d6e2bc29b15cc6b5c7cbed962b940d6b.ppt

- Количество слайдов: 83

Part 3: Regulatory ( «stabilizing» ) control Inventory (level) control structure – Location of throughput manipulator – Consistency and radiating rule Structure of regulatory control layer (PID) – Selection of controlled variables (CV 2) and pairing with manipulated variables (MV 2) – Main rule: Control drifting variables and "pair close" Summary: Sigurd’s rules for plantwide control 1

Outline • Skogestad procedure for control structure design I Top Down • Step S 1: Define operational objective (cost) and constraints • Step S 2: Identify degrees of freedom and optimize operation for disturbances • Step S 3: Implementation of optimal operation – What to control ? (primary CV’s) – Active constraints – Self-optimizing variables for unconstrained, c=Hy • Step S 4: Where set the production rate? (Inventory control) II Bottom Up • Step S 5: Regulatory control: What more to control (secondary CV’s) ? • Step S 6: Supervisory control • Step S 7: Real-time optimization 2

Step S 4. Where set production rate? • Very important decision that determines the structure of the rest of the inventory control system! • May also have important economic implications • Link between Top-down (economics) and Bottom-up (stabilization) parts – Inventory control is the most important part of stabilizing control • “Throughput manipulator” (TPM) = MV for controlling throughput (production rate, network flow) • Where set the production rate = Where locate the TPM? – Traditionally: At the feed – For maximum production (with small backoff): At the bottleneck 3

TPM and link to inventory control • Liquid inventory: Level control (LC) – Sometimes pressure control (PC) • • 5 Gas inventory: Pressure control (PC) Component inventory: Composition control (CC, XC, AC)

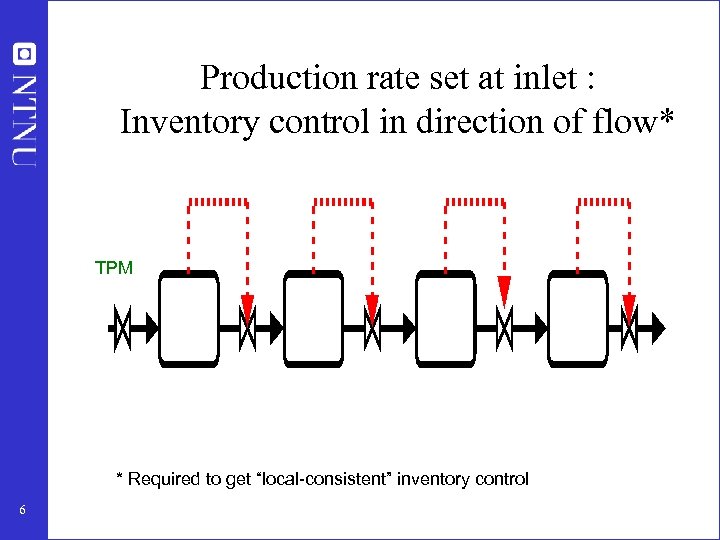

Production rate set at inlet : Inventory control in direction of flow* TPM * Required to get “local-consistent” inventory control 6

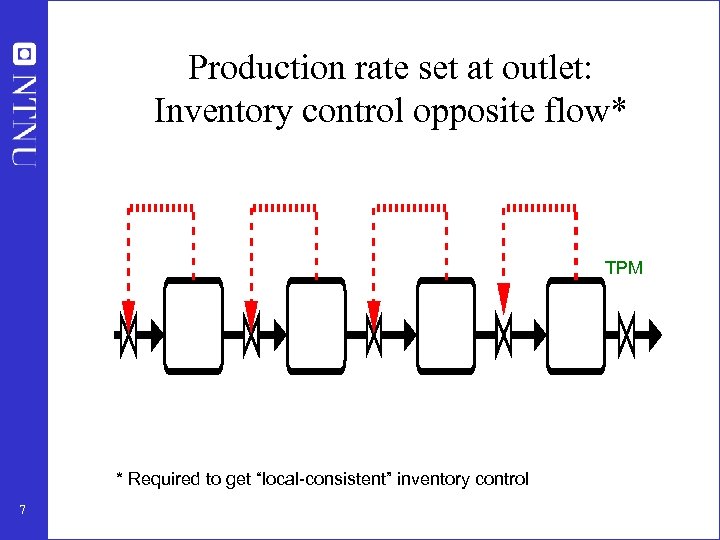

Production rate set at outlet: Inventory control opposite flow* TPM * Required to get “local-consistent” inventory control 7

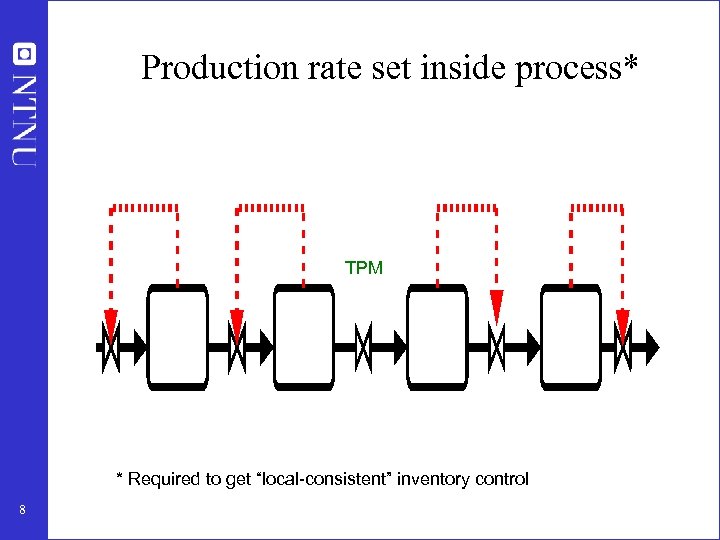

Production rate set inside process* TPM * Required to get “local-consistent” inventory control 8

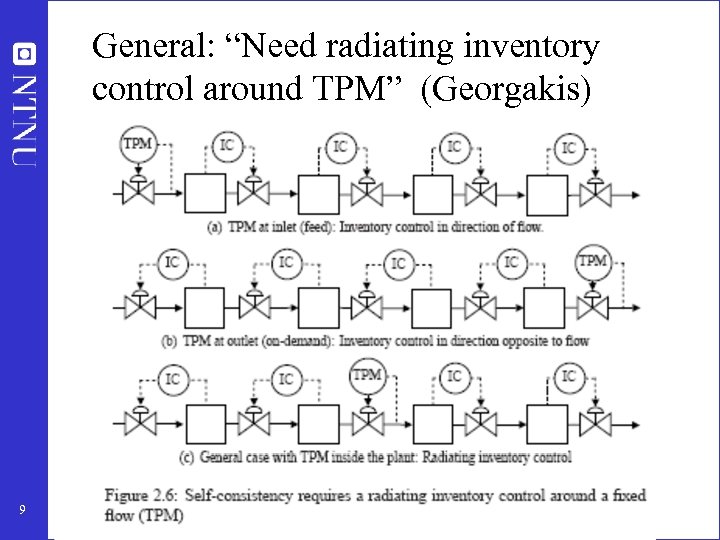

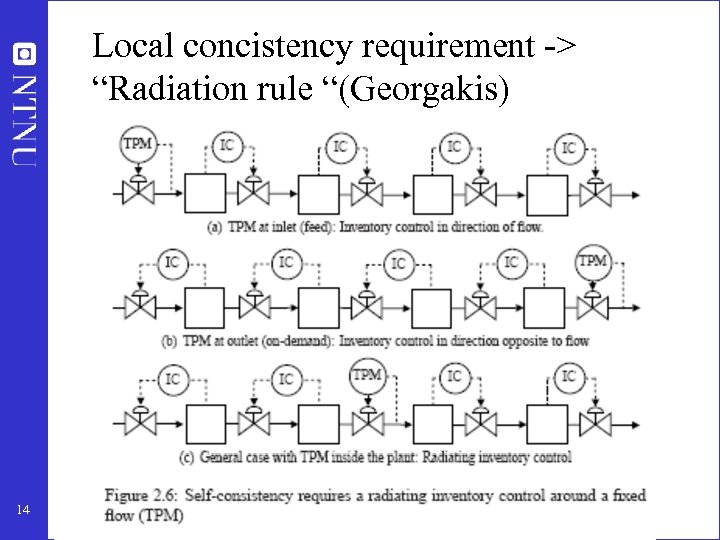

General: “Need radiating inventory control around TPM” (Georgakis) 9

Consistency of inventory control • Consistency (required property): An inventory control system is said to be consistent if the steadystate mass balances (total, components and phases) are satisfied for any part of the process, including the individual units and the overall plant. 10

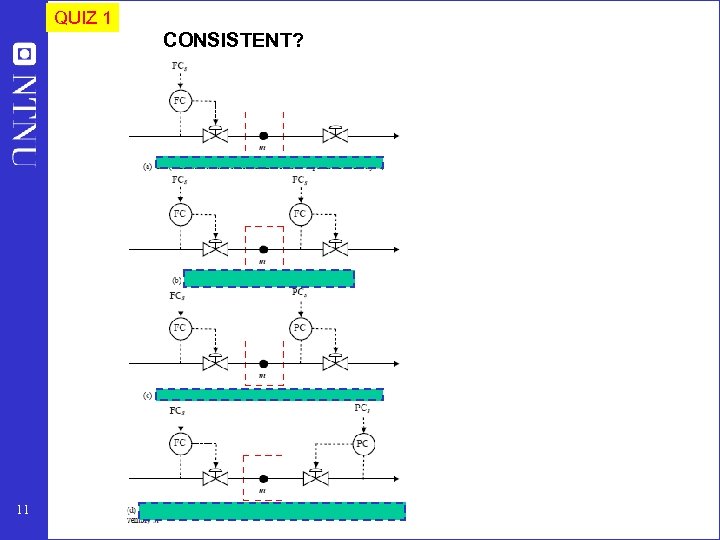

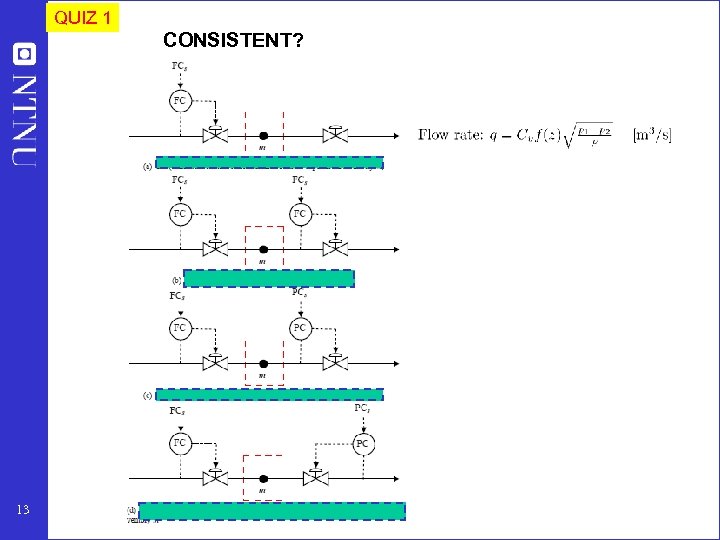

QUIZ 1 CONSISTENT? 11

Local-consistency rule Rule 1. Local-consistency requires that 1. The total inventory (mass) of any part of the process must be locally regulated by its in- or outflows , which implies that at least one flow in or out of any part of the process must depend on the inventory inside that part of the process. 2. For systems with several components, the inventory of each component of any part of the process must be locally regulated by its in- or outflows or by chemical reaction. 3. For systems with several phases, the inventory of each phase of any part of the process must be locally regulated by its in- or outflows or by phase transition. 12 Proof: Mass balances Note: Without the word “local” one gets the more general consistency rule

