feba7f3a59805e1ffd6905de434f8937.ppt

- Количество слайдов: 65

Outcomes-Informed Care and Performance Management: Implications for Behavioral Healthcare Integration G. S. (Jeb) Brown, Ph. D. Center for Clinical Informatics

Sources of data Information drawn from 5 performance management projects 1. Human Affairs International: 1996 -1999 2. Pacifi. Care Behavioral Health: 1999 – 2006 3. Resources for Living: 2001 -present 4. Accountable Behavioral Health Care Alliance: 2002 – present 5. Regence Behavioral Healthcare: 2007

Outcomes informed care • Use of patient self report outcomes questionnaires • Frequent administration in order to monitor patient response to treatment • Use of decision support tools to inform clinical judgment • Performance feedback to clinicians • Analysis of outcomes data to determine sources of variance: practice based evidence rather than evidence based practice • Use of practice based evidence to identify pathways to improved outcomes and to monitor success

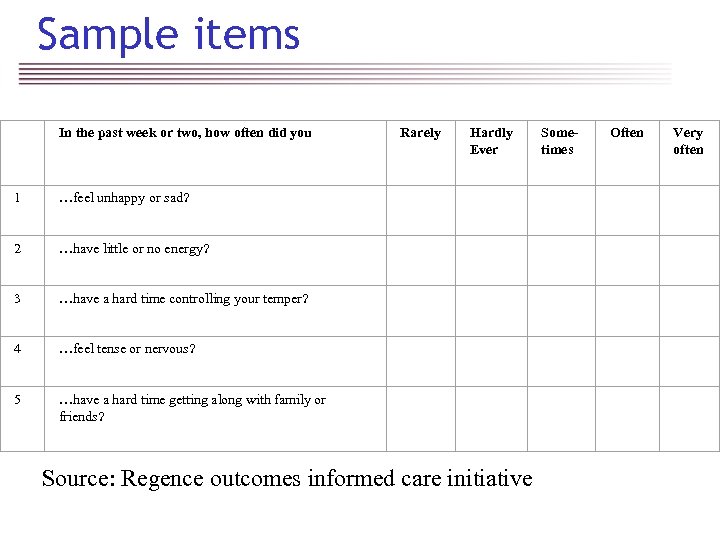

Outcomes questionnaires • All patient self report outcome questionnaires tend to load on a common factor: “global distress” • Due to the high degree of correlation between items, well constructed questionnaires of 10 -15 items can have coefficients of reliability and construct validity comparable to measures of 30 or more items. • Even ultra brief questionnaires of 4 -9 items may have adequate reliability and validity for must measurement needs.

Sample items In the past week or two, how often did you Rarely Hardly Ever Sometimes Often Very often 1 …feel unhappy or sad? 2 …have little or no energy? 3 …have a hard time controlling your temper? 4 …feel tense or nervous? 5 …have a hard time getting along with family or friends? Source: Regence outcomes informed care initiative

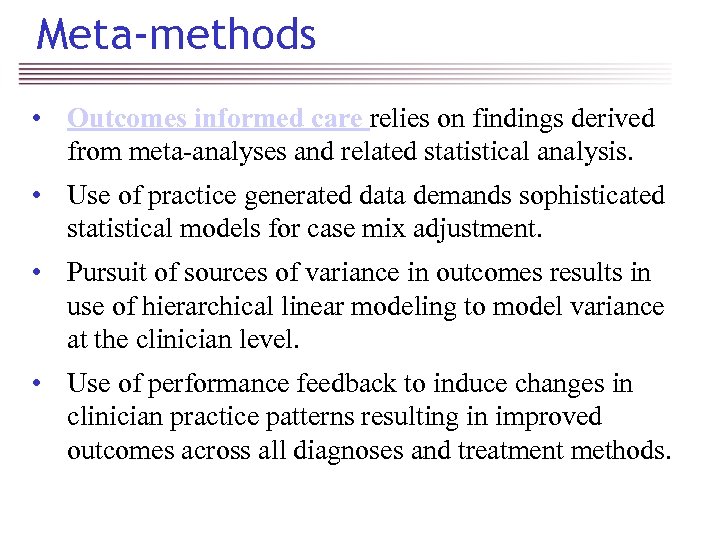

Meta-methods • Outcomes informed care relies on findings derived from meta-analyses and related statistical analysis. • Use of practice generated data demands sophisticated statistical models for case mix adjustment. • Pursuit of sources of variance in outcomes results in use of hierarchical linear modeling to model variance at the clinician level. • Use of performance feedback to induce changes in clinician practice patterns resulting in improved outcomes across all diagnoses and treatment methods.

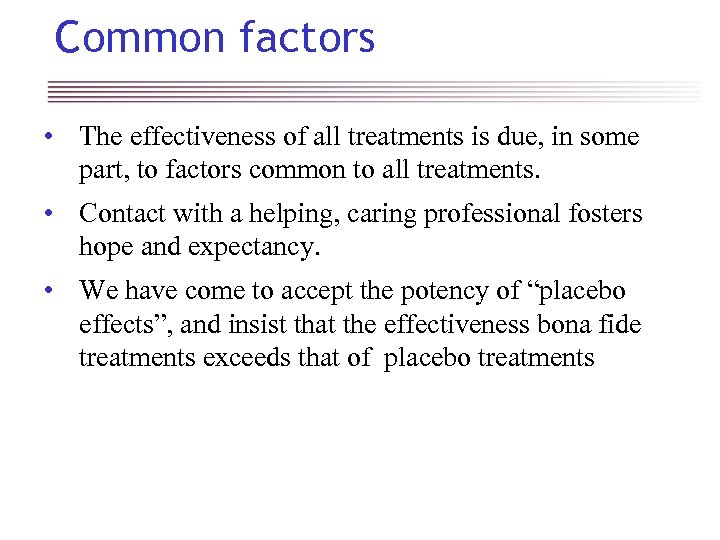

Common factors • The effectiveness of all treatments is due, in some part, to factors common to all treatments. • Contact with a helping, caring professional fosters hope and expectancy. • We have come to accept the potency of “placebo effects”, and insist that the effectiveness bona fide treatments exceeds that of placebo treatments

