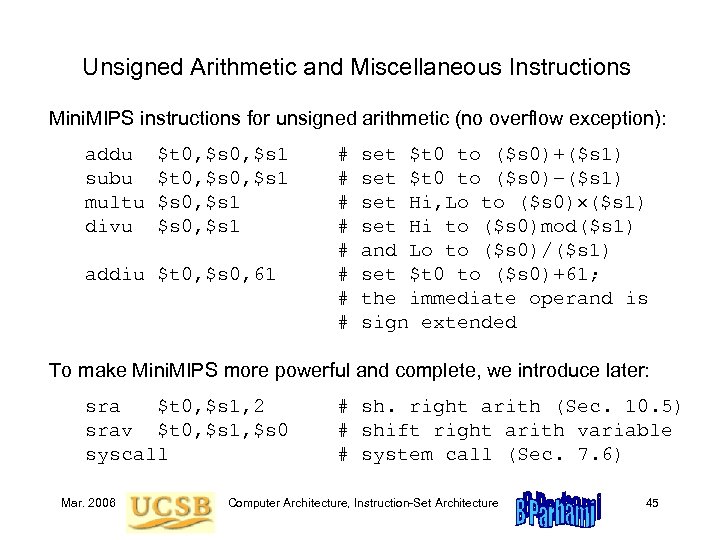

Unsigned Arithmetic and Miscellaneous Instructions Mini. MIPS instructions for unsigned arithmetic (no overflow exception): addu subu multu divu $t 0, $s 1 $s 0, $s 1 addiu $t 0, $s 0, 61 # # # # set $t 0 to ($s 0)+($s 1) set $t 0 to ($s 0)–($s 1) set Hi, Lo to ($s 0) ($s 1) set Hi to ($s 0)mod($s 1) and Lo to ($s 0)/($s 1) set $t 0 to ($s 0)+61; the immediate operand is sign extended To make Mini. MIPS more powerful and complete, we introduce later: sra $t 0, $s 1, 2 srav $t 0, $s 1, $s 0 syscall Mar. 2006 # sh. right arith (Sec. 10. 5) # shift right arith variable # system call (Sec. 7. 6) Computer Architecture, Instruction-Set Architecture 45

Unsigned Arithmetic and Miscellaneous Instructions Mini. MIPS instructions for unsigned arithmetic (no overflow exception): addu subu multu divu $t 0, $s 1 $s 0, $s 1 addiu $t 0, $s 0, 61 # # # # set $t 0 to ($s 0)+($s 1) set $t 0 to ($s 0)–($s 1) set Hi, Lo to ($s 0) ($s 1) set Hi to ($s 0)mod($s 1) and Lo to ($s 0)/($s 1) set $t 0 to ($s 0)+61; the immediate operand is sign extended To make Mini. MIPS more powerful and complete, we introduce later: sra $t 0, $s 1, 2 srav $t 0, $s 1, $s 0 syscall Mar. 2006 # sh. right arith (Sec. 10. 5) # shift right arith variable # system call (Sec. 7. 6) Computer Architecture, Instruction-Set Architecture 45

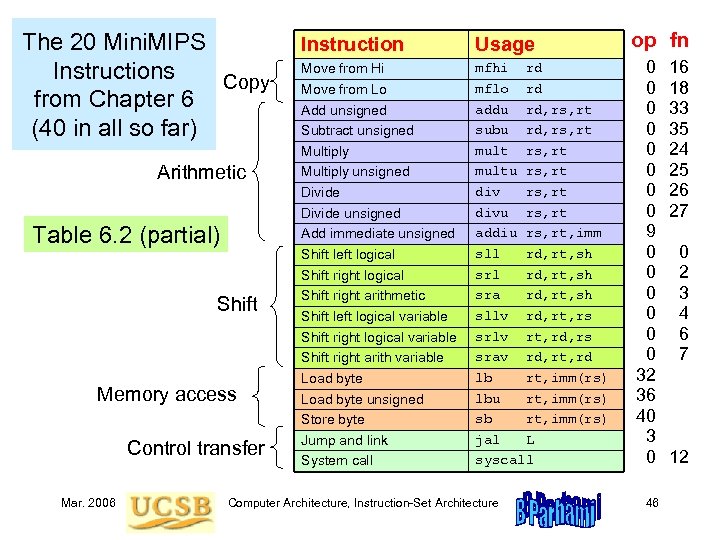

The 20 Mini. MIPS Instructions Copy from Chapter 6 (40 in all so far) Arithmetic Table 6. 2 (partial) Shift Memory access Control transfer Mar. 2006 Instruction Usage Move from Hi Move from Lo Add unsigned Subtract unsigned Multiply unsigned Divide unsigned Add immediate unsigned Shift left logical Shift right arithmetic Shift left logical variable Shift right arith variable Load byte unsigned Store byte Jump and link System call mfhi rd mflo rd addu rd, rs, rt subu rd, rs, rt multu rs, rt divu rs, rt addiu rs, rt, imm sll rd, rt, sh sra rd, rt, sh sllv rd, rt, rs srlv rt, rd, rs srav rd, rt, rd lb rt, imm(rs) lbu rt, imm(rs) sb rt, imm(rs) jal L syscall Computer Architecture, Instruction-Set Architecture op fn 0 0 0 0 9 0 0 0 32 36 40 3 0 46 16 18 33 35 24 25 26 27 0 2 3 4 6 7 12

The 20 Mini. MIPS Instructions Copy from Chapter 6 (40 in all so far) Arithmetic Table 6. 2 (partial) Shift Memory access Control transfer Mar. 2006 Instruction Usage Move from Hi Move from Lo Add unsigned Subtract unsigned Multiply unsigned Divide unsigned Add immediate unsigned Shift left logical Shift right arithmetic Shift left logical variable Shift right arith variable Load byte unsigned Store byte Jump and link System call mfhi rd mflo rd addu rd, rs, rt subu rd, rs, rt multu rs, rt divu rs, rt addiu rs, rt, imm sll rd, rt, sh sra rd, rt, sh sllv rd, rt, rs srlv rt, rd, rs srav rd, rt, rd lb rt, imm(rs) lbu rt, imm(rs) sb rt, imm(rs) jal L syscall Computer Architecture, Instruction-Set Architecture op fn 0 0 0 0 9 0 0 0 32 36 40 3 0 46 16 18 33 35 24 25 26 27 0 2 3 4 6 7 12

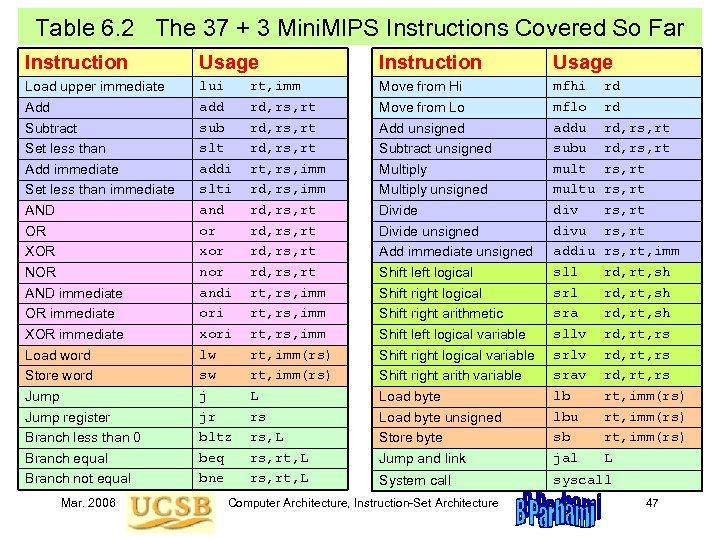

Table 6. 2 The 37 + 3 Mini. MIPS Instructions Covered So Far Instruction Usage Load upper immediate Add Subtract Set less than Add immediate Set less than immediate AND OR XOR NOR AND immediate OR immediate XOR immediate Load word Store word Jump register Branch less than 0 Branch equal Branch not equal lui add sub slt addi slti and or xor nor andi ori xori lw sw j jr bltz beq bne Move from Hi Move from Lo Add unsigned Subtract unsigned Multiply unsigned Divide unsigned Add immediate unsigned Shift left logical Shift right arithmetic Shift left logical variable Shift right arith variable Load byte unsigned Store byte Jump and link mfhi mflo addu subu multu divu addiu sll sra sllv srav lb lbu sb jal System call syscall Mar. 2006 rt, imm rd, rs, rt rt, rs, imm rd, rs, rt rd, rs, rt rt, rs, imm rt, imm(rs) L rs rs, L rs, rt, L Computer Architecture, Instruction-Set Architecture rd rd rd, rs, rt rs, rt, imm rd, rt, sh rd, rt, rs rt, imm(rs) L 47

Table 6. 2 The 37 + 3 Mini. MIPS Instructions Covered So Far Instruction Usage Load upper immediate Add Subtract Set less than Add immediate Set less than immediate AND OR XOR NOR AND immediate OR immediate XOR immediate Load word Store word Jump register Branch less than 0 Branch equal Branch not equal lui add sub slt addi slti and or xor nor andi ori xori lw sw j jr bltz beq bne Move from Hi Move from Lo Add unsigned Subtract unsigned Multiply unsigned Divide unsigned Add immediate unsigned Shift left logical Shift right arithmetic Shift left logical variable Shift right arith variable Load byte unsigned Store byte Jump and link mfhi mflo addu subu multu divu addiu sll sra sllv srav lb lbu sb jal System call syscall Mar. 2006 rt, imm rd, rs, rt rt, rs, imm rd, rs, rt rd, rs, rt rt, rs, imm rt, imm(rs) L rs rs, L rs, rt, L Computer Architecture, Instruction-Set Architecture rd rd rd, rs, rt rs, rt, imm rd, rt, sh rd, rt, rs rt, imm(rs) L 47