QUIZ 1 CONSISTENT? 13

Local concistency requirement -> “Radiation rule “(Georgakis) 14

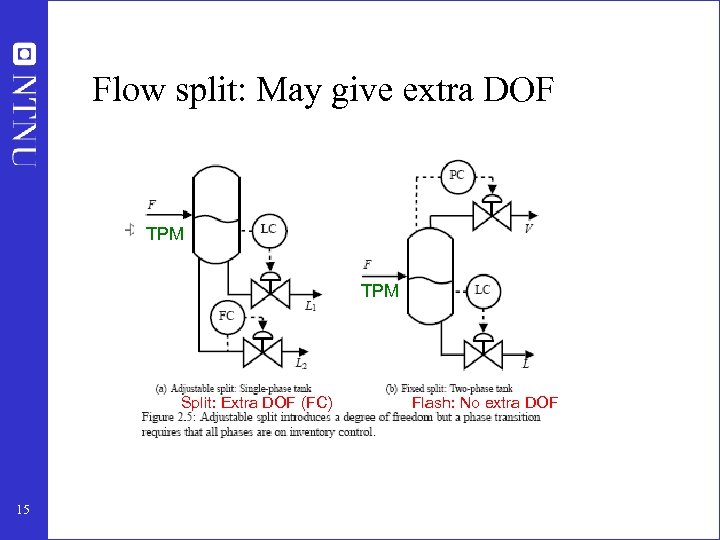

Flow split: May give extra DOF TPM Split: Extra DOF (FC) 15 Flash: No extra DOF

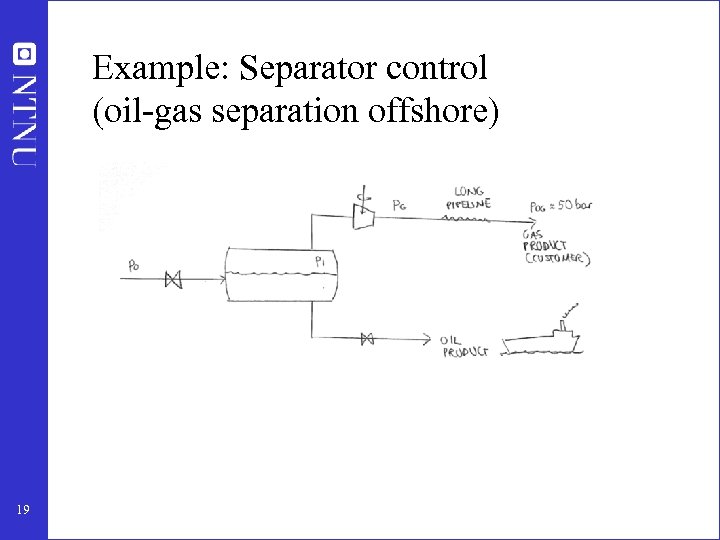

Example: Separator control (oil-gas separation offshore) 19

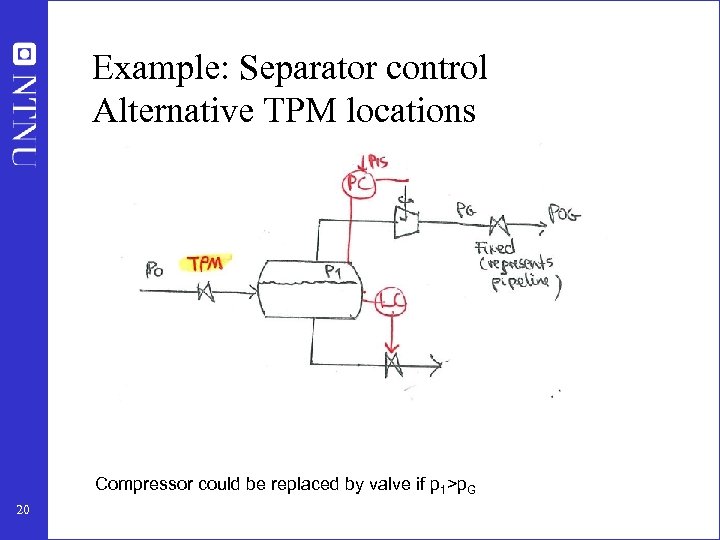

Example: Separator control Alternative TPM locations Compressor could be replaced by valve if p 1>p. G 20

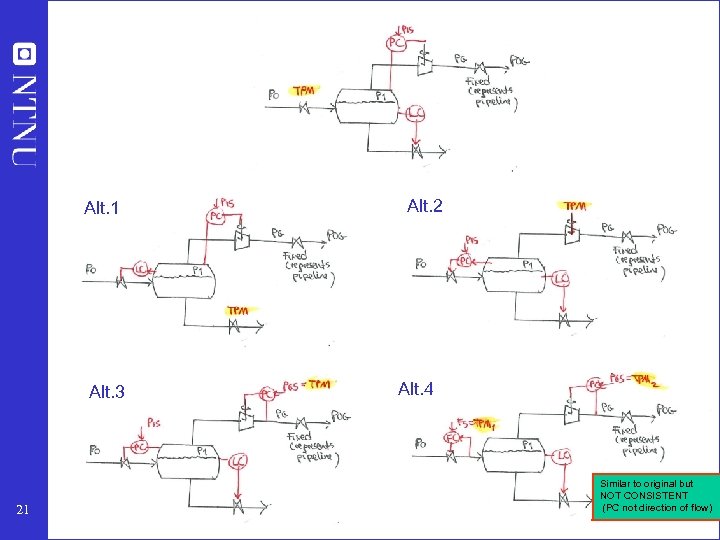

Alt. 1 Alt. 3 21 Alt. 2 Alt. 4 Similar to original but NOT CONSISTENT (PC not direction of flow)

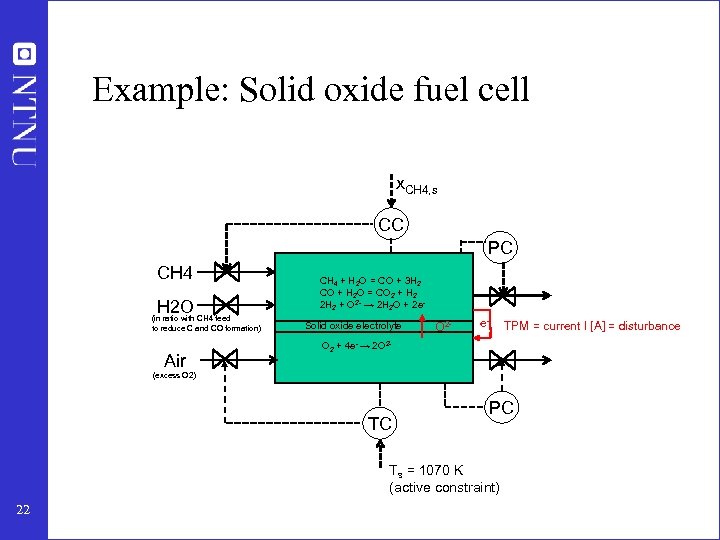

Example: Solid oxide fuel cell x. CH 4, s CC PC CH 4 H 2 O (in ratio with CH 4 feed to reduce C and CO formation) Air CH 4 + H 2 O = CO + 3 H 2 CO + H 2 O = CO 2 + H 2 2 H 2 + O 2 - → 2 H 2 O + 2 e. Solid oxide electrolyte O 2 - e- TPM = current I [A] = disturbance O 2 + 4 e- → 2 O 2 - (excess O 2) TC PC Ts = 1070 K (active constraint) 22

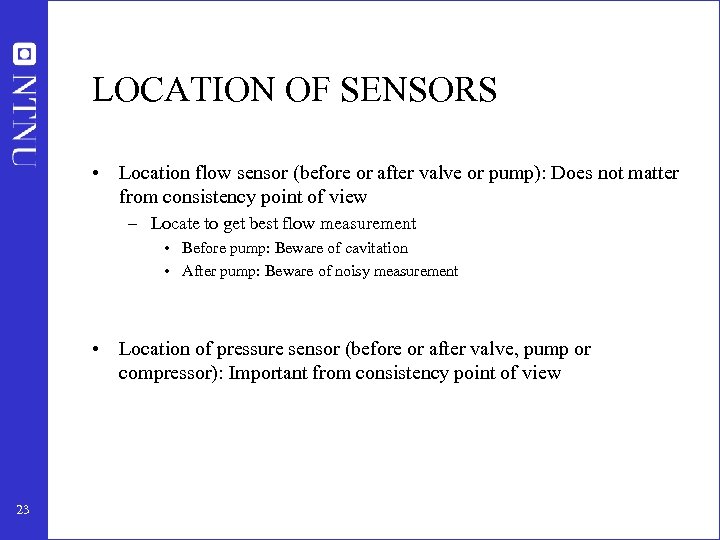

LOCATION OF SENSORS • Location flow sensor (before or after valve or pump): Does not matter from consistency point of view – Locate to get best flow measurement • Before pump: Beware of cavitation • After pump: Beware of noisy measurement • Location of pressure sensor (before or after valve, pump or compressor): Important from consistency point of view 23

Next slides: Exercises and solutions 24

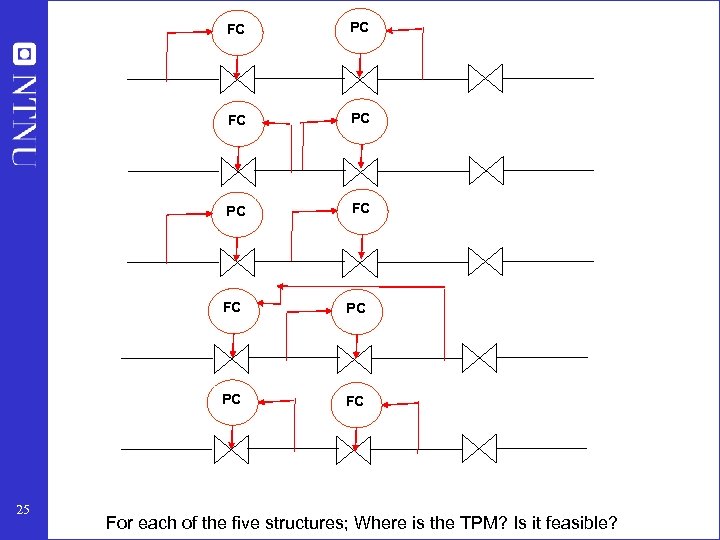

FC PC PC FC FC PC 25 PC FC For each of the five structures; Where is the TPM? Is it feasible?

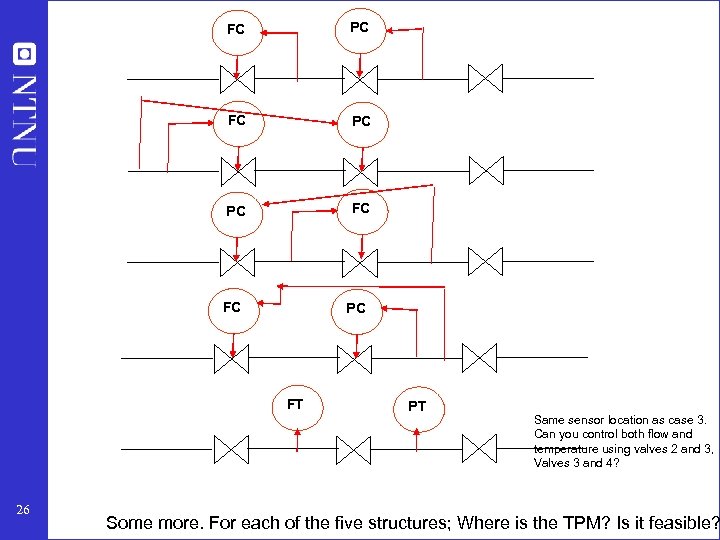

FC PC PC FC FC PC FT 26 PT Same sensor location as case 3. Can you control both flow and temperature using valves 2 and 3, Valves 3 and 4? Some more. For each of the five structures; Where is the TPM? Is it feasible?

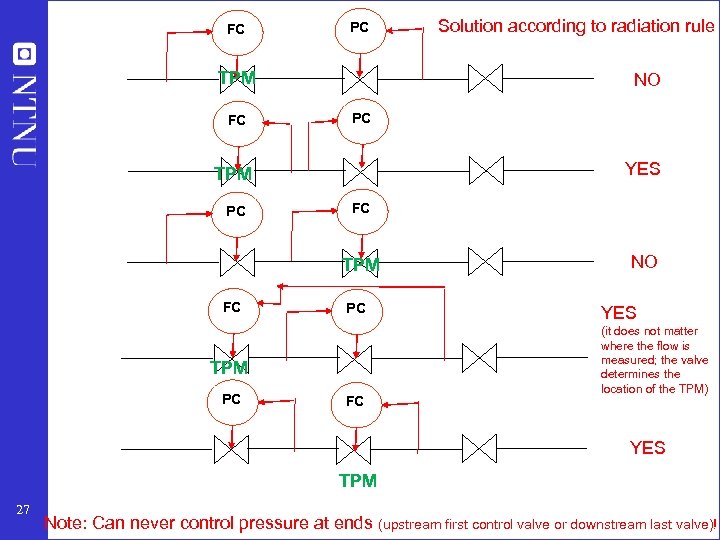

FC PC TPM FC NO PC YES TPM PC FC TPM FC PC TPM PC Solution according to radiation rule FC NO YES (it does not matter where the flow is measured; the valve determines the location of the TPM) YES TPM 27 Note: Can never control pressure at ends (upstream first control valve or downstream last valve)!

