717635f41ec5f066e606e9c9ca1e70a6.ppt

- Количество слайдов: 81

Over the Counter, Prescription only Medicines and Benzodiazepines

Four out of five people aged over 75 years take at least one medicine. 36 per cent of this age group take at least four medicines. The Audit Commission calculated ADRs cost the NHS £ 0. 5 billion each year in longer stays in hospital.

“A Pill for every Ill” Rise of pharmaceutical giants R&D and marketing

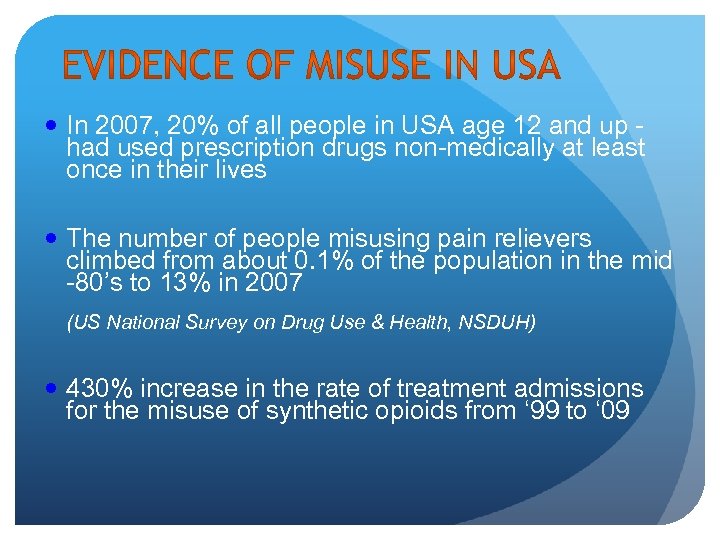

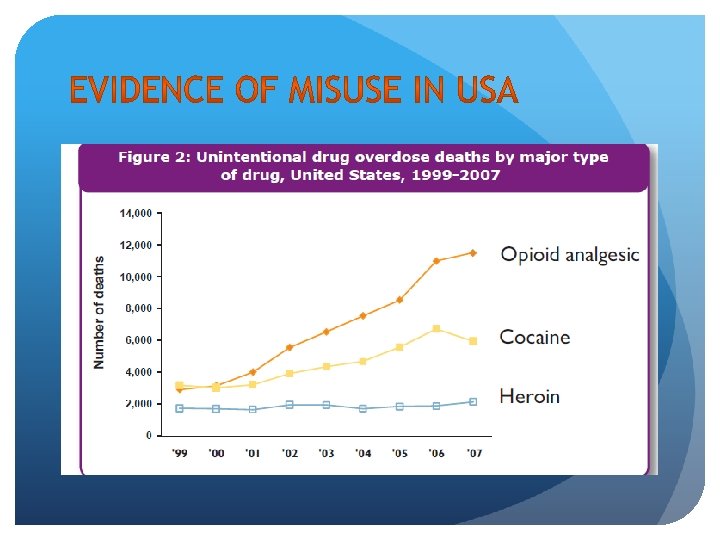

In 2007, 20% of all people in USA age 12 and up - had used prescription drugs non-medically at least once in their lives The number of people misusing pain relievers climbed from about 0. 1% of the population in the mid -80’s to 13% in 2007 (US National Survey on Drug Use & Health, NSDUH) 430% increase in the rate of treatment admissions for the misuse of synthetic opioids from ‘ 99 to ‘ 09

Addictive drugs: e. g. opiates (oxycodone, tramadol), codeine-based, benzodiazepines Often with physical withdrawal syndrome Non-addictive drugs may still be abused: for their effects e. g. tricyclics for regular self-medication e. g. antihistamine for sleep in a compulsive way e. g. laxatives to enhance the effects of other drugs e. g. SSRI’s