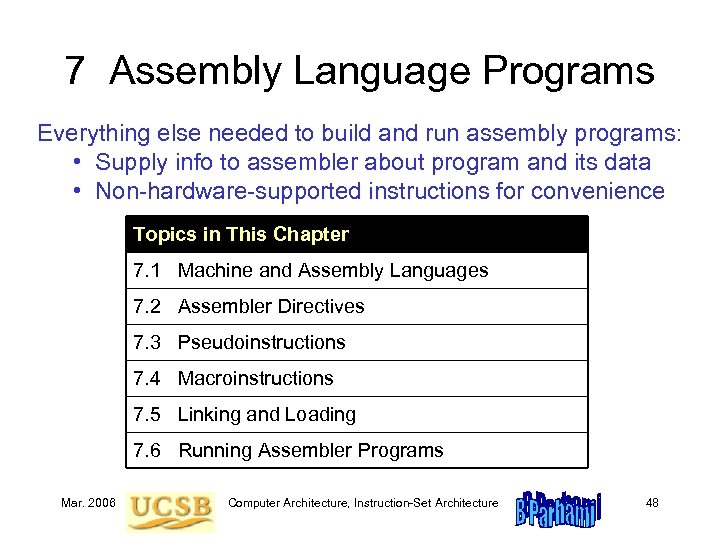

7 Assembly Language Programs Everything else needed to build and run assembly programs: • Supply info to assembler about program and its data • Non-hardware-supported instructions for convenience Topics in This Chapter 7. 1 Machine and Assembly Languages 7. 2 Assembler Directives 7. 3 Pseudoinstructions 7. 4 Macroinstructions 7. 5 Linking and Loading 7. 6 Running Assembler Programs Mar. 2006 Computer Architecture, Instruction-Set Architecture 48

7 Assembly Language Programs Everything else needed to build and run assembly programs: • Supply info to assembler about program and its data • Non-hardware-supported instructions for convenience Topics in This Chapter 7. 1 Machine and Assembly Languages 7. 2 Assembler Directives 7. 3 Pseudoinstructions 7. 4 Macroinstructions 7. 5 Linking and Loading 7. 6 Running Assembler Programs Mar. 2006 Computer Architecture, Instruction-Set Architecture 48

7. 1 Machine and Assembly Languages Figure 7. 1 Steps in transforming an assembly language program to an executable program residing in memory. Mar. 2006 Computer Architecture, Instruction-Set Architecture 49

7. 1 Machine and Assembly Languages Figure 7. 1 Steps in transforming an assembly language program to an executable program residing in memory. Mar. 2006 Computer Architecture, Instruction-Set Architecture 49

Symbol Table Figure 7. 2 An assembly-language program, its machine-language version, and the symbol table created during the assembly process. Mar. 2006 Computer Architecture, Instruction-Set Architecture 50

Symbol Table Figure 7. 2 An assembly-language program, its machine-language version, and the symbol table created during the assembly process. Mar. 2006 Computer Architecture, Instruction-Set Architecture 50

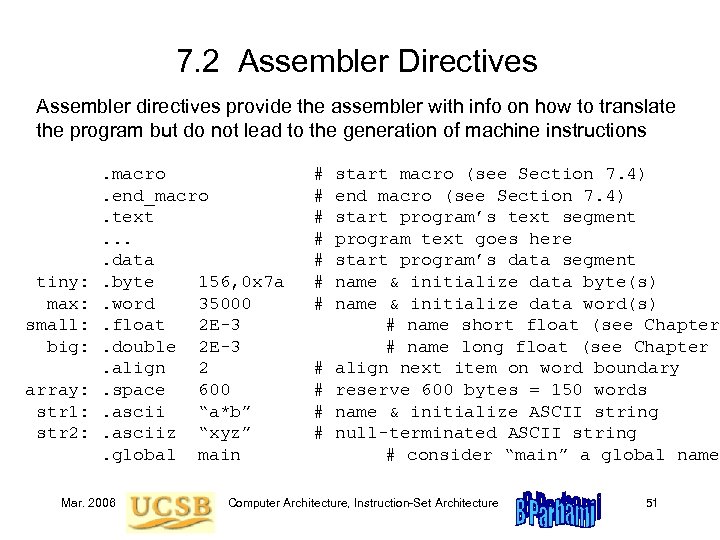

7. 2 Assembler Directives Assembler directives provide the assembler with info on how to translate the program but do not lead to the generation of machine instructions tiny: max: small: big: array: str 1: str 2: . macro. end_macro. text. . data. byte 156, 0 x 7 a. word 35000. float 2 E-3. double 2 E-3. align 2. space 600. ascii “a*b”. asciiz “xyz”. global main Mar. 2006 # # # start macro (see Section 7. 4) end macro (see Section 7. 4) start program’s text segment program text goes here start program’s data segment name & initialize data byte(s) name & initialize data word(s) # name short float (see Chapter # name long float (see Chapter align next item on word boundary reserve 600 bytes = 150 words name & initialize ASCII string null-terminated ASCII string # consider “main” a global name Computer Architecture, Instruction-Set Architecture 51

7. 2 Assembler Directives Assembler directives provide the assembler with info on how to translate the program but do not lead to the generation of machine instructions tiny: max: small: big: array: str 1: str 2: . macro. end_macro. text. . data. byte 156, 0 x 7 a. word 35000. float 2 E-3. double 2 E-3. align 2. space 600. ascii “a*b”. asciiz “xyz”. global main Mar. 2006 # # # start macro (see Section 7. 4) end macro (see Section 7. 4) start program’s text segment program text goes here start program’s data segment name & initialize data byte(s) name & initialize data word(s) # name short float (see Chapter # name long float (see Chapter align next item on word boundary reserve 600 bytes = 150 words name & initialize ASCII string null-terminated ASCII string # consider “main” a global name Computer Architecture, Instruction-Set Architecture 51

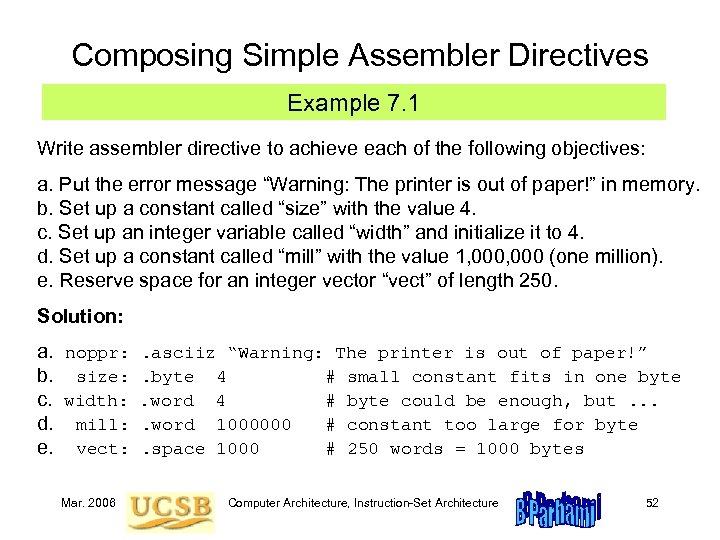

Composing Simple Assembler Directives Example 7. 1 Write assembler directive to achieve each of the following objectives: a. Put the error message “Warning: The printer is out of paper!” in memory. b. Set up a constant called “size” with the value 4. c. Set up an integer variable called “width” and initialize it to 4. d. Set up a constant called “mill” with the value 1, 000 (one million). e. Reserve space for an integer vector “vect” of length 250. Solution: a. noppr: b. size: c. width: d. mill: e. vect: Mar. 2006 . asciiz “Warning: The printer is out of paper!”. byte 4 # small constant fits in one byte. word 4 # byte could be enough, but. . word 1000000 # constant too large for byte. space 1000 # 250 words = 1000 bytes Computer Architecture, Instruction-Set Architecture 52

Composing Simple Assembler Directives Example 7. 1 Write assembler directive to achieve each of the following objectives: a. Put the error message “Warning: The printer is out of paper!” in memory. b. Set up a constant called “size” with the value 4. c. Set up an integer variable called “width” and initialize it to 4. d. Set up a constant called “mill” with the value 1, 000 (one million). e. Reserve space for an integer vector “vect” of length 250. Solution: a. noppr: b. size: c. width: d. mill: e. vect: Mar. 2006 . asciiz “Warning: The printer is out of paper!”. byte 4 # small constant fits in one byte. word 4 # byte could be enough, but. . word 1000000 # constant too large for byte. space 1000 # 250 words = 1000 bytes Computer Architecture, Instruction-Set Architecture 52