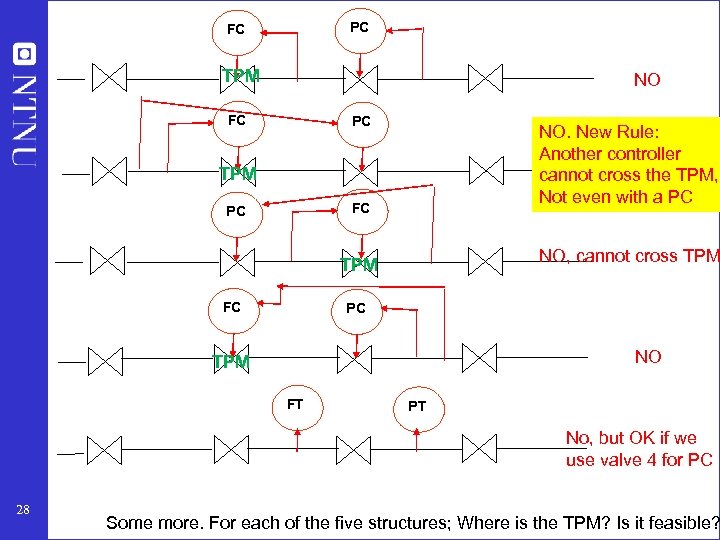

PC FC TPM NO FC PC NO. New Rule: Another controller cannot cross the TPM, Not even with a PC TPM FC PC NO, cannot cross TPM FC PC NO TPM FT PT No, but OK if we use valve 4 for PC 28 Some more. For each of the five structures; Where is the TPM? Is it feasible?

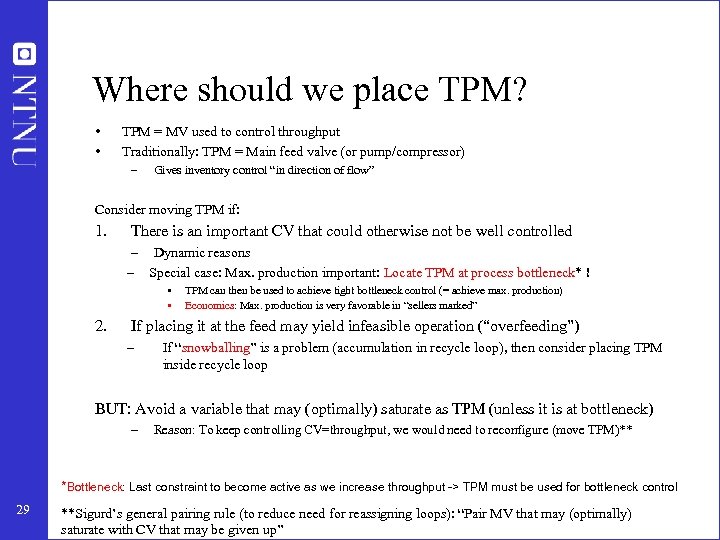

Where should we place TPM? • • TPM = MV used to control throughput Traditionally: TPM = Main feed valve (or pump/compressor) – Gives inventory control “in direction of flow” Consider moving TPM if: 1. There is an important CV that could otherwise not be well controlled – Dynamic reasons – Special case: Max. production important: Locate TPM at process bottleneck* ! • • 2. TPM can then be used to achieve tight bottleneck control (= achieve max. production) Economics: Max. production is very favorable in “sellers marked” If placing it at the feed may yield infeasible operation (“overfeeding”) – If “snowballing” is a problem (accumulation in recycle loop), then consider placing TPM inside recycle loop BUT: Avoid a variable that may (optimally) saturate as TPM (unless it is at bottleneck) – Reason: To keep controlling CV=throughput, we would need to reconfigure (move TPM)** *Bottleneck: Last constraint to become active as we increase throughput -> TPM must be used for bottleneck control 29 **Sigurd’s general pairing rule (to reduce need for reassigning loops): “Pair MV that may (optimally) saturate with CV that may be given up”

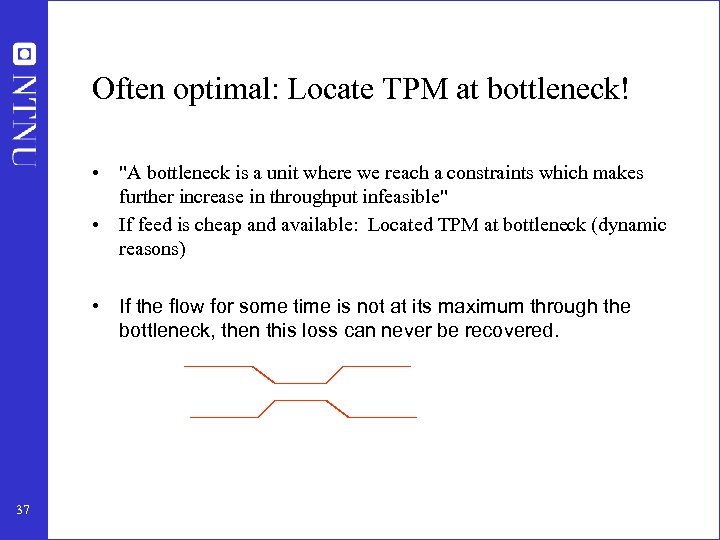

Often optimal: Locate TPM at bottleneck! • "A bottleneck is a unit where we reach a constraints which makes further increase in throughput infeasible" • If feed is cheap and available: Located TPM at bottleneck (dynamic reasons) • If the flow for some time is not at its maximum through the bottleneck, then this loss can never be recovered. 37

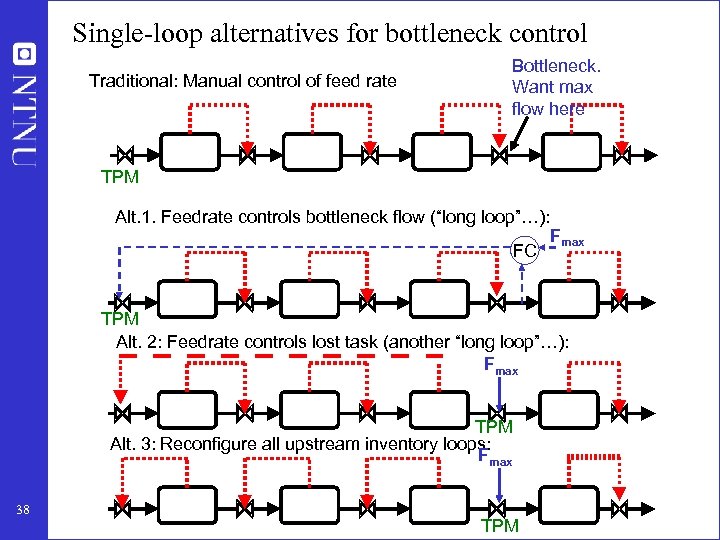

Single-loop alternatives for bottleneck control Traditional: Manual control of feed rate Bottleneck. Want max flow here TPM Alt. 1. Feedrate controls bottleneck flow (“long loop”…): FC Fmax TPM Alt. 2: Feedrate controls lost task (another “long loop”…): Fmax TPM Alt. 3: Reconfigure all upstream inventory loops: Fmax 38 TPM

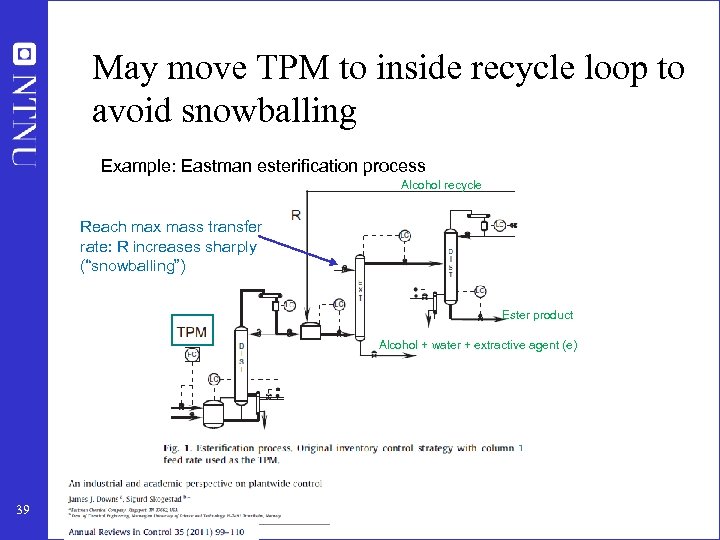

May move TPM to inside recycle loop to avoid snowballing Example: Eastman esterification process Alcohol recycle Reach max mass transfer rate: R increases sharply (“snowballing”) Ester product Alcohol + water + extractive agent (e) 39

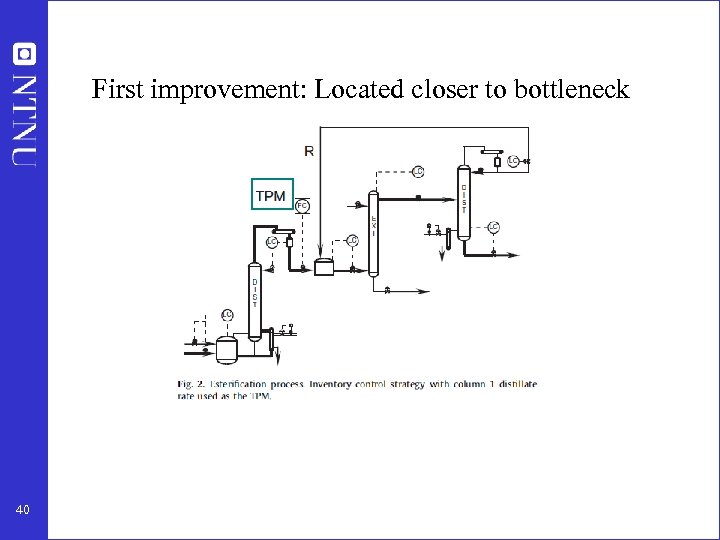

First improvement: Located closer to bottleneck 40

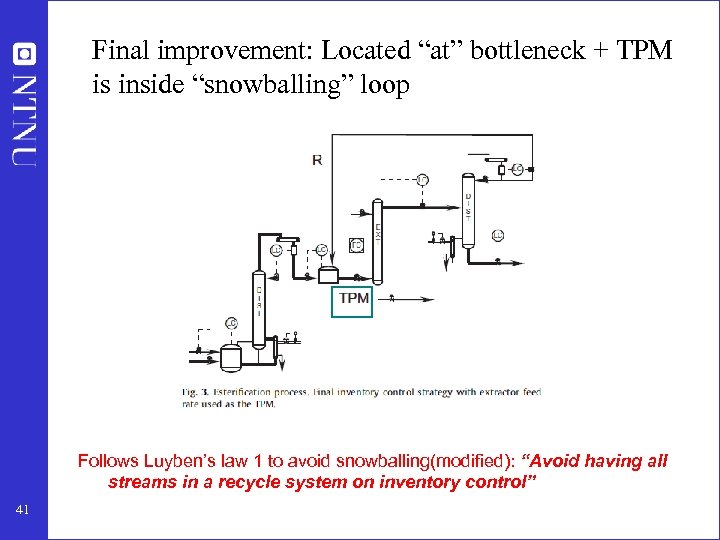

Final improvement: Located “at” bottleneck + TPM is inside “snowballing” loop Follows Luyben’s law 1 to avoid snowballing(modified): “Avoid having all streams in a recycle system on inventory control” 41