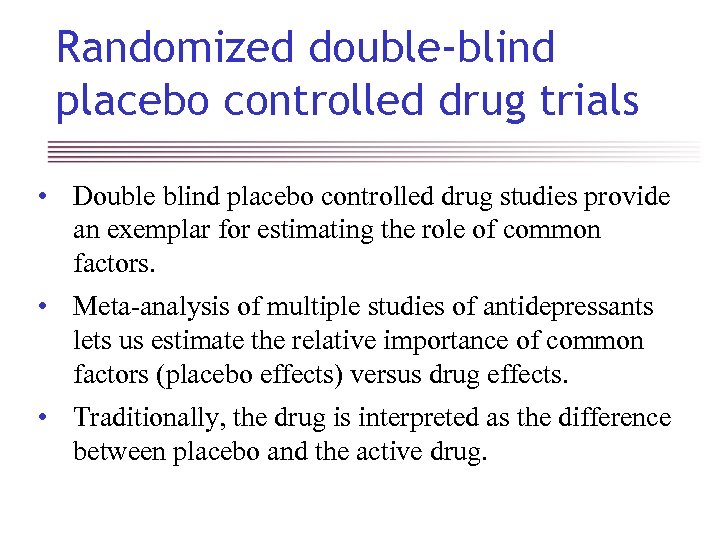

Randomized double-blind placebo controlled drug trials • Double blind placebo controlled drug studies provide an exemplar for estimating the role of common factors. • Meta-analysis of multiple studies of antidepressants lets us estimate the relative importance of common factors (placebo effects) versus drug effects. • Traditionally, the drug is interpreted as the difference between placebo and the active drug.

Meta-analyses and placebo • Meta-analysis involves the use of statistical techniques to combine results from multiple studies in order in an effort to generalize findings. • Meta-analysis of multiple studies of antidepressants let us estimate the relative importance of common factors (placebo effects) versus drug effects. 1 -3

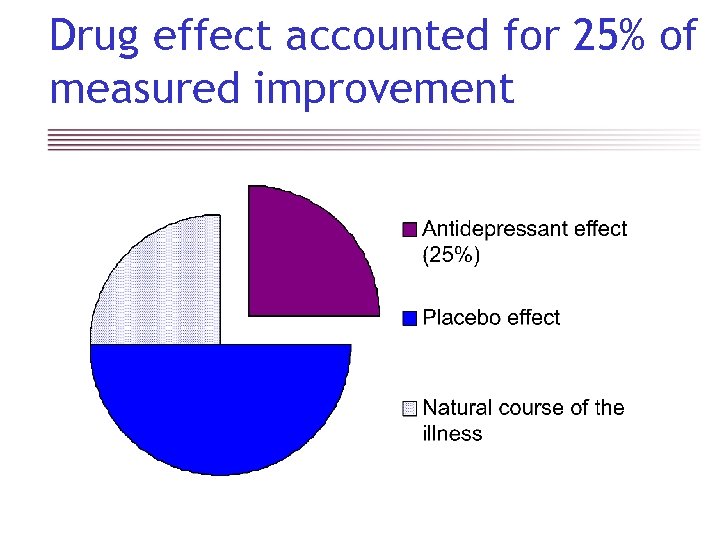

Drug effect accounted for 25% of measured improvement

Evidenced based psychotherapy • For several decades psychotherapy researchers have attempted to design randomly controlled trails (RCT) to investigate the effectiveness of specific methods of psychotherapy. • Study design analogous to pharmacy trials, except that designing credible “placebo treatments” is much more problematic. • Various treatment methods are being touted as “evidenced based” by citing the number of RCTs providing evidence that the treatment exceeded placebo (or some other treatment).

Psychotherapy “brands” • The advocacy for the use of specific therapies is analogous to the advertising of brands of antidepressant medication. • Calls for wide spread use of “evidence based treatments” in psychotherapy is analogous to the FDA’s insistence that a drug may not be marketed for the treatment of depression until at least two studies have shown superiority to placebo. • Advocates and practitioners of various “evidence based treatments” have a vested interest in discouraging the use of “unproven” treatments.

Brand differentiation • Advocates of psychotherapy brands insist on the uniqueness of their therapy and the need to adhere to specific treatment procedures • Research methodology requires the use of manuals and other techniques to standardize treatments • Treatment effectiveness presumed to be dependent on the correct application of the “active ingredients” in the psychotherapy method.

The Dodo Bird Effect Rosenzweig S. (1936) Some implicit common factors in diverse methods of psychotherapy: “At last the Dodo said, ‘Everybody has won and all must have prizes. ’” Am J Orthopsychiatry 6: 412 -5.

The Dodo Bird Lives! Wampold BE, Mondin GW, Moody M, et al. (1997). A meta-analysis of outcome studies comparing bona fide psychotherapies: Empirically, “All must have prizes. ” Psychol Bull 122: 203 -15. Luborsky, L. , Rosenthal, R. , Diguer, L. , et al. 2002 The dodo bird verdict is alive and well--mostly. J. Psychotherapy Integration Vol 12(1) 32 -57

Meta-analysis & common factors • Over two decades of meta-analytic studies have served to reinforce Rosenzweig’s 1936 observation that different methods of psychotherapy tend to produce comparable outcomes… the “Dodo Bird Effect” • Lack of evidence for specific treatment effects bolster the argument that almost all of the effects of psychotherapy are due to factors common to all psychotherapies. 5 -11

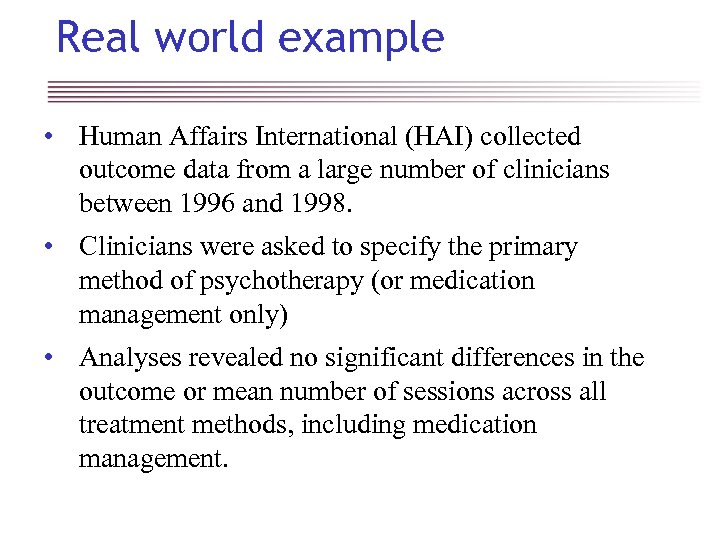

Real world example • Human Affairs International (HAI) collected outcome data from a large number of clinicians between 1996 and 1998. • Clinicians were asked to specify the primary method of psychotherapy (or medication management only) • Analyses revealed no significant differences in the outcome or mean number of sessions across all treatment methods, including medication management.