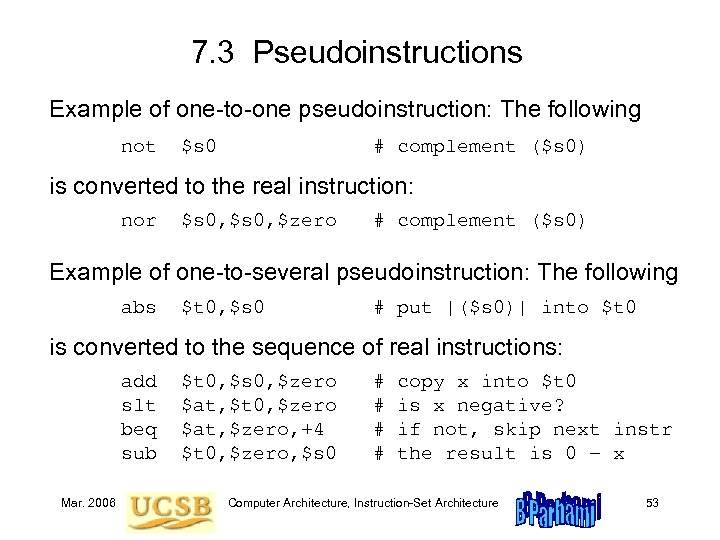

7. 3 Pseudoinstructions Example of one-to-one pseudoinstruction: The following not $s 0 # complement ($s 0) is converted to the real instruction: nor $s 0, $zero # complement ($s 0) Example of one-to-several pseudoinstruction: The following abs $t 0, $s 0 # put |($s 0)| into $t 0 is converted to the sequence of real instructions: add slt beq sub Mar. 2006 $t 0, $s 0, $zero $at, $t 0, $zero $at, $zero, +4 $t 0, $zero, $s 0 # # copy x into $t 0 is x negative? if not, skip next instr the result is 0 – x Computer Architecture, Instruction-Set Architecture 53

7. 3 Pseudoinstructions Example of one-to-one pseudoinstruction: The following not $s 0 # complement ($s 0) is converted to the real instruction: nor $s 0, $zero # complement ($s 0) Example of one-to-several pseudoinstruction: The following abs $t 0, $s 0 # put |($s 0)| into $t 0 is converted to the sequence of real instructions: add slt beq sub Mar. 2006 $t 0, $s 0, $zero $at, $t 0, $zero $at, $zero, +4 $t 0, $zero, $s 0 # # copy x into $t 0 is x negative? if not, skip next instr the result is 0 – x Computer Architecture, Instruction-Set Architecture 53

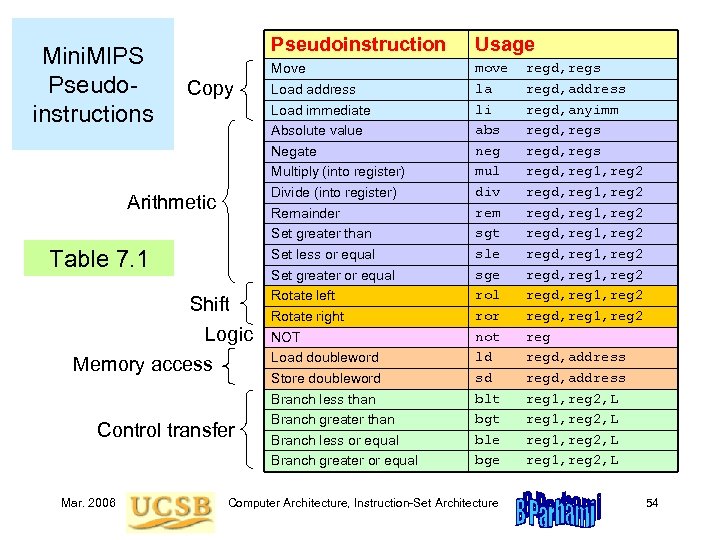

Mini. MIPS Pseudoinstructions Pseudoinstruction Copy Arithmetic Table 7. 1 Shift Logic Memory access Control transfer Mar. 2006 Usage Move Load address Load immediate Absolute value Negate Multiply (into register) Divide (into register) Remainder Set greater than Set less or equal Set greater or equal Rotate left Rotate right NOT Load doubleword Store doubleword Branch less than Branch greater than Branch less or equal Branch greater or equal move la li abs neg mul div rem sgt sle sge rol ror not ld sd blt bgt ble bge Computer Architecture, Instruction-Set Architecture regd, regs regd, address regd, anyimm regd, regs regd, reg 1, reg 2 regd, reg 1, reg 2 regd, address reg 1, reg 2, L reg 1, reg 2, L 54

Mini. MIPS Pseudoinstructions Pseudoinstruction Copy Arithmetic Table 7. 1 Shift Logic Memory access Control transfer Mar. 2006 Usage Move Load address Load immediate Absolute value Negate Multiply (into register) Divide (into register) Remainder Set greater than Set less or equal Set greater or equal Rotate left Rotate right NOT Load doubleword Store doubleword Branch less than Branch greater than Branch less or equal Branch greater or equal move la li abs neg mul div rem sgt sle sge rol ror not ld sd blt bgt ble bge Computer Architecture, Instruction-Set Architecture regd, regs regd, address regd, anyimm regd, regs regd, reg 1, reg 2 regd, reg 1, reg 2 regd, address reg 1, reg 2, L reg 1, reg 2, L 54

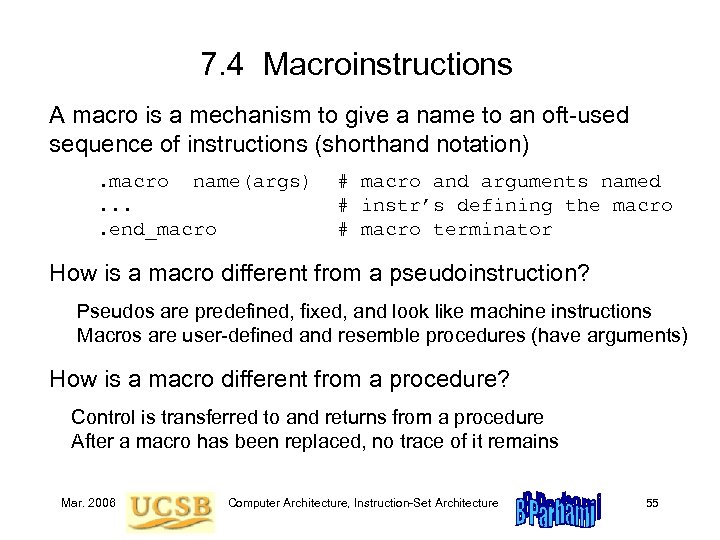

7. 4 Macroinstructions A macro is a mechanism to give a name to an oft-used sequence of instructions (shorthand notation) . macro name(args). . end_macro # macro and arguments named # instr’s defining the macro # macro terminator How is a macro different from a pseudoinstruction? Pseudos are predefined, fixed, and look like machine instructions Macros are user-defined and resemble procedures (have arguments) How is a macro different from a procedure? Control is transferred to and returns from a procedure After a macro has been replaced, no trace of it remains Mar. 2006 Computer Architecture, Instruction-Set Architecture 55

7. 4 Macroinstructions A macro is a mechanism to give a name to an oft-used sequence of instructions (shorthand notation) . macro name(args). . end_macro # macro and arguments named # instr’s defining the macro # macro terminator How is a macro different from a pseudoinstruction? Pseudos are predefined, fixed, and look like machine instructions Macros are user-defined and resemble procedures (have arguments) How is a macro different from a procedure? Control is transferred to and returns from a procedure After a macro has been replaced, no trace of it remains Mar. 2006 Computer Architecture, Instruction-Set Architecture 55

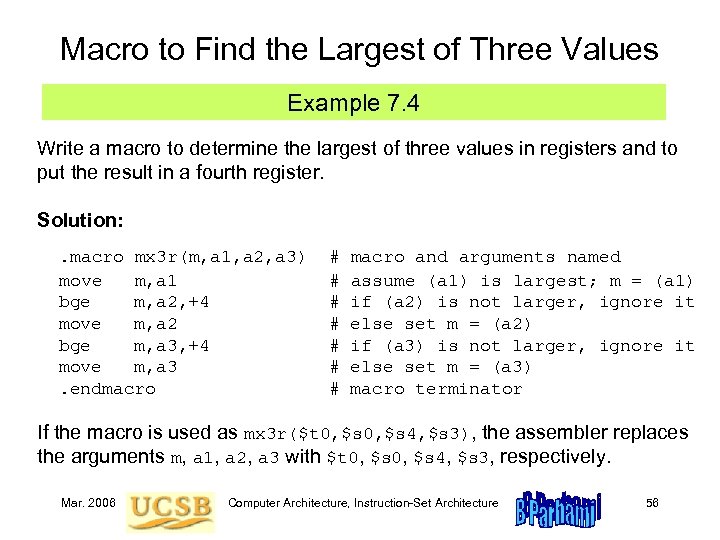

Macro to Find the Largest of Three Values Example 7. 4 Write a macro to determine the largest of three values in registers and to put the result in a fourth register. Solution: . macro mx 3 r(m, a 1, a 2, a 3) move m, a 1 bge m, a 2, +4 move m, a 2 bge m, a 3, +4 move m, a 3. endmacro # # # # macro and arguments named assume (a 1) is largest; m = (a 1) if (a 2) is not larger, ignore it else set m = (a 2) if (a 3) is not larger, ignore it else set m = (a 3) macro terminator If the macro is used as mx 3 r($t 0, $s 4, $s 3), the assembler replaces the arguments m, a 1, a 2, a 3 with $t 0, $s 4, $s 3, respectively. Mar. 2006 Computer Architecture, Instruction-Set Architecture 56