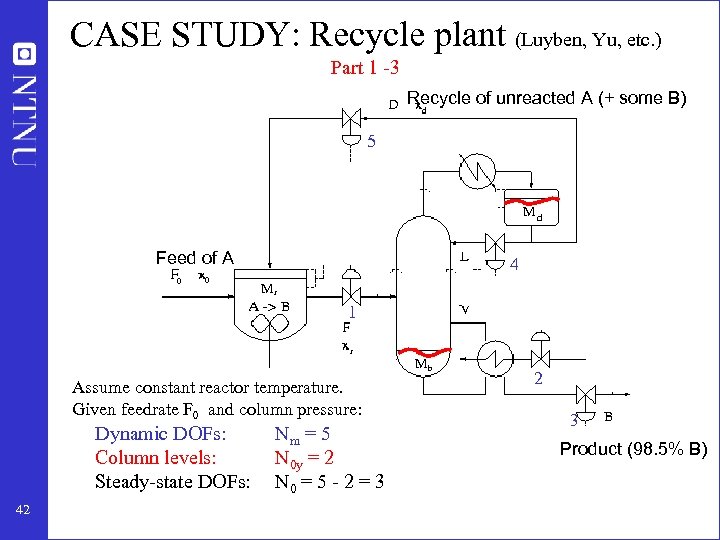

CASE STUDY: Recycle plant (Luyben, Yu, etc. ) Part 1 -3 Recycle of unreacted A (+ some B) 5 Feed of A 4 1 Assume constant reactor temperature. Given feedrate F 0 and column pressure: Dynamic DOFs: Column levels: Steady-state DOFs: 42 Nm = 5 N 0 y = 2 N 0 = 5 - 2 = 3 2 3 Product (98. 5% B)

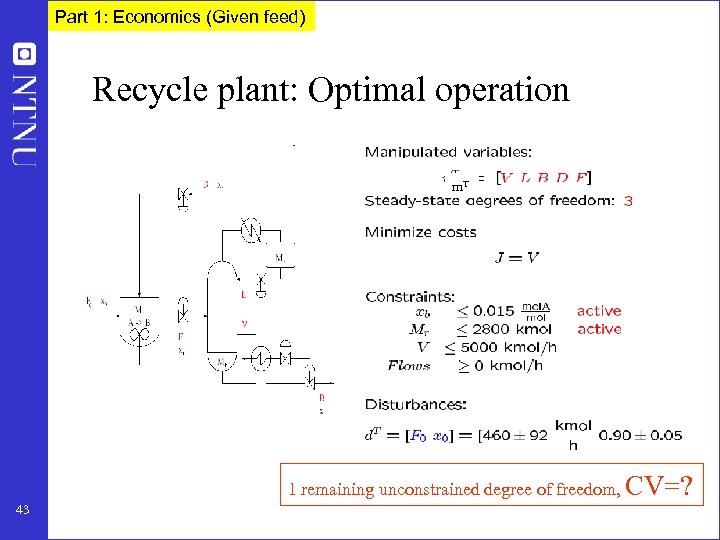

Part 1: Economics (Given feed) Recycle plant: Optimal operation m. T 1 remaining unconstrained degree of freedom, CV=? 43

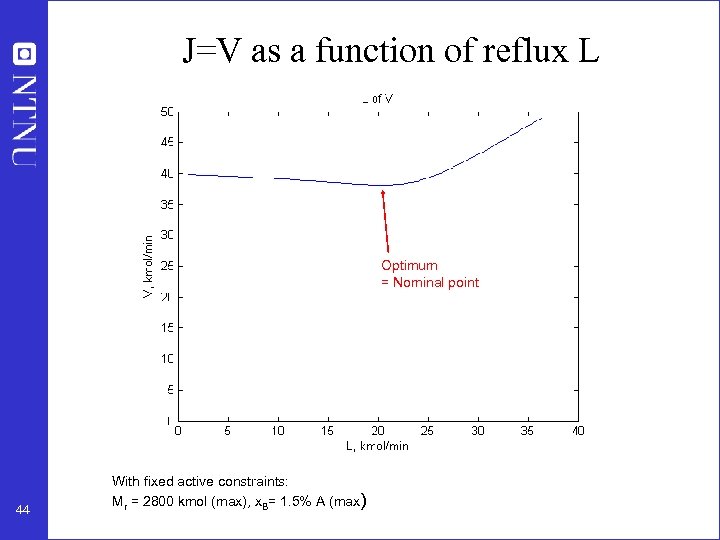

J=V as a function of reflux L Optimum = Nominal point 44 With fixed active constraints: Mr = 2800 kmol (max), x. B= 1. 5% A (max)

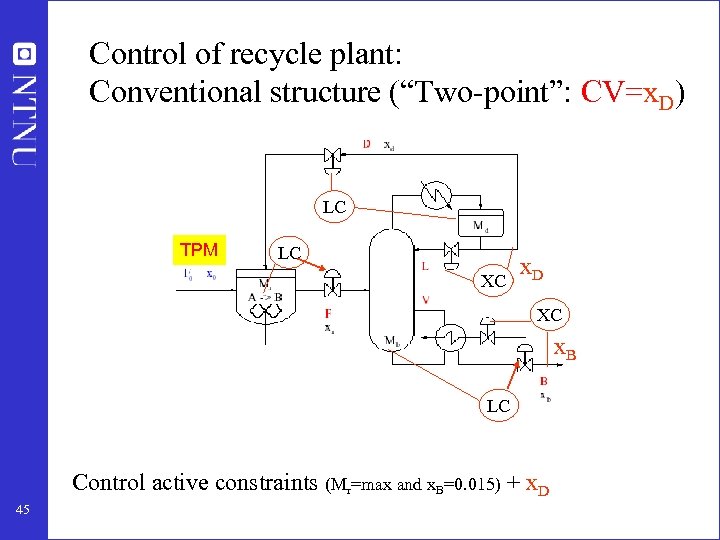

Control of recycle plant: Conventional structure (“Two-point”: CV=x. D) LC TPM LC XC x. D XC x. B LC Control active constraints (Mr=max and x. B=0. 015) + x. D 45

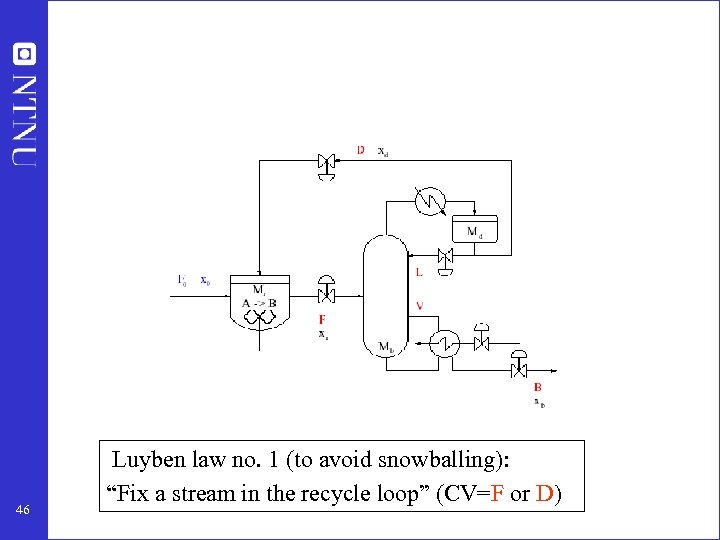

46 Luyben law no. 1 (to avoid snowballing): “Fix a stream in the recycle loop” (CV=F or D)

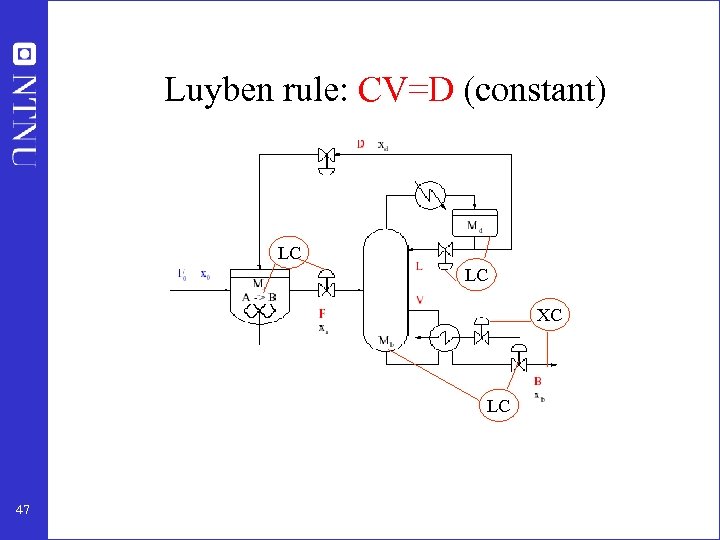

Luyben rule: CV=D (constant) LC LC XC LC 47

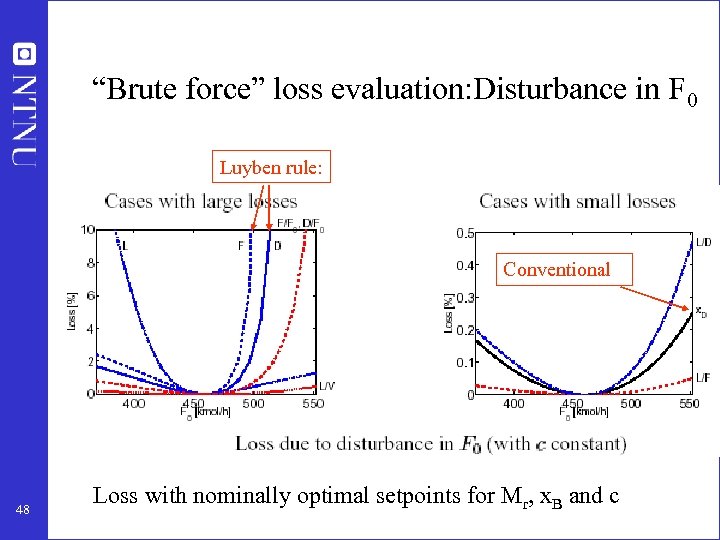

“Brute force” loss evaluation: Disturbance in F 0 Luyben rule: Conventional 48 Loss with nominally optimal setpoints for Mr, x. B and c

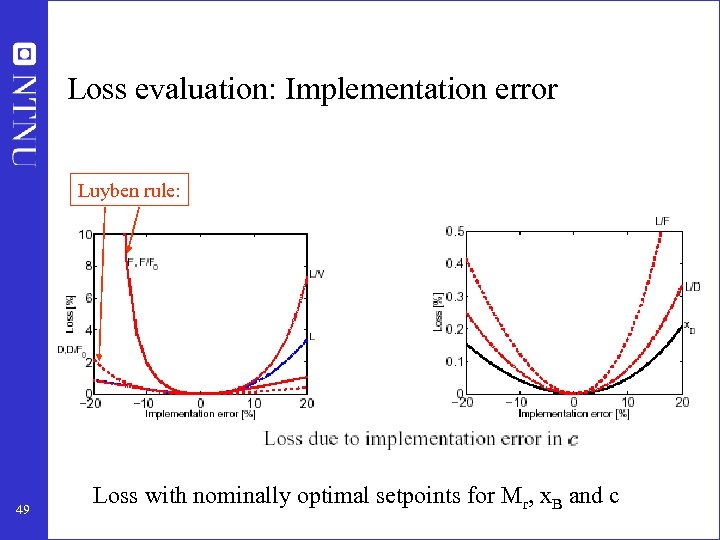

Loss evaluation: Implementation error Luyben rule: 49 Loss with nominally optimal setpoints for Mr, x. B and c

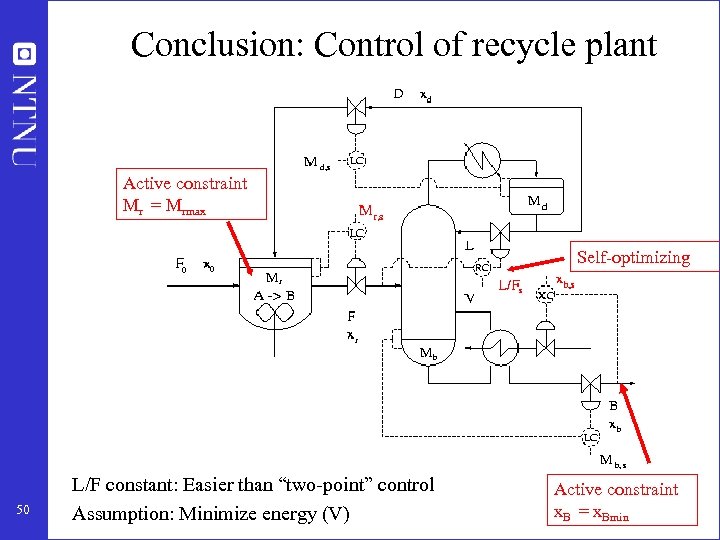

Conclusion: Control of recycle plant Active constraint Mr = Mrmax Self-optimizing 50 L/F constant: Easier than “two-point” control Assumption: Minimize energy (V) Active constraint x. B = x. Bmin