Gabapentin Pregabalin Amitriptyline SSRI’s

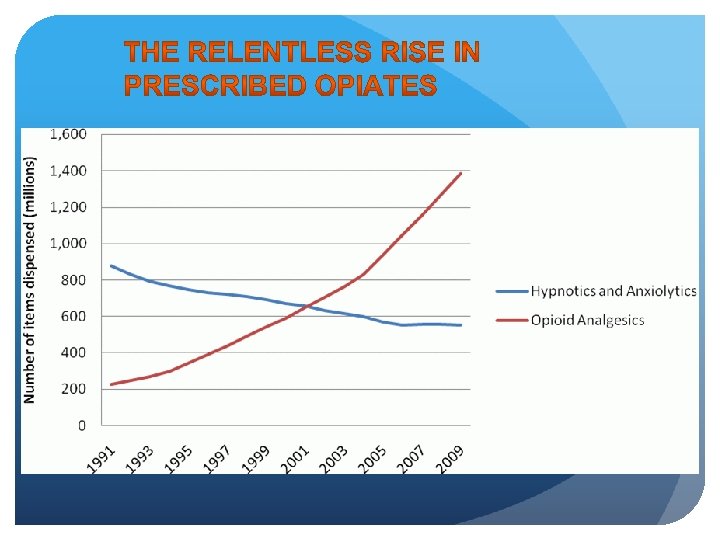

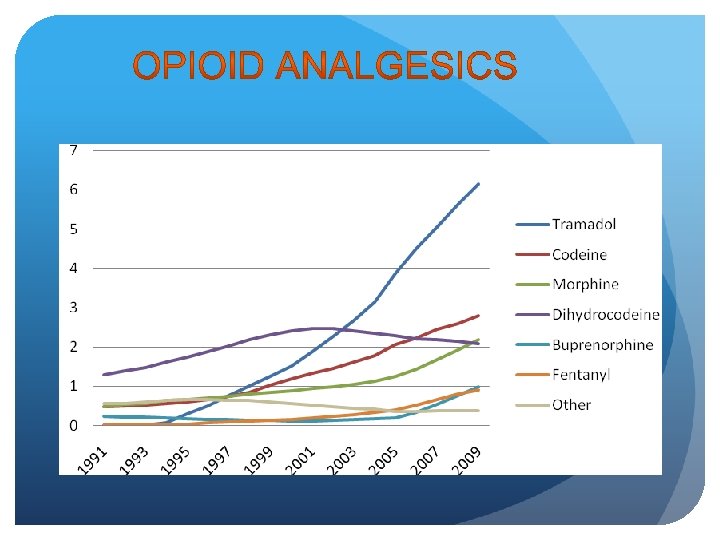

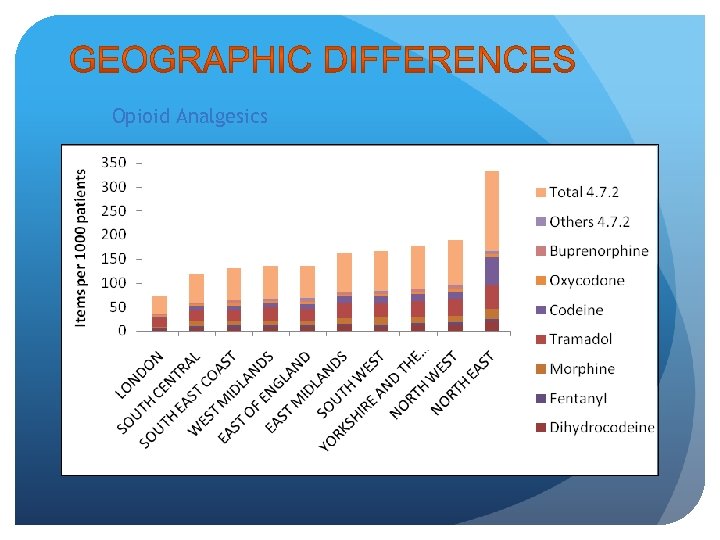

Opioid Analgesics

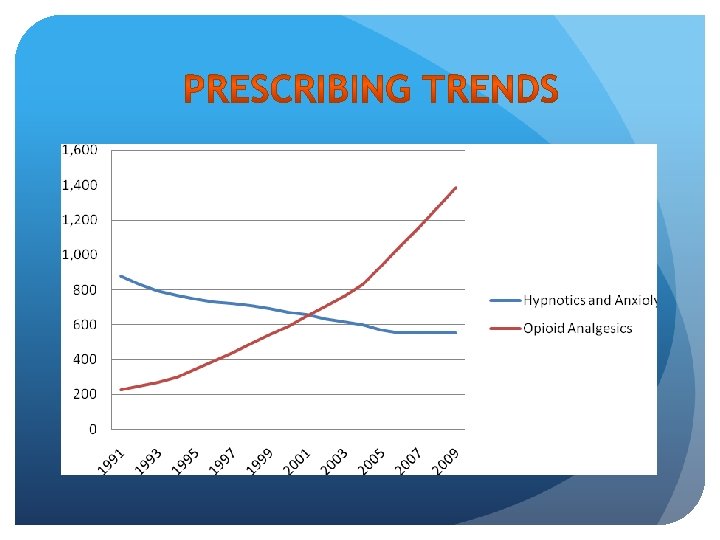

Trend data tells us something about the use of these medicines Levels of prescribing can identify areas where there might need to be further focus (particularly at a practise level. ) But: Higher levels of prescribing do not necessarily mean that these drugs are not being used appropriately.

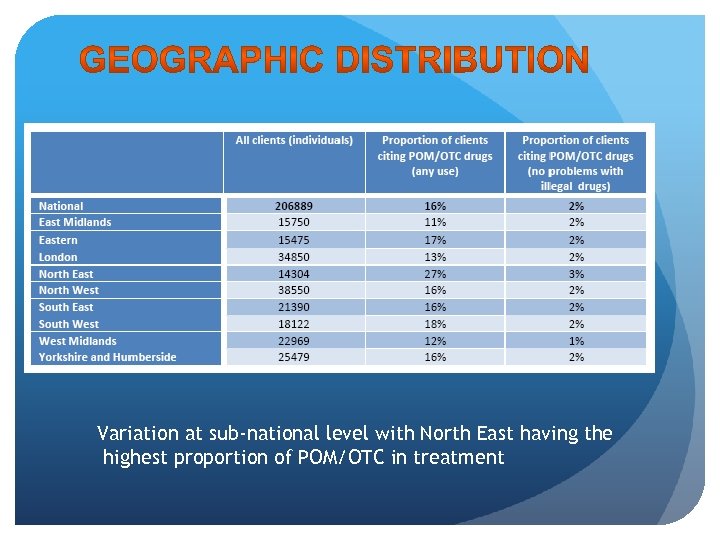

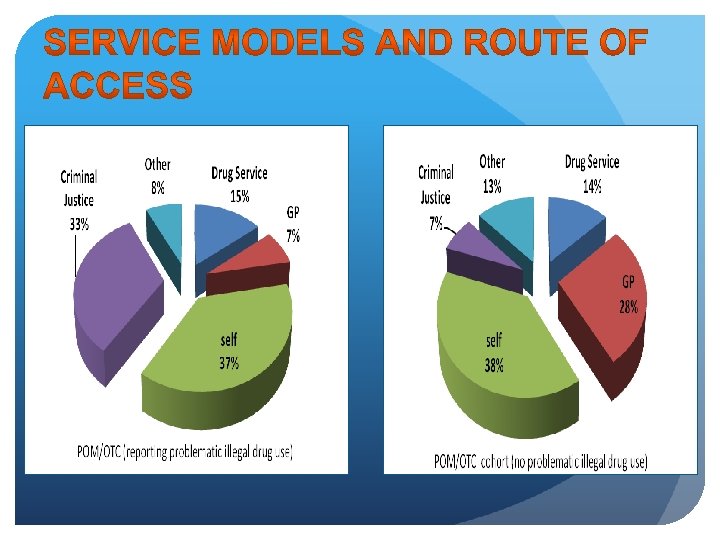

In 2009/10 there were 32, 510 people reporting POM/OTC (16% of treatment population) 11% of these (3, 735) POM/OTC only Most local areas provide treatment