Macro to Find the Largest of Three Values Example 7. 4 Write a macro to determine the largest of three values in registers and to put the result in a fourth register. Solution: . macro mx 3 r(m, a 1, a 2, a 3) move m, a 1 bge m, a 2, +4 move m, a 2 bge m, a 3, +4 move m, a 3. endmacro # # # # macro and arguments named assume (a 1) is largest; m = (a 1) if (a 2) is not larger, ignore it else set m = (a 2) if (a 3) is not larger, ignore it else set m = (a 3) macro terminator If the macro is used as mx 3 r($t 0, $s 4, $s 3), the assembler replaces the arguments m, a 1, a 2, a 3 with $t 0, $s 4, $s 3, respectively. Mar. 2006 Computer Architecture, Instruction-Set Architecture 56

7. 5 Linking and Loading The linker has the following responsibilities: Ensuring correct interpretation (resolution) of labels in all modules Determining the placement of text and data segments in memory Evaluating all data addresses and instruction labels Forming an executable program with no unresolved references The loader is in charge of the following: Determining the memory needs of the program from its header Copying text and data from the executable program file into memory Modifying (shifting) addresses, where needed, during copying Placing program parameters onto the stack (as in a procedure call) Initializing all machine registers, including the stack pointer Jumping to a start-up routine that calls the program’s main routine Mar. 2006 Computer Architecture, Instruction-Set Architecture 57

7. 5 Linking and Loading The linker has the following responsibilities: Ensuring correct interpretation (resolution) of labels in all modules Determining the placement of text and data segments in memory Evaluating all data addresses and instruction labels Forming an executable program with no unresolved references The loader is in charge of the following: Determining the memory needs of the program from its header Copying text and data from the executable program file into memory Modifying (shifting) addresses, where needed, during copying Placing program parameters onto the stack (as in a procedure call) Initializing all machine registers, including the stack pointer Jumping to a start-up routine that calls the program’s main routine Mar. 2006 Computer Architecture, Instruction-Set Architecture 57

7. 6 Running Assembler Programs Spim is a simulator that can run Mini. MIPS programs The name Spim comes from reversing MIPS Three versions of Spim are available for free downloading: PCSpim for Windows machines xspim for X-windows spim for Unix systems You can download SPIM by visiting: http: //www. cs. wisc. edu/~larus/spim. html Mar. 2006 Computer Architecture, Instruction-Set Architecture 58

7. 6 Running Assembler Programs Spim is a simulator that can run Mini. MIPS programs The name Spim comes from reversing MIPS Three versions of Spim are available for free downloading: PCSpim for Windows machines xspim for X-windows spim for Unix systems You can download SPIM by visiting: http: //www. cs. wisc. edu/~larus/spim. html Mar. 2006 Computer Architecture, Instruction-Set Architecture 58

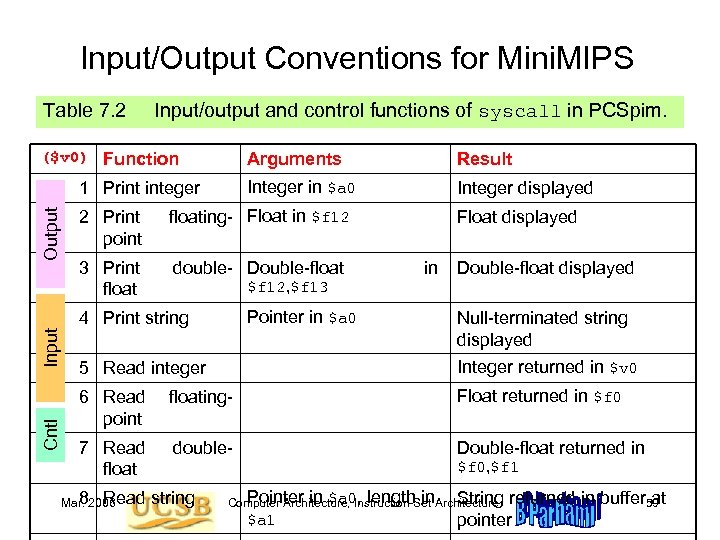

Input/Output Conventions for Mini. MIPS Table 7. 2 Input/output and control functions of syscall in PCSpim. ($v 0) Function Arguments Integer in $a 0 Output 1 Print integer Input Integer displayed 2 Print point floating- Float in $f 12 3 Print float double- Double-float Float displayed in Double-float displayed $f 12, $f 13 Pointer in $a 0 4 Print string Cntl Result Null-terminated string displayed 5 Read integer Integer returned in $v 0 6 Read floatingpoint Float returned in $f 0 7 Read float Double-float returned in double- 8 Read string Mar. 2006 $f 0, $f 1 Pointer in $a 0, length in String returned in buffer at Computer Architecture, Instruction-Set Architecture 59 $a 1 pointer

Input/Output Conventions for Mini. MIPS Table 7. 2 Input/output and control functions of syscall in PCSpim. ($v 0) Function Arguments Integer in $a 0 Output 1 Print integer Input Integer displayed 2 Print point floating- Float in $f 12 3 Print float double- Double-float Float displayed in Double-float displayed $f 12, $f 13 Pointer in $a 0 4 Print string Cntl Result Null-terminated string displayed 5 Read integer Integer returned in $v 0 6 Read floatingpoint Float returned in $f 0 7 Read float Double-float returned in double- 8 Read string Mar. 2006 $f 0, $f 1 Pointer in $a 0, length in String returned in buffer at Computer Architecture, Instruction-Set Architecture 59 $a 1 pointer

PCSpim User Interface Figure 7. 3 Mar. 2006 Computer Architecture, Instruction-Set Architecture 60

PCSpim User Interface Figure 7. 3 Mar. 2006 Computer Architecture, Instruction-Set Architecture 60

8 Instruction Set Variations The Mini. MIPS instruction set is only one example • How instruction sets may differ from that of Mini. MIPS • RISC and CISC instruction set design philosophies Topics in This Chapter 8. 1 Complex Instructions 8. 2 Alternative Addressing Modes 8. 3 Variations in Instruction Formats 8. 4 Instruction Set Design and Evolution 8. 5 The RISC/CISC Dichotomy 8. 6 Where to Draw the Line Mar. 2006 Computer Architecture, Instruction-Set Architecture 61

8 Instruction Set Variations The Mini. MIPS instruction set is only one example • How instruction sets may differ from that of Mini. MIPS • RISC and CISC instruction set design philosophies Topics in This Chapter 8. 1 Complex Instructions 8. 2 Alternative Addressing Modes 8. 3 Variations in Instruction Formats 8. 4 Instruction Set Design and Evolution 8. 5 The RISC/CISC Dichotomy 8. 6 Where to Draw the Line Mar. 2006 Computer Architecture, Instruction-Set Architecture 61

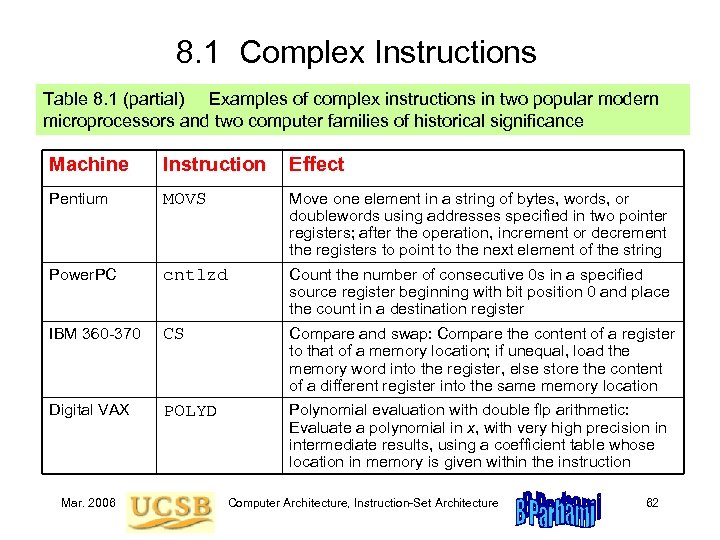

8. 1 Complex Instructions Table 8. 1 (partial) Examples of complex instructions in two popular modern microprocessors and two computer families of historical significance Machine Instruction Effect Pentium MOVS Move one element in a string of bytes, words, or doublewords using addresses specified in two pointer registers; after the operation, increment or decrement the registers to point to the next element of the string Power. PC cntlzd Count the number of consecutive 0 s in a specified source register beginning with bit position 0 and place the count in a destination register IBM 360 -370 CS Compare and swap: Compare the content of a register to that of a memory location; if unequal, load the memory word into the register, else store the content of a different register into the same memory location Digital VAX POLYD Polynomial evaluation with double flp arithmetic: Evaluate a polynomial in x, with very high precision in intermediate results, using a coefficient table whose location in memory is given within the instruction Mar. 2006 Computer Architecture, Instruction-Set Architecture 62

8. 1 Complex Instructions Table 8. 1 (partial) Examples of complex instructions in two popular modern microprocessors and two computer families of historical significance Machine Instruction Effect Pentium MOVS Move one element in a string of bytes, words, or doublewords using addresses specified in two pointer registers; after the operation, increment or decrement the registers to point to the next element of the string Power. PC cntlzd Count the number of consecutive 0 s in a specified source register beginning with bit position 0 and place the count in a destination register IBM 360 -370 CS Compare and swap: Compare the content of a register to that of a memory location; if unequal, load the memory word into the register, else store the content of a different register into the same memory location Digital VAX POLYD Polynomial evaluation with double flp arithmetic: Evaluate a polynomial in x, with very high precision in intermediate results, using a coefficient table whose location in memory is given within the instruction Mar. 2006 Computer Architecture, Instruction-Set Architecture 62