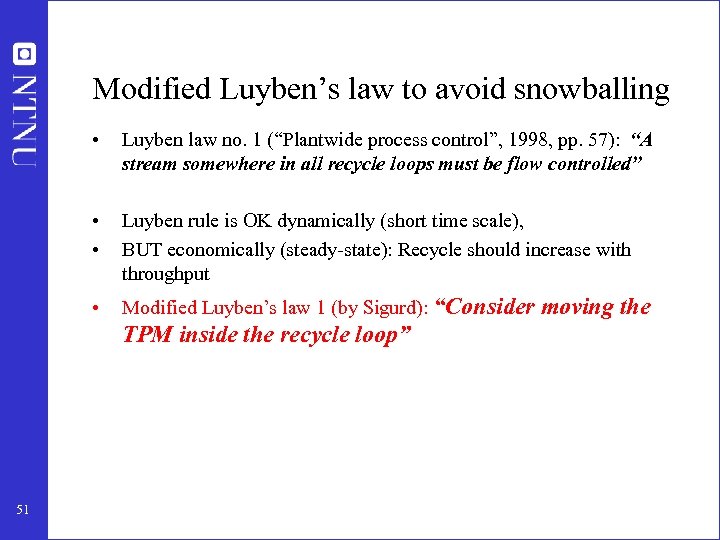

Modified Luyben’s law to avoid snowballing • Luyben law no. 1 (“Plantwide process control”, 1998, pp. 57): “A stream somewhere in all recycle loops must be flow controlled” • • Luyben rule is OK dynamically (short time scale), BUT economically (steady-state): Recycle should increase with throughput • Modified Luyben’s law 1 (by Sigurd): “Consider moving the TPM inside the recycle loop” 51

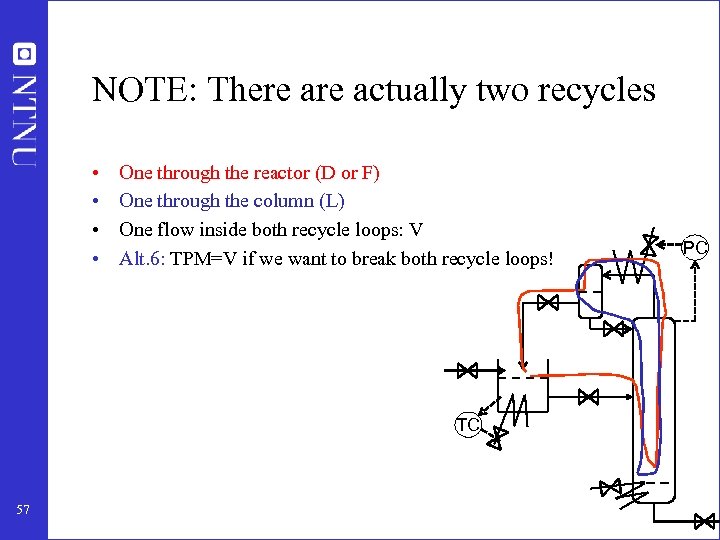

NOTE: There actually two recycles • • One through the reactor (D or F) One through the column (L) One flow inside both recycle loops: V Alt. 6: TPM=V if we want to break both recycle loops! PC TC 57

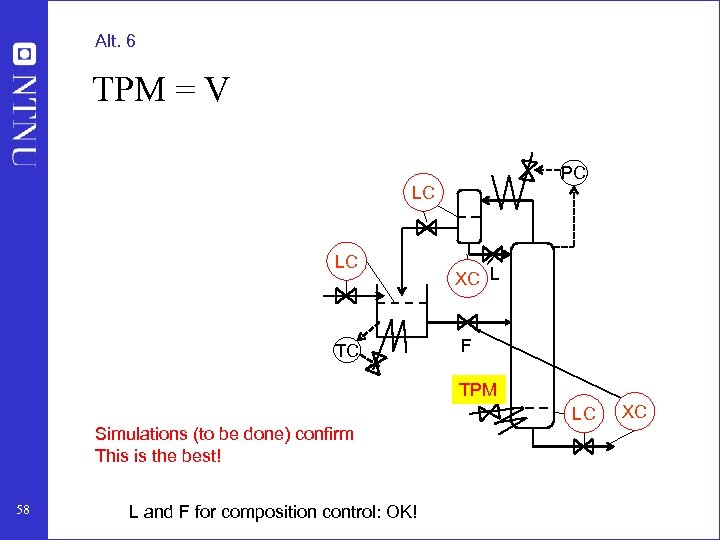

Alt. 6 TPM = V PC LC LC TC XC L F TPM Simulations (to be done) confirm This is the best! 58 L and F for composition control: OK! LC XC

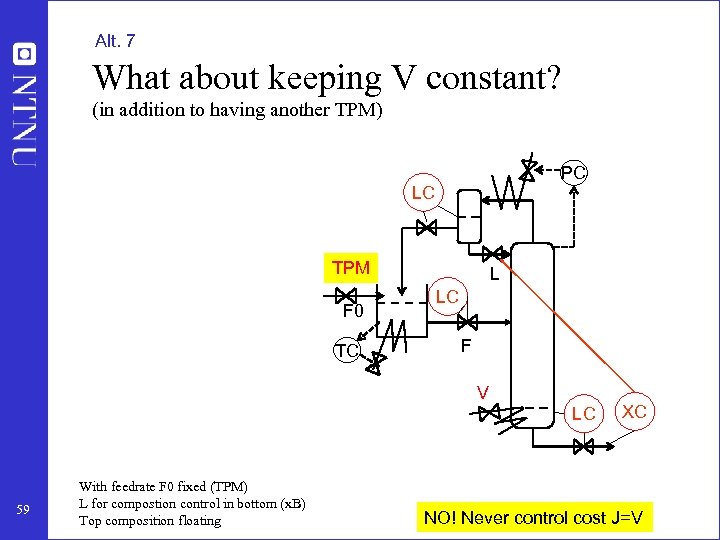

Alt. 7 What about keeping V constant? (in addition to having another TPM) PC LC TPM F 0 TC L LC F V LC 59 With feedrate F 0 fixed (TPM) L for compostion control in bottom (x. B) Top composition floating XC NO! Never control cost J=V

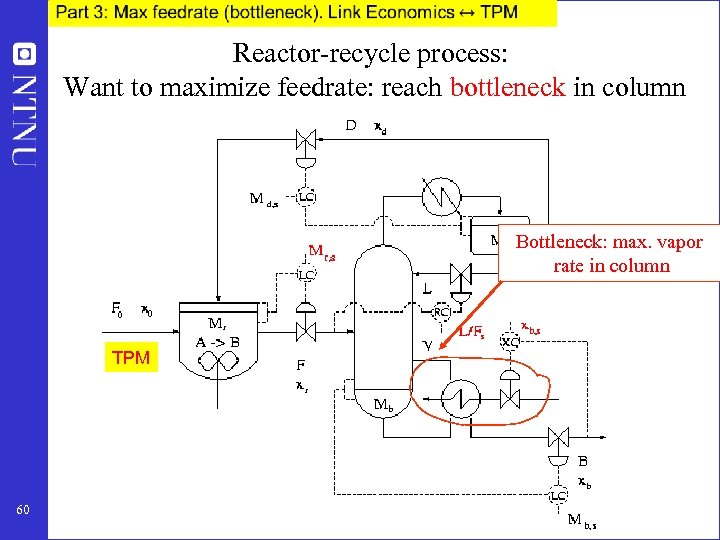

Reactor-recycle process: Want to maximize feedrate: reach bottleneck in column Bottleneck: max. vapor rate in column TPM 60

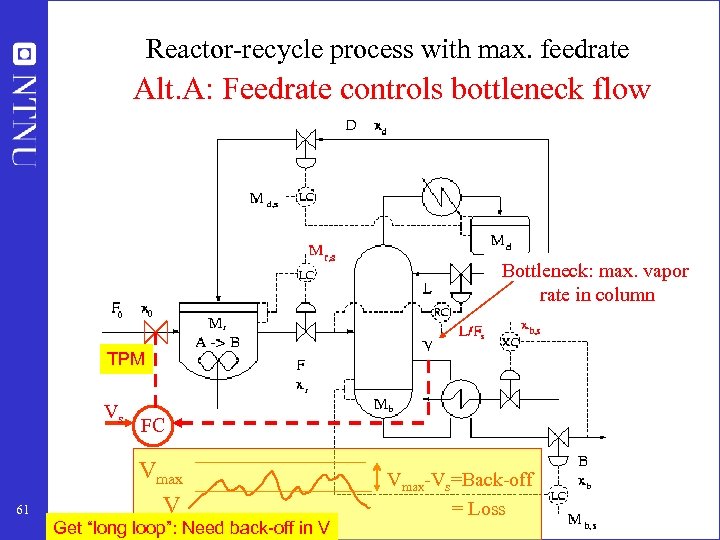

Reactor-recycle process with max. feedrate Alt. A: Feedrate controls bottleneck flow Bottleneck: max. vapor rate in column TPM Vs 61 FC Vmax V Get “long loop”: Need back-off in V Vmax-Vs=Back-off = Loss

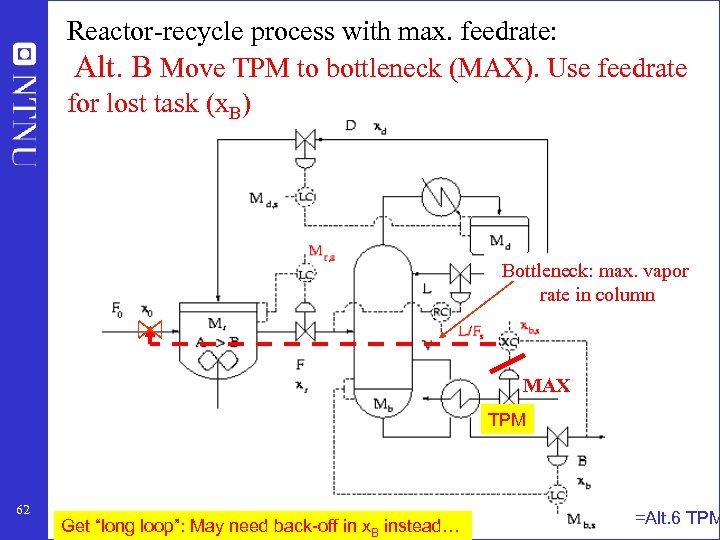

Reactor-recycle process with max. feedrate: Alt. B Move TPM to bottleneck (MAX). Use feedrate for lost task (x. B) Bottleneck: max. vapor rate in column MAX TPM 62 Get “long loop”: May need back-off in x. B instead… =Alt. 6 TPM

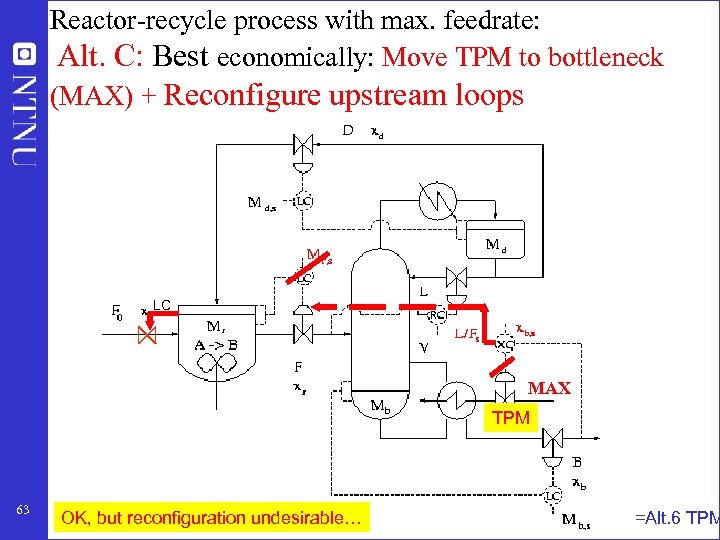

Reactor-recycle process with max. feedrate: Alt. C: Best economically: Move TPM to bottleneck (MAX) + Reconfigure upstream loops LC MAX TPM 63 OK, but reconfiguration undesirable… =Alt. 6 TPM