Variation at sub-national level with North East having the highest proportion of POM/OTC in treatment

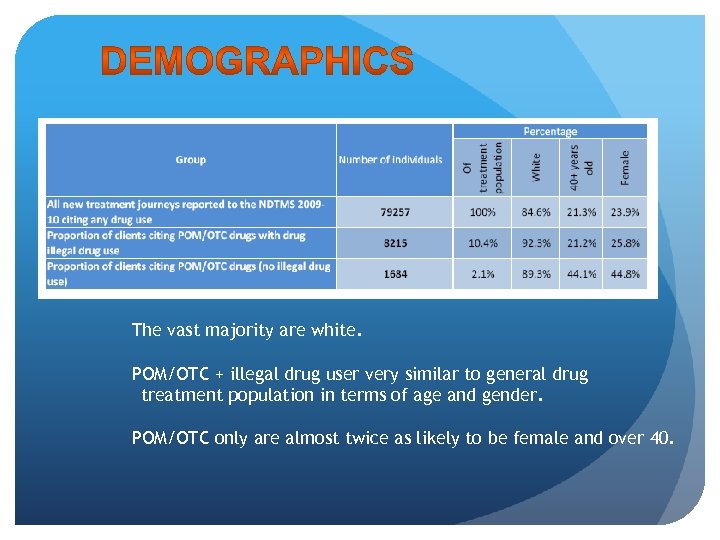

The vast majority are white. POM/OTC + illegal drug user very similar to general drug treatment population in terms of age and gender. POM/OTC only are almost twice as likely to be female and over 40.

Most common codeine containing with either paracetamol or ibuprofen 12. 8 mg per tablet codeine highest dose available 7. 46 mg per tablet dihydrocodeine also available Other medications –laxatives, sedative antihistamines

May present due to effects of co-ingredient May be suspected by pharmacist Difficult to identify Need to specifically ask about OTC meds and usage

1. Can be originally given for acute or chronic problem 2. Positive effect 3. Subsequent reinforcement

• Longer-term prescribing increases the likelihood of dependency. • Does the prevalence of long-term prescribing give us an indication of the prevalence of dependency? • Dependency is not inevitable • There are conditions where long term prescribing is advised

Can have dependency along with mental health problems Physical co-morbidity common Self-medication psychological or physical Prevalence chronic pain is 30 -50% in treated substance users, compared with 10 -15% of the general population

1. Psychological – shame hidden problem, unable to get help 2. Effect dependency on self, family and others e. g. depression, loss of work 3. Lapse into another addiction e. g. alcohol, opioids 4. Physical consequences of active ingredient e. g. codeine, constipation, 5. Physical consequences of another ingredient e. g. paracetamol OD

Patients: Older adults Adolescents Women Along with other illicit drugs Healthcare professionals: Doctors Nurses Pharmacists Dentists Prison population Anaesthetists Veterinary surgeons

Over Count Study those patients who approached there GPs saying that they felt they had a problem didn’t get the help and support they required

ATM poorly recognised by clinicians and patients Misunderstood and hidden problem Lack training and guidance

That, when GPs prescribe drugs known to have the potential to cause physical dependence or addiction they must: explain these potential risks to the patient set up procedures to monitor the patient. … The practice of repeat prescription without review for these drugs must end”

www. nta. nhs. uk/addiction-to-medicine. aspx

Ask Careful use of repeats Make use of pharmacists (local & PCT) Surveillance (run regular in house reports)

Monitor patients’ use of drugs that may indicate increasing problems and / or tolerance : increasing problems and / or tolerance rapid increases in the amount of a medication needed/frequent lost scripts Frequent requests for refills or running out before due Seeing different doctors in practice

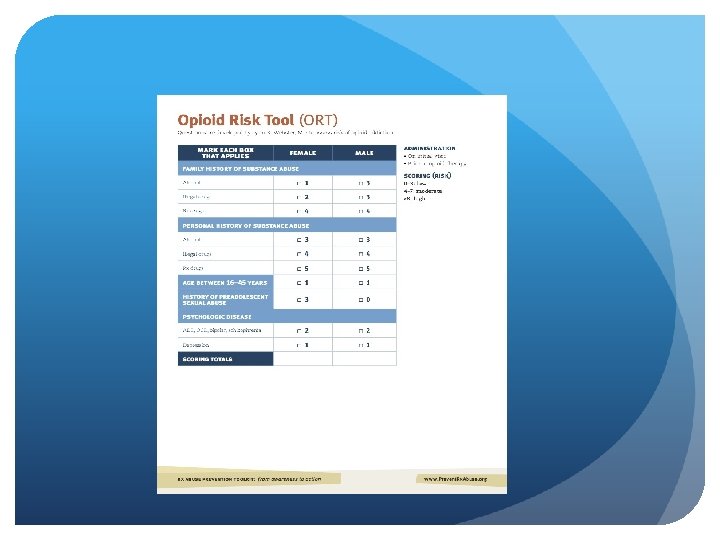

This physician-administered checklist evaluates a series of behaviors that suggest or are consistent with prescription opiate abuse rather than relying on answers to specific questions. Patients meeting 3 or more of the following criteria are considered prescription opiate abusers