Treatment method & outcome HAI data

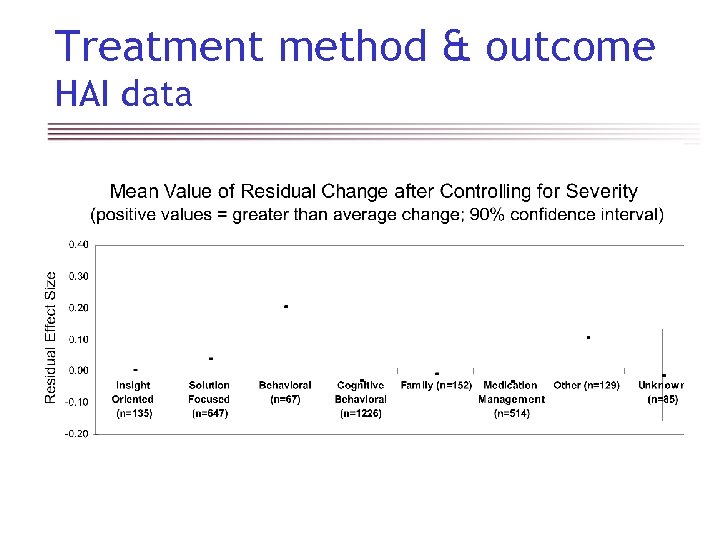

Test scores and medication PBH data Normal functioning Severe symptoms

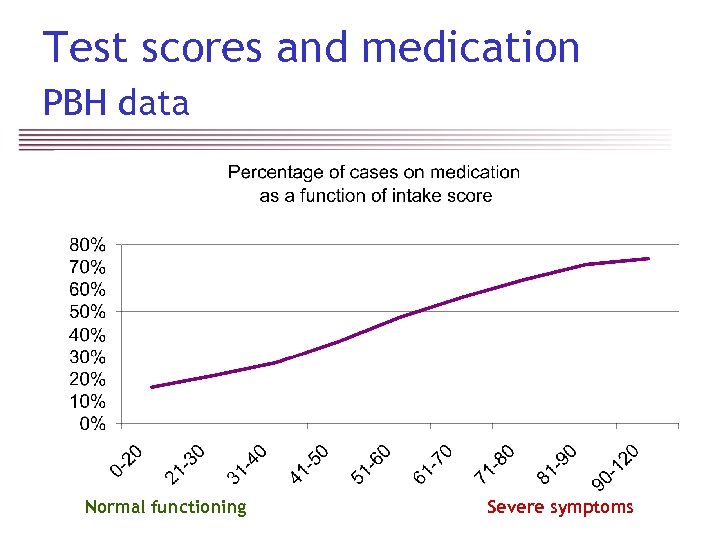

Which treatment is best? Goldilocks Effect: Clients tend to get the treatment that is just about right for them. Normal functioning Severe symptoms

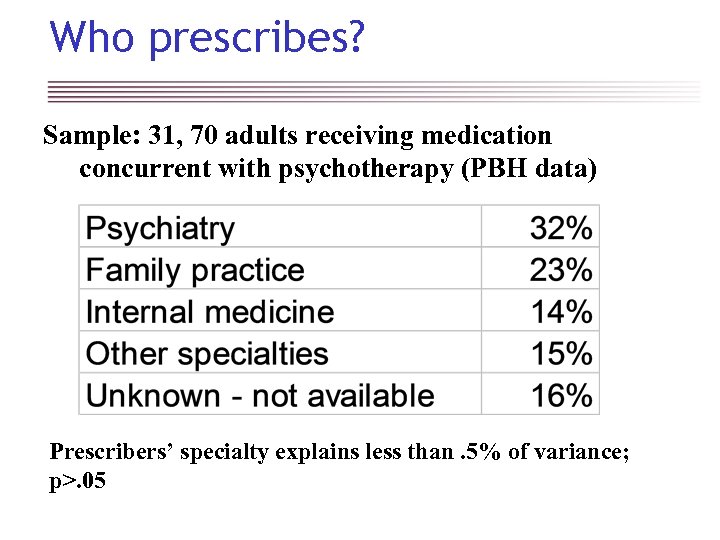

Who prescribes? Sample: 31, 70 adults receiving medication concurrent with psychotherapy (PBH data) Prescribers’ specialty explains less than. 5% of variance; p>. 05

Therapists effects • Wampold and others argue that researchers have ignored the individual therapist as a source of variance. 11, 16 -24 • The person of therapist is necessary to delivery the treatment, and personal characteristics of therapist modify the effect of the treatment. • Factors contributing to clinician effects may include elements clinical skill and knowledge as well as personality traits.

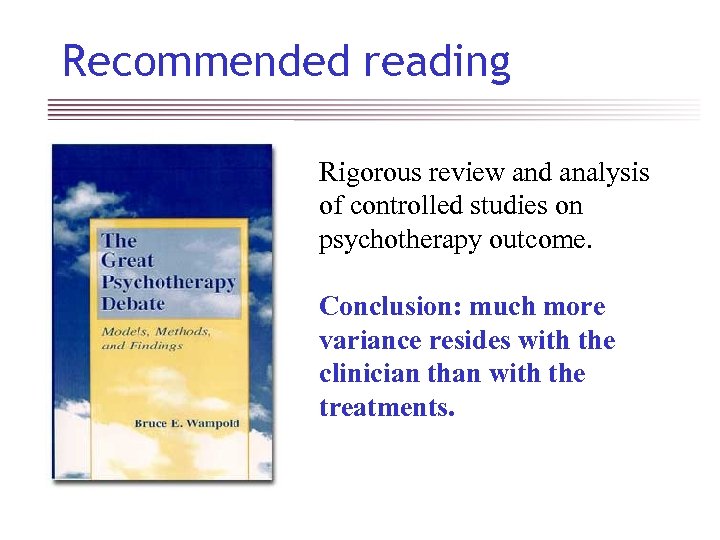

Recommended reading Rigorous review and analysis of controlled studies on psychotherapy outcome. Conclusion: much more variance resides with the clinician than with the treatments.

RCT and ANOVA – brief history • Some of the earliest applications of randomized control group design and analysis of variance were in agriculture and education. 12, 13 • RCT methodology later adopted by medicine and eventually psychotherapy research. 11, 14 • Simple ANOVA is appropriate only if the individual farmer, teacher or clinician has little or no impact on the effectiveness of the farming, teaching or treatment method!