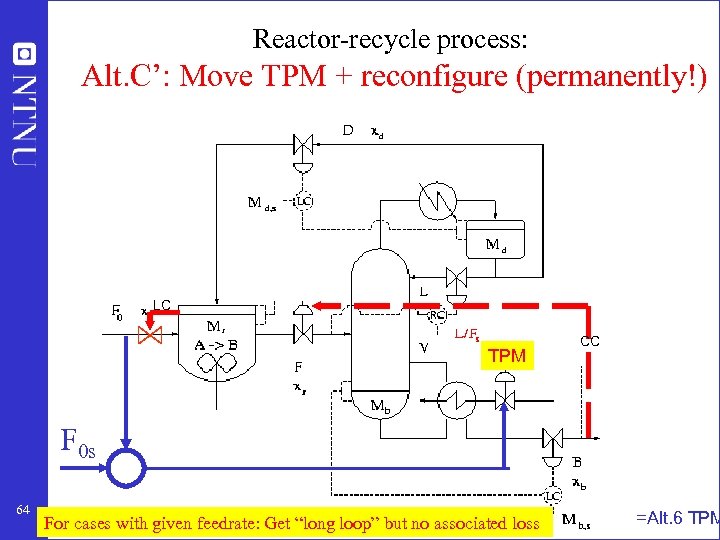

Reactor-recycle process: Alt. C’: Move TPM + reconfigure (permanently!) LC TPM CC F 0 s 64 For cases with given feedrate: Get “long loop” but no associated loss =Alt. 6 TPM

Alt. 4: Multivariable control (MPC) • Can reduce loss • BUT: Is generally placed on top of the regulatory control system (including level loops), so it still important where the production rate is set! • One approach: Put MPC on top that coordinates flows through plant • By manipulating feed rate and other ”unused” degrees of freedom (including level setpoints): • E. M. B. Aske, S. Strand S. Skogestad, • ``Coordinator MPC for maximizing plant throughput'', • Computers and Chemical Engineering, 32, 195 -204 (2008). 65

Conclusion TPM (production rate manipulator) • Think carefully about where to place it! • Difficult to undo later 70

Session 5: Design of regulatory control layer 71

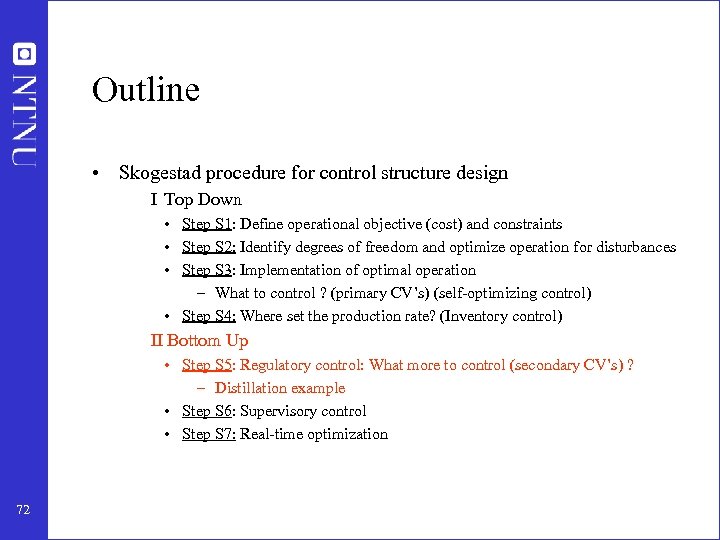

Outline • Skogestad procedure for control structure design I Top Down • Step S 1: Define operational objective (cost) and constraints • Step S 2: Identify degrees of freedom and optimize operation for disturbances • Step S 3: Implementation of optimal operation – What to control ? (primary CV’s) (self-optimizing control) • Step S 4: Where set the production rate? (Inventory control) II Bottom Up • Step S 5: Regulatory control: What more to control (secondary CV’s) ? – Distillation example • Step S 6: Supervisory control • Step S 7: Real-time optimization 72

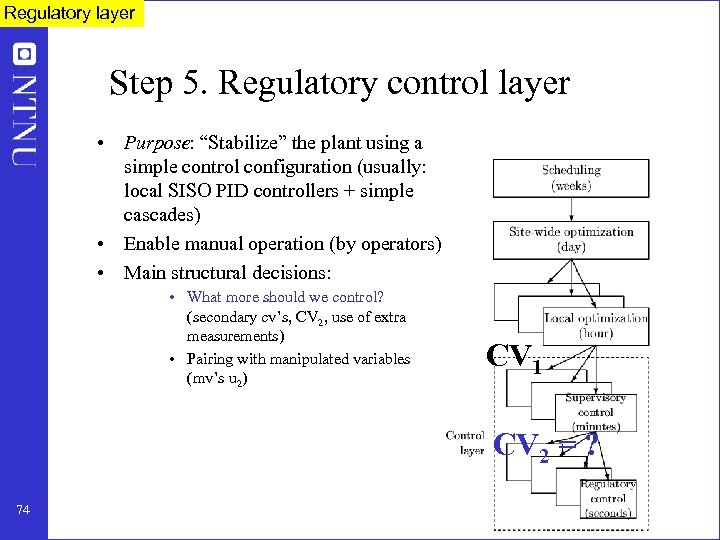

Regulatory layer Step 5. Regulatory control layer • Purpose: “Stabilize” the plant using a simple control configuration (usually: local SISO PID controllers + simple cascades) • Enable manual operation (by operators) • Main structural decisions: • What more should we control? (secondary cv’s, CV 2, use of extra measurements) • Pairing with manipulated variables (mv’s u 2) CV 1 CV 2 = ? 74

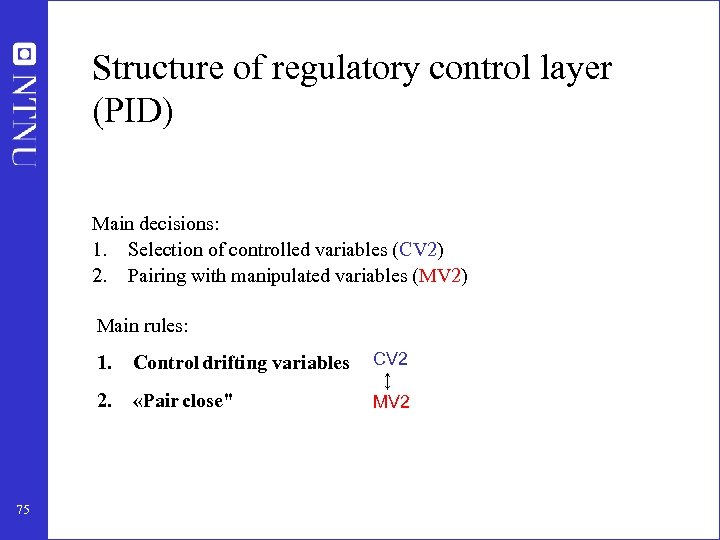

Structure of regulatory control layer (PID) Main decisions: 1. Selection of controlled variables (CV 2) 2. Pairing with manipulated variables (MV 2) Main rules: 1. Control drifting variables 2. «Pair close" 75 CV 2 ↕ MV 2

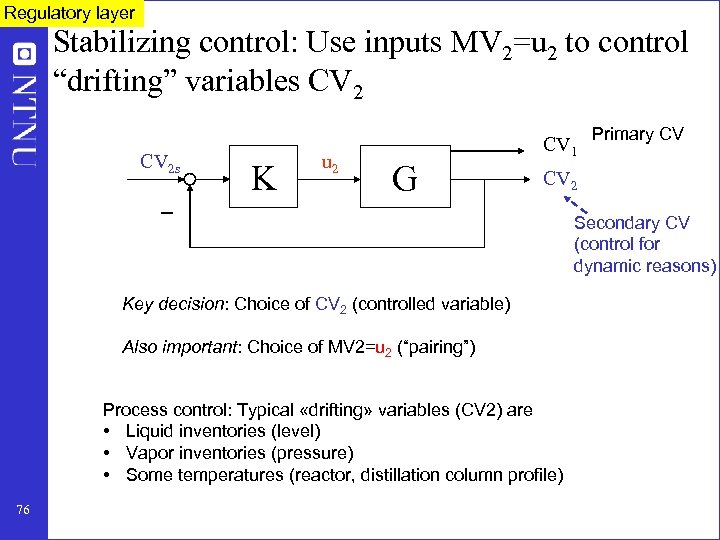

Regulatory layer Stabilizing control: Use inputs MV 2=u 2 to control “drifting” variables CV 2 s K u 2 G CV 1 Primary CV CV 2 Secondary CV (control for dynamic reasons) Key decision: Choice of CV 2 (controlled variable) Also important: Choice of MV 2=u 2 (“pairing”) Process control: Typical «drifting» variables (CV 2) are • Liquid inventories (level) • Vapor inventories (pressure) • Some temperatures (reactor, distillation column profile) 76

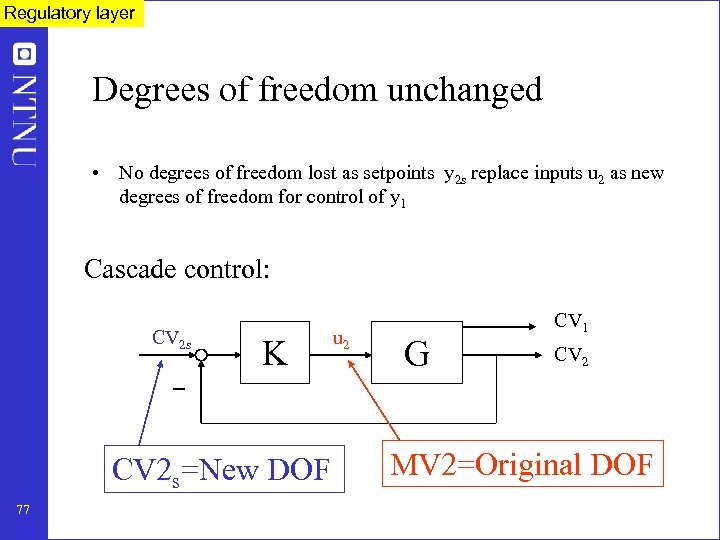

Regulatory layer Degrees of freedom unchanged • No degrees of freedom lost as setpoints y 2 s replace inputs u 2 as new degrees of freedom for control of y 1 Cascade control: CV 2 s K CV 2 s=New DOF 77 u 2 G CV 1 CV 2 MV 2=Original DOF

Regulatory layer Objectives regulatory control layer 1. 2. 3. 4. 5. 6. 7. Allow for manual operation Simple decentralized (local) PID controllers that can be tuned on-line Take care of “fast” control Track setpoint changes from the layer above Local disturbance rejection Stabilization (mathematical sense) Avoid “drift” (due to disturbances) so system stays in “linear region” – “stabilization” (practical sense) 78 8. Allow for “slow” control in layer above (supervisory control) 9. Make control problem easy as seen from layer above 10. Use “easy” and “robust” measurements (pressure, temperature) 11. Simple structure 12. Contribute to overall economic objective (“indirect” control) 13. Should not need to be changed during operation

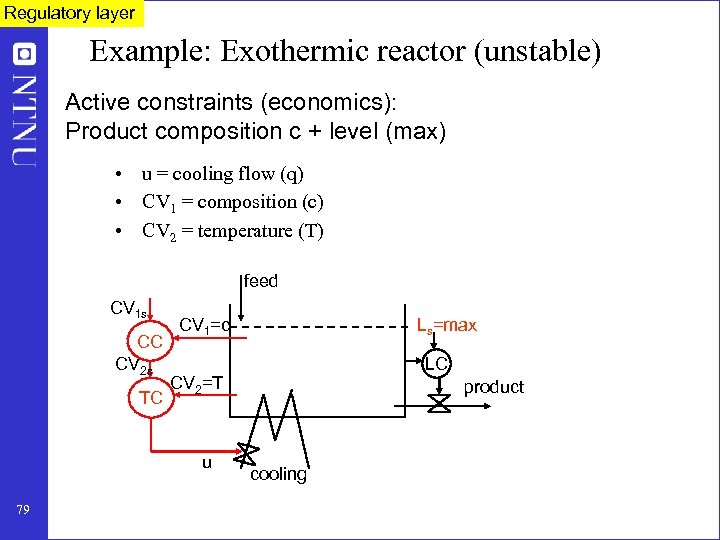

Regulatory layer Example: Exothermic reactor (unstable) Active constraints (economics): Product composition c + level (max) • u = cooling flow (q) • CV 1 = composition (c) • CV 2 = temperature (T) feed CV 1 s CC CV 2 s TC CV 1=c LC CV 2=T u 79 Ls=max product cooling