8. 2 Alternative Addressing Modes Let’s refresh our memory (from Chap. 5) Figure 5. 11 Schematic representation of addressing modes in Mini. MIPS. Mar. 2006 Computer Architecture, Instruction-Set Architecture 63

8. 2 Alternative Addressing Modes Let’s refresh our memory (from Chap. 5) Figure 5. 11 Schematic representation of addressing modes in Mini. MIPS. Mar. 2006 Computer Architecture, Instruction-Set Architecture 63

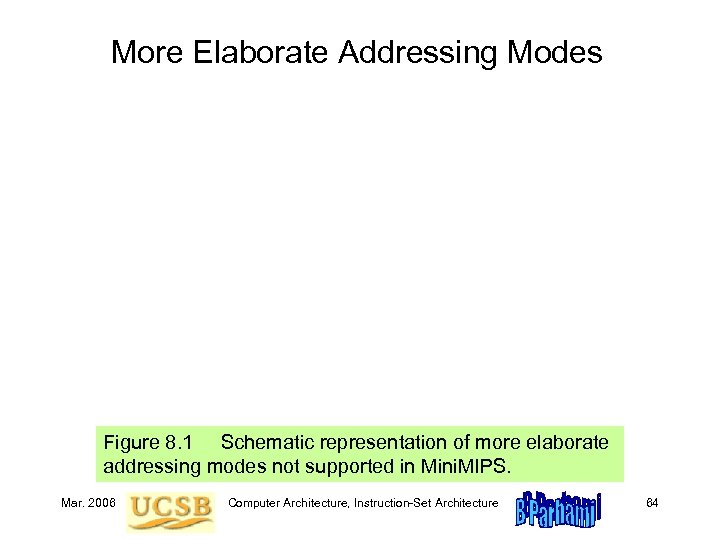

More Elaborate Addressing Modes Figure 8. 1 Schematic representation of more elaborate addressing modes not supported in Mini. MIPS. Mar. 2006 Computer Architecture, Instruction-Set Architecture 64

More Elaborate Addressing Modes Figure 8. 1 Schematic representation of more elaborate addressing modes not supported in Mini. MIPS. Mar. 2006 Computer Architecture, Instruction-Set Architecture 64

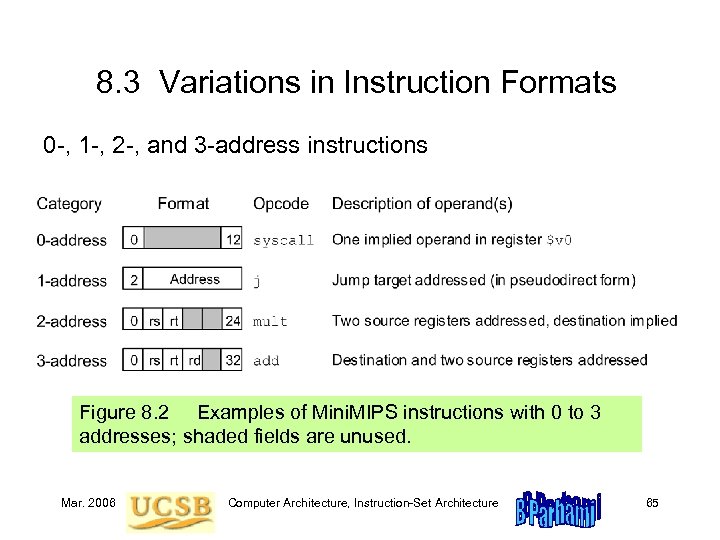

8. 3 Variations in Instruction Formats 0 -, 1 -, 2 -, and 3 -address instructions Figure 8. 2 Examples of Mini. MIPS instructions with 0 to 3 addresses; shaded fields are unused. Mar. 2006 Computer Architecture, Instruction-Set Architecture 65

8. 3 Variations in Instruction Formats 0 -, 1 -, 2 -, and 3 -address instructions Figure 8. 2 Examples of Mini. MIPS instructions with 0 to 3 addresses; shaded fields are unused. Mar. 2006 Computer Architecture, Instruction-Set Architecture 65

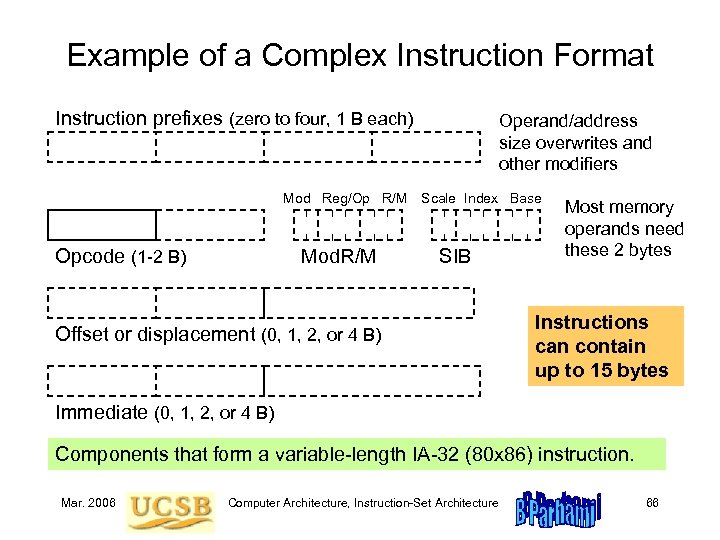

Example of a Complex Instruction Format Instruction prefixes (zero to four, 1 B each) Operand/address size overwrites and other modifiers Mod Reg/Op R/M Scale Index Base Opcode (1 -2 B) Mod. R/M SIB Offset or displacement (0, 1, 2, or 4 B) Most memory operands need these 2 bytes Instructions can contain up to 15 bytes Immediate (0, 1, 2, or 4 B) Components that form a variable-length IA-32 (80 x 86) instruction. Mar. 2006 Computer Architecture, Instruction-Set Architecture 66

Example of a Complex Instruction Format Instruction prefixes (zero to four, 1 B each) Operand/address size overwrites and other modifiers Mod Reg/Op R/M Scale Index Base Opcode (1 -2 B) Mod. R/M SIB Offset or displacement (0, 1, 2, or 4 B) Most memory operands need these 2 bytes Instructions can contain up to 15 bytes Immediate (0, 1, 2, or 4 B) Components that form a variable-length IA-32 (80 x 86) instruction. Mar. 2006 Computer Architecture, Instruction-Set Architecture 66

Some of IA-32’s Variable-Width Instructions Figure 8. 3 Example 80 x 86 instructions ranging in width from 1 to 6 bytes; much wider instructions (up to 15 bytes) also exist Mar. 2006 Computer Architecture, Instruction-Set Architecture 67

Some of IA-32’s Variable-Width Instructions Figure 8. 3 Example 80 x 86 instructions ranging in width from 1 to 6 bytes; much wider instructions (up to 15 bytes) also exist Mar. 2006 Computer Architecture, Instruction-Set Architecture 67

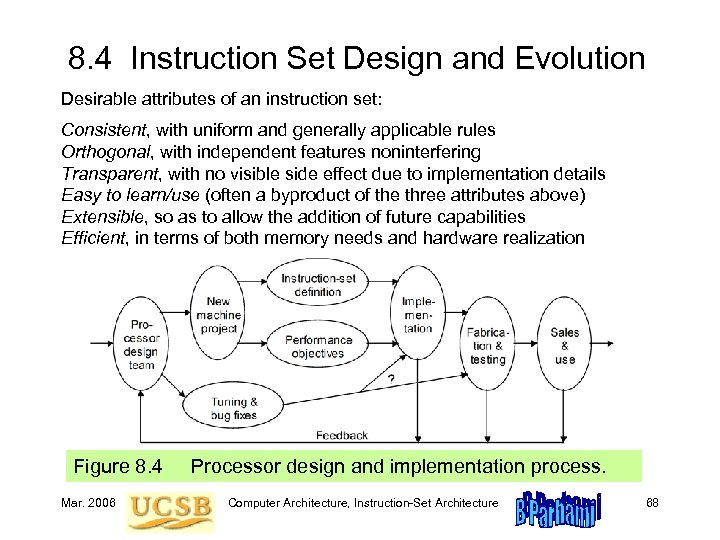

8. 4 Instruction Set Design and Evolution Desirable attributes of an instruction set: Consistent, with uniform and generally applicable rules Orthogonal, with independent features noninterfering Transparent, with no visible side effect due to implementation details Easy to learn/use (often a byproduct of the three attributes above) Extensible, so as to allow the addition of future capabilities Efficient, in terms of both memory needs and hardware realization Figure 8. 4 Processor design and implementation process. Mar. 2006 Computer Architecture, Instruction-Set Architecture 68

8. 4 Instruction Set Design and Evolution Desirable attributes of an instruction set: Consistent, with uniform and generally applicable rules Orthogonal, with independent features noninterfering Transparent, with no visible side effect due to implementation details Easy to learn/use (often a byproduct of the three attributes above) Extensible, so as to allow the addition of future capabilities Efficient, in terms of both memory needs and hardware realization Figure 8. 4 Processor design and implementation process. Mar. 2006 Computer Architecture, Instruction-Set Architecture 68