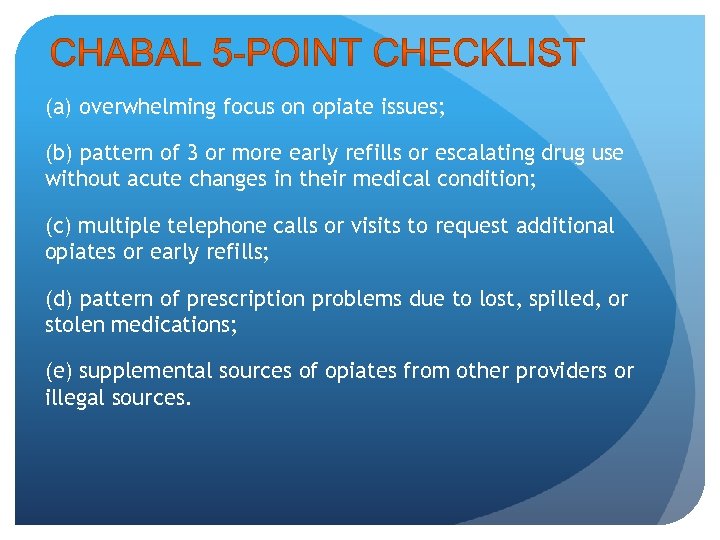

(a) overwhelming focus on opiate issues; (b) pattern of 3 or more early refills or escalating drug use without acute changes in their medical condition; (c) multiple telephone calls or visits to request additional opiates or early refills; (d) pattern of prescription problems due to lost, spilled, or stolen medications; (e) supplemental sources of opiates from other providers or illegal sources.

Prescribe if they are needed for good clinical reasons Put on as acute medications and don’t slip into repeat without discussion or intention Discuss with colleagues and document

1. Assessment 2. Preparation 3. Psychological support 4. Prescribing 5. Wraparound / peer support / groups – local or internet based

Full assessment Ask all about drugs, including OTC and alcohol Drug history, alcohol, other drugs inc. BZ Aspects of dependency: Drug seeking behaviour Lack of interest in other activities Physical withdrawals Mental health assessment - underlying issues? Pain?

Information-Risk of OD, Risk of S/E’s List benefits and adverse things that get from using Keep drug diary of use for 1 -2 weeks Engage with support Explain tolerance

Address anxiety /depression IAPT Counselling / CBT / Motivational interviewing Behavioural change

Buprenorphine Codeine Dihydrocodeine Methadone Morphine (MST, MXL)

Support groups Codeine free me Narcotics Anonymous SMART Social Services Befriending Activity Groups

Stabilisation (drug & psychosocial) Detoxification Aftercare

Good therapeutic relationship Management of associated problems: Mental health issues Pain Wraparound support Psychological interventions Time and patience

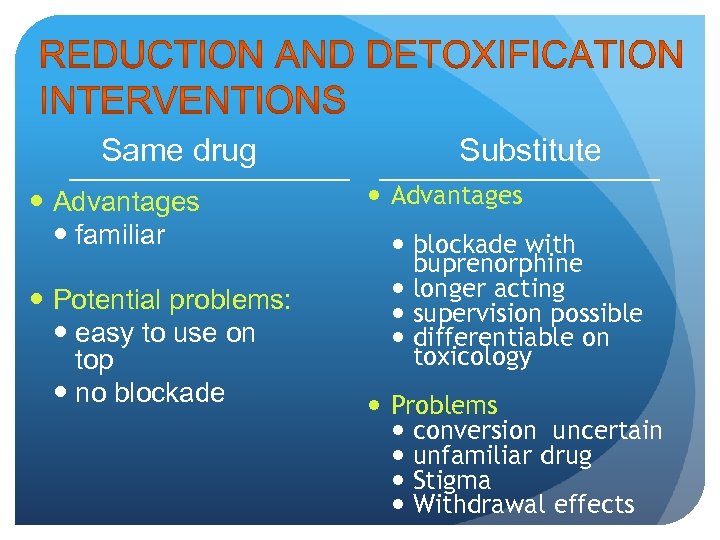

Same drug Advantages familiar Potential problems: easy to use on top no blockade Substitute Advantages blockade with buprenorphine longer acting supervision possible differentiable on toxicology Problems conversion uncertain unfamiliar drug Stigma Withdrawal effects

Under recognised problem, and increasing Evidence growing but scope for further research Little formal guidance and training But many things can do to help Don’t forget: assessment, psychological help, prescribing and group support And detox is only part of the process not the end Important GPs , Pharmacists and all health care professionals are educated about this problem Need for more help and services for people who have problematic use, how should these be delivered?

Case study - Carol, a 46 year old teacher comes to see you with acute abdominal pain. She smokes a few cigarettes a day, and does not drink alcohol. She tells you that she is now taking Nurofen Plus daily; having initially been given them after having some extensive dental work done. When she took them, she found that they helped the pain, and also made her ‘feel better’ and improved her mood. She has no history of substance misuse. She started taking the tablets at the recommended doses, but after a few months felt that they were less effective, especially after a stressful event, so she took more. After 6 months she is now on about 30+ a day.

Carol Around this time her abdominal pain started. When she stops taking the Nurofen, she feels unwell. She has had to find more and more pharmacies to buy from, plus she buys off the internet. She becomes anxious when she knows her supplies are running low. She now desperately wants to stop and wants your help with this. NB: 12. 8 mg codeine (and 200 mg ibuprofen) in x 1 Nurofen Plus tablet, and are available in packs of 12, 24 and 32

Carol What else would your initial assessment involve? What are Carol’s risks? What would be your treatment plan? What are your prescribing options? Who else would you involve?