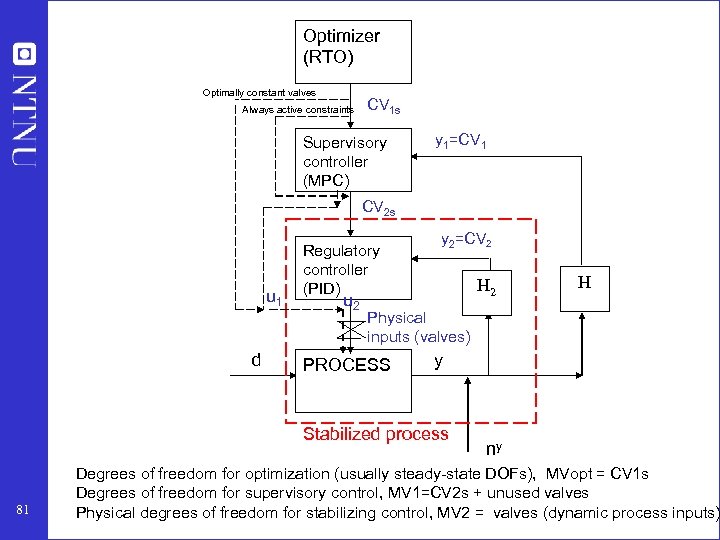

Optimizer (RTO) Optimally constant valves Always active constraints CV 1 s Supervisory controller (MPC) y 1=CV 1 CV 2 s u 1 d Regulatory controller (PID) u 2 y 2=CV 2 H 2 Physical inputs (valves) PROCESS y Stabilized process 81 H ny Degrees of freedom for optimization (usually steady-state DOFs), MVopt = CV 1 s Degrees of freedom for supervisory control, MV 1=CV 2 s + unused valves Physical degrees of freedom for stabilizing control, MV 2 = valves (dynamic process inputs)

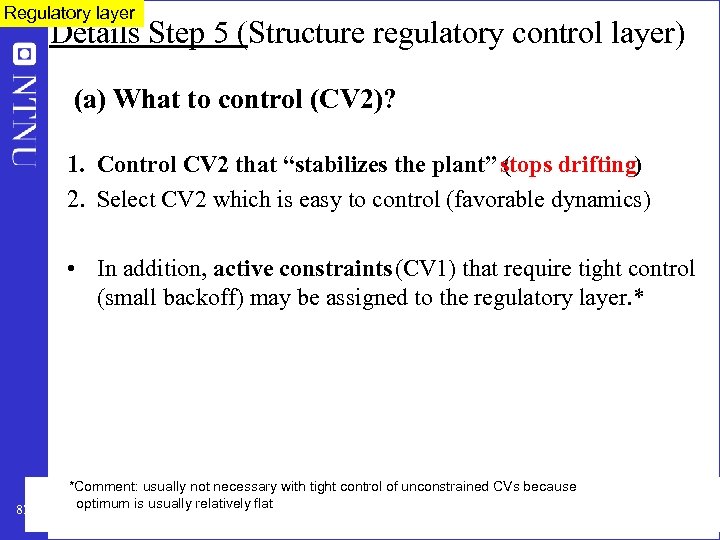

Regulatory layer Details Step 5 (Structure regulatory control layer) (a) What to control (CV 2)? 1. Control CV 2 that “stabilizes the plant” stops drifting) ( 2. Select CV 2 which is easy to control (favorable dynamics) • In addition, active constraints (CV 1) that require tight control (small backoff) may be assigned to the regulatory layer. * 82 *Comment: usually not necessary with tight control of unconstrained CVs because optimum is usually relatively flat

Regulatory layer “Control CV 2 that stabilizes the plant (stops drifting)” In practice, control: 1. Levels (inventory liquid) 2. Pressures (inventory gas/vapor) (note: some pressures may be left floating) 3. Inventories of components that may accumulate/deplete inside plant • • • E. g. , amine/water depletes in recycle loop in CO 2 capture plant E. g. , butanol accumulates in methanol-water distillation column E. g. , inert N 2 accumulates in ammonia reactor recycle 4. Reactor temperature 5. Distillation column profile (one temperature inside column) • Stripper/absorber profile does not generally need to be stabilized 84

Regulatory layer Details Step 5 b…. (b) Identify pairings = Identify MVs (u 2) to control CV 2, taking into account : • • Avoid selecting as MVs in the regulatory layer, variables that may optimally saturate at steady-state (active constraint on some region), because this would require either – reassigning the regulatory loop (complication penalty), or – requiring back-off for the MV variable (economic penalty) • Want tight control of important active constraints (to avoid back-off) • 85 Want “local consistency” for the inventory control – Implies radiating inventory control around given flow General rule: ”pair close” (see next slide)

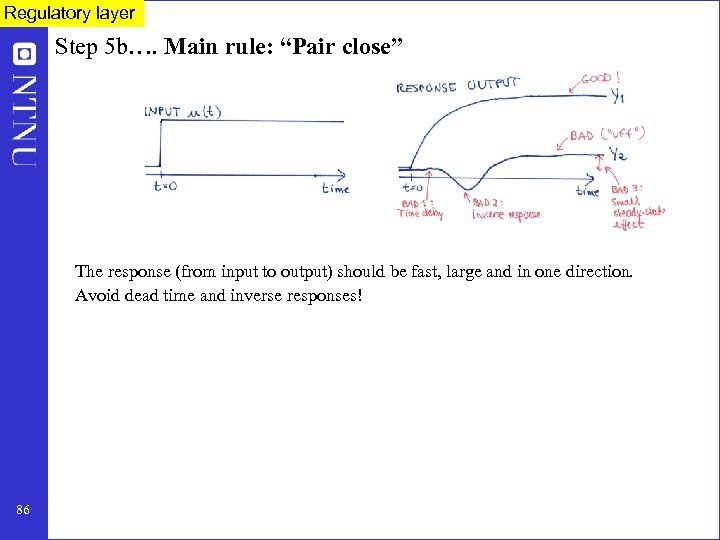

Regulatory layer Step 5 b…. Main rule: “Pair close” The response (from input to output) should be fast, large and in one direction. Avoid dead time and inverse responses! 86

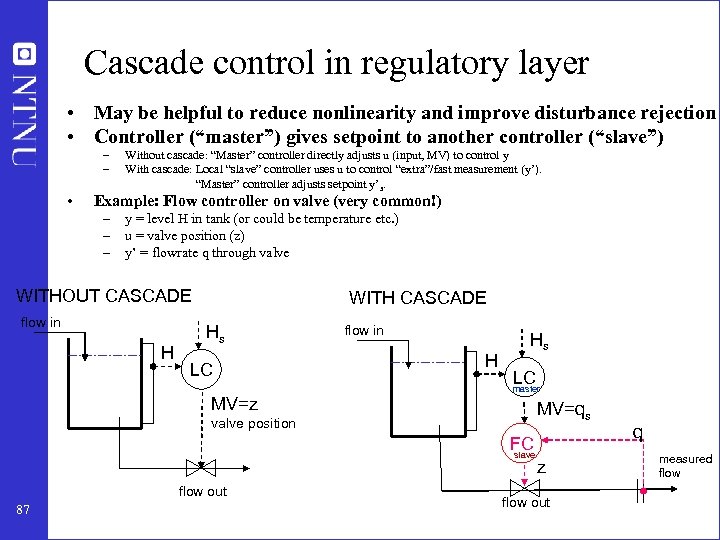

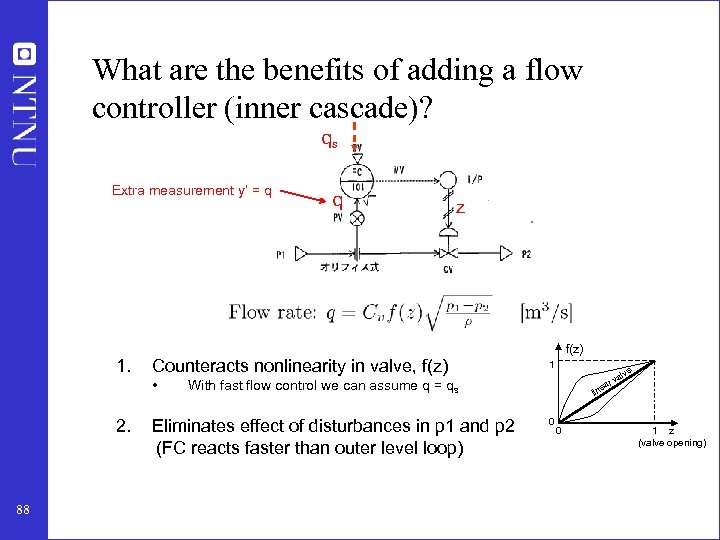

Cascade control in regulatory layer • May be helpful to reduce nonlinearity and improve disturbance rejection • Controller (“master”) gives setpoint to another controller (“slave”) – – • Without cascade: “Master” controller directly adjusts u (input, MV) to control y With cascade: Local “slave” controller uses u to control “extra”/fast measurement (y’). “Master” controller adjusts setpoint y’ s. Example: Flow controller on valve (very common!) – – – y = level H in tank (or could be temperature etc. ) u = valve position (z) y’ = flowrate q through valve WITHOUT CASCADE flow in H WITH CASCADE Hs LC MV=z flow in H Hs LC master MV=qs valve position FC slave flow out 87 z flow out q measured flow

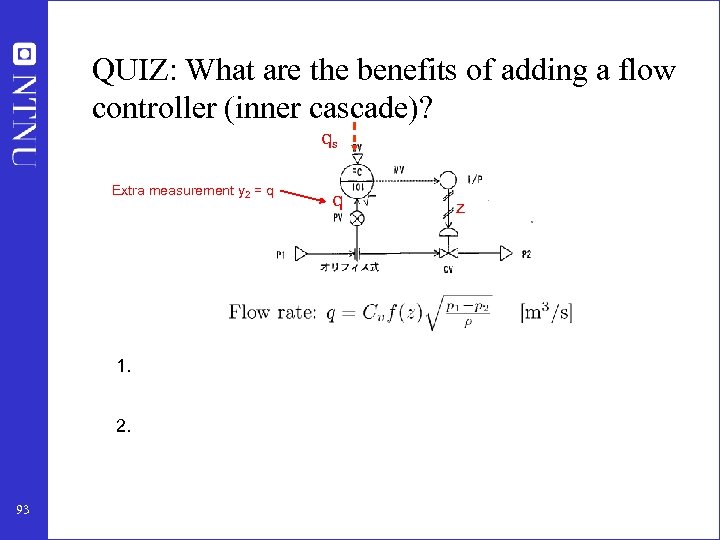

What are the benefits of adding a flow controller (inner cascade)? qs Extra measurement y’ = q 1. q z Counteracts nonlinearity in valve, f(z) • 1 v ar With fast flow control we can assume q = qs 2. Eliminates effect of disturbances in p 1 and p 2 (FC reacts faster than outer level loop) 88 f(z) e alv e lin 0 0 1 z (valve opening)

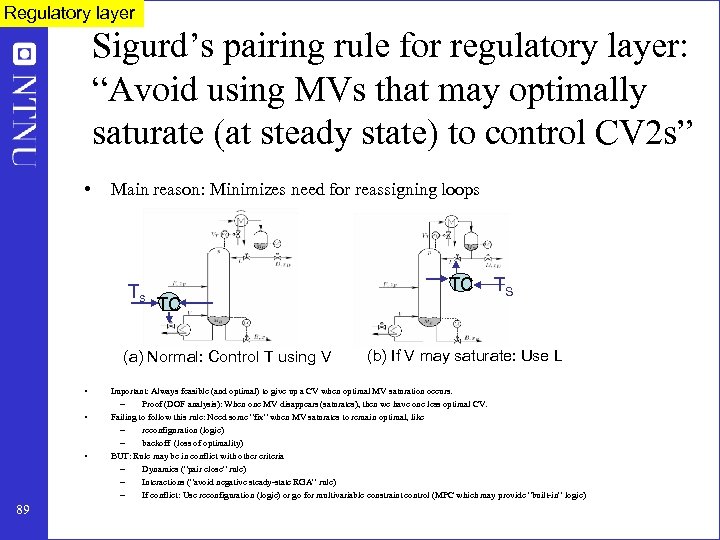

Regulatory layer Sigurd’s pairing rule for regulatory layer: “Avoid using MVs that may optimally saturate (at steady state) to control CV 2 s” • Main reason: Minimizes need for reassigning loops . loop LV Ts TC (a) Normal: Control T using V • • • 89 TC TS (b) If V may saturate: Use L Important: Always feasible (and optimal) to give up a CV when optimal MV saturation occurs. – Proof (DOF analysis): When one MV disappears (saturates), then we have one less optimal CV. Failing to follow this rule: Need some “fix” when MV saturates to remain optimal, like – reconfiguration (logic) – backoff (loss of optimality) BUT: Rule may be in conflict with other criteria – Dynamics (“pair close” rule) – Interactions (“avoid negative steady-state RGA” rule) – If conflict: Use reconfiguration (logic) or go for multivariable constraint control (MPC which may provide “built-in” logic)