8. 5 The RISC/CISC Dichotomy The RISC (reduced instruction set computer) philosophy: Complex instruction sets are undesirable because inclusion of mechanisms to interpret all the possible combinations of opcodes and operands might slow down even very simple operations. Ad hoc extension of instruction sets, while maintaining backward compatibility, leads to CISC; imagine modern English containing every English word that has been used through the ages Features of RISC architecture 1. 2. 3. 4. Small set of inst’s, each executable in roughly the same time Load/store architecture (leading to more registers) Limited addressing mode to simplify address calculations Simple, uniform instruction formats (ease of decoding) Mar. 2006 Computer Architecture, Instruction-Set Architecture 69

8. 5 The RISC/CISC Dichotomy The RISC (reduced instruction set computer) philosophy: Complex instruction sets are undesirable because inclusion of mechanisms to interpret all the possible combinations of opcodes and operands might slow down even very simple operations. Ad hoc extension of instruction sets, while maintaining backward compatibility, leads to CISC; imagine modern English containing every English word that has been used through the ages Features of RISC architecture 1. 2. 3. 4. Small set of inst’s, each executable in roughly the same time Load/store architecture (leading to more registers) Limited addressing mode to simplify address calculations Simple, uniform instruction formats (ease of decoding) Mar. 2006 Computer Architecture, Instruction-Set Architecture 69

RISC/CISC Comparison via Generalized Amdahl’s Law Example 8. 1 An ISA has two classes of simple (S) and complex (C) instructions. On a reference implementation of the ISA, class-S instructions account for 95% of the running time for programs of interest. A RISC version of the machine is being considered that executes only class-S instructions directly in hardware, with class-C instructions treated as pseudoinstructions. It is estimated that in the RISC version, class-S instructions will run 20% faster while class-C instructions will be slowed down by a factor of 3. Does the RISC approach offer better or worse performance compared to the reference implementation? Solution Per assumptions, 0. 95 of the work is speeded up by a factor of 1. 0 / 0. 8 = 1. 25, while the remaining 5% is slowed down by a factor of 3. The RISC speed-up is 1 / [0. 95 / 1. 25 + 0. 05 3] = 1. 1. Thus, a 10% improvement in performance can be expected in the RISC version. Mar. 2006 Computer Architecture, Instruction-Set Architecture 70

RISC/CISC Comparison via Generalized Amdahl’s Law Example 8. 1 An ISA has two classes of simple (S) and complex (C) instructions. On a reference implementation of the ISA, class-S instructions account for 95% of the running time for programs of interest. A RISC version of the machine is being considered that executes only class-S instructions directly in hardware, with class-C instructions treated as pseudoinstructions. It is estimated that in the RISC version, class-S instructions will run 20% faster while class-C instructions will be slowed down by a factor of 3. Does the RISC approach offer better or worse performance compared to the reference implementation? Solution Per assumptions, 0. 95 of the work is speeded up by a factor of 1. 0 / 0. 8 = 1. 25, while the remaining 5% is slowed down by a factor of 3. The RISC speed-up is 1 / [0. 95 / 1. 25 + 0. 05 3] = 1. 1. Thus, a 10% improvement in performance can be expected in the RISC version. Mar. 2006 Computer Architecture, Instruction-Set Architecture 70

8. 6 Where to Draw the Line The ultimate reduced instruction set computer (URISC): How many instructions are absolutely needed for useful computation? Only one! subtract source 1 from source 2, replace source 2 with the result, and jump to target address if result is negative Assembly language form: label: urisc dest, src 1, target Pseudoinstructions can be synthesized using the single instruction: stop: . word start: urisc Corrected urisc version. . . Mar. 2006 0 dest, +1 temp, src, +1 dest, temp, +1 # # # dest temp dest rest This is the move pseudoinstruction = 0 = -(src) = -(temp); i. e. (src) of program Computer Architecture, Instruction-Set Architecture 71

8. 6 Where to Draw the Line The ultimate reduced instruction set computer (URISC): How many instructions are absolutely needed for useful computation? Only one! subtract source 1 from source 2, replace source 2 with the result, and jump to target address if result is negative Assembly language form: label: urisc dest, src 1, target Pseudoinstructions can be synthesized using the single instruction: stop: . word start: urisc Corrected urisc version. . . Mar. 2006 0 dest, +1 temp, src, +1 dest, temp, +1 # # # dest temp dest rest This is the move pseudoinstruction = 0 = -(src) = -(temp); i. e. (src) of program Computer Architecture, Instruction-Set Architecture 71

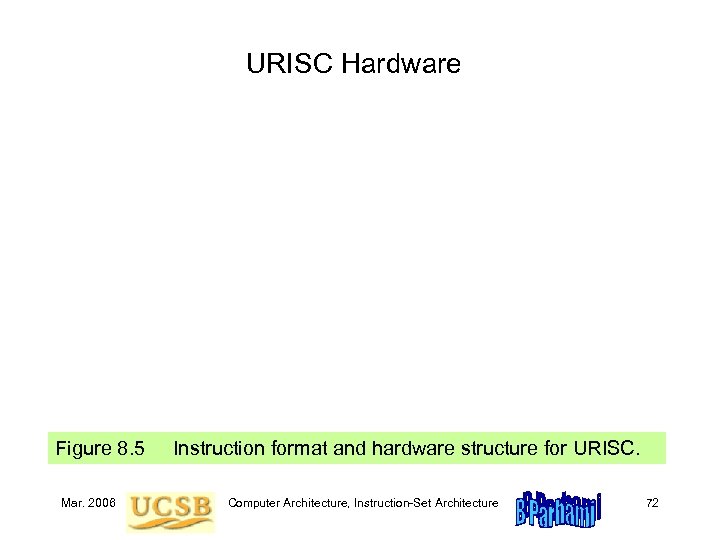

URISC Hardware Figure 8. 5 Instruction format and hardware structure for URISC. Mar. 2006 Computer Architecture, Instruction-Set Architecture 72

URISC Hardware Figure 8. 5 Instruction format and hardware structure for URISC. Mar. 2006 Computer Architecture, Instruction-Set Architecture 72

Hardware for Floating-Point Addition Figure 12. 5 Simplified schematic of a floating-point adder. Mar. 2006 Computer Architecture, Instruction-Set Architecture 73

Hardware for Floating-Point Addition Figure 12. 5 Simplified schematic of a floating-point adder. Mar. 2006 Computer Architecture, Instruction-Set Architecture 73

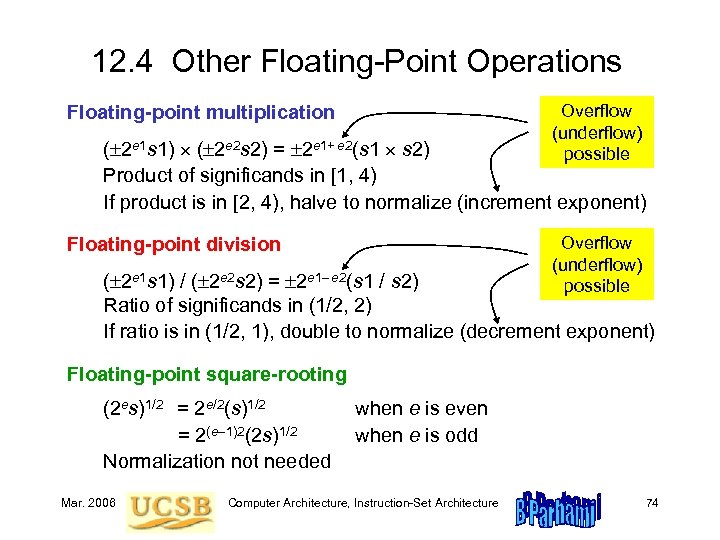

12. 4 Other Floating-Point Operations Overflow (underflow) possible Floating-point multiplication ( 2 e 1 s 1) ( 2 e 2 s 2) = 2 e 1+ e 2(s 1 s 2) Product of significands in [1, 4) If product is in [2, 4), halve to normalize (increment exponent) Overflow (underflow) possible Floating-point division ( 2 e 1 s 1) / ( 2 e 2 s 2) = 2 e 1– e 2(s 1 / s 2) Ratio of significands in (1/2, 2) If ratio is in (1/2, 1), double to normalize (decrement exponent) Floating-point square-rooting (2 es)1/2 = 2 e/2(s)1/2 = 2(e– 1)2(2 s)1/2 Normalization not needed Mar. 2006 when e is even when e is odd Computer Architecture, Instruction-Set Architecture 74

12. 4 Other Floating-Point Operations Overflow (underflow) possible Floating-point multiplication ( 2 e 1 s 1) ( 2 e 2 s 2) = 2 e 1+ e 2(s 1 s 2) Product of significands in [1, 4) If product is in [2, 4), halve to normalize (increment exponent) Overflow (underflow) possible Floating-point division ( 2 e 1 s 1) / ( 2 e 2 s 2) = 2 e 1– e 2(s 1 / s 2) Ratio of significands in (1/2, 2) If ratio is in (1/2, 1), double to normalize (decrement exponent) Floating-point square-rooting (2 es)1/2 = 2 e/2(s)1/2 = 2(e– 1)2(2 s)1/2 Normalization not needed Mar. 2006 when e is even when e is odd Computer Architecture, Instruction-Set Architecture 74