Case study - Margaret, a 58 year old librarian who has been seeing your senior partner for several years comes to see you as he has reduced his hours and she couldn’t get an appointment with him. She has been told she has fibromyalgia and says the fentanyl 50 patches she has been on for the past 6 months only help so much and she needs to take 6 -8 tramadol a day on top and also has 20 mg of temazepam at night. She had been given a trial of gabapentin but stopped it as it made her feel dizzy.

Margaret She has lived alone since her 86 year old mother died 5 years ago with breast cancer and had a short course of fluoxetine following this although she stopped it after 3 months as she felt ok. She has previously had X-rays which showed minimal osteoarthritis of her hips only. Blood tests showed no evidence of inflammatory arthritis She had no history of drug use and drinks less than 10 units of alcohol / week.

Margaret What else would your initial assessment involve? What are Margaret’s risks? What would be your treatment plan? What are your prescribing options? Who else would you involve?

Case study - Tim, a 52 year old electrician, first saw you about 3 years ago after he had acutely injured his back when he slipped off a ladder. He had gastritis previously so you had given him an acute prescription of co-codamol (30/500) for the back pain. 6 months later he attended with low back pain without any obvious trauma, he was again given cocodamol 30/500. He found them helpful so he attended the emergency surgery - where he saw a locum - to ask for more and he requested them to be added to his repeat prescription, which they were. The reception staff noticed he was overdue a medication review and passed his request for more co-codamol to you.

Tim You realised Tim’s use had gone up and he was requesting 100 tablets at less than 2 weekly intervals so you asked to see him. You knew he had always drunk above safe levels, but from what he told you it had gone up to about 10 units a day since his injury, as he was drinking more because it seemed to help the pain. He said that he was not only using at least 8 prescribed cocodamol a day but he was also buying Solpadeine on top. He was markedly constipated but if he tried stopping the medication developed diarrhoea and abdominal pain and was irritable. Every time he tried to reduce his tablets his alcohol intake went up. His mood was low and he had become withdrawn and isolated, staying in bed till the afternoon in an effort to control the amounts he was using.

Tim He had lost his job a year ago and said he needed a sick note as the benefits office didn’t think he was fit to look for work. . NB Solpadeine Plus is a combination of Codeine Phosphate (8 mg) Paracetamol (500 mg) and Caffeine (30 mg) and is available in packs of 16 and 32 What else would your initial assessment involve? What are Tim's risks? What would be your treatment plan? What are your prescribing options? Who else would you involve?

53

What are the effects of benzodiazepines? What clinical indications are they used in? For how long?

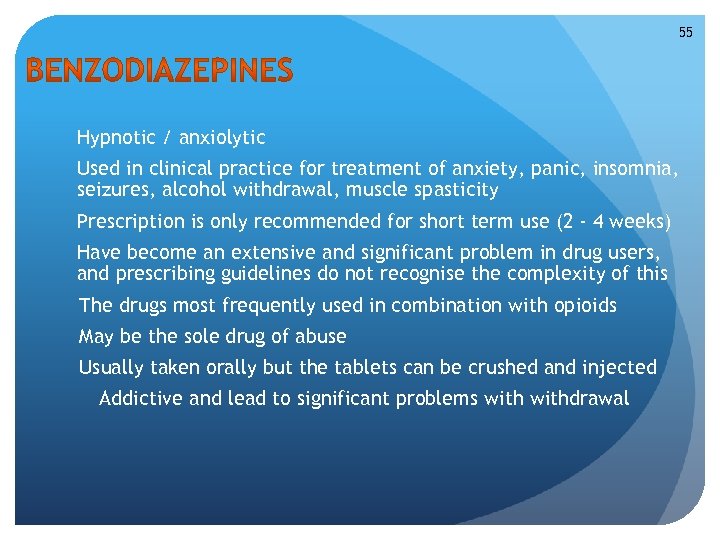

55 Hypnotic / anxiolytic Used in clinical practice for treatment of anxiety, panic, insomnia, seizures, alcohol withdrawal, muscle spasticity Prescription is only recommended for short term use (2 - 4 weeks) Have become an extensive and significant problem in drug users, and prescribing guidelines do not recognise the complexity of this The drugs most frequently used in combination with opioids May be the sole drug of abuse Usually taken orally but the tablets can be crushed and injected Addictive and lead to significant problems withdrawal

56

57 1959, chlordiazepoxide (Librium) was the first of the benzodiazepines to be marketed for insomnia and anxiety. First introduced into clinical practice in the 1960´s benzodiazepines were thought to have distinct advantages over other hypnotics It took less than 10 years for benzodiazepines to replace over 90% of a market previously dominated by the barbiturates, however it became generally accepted that they had many problems of their own, greatly limiting their usefulness.

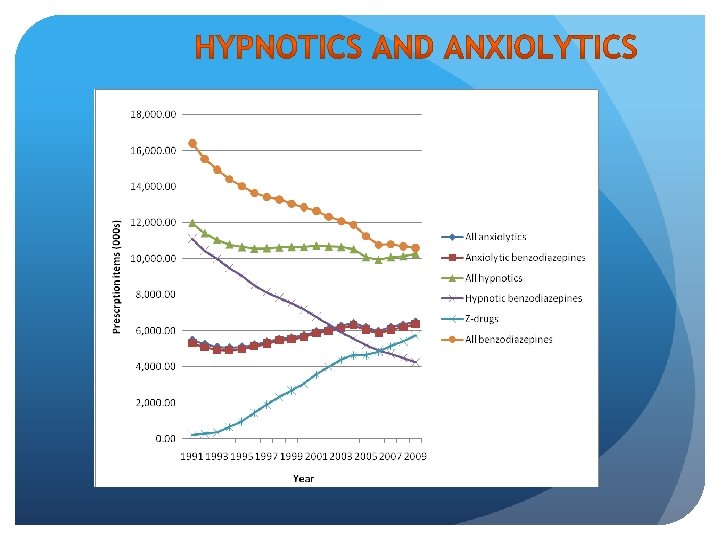

59 Although they possessed a much lower primary toxicity than barbiturates, it was soon known that tolerance, dependence and withdrawals are common in those taking benzodiazepines long-term. 1970’s – 1980’s the volume of benzodiazepine prescribing increased dramatically, reaching a peak in 1979 and has been falling ever since. Even today however there around 0. 5 – 1. 5 million long term-users, with females out numbering men by a ratio of 2: 1.