HLM & therapist effects • Hierarchical Linear Modeling (HLM) is an advance in statistical methodology that permits us to model variance at the clinicians level and as well as the treatment level. • An rapidly growing body of published research points to the conclusion that therapist effects almost certainly exceed specific treatment effects by a large margin.

Variance due to the clinician • Published research making use of HLM points to the conclusion that the clinician accounts for much more of the variance in psychotherapy outcomes that treatment method per se. 11, 17 -21 • Analyses of Pacifi. Care Behavioral Health’s massive database on patient outcomes confirms significant variance in psychotherapy outcomes at the clinician level. 24, 25

Pacifi. Care Behavioral Health ALERT System • Initiated an outcomes management program in 1998 using 30 item patient self report questionnaires administered at regular intervals in treatment. • ALERT System used to capture data and monitor patient outcomes in real time. • Over 10, 000 clinicians are contributed outcome data on a regular basis. • Probably largest database on mental health outcomes in the world.

PBH research collaboration • PBH actively sought the involvement of leading psychotherapy outcomes researchers from leading academic institutions. • External researchers actively involved in design of the measurement system and ongoing analysis of the data. • PBH encouraged publication of findings in academic journals.

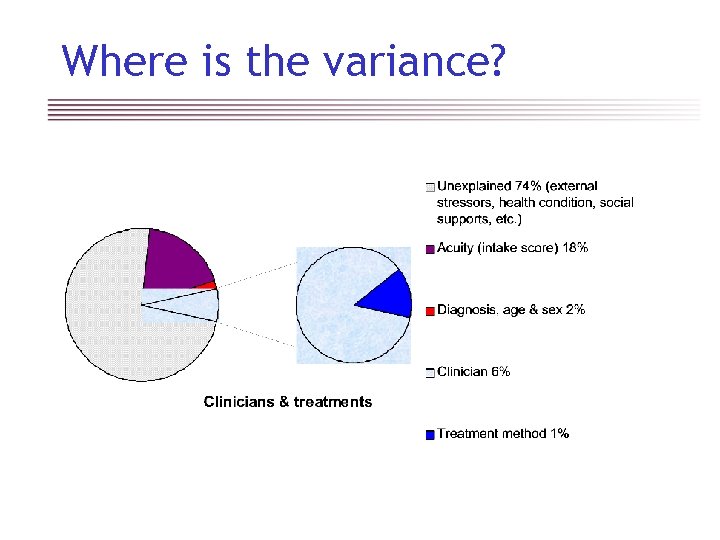

Where is the variance?

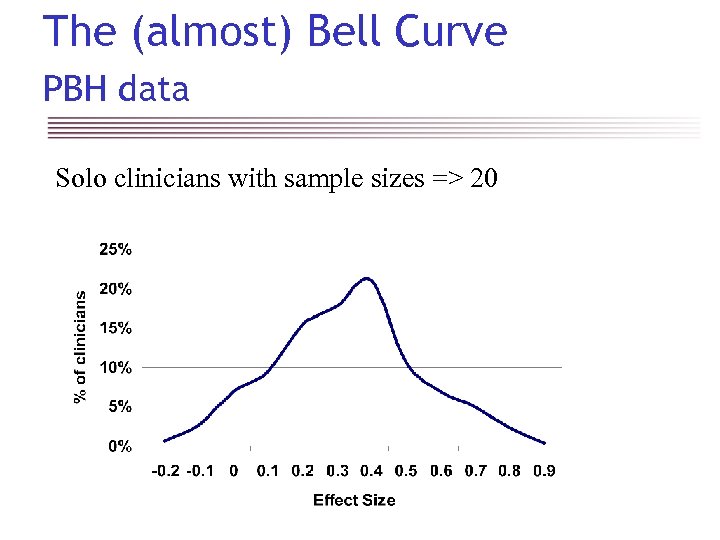

The (almost) Bell Curve PBH data Solo clinicians with sample sizes => 20

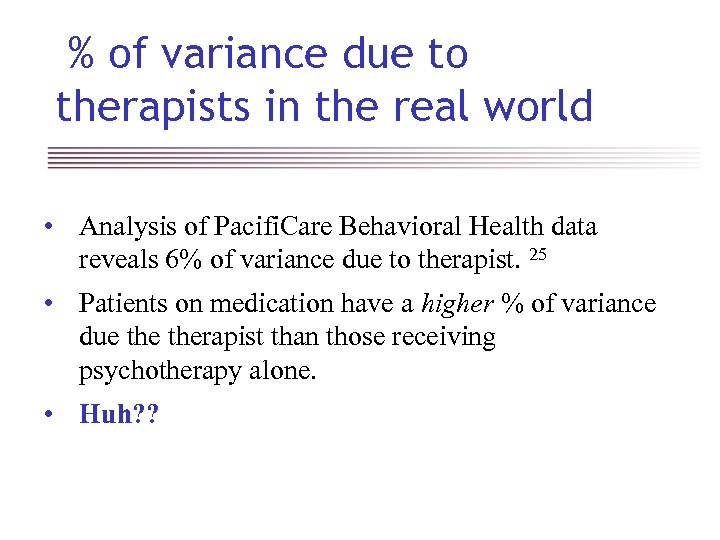

% of variance due to therapists in the real world • Analysis of Pacifi. Care Behavioral Health data reveals 6% of variance due to therapist. 25 • Patients on medication have a higher % of variance due therapist than those receiving psychotherapy alone. • Huh? ?

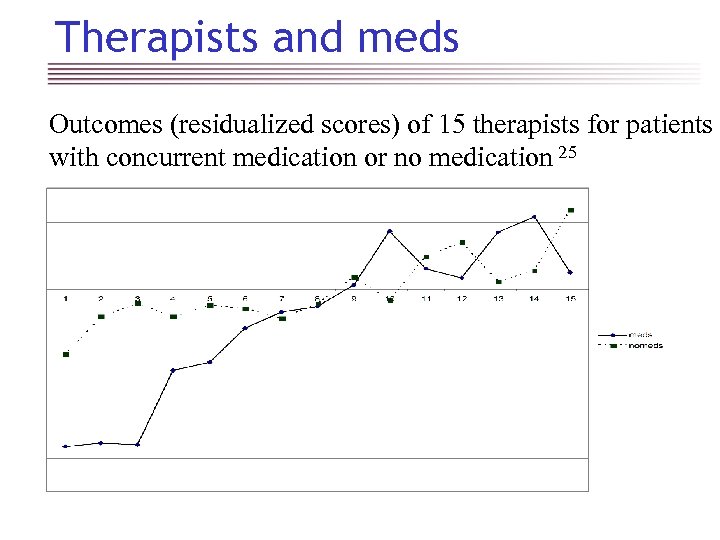

Therapists and meds Outcomes (residualized scores) of 15 therapists for patients with concurrent medication or no medication 25