Regulatory layer Why simplified configurations? Why control layers? Why not one “big” multivariable controller? • Fundamental: Save on modelling effort • Other: – – – 90 easy to understand easy to tune and retune insensitive to model uncertainty possible to design for failure tolerance fewer links reduced computation load

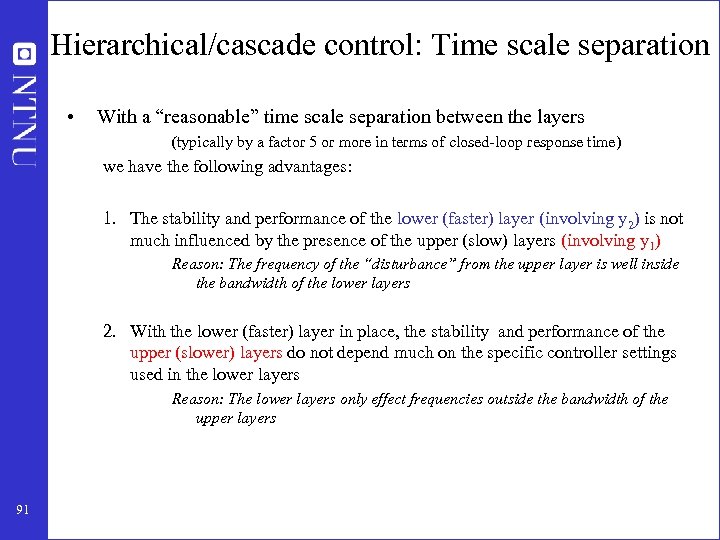

Hierarchical/cascade control: Time scale separation • With a “reasonable” time scale separation between the layers (typically by a factor 5 or more in terms of closed-loop response time) we have the following advantages: 1. The stability and performance of the lower (faster) layer (involving y 2) is not much influenced by the presence of the upper (slow) layers (involving y 1) Reason: The frequency of the “disturbance” from the upper layer is well inside the bandwidth of the lower layers 2. With the lower (faster) layer in place, the stability and performance of the upper (slower) layers do not depend much on the specific controller settings used in the lower layers Reason: The lower layers only effect frequencies outside the bandwidth of the upper layers 91

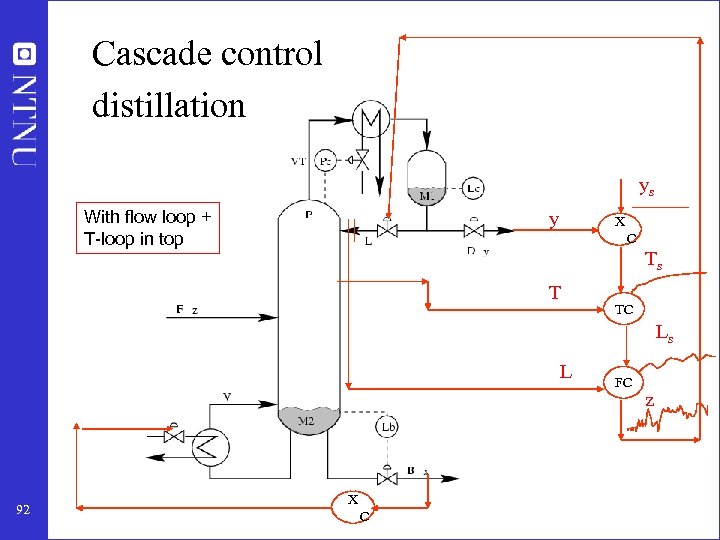

Cascade control distillation ys With flow loop + T-loop in top y X C Ts T TC Ls L 92 FC z X C

QUIZ: What are the benefits of adding a flow controller (inner cascade)? qs Extra measurement y 2 = q 1. 93 z Counteracts nonlinearity in valve, f(z) • 2. q With fast flow control we can assume q = qs Eliminates effect of disturbances in p 1 and p 2

Summary: Rules for plantwide control • Here we present a set of simple rules for economic plantwide control to facilitate a close-to-optimal control structure design in cases where the optimization of the plant model is not possible. • the rules may be conflicting in some cases and in such cases, human reasoning is strongly advised. 94

Rules for Step S 3: Selection of primary (economic) controlled variables, CV 1 Rule 1: Control the active constraints. • In general, process optimization is required to determine the active constraints, but in many cases these can be identified based on a good process knowledge and engineering insight. Here is one useful rule: • Rule 1 A: The purity constraint of the valuable product is always active and should be controlled. • • • 95 This follows, because we want to maximize the amount of valuable product and avoid product “give away” (Jacobsen and Skogestad, 2011). Thus, we should always control the purity of the valuable product at its specification. For “cheap” products we may want to overpurify (purity constraint may not be active) because this may reduce the loss of a more valuable component. In other cases, we must rely on our process knowledge and engineering insight. For reactors with simple kinetics, we usually find that, the reaction and conversion rates are maximized by operating at maximum temperature and maximum volume (liquid phase reactor). For gas phase reactor, high pressure may increase the reaction rate, but this must be balanced against the compression costs.

Rule 2: (for remaining unconstrained steady-state degrees of freedom, if any): Control the “self-optimizing” variables. • This choice is usually not obvious, as there may be several alternatives, so this rule is in itself not very helpful. The ideal self-optimizing variable, at least, if it can be measured accurately, is the gradient of the cost function. Ju, which should be zero for any disturbance. Unfortunately, it is rarely possible to measure this variable directly and the “self-optimizing” variable may be viewed as an estimate of the gradient Ju The two main properties of a good “self-optimizing” (CV 1=c=Hy) variable are: 1. Its optimal value is insensitive to disturbances (such that the optimal sensitivity dcopt/dd =Fc HF = is small) 2. It is sensitive to the plant inputs (so the process gain dc/du = G = HGy is large). The following rule shows how to combine the two desired properties: • Rule 2 A: Select the set CV 1=c such that the ratio G-1 Fc is minimized. • 96 This rule is often called the “maximum scaled gain rule”.

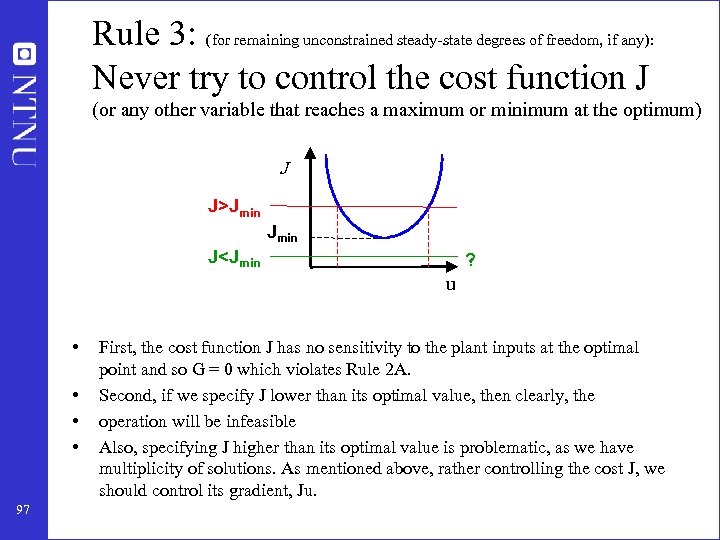

Rule 3: (for remaining unconstrained steady-state degrees of freedom, if any): Never try to control the cost function J (or any other variable that reaches a maximum or minimum at the optimum) J J>Jmin J<Jmin ? u • • 97 First, the cost function J has no sensitivity to the plant inputs at the optimal point and so G = 0 which violates Rule 2 A. Second, if we specify J lower than its optimal value, then clearly, the operation will be infeasible Also, specifying J higher than its optimal value is problematic, as we have multiplicity of solutions. As mentioned above, rather controlling the cost J, we should control its gradient, Ju.

Rules for Step S 4: Location of throughput manipulator (TPM) Rule 4: Locate the TPM close to the process bottleneck. • The justification for this rule is to take advantage of the large economic benefits of maximizing production in times when product prices are high relative to feed and energy costs (Mode 2). To maximize the production rate, one needs to achieve tight control of the active constraints, in particular, of the bottleneck, which is defined as the last constraint to become active when increasing the throughput rate (Jagtap et al. , 2013). 98

Rule 5: (for processes with recycle) Locate the TPM inside the recycle loop. • The point is to avoid “overfeeding” the recycle loop which may easily occur if we operate close to the throughput where “snowballing” in the recycle loop occurs. This is a restatement of Luyben’s rule “Fix a Flow in Every Recycle Loop” (Luyben et al. , 1997). From this perspective, snowballing can be thought of as the dynamic consequence of operating close to a bottleneck which is within a recycle system. • In many cases, the process bottleneck is located inside the recycle loop and Rules 4 and 5 give the same result. 99

Rules for Step S 5: Structure of regulatory control layer. Rule 6: Arrange the inventory control loops (for level, pressures, etc. ) around the TPM location according to the radiation rule. • The radiation rule (Price et al. , 1994), says that, the inventory loops upstream of the TPM location must be arranged opposite of flow direction. For flow downstream of TPM location it must be arranged in the same direction. This ensures “local consistency” i. e. all inventories are controlled by their local in or outflows. 10 0

Rule 7: Select “sensitive/drifting” variables as controlled variables CV 2 for regulatory control. • This will generally include inventories (levels and pressures), plus certain other drifting (integrating) variables, for example, – a reactor temperature – a sensitive temperature/composition in a distillation column. • This ensures “stable operation, as seen from an operator’s point of view. • Some component inventories may also need to be controlled, especially for recycle systems. For example, according to “Down’s drill” one must make sure that all component inventories are “selfregulated” by flows out of the system or by removal by reactions, otherwise their composition may need to be controlled (Luyben, 1999). 10 1

Rule 8: Economically important active constraints (a subset of CV 1), should be selected as controlled variables CV 2 in the regulatory layer. • Economic variables, CV 1, are generally controlled in the supervisory layer. Moving them to the faster regulatory layer may ensure tighter control with a smaller backoff. • Backoff: difference between the actual average value (setpoint) and the optimal value (constraint). 10 2

Rule 9: “Pair-close” rule: The pairings should be selected such that, effective delays and loop interactions are minimal. 10 3

Rule 10: : Avoid using MVs that may optimally saturate (at steady state) to control CVs in the regulatory layer (CV 2) • The reason is that we want to avoid re-configuring the regulatory control layer. To follow this rule, one needs to consider also other regions of operation than the nominal, for example, operating at maximum capacity (Mode 2) where we usually have more active constraints. 10 4

Rules for Step S 6: Structure of supervisory control layer. Rule 11: MVs that may optimally saturate (at steady state) should be paired with the subset of CV 1 that may be given up. • This rule applies for cases when we use decentralized control in the supervisory layer and we want to avoid reconfiguration of loops. • The rule follows because when a MV optimally saturates, then there will be one less degree of freedom, so there will be a CV 1 which may be given up without any economic loss. The rule should be considered together with rule 10. • Example: Gives correct answer for the process where we want to control flow and have p>pmin: Pair the valve (MV) with CV 1 (p) which may be given up. 10 5

Plantwide control. Main references • The following paper summarizes the procedure: – S. Skogestad, ``Control structure design for complete chemical plants'', Computers and Chemical Engineering, 28 (1 -2), 219 -234 (2004). • There are many approaches to plantwide control as discussed in the following review paper: – T. Larsson and S. Skogestad, ``Plantwide control: A review and a new design procedure'' Modeling, Identification and Control, 21, 209 -240 (2000). • The following paper updates the procedure: – S. Skogestad, ``Economic plantwide control’’, Book chapter in V. Kariwala and V. P. Rangaiah (Eds), Plant-Wide Control: Recent Developments and Applications”, Wiley (2012). • More information: http: //www. ntnu. no/users/skoge/plantwide 10 6 All papers available at: http: //www. ntnu. no/users/skoge/

d6e2bc29b15cc6b5c7cbed962b940d6b.ppt