60 The number of people world-wide who are taking prescribed benzodiazepines is enormous. In US about 2 per cent of the adult population have used prescribed benzodiazepine hypnotics or tranquillisers regularly for 5 to 10 years or more. Studies have shown that between 30 -50 per cent of long-term users have difficulties in stopping benzodiazepines because of withdrawal symptoms. Somewhere between 0. 5 and 1. 5 million people are addicted to benzodiazepines in the UK most of whom are addicted on prescribed medication, and there an estimated 200, 000 illicit benzodiazepine users.

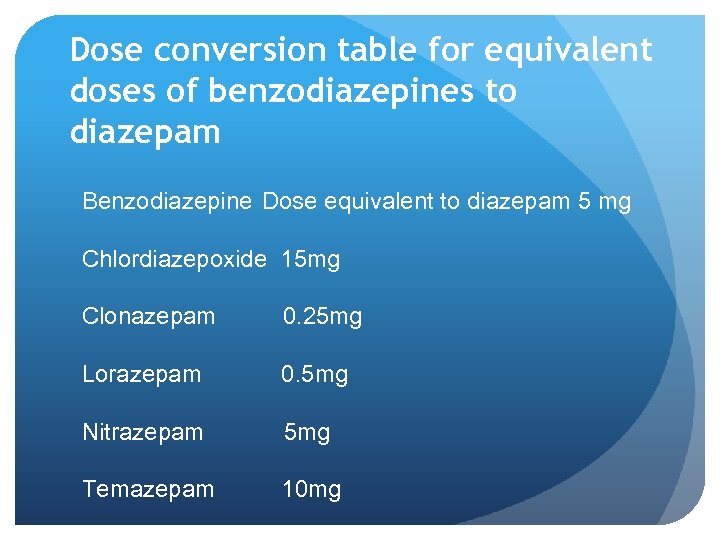

Dose conversion table for equivalent doses of benzodiazepines to diazepam Benzodiazepine Dose equivalent to diazepam 5 mg Chlordiazepoxide 15 mg Clonazepam 0. 25 mg Lorazepam 0. 5 mg Nitrazepam 5 mg Temazepam 10 mg

64 Approximately 90% of drug users report using benzodiazepines at some point The reasons why people use benzodiazepines may include: To make them feel normal, or enable them to cope To treat anxiety or low mood To treat insomnia To potentiate the euphoriant effect of opioids To combat opiate withdrawal symptoms To ‘come down’ from stimulants To improve confidence To decrease psychotic symptoms such as auditory hallucinations To enjoy the effects of a binge High doses or binges can lead to impulsive behaviour, amnesia, increased risky behaviour and other problems Long term benzodiazepine use can lead to emotional suppression

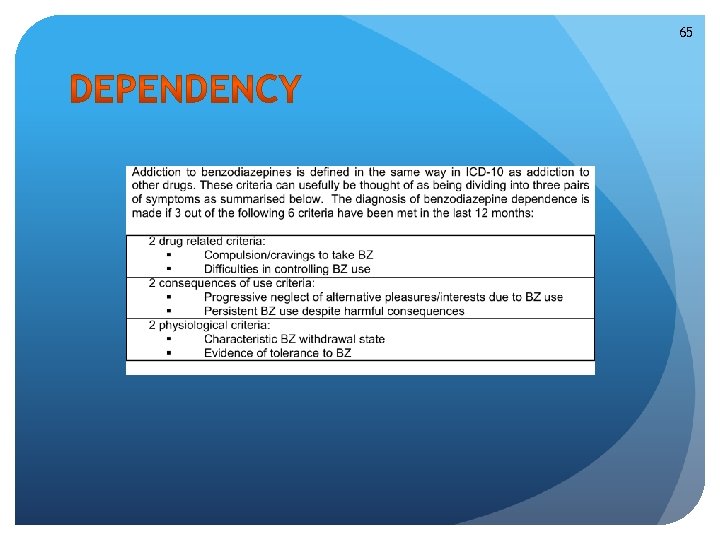

65

66 Tolerance to the different benzodiazepine effects such as anxiolytic, sedation and pleasure, develops at different speed, and this speed varies between individuals and can change in individuals over time. Tolerance can develop rapidly and increased doses are required to maintain the same effect, especially for certain types of effects. Tolerance develops to the pleasurable, sedative and motor coordination effects but only partially to the anticonvulsant effects. Tolerance may not develop to the anxiolytic, anti-panic and anti-phobic effects. There is a high degree of cross tolerance between other sedatives/ hypnotics and alcohol.