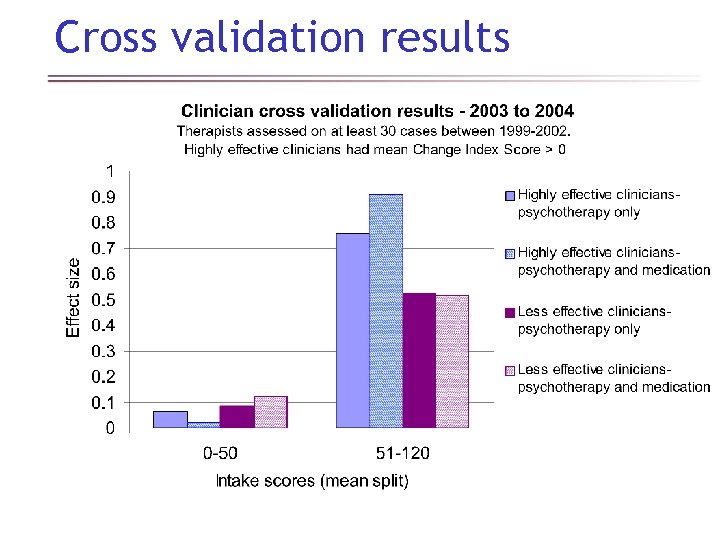

Cross validation analysis • Psychotherapists in PBH network ranked based on all cases from 1999 -2002 if sample size =>30; N=116. • If a therapist’s mean residualized final score < 0 then clinician rated “Highly effective”; else clinician rated “Less effective”. • Outcomes evaluated in the 2003 -2004 cross validation period for a new sample of cases.

Cross validation results

Psychiatrist effects • Wampold and colleagues also used HLM to reanalyze the results antidepressant and placebo legs of the NIMH-Treatment of Depression Collaborative Research Project study. 28 • Included the 9 individual psychiatrists as a variable. • Outcome measured by change on patient self report measure (Beck Depression Inventory). • 9. 1% of the variance due to the psychiatrist; only 3. 4% due to the medication. • Top 3 psychiatrists had a better outcome with placebo than bottom 3 had with the antidepressant.

Placebo & therapist effects • Hypothesis: Placebo/common factor effects are mediated by the clinician/patient relationship. • Common factors tend to account for much more of the variance than specific treatment effects. • If the effects of common factors are mediated by the clinician/patient relationship, then we would naturally find much of the variance in outcomes would be due to the clinician. • The human factor matters!

What’s a clinician to do? • If a wide variety of treatments appear to be equally efficacious, what can a clinician do to achieve the best outcomes possible for their patients? • A growing body of research supports the use of repeated administrations of patient self report outcome questionnaires to monitor response to treatment. 29 -36 • Routine measurement and early identification of patients with a poor response to treatment has been shown to reduce treatment failures.

Therapeutic alliance • A large body of evidence suggests that the relationship and working alliance between the clinician and patient is an important factor in the outcome. 39 -45 • Routine use of a session rating/therapeutic alliance scale may permit clinicians to identify and repair problems in the working alliance.

Can we improve outcomes? • Increasing the percentage of patients treated by highly effective clinicians (as identified through practice based evidence) is the most direct pathway open to a health plan seeking to improving outcomes across a large system of care. • See PBH’s Honors for Outcomes initiative: http: //www. pbhi. com/Providers_public/FAQs/H 4 OFAQ. asp • Smaller organizations may be able to improve outcomes by fostering outcomes informed care methods within the organization.

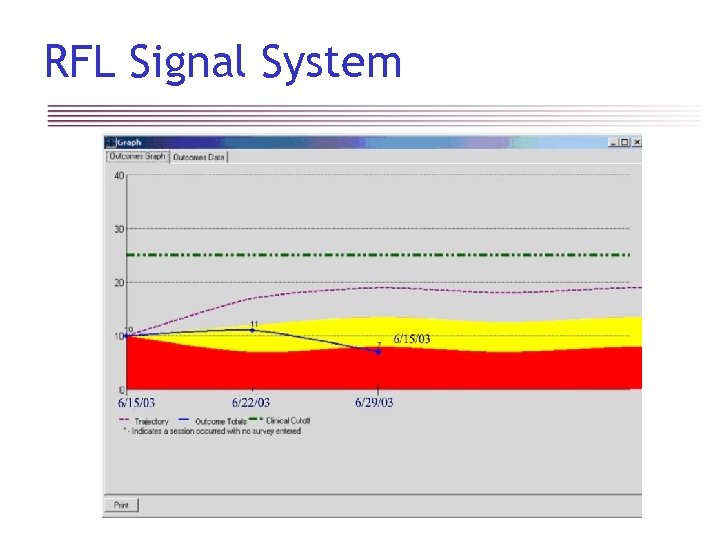

Resources for Living (RFL) • Provides telephonic EAP services, data collected over the phone at time of service; clinicians receive real time feed back on trajectory of improvement and working alliance (SIGNAL system) • Outcome measures: Outcome Rating Scale (4 items); also utilizes the Session Rating Scale (4 items) to the working alliance

RFL Signal System

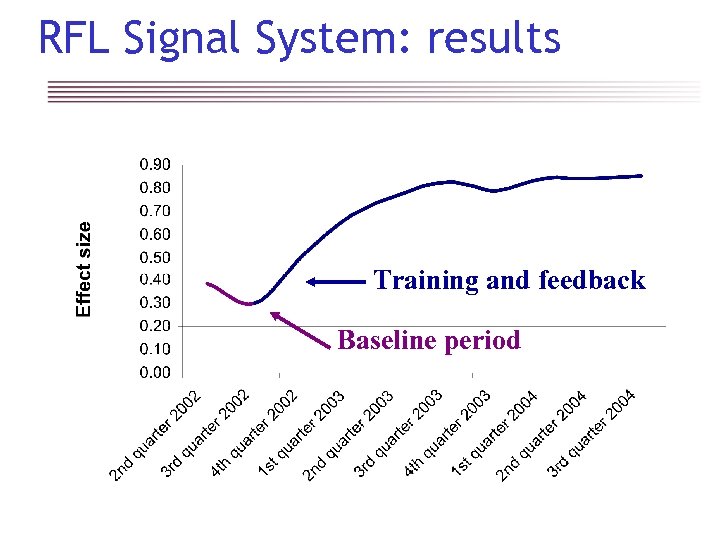

RFL Signal System: results Training and feedback Baseline period

Accountable Behavioral Healthcare Alliance (ABHA) • Managed behavioral healthcare organization servicing Oregon Health Plan members in 5 rural county areas • Outcome measure: Oregon Change Index (4 items; based on the Outcome Rating Scale)