Hardware for Floating-Point Multiplication and Division Figure 12. 6 Simplified schematic of a floatingpoint multiply/divide unit. Mar. 2006 Computer Architecture, Instruction-Set Architecture 75

Hardware for Floating-Point Multiplication and Division Figure 12. 6 Simplified schematic of a floatingpoint multiply/divide unit. Mar. 2006 Computer Architecture, Instruction-Set Architecture 75

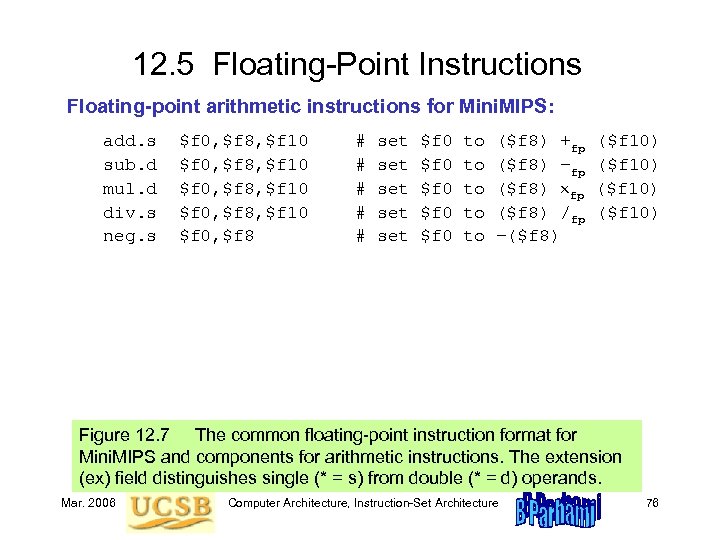

12. 5 Floating-Point Instructions Floating-point arithmetic instructions for Mini. MIPS: add. s sub. d mul. d div. s neg. s $f 0, $f 8, $f 10 $f 0, $f 8 # # # set set set $f 0 $f 0 to to to ($f 8) +fp ($f 8) –fp ($f 8) /fp –($f 8) ($f 10) Figure 12. 7 The common floating-point instruction format for Mini. MIPS and components for arithmetic instructions. The extension (ex) field distinguishes single (* = s) from double (* = d) operands. Mar. 2006 Computer Architecture, Instruction-Set Architecture 76

12. 5 Floating-Point Instructions Floating-point arithmetic instructions for Mini. MIPS: add. s sub. d mul. d div. s neg. s $f 0, $f 8, $f 10 $f 0, $f 8 # # # set set set $f 0 $f 0 to to to ($f 8) +fp ($f 8) –fp ($f 8) /fp –($f 8) ($f 10) Figure 12. 7 The common floating-point instruction format for Mini. MIPS and components for arithmetic instructions. The extension (ex) field distinguishes single (* = s) from double (* = d) operands. Mar. 2006 Computer Architecture, Instruction-Set Architecture 76

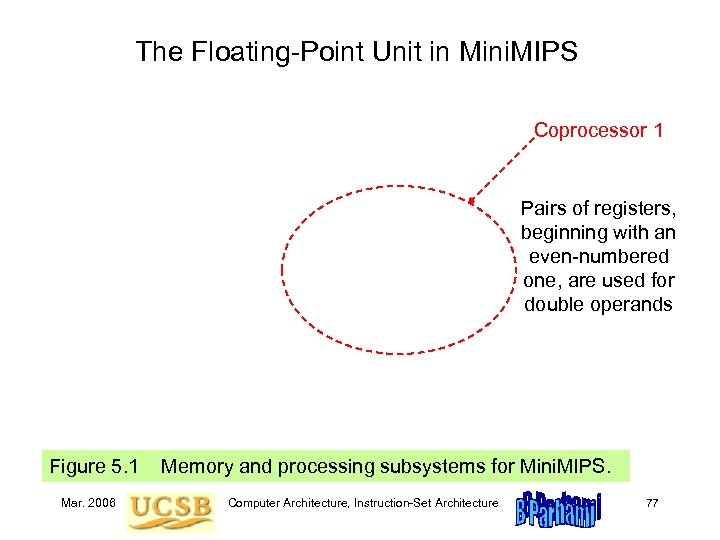

The Floating-Point Unit in Mini. MIPS Coprocessor 1 Pairs of registers, beginning with an even-numbered one, are used for double operands Figure 5. 1 Memory and processing subsystems for Mini. MIPS. Mar. 2006 Computer Architecture, Instruction-Set Architecture 77

The Floating-Point Unit in Mini. MIPS Coprocessor 1 Pairs of registers, beginning with an even-numbered one, are used for double operands Figure 5. 1 Memory and processing subsystems for Mini. MIPS. Mar. 2006 Computer Architecture, Instruction-Set Architecture 77

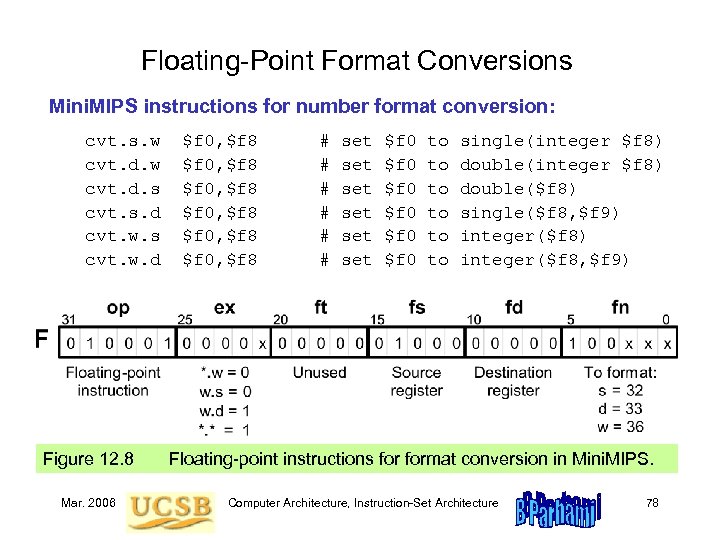

Floating-Point Format Conversions Mini. MIPS instructions for number format conversion: cvt. s. w cvt. d. s cvt. s. d cvt. w. s cvt. w. d $f 0, $f 8 $f 0, $f 8 # # # set set set $f 0 $f 0 to to to single(integer $f 8) double($f 8) single($f 8, $f 9) integer($f 8, $f 9) Figure 12. 8 Floating-point instructions format conversion in Mini. MIPS. Mar. 2006 Computer Architecture, Instruction-Set Architecture 78

Floating-Point Format Conversions Mini. MIPS instructions for number format conversion: cvt. s. w cvt. d. s cvt. s. d cvt. w. s cvt. w. d $f 0, $f 8 $f 0, $f 8 # # # set set set $f 0 $f 0 to to to single(integer $f 8) double($f 8) single($f 8, $f 9) integer($f 8, $f 9) Figure 12. 8 Floating-point instructions format conversion in Mini. MIPS. Mar. 2006 Computer Architecture, Instruction-Set Architecture 78

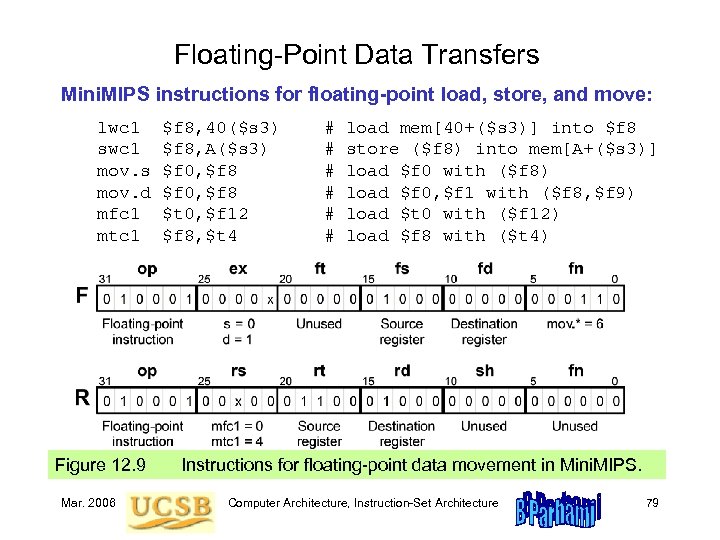

Floating-Point Data Transfers Mini. MIPS instructions for floating-point load, store, and move: lwc 1 swc 1 mov. s mov. d mfc 1 mtc 1 $f 8, 40($s 3) $f 8, A($s 3) $f 0, $f 8 $t 0, $f 12 $f 8, $t 4 # # # load mem[40+($s 3)] into $f 8 store ($f 8) into mem[A+($s 3)] load $f 0 with ($f 8) load $f 0, $f 1 with ($f 8, $f 9) load $t 0 with ($f 12) load $f 8 with ($t 4) Figure 12. 9 Instructions for floating-point data movement in Mini. MIPS. Mar. 2006 Computer Architecture, Instruction-Set Architecture 79

Floating-Point Data Transfers Mini. MIPS instructions for floating-point load, store, and move: lwc 1 swc 1 mov. s mov. d mfc 1 mtc 1 $f 8, 40($s 3) $f 8, A($s 3) $f 0, $f 8 $t 0, $f 12 $f 8, $t 4 # # # load mem[40+($s 3)] into $f 8 store ($f 8) into mem[A+($s 3)] load $f 0 with ($f 8) load $f 0, $f 1 with ($f 8, $f 9) load $t 0 with ($f 12) load $f 8 with ($t 4) Figure 12. 9 Instructions for floating-point data movement in Mini. MIPS. Mar. 2006 Computer Architecture, Instruction-Set Architecture 79