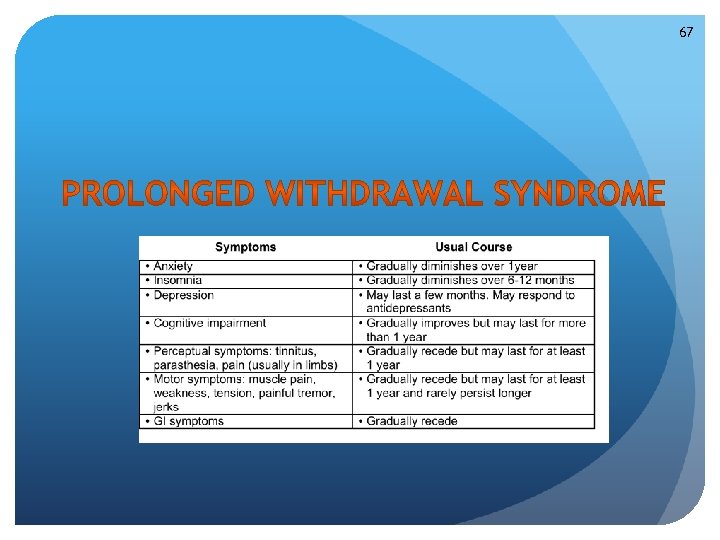

67

68 The liability to abuse of different benzodiazepines varies. The major factor increasing abuse liability is speed of onset of the drug which is unrelated to its elimination half-life. Diazepam and flunitrazepam have rapid onset of action despite very different half-lives. Oxazepam has a short half life but slow onset so has lower abuse potential. Clonazepam [long half life] increasingly abused via both prison and internet.

69 The reason is that rapid onset drugs are associated with “good” subjective effects, and therefore result in psychological reinforcement every time the drug is taken, which over time strengthens the psychological component of any addictive process. The second most important factor related to abuse is the dose of benzodiazepine, as a higher dose leads to better buzz.

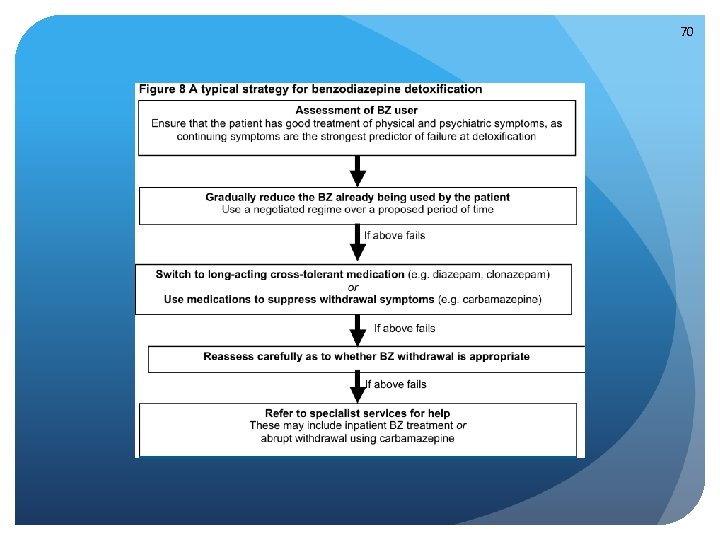

70

71 Withdrawal of a benzodiazepine prescription needs to be done with care and should be patient-specific. Two main areas should be considered: Dose reduction: This should be tailored to the individual. It may take weeks, months or even years but there should be no hurry, as the person needs to learn how to manage without drugs; hence it is better to handle dose reduction mainly in the community, as inpatient measures can be too rapid. Going too fast will cause the patient enormous difficulties and often leads to failure. It is best to allow the patient control. If there are problems, reduce speed but try not to go backwards. Psychological support: Provide as much or as little as the person requires, ranging from simple measures to long-term interventions. Ongoing support should always be offered, self-help should be encouraged, and, if appropriate, alternative coping skills training, such as anxiety management and CBT, should be arranged.

• Longer-term prescribing increases the likelihood of dependency. • RCGP data looked an available sample of a large national cohort also prescribed opiate substitution therapy • Median length of prescription = 29 days • 35. 3% longer than 8 weeks • 50% in subset with concurrent OST.

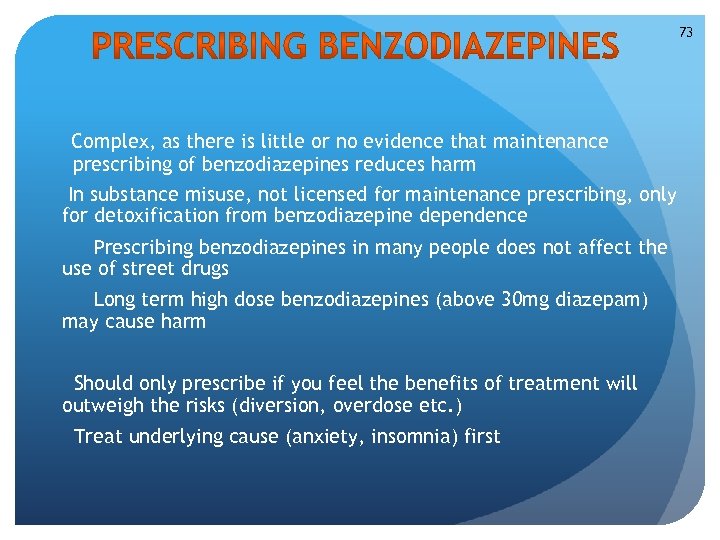

73 Complex, as there is little or no evidence that maintenance prescribing of benzodiazepines reduces harm In substance misuse, not licensed for maintenance prescribing, only for detoxification from benzodiazepine dependence Prescribing benzodiazepines in many people does not affect the use of street drugs Long term high dose benzodiazepines (above 30 mg diazepam) may cause harm Should only prescribe if you feel the benefits of treatment will outweigh the risks (diversion, overdose etc. ) Treat underlying cause (anxiety, insomnia) first