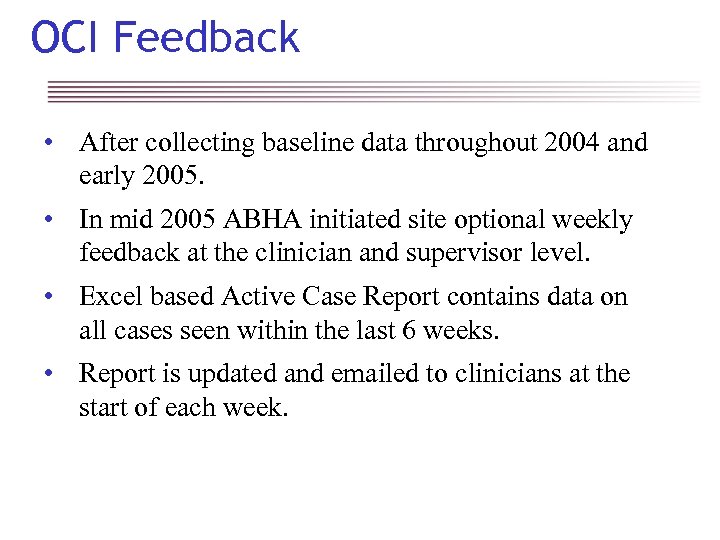

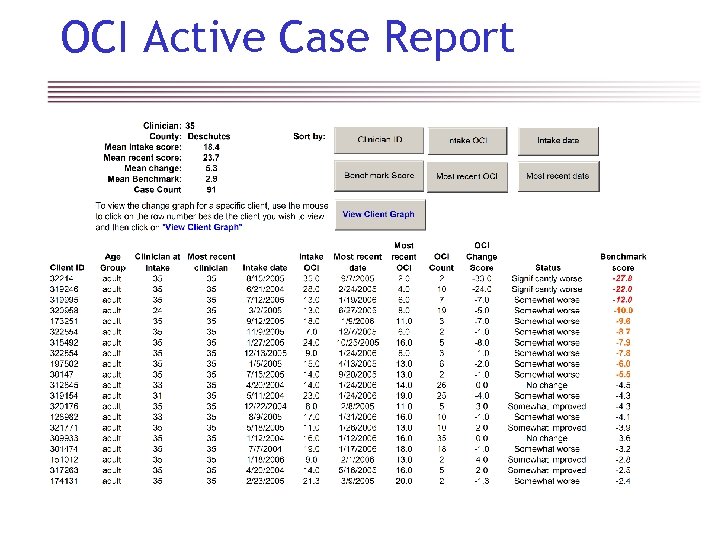

OCI Feedback • After collecting baseline data throughout 2004 and early 2005. • In mid 2005 ABHA initiated site optional weekly feedback at the clinician and supervisor level. • Excel based Active Case Report contains data on all cases seen within the last 6 weeks. • Report is updated and emailed to clinicians at the start of each week.

OCI Active Case Report

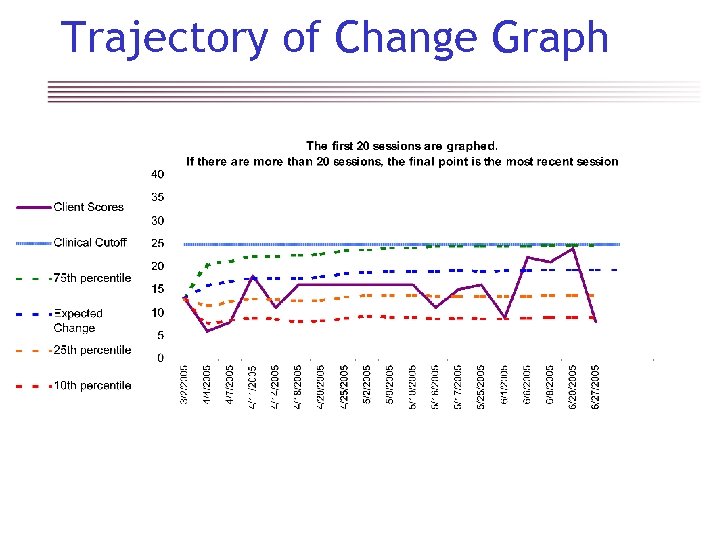

Trajectory of Change Graph

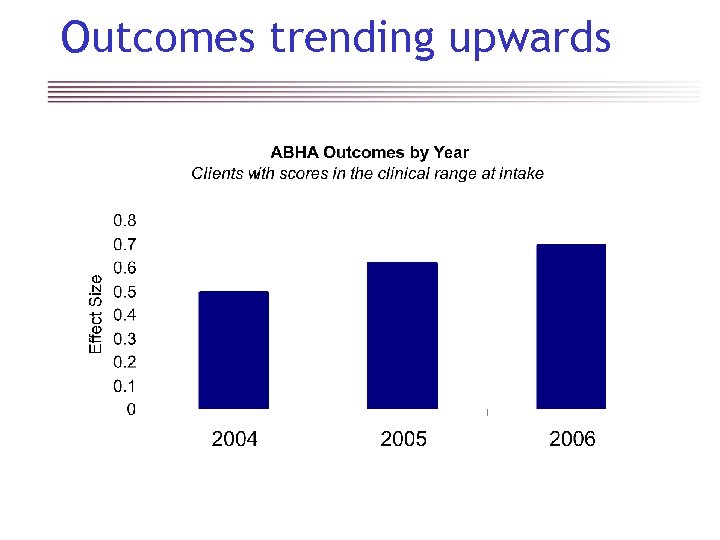

Outcomes trending upwards

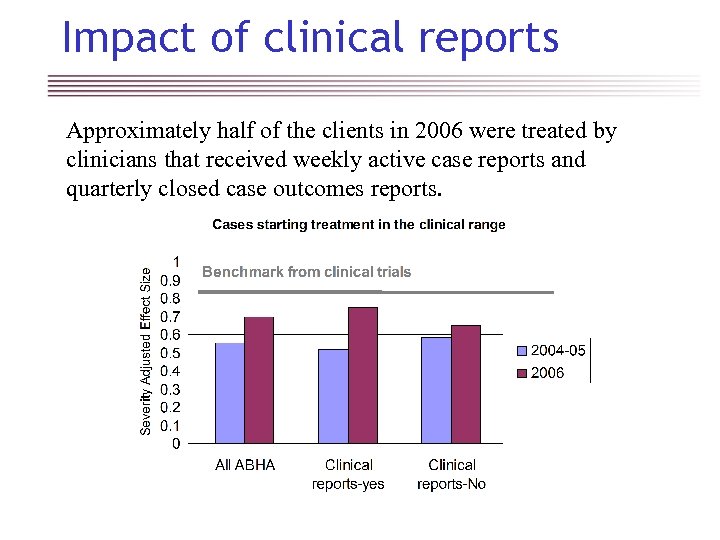

Impact of clinical reports Approximately half of the clients in 2006 were treated by clinicians that received weekly active case reports and quarterly closed case outcomes reports.