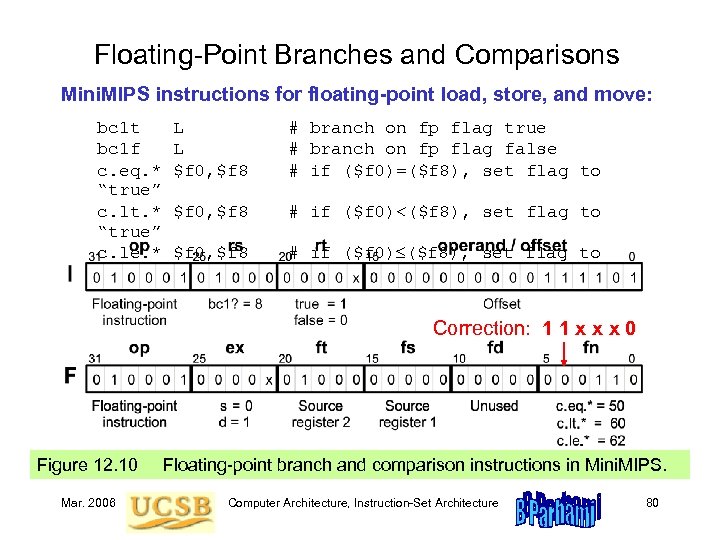

Floating-Point Branches and Comparisons Mini. MIPS instructions for floating-point load, store, and move: bc 1 t bc 1 f c. eq. * “true” c. lt. * “true” c. le. * “true” L L $f 0, $f 8 # branch on fp flag true # branch on fp flag false # if ($f 0)=($f 8), set flag to $f 0, $f 8 # if ($f 0)<($f 8), set flag to $f 0, $f 8 # if ($f 0) ($f 8), set flag to Correction: 1 1 x x x 0 Figure 12. 10 Floating-point branch and comparison instructions in Mini. MIPS. Mar. 2006 Computer Architecture, Instruction-Set Architecture 80

Floating-Point Branches and Comparisons Mini. MIPS instructions for floating-point load, store, and move: bc 1 t bc 1 f c. eq. * “true” c. lt. * “true” c. le. * “true” L L $f 0, $f 8 # branch on fp flag true # branch on fp flag false # if ($f 0)=($f 8), set flag to $f 0, $f 8 # if ($f 0)<($f 8), set flag to $f 0, $f 8 # if ($f 0) ($f 8), set flag to Correction: 1 1 x x x 0 Figure 12. 10 Floating-point branch and comparison instructions in Mini. MIPS. Mar. 2006 Computer Architecture, Instruction-Set Architecture 80

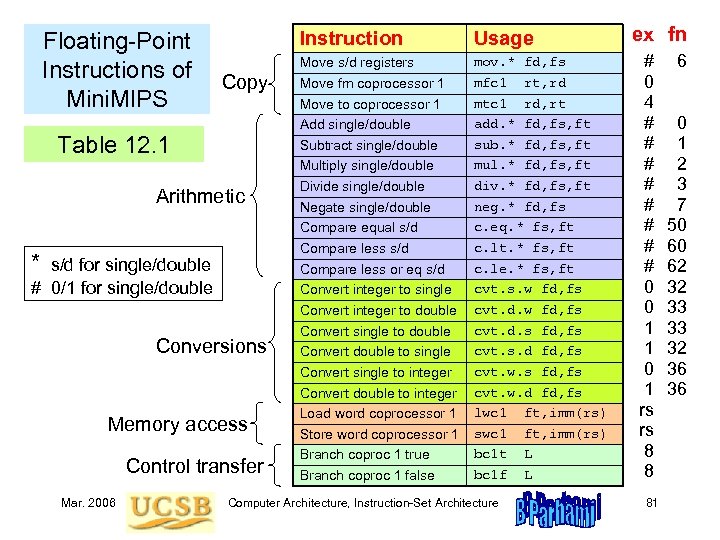

Floating-Point Instructions of Copy Mini. MIPS Table 12. 1 Arithmetic * s/d for single/double # 0/1 for single/double Conversions Memory access Control transfer Mar. 2006 Instruction Usage Move s/d registers Move fm coprocessor 1 Move to coprocessor 1 Add single/double Subtract single/double Multiply single/double Divide single/double Negate single/double Compare equal s/d Compare less or eq s/d Convert integer to single Convert integer to double Convert single to double Convert double to single Convert single to integer Convert double to integer Load word coprocessor 1 Store word coprocessor 1 Branch coproc 1 true Branch coproc 1 false mov. * fd, fs mfc 1 rt, rd mtc 1 rd, rt add. * fd, fs, ft sub. * fd, fs, ft mul. * fd, fs, ft div. * fd, fs, ft neg. * fd, fs c. eq. * fs, ft c. lt. * fs, ft c. le. * fs, ft cvt. s. w fd, fs cvt. d. s fd, fs cvt. s. d fd, fs cvt. w. s fd, fs cvt. w. d fd, fs lwc 1 ft, imm(rs) swc 1 ft, imm(rs) bc 1 t L bc 1 f L Computer Architecture, Instruction-Set Architecture ex fn # 0 4 # # # # 0 0 1 1 0 1 rs rs 8 8 81 6 0 1 2 3 7 50 60 62 32 33 33 32 36 36

Floating-Point Instructions of Copy Mini. MIPS Table 12. 1 Arithmetic * s/d for single/double # 0/1 for single/double Conversions Memory access Control transfer Mar. 2006 Instruction Usage Move s/d registers Move fm coprocessor 1 Move to coprocessor 1 Add single/double Subtract single/double Multiply single/double Divide single/double Negate single/double Compare equal s/d Compare less or eq s/d Convert integer to single Convert integer to double Convert single to double Convert double to single Convert single to integer Convert double to integer Load word coprocessor 1 Store word coprocessor 1 Branch coproc 1 true Branch coproc 1 false mov. * fd, fs mfc 1 rt, rd mtc 1 rd, rt add. * fd, fs, ft sub. * fd, fs, ft mul. * fd, fs, ft div. * fd, fs, ft neg. * fd, fs c. eq. * fs, ft c. lt. * fs, ft c. le. * fs, ft cvt. s. w fd, fs cvt. d. s fd, fs cvt. s. d fd, fs cvt. w. s fd, fs cvt. w. d fd, fs lwc 1 ft, imm(rs) swc 1 ft, imm(rs) bc 1 t L bc 1 f L Computer Architecture, Instruction-Set Architecture ex fn # 0 4 # # # # 0 0 1 1 0 1 rs rs 8 8 81 6 0 1 2 3 7 50 60 62 32 33 33 32 36 36

12. 6 Result Precision and Errors Example 12. 4 Laws of algebra may not hold in floating-point arithmetic. For example, the following computations show that the associative law of addition, (a + b) + c = a + (b + c), is violated for the three numbers shown. Mar. 2006 Computer Architecture, Instruction-Set Architecture 82

12. 6 Result Precision and Errors Example 12. 4 Laws of algebra may not hold in floating-point arithmetic. For example, the following computations show that the associative law of addition, (a + b) + c = a + (b + c), is violated for the three numbers shown. Mar. 2006 Computer Architecture, Instruction-Set Architecture 82

Error Control and Certifiable Arithmetic Catastrophic cancellation in subtracting almost equal numbers: Area of a needlelike triangle A = [s(s – a)(s – b)(s – c)]1/2 c b a Possible remedies Carry extra precision in intermediate results (guard digits): commonly used in calculators Use alternate formula that does not produce cancellation errors Certifiable arithmetic with intervals A number is represented by its lower and upper bounds [xl, xu] Example of arithmetic: [xl, xu] +interval [yl, yu] = [xl +fp yl, xu +fp yu] Mar. 2006 Computer Architecture, Instruction-Set Architecture 83

Error Control and Certifiable Arithmetic Catastrophic cancellation in subtracting almost equal numbers: Area of a needlelike triangle A = [s(s – a)(s – b)(s – c)]1/2 c b a Possible remedies Carry extra precision in intermediate results (guard digits): commonly used in calculators Use alternate formula that does not produce cancellation errors Certifiable arithmetic with intervals A number is represented by its lower and upper bounds [xl, xu] Example of arithmetic: [xl, xu] +interval [yl, yu] = [xl +fp yl, xu +fp yu] Mar. 2006 Computer Architecture, Instruction-Set Architecture 83

Evaluation of Elementary Functions Approximating polynomials ln x = 2(z + z 3/3 + z 5/5 + z 7/7 +. . . ) where z = (x – 1)/(x + 1) ex = 1 + x/1! + x 2/2! + x 3/3! + x 4/4! +. . . cos x = 1 – x 2/2! + x 4/4! – x 6/6! + x 8/8! –. . . tan– 1 x = x – x 3/3 + x 5/5 – x 7/7 + x 9/9 –. . . Iterative (convergence) schemes For example, beginning with an estimate for x 1/2, the following iterative formula provides a more accurate estimate in each step q(i+1) = 0. 5(q(i) + x/q(i)) Table lookup (with interpolation) A pure table lookup scheme results in huge tables (impractical); hence, often a hybrid approach, involving interpolation, is used. Mar. 2006 Computer Architecture, Instruction-Set Architecture 84