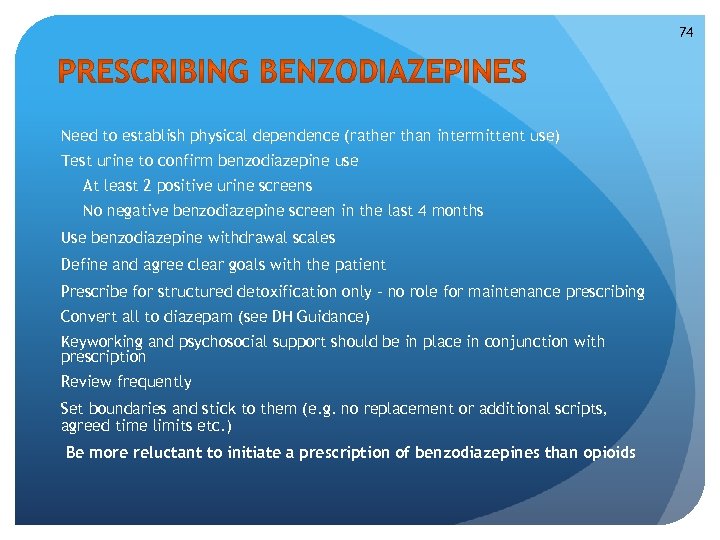

74 Need to establish physical dependence (rather than intermittent use) Test urine to confirm benzodiazepine use At least 2 positive urine screens No negative benzodiazepine screen in the last 4 months Use benzodiazepine withdrawal scales Define and agree clear goals with the patient Prescribe for structured detoxification only – no role for maintenance prescribing Convert all to diazepam (see DH Guidance) Keyworking and psychosocial support should be in place in conjunction with prescription Review frequently Set boundaries and stick to them (e. g. no replacement or additional scripts, agreed time limits etc. ) Be more reluctant to initiate a prescription of benzodiazepines than opioids

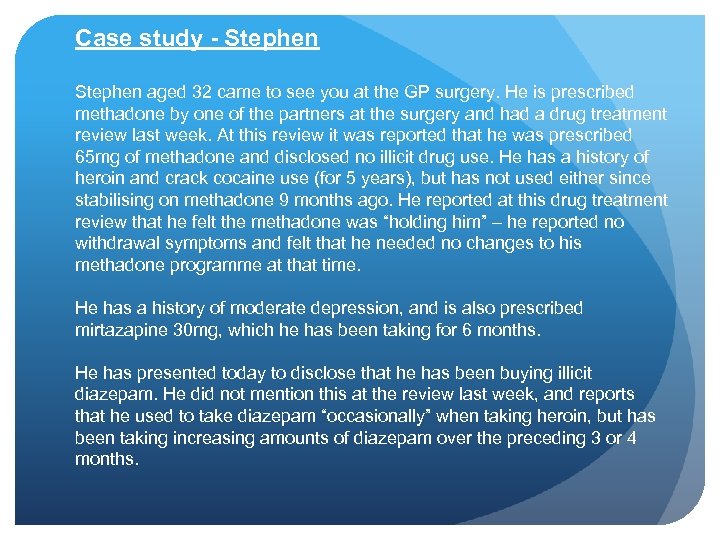

Case study - Stephen aged 32 came to see you at the GP surgery. He is prescribed methadone by one of the partners at the surgery and had a drug treatment review last week. At this review it was reported that he was prescribed 65 mg of methadone and disclosed no illicit drug use. He has a history of heroin and crack cocaine use (for 5 years), but has not used either since stabilising on methadone 9 months ago. He reported at this drug treatment review that he felt the methadone was “holding him” – he reported no withdrawal symptoms and felt that he needed no changes to his methadone programme at that time. He has a history of moderate depression, and is also prescribed mirtazapine 30 mg, which he has been taking for 6 months. He has presented today to disclose that he has been buying illicit diazepam. He did not mention this at the review last week, and reports that he used to take diazepam “occasionally” when taking heroin, but has been taking increasing amounts of diazepam over the preceding 3 or 4 months.

Stephen What would your initial assessment involve? What other information do you need? What are Stephen’s risks? What are the issues that you need to consider that influence a decision to prescribe benzodiazepines? What would be your treatment plan? If you decide to prescribe, what would you prescribe and what would be your ongoing plan with respect to this? Who else would you involve?

Case study - Irene is a 54 year old female patient who has recently joined your practice and presents to you saying, “I need my zopiclone”. She had seen the GP Registrar the previous evening and they refused to prescribe any zopiclone and told her it was “practice policy not to prescribe sleepers”. She is very distressed this morning, and presents tearful and anxious. On questioning she reveals that she is prescribed 28 x 3. 75 mg tablets per month (or so) and takes “ 1 or 2 each night” to help her sleep. She says she has been told in the past that the zopiclone is “bad for you”, but she feels that she “can’t cope” without them. She says they were initially prescribed by her previous GP when her husband left her 5 years earlier, and has been picking them up “without any problem” ever since. She moved into your practice area recently to be nearer to her daughter.

Irene Would you continue her prescription? What are the risks to Irene? What other issues are there? What would be your treatment plan? What are your prescribing options? Who else would you involve?

Case study - Mary 78 year old woman, comes to see you with her 43 year old daughter who lives 15 miles away. Family concerned as several falls and ambulance had to be called once when daughter away. Also says she has been a bit forgetful lately but she blames her age. Had a “nervous breakdown” in 1972 and was started on lorazepam 1. 5 mg tds and temazepam 10 mg at night

Case study - Mary She is well dressed and good eye contact, she repeatedly apologies for bothering you. On exam she has a mild tremor and is slightly unsteady when walking. MMSE scores 26

Case study - Mary What would your initial assessment involve? What other information do you need? What are her risks? What would be your treatment plan? Who else would you involve?

717635f41ec5f066e606e9c9ca1e70a6.ppt