Primary barrier… the clinician • Most clinicians believe that their outcomes are above average and their services are of high value, without the need to actually measure this • Many clinicians feel discomfort at the thought that their performance might be evaluated by their patients via self report outcome questionnaires • Clinicians often believe that a simple outcome questionnaire cannot provide useful information about their patients beyond what they obtain by forming their own clinical judgments.

Secondary barriers • Faith in treatments (therapy methods, drugs) to deliver consistent and predictable outcomes • Belief that the cost of the services is so low (relative to overall medical costs) that meaningful performance management isn’t cost effective • Belief that meaningful performance management isn’t necessary to retain existing business or acquire new customers. • Lack of organizational commitment to place the patient first and/or desire to avoid conflict with clinicians

Involving motivated providers • Top down strategies insisting on outcomes measurement for all clinicians must over come enormous active and passive resistance on the part of clinicians. • Effective clinicians have to most to gain from the implementation of outcomes informed care. • Those clinicians that voluntarily collect outcome data tend to have better results than the average clinician. • Make it easy for clinicians to volunteer and then make it worth their while!

New initiative…. • The Regence, an affiliation of Blue Cross and/or Blue Shield plans in 4 western states, is collaborating with motivated providers to implement an outcomes management system. • Western Psychological and Counseling Services, Inc. (www. westernpsych. com) a behavioral health practice with over 100 clinicians, is taking the lead as the first pilot site. • This practice has achieved consistently above average outcomes according the PBH ALERT system.

Feedback and flexibility • Regence initiative uses a TWiki to facilitate feedback from clinicians. • Item repository permits use of questionnaires that tailored to the measurement task. • Items included based on analysis of psychometric properties and feedback from users. • Outcomes management system permits rapid prototyping, testing and modification of clinical reports.

Return on Investment • The Regence outcomes management system is designed to keep the cost of routine use of questionnaires, data capture and reporting as low as possible. • Per patient cost for outcomes measurement and reporting is less than 1% of the cost of an episode of care. • Improved outcomes translates to improved productivity in workplace and reduction in other medical costs.

References 1. 2. 3. 4. 5. Kirsch, I & Sapirstein, G. 1998. Listening to Prozac but hearing placebo: A meta analysis of antidepressant medication. Prevention & Treatment. 1, Article 0002 a, No Pagination Specified Kirsch, I. 2000. Are drug and placebo effects in depression additive? Biological Psychiatry 47, 733 -73. Kirsch, I, Moore, TJ, Scoboria, A, Nicholls, SS. 2002. The emperor's new drugs: An analysis of antidepressant medication data submitted to the U. S. Food and Drug Administration. Prevention & Treatment. 5(1), No Pagination Specified Rosenzweig S. 1936. Some implicit common factors in diverse methods of psychotherapy: “At last the Dodo said, ‘Everybody has won and all must have prizes. ’” Am J Orthopsychiatry 6: 412 -5. Shapiro DA & Shapiro D. 1982. Meta-analysis of comparative therapy outcome studies: A replication and refinement. Psychol Bull 92: 581 -604.

References (continued) 6. Robinson LA, Berman JS, Neimeyer RA. 1990. Psychotherapy for treatment of depression: A comprehensive review of controlled outcome research. Psychol Bull 108: 30 -49. 7. Wampold BE, Mondin GW, Moody M, et al. 1997. A meta-analysis of outcome studies comparing bona fide psychotherapies: Empirically, “All must have prizes. ” Psychol Bull 122: 203 -15. 8. Ahn H, Wampold BE. 2001. Where oh where are the specific ingredients? A meta-analysis of component studies in counseling and psychotherapy. J Counsel Psychol 48: 251 -7. 9. Chambless DL, Ollendick TH. 2001. Empirically supported psychological interventions: Controversies and evidence. Annual Rev Psychol 52: 685 -716. 10. Luborsky, L. , Rosenthal, R. , Diguer, L. , et al. 2002. The dodo bird verdict is alive and well--mostly. J. Psychotherapy Integration Vol 12(1) 32 -57

References (continued) 11. Wampold BE. 2001. The great psychotherapy debate: Models, Methods, and Findings. Mahwah NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates. Wampold BE, Mondin GW, Moody M, et al. 1997. A meta-analysis of outcome studies comparing bona fide psychotherapies: Empirically, “All must have prizes. ” Psychol Bull 122: 203 -15. 12. Mc. Call, WA. 1923 How to experiment in education. New York: Mcm. Illan. 13. Fisher, RA. 1935 The design of experiments. Edinburgh: Oliver and Boyd. 14. Gehan, E. & Lemark, NA. 1994. Statistics in medical research: Developments in clinical trials. New York: Plenum Press. 15. Martindale C. 1978. The therapist-as-fixed-effect fallacy in psychotherapy research. J Consult Clin Psychol 46: 1526 -30.

References (continued) 16. Luborsky L, Crits-Christoph P, Mc. Lellan T, et al. 1986. Do therapists vary much in their success? Findings from four outcome studies. Am J Orthopsychiatry 56: 501 -12. 17. Crits-Christoph P, Baranackie K, Kurcias JS, et al. 1991. Metaanalysis of therapist effects in psychotherapy outcome studies. Psychother Res 1: 81 -91. 18. Crits-Christoph P, Mintz J. 1991. Implications of therapist effects for the design and analysis of comparative studies of psychotherapies. J Consul Clin Psychol 59: 20 -6. 19. Wampold BE. 1997. Methodological problems in identifying efficacious psychotherapies. Psychother Res 7: 21 -43, 20. Elkin I. 1999. A major dilemma in psychotherapy outcome research: Disentangling therapists from therapies. Clin Psychol Sci Prac 6: 10 - 32.

References (continued) 21. Wampold BE, Serlin RC. 2000. The consequences of ignoring a nested factor on measures of effect size in analysis of variance designs. Psychol Methods 4: 425 -33. 22. Huppert JD, Bufka LF, Barlow DH, et al. 2001. Therapists, therapist variables, and cognitive-behavioral therapy outcomes in a multicenter trial for panic disorder. J Consul Clin Psychol 69: 747 -55. 23. Okiishi J, Lambert MJ, Nielsen SL, et al. 2003. Waiting for supershrink: An empirical analysis of therapist effects. Clin Psychol Psychother 10: 361 -73. 24. Brown GS, Jones ER, Lambert MJ, et al. 2005. Identifying highly effective psychotherapists in a managed care environment. Am J Managed Care 11(8): 513 -20. 25. Wampold BE, Brown GS. 2005. Estimating variability in outcomes due to therapist: A naturalistic study of outcomes in managed care. J Consul Clin Psychol. 73(5): 914 -923.

References (continued) 26. Elkin, I, Shae, T, Watkins, JT. , et al. 1989. National Institute of Mental Health Treatment of Depression Collaborative Research Program: General effectiveness of treatments. Archive of General Psychiatry. 46: 971 -982. 27. Kim DM, Wampold BE, Bolt DM. 2006. Therapist effects and treatment effects in psychotherapy: Analysis of the National Institute of Mental Health Treatment of Depression Collaborative Research Program. Psychother Res. 16(2): 161 -172. 28. Mc. Kay, KM, Imel, ZE & Wampold, BE. In press. Psychiatrist effects in the pharmacological treatment of depression. J. Affective Disorders. 29. Hannan C, Lambert MJ, Harmon C et al. 2005. A lab test and algorithms for identifying clients at risk for treatment failure. J Clin Psychol 61(2): 155 -63. 30. Lambert MJ, Harmon C, Slade K et al. 2005. Providing feedback to psychotherapists on their patients progress: Clinical results and practice suggestions J Clin Psychol 61(2): 165 -74.

References (continued) 31. Harmon C, Hawkins, Lambert MJ et al. 2005. Improving outcomes for poorly responding clients: The use of clinical support tools and feedback to clients. J Clin Psychol 61(2): 175 -85. 32. Brown GS, Jones DR. 2005. Implementation of a feedback system in a managed care environment: What are patients teaching us? J Clin Psychol 61(2): 187 -98. 33. Claiborn CD, Goodyear EK. 2005. Feedback in psychotherapy. J Clin Psychol 61(2): 209 -21. 34. Lueger RJ. 1998. Using feedback on patient progress to predict the outcome of psychotherapy. J Clin Psychol 54: 383 -93. 35. Lambert MJ, Whipple JL, Smart DW, et al. 2001. The effects of providing therapists with feedback on patient progress during psychotherapy: Are outcomes enhanced? Psychother Res 11(1): 49 -68.

References (continued) 36. Lambert MJ, Whipple JL, Vermeersch DA, et al. 2002. Enhancing psychotherapy outcomes via providing feedback on client progress: A replication. Clin Psychol Psychother 9: 91 -103. 37. Whipple JL, Lambert MJ, Vermeersch DA, et al. 2003. Improving the effects of psychotherapy: The use of early identification of treatment failure and problem-solving strategies in routine practice. J Counsel Psychol 50(1): 59 -68. 38. Lambert MJ, Whipple JL, Hawkins EJ, et al. 2003. Is it time for clinicians to routinely track patient outcome? A meta-analysis. Clin Psychol Sci Prac 10: 288 -301. 39. Bachelor, A. , & Horvath, A. (1999). The therapeutic relationship. In M. A. Hubble, B. L. Duncan, and S. D. Miller (eds. ). The Heart and Soul of Change: What Works in Therapy. Washington, D. C. : APA Press, 133 -178. 40. Blatt, S. J. , Zuroff, D. C. , Quinlan, D. M. , & Pilkonis, P. (1996). Interpersonal factors in brief treatment of depression: Further analyses of the NIMH Treatment of Depression Collaborative Research Program. J Consul Clin Psychol. 64, 162 -171.

References (continued) 41. Bordin, E. S. (1979). The generalizability of the psychoanalytic concept of the working alliance. Psychotherapy: Theory, Research, and Practice, 16, 252 -260. 42. Burns, D. , & Nolen-Hoeksema, S. (1992). Therapeutic empathy and recovery from depression in cognitive-behavioral therapy: A structural equation model. J Consul Clin Psychol. 60, 441 -449. 43. Connors, GJ, Di. Clemente, CC. , Carroll, KM, et al. 1997 The therapeutic alliance and its relationship to alcoholism treatment participation and outcome. J Consul Clin Psychol, 65(4), 588 -598. 44. Horvath, A. O. , & Symonds, B. D. (1991). Relation between working alliance and outcome in psychotherapy: A meta-analysis. J Consul Clin Psychol. 38, 139 -149. 45. Krupnick, J. , Sotsky, SM, Simmens, S et al. 1996. The role of therapeutic alliance in psychotherapy and pharmacotherapy outcome: Findings in the National Institute of Mental Health Treatment of Depression Collaborative Research Project. J Consul Clin Psychol. , 64, 532 -539.

About the presenter G. S. (Jeb) Brown is a licensed psychologist with a Ph. D. from Duke University. He served as the Executive Director of the Center for Family Development from 1982 to 19987. He then joined United Behavioral Systems (an United Health Care subsidiary) as the Executive Director for of Utah, a position he held for almost six years. In 1993 he accepted a position as the Corporate Clinical Director for Human Affairs International (HAI), at that time one of the largest managed behavioral healthcare companies in the country. In 1998 he left HAI to found the Center for Clinical Informatics, a consulting firm specializing in helping large organizations implement outcomes management systems. Client organizations include Pacifi. Care Behavioral Health/ United Behavioral Health, Department of Mental Health for the District of Columbia, Accountable Behavioral Health Care Alliance, Resources for Living and assorted treatment programs and centers throughout the world. Dr. Brown continues to work as a part time psychotherapist at behavioral health clinic in Salt Lake City, Utah. He does measure his outcomes.

http: //www. clinical-informatics. com jebbrown@clinical-informatics. com 1821 Meadowmoor Rd. Salt Lake City, UT 84117 Voice 801 -541 -9720

feba7f3a59805e1ffd6905de434f8937.